Submitted:

16 May 2024

Posted:

16 May 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

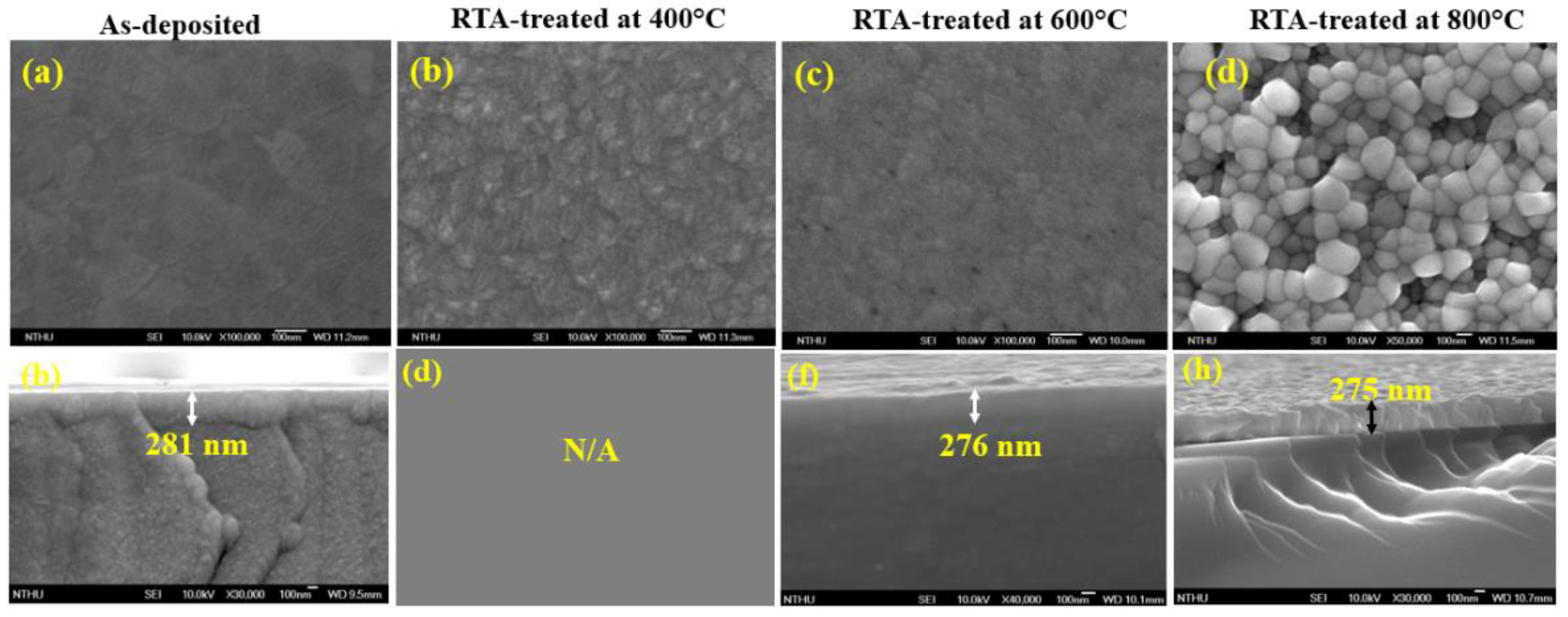

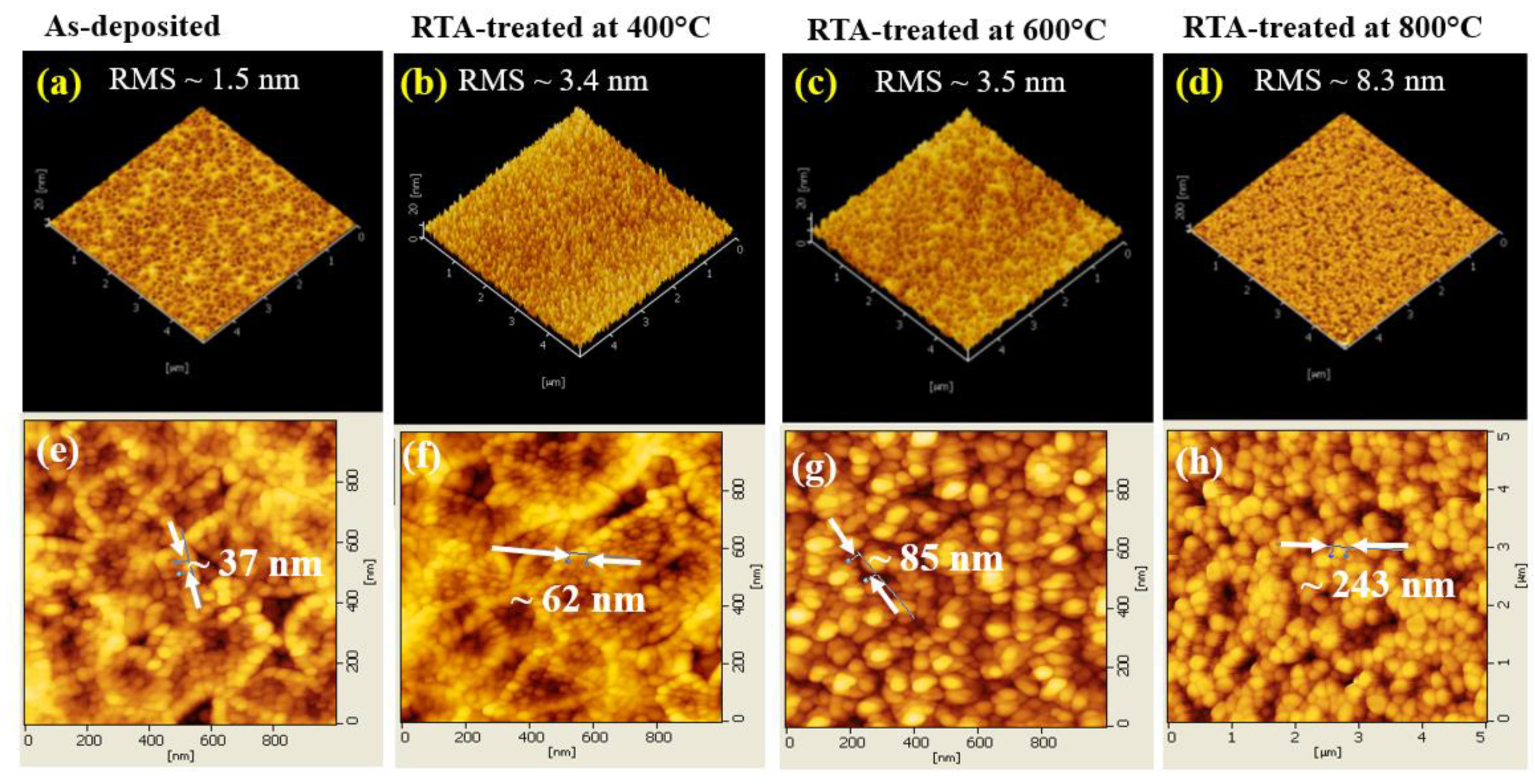

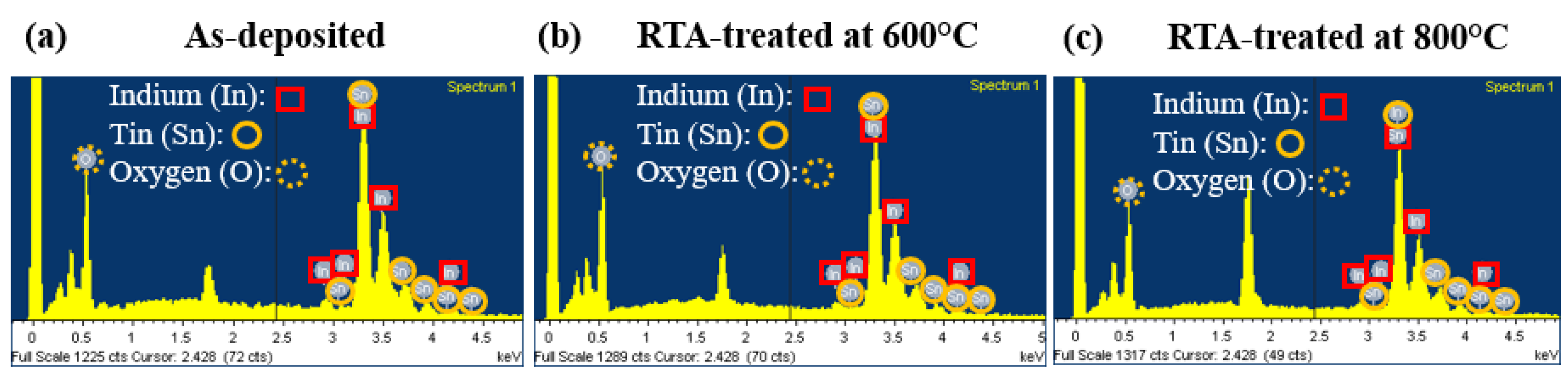

3.1. Surface Morphology, Composition and Structral Properties

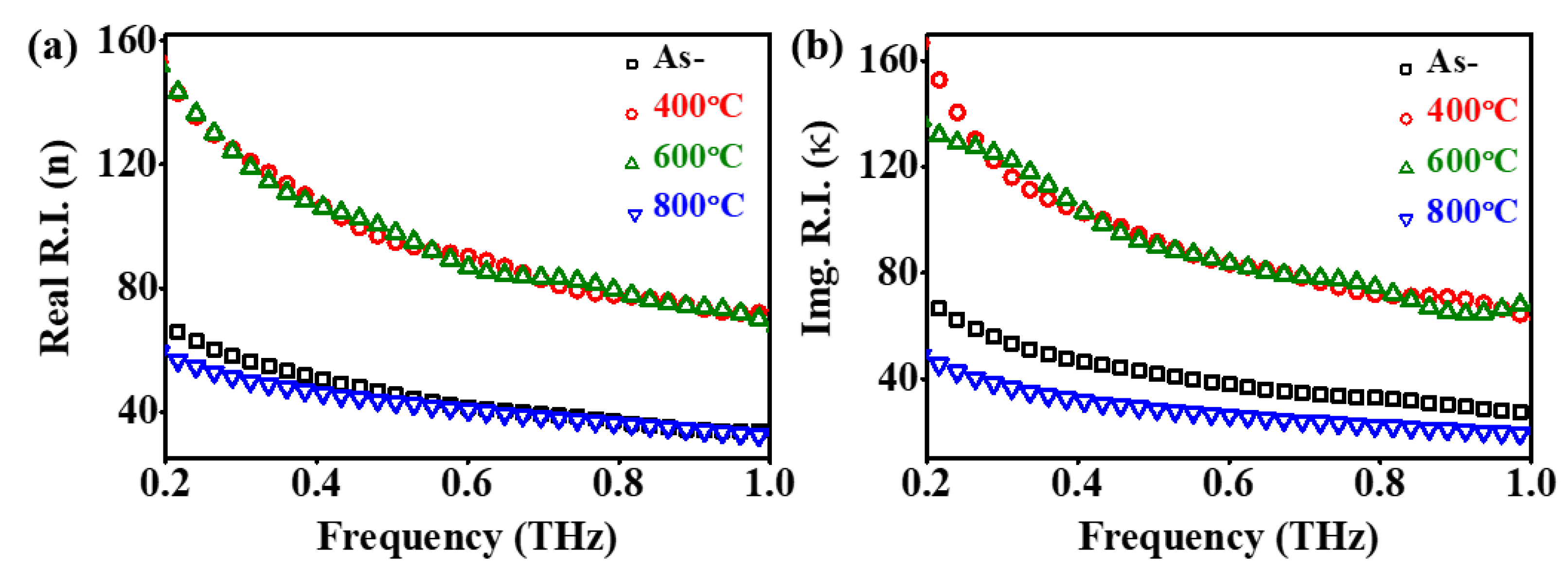

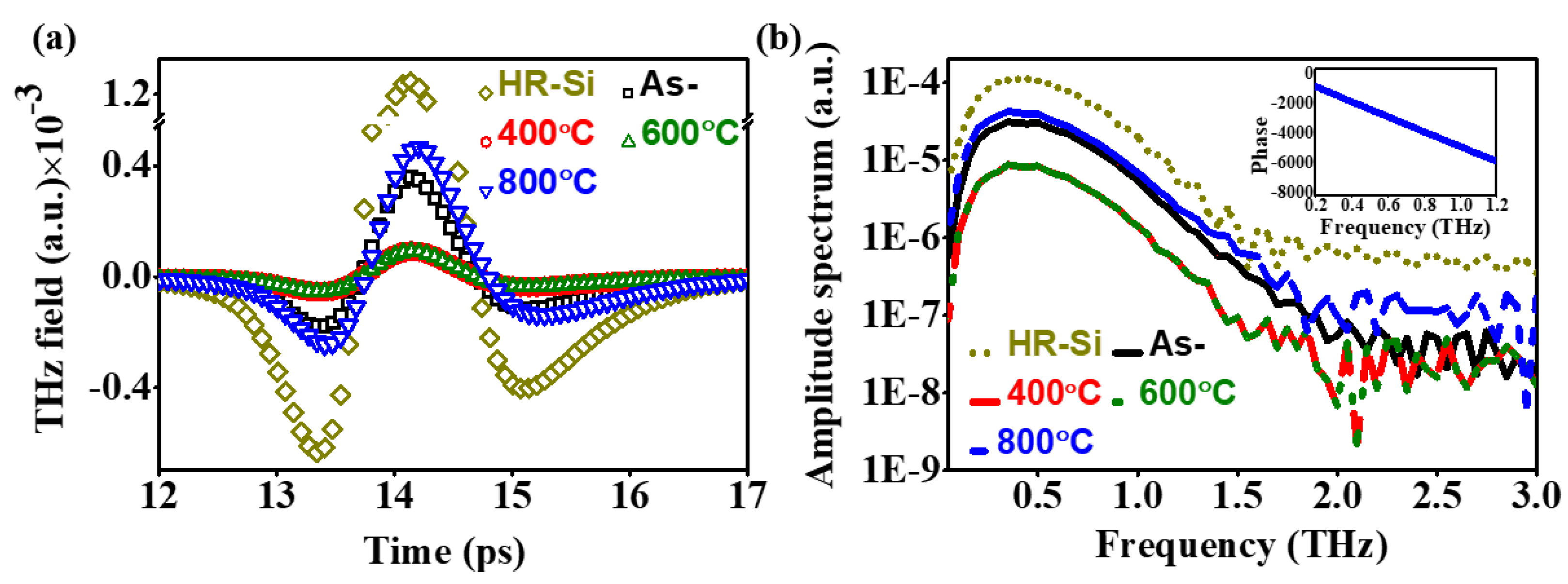

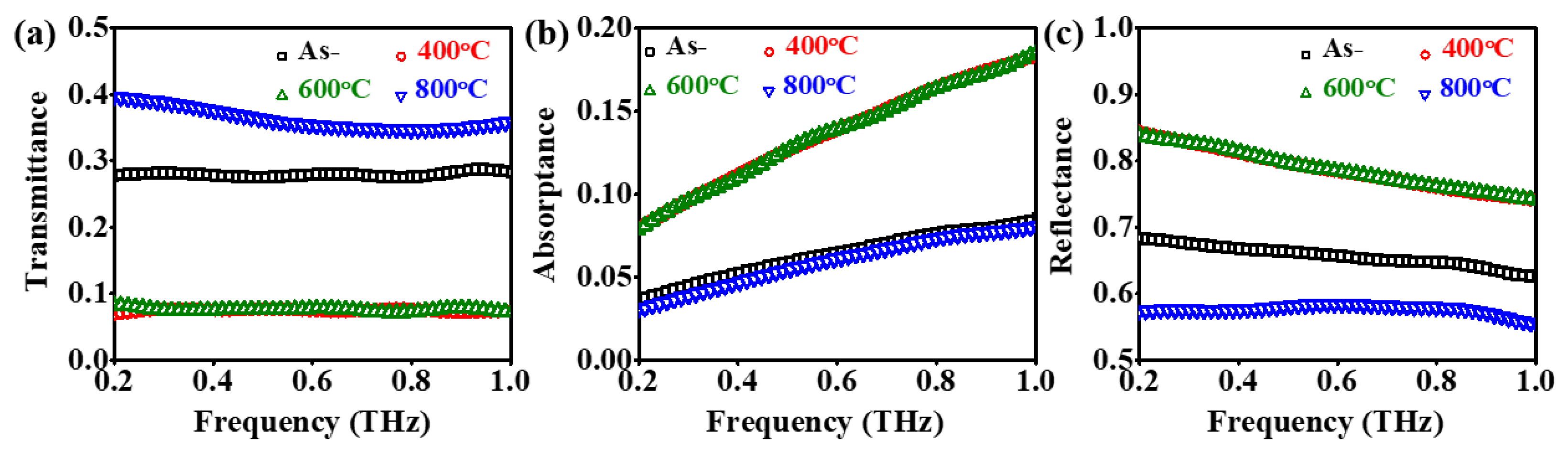

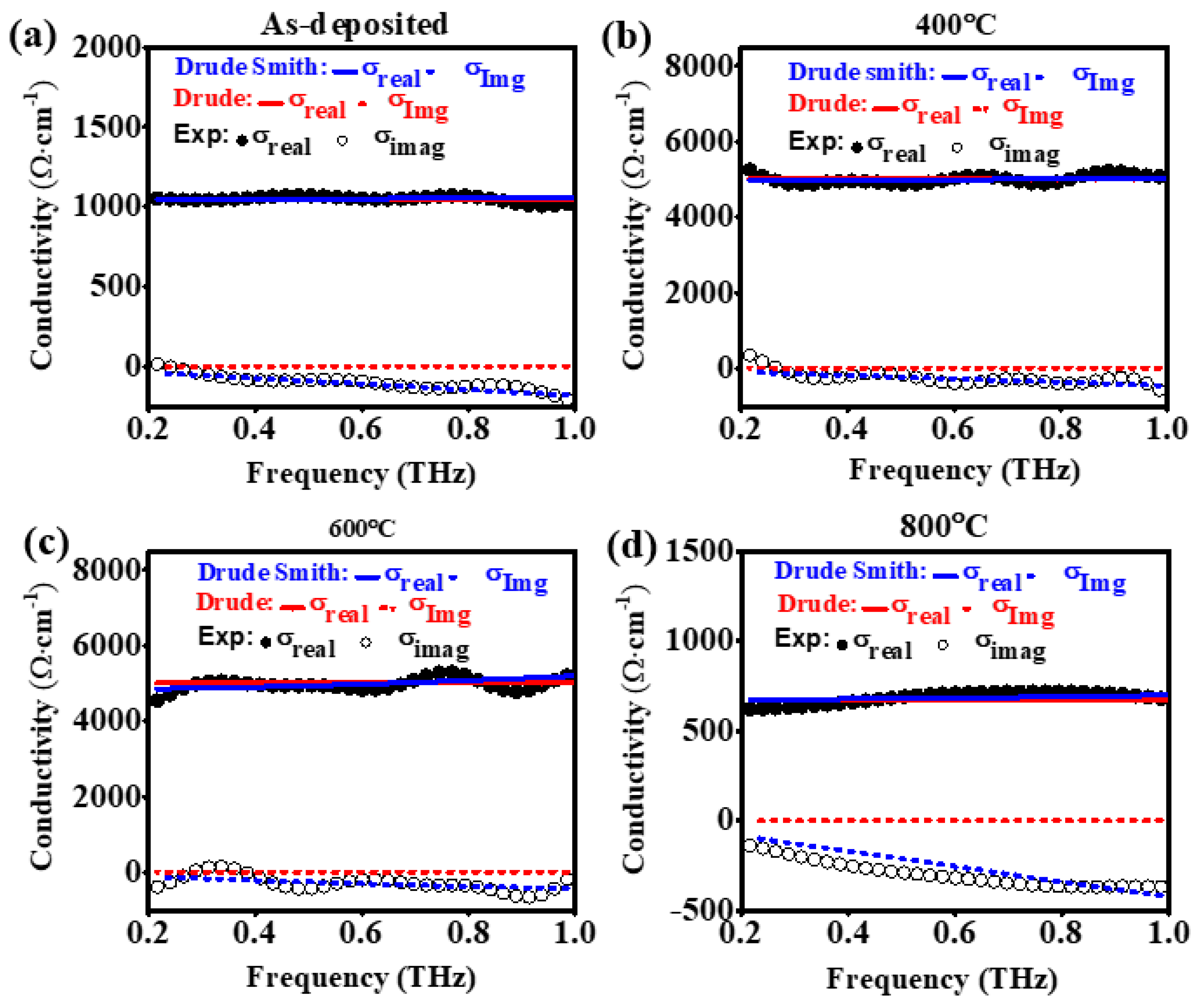

3.2. THz Optical and Electrical Properties

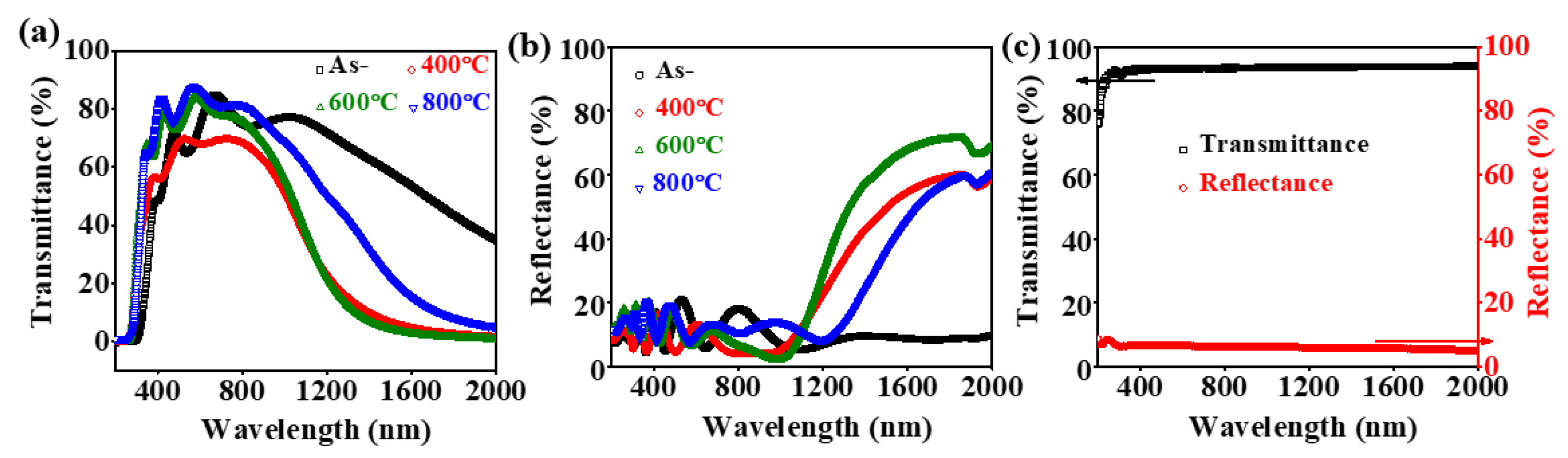

3.3. Annealing Effects on UV-VIS-NIR Optical Properties of ITO Films

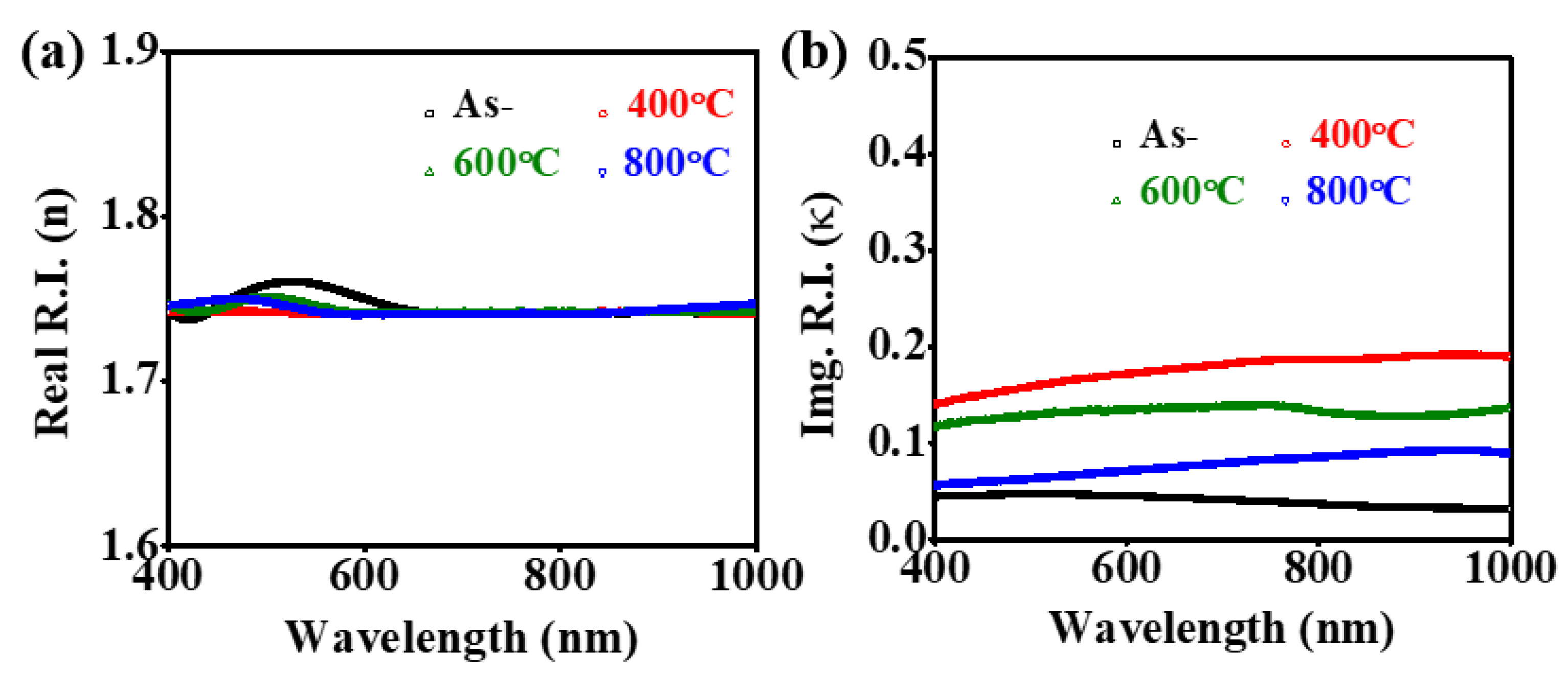

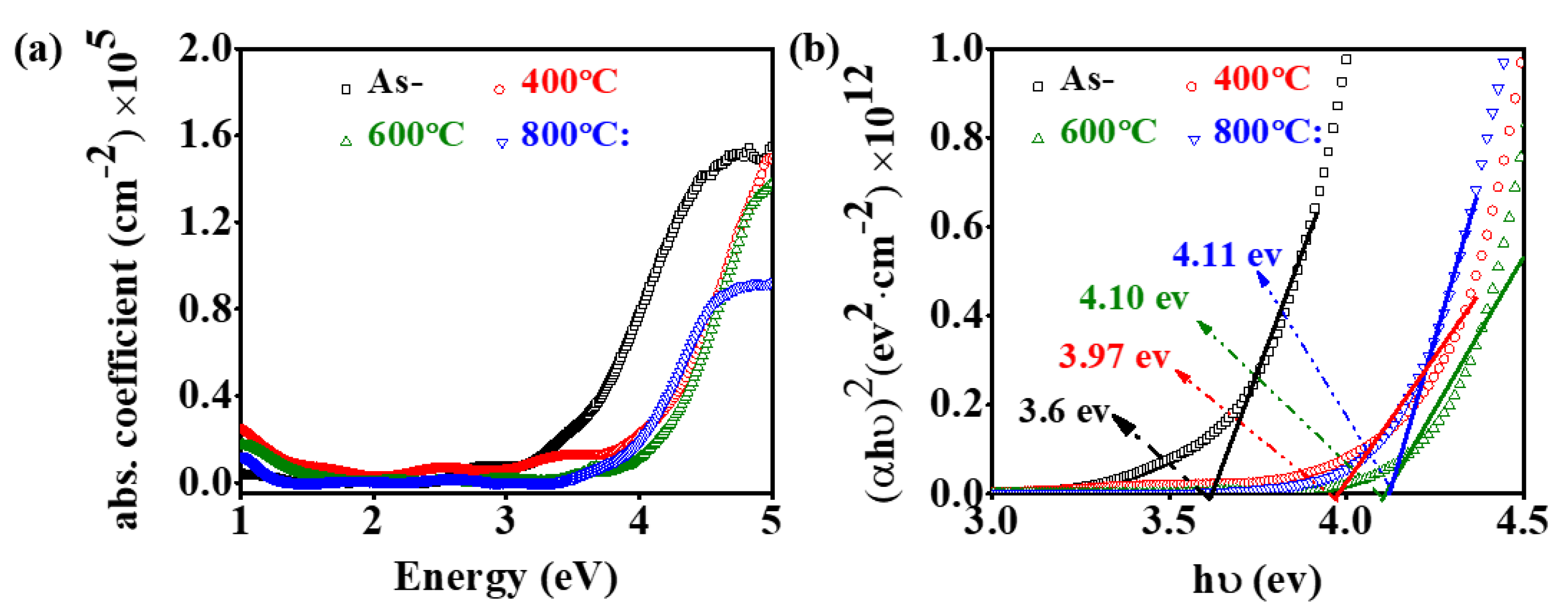

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tripathi, M.N.; Bahramy, M.S.; Shida, K.; Sahara, R.; Mizuseki, H.; Kawazoe, Y. Optoelectronic and magnetic properties of Mn-doped indium tin oxide: A first-principles study. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 112, 073105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamberg, I.; Granqvist, C. G. Evaporated Sn-doped In2O3 films: Basic optical properties and applications to energy-efficient windows, J. Appl. Phys. 60, 1986, R123–R160.

- Li, S.; Tian, M.; Gao, Q.; Wang, M.; Li, T.; Hu, Q.; Li, X.; Wu, Y. Nanometre-thin indium tin oxide for advanced high-performance electronics. Nat. Mater. 2019, 18, 1091–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Perera, I.R.; Daeneke, T.; Makuta, S.; Tachibana, Y.; Jasieniak, J.J.; Mishra, A.; Bäuerle, P.; Spiccia, L.; Bach, U. Indium tin oxide as a semiconductor material in efficient p-type dye-sensitized solar cells. NPG Asia Mater. 2016, 8, e305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, K.; Ye, C.; Sorger, V.J. Indium-tin-oxide for high-performance electro-optic modulation. Nanophotonics 2015, 4, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhere; R. G.; Gessert, T.A.; Schilling, L.L.; Nelson, A.J.; Jones, K.M.; Aharoni, H.; Coutts, T.J. Electro-optical properties of thin indium tin oxide films: Limitations on performance. Solar Cells, 1987, 21, 281–290.

- Shi, K.; Haque, R.R.; Zhao, B.; Zhao, R.; Lu, Z. Broadband electro-optical modulator based on transparent conducting oxide. Opt. Lett. 2014, 39, 4978–4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, M.; Andler, J.; Lyu, X.; Niu, C.; Datta, S.; Agrawal, R.; Ye, P.D. Indium-Tin-Oxide Transistors with One Nanometer Thick Channel and Ferroelectric Gating. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 11542–11547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H. , Gilmore, C. M., Piqué, A., Horwitz, J. S., Mattoussi, H., Murata, H., Kafafi, J. H. & Chrisey, D. B. Electrical, optical, and structural properties of indium-tin-oxide thin films for organic light-emitting devices. J. Appl. Phys. 1999, 86, 6451–6461. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. , Noh, J. H., Bae, S.-T., Cho, I.-S., Kim, J. Y., Shin, H., Lee, J.-K., Jung, H. S. & Hong, K. S. Indium-tin-oxide-based transparent conducting layers for highly efficient photovoltaic devices. J. Phys. Chem. 2009, C 113, 7443–7447. [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian, N.; and Subrahmanyam, A. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics Purpose-led Publishing, find out more. Electrical and optical properties of reactively evaporated indium tin oxide (ITO) films-dependence on substrate temperature and tin concentration. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 1989, 22, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laux, S.; Kaiser, N.; Zöller, A.; Götzelmann, R.; Lauth, H.; Bernitzki, H. Room-temperature deposition of indium tin oxide thin films with plasma ion-assisted evaporation. Thin Solid Films 1998, 335, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.K.; Jeong, I.H.; Kim, W.K.; Kwak, M.G. Deposition of indium-tin-oxide films on polymer substrates for application in plastic-based flat panel displays. Thin Solid Films 2001, 397, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, A. Transparent Conducting Oxides—An Up-To-Date Overview. Materials 2012, 5, 661–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, G.; Yan, Y. Effects of Doping Ratio and Thickness of Indium Tin Oxide Thin Films Prepared by Magnetron Sputtering at Room Temperature. Coatings 2023, 13, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubitidze, T.; Britton, W.A.; Negro, L.D. Enhanced Nonlinearity of Epsilon-Near-Zero Indium Tin Oxide Nanolayers with Tamm Plasmon-Polariton States. Adv. Optical Mater. 2024, 12, 2301669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Chae, M.; Lee, D.; Kim, H.D. Enhanced optical and electrical properties of indium tin oxide for solar cell applications via post-microwave treatment. Optical Materials, 2024, 149, 115093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H.; Seok, H.-J.; Jung, S.H.; Cho, H.K.; Kim, H.-K. Rapid Thermal Annealing Effect of Transparent ITO Source and Drain Electrode for Transparent Thin Film Transistors. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 3149–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, T. Transparent conducting oxide semiconductors for transparent electrodes. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2005, 20, S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.M.; Sahoo, A.K.; Liu, C.Y. Influence of RF power on performance of sputtered a-IGZO based liquid crystal cells. Thin Solid Films 2015, 596, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jiang, L.; Li, X.; Luo, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, M.; Yan, Y. Different Crystallization Behavior of Amorphous ITO Film by Rapid Infrared Annealing and Conventional Furnace Annealing Technology. Materials 2023, 16, 3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.F.; Lin, K.M.; Ho, Y.S. Laser annealing process of ITO thin films using beam shaping technology. Optics and Lasers in Engineering, 2012, 50, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jeon, K.A.; Kim, G.H.; Lee, S.Y. Electrical, structural, and optical properties of ITO thin films prepared at room temperature by pulsed laser deposition. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2006, 252, 4834–4837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prepelita, P.; Stavarache, I.; Craciun, D.; Garoi, F.; Negrila, C.; Sbarcea, B.G.; Craciun, V. Rapid thermal annealing for high-quality ITO thin films deposited by radio-frequency magnetron sputtering. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2019, 10, 1511–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Yang, T.; Liu, J.; Xin, Y.; Li, Y.; Han, S. Rapid thermal annealing of ITO films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 7061–7064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.-Y.; Jeon, S.-P.; Park, J.B.; Park, H.-B.; Kim, D.-H.; Yang, S.H.; Kim, G.; Jo, J.-W.; Oh, M.S.; Kim, M.; et al. High-performance ITO/a-IGZO heterostructure TFTs enabled by thickness-dependent carrier concentration and band alignment manipulation. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 5905–5914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniyara, R.A.; Graham, C.; Paulillo, B.; Bi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Herranz, G.; Baker, D.E.; Mazumder, P.; Konstantatos, G.; Pruneri, V. Highly transparent and conductive ITO substrates for near infrared applications. APL Mater. 2021, 9, 021121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun; J. H.; Kim; J.; Park, Y.C. Transparent Conductor-Si pillars heterojunction photodetector. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 116, 064904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Kempa, K.; Giersig, M.; Akinoglu, E.M.; Han, B.; Li, R. Physics of transparent conductors. Adv. Phys. 2016, 65, 553–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Z.J.; Valenta, C.R.; Durgin, G.D. Optically Transparent Antennas: A Survey of Transparent Microwave Conductor Performance and Applications. IEEE Antennas Propag. Mag. 2021, 63, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Mei, Z.; Zhang, J.; Xu, W.; Lin, W.; Niu, T. An Ultra-wideband, Wide-angle And Transparent Microwave Absorber Using Indium Tin Oxide Conductive Films. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2024, 23, 1543–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Huang, Y.; Chen, K.A.; Liang, S.; Yuan, Y.; Dai, D.; Ye, H. Design and fabrication of indium tin oxide for high performance electro-optic modulators at the communication wavelength. Optical Materials 2024, 148, 114931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, A.K.; Kang, S.-Y.; Yu, P.; Pan, C.-L. Enhanced Optically–Excited THz Wave Emission by GaAs Coated with a Rough ITO Thin Film. Coatings 2023, 13, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Q.; Jia, W.; Feng, X.; Chen, X.; Gu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, W. ; Han. J. Two-Color-Driven Controllable Terahertz Generation in ITO Thin Film ACS Photonics 2024, 11, 293–300. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Z.; Song, L.; Zhang, T. Terahertz reflection and visible light transmission of ITO films affected by annealing temperature and applied in metamaterial absorber. Vacuum 2018, 149, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, A.K.; Mai, C.-M.; Pan, C.-L. Enhancement of Indium tin oxide nano-scale films for terahertz device applications treated by rapid thermal annealing. In Proceedings of the 2020 45th International Conference on Infrared, Millimeter, and Terahertz Waves (IRMMW-THz), Buffalo, NY, USA, 8–13 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, T.R.; Chen, C.Y.; Pan, C.L.; Pan, R.P.; Zhang, X.C. Terahertz time-domain spectroscopy studies of the optical constants of the nematic liquid crystal 5CB. Appl. Opt. 2003, 42, 2372–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.A.; Tani, M.; Pan, C.-L. THz radiation emission properties of multi energy arsenic-ion-implanted GaAs and semi-insulating GaAs based photoconductive antennas. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 93, 2996–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.R.; Reddy, M.S.; Rao, P.K. Effect of rapid thermal annealing on deep level defects in the Si-doped GaN. Microelectron. Eng. 2010, 87, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaurain, A.; Luxembourg, D.; Dufour, C.; Koncar, V.; Capoen, B.; Bouazaoui, M. Effects of annealing temperature and heat-treatment duration on electrical properties of sol–gel derived indium-tin-oxide thin films. Thin Solid Films 2008, 516, 4102–4106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Mao, W.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, C.; Liu, Y.; He, C. Defects evolution and their impacts on conductivity of indium tin oxide thin films upon thermal treatment. J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 118, 025304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Brinkman, A.W. Preparation and characterization of NiMn2O4 films. Int. J. Inorg. Mater. 2001, 3, 1215–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumoorthi, M.; Prakash, J.T.J. Structure, optical and electrical properties of indium tin oxide ultra-thin films prepared by jet nebulizer spray pyrolysis technique. Asian Ceram. Soc. 2016, 4, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, S.; Sawada, Y.; Ogawa, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Kagota, Y.; Shida, A.; Ide, M. Highly conducting indium-tin-oxide transparent films prepared by dip-coating with an indium carboxylate salt. Surf. Coatings Technol. 2003; 169-170, 525–527. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-W.; Lin, Y.-C.; Chang, C.-H.; Yu, P.; Shieh, J.-M.; Pan, C.-L. Frequency-dependent complex conductivities and dielectric responses of indium tin oxide thin films from the visible to the far-infrared. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 2010, 46, 1746–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.S.; Chang, C.M.; Chen, P.H.; Yu, P.; Pan, C.L. Broadband terahertz conductivity and optical transmission of indium-tin-oxide (ITO) nanomaterials. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 16670–16682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-S.; Lin, M.-H.; Chang, C.-H.; Yu, P.; Shieh, J.-M.; Shen, C.-H.; Wada, O.; Pan, C.-L. Non-Drude behavior in indium-tin-oxide nanowhiskers and thin films investigated by transmission and reflection THz time-domain spectroscopy. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 2013, 49, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-S.; Kuo, C.; Tang, C.-C.; Chen, J.C.; Pan, R.-P.; Pan, C.-L. Liquid-Crystal Terahertz Quarter-Wave Plate Using Chemical-Vapor-Deposited Graphene Electrodes. IEEE Photonics J. 2015, 7, 2200808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, A.K.; Au, W.C.; Hong, Y.C.; Pan, C.L.; Zhai, D.; Hérault, E.; Garet, F.; Coutaz, J.L. Dopant profiling of ion-implanted GaAs by terahertz time-domain spectroscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 2023, 133, 125705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.-L.; Yang, C.-S.; Pan, R.-P.; Yu, P.; Lin, G.-R. Nanostructured Indium Tin Oxides and other Transparent Conducting Oxides: Characteristics and Applications in the THz Frequency Range. In Terahertz Spectroscopy—A Cutting Edge Technology; Chapter, 14, Uddin, J., Eds.; InTech Open: London, UK, 2017; pp. 267–286. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, C.; Hsieh, C.; Pan, R.; Tanaka, M.; Miyamaru, F.; Tani, M.; Hangyo, M. Control of enhanced THz transmission through metallic hole arrays using nematic liquid crystal. Opt. Express 2005, 13, 3921–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zalkovskij, M.; Iwaszczuk, K.; Lavrinenko, A.V.; Naik, G.V.; Kim, J.; Boltasseva, A.; Jepsen, P.U. Ultrabroadband terahertz conductivity of highly doped ZnO and ITO. Opt. Mater. Express 2015, 5, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, V.; Prathuru, A.; Fernandez, C.; Sujatha, D.; Panda, S.K.; Faisal, N.H. Indium tin oxide thin film preparation and property relationship for humidity sensing: A review. Engineering Reports, 2024 p.e12836.

- Sahoo, A.K.; Yang, C.-S.; Wada, O.; Pan, C.-L. Twisted nematic liquid crystal based terahertz phase shifter with crossed indium tin oxide finger type electrodes. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 2019, 9, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, F.E.M.; Kurcbart, S.M. Hagen-rubens relation beyond far-infrared region. Eur. Phys. Lett 2010, 90, 44004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naftaly, M.; Dudley, R. Terahertz Reflectivities of Metal-Coated Mirrors. Appl. Opt. 2011, 50, 3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Born and E. Wolf, Principles of optics: electromagnetic theory of propagation, interference and diffraction of light, 7th ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N. Classical generalization of the Drude formula for the optical conductivity. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 64, 155106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Němec, H.; Kužel, P.; Sundström, V. Charge transport in nanostructured materials for solar energy conversion studied by time-resolved terahertz spectroscopy. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 2010, 215, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titova, L.V.; Cocker, T.L.; Cooke, D.G.; Wang, X.; Meldrum, A.; Hegmann, F.A. Ultrafast percolative transport dynamics in silicon nanocrystal films. Physical Review B 2011, 83, 085403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conwell, E.; V. F. Weisskopf. Theory of impurity scattering in semiconductors. Physical review 1950, 77, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ederth, J. Electrical transport in nanoparticle thin films of gold and indium tin oxide (Doctoral dissertation, Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis).

- Swanepoel, R. Determination of the thickness and optical constants of amorphous silicon. Journal of Physics E: Scientific Instruments, 1983, 16, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacini, A.; Ali, A.H.; Adnan, N.N. Optimization of ITO thin film properties as a function of deposition time using the swanepoel method. Opt. Mater. 2021, 120, 111411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.K.; Raju, R.C.N.; Subrahmanyam, A. Thickness dependent physical and photocatalytic properties of ITO thin films prepared by reactive DC magnetron sputtering. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 3075–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgonos, A.; Mason, T.O.; Poeppelmeier, K.R. Direct optical band gap measurement in polycrystalline semiconductors: A critical look at the Tauc method. J. Solid State Chem. 2016, 240, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elnaiem, A.M. and Hakamy, A., Influence of annealing temperature on structural, electrical, and optical properties of 80 nm thick indium-doped tin oxide on borofloat glass. J. Mater. Sci. : Mater. Electron. 2022, 33, 23293–23305. [Google Scholar]

| Sample | O K | In L | Sn L | |||

| Weight (%) | Atomic (%) | Weight (%) | Atomic (%) | Weight (%) | Atomic (%) | |

| As- | 22.78 | 68.01 | 67.44 | 28.05 | 9.77 | 3.93 |

| 600°C | 22.98 | 68.23 | 69.48 | 28.75 | 7.54 | 3.02 |

| 800°C | 24.71 | 70.27 | 66.90 | 26.51 | 8.38 | 3.21 |

| Parameters | As- | 400°C | 600°C | 800°C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| µ (cm2/V∙s) | 29 | 110 | 226 | 70 |

| ωp (rad·THz) | 3315 | 3711 | 2580 | 1648 |

| τ (fs) | 6 | 12 | 21 | 20 |

| c | -0.83 | -0.68 | -0.63 | -0.87 |

| N (cm-3) | 2.17×1020 | 2.72×1020 | 1.31×1020 | 5.58×1019 |

| σ ( Ω-1‧cm-1) | 1019 | 4897 | 4881 | 628 |

| ρ (Ω‧cm) | 9.8×10-4 | 2.0×10-4 | 2.0×10-4 | 15.9×10-4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).