1. Introduction

Vegetation is a crucial part of terrestrial ecosystems and plays a vital role in ecosystem functioning and the provision of ecosystem services [

1]. Particularly in arid regions northwest China, the fragile natural environment combined with the unreasonable development and exploitation of natural resources has exacerbated ecological problems such as vegetation degradation, soil erosion, and desertification, vegetation holds significant ecological importance [

2,

3]. Due to its pivotal role and dynamic nature, understanding vegetation dynamics in response to climate change and human activities is a central research focus [

4]. However, recent studies have argued that due to differences in local climate factors, some inappropriate ecological restoration measures that ignored these conditions in ecologically vulnerable regions have resulted in low survival rates of restored plants and even local ecosystem deterioration[

5,

6,

7,

8]. Therefore, examining the spatial and temporal variations of vegetation greenness on a regional scale is crucial for ecological protection and sustainable development [

9].

The succession of vegetation cover is influenced by climate, natural environmental factors, and human activities [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. In recent years, various human activities, such as urban expansion and resource development, have profoundly disturbed the regional ecological environment, posing a serious threat to its stability [

26,

27,

28,

29]. Previous studies have extensively investigated the spatiotemporal evolution of vegetation cover in the arid regions of northwest China [

30,

31], driven by both climate change and human activities [

32,

33,

34]. Techniques such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and remote sensing (RS) have been employed to study the dynamic evolution of vegetation [

26]. For instance, a fractional vegetation coverage (FVC) time series analysis from 1986 to 2021 in the Qilian Mountain National Nature Reserve revealed that climate variability and human activities contributed significantly to vegetation variations [

35]. Similarly, the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau’s vegetation changes have been attributed to human activities and climate variability [

34,

36,

37]. Meanwhile, extreme weather and land desertification caused by climate changes have heightened awareness among humans about the crisis of ecological environment deterioration [

38].

The Hexi Corridor, situated in northwest China, is a typical representation of arid regions, with the Shule River Basin (SRB) being one of its primary inland river basins. Characterized by a landscape marked by mountains, oases, and deserts, the SRB experiences limited rainfall, high evaporation rates, and uneven distribution of water resources, which makes the carrying capacity of the ecosystem more delicate and vulnerable. It is also among the most susceptible regions globally to the impacts of climate change [

39]. Overexploitation of water resources has exacerbated ecological issues in the basin, including sparse vegetation, grassland degradation, soil salinization, wetland reduction and reduction, and desertification [

40]. These challenges are anticipated to influence future development planning in the area significantly. Therefore, studying the spatiotemporal dynamics of vegetation in the SRB and its responses to climate change and human activities holds scientific significance and crucial economic and social implications. Despite previous studies focusing on the impact of natural and social factors on the SRB, few have conducted large-scale and long-term dynamic analyses of vegetation coverage. The ecological fragility of the basin, exacerbated by climate variability and human activities, poses significant challenges. Extreme events such as precipitation, drought, and human activities like farming, industrial, and construction further destabilize vegetation coverage [

35,

41,

42]. Monitoring vegetation growth and change is essential for promoting ecological protection and sustainable economic development in the region. It is imperative to undertake dynamic research on FVC in the basin. FVC quantifies surface vegetation status and is crucial for assessing vegetation change, soil and water conservation, and climate impacts.

In this study, we assess the impact of climate change and human activities on vegetation change by focusing on the Shule River Basin (SRB). We extracted fractional vegetation coverage (FVC) time series data using the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform from 2000 to 2019 and conducted spatiotemporal analyses to monitor vegetation coverage changes. The objectives include monitoring temporal and periodic changes in vegetation coverage and analyzing spatial distribution to gain insights into the ecological consequences of climate variations and human activities, particularly in arid ecotone zones. The main goals of this study are: (1) to analyze the temporal and spatial dynamic trends of vegetation in the SRB; (2) to identify the response mechanisms of vegetation changes in the SRB to human activities, such as road construction; and (3) to determine the dominant climate factors affecting vegetation change in the SRB; (4) Identify land cover dynamics and their responses to climate change and human activities.

2. Materials and Methods

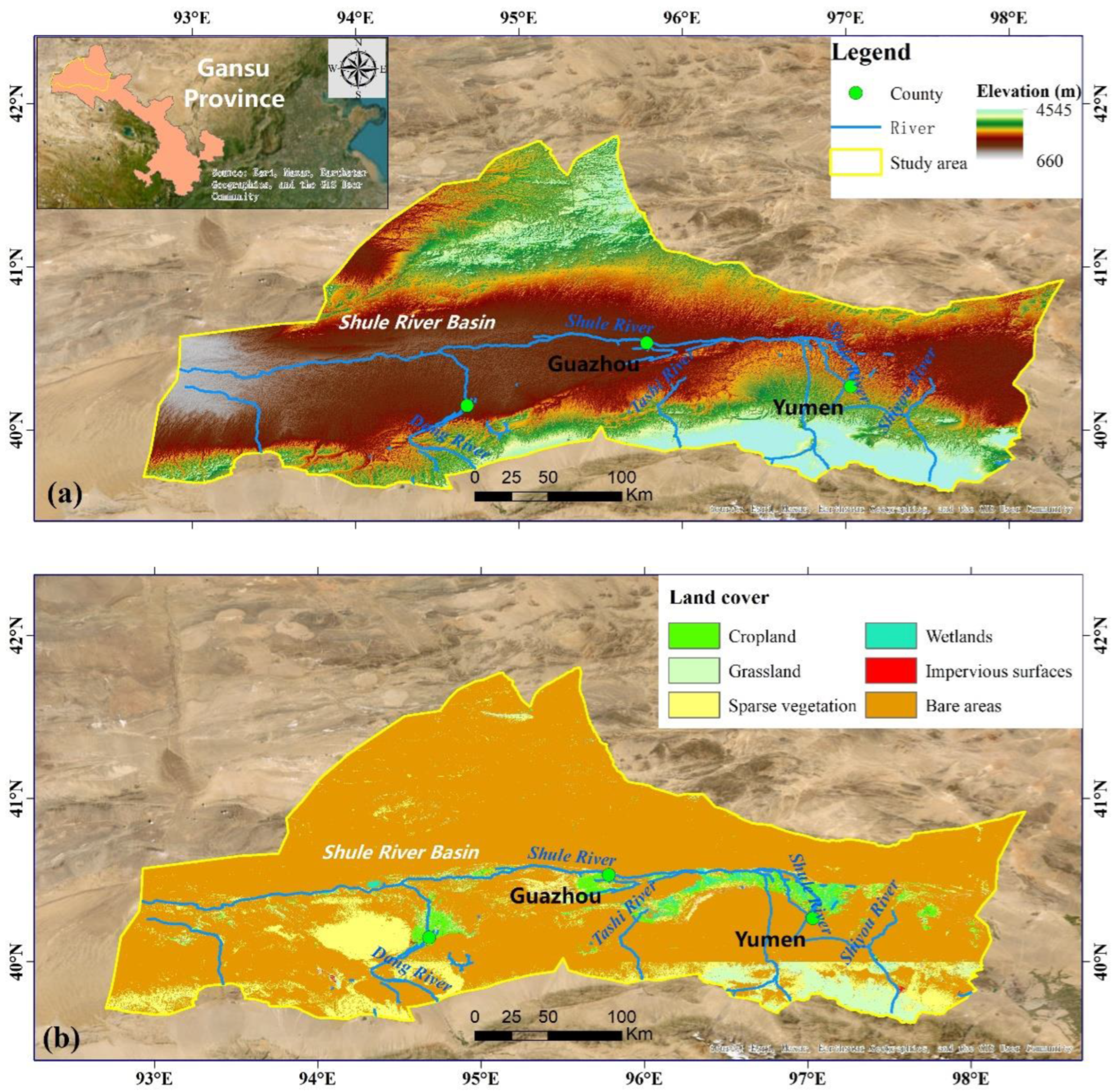

2.1. Study Area

The SRB is situated between 92°11′E and 98°30′E longitude and between 38°0′N and 42°48′N latitude at the westernmost edge of the Hexi Corridor. This region is a transition zone between the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and the Alashan Plateau of Inner Mongolia, forming an integral part of the historic “Silk Road”. Spanning an area of approximately 100,000 km

2, the Shule River is one of the three major inland rivers in the Hexi Corridor (

Figure 1a). The SRB experiences a temperate, arid climate with ample and intense solar radiation. The annual average temperature ranges from 7 to 9 °C. Despite its limited annual average rainfall of less than 60 mm, the region witnesses high evaporation rates ranging from 1500 to 3000 mm [

43]. Altitudes in the study area vary significantly, ranging from 660 to 4545 meters above sea level.

Surface water resources in the SRB are scarce. The land cover types in the SRB encompass a diverse range of ecosystems, including croplands, grasslands, sparse vegetation, wetlands, impervious surfaces, and bare areas (

Figure 1b). This unique geographical and climatic setting, coupled with its historical significance as part of the Silk Road, makes the SRB an ideal study area for investigating vegetation dynamics in response to climate change and human activities.

2.2. Datasets

2.2.1. Vegetation

The primary dataset utilized in this study is the annual FVC, derived from annual Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) data. The NDVI data is obtained through Landsat TM/OLI satellite data products, spanning Landsat 5 TM, Landsat 7 ETM, and Landsat 8 OLI, synthesized via the GEE platform (

https://developers.google.com/earth-engine), covering the period from 2000 to 2019. The spatial resolution of the data is 30 meters. This approach ensures the comprehensive assessment of vegetation dynamics over the study period, allowing for detailed spatiotemporal analysis of vegetation changes in the SRB. The detailed calculation methodology will be elaborated in

Section 2.3.1.

2.2.2. Land Cover

The land cover data utilized in this study were sourced from the Global 30-meter Land Cover Products with a Fine Classification System in 2020 (GLC_FCS30-2020). This dataset provides comprehensive land cover information with an exemplary classification system derived from continuous time-series Landsat imagery on the GEE platform [

53,

54,

55]. The GLC_FCS30-2020 dataset offers detailed and up-to-date land cover classification for the study area, enabling precise analysis of land cover dynamics. The dataset covers various land cover types, including Cropland, Grassland, Sparse vegetation, Wetlands, Impervious Surface, and Bare areas. The land cover types in the study area are defined as follows: “Cropland” refers to land used for agricultural purposes, including mature, cultivated land, newly reclaimed land, fallow land, rotational rest land, and areas undergoing grassland rotation cropping, among others. “Grassland” encompasses various types of land predominantly covered by herbaceous plants, forming different grasslands. “Sparse vegetation” represents areas with limited vegetation cover, characterized by scattered vegetation patches. “Wetlands” includes areas with high water saturation, such as marshes, swamps, and other waterlogged habitats. “Impervious Surface” refers to urban and rural residential areas, industrial zones, mining sites, transportation infrastructure, and other human-built surfaces that prevent water infiltration. “Bare areas” denotes areas devoid of vegetation cover, typically consisting of exposed soil, rock, or other non-vegetated surfaces.

These land cover categories provide valuable insights into the landscape composition and land use patterns within the study area, facilitating a comprehensive analysis of vegetation dynamics and ecosystem changes over time.

2.2.3. Precipitation

The precipitation data utilized in this study were obtained from the Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation with Station data (CHIRPS). CHIRPS is a long-term quasi-global rainfall dataset spanning over 30 years. It integrates high-resolution satellite imagery with in-situ station data to generate gridded rainfall time series, enabling trend analysis and seasonal drought monitoring [

44]. The CHIRPS dataset provides reliable and spatially detailed information on precipitation patterns, making it suitable for analyzing temporal variations in rainfall. We extracted the annual mean precipitation data from 2000 to 2019 using the GEE platform for this study. The precipitation data were resampled to a 30-meter resolution using ArcGIS 10.8 software. Resampling the precipitation data to a finer resolution enhances its utility by capturing localized variations in rainfall patterns and facilitating a more accurate analysis of its effects on vegetation dynamics. This high-resolution precipitation dataset is valuable input for assessing the relationship between precipitation variability and vegetation changes in the SRB over the study period.

2.2.4. Land Surface Temperature

The Landsat series of satellites provide valuable data for monitoring land surface temperature (LST), offering high spatial resolution and frequent revisit times, researchers can obtain reliable and spatially detailed LST data for various applications, including climate studies, environmental monitoring, and land surface modeling [

37]. The LST data used in this study were acquired from the GEE platform using open-source code designed explicitly for LST estimation from the Landsat series [

45]. Accessing LST data through the GEE platform and utilizing open-source code for processing ensures transparency, reproducibility, and accessibility of the data, facilitating robust scientific analysis and interpretation of land surface temperature dynamics in the SRB [

46].

2.2.5. Surface Water Area

The surface water data utilized in this study were obtained from the JRC Monthly Water History (v1.4) dataset. This dataset offers maps depicting the spatial distribution and temporal changes in surface water from 1984 to 2021. With a spatial resolution of 30 meters, the JRC Monthly Water History dataset provides detailed information on the extent and dynamics of surface water bodies [

37]. By analyzing the temporal distribution of surface water, we can assess changes in water bodies, including fluctuations in size, seasonal variations, and long-term trends in the SRB [

47,

48].

2.2.6. DEM and Road

The Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data were acquired from the Geospatial Data Cloud (

https://www.gscloud.cn/). The dataset is derived from the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) Global Digital Elevation Model (GDEM) version 1 (V1). With a spatial resolution of 30 meters by 30 meters, the DEM dataset provides detailed information about the terrain elevation in the study area. Road data comes from OpenStreetMap (OSM;

www.openstreetmap.org).

2.3. Methods

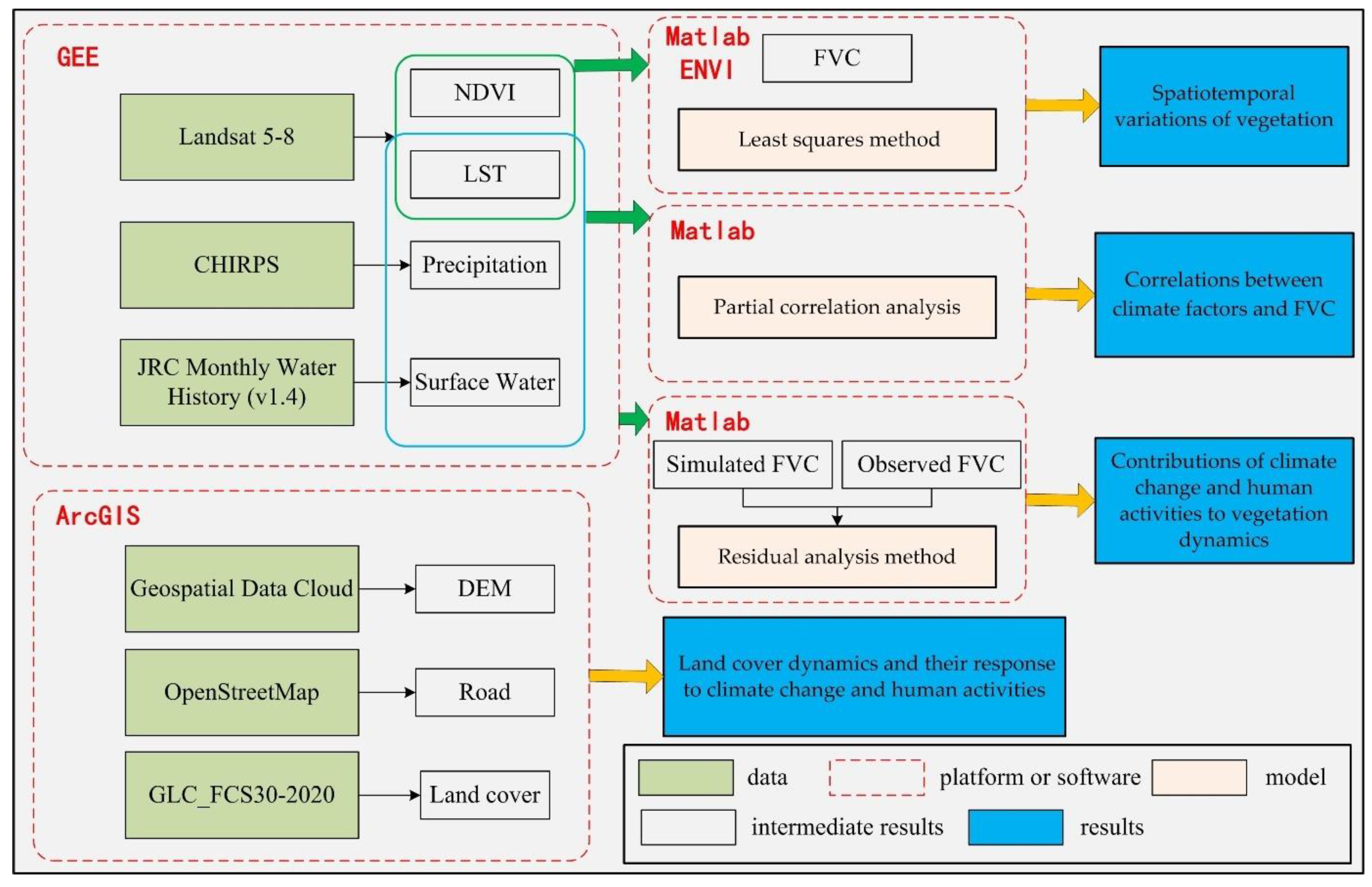

Figure 2 shows the framework of the research. Firstly, the least squares method was adopted to detect vegetation trends from 2000 to 2019. Secondly, the relationship between climatic factors and FVC was evaluated with partial correlation analysis. Finally, the residual analysis method was used to explore the main driving factor of spatial-temporal changes of FVC.

2.3.1. Retrieval of FVC Time Series Data

Observations of the NDVI via remote sensing satellites are susceptible to various factors that may affect data quality. The annual maximum method is commonly employed [

49]. This method utilizes the following calculation formula:

where

NDVIi represents the NDVI value in the

ith year,

NDVIj is the NDVI value in the

j th month of

i th year, and

j is valued in the range of 1–12. The NDVI value was calculated as Equation (2):

where

NIR is the near-infrared band spectral reflectance, and

R is the red band spectral reflectance.

The NDVI is commonly used to derive the FVC [

50]. The FVC can better measure surface vegetation conditions and ecological environment changes [

35]. The FVC was calculated using the Band Math calculation module of ENVI 5.0 after projection conversion and mosaicking with Equation (3):

where

NDVIsoil and

NDVIveg represent the values of bare soil and full vegetation cover (with a 95% confidence limit), respectively [

35,

51]. As suggested in a previous study, and in terms of the actual situation of the study area, the FVC was divided into five classes, namely extremely low [0–0.2], low [0.2–0.4], middle [0.4–0.6], middle high [0.6–0.8], and high [0.8–1.0] vegetation cover [

35].

2.3.2. Vegetation Trend Analysis

The linear trend of vegetation conditions was estimated using a simple linear regression in the study area from 2000 to 2019 and every five years separately (2000–2004, 2005–2009, 2010–2014, 2015–2019) on a pixel scale. Trend analysis at the pixel scale can provide a more accurate reflection of vegetation spatiotemporal variations, which can better simulate areas where vegetation coverage is significantly improved and degraded [

7,

52]. The slope of the trend line in the multi-year regression equation for a single pixel represents the variation rate, which is solved by the least squares method as follows [

5,

53,

54,

55]:

where

n is the sequence number of monitoring years (we divided the monitoring period (2000-2019) into four periods, n is 5 for each period),

FVCi is the maximum value for the specific year, “

Slope” is the slope of the linear regression, which represents the trend of

FVC during each period. A positive

slope (

slope > 0.01) indicates an increased trend of FVC and vice versa. The significance of variation was determined using F-tests to calculate confidence levels (p < 0.05) [

56,

57]. The vegetation trend analysis was performed in Matlab 2022b.

2.3.3. Partial Correlation Analysis

Partial correlation analysis describes the relationship between two variables while taking away the effects of another variable or several other variables [

52]. We employed partial correlation analysis to evaluate the relationship between climatic factors (LST and precipitation) and FVC, which can exclude the confounding effects of other variables [

58]. The calculation of the partial correlation coefficient can be expressed as follows:

where r

12, r

23, and r

13 refer to the correlation coefficients between Y and X

1, Y and X

2, and X

1 and X

2, respectively. r

12.3 refers to the partial correlation coefficient between Y and X

1 when the variable X

2 is fixed [

59]. Each partial correlation coefficient is tested using the t-test (p < 0.05) [

8].

2.3.4. Calculating Contribution of Driving Factors to Variation in FVC

It is commonly assumed that FVC is affected by the combined impact of two factors: human activities and climate variability [

26,

27,

29,

35,

58,

60,

61,

62,

63]. The response of vegetation conditions to temperature and precipitation is often nonlinear [

41]. The residual analysis method calculates the relative contributions of climate change and human activities to attribute better the observed vegetation changes to climate change and human activities [

60,

64].

First, a binary linear regression equation is constructed based on LST and precipitation to predict the FVC only affected by climate change. Then, the predicted FVC value (FVCc) is calculated using the LST and precipitation data. Finally, the difference between the observed FVC and

FVCc is calculated and defined as the FVC residual, representing the variation rate of the contribution of unknown factors to FVC, which means the impact of human activities on FVC in this paper. The regression model for each pixel is as follows:

where

FVCc is the simulated value of the multiple linear regression equation built based on climate factors,

a,

b, and

c are regression coefficients of land surface temperature, precipitation, and a constant term;

εi is the FVC residual between the observed FVC and simulated FVC in the

ith year;

εi > 0 and

εi<0 separately indicate that human activities promote vegetation improvement and vegetation degradation.

3. Results

3.1. Temporal Change of Vegetation

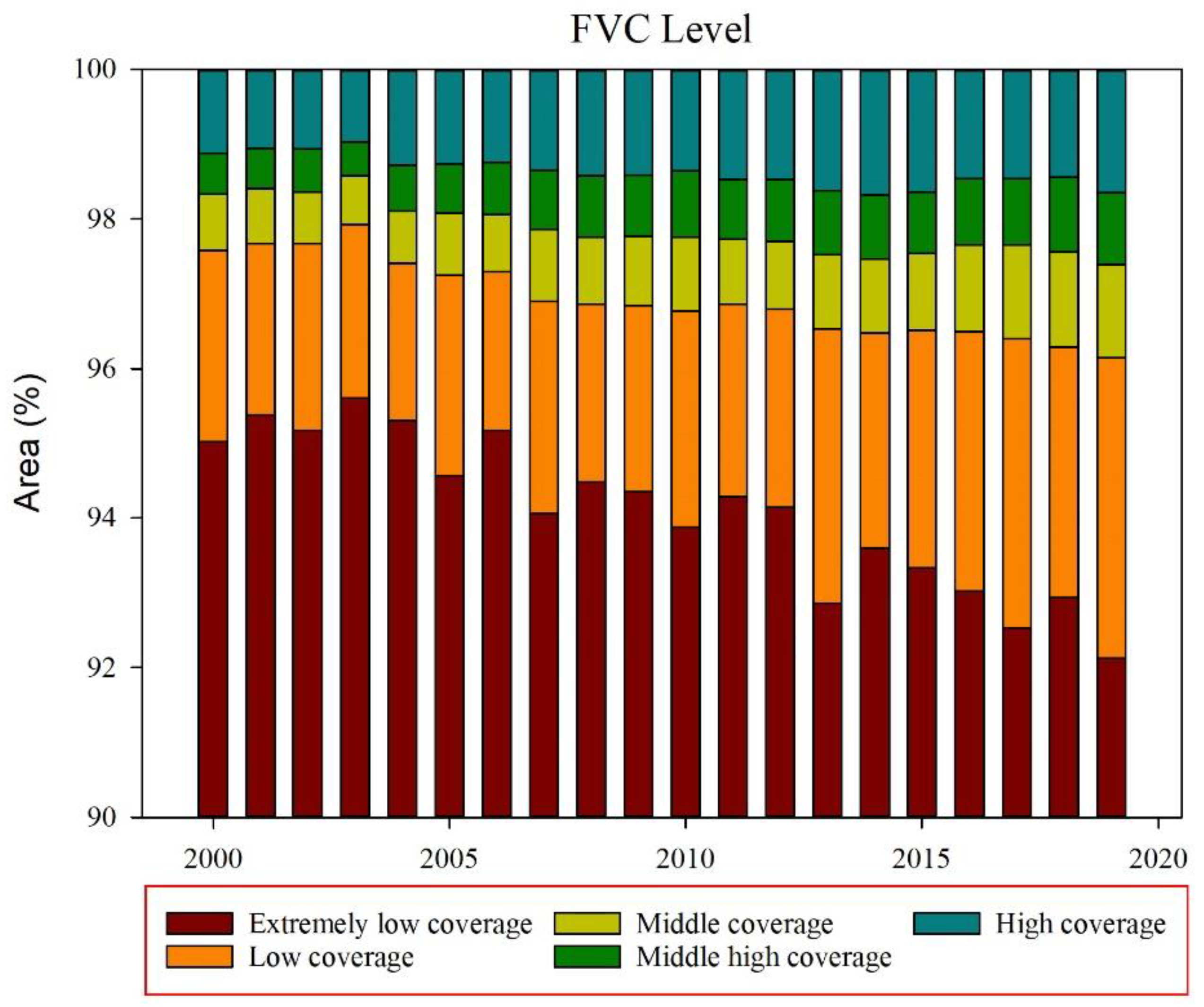

Figure 3 depicts how the FVC area proportions changed from 2000 to 2019. The proportion of extremely low vegetation cover [0–0.2] accounted for more than 92% and exhibited a decreasing trend.

In contrast, the area proportions of low [0.2–0.4], middle [0.4–0.6], middle-high [0.6–0.8], and high [0.8–1.0] vegetation coverage showed increasing trends, indicating an improvement in the ecological environment. Due to spatial heterogeneity, it is essential to analyze vegetation change patterns and their influencing factors.

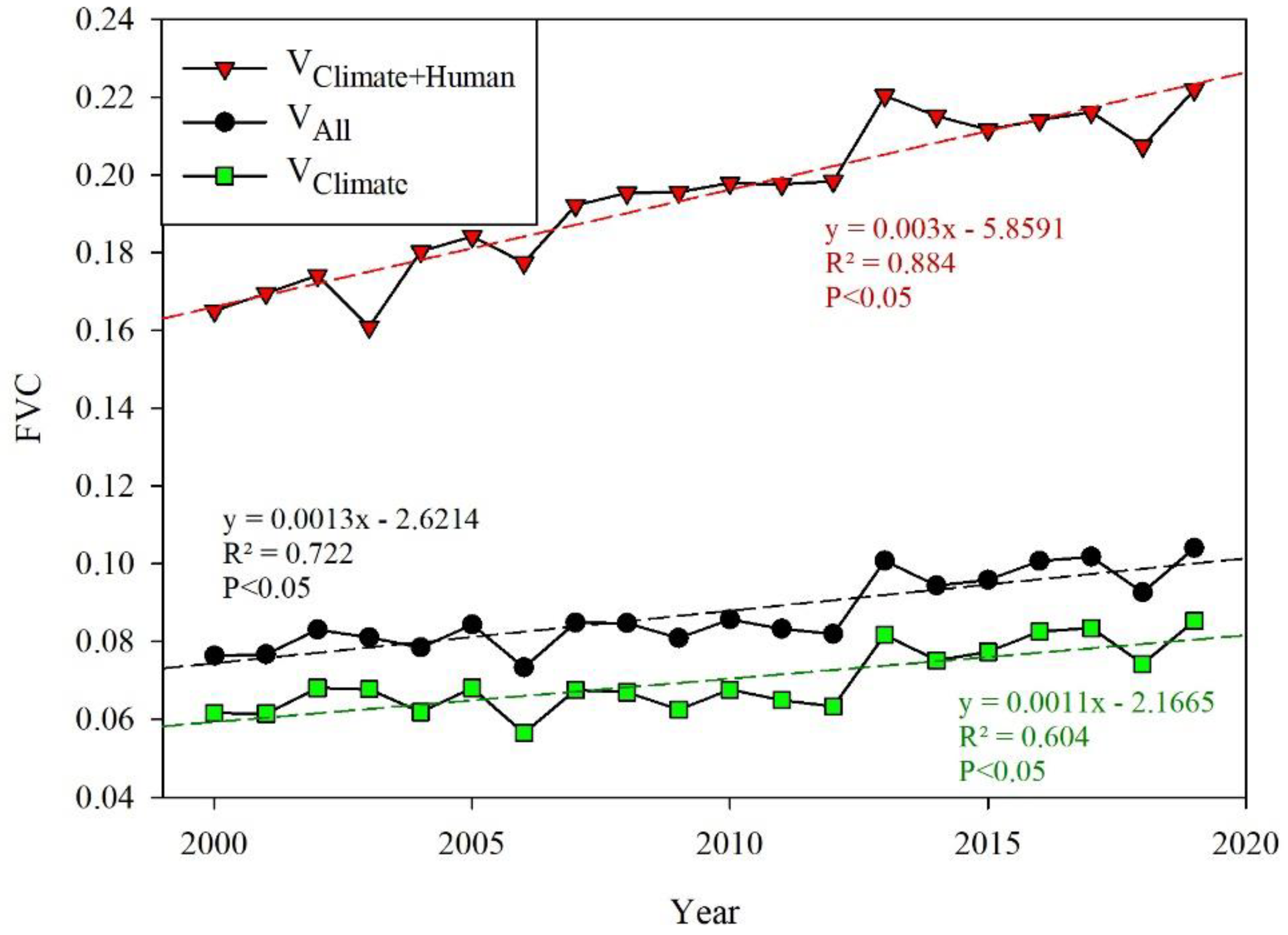

Roads fragment landscapes and trigger human colonization and degradation of ecosystems. [bisch,etal.[

65] defined the areas outside a 1-kilometer buffer around all roads as “roadless areas”. According to this definition, we divided the study area into “road areas” and “roadless areas”. In the road areas, changes in vegetation were affected by both human activities and climate factors. Conversely, in the roadless areas, where human activity was less prevalent, changes in vegetation were mainly influenced by natural climate change. We calculated the average FVC of the whole study area, the road areas, and the roadless areas, referred to as

VAll,

VClimate+Human, and

VClimate, respectively. The trend analysis results of

VAll,

VClimate+Human, and

VClimate showed a significant increasing trend (p < 0.05) from 2000 to 2019, with a linear trend of 1.3 × 10

−3 y

–1, 3 × 10

−3 y

–1 and 1.1 × 10

−3 y

–1 respectively (see

Figure 4).

In arid regions, roads are generally constructed around oases, while “roadless areas” are primarily located in desert regions. Therefore, the mean FVC of the “road areas” (

VClimate+Human) tends to be higher than that of the “roadless areas” (

VClimate). The dynamic changes of

VClimate and

VAll exhibit similar trends, while the dynamic changes of

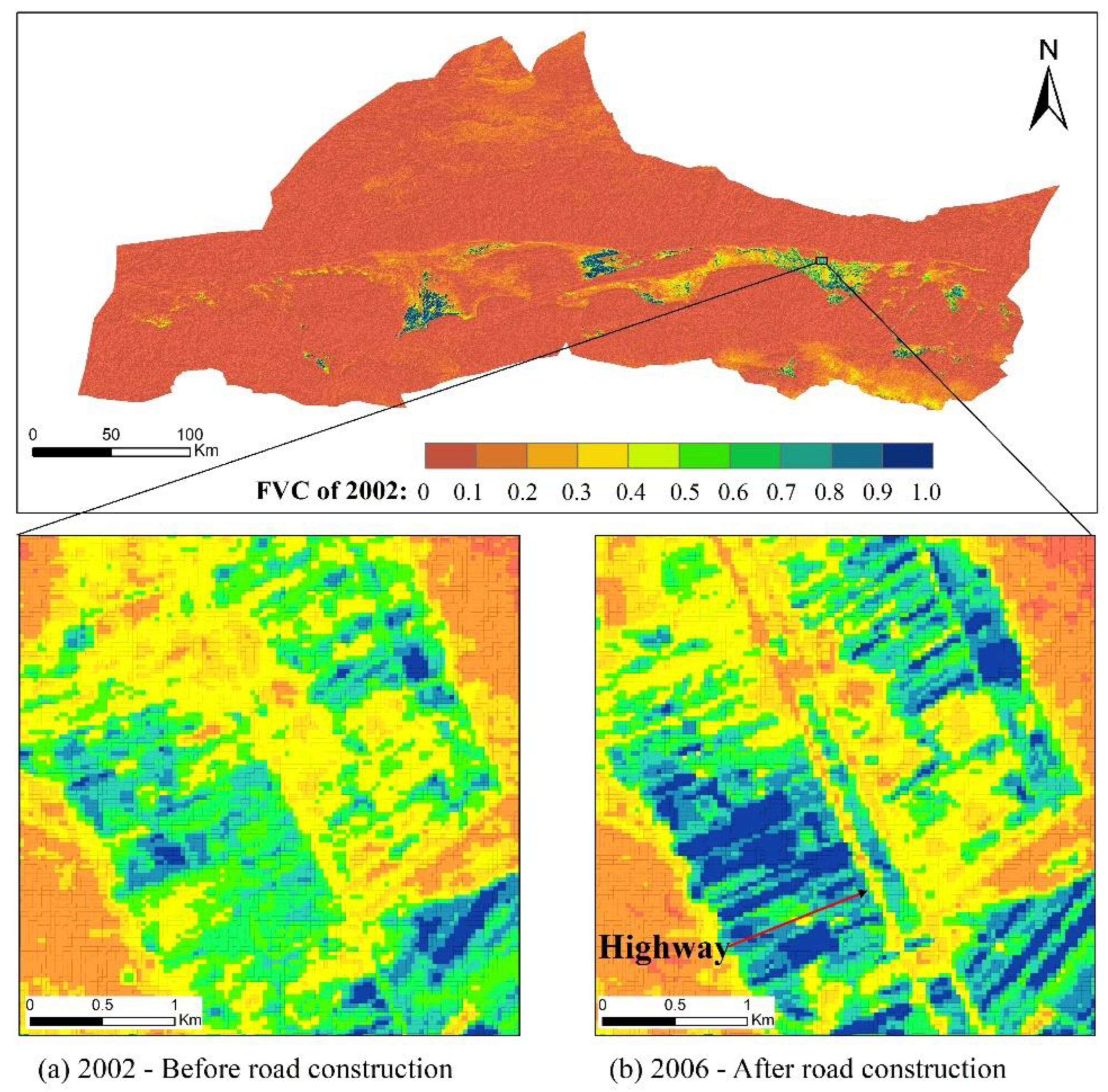

VClimate+Human significantly declined in 2003, primarily due to human activities. Upon investigation, we discovered the construction of the “Jia’an Highway” from 2004 to 2006 in the study area, which significantly impacted the dynamic changes of vegetation (

Figure 5).

To determine the extent of the impact of highway construction on vegetation, we divided the areas within a 1 km buffer around the “Jia’an Highway” into five regions with intervals of 200 meters (0-200 m, 200-400 m, 400-600 m, 600-800 m, 800-1000 m). The statistical time series changes of FVC mean values in these different regions are illustrated in

Figure 6. Before the construction of the highway (before 2004), the fluctuation trend of FVC in different intervals remained relatively consistent. However, once construction commenced (2004-2005), the FVC in the interval [0,200] meters experienced a significant drop, while the average FVC in other intervals either did not decrease or even increased slightly. Notably, in

Figure 4, the FVC in the roadless areas (

VClimate) during 2004-2005 exhibited an increasing trend, further indicating that the notable decrease in FVC in the interval [0,200] meters was influenced by road construction.

The FVC decreased in each interval from 2005 to 2006, and the FVC in the roadless areas (

VClimate) also showed a declining trend (

Figure 4), indicating that climate factors contributed to this decrease in FVC. However, it is noteworthy that the rate of decline in FVC within the interval of (200,1000] meters ranged from -0.010 year

-1 to -0.015 year

-1, which is slower than that in the [0,200] meter interval, where the slope was -0.021 year

-1.

The results suggest that climate factors primarily influence the FVC within the range of (200,1000] meters, while the FVC within the [0,200] meter range is affected by climate and road construction. Consequently, the FVC declines more rapidly in the [0,200] meter interval.

The FVC exhibit an increasing trend after the completion of the “Jia’an Highway” construction (2006). However, there are significant differences in FVC at different distances from the road. The FVC level in the [0,200] meter interval was significantly lower than in other intervals. These results illustrate how road construction alters vegetation landscape patterns.

3.2. Spatial Pattern of Vegetation Dynamics

Figure 7 depicts the trends of FVC in the entire SRB during the periods of 2000–2004, 2005–2009, 2010–2014, and 2015–2019. The findings are as follows:

(a) from 2000 to 2004, the area exhibiting a significant increase in FVC accounted for 0.20%, primarily concentrated in the western part of Dunhuang and the eastern part of Guazhou Oasis (

Table 1 and

Figure 7). The area experiencing a significant decrease in vegetation cover accounted for 0.29% and was mainly distributed in the Yumen oasis and the desert zone in the northern part of the SRB.

(b) In the period 2005-2009, the area witnessing a significant increase in vegetation cover expanded to 0.38%, predominantly observed in the oases of Dunhuang, Guazhou, and Yumen, as well as on both sides of the Shule River between the oases. Conversely, the area experiencing vegetation degradation accounted for 0.20% and was mainly distributed in the Qilian Mountains pre-mountainous zone southeast of the SRB.

(c) During 2010-2014, areas with a significant increase in vegetation cover expanded to 0.89%, while the proportion of regions witnessing a considerable decrease in vegetation cover accounted for 0.32% and was mainly concentrated in the oases in Dunhuang City.

(d) Finally, from 2015 to 2019, areas with a significant increase in vegetation cover extended to 0.68%, primarily concentrated in Dunhuang.

In summary, the dynamic changes in vegetation exhibit strong spatial variability. While vegetation generally shows a trend of improvement and increase in SRB, the areas of change vary across different time periods. Activities such as afforestation significantly increase FVC, whereas human activities like road construction significantly reduce FVC.

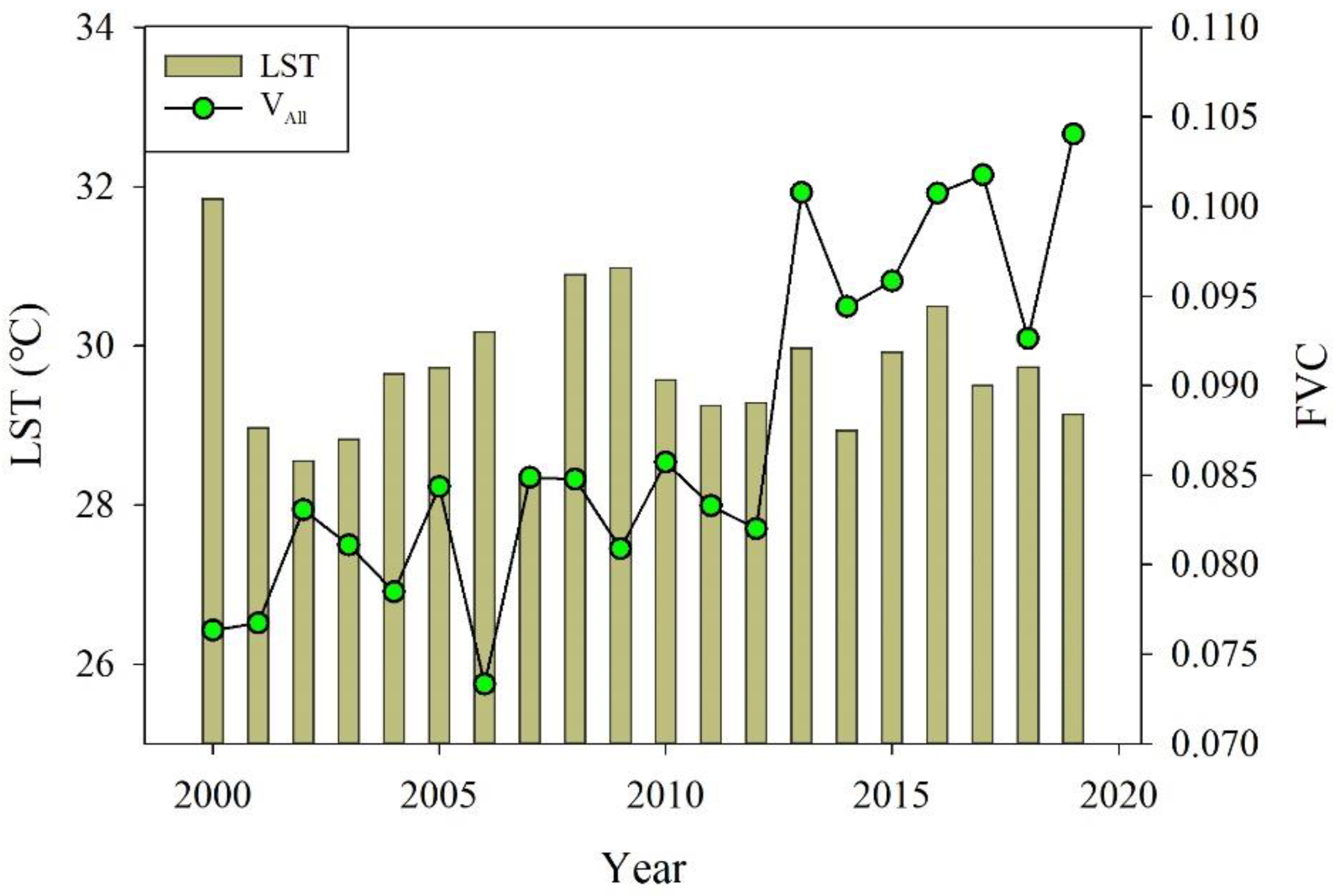

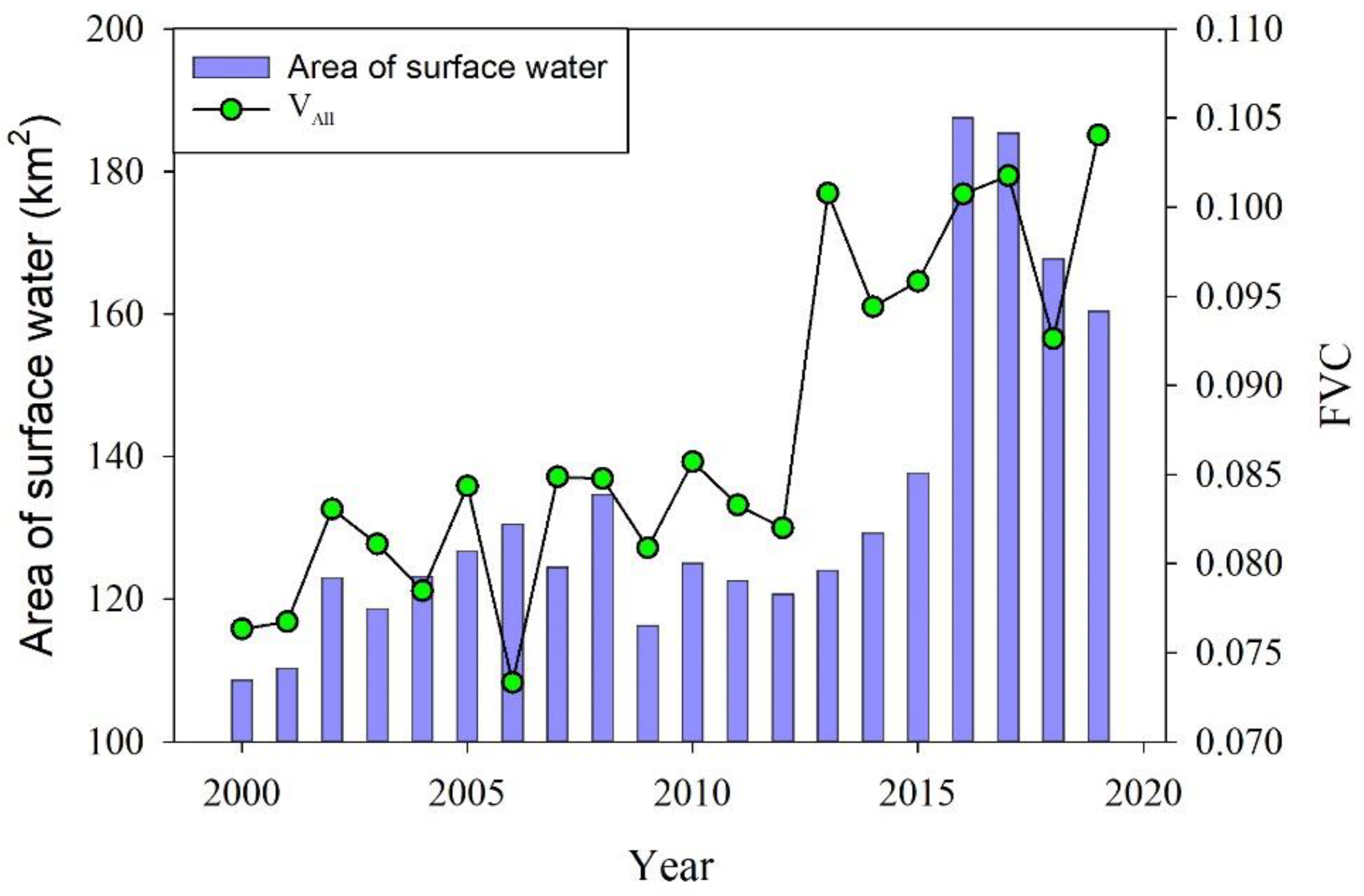

3.3. Correlations between Climate Factors and FVC

The succession process of surface vegetation coverage is influenced by climate change and human activities. We gathered and calculated time series data of total annual precipitation, the highest LST, and maximum surface water area to comprehend how environmental factors impact vegetation variation in the study area (

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure).

Annual total precipitation exhibits an increasing trend, while LST fluctuates with no apparent trend. Conversely, the surface water area significantly increases. FVC demonstrates a strong positive correlation with “precipitation” and “surface water area,” with correlation coefficients of “0.575” and “0.744,” respectively (

Table 1). “Precipitation” and “surface water area” also exhibit a positive relationship, with a correlation coefficient 0.548. These results suggest that precipitation promotes “surface waters” and vegetation growth, with higher humidity associated with better vegetation growth.

A weak negative correlation exists between FVC and LST, with correlation coefficients of “-0.107.” In arid and semiarid areas, water is crucial for vegetation growth; hence, elevated temperatures may lead to increased evaporation, reduced water supply, exacerbated drought stress, and vegetation degradation [

66]. Consequently, areas with higher LST exhibit poorer vegetation development.

In recent years, northern desertification areas have generally witnessed rising temperatures and increased precipitation, leading to extended plant growth periods and enhanced vegetation growth.

Figure 9.

The relationship between LST and FVC.

Figure 9.

The relationship between LST and FVC.

Figure 10.

The relationship between surface water area and FVC.

Figure 10.

The relationship between surface water area and FVC.

Table 2.

The correlations coefficient of precipitation, LST, area of surface water, and FVC (VAll).

Table 2.

The correlations coefficient of precipitation, LST, area of surface water, and FVC (VAll).

| |

VAll

|

Precipitation |

LST |

Area of surface water |

| VAll |

1 |

0.575 |

-0.107 |

0.744 |

| Precipitation |

0.575 |

1 |

-0.136 |

0.548 |

| LST |

-0.107 |

-0.136 |

0 |

0.030 |

| Area of surface water |

0.744 |

0.548 |

0.030 |

0 |

Figure 11 illustrates the spatial distribution of the partial correlation coefficient between FVC and climate factors. The partial correlation between FVC and precipitation shows the area of significant positive correlation (SPC) covering approximately 1.47% of the total area, primarily distributed in the middle of the SRB

Figure 11a,c. The area of SPC between FVC and LST is mainly concentrated in the eastern and middle regions of the SRB and covers 7.64% of the total area (

Figure 11b,d).

4. Discussion

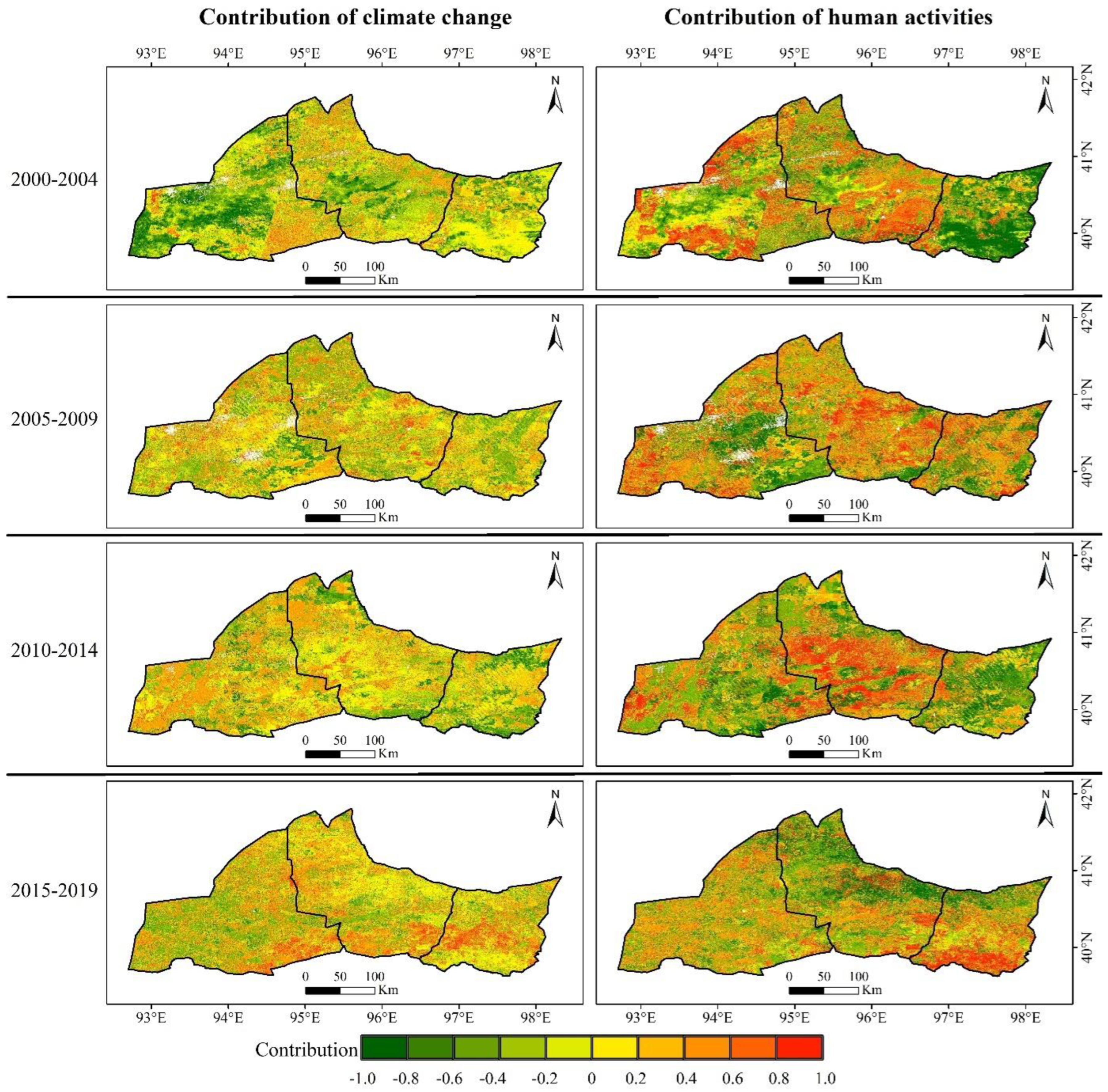

4.1. Contributions of Climate Change and Human Activities to Vegetation Dynamics

Quantifying the relative contributions of human activities and climate factors to vegetation dynamics is crucial for understanding and addressing climate change impacts [

66]. In this study, we quantified the spatiotemporal variations of FVC in the SRB from 2000 to 2019 and determined the contributions of climate change and human activities to vegetation dynamics.

Climate change, including factors like precipitation, temperature, and solar radiation, significantly influences vegetation dynamics in the SRB [

26,

27,

29,

67,

68]. Previous research has highlighted the importance of these climate factors in affecting vegetation productivity, with precipitation generally promoting vegetation growth in arid and semiarid regions. At the same time, higher temperatures can inhibit it [

35,

38,

69,

70]. However, the impact of climate factors on FVC exhibits spatial heterogeneity across the study area.

Figure 12 illustrates the relative contributions of climate change and human activities to the increasing trend of FVC in the SRB from 2000 to 2019. The area proportion of the contribution of climate change and human activities to FVC increase accounting for 17.47%, 25.48%, 28.31% and 30.81% during the periods of 2000–2004, 2005–2009, 2010–2014, and 2015–2019, respectively (

Table 3 This trend indicates the contributions of climate change to vegetation recovery is increasing. Conversely, the contribution of human activities to FVC was mainly concentrated in the middle part of the SRB, where agricultural areas are prevalent, reflecting the significant impact of human disturbances on vegetation growth in more populated regions.

These findings underscore the complex interplay between climate change and human activities in shaping vegetation dynamics. While climate change emerges as a primary driver of vegetation recovery, human activities dominate in densely populated areas, highlighting the need for targeted strategies to mitigate anthropogenic impacts on ecosystems while adapting to changing climatic conditions.

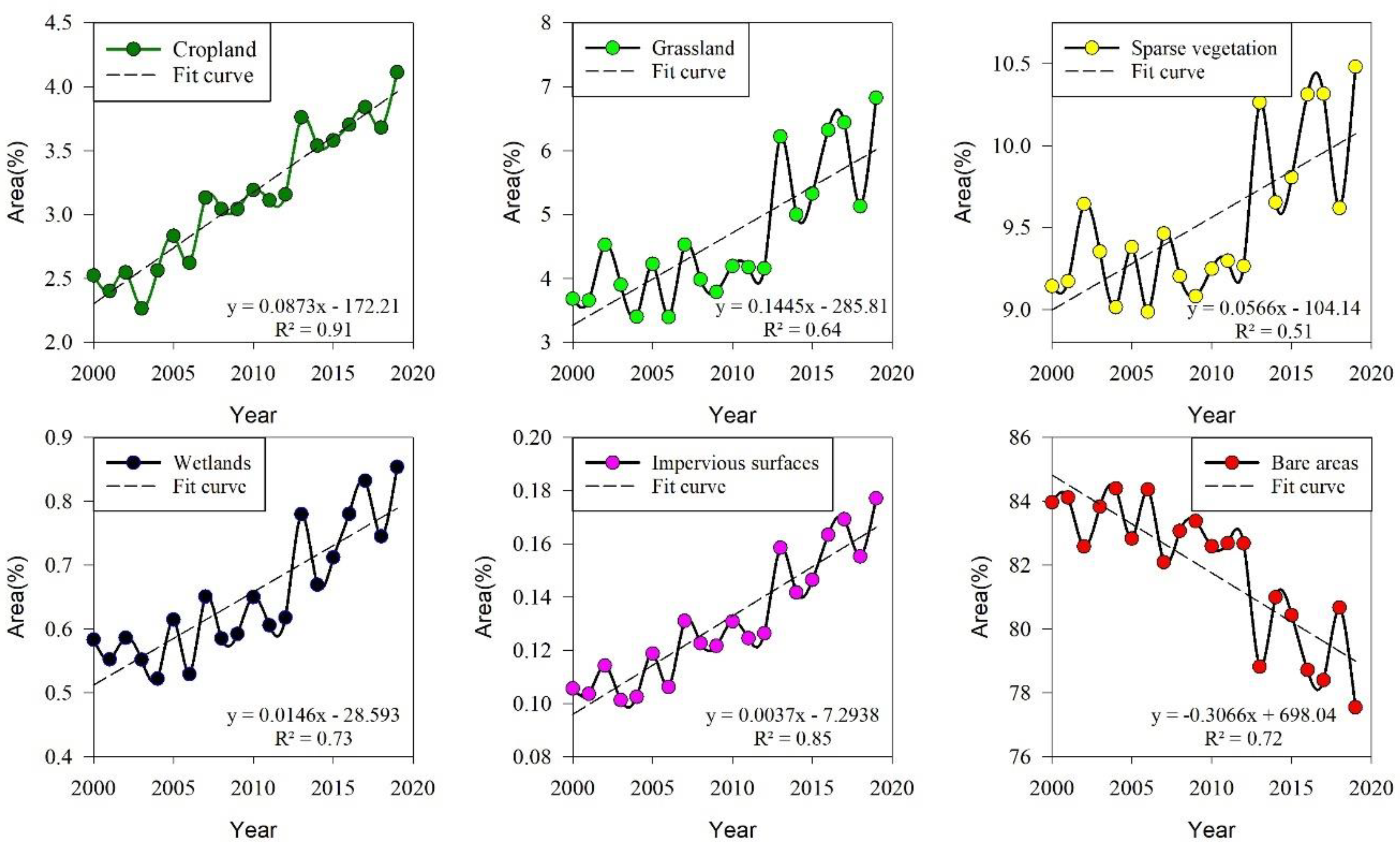

4.2. Land Cover Dynamics and Their Response to Climate Change and Human Activities

Understanding the dynamic changes in land cover types is essential for comprehending the environmental changes driven by human activities and climate change. Variations in meteorological conditions, topography, and soil moisture across different land cover types significantly influence vegetation dynamics [

69].

The relationship between FVC and land cover types, as summarized in

Table 4, underscores the complex interplay between vegetation dynamics and environmental factors. By analyzing the spatiotemporal changes in land cover types and their corresponding FVC proportions from 2000 to 2019, we can gain insights into the responses of different ecosystems to both human-induced and natural environmental changes [

71].

Figure 13 illustrates the trends in various land cover types over the study period, indicating shifts in agricultural practices, climate-induced alterations, and urbanization trends.

The observed increase in “Cropland” reflects the expansion of agricultural activities in the study area. Conversely, the growth of “Grassland,” “Sparse vegetation,” and “Wetlands” suggests responses to climate change, including warming and increased humidity. The rise in “Impervious surfaces” highlights ongoing urbanization and infrastructure development. Notably, the decline in “Bare areas” signifies changes from human activities and climate influences.

These findings emphasize the need for holistic approaches to land management and conservation that consider the interconnectedness of human activities, climate change impacts, and ecosystem responses. Such approaches are crucial for mitigating environmental degradation and promoting sustainable development in the study area.

Figure 13.

Time series of area proportions of different land cover types from 2000 to 2019 in the SRB.

Figure 13.

Time series of area proportions of different land cover types from 2000 to 2019 in the SRB.

5. Conclusions

This study provides comprehensive insights into vegetation dynamics in the SRB from 2000 to 2019, shedding light on the impacts of climate change and human activities on ecosystem dynamics. The main results were as follows:

(1) The study reveals a significant upward trend in regional average FVC within the SRB from 2000 to 2019, with an increase of 1.3 × 10−3 y–1. Notably, areas proximal to roads experienced a higher FVC increase of 3 × 10−3 y–1, while roadless areas experienced a comparatively lower increase of 1.1 × 10−3 y–1. Additionally, road construction activities during 2004-2006 led to a notable reduction in FVC within a 200-meter buffer of the roads.

(2) Spatial heterogeneity in FVC dynamics is pronounced within the SRB. While there is a general trend towards improvement and increase in vegetation cover, the magnitude and spatial distribution of these changes vary across different time periods and geographical locations. Afforestation initiatives emerge as significant contributors to FVC enhancement, whereas human activities such as road construction exert localized detrimental effects on vegetation health.

(3) Partial correlation analysis underscores the influence of climatic factors on FVC dynamics within the SRB. FVC demonstrates strong positive correlations with precipitation (correlation coefficient: 0.575) and surface water area (correlation coefficient: 0.744), indicating their pivotal roles in supporting vegetation growth. Conversely, a weak negative correlation is observed between FVC and LST (correlation coefficient: -0.107), suggesting differential responses of vegetation to LST variations.

(4) The study highlights the predominant influence of human activities over climate factors in shaping vegetation dynamics within the SRB. While climate change contributes significantly to vegetation recovery, human-induced alterations, particularly in land use and infrastructure development, exert a more substantial impact on FVC trends. Nonetheless, the increasing contributions of climate change to vegetation recovery underscore the evolving dynamics of ecological processes within the region.

In summary, the findings of this study provide crucial insights into the complex interactions between environmental factors and human activities, offering valuable information for ecosystem restoration and environmental management initiatives in the SRB.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Xiaorui He; Data curation, Linghuan Chai; Funding acquisition, Xiaorui He; Investigation, Xiaorui He and Linghuan Chai; Methodology, Xiaorui He; Project administration, Xiaorui He; Software, Luqing Zhang; Supervision, Luqing Zhang and Yuehan Lu; Validation, Xiaorui He; Visualization, Xiaorui He; Writing – original draft, Xiaorui He; Writing – review & editing, Xiaorui He, Luqing Zhang and Yuehan Lu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 42301098. Quzhou Science and Technology Plan program, grant number 2022K12, 2023K218.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lunetta, Ross S., Joseph F. Knight, Jayantha Ediriwickrema, John G. Lyon, and L. Dorsey Worthy. "Land-Cover Change Detection Using Multi-Temporal Modis Ndvi Data." Remote Sensing of Environment 105, no. 2 (2006): 142-54.

- Guan, Qingyu, Liqin Yang, Wenqian Guan, Feifei Wang, Zeyu Liu, and Chuanqi Xu. "Assessing Vegetation Response to Climatic Variations and Human Activities: Spatiotemporal Ndvi Variations in the Hexi Corridor and Surrounding Areas from 2000 to 2010." Theoretical and Applied Climatology 135, no. 3 (2019): 1179-93. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Hao, Guohua Liu, Zongshan Li, Pengtao Wang, and Zhuangzhuang Wang. "Comparative Assessment of Vegetation Dynamics under the Influence of Climate Change and Human Activities in Five Ecologically Vulnerable Regions of China from 2000 to 2015." Forests, no. 4 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Yaning, Zhi Li, Yuting Fan, Huaijun Wang, and Haijun Deng. "Progress and Prospects of Climate Change Impacts on Hydrology in the Arid Region of Northwest China." Environmental Research 139 (2015): 11-19. [CrossRef]

- Fokeng, Reeves M., and Zephania N. Fogwe. "Landsat Ndvi-Based Vegetation Degradation Dynamics and Its Response to Rainfall Variability and Anthropogenic Stressors in Southern Bui Plateau, Cameroon." Geosystems and Geoenvironment 1, no. 3 (2022): 100075. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Honglei, Xia Xu, Mengxi Guan, Lingfei Wang, Yongmei Huang, and Yuan Jiang. "Determining the Contributions of Climate Change and Human Activities to Vegetation Dynamics in Agro-Pastural Transitional Zone of Northern China from 2000 to 2015." Science of The Total Environment 718 (2020): 134871. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Yangyang, Zhaoying Zhang, Linjing Tong, Muhammad Khalifa, Qian Wang, Chengcheng Gang, Zhenqian Wang, Jianlong Li, and Zhengguo Sun. "Assessing the Effects of Climate Variation and Human Activities on Grassland Degradation and Restoration across the Globe." Ecological Indicators 106 (2019): 105504. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Bin, Zengyuan Li, Wentao Gao, Yuanyuan Zhang, Zhihai Gao, Zhangliang Song, Pengyao Qin, and Xin Tian. "Identification and Assessment of the Factors Driving Vegetation Degradation/Regeneration in Drylands Using Synthetic High Spatiotemporal Remote Sensing Data—a Case Study in Zhenglanqi, Inner Mongolia, China." Ecological Indicators 107 (2019): 105614. [CrossRef]

- Xue, Xu, Zhijie Wang, and Shuangshuang Hou. "Ndvi-Based Vegetation Dynamics and Response to Climate Changes and Human Activities in Guizhou Province, China." Forests, no. 4 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Gao, Wande, Ce Zheng, Xiuhua Liu, Yudong Lu, Yunfei Chen, Yan Wei, and Yandong Ma. "Ndvi-Based Vegetation Dynamics and Their Responses to Climate Change and Human Activities from 1982 to 2020: A Case Study in the Mu Us Sandy Land, China." Ecological Indicators 137 (2022): 108745. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Mingzhao, Shuai Song, Guizhen He, and Yajuan Shi. "Vegetation Landscape Changes and Driving Factors of Typical Karst Region in the Anthropocene." Remote Sensing, no. 21 (2022). [CrossRef]

- He, Juan, Xueyi Shi, and Yangjun Fu. "Identifying Vegetation Restoration Effectiveness and Driving Factors on Different Micro-Topographic Types of Hilly Loess Plateau: From the Perspective of Ecological Resilience." Journal of Environmental Management 289 (2021): 112562. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Xucai, and Xiaomei Jin. "Vegetation Dynamics and Responses to Climate Change and Anthropogenic Activities in the Three-River Headwaters Region, China." Ecological Indicators 131 (2021): 108223. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Ning, Yongxia Ding, and Shouzhang Peng. "Temporal Effects of Climate on Vegetation Trigger the Response Biases of Vegetation to Human Activities." Global Ecology and Conservation 31 (2021): e01822. [CrossRef]

- Teng, Mingjun, Lixiong Zeng, Wenjie Hu, Pengcheng Wang, Zhaogui Yan, Wei He, Yu Zhang, Zhilin Huang, and Wenfa Xiao. "The Impacts of Climate Changes and Human Activities on Net Primary Productivity Vary across an Ecotone Zone in Northwest China." Science of The Total Environment 714 (2020): 136691. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Sen, Paulo Pereira, Xiuqin Wu, Jinxing Zhou, Jianhua Cao, and Weixin Zhang. "Global Karst Vegetation Regime and Its Response to Climate Change and Human Activities." Ecological Indicators 113 (2020): 106208. [CrossRef]

- Yin, Le, Erfu Dai, Du Zheng, Yahui Wang, Liang Ma, and Miao Tong. "What Drives the Vegetation Dynamics in the Hengduan Mountain Region, Southwest China: Climate Change or Human Activity?" Ecological Indicators 112 (2020): 106013.

- Chen, Tao, Anming Bao, Guli Jiapaer, Hao Guo, Guoxiong Zheng, Liangliang Jiang, Cun Chang, and Latipa Tuerhanjiang. "Disentangling the Relative Impacts of Climate Change and Human Activities on Arid and Semiarid Grasslands in Central Asia During 1982–2015." Science of The Total Environment 653 (2019): 1311-25. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Meng, Ni Huang, Mingquan Wu, Jie Pei, Jian Wang, and Zheng Niu. "Vegetation Change in Response to Climate Factors and Human Activities on the Mongolian Plateau." PeerJ 7 (2019): e7735. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Qimin, Yinping Long, Xiaopeng Jia, Haibing Wang, and Yongshan Li. "Vegetation Response to Climatic Variation and Human Activities on the Ordos Plateau from 2000 to 2016." Environmental Earth Sciences 78, no. 24 (2019): 709. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Rui, Linlin Xiao, Zhe Liu, and Jicai Dai. "Quantifying the Relative Impacts of Climate and Human Activities on Vegetation Changes at the Regional Scale." Ecological Indicators 93 (2018): 91-99. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z. Y., Y. Wu, Z. Y., Y. Saito, D. N. Zhao, J. Q. Zhou, Z. Y. Cao, S. J. Li, J. H. Shang, and Y. Y. Liang. "Impact of Human Activities on Subaqueous Topographic Change in Lingding Bay of the Pearl River Estuary, China, During 1955-2013." Sci Rep 6 (2016): 37742.

- Zhang, Jing, JianMing Niu, Tongliga Bao, Alexander Buyantuyev, Qing Zhang, JianJun Dong, and XueFeng Zhang. "Human Induced Dryland Degradation in Ordos Plateau, China, Revealed by Multilevel Statistical Modeling of Normalized Difference Vegetation Index and Rainfall Time-Series." Journal of Arid Land 6, no. 2 (2014): 219-29. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Tao, Qiang Zhang, Weiguang Wang, Zhongbo Yu, Yongqin David Chen, Guihua Lu, Zhenchun Hao, Alexander Baron, Chenyi Zhao, Xi Chen, and Quanxi Shao. "Review of Advances in Hydrologic Science in China in the Last Decades: Impact Study of Climate Change and Human Activities." Journal of Hydrologic Engineering 18, no. 11 (2013): 1380-84. [CrossRef]

- Tu, Xinjun, Qiang Zhang, Vijay P. Singh, Xiaohong Chen, Chun-Ling Liu, and Shao-Bo Wang. "Space–Time Changes in Hydrological Processes in Response to Human Activities and Climatic Change in the South China." Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment 26, no. 6 (2011): 823-34. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Xi, Guoming Du, Haoting Bi, Zimou Li, and Xiaodie Zhang. "Normal Difference Vegetation Index Simulation and Driving Analysis of the Tibetan Plateau Based on Deep Learning Algorithms." Forests, no. 1 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Li, Guo, Jiye Liang, Shijie Wang, Mengxue Zhou, Yi Sun, Jiajia Wang, and Jinglong Fan. "Characteristics and Drivers of Vegetation Change in Xinjiang, 2000–2020." Forests, no. 2 (2024).

- Hou, Xiao, Bo Zhang, Jie Chen, Jing Zhou, Qian-Qian He, and Hui Yu. "Response of Vegetation Productivity to Greening and Drought in the Loess Plateau Based on Vis and Sif." Forests, no. 2 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Qianqian, Lei Gu, Yongqiang Liu, and Yongfu Zhang. "Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Normalized Difference Vegetation Index and Its Response to Climate Change in Xinjiang, 2000–2022." Forests, no. 2 (2024). [CrossRef]

- He, Qingyan, Qianhua Yang, Shouzheng Jiang, and Cun Zhan. "A Comprehensive Analysis of Vegetation Dynamics and Their Response to Climate Change in the Loess Plateau: Insight from Long-Term Kernel Normalized Difference Vegetation Index Data." Forests, no. 3 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Shi, Shangyu, Jingjie Yu, Fei Wang, Ping Wang, Yichi Zhang, and Kai Jin. "Quantitative Contributions of Climate Change and Human Activities to Vegetation Changes over Multiple Time Scales on the Loess Plateau." Science of The Total Environment 755 (2021): 142419. [CrossRef]

- Li, Binglun, Longchi Chen, Qingkui Wang, and Peng Wang. "Analysis of Linkage between Long-Term Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis and Vegetation Carbon Storage of Forests in Hunan, China." Forests, no. 3 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Araujo, Helder F. P., Nathália F. Canassa, Célia C. C. Machado, and Marcelo Tabarelli. "Human Disturbance Is the Major Driver of Vegetation Changes in the Caatinga Dry Forest Region." Scientific Reports 13, no. 1 (2023): 18440. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Bin, Zengxin Zhang, Jiaxi Tian, Rui Kong, and Xi Chen. "Increasing Negative Impacts of Climatic Change and Anthropogenic Activities on Vegetation Variation on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau During 1982–2019." Remote Sensing, no. 19 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xiaoxian, Xiuxia Zhang, Wangping Li, Xiaoqiang Cheng, Zhaoye Zhou, Yadong Liu, Xiaodong Wu, Junming Hao, Qing Ling, Lingzhi Deng, Xilai Zhang, and Xiao Ling. "Quantitative Analysis of Climate Variability and Human Activities on Vegetation Variations in the Qilian Mountain National Nature Reserve from 1986 to 2021." Forests, no. 10 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Ma, Shuai, Liang-Jie Wang, Jiang Jiang, Lei Chu, and Jin-Chi Zhang. "Threshold Effect of Ecosystem Services in Response to Climate Change and Vegetation Coverage Change in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Ecological Shelter." Journal of Cleaner Production 318 (2021): 128592. [CrossRef]

- Luo, D. L., H. Luo, D. L., H. J. Jin, and V. F. Bense. "Ground Surface Temperature and the Detection of Permafrost in the Rugged Topography on Ne Qinghai-Tibet Plateau." Geoderma 333 (2019): 57-68. [CrossRef]

- Aizizi, Yimuranzi, Alimujiang Kasimu, Hongwu Liang, Xueling Zhang, Bohao Wei, Yongyu Zhao, and Maidina Ainiwaer. "Evaluation of Ecological Quality Status and Changing Trend in Arid Land Based on the Remote Sensing Ecological Index: A Case Study in Xinjiang, China." Forests, no. 9 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Li, Shuangshuang, Junping Yan, Xinyan Liu, and Jia Wan. "Response of Vegetation Restoration to Climate Change and Human Activities in Shaanxi-Gansu-Ningxia Region." Journal of Geographical Sciences 23, no. 1 (2013): 98-112. [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, Tomohiro, Ali Kharrazi, Jia Li, and Ram Avtar. "Agricultural Water Policy Reforms in China: A Representative Look at Zhangye City, Gansu Province, China." Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 190, no. 1 (2017): 9.

- Zhang, Hao, Zhilin He, Junkui Xu, Weichen Mu, Yanglong Chen, and Guangxia Wang. "Analysis of Spatial and Temporal Changes in Vegetation Cover and Driving Forces in the Wuding River Basin, Loess Plateau." Forests, no. 1 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Liu, Chenxi, Xiaodong Zhang, Tong Wang, Guanzhou Chen, Kun Zhu, Qing Wang, and Jing Wang. "Detection of Vegetation Coverage Changes in the Yellow River Basin from 2003 to 2020." Ecological Indicators 138 (2022): 108818. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Libang, Jie Bo, Xiaoyang Li, Fang Fang, and Wenjuan Cheng. "Identifying Key Landscape Pattern Indices Influencing the Ecological Security of Inland River Basin: The Middle and Lower Reaches of Shule River Basin as an Example." Science of The Total Environment 674 (2019): 424-38. [CrossRef]

- Funk, Chris, Pete Peterson, Martin Landsfeld, Diego Pedreros, James Verdin, Shraddhanand Shukla, Gregory Husak, James Rowland, Laura Harrison, Andrew Hoell, and Joel Michaelsen. "The Climate Hazards Infrared Precipitation with Stations—a New Environmental Record for Monitoring Extremes." Scientific Data 2, no. 1 (2015): 150066.

- Ermida, Sofia L., Patrícia Soares, Vasco Mantas, Frank- M. Göttsche, and Isabel F. Trigo. "Google Earth Engine Open-Source Code for Land Surface Temperature Estimation from the Landsat Series." Remote Sensing, no. 9 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Luo, D. L., H. Luo, D. L., H. J. Jin, Q. B. Wu, V. F. Bense, R. X. He, Q. Ma, S. H. Gao, X. Y. Jin, and L. Z. Lu. "Thermal Regime of Warm-Dry Permafrost in Relation to Ground Surface Temperature in the Source Areas of the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, Sw China." Science of The Total Environment 618 (2018): 1033-45. [CrossRef]

- Pekel, Jean-François, Andrew Cottam, Noel Gorelick, and Alan S. Belward. "High-Resolution Mapping of Global Surface Water and Its Long-Term Changes." Nature 540, no. 7633 (2016): 418-22. [CrossRef]

- Xia, C., G. Xia, C., G. Liu, J. Zhou, Y. Meng, K. Chen, P. Gu, M. Yang, X. Huang, and J. Mei. "Revealing the Impact of Water Conservancy Projects and Urbanization on Hydrological Cycle Based on the Distribution of Hydrogen and Oxygen Isotopes in Water." Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 28, no. 30 (2021): 40160-77. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Weijia, Quan Quan, Bohua Wu, and Shuhong Mo. "Response of Vegetation Dynamics in the Three-North Region of China to Climate and Human Activities from 1982 to 2018." Sustainability, no. 4 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Carlson, Toby N., and David A. Ripley. "On the Relation between Ndvi, Fractional Vegetation Cover, and Leaf Area Index." Remote Sensing of Environment 62, no. 3 (1997): 241-52.

- Wang, Yongfang, Jiquan Zhang, Siqin Tong, and Enliang Guo. "Monitoring the Trends of Aeolian Desertified Lands Based on Time-Series Remote Sensing Data in the Horqin Sandy Land, China." CATENA 157 (2017): 286-98. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Xiaojuan, Huiyu Liu, Fusheng Jiao, Haibo Gong, and Zhenshan Lin. "Time-Varying Trends of Vegetation Change and Their Driving Forces During 1981–2016 Along the Silk Road Economic Belt." CATENA 195 (2020): 104796. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Ying, Chaobin Zhang, Zhaoqi Wang, Yizhao Chen, Chengcheng Gang, Ru An, and Jianlong Li. "Vegetation Dynamics and Its Driving Forces from Climate Change and Human Activities in the Three-River Source Region, China from 1982 to 2012." Science of The Total Environment 563-564 (2016): 210-20.

- Zhang, Daojun, Wenyan Ge, and Yu Zhang. "Evaluating the Vegetation Restoration Sustainability of Ecological Projects: A Case Study of Wuqi County in China." Journal of Cleaner Production 264 (2020): 121751. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Wenjuan, Jiangbo Gao, Shaohong Wu, and Erfu Dai. "Interannual Variations in Growing-Season Ndvi and Its Correlation with Climate Variables in the Southwestern Karst Region of China." Remote Sensing, no. 9 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Yin, Lichang, Xiaofeng Wang, Xiaoming Feng, Bojie Fu, and Yongzhe Chen. "A Comparison of Ssebop-Model-Based Evapotranspiration with Eight Evapotranspiration Products in the Yellow River Basin, China." Remote Sensing 12, no. 16 (2020): 2528. [CrossRef]

- Yin, Lichang, Xiaoming Feng, Bojie Fu, Yongzhe Chen, Xiaofeng Wang, and Fulu Tao. "Irrigation Water Consumption of Irrigated Cropland and Its Dominant Factor in China from 1982 to 2015." Advances in Water Resources 143 (2020): 103661. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Shaokang, Ji Liu, Chenghao Wang, Te Zhang, Xiaohua Dong, and Yanli Liu. "Vegetation Dynamics Influenced by Climate Change and Human Activities in the Hanjiang River Basin, Central China." Ecological Indicators 145 (2022): 109586. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Yingying, Weiyan Wang, Shikuan Jin, Haoxin Li, Boming Liu, Wei Gong, Ruonan Fan, and Hui Li. "Spatiotemporal Variation of Lai in Different Vegetation Types and Its Response to Climate Change in China from 2001 to 2020." Ecological Indicators 156 (2023): 111101. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Weijia, Quan Quan, Bohua Wu, and Shuhong Mo. "Response of Vegetation Dynamics in the Three-North Region of China to Climate and Human Activities from 1982 to 2018." Sustainability, no. 4 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Nan, Yunyan Du, Fuyuan Liang, Huimeng Wang, and Jiawei Yi. "The Spatiotemporal Response of China's Vegetation Greenness to Human Socio-Economic Activities." Journal of Environmental Management 305 (2022): 114304.

- Gu, Yangyang, Bo Pang, Xuning Qiao, Delin Xu, Wenjing Li, Yan Yan, Huashan Dou, Wen Ao, Wenlin Wang, Changxin Zou, Xiaofei Zhang, and Bingshuai Cao. "Vegetation Dynamics in Response to Climate Change and Human Activities in the Hulun Lake Basin from 1981 to 2019." Ecological Indicators 136 (2022): 108700. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Jian, Hong Jiang, Qinghua Liu, Sophie M. Green, Timothy A. Quine, Hongyan Liu, Sijing Qiu, Yanxu Liu, and Jeroen Meersmans. "Human Activity Vs. Climate Change: Distinguishing Dominant Drivers on Lai Dynamics in Karst Region of Southwest China." Science of The Total Environment 769 (2021): 144297. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Mingzhao, Shuai Song, Guizhen He, and Yajuan Shi. "Vegetation Landscape Changes and Driving Factors of Typical Karst Region in the Anthropocene." Remote Sensing, no. 21 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Ibisch, Pierre L., Monika T. Hoffmann, Stefan Kreft, Guy Pe’er, Vassiliki Kati, Lisa Biber-Freudenberger, Dominick A. DellaSala, Mariana M. Vale, Peter R. Hobson, and Nuria Selva. "A Global Map of Roadless Areas and Their Conservation Status." Science 354, no. 6318 (2016): 1423-27. [CrossRef]

- Ge, Wenyan, Liqiang Deng, Fei Wang, and Jianqiao Han. "Quantifying the Contributions of Human Activities and Climate Change to Vegetation Net Primary Productivity Dynamics in China from 2001 to 2016." Science of The Total Environment 773 (2021): 145648. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Xin, Tiesheng Guan, Jianyun Zhang, Yanli Liu, Junliang Jin, Cuishan Liu, Guoqing Wang, and Zhenxin Bao. "Identifying and Predicting the Responses of Multi-Altitude Vegetation to Climate Change in the Alpine Zone." Forests, no. 2 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Ma, Menglu, Hao Zhang, Jushuang Qin, Yutian Liu, Baoguo Wu, and Xiaohui Su. "Analysis of Factors Driving Subtropical Forest Phenology Differentiation, Considering Temperature and Precipitation Time-Lag Effects: A Case Study of Fujian Province." Forests, no. 2 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Lin, Nan, Jiaxuan Li, Ranzhe Jiang, Xin Li, and Shu Liu. "Quantifying the Spatiotemporal Variation of Npp of Different Land Cover Types and the Contribution of Its Associated Factors in the Songnen Plain." Forests, no. 9 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Lai, Jinlin, Tianheng Zhao, and Shi Qi. "Spatiotemporal Variation in Vegetation and Its Driving Mechanisms in the Southwest Alpine Canyon Area of China." Forests, no. 12 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Liu, Liangyun, Xiao Zhang, Yuan Gao, Xidong Chen, Xie Shuai, and Jun Mi. "Finer-Resolution Mapping of Global Land Cover: Recent Developments, Consistency Analysis, and Prospects." Journal of Remote Sensing 2021 (2021).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).