1. Introduction

Security is a crucial concern in computer systems, as it aims to safeguard confidential data from the ever-changing landscape of cyber attacks. The conventional encryption methods, which depend on intricate mathematical issues that pose challenges for classical computers to answer, effectively fulfill their purpose of safeguarding sensitive data from malevolent entities. Quantum computers, which rely on the principles of quantum physics, can disrupt the equilibrium between defenders and attackers by significantly accelerating some calculations. By implementing Shor’s algorithm [

1] and Grover’s algorithm [

2] on quantum computers, standard public key cryptography (PKC) systems such as RSA [

3] and elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) [

4] can be vulnerable. Therefore, replacing them with post-quantum cryptography (PQC) is necessary. CRYSTALS-Kyber is a cryptographic algorithm commonly referred to as Kyber. It is documented in the source [

5]. The designation of Kyber as a post-quantum key encapsulation mechanism (KEM) protocol is due to its classification within the family of lattice-based cryptography (LBC). The fundamental challenge that Kyber addresses is module learning with errors (M-LWE). Kyber is a cryptographic system built on lattices and relies on the M-LWE problem. Kyber’s security is based on the premise that addressing LWE problems is challenging, even for quantum computers. The hardness of the material contributes to its resistance to quantum cryptanalysis. Generally, systems based on the M-LWE offer enhanced security [

6] and improved performance compared to LWE schemes [

7]. In this method, polynomials are typically defined over the ring

, with the value

n indicating the size of the public key matrix and the security levels. Kyber provides three sets of parameters: Kyber-512, Kyber-768, and Kyber-1024. These factors define the dimensions of the mathematical entities employed and impact the algorithm’s security and efficiency level. The Kyber-768 algorithm provides an optimal equilibrium between robustness and effectiveness.

Performing polynomial multiplication within the ring is an expensive calculation, both in terms of hardware and software implementation. This holds true not only for the Kyber cryptography algorithm but also for other cryptographic algorithms. Polynomial multiplication can be computed using several algorithms, including the schoolbook algorithm [

8,

9,

10], Karatsuba algorithm [

11,

12], Toom-Cook algorithm [

13,

14], and NTT algorithm [

15,

16,

17]. Out of these algorithms, the schoolbook algorithm is the most basic and straightforward. However, it has a quadratic complexity of

, where

n represents the length of the polynomials. The Karatsuba algorithm employs the "divide-and-conquer" approach by splitting the original polynomial into two sections, resulting in a computational complexity of

. The Toom-Cook algorithm is an extension of the Karatsuba algorithm. The Toom-Cook algorithm differs from the Karatsuba algorithm by dividing the original polynomial into

k parts. This division results in a complexity of

, where

. The Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) can be employed for polynomial multiplication. However, the computational complexity of directly computing the DFT is

, which is comparable to that of the schoolbook technique.

Over the past few decades, numerous efficient algorithms for calculating the discrete Fourier transform (DFT) have been introduced, which are currently referred to as the fast Fourier transform (FFT). The concept of FFT was initially formulated by Carl Friedrich Gauss in his unpublished manuscript in 1805 [

18]. The FFT gained significant recognition in 1965 when Cooley and Tukey independently introduced the Cooley-Tukey method, a rapid technique for the DFT. The Number Theoretic Transform (NTT) is a specific instance of the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) that operates on a finite field [

19]. Similarly, the majority of Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) approaches can be utilized for Number Theoretic Transform (NTT), leading to the development of efficient algorithms for number theoretic transformations. From an implementation perspective, the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) and Number Theoretic Transform (NTT) are the most efficient techniques for calculating polynomial multiplication of large degrees. This is because they have a quasilinear complexity of

, which gives them a major advantage over other multiplication algorithms. However, due to the fact that the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) is carried out in the complex domain, the floating point operations involved in the computation may introduce inaccuracies in rounding precision when multiplying two polynomials with integer coefficients. Conversely, the calculations involved in NTT computing exclusively utilize integers, so circumventing any potential precision issues.

Most polynomials used in lattice-based schemes are created using integer coefficients. It is evident that the Number Theoretic Transform (NTT) is particularly well-suited for implementing these schemes. Most schemes that utilize lattices with algebraic structures tend to favor NTT-based multiplication because of its numerous benefits, in addition to its quasilinear complexity and utilization of integer arithmetic. Nevertheless, certain lattice-based techniques are unable to utilize NTT directly due to the parameter requirements imposed by NTT. NTT, which stands for Number Theoretic Transform, utilizes negative wrapped convolution (NWC). The current settings of Kyber, which is the sole Key Encapsulation Mechanism (KEM) specified by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), only partially satisfy the condition , therefore preventing the full utilization of the Number Theoretic Transform (NTT) based on the Number Theoretic Cryptography (NWC) approach.

The process of encrypting and decrypting in Crystal-Kyber is significantly dependent on performing polynomial multiplication within a certain mathematical ring. In order to address these problems, Kyber employs NTT (Number Theoretic Transform) to carry out a crucial operation with optimal efficiency. NTT functions as an optimization tool. It converts polynomials from their standard form into an alternative representation that allows for significantly faster multiplication. Using NTT greatly enhances the velocity and effectiveness of polynomial multiplication in Crystal-Kyber. This results in accelerated key generation, encapsulation, and decapsulation procedures. The term "Improve NTT" is used to enhance the overall performance of the CRYSTALS Kyber PQC Scheme. In this study, we introduce a new NTT architecture to expedite the polynomial matrix-vector multiplication in Kyber. The supplied accelerator achieves reduced latency and resource consumption compared to current works on the same platform.

2. Related Work

The first challenge of implementing iterative FFT or NTT, the Cooley-Tukey FFT algorithm [

20] to be specific, is handling bit-reversed order preprocessing efficiently, which has a non-negligible impact on performance. Some studies, such as [

21], address this problem by using a ping-pong memory access scheme between two BRAMs and were able to achieve

faster and at least

smaller ATP than the state-of-the-art. Another more recent work [

22], on the other hand, approaches the problem by arranging the coefficients into 3 FIFOs and is also able to achieve a BRAM-free NTT architecture. However, since the final goal of these transforms is to merely perform polynomial multiplication, there are some tricks that we can exploit. The reference implementation of CRYSTALS Kyber [

5], which is implemented in software, suggests that we directly perform the Cooley-Tukey on natural order in the forward pass, getting the result in bit-reversed order and performing pointwise multiplication in that order and finally performing Gentleman-Sande in the inverse to get the multiplication result in natural order.

The second challenge of implementing NTT is the butterfly unit, or handling modular multiplication or modular reduction of the product between a coefficient and the root of unity efficiently. The reference implementation [

5] suggests that we replace all modular multiplications with Montgomery Multiplication, basically performing all operations in an intermediate, reduction-friendly form and performing post-processing in the end to get the result in standard form. On the other hand, the work [

23] suggests a K-RED algorithm that can perform modular reduction efficiently and is optimized by [

22] on their work along with the 3 FIFOs strategy to achieve 16.7% higher hardware efficiency than the state-of-the-art. Moreover, the work [

24] proposed

, which is based on K-RED and achieves better hardware resource utilization.

In general, all works so far mainly focus on finding the optimal data access pattern of the iterative FFT and optimizing modular reduction on the butterfly unit to make the whole NTT core faster and/or more compact. In this paper, we will propose a high frequency, fully pipelined butterfly unit NTT accelerator architecture for CRYSTALS Kyber version 3, with the parameter of and , for the FPGA platform, to achieve a lower latency in the critical exchange process which these operations belong to. The key contributions in this work can be summarized as:

- 1.

We proposed a new data accessing pattern on the NTT algorithm as well as appropriate reordering in order to reduce the BRAM to just LUTRAM of the FPGA Architecture, which can support shallow-depth and long-width requirements for unrolling.

- 2.

We also propose two novel butterfly units that are DSPs-free and have low resource utilization. The most expensive operation of the butterfly unit in NTT, in terms of resources and time, is the modular multiplication of the coefficient with the root of unities. The first approach we propose utilizes the fact that with parameter , which means the coefficient is up to long, we can split it to sum of multiples precomputed product with the roots of unity and can eliminate the full multiplication and as well as the need for dedicated storage for the root of unities completely.

- 3.

The second butterfly unit we propose will utilize the quarter square multiplication to perform modular multiplication , by realizing the fact that although a multiplication typically requires a depth look-up table while a squares only requires . Therefore, by replacing multiplication by squares with additional processing, we can fit the quarter squares on a single dual-port ROM that fits neatly on one BRAM. This approach also avoids the need for the full product to be computed and reduced.

- 4.

We propose a detailed pipelined butterfly unit based on the proposed approach with a short critical path and thus can operate at a higher frequency.

- 5.

And finally, we synthesize PnR and verify the functionality on an Xilinx Artix-7 FPGA, which can run at up to 446MHz.

3. Background Knowledge

Fast Fourier Transform traditionally operates on the vector of complex numbers and can be utilized to perform fast convolution with sub-quadratic time complexity. Fortunately, the same algorithm can be applied on -degree polynomial with coefficients in any finite field with n-th root of unity to achieve fast multiplication. The variant of the Fast Fourier Transform, which operates on the finite field, is called the Number Theoretic Transform.

For CRYSTALS-Kyber version 2 and later, the parameter happens to be and , and the polynomial is operated on the ring . However, since the only have up to 256-th primitive root of unity, namely , an NTT-based multiplication can only give us the result modulo . Therefore the modulus is first being factored as and the 256 coefficients polynomial is being transformed to a vector of 128 degree-1 polynomial modulo . The pointwise multiplication process now becomes the "degree-1-wise" multiplication.

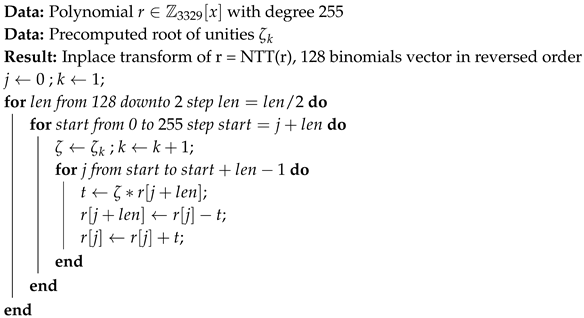

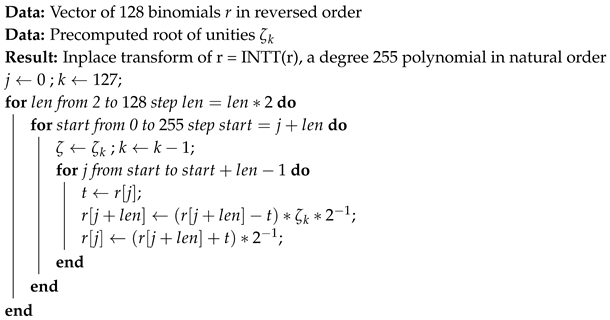

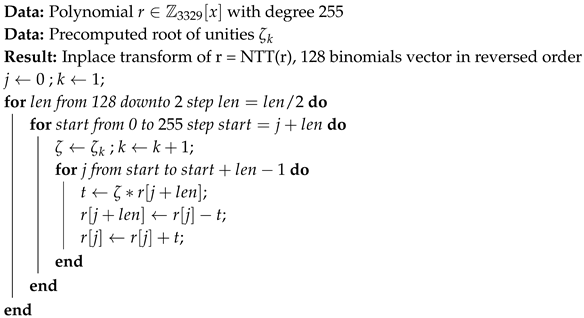

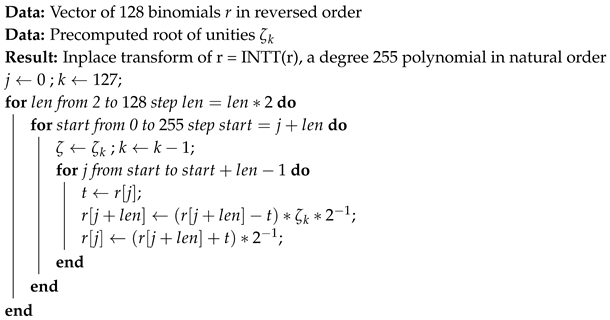

Furthermore, the traditional iterative FFT algorithm (Cooley-Tukey) requires bit-reversal preprocessing on both forward and inverse transform; this introduces non-negligible impacts on hardware utilization and performance. Therefore, in the reference implementation of CRYSTALS Kyber, the forward transform (NTT) is performed using the Cooley-Tukey algorithm and outputs the result in reverse order, which then is used to perform pointwise multiplication in the same reversed order, and finally using the Gentleman-Sande algorithm, which takes in reversed order vector, and output the final result in natural order, as expected. Both the forward and inverse NTT algorithms is described as Algorithm 1 and Algorithm 2, respectively.

|

Algorithm 1: Cooley-Tukey forward NTT. |

|

|

Algorithm 2: Gentleman-Sande inverse NTT. |

|

4. Proposed NTT Architecture

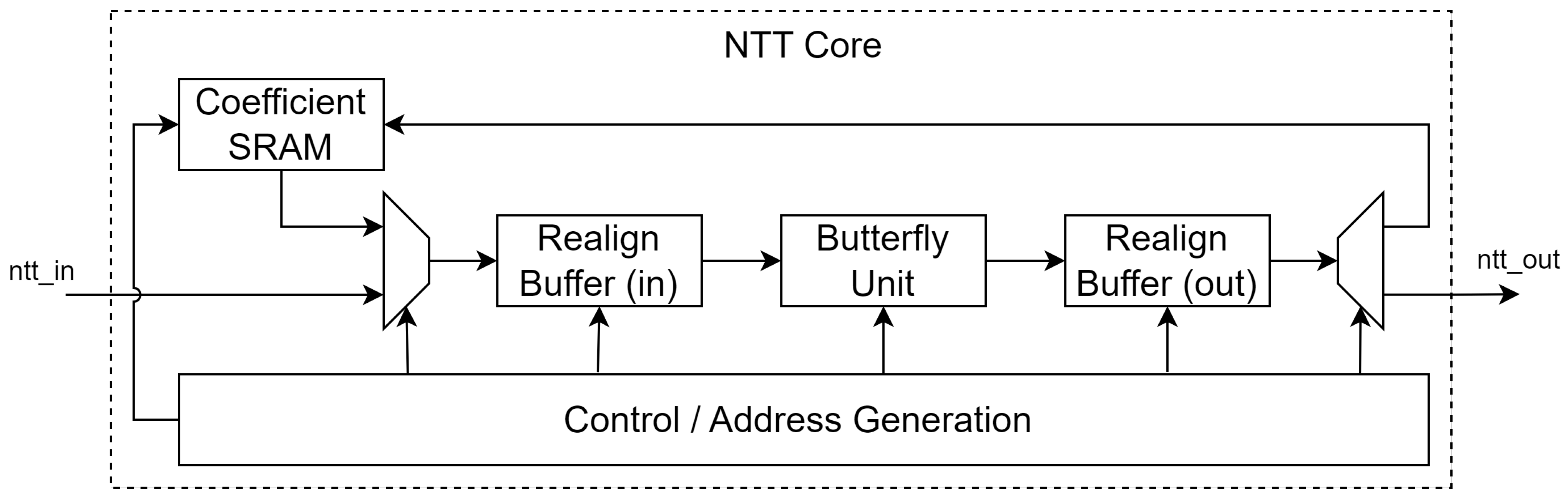

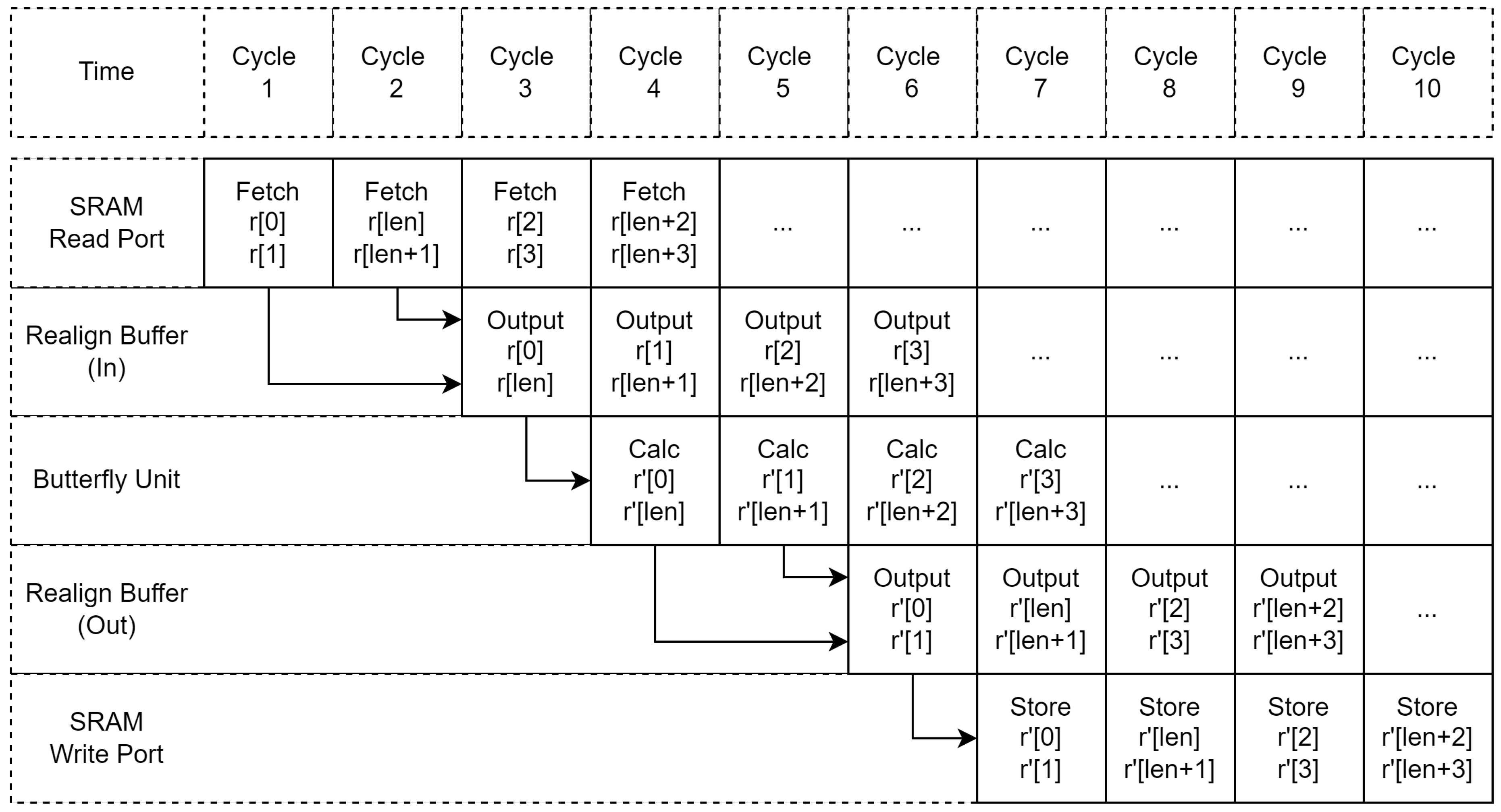

The proposed NTT core design performs a Number-theoretic transform with parameters (CRYSTALS Kyber Version 3). Thus, each polynomial being transformed is a vector of 256 12-bit numbers. To improve the throughput, the core utilizes a single semi-dual-port SRAM with a depth of 64 and a width of 48-bit; each entry stores four 12-bit polynomial coefficients to perform operations on two pairs of coefficients at a time.

On Xilinx 7-series FPGA, this SRAM is inferred to multiple instances of LUTRAM, and this design requires no BRAM usage on the device. Since the butterfly operation requires fetching coefficient in a non-linear manner, a special access pattern from the Control / Address generation and realignment from Realign Buffer is required and is handled both in pre and post-butter operation.

The butterfly calculation pipeline consists of fetching the data from outside (the first NTT iteration) or coefficient SRAM, going through the realign buffer to permute the data in the correct order and then feeding the Butterfly Unit to perform the butterfly calculation. After the operation, the coefficient is converted to either write back and write back the next iteration or stream out of the core in the last iteration of NTT, as shown in

Figure 1.

For I/O operations, the core takes in a stream of four 12-bit coefficients with a ready signal to indicate that it is ready to accept data, and when it is done, the core outputs a stream of four 12-bit data with an associated data valid indication.

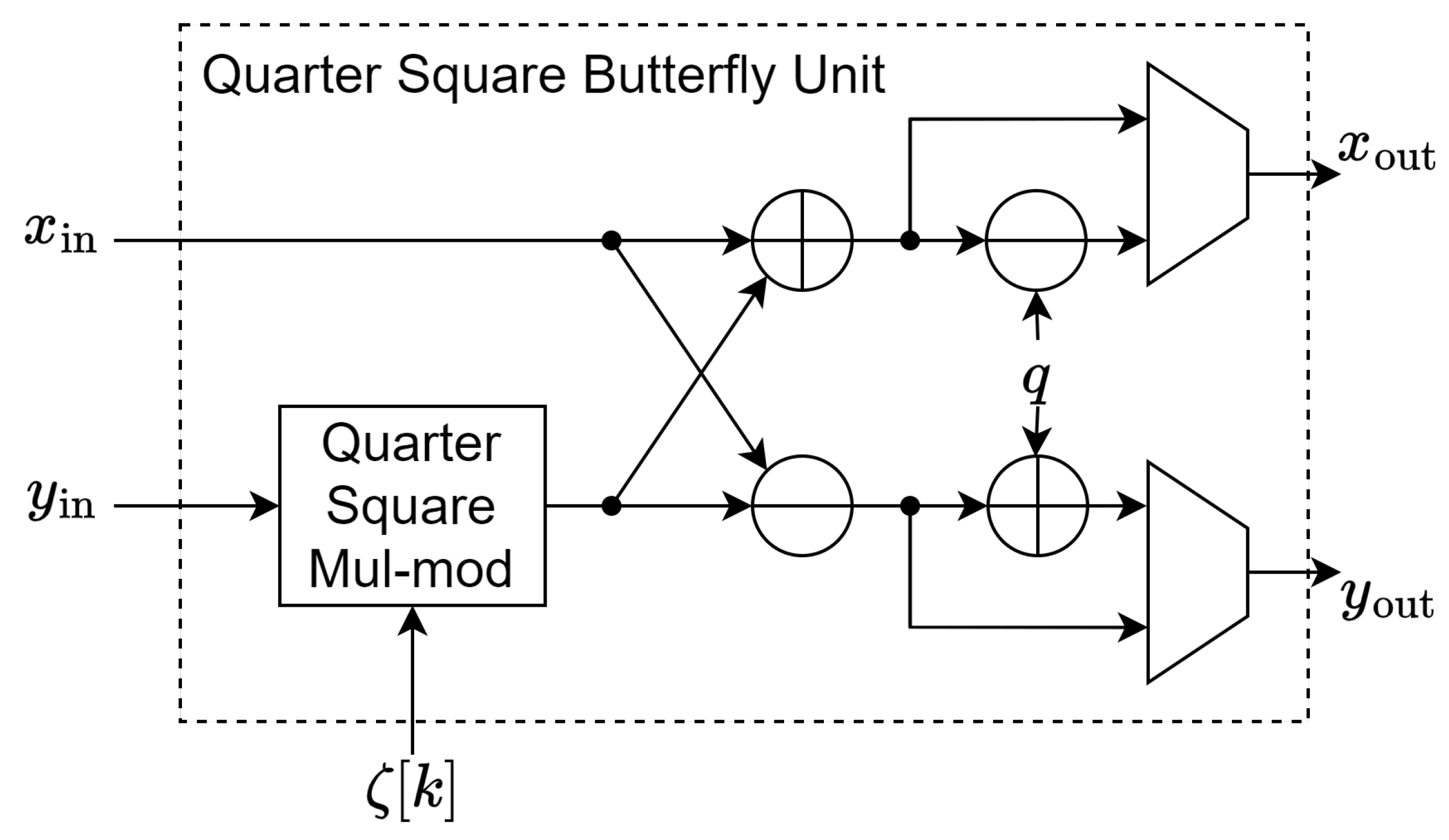

4.1. Butterfly Unit

In forward NTT operation as described in Algorithm 1, the inner loop unit performs the operation

1, which is called a butterfly calculation.

Where

k is an integer from 1 to 127, the table of

is precomputed and stored in ROM.

The most significant bottleneck of the butterfly unit is the modular multiplication of . If we perform this operation naively, the steps involve a 12x12 multiplication, which is most efficiently achieved by using a DSP on FPGA and then somehow reducing this 24-bit product mod q.

On the reference implementation of Kyber, which is optimized for AVX2 (software), this is achieved by performing the NTT and PWM in Montgomery form, replacing all modular multiplications with Montgomery multiplications, and then converting back to normal form at the INTT stage.

In this work, we proposed two solutions with different hardware tradeoffs to perform this particular modular multiplication efficiently.

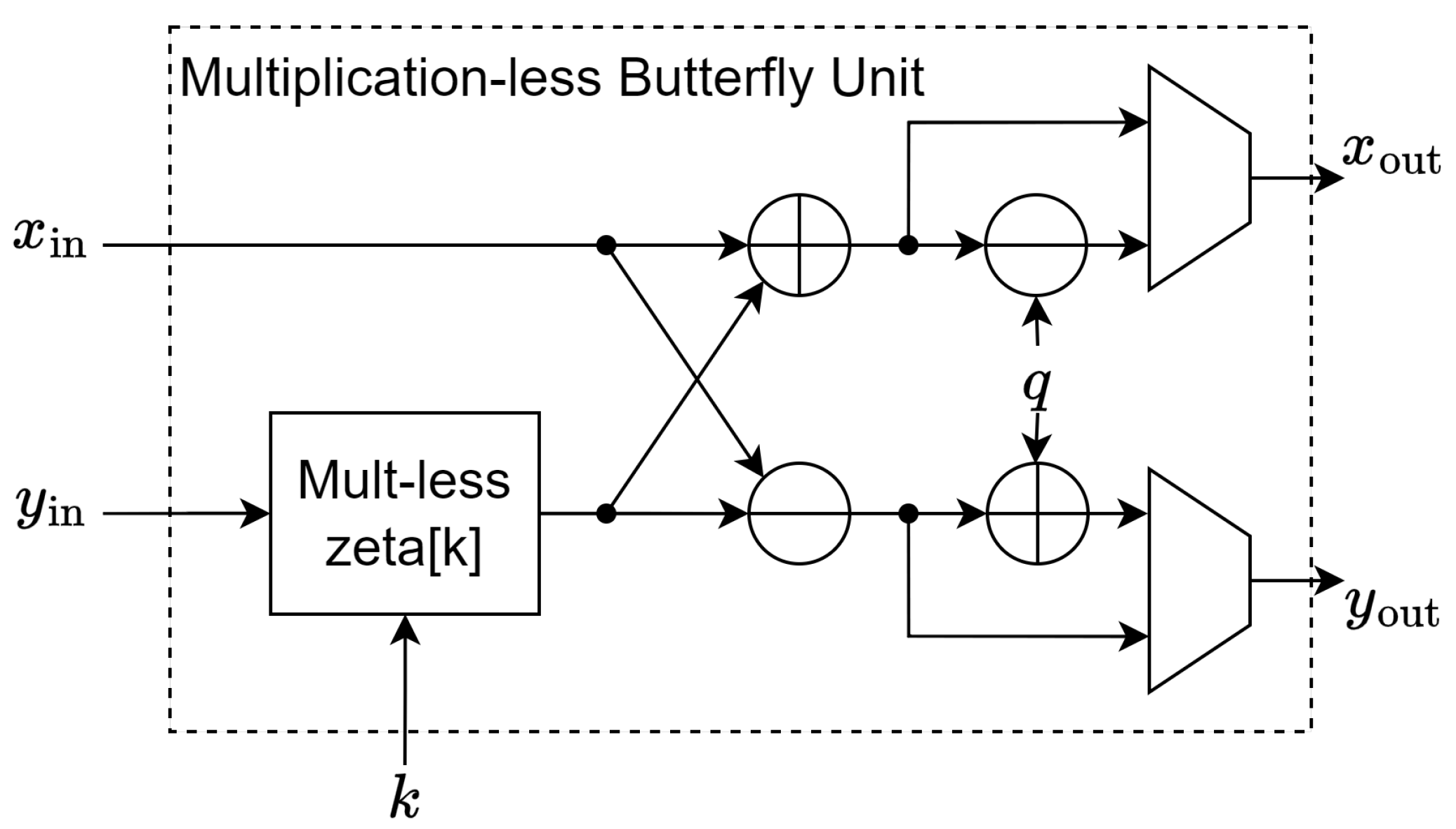

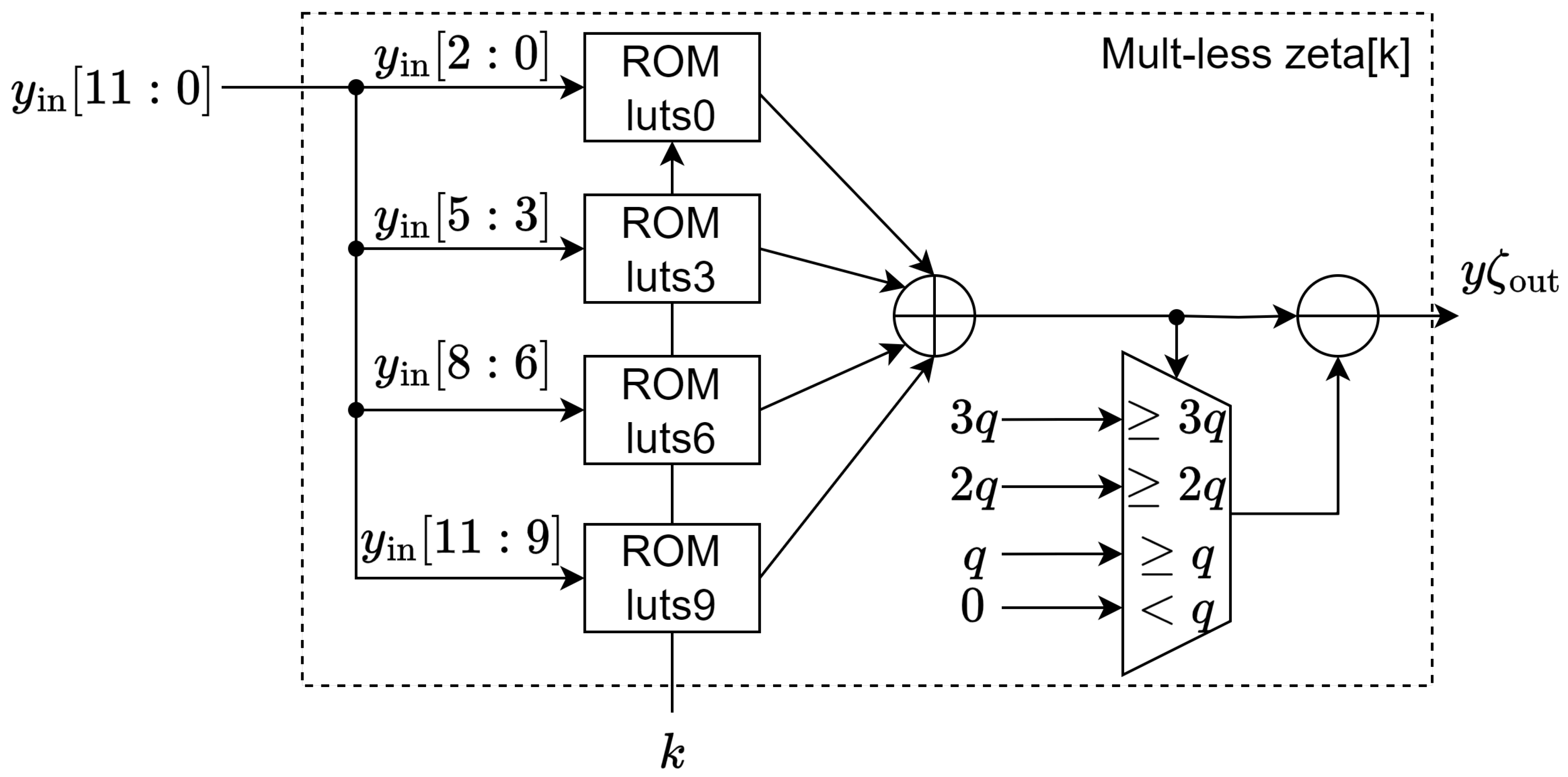

4.1.1. Multiplication-Less Method

This approach does not require the full multiplication of 12x12 for and instead uses a look-up table to achieve the modular multiplication.

The multiplication of a 12-bit unsigned number

by

,

, can be expanded as Eq.

2.

Every term of the Eq.

2 has 1024 possible outcomes of 12-bit each. Therefore, we can precompute all these terms and store them as four 1024x12 ROMs indexed by

, namely luts9, luts6, luts3, and luts0 with the value as described in Eq.

3.

The Eq.

2 now becomes Eq.

4.

Therefore, by using the precomputed table, we have eliminated the need to perform 12x12 multiplication and also the need to store the zetas array explicitly since it is already embedded in the multiplication look-up table itself. The Eq.

4 yields a 14-bit result where

, to reduce it mod

we simply perform conditional subtraction by

and then by

q. Thus, this variant of butterfly unit is implemented as in

Figure 2, where the modular multiplication is handled by a Mult-less zeta[k] submodule implemented as

Figure 3, the luts0, luts3, luts6, and luts9 ROMs store the values described in Eq.

3.

This method requires either four single-port 2KB ROMs per butterfly unit or four dual-port 2KB ROMs per two butterfly units. Since Xilinx’s BRAM does have the capability of being dual-port ROMs, this work uses the latter forms to achieve higher throughput and maximum utilization of Xilinx’s BRAMs, where the two butterfly units share the same ROMs as the look-up table. In our testing, the synthesis tool is able to automatically fuse two identical single-port ROMs inside two instances of the butterfly unit into a single dual-port ROM without any explicit RTL code change.

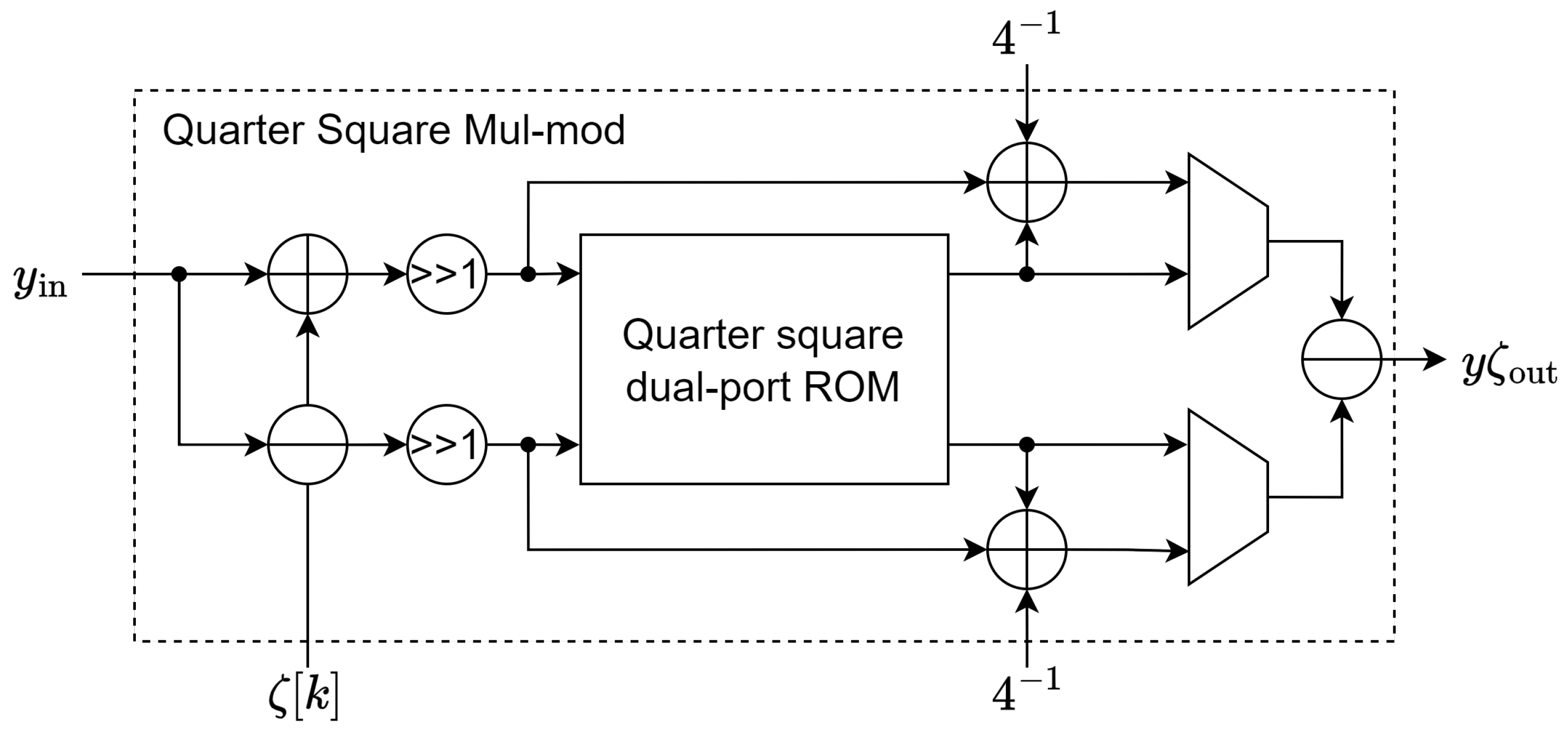

4.1.2. Quarter Square Multiplication Method

All 12x12 modular multiplications,

, could be naively stored and looked up by using a

x12 ROM, which is very space inefficient. On the other hand, a 12-bit modular square,

, only requires a

x12 ROM, realizing the quarter square multiplication identity

5 of two numbers

.

We can algebraically transform a multiplication to a difference of two-quarter squares using the identity

5. Since

is an odd prime, the inverse of 4 modulo

q exists, and the same identity

5 can be applied to perform modular multiplication

6 in the finite field

.

Therefore, the 12x12 modular multiplication

can be realized using a single

x12 quarter squares ROM using the identity

6. Furthermore, the quarter squares for both sum

and difference

can be looked up simultaneously in a single clock cycle using a dual-port ROM as in Eq.

7.

Note that the depth of ROM can be reduced by four by performing pre-processing and post-processing. The first reduction factor of 2 is achieved by taking advantage of the symmetry of squares ; in the modular field, this means . Thus, we only need to look up the quarter square of , which is only up to and is 11-bit wide.

The second reduction factor of 2 is achieved by further realizing the fact that the table saves both the even

and odd

entries; the odd entries

can be computed using the even entries

by

. Therefore, the tables only need to store the even quarter squares,

for

x up to

(10-bit); to compute

, we only look up the truncated number

and then conditionally adding

if

x is odd as in Eq.

8.

Finally, with the pre-processing and post-processing in place, we only need a single 1024x12 dual-port ROM to store the quarter squares, which fits perfectly in a single 2KB true dual-port BRAM of Xilinx FPGA. This variant of the butterfly unit is implemented as in

Figure 4. The modular multiplication is handled by a Quarter Square Mul-mod submodule implemented in

Figure 5, the Quarter square dual-port ROM stores the value of

described in Eq.

8. For simplicity, all trivial reductions modulo

q are omitted. This method requires a single true dual-port 2KB ROM per butterfly unit.

4.2. Realign Buffer

The butterfly unit requires the data to be accessed in a special way; for instance, we need to access the coefficient at offset

j and offset

to perform a single butterfly operation. Special handling is necessary when working with a single SRAM with a single read port. To handle this without compromising the throughput of the butterfly unit, the core’s SRAM must support fetching the double-width coefficient or 24-bit. The core fetches the data at position

j,

in the odd cycles and

,

in the very next even cycles; the data is being reordered to interleaved form

and output to the butterfly unit as shown in

Figure 6, since each butterfly unit requires a pair of coefficient and the read port supplies two coefficients on each cycle, with proper data ordering, a pipelined butterfly unit will be fully utilized. The same principle can be applied to the output of the butterfly unit and the write port of the SRAM; the data is realigned to contiguous form

and write-back to the SRAM.

5. Experimental Results

5.1. Experimental Setup

To verify the functionality and the performance of the NTT core under ideal conditions, we create a testbench with the core top as the unit test and interface with it using an AXI-like handshake mechanism. For the input side, after reasserting reset, we provide the core with a continuous stream of input data as the coefficient of the polynomial that we need the core to operate on. Eventually, the core will be finished and assert data_out_valid signal to provide a stream of output data as the transformed result. The operation latency is recorded as the number of cycles between the first in_data_valid from the testbench assertion up until the last assertion of out_data_valid (the previous result data). Furthermore, the result will then be checked with the expected result to make sure the core is working correctly; this is particularly handy when we are in the process of rapidly tweaking the core to fix the violated path to achieve higher frequency.

5.2. Results and Comparison

For this work, we have three variants of the NTT Core. The first two are the NTT-only cores with each proposed butterfly unit, namely and , respectively; these cores only support the forward NTT operation. However, since there aren’t many works that only support forward NTT, to make our result more comparable, we added a slight modification for the multiplication-less core to support both inverse and forward NTT on the fly via an intt_sel switch (variant ), this modification added two stages to the pipeline to switch between CT (Algorithm 1) and GS (Algorithm 2) butterfly.

The utilization result is reported after synthesized (with directive AreaOptimized_high), and PnR (with directive Explore) on NIST recommended xc7a100tfgg676-3 target device on Vivado 2023.2. The number of cycles is recorded from the experiment testbench and scales with the max frequency that the core can run to provide the wall-clock time latency in of each NTT/INTT operation.

In

Table 1, for the NTT-only cores, the core

uses 429 LUTs, 538 FFs, and 4 BRAMs with two parallel butterfly units (unroll factor 2), achieving the hardware efficiency of 441.87 LUT ATP and 554.14 FF ATP and have 459 cycles latency, while the core

, with a single butterfly, using only 379 LUTs, 414 FFs with 910 cycles latency, achieving 792.11 LUT ATP and 865.25 FF ATP, which is worse than

but only uses a single BRAM as ROM quarter squares look-up table for the butterfly unit. Note that it is possible not to unroll the design

and run with just a single butterfly unit; however, it will still require 4 BRAMs due to the nature of the approach, that is, 4 ROMs shared between two butterflies via two different ports, while the design

each butterfly will have a dedicated ROM hence there are more rooms to scale in the quarter square method. And finally, the hybrid core

, which supports both NTT and INTT and is based on

design, only requires slightly more resources at 541 LUTs (595.10 ATP), 680 FFs (748.00 ATP) and two-cycle latency penalty.

Thanks to the highly pipelined nature of the butterfly unit, the core

can run at a higher frequency (417MHz) on the Artix-7 platform than the other works, including the work [

22] (300MHz) that use a more recent FPGA Architecture Ultrascale+. The newly proposed modular multiplication methods can achieve better latency

than all studies except the fastest variant (2) of the study [

27]

. However, the variant (2) of the work [

27] uses nearly

more LUTs and

more BRAMs than ours while being only

faster. Therefore, we achieved

more efficient in LUT ATP and

more efficient in FF ATP than the work [

27] (2).

Compared to the work [

26], which employs the same parallel butterflies strategy, our work achieved

and

better LUT and FF ATP in the x1 configuration and

and

better LUT and FF ATP in the x2 configuration.

Our design also achieved about

better LUT ATP and

better FF ATP than [

21] and [

25]. For work [

25], they did use two fewer BRAMs but at the cost of 4 DSPs and much higher LUTs and FFs usage and have higher latency. Same for [

22] and [

27], which do use fewer BRAMs at the expense of significantly more LUTs/FFs and two DSPs; hence, less efficient than our work in LUT and FF ATP.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we have proposed a new Number Theoretic Transform architecture with a unique data access pattern along with a reorder buffer, making it suitable for a single shallow depth semi-dual-port SRAM; in FPGA architecture this is mapped to abundant LUTRAM resources; this allowed us to unroll the inner loop of NTT by a factor of 2 and beyond (x4, x8) to achieve lower latency without using significantly more resource in the control path. Furthermore, we also proposed two new look-up table-based butterfly units, namely multiplication-less and quarter square multiplication, both with different tradeoffs in LUT / BRAM usage and eliminate the need for computing the full product and subsequently the need for DSP utilization. Thanks to the new butterfly units, our whole design runs at a higher frequency (417Mhz), has good latency while maintaining excellent hardware usage efficiency (LUT / FF ATP) and is suitable to be embedded to a high performance, lightweight CRYSTALS Kyber accelerators for more efficient polynomial multiplication.

Acknowledgments

This research is funded by Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City (VNU-HCM) under grant number NCM2021-20-02. We acknowledge Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology (HCMUT), VNU-HCM for supporting this study.

References

- Shor, P.W. Polynomial-Time Algorithms for Prime Factorization and Discrete Logarithms on a Quantum Computer. SIAM Journal on Computing 1997, 26, 1484–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, L.K. A Fast Quantum Mechanical Algorithm for Database Search. Annual ACM Symp. on Theory of Comp. 1996, 212–219. [Google Scholar]

- Rivest, R.L.; Shamir, A.; Adleman, L. A Method for Obtaining Digital Signatures and Public-key Cryptosystems. Commun. ACM 1978, 21, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.S. Use of Elliptic Curves in Cryptography. Advances in Cryptology (CRYPTO) 1985, 417–426. [Google Scholar]

- Bos, J.; Ducas, L.; Kiltz, E.; Lepoint, T.; Lyubashevsky, V.; Schanck, J.M.; Schwabe, P.; Seiler, G.; Stehle, D.D. CRYSTALS - Kyber: A CCA-Secure Module-Lattice-Based KEM. European Symp. on Secu. and Privacy (EuroS&P) 2018, 353–367. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubashevsky, V.; Peikert, C.; Regev, O. On Ideal Lattices and Learning with Errors Over Rings. Advances in Cryptology (EUROCRYPT) 2010, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lindner, R.; Peikert, C. Better Key Sizes (and Attacks) for LWE-Based Encryption. Topics in Cryptology (CT-RSA) 2011, 319–339. [Google Scholar]

- Das, M.; Jajodia, B.B. Hardware Design of Optimized Large Integer Schoolbook Polynomial Multiplications on FPGA. Int. SoC Design Conf. (ISOCC) 2022, 65–66. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Ni, Z.; Kundi, D.; Liu, D.; Liu, W. . A Lightweight and Efficient Schoolbook Polynomial Multiplier for Saber. IEEE Int. Symp. on Circ. and Syst. (ISCAS) 2022, 2251–2255. [Google Scholar]

- Birgani, Y.A.; Timarchi, S.; Khalid, A. Area-Time-Efficient Scalable Schoolbook Polynomial Multiplier for Lattice-Based Cryptography. IEEE Trans. on Circ. and Syst. II: Express Briefs (TCAS-II) 2022, 69, 5079–5083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Liu, D.; Hu, A.; Li, A.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Lu, J.; Mo, C. An Instruction-configurable Post-quantum Cryptographic Processor Towards NTRU. Asian Hardware Oriented Secu. and Trust Symp. (AsianHOST) 2022, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Z.Y.; Wong, D.C.K.; Lee, W.K.; Mok, K.M.; Yap, W.S.; Khalid, A. KaratSaber: New Speed Records for Saber Polynomial Multiplication Using Efficient Karatsuba FPGA Architecture. IEEE Trans. on Computers 2023, 72, 1830–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Mera, J.M.B.; Karmakar, A.; Das, D.; Ghosh, S.; Verbauwhede, I.; Sen, S. A 334 μW 0.158 mm2 ASIC for Post-Quantum Key-Encapsulation Mechanism Saber With Low-Latency Striding Toom–Cook Multiplication. IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circ. 2023, 58, 2383–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, C.; Zhang, F.; Meng, Y.; Su, Y. TCPM: A Reconfigurable and Efficient Toom-Cook-Based Polynomial Multiplier Over Rings Using a Novel Compressed Postprocessing Algorithm. IEEE Trans. on Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI) Syst. 2023, 31, 1153–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Cheung, R.; Huang, K. PipeNTT: A Pipelined Number Theoretic Transform Architecture. IEEE Trans. on Circ. and Syst. II: Express Briefs (TCAS-II) 2022, 69, 4068–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, M.; Xu, C.; Huang, K.; Yu, H.; Yao, H.; Jiang, X.; Liu, D. Implementation of Number Theoretic Transform Unit for Polynomial Multiplication of Lattice-based Cryptography. Int. Conf. on Consumer Elec. and Comp. Engi. (ICCECE) 2022, 323–327. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Binh, K.D.N.; Pham, C.K.; Hoang, T.T. High-Speed NTT Accelerator for CRYSTAL-Kyber and CRYSTAL-Dilithium. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 34918–34930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauss, C.F. Nachlass: Theoria Interpolationis Methodo Nova Tractata. Carl Friedrich Gauss 1866, 3, 265–303. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, J.M. The Fast Fourier Transform in a Finite Field. Mathematics of Computation 1971, 25, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, J.W.; Tukey, J.W. An Algorithm for the Machine Calculation of Complex Fourier Series. Mathematics of Computation 1965, 19, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, D.; Liu, X.; Zou, X.; Niu, G.; Liu, B.; Jiang, Q. Towards Efficient Hardware Implementation of NTT for Kyber on FPGAs. IEEE Conference Publication 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, Z.; Khalid, A.; Liu, W.; O’Neill, M. Towards a Lightweight CRYSTALS-Kyber in FPGAs: an Ultra-lightweight BRAM-free NTT Core. IEEE Conference Publication 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Longa, P.; Naehrig, M. Speeding Up the Number Theoretic Transform for Faster Ideal Lattice-Based Cryptography. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2016/504, 2016. https://eprint.iacr.org/2016/504.

- Bisheh-Niasar, M.; Azarderakhsh, R.; Mozaffari-Kermani, M. Instruction-Set Accelerated Implementation of CRYSTALS-Kyber. IEEE Trans. on Circ. and Syst. I: Regular Papers (TCAS-I) 2021, 68, 4648–4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisheh-Niasar, M.; Azarderakhsh, R.; Mozaffari-Kermani, M. High-Speed NTT-based Polynomial Multiplication Accelerator for Post-Quantum Cryptography. IEEE Conference Publication 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bisheh-Niasar, M.; Azarderakhsh, R.; Mozaffari-Kermani, M. Instruction-Set Accelerated Implementation of CRYSTALS-Kyber. IEEE Journals & Magazine 2021, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Yaman, F.; Mert, A.C.; Öztürk, E.; Savas, E. A Hardware Accelerator for Polynomial Multiplication Operation of CRYSTALS-KYBER PQC Scheme. IEEE Conference Publication 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Y.; Li, S. A Compact Hardware Implementation of CCA-Secure Key Exchange Mechanism CRYSTALS-KYBER on FPGA. IACR Transactions on Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).