Submitted:

28 May 2024

Posted:

29 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Gross Evaluation and Sample Collection

2.2. APP Bacterial Isolation

2.3. DNA Extraction and Multiplex PCR

2.4. Histopathological Evaluation

2.5. Microbiological Investigations

3. Results

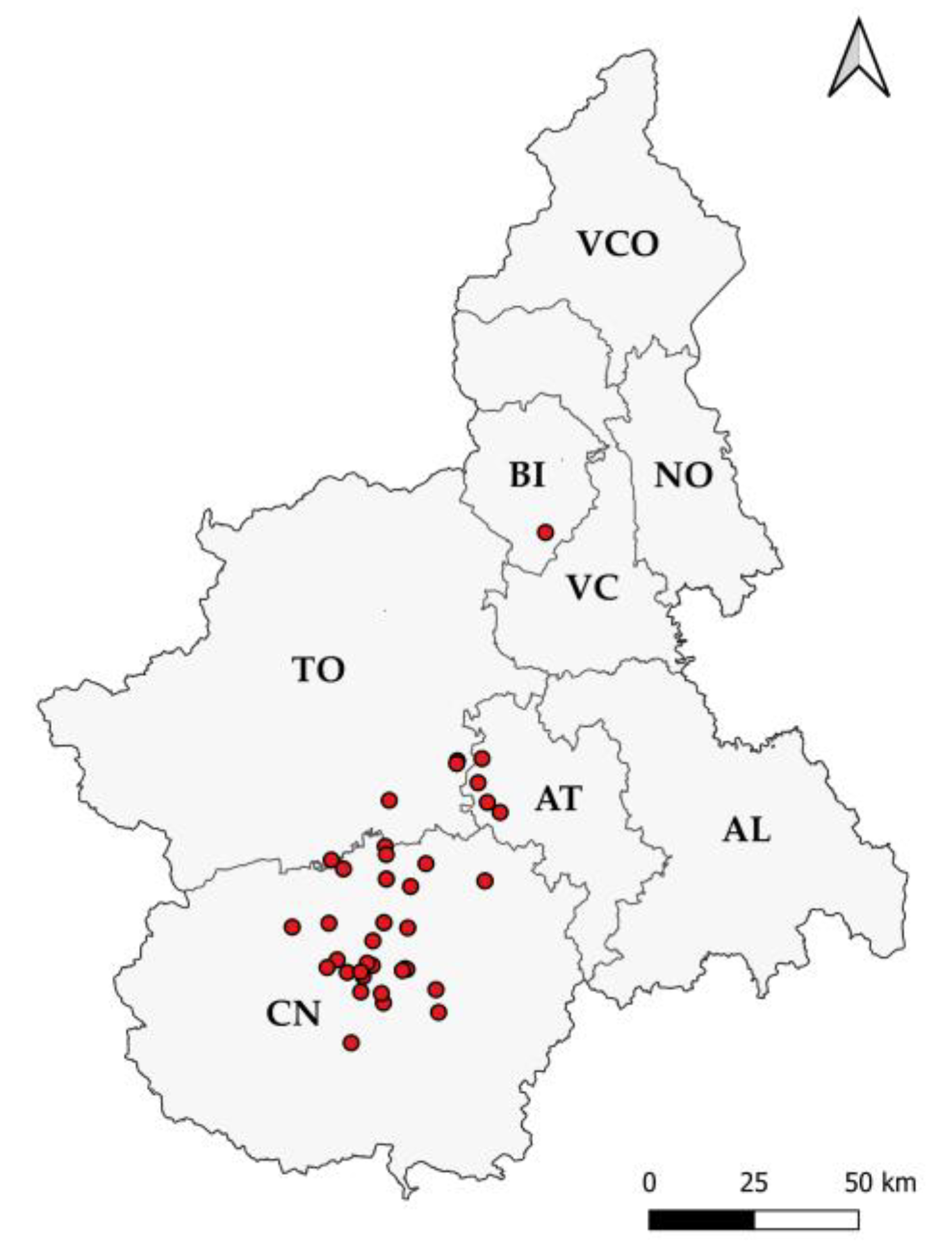

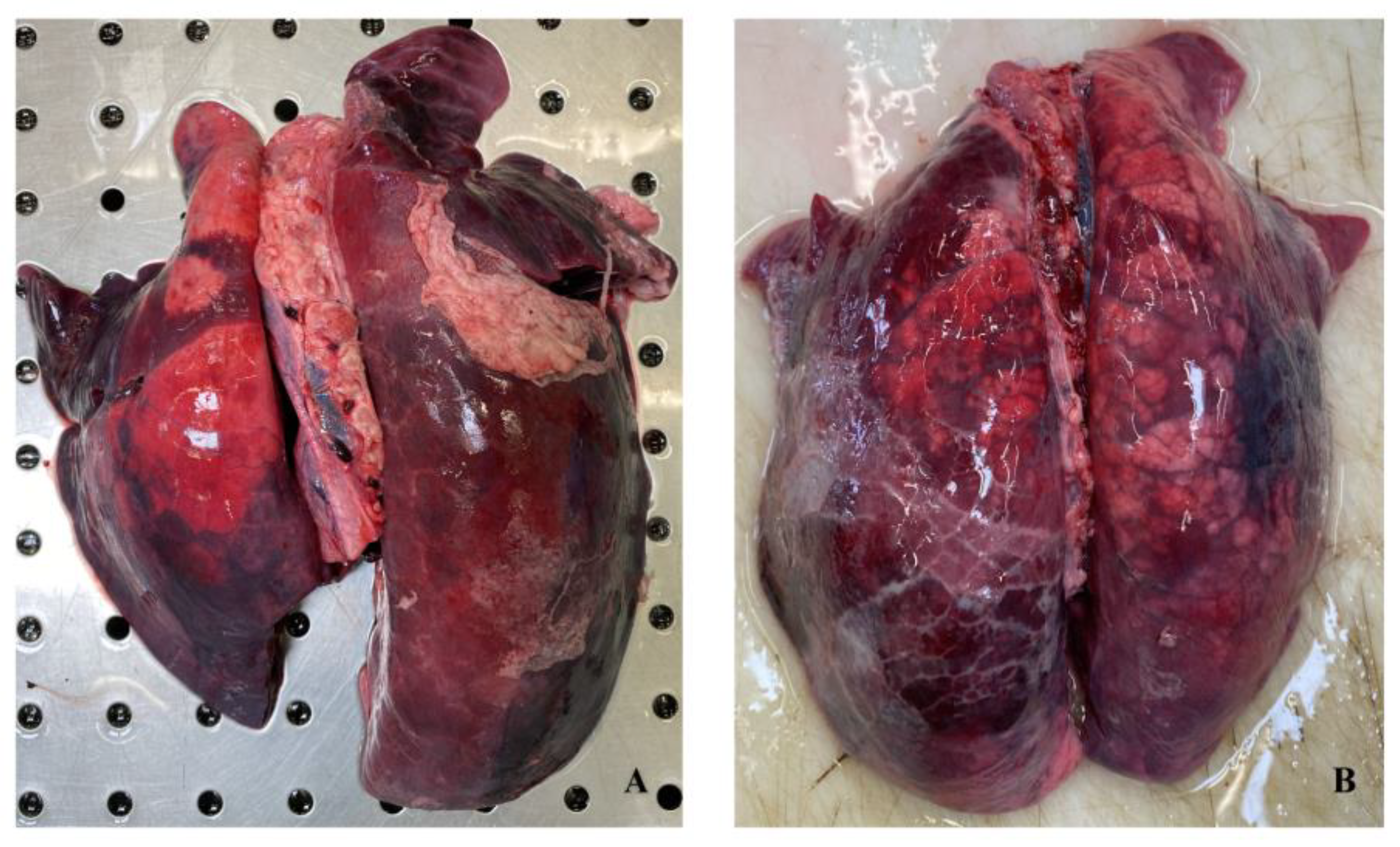

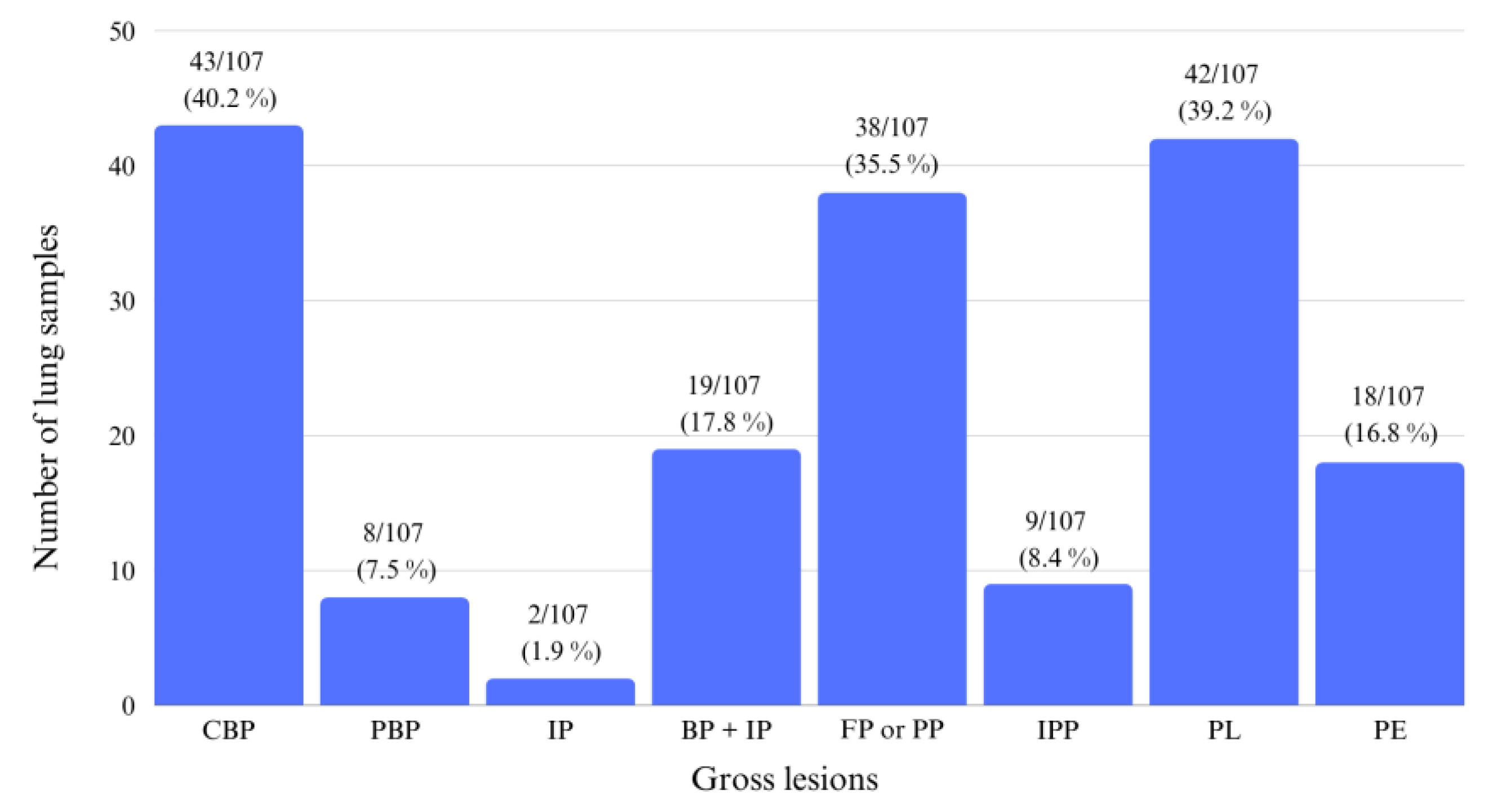

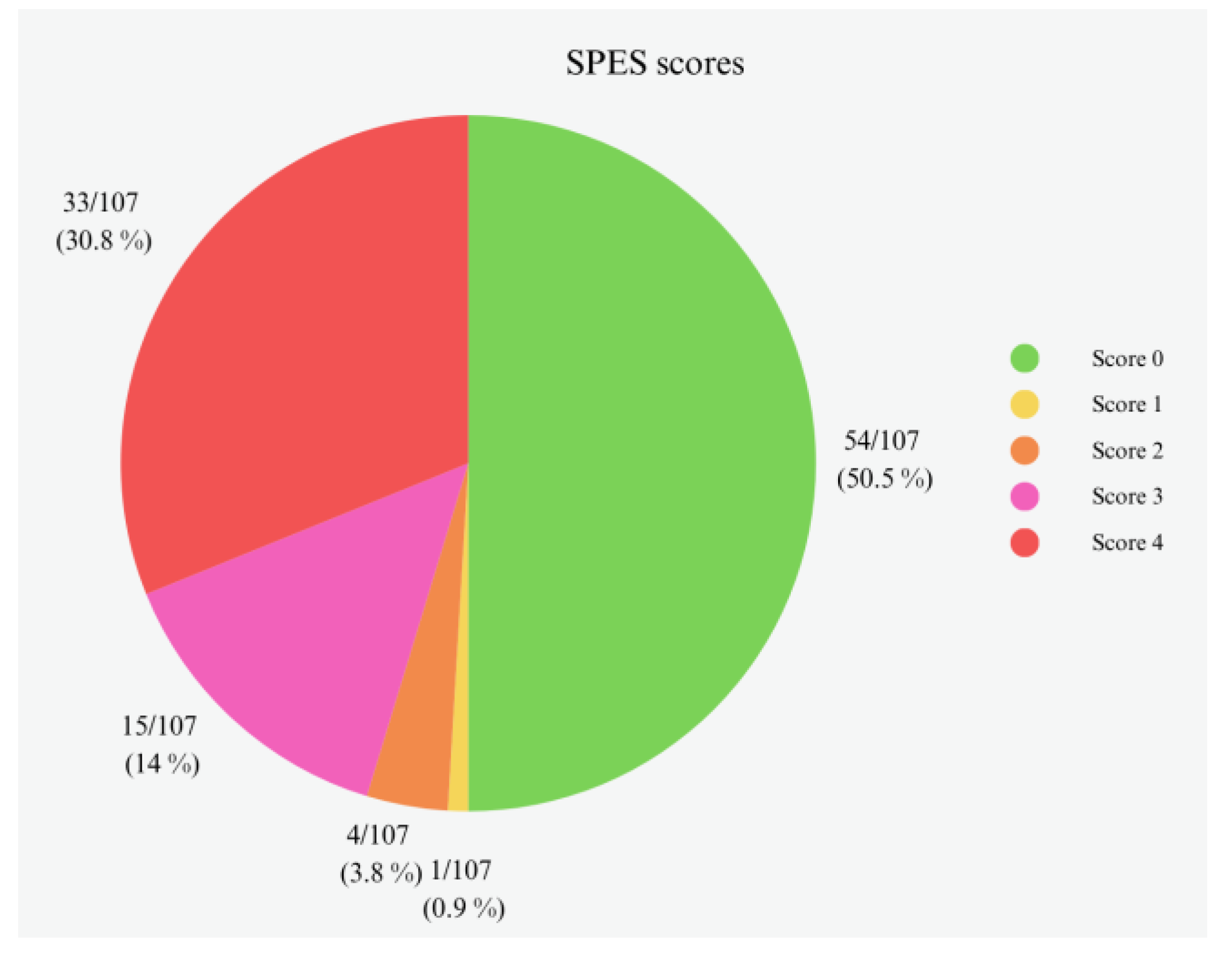

3.1. Gross Evaluation

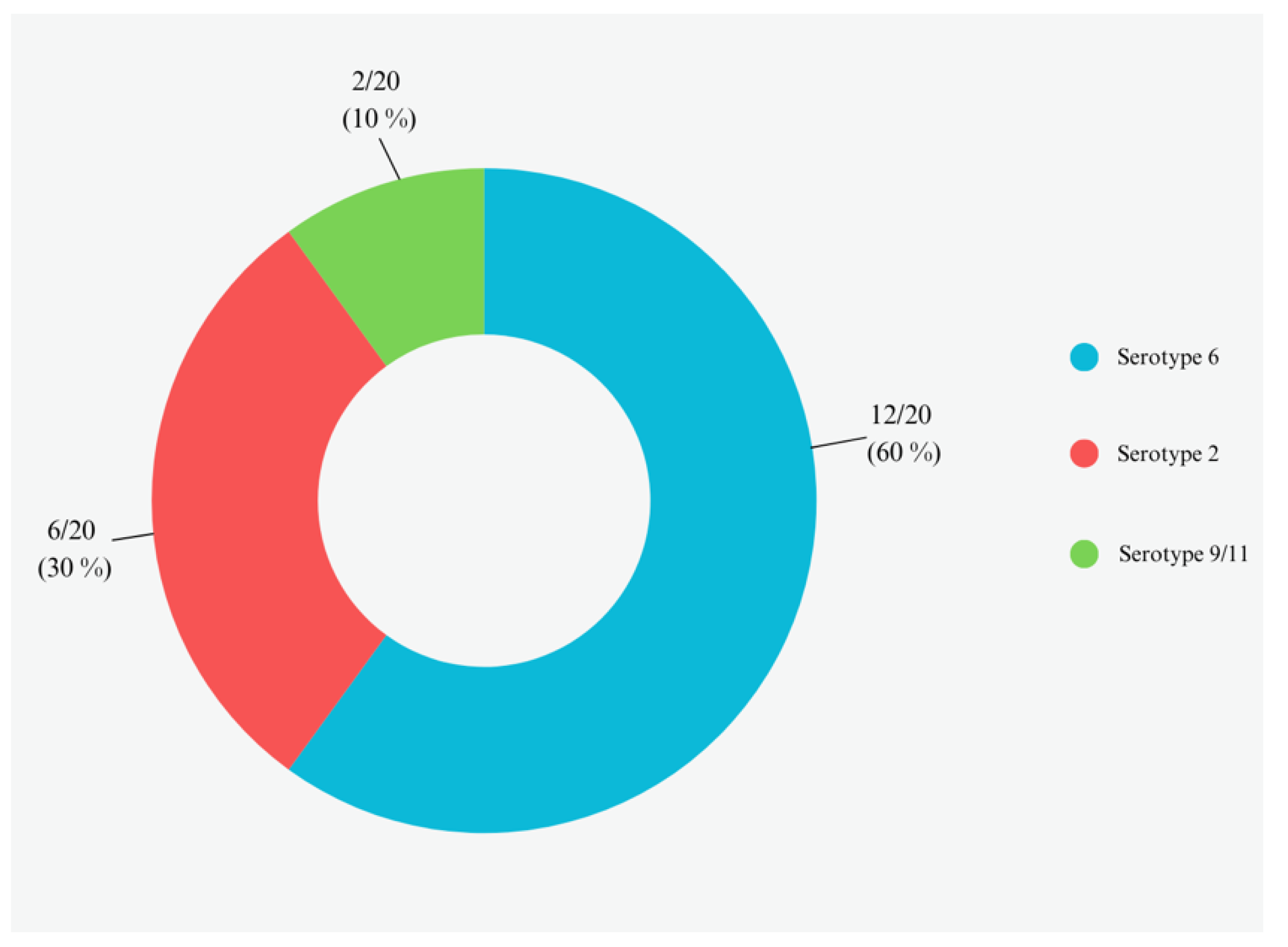

3.2. APP Bacterial Isolation and Serotypes Assignment by Multiplex PCR

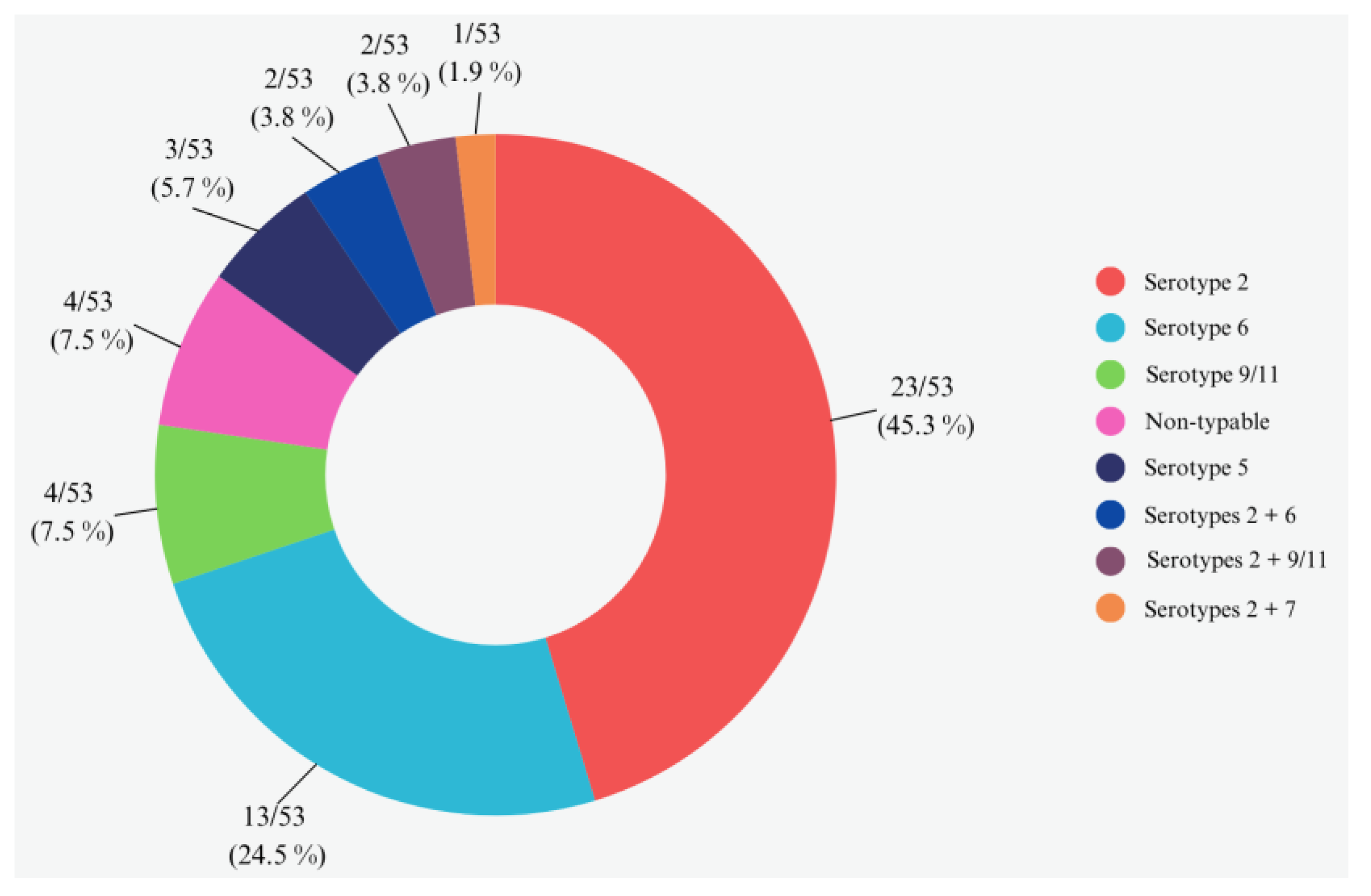

3.3. Serotypes Assignment by Multiplex PCR without Bacterial Culture

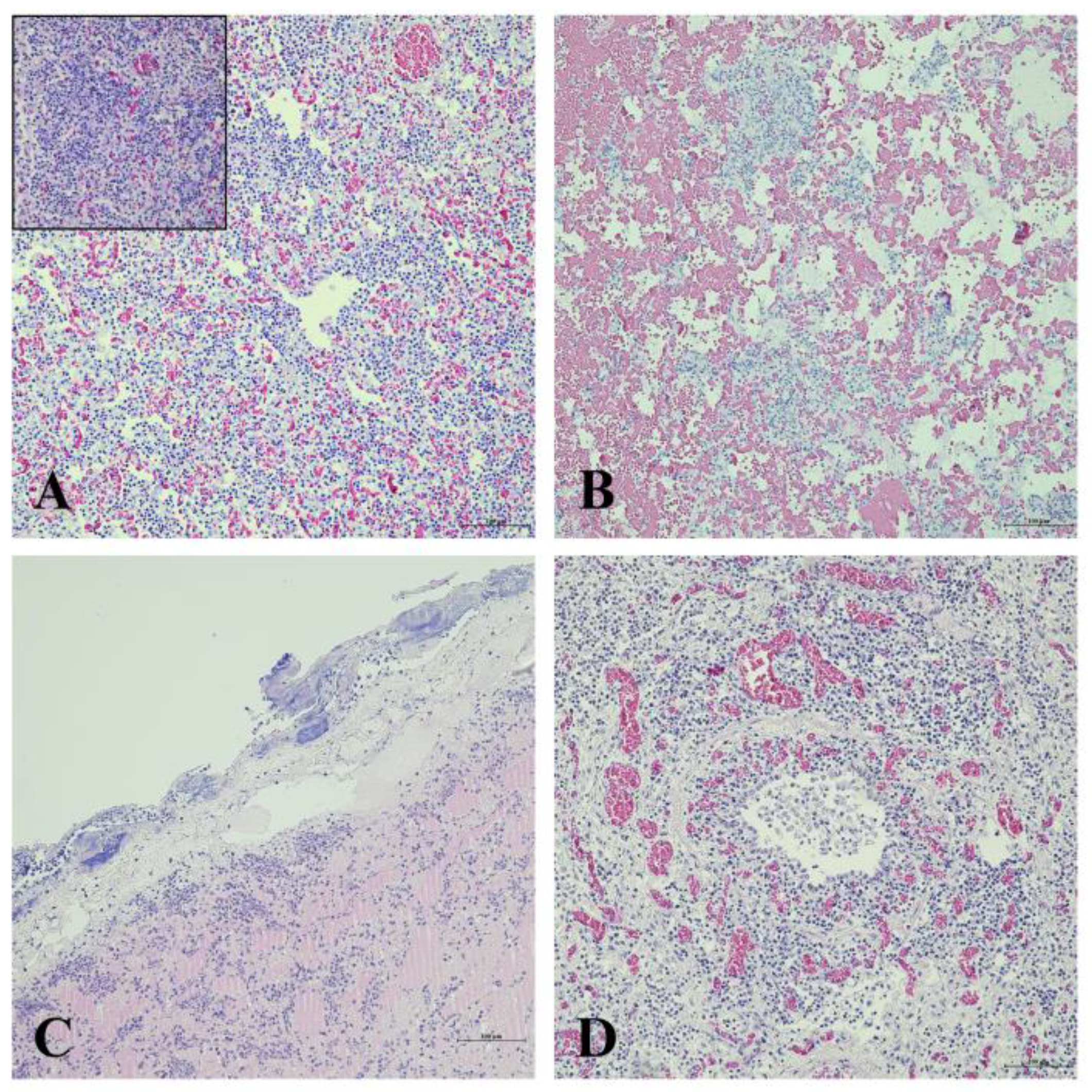

3.4. Histopathological Evaluation

3.5. Microbiological Investigations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Konze, S.A.; Abraham, W.R.; Goethe, E.; Surges, E.; Kuypers, M.M.M.; Hoeltig, D.; Meens, J.; Vogel, C.; Stiesch, M.; Valentin-Weigand, P.; et al. Link between Heterotrophic Carbon Fixation and Virulence in the Porcine Lung Pathogen Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae. Infection and Immunity 2019, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmer, I.; Salomonsen, C.M.; Jorsal, S.E.; Astrup, L.B.; Jensen, V.F.; Høg, B.B.; Pedersen, K. Antibiotic Resistance in Porcine Pathogenic Bacteria and Relation to Antibiotic Usage. BMC Veterinary Research 2019, 15, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacominelli-Stuffler, R.; Marruchella, G.; Storelli, M.M.; Sabatucci, A.; Angelucci, C.B.; Maccarrone, M. 5-Lipoxygenase and Cyclooxygenase-2 in the Lungs of Pigs Naturally Affected by Enzootic Pneumonia and Porcine Pleuropneumonia. Research in veterinary science 2012, 93, 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srijuntongsiri, G.; Mhoowai, A.; Samngamnim, S.; Assavacheep, P.; Bossé, J.T.; Langford, P.R.; Posayapisit, N.; Leartsakulpanich, U.; Songsungthong, W. <italic>Novel DNA Markers for Identification of Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae</italic>; 2022;

- Stringer, O.W.; Li, Y.; Bossé, J.T.; Langford, P.R. JMM Profile: Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae: A Major Cause of Lung Disease in Pigs but Difficult to Control and Eradicate. Journal of Medical Microbiology 2022, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sárközi, R.; Makrai, L.; Fodor, L. Isolation of Biotype 1 Serotype 12 and Detection of Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae from Wild Boars. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, R.; Hao, X.; Han, Q.; Wang, J.; Yuan, W. Direct Detection of Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae in Swine Lungs and Tonsils by Real-Time Recombinase Polymerase Amplification Assay. Molecular and Cellular Probes 2019, 45, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sassu, E.L.; Bossé, J.T.; Tobias, T.J.; Gottschalk, M.; Langford, P.R.; Hennig-Pauka, I. Update on Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae—Knowledge, Gaps and Challenges. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 2018, 65, 72–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stringer, O.W.; Bossé, J.T.; Lacouture, S.; Gottschalk, M.; Fodor, L.; Angen, Ø.; Velazquez, E.; Penny, P.; Lei, L.; Langford, P.R.; et al. Proposal of Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae Serovar 19, and Reformulation of Previous Multiplex PCRs for Capsule-Specific Typing of All Known Serovars. Veterinary Microbiology 2021, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipos, W.; Cvjetković, V.; Dobrokes, B.; Sipos, S. Evaluation of the Efficacy of a Vaccination Program against Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae Based on Lung-scoring at Slaughter. Animals 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraldi, T.G.; Cruz, N.R.N.; Pereira, D.A.; Galdeano, J.V.B.; Gatto, I.R.H.; Silva, A.F.D.; Panzardi, A.; Linhares, D.C.L.; Mathias, L.A.; De Oliveira, L.G. Antibodies against Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae, Mycoplasma Hyopneumoniae and Influenza Virus and Their Relationships with Risk Factors, Clinical Signs and Lung Lesions in Pig Farms with One-Site Production Systems in Brazil. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2019, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer, O.W.; Bossé, J.T.; Lacouture, S.; Gottschalk, M.; Fodor, L.; Angen, Ø.; Velazquez, E.; Penny, P.; Lei, L.; Langford, P.R.; et al. Rapid Detection and Typing of Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae Serovars Directly From Clinical Samples: Combining FTA® Card Technology With Multiplex PCR. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, R.; Roychoudhury, P.; Kumar, S.; Dutta, S.; Konwar, N.; Subudhi, P.K.; Dutta, T.K. Rapid Detection of Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae Targeting the apxIVA Gene for Diagnosis of Contagious Porcine Pleuropneumonia in Pigs by Polymerase Spiral Reaction. Letters in applied microbiology 2022, 75, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, M.S.; Matias, D.N.; Poor, A.P.; Dutra, M.C.; Moreno, L.Z.; Parra, B.M.; Silva, A.P.S.; Matajira, C.E.C.; de Moura Gomes, V.T.; Barbosa, M.R.F.; et al. Causes of Sow Mortality and Risks to Post-Mortem Findings in a Brazilian Intensive Swine Production System. Animals : an open access journal from MDPI 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, M.; Won, H.; Shin, M.K.; Oh, M.W.; Shim, S.; Yoon, I.; Yoo, H.S. Development of Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae ApxI, ApxII, and ApxIII-Specific ELISA Methods for Evaluation of Vaccine Efficiency. Journal of Veterinary Science 2019, 20, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørenson, V.; Jorsal, S.E.; Mousing, J. Diseases of the Respiratory System. In Diseases of Swine; Blackwell Publishing Professional: 2121 State Avenue, Ames, Iowa 50014, USA, 2006; pp. 149–178. ISBN 978-0-8138-1703-3. [Google Scholar]

- Madec, F.; Derrien, H. Frequency, Intensity and Localization of Pulmonary Lesions in Bacon Pigs : Results of a First Series of Observations at the Slaughter-House. Annales de zootechnie 1981, 30, 380–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madec, F.; Kobish, M. A Survey of Pulmonary Lesions in Bacon Pigs (Observations Made at the Slaughterhouse). Annales de zootechnie 1982, 31, 341–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dottori, M.; Nigrelli, A.D.; Bonilauri, P.; Merialdi, G.; Gozio, S.; Cominotti, F. Proposta di un nuovo sistema di punteggiatura delle pleuriti suine in sede di macellazione. La griglia S.P.E.S. (Slaughterhouse Pleuritis Evaluation System). Large Animal Review 2007, 13, 161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Maes, D.; Sibila, M.; Pieters, M.; Haesebrouck, F.; Segalés, J.; de Oliveira, L.G. Review on the Methodology to Assess Respiratory Tract Lesions in Pigs and Their Production Impact. Veterinary Research 2023, 54, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- To, H.; Konnai, M.; Teshima, K.; Tsutsumi, N.; Ito, S.; Sato, M.; Shibuya, K.; Nagai, S. Pulmonary Lesions with Asteroid Bodies in a Pig Experimentally Infected with Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae Serovar 15. J Vet Med Sci 2023, 85, 1131–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibila, M.; Aragón, V.; Fraile, L.; Segalés, J. Comparison of Four Lung Scoring Systems for the Assessment of the Pathological Outcomes Derived from Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae Experimental Infections. BMC Vet Res 2014, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scollo, A.; Abbas, M.; Contiero, B.; Gottardo, F. Undocked Tails, Mycoplasma-like Lesions and Gastric Ulcers in Slaughtering Pigs: What Connection? Animals 2023, 13, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amatucci, L.; Luise, D.; Luppi, A.; Virdis, S.; Prosperi, A.; Cirelli, A.; Bosco, C.; Trevisi, P. Evaluation of Carcass Quality, Body and Pulmonary Lesions Detected at the Abattoir in Heavy Pigs Subjected or Not to Tail Docking. Porcine Health Management 2023, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatsiros, V.G.; Stylianaki, I.; Tsokana, C.N.; Papakonstantinou, G.; Christophorou, M.; Papaioannou, N.; Athanasiou, L.V. Histopathological Lesions of Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae Serotype 8 in Infected Pigs. Vet Res Forum 2023, 14, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardos, G.; Sárközi, R.; Laczkó, L.; Marton, S.; Makrai, L.; Bányai, K.; Fodor, L. Genetic Diversity of Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae Serovars in Hungary. Veterinary Sciences 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sárközi, R.; Makrai, L.; Fodor, L. Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae Serotypes in Hungary. Acta Veterinaria Hungarica 2018, 66, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, J.; Valls, L.; Martínez, E.; Riera, P. Isolation Rates, Serovars, and Toxin Genotypes of Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide-Independent Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae among Pigs Suffering from Pleuropneumonia in Spain. J VET Diagn Invest 2009, 21, 854–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuwerk, L.; Hoeltig, D.; Waldmann, K.-H.; Valentin-Weigand, P.; Rohde, J. Sero- and Apx-Typing of German Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae Field Isolates from 2010 to 2019 Reveals a Predominance of Serovar 2 with Regular Apx-Profile. Veterinary Research 2021, 52, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šatrán, P.; Nedbalcová, K. Prevalence of Serotypes, Production of Apx Toxins, and Antibiotic Resistance in Strains of Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae Isolated in the Czech Republic. Veterinární medicína 2002, 47, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucerova, Z.; Jaglic, Z.; Ondriasova, R.; Nedbalcova, K. Serotype Distribution of Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae Isolated from Porcine Pleuropneumonia in the Czech Republicduring Period 2003-2004. Veterinární medicína 2005, 50, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bossé, J.T.; Williamson, S.M.; Maskell, D.J.; Tucker, A.W.; Wren, B.W.; Rycroft, A.N.; Langford, P.R. Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae Serovar 8 Predominates in England and Wales. Veterinary Record 2016, 179, 276–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacouture, S.; Gottschalk, M. Distribution of Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae (from 2015 to June 2020) and Glaesserella Parasuis (from 2017 to June 2020) Serotypes Isolated from Diseased Pigs in Quebec. Can Vet J 2020, 61, 1261–1263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gottschalk, M.; Lacouture, S. Canada: Distribution of Streptococcus Suis (from 2012 to 2014) and Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae (from 2011 to 2014) Serotypes Isolated from Diseased Pigs. Can Vet J 2015, 56, 1093–1094. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bossé, J.T.; Li, Y.; Sárközi, R.; Fodor, L.; Lacouture, S.; Gottschalk, M.; Casas Amoribieta, M.; Angen, Ø.; Nedbalcova, K.; Holden, M.T.G.; et al. Proposal of Serovars 17 and 18 of Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae Based on Serological and Genotypic Analysis. Veterinary Microbiology 2018, 217, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, H.; Ogawa, T.; Fukamizu, D.; Morinaga, Y.; Kusumoto, M. Nucleotide Sequence Analysis of a DNA Region Involved in Capsular Polysaccharide Biosynthesis Reveals the Molecular Basis of the Nontypeability of Two Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae Isolates. J VET Diagn Invest 2016, 28, 632–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackall, P.J.; Klaasen, H.L.B.M.; Van Den Bosch, H.; Kuhnert, P.; Frey, J. Proposal of a New Serovar of Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae: Serovar 15. Veterinary Microbiology 2002, 84, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bossé, J.T.; Stringer, O.W.; Hennig-Pauka, I.; Mortensen, P.; Langford, P.R. Detection of Novel Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae Serovars by Multiplex PCR: A Cautionary Tale. Microbiol Spectr 2023, 11, e04461–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Score | Lobe involvement |

|---|---|

| 0 | Absence of lesions |

| 1 | Damaged area <25% |

| 2 | Damaged area 26-50% |

| 3 | Damaged area 51-75% |

| 4 | Damaged area 76-100% |

| Pulmonary lobe | Score (mean ± sd) |

|---|---|

| Left cranial | 1.99 ± 1.41 |

| Left medium | 2.38 ± 1.4 |

| Left caudal | 2.17 ± 1.2 |

| Right cranial | 2.2 ± 1.32 |

| Right medium | 2.64 ± 1.32 |

| Right accessory | 2.42 ± 1.52 |

| Right caudal | 2.26 ± 1.22 |

| Microorganisms | Number of infected individuals (%) |

|---|---|

| PRRSV | 31 (29 %) |

| Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae | 11 (10.3 %) |

| Escherichia coli | 10 (9.3 %) |

| Streptococcus suis | 10 (9.3 %) |

| Pasteurella multocida | 9 (8.4 %) |

| Actinobacillus lignieresii | 5 (4,7 %) |

| Trueperella pyogenes | 4 (3.7 %) |

| Bordetella bronchiseptica | 3 (2.8 %) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 3 (2.8 %) |

| Bordetella bronchiseptica | 1 (1.7 %) |

| Staphylococcus sp. | 1 (1.7 %) |

| Escherichia sp. | 1 (1.7 %) |

| SIV | 1 (1.7 %) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).