1. Introduction

The intricate processes involved in the normal development and maintenance of motor neurons necessitate complex interactions between these neurons and glial cells. The analysis of these interactions in cell culture presents challenges due to the intricate purification and control required for these cell types and their interactions. Of particular importance in such cell cultures is the issue of cell purity, wherein motor neuron preparations typically yield variable purities ranging from 88% to 97%. [

1] Conversely, shared cultures of astrocytes and microglial cells derived from the rodent central nervous system are more readily obtained at high purities exceeding 95%. Despite this, the assessment of purity and the potential for cross-contamination in these cultures remains underexplored. Moreover, the concurrent isolation of motor neurons, astrocytes, and microglial cells from the mouse spinal cord has not been previously documented. Several studies aim to optimize diverse protocols with the objective of achieving an efficient and parallel isolation of the aforementioned three cell types from a single mouse spinal cord sample. [

2,

3,

4] A study made by the University of Texas provides a method for isolating microglia and astrocytes from brain and/or spinal cord from adult rodents. This method consists in a discontinuous percoll density gradient, an efficient way to discriminate between cell populations avoiding the usage of enzymatic digestion or complex sorting techniques. [

5] Cryopreservation has been extensively employed for the prolonged storage of various mammalian tissues. [

6] Successful cryopreservation of neuronal cells holds the potential to minimize resource wastage and facilitate the pooling of cells from diverse donors. The preservation of cells is of paramount importance in scientific research, providing a precautionary measure for potential reuse in repeated experiments. Despite its favorable attributes, cryopreservation has not been seamlessly integrated into routine cell isolation practice. This underscores the necessity for further refinement of cooling and thawing protocols to enhance the overall efficacy of the cryopreservation process. The methodology involves the introduction of a cryoprotective additive into the sample, followed by a gradual reduction in temperature until a predetermined point, culminating in immersion in liquid nitroegene for preservation. [

7] Regarding cell recovery, the post-crystallization cooling rate assumes critical importance in the freezing process, directly impacting the size and quantity of intracellular ice crystals formed during the transition to the storage temperature. Intracellular ice formation is intricately linked to cellular damage incurred during cryopreservation. To streamline and optimize the procedure, a spontaneous nucleation approach is employed, followed by a con-trolled cooling process until the point of spontaneous crystallization is reached. Subsequently, the sample undergoes further controlled cooling to attain the pre-selected LN2 plunge temperature. The evaluation of plunge temperature, optimal cooling rate, and cryoprotective agent concentration is essential to ensure proper post-preservation cell viability and their sustained capacity for cultivation.

Techniques to obtain the most effective isolation of cell cultures from fresh tissue are computationally demanding and subjects to high overheads. Our paper investigates the possibility to optimize the process of isolating nervous system cells from material of animal origin. The novelty of the planned research lies in the use of methods and reagents used commercially for storing human se-men in infertility treatment clinics. The aim of this study will be to develop a quick, simple and effective method for culturing neuronal cells obtained from frozen biological material. In this way, we will obtain a reliable experimental model that can be used in studies of the bioactivity and cytotoxicity of substances with potential therapeutic effects in neurodegenerative diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

TrypLeTM (12604013, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific), CTS™ Synth-a-Freeze™ Medium (A1371301, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific). SpermFreeze® (Vitromed Germany), Ham’s F12 (01-095-1A, Biological Industries), EMEM (01-025-1A, Biological Industries), FBS (F2442, Sigma Al-drich), DMSO, 48 and 96-well plates, Brain Phys™ Neuronal Medium (05790, Stemcell), Neuro-basal® Medium (21103049, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific), Laminin (11243217001, Roche), Col-lagen Type I from rat tail (C3867, Sigma-Aldrich), Poly-D-lysine (152035, Thermo ScientificTM), BDNF (B3795-10UG, Sigma Aldrich), B-27™ Supplement (50X), serum free (17504044, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific), Acetic acid (695092, Sigma-Aldrich), Chloroform (366927, Sigma-Aldrich), PBS without calcium and magnesium (10010023, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific), Freez-ing container, Nalgene® Mr. Frosty (C1562, Sigma-Aldrich), NucleoCounter® NC-200 (970-0200, Animalab), Via1-Cassette™ (941-0012, Fisher Scientific) ; Countstar automated cell counter (ALIT Life Science, Shanghai, China), Two Wistar Rats (entire brain and mixture of hippocampus and cortex tissues).

2.2. Rat Brain Isolation Protocol

In the course of this study, we utilized rats that were already designated for euthanasia due to breeding surplus. As such, these animals were not specifically procured for our experiment, and their use does not constitute an additional ethical concern. Their inclusion in our study did not alter or influence their predetermined fate. We have harvested tissue postmortem from four Wistar rats weighing between 240-260 g. We have performed a dorsal skin incision on the rat, extending from the base of the skull to the ears and eye sockets, followed by the removal of the skin. Subsequently, we dissected and removed the muscles and fascia from the dorsal and posterior parts of the skull. Using surgical scissors, we carefully excised the eyes. To ensure stability during the procedure, forceps were securely clamped onto the eye sockets. Beginning at the Cisterna Magna, we made incisions in the skull bones using scissors, simultaneously directing the cuts dorsally and laterally. Care was taken to apply pressure away from the brain surface to prevent tissue damage. Further incisions were made along both lateral surfaces of the skull, just above the zygomatic arch junction. Following these incisions, we gently elevated the resulting bony flap in the dorsal direction, carefully fracturing it near the eye socket junction to preserve the integrity of the frontal cortex. Subsequently, we delicately removed the brain membrane, ensuring the preservation of the underlying tissue. Finally, the brain was carefully leveraged from below using a spatula and extracted from the remaining bony structure (

Figure 1.).

2.3. Rat Tissue Isolation

Cell isolation procedures were performed on rat tissues, specifically on the whole rat brain and on the hippocampus and cortex tissues mixture. Each harvested tissue was then immersed in a PBS solution (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) containing antibiotics (Penicillin-Streptomycin; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) within a Petri dish. Under a dissecting microscope (Motic SMZ-168, Motic, Rich-mond, British Columbia, Canada), blood vessels and meningeal tissue were carefully excised. Subsequently, tissue was dissected into smaller fragments using a scalpel. For each rat, 3ml of TrypLeTM was added to the dissected tissues, followed by a 15-minute incubation period (

Figure 2).

To deactivate TrypLeTM, medium containing 10% FBS and EMEM/F12 was introduced. Subsequent centrifugation and removal of the medium resulted in 3.3ml (±0.3ml) of cell suspension. This suspension was divided into halves, each yielding 1.7ml, and further subdivided into three parts of approximately 500μl, which were subsequently centrifuged.

2.4. Freezing Protocol

The supernatant was carefully removed, and for freezing purposes, 1 ml of CTS™ Synth-a-Freeze™, 1 ml of SpermFreeze®, or 1 ml of Ham’s F12 with EMEM (1:1 ratio with 10% FBS and 10% DMSO) was added to each tissue mixture. As a negative control, tissue pellets were frozen without any additive media. Subsequently, 60 µl of each tissue mixture was added to a Via1-Cassette™ containing 0.2 µg of acridine orange and 0.2 µg of 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) deposited in each cassette during manufacture. The final concentration of acridine orange and DAPI in the mixture was approximately 3.3 mg/L. The viability of the cells was measured using the NucleoCounter® NC-All cryotubes were left for 10 minutes at -20°C in a Nalgene® Mr. Frosty containing isopropanol and then transferred to a -80°C freezer. After 24 hours, the cryotubes were moved to a dewar with dry ice and left for 30 days.

2.5. Thawing andd Cell Culture

In the thawing phase, rat tissue frozen in various cryoprotectants were subjected to proliferation and culture using different culture media, plate coatings and additional reagents. Rat cells frozen in liquid nitrogen in different cryoprotectants were thawed to initiate the subsequent steps of the experiment. The thawing process was performed by 1min incubation in 37°C water bath, then 4ml of fresh, warm media was added to the culture. Next, cells were centrifuged (1200rpm, 3min.) and washed two more time with fresh media. At the end of the procedure cell cultures were passaged to 25cm2 culture flasks and left for 24h to adhere to the bottom. The used culture media mixture for each cryoprotectant were as followed:

Neurobasal® Medium supplemented with 2% FBS

Brain PhysTM Medium complemented with 2% FBS

Ham’s F12 with EMEM in a 1:1 ratio with 10% FBS

2.6. Laminin Coating

The culture flasks were covered with laminin. First, the laminin was thawed at 2 - 8°C to avoid gel formation. Next, it was diluted in PBS without calcium and magnesium to the 0.01% concentration (2 µg/cm².). Well surface was then coated with a minimal volume of the laminin solution, ensuring coverage of the entire area. After 30 minutes at room temperature, excess solution was removed, and the coated surface was allowed to air dry for at least 45 minutes under the hoover in the sterile conditions The plates covered with laminin were sterilized by exposure to UV light in a sterile culture hood before introducing cells and medium.

2.7. Collagen Type I Coating

Collagen type I was diluted in sterile 0,2% acetic acid to obtain a 0.1 % collagen solution. It was stirred at room temperature for 3 hours until dissolved. The collagen type I solution was then diluted 10-fold to obtain a working concentration of 0.01% (5μg/cm2). Next, the collagen type I solution was transferred to a glass bottle and chloroform was carefully layered at the bottom. Approximately 10% of the volume of the collagen solution was used for chloroform. It was left undisturbed over-night in 4°C. The top layer containing the collagen solution was aseptically removed. Well surface was coated with a minimal volume of the collagen type I solution, ensuring coverage of the entire area. The collagen type I was allowed to bind overnight at 4°C. Excess fluid from the coated surface was removed, and it was left to dry overnight. Then, coated surface was sterilized by 30min exposure to UV light in a sterile tissue culture hood. Before introducing cells and medium, the coated surface was rinsed with sterile PBS.

2.8. Poli-D-Lysine Coating

PDL was dissolved in sterile water with ratio 5mg PDL in 50ml water. The culture surface was coated with a minimal volume of the PDL solution, ensuring coverage of the entire area. After 5 minutes, the solution was aspirated, and the surface was rinsed with sterile water before allowing it to dry for 2 hours in a sterile culture hood prior to cell seeding.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis involved parametric tests due to normal distribution and variance equality of the data, with results presented as mean ± standard deviation. One-way ANOVA and Fisher’s LSD post-hoc analysis were conducted to compare results. Images were captured from plate wells to assess the morphology of cells seeded. Images were sequentially taken at 14 points across the culture well, covering approximately 0.24 mm2 each, totalling 3.36 mm2, representing nearly 5% of the total well area of 70 mm2.

4. Discussion

Creating cell lines from cryopreserved tissue offers several compelling advantages in biomedical research. The immediate processing of fresh tissue for cell culture is often impractical due to the resource-intensive nature of isolating and expanding cells. Consequently, frozen tissue serves as the preferred starting material for deriving primary cell lines. By creating cell lines from frozen tissue, researchers gain access to a diverse range of biological samples. [

8] These cell lines can be established from various species, including those that are rare or exotic. Frozen tissue-derived cell lines are invaluable for studying diseases that are challenging to investigate in living organisms. A significant milestone was achieved when researchers isolated primary der-mal fibroblasts from frozen bat wing biopsies. [

9] This breakthrough facilitated cellular, physio-logical, and genetic studies in bats, which are renowned for their unique traits and adaptations. However, it’s essential to recognize that cells within frozen tissue often suffer damage, leading to reduced integrity and viability. [

10,

11] The process of cryopreservation involves freezing and storing biological material at extremely low temperatures. To prevent cell damage, it requires meticulous handling during steps such as tissue and cell isolation, cryoprotection, cooling, freezing, storage, transport, thawing, and recovery. Ensuring the quality and authenticity of cell lines derived from frozen tissue is challenging. Issues like contamination, misidentification, and genetic drift can compromise the reliability of these cell lines. Creating cell lines from frozen tissue requires specialized equipment and trained personnel. Despite these challenges, this approach remains a valuable tool in new drugs research, offering the potential to advance our understanding of disease processes and develop innovative treatments. Primary cancer cell lines, derived directly from resected tissue samples (such as core biopsies, fine-needle aspirates, pleural effusions, resections, or autopsy specimens), have been successfully established. Notably, stable outgrowing cell lines were achieved in 63% of freshly prepared material and 59% of vitally frozen material prior to preparation. In the realm of brain cancer research, a study focused on glioblastoma multiforme demonstrated the successful establishment and characterization of primary cell lines from both fresh and frozen material. Remarkably, the take rates after cryopreservation were comparable to those from fresh tissue. [

12,

13] Cryopreservation poses significant challenges, including the formation of intracellular ice crystals that can alter cell structure and function. Cryoprotectants lower the freezing point of the solution, minimizing ice formation within cells. This protective mechanism prevents structural damage. Additionally, fluctuations in solute concentration during freezing and thawing induce osmotic stress, leading to cell shrinkage or swelling. Cryoprotectants help maintain osmotic balance, safeguarding cell membranes and structures. Studies reveal that freezing sperm in seminal plasma, rich in natural cryoprotectants, enhances post-thaw DNA integrity compared to other preservation methods. [

14] Furthermore, some cryoprotectants incorporate antioxidants, mitigating damage caused by reactive oxygen species and cold shock. This positively impacts post-thaw semen quality. However, it’s crucial to acknowledge that cryopreservation still induces detrimental changes in cell functions. To optimize outcomes, cryoprotectants should be used alongside meticulously optimized protocols for freezing and thawing. [

15]

In our recent study, we have explored a novel approach to cryopreservation of neuronal cells. We started with freshly isolated hippocampus and cerebral cortex tissue from rats, along with whole brain tissue. This tissue was then digested and processed to obtain a cellular suspension. The suspension was frozen using different cryoprotectants: CTS™ Synth-a-Freeze™, SpermFreeze®, and a medium with 10% DMSO. CTS™ Synth-a-Freeze™ is a commercially available product typically used for freezing cellular cultures, while a 10% DMSO addition to the medium is a standard method for cryopreserving cells to prevent damage. The novelty of our approach lies in the use of SpermFreeze®, a product normally used for freezing sperm in in vitro clinics. We hypothesized that SpermFreeze® might also improve the viability and enhance the quality of the frozen neuronal cells. This idea stems from the fact that both sperm cells and neuronal cells are very delicate and energetically demanding, making the freezing process potentially damaging for these cells. Our aim was to investigate whether using a cryoprotectant designed for sperm could improve the post-thawing effectiveness of our nervous system cells. There could be several reasons why all cells were dead after thawing despite the use of different cryo-protectants and media. Cryoprotectants can be toxic to cells at high concentrations. [

16] Even when cells are kept on ice in cryoprotectant solution, cytotoxicity caused by exposure to the cryoprotectants can occur and affect cell viability after thawing. The rates at which cells are frozen and thawed can significantly influence cell survival during low-temperature storage. If the rates are too fast or too slow, it can lead to cell death. During the freezing and thawing process, cells can experience osmotic stress due to changes in the concentration of solutes. This can lead to cell shrinkage or swelling, which can damage the cell membrane and other structures. [

17] The cell growth phase before freezing can also influence post-thaw cell recovery. Cells in the logarithmic growth phase are generally more resistant to freezing and thawing than cells in the stationary phase. Preventing osmotic shock during thawing is crucial for cell survival. Rapid changes in osmolality during the thawing process can cause cell death. The density at which cells are seeded after thawing can also affect cell survival. If the density is too low, the cells may not receive enough signals from their neighbors for survival and growth. [

18]

This research could have several potential applications, particularly in the field of neuroscience and regenerative medicine. The development of a reliable experimental model for studying the bioactivity and cytotoxicity of substances could be instrumental in researching potential therapeutic effects for neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s. The ability to culture neuronal cells from frozen biological material could provide a consistent and reliable source of cells for drug testing. This could accelerate the process of drug discovery and reduce the reliance on animal testing. If the post-thawing effectiveness of nervous system cells can be improved, it could potentially enhance the success of cell transplantation therapies. This could be particularly beneficial in treating conditions that involve damage to the nervous system, such as spinal cord injuries or stroke. While the focus of this study is on neuronal cells, the findings could potentially be applied to other cell types such as eggs or embryos, in reproductive medicine. Research in this aspect should be continued to develop optimal procedures..

Figure 1.

Whole brain isolated from the Wistar rat.

Figure 1.

Whole brain isolated from the Wistar rat.

Figure 2.

The hippocampus and cortex tissues mixture before adding the digestive enzyme.

Figure 2.

The hippocampus and cortex tissues mixture before adding the digestive enzyme.

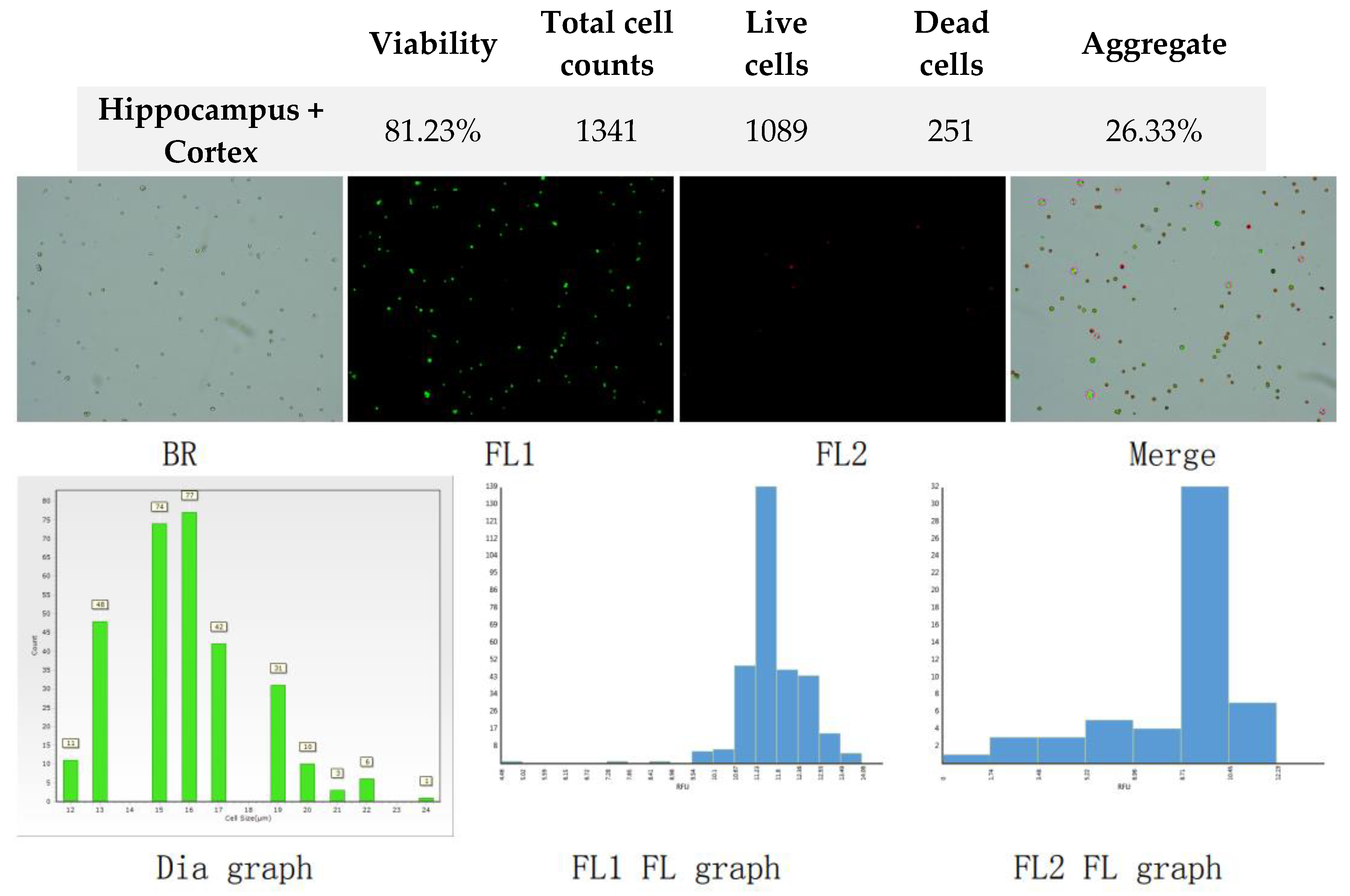

Figure 3.

Analysis of dual-fluoresce counting assay results of 25µl sample from hippocampus and cerebral cortex cellular suspension before freezing. FL1 - acridine orange green fluorescence. FL2 - propidium iodide red fluorescence.

Figure 3.

Analysis of dual-fluoresce counting assay results of 25µl sample from hippocampus and cerebral cortex cellular suspension before freezing. FL1 - acridine orange green fluorescence. FL2 - propidium iodide red fluorescence.

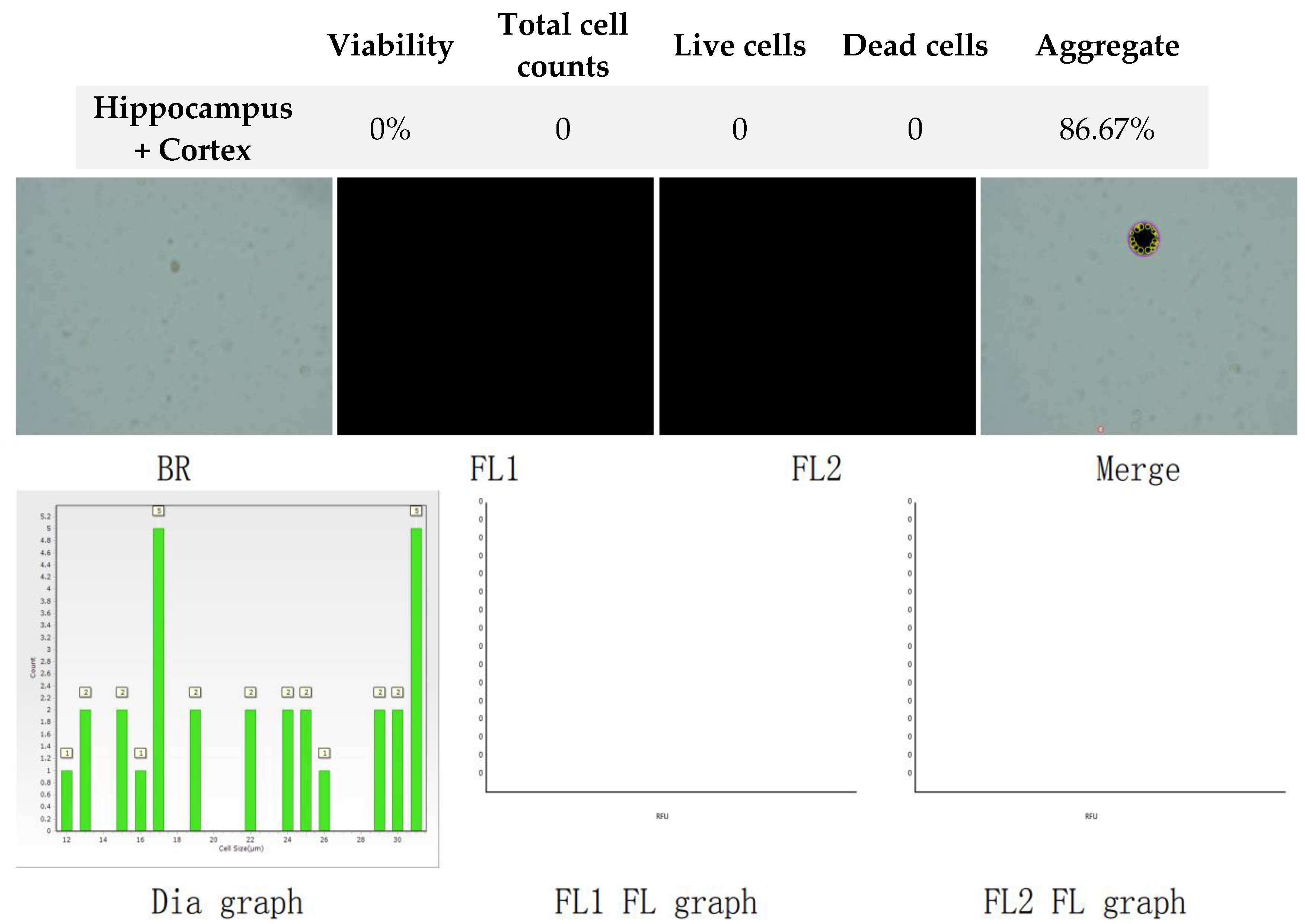

Figure 4.

Analysis of dual-fluoresce counting assay results of 25µl sample from hippocampus and cerebral cortex cellular suspension after freezing in CTS™ Synth-a-Freeze™. FL1 - acridine orange green fluorescence. FL2 - propidium iodide red fluorescence.

Figure 4.

Analysis of dual-fluoresce counting assay results of 25µl sample from hippocampus and cerebral cortex cellular suspension after freezing in CTS™ Synth-a-Freeze™. FL1 - acridine orange green fluorescence. FL2 - propidium iodide red fluorescence.

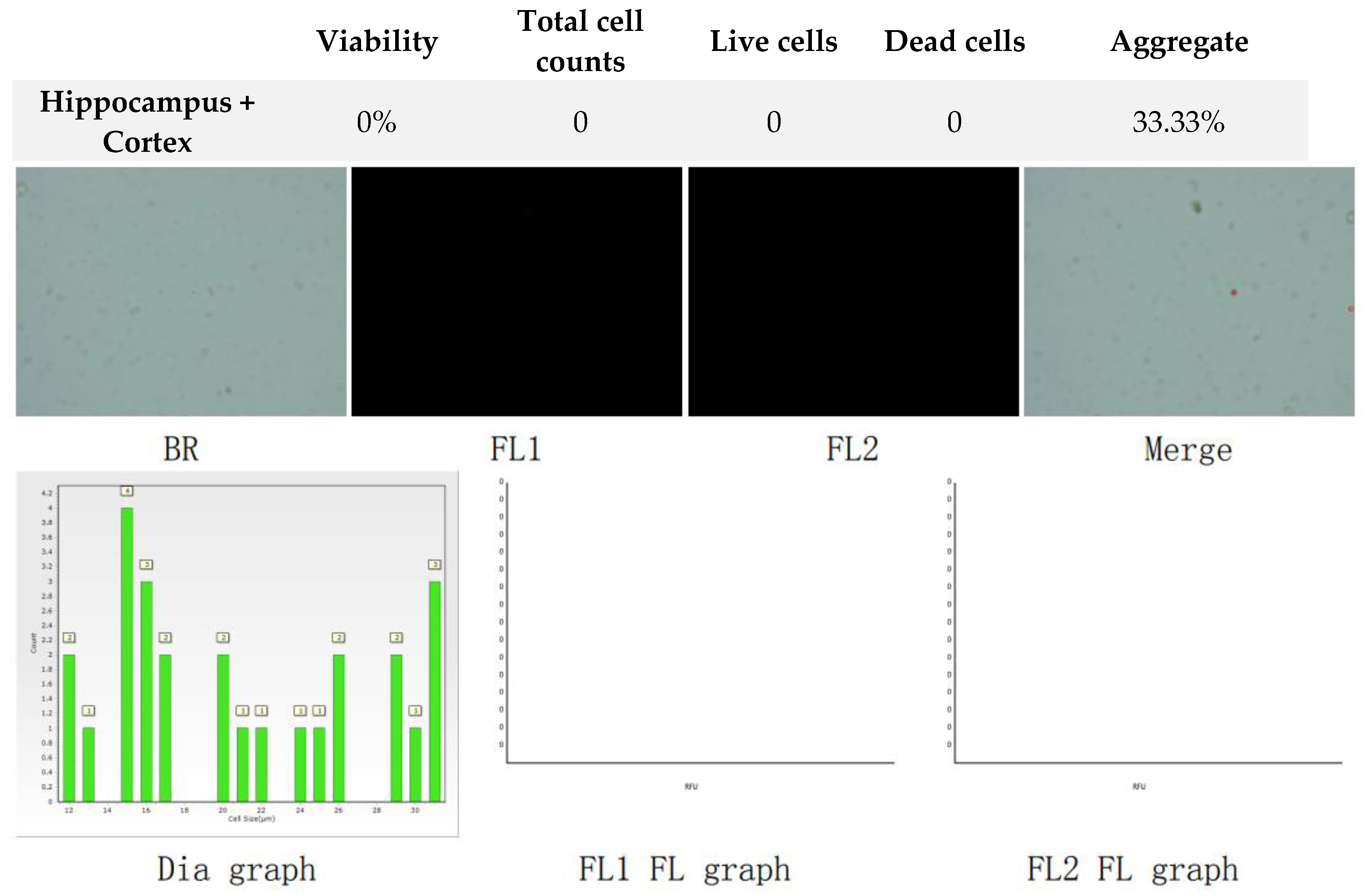

Figure 5.

Analysis of dual-fluoresce counting assay results of 25µl sample from hippocampus and cerebral cortex cellular suspension after freezing in SpermFreeze®. FL1 - acridine orange green fluorescence. FL2 - propidium iodide red fluorescence.

Figure 5.

Analysis of dual-fluoresce counting assay results of 25µl sample from hippocampus and cerebral cortex cellular suspension after freezing in SpermFreeze®. FL1 - acridine orange green fluorescence. FL2 - propidium iodide red fluorescence.

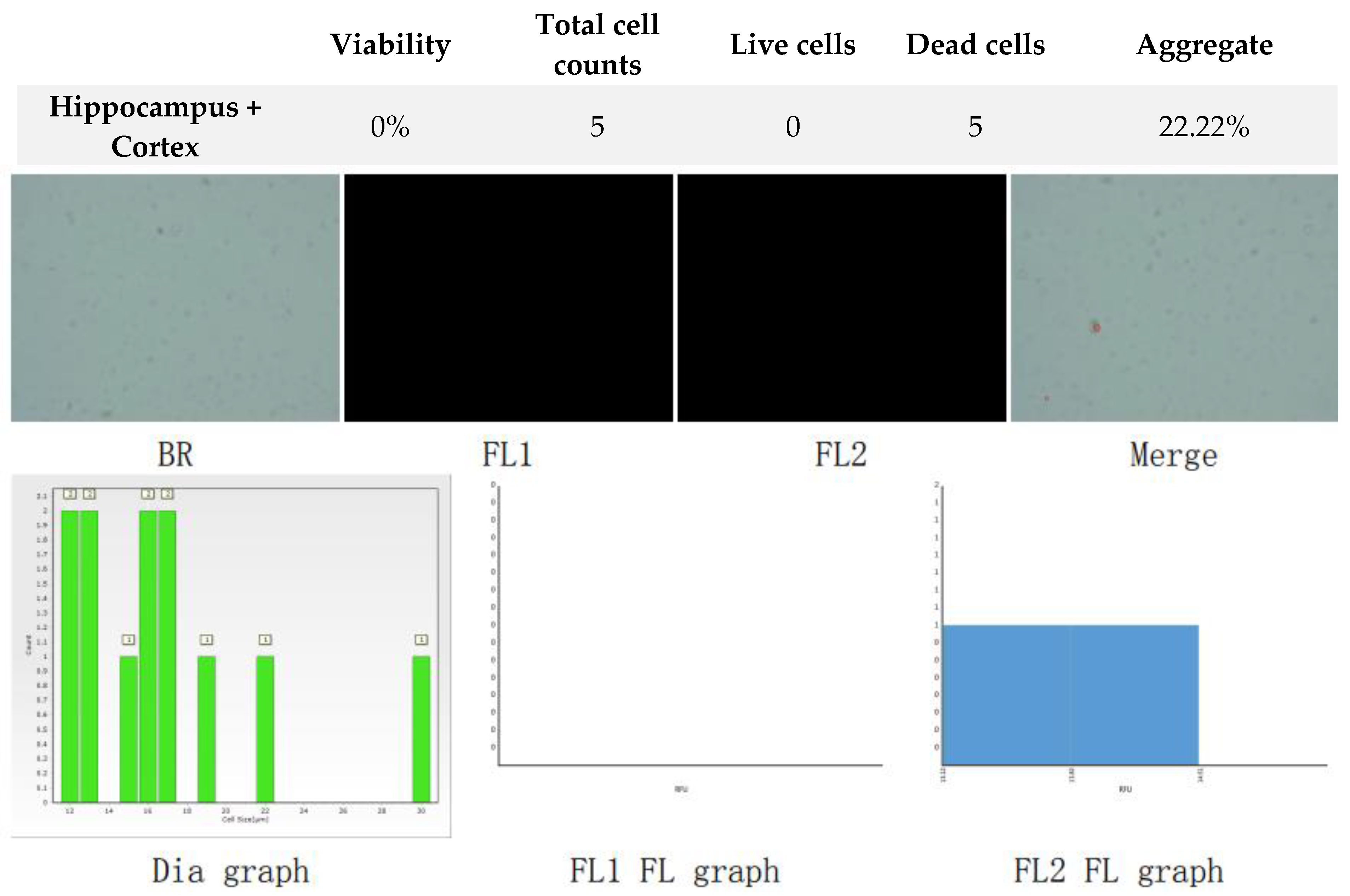

Figure 6.

Analysis of dual-fluoresce counting assay results of 25µl sample from hippocampus and cerebral cortex cellular suspension after freezing in Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS + 10% DMSO. FL1 - acridine orange green fluorescence. FL2 - propidium iodide red fluorescence.

Figure 6.

Analysis of dual-fluoresce counting assay results of 25µl sample from hippocampus and cerebral cortex cellular suspension after freezing in Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS + 10% DMSO. FL1 - acridine orange green fluorescence. FL2 - propidium iodide red fluorescence.

Figure 7.

Analysis of dual-fluoresce counting assay results of 25µl sample from whole brain suspension before freezing. FL1 - acridine orange green fluorescence. FL2 - propidium iodide red fluorescence.

Figure 7.

Analysis of dual-fluoresce counting assay results of 25µl sample from whole brain suspension before freezing. FL1 - acridine orange green fluorescence. FL2 - propidium iodide red fluorescence.

Figure 8.

Analysis of dual-fluoresce counting assay results of 25µl sample from whole brain cellular suspension after freezing in CTS™ Synth-a-Freeze™. FL1 - acridine orange green fluorescence. FL2 - propidium iodide red fluorescence.

Figure 8.

Analysis of dual-fluoresce counting assay results of 25µl sample from whole brain cellular suspension after freezing in CTS™ Synth-a-Freeze™. FL1 - acridine orange green fluorescence. FL2 - propidium iodide red fluorescence.

Figure 9.

Analysis of dual-fluoresce counting assay results of 25µl sample from whole brain cellular suspension after freezing in SpermFreeze®. FL1 - acridine orange green fluorescence. FL2 - propidium iodide red fluorescence.

Figure 9.

Analysis of dual-fluoresce counting assay results of 25µl sample from whole brain cellular suspension after freezing in SpermFreeze®. FL1 - acridine orange green fluorescence. FL2 - propidium iodide red fluorescence.

Figure 10.

Analysis of dual-fluoresce counting assay results of 25µl sample from whole brain cellular suspension after freezing in Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS + 10% DMSO. FL1 - acridine orange green fluorescence. FL2 - propidium iodide red fluorescence.

Figure 10.

Analysis of dual-fluoresce counting assay results of 25µl sample from whole brain cellular suspension after freezing in Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS + 10% DMSO. FL1 - acridine orange green fluorescence. FL2 - propidium iodide red fluorescence.

Figure 11.

Cell suspension obtained from hippocampus and cerebral cortex frozen in CTS™ Synth-a-Freeze™. After thawing cell suspension was plated on laminin, collagen type I and poli-D-lysine scaffold and cultured in different medium. Examples of micrographs after 7 days incubation. A) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; B) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; C) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; D) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; E) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; F) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; G) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; H) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; I) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, PDL scaffold.

Figure 11.

Cell suspension obtained from hippocampus and cerebral cortex frozen in CTS™ Synth-a-Freeze™. After thawing cell suspension was plated on laminin, collagen type I and poli-D-lysine scaffold and cultured in different medium. Examples of micrographs after 7 days incubation. A) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; B) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; C) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; D) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; E) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; F) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; G) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; H) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; I) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, PDL scaffold.

Figure 12.

Cell suspension obtained from hippocampus and cerebral cortex frozen in SpermFreeze®. After thawing cell suspension was plated on laminin, collagen type I and poli-D-lysine scaffold and cultured in different medium. Examples of micrographs after 7 days incubation. A) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; B) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; C) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; D) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; E) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; F) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; G) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; H) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; I) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, PDL scaffold.

Figure 12.

Cell suspension obtained from hippocampus and cerebral cortex frozen in SpermFreeze®. After thawing cell suspension was plated on laminin, collagen type I and poli-D-lysine scaffold and cultured in different medium. Examples of micrographs after 7 days incubation. A) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; B) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; C) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; D) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; E) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; F) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; G) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; H) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; I) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, PDL scaffold.

Figure 13.

Cell suspension obtained from hippocampus and cerebral cortex frozen in Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS + 10% DMSO. After thawing cell suspension was plated on laminin, collagen type I and poli-D-lysine scaffold and cultured in different medium. Examples of micrographs after 7 days incubation. A) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; B) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; C) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; D) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; E) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; F) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; G) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; H) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; I) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, PDL scaffold.

Figure 13.

Cell suspension obtained from hippocampus and cerebral cortex frozen in Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS + 10% DMSO. After thawing cell suspension was plated on laminin, collagen type I and poli-D-lysine scaffold and cultured in different medium. Examples of micrographs after 7 days incubation. A) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; B) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; C) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; D) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; E) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; F) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; G) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; H) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; I) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, PDL scaffold.

Figure 14.

Cell suspension obtained from whole brain frozen in CTS™ Synth-a-Freeze™. After thawing cell suspension was plated on laminin, collagen type I and poli-D-lysine scaffold and cultured in different medium. Examples of micrographs after 7 days incubation. A) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; B) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; C) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; D) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; E) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; F) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; G) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; H) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; I) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, PDL scaffold.

Figure 14.

Cell suspension obtained from whole brain frozen in CTS™ Synth-a-Freeze™. After thawing cell suspension was plated on laminin, collagen type I and poli-D-lysine scaffold and cultured in different medium. Examples of micrographs after 7 days incubation. A) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; B) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; C) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; D) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; E) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; F) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; G) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; H) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; I) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, PDL scaffold.

Figure 15.

Cell suspension obtained from whole brain frozen in SpermFreeze®. After thawing cell suspension was plated on laminin, collagen type I and poli-D-lysine scaffold and cultured in different medium. Examples of micrographs after 7 days incubation. A) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; B) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; C) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; D) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; E) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; F) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; G) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; H) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; I) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, PDL scaffold.

Figure 15.

Cell suspension obtained from whole brain frozen in SpermFreeze®. After thawing cell suspension was plated on laminin, collagen type I and poli-D-lysine scaffold and cultured in different medium. Examples of micrographs after 7 days incubation. A) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; B) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; C) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; D) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; E) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; F) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; G) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; H) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; I) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, PDL scaffold.

Figure 16.

Cell suspension obtained from whole brain frozen in Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS + 10% DMSO. After thawing cell suspension was plated on laminin, collagen type I and poli-D-lysine scaffold and cultured in different medium. Examples of micrographs after 7 days incubation. A) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; B) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; C) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; D) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; E) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; F) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; G) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; H) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; I) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, PDL scaffold.

Figure 16.

Cell suspension obtained from whole brain frozen in Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS + 10% DMSO. After thawing cell suspension was plated on laminin, collagen type I and poli-D-lysine scaffold and cultured in different medium. Examples of micrographs after 7 days incubation. A) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; B) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; C) Neurobasal® + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; D) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; E) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; F) BrainPhys™ + 2% FBS medium, PDL scaffold; G) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, laminin scaffold; H) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, collagen type I scaffold; I) Ham’s F12:EMEM (1:1) + 10% FBS medium, PDL scaffold.