1. Introduction

In the third decade of the 21st century, the problem of global food security remains unresolved (it is estimated that 828 million people worldwide will suffer from hunger and malnutrition in 2021). Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, other armed conflicts, and the consequences of global warming have made it even more critical to address this issue. As the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023 report indicates, there has been an increase in the number of people experiencing hunger since 2019 [

1].

Suppose this trend continues in the coming years. In that case, it will be impossible to achieve sustainable development by 2030, including eradicating hunger (SDG2 target) and poverty (SDG1 target) and ensuring good health and quality of life (SDG3 target), targets adopted by the UN in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development resolution [

2]. For several years now, FAO experts in successive reports of this kind (published even before the health crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic) have stressed that increasing armed conflicts, economic downturns and downturns, the rise of extreme climatic events, with high prices for nutritious food and growing income inequality, are moving humanity further away from achieving the SDG2 goal of Zero Hunger by 2030.

It is becoming increasingly clear that food insecurity is one of the most pressing global challenges, affecting developing and highly developed countries such as the European Union. This problem became apparent during the global pandemic, which caused difficulties in food flows in global agri-food chains and led to higher food prices [

2]. Furthermore, in mid-2021, because of soaring fuel and energy prices even before Russia invaded Ukraine, inflationary pressures emerged in several countries due to rising demand and weaker harvests, which in turn led to an increase in food prices [

3]. Rising energy costs have also increased prices and reduced the availability of essential feed, fertilisers, and pesticides for European farmers. It is worth noting that the start of the war in Ukraine has led to an increase in the price of fertiliser, which is produced using natural gas [

4]. From 2022/2023 onwards, global cereal supply began to increase, allowing cereal markets to stabilise and favour a fall in cereal prices.

At the same time, it is becoming increasingly clear that the consequences of climate change in the form of extreme weather events are having a significant impact worldwide and in Europe, with the potential to alter the natural conditions for growing crops [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. It has recently contributed to a reduction in food security in European Union countries. However, it is essential to note that its member states are among the largest cereal producers in the world. They currently supply 20% of total world cereal production and export 15% of this production [

11]. As Obiedzińska [

12] points out, the grouping, simultaneously the largest importer and exporter of food, faces challenges that will define the possibilities of ensuring food security for every EU citizen.

As in the rest of the world, changing climatic conditions in Europe impact the development of agriculture and its production capacity. It is also essential to consider that although fossil fuel combustion has the most immense impact on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, agriculture significantly contributes to climate change, accounting for about 24% of global GHG emissions [

13]. These include carbon dioxide (CO₂), nitrous oxide (N

2O) and methane (CH

4). In Europe, the contribution of agriculture to the total emissions of these gases is lower, at 10%. As indicated by Prandecki

et al. [

14], it is assumed that the volume of its emissions corresponds to the absorption capacity of this gas by plants. Therefore, global warming is more influenced by the other two greenhouse gases, namely nitrous oxide (N

2O) and methane (CH

4). N

2O is emitted mainly from mineral and organic fertilisers and animal faeces, while CH

4 results from the intestinal fermentation of cattle [

15]. In Europe,

CH4 emissions from enteric fermentation and N2O from soils are responsible for 48% and 31% of total agricultural GHG emissions, respectively. CH4 from manure management is the third most important source of emissions, accounting for about 17%. The remaining sources make relatively small contributions, accounting for less than 5% of agricultural GHG emissions in total [

16].

Between 2005 and 2021, the volume of GHG emissions from EU agriculture revealed a slight downward trend of 3%, and in 2022, a 2% reduction in emissions was observed. However, this varied between member states. In 13 EU countries, there was an increase in emissions, while in 14 countries, there was a decrease. There were reductions in GHG emissions of more than 10% in Croatia, Greece, and Slovakia. In contrast, in countries such as Bulgaria, Estonia, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia and Luxembourg, there was an increase in emissions of more than 10%. It seems that to achieve the European Green Deal climate neutrality targets in individual member states, it may be necessary to consider significant reductions in emissions in sectors apart from agriculture. This could result from the energy transition and decarbonisation caused by fossil fuel combustion.

Kowalska [

17] highlights that researchers often arrive at different conclusions regarding the impact of agriculture on the environment and climate change, as well as the impact of global warming on agriculture, global food production and prices, and food security. Zhang

et al. [

18] have suggested that a 2 °C increase in the Earth’s temperature could potentially lead to increased wheat yields in wheat-exporting countries at high latitudes (e.g. China, India, the United States, Canada, Russia). This could be attributed to the CO₂ fertilisation effect, whereby ecosystems absorb nearly 25% of the carbon dioxide emitted worldwide. It allows for some reduction in the negative consequences of rising temperatures for cereal crops and increases wheat production. Cereal crops are recognised as a cornerstone of global food security [

19]. They occupy 30.6% of the total cereal area, followed by maize (26.7% of the sown area) and rice (22.6% of the crop). In low-latitude countries that import wheat, its yields may decrease significantly (e.g. Africa and South Asia). It could potentially lead to changes in grain prices and economic inequalities between wheat-importing and wheat-exporting countries and may even threaten food security [

17]. However, it is difficult to say whether the research team’s forecast will be confirmed.

One of the critical considerations in environmental economics is the impact of climate change on cereal production in Europe and its food security. It is a significant research problem that has not yet been sufficiently analysed. This research aims to provide empirical evidence on whether using renewable and non-renewable energy, CO₂ emissions and the resulting changes in temperature and precipitation can affect crop yields in European Union countries and, thus, food security. In undertaking this research, the authors draw upon the insights of W.D. Nordhaus’ concept of the Climate Casino [

20] and the potential impact of unpredictable climate change caused by greenhouse gas emissions on economic development and changes in agricultural productivity. The research objective required the realisation of several specific objectives, including the determination of the long-term relationships between:

Economic growth and the volume of cereal production per hectare.

The size of the area under cereal crops and the size of their yields.

Temperature and rainfall and cereal production per hectare.

CO₂ emissions and cereal yields.

Energy and renewable energy consumption and cereal production per hectare.

To achieve the research objectives, the authors proposed the following hypotheses:

H1: Economic growth rate modifies crop yields and national food security.

H2: Long-term changes in climatic conditions are the most determinant of food security for countries with low crop productivity.

H3: CO₂ emissions impact cereal yields nonlinearly, causing them to fall over the long term.

H4: The consumption of energy, including using renewable energy in agriculture, contributes to the long-term productivity of cereal crops.

The hypothesis was validated using an FGLS model robust to heteroscedasticity and cross-sectional dependence and a quantile regression model. The second model was employed to test the robustness of the tested model, along with the inclusion of additional variables and their joint interaction. The countries of the European Union were studied using data on economic growth, climate change (described by annual average temperatures and precipitation), CO₂ emissions, non-renewable and renewable energy consumption, and cereal crop yields over a long period (1992-2021).

The paper is structured as follows. Section one introduces the problem, and section two is devoted to a review of the relevant literature. Section three discusses the methods used to analyse the research concern and the data sources. Section four presents the study’s results, while section five discusses the results. Finally, section six includes a summary and recommendations for policymakers.

5. Discussion

The research findings demonstrate that climatic variables, such as precipitation and temperature, exert a considerable influence on cereal yields within the EU. The study results in quantiles indicate that temperature exerts the most pronounced impact on crops in countries with high crop yields while exerting the most negligible impact in countries with low yields. The outcomes thus align with the conclusions of Attiaoui and Boufateh [

47] and Nasrullah

et al. [

46], who also indicated a positive effect of temperature on cereal crop production in Tunisia and South Korea. However, studies by some authors have demonstrated that temperature is a factor negatively affecting cereal yields [

51,

54,

55,

56].

The research has demonstrated that precipitation considerably influences cereal production per hectare, with the most pronounced impact observed in countries with low and moderate cereal productivity. Conversely, these factors are less significant in high-productivity countries, where more advanced irrigation systems and crop technology are in place. These findings align with the ARDL model estimates of Chandio

et al. [

45], which indicate that rainfall enhances cereal productivity in both the short and long term.

The findings of Attiaoui and Boufateh [

47] also corroborate the notion that rainfall exerts a considerable and constructive influence on agricultural output, albeit over an extended period. Conversely, the outcomes of this study diverge from those of the Alehile

et al. [

51] investigation in Nigeria, which indicated that a reduction in annual rainfall yields a positive and statistically significant impact on crop production in the short term.

In this context, Polish researchers have obtained interesting results from assessing the impact of weather factors on the yield of selected cereals in Poland under conditions of progressive climate change. The study used variables such as temperature precipitation, the proportion of medium and heavy soils and mineral fertiliser use. The study observed a significant effect of the number of days with precipitation on the yields obtained. While regularly occurring, moderate rainfall was undoubtedly favourable, large amounts of rainfall adversely affected yields. Another crucial factor was temperature during the spring and summer months. Moderate temperatures were found to be the most favourable for yields. Temperature changes influenced the yield changes of individual cereals to varying degrees, with the most substantial effect observed in wheat. The study concluded that Polish agriculture would have to adapt to the new climatic conditions by implementing many measures, including modifying the structure of crops, ensuring the irrigation of plants against potential droughts with efficient, modern irrigation systems, increasing the genetic diversity of plants, and utilising modern agro techniques.

The research findings also indicate a significant, albeit small, effect of cultivated area on cereal productivity. Increasing cultivated areas is most important in countries with low cereal production per hectare; it does not play a role in countries with high yields. These results are consistent with those of Chandio

et al. [

45], who confirmed that increasing cropped area positively and significantly increased wheat yields in the long and short term. The findings of Nasrullah

et al. [

46] suggest a long-run relationship between cropped area and rice productivity in South Korea.

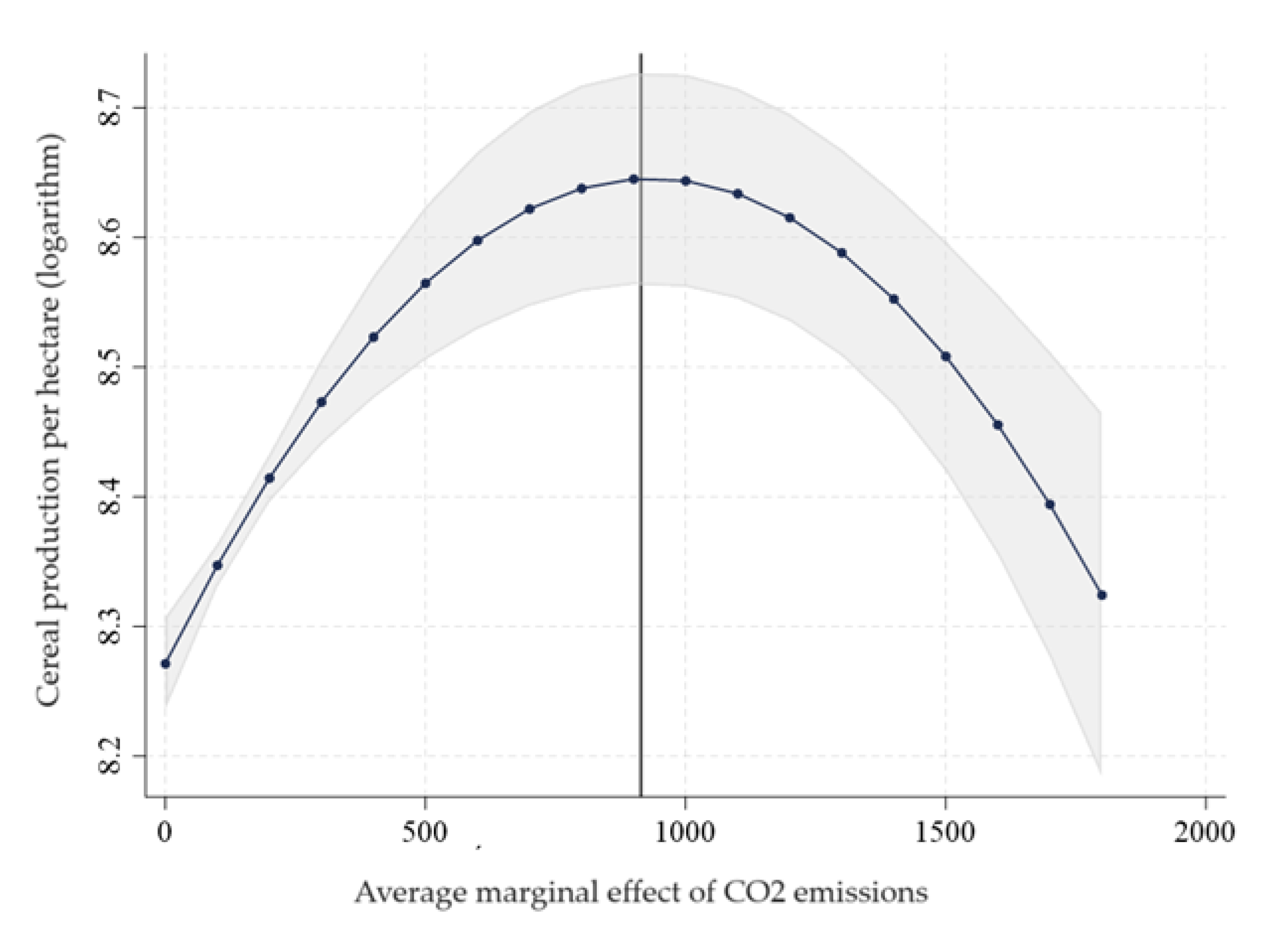

However, it is critical to exercise caution when comparing previous studies on the influence of climatic factors on cereal yields with the results obtained in this study. This is because similar studies have not been carried out for European countries, and the studies have primarily concerned economically underdeveloped countries in different climate zones. Furthermore, the authors’ study also confirmed the positive effect of increased CO₂ on cereal yields in the European Union countries studied. Conversely, the relationship between CO₂ emissions and cereal yields is nonlinear, initially exhibiting a positive correlation but subsequently exhibiting a negative effect once the estimated level of emissions is exceeded. Furthermore, the negative effect of CO₂ emissions on cereal production is most pronounced in countries with moderate crop yields.

The results obtained can be considered to some extent similar to those of Chandio

et al. [

50], who conclude that CO₂ significantly impacts agricultural production in both the long and short term. Similar observations are also confirmed by Kumar

et al. [

53]. In contrast, Onour [

55] estimates that a change in CO₂ has a positive and significant effect on cereal yields in the long and short term. Specifically, a 1% increase in CO₂ leads to a 3% increase in cereal yields in the short term and a 0.7% increase in the long term. Nevertheless, it is essential to note that previous studies have considered CO₂ emissions to be a linear variable without considering the U-shaped effect of CO₂ on cereal production.

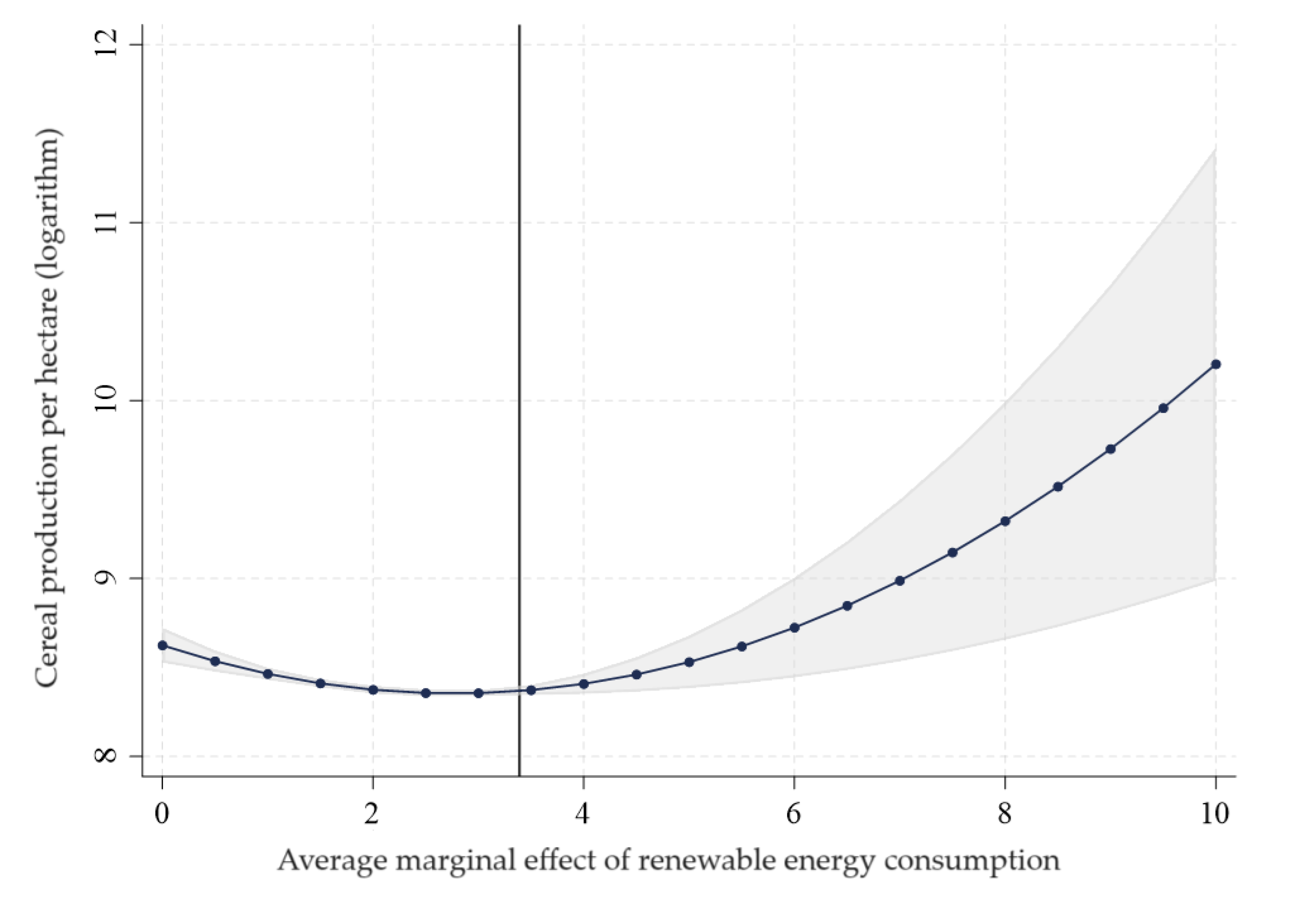

The final area investigated was the impact of increased energy consumption and renewable energy in agriculture on cereal production per hectare. The results confirm that energy consumption significantly and nonlinearly impacts crop productivity. At the same time, countries with low and moderate crop yields face higher costs for implementing agrotechnology. However, crop productivity increases once the energy consumption level estimated in the study is exceeded. The authors’ findings also indicate that the increase in energy consumption should be realised by using renewable sources. However, their use in the initial period may have a negative impact due to increasing costs. Nevertheless, as the share of renewable sources in agricultural energy consumption increases, crop productivity will increase in the long term. Regarding the findings, it is essential to acknowledge that this topic has not been investigated more comprehensively.

Robertson

et al. [

69] proposed high energy consumption in areas with high soil mechanisation and agricultural productivity, indirectly contributing to increased CO₂. Chandio

et al. [

70] investigated the dynamic interaction between energy consumption and economic progress in Pakistani agriculture from 1984 to 2016. The results, which used the ARDL method, demonstrated a positive relationship between gas and electricity consumption and agricultural production growth. A study by Ghosh [

71] revealed that short-term Granger causality results indicate a bidirectional relationship between value added from agriculture in India and energy consumption. It confirms the need to use energy-efficient technologies in agriculture to prevent environmental destruction. Aydoğan and Vardar [

72] demonstrated the potential for renewable energy to contribute to economic growth in the agricultural sector, thereby reducing fossil fuel consumption and improving the environment. Their analysis employed Granger causality as a case study of G7 countries.

6. Conclusions

The research findings supported the hypotheses, which were subsequently verified. Panel studies were conducted using advanced econometric models to determine the relationships between the use of renewable and non-renewable energy in agriculture, CO₂ and climate change and the volume of cereal production (which determines the food security of these countries). The research team sought to identify short- and long-term relationships for most European Union countries. The results obtained permit the following conclusions to be drawn:

- -

The influence of economic growth on cereal production is more pronounced in low-yielding countries. In contrast, developing economies facilitate the production of higher yields in agriculture.

- -

The expansion of cultivated area exerts the most pronounced influence in countries with low crop yields, whereas, in countries with high yields, it has no discernible impact on the volume of cereal production per hectare.

- -

It has been confirmed that precipitation significantly influences crop yields in countries with low and moderate cereal production per hectare. Conversely, precipitation has relatively few consequences in countries with high cereal yields. It is attributed to the presence of more advanced irrigation systems and crop technology, which serve to mitigate the impact of precipitation on yields.

- -

In high-yielding countries, temperature has the most significant impact on crops, whereas in low-yielding countries, the most negligible impact is observed regarding cereal production.

- -

Expanding energy consumption and integrating renewable energy sources into agricultural practices present a more formidable challenge for countries with low and moderate crop yields.

- -

The increase in CO₂ will have the most rapid effect on cereal production in countries with moderate crop yields.

The study’s findings and the resulting conclusions indicate the following implications of the impact of climate change on the food security of EU countries in the following years. From the perspective of European food security, it is imperative to reduce CO₂ emissions to enhance the stability of climatic conditions. In certain EU countries, agro-technical treatments are imperative to augment cereal production. However, renewable energy should be employed for this purpose. Countries with low and moderate crop yields should prioritize the implementation of technological advances and combating global warming. It is therefore necessary to implement shielding programmes for cereal producers financed from the state budget as part of agricultural support and financial transfers from EU agricultural aid programmes. Furthermore, activities should be carried out to educate the public about the effects of excessive CO₂ and the adverse effects of climate change on agriculture. It is of particular importance to educate rural residents and farmers about the effects of excessive CO₂ and the adverse effects of climate change on agriculture. Furthermore, it is recommended that programmes be implemented to increase the efficiency of cereal production and use more renewable energy resources (undertaking research and development work financed, among other things, from EU aid funds and introducing new solutions in this area in the Member States).

As with any study, this one is subject to certain limitations. In this study, the authors assumed that exogenous factors such as temperature and precipitation have a linear effect on the dependent variable, although weather conditions frequently demonstrate nonlinear effects. Cereal yields tend to be highest in specific temperature and precipitation ranges [

73]. Therefore, excessive temperature, precipitation, or both increases can negatively affect crop production. However, subsequent research may consider temperature and precipitation as nonlinear variables. Future research on these issues may seek to assess the impact of precipitation and temperature variability on individual EU countries’ production volumes, considering factors such as soil quality. Further research can also consider the short-term impact of the factors analysed on cereal production volumes and EU countries’ food security through ARDL Cross-sectional models.

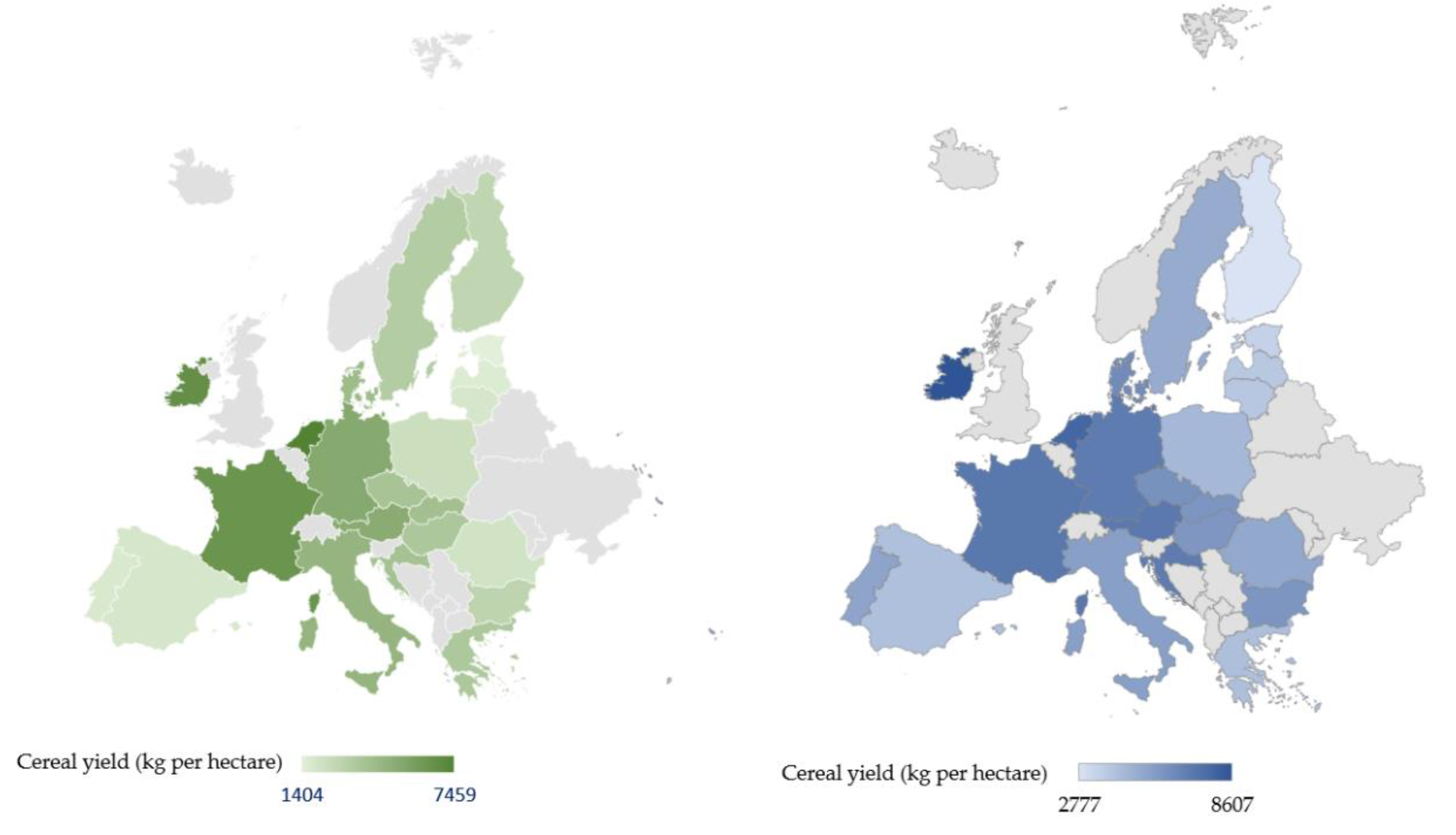

Figure 1.

Cereal crop yields in European Union countries surveyed in 1992 (left) and 2021 (right). Source: FAO Stat.

Figure 1.

Cereal crop yields in European Union countries surveyed in 1992 (left) and 2021 (right). Source: FAO Stat.

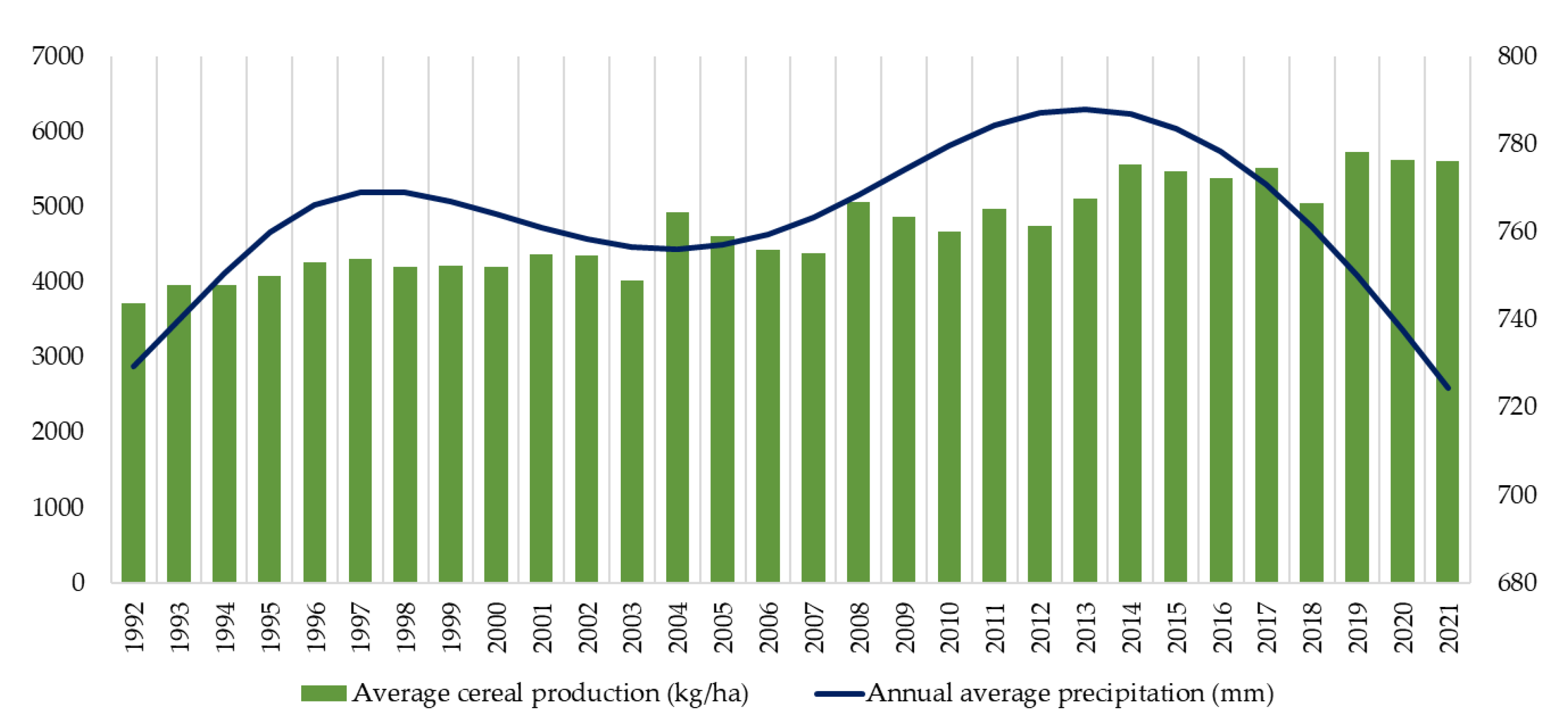

Figure 2.

The relationship between the countries’ cereal yields and the average annual rainfall. Source: FAO Stat.

Figure 2.

The relationship between the countries’ cereal yields and the average annual rainfall. Source: FAO Stat.

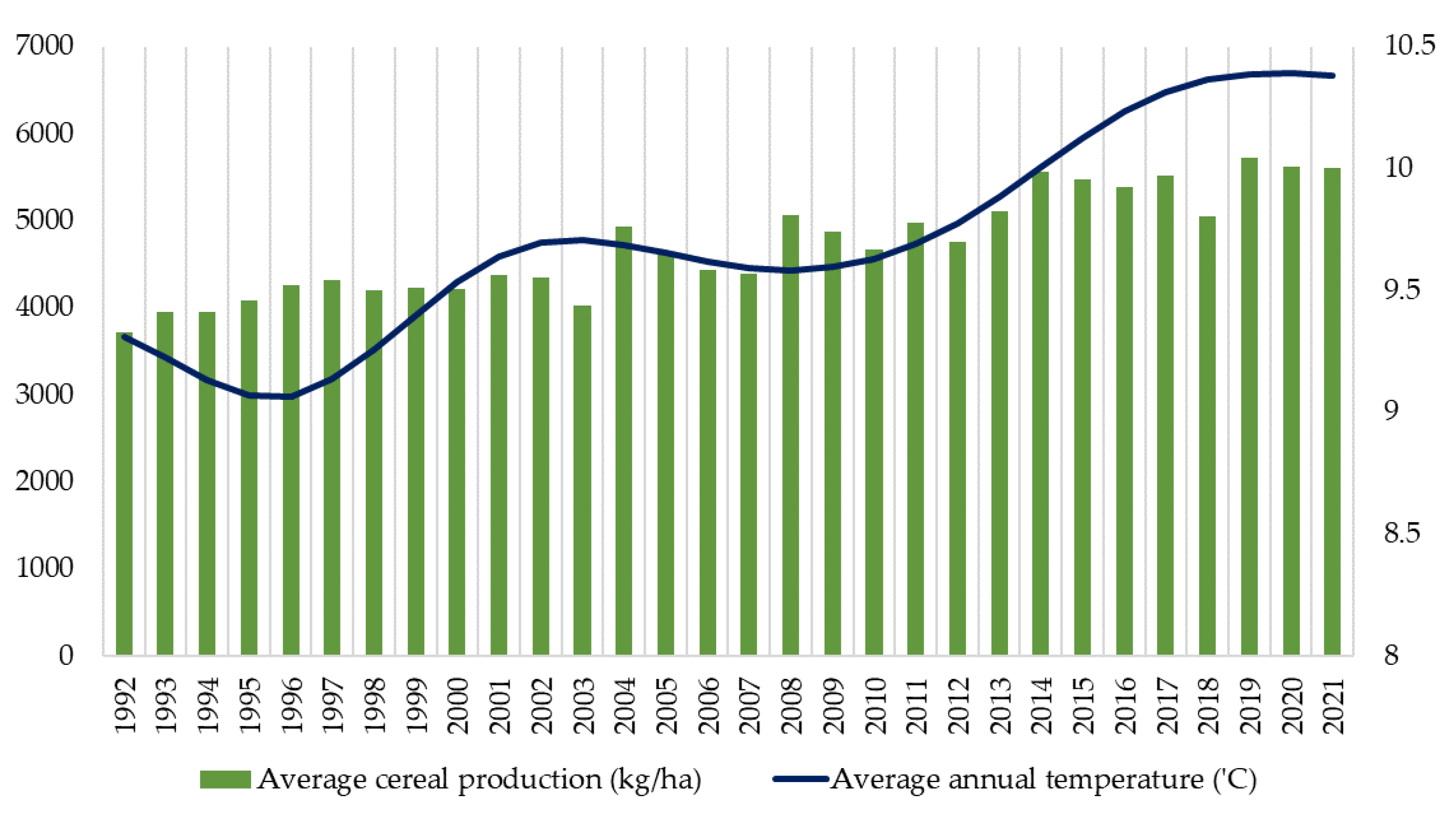

Figure 3.

The relationship between the countries’ cereal yields and the average annual temperature. Source: FAO Stat.

Figure 3.

The relationship between the countries’ cereal yields and the average annual temperature. Source: FAO Stat.

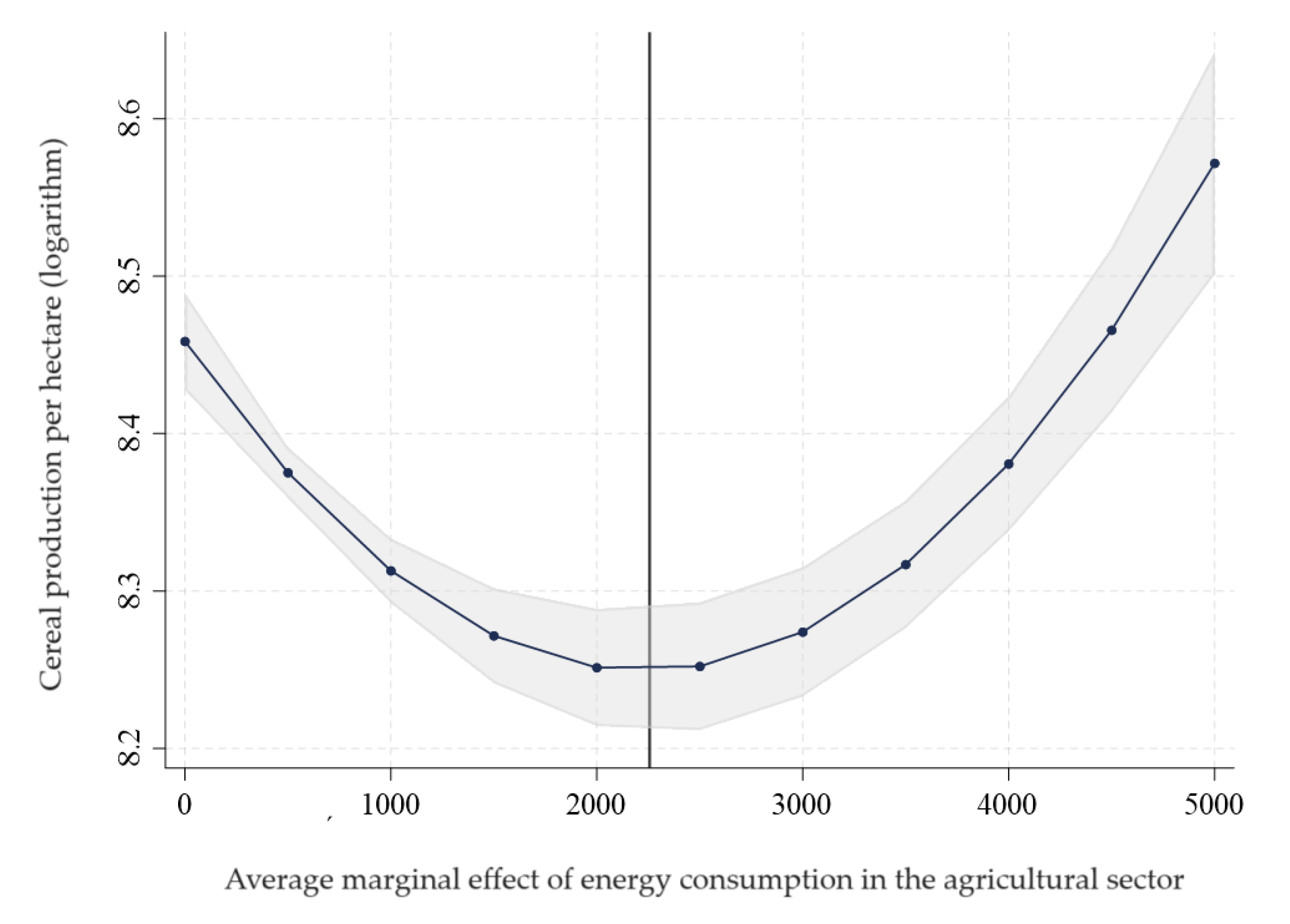

Figure 4.

Projected change in cereal production due to an increase in agricultural energy consumption in the surveyed EU countries.

Figure 4.

Projected change in cereal production due to an increase in agricultural energy consumption in the surveyed EU countries.

Figure 5.

Projected change in cereal production in the surveyed EU countries due to increased CO₂ emissions.

Figure 5.

Projected change in cereal production in the surveyed EU countries due to increased CO₂ emissions.

Figure 6.

Projected change in cereal production in the surveyed EU countries due to the increase in the share of renewable energy.

Figure 6.

Projected change in cereal production in the surveyed EU countries due to the increase in the share of renewable energy.

Table 1.

A synthetic review of recent research findings regarding the relationship between cereal production and climatic and economic factors.

Table 1.

A synthetic review of recent research findings regarding the relationship between cereal production and climatic and economic factors.

| Source / Study |

Period |

Country |

Results |

Methodology |

| Warsame et al., 2021 [43] |

1985-2016 |

Somalia |

P(+)→ CP(+) T(+)→ CP(-)razmakCO₂(+)→ CP(+)razmakLCU(+)→ CP(+) |

ARDL |

| Chandio et al., 2020 [44] |

1983-2016 |

Pakistan |

CO₂(+)→ CP(+)razmakEC (+)→ CP (+) |

ARDL |

| Chandio et al., 2022 [45] |

1988-2014 |

Bangladesh |

T(+)→ CP (-)razmakCO₂(+)→ CP(-)razmakLCU→ CP(+)razmakEC→ CP(+)razmakP (+)→ CP(+) |

ARDL |

| Nasrullah et al., 2021 [46] |

1973-2018 |

South Korea |

T(+)→ CP(+)razmakCO₂ (+)→ CP(+)razmakLCU (+)→ CP (+) |

ARDL |

| Attiaoui and Boufateh, 2019 [47] |

1975-2014 |

Tunisia |

P(-)→ CP(-) T(+)→ CP(+) |

ARDL |

| Chandio et al., 2021 [48] |

1980-2016 |

Turkey |

T (+)→ CP(-)razmakCO₂ (+)→ CP(-)razmakLCU (+)→ CP(-) |

ARDL |

| Ahsan et al., 2020 [44] |

1971-2014 |

Pakistan |

CO₂(+)→ CP(+)razmakLCU (+)→ CP(+)razmakEC (+)→ CP(+) |

ARDL |

| Ahmed et al., 2023 [49] |

1990-2019 |

India |

CO₂ (+)→ FP(-)razmakT (+)→ FP(-) |

ARDL |

| Chandio et al., 2020 [50] |

1982-2014 |

China |

CO₂ (+)→ CP(+)razmakT(+)→ CP(-)razmakP(+)→ CP(-)razmakLCU (+)→ CP(-) |

ARDL |

| Alehile et al., 2022 [51] |

1990-2020 |

Nigeria |

T(+)→ CP(-)razmakP(+)→ CP(-) |

NARDL |

| Xiang and Solaymani, 2022 [52] |

1969-2018 |

Malaysia |

T(+)→ CP(-)razmakP(+)→ CP(-)razmakCO₂→ CP(-) |

ARDL |

| Kumar et al., 2021 [53] |

1971-2016 |

Lower middle-income countries |

T(+)→ CP(-)razmakP(+)→ CP(-)razmakCO₂(+)→ CP(+)razmak |

FGLS/FMOLS |

| Ogundari and Onyeaghala, 2021 [54] |

1981 - 2010 |

African countries |

P(+)→ CP (+)razmakT (+)≠ CP(+) |

FGLS |

| Onour, 2019 [55] |

1961-2016 |

Sudan |

CO₂(+)→ CP(+)razmak |

ARDL |

| Abbasi, 2021 [56] |

1985-2018 |

China |

CO₂(+)→ CP(+) |

ARDL/VECM |

Table 2.

Description of the data and variables used in the study.

Table 2.

Description of the data and variables used in the study.

| Variable |

Symbol |

Units |

Source |

| Yield (cereal production per hectare) |

CP |

kg/ha |

WDI |

| Area under cereals |

LCU |

ha |

WDI |

| GDP per capita |

GDP |

Constant USD 2015 |

WDI |

| Average annual precipitation |

P |

mm |

EEA |

| Average annual temperature |

T |

°C |

EEA |

| Energy consumption in the agricultural sector |

EC |

thousand tonnes eq of crude oil |

UNFCCC |

| CO₂ emissions |

CO₂ |

kg per capita |

WDI/ UNFCCC |

| Consumption of renewable energy |

REW |

% of total final energy consumption |

WDI |

Table 3.

Basic descriptive statistics of the variables studied.

Table 3.

Basic descriptive statistics of the variables studied.

| Period |

Variable |

Mean |

Min |

Max |

SD |

| 1992 |

CP |

3717.97 |

1403.75 |

7459.17 |

1723.88 |

| 2021 |

5611.95 |

2777.20 |

8606.73 |

1501.72 |

| 1992 |

GDP |

17575.14 |

2857.78 |

40384.45 |

12398.58 |

| 2021 |

31185.66 |

8638.64 |

90590.08 |

20052.35 |

| 1992 |

LCU |

2684077.00 |

180936.30 |

9324911.00 |

2867495.00 |

| 2021 |

2364339.00 |

169719.10 |

9326776.00 |

2669707.00 |

| 1992 |

EC |

1341.81 |

266.51 |

4155.55 |

1253.48 |

| 2021 |

1244.37 |

88.11 |

4270.55 |

1470.98 |

| 1992 |

P |

729.48 |

559.02 |

1165.96 |

172.30 |

| 2021 |

724.52 |

557.29 |

1206.40 |

165.84 |

| 1992 |

T |

9.31 |

2.20 |

15.65 |

3.26 |

| 2021 |

10.38 |

3.04 |

16.46 |

3.39 |

| 1992 |

CO₂ |

223.44 |

39.85 |

1700.19 |

351.13 |

| 2021 |

213.35 |

98.08 |

1637.13 |

320.29 |

| 1992 |

REW |

10.49 |

1.15 |

32.87 |

10.62 |

| 2021 |

26.77 |

10.78 |

58.39 |

12.81 |

Table 4.

Correlation matrix for the studied variables.

Table 4.

Correlation matrix for the studied variables.

| Variable |

CP |

GDP |

LCU |

EC |

P |

T |

CO2 |

REW |

| CP |

1.000 |

0.653 |

-0.038 |

0.257 |

0.504 |

0.182 |

0.424 |

-0.192 |

| GDP |

0.653 |

1.000 |

-0.116 |

0.245 |

0.330 |

-0.180 |

0.354 |

0.073 |

| LCU |

-0.038 |

-0.116 |

1.000 |

0.450 |

-0.401 |

0.186 |

-0.318 |

-0.110 |

| EC |

0.257 |

0.245 |

0.450 |

1.000 |

-0.102 |

0.227 |

0.011 |

-0.387 |

| P |

0.504 |

0.330 |

-0.401 |

-0.102 |

1.000 |

0.275 |

0.581 |

-0.048 |

| T |

0.182 |

-0.180 |

0.186 |

0.227 |

0.275 |

1.000 |

0.115 |

-0.361 |

| CO₂ |

0.424 |

0.354 |

-0.318 |

0.011 |

0.581 |

0.115 |

1.000 |

-0.388 |

| REW |

-0.192 |

0.073 |

-0.110 |

-0.387 |

-0.048 |

-0.361 |

-0.388 |

1.000 |

Table 5.

Results of the VIF test to investigate multicollinearity.

Table 5.

Results of the VIF test to investigate multicollinearity.

| Variable |

VIF |

1/VIF |

| CO₂ |

2.23 |

0,449 |

| P |

2.19 |

0,457 |

| REW |

1.85 |

0,541 |

| EC |

1.81 |

0,552 |

| GDP |

1.64 |

0,609 |

| LCU |

1.64 |

0,61 |

| T |

1.58 |

0,633 |

| Mean VIF |

1.85 |

Table 6.

Cross-section and unit root dependence tests.

Table 6.

Cross-section and unit root dependence tests.

| Variable |

Pesaran CD |

Breusch-Pagan LM |

CIPS I(0) |

CIPS I(1) |

| CP |

25.91*** |

1162.24*** |

-4.980*** |

-6.190*** |

| GDP |

32.30*** |

2039.75*** |

-1.960 |

-3.699*** |

| LCU |

18.32*** |

1396.63*** |

2.360*** |

-5.538*** |

| T |

32.23 |

1968.11*** |

-2.998*** |

-2.232*** |

| P |

53.75*** |

3350.06*** |

-1.241 |

-4.565*** |

| EC |

42.24*** |

3471.88*** |

-2.499*** |

-5.133*** |

| CO₂ |

37.03*** |

2056.33*** |

-1.789 |

-5.797*** |

| REW |

58,31*** |

3749.04*** |

-2.645*** |

-4.977*** |

Table 7.

Westerlund cointegration and heteroscedasticity tests.

Table 7.

Westerlund cointegration and heteroscedasticity tests.

| Test |

Statistic |

| Westerlund variance ratio |

-2.1617** |

| Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg test for heteroscedasticity (Chi2) |

11.76*** |

| Cameron & Trivedi’s decomposition of IM-test (Chi2) |

250.14*** |

Table 8.

The results of the FGSL model estimation.

Table 8.

The results of the FGSL model estimation.

| Variable |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

Model 5 |

| GDP |

0.318*** |

0.3619*** |

0.224*** |

0.314*** |

0.364*** |

| T |

0.163*** |

0.1842*** |

0.085*** |

0.133** |

0.193*** |

| P |

0.585*** |

0.5216*** |

0.446*** |

0.586*** |

0.432*** |

| LCU |

0.041*** |

0.0691*** |

0.040*** |

0.048*** |

0.095*** |

| EC |

|

-0.00019*** |

|

|

-0.00023*** |

| SQEC |

|

4.21e-08*** |

|

|

4.66E-08*** |

| CO₂ |

|

|

0.587*** |

|

0.00065*** |

| SQCO₂ |

|

|

-0.041** |

|

-3.85E-07* |

| REW |

|

|

|

-0.217*** |

-0.221*** |

| SQREW |

|

|

|

0.032*** |

0.041*** |

| Constant |

0.436 |

0.0575 |

0.597 |

0.768 |

0.461 |

| Inflection point |

|

2256.53 |

914.15 |

3.39 |

|

| R2

|

0.573 |

0.592 |

0.609 |

0.605 |

0.630 |

| Chi2

|

1448.17 |

1013.94 |

1029.86 |

657.91 |

482.92 |

Table 9.

Results of quantile estimation for energy consumption (EC) in the surveyed EU countries.

Table 9.

Results of quantile estimation for energy consumption (EC) in the surveyed EU countries.

| Variable |

Quantile |

| Q = 0.25 |

Q = 0.50 |

Q = 0.75 |

| GDP |

0.411*** |

0.356*** |

0.326*** |

| LCU |

0.110*** |

0.059** |

-0.008 |

| P |

0.598*** |

0.512*** |

0.194*** |

| T |

0.192*** |

0.198*** |

0.316*** |

| ECP |

-0.00028*** |

-0.00022*** |

-0.00007 |

| SQECP |

6.01E-08*** |

4.95E-08*** |

1.84E-08 |

| Const |

-1.600*** |

0.329 |

3.518*** |

| Turning point |

2329.45 |

2222.22 |

|

| Quantile Slope Equality Test |

131.69*** |

|

|

| Symmetric Quantiles Test |

10.78 |

|

|

Table 10.

Results of quantile estimation for CO₂ emissions in the surveyed EU countries.

Table 10.

Results of quantile estimation for CO₂ emissions in the surveyed EU countries.

| Variable |

Quantile |

Variable |

Quantile |

| Q = 0.25 |

Q = 0.50 |

Q = 0.75 |

| GDP |

0.267*** |

0.306*** |

0.308*** |

| LCU |

0.088*** |

0.048*** |

0.002 |

| P |

0.668*** |

0.472*** |

0.161*** |

| T |

0.075** |

0.159*** |

0.311*** |

| CO₂ |

0.00095*** |

0.00093*** |

0.00058*** |

| SQCO₂ |

-5.32E-07*** |

-5.46E-07*** |

-3.30E-07*** |

| Const |

-0.351 |

1.114** |

3.677*** |

| Turning point |

892.86 |

866.66 |

878.78 |

| Quantile Slope Equality Test |

83.025*** |

|

|

| Symmetric Quantiles Test |

12.06* |

|

|

Table 11.

Quantile estimation results for the share of renewable energy in agriculture of the surveyed EU countries.

Table 11.

Quantile estimation results for the share of renewable energy in agriculture of the surveyed EU countries.

| Variable |

Quantile |

| Q = 0.25 |

Q= 0.50 |

Q = 0.75 |

| GDP |

0.317*** |

0.340*** |

0.337*** |

| LCU |

0.080*** |

0.056*** |

-0.003 |

| P |

0.710*** |

0.529*** |

0.214*** |

| T |

0.107*** |

0.183*** |

0.324*** |

| REW |

-0.220** |

-0.272*** |

-0.051 |

| SQREW |

0.034*** |

0.046*** |

0.005 |

| Const |

-0.630 |

0.722 |

0.856*** |

| Turning point |

3.24 |

2.95 |

|

| Quantile Slope Equality Test |

72.83*** |

|

|

| Symmetric Quantiles Test |

20.07*** |

|

|

Table 12.

Estimation results for the pooled model (robust testing).

Table 12.

Estimation results for the pooled model (robust testing).

| Variable |

Quantile |

| Q = 0.25 |

Q= 0.50 |

Q = 0.75 |

| GDP |

0.386*** |

0.354*** |

0.327*** |

| LCU |

0.107*** |

0.086*** |

0.011 |

| P |

0.530*** |

0.489*** |

0.214*** |

| T |

0.167*** |

0.180*** |

0.283* |

| ECP |

-0.00030*** |

-0.00022*** |

-0.00012* |

| SQECP |

6.05E-08*** |

4.57E-08*** |

2.52E-08 |

| CO₂ |

0.000636** |

0.000640** |

0.000416** |

| SQCO₂ |

-4.16E-07** |

-4.37E-07** |

-2.80E-07** |

| REW |

-0.2691** |

-0.2658*** |

-0.0557 |

| SQREW |

0.0473** |

0.0465*** |

0.0036 |

| Const |

-0.5128 |

0.4353 |

3.2629*** |

| Quantile Slope Equality Test |

73.22* |

|

|

| Symmetric Quantiles Test |

16.72 |

|

|