Introduction

The era of the knowledge and information society has radically changed theories and thoughts that indicate only one way to verify student learning. In this sense, in the face of the constantly dizzying changes to which today’s world is subjected, it continually forces teachers to stay updated regarding the forms of evaluation, an aspect that entails a comprehensive review of learning or simply learning new things to take into consideration new trends, which indicates that learning is always and throughout life, continuous evaluation processes for this reason must adjust to this reality.

From this perspective, Fernández (2017), in his article entitled Evaluation and learning, proposes the existence of a dialectic between learning and evaluation, an indissoluble relationship where one part is not possible without the other, therefore, it is of utmost importance to consider the of evaluation in this very important process.

Precisely, it was in the research carried out on the formation of scientific concepts, the learning of language carried out in his maturity, that Vygotsky developed a pedagogical approach to the evaluation of learning.

Complementing the above, according to Arias et al., (2019), there are various realities that evolve at such a scale, causing knowledge to achieve multiple connotations, which results in suggestive perspectives on them. In this sense, evaluation as such, for decades, has been understood by scholars and experts as a postural critical process, since conceptions have emerged from various paradigms that throughout their historical development have promulgated according to their positioning the being, of this activity.

Also, Ortega Martínez et al., (2021), developed a research entitled Considerations on formative assessment practices in primary education. A case study. In this work, the authors point out that:

A challenge that has been present in Basic Education, over the years until today, has been how the evaluation of learning is applied, with emphasis on the training dimension, due to the little understanding and limitations around training teacher on these topics. It emphasizes the importance of promoting a culture of evaluation that ensures the development of a systematic, rigorous, reflective process oriented towards academic decision-making...Concluding that it is important to systematize educational practices where feedback processes are privileged, through which self-regulation of learning is promoted, as part of the culture of evaluation. (Ortega Martínez et al., 2021, p.114).

Taking into account the above, the research generated by this article has sought to analyze evaluation from evaluative practices, with a mixed approach, taking into account the importance that this process takes for the agents of the educational community involved in the training of subjects. It is contextualized through three evaluation references, obtained through the aspects of the theoretical reference examined, firstly, its conception as a systematic process that is part of teaching and learning, secondly, as an aspect to investigate, in addition to understand the educational reality, specifically what refers to both knowledge management and knowledge. Thirdly, as an aspect to guide the processes for improving quality in the educational institution; focusing on these three perspectives within formative evaluation.

It is necessary to highlight the findings evidenced, which make possible the formulation of new lines of research in the area, which contribute to generating intellectual production on topics related to this field of study.

Theoretical Reference

In order to demonstrate the state of the art of the variables analyzed, the theoretical references that provide knowledge to the field explored are reviewed, in order to substantiate what is described in this article:

Learning Evaluation

Today’s education is a global training space, which is characterized by systems that present common points, such as marketing, the greater use of tests, responsibility and accountability, international comparisons and the insistence on the improvement of standards as proposed by Plum, 2014; Smith, 2016, cited by Ydesen and Andreasen (2019).

A clear example is the case of third and sixth grade students in Panama, who reflected in the ERCE-2019 tests that they have difficulties developing their ideas, maintaining internal coherence when writing a text, in addition to poor vocabulary.

These approaches were presented in the results of the writing test of the Regional Comparative and Explanatory Study (ERCE-2019), published by the United Nations Cultural, Scientific and Educational Organization (UNESCO).

According to the results inherent to the discursive mastery indicator, 8 out of every 10 students in third grade failed to develop a text corresponding to the genre of the letter that they were asked to write during the test, therefore, they were placed in the lowest performance level.

For Vera and González-Ledesma (2018), in their article Quality and evaluation: Marriage of heaven and hell, they point out that in the last 40 years, educational evaluation has gone from being a fundamentally diagnostic instrument, which is applied in some countries, to become a practice of global reach, this aspect highlights the importance of the change of vision in the models and practices of evaluation, the authors continue to indicate the need to be considered as a necessary mechanism for the governance of educational systems. It is important to highlight the significant changes experienced in evaluation, from its origins as a diagnostic tool, to expanding its functions as a means to encourage or dissuade behaviors, an aspect that allows us to see the diagnostic and formative function of evaluation.

For Coll and Martín (2012); Alonso et al., (1995), cited in Giménez Beut, et al. (2021), the ways of evaluating in educational centers may be linked to the concept of teaching that teachers have, they consider they are subject to those experiences achieved, although, for many decades now, proposals for change and transformation have been proposed in both the teaching actions inherent to the forms of evaluation.

In educational work, the evaluation process translates into the collection of information, mainly through evaluation instruments, for (Castillo, 2003; Pimienta, 2008), cited in Giménez Beut et al., (2021), these are defined as everything that allows obtaining information regarding the acquisition and degree of achievement of student learning. They must meet specific parameters, such as being of optimal quality, since this can ensure obtaining reliable evidence about the students’ achievements. On the other hand, with the evaluation instruments a clearer idea is achieved when making decisions and proposing improvements within the teaching-learning process.

To list some evaluative characteristics, we must highlight the contributions of Zabalza 2001; Yániz, 2002, cited in Barragán Sánchez (2005), who point out that:

The evaluation must be immersed in the usual development of the teaching-learning process.

The evaluation must cover the entire training process, initial, process and final.

The evaluation must be formative.

The evaluation must include varied and progressive cognitive demands.

During the 20th century, the exam appeared as an activity and technique, with this tool the aim was to assess the knowledge achieved by students after the development of the contents addressed in the classroom. Rosales (2015) highlights that, in the same way, evaluation was called the ability to relate and apply the acquisitions achieved by the learners. Therefore, it is a valuable teaching instrument to control student learning, as well as a means of information to make a value judgment on the academic activity carried out in order to review and reorient it, supported by the processes of self-assessment, co-assessment and hetero-assessment.

On the other hand, several years ago De Ketele (1988, p. 5), cited in Arribas Estebaranz, (2017), wrote:

Evaluation is currently recognized as one of the privileged points to study the teaching-learning process. Addressing the problem of evaluation necessarily means addressing all the fundamental problems of pedagogy. The more we penetrate into the domain of evaluation, the more we become aware of the encyclopedic nature of our ignorance and the more we question our uncertainties. Each question raised leads to others. Each tree is linked to another and the forest appears immense. (p.382)

In this order of ideas, if a student were asked what evaluation means to him, the most likely reaction is: exams! Tests! But if you ask a teacher, within what I could answer something like: it is one of the most complicated aspects of the educational process, because I have received little training and it requires a lot of time to plan the evaluation tools and I am not paid for the extra hours it requires! (Sánchez Mendiola, 2018).

There are other definitions of evaluation, one of the most used is: “Generic term that includes a range of procedures to acquire information about student learning, and the formation of value judgments regarding the learning process” (Miller, 2012, cited by Sánchez Mendiola, 2018, p.3).

Miller (2012), cited in Sánchez Mendiola (2018), presents some recommendations so that the evaluation of learning is carried out appropriately:

Clearly specifying what is going to be evaluated is essential.

Evaluation is a means to an end, not an end in itself.

Learning assessment methods should be chosen for their relevance to the student characteristics to be assessed.

Requires a variety of procedures and instruments.

Its proper use requires awareness of its purpose and the benefits and limitations of each method.

These contributions lead us to propose that evaluation has historically been constituted as an ideal instrument of selection and control. From its beginnings, evaluation tried to specify forms of individual control in addition to its extension to forms of social control.

Consequently, evaluation in primary education must reflect three situations that are considered crucial to determine the reference of this work, one represents the information from teachers in the evaluation commissions, about the current situation in students who register difficulties. to achieve progress in their learning, another related to what parents expressed about the evaluation carried out on their children and finally what concerns the students’ feelings regarding the way they are evaluated.

Tamayo Valencia et al., (2017), point out that the evaluation process is a social practice institutionalized in the classroom, related to the training purposes that are pursued through teaching and learning processes, supported by Dewey’s approaches, education fulfills two functions directed towards the orientation of child development processes, as well as socialization in the cultural heritage of humanity.

It is important to highlight a study on the evaluation practices that have prevailed from 2010 to the first half of 2016, in five countries (Argentina, Ecuador, Mexico, Uruguay and Chile), in five categories (Category 1: Conceptions: approach, forms and types of evaluation of evaluation practices; Category 2: Legal aspects: Policy and legislation, Category 3: Methodological aspects: Why, what and how it is evaluated in evaluation practices; Category 4: Tensions: Relationships and criticisms and Category 5: Effects; and incidence).

Another important reference for the evaluation model, in terms of conceptual methodology, is Tobón (2013), who conceives evaluation from the assessment of competency-based learning, which constitutes moving from an emphasis on specific and factual knowledge to an emphasis on comprehensive actions in the face of a contextual problem. From socio-formation, the concept of assessment is proposed to highlight the appreciative nature of the evaluation, the error in this approach is assumed as an opportunity for improvement and personal growth.

Within the 8 axes that the aforementioned author proposes as central to the concept of evaluation as assessment, for the purposes of this study, the methodology axis is considered, described as: The evaluation of competencies carried out through the following elements methodological:

Resolution of context problems.

Determination of the level of performance based on criteria, evidence and evaluation instruments.

Establishment of achievements and actions to improve.

For Gonzáles Loayza (2016), success in evaluation consists of this process generating the acquisition of competence at an acceptable to higher level of performance.

According to Cano (2014); Castillo Arredondo and Cabrerizo Diago (2010); Delgado García and Oliver Cuello (2009); Ortega Paredes (2015), and other evaluation specialists, the evaluation of learning is based on a process that must be guided by systemic intentional practices that will allow the states of competency development to be perfected.

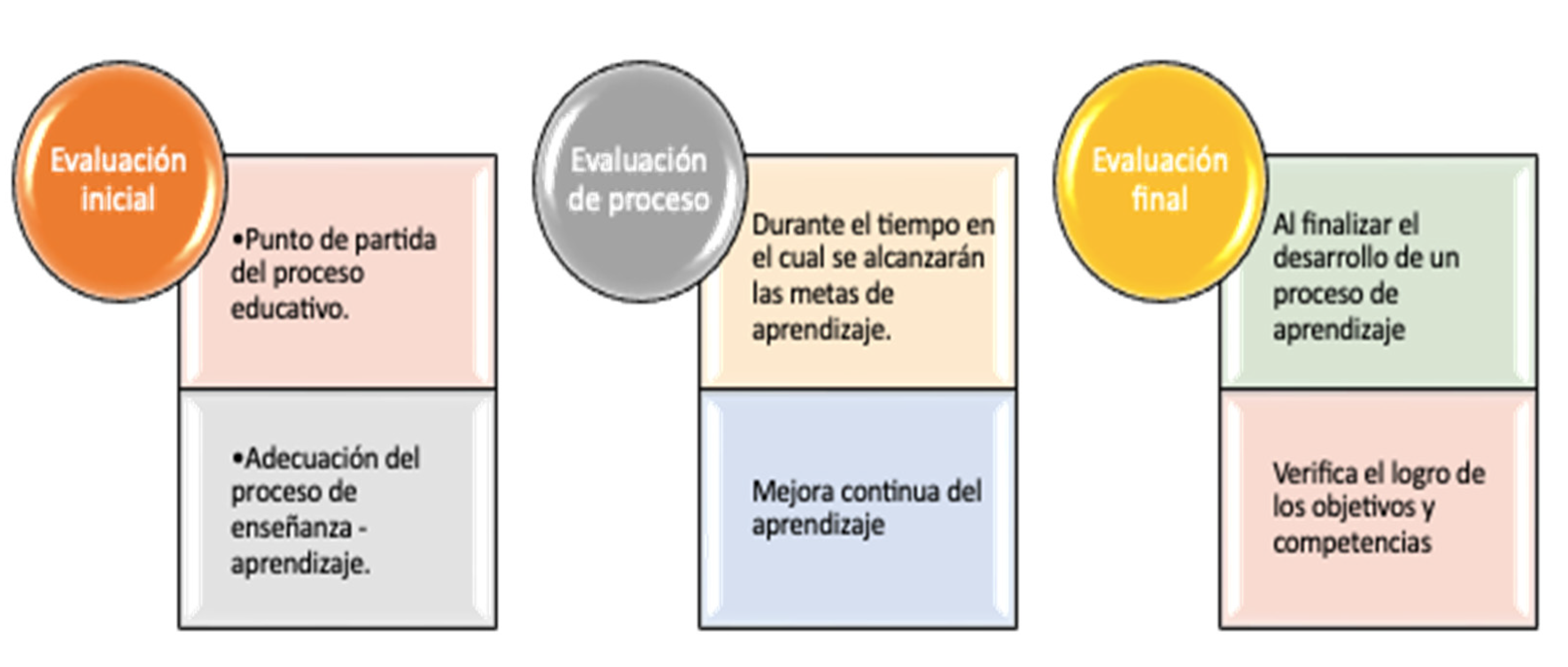

In this sense, three phases are considered in any educational process: At the beginning, during the process and at the end of the teaching process. In this way, in every competency evaluation the following phases are distinguished:

- a)

Initial evaluation: According to Castillo Arredondo and Cabrerizo Diago (2010), it evaluates the knowledge and abilities prior to the beginning of a teaching and learning process. Also, it is used as a diagnostic evaluation at the beginning of each learning activity. In this sense, it allows us to predict difficulties and successes in the development of skills.

- b)

Process evaluation: It is carried out throughout the execution of the curricular program, in such a way that it works as a strategy to improve educational processes. It is continually associated with formative evaluation, because it is applied during the teaching-learning process (Castillo Arredondo & Cabrerizo Diago, 2010).

- c)

Final evaluation: It is contextualized at the end of the teaching-learning process of a learning activity. Its purposes are basically aimed at verifying the degree of assimilation of the skills by the student. It allows value judgments to be generalized within the evaluation period (Castillo Arredondo & Cabrerizo Diago, 2010).

- d)

the following

Figure 1, it is possible to see the basic characteristics of the evaluation stages, from the perspective of the educational process:

Methodology

The research that gave rise to this work is based on the hypothetical-deductive method, which seeks, through procedures, to find the demonstration of the proposed hypothesis. But inductive is also used through some qualitative techniques. It is important to highlight that in this work, we start from constructivism not only as a pedagogical model, but also as a theory of knowledge from an epistemic point of view. (Pelekais et al., 2016).

Due to the characteristics of this study, it is based on a mixed approach, since the variables involved are analyzed using both the deductive and inductive methods, as Hernández-Sampieri & Mendoza (2018) points out, “mixed methods represent a set of systematic, empirical and critical research processes and involve the collection and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data” (p. 546). That is, qualitative analysis is used starting from particular cases studied in depth to then generalize results, with subjectivity prevailing.

To select the participants, non-probabilistic or directed sampling was used; the inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined in accordance with the stated objectives (Cea, 2001), cited by Pelekais et al., (2015). Although, one of the drawbacks noted for this form of sampling is that it is not possible to generalize the results, as it is a sample that is not representative of the population, making it appropriate for research with groups with specific characteristics, or when the size is unknown. of the universe, as is the case of this work, where the teaching processes are studied with respect to the applied evaluation practices. The population object of the interview and the surveys correspond to the teachers, directors and primary education students of schools in the Corregimiento of Juan Demóstenes Arosemena, District of Arraiján. The distribution is shown in

Table 1 below:

For the selection of the sample, three fundamental aspects are considered: Representativeness, which allows the results of the study to be generalized to the rest of the population. The size, which guarantees said representativeness (Latorre et al., 2017).

In this sense, it was necessary to choose the district that had a considerable number of urban basic schools in the Province of Panamá Oeste. To this end, the Ministry of Education of the Panama West Region was requested to invite basic education teachers, specifically those who attend sixth grade at educational centers in the Juan Demóstenes Arosemena District, District of Arraiján, to additionally have their consent and assent both parents and students.

Likewise, two types of sampling were carried out, one probabilistic and the other non-probabilistic. Both samples were extracted from the aforementioned population. The sample size of the students was determined using the formula proposed by Briones (2002), with a confidence level of 95%. The calculation of the required real size of the teacher population, considering a maximum experimental error of 5%, using the following formula:

The sum of the sample from each school forms the total sample “n” of 109 students. In this way, the sample obtained through stratified probability sampling was composed as follows (See

Table 2):

In this study, the following actions are developed for the collection and analysis of data to describe the models and practices used by teachers to assess the learning achieved by students. The qualitative technique is used for content analysis, through a checklist matrix, with the criteria of the instruments that were desired to be analyzed.

For its quantitative analysis, the survey was used as an instrument for collecting information, which was structured by 11 items with open and closed questions for teachers, one of 14 open and closed questions addressed to sixth grade students the five (5) educational centers, in the same way for the managers an instrument made up of 12 questions.

Results and Discussion

The results of the analysis of the information collected through the Survey for teachers, students and managers on evaluation models and practices are presented in order to analyze the evaluation process carried out by primary education teachers in the Juan Demóstenes Arosemena district of the Arraiján District. All this analysis must allow us to verify the good evaluation practices that teachers at this educational level develop to improve students’ skills.

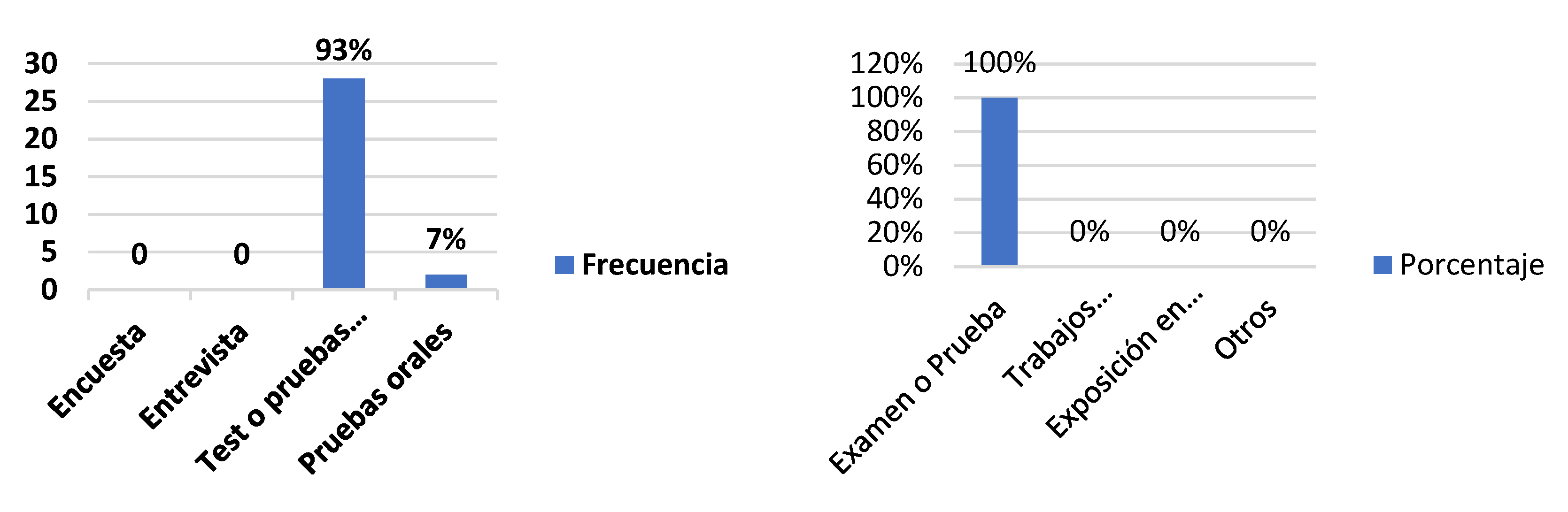

Regarding the models and practices used by teachers, the graphs are presented according to the evaluation instruments most frequently used in the advancement of knowledge. (See

Figure 2)

The comparison of these figures shows both the opinion of teachers and students on the evaluation instruments most frequently used to verify the achievement of learning; it is evident that they correspond to tests or exams, limiting the range of instruments that They allow students to truly assess whether they managed to achieve the learning of the thematic axes presented to them.

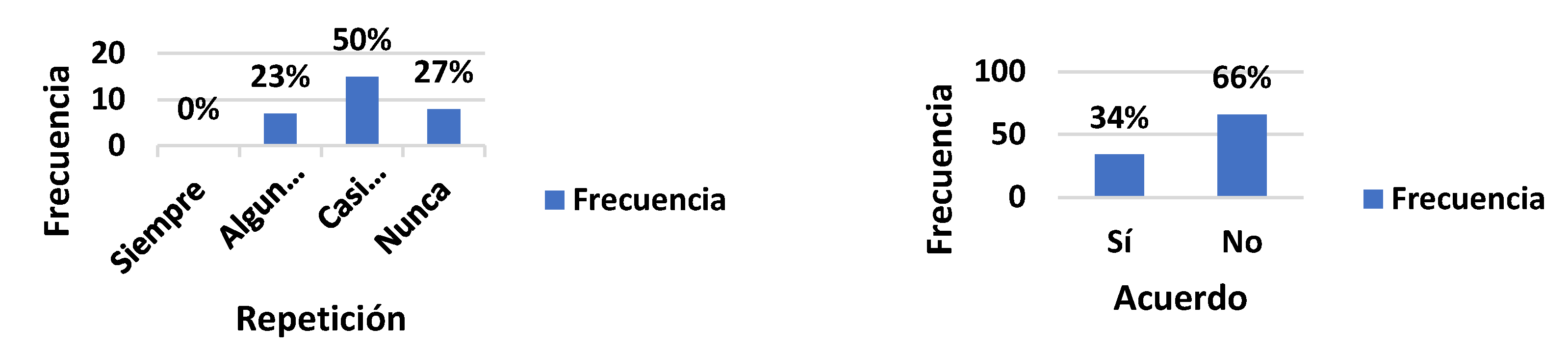

Below are other important aspects to highlight, regarding the evaluation models and practices used by teachers. When consulting them about the self-reflection processes towards the achievement of learning, the following results were obtained (See

Figure 3):

As can be seen in the graphs, the reflection process to verify the achievement of learning is not a frequent practice used by teachers, an element that allows revealing and evidencing the feelings and conceptions of the students in relation to the achievements achieved and those that require strengthening, seeking to promote reflection on the benefits and importance of the evaluation process.

Another aspect to consider refers to the participation of students when selecting the evaluation instruments. This approach shows the opinions of the teaching staff and students. (See

Figure 4)

As can be seen, 50% of the teachers do not consider within their evaluation practices to attend to suggestions of the type or evaluation instrument to be used, while 100% of the students state that they are not considered when choosing the types or forms of evaluation.

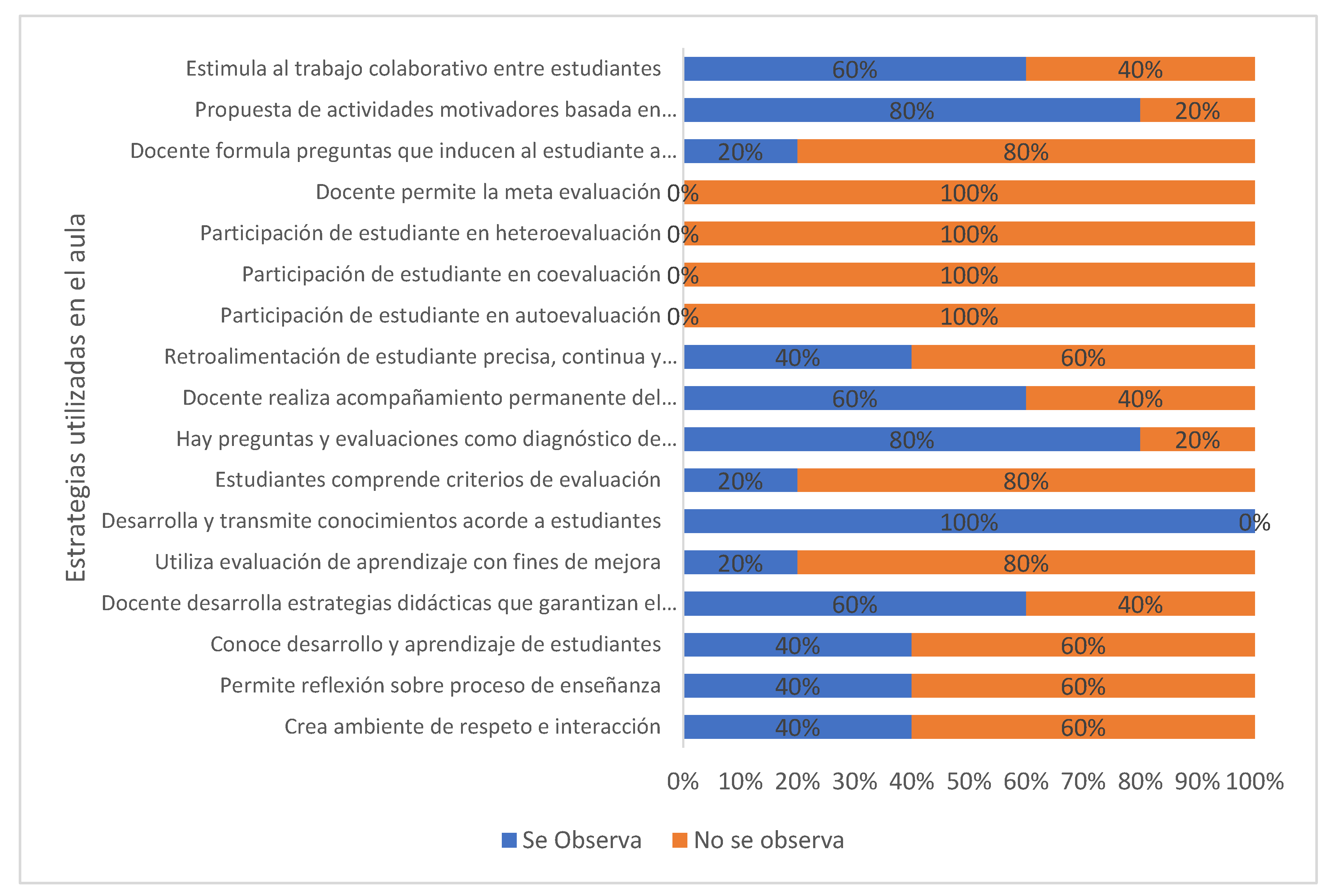

According to the establishment of the criteria for structuring a planning matrix and rubric for monitoring evaluation practices, the most notable results are shown, collected through the observation guide.

Taking into account this objective, an observation guide was developed that allows us to demonstrate the evaluation practices in the educational centers involved in the study, where the most relevant aspects to highlight show that only 40% of the teachers create an environment of respect and interaction and allow reflection on the teaching process, however, 60% do not allow these actions aimed at improving their practices. Another significant finding is the fact that only 20% of teachers use learning evaluation for improvement purposes, 80% use it to measure their students’ knowledge, and this reality is complemented by the fact that the same percentage 20% use questions and evaluations as a diagnosis in their actions.

Furthermore, it is of great relevance to indicate that no teacher encourages the participation of students in self-assessment, co-assessment or hetero-evaluation processes as fundamental tools for improving their teaching practices and evaluation of their students’ learning.

These results coincide with what is evidenced by Vázquez Garrido (2022), who states that the evaluation carried out by teachers is a fundamental function to guide the teaching-learning process of the students under their charge.

Regarding the students’ perception of the strategies used in the evaluation by their teachers, the results obtained are shown. (See

Figure 5)

The results show the perception that students have regarding the evaluation strategies used by their teachers, which they consider are not the most appropriate, highlighting that 66% of them indicate that teachers do not use the resolution of exams or tests to clarify doubts, nor do they allow suggestions or contributions on the form of evaluation, a response from 100% of the students who indicate that their teachers do not take them into consideration for these aspects. Likewise, 100% show interest in applying evaluation processes in classroom activities among peers and 96% indicate that they are interested in knowing about this type of evaluation, which would allow an assessment of the teaching actions and in this way improve their practices.

The need to incorporate evaluation tools is defined where it is evident that the evaluation practices carried out by the teacher very rarely point to the use of evaluations based on criteria, it is commonly normative, for its part the correction criteria to evaluate They are almost never known by students and the teaching verification of planned objectives based on control instruments does not constitute a priority in teachers’ evaluation practices either.

Taking into consideration the results obtained, it is supported that the improvement of learning evaluation models and practices implemented by primary teachers favor the improvement of students’ performance and competencies.

Conclusions

It can be indicated that there is an evident contradiction in what is said and what is done in the evaluation, where they stated that they use a greater number of written tests and traditional exams, not being consistent with the approach focused on the process, the which tends to generate improvement actions

A good practice is highlighted by promoting the use of various evaluation techniques. Faced with this position, it was established that there is no adequate combination of techniques that allow the teacher to significantly appreciate the effect of student learning.

Regarding the importance given to evaluation, it is another characteristic in which there are also significant differences between teachers who give greater importance to evaluation in evaluation practices and models, than those who do not.

Likewise, the only way to change evaluation practices is through motivation towards a change in attitude, where the level of competence that teachers possess is not decisive in the quality of their practices, because despite receiving training or having With information, traditional evaluation practices are maintained, and finally, it is important to highlight that greater knowledge and training in evaluation allows us to improve the development of good evaluation practices.

It can be indicated that this coincides with the approaches of authors who point out that one of the most important elements in evaluation is the training that the teacher has, favoring having tools on how to self-evaluate and know how to evaluate. Given this, the only way to change evaluation practices is through motivation for a change in the teacher’s attitude where greater theoretical and conceptual support for evaluation is promoted, to the extent that the teacher can count on the tools necessary will be able to offer greater opportunities to improve not only the learning of its students, but also of themselves.

References

- Arias, S., Labrador, N., & Gámez, B. (2019). Models and times of educational evaluation. Educere, 23 (75): 307-322. University of the Andes. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=35660262007.

- Arribas Estebaranz, J. Mª (2017). The evaluation of learning. Problems and solutions. Faculty. Journal of Curriculum and Teacher Education, 21(4), 381-404. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=56754639020.

- Barragán Sánchez, R. (2005). The Portfolio, evaluation and learning methodology for the new European Higher Education Area. A practical experience at the University of Seville. Latin American Journal of Educational Technology - RELATEC, 4(1), 121-140. https://idus.us.es/bitstream/handle/11441/16833/file_1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Briones, G. (2002). Methodology of quantitative research in the social sciences. Social Research Modules. https://metodoinvestigacion.files.wordpress.com/2008/02/metodologia-de-la-investigacion-guillermo-briones.pdf.

- Cano, E. (2014). Good practices in competency assessment. Five cases of higher education. Laertes Education.

- Casanova Rodríguez, M. (2022), What is evaluation? Basic concepts, Course: Assessment of competencies through performance, National Institute of Educational Technologies and Teacher Training, Ministry of Education and Vocational Training. INTEF Online Training and Educational Digital Competence Area. This course and its materials are distributed under a Creative Commons 4.0 license.

- Castillo Arredondo, S. & Cabrerizo Diago, J. (2010). Educational evaluation of learning and competencies. Pearson Education.

- Coll, C., Mauri, T., & Rochera, M. J. (2012). Assessment practice as a context for learning to be a competent learner. Faculty. Journal of Curriculum and Teacher Education, 16(1), 49-59.

- Delgado García, AM. & Oliver Cuello, R. (2009). Interaction between continuous assessment and formative self-assessment: The enhancement of autonomous learning. REDU. University Teaching Magazine. (4):1-13. 1: (4). [CrossRef]

- Fernández, S. (2017). Evaluation and learning. Spanish Foreign Language Didactics Magazine, (24): 1-22. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/921/92153187003/html/.

- García, M. J. M., Castro, A. M. (2017). Research in education, EDITUS, pp. 13-40. http://books.scielo.org/id/yjxdq/epub/mororo-9788574554938.epub.

- Giménez Beut, J. A., Morales Yago, F. J., & Parra Camacho, D. (2021). The use of evaluation instruments in Primary Education: Case analysis in educational centers in the province of Valencia (Spain). Educatio Siglo XXI, 39(2), 193–212. [CrossRef]

- Gonzáles Loayza, C del R. (2016). Planning the evaluation of learning in the general courses of a faculty of education at a university in Lima. Master’s Thesis in Education, with mention in the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru curriculum. https://tesis.pucp.edu.pe/repositorio/bitstream/handle/20.500.12404/7810/GONZALES_LOAYZA_CARMEN_PLANIFICACION_EVALUACION%20%281%29.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Hernández-Sampieri, R. & Mendoza, C. (2018). Investigation methodology. The quantitative, qualitative and mixed routes. McGraw Hill Education.

- Ortega Martínez, S., Cáceres Mesa, M., Moreno Tapia, M., Chong Barreiro, M., & García Robelo, O. (2021). Considerations on formative assessment practices in primary education. A case study. Metropolitan Journal of Applied Sciences, 4(3) 114-122. https://remca.umet.edu.ec/index.php/REMCA/article/view/445/465.

- Ortega Paredes, M. (2015). Formative evaluation applied by teachers in the area of science, technology and environment in the Hunter district in Arequipa. Thesis in Educational Sciences with a Mention in Didactics of Teaching in Natural Sciences in Secondary Education Cayetano Heredia University. https://repositorio.upch.edu.pe/bitstream/handle/20.500.12866/118/Evaluaci%C3%B3n.formativa.aplicada.por.los.docentes.del.%C3%A1rea.de.Ciencia.Tecnolog %C3%ADa.and.Ambiente.in.the.district.of.Hunter.Arequipa.pdf.

- Pelekais, C., Pertuz, F., & Pelekais, E. (2016). Towards a culture of qualitative research. Astro Data Editions S.A.

- Pelekais, C., El Kadi, O., Seijo, C., & Neuman, N. (2015). The ABC of Research. Pedagogical Guideline. Astro Data Editions S.A.

- Rosales, M. (2015). Evaluation process: Summative evaluation, formative evaluation and Assessment their impact on education. Ibero-American Congress of Science, Technology, Innovation and Education. https://www.academia.edu/40282888/Proceso_evaluativo_evaluaci%C3%B3n_sumativa_evaluaci%C3%B3n_formativa_y_Assesment_su_impacto_en_la_educaci%C3%B3n_actual.

- Sánchez Mendiola, M. (2018). Assessing student learning: Is it really that complicated? University Digital Magazine, 19(6): 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Tamayo Valencia, L., Niño Zafra, L., Cardozo Espitia, L., & Bejarano Bejarano, O. (2017). Where is the evaluation going? Conceptual contributions to think about and transform evaluation practices. IDEP Research Series. https://repositorio.idep.edu.co/bitstream/handle/001/923/Hacia%20donde%20va%20la%20evaluacion.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Tobón, S. (2013). Comprehensive training and skills. Complex thinking, curriculum, didactics and evaluation. ECOE Editorial https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319310793_Formacion_integral_y_competencias_Pensamiento_complejo_curriculo_didactica_y_evaluacion.

- Vázquez Garrido, E. (2022). Evaluation techniques in primary and secondary education. Doctoral Thesis in Education. University of Valencia. https://roderic.uv.es/bitstream/handle/10550/83301/ENCARNA%20VAZQUEZ%20GARRIDO%20TESIS%20DOCTORAL.pdf?sequence=1.

- Vera, H. & González-Ledesma, M. (2018). Quality and evaluation: Marriage of heaven and hell. Educational Profiles, 40, 53-97. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0185-26982018000500053&lng=es&tlng=es.

- Ydesen, C. & Andreasen, K. E. (2019). The historical background of the global evaluation culture in the field of education. Education Forum, 17(26), 1-24. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).