1. Introduction

Removable prostheses, as a replacement for the dental implant, become indispensable, especially in economically deprived areas considering the fact that the global population of older adults is projected to reach 2 billion by 2050 [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Given that these restorations mostly address the senior population, it's important to point out that accidental dropping is more likely to occur leading to fractures and damages. To meet this growing need, various materials have been looked into, intending to optimize the prosthesis bases, while focusing on enhancing biocompatibility, resistance and longevity of these devices [

5].

The main material used for denture bases is polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), due to its broad application and adaptability. PMMA, which is created by addition chain reaction polymerization, has several mechanical qualities that make it a good choice for prosthodontics [

6]. However, the end product's flexural strength and modulus are seriously influenced by the polymerization technique: compression molding, injecting, 3D printing and CAD-CAM [

7].

Removable prostheses have seen a fundamental change recently because of advances in polymer materials, allowing improved durability and performance [

8,

9]. Despite these advancements, notable differences still occur amongst various polymer materials, requiring a thorough grasp of their mechanical, physical, and therapeutic implications [

10,

11,

12].

The material of choice for prosthetic bases is Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA) owing to its favorable mechanical properties and its versatility [

6]. Albeit its extensive application, PMMA presents certain drawbacks, including polymerization shrinkage, feeble flexural strength, and vulnerability to fractures [

6]. To overcome these shortcomings, research was concerned with additions and modifications to improve PMMA's qualities, such as copolymers, plates, and fiber reinforcement [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Moreover, improvements in CAD/CAM fabrication processes indicate better mechanical qualities for PMMA dentures than those made using conventional techniques [

20,

21,

22,

23]. PMMA is still a good alternative for detachable prosthesis despite its drawbacks, especially when combined with cutting-edge manufacturing processes and improved materials [

20,

21,

22,

23].

PMMA was the chosen material for this paper, being the most used material by the majority of practitioners.

Manufacturing dentures by compression-molding typically (the conventional method - packing-press) involves several visits to the dental practice. First the preliminary impression is taken in alginate so that the preliminary model can be poured, which serves the purpose of designing the custom impression tray. This tray will be used with silicone impression materials to increase accuracy, so that the final cast model can be poured. The previously recorded jaw relations are used to mount the final models in an articulator with wax rims. The wax is done and the artificial teeth will be fitted onto the wax in order to obtain a functional occlusion. After the try-in is successful, the wax-up can be flasked and boiled in water to have the wax melt and leave a hollow where PMMA is to be inserted. As the artificial teeth are partially enclosed in gypsum, these will retain their spatial conformation, while also having an exposed area where they can bind to PMMA. The flask will be pressed to ensure the proper distribution of the acrylate and removal of excess material. After polymerization of PMMA the denture will be carefully removed from the flask for finishing and polishing. The 3D architecture distortions of the entire denture appear due to the material contractions during the polymerization process along with materials defects trapped inside the material; all of these are leading to clinical failure of the prosthetic treatment.

The injection molding method is similar to the traditional method up to the flasking step, while it sets itself apart in that the wax-up is flasked in a specialized mold equipped with an aperture. Through this aperture, the resin is injected under pressure and heated. After polymerization is completed, the denture is finished and polished, awaiting delivery. The PMMA materials comes in monomer /powder recipients or predosed cartridges. Distortions can still appear while the rate of the trapped materials are reduced.

Another injection method for the completed dentures implies PMMA materials that are already prepolimerized while the step of the technique is the same with the one described. The thermoplastic injection method implies minimal deformations and the materials are more compact in structure.

The digital flow in complete dentures are coming with a 2-4 technology steps, reducing the manufacturing time. The process starts by taking digital impressions along with jaw relations in the same appointment. The data is digitalized and used for computer aided design (CAD) where the future denture can be devised to meet the clinical needs. The denture will be printed or milled. The milling technology is using blocks of pre-polymerized PMMA, manufactured under high pressure and temperature, which confers better mechanical properties. The computer aided manufacturing part of the process comes next, where the design is achieved through milling of PMMA blocks by means of a milling machine. After milling, the denture is to be finished and polished, so it can be delivered to the patient. The prices of the systems and the materials are high, resulting in a few reports on this technology. The milling process could involve separately the base and the raw of the artificial teeth (that need to be luted in a following technological step) while other system could produce the entire complete denture in one single block.

3D printing is additive in nature in contrast to CAD/CAM. One possibility is to build objects layer by layer using stereolithography, which utilizes a liquid resin that polymerizes when exposed to ultraviolet light, depositing material in a sequential fashion to create the desired shape. The layer-by-layer approach hinders the resolution and esthetics of the denture through the discontinuity of the surface it creates. This can also have effects on the mechanical and physical properties of the denture [

24], but the materials have a more advantageous cost, given that there are less consumables. This method is capable to produce only separately the base and the artificial teeth that needs to be luted in a separated technological time. Several reports pointed out the cytotoxicity of some materials used for this technology.

Given the laborious workflow of packing press and injection molding and the less favorable mechanical and esthetical properties of the 3D printed dentures, CAD/CAM seems like a promising choice for the future of digital dentistry.

This research aims to compare the mechanical properties of complete dentures fabricated by means of 4 different processing technologies. The null hypothesis tested conveys that the digital processing technologies produces significant differences in the mechanical properties of the dentures in terms of increasing it.

2. Materials and Methods

Four different processing techniques, all utilizing PMMA as the main material, were used to construct complete dentures to test the null hypothesis. Six pairs of complete dentures (12 complete dentures) were used as samples for each processing procedure. PMMA was chosen because of its widespread application and adaptability in the denture manufacturing process. The 4 selected methods for producing dentures are as follows: traditional packing-press, thermoplastic injection molding, 3D printing and CAD/CAM technology.

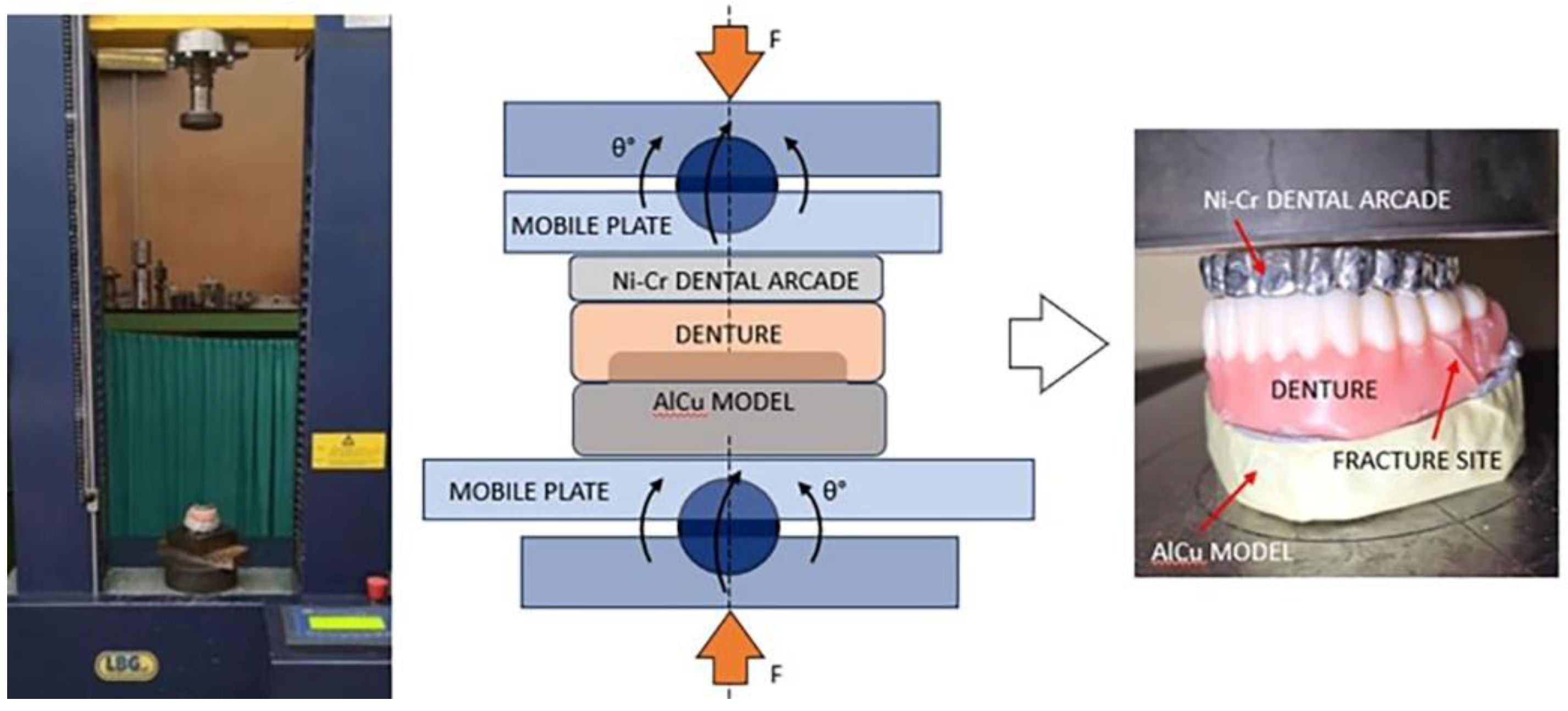

All the samples were tested in the Universal Testing Machine LBG TC100 (LBG testing equipment SRL, Azzano s.Paolo (BG) Italy). The universal testing machine is deemed to simulate compressive forces similar to those acting on the dentures in the oral cavity.

The edentulous patients are developing mostly vertical and short amplitude mastication movements. The lateral movements have minimal amplitude and could lead to an unbalanced occlusion. For these reasons, compressions forces are predominat on the complete dentures in the clinical environment. In this paper, only the strength of the complete dentures on compression forces were considered.

A special Ni-Cr dental arch was created for the opposite arch from that on which the denture was tested. And the denture was seated on a AlCu model, representing the supporting structures. Those structure allows to test only the mechanical characteristics of the considered complete dentures.

2.1. Traditional Dentures

Fabricating complete dentures using traditional packing-press technology begins with taking impressions of the edentulous arches using alginate. These impressions are then poured with dental stone to create preliminary models. Wax rims are adapted to these models to establish the occlusal plane and vertical dimension of occlusion. Next, the models are articulated in a semi-adjustable articulator. Artificial teeth are selected and fitted on the pink wax according to occlusal and functional considerations. After final adjustments and approval by the patient, the wax setup is flasked, and the wax is eliminated through the process of boiling out. Acrylic resin is then packed into the mold and processed, resulting in the fabrication of complete dentures. Finally, the dentures are finished, polished, and delivered to the patient, with follow-up appointments for adjustments as needed.

In

Figure 1 are presented the working steps presented for obtaining a complete denture, using the conventional packing-press technology.

2.2. Thermoplastic Injected Dentures

Injectable acrylic resins have a higher density, with disadvantages pertaining to the high initial cost of the injection setup than for traditional dentures because it requires special equipment such as an injector and special molds. These also have higher fracture resistance. Through industrial polymerization, the internal conversion rate is towards 100%, resulting in a product that does not eliminate residual monomer, which could have toxic and allergic effects in the oral cavity. The thermoplastic resin used for denture bases comes in cartridges. Injection processes are primarily employed in thermoplastic materials and rarely to thermosetting ones. The principle of plastic material injection involves pressing the molten material into the mold cavity.

The injection molding system used in this paper was the Thermopress400 from Bredent (

Figure 2). Special bottles and cartridges are used for the process.

2.3. D Printed Dentures

The methodology employed for fabricating these dentures represents a departure from conventional techniques. It starts with the acquisition of a digital impression of the patient's oral cavity using an intraoral scanner. Subsequently, the digital data is utilized by the dental technician to construct the models and fabricate the occlusal wax rims. Once the occlusal rims are crafted, they are subjected to scanning. Prior to this step, it is imperative for the vertical dimension of occlusion (VDO) to be established. Utilizing the tooth library within the 3Shape software, a wide array of tooth shapes and sizes are available for customization. This digital approach facilitates precise tooth selection and positioning. Illustrated in

Figure 3.b is the procedure of selecting denture teeth in Centric Relation (CR). After finalizing the denture base design and tooth selection, digital files are sent to the 3D printer (3D printer FormLabs Form 2). These files guide the printer in creating the anatomically shaped base and ensuring accurate tooth placement in Centric Relation (CR). Cartridges containing photopolymerizable resins (Base RP for the base and B1 for teeth) are used for printing. The printer dispenses resin layers onto the platform, gradually forming highly accurate and customized dentures. This additive manufacturing technique enables intricate details to be reproduced with precision.

Figure 3 provides a visual representation of the design and printing process.

2.4. CAD/CAM Technology

The Ivotion system (Ivoclar) was employed for the CAD/CAM denture workflow. A significant innovation within this system involves the utilization of monolithic discs, wherein highly cross-linked PMMA tooth and denture base materials are merged, facilitating uninterrupted milling of both components. This integration obviates the need for laborious manual steps traditionally required for bonding teeth to the denture base, owing to the direct chemical bond formed during the polymerization process. Following the design phase in the 3Shape Dental System, the milling machine seamlessly executes the fabrication process. Subsequently, the milled dentures undergo a polishing procedure, culminating in the completion of the manufacturing process (

Figure 4).

2.5. Mechanical Testing

A total of 48 dentures were obtained and submerged in distilled water at a temperature of 37°C for 24h. Subsequently, the specimens underwent mechanical compression testing. In order to achieve a vertical loading direction on the angular assembly of mod-el-denture-dental arcade, an adaptation mechanism was installed on the Universal Test-ing Machine LBG TC100 (LBG testing equipment srl, Azzano s.Paolo (BG) Italy). The mechanism (

Figure 5) allows rotation of its plates in order for these becoming parallel during testing, independent on the angulation of the assembly. A 50 kN loading cell (0.001 kN resolution) was used to measure the compressive force while the loading velocity of the head was 2mm/min. The tests were conducted up to the failure of the denture, the stopping criteria being a sudden dropping of force (85% of maximum).

2.6. Optical Microscopy

The fracture sections and the overall aspect of the denture after mechanical testing were evaluated on stereo microscope Optika SLX-3 45x (OPTIKA S.r.l., Ponteranica (BG) - Italy) using a C-B16 16MP camera for acquiring the images. The samples undergo no preparation prior to microscopy and the magnification range used was 10-45x.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v25. Quantitative variables were expressed as Mean ± Standard Deviation and as Median (Quartile1-Quartile3). The comparison was made using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis Test (for comparison between more than two independent groups) and the Mann-Whitney U Test (for the comparison between two independent groups). The results were considered significant for a value of p < 0.05.

3. Results

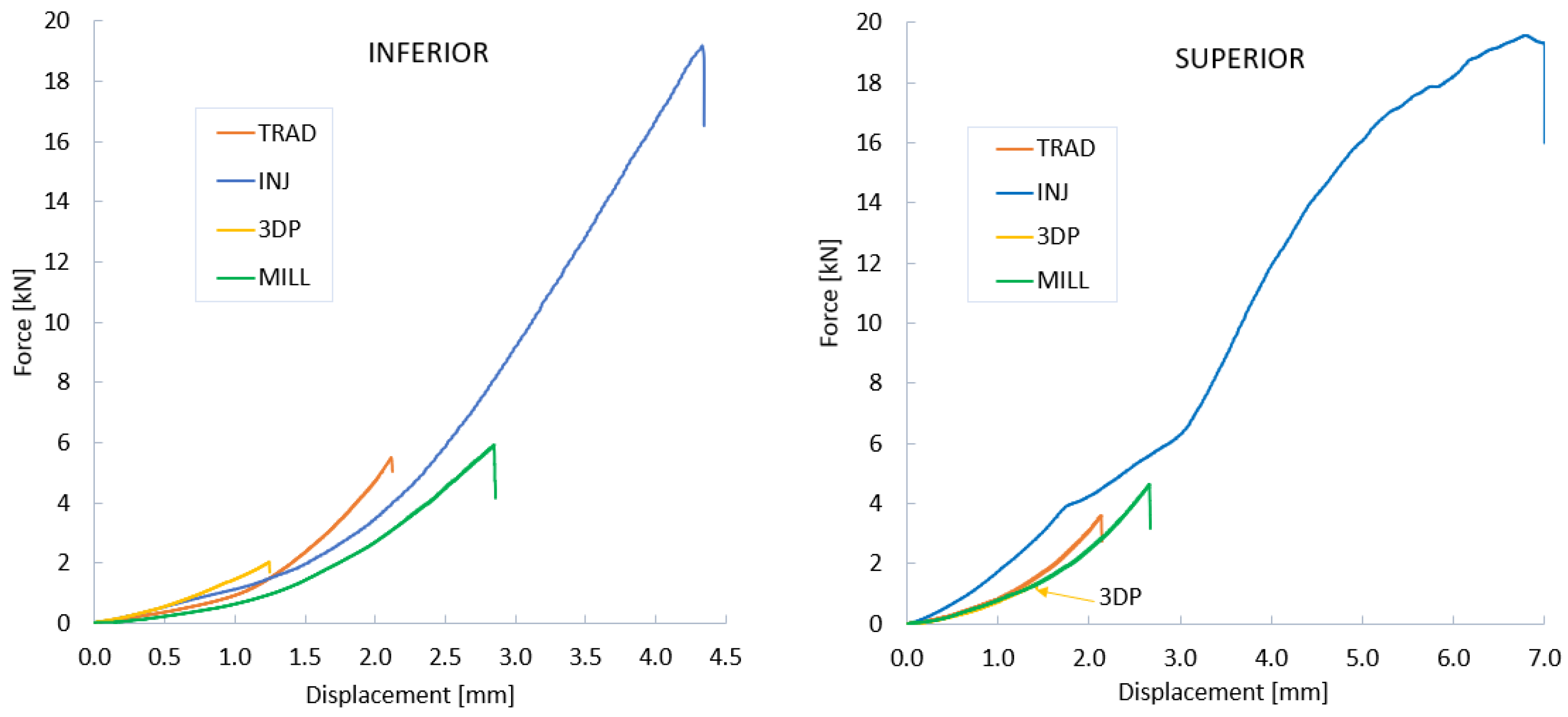

After subjecting all specimens to mechanical testing, the force-displacement curves were obtained. The representative curves for each group in both superior and inferior architectures are presented in the

Figure 6. Here, the aspects of loading increasement according to the displacement can be observed and interpret from the elastic perspective of the construction. Also, the maximum force recorded at break can be identified. High differences can be observed between groups in both superior and inferior architectures. Since the denture models had quasi the same size and shape, the differences recorded in force and displacement belong to the manufacturing technology of each group. The behavior is similar to that obtained in another study carried out by our research group [

25]. Regardless of the technology employed, upper dentures have generally fractured at lower force values compared to lower dentures, likely due to their architectural design.

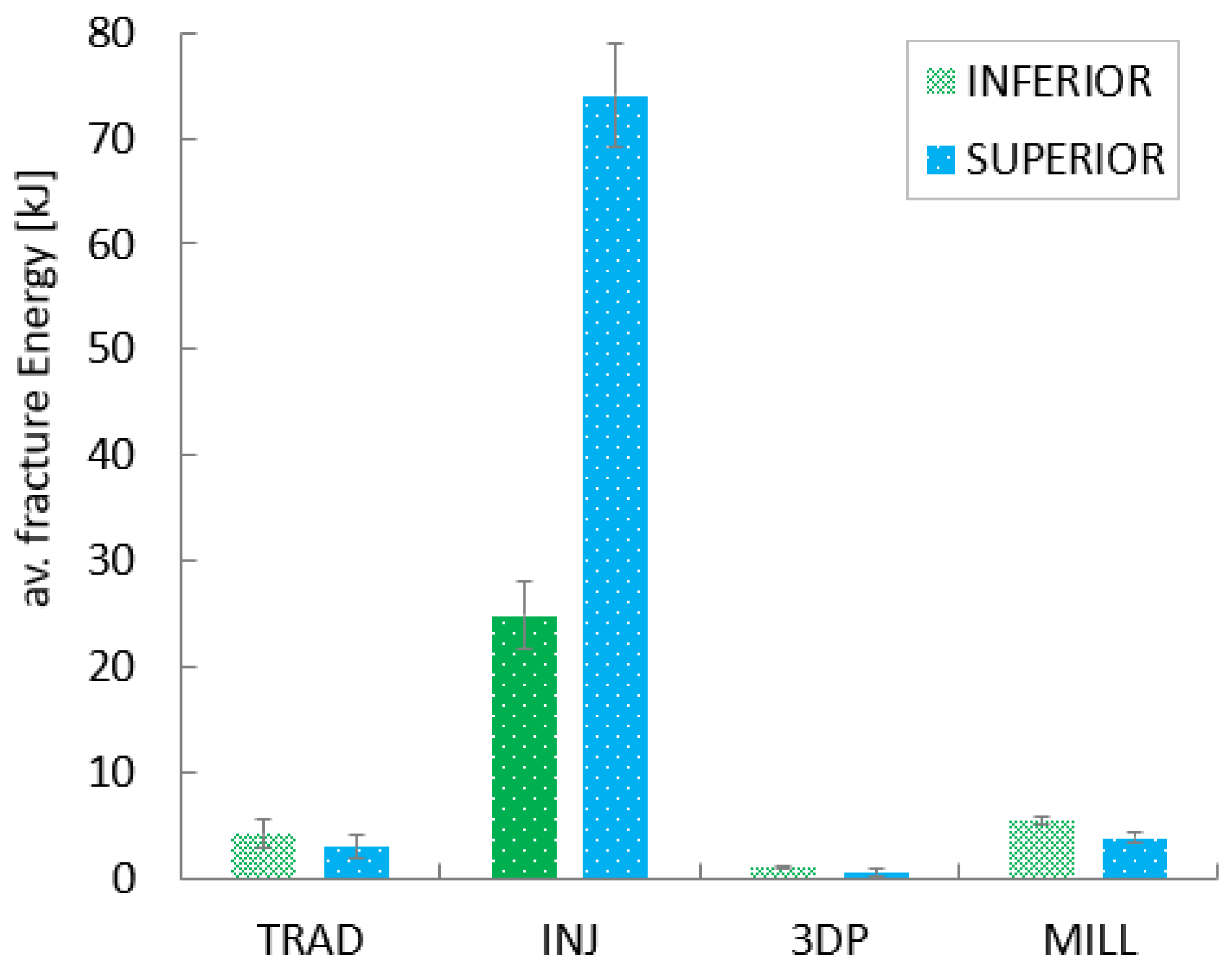

Further data processing consists in computing the fracture energy (W, in kJ). This parameter was computed as the area under the force-displacement curve, and represents the energy absorbed by the denture during the compressive fracture process. High values of W are associated with better performance (toughness) of the denture.

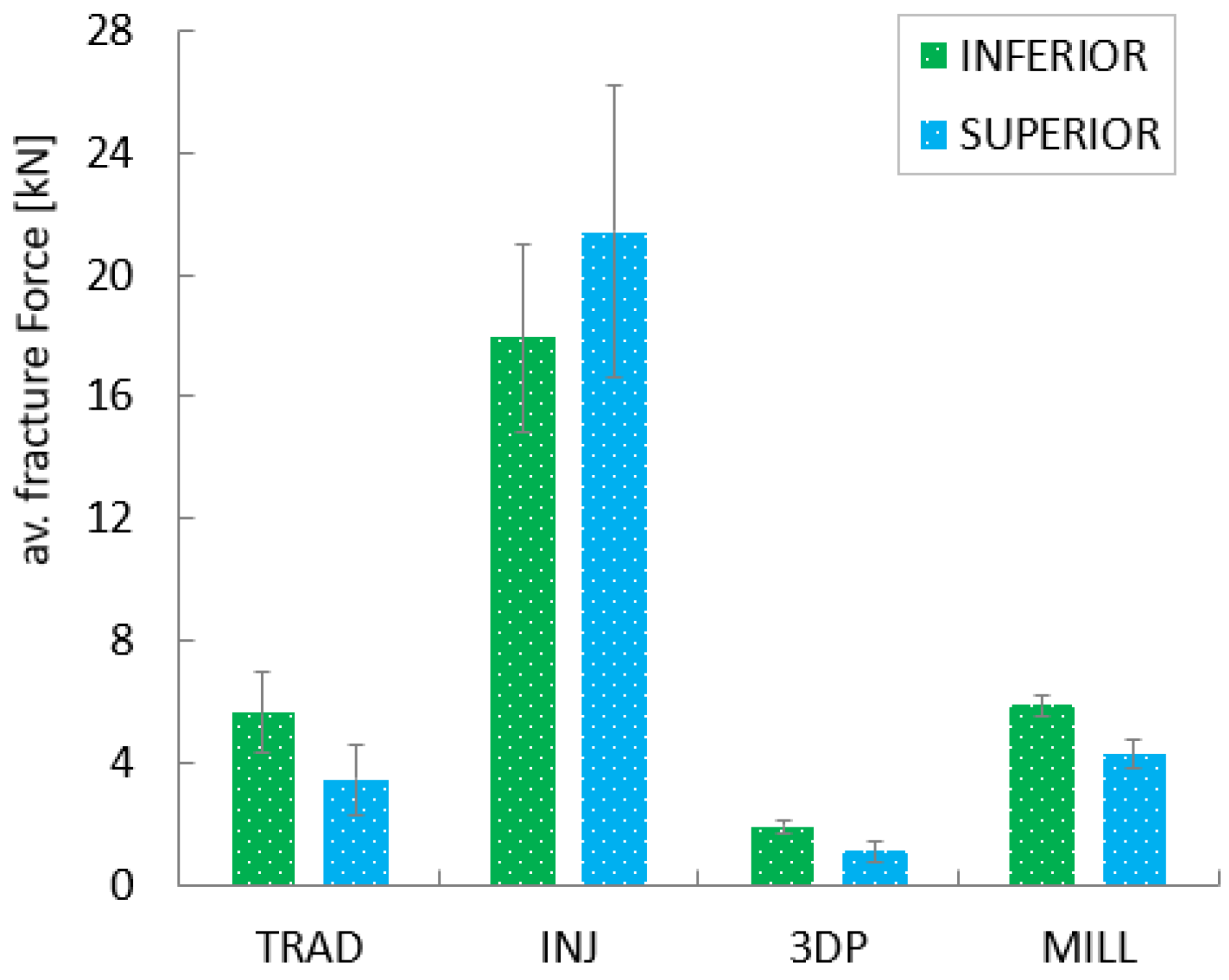

In the case of dentures fabricated using the traditional compression-molding technique, the force required for their fracture ranged between 2.24 kN and 7.01 kN, in both architectures, with a mean value of 4.54 kN. The beaking energy exhibited values between 1.30 kJ and 5.97 kJ, with a mean of 4.18 kJ. For the thermoplastic injection technology, the values are ranging between 14.41 kN and 26.84 kN, with a mean of 17.92 kN for breaking force and between 19.39 kJ and 68.62 kJ, with a mean of 49.47 kJ for breaking energy. The CAD/CAM milled denture get force results in the range of 3.78 kN to 6.23 kN, with a mean of 5.90 kN while the fracture energy ranges from 3.84 kJ to 5.85 kJ, with a mean of 5.40 kJ. The lowest values were observed in the case of 3D printed dentures. The fracture force required ranged between 0.72 kN and 20.24 kN, with an average of 1.51 kN, and the recorded fracture energy was between 0.27 kJ and 1.21 kJ, with a mean value of 1.09 kJ.

Average fracture force and energy, separated on inferior and superior architectures can be observed in the charts of the

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, were also the standard deviations are presented. Here, TRAD stand for traditional technology, INJ for injection technology, 3DP for 3D printing and MILL for CAD/CAM milling technology. A clear domination of the INJ can be observed in both architectures, while poor results both in terms of force and energy are recorded for the 3D printed dentures.

Another important aspect here depicted is the standard deviation for each group, which reveal a relatively unstable property for the thermoplastic injected dentures. Good results here in terms of absolute property and stability of the property can be conferred to CAD/CAM milled group.

The fractography of the samples reveal the fracture surfaces of each group. Here, particularities belonging to the manufacturing technology of the dentures can be observed.

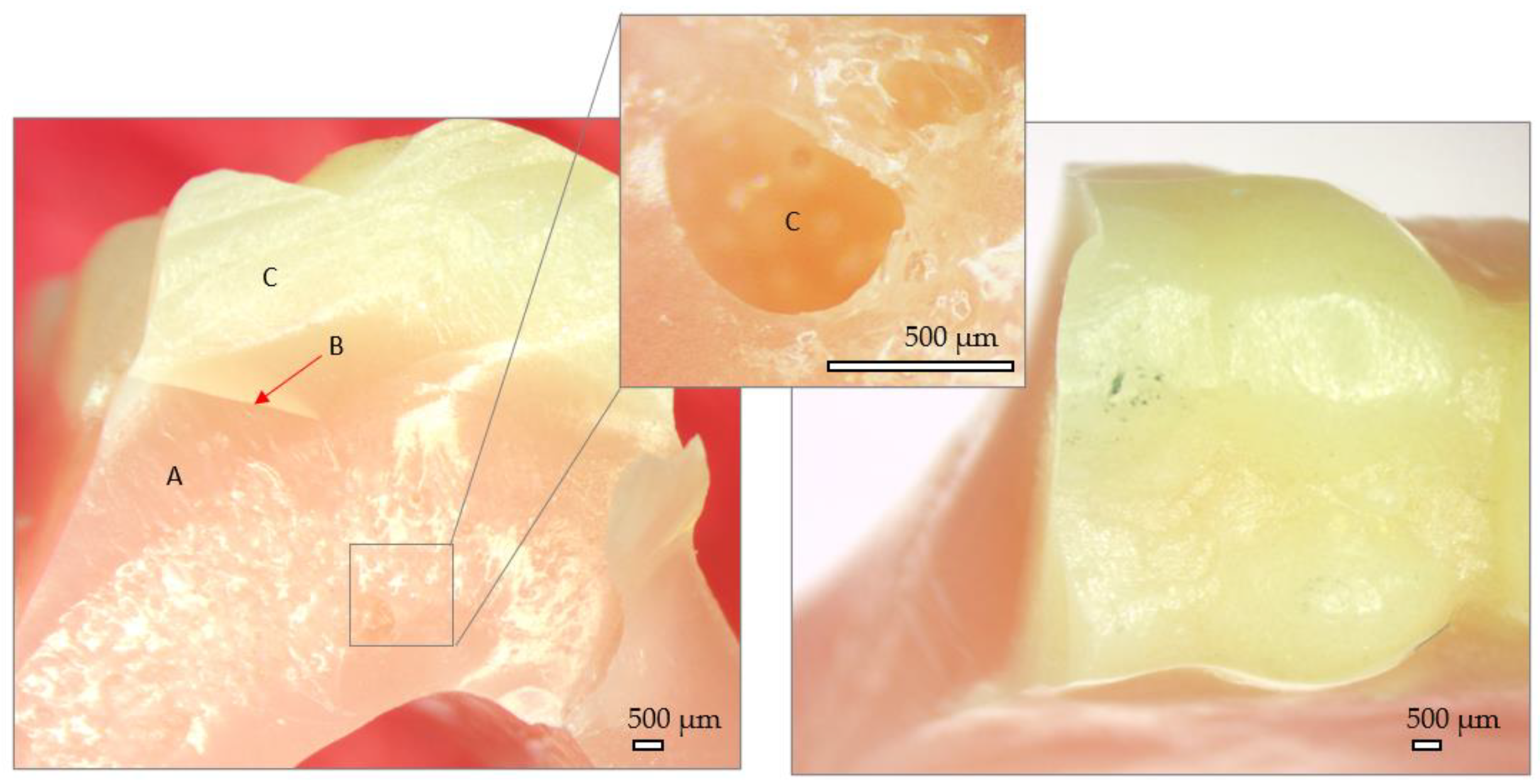

In the

Figure 9, cross section and external aspect of the traditional denture after mechanical testing can be observed. A very good adherence of the artificial teeth to the denture base is visible (B), with no gaps identified. In the denture base however, reaction bubbles are visible (detail C). They lead to pore formation in the volume and are numerous in the fracture plane. The fracture has glassy aspect with a single fracture propagation plane, which indicate a low fracture toughness property. The fracture planes present sharp edges.

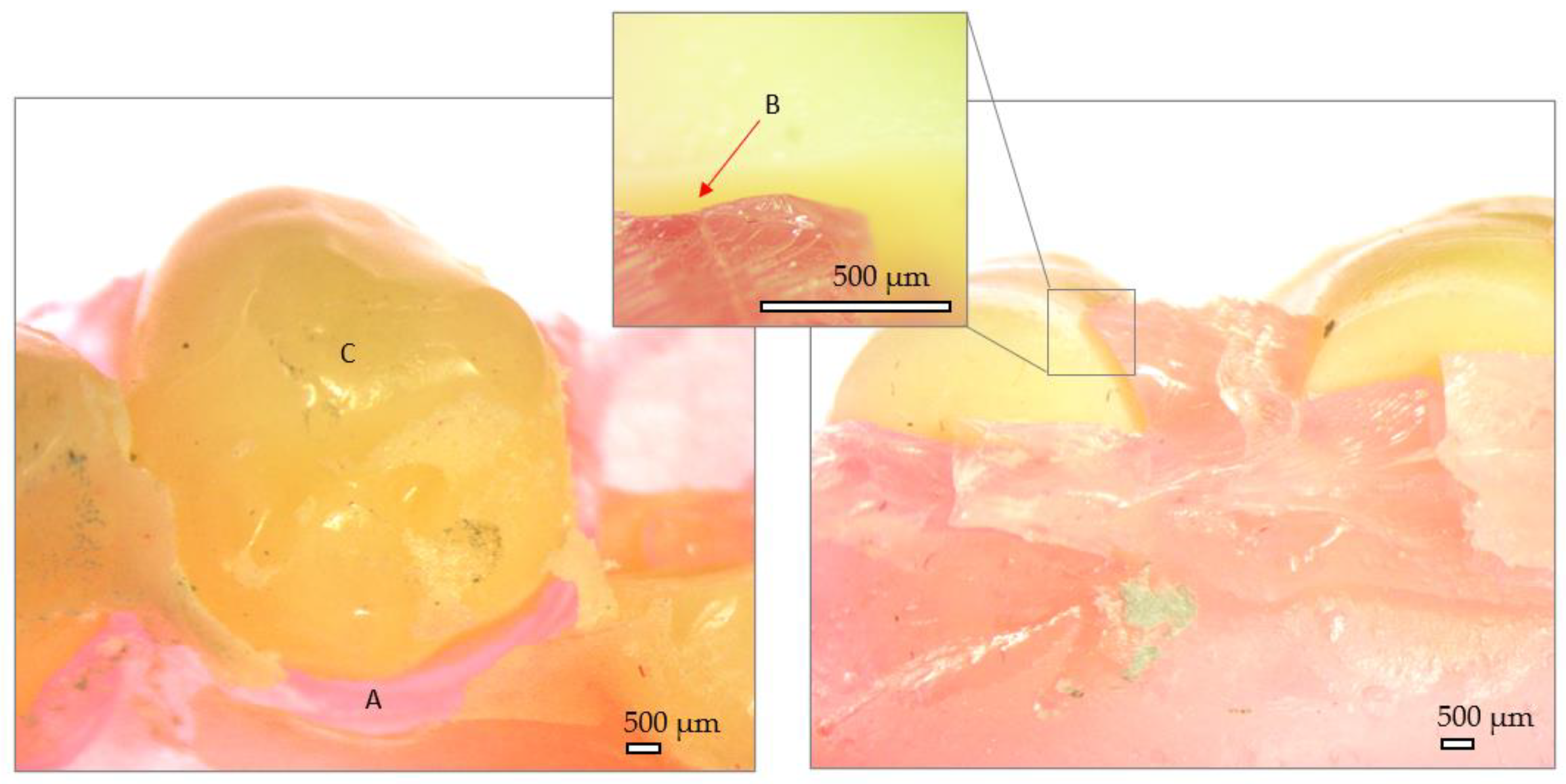

In the

Figure 10, external aspect and fracture site of the injected denture can be observed. The denture base looks continuous, without visible pores in the fracture section. However, areas of no bonding between the artificial teeth and denture base can be observed (B). The fracture site presents no sharp edges and a relatively high fracture toughness is manifested trough small size and random oriented fracture planes.

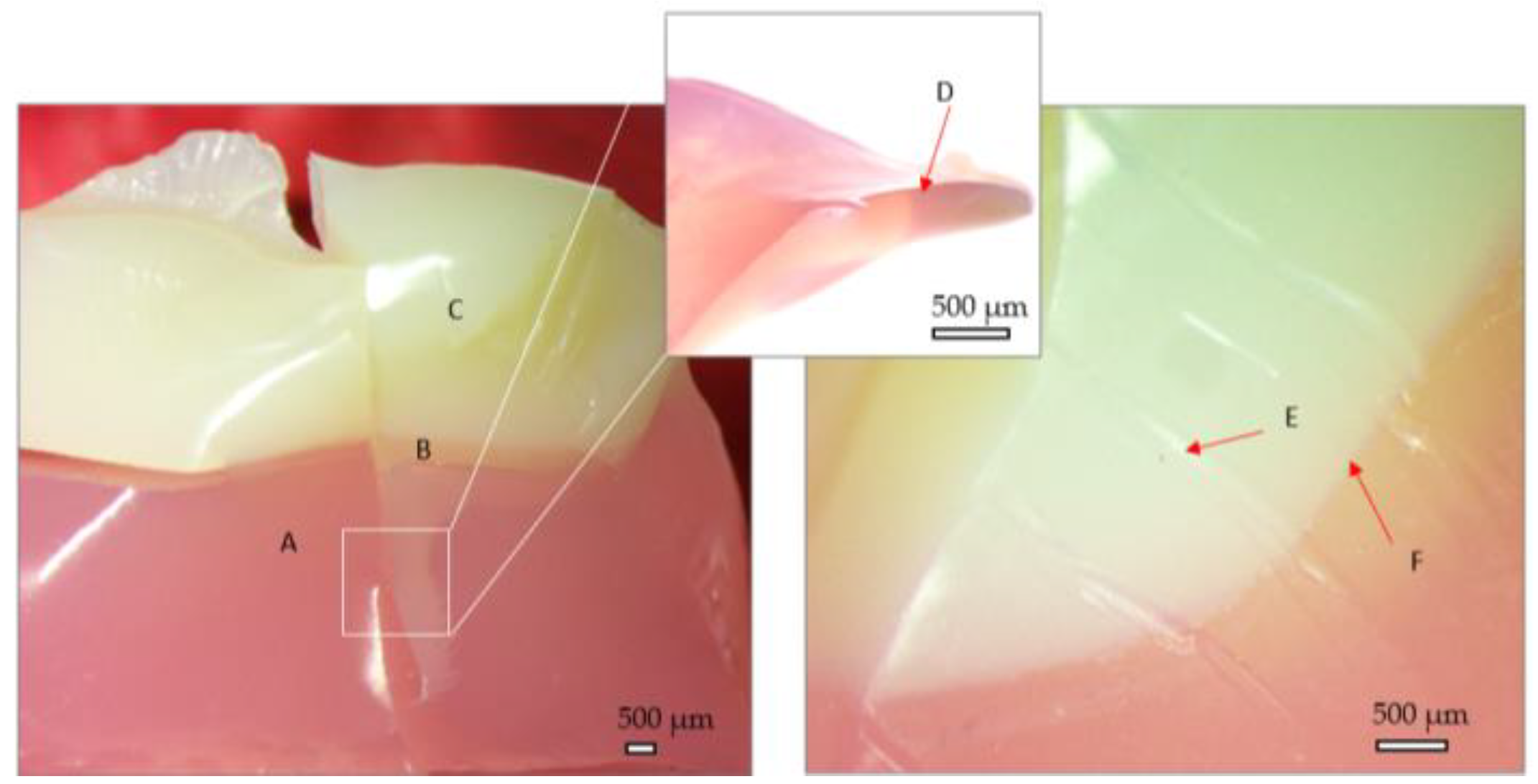

The fractographic results of 3D printed denture is observed in the

Figure 11. The sample presents a glossy aspect both at the surface and in the fracture section which indicate a high surface roughness. There are no visible layers from the manufacturing stage while the adhesive layer is very slim so the transition zone reduced. The fracture section presents hackle marks formed during compression stage (E) while the fracture surfaces present very sharp edges (D). No crushing of the artificial teeth at contact is visible.

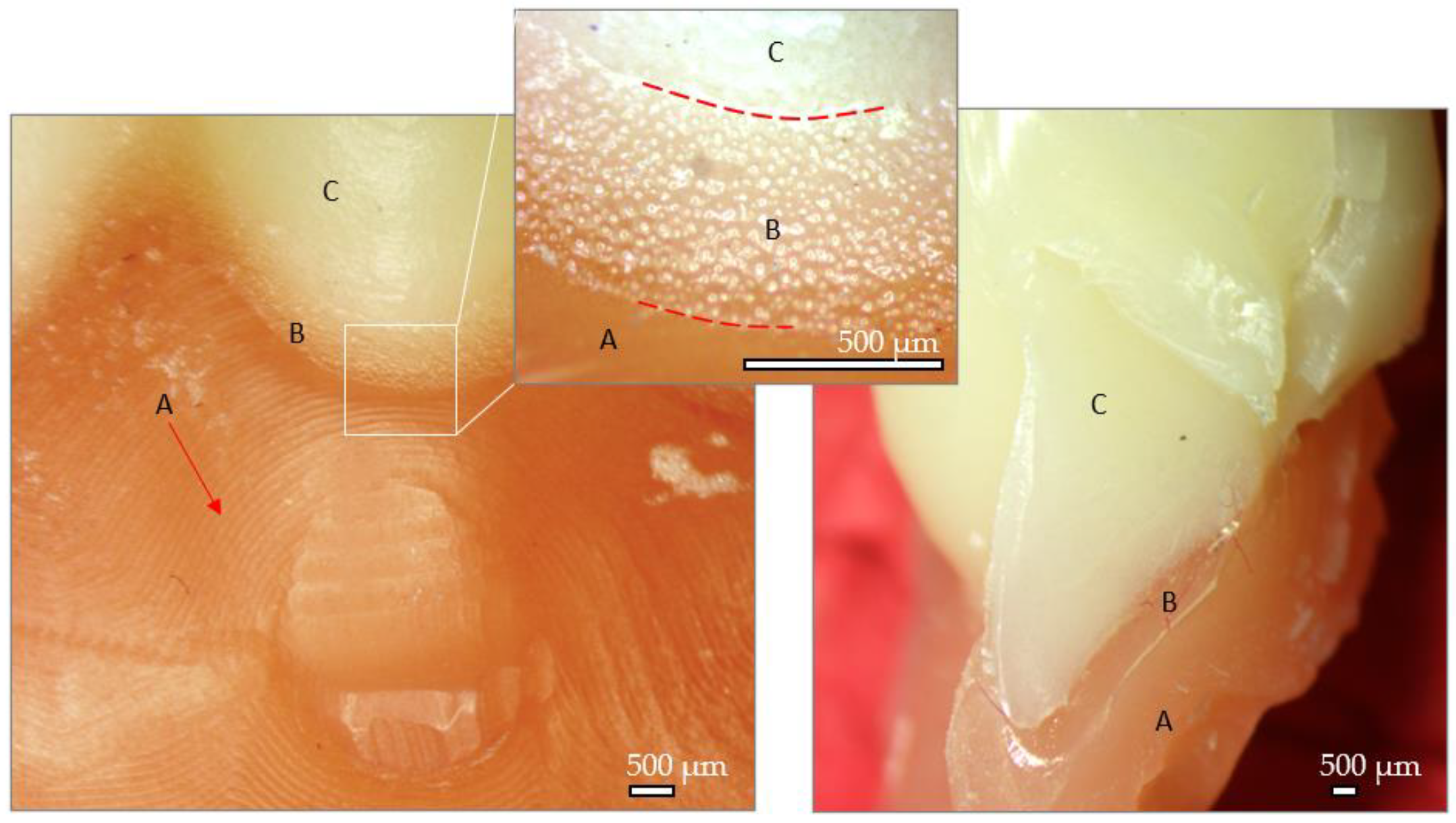

The milled denture after testing can be observed in the

Figure 12. Here, the milling paths in denture base are visible (A) while visible micros scales can be observed on the artificial teeth (C). The adhesive zone presents reaction gas bubbles (B) while some areas are adhesive free. The aspect of the fracture site is more on ductile side.

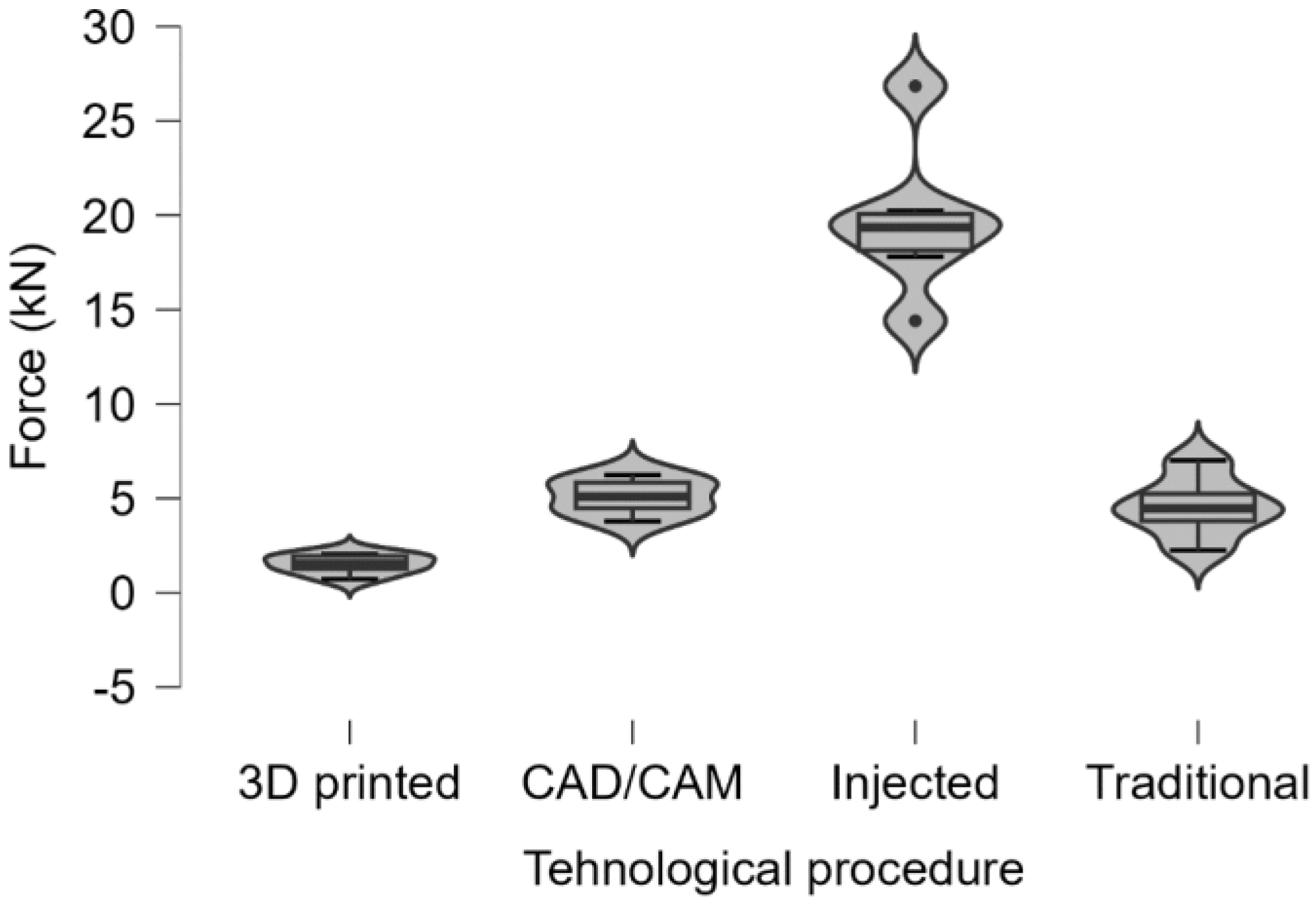

In order to ascertain notable distinctions among the samples manufactured manufactured through the four distinct polymer processing methodologies, the Kruskal-Wallis test was employed with a statistical significance threshold set at p<0.001. Findings from the statistical analysis revealed that both fracture force and energy measurements exhibited a statistically significant elevation in samples generated via the thermoplastic injection procedure in comparison to all other sample groups (

Table 1,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14).

To refine the comparisons between 2 by 2 groups, we applied the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U Test and obtained the following statistical results:

Force and Energy are significantly increased with Injected Technology compared to Traditional, 3D printed and CAD/CAM Technology (Mann-Whitney U test, p=0.004).

Force and energy are significantly increased with Traditional Technology compared to 3D printed technology (Mann-Whitney U test, p=0.004).

Force and energy are significantly increased with CAD/CAM Technology compared to 3D printed technology (Mann-Whitney U test, p=0.004).

There are some limitations to our research, most notably that we only looked at the mechanical analysis of compressive strength. Therefore, it would be wise for future studies to investigate other mechanical characteristics such as fatigue limit, impact strength, and surface microhardness. It should be mentioned that the experimental setup may not precisely replicate clinical conditions.

4. Discussion

Digital dentures are increasingly becoming a possible treatment option with high expectations. Digital dentures have shown acceptable clinical performance, improved retention, reduced number of appointments, less dependence on human factors and ability to save patients' records [

26]. The main challenges for digital dentures include aesthetics, clinical implications and speech difficulties [

27].

CAD/CAM dentures offer a superior treatment option compared to 3D printed dentures considering the better properties such as trueness, fitting and strength. Having said that, its application is still limited. An understanding of these constraints and finding solutions for them are crucial before adopting digital dentures as an applicable alternative to conventional removable dentures [

28]. As part of these limitations stems from the higher initial costs accrued from the technology itself, such as the digital scanner and milling machine, it’s expected that the digital approach will become more accessible as these systems will be better researched, leading to more manufacturers offering improved digital solutions at more competitive prices [

29].

Other authors [

30] compared the flexural properties and the adhesion of Lactobacillus salivarius (LS), Streptococcus mutans (SM), and Candida albicans (CA) on heat-polymerized (CV), CAD-CAM milled (CAD), or 3D-printed (3D) Poly (methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) [

2]. Ultimate Flexural Strength (UFS), Flexural Strain (FS) (%) at Flexural Strength, and Flexural Modulus (FM) of specimens (65.0×10.0×3.3 mm) from each PMMA group (n=6) were calculated by using the 3-point bending test. The surface roughness profiles (R) were measured before and after polishing with a contact profilometer. LS, SM, and CA adhesion on PMMA specimens (n=18) (10 mm in diameter, 3 mm in height) was assessed after 90 minutes and 16 hours by using scanning electron microscopy. The Kruskal-Wallis test with post hoc analysis was performed to compare the groups (alpha=0.05). In conclusion, the CAD-CAM group displayed the best flexural properties, except for Flexural Strain (FS).

It is well known that removable complete dentures provide a favorable environment for the growth of microorganisms. A study conducted by Schmutztler and co. [

31] compared the rate of respiratory microorganism and Candida albicans development on the surface of complete dentures made from PMMA using conventional packing-press procedure versus CAD-CAM milling technology. The conclusion drawn was that biofilm development occurs on the surface of dentures regardless of the fabrication technology employed, with no statistically significant differences observed. The specificity of microorganism development depends more on the patient's individual factors and habits rather than the fabrication technology of the dentures [

31].

Goodacre and colabs [

32] compared pack and press, pour, injection, and CAD-CAM techniques for fabricating dentures to determine which process produces the most accurate and reproducible adaptation. A definitive cast was duplicated to create 40 gypsum casts that were laser scanned before any fabrication procedures were initiated. A master denture was made using the CAD-CAM process and was then used to create a putty mold for the fabrication of 30 standardized wax festooned dentures, 10 for each of the conventional processing techniques (pack and press, pour, injection). Scan files from 10 casts were sent to Global Dental Science, LLC for fabrication of the CAD-CAM test specimens. After specimens for each of the 4 techniques had been fabricated, they were hydrated for 24 hours and the intaglio surface laser scanned. The scan file of each denture was superimposed on the scan file of the corresponding preprocessing cast using surface matching software. Measurements were made at 60 locations, providing evaluation of fit discrepancies at the following areas: apex of the denture border, 6 mm from the denture border, crest of the ridge, palate, and posterior palatal seal. The use of median and interquartile range was used to assess accuracy and reproducibility. They found that the CAD-CAM fabrication process was the most accurate and reproducible denture fabrication technique when compared with pack and press, pour, and injection denture base processing techniques [

32].

The purpose of another in vitro study was to compare the differences in trueness between the CAD-CAM milled and 3D-printed complete dentures [

33]. Two groups of identical maxillary complete dentures were fabricated. A 3D-printed denture group (3DPD) (n=10) and a milled denture group (MDG) (n=10) from a reference maxillary edentulous model. The intaglio surfaces of the fabricated complete dentures were scanned at baseline using a laboratory scanner. The complete dentures were then immersed in an artificial saliva solution for a period of 21 days, followed by a second scan (after immersion in saliva). A third scan (after the wet-dry cycle) was then made after 21 days, during which the complete dentures were maintained in the artificial saliva solution during the day and stored dry at night. The CAD-CAM, milled complete dentures, under the present manufacturing standards, were superior to the rapidly prototyped complete dentures in terms of trueness of the intaglio surfaces. However, further research is needed on the biomechanical, clinical, and patient-centered outcome measures to determine the true superiority of one technique over the other with regard to fabricating complete dentures by CAD-CAM techniques [

33].

The drawbacks of the CAD/CAM and 3D printed dentures were also highlighted in another paper, where material waste, high cost, need for immediate reline and problems with VDO and phonetics were cited for CAD/CAM. In addition to these, 3D printed technology showed disadvantages such as: inconsistencies with occlusion and tooth arrangement, tooth wear, need for additional visits, post insertion adjustments, overall patient dissatisfaction and the need for remake. However, the 3D printed method is more affordable and can produce complex details with high accuracy, while wasting less materials, which is considered to be one of the major benefits of this technique. In cases where retention is hindered by undesirable underlying structures, CAD/CAM dentures are indicated, as their bases show better overall retention, compared to the 3D printed counterparts. This is due to the fact that the material comes pre-polymerized under heat and pressure, so the polymerization shrinkage is minimal, which results in better fitting of the denture and thereby improving retention [

29].

Saponaro found that CAD/CAM dentures have reduced retention, incorrect centric relation and vertical dimension of occlusion. However, these are linked to the difficulty in obtaining a precise impression, along with lack of experience on the part of the practitioners. It was also said that more research into this was needed [

34].

It was indicated that the manufacturing process would affect the mechanical properties and microbial adhesion of PMMA. CAD/CAM dentures showed lower surface roughness before polishing, good flexural properties, and lower microbial adhesion after 90 minutes of incubation, when compared to 3D printed dentures. The required value of 65.0 MPa for flexural strength was exceeded. However, the surface roughness after 16 hours of incubation did not vary between the groups of dentures made using different techniques. Porosity, roughness, volumetric and linear shrinkage were cited for traditional packing press dentures. The manual skill of the operator was mentioned as the cause. CAD/CAM made the workflow standardized, reduced the manufacturing time and brought the flaws that occurred due to manual skill to a minimum [

30].

Lower Candida adhesion values after 90 minutes and 2 hours of incubation were found for milled PMMA, when compared to the traditional dentures [

29].

It is imperative to acknowledge the ongoing necessity for the advancement of dental service strategies, particularly within socioeconomically disadvantaged regions. This imperative is underscored by the predominant utilization of removable prostheses among the elderly demographic. To effectively address the diverse needs within this context, it is crucial to comprehend the multifaceted influences encompassing values, attitudes, oral health literacy, and formal education that shape patterns of dental utilization [

35].

Concerning the fabrication time of removable dentures, it can be stated that the 3D printing technology is the fastest, followed by the injection molding process, then the conventional packing-press procedure, with the longest fabrication time required by the CAD-CAM technology [

36]. From the perspective of the cost price of the dentures, conventional technology is the most economical, followed by the injection molding process, and the 3D printing procedures. Complete dentures obtained through CAD-CAM technology are the most expensive ones. On the other hand, regarding three-dimensional stability, the most durable dentures are those obtained through CAD-CAM technology, followed by those obtained through 3D printing and the thermoplastic injection process. The least dimensionally stable are those made through conventional techniques, such as manual compression molding.

Following the experimentation and statistical analysis, the null hypothesis cannot be rejected, as statistically significant differences were observed between mechanical properties of dentures produced using distinct techniques. However, the most favorable outcomes regarding property stability were observed in dentures fabricated through CAD/CAM milling techniques. Dentures obtained via the traditional compression molding method provide satisfactory results at a significantly lower cost compared to the other discussed technologies.

5. Conclusions

The manufacturing of new dentures for a fully edentulous patient has been shown to increase satisfaction levels and enhance quality of life, both functionally and esthetically. Patient satisfaction in a new complete denture, a multifactorial aspect, is a strong determinant of success and one of the primary goals of this type of treatment, which should be achieved by all practitioners.

Following the mechanical testing of all samples, they fractured under the influence of a distinct force (unique to each specimen), rather than deforming via flow, as typically observed in plastic materials. Consistent with findings from a previous study conducted by our research team [

25], the fracture surfaces appeared clean, suggesting the inherent brittleness of the material irrespective of the manufacturing procedure.

Regardless of the technology employed, upper dentures have generally fractured at lower force values compared to lower dentures, likely due to their architectural design.

High values of fracture energy are associated with better performance (toughness) of the denture.

A clear domination of the thermoplastic injection technology can be observed in both architectures (lower and upper dentures), while poor results both in terms of force and energy are recorded for the 3D printed dentures.

Another important aspect depicted is the standard deviation for each group, which reveal a relatively unstable property for the thermoplastic injected dentures. Good results here in terms of absolute property and stability of the property can be conferred to CAD/CAM milled group.

The statistical analysis highlighted that the force and fracture energy recorded in the case of samples produced by thermoplastic injection procedure were significantly higher compared to all other samples.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M., A.S., C.S., M.-L.N., and E.L.C., methodology, C.M., D.M.P., M.R., C.S., M.-L.N.; E.L.C., investigation, A.S., G.K., V.F.D., sample preparation, C.M., A.V.A., E.R.A. and D.M.P; data and statistical analysis, A.S. and A.T.., supervision and project administration: M.T.L., C.S., E.L.C., M.R. and M.-L.N., writing—original draft: A.V.A., E.R.A., M.L.N., C.S., E.L.C., V.-F.D and M.T.L.; writing—review and editing: M.T.L., C.S., E.L.C. and M.L.N.;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was sustained by the ”Victor Babeş” University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Timişoara, Romania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge VICTOR BABEŞ UNIVERSITY OF MEDICINE AND PHARMACY TIMIŞOARA for their support in covering the costs of publication for this research paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Olshansky, S.J.; Carnes, B.A. Ageing and Health. The Lancet 2010, 375, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komagamine, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Iwaki, M.; Minakuchi, S.; Kanazawa, M. Effect of New Complete Dentures and Simple Dietary Advice on Cognitive Screening Test among Edentulous Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peres, M.A.; Macpherson, L.M.D.; Weyant, R.J.; Daly, B.; Venturelli, R.; Mathur, M.R.; Listl, S.; Celeste, R.K.; Guarnizo-Herreño, C.C.; Kearns, C.; et al. Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. The Lancet 2019, 394, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations (2019) World population prospects 2019: highlights. New York, NY: United Nations.

- Khan, A.A.; Fareed, M.A.; Alshehri, A.H.; Aldegheishem, A.; Alharthi, R.; Saadaldin, S.A.; Zafar, M.S. Mechanical properties of the modified denture base materials and polymerization methods: a systematic review. IJMS 2022, 23, 5737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, U.; Karim, K.J.B.A.; Buang, N.A. A review of the properties and applications of poly (methyl methacrylate) (PMMA). Polymer Reviews 2015, 55, 678–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, B.C.; Chen, J.-H.; Kontogiorgos, E.D.; Murchison, D.F.; Nagy, W.W. Flexural strength of denture base acrylic resins processed by conventional and CAD-CAM methods. J Prosthet Dent. 2020, 123, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagger, D.C.; Jagger, R.G.; Allen, S.M.; Harrison, A. An investigation into the transverse and impact strength of `high strength’ denture base acrylic resins. J Oral Rehabil 2002, 29, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, M.S. Prosthodontic Applications of Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA): An Update. Polymers 2020, 12, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucar, Y.; Akova, T.; Aysan, I. Mechanical properties of polyamide versus different PMMA denture base materials: polyamide as denture base material. J Prosthodont 2012, 21, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, C.; Sanchez, E.; Azer, S.S.; Uribe, J.M. Comparative study of the transverse strength of three denture base materials. J Dent. 2007, 35, 930–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neshati, A.; Kouchak Dezfouli, N.; Sadafi, M.; Omidi, S. Compressive Strength of Three Types of Heat-Cure Acrylic Resins: Acropars, Acrosun, and Meliodent. J Res Dent Maxillofac Sci 2021, 6, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidan, S.; Silikas, N.; Alhotan, A.; Haider, J.; Yates, J. Investigating the mechanical properties of zro2-impregnated pmma nanocomposite for denture-based applications. Materials 2019, 12, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydogan Ayaz, E.; Durkan, R. Influence of acrylamide monomer addition to the acrylic denture-base resins on mechanical and physical properties. Int J Oral Sci. 2013, 5, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.H.; Chen, S.; Grymak, A.; Waddell, J.N.; Kim, J.J.; Choi, J.J.E. Fibre-reinforced and repaired PMMA denture base resin: effect of placement on the flexural strength and load-bearing capacity. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2021, 124, 104828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayran, Y.; Keskin, Y. Flexural strength of polymethyl methacrylate copolymers as a denture base resin. Dent. Mater. J. 2019, 38, 678–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranganathan, A.; Karthigeyan, S.; Chellapillai, R.; Rajendran, V.; Balavadivel, T.; Velayudhan, A. Effect of Novel Cycloaliphatic Comonomer on the Flexural and Impact Strength of Heat-Cure Denture Base Resin. J Oral Sci 2021, 63, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, O.; Ozdemir, A.K.; Turgut, M.; Boztug, A.; Sumer, Z. Investigation of flexural strength and cytotoxicity of acrylic resin copolymers by using different polymerization methods. J Adv Prosthodont 2015, 7, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Zhao, D.; Wu, Y.; Xu, C. Effect of polyimide addition on mechanical properties of PMMA-based denture material. Dent Mater J. 2017, 36, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, B.; Azak, A.N.; Alp, G.; Ekşi, H. Use of CAD-CAM technology for the fabrication of Yilmaz, B. ; Azak, A.N.; Alp, G.; Ekşi, H. Use of CAD-CAM technology for the fabrication of complete dentures: an alternative technique. J Prosthet Dent. 2017, 118, 140–143. [Google Scholar]

- Janeva, N.M.; Kovacevska, G.; Elencevski, S.; Panchevska, S.; Mijoska, A.; Lazarevska, B. Advantages of CAD/CAM versus conventional complete dentures - a review. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018, 6, 1498–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Limírio, J.P.J.; de Luna Gomes, J.M.; Alves Rezende, M.C.R.; Lemos, C.A.A.; Rosa, C.D.D.R.D.; Pellizzer, E.P. Mechanical properties of polymethyl methacrylate as a denture base: conventional versus CAD-CAM resin – a systematic review and meta-analysis of in vitro studies. J Prosthet Dent. 2022, 128, 1221–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prpić, V.; Schauperl, Z.; Ćatić, A.; Dulčić, N.; Čimić, S. Comparison of mechanical properties of 3d-printed, cad/cam, and conventional denture base materials. J Prosthodont 2020, 29, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Dwairi, Z.N.; Al Haj Ebrahim, A.A.; Baba, N.Z. A Comparison of the Surface and Mechanical Properties of 3D Printable Denture-Base Resin Material and Conventional Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA). J Prosthodont 2022, 32, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modiga, C.; Manole, M.; Tănase, A.D.; Leretter, M.T.; Crăciunescu, E.L.; Pop, D.M.; Chiş, A.C.; Sinescu, C.; Romînu, M.; Negruţiu, M.L. The impact of fabrication methodologies on the flexural strength of complete dentures: an investigation into technological influences. Rom. J. Oral Rehabil. 2024, 16, 333–337. [Google Scholar]

- Zupancic Cepic, L.; Gruber, R.; Eder, J.; Vaskovich, T.; Schmid-Schwap, M.; Kundi, M. Digital versus Conventional Dentures: A Prospective, Randomized Cross-Over Study on Clinical Efficiency and Patient Satisfaction. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardelean, L.C.; Rusu, L.C.; Tigmeanu, C.V.; Negrutiu, M.L.; Pop, D.M. Advances in Dentures: Novel Polymeric Materials and Manufacturing Technologies [Internet]. Advances in Dentures - Prosthetic Solutions, Materials and Technologies [Working Title]. IntechOpen; 2023.

- Smith, P.B.; Perry, J.; Elza, W. Economic and Clinical Impact of Digitally Produced Dentures. J Prosthodont 2021, 30, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhallak, K.; Hagi-Pavli, E.; Nankali, A. A review on clinical use of CAD/CAM and 3D printed dentures. Br Dent J 2023, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiore, A.D.; Meneghello, R.; Brun, P.; et al. Comparison of the flexural and surface properties of milled, 3D-printed, and heat polymerized PMMA resins for denture bases: An in vitro study. J Prosthodont Res. 2022, 66, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmutzler, A.; Stingu, C.S.; Günther, E.; Lang, R.; Fuchs, F.; Koenig, A.; Rauch, A.; Hahnel, S. Attachment of Respiratory Pathogens and Candida to Denture Base Materials—A Pilot Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodacre, B.J.; Goodacre, C.J.; Baba, N.Z.; Kattadiyil, M.T. Comparison of denture base adaptation between CAD-CAM and conventional fabrication techniques. J Prosthet Dent. 2016, 116, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalberer, N.; Mehl, A.; Schimmel, M.; Müller, F.; Srinivasan, M. CAD-CAM milled versus rapidly prototyped (3D-printed) complete dentures: An in vitro evaluation of trueness. J Prosthet Dent. 2019, 121, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saponaro, P.C.; Yilmaz, B.; Johnston, W.; Heshmati, R.H.; McGlumphy, E.A. Evaluation of patient experience and satisfaction with CAD-CAM-fabricated complete denture: a retrospective survey study. J Prosthet Dent 2016, 116, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sfeatcu, R.; Balgiu, B.A.; Mihai, C.; Petre, A.; Pantea, M.; Tribus, L. Gender Differences in Oral Health: Self-Reported Attitudes, Values, Behaviours and Literacy among Romanian Adults. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grachev, D.I.; Zolotnitsky, I.V.; Stepanov, D.Y.; Kozulin, A.A.; Mustafaev, M.S.; Deshev, A.V.; Arutyunov, D.S.; Tlupov, I.V.; Panin, S.V.; Arutyunov, S.D. Ranking Technologies of Additive Manufacturing of Removable Complete Dentures by the Results of Their Mechanical Testing. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

The figure illustrates the fabrication of PMMA traditional dentures: (a) Gypsum is poured into the preliminary impression; (b) Custom photopolymerizing resin impression trays are fabricated; (c) Wax rims have been applied to the final models; (d) Artificial teeth are sited; (e) The wax up is flasked; (f)Isolation prevents PMMA from sticking to the gypsum; (g) PMMA is packed in the void space left after the wax melted; (h) The denture base material filled flask is pressed to ensure proper adaptation of the material to the mold; (i) The flask is opened and the denture base is removed. The denture undergoes finishing and polishing processes;.

Figure 1.

The figure illustrates the fabrication of PMMA traditional dentures: (a) Gypsum is poured into the preliminary impression; (b) Custom photopolymerizing resin impression trays are fabricated; (c) Wax rims have been applied to the final models; (d) Artificial teeth are sited; (e) The wax up is flasked; (f)Isolation prevents PMMA from sticking to the gypsum; (g) PMMA is packed in the void space left after the wax melted; (h) The denture base material filled flask is pressed to ensure proper adaptation of the material to the mold; (i) The flask is opened and the denture base is removed. The denture undergoes finishing and polishing processes;.

Figure 2.

The figure illustrates the process of the fabrication of PMMA injected dentures: (a) Wax-up on the final cast models; (b) Artificial teeth are fitted onto the wax-up, which is then mounted on a semi adjustable articulator; (c) The model and wax-up are flasked. Note the wax injection nozzle that will leave a void space through which PMMA will be injected; (d) After the wax melted a hollow space is left that will be filled by PMMA; (e) and (f)The injection system with the cartridges; (g) The dentures right after deflasking; (h) and (i) The final injected dentures after injection nozzle is trimmed and rough edges are smoothed out. Also, the denture undergoes finishing and polishing.

Figure 2.

The figure illustrates the process of the fabrication of PMMA injected dentures: (a) Wax-up on the final cast models; (b) Artificial teeth are fitted onto the wax-up, which is then mounted on a semi adjustable articulator; (c) The model and wax-up are flasked. Note the wax injection nozzle that will leave a void space through which PMMA will be injected; (d) After the wax melted a hollow space is left that will be filled by PMMA; (e) and (f)The injection system with the cartridges; (g) The dentures right after deflasking; (h) and (i) The final injected dentures after injection nozzle is trimmed and rough edges are smoothed out. Also, the denture undergoes finishing and polishing.

Figure 3.

The figure illustrates the process of the fabrication of printed dentures: (a) Wax rims and model scan; (b) Teeth selection in CR (Centric Relation); (c) Final design of the denture base and teeth; (d) and (e) The printer and the resin cartridges with photopolymerizable resins; (f), (g), (h) and (i) The dentures during and right after printing.

Figure 3.

The figure illustrates the process of the fabrication of printed dentures: (a) Wax rims and model scan; (b) Teeth selection in CR (Centric Relation); (c) Final design of the denture base and teeth; (d) and (e) The printer and the resin cartridges with photopolymerizable resins; (f), (g), (h) and (i) The dentures during and right after printing.

Figure 4.

The figure illustrates the workflow for CAD/CAM dentures using Ivotion (Ivoclar): (a),(b) and (c) Digital design of the dentures with teeth setting; (d), (e) and (f) Individual arches can be inspected separately; (g)The monolithic disk is milled in PrograMill milling machine; (h) and (i) The milled dentures pending finishing;.

Figure 4.

The figure illustrates the workflow for CAD/CAM dentures using Ivotion (Ivoclar): (a),(b) and (c) Digital design of the dentures with teeth setting; (d), (e) and (f) Individual arches can be inspected separately; (g)The monolithic disk is milled in PrograMill milling machine; (h) and (i) The milled dentures pending finishing;.

Figure 5.

Testing setup and fractured denture after compressive mechanical test.

Figure 5.

Testing setup and fractured denture after compressive mechanical test.

Figure 6.

Mean Force-displacement curves for inferior and superior dentures, in compression.

Figure 6.

Mean Force-displacement curves for inferior and superior dentures, in compression.

Figure 7.

Average fracture force for each group in both architectures.

Figure 7.

Average fracture force for each group in both architectures.

Figure 8.

Average fracture energy for each group in both architectures.

Figure 8.

Average fracture energy for each group in both architectures.

Figure 9.

Stereo fractography of traditional denture:.

Figure 9.

Stereo fractography of traditional denture:.

Figure 10.

Stereo fractography of injected denture:.

Figure 10.

Stereo fractography of injected denture:.

Figure 11.

Stereo fractography of 3D printed denture:.

Figure 11.

Stereo fractography of 3D printed denture:.

Figure 12.

Stereo fractography of milled denture.

Figure 12.

Stereo fractography of milled denture.

Figure 13.

Boxplots with violins representation for the force (kN) values, comparative between the technological procedures.

Figure 13.

Boxplots with violins representation for the force (kN) values, comparative between the technological procedures.

Figure 14.

Boxplots with violins representation for the energy (kJ) values, comparative between the technological procedures.

Figure 14.

Boxplots with violins representation for the energy (kJ) values, comparative between the technological procedures.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for force and energy for the technological procedures and p-values resulting from the comparisons with the Kruskal-Wallis test (SD-standard deviation, Q1,Q3-the first and the third quartile).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for force and energy for the technological procedures and p-values resulting from the comparisons with the Kruskal-Wallis test (SD-standard deviation, Q1,Q3-the first and the third quartile).

| Measured parameter |

Tehnological procedure |

Mean±SD |

Median (Q1-Q3) |

Mean Rank |

p |

| Force (kN) |

3D printed |

1.51±0.52 |

1.51(1.26-1.94) |

3.50 |

<0.001 |

| CAD/CAM |

5.09±0.96 |

5.09(4.48-5.84) |

13.50 |

| Injected |

19.67±4.08 |

19.36(18.14-20.07) |

21.50 |

| Traditional |

4.54±1.62 |

4.46(3.8-5.24) |

11.50 |

| Energy (kJ) |

3D printed |

0.81±0.36 |

0.82(0.62-1.09) |

3.50 |

<0.001 |

| CAD/CAM |

4.63±0.92 |

4.57(3.92-5.28) |

13.83 |

| Injected |

49.47±28.09 |

46.86(27.62-67.97) |

21.50 |

| Traditional |

3.58±1.69 |

3.29(2.72-4.66) |

11.17 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).