Submitted:

17 May 2024

Posted:

17 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Results

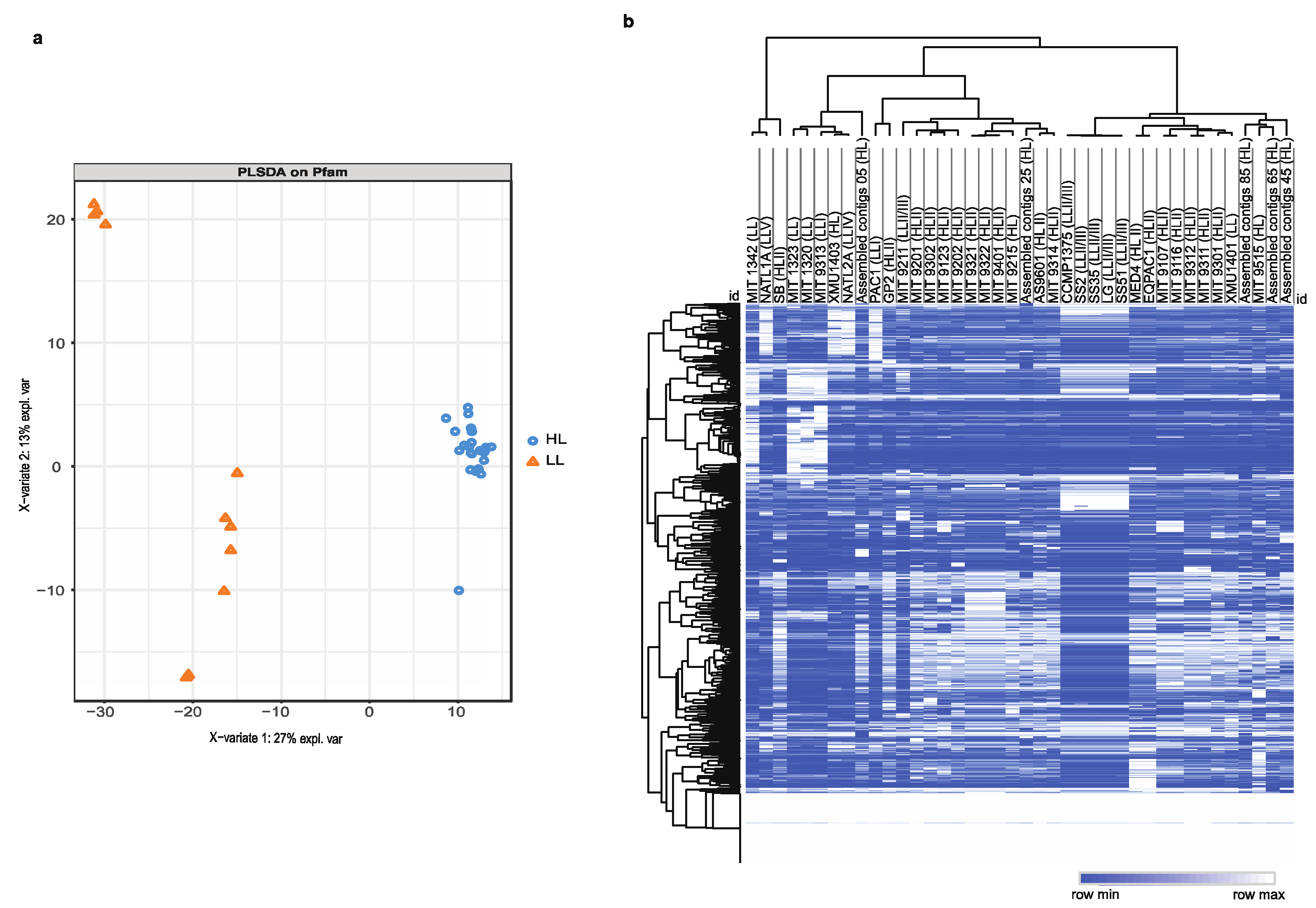

Decoding High-Light and Low-Light Associated Gene Sets from P. marinus Genomes

Identification of Minimal Pfam Sets Distinguishing HL and LL Strains

Variable, Depth-Dependent Accumulation of Endogenous Viral Elements

The Prochlorococcus Strains MED4 and NATL1A as HL and LL Representatives

ORFeome Resource Development

Discussion

Material and Methods

Protein Family Domain Prediction

Hierarchical Bi-Clustering

Response Screening

Deep Learning ANN Analysis

VFam Analysis

Metabolic Pathway Analysis

Functional Annotation Analysis using Blast2GO

ORFeome Synthesis and Cloning

Gateway Transfer and Sequence Validation

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- Percival, S.L. & Williams, D.W. in Microbiology of Waterborne Diseases (Second Edition). (eds. S.L. Percival, M.V. Yates, D.W. Williams, R.M. Chalmers & N.F. Gray) 79-88 (Academic Press, London; 2014).

- Demoulin, C.F. et al. Cyanobacteria evolution: Insight from the fossil record. Free Radic Biol Med 140, 206-223 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Ruffing, A.M. Engineered cyanobacteria: Teaching an old bug new tricks. Bioengineered Bugs 2, 136-149 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Goericke, R. & Welschmeyer, N.A. The marine prochlorophyte Prochlorococcus contributes significantly to phytoplankton biomass and primary production in the Sargasso Sea. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 40, 2283-2294 (1993). [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, D.J. et al. Ecological genomics of marine picocyanobacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 73, 249-299 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Partensky, F., Hess, W.R. & Vaulot, D. Prochlorococcus, a marine photosynthetic prokaryote of global significance. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 63, 106 (1999). [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.R., Rocap, G. & Chisholm, S.W. Physiology and molecular phylogeny of coexisting Prochlorococcus ecotypes. Nature 393, 464-467 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Luo, H., Huang, Y., Stepanauskas, R. & Tang, J. Excess of non-conservative amino acid changes in marine bacterioplankton lineages with reduced genomes. Nature Microbiology 2, 17091 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Kettler, G.C. et al. Patterns and implications of gene gain and loss in the evolution of Prochlorococcus. PLoS genetics 3, e231-e231 (2007). [CrossRef]

- O'Leary, N.A. et al. Reference sequence (RefSeq) database at NCBI: current status, taxonomic expansion, and functional annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 44, D733-D745 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Dufresne, A. et al. Genome sequence of the cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus marinus SS120, a nearly minimal oxyphototrophic genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100, 10020-10025 (2003).

- Rocap, G. et al. Genome divergence in two Prochlorococcus ecotypes reflects oceanic niche differentiation. Nature 424, 1042-1047 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Weitz, J.S. & Wilhelm, S.W. Ocean viruses and their effects on microbial communities and biogeochemical cycles. F1000 Biol Rep 4, 17 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.Y. et al. Comparative genomics reveals insights into cyanobacterial evolution and habitat adaptation. ISME J 15, 211-227 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Yang, F. et al. Function of Protein Kinases in Leaf Senescence of Plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 13 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Andrés, G., María, F.F., María-Teresa, B., María-Luisa, P. & Emma, S. in Cyanobacteria. (ed. T. Archana) Ch. 6 (IntechOpen, Rijeka; 2018).

- Jia, A., Zheng, Y., Chen, H. & Wang, Q. Regulation and Functional Complexity of the Chlorophyll-Binding Protein IsiA. Front Microbiol 12, 774107 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Kroh, G.E. & Pilon, M. in International Journal of Molecular Sciences, Vol. 21 (2020).

- Christensen, Q.H. & Cronan, J.E. Lipoic acid synthesis: a new family of octanoyltransferases generally annotated as lipoate protein ligases. Biochemistry 49, 10024-10036 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Cronan, J.E. Assembly of Lipoic Acid on Its Cognate Enzymes: an Extraordinary and Essential Biosynthetic Pathway. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 80, 429-450 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Bristow, L.A., Mohr, W., Ahmerkamp, S. & Kuypers, M.M.M. Nutrients that limit growth in the ocean. Curr Biol 27, R474-r478 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Latifi, A., Ruiz, M. & Zhang, C.-C. Oxidative stress in cyanobacteria. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 33, 258-278 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Santamaría-Gómez, J., Ochoa de Alda, J.A.G., Olmedo-Verd, E., Bru-Martínez, R. & Luque, I. Sub-Cellular Localization and Complex Formation by Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases in Cyanobacteria: Evidence for Interaction of Membrane-Anchored ValRS with ATP Synthase. Frontiers in Microbiology 7 (2016).

- Luque, I., Riera-Alberola, M.L., Andújar, A. & Ochoa de Alda, J.A.G. Intraphylum Diversity and Complex Evolution of Cyanobacterial Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases. Molecular Biology and Evolution 25, 2369-2389 (2008).

- Song, K. et al. AtpΘ is an inhibitor of F0F1 ATP synthase to arrest ATP hydrolysis during low-energy conditions in cyanobacteria. Current Biology 32, 136-148.e135 (2022).

- Cassier-Chauvat, C., Veaudor, T. & Chauvat, F. Comparative Genomics of DNA Recombination and Repair in Cyanobacteria: Biotechnological Implications. Front Microbiol 7, 1809 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Kolowrat, C. et al. Ultraviolet stress delays chromosome replication in light/dark synchronized cells of the marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus marinus PCC9511. BMC Microbiology 10, 204 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Osburne, M.S. et al. UV hyper-resistance in Prochlorococcus MED4 results from a single base pair deletion just upstream of an operon encoding nudix hydrolase and photolyase. Environ Microbiol 12, 1978-1988 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Cassier-Chauvat, C. & Chauvat, F. Responses to oxidative and heavy metal stresses in cyanobacteria: recent advances. Int J Mol Sci 16, 871-886 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Berube, P.M., Rasmussen, A., Braakman, R., Stepanauskas, R. & Chisholm, S.W. Emergence of trait variability through the lens of nitrogen assimilation in Prochlorococcus. Elife 8 (2019).

- Varkey, D. et al. Effects of low temperature on tropical and temperate isolates of marine Synechococcus. The ISME Journal 10, 1252-1263 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Knoll, A. & Puchta, H. The role of DNA helicases and their interaction partners in genome stability and meiotic recombination in plants. Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 1565-1579 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Hilbert, M., Karow, A.R. & Klostermeier, D. The mechanism of ATP-dependent RNA unwinding by DEAD box proteins. 390, 1237-1250 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Muzzopappa, F. et al. Paralogs of the C-Terminal Domain of the Cyanobacterial Orange Carotenoid Protein Are Carotenoid Donors to Helical Carotenoid Proteins. Plant Physiol 175, 1283-1303 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Cerveny, L. et al. Tetratricopeptide repeat motifs in the world of bacterial pathogens: role in virulence mechanisms. Infect Immun 81, 629-635 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Grove, T.Z., Cortajarena, A.L. & Regan, L. Ligand binding by repeat proteins: natural and designed. Curr Opin Struct Biol 18, 507-515 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Rast, A., Rengstl, B., Heinz, S., Klingl, A. & Nickelsen, J. The Role of Slr0151, a Tetratricopeptide Repeat Protein from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, during Photosystem II Assembly and Repair. Frontiers in Plant Science 7 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Biller, S.J., Coe, A. & Chisholm, S.W. Torn apart and reunited: impact of a heterotroph on the transcriptome of Prochlorococcus. The ISME Journal 10, 2831-2843 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Kong, R., Xu, X. & Hu, Z. A TPR-family membrane protein gene is required for light-activated heterotrophic growth of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. FEMS Microbiol Lett 219, 75-79 (2003).

- Morimoto, K., Nishio, K. & Nakai, M. Identification of a novel prokaryotic HEAT-repeats-containing protein which interacts with a cyanobacterial IscA homolog. FEBS Lett 519, 123-127 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.-P. et al. The role of lyases, NblA and NblB proteins and bilin chromophore transfer in restructuring the cyanobacterial light-harvesting complex‡. The Plant Journal 102, 529-540 (2020).

- Gisriel, C.J. et al. Structure of a dimeric photosystem II complex from a cyanobacterium acclimated to far-red light. J Biol Chem 299, 102815 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Safferman, R.S. et al. Classification and nomenclature of viruses of cyanobacteria. Intervirology 19, 61-66 (1983). [CrossRef]

- Dammeyer, T., Bagby, S.C., Sullivan, M.B., Chisholm, S.W. & Frankenberg-Dinkel, N. Efficient phage-mediated pigment biosynthesis in oceanic cyanobacteria. Curr Biol 18, 442-448 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Voorhies, A.A. et al. Ecological and genetic interactions between cyanobacteria and viruses in a low-oxygen mat community inferred through metagenomics and metatranscriptomics. Environ Microbiol 18, 358-371 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Moniruzzaman, M., Weinheimer, A.R., Martinez-Gutierrez, C.A. & Aylward, F.O. Widespread endogenization of giant viruses shapes genomes of green algae. Nature 588, 141-145 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Rozenberg, A. et al. Lateral Gene Transfer of Anion-Conducting Channelrhodopsins between Green Algae and Giant Viruses. Curr Biol 30, 4910-4920.e4915 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Chelkha, N., Levasseur, A., La Scola, B. & Colson, P. Host-virus interactions and defense mechanisms for giant viruses. Ann N Y Acad Sci (2020). [CrossRef]

- Yoosuf, N. et al. Complete genome sequence of Courdo11 virus, a member of the family Mimiviridae. Virus Genes 48, 218-223 (2014). [CrossRef]

- de Aquino, I.L.M. et al. Diversity of Surface Fibril Patterns in Mimivirus Isolates. J Virol 97, e0182422 (2023).

- . Bisio, H. et al. Evolution of giant pandoravirus revealed by CRISPR/Cas9. Nat Commun 14, 428 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Hikida, H., Okazaki, Y., Zhang, R., Nguyen, T.T. & Ogata, H. A rapid genome-wide analysis of isolated giant viruses using MinION sequencing. Environ Microbiol 25, 2621-2635 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Esmael, A., Agarkova, I.V., Dunigan, D.D., Zhou, Y. & Van Etten, J.L. Viral DNA Accumulation Regulates Replication Efficiency of Chlorovirus OSy-NE5 in Two Closely Related Chlorella variabilis Strains. Viruses 15 (2023)abilis Strains. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-García, J.L., de Ory, A., Brussaard, C.P.D. & de Vega, M. Phaeocystis globosa Virus DNA Polymerase X: a "Swiss Army knife", Multifunctional DNA polymerase-lyase-ligase for Base Excision Repair. Sci Rep 7, 6907 (2017).

- Derelle, E. et al. Diversity of Viruses Infecting the Green Microalga Ostreococcus lucimarinus. J Virol 89, 5812-5821 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Delaroque, N., Maier, I., Knippers, R. & DG, M.l. Persistent virus integration into the genome of its algal host, Ectocarpus siliculosus (Phaeophyceae). J Gen Virol 80 ( Pt 6), 1367-1370 (1999). [CrossRef]

- Haller, S.L., Peng, C., McFadden, G. & Rothenburg, S. Poxviruses and the evolution of host range and virulence. Infect Genet Evol 21, 15-40 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Conesa, A. et al. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 21, 3674-3676 (2005).

- Kehr, J.C. & Dittmann, E. Biosynthesis and function of extracellular glycans in cyanobacteria. Life (Basel) 5, 164-180 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Walhout, A.J. et al. in Methods in enzymology, Vol. 328 575-IN577 (Elsevier, 2000).

- Hartley, J.L., Temple, G.F. & Brasch, M.A. DNA cloning using in vitro site-specific recombination. Genome Res 10, 1788-1795 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Dreze, M. et al. in Methods in Enzymology, Vol. 470 281-315 (Academic Press, 2010).

- Sánchez-Baracaldo, P. Origin of marine planktonic cyanobacteria. Scientific Reports 5, 17418 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Ulloa, O. et al. The cyanobacterium <i>Prochlorococcus</i> has divergent light-harvesting antennae and may have evolved in a low-oxygen ocean. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, e2025638118 (2021).

- El-Seedi, H.R. et al. Review of Marine Cyanobacteria and the Aspects Related to Their Roles: Chemical, Biological Properties, Nitrogen Fixation and Climate Change. Mar Drugs 21 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Flombaum, P. et al. Present and future global distributions of the marine Cyanobacteria <i>Prochlorococcus</i> and <i>Synechococcus</i>. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110, 9824-9829 (2013).

- Puxty, R.J., Millard, A.D., Evans, D.J. & Scanlan, D.J. Shedding new light on viral photosynthesis. Photosynth Res 126, 71-97 (2015). [CrossRef]

- James, J.E., Nelson, P.G. & Masel, J. Differential Retention of Pfam Domains Contributes to Long-term Evolutionary Trends. Molecular Biology and Evolution 40, msad073 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Godbold, J.A. & Calosi, P. Ocean acidification and climate change: advances in ecology and evolution. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 368, 20120448 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Beardall, J., Stojkovic, S. & Larsen, S. Living in a high CO2 world: impacts of global climate change on marine phytoplankton. Plant Ecology & Diversity 2, 191-205 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Hallegraeff, G.M. Ocean climate change, phytoplankton community responses, and harmful algal blooms: a formidable predictive challenge 1. Journal of phycology 46, 220-235 (2010).

- Shestakov, S.V. & Karbysheva, E.A. The role of viruses in the evolution of cyanobacteria. Biology Bulletin Reviews 5, 527-537 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Zhaxybayeva, O., Doolittle, W.F., Papke, R.T. & Gogarten, J.P. Intertwined evolutionary histories of marine Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus marinus. Genome Biol Evol 1, 325-339 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Zeidner, G. et al. Potential photosynthesis gene recombination between Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus via viral intermediates. Environ Microbiol 7, 1505-1513 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Lindell, D. et al. Genome-wide expression dynamics of a marine virus and host reveal features of co-evolution. Nature 449, 83-86 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Gong, W. et al. Genome-wide ORFeome cloning and analysis of Arabidopsis transcription factor genes. Plant Physiol 135, 773-782 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.E., Breton, G. & Pruneda-Paz, J.L. Construction of Arabidopsis Transcription Factor ORFeome Collections and Identification of Protein-DNA Interactions by High-Throughput Yeast One-Hybrid Screens. Methods Mol Biol 1794, 151-182 (2018).

- Rual, J.-F. et al. Human ORFeome Version 1.1: A Platform for Reverse Proteomics. Genome Research 14, 2128-2135 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Lamesch, P. et al. hORFeome v3.1: a resource of human open reading frames representing over 10,000 human genes. Genomics 89, 307-315 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Rajagopala, S.V. et al. The Escherichia coli K-12 ORFeome: a resource for comparative molecular microbiology. BMC Genomics 11, 470-470 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Özkan, E. et al. An extracellular interactome of immunoglobulin and LRR proteins reveals receptor-ligand networks. Cell 154, 228-239 (2013).

- Ghamsari, L. et al. Genome-wide functional annotation and structural verification of metabolic ORFeome of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. BMC Genomics 12 Suppl 1, S4-S4 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Pellet, J. et al. ViralORFeome: an integrated database to generate a versatile collection of viral ORFs. Nucleic Acids Res 38, D371-D378 (2010)n integrated database to generate a versatile collection of viral ORFs. [CrossRef]

- Fu, W., Nelson, D.R., Mystikou, A., Daakour, S. & Salehi-Ashtiani, K. Advances in microalgal research and engineering development. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 59, 157-164 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Metsalu, T. & Vilo, J. ClustVis: a web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using Principal Component Analysis and heatmap. Nucleic Acids Res 43, W566-W570 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Darzi, Y., Letunic, I., Bork, P. & Yamada, T. iPath3.0: interactive pathways explorer v3. Nucleic Acids Res 46, W510-W513 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Rual, J.-F. et al. Towards a proteome-scale map of the human protein–protein interaction network. Nature 437, 1173-1178 (2005). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).