Introduction

Due to its complexity, heterogeneity, and ability to migrate and invade distant sites, cancer remains one of the major challenges in medicine today. The current conventional treatments of tumors include chemotherapy (CT), surgery, and radiotherapy (RT), and despite the reported success, they are accompanied by inevitable side effects. These treatments do not always achieve the desired outcome of preventing tumor recurrence and metastasis, and, in some cases, may exhibit prometastatic effects [

1,

2]. Furthermore, cancer cells are capable of metabolic changes that lead to resistance to RT and CT [

3]. As a result, cancer remains the second leading cause of death worldwide.

Nanotechnology offers a promising way to address the aforementioned challenges in cancer therapy. At the nanoscale, particles transform their characteristics, which can facilitate interactions with cell surfaces and intercellular structures [

4]. Nanoparticles (NPs) can be engineered as therapeutic agents with versatile properties: enhancing biodistribution, preventing the encapsulated cargo from degradation, incorporating targeting ligands, and overcoming drug resistance [

5]. The appropriate design also attributes to theranostic potential of NPs and enables multimodal therapy. Such integration of therapies results in synergistic action, leading to improved patient outcomes.

An example of a candidate for synergistic therapies is hyperthermia, as it has demonstrated a potential to enhance the effects of RT and CT [

6]. Hyperthermia also triggers the release of heat shock proteins, activating immune cells [

7] and further improving the therapeutic outcome. Furthermore, elevated temperature itself serves as an effective therapy by inducing protein denaturation, causing indirect DNA damage [

8]. Hyperthermia also induces reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in tumor cells, cell cycle arrest, cytoskeletal alterations and damages of collagen fibers, changes in the expression of tumor cell genes, and microvessel damage [

9]. Owing to rapid angiogenesis, the blood vessels in tumor tissue exhibit abnormal morphological growth, compromised functionality, and challenges in dissipating accumulated heat. As a result, tumor tissues exhibit higher sensitivity to hyperthermia compared to healthy tissues. Researches have demonstrated that exposition of cancer cells at 43°C for 30–60 minutes can result into effective destruction, with this duration shortened with an increase in the temperature.

The integration of nanotechnology into the field of hyperthermia has led to the development of innovative approaches such as magnetic hyperthermia (MH) and photothermia (PTT). PTT relies on absorption of electromagnetic waves by photothermal agents and their conversion into heat. Utilizing NPs with high conversion efficiency generates nanoscale hotspots, elevating temperature and focusing the effect of hyperthermia on the tissue where they are accumulate. Among photothermal agents, gold NPs stand as the gold standard for PTT because of their high light-to-heat conversion efficiency. Gold-shelled silica core NPs known as AuroShell® have reached clinical trials for the treatment of metastatic lung cancer (NCT01679470), head and neck cancer (NCT00848042), and prostate cancer [

10] (NCT02680535 and NCT04240639). PTT using gold-silica NPs is also being investigated for the treatment of atherosclerosis (NCT01270139) and acne (NCT02219074). Iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) are also desirable photothermal agents due to their unique properties and excellent biocompatibility. They have already been approved for treating anaemia, as a MRI contrast agent, and as a mediator for MH. Studies have shown that IONP posess good light-to-heat conversion ability. An additional advantage is that the manipulation of IONP using external magnetic field could facilitate targeted accumulation in particular tissues, contributes for their theranostic potential, and offers an opportunity for multimodal therapies.

The aim of the present review is to summarise the recent findings on the biomedical applications of IONPs and outline the challenges and future perspectives in the field.

Iron Oxide in Medicine

Iron oxides and oxyhydroxides exist in various forms, as magnetite (Fe

3O

4) and maghemite (γFe

2O

3) are the most frequently investigated for biomedical applications. Medical uses of IONP include anaemia treatment, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), cell separation, MH, and drug delivery. The inherent superparamagnetism of IONPs enables manipulation using external magnetic field. IONPs display excelent biodegradability, as their iron content can be assimilated by the body for future physiological needs. An interesting characteristic is their "nanozyme" activity, as they possess intrinsic peroxidase-like behavior [

11]. These properties allow IONPs to serve as a versatile platform, capable of addressing diverse medical needs. For example, ferumoxytol , an IONPs formulation, is approved for anaemia treatment and also as an MRI contrast agent with T1, T2, and T2* shortening capabilities. Beyond these, ferumoxytol demonstrates a great potential in numerous other medical applications [

12], including drug delivery, oral biofilm treatment, anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory therapies. In the presence of hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2), ferumoxytol generates ROS, which have the potential to trigger ferroptosis – a type of iron-dependent cell death, explored by some researchers as a cancer therapy [

13].

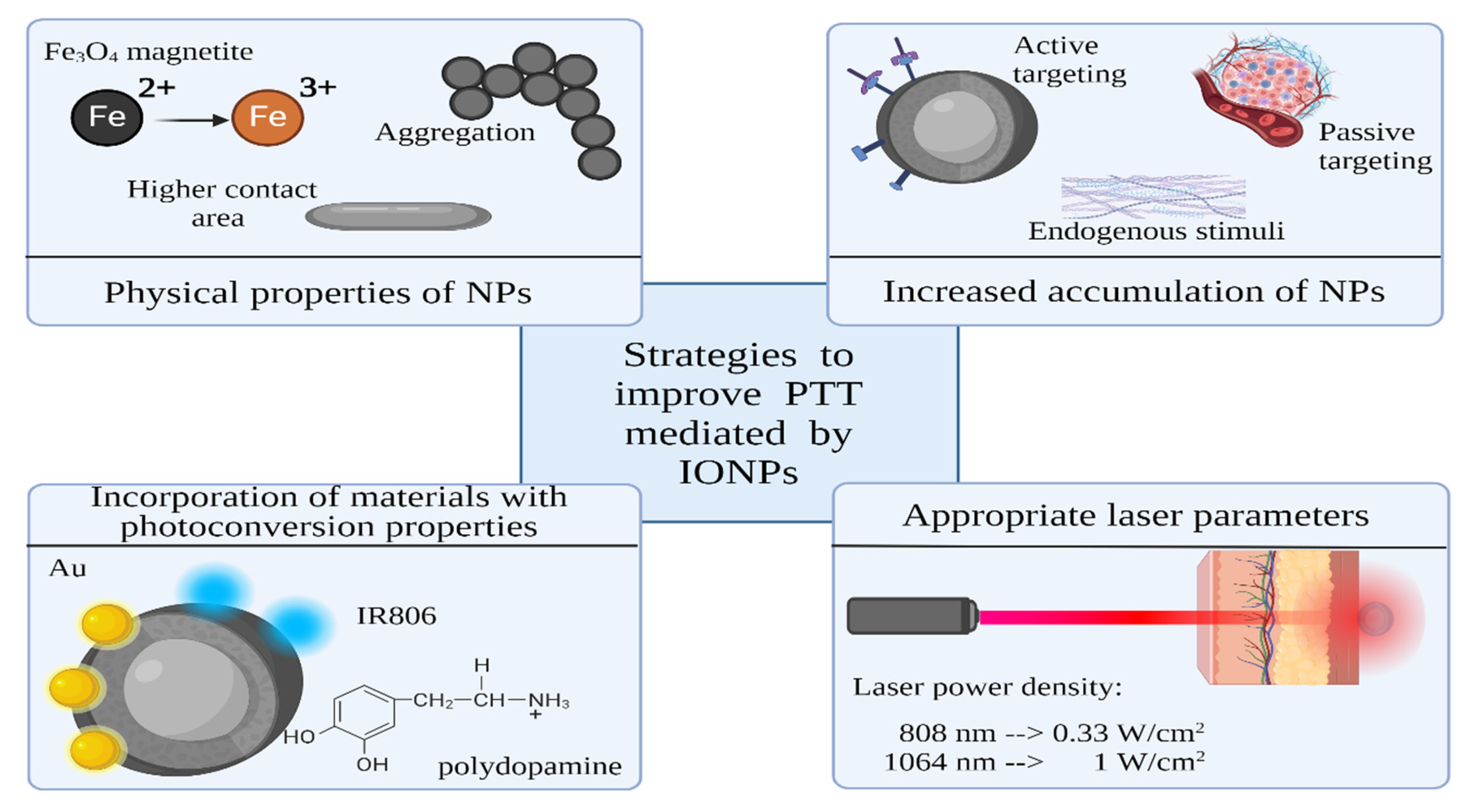

Strategies to Improve Photothermal Ability of IONPs

There are various strategies available to boost the photothermal performance of IONPs. One approach involves bandgap engineering achieved by doping, which has the potential to significantly amplify photothermal efficiency. Another method is functionalization with elements which exhibit diverse conversion mechanisms, such as metals or carbon NPs. Furthermore, a commonly employed strategy uses polymer shell with photothermal ability onto IONPs. The NPs shell can also be functionalized with photothermal organic dyes.

Incorporating additional elements in semiconductors through doping creates additional energy levels within the band gap, affecting their absorption and emission properties [

53]. During bandgap engineering, the emergence of trap-level states that function as centres for charge recombination is possible, which extends the absorption spectrum to longer wavelengths. Another change may be shift in the position of the valence or conduction band. These changes have the potential to enhance photoconversion efficiency. In a recent study [

54] was found that Zn

0.4Fe

2.6O

4 exhibited a 22% reduction in energy gap, with a value of 1.03 eV, compared to Fe

3O

4@ γ-Fe

2O

3, with a value of 1.32 eV, making it a more efficient photothermal agent.

Incorporating materials with distinct conversion mechanisms, such as plasmonic or carbon NPs, presents a promising method to enhance PTT. In their study, Pasciak et al. [

55] observed enhancement in PTT efficacy when Fe

2O

3 nanoflowers are decorated with gold NPs. The specific absorption rate (SAR) values showed a 1.8-fold increase (4581 W/g) compared to the application of γ-Fe

2O

3 nanoflowers alone (2940 W/g). The plasmonic effect in gold NPs is suggested as an enhancer of heat generation. In another work, Lu et al. [

56] demonstrated the efficacy of combining gold nanoflowers with ultrasmall IONPs. They reported a significantly improved photothermal conversion efficiency of 82.7% achieved by this composite. Wang et al. [

57] developed photothermal-immunotherapeutic NPs by hybridizing Fe

3O

4 with reduced graphene oxide. The resultant NPs achieved a tumor surface temperature of 59°C, outperforming the IONPs alone, which increased tumor surface temperature to 47°C.

The utilization of polymer coatings with inherent photoconversion properties benefits PTT [

58]. For example, polypyrrole [

59] and polydopamine are biocompatible polymers with good absorption in the NIR region. In their work, Wu et al. [

60] fabricated a superparamagnetic IONPs (SPIONs) cluster@PDA as a magnetic field–guided cancer theranostic agent. This composite exhibited enhanced photothermal capabilities when compared to SPIONs clusters without PDA coating. This improvement can be attributed to the synergistic photothermal conversion capability of the iron oxide and the PDA in combination. Furthermore, the application of an external magnetic field resulted in heightened cellular uptake, further increasing the efficacy of photothermal therapy.

One of the most used techniques for improved PTT utilizes organic dyes. Such dyes with strong absorption in the optical biological windows can facilitate the efficacy of PTT and provide fluorescent imaging. For example, Wang et al. [

61] reported coupling of IR806 dye and Fe

3O

4 NPs which improved the NIR absorption of Fe

3O

4 NPs. They found a 3.5-fold increase in the photothermal conversion efficiency for Fe

3O

4-IR806 NPs compared to the Fe

3O

4 NPs.

Increasing the efficiency of PTT can also be achieved by manipulating cellular physiology. In their review, Cao et al. [

62] describes innovative strategies to enhance PTT at mild temperature through the regulation of heat shock proteins expression, autophagy, and free radical generation.

IONPs in Theranostics

Theranostics provide the opportunity for both imaging and therapy through precisely engineered nano agents. In the context of IONPs, their magnetic properties find applications as contrast agents in MRI. In addition to enhanced conversion efficiency, the functionalization of NPs can also be used as a diagnostic modality. Organic dyes and carbon NPs find utility in fluorescent analysis, while metallic elements can act as contrast agents for computed tomography, photoacoustic tomography (PA), and surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS). The integration of multiple imaging techniques holds the potential to significantly enhance diagnostic outcomes, compensating the limitations inherent in each technique.

Iron Oxide as a PTT and MRI Agent

MRI is one of the main in vivo imaging modalities, with several advantages such as using non-ionizing radiation, high penetration depth, anatomical and functional information, and soft-tissue contrast. Additionally, image contrast can be further enhanced using contrast agents that increase lesion differentiation from healthy tissues. IONPs, with the benefits of their superparamagnetism and biocompatibility, have already been approved as a MRI agent [

63,

64]. SPIONs, whose hydrodynamic size is greater than 50 nm, are phagocytosed by Kupffer cells in the liver, so have been used for liver imaging. For example, ferumoxides (Endorem®, Feridex®, hydrodynamic diameter of 50–100 nm) and ferucarbotran (Resovist®, Cliavist®, 60–80 nm), have short blood half-life of 10 – 12 min and are used for liver tumor and metastasis imaging. Ultrasmall SPIONs, with hydrodynamic diameter smaller than 30 nm, have a longer blood half-life than SPIONs and can target macrophages in the deep compartments. They find application in MR angiography, lymph node imaging, bone marrow imaging, and more. For example, ferumoxtran-10 (Sinerem®, Combidex®, 30 nm) and ferumoxytol (Feraheme®, 20-30 nm) have a blood half-time of hours, and are used for lymph node metastasis or atherosclerotic plaques imaging, respectively.

The size, the shape, the crystallinity, and the presence of doping material within the crystal lattice of IONPs play a crucial role in determining the type of contrast (positive or negative) and the magnitude of the magnetic moment [

65]. The abundance of magnetite, the increased size, and the shape anisotropy can benefit not only PTT efficacy but also MRI capabilities [

19]. Maghemite exhibits a saturation magnetization of around 80% of that found in magnetite [

66]. Like other types of NPs, ligand functionalization provides the ability to selectively target specific tissues or cells. Lui [

67] engineered a photothermal theranostic ultrasmall SPIONs (USPIO-PEG-sLex), with MRI imaging ability, and designed to target E-selectin overexpression. This overexpression is linked to tumor progression and metastasis of a variety of malignant tumors. The results showed a reduction of the T2* relaxation value in the tumor area and confirmed the targeting ability and photothermal conversion by USPIO-PEG-sLex NPs. Kale et al. [

47] described the design of composite Fe

3O

4@GdPB, with IONPs core and gadolinium-containing Prussian blue shell, as a theranostic agent for T1-weighted MRI and PTT of tumors. Gadolinium is a component of another category of clinical MRI contrast agents. The resultant Fe

3O

4@GdPB nanocomplex increased signal-to-noise ratios in T1-weighted tumor scans and demonstrated the potential to be directed to specific anatomical locations through the external magnetic field. The nanocomposite was found to be an effective PTT agent in an animal model of neuroblastoma.

IONPs Composites as a PTT and Fluorescence Agent

Fluorescence imaging stands as a promising imaging modality, enabling the visualization of biological structures and processes across various scales, ranging from the molecular and organellar to organ levels. This versatile tool also facilitates the precise localization of single molecules within cells with nanometric resolution [

68]. A diverse range of materials serve as fluorescent elements, including semiconductors like quantum dots, rare-earth-doped matrices such as nanophosphors, organic dyes, and various forms of carbon NPs. In the field of medicine, fluorescence imaging serves as a tool for monitoring cell migration, guiding surgical procedures, visualizing arterial plaques, detecting amyloid-β plaques in Alzheimer's disease, and more.

The integration of photothermia with fluorescence diagnostics has emerged as a prevalent strategy in the field of theranostics. This is attributed to the inherent fluorescent properties of materials like carbon NPs and organic dyes, which also possess photothermal potential. The class of heptamethine dyes, including MHI-148, IR-780, IR-783, and IR-808, has gained significant interest due to their selective accumulation in tumor tissues [

69]. Furthermore, some of these dyes can induce mitochondrial toxicity, thereby enhancing the damage caused by photothermia. Chang et al [

70] have developed a dual imaging PTT nanoplatform that combines fluorescence and MRI imaging capabilities. This platform is based on IR806 dye and IONPs functionalized with citraconic anhydride. The citraconic anhydride acts as a smart pH charge-conversion agent that enhances targeted accumulation in the tumor microenvironment. In addition to the fluorescence provided by IR806, the combination of IONPs and IR806 enhances light-to-heat conversion efficiency and reduces the required light irradiation dose compared to using IONPs or IR806 alone.

However, there are some limitations when utilizing organic dyes, including their low quantum yield and rapid susceptibility to photo-bleaching. These issues have resulted in the exploration of alternative options like quantum dots and carbon NPs. Quantum dots are semiconductor crystals ranging in size from 1 to 10 nm. They exhibited photostability, narrow emission band, and excellent molar extinction coefficient – more than 10 times larger than that of organic dyes [

71]. Combining their fluorescence emission and optical absorbance, these advantages extend the use of quantum dots as a potential NIR-responsive photothermal agent for imaging-guided PTT. Carbon NPs are also of great interest as theranostic PTT agents due to their excellent mechanical, optical, and thermal properties [

72]. Wang et al. [

73] constructed magnetic Fe

3O

4 NP cores covered by a carbon shell for dual fluorescent/MRI bioimaging and PTT agent. Within the nanocomposite, Fe

3O

4 NPs contributed to contrast enhancement for T2-weighted MRI in vivo, whereas the carbon shell generated confocal fluorescence signals.

IONPs Nanocomposites for PTT and SERS

Raman scattering is a well-known technique for molecular identification. Every molecule possesses its own unique Raman spectrum, a characteristic that may give detailed information about its structural and chemical composition. The Raman spectroscopy has a low signal-to-noise ratio but has been found that the Raman signal can be amplified by a factor of 10

6 -10

9 when the specimen is placed in contact with a plasmonic NPs (Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy, SERS). Thanks to its remarkable attributes — high sensitivity, precise signal specificity, and resistance against photobleaching — SERS has been widely investigated in the field of disease diagnosis. Furthermore, a combination of MRI and SERS can achieve high sensitivity and can provide detailed biological information [

74]. The MRI resolution is at the millimeter level, which cannot reach the cellular level. On the other hand, SERS is ultra-sensitivity, so MR/SERS dual-mode imaging techniques can take full advantage of both techniques to improve diagnostic accuracy. In their study, Huang et al. [

75] synthesized photothermal NPs with the ability for real-time monitoring of drug release. This nanocomposite provided various functionalities: cancer cell targeting, pH-triggered drug release, SERS-traceable detection, MR imaging, and CT-PTT for cancer treatment. The nanosystem's architecture involves the deposition of Fe

3O

4@Au@Ag NPs onto graphene oxide (GO), coupled with the labelling of a Raman reporter, 4-mercaptophenylboronic acid (4-MPBA). Furthermore, DOX was loaded using a pH-responsive linker, a boronic ester. Within the acidic tumor microenvironment, the pH-sensitive borate ester bond broke, resulting in the release of DOX and real-time changes in the 4-MPBA SERS spectra. Additionally, the strong T2 magnetic resonance signal and NIR photothermal efficiency of the nanocomposites make it suitable for MRI and PTT. In another study, Wang et al. [

76] used Cu

2O for SERS sensitivity in multifunctional Fe

3O

4@Cu

2O theranostics agent for dual MRI-SERS imaging-guided PTT.

IONPs Nanocomposites for PTT and Computed Tomography Imaging

Computed tomography imaging, one of the most widely used imaging tools for tumor diagnoses, is based on differential tissue X-ray attenuation. The larger Z value of iron and its density can ensure contrast ability of IONPs. Moreover, the potential for enhancing the contrast can be increased through NPs functionalization with other metals like gold. Li et al. [

77] reported HA-targeted Fe

3O

4@Au NPs for tri-mode (MRI/ computed tomography/thermal) imaging and PTT of cancer, with targeting ability for CD44 receptor-overexpressing cancer cells. After intratumoral administration of the Fe

3O

4@Au-HA NPs, the tumor area exhibited a significant increase in brightness 10 minutes after injection. The computed tomography HU value within the tumor region was measured at 2303.3 HU, a substantial elevation compared to its pre-injection value of 157.4 HU. Wang et al. [

78] designed multifunctional theranostic polystyrene@chitosan@gold NPs – Fe

3O

4 nanocomposites, for a spectrum of imaging modalities including MR, computed tomography, and fluorescence, as well as the application of PTT. Following nanocomposite injection, the bright signal at the tumor site was seen. An increase in HU computed tomography value was found to correlate with the increased concentration of PS@CS@Au–Fe

3O

4–FA/ICG NPs.

IONPs Nanocomposites for PTT and PA Imaging

PA imaging relies on the photoacoustic effect, which occurs when absorbed optical energy is converted into acoustic energy [

79]. Acoustic waves exhibit significantly reduced scattering compared to optical waves within tissues, thus PA can generate high-resolution images. This method also suffers from a relatively limited penetration depth, usually around a few centimeters [

65]. Fu et al. [

80] designed multifunctional TiS2-based NPs for magnetic targeted dual-modal MRI/PA imaging-guided synergistic PTT-immune therapy. The nanoplatform could real-time monitor the treatment process via dual PA imaging and T2-weighted MR imaging. In a similar study, Ma et al. [

81] developed Fe

3O

4–Pd Janus NPs with dual-mode MRI/PA imaging properties for MH-PTT and chemodynamic therapy. Was found that the PA signal intensities of Fe

3O

4–Pd NPs increased linearly with an increase of Pd concentrations.

IONPs Nanocomposites for PTT and Ultrasound Imaging

Ultrasound (US) imaging is one of the most widely used diagnostic imaging modalities due to its advantages of being relatively inexpensive, portable, non-invasive, low cost, and capable for real-time imaging. Li et al. [

82] fabricated NPs by loading IONPs into poly(lactic acid) microcapsules, functionalized with graphene oxide. The resulting microcapsules enhanced the contrast of US, MRI, and PA imaging. In similar study Ke et al. [

83] reported the multifunctional bimodal US/MRI-guided PTT NPs fabricated through loading perfluorooctylbromide and SPIONs into poly(lactic acid) nanocapsules.

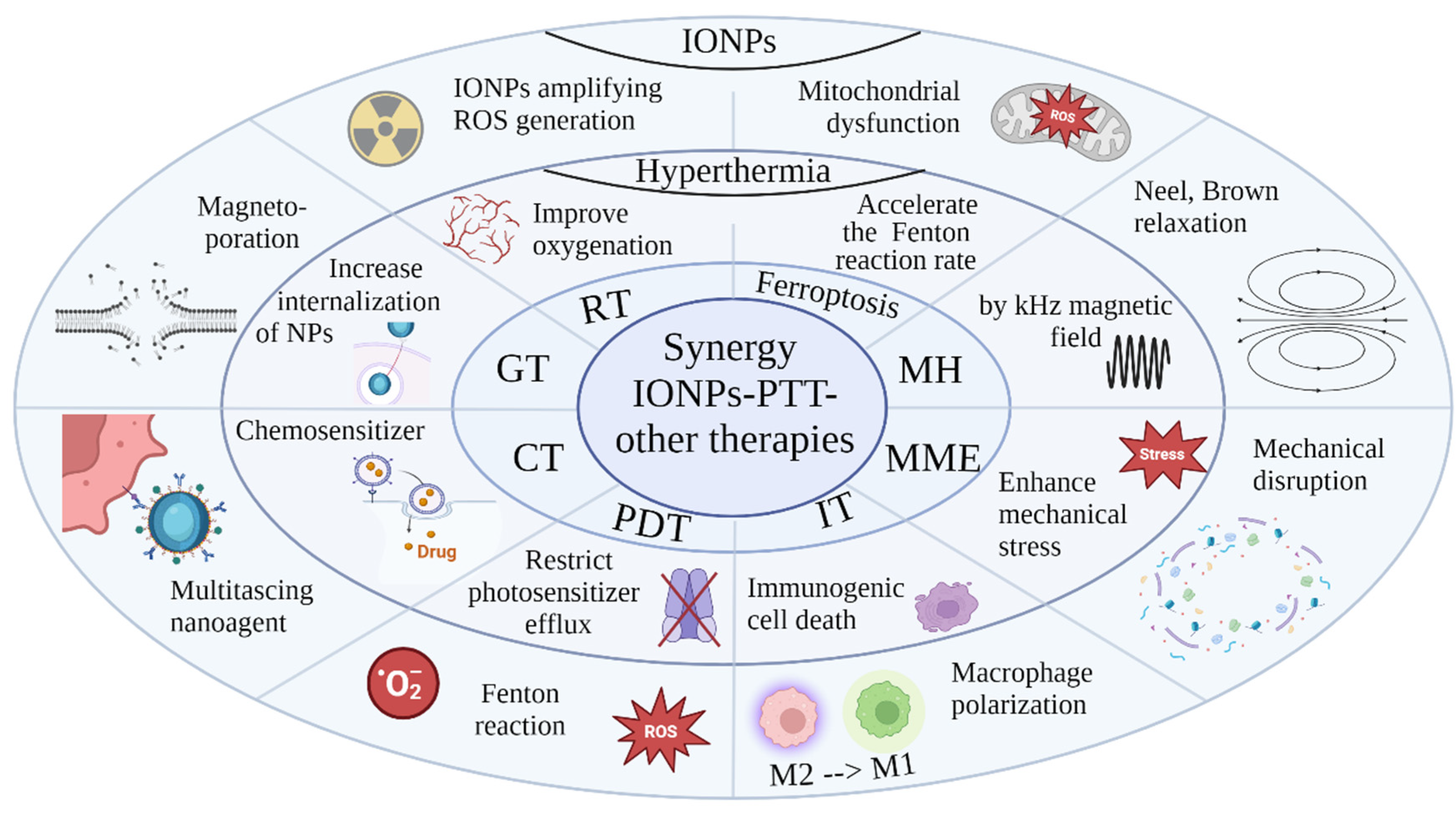

PTT in Combination with Other Treatment Modalities

The combination of PTT with other therapies can result in synergistic therapeutic effects, significantly enhancing the overall efficacy against tumors (

Figure 2). Through hyperthermia, PTT induces tumor cell death via apoptosis, necrosis, and immunogenic cell death (ICD). ICD triggers the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), stimulating innate and adaptive immune responses. With its precise and targeted approach, PTT minimizes damages to surrounding healthy tissues. Integrating PTT with other therapies allows a comprehensive cancer treatment strategy with multiple therapeutic benefits.

Synergistic CT – PTT

In numerous preclinical studies, the combination of CT and PTT has exhibited synergistic therapeutic benefits with minimal side effects. Hyperthermia acts as a chemosensitizer, improving drug distribution by enhancing membrane fluidity and increasing vascular permeability and blood flow in tumor tissues [

84]. Additionally, researches has demonstrated that hyperthermia can enhance the cytotoxicity of some CT agents. [

85]. Therefore, the integration of PTT and CT mediated by NPs presents a promising strategy for tumor theranostics.

Jin et al. [

86] used multifunctional IONPs for synergistic CT-PTT. These IONPs were coated with polydopamine, whose abundant functional groups facilitated efficient drug loading alongside its photothermal capabilities. Taking advantage of the porous structure of IONPs, this NPs formulation enabled a drug loading capacity exceeding 24.1 wt% and significantly enhanced the anti-tumor efficacy. In their study, Li et al. [

87] synthesized IONPs covalently conjugated with nanodiamonds, with good biocompatibility, photothermal stability, and photothermal conversion efficiency of 37.2%. These NPs demonstrated a high loading capacity for the CT drug DOX, reaching 193 mg/g, and exhibited magnetic navigation as well as pH and NIR responsive release characteristics. Their results revealed a synergistic inhibitory effect on tumor cells through combined CT-PTT. Kwon et al. [

88] investigated the synergistic anticancer effects of Temozolomide- and Indocyanine green-loaded Fe

3O

4 NPs by CT-PTT. Temozolomide inhibits the viability of malignant glioma cells while Indocyanine green acts as both a photothermal agent and a photodynamic photosensitizer under NIR laser irradiation. Western blot analysis and reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction demonstrated that these NPs significantly enhanced anticancer effects on U-87 MG glioblastoma cells by modulating intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis genes.

Synergistic Radiation Therapy – PTT

RT is known to elevate the production of superoxide anions within mitochondria [

89], a process that prompts superoxide dismutase to convert them into H

2O

2. The presence of IONPs further catalyzes the conversion of H

2O

2 into highly reactive hydroxyl radicals, amplifying the generation of ROS within tumor cells and enhancing the efficacy of RT. In addition, the combination of RT and hyperthermia triggers apoptosis through multiple mechanisms including oxygenation, DNA damage, and cell cycle arrest [

90]. The application of heat also enhances immunological responses against cancer by triggering the release of antigens and cytokines, and increasing the activity of immune cells.

In their study, Hu et al. [

91] investigated core-shell gold NPs with magnetic targeting ability for synergistic RT-PTT in cervical cancer. While both RT and PTT inhibited HeLa cell growth, the combined treatment, facilitated by enhanced magnetic delivery, lead to significant damage to most HeLa cells. In another study [

92], researchers reported the synthesis and utilization of three-material inorganic heterostructures composed of iron oxide-gold-copper sulfide. These trimers exhibit multifunctional properties, including optimal heating loss in MH, high adsorption in the first NIR biological window, and serving as carriers for 64Cu at internal RT. Furthermore, they are traceable by positron emission tomography, demonstrating high potential for advanced imaging and therapy.

Synergistic Photodynamic Therapy – PTT

The combination of Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) and PTT offers a promising approach for effective treatment of localized tumors [

93]. While PDT relies on oxygen-dependent photosensitizers and faces challenges with tumor hypoxia, mild hyperthermia can improve tumor oxygenation, thereby enhancing subsequent PDT efficacy. Conversely, hypoxia and tumor acidification post-PDT can sensitize cells to PTT. Hyperthermia elevates mitochondrial ROS levels and reduces expression of the ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCG2, thus boosting PDT efficacy by restricting photosensitizer efflux. Additionally, ROS generated during PDT directly impairs heat shock proteins, weakening their protective function against PTT.

In their study,

Chiu et al. [

94] investigated the therapeutic potential of the nanocomposite as a combined PDT-PTT agent. These nanoagents exhibited high catalytic activity, effectively breaking down H

2O

2 into reactive hydroxyl and hydroperoxyl radicals via Fenton-based reactions. Experiments conducted on mice with solid tumors revealed significant therapeutic effects. Coupling NPs injection with NIR illumination led to substantial tumor removal without recurrence. The histological examination further confirmed extensive tumor cell damage following NPs application and NIR laser illumination.

Yao and Zhou [

95] reported chlorin e6 (Ce6)-conjugated IONPs designed for ablation of glioblastoma cells via combining PDT-PTT. When subjected to 660 nm laser irradiation, the nanoagents produced singlet oxygen, facilitating PDT. Following incubation of C6 cancer cells with the NPs, quantitative analysis revealed that the percentages of living cells in laser- or NPs-treated groups were around 99.0%. Conversely, the NPs + laser group exhibited a cell death rate of 83.6%, with only 16.4% of cells surviving. In another study,

Zhao et al. [

96] developed mesoporous Fe

3O

4@TiO

2 microspheres for NIR-light-enhanced chemodynamic therapy, CT and PDT. Titanium dioxide was utilized as an effective PDT agent. The nanoplatform was further optimized by loading the CT drug DOX, which could be efficiently released upon NIR excitation and slight acidification. In vitro experiments demonstrated the biocompatibility of the nanoplatforms, magnetic targeting, and synergistic efficacy of multifaceted cancer treatment.

As mentioned, the efficiency of PDT is limited by the hypoxic tumor microenvironment and low tissue penetration of ultraviolet/visible light. To address these limitations,

Zhang et al. [

97] combined Fe

3O

4@MnO

2-doped upconversion NPs with black phosphorus nanosheets. The black phosphorus demonstrated strong O

2 production for PDT when irradiated at 660 nm and high photothermal conversion efficiency when irradiated at 808 nm, enabling them to serve as both PDT and PTT agents. To overcome lower tissue penetration of 660 nm laser irradiation, black phosphorus was combined with multifunctional upconversion NPs. These NPs can absorb long-wavelength photons and emit shorter-wavelength light to activate photosensitizers. This approach creates a theranostic platform capable of simultaneous PTT/PDT with single 808 nm laser irradiation, self-supporting O

2 in the tumor microenvironment, and multimodal imaging.

Synergistic Ferroptosis - PTT

Ferroptosis is a regulated form of cell death characterized by the accumulation of ROS, particularly lipid peroxides, leading to oxidative stress-induced cell death. This process is triggered by depletion of intracellular antioxidant systems, or disruption of lipid metabolism pathways. The iron-dependent nature of ferroptosis is crucial, as iron catalyzes the Fenton reaction, which generates ROS, initiating lipid peroxidation and damaging cell membranes. Combining moderate heat with IONPs could disrupt the redox balance of tumors, increasing oxidative damage and sensitizing cells to ferroptosis.

Cai et al. [

98] investigated pomegranate-like IONPs composed of SPIONs encapsulated within a reduced poly(β-amino ester)s-PEG amphiphilic copolymer. This innovative platform facilitates photothermal conversion and controlled release of iron ions and DOX, under mild hyperthermia generated by NIR irradiation. Additionally, iron overload triggers polarization of macrophages towards an M1 phenotype via the ROS/acetyl-p53 pathway, enhancing ferroptosis of tumor cells and suppressing tumor growth. M1-type tumor associated macrophages leads to increased H

2O

2 secretion, promoting peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acid-containing phospholipids, while also secreting IFNγ, known to induce lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis by inhibiting SLC7A11 expression. Through the synergistic interplay of these functions, authors observed remarkable ferroptosis and growth inhibition in mouse bladder cancer cells.

Yang et al. [

99] developed IONPs targeting folic acid and loaded with Dox. These NPs enhance ferroptosis efficiency and exhibit highly efficient PTT upon NIR-II irradiation, along with the controlled release of ferric ions and Dox. This treatment resulted in significant upregulation of cellular respiration and electron transport while downregulating epigenetic pathways, with an overall effect of cellular apoptosis. In vivo validation in 4T1-tumor-bearing Balb/c mice demonstrated that laser irradiation alone did not inhibit tumor growth. In mice treated with NPs but without light irradiation, ferroptosis significantly inhibited tumor growth, similar to basic CT. The most promising treatment outcomes were observed in the group receiving NPs loaded with Dox and combined with 1064 nm laser irradiation, nearly suppressing tumor growth by 98.6%. Notably, even without the CT drug, Fe

2O

3 treatments resulted in a high tumor inhibition ratio of 93.8% after laser irradiation. In another study, Cun et al. [

100] created a nanosystem that depleted glutathione and amplified •OH production for photo-strengthened peroxidase-like nanocatalytic tumor therapy. Pretreatment with β-Lapachone effectively elevated H

2O

2 levels, which together with NIR laser treatment demonstrated significantly enhanced anticancer activity. Notably, in vivo therapy achieved a tumor inhibition rate of 96.4%, and complete tumor ablation in two of five animals.

Synergistic MH – PTT

IONP−mediated MH is a recently proposed cancer treatment. In this strategy, magnetic NPs are applied to generate overheating via Brownian and Neelian relaxations under an alternating magnetic field AMF (100–300 kHz). A combination of MH and PTT dual thermal treatments could overcome some of the individual deficiencies to achieve a promising cancer cell-killing effect. IONPs have emerged as principal agent for MH due to their minimal toxicity in cellular systems and multimodal functionality for diagnostic, targeting, and therapeutic purposes.

In their study,

Anilkumar et al. [

101] developed liposomal nanocomposites containing citric-acid-coated IONPs for dual magneto-photothermal cancer therapy. In vitro cell culture experiments confirmed the efficient passive accumulation of these liposomes in human glioblastoma U87 cells due to their cationic nature. Treatment with dual MH-PTT -mode resulted in a significant reduction in cell viability compared to single-mode AMF or NIR laser treatments. At a maximum concentration of 4.5 mg/mL, individually, AMF and NIR lasers reduced cell viability by 32–35%, but when combined, this effect was significantly enhanced by 2.4-fold to 82%. In a similar study, Bao et al. [

102] synthesized magnetite vortex NPs coated with polypyrrole for dual-enhanced hyperthermia. The NPs showed excellent hyperthermia effects when simultaneously exposed to the AMF and NIR laser. In animal experiments, the relative tumor volume was notably lower in the group subjected to both NIR and MH, showing significant tumor suppression and nearly complete tumor reduction compared to a single mode of treatment. Lu et al. [

103] developed core-shell Fe

3O

4@Au magnetic NPs encapsulating cetuximab, a monoclonal antibody targeting the EGFR, for targeted magneto-photothermal therapy against glioma cells. In vivo, experiments demonstrated significant tumor growth suppression in the dual MH+NIR treatment compared to single modes. qRT-PCR and Western blot analyses revealed that NPs-mediated hyperthermia upregulated mRNA and protein levels of intrinsic apoptotic markers in glioma cells.

Synergistic Magneto-Mechanical Effect– PTT

The magneto-mechanical effect describes the induction of mechanical motion by particles when subjected to a magnetic field [

104]. In cancer treatment, this effect is utilized to apply controlled oscillations of particles that exert mechanical force on cancer cells to destroy tumors. This therapy offers a highly localized effect, reducing damage to surrounding healthy cells.

Lopez et al [

105] showed that SPIONs targeting lysosomes with a size of only 6 nm were able to induce death of cancer cells. Their study shows that the force generated by the NPs was around 3 pN, which is not enough to induce direct membrane disruption, but the mechanical activation of magnetic NPs induced lysosome membrane permeation, and the release of the lysosome content and cell death was mediated through a lysosomal pathway depending on cathepsin-B activity.

In their study, Muzzi et al. [

106] synthesized star-shaped Au@Fe3O4 NPs of a gold core surrounded by an anisotropic magnetite shell for magneto-mechanical stress and photothermia applications. Following the incorporation of these nanostars, cell viability was notably reduced to 65% after AMF stimulation and to 45% after exposure to light.

In a study by Wu et al. [

107], novel hollow magnetic microspheres were synthesized, composed of superparamagnetic Fe

3O

4, for multimode cancer therapy. Results demonstrated that a combination of NPs, magneto-mechanical force, photothermal, and photodynamic effects under a varying magnetic field and 808 nm laser led to the elimination of nearly all cancer cells, with approximately 99% cell death.

Synergistic Immunotherapy - PTT

Immunotherapy harnesses adaptive immunity to suppress tumor growth, but the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment limits its effectiveness. PTT addresses this limitation [

108] by directly eliminating tumors, while also enhancing tumor immunogenicity through ICD, improving tumor blood flow, promoting immune cell infiltration, and aiding in the distribution of therapeutic molecules within tumors. PTT-induced ICD releases DAMPs and TAAs, stimulating innate and adaptive immune responses. Furthermore, PTT increases radical formation, while the radicals block heat shock proteins production. These mechanisms collectively initiate an inflammatory cascade, facilitating antigen presentation, and leading to immune memory against tumor recurrence and metastasis. Tsao et al. [

109] developed dual-sensitive NPs that can combine PTT, Nitric oxide (NO) gas therapy, and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) immunotherapy. S-nitrosoglutathione-loaded gold NPs were coated with IONPs, betanin, and 1-methyl-D-tryptophan. S-nitrosoglutathione decomposed into NO gases and glutathione disulfide by heat and UV/visible light. NO has several tumoricidal effects and can react with ROS to produce highly reactive nitrogen species. The combination of PTT and NO gas therapy can effectively eliminate cancer cells, resulting in a large amount of TAAs compared to the individual treatment in vitro. These antigens enhance the maturation of dendritic cells, leading to long-term immunity.

In another study, Wang et al. [

110] fabricated a tumor microenvironment-responsive nanoplatform for the treatment of aggressive, metastatic Panc02-H7 pancreatic tumors. In this nanoplatform, IONPs were loaded with imiquimod (IMQ) as an immunoadjuvant, and ICG as a photothermal agent. The PTT induced ICD, which combined with released IMQ, triggered antitumor immunity and resulted in reduced metastasis. The nanoplatform induced maturation of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells, polarization of macrophages to the M1 phenotype, increased T cell infiltration and stimulated cytokine secretion. The results showed complete eradication of primary tumors and prolonged survival time, without damage to normal tissue and systemic autoimmunity.

Zhou et al. [

111] developed a nanoplatform, containing R837 immunoadjuvant, ovalbumin as a strong immunogenic antigen, and manganese iron oxide for synergetic PTT-immunotherapy. Under 805 nm laser irradiation, the nanoplatform produced dendritic cells maturation and systemic T-cell activation. The synergistic effect between ovalbumin and R837 stimulates an immune response when combined with released tumor antigens induced by PTT. This multitasking NPs significantly inhibited tumor growth and lung metastases. The mice treated with NPs plus laser irradiation had a survival rate of 33.3% 100 days after treatment, whereas no mice survived a single treatments.

Synergistic Gene Therapy - PTT

Gene therapy is an innovative approach in cancer treatment, effectively controlling tumor growth by regulating key genes or proteins [

112]. However, the direct administration of gene drugs without a delivery vehicle is susceptible to degradation by nucleases. Moreover, the lack of tumor-targeting ability of naked genes may result in unintended effects on healthy cells and tissues. The challenges posed by the molecular weight, negative charges, and hydrophilicity of naked genes further hinder their penetration into cancer cells. Therefore, the selection of an appropriate gene delivery system is crucial for the success of cancer therapy [

113]. IONPs offer the potential for efficient delivery to tumors due to their biocompatibility, magnetic responsiveness, and surface modification capabilities. IONPs, when surface-modified, can effectively load negatively charged genetic drugs through electrostatic adsorption, and have the potential to enhance the tumor treatment by combining gene therapy with phototherapy. Laser irradiation can improve gene delivery across membranes, a novel approach known as photoporation [

114], via short pulses that facilitate the entry of NPs loaded with siRNA into cells. Temperature elevation caused by the conversion of light into thermal energy triggers the formation of small water vapor bubbles, which expand, collapse, and generate high-pressure shockwaves. These shockwaves create pores in nearby cell membranes, allowing the NPs to enter the cells through diffusion.

Huang et al. [

115] applied the combination of porous IONPs mediated PTT and gene therapy to destroy lung cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Long noncoding RNA CRYBG3, induced by heavy ion irradiation in lung cancer cells, has been shown to depolymerize the actin cytoskeleton, induce cell death, inhibit tumor progression, and decrease invasiveness. Combining PTT with CRYBG3-mediated gene therapy resulted in synergistic cancer cell-killing efficacy, outperforming either therapy alone.

Conclusions

IONPs possess a range of characteristics that make them valuable for diverse medical applications. Their magnetic properties allow them to serve as MRI contrast agents, mediators for MH, and delivery vehicles through magnetoporation and magnetic navigation. Additionally, they exhibit responsiveness to various physical fields. Upon exposure to laser irradiation, IONPs efficiently convert light into heat, inducing localized hyperthermia. Their catalytic nature enhances ROS production, leading to oxidative stress and ferroptosis. Moreover, the ICD triggered by treatments such as ferroptosis and heat can provoke an immune response against cancer cells, showing promise in overcoming metastatic tumors. Combining IONPs with heat enhances various cancer therapies including RT, PDT, CT, est. The multitasking capabilities of IONPs position them as useful mediators in numerous medical applications, offering versatility and potential for innovation in healthcare.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.G.; methodology, T.G..; investigation, T.G.; data curation, B.P. and P.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, T.G.; writing—review and editing, B.P. and P.Z.; visualization, T.G.; supervision, B.P.; project administration, B.P.; funding acquisition, T.G., B.P and P.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Bulgarian National Science Fund, Project KP-06-N63/3.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Su, J.X.; Li, S.J.; Zhou, X.F.; Zhang, Z.J.; Yan, Y.; Liu, S.L.; Qi, Q. Chemotherapy-induced metastasis: Molecular mechanisms and clinical therapies. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tohme, S.; Simmons, R.L.; Tsung, A. Surgery for cancer: A trigger for metastases. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 1548–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zheng, C.; Huang, Y.; He, M.; Xu, W.W.; Li, B. Molecular mechanisms of chemo- and radiotherapy resistance and the potential implications for cancer treatment. MedComm. 2021, 2, 315–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zein, R.; Sharrouf, W.; Selting, K. Physical Properties of Nanoparticles That Result in Improved Cancer Targeting. J. Oncol. 2020, 2020, 5194780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Billone, P.S.; Mullett, W.M. Nanomedicine in action: An overview of cancer nanomedicine on the market and in clinical trials. J. Nanomater. 2013, 2013, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oei, A.L.; Kok, H.P.; Oei, S.B.; Horsman, M.R.; Stalpers, L.J.A.; Franken, N.A.P.; Crezee, J. Molecular and Biological Rationale of Hyperthermia as Radio- and Chemosensitizer. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 163–164, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linroti rotiwang, F.C.; Hsu, C.H. Nano-therapeutic cancer immunotherapy using hyperthermia-induced heat shock proteins: Insights from mathematical modeling. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 3529–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roti Roti, J.L. Cellular responses to hyperthermia (40–46 °C): Cell killing and molecular events. Int. J. Hyperth. 2008, 24, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, G.Y.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, H.I.; Park, J.; Baek, S.H. Hyperthermia Treatment as a Promising Anti-Cancer Strategy: Therapeutic Targets, Perspective Mechanisms and Synergistic Combinations in Experimental Approaches. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastinehad, A.R.; Anastos, H.; Wajswol, E.; Winoker, J.S.; Sfakianos, J.P.; Doppalapudi, S.K.; Carrick, M.R.; Knauer, C.J.; Taouli, B.; Lewis, S.C.; et al. Gold nanoshell-localized photothermal ablation of prostate tumors in a clinical pilot device study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 18590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Fan, K.; Yan, X. Iron Oxide Nanozyme: A Multifunctional Enzyme Mimetic for Biomedical Applications. Theranostics 2017, 7, 3207–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Hsu, J.C.; Koo, H.; Cormode, D.P. Repurposing ferumoxytol: Diagnostic and therapeutic applications of an FDA-approved nanoparticle. Theranostics 2022, 12, 796–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Luo, J.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, D.; Shen, Y.; Fang, Y.; Hu, L.; Liu, M.; Dai, C.; Peng, S.; et al. Iron and magnetic: New research direction of the ferroptosis-based cancer therapy. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2018, 8, 1933–1946. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jacques, S.L. Optical properties of biological tissues: A review. Phys. Med. Biol. 2013, 58, R37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Suo, Y.; Shi, H.; Liu, R.; Wu, F.; Wang, T.; Ma, L.; Liu, H.; Cheng, Z. Deep-tissue photothermal therapy using laser illumination at NIR-iia window. Nano-Micro Lett. 2020, 12, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastiancich, C.; Da Silva, A.; Estève, M.-A. Photothermal Therapy for the Treatment of Glioblastoma: Potential and Preclinical Challenges. Front. Oncol. 2021, 10, 3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, L.R.; Stafford, R.J.; Bankson, J.A.; Sershen, S.R.; Rivera, B.; Price, R.; Hazle, J.D.; Halas, N.J.; West, J.L. Nanoshell-mediated near-infrared thermal therapy of tumors under magnetic resonance guidance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 13549–13554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, S.; Tyagi, H.; Taylor, R.A.; Kumar, A. The influence of tumour blood perfusion variability on thermal damage during nanoparticle-assisted thermal therapy. Int. J. Hyperth. 2015, 31, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freis, B.; Ramirez, M.D.L.A.; Kiefer, C.; Harlepp, S.; Iacovita, C.; Henoumont, C.; Affolter-Zbaraszczuk, C.; Meyer, F.; Mertz, D.; Boos, A.; et al. Effect of the Size and Shape of Dendronized Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Bearing a Targeting Ligand on MRI, Magnetic Hyperthermia, and Photothermia Properties—From Suspension to In Vitro Studies. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, A.; Kolosnjaj-Tabi, J.; Abou-Hassan, A.; Plan Sangnier, A.; Curcio, A.; Silva, A.K.A.; Di Corato, R.; Neveu, S.; Pellegrino, T.; Liz-Marzán, L.M.; et al. Magnetic (Hyper)Thermia or Photothermia? Progressive Comparison of Iron Oxide and Gold Nanoparticles Heating in Water, in Cells, and In Vivo. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1803660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wu, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, Z.; Li, Q.; Kong, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, X.; Du, Y.P.; Jin, Y.; et al. Appropriate size of magnetic nanoparticles for various bioapplications in cancer diagnostics and therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 3092–3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozano-Pedraza, C.; Plaza-Mayoral, E.; Espinosa, A.; Sot, B.; Serrano, A.; Salas, G.; Blanco-Andujar, C.; Cotin, G.; Felder-Flesch, D.; Begin-Colin, S.; et al. Assessing the parameters modulating optical losses of iron oxide nanoparticles under near infrared irradiation. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3, 6490–6502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajabi, H. R Photocatalytic activity of quantum dots. Semiconductor Photocatalysis-Materials, Mechanisms and Applications. InTech, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Tang, S.; Tian, Y.; Zheng, R.; Zhou, L.; Yang, W. Highly Ligand-Directed and Size-Dependent Photothermal Properties of Magnetite Particles. Particle & Particle Systems Characterization 2016, 33, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guibert, C.; Dupuis, V.; Peyre, V.; Fresnais, J. Hyperthermia of magnetic nanoparticles: Experimental study of the role of aggregation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 28148–28154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Wang, S.; Zheng, R.; Zhu, X.; Jiang, X.; Fu, D.; Yang, W. Magnetic nanoparticle clusters for photothermal therapy with near-infrared irradiation. Biomaterials 2015, 39, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabana, S.; Curcio, A.; Michel, A.; Wilhelm, C.; Abou-Hassan, A. Iron Oxide Mediated Photothermal Therapy in the Second Biological Window: A Comparative Study between Magnetite/Maghemite Nanospheres and Nanoflowers. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulzar, A.; Ayoub, N.; Mir, J.F.; Alanazi, A.M.; Shah, M.A.; Gulzar, A. In vitro and in vivo MRI imaging and photothermal therapeutic properties of Hematite (α-Fe2O3) Nanorods. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine 2022, 33, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Southern, P.; Pankhurst, Q.A. Commentary on the clinical and preclinical dosage limits of interstitially administered magnetic fluids for therapeutic hyperthermia based on current practice and efficacy models. Int. J. Hyperth. 2018, 34, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Gao, S.; Yang, D.; Fang, Y.; Lin, X.; Jin, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Su, K.; Shi, K. Influencing factors and strategies of enhancing nanoparticles into tumors in vivo. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2021, 11, 2265–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak-Jary, J.; Machnicka, B. Pharmacokinetics of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for medical applications. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianopoulos, T.; Jain, R.K. Design considerations for nanotherapeutics in oncology. Nanomedicine 2015, 11, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Le, W.; Mei, T.; Wang, Y.; Chen, B.; Liu, Z.; Xue, C. Cell membrane camouflaged nanoparticles: A new biomimetic platform for cancer photothermal therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 4431–4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poudel, K.; Banstola, A.; Gautam, M.; Soe, Z.; Phung, C.D.; Pham, L.M.; Jeong, J.H.; Choi, H.G.; Ku, S.K.; Tran, T.H.; et al. Macrophage-membrane-camouflaged disintegrable and excretable nanoconstruct for deep tumor penetration. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 56767–56781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.; Peng, Y.; Wen, Y.; Li, X.; Du, D.; Dai, W.; Tian, W.; Meng, Y. Recent progress in cancer cell membrane-based nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2023, 14, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Zheng, R.; Fang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, W.; Sha, X. Red blood cell membrane camouflaged magnetic nanoclusters for imaging-guided photothermal therapy. Biomaterials 2016, 92, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, H.; Zhang, T.; Qin, S.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Shi, J.; Nice, E.C.; Xie, N.; Huang, C.; Shen, Z. Enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of nanoparticles for cancer treatme nt using versatile targeted strategies. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, T.A.; Bankson, J.; Aaron, J.; Sokolov, K. Hybrid plasmonic magnetic nanoparticles as molecular specific agents for MRI/optical imaging and photothermal therapy of cancer cells. Nanotechnology 2007, 18, 325101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.-J.; Lin, P.-Y.; Huang, P.-H.; Kuo, C.-Y.; Shalumon, K.T.; Chen, M.-Y.; Chen, J.-P. Magnetic Graphene Oxide for Dual Targeted Delivery of Doxorubicin and Photothermal Therapy. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.M.; Fu, C.P.; Fang, J.Z.; Xu, X.D.; Wei, X.H.; Tang, W.J.; Jiang, X.Q.; Zhang, L.M. Hyaluronan-modified superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for bimodal breast cancer imaging and photothermal therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaznavi, H.; Hosseini-Nami, S.; Kamrava, S.K.; Irajirad, R.; Maleki, S.; Shakeri-Zadeh, A.; Montazerabadi, A. Folic acid conjugated peg coated gold–iron oxide core–shell nanocomplex as a potential agent for targeted photothermal therapy of cancer. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 1594–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Tang, J.; Zheng, R.; Guo, G.; Dong, A.; Wang, Y.; Yang, W. Nuclear-targeted multifunctional magnetic nanoparticles for photothermal therapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, Y.; Je, J.Y.; Moorthy, M.S.; Seo, H.; Cho, W.H. pH and NIR-light-responsive magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for mitochondria-mediated apoptotic cell death induced by chemo-photothermal therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 531, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, F.; Bao, Y.-W.; Wu, F.-G. Improving the Phototherapeutic Efficiencies of Molecular and Nanoscale Materials by Targeting Mitochondria. Molecules 2018, 23, 3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y.H.; Park, K. Targeted drug delivery to tumors: Myths, reality and possibility. J. Control. Release 2011, 153, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvati, A.; Pitek, A.; Monopoli, M.P.; Prapainop, K.; Bombelli, F.B.; Hristov, D.; Kelly, P.; Åberg, C.; Mahon, E.; Dawson, K.A. Transferrin-functionalized nanoparticles lose their targeting capabilities when a biomolecule corona adsorbs on the surface. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kale, S.; Burga, R.; Sweeney, E.; Zun, Z.; Sze, R.; Tuesca, A.; Subramony, A.; Fernandes, R. Composite Iron Oxide—Prussian Blue Nanoparticles for Magnetically Guided T1-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Photothermal Therapy of Tumors. IJN 2017, 12, 6413–6424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melancon, MP.; Elliott, A.; Ji, X.; Shetty, A.; Yang, Z.; Tian, M.; Taylor, B.; Stafford, RJ.; Li, C. Theranostics with multifunctional magnetic gold nanoshells: photothermal therapy and T2* magnetic resonance imaging. Invest Radiol. 2011, 46, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Chen, L.; Liu, F.; Qi, X.; Ge, Y.; Shen, S. Remotely controlled drug release based on iron oxide nanoparticles for specific therapy of cancer. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2017, 152, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ali, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Xu, N.; Yin, H.; Sheng, F.; Hou, Y. A pH-responsive biomimetic drug delivery nanosystem for targeted chemo-photothermal therapy of tumors. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 4274–4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Deng, H.; Sun, L.; Lin, H.; Kang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yang, W.; et al. Yolk–shell nanovesicles endow glutathione–responsive concurrent drug release and T1 MRI activation for cancer theranostics. Biomaterials 2020, 244, 119979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Lu, H.; Cao, R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Ge, R.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Xiao, L.; Su, L.; et al. A novel MMP-responsive nanoplatform with transformable magnetic resonance property for quantitative tumor bioimaging and synergetic chemo-photothermal therapy. Nano Today 2022, 45, 101524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Ruan, Q.; Zhuo, X.; Xia, X.; Hu, J.; Fu, R.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, H. Photothermal Nanomaterials: A Powerful Light-to-Heat Converter. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 6891–6952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasparis, G.; Sangnier, A.P.; Wang, L.; Efstathiou, C.; LaGrow, A.P.; Sergides, A.; Wilhelm, C.; Thanh, N.T.K. Zn doped iron oxide nanoparticles with high magnetization and photothermal efficiency for cancer treatment. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 11, 787–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paściak, A.; Marin, R.; Abiven, L.; Pilch-Wróbel, A.; Misiak, M.; Xu, W.; Prorok, K.; Bezkrovnyi, O.; Marciniak, Ł.; Chanéac, C.; et al. Quantitative Comparison of the Light-to-Heat Conversion Efficiency in Nanomaterials Suitable for Photothermal Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 33555–33566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Peng, C.; Shen, M.; Shi, X. Dendrimer-Stabilized Gold Nanoflowers Embedded with Ultrasmall Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Multimode Imaging–Guided Combination Therapy of Tumors. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2018, 5, 1801612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, M.; Zhou, B.; Zhou, F.; Murray, C.; Towner, R.A.; Smith, N.; Saunders, D.; Xie, G.; Chen, W.R. PEGylated reduced-graphene oxide hybridized with Fe3O4 nanoparticles for cancer photothermal-immunotherapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 7406–7414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.S.; Verwilst, P.; Sharma, A.; Shin, J.; Sessler, J.L.; Kim, J.S. Organic molecule-based photothermal agents: An expanding photothermal therapy universe. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 2280–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Xu, J.; Jin, H.; Yi, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Sun, Y.; Shi, W.; He, Y.; et al. Polypyrrole Nanosheets Prepared by Rapid In Situ Polymerization for NIR-II Photoacoustic-Guided Photothermal Tumor Therapy. Coatings 2023, 13, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Zhang, D.; Zeng, Y.; Wu, L.; Liu, X.; Liu, J. Nanocluster of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles coated with poly(dopamine) for magnetic field-targeting, highly sensitive MRI and photothermal cancer therapy. Nanotechnology 2015, 26, 115102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Ding, Y.; Wang, K.; Xing, Z.; Sun, X.; Guo, W.; Hong, X.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Y. Enhanced photothermal-photodynamic therapy for glioma based on near-infrared dye functionalized Fe3O4 superparticles. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 381, 122693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Ren, Q.; Hao, R.; Sun, Z. Innovative strategies to boost photothermal therapy at mild temperature mediated by functional nanomaterials. Mater. Des. 2022, 214, 110391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daldrup-Link, H.E. Ten Things You Might Not Know about Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Radiology 2017, 284, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittrich, H.; Peldschus, K.; Raabe, N.; Kaul, M.; Adam, G. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles in biomedicine: Applications and developments in diagnostics and therapy. Rofo 2013, 185, 1149–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alphandéry, E. Iron oxide nanoparticles as multimodal imaging tools. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 40577–40587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucheryavy, P.; He, J.; John, V.T.; Maharjan, P.; Spinu, L.; Goloverda, G.Z.; Kolesnichenko, V.L. Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles with Variable Size and an Iron Oxidation State as Prospective Imaging Agents. Langmuir 2012, 29, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Liu, L.; Mo, C.; Zhou, X.; Chen, D.; He, Y.; He, H.; Kang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, G. Polyethylene glycol-coated ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles-coupled sialyl Lewis X nanotheranostic platform for nasopharyngeal carcinoma imaging and photothermal therapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, L.; Ji, W. Recent progress on single-molecule localization microscopy. Biophys Rep. 2021, 7, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Wu, J.B.; Pan, D. Review on Near-Infrared Heptamethine Cyanine Dyes as Theranostic Agents for Tumor Imaging, Targeting, and Photodynamic Therapy. J. Biomed. Opt. 2016, 21, 050901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.T.; Li, X.; Kong, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, L.; Xue, B.; Wu, F.; Cao, D.; et al. A highly effective in vivo photothermal nanoplatform with dual imaging-guide therapy of cancer based on the charge reversal complex of dye and iron oxide. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 8321–8327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapsford, K.E.; Pons, T.; Medintz, I.L.; Mattoussi, H. Biosensing with Luminescent Semiconductor Quantum Dots. Sensors 2006, 6, 925–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.S.; Paliouras, M.; Trifiro, M.A. Functionalized Carbon Nanoparticles as Theranostic Agents and Their Future Clinical Utility in Oncology. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Mu, Q.; Revia, R.; Wang, K.; Tian, B.; Lin, G.; Lee, W.; Hong, Y.-K.; Zhang, M. Iron oxide-carbon core-shell nanoparticles for dual-modal imaging-guided photothermal therapy. J. Control. Release 2018, 289, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Gao, M.Y.; Zhu, Q.; Chi, B.; Zeng, L.W.; Hu, J.M.; Shen, A.G. Monodispersed plasmonic prussian blue nanoparticles for zero-background SERS/mri-guided phototherapy. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 3292–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Sheng, B.; Tian, H.; Chen, Q.; Yang, Y.; Bui, B.; Pi, J.; Cai, H.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J.; et al. Real-time SERS monitoring anticancer drug release along with SERS/MR imaging for pH-sensitive chemo-phototherapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 1303–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Hai, J.; Wang, B. Se Atom-Induced Synthesis of Concave Spherical Fe3O4@Cu2O Nanocrystals for Highly Efficient MRI–SERS Imaging-Guided NIR Photothermal Therapy. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 2018, 35, 1800197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.C.; Hu, Y.; Yang, J.; Wei, P.; Sun, W.J.; Shen, M.W.; Zhang, G.X.; Shi, X.Y. Hyaluronic acid-modified Fe3O4@Au core/shell nanostars for multimodal imaging and photothermal therapy of tumors. Biomaterials 2015, 38, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Deng, G.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Q.; Lu, J. Multifunctional PS@CS@Au-Fe3O4-FA Nanocomposites for CT, MR and Fluorescence Imaging Guided Targeted-Photothermal Therapy of Cancer Cells. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 4221–4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, J.; Yao, J.; Wang, L.V. Photoacoustic tomography: Principles and advances. Electromagn. Waves (Camb.) 2014, 147, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Q.; Li, Z.; Ye, J.; Li, Z.; Fu, F.; Lin, S.-L.; Chang, C.A.; Yang, H.; Song, J. Magnetic targeted near–infrared II PA/MR imaging guided photothermal therapy to trigger cancer immunotherapy. Theranostics 2020, 10, 4997–5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.-L.; Ma, H.; Li, G.; Li, Y.; Gao, F.; Peng, M.; Fan, H.M.; Liang, X.-J. Fe3O4–Pd Janus nanoparticles with amplified dual-mode hyperthermia and enhanced ROS generation for breast cancer treatment. Nanoscale Horiz. 2019, 4, 1450–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-D.; Liang, X.-L.; Yue, X.-L.; Wang, J.-R.; Li, C.-H.; Deng, Z.-J.; Jing, L.-J.; Lin, L.; Qu, E.-Z.; Wang, S.-M.; et al. Imaging guided photothermal therapy using iron oxide loaded poly(lactic acid) microcapsules coated with graphene oxide. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, H.; Wang, J.; Tong, S.; Jin, Y.; Wang, S.; Qu, E.; Bao, G.; Dai, Z. Gold nanoshelled liquid perfluorocarbon magnetic nanocapsules: A nanotheranostic platform for bimodal ultrasound/magnetic resonance imaging guided photothermal tumor ablation. Theranostics 2014, 4, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Huangfu, L.; Li, H.; Yang, D. Research progress of hyperthermia in tumor therapy by influencing metabolic reprogramming of tumor cells. International Journal of Hyperthermia, 2023, 40, 2270654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urano, M. Invited Review: For the Clinical Application of Thermochemotherapy Given at Mild Temperatures. Int. J. Hyperth. 1999, 15, 79–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Dun, Y.; Xie, L.; Jiang, W.; Sun, X.; Hu, P.; Zheng, S.; Yu, Y. Preparation of doxorubicin-loaded porous iron Oxide@ polydopamine nanocomposites for MR imaging and synergistic photothermal-chemotherapy of cancer. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2021, 208, 112107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kong, J.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Y. Synthesis of Multi-Stimuli Responsive Fe3O4 Coated with Diamonds Nanocomposite for Magnetic Assisted Chemo-Photothermal Therapy. Molecules 2023, 28, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, Y.M.; Je, J.; Cha, S.H.; Oh, Y.; Cho, W.H. Synergistic combination of chemo-phototherapy based on temozolomide/ICG-loaded iron oxide nanoparticles for brain cancer treatment. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 42, 1709–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauser, A.K.; Mitov, M.I.; Daley, E.F.; McGarry, R.C.; Anderson, K.W.; Hilt, J.Z. Targeted iron oxide nanoparticles for the enhancement of radiation therapy. Biomaterials 2016, 105, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Jung, S.; Baek, S.H. Combination Therapy of Radiation and Hyperthermia, Focusing on the Synergistic Anti-Cancer Effects and Research Trends. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Zheng, M.; Wu, J.; Li, C.; Shen, D.; Yang, D.; Li, L.; Ge, M.; Chang, Z.; Dong, W. Core-Shell Magnetic Gold Nanoparticles for Magnetic Field-Enhanced Radio-Photothermal Therapy in Cervical Cancer. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorito, S.; Soni, N.; Silvestri, N.; Brescia, R.; Gavilán, H.; Conteh, J.S.; Mai, B.T.; Pellegrino, T. Fe3O4@Au@Cu2−xS Heterostructures Designed for Tri-Modal Therapy: Photo- Magnetic Hyperthermia and 64Cu Radio-Insertion. Small 2022, 18, 2200174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overchuk, M.; Weersink, R.A.; Wilson, B.C.; Zheng, G. Photodynamic and Photothermal Therapies: Synergy Opportunities for Nanomedicine. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 7979–8003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, W.-J.; Chen, Y.-C.; Huang, C.-C.; Yang, L.; Yu, J.; Huang, S.-W.; Lin, C.-H. Iron Hydroxide/Oxide-Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite for Dual-Modality Photodynamic and Photothermal Therapy In Vitro and In Vivo. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, H.; Zhou, J.Y. Chlorin e6-modified iron oxide nanoparticles for photothermal-photodynamic ablation of glioblastoma cells. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Hu, X.; Chen, L.; Wu, X.; Wang, D.; Wang, H.; Liang, C. Fe3O4@TiO2 Microspheres: Harnessing O2 Release and ROS Generation for Combination CDT/PDT/PTT/Chemotherapy in Tumours. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, W.; Zhang, M.; Wu, F.; Zheng, T.; Sheng, B.; Liu, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhou, N.; Sun, Y. A theranostic nanocomposite with integrated black phosphorus nanosheet, Fe3O4@ MnO2-doped upconversion nanoparticles and chlorin for simultaneous multimodal imaging, highly efficient photodynamic and photothermal therapy. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 391, 123525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Ruan, L.; Wang, D.; Zhang, J.; Tang, J.; Guo, C. Boosting chemotherapy of bladder cancer cells by ferroptosis using intelligent magnetic targeting nanoparticles. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2024, 234, 113664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, L.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, Z.; Mao, W.; Xue, R.; Chen, R.; Luo, J. Modulated ultrasmall γ-Fe2O3 nanocrystal assemblies for switchable magnetic resonance imaging and photothermal-ferroptotic-chemical synergistic cancer therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2211251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cun, J.-E.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Li, J.; Pan, Q.; Gao, W.; Luo, K.; He, B.; Pu, Y. Photo-Enhanced Upcycling H2O2 into Hydroxyl Radicals by IR780-Embedded Fe3O4@MIL-100 for Intense Nanocatalytic Tumor Therapy. Biomaterials 2022, 287, 121687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. S., A.; Lu, Y.-J.; Chen, J.-P. Optimization of the Preparation of Magnetic Liposomes for the Combined Use of Magnetic Hyperthermia and Photothermia in Dual Magneto-Photothermal Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Guo, S.; Zu, X.; Zhuang, Y.; Fan, D.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Ji, Z.; Cheng, J.; Pang, X. Polypyrrole-Coated Magnetite Vortex Nanoring for Hyperthermia-Boosted Photothermal/Magnetothermal Tumor Ablation Under Photoacoustic/Magnetic Resonance Guidance. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Q.; Dai, X.; Zhang, P.; Tan, X.; Zhong, Y.; Yao, C.; Song, M.; Song, G.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, G.; et al. Fe3O4@Au composite magnetic nanoparticles modified with cetuximab for targeted magneto-photothermal therapy of glioma cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 2491–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naud, C.; Thébault, C.; Carrière, M.; Hou, Y.; Morel, R.; Berger, F.; Diény, B.; Joisten, H. Cancer treatment by magneto-mechanical effect of particles, a review. Nanoscale Adv. 2020, 2, 3632–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, S.; Hallali, N.; Lalatonne, Y.; Hillion, A.; Antunes, J.C.; Serhan, N.; Clerc, P.; Fourmy, D.; Motte, L.; Carrey, J.; et al. Magneto-mechanical destruction of cancer-associated fibroblasts using ultra-small iron oxide nanoparticles and low frequency rotating magnetic fields. Nanoscale Adv. 2022, 4, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzzi, B.; Albino, M.; Gabbani, A.; Omelyanchik, A.; Kozenkova, E.; Petrecca, M.; Innocenti, C.; Balica, E.; Lavacchi, A.; Scavone, F. Star-Shaped Magnetic-Plasmonic Au@ Fe3O4 Nano-Heterostructures for Photothermal Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 29087–29098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.; Mohsin, A.; Zaman, W.Q.; Zhang, Z.; Guan, W.; Chu, M.; Zhuang, Y.; Guo, M. Urchin-like Magnetic Microspheres for Cancer Therapy through Synergistic Effect of Mechanical Force, Photothermal and Photodynamic Effects. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Zeng, X.; Mei, L. An optimal portfolio of photothermal combined immunotherapy. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2022, 3, 100898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, H.-Y.; Cheng, H.-W.; Kuo, C.-C.; Chen, S.-Y. Dual-Sensitive Gold-Nanocubes Platform with Synergistic Immunotherapy for Inducing Immune Cycle Using NIR-Mediated PTT/NO/IDO. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, K.; Hoover, A.R.; Li, M.; Towner, R.A.; Mukherjee, P.; Zhou, F.; Qu, J.; et al. Synergistic interventional photothermal therapy and immunotherapy using an iron oxide nanoplatform for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Acta Biomater. 2022, 138, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Wu, Q.; Wang, M.; Hoover, A.; Wang, X.; Zhou, F.; Towner, R.A.; Smith, N.; Saunders, D.; Song, J.; et al. Immunologically modified MnFe2O4 nanoparticles to synergize photothermal therapy and immunotherapy for cancer treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 396, 125239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, T.; Gao, J. Biocompatible Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Targeted Cancer Gene Therapy: A Review. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, D.; Prajapati, S.K.; Jain, A.; Singhal, R. Nano-formulated siRNA-based therapeutic approaches for cancer therapy. Nano Trends, 2023, 1, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayteck, L.; Xiong, R.; Braeckmans, K.; De Smedt, S.C.; Raemdonck, K. Comparing photoporation and nucleofection for delivery of small interfering RNA to cytotoxic T cells. J. Control. Release 2017, 267, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Yuan, G.; Xu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Mao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, L.; Li, W.; Wu, A.; Hu, W.; et al. Photoacoustic and magnetic resonance imaging-based gene and photothermal therapy using mesoporous nanoagents. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 9, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).