1. Introduction

Simply put, politics in democracies is about translating values and beliefs into narratives about public problems and viable policy solutions, and further into political proposals on goals, strategies and policy instruments. Having framed problems and potential solutions, policy actors try to establish a monopoly on political understandings concerning the policy of interest and the institutional arrangement reinforcing that understanding (Baumgartner & Jones, 1993). Advocacy activities of organizations and interest groups (IGs) have increased dramatically since the mid-1980s (Harris & Fleischer, 2017). Organized as lobbyists, policy entrepreneurs, intermediaries or advocacy coalitions, different stakeholders aim to influence agenda-setting and other policy actor’s beliefs and preferences in the policy process and thus policy outcome, as well as the structure of democratic institutions (Baumgartner & Leech, 1998; Dür, 2008; Klüver, 2013; Bitonti, 2017a, 2017b; Herweg et al., 2023; Nohrstedt et al., 2023; Tosun et al., 2023). More pervasive public policy issues such as product safety, sustainable development, fair trading, civil rights and climate change make public executives and legislators obvious targets for business and non-business advocacy of stakeholders to ensure their interests are protected or taken into consideration in public policies (Harris, 2001; Gullberg, 2008; Bitonti & Harris, 2017).

1.1. Governance for a Just Transition

The current climate emergency (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2023) and other crises related to sustainability has led to calls for climate justice (Shepard & Corbin-Mark, 2009; Schlosberg & Collins, 2014) and a just transition to reach the Paris Agreement’s temperature targets, national and regional targets on climate neutrality and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (e.g. Capetola, 2008; Böhmelt et al., 2015; Evans & Phelan, 2016; McCauley & Heffron, 2018; Bennett et al., 2019; Velicu & Barca, 2020; Newell et al., 2021; Wang & Lo, 2021). Climate justice can be defined as:

”the ethical and human rights dimensions of global warming, the disproportionate burden of legacy pollution, the unsustainable rise in energy costs for low-income families, and the impacts of energy extraction, refining, and manufacturing on vulnerable communities” (Shepard & Corbin-Mark, 2009, p. 163).

With the focus on a just transition, and an increasing presence of NGOs in global climate governance and governance of the UN SDGs, scholars have raised the importance of analysing and evaluating climate policy not only from the perspective of cost-effectiveness advocated by economists (e.g. Hassler et al., 2016; Nordhaus, 2019), but also from perspectives of democracy, with focus on legitimacy, accountability and justice as guiding principles (Newell, 2008; Biermann & Gupta, 2011; Bäckstrand et al., 2018; Jordan et al., 2015; Kuyper et al., 2018). The clean energy transition must be fair and unite environmental and social justice issues in the movement towards climate neutrality (Bennett et al., 2019; Muñoz Cabré & Vega Araújo, 2022). It must provide justice to all parties, regardless of who you are, where you work or where you live – while reducing emissions quickly enough (McCauley & Heffron, 2018; Newell et al., 2021; Bouzarovski, 2022). Costs and benefits of the transition must be distributed fairly. Moreover, the transition must be socially inclusive (Capetola, 2008; Osička et al., 2023). Do all interested parties, not least those who risk being hit the hardest of climate change and climate policies, get the opportunity to participate and make their voice heard in the policy processes? It is important that people have insight and the opportunity to influence how the transition takes place.

1.2. Policy Entrepreneurs—Key Actors in Climate Governance?

Political science offers a variety of theories, frameworks and concepts to explain policy processes and the roles of policy actors influencing decision-making on public policy, including on climate policy. One such concept is the policy entrepreneur, introduced by Robert A. Dahl (1961) and popularized by John W. Kingdon (1984), who defines them as “advocates who are willing to invest their resources – time, energy, reputation, money – to promote a [policy] position in return for anticipated future gain in the form of material, purposive, or solitary benefits” (Kingdon, 1984, p. 179). The concept is attractive since it highlights the role of agency in understanding policy change (Mintrom & Norman, 2009; Mintrom, 2019a; Arnold, 2021; Petridou & Mintrom, 2021). In view of Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework, policy change occurs when the multiple streams of problems, policy options and politics are connected by policy entrepreneurs (Herweg et al., 2023), who, as individuals or collectives, attempt “to transform policy ideas into policy innovations and, hence, disrupt status quo policy arrangements” (Petridou & Mintrom, 2021, p. 945). They are central actors in political agenda-setting and for policy change as they ‘soften’ the political system for certain ideas and make sure there are packages of problems and policies ready when there is a policy window of opportunity to put the problem on the agenda (Mintrom, 2019a).

Leading scholars on policy entrepreneurs stress, uncritically, the need for more actors to become policy entrepreneurs, to “step forward and catalyze change processes” (Mintrom, 2019b, p. 307), and that research concerning policy entrepreneurship will contribute to guidance for advocacy practices, e.g. in climate policy and governance (Mintrom & Luetjens, 2017).

Section 2 describes who can be policy entrepreneurs, their motifs and strategies and factors explaining success or failure. But first, I will present a critique of conventional research on policy entrepreneurs and call for more critical analytic as well as normative research on policy entrepreneurs, which I argue is needed for policy entrepreneurs to be able to contribute to a just transition.

1.3. A Call for Critical Research on Policy Entrepreneurs

Conventional research on policy entrepreneurs assumes that they are a political fact, taking place anyway, whichever our thinking about it is, in democratic or non-democratic regimes. Thus, the model of policy entrepreneurship fails to address issues like legitimacy, accountability and justice – issues paramount in the debate on just transition. This paper argues that a different, more critical analytic and normative approach should be added to the research on policy entrepreneurs. What impacts do policy entrepreneurs have on democracy and democratic policy processes? Are they good or bad for democracy? Weiss (1980) argues that many political decisions are taken in non-transparent and complex ways. Many small decisions taken by different persons and organizations taken together form a larger decision. Thus, policy actors without formal decision-making power, like policy entrepreneurs, can take the role as political decision-makers.

Policy entrepreneurs are often part of the elite in their specific field, and their role in the policy process can be criticized (Caramani, 2017; Müller, 2023). This is particularly so since an important strategy of policy entrepreneurs to reach their aims of structural entrepreneurship is to use factual and scientific information in a smart and strategic way (Boasson & Huitema, 2017), either by manipulating who gets what information if information is distributed asymmetrically and information is scarce (Moravcsik, 1999; Zahariadis, 2003), or by strategic manoeuvring, such as providing as little information as possible to one’s likely opponents (Mackenzie, 2010). This may influence procedural justice and legitimacy as well as accountability in policy processes and decision-making. Other key activities of policy entrepreneurs like problem framing and policy formulation are always political. Framing is the most important strategy for a policy entrepreneur, both in structural and cultural-institutional entrepreneurship (Boasson & Huitema, 2017). Framing and the creation of meaning is important for making people positive to the ideas coming from the policy entrepreneur, and negative to existing and competing policy or governance arrangements (Fligstein, 2001). What is going on in the problem stream frames the conditions for coupling to the policy stream and the politics stream done by policy entrepreneurs (Knaggård, 2015). How a condition is framed as a public problem influences how we think about the problem, which enables coupling to certain public policies, but not to others (Weiss, 1989). As Copeland and James (2014, p. 3) put it, framing is about “strategic construction of narratives that mobilize political action around a perceived policy problem in order to legitimize a particular solution”. Framing also “involves the manipulation of dimensions to represent solutions to specific problems as gains or losses” (Zahariadis, 2003, p. 156). Most policy entrepreneurs are not elected politicians, which raises questions about their agency giving the impression of an elitist or technocratic approach, leading to opacity in policymaking. If there is lack of transparency, the agency and power of policy entrepreneurs in the policy formulation process conceals the authority that shapes how public problems and policies are framed and defined, which decreases accountability and legitimacy. Just like lobbyists, experts and intermediaries, policy entrepreneurs should be confronted with the challenge of generating legitimacy, political accountability and justice of their actions and the implementation of their targeted policy change (cf. Peters & Pierre, 2006; Müller, 2023; von Malmborg, 2023a, 2023b).

In the wake of the Reagan liberalization of the US administration and economic policy, Bellone and Goerl (1992, p. 131) claimed that agency of public sector policy entrepreneurs “need to be reconciled with the fundamental democratic values of accountability, citizen participation, open policymaking processes, and concern for the long-term public good (stewardship)”. Their call was immediately criticised by Terry (1993, p. 395), who claimed that public sector policy entrepreneurs “seems to be a wolf in sheep’s clothing” – that they do not exist. However, contemporary research shows plenty of evidence of public sector policy entrepreneurs, such as the European Commission, the Council of the EU, the European Central Bank, national, regional or local governments and authorities (e.g. Edler & James, 2015; Herweg, 2016; Petridou, 2017; Mintrom, 2019a; Pircher, 2020; Zeilinger, 2021; Heldt & Müller, 2022; Herweg & Zohlnhöfer, 2022; von Malmborg et al., 2023a; von Malmborg, 2024a). Since the debate in the 1990s, only three studies of public sector policy entrepreneurs have been addressing aspects of democracy, focusing on accountability of individual agency employees in US state government (Grady & Tax, 1996), legitimacy of Swedish local authorities (Olausson & Wihlborg, 2018), and accountability of the European Central Bank (Heldt & Müller, 2022) as policy entrepreneurs. Some scholars admit that policy entrepreneurs can have implications regarding trust, legitimacy and accountability (Green, 2013; Brouwer & Huitema, 2018; Faling et al., 2018; Müller, 2023; Becker, 2024), but they did not analyse it. This critical perspective is not included in the future research agendas suggested on policy entrepreneurs in general (Petridou & Mintrom, 2021), and policy entrepreneurs in climate governance (Boasson & Huitema, 2017; Green, 2017; Mintrom & Luetjens, 2017).

In all, there is a lack of systematic research on whether the presence of policy entrepreneurs have a positive or negative impact on democracy and different democratic values and norms (cf. von Malmborg, 2023a, 2023b). Thus, I call for critical policy studies on the interests and agency of policy entrepreneurs from different sectors in establishing “a monopoly on political understandings concerning not only the policy of interest, but also the institutional arrangement that reinforces that understanding” (Baumgartner & Jones, 1993, p. 6). Relevant questions are:

What impact do policy entrepreneurs have on democracy and democratic policy processes?

How can a policy entrepreneur be held accountable for a certain problem framing and/or a policy proposal?

How are problem narratives and policy options proposed by policy entrepreneurs justified?

Who are allowed to participate in a policy process dominated by policy entrepreneurs?

Does the policy option proposed by a policy entrepreneurs cater for justice in treating the public problem?

To guide such systematic research, this paper aims at outlining a conceptual framework for critical analytical as well as normative research on the policy entrepreneur–democracy nexus (section 4). As input to sketch and explain the framework, the paper draws on theories on the related lobbyism–democracy nexus (section 4) and views on the democratic norms of legitimacy, accountability, and justice according to liberal as well as deliberative democratic theory (sections 5).

When dealing with democracy and advocacy of policy entrepreneurs, it is important to remember whether we are doing this as policy analysts, trying to understand and study how things work in practice in an analytical-descriptive manner, or as political philosophers, trying to imagine how things should work in a normative-prescriptive manner. The interaction between the two fields can be very strong (Deutsch, 1971). This paper primarily focuses on the normative-prescriptive perspective – the norms that policy entrepreneurs should adhere to. But a normative theory cannot only build on theoretical reasoning. What happens in reality is important. In addition to the normative aspects presented with the conceptual framework, the paper presents results from empirical studies of actual impacts of policy entrepreneurs on democratic climate governance in two cases (see section 6): (i) policy processes on innovative climate legislation in the EU for decarbonizing maritime shipping, and (ii) policy processes on a radical shift of climate policy and governance in Sweden. For this reason, theories on democratic climate governance and the environment–democracy nexus are reflected upon in section 3. The empirical cases are not used to conclude that all policy entrepreneurs have impacts on democracy but serve to illustrate how they can impact democracy and thus as input to develop theory on how to understand strategies and impacts of policy entrepreneurs and further a normative framework on how they should act in democracies.

The paper will contribute conceptually and empirically to the literature on policy entrepreneurs (summarised in section 2), by addressing the dual relationship of policy entrepreneurs to democratic policymaking. This is an important new topic of the research agenda on policy entrepreneurship. It also intends to contribute to the literature on democratic climate governance for a just transition, as well as democracy theory in general. As for climate governance theory and democracy theory, the paper adds knowledge about a certain category of powerful policy actors so far neglected in the literature – policy entrepreneurs – that influence the just transition to climate neutrality, as well as governance in other policy areas.

2. What the Literature Tells Us about Policy Entrepreneurs and Entrepreneurship

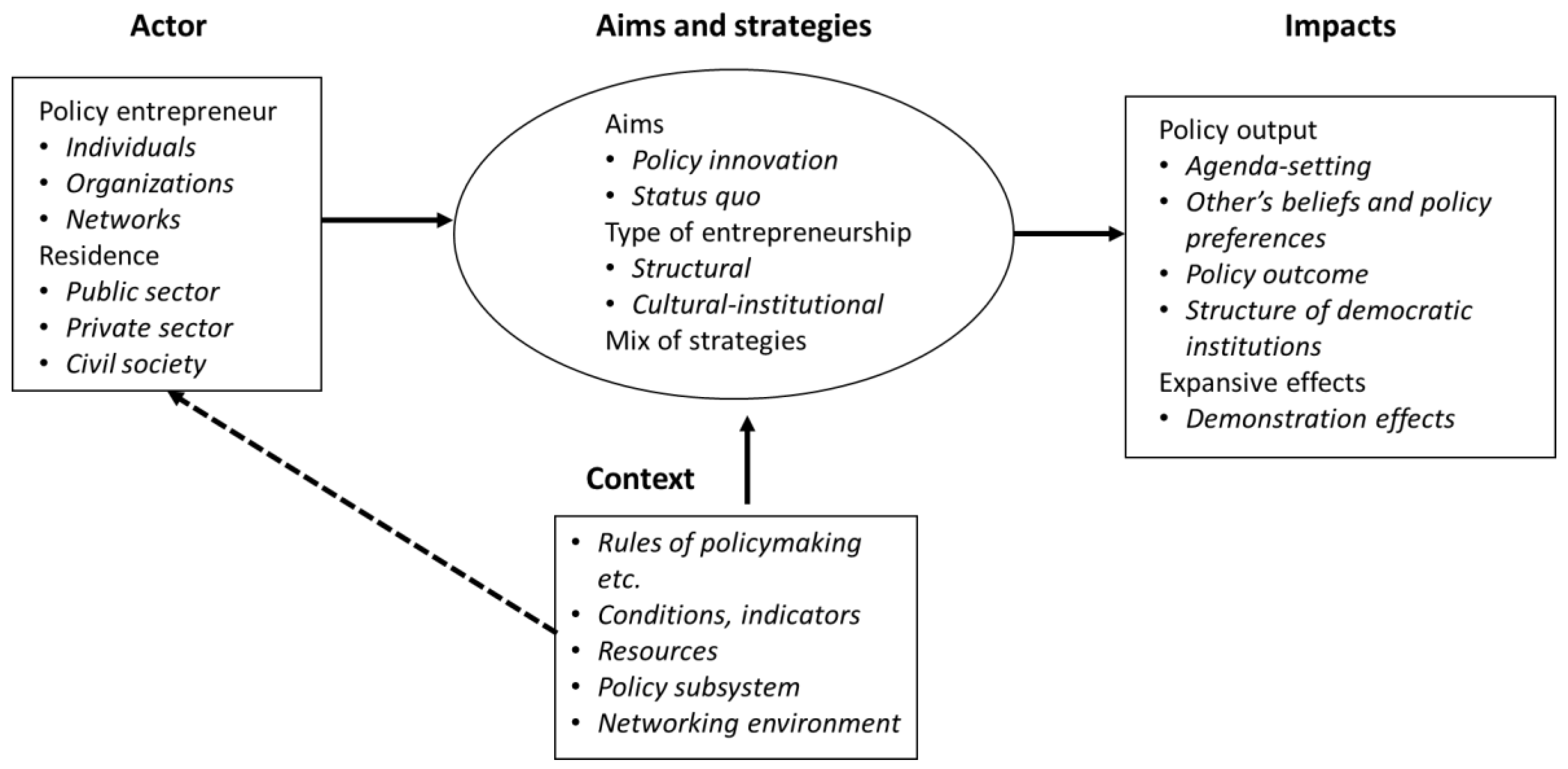

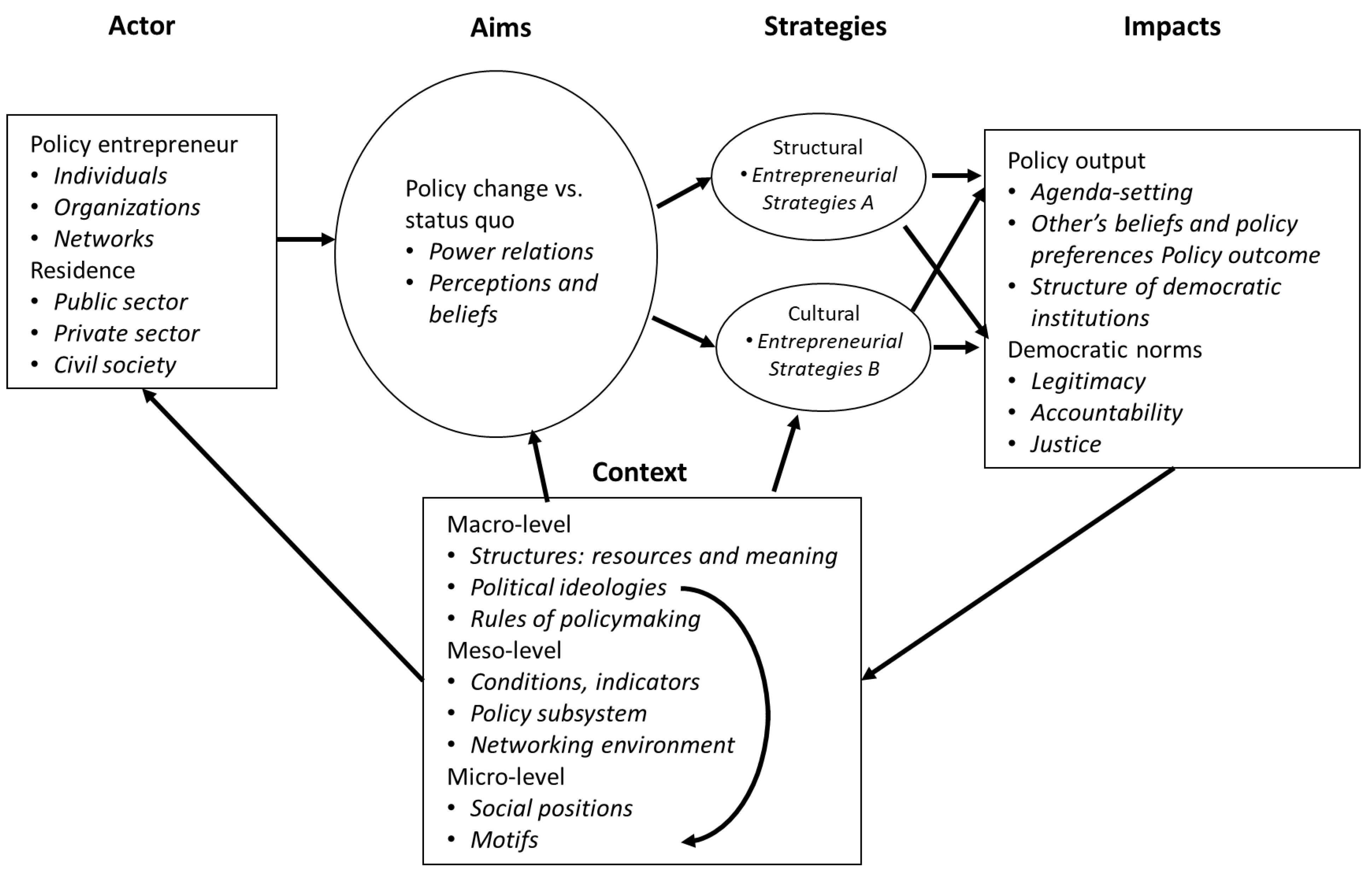

Figure 1 presents the conventional model of policy entrepreneurs, their strategies and outcomes, where strategies should be viewed as the causal mechanism that link actors to outcomes (Green, 2017). This model and its components are described in the remainder of this section.

2.1. Defining Policy Entrepreneurs

The policy entrepreneur concept has been accused of fuzziness, meaning different things to different scholars even within the same discipline (Cairney, 2013; Petridou, 2017; Arnold et al., 2023). Initially and yet in the US, only individuals were considered as policy entrepreneurs, but research on policy processes in the EU have added organizations as policy entrepreneurs. Thus, policy entrepreneurs include not only individuals – such as elected politicians, public officials, academics and experts – but also companies, business associations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), think tanks, other IGs, political parties and public institutions, e.g. the EC, the Council of the EU (Council), the European Central Bank, the European Investment Bank, or national, regional or local governments and authorities (Herweg, 2016; Petridou, 2017; Mintrom, 2019a; Liebe & Howarth, 2020; Pircher, 2020; Heldt & Müller, 2022; Herweg & Zohlnhöfer, 2022; Bürgin, 2023; von Malmborg et al., 2023a). Zito (2000, 2017), even refers to “collective entrepreneurship” in which advocacy coalitions act as policy entrepreneurs to formulate individual policies in a certain policy area. In all, policy entrepreneurs can come from the public and private sectors as well as civil society.

But what distinguishes policy entrepreneurs from other policy actors? Boasson and Huitema (2017, p. 1351) argue that “privileged actors in powerful positions deploy[ing] the regular tools at their disposal and merely do their job, they are not demonstrating entrepreneurship”. This is not to say that privileged persons or organizations in powerful positions, like cabinet ministers, EU commissioners, EU institutions or national governments, cannot be policy entrepreneurs. Policy entrepreneurship can be deployed by actors in and out of government at different levels, and in different domains if they are “persistent and skilled actors who launch original ideas, create new alliances, work efficiently or otherwise seek to ‘punch above their weight’” (Boasson & Huitema, 2017, p. 1344; Green, 2017). For instance, the current president of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen and former EU commissioner Frans Timmermans has been described as policy entrepreneurs for launching the European Green Deal in 2019 (Kreienkamp et al., 2022; Becker, 2024), and the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Federica Mogherini, acted as a policy entrepreneur and pushed for policy change in EU’s foreign and security policy (Sus, 2021). Schneider and Teske (1992) found that policy entrepreneurs often come from inside the political system, even from the government cabinet (Saetren, 2016). Similarly, Rabe (2004) found that policy entrepreneurs on US climate policy came from within the federal administration. In addition, partisan effects of Labour policy entrepreneurship have been identified for UK law and order policy (Staff, 2018) and UK education policy (Olsson Rost & Collinson, 2022). Thus, it is not far-fetched to view privileged actors in powerful positions such as elected politicians, political parties, governments and political executuves as policy entrepreneurs. In all, acting as a policy entrepreneur depends on a “set of behaviours in the policy process, rather than a permanent characteristic of a particular individual or role” (Ackrill & Kay, 2011, p. 78).

2.2. Motifs and Strategies of Policy Entrepreneurs

Drawing on Kingdon’s definition of policy entrepreneurs, most scholars have assumed that they are instrumentally rational (Bakir & Jarvis, 2017), motivated by a “desire for power, prestige and popularity, the desire to influence policy, and other factors in addition to any money income derived from their political activities” (Schneider et al., 1995, p. 11) or “satisfaction from participation, or even personal aggrandizement” (Kingdon, 2002, p. 123). However, policy actors are rather boundedly rational and motivated by cognitive rationality, i.e. their beliefs and ideas (Zahariadis, 2007; Bakir, 2009). Policy entrepreneurs may engage in policy advocacy to prevent opponents with conflicting beliefs from securing ‘evil’ policies, triggering a ‘devil’s shift’ (Sabatier & Jenkins-Smith, 1999). Arnold (2022, p. 26) argues that “[o]ppositional factors, by triggering a value-laden, devil shift-influenced fear of a threat to a desired policy goal, can catalyze policy entrepreneurship”.

The strategies employed by policy entrepreneurs are the lines of action taken to reach their aims, the latter which fall in two categories (Boasson & Huitema, 2017):

Structural entrepreneurship: acts aimed at overcoming the structural barriers to enhance governance influence by altering the distribution of formal authority and factual and scientific information; and

Cultural-institutional entrepreneurship: acts aimed at altering or diffusing people’s perceptions, beliefs, norms and cognitive frameworks, worldviews, or institutional logics.

The literature tells that policy entrepreneurs work in an energetic, sometimes activistic, strategic manner with the intention to innovatively change political alignments (Roberts & King, 1991; Capano & Galanti, 2021). Analysing the scholarly literature, Aviram et al. (2020) identified 20 strategies and three traits of PEs: trust building, persuasion, and social acuity. Theses may vary with respect to target audience, level of government at which the PEs operate, sector, and PEs’ professional roles, timing, number and types of actors involved, relationship to development of international politics etc. Brouwer and Huitema (2018) proposed four categories of strategies (

Table 1):

For structural entrepreneurship, three strategies are particularly important: (i) creating and working in networks and advocacy coalitions, (ii) strategic use of decision-making processes, and (iii) strategic use of information (Boasson & Huitema, 2017). Through networking, a policy entrepreneur learns the worldviews “of various members of the policymaking community” (Mintrom, 1997, p. 739), which enables the policy entrepreneur to persuade policy actors with high levels of legitimacy or authority to join in (Wihlborg, 2018). As for strategic and smart use of decision-making procedures and venues, this relates to timing and thus launching the policy idea when there is an open policy window (Kingdon, 1984). Finally, policy entrepreneurs can reach their aims by assembling new evidence and make novel arguments (Dewulf & Bouwen, 2012), carrying ideas (Swinkels, 2020) that serve as ‘coalition magnets’ (Béland & Cox, 2016) to convince an appropriately powerful coalition of supporters to back the proposed changes (Boasson & Huitema, 2017; Mintrom & Luetjens, 2017). This is done either by manipulating who gets what information, if information is distributed asymmetrically and information is scarce (Moravcsik, 1999; Zahariadis, 2003), or by strategic manoeuvring, such as providing as little information as possible to one’s likely opponents (Mackenzie, 2010).

As for cultural-institutional entrepreneurship, making people positive to the ideas coming from the entrepreneur, and negative to existing and competing policy or governance arrangements, framing of problems and policy options is the most important strategy (Boasson & Huitema, 2017). Framing is about “strategic construction of narratives that mobilize political action around a perceived policy problem in order to legitimize a particular solution” (Copeland & James, 2014, p. 3). To persuade others, policy entrepreneurs must consider the perspectives of various actors and create meanings and frames that appeal to them (Fligstein, 2001).

Importantly, Braun et al. (2024) in a recent comparative study found that policy entrepreneurs employ different strategies over time when interacting with their immediate and wider contexts in attempting to foster policy change – they co-create with policymakers to shape their ecosystems and society at large. This echoes the critique of mainstream research on policy entrepreneurs, that “in contrast to widely held view that policy entrepreneurs promote ideas and operate outside decision-making processes (Mintrom, 2000), policy entrepreneurs are endogenous to policymaking processes” (Bakir & Jarvis, 2017, p. 469). Policy entrepreneurs deploy ‘outsider tactics’ by shaping public discourse on problems and policy solutions, or ‘insider tactics’ by working with policymakers to design regulations (Gabehart et al., 2022; Tosun et al., 2023).

2.3. Success and Failure of Policy Entrepreneurs

Successful policy entrepreneurship is defined in different ways. For some, a policy entrepreneur is successful if the advocacy leads to changes in other policy actors’ beliefs and policy preferences (Teske & Schneider, 1994). This can be compared to policy-oriented learning (Sabatier, 1988). For others, a policy entrepreneur is successful if influencing agenda-setting in such a way that the policy entrepreneur’s pet issue is considered by policymakers (Mintrom, 1997; Mintrom & Vergari, 1998). Yet another view is that policy entrepreneurs are successful if they have actual influence on policy and governance arrangements (Boasson & Huitema, 2017), e.g. adoption of specific policy measures the policy entrepreneur sought (Arnold et al, 2017; Crow, 2010; Mintrom, 1997, 2000). What is deemed success depends on the aim of the policy entrepreneur agency. Green (2017, p. 1478) also suggests to analyse expansive effects, “looking beyond the specific goal or target of an individual entrepreneur”, to examine “the extent to which entrepreneurship influenced a larger set of actors than originally intended, or helped catalyze broader effects”. Examples include demonstration effects of private regulators in voluntary markets, normative changes and changes in governance practices. However, the latter two are considered basic objectives of public policy advocacy (Baumgartner & Leech, 1998) and have been included in traditional goals of policy entrepreneurs since the 1990s (e.g. Teske & Schneider, 1994; Mintrom, 1991), why I only consider demonstration effects to be an expansive effect.

Mintrom and Norman (2009) assume that success is more likely for a policy entrepreneur who has more characteristics that define her as such, or who deploys entrepreneurial strategies with greater frequency or intensity (cf, Binderkrantz & Krøjer, 2012). Most policy entrepreneurs strive for policy innovation, which consists of initiation, diffusion, and the evaluation of effects that such innovations create, the latter requiring analytical capacities (Jordan & Huitema, 2014). These challenges are central to the work of policy entrepreneurs. It is their willingness to use their positions for leverage and for aligning problems and solutions that increase the likelihood of policy change (Mintrom & Norman, 2009). The ability of policy entrepreneurs to successfully promote policy innovation also depends on their skill at identifying relevant competencies, developing and effectively deploying them (Considine et al., 2009; Meijerink & Huitema, 2010). In addition, a successful policy entrepreneur must understand the concerns of actors they seek to persuade, use social acuity to build teams, networks, and coalitions, be knowledgeable to strategically disseminate information, and be organising, corresponding to political activation and involving civic engagement (Mintrom & Norman, 2009; Aviram et al., 2020; Arnold, 2021). Anderson et al. (2020) adds that the influence of policy entrepreneurs lies not only in their ability to define problems and build coalitions, but also in their ability to provide new and reliable information to elected officials.

Categorizing characteristics, goals and strategies of successful policy entrepreneurs, Arnold (2021) suggests three archetypes. Activists are highly active and display many entrepreneurial characteristics and deploy a wide range of strategies to reach several policy goals. Advocates have similar characteristics as activists, but are less active, using fewer strategies and focus primarily on one ambitious policy goal. Concerned citizens manifest rather few characteristics and tend to lobby for restrictive/ambitious measures with relatively little facility or effort. Activists and advocates were found to be successful, while concerned citizens had no or negative impact. An interesting implication of is that “it may not be necessary for an actor interested in securing a policy goal to go ‘all in’ as an activist, deploying a wide range of strategies and pursuing a range of related goals. Policy change can potentially be achieved through more modest, accessible advocacy” (Arnold, 2021, p. 985).

2.4. Context of Policy Entrepreneurship

Success is not only determined by the characteristics, actions and strategies of policy entrepreneurs, but also the context which shapes their actions. Bakir and Jarvis (2017) have criticised mainstream research on policy entrepreneurs for focusing only on the meso-level context of policy change (i.e. the immediate context of a particular policy) in policy formulation, and to dismiss the macro and micro contexts within which a policy entrepreneur is embedded. They demonstrate that context impacts policy entrepreneurship and institutional entrepreneurship, at least in the public sector. Agency of policy entrepreneurs is ”most likely to generate policy and institutional changes when they are reinforced by complementarities arising from context-dependent, dynamic interactions among interdependent structures, institutions and agency-level enabling conditions” (Bakir & Jarvis, 2017, p. 465). Acknowledging Giddens’s (1979) concept of ‘duality’ between agency and structure, policy entrepreneurs and context “should not be viewed in isolation but as linked through strategy” (Zahariadis & Exadaktylos, 2016, p. 62).

The macro-level context consists of formal and informal institutions, i.e. a relatively stable collection of rules and practices, embedded in structures of resources and meaning that enable and constrain policy entrepreneur agency (cf. March & Olsen, 2008). The micro-level context includes the social position and motifs of the policy entrepreneur, who, be they individuals or organizations, can occupy multiple social positions with different identities and motifs in different parts of the policy process, e.g. as decision-maker, academic, framer and broker. This enables policy entrepreneurs to work in different ideational realms, programmes, discourses, building coalitions and generating consensus (Bakir, 2009).

3. Theories on the Environment–Democracy Nexus

The climate crisis poses a major challenge to governance and democracy. Failures in contemporary climate governance expose a systemic failure in liberal democracy (Goodman & Morton, 2014). The political theory of ecological democracy, building on the thoughts of deliberative democracy where citizens use public deliberation to make collectively binding decisions (e.g. Dryzek, 1990, 2000; Held, 2006), emerged in the 1990s when liberal democracy and cosmopolitanism appeared to be on the rise. It sought to critique and institutionally expand the coordinates of democracy – space, time, community, and agency – to bring them into closer alignment with a cosmopolitan ecological and democratic imaginary. In the 2010s, a second wave of ecological democracy emerged, reflecting a significant shift in critical normative horizons, focus and method (Eckersley, 2019). It has connected ecology and democracy through local participatory democracy from a more critical communitarian perspective. Willis et al. (2022) conclude that deliberation-based reforms to democratic systems, including but not limited to deliberative mini-publics, are a necessary and potentially transformative ingredient in climate action.

Besides ecological democracy,

environmental democracy has also developed as a political theory, drawing in large on the thoughts of liberal democracy (Held, 2006)

1. Environmental democracy revolves around reforming, rather than transforming, existing institutions of liberal democracy and capitalism. Environmental democracy thus resonates with ideas of green liberalism (Wissenburg, 1998) or liberal environmentalism (Bernstein, 2001) and is also more anthropocentric in its outlook (Arias-Maldonado, 2012).

The distinction between ecological and environmental democracy can help to categorize theories of the environment–democracy nexus (Pickering et al., 2020). Ecological democracy is more critical of existing liberal democratic institutions – particularly those associated with capitalist markets, private property rights and the prevailing multilateral system – and more ecocentric. Ecological democracy stresses the importance of ensuring that the interests of non-humans and future generations are represented in decision-making (Eckersley, 2004).

When compared with environmental democracy, ecological democracy tends to set more demanding normative standards, both in terms of environmental protection and democratic inclusion. However, the two concepts represent two ideal types along a spectrum, and hybrid accounts are possible. Some accounts of ecological democracy give greater prominence to the state (e.g. Eckersley, 2004), while others emphasize the transformative potential of civil society and discourse (e.g. Dryzek, 2000; Dryzek et al., 2006).

Despite their differences, political theories of ecological and environmental democracy are united by a shared interest in whether democratic processes can be compatible with strong environmental outcomes (Eckersley, 2019). Both emphasize “the need for transformative change, particularly by reconfiguring the relationships between local, national and global decision-making, and rendering public deliberation more inclusive of citizens’ voices and more attuned to environmental values and realities” (Pickering et al., 2020, p. 10).

Neither ecological democracy theory nor environmental democracy theory has proposed their own, specific considerations on different democratic norms, such as legitimacy, accountability and justice, referred to in the democracy literature and political debates. However, Dryzek and Stevenson (2011) outline some elements of governance in ecological democracy, including (i) public space, (ii) empowered space, (iii) transmission, (iv) accountability, (v) meta-deliberation, and (vi) decisiveness.

Biermann and Gupta (2011) propose a research framework on accountability and legitimacy in earth system governance, to which climate governance belongs. Their framework draws from both liberal and deliberative democratic theory. Global environmental change, like climate change, together with the resulting challenge of developing effective systems of climate governance, poses new challenges for securing the accountability and legitimacy of governance systems – globally, supranationally, nationally, and locally (cf. Biermann & Gupta, 2011). These challenges include (i) spatial interdependence, (ii) functional interdependence, (iii) scientific uncertainty and normative contestation, (iv) temporal interdependence (future generations), and (v) extreme events. For instance, accountability is affected by mismatches between those who seek to hold others accountable and those who are to be held accountable, the former which could be stakeholders in the global South, and the latter actors in the global North, including policy entrepreneurs (Dryzek & Stevenson, 2011). Functional interdependencies refer the diverse sectors of global production and consumption, which make the assessment of the accountability and legitimacy of rule-making dependent on the boundaries to be drawn around the ‘stakeholders’ included (Biermann & Gupta, 2011).

4. A Conceptual Framework for Critical Research on the Policy Entrepreneur–Democracy Nexus

Policy entrepreneurs are similar to lobbyists, and lobbyists can act as policy entrepreneurs. Scholars have shown interest in the role and impacts of lobbyists on democracy and democratic norms and values for some years, and proposals have been made of normative frameworks for regulation of lobbying (e.g. Bitonti, 2017a; Bitonti & Harris, 2017; Mollona & Faldetta, 2022; Bitonti & Mariotti, 2023). Critical studies of the relationship between policy entrepreneurs and democracy can learn from this area of research.

Critical research and analysis of should include analytical descriptions of reality and normative prescriptions of reality (cf. Bitonti, 2017a). The first part focuses on interest politics analysing the role and strategies of IGs influencing policymaking while the latter focuses on a political philosophy of policy entrepreneurship.

4.1. Politics of Interest

The reality of politics can be framed by conceiving the political society as a multiplicity of IGs competing for power or for the influence of those with power (Baumgartner & Jones, 1993). In this perspective, democracy itself would be the institutional formal framework where this competition takes place, a framework where political scientists would overcome appearances and formalities to study the actual behaviour of the various actors in a given political environment with an eminent concern for empirical evidence. This branch is not discussing whether policy entrepreneurship is good or bad, but analysing how it works, just assuming that policy entrepreneurship is a political fact, taking place anyway, whichever our thinking about it is, in democratic as in non-democratic regimes (cf. Bitonti, 2017a). But as argued in section 1.2, analytical-descriptive research on policy entrepreneurs should not only analyse the behaviour of the change agents, but also their impacts on democratic regimes, norms and principles.

Focusing on democratic regimes, policy analysts study the types of relationships of various organizations, IGs and experts with various institutions of modern democratic systems, such as legislative assemblies, executive branches, but also independent authorities, agencies, different public administration offices and supranational or intergovernmental bodies such as the European Commission, the Council of the European Union or the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (e.g. Kuyper et al., 2018; Bitonti, 2020; Herweg et al., 2023; Nohrstedt et al, 2023; Weible, 2023). Some of these studies also try to interpret the dynamics of the governmental process itself and the interaction between different IGs, institutional actors included (e.g. von Malmborg, 2021, 2022, 2023c, 2023d, 2023e, 2024a). Contemporary research on policy entrepreneurs and policy entrepreneurism (see section 2) falls in this category. These studies have come to various findings about the weight of specific actors or about the balance of power in a political environment, resulting in very different conclusions about the characteristics of modern democracy and its relationship with IGs as lobbyists or policy entrepreneurs, and experts. Elitism, epistocracy, pluralism, neo-corporatism, neo-pluralism or the policy networks theory are all examples of such diagnoses (Bitonti, 2017a; Christensen et al., 2023).

4.2. Political Philosophy of Democratic Policy Entrepreneurship

The second branch focuses on whether policy entrepreneurism is good or bad in our vision of an ideal democratic regime. According to Bitonti (2017a, 2017b), the answer to this question depends on the conception of the public interest adopted, as this shapes both the way democracy is conceived and the role of policy entrepreneurism, lobbying and expertise within it (Bitonti, 2020, 2021). He identifies five ideal–typical conceptions of the public interest: formal, material (populist), realist, aggregative (liberal) and procedural (deliberative). The aggregative and procedural conceptions are particularly important in discussions on climate governance and democracy since they relate to liberal environmental democracy and deliberative ecological democracy respectively. Given the increased growth of right-wing populist parties within the EU, which expressly want to tear up the EU’s recently decided climate legislation in the European Green Deal, the European Climate Law, and the Fit for 55 legislative package, it is also relevant to relate to the material, populist view of the public interest. Each conception can be associated with a particular vision of democracy, with particular beliefs on human epistemic conditions, anthropology, economic and institutional ideal designs. Out of five conceptions, two appear strongly against lobbying (the material and the procedural), one moderately against (the formal), one neutral (the realist) and one strongly supportive (the aggregative).

The aggregative conception of the public interest can be considered a liberal conception, supporting a limited amount of ethical content. Even if it stands out with ethical prescriptions and values (such as the equality of individuals and their freedom), it does so in a less demanding way than the material conception, without any claim on the Ultimate Goal or the Truth. It is quite relativistic, and only prescribes the aggregation and coexistence of various political visions and of various IGs in a political society (Rawls, 1993). It recognizes the existence of these different groups, and says it is a good thing that different opinions keep existing and oppose each other, according to a corporativistic, majoritarian liberal-democratic constitutional scheme (Lijphart, 1977, 1999; Guiliani, 2015). According to this conception, the public interest is represented by the rules of the game themselves, i.e. the competition of interests. This conception has a positive stance on stakeholder advocacy like policy entrepreneurship and lobbyism, deemed as a legitimate way to advance one’s interests in a democratic and open competition for consent, addressing both the actual decision makers and the grassroots at the base.

According to the procedural conception, public interest results from a procedure of rational deliberation taking place between rational actors, weighing the pros and cons of each option on the table, and reducing any possible bias to favour a final unanimous agreement on what is the best option. Only such an option can be deemed as being in the public interest. Evidently, the focus here is on the procedure of the consensualistic deliberation itself (Lijphart, 1977, 1999; Guiliani, 2015). It is an open-ended conception, which theoretically may go very far as concerns moral prescriptions. It is the conception embodied by the model of deliberative democracy (Dryzek, 2014). Here we find a strongly negative vision of stakeholder advocacy by policy entrepreneurs and lobbyists, as it would represent a channel of distortion and interference in front of a purely rational decision emerging from the deliberation process, taking place in an ideal discursive space (Habermas, 1984).

The material conception of the public interest focuses, as the name suggests, on content, not processes or rules. This view is associated with populism where one or more self-appointed interpreters have the answer to the ‘Only Truth’ or the ‘Ultimate Goal’. Individuals’ interests or rights may be sacrificed for the good of society (Popper, 1945). Populists are ideologically strongly negative to pluralism, and thus political advocacy in competition through lobbying and policy entrepreneurship, as it would negatively affect them as legitimate interpreters of the ‘truth’. They themselves have the answer to what is in the public interest.

Whether policy entrepreneurs are good or bad for democracy is theoretically a question of normative approaches to democracy and the conception of the public interest. The aggregative conception of the public interest, which is related to liberal environmental democracy, has a positive attitude towards lobbyists and policy entrepreneurs, regarding them as a democratic right. The existence of policy entrepreneurs is seen as a legitimate means of promoting their interests in a democratic and open competition for consent, which targets both the actual decision-makers and the grassroots (cf. Bitonti, 2017a). On the contrary, the procedural conception of the public interest, related to deliberative ecological democracy, has a strongly negative view of lobbying and policy entrepreneurship, regarding them as a distortion of and undue interference with the democratic process, and focuses its attention on the power of IGs, who are ‘farm traders’ in political advocacy and corrupt actors twisting the democratic game to their own interests, using resources to influence or distort the decision-making process, instead of a purely rational decision that comes out of a deliberative process, and that takes place in an ideal discursive space. The material conception of the public interest, related to populism, views policy entrepreneurs negatively as it is averse to pluralism that threatens populists’ self-proclaimed interpretive preference for the Only Truth. However, van den Dool and Schlaufer (2024) have identified studies on policy entrepreneurs in autocracies, suggesting that future research ought to bring existing literature on authoritarianism and authoritarian politics into policy process research to test existing and new hypotheses.

4.3. Fundamental Norms in the Framework

According to Bitonti (2017a), the aggregative conception of the public interest is the only one that seems to engage positively in an ethical justification of the rules of modern liberal democracy in constructive terms. It is from this view that Bitonti draws theoretical lessons for a normative regulation of lobbying in developed modern liberal democracies, pointing out four fundamental principles that are particularly plausible for such a framework: (i) accountability, (ii) transparency, (iii) openness and (iv) impartiality (Bitonti, 2017a). Of these, accountability is overarching and the other three contribute to fulfilling accountability. By accountability, Bitonti means the obligation of decision-makers and lobbyists to justify their proposals and decisions to the public. To achieve this, decision-makers and lobbyists need to be transparent about how they develop and formulate their policy proposals, what basis was used, and the access of those concerned to this information on an equal basis. There must also be openness and impartiality in the matter of contributing to political decisions. Parties concerned must be able to communicate with decision-makers and lobbyists without discrimination and corruption (cf. Rothstein, 2009).

But with a broadened perspective on who is undertaking political advocacy

2, and with an increasing interest in deliberative democracy in environmental and climate policy research and political debates, these norms are also valid for analyzing the role of policy entrepreneurs in modern democracies in relation to the procedural conception of the public interest and deliberative (ecological) democracy. These norms are important in deliberative democracy, but sometimes with other connotations. In light of research on climate governance and democracy (e.g. Biermann & Gupta, 2011; Kuyper et al., 2018; Pickering et al., 2020), accountability and its sub-norms transparency, openness and impartiality need to be supplemented with legitimacy and justice as normative principles. Legitimacy, which, i.a., includes perspectives on justice, is furthermore a central norm in general democracy research (Lipset, 1959; Beetham, 1991; Scharpf, 1999; Schmidt, 2006; O’Donnell, 2007; Rothstein, 2009). This is consistent with the view of Mollona and Faldetta (2022), whose framework for analysing justice in relation to lobbyism includes organizational and normative justice that relates to the legitimacy and accountability of policy actors. The former includes subjective distributive justice and descriptive procedural and interactional justice, while the latter draws on both Rawls’s liberal and Habermas’s deliberative ethics, as well as utilitarian and Kantian ethics. With these additions, the conceptual framework for analysing and providing norms for the policy entrepreneur–democracy nexus becomes broader and includes different ethics for critically analysing policy entrepreneurship and its impact on democratic norms. Utilitarian and Kantian ethical principles are suited to provide [different] assessments of the material content of policy entrepreneurs’ strategic agency, while Rawlsian and Habermasian ethical principles support the assessment of the context in which policy entrepreneurship is carried out (cf. Mollona & Faldetta, 2022). Bitonti also seems to agree, as he recently revised his normative framework of lobbying to include equal access and accountability for decision makers (Bitonti & Mariotti, 2023), drawing on philosophies of open government (Lathrop & Ruma, 2010) and deliberative democracy (Habermas, 1996).

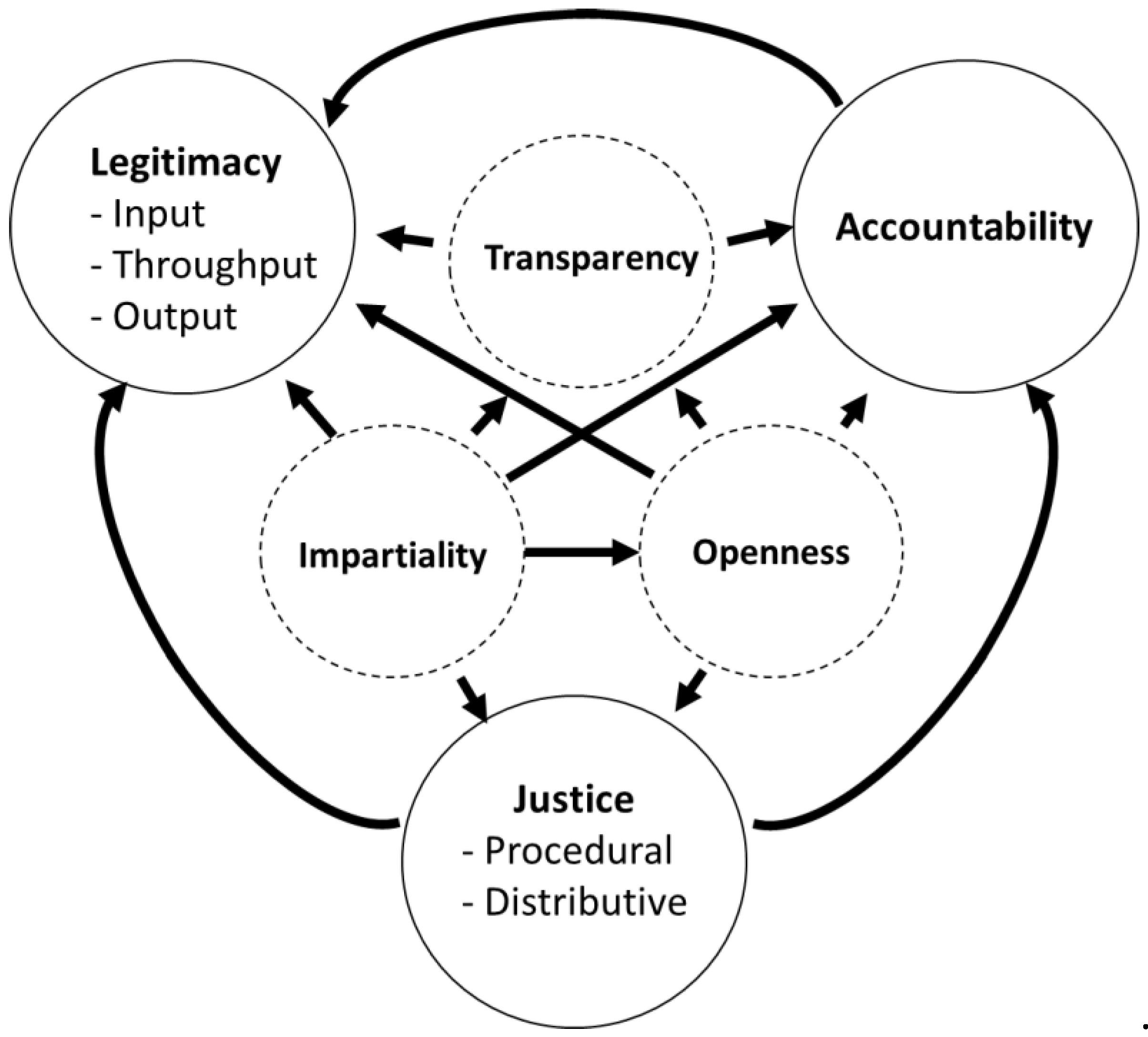

Against the above background, it is suggested that critical research on the role of policy entrepreneurs in and impact on liberal and deliberative democracies should analyse the relationships of policy entrepreneurs to six interrelated democratic norms and principles: (i) legitimacy, (ii) accountability, (iii) transparency, (iv) openness, (v) impartiality and (vi) justice (

Table 2). Of these, researchers on climate policy and democracy as well as liberal and deliberative democracy assert that legitimacy and accountability are overriding (cf. Lijphart, 1977; Held, 2006; O’Donnell, 2007; Black, 2008; Neyer, 2010; Biermann & Gupta, 2011; Bäckstrand et al., 2018; Kuyper et al., 2018; Müller, 2023). With an increased focus on climate justice in the policy debate, justice could be seen as an overarching norm, but justice, in the form of procedural justice and distributive justice, is often seen as norms that contribute to legitimacy and accountability. Justice and the other three norms and principles are therefore seen as subcategories that contribute to legitimacy and accountability, although justice can be said to have an intermediate position.

Figure 2 illustrates the interlinkages between legitimacy, accountability and justice, as well as transparency, openness and impartiality.

Legitimacy and accountability concerns are central to governance but are not confined to non-regulators or quasi-regulators (i.e. non-governmental actors performing governmental functions). However, they should be extended to policy entrepreneurs and other actors influencing public policy, “who in much broader terms are seen as exercising significant amounts of power over those both inside and outside organizations, including for profit corporations” (Black, 2008, p. 141). Legitimacy and accountability are distinct communicative, dialectical relationships which are socially and discursively constructed, and which are contested. Accountability is a route through which pragmatic and moral/normative legitimacy claims are validated (Hood et al., 1999). Accountability relations are a critical element in the construction and contestation of legitimacy claims by decision-makers and policy entrepreneurs, respectively to those affected by politics and policies, as they are how the various actors seek to ensure that their legitimacy claims are met and that their evaluations of the legitimacy of those in power are valid (Black, 2008).

In critical studies of policy entrepreneurs, one should thus focus on the policy entrepreneurs’ legitimacy and accountability, but also how their strategies and agency affect the legitimacy and accountability of other policy actors and democratic institutions, as well as how the legitimacy of a certain policy and policy instruments is affected. The conceptual framework suggested is intended to be applicable in both liberal and deliberative democracies. However, liberal democracy is hegemonic and policy entrepreneurs are mainly to be found in liberal democracies. Thus, empirical research will focus on policy entrepreneurs in liberal democracies, although part of the governance process may be deliberative.

5. Reflections on Central Norms and Principles in the Framework

5.1. Legitimacy

Legitimacy is a multifaceted concept, with different connotations depending on theoretical perspectives on democracy. Legitimacy has been defined as “a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions” (Suchman, 1995, p. 574; Scott, 2001). Being socially constructed, legitimacy claims can be contested by those evaluating political regimes, policies and policy entrepreneurs. Thus, legitimacy lies as much in the values, interests, expectations, and cognitive frames of those who are perceiving or accepting the governance regime, a policy entrepreneur, or a policy, as they do in the regime, policy entrepreneur or policy itself (cf. Black, 2008). It can differ significantly across time and space, and between actors, systems, and contexts. Moreover, different people’s perceptions of whether a policy entrepreneur or policy is legitimate are not necessarily based on the same types of evaluations. A regime or a policy that is deemed legally valid must not be legitimate. Thus, “identifying the ‘legitimacy’ of governance regimes or organizations within them, trying to do so by identifying legal validity will often be irrelevant, or at least unproductive” (Black, 2008, p. 144-145). In addition, Black argues that not all organizations will be perceived as legitimate in performing political roles in policy processes. This implies that legitimacy is particularly relevant when considering the role of non-state policy entrepreneurs.

In liberal democracy, legitimacy focuses on social credibility and acceptability, including (i) to what extent policy regimes, policies and policy actors conform to estblished rules, (ii) the exercise of power is justified by reference to the beliefs of both majorities and minorities (both of which can be represented by policy entrepreneurs), and there is evidence of support or consent from the minority, (iii) openness and a fair, impartial and unbiased opportunity for impacted citizens and other stakeholders to participate in the policy process, and (iv) the ability of the political system and/or policy instrument proposed by a policy entrepreneur to solve collective problems for citizens in a just way (Lipset, 1959; Lijphart, 1977, 1999; Barker, 1980, Beetham, 1985, 1991; Scharpf, 1999; Rothstein, 2009; Schmidt, 2006, 2013). In policy analysis, the model of Scharpf (1999) and Schmidt (2006, 2013), differentiating between input, throughput and output legitimacy is prevailing.

In deliberative democracy, “legitimacy means that there are good arguments for a political order’s claim to be recognized as right and just; a legitimate order deserves recognition” (Habermas, 1979, p. 178). The centrality of this view is that the political order consists of rules and procedures that revolve around the requirement that collective decisions be criticized and defended with reasons and good arguments. Later theorists of deliberative democracy expanded the view, that the outcomes of a political regime are legitimate to the extent they receive reflective assent through open participation in authentic deliberation by all those subject to the decision in question (Cohen, 1989; Knight & Johnson, 1994). In a similar manner, Benhabib (1996, p. 68) claims that “legitimacy in complex democratic societies must be thought to result from the free and unconstrained deliberation of all about matters of common concern” (highlight added). This focus on participation of all has been criticized by other scholars of deliberative democracy, since in real-world political deliberations, not all of those affected appear to participate (Shapiro, 1999; Dryzek, 2001). They argue that deliberative democracy cannot live up to its own standards of legitimacy, and thus, that legitimacy should not be a value and norm. The same holds true for private governance. Bäckstrand et al. (2018, pp. 346) claims that “multi-stakeholder participation was long hailed as the ‘gold standard’ of legitimate private rule-making”, ideas originating from deliberative democratic theory, with its focus on stakeholder participation and unconstrained dialogue (Stevenson & Dryzek, 2014). However, more empirically oriented scholars increasingly question the validity of this ‘inclusiveness paradigm’, pointing at the limited deliberative capacity of private multi-stakeholder governance (Schouten et al., 2012). Other theorists have elaborated the view of legitimacy in deliberative democracy, that a part of exercising legitimate democratic authority is a requirement for politicians, administrative agencies, and appointed experts to justify and explain their reasons and demonstrate that their demands can reasonably be expected to serve the common interests of free and equal citizens (Gutmann & Thompson, 1990; Cohen, 1996; King, 2003). As mentioned, Neyer (2010) argues that this focus on right to justification, rather than democracy, would be the basic principle to assess policy and political actors in deliberative democracy, as it helps to increase legitimacy and answers many questions inherent in the concept of accountability.

In summary, the main difference between the liberal and deliberate democracy perspectives on legitimacy lies in the view of who should be involved on impartial grounds in the ‘open’ policy process and thus able to express their views and concerns; only those affected by a policy or everyone concerned, in what spatial and temporal scope, citizens, humans or even non-humans?

5.2. Accountability

Accountability is an important mechanism to create legitimacy for the agency of policy entrepreneurs in liberal democracies (Kuyper et al., 2018; Heldt & Müller, 2022). It covers a moral and institutional liability to publicly justify actions in such a way that decision-makers and policy entrepreneurs can be evaluated, judged and held ‘politically’ accountable in front of the public for their performance or behaviour related to something for which they are responsible (Filgueiras, 2016, 2020; Müller, 2023). Accountability relationships are a “critical element in the construction and contestation of legitimacy claims by both policy entrepreneurs and legitimacy communities, as they are the means by which legitimacy communities seek to ensure that their legitimacy claims are met, and that their evaluations of the legitimacy of regulators are valid” (Black, 2008, p. 149).

Political accountability was not an important norm in early writings on deliberative democracy theory (Peters & Pierre, 2006). Due to limited oversight capacity of most legislatures in reality, Hunold (2002) proposed a deliberative model of bureaucratic accountability that would have significance beyond public administration for the study of democracy more generally. It focuses on accountability through public deliberation, where it is a challenge to link administrative institutions and their decisions to “interlocking and overlapping networks and associations of deliberation, contestation, and argumentation” (Benhabib, 1996, p. 74; Dryzek, 1990). Hunold’s model builds on three concepts: publicity, equality and inclusiveness. Publicity demands that administrative agencies transparently release proposed rules for public discussion and criticism. Deliberative democracy requires that citizens participate based on equality with administrative officials and technical experts such as policy entrepreneurs. In practice, this means that “all participants of policy deliberations should have the same chance to define issues, dispute evidence, and shape the agenda” (Hunold, 2002, p. 158). For this to happen, there should be a means of compensating weaker participants for serious power disparities, e.g. by providing opportunities for education and preparation on policy issues (Fiorino, 1990; Mitchell, 2011). Finally, inclusiveness, were fairness and impartiality of representation and democratic accountability hinge on collective decision-making processes being open to all citizens. To Dryzek and Stevenson (2011), questions of inclusion and exclusion are prominent regarding accountability and legitimacy in deliberative democracy and means that the ‘empowered space’ of political decision-making is held accountable to the ‘public space’ of deliberation. Who decides who is to be included in the ‘empowered space’ of decision-making? Whose voices carry more weight in the ‘public space’ of deliberation?

Accountability in liberal democratic theory does also focus on publicity, equality and fairness, but in terms of transparency, openness and impartiality (Bitonti, 2017a) as principal-agent accountability between the elected politicians and the public. In comparison to the deliberative model, the liberal model champions the probing of volitions among a smaller number of affected groups and actors. While accountability in liberal democracy is based on pluralist adversarial norms and more closed ‘open’ structures of interest representation, accountability in deliberative democracy champions collaboration and inclusiveness of more, sometimes all actors. This difference is important when it comes to climate governance.

Climate governance increasingly includes different type of actors; states, local government, bureaucracies, companies, NGOs and other IGs. Accountability is treated differently in different organizations, which calls for a distinction of internal and external accountability (Keohane, 2003). In internal accountability, the “principal and agent are institutionally linked to each other; and in external accountability, those whose lives are impacted, and hence who would desire to hold to account, are not directly (or institutionally) linked to the one to be held to account” (Biermann & Gupta, 2011, p. 1857). Policy entrepreneurs, being companies, business associations, think tanks or NGOs are self-selected, and there are, unless they are elected politicians or political parties, no demos available to hold them accountable. For these reasons, “principal-agent accountability [in relation to the public] – the main mechanism in liberal democracies – does not work in this context” (Bäckstrand et al., 2018, pp. 346). Thus, transparency is often suggested as an alternative, where transparency can breed accountability in private governance through (i) market pressures, (ii) discourse and (iii) self-reflection. Civil regulation of transparency, fitting ecological democracy, would permit the public to hold private sector and civil society policy entrepreneurs to account for their policy framings and policy proposals (cf. Newell, 2008; Etzioni, 2010). A less coercive model, fitting policymaking in liberal environmental democracies, is based on self-regulation to resolve public policy issues and advancing corporate social responsibility and corporate political activities (cf. Bauer, 2014; Lock & Seele, 2016).

5.3. Justice

As for justice, the literature distinguishes procedural justice from distributive justice (Neyer, 2010; Mollona & Faldetta, 2022). The former is related to throughput legitimacy, while the latter is related to output legitimacy. Early scholars of deliberative democracy limited the theory to process considerations and were critical of incorporating substantive principles to assess procedural outcomes, such as individual liberty or equal opportunity, beyond what is necessary for a fair democratic process in its theory, thus focusing on procedural justice (e.g. Habermas, 1979, 1996; Knight, 1999; King, 2003). Deliberative democracy means fair procedures, not right outcomes. Democratic citizens, not democratic theorists, should determine the content of laws. In addition, the political sovereignty of citizens should not be exercized through theoretical reasoning but through actual democratic decision making. A deliberative democratic theory that contains substantive principles would constrain the democratic decision-making process and the process of deliberation itself.

This view has been contested by Gutmann and Thompson (1996), who argue that the value of reciprocity can be a principle of justice that guides thinking in the ongoing process in which citizens as well as theorists consider what justice requires in the case of specific laws. They claim (p. 4) that “reciprocity is to justice in political ethics what replication is to truth in science. A finding of truth in science requires replicability, which calls for public demonstration. A finding of justice in political ethics requires reciprocity, which calls for public deliberation.” Deliberation is a process of seeking not just any reasons but mutually justifiable reasons and reaching a mutually binding decision based on those reasons. Thus, the process presupposes some principles with substantive content. For instance, few would dispute that deliberative justifications should completely ignore the values expressed by substantive principles such as liberty and equal opportunity. Including both substantive and procedural principles in a democratic theory inevitably increases the potential for conflict. But democratic politics is full of conflict among principles, and a democratic theory that tries to insulate itself from that conflict by limiting the range of principles it includes is likely to be less relevant for recognising and resolving the disagreements that democracies typically confront (Gutmann & Thompson, 1996).

In climate governance, claims are made for climate justice, both among scholars (Shepard & Corbin-Mark, 2009; Gardiner, 2011; Schlosberg & Collins, 2014; Newell et al., 2021) and social movements (Cassegård & Thörn, 2017; de Moor et al., 2020; Buzogány & Scherhaufer, 2022; Borkhart, 2023). The concept emerged from the merging of the environmental movement and the human rights and social justice movement (Schlosberg & Collins, 2014; Cassegård & Thörn, 2017; Borkhart, 2023). Climate justice scholarship traditionally demonstrates how climate change is a moral and justice issue, not just a science, techno-economic, or finance issue (Shepard & Corbin-Mark, 2009; Gardiner, 2011; Schlosberg & Collins, 2014; Newell et al., 2021). Climate justice addresses how climate change impacts people differently, unevenly, and disproportionately, normatively aiming to reduce marginalization, exploitation, and oppression as well as enhance equity and justice of humans across regions and generations. In more recent years, climate justice scholars have included insights from a range of academic theories (such as feminist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, post-colonial, and decolonial scholarship), to develop a more critical climate justice scholarship (Sultana, 2021). This development has made accountability and obligations, as well as ethics and human rights, more integral to climate justice. This also involves re-evaluation of global political economic systems that produce and reinforce socio-spatial injustices. Compared to climate justice scholars, the critical climate justice perspective also focuses on procedural justice of vulnerable and marginalized groups. In all, critical climate justice addresses both procedural and distributive justice.

5.4. Potential Conflicts between Norms

These norms could theoretically and empirically be in conflict, particularly procedural norms and substantive norms (Gutmann & Thompson, 1996). Consider for instance consensus rules, which would maximize the procedural justice as well as input and throughput legitimacy by giving all stakeholders a voice. However, this increase in input and throughput legitimacy can reduce the output legitimacy, distributive justice and effectiveness of the decision-making system. The collective accountability of decision-makers in deliberative democracy based on consensus hinges on the veto powers of a few decision-makers that “seek special benefits, pursue minority political agendas, or reap economic benefit from non-decisions and a persistence of the status quo” (Biermann & Gupta, 2011, p. 1863). Accountability and legitimacy of climate governance vis-à-vis the interests of a majority of humankind will be reduced. Conflicts between different democratic norms and principles could be dealt with if substantive norms to varying degrees are morally and politically provisional. A normative theory on policy entrepreneurs based on deliberative democratic theory can avoid usurping the moral or political authority of democratic citizens, while making substantive judgments about the policies they propose, since it claims provisional status for the principles it defends.

6. Empirical Findings from Europe

6.1. Democratic Deficits of Policy Entrepreneurs

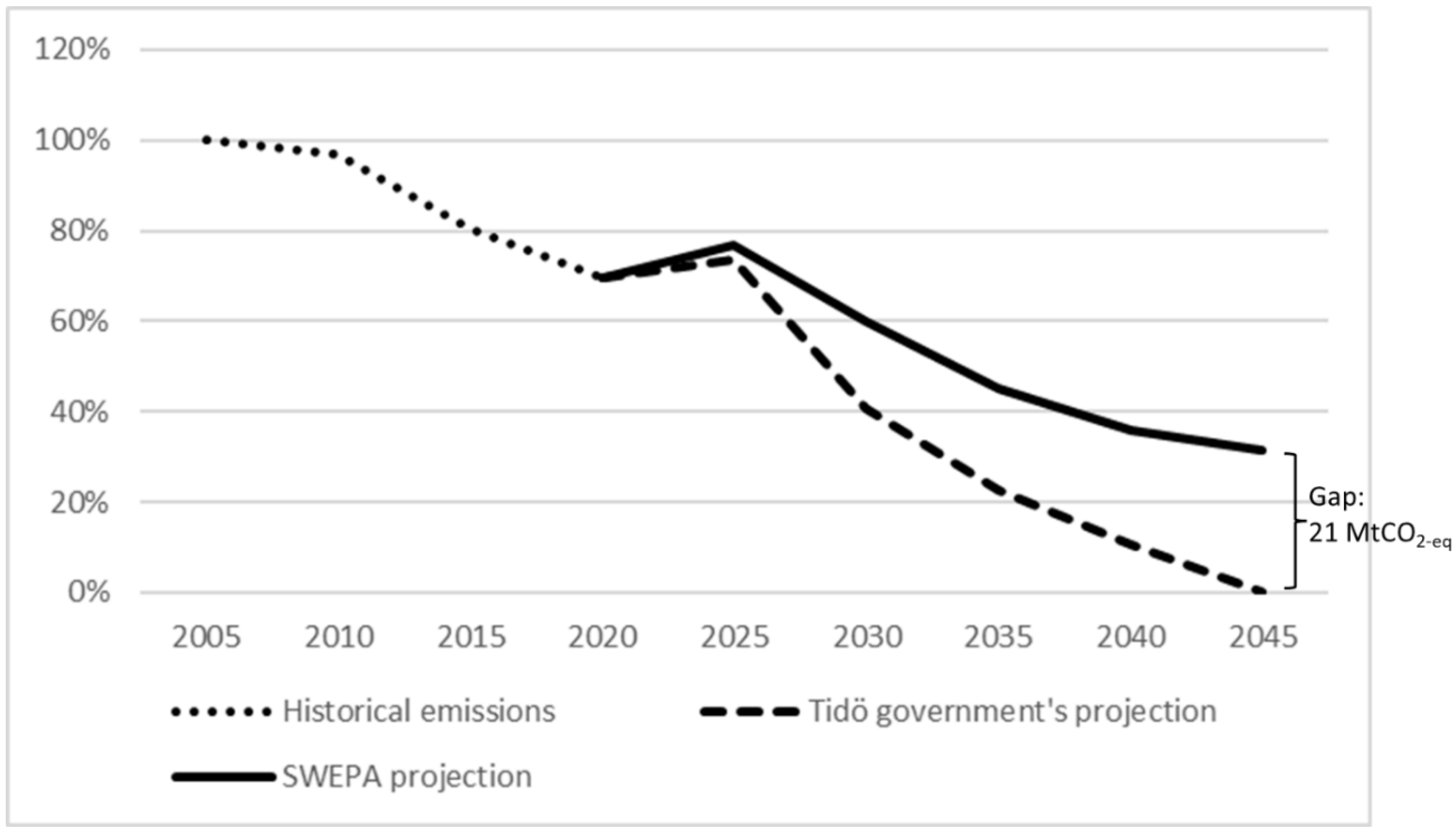

Based on the framework proposed above, the influence of policy entrepreneurs on democratic policy processes has been analysed in two case studies (Yin, 1994): (i) the development of new EU legislation to decarbonize international shipping (part of the European Green Deal and the legislative package Fit for 55), and (ii) the radical reform of Swedish climate policy since the right-wing Tidö government, supported (or rather ruled) by populist nationalist Sweden Democrats (SD), took office in autumn 2022. The cases were selected for their theoretical relevance, i.e. their ability to generate as many properties as possible of the phenomenon under study (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Both the EU and Sweden have long since been seen as pioneers in climate policy (Matti et al., 2021; Dupont et al., 2023), with the EU aspiring to hold leadership in global climate governance and uses ambitious EU climate policies to act as an ‘exemplary leader’ (Tobin et al., 2023). Sweden’s role as an international leader is currently eroding due to the Tidö government’s policy changes, and it has been widely criticised for increasing greenhouse gas emissions in the middle of a climate emergency when emission must be reduced drastically in short time (Swedish Climate Policy Council, 2024; Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, 2024; Swedish Finance Policy Council, 2024). Each case has been described in more detail elsewhere (von Malmborg, 2023c, 2024a, 2024b, 2024c) and are summarized below.

In the first case, the European Commission, through the Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport and the European confederation of green mobility NGOs, Transport & Environment, acted as policy entrepreneurs (von Malmborg, 2023c, 2024a). Both tried to influence the perceptions and beliefs of EU member states in the Council of the EU and political groups in the European Parliament. In the second case, SD acted as a policy entrepreneur to influence the perceptions and beliefs of the three parties in the government (the Moderates (M), the Christian Democrats (KD) and the Liberals (L)), but also to change power relations (von Malmborg, 2024b, 2024c). In the 2022 elections to the Swedish parliament (Riksdag), M, KD and L collected 29.05 per cent of the votes together, holding 103 of 349 seats. SD, collecting 20.54 per cent of the votes and 73 seats, overtook for the first time M’s long since place as the second largest party in the Riksdag. SD has no seats in the government cabinet but has political staff in the Prime Minister’s Office and participate in most political negotiations, including on climate policy which was included in the Tidö agreement reach by M, KD, L and SD for SD to support the government (von Malmborg, 2024b, 2024c). The so-called Tidö government then tried to influence the political opposition in the Riksdag, business, authorities, environmental organisations, voters and the media for a paradigm shift in Swedish climate policy.

All policy entrepreneurs used cultural-institutional entrepreneurship. The Commission, SD and the Tidö government also used structural entrepreneurship to influence power relations. For the Commission, it was about advancing its own positions of power as a supranational institution in European integration at the expense of member states’ flexibility in the central issue of subsidiarity, and thus about an increased technocratization of climate policy. This phenomenon of ‘competence creep’, where the EU acts outside of its powers and slowly expands its competences beyond what is conferred upon it by its members, informally increasing the powers of the EC while reducing the powers and flexibility of MSs, has been acknowledged for centuries (Garben, 2019). With the Lisbon Treaty, attempts were made to combat ‘competence creep’, but several flaws in the Treaty still makes it occur (Fox, 2020). Despite being legal, the ‘competence creep’ comes with democratic deficits related to accountability and legitimacy and should be combated to reinstate and reinforce the position and powers of both the national and European legislator in taking the important decisions that impact, directly or indirectly, the lives of European citizens (Garben, 2022).For the Tidö government and SD, it was about systematically silencing critics, as part of an ongoing, broad autocratization. All policy entrepreneurs in the two cases, including the civil society organization Transport & Environment, showed a democratic deficit from both liberal and deliberative democratic perspectives (

Table 3 and

Table 4), although it is most obvious and conspicuous in the case of Swedish climate policy.

For Transport & Environment, deficits were related to lack of transparency and lack of focus on distributive justice. For the Commission, deficits related to lack of transparency, low legitimacy and procedural as well as distributive justice. Both Transport & Environment and the Commission failed to include climate justice and just transition, taking into account participation and impacts on affected actors outside the EU. This is remarkable since the need for decarbonization will increase the cost of shipping by 2050 – about 7 % in the EU and 17.8 % in third countries (von Malmborg, 2024a). As argued by Shaw and De Beukelaer (2022), “shipping decarbonization would likely make raising living standards for the world’s poorest difficult, costing development opportunities, as already limited resources would be consumed by higher shipping costs”. In comparison, the issues of a just transition are discussed in the International Maritime Organization (IMO) as part of the discussions on policy measures to reach the new IMO target on climate neutrality by mid-century.

The actions of SD and the Tidö government as policy entrepreneurs in reforming Swedish climate policy aims to hinder critics from participating in the democratic conversation with limited or no debate and increases the influence of structural governance by changing the distribution of formal power, redefining democratic concepts and manipulating factual and scientific information. This can lead to reduced trust in the rule of law and lower legitimacy for democracy. As for manipulation of information, the Tidö parties cross-safely claimed that they are the first to present a trustworthy climate action plan (Swedish government, 2023) with policies that will lead to greenhouse gas emission reductions to reach the Swedish target on climate neutrality by 2045. Showing a graph with an emission trajectory with zero emission 2045, they told that Sweden has a plan to reach all the way down to net zero emissions by 2045. However, the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (2024) presented data for the government’s annual climate report and included its own calculations of emission reductions of existing policies and policies proposed by the Tidö government. It shows a gap of almost 50 per cent of current emission levels to reach the target on climate neutrality by 2045, clearly indicating the government’s manipulation of information (

Figure 3). Obviously, the Tidö government has no plan, only guesswork and manipulation, with tens of millions of tonnes of greenhouse gases to be removed with policy and technology not yet invented.

As for the Tidö parties’ discrimination, smearing and increased repression of climate activists, negatively impacting throughput legitimacy and procedural justice as well as accountability, the UN special rapporteur for the rights of environmental organizations according to the Aarhus Convention, Michel Forst (2024, p. 11), claims that “by categorizing environmental activism as a potential terrorist threat, by limiting freedom of expression and by criminalizing certain forms of protests and demonstrators, these legislative and policy changes contribute to the shrinking of civic space and seriously threaten the vitality of democratic societies”.

As for distributive justice, the Tidö parties have taken measures to reduce costs of fossil fuels for cars and for aviation, with a skewed reference to ‘climate justice’, but have actively decided not to take measures to reduce costs for public transport, which have increased much more than fuel prices. Critics have claimed that the induced cost reductions for fossil fuels do not benefit the groups who are most vulnerable (Swedish Climate Policy Council, 2024; Swedish Finance Policy Council, 2024). Research shows that earmarking of revenues from taxes used for subsidies to vulnerable households would increase justice and maintain effectiveness, thus improve legitimacy (Maestre-Andrés et al., 2019; Ewald et al., 2022; Matti et al., 2022). In addition, the Tidö parties duck on the topic of increasing energy poverty in Sweden, caused by the clean energy transition (von Platten et al., 2022).

The lack of focus on distributive energy and climate justice by all policy entrepreneurs has implications on both legitimacy and accountability of the four policy entrepreneurs and climate governance, which are affected by the resulting mismatches between those who seek to hold others accountable and those who are to be held accountable, the former which could be stakeholders in the global South, and the latter actors in the global North, including policy entrepreneurs (Dryzek & Stevenson, 2011). Functional interdependencies refer the diverse sectors of global production and consumption, which make the assessment of the accountability and legitimacy of rule-making dependent on the boundaries to be drawn around the ‘stakeholders’ included (Biermann & Gupta, 2011).

6.2. Explaining the Democratic Deficits

In both cases, the democratic deficit of policy entrepreneurs can be linked to the neo-corporatist nature of relations between executive authorities and other policy actors in Sweden and the EU, and in close relation to this the idea of ecological modernization. The nature of stakeholder relations in these contexts is generally consultative, but it is a centralized and elitist top-down, exclusive type of consultation. where decision-makers engage with a few policy actors of a comprehensive nature, often resulting in representative monopoly, non-transparency and other democratic deficits (van den Hove, 2000; Burns & Carson, 2002; Kronsell et al., 2019). The EU ‘demoi-cracy’