Submitted:

14 May 2024

Posted:

16 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

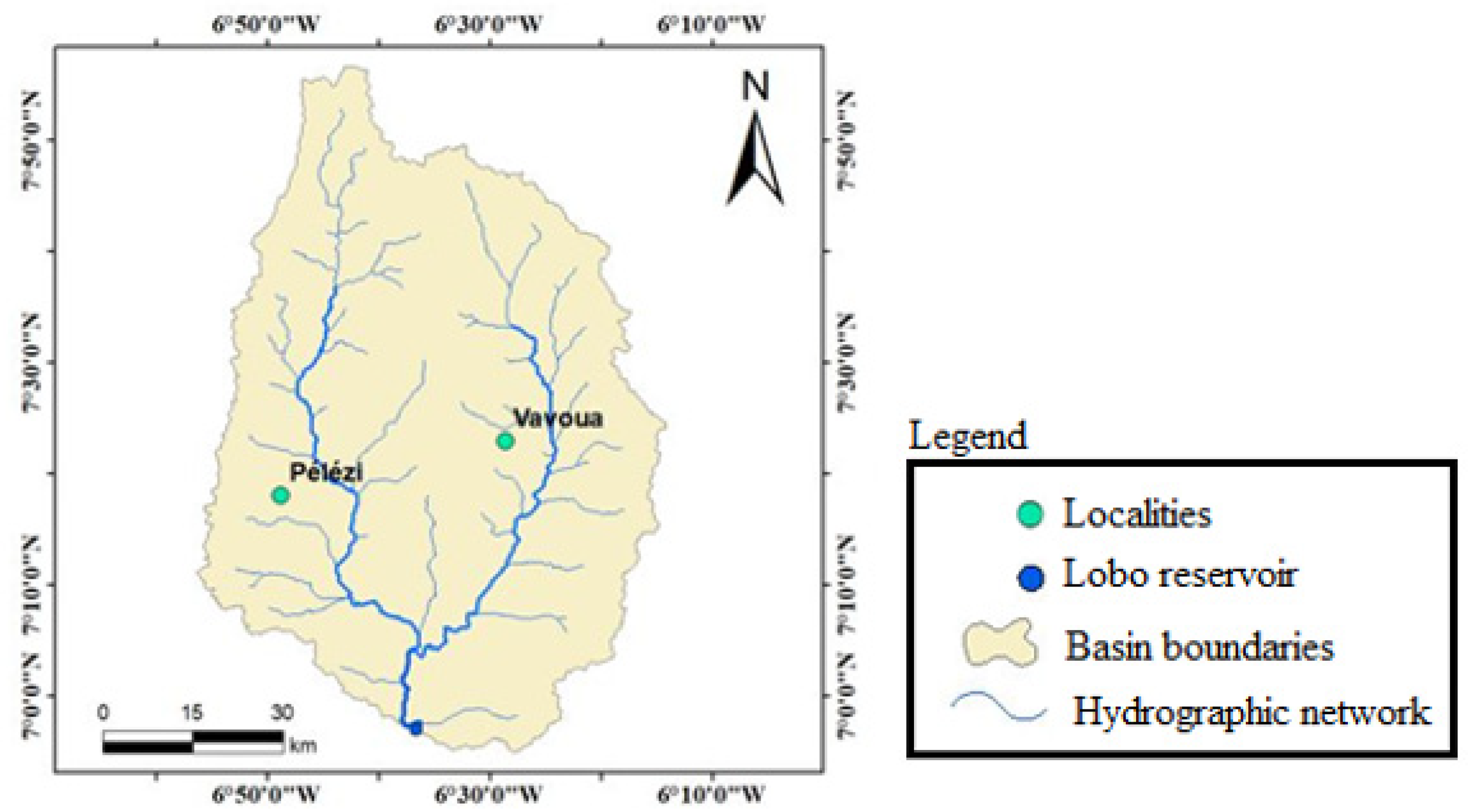

2.1.1. Study Site

2.1.2. Data

2.1.3. Work Tools

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Description of the VFSMOD Model

- -

- Hydrology

- -

- Sediment and chemical transport

2.2.2. Steps

3. Results

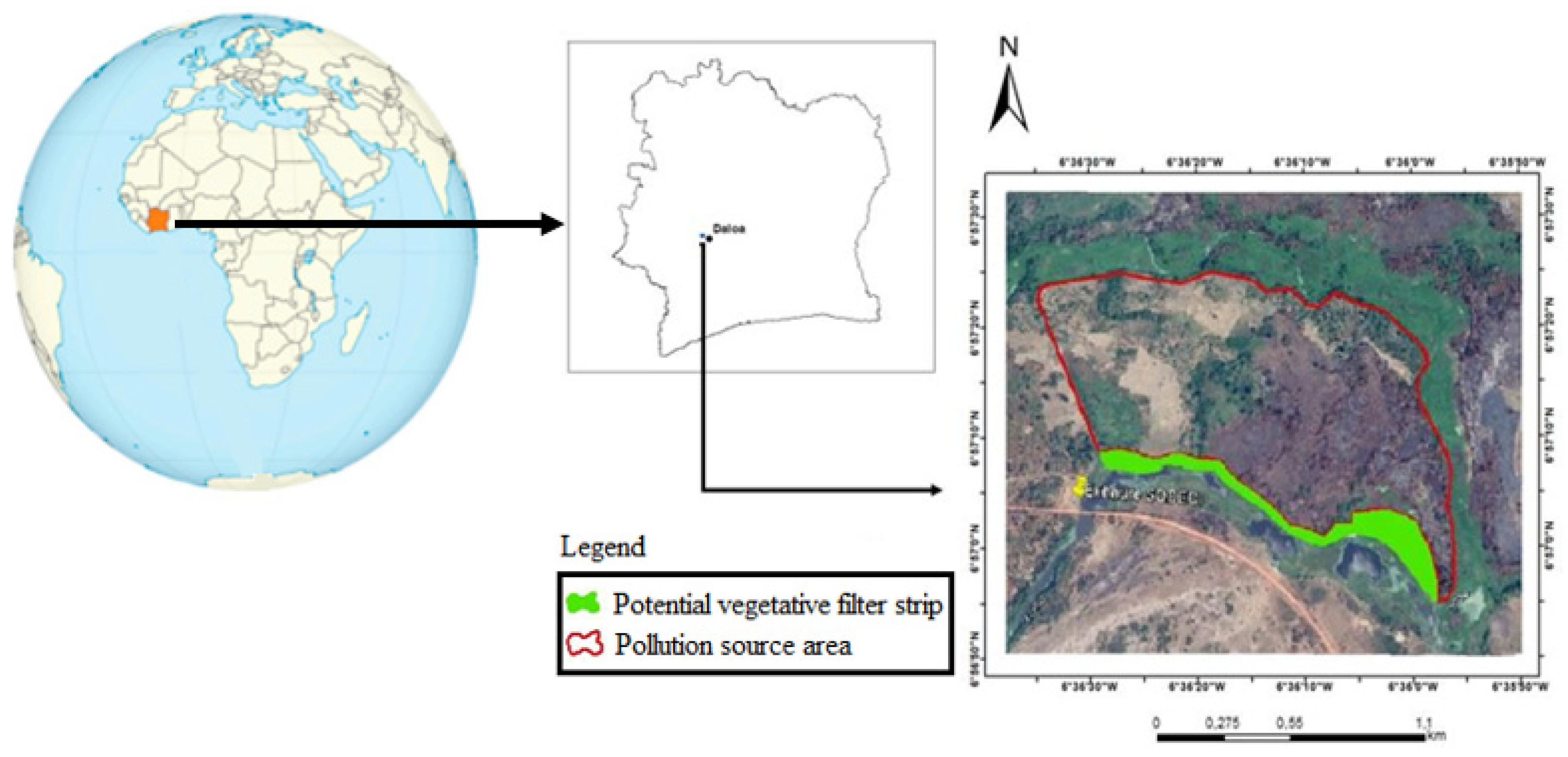

3.1. Geometry of the Contributing Surface Area (Source of Pollution)

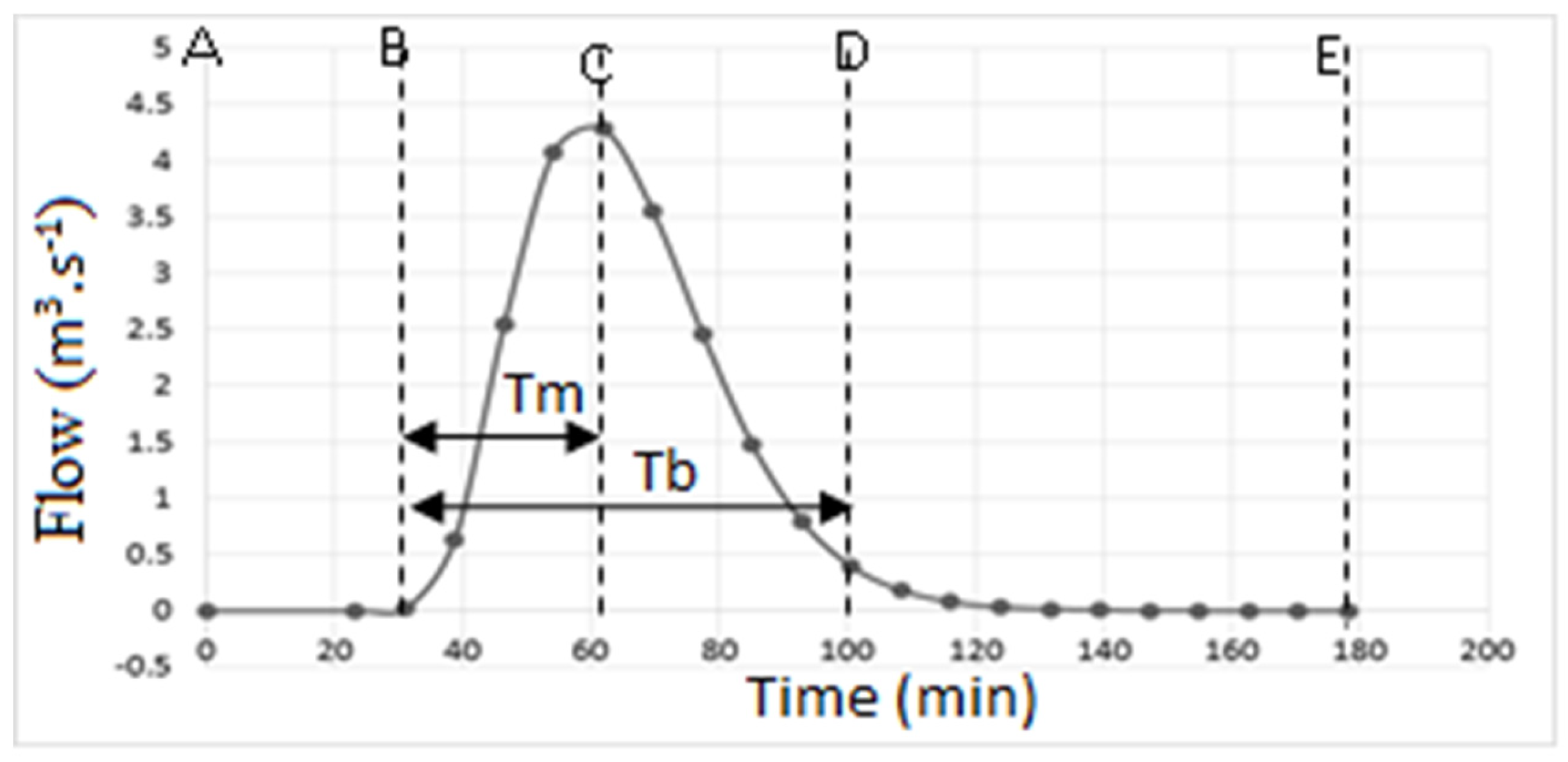

3.2. Unit Hydrograph (UH) of the Contributing Area

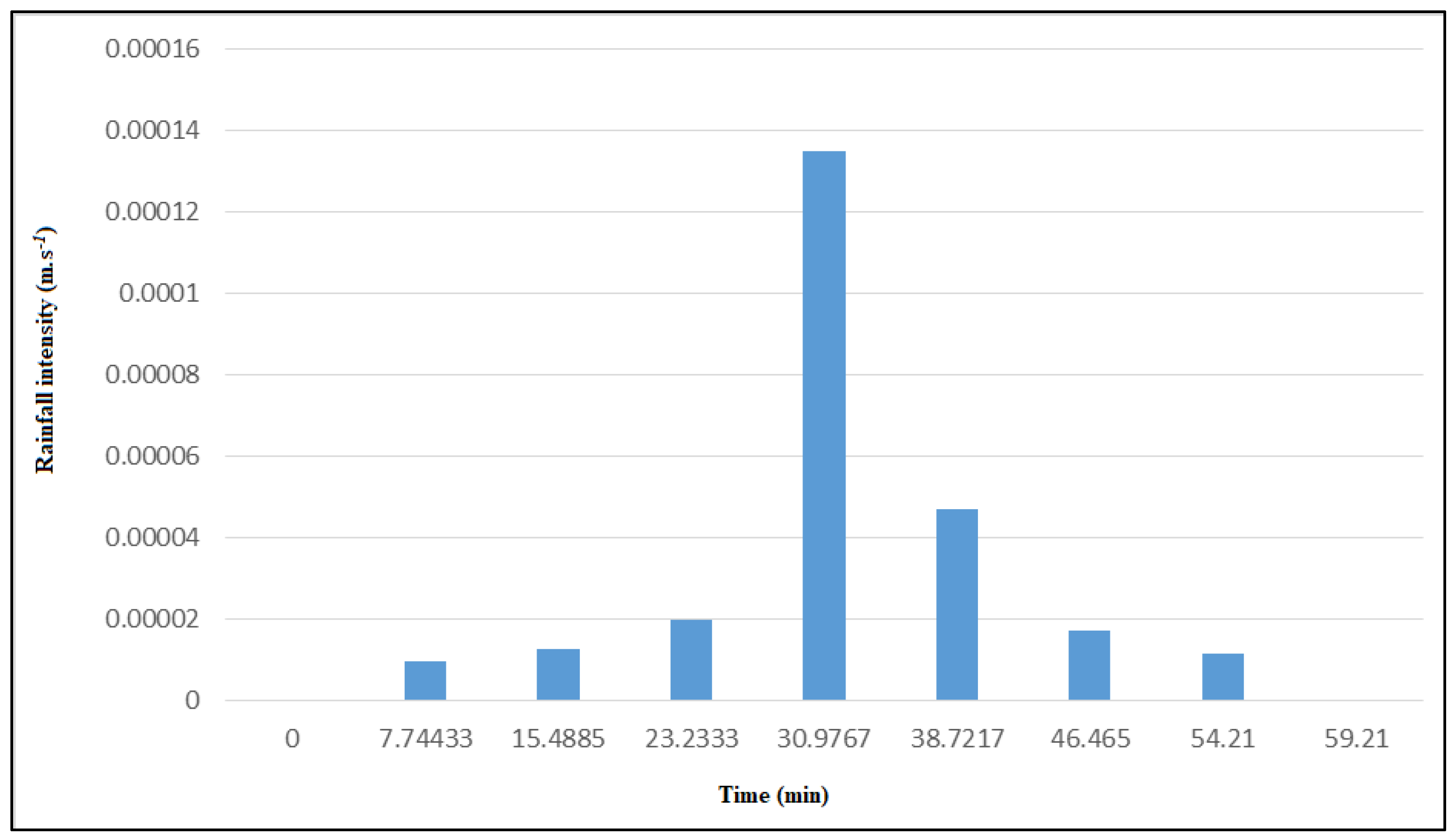

3.3. Hyetogram of the Contributing Area

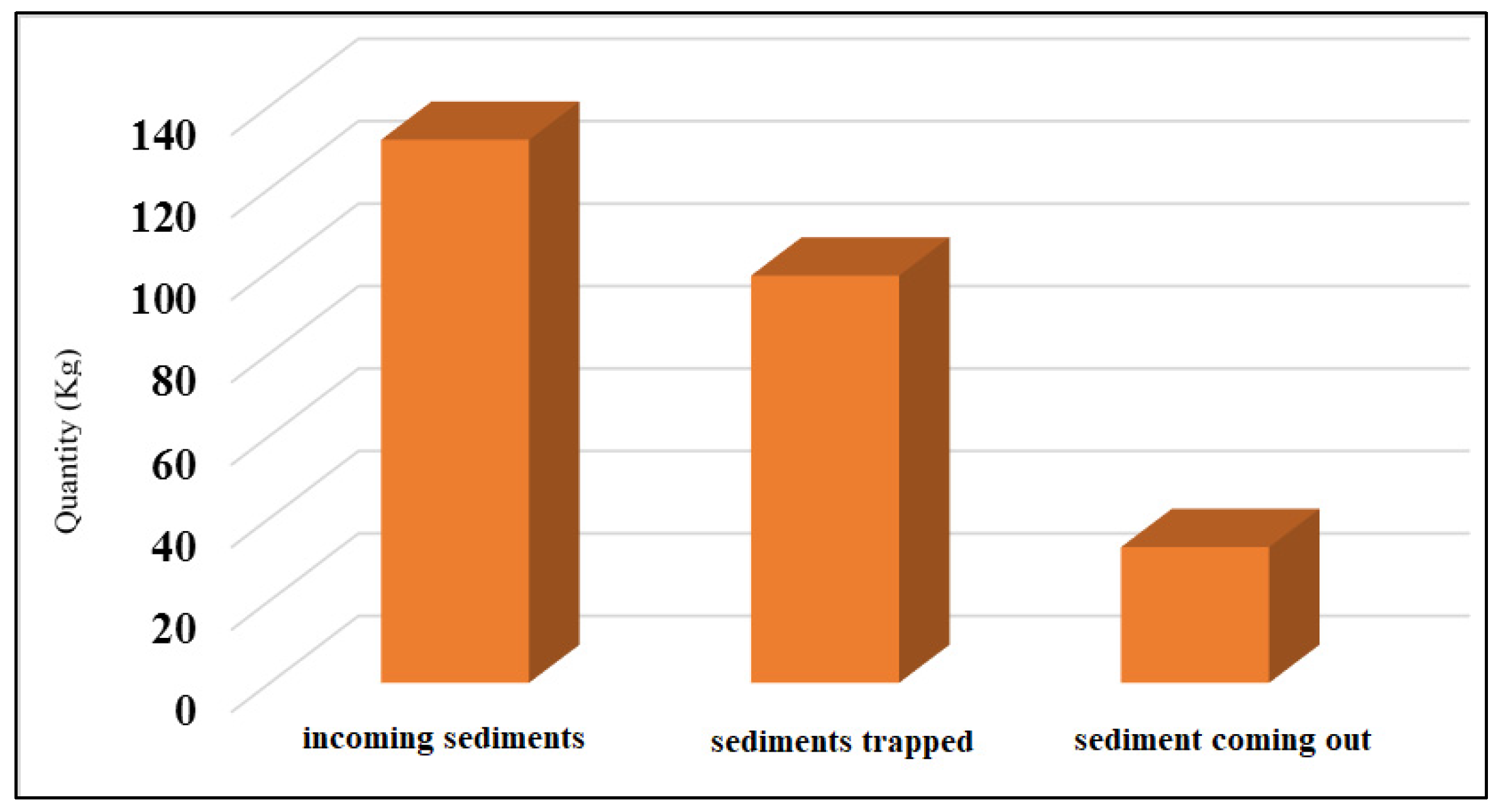

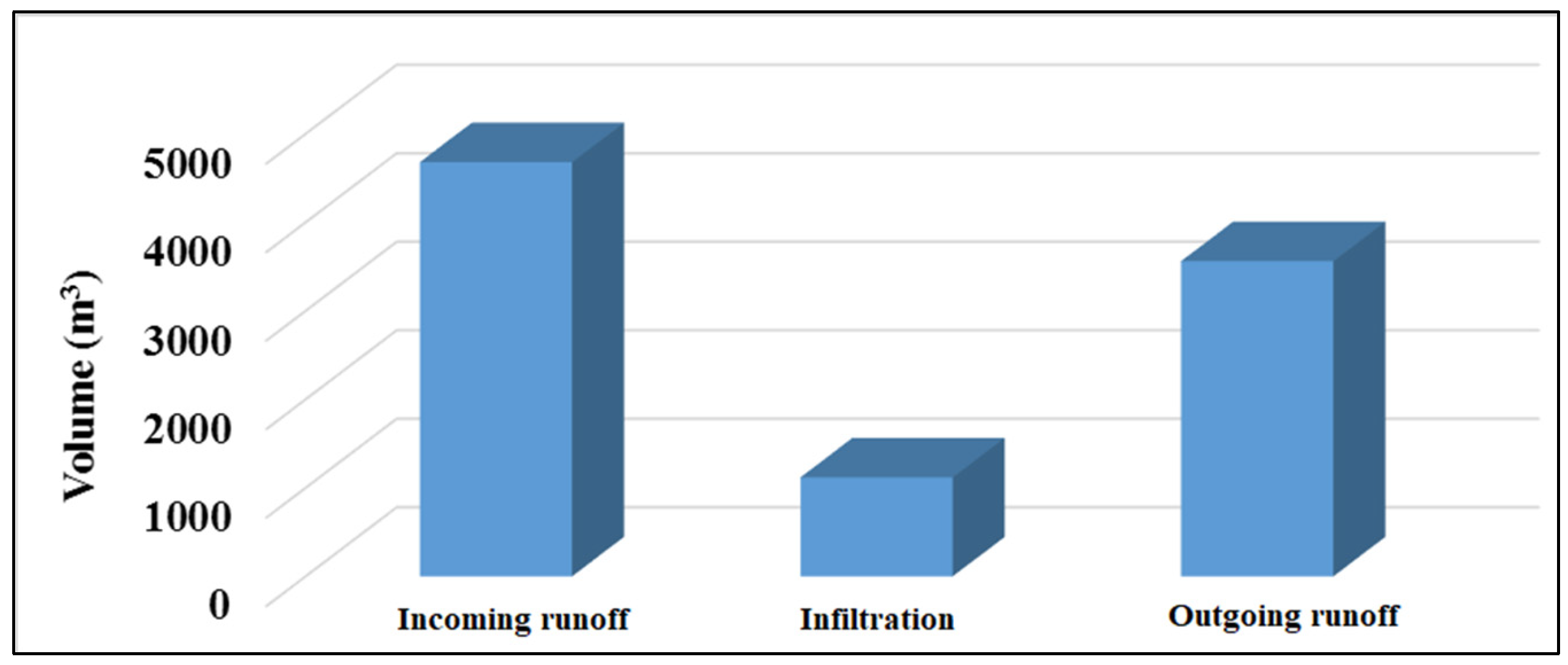

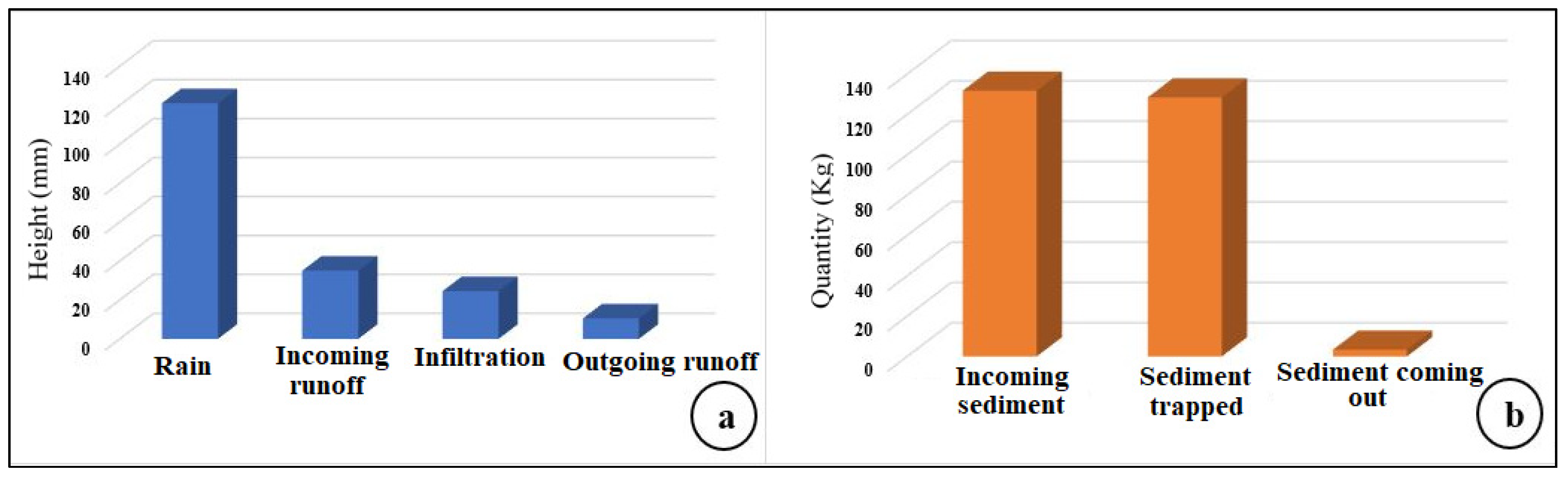

3.4. Runoff and Sediment Entering the Grassy Strip Trapping

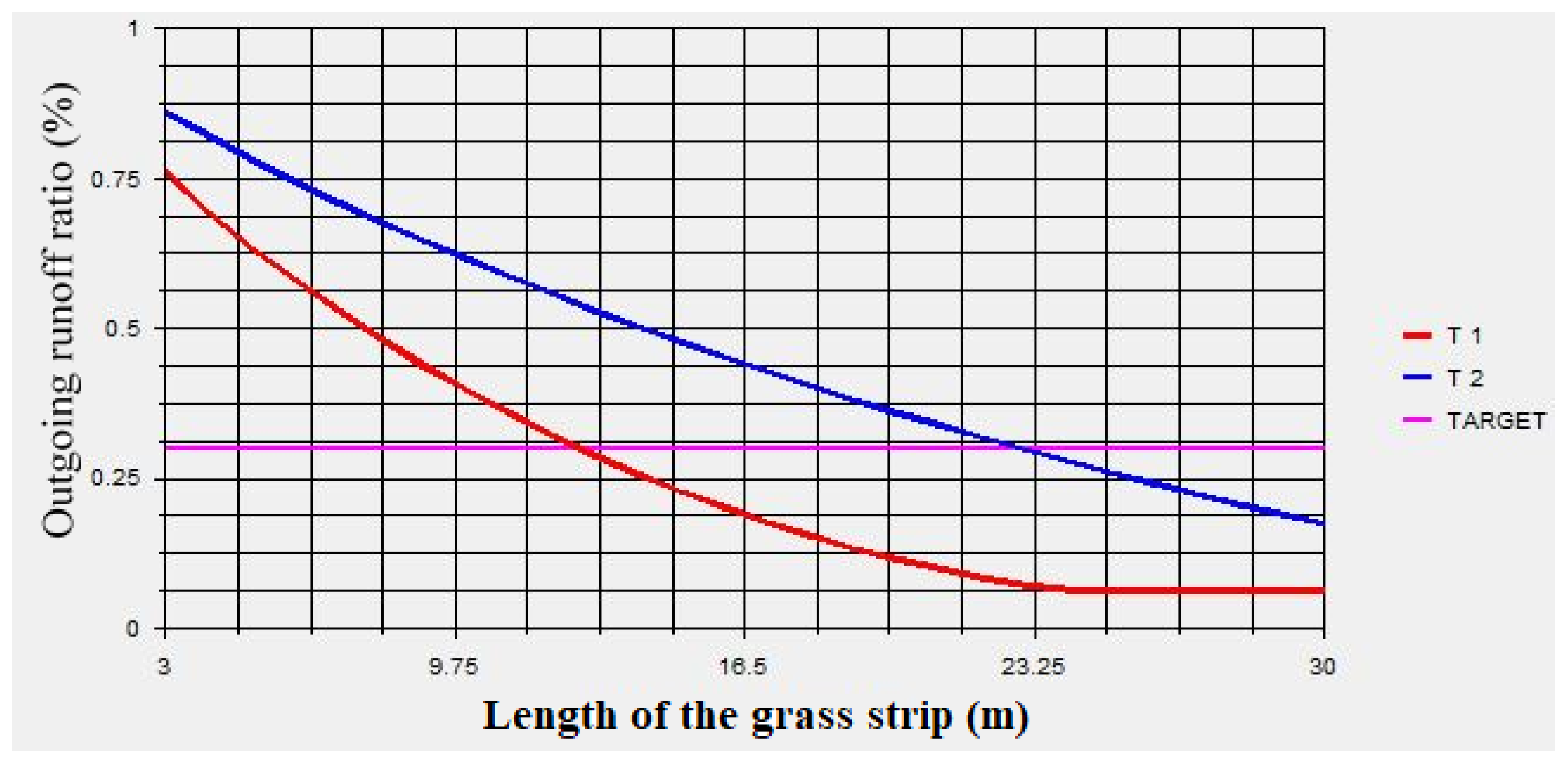

3.5. Optimal Dimensions of the Grass Strip under Different Scenarios

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koukougnon, W.G. Milieu urbain et accès à l’eau potable: Cas de Daloa (Centre-Ouest de la Côte d’Ivoire). Thèse Unique de Doctorat, Université Félix Houphouet Boigny Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire, 2012; 323p. [Google Scholar]

- Komelan, Y. Eutrophisation des retenues d’eau en Côte d’Ivoire et gestion intégrée de leur bassin versant: cas de la Lobo à Daloa. Mémoire de master, École d’Ingénieurs de l’Équipement Rural de Ouagadougou, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 1999; 56p. [Google Scholar]

- Floret, C. (IRD, Dakar, Sénégal); Hien, V. (INERA, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso); Pontanier, R. Le projet « La jachère en Afrique tropicale ». Personal communication, 1993.

- Koua, T.J.-J.; Dhanesh, Y.; Jeong, J.; Srinivasan, R.; Anoh, K.A. Implementation of the Semi-Distributed SWAT (Soil and Water Assessment Tool) Model Capacity in the Lobo Watershed at Nibéhibé (Center-West of Côte D’Ivoire). J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 2021, 9, 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Maïga, A.; Denyigba, K.; Allorent, J. Eutrophisation des Petites Retenues d’eau en Afrique de l’Ouest: Causes et Conséquences: Cas de la Retenue D’eau de la Lobo en Côte d’Ivoire. Sud Sci. Technol. 2001, 7, 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lecomte, V. Transfert de produits phytosanitaires par le ruissellement et l’érosion de la parcelle au bassin versant. Thèse de doctorat, École Nationale du Génie Rural des Eaux et des Forêts de Montpellier, Montpellier, France, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, G.V.; Brussaard, C.P.; Nejstgaard, J.C.; Van Leeuwe, M.A.; Lancelot, C.; Medlin, L.K. Current understanding of Phaeocystis ecology and biogeochemistry, and perspectives for future research. Biogeochemistry 2007, 83, 311–330. [Google Scholar]

- Koua, T.J.-J.; Jeong, J.; Alemayehu, T.A.; Dhanesh, Y.; Srinivasan, R. Spatial Distribution of Nutrient Loads Based on Mineral Fertilizers Applied to Crops: Case Study of the Lobo Basin in Côte d’Ivoire (West Africa). Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soro, M.-P.; N’goran, K.M.; Ouattara, A.A.; Yao, K.M.; Kouassi, N.L.; Diaco, T. Nitrogen and phosphorus spatio-temporal distribution and fluxes intensifying eutrophication in three tropical rivers of Côte d’Ivoire (West Africa). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 186, 114391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N’goran, K.M.; Soro, M.-P.; Kouassi, N.L.B.; Trokourey, A.; Yao, K.M. Distribution, Speciation and Bioavailability of Nutrients in M’Badon Bay of Ebrie Lagoon, West Africa (Côte d’Ivoire). Chem. Afr. 2023, 6, 1619–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koua, T. Apport de la Modélisation Hydrologique et des Systèmes d’Information Géographique (SIG) dans L’étude du Transfert Des Polluants et des Impacts Climatiques sur les Ressources en eau: Cas du bassin Versant du lac de Buyo (Sud-ouest de la Côte d’Ivoire). Ph.D. Thesis, Felix Houphouet Boigny University of Cocody, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, 11 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, A.B. Evaluation des potentialités en eau du bassin versant de la Lobo en vue d’une gestion rationnelle au Centre-Ouest de la Côte d’Ivoire. Thèse de Doctorat, Université Nangui Abrogoua, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Koffi, B.; Kouassi, K.L.; Sanchez, M.; Kouadio, Z.A.; Kouassi, K.H.; Yao, A.B. Estimation de la sédimentation dans la retenue d’eau de la rivière Lobo à l’aide de la théorie des bassins de décantation. In Proceedings of the XVIèmes Journées Nationales Génie Côtier – Génie Civil, Daloa, Côte d’Ivoire, 8–10 Décembre 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brou, T.; Akindès, F.; Bigot, S. La variabilité climatique en Côte d’Ivoire: entre perceptions sociales et réponses agricoles. Cahiers Agricultures 2005, 14, 533–540. [Google Scholar]

- Delor, C.; Siméon, Y.; Vidal, M.; Zeade, Z.; Koné, Y.; Adou, M.; Dibouahi, M.; Irié, D.B.; N’da, B.D.; et al. Carte géologique de la Côte d’Ivoire à 1/200 000, feuille Nassian. Mémoire n°9 de la Direction des Mines et de la Géologie, Côte d’Ivoire, 1995.

- Yao, A.B.; Bi Tié, A.G.; Kane, A.; Mangoua, J.O.; Kouamé, A.K. Cartographie du potentiel en eau souterraine du bassin versant de la Lobo (Centre-Ouest, Côted’Ivoire): approche par analyse multicritère. Hydrological Sciences Journal 2016, 61, 856–867. [Google Scholar]

- Jean Olivier, K.K.; Brou, D.; Jules, M.O.M.; Georges, E.S.; Frédéric, P.; Didier, G. Estimation of Groundwater Recharge in the Lobo Catchment (Central-Western Region of Côte d’Ivoire). Hydrology 2022, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachtergaele, F.; Velthuizen, H.V.; Verest, L. Harmonized world soil database version1.1. 2009. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/aq361e/aq361e.pdf.

- Muñoz-Carpena, R.; Parsons, J.E. VFSMOD-W Vegetative Filter Strips Modelling System. MODEL DOCUMENTATION & USER’S MANUAL version 6.x. 2020; 194p. Available online: https://abe.ufl.edu/faculty/carpena/files/pdf/software/vfsmod/VFSMOD_UsersManual_v6.pdf.

- Lighthill, M.J.; Whitham, C.B. On kinematic waves: flood movement in long rivers. Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. A 1955, 22, 281–316. [Google Scholar]

- Barfield, B.J.; Tollner, E.W.; Hayes, J.C. The use of grass filters for sediment control in strip mining drainage. Vol. I: Theoretical studies on artificial media. Pub. no. 35-RRR2-78; Institute for Mining and Minerals Research, University of Kentucky: Lexington, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Barfield, B.J.; Tollner, E.W.; Hayes, J.C. Filtration of sediment by simulated vegetation I. Steady-state flow with homogeneous sediment. Transactions of ASAE 1979, 22, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.C.; Barfield, B.J.; Barnhisel, R.I. Filtration of sediment by simulated vegetation II. Unsteady flow with non-homogeneous sediment. Transactions of ASAE 1979, 22, 1063–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.C.; Barfield, B.J.; Barnhisel, R.I. Performance of grass filters under Jackson, S.; Hendley, P.; Jones, R.; Poletika, N.; Russell, M. Comparison of regulatory method estimated drinking water exposure concentrations with monitoring results from surface drinking water supplies. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 8840–8847. Laboratory and field conditions. Transactions of ASAE 1984, 27, 1321–1331. [Google Scholar]

- Tollner, E.W.; Barfield, B.J.; Haan, C.T.; Kao, T.Y. Suspended sediment filtration capacity of simulated vegetation. Transactions of ASAE 1976, 19, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollner, E.W.; Barfield, B.J.; Vachirakornwatana, C.; Haan, C.T. Sediment deposition patterns in simulated grass filters. Transactions of ASAE 1977, 20, 940–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.N.; Barfield, B.J.; Moore, I.D. A Hydrology and Sedimentology Watershed Model, Part I: Modeling Techniques; Technical Report; Department of Agricultural Engineering. University of Kentucky: Lexington, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Sur, R.; Muñoz-Carpena, R.; Reichenberger, S.; Hammel, K.; Meyer, H.; Kehrein, N. Implementation of shallow water table effects on pesticide runoff mitigation efficiency by vegetative filter strips within SWAN-VFSMOD. EGU General Assembly 2021, 2021; 19–30 Apr, EGU21-7829. [CrossRef]

- Minwoo, S.; Jisun, B.; Hyun-Dong, Y.; Tae-Hwa, J. A study on trapping efficiency of the non-point source pollution in Cheongmi Stream using VFSMOD-W. The Journal of Korea Contents Association 2016, 16, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Carpena, R.; Reichenberger, S.; Sur, R.; Hammel, K. Fate of pesticide residues in vegetative filter strips in long-term exposure assessments: VFSMOD development and analysis. EGU General Assembly 2021, 19–30 Apr 2021. 2021; EGU21-1735. [CrossRef]

- Catalogne, C.; Lauvernet, C.; Carluer, N. Guide d’utilisation de l’outil BUVARD pour le dimensionnement des bandes tampons végétalisées destinées à limiter les transferts de pesticides par ruissellement; Rapport de recherche IRSTEA: France, 2018; 66p, Available online: https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-02607260/document.

- USDA-SC. Design hydrographs. In National Engineering Handbook Hydrology, 2nd ed.; Vincent, M., William, O., Robert, R., Eds.; Departement of Agriculture: Whasington, D.C, USA, 1972; Available online: https://www.hydrocad.net/neh/630ch21.pdf.

- Carluer, N.; Fontaine, A.; Lauvernet, C.; Muñoz-Carpena, R. Guide de dimensionnement des zones tampons enherbées ou boisées pour réduire la contamination des cours d’eau par les produits phytosanitaires; Rapport de recherche IRSTEA: France, 2020; 72p, Available online: https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-02595578v1/file/pub00032826.pdf.

- Chow, V.T.; Maidment, D.R.; Mays, L.W. Applied hydrology, International Edition; Mc-Graw-Hill Book Company: USA, 1988; pp. 153–155. Available online: https://wecivilengineers.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/applied-hydrology-ven-te-chow.pdf.

- Williams, J.R. Sediment-Yield Prediction with Universal Equation Using Runoff Energy Factor. In Proceedings of the Sediment-Yield Workshop, USDA Sedimentation Laboratory, Oxford, Mississippi, 28-30 November 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Kouassi, A.M.; Nassa, R.A.-K.; Yao, K.B.; Kouamé, K.F.; Biémi, J. Modélisation statistique des pluies maximales annuelles dans le district d’Abidjan (Sud de la Côte d’Ivoire). Revue des Sciences de l’Eau 2018, 31, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosskey, M.G.; Helmers, M.J.; Eisenhauer, D.E. A design aid for sizing filter strips using buffer area ratio. Journal of soil and water conservation. 2011, 66, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breune, I.; Audet, M.A.; Parent, G. Le ray-grass intercalaire: Essai de variétés, Essai de semis à différents stades du maïs. Rapport final club agroenvironnemental de l’Estrie, Québec (Canada). 2015; 60p. Available online: https://www.agrireseau.net/documents/Document_90361.pdf.

- Kieta, K.A.; Owens, P.N.; Lobb, D.A.; Vanrobaeys, J.A.; Flaten, D.N. Phosphorus dynamics in vegetated buffer strips in cold climates: a review. Environ. Rev. 2018, 26, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hénault-Ethier, L.; Gomes, M.P.; Lucotte, M.; Smedbol, É.; Maccario, S.; Lepage, L.; Juneau, P.; Labrecque, M. High yields of riparian buffer strips planted with Salix miyabena ‘SX64’ along field crops in Québec, Canada. Biomass and Bioenergy. 2017, 105, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, L.; Hasselquista, E.M.; Laudona, H. Towards ecologically functional riparian zones: A meta-analysis to develop guidelines for protecting ecosystem functions and biodiversity in agricultural landscapes. Journal of Environmental Management. 2019, 249, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, M.; Dahlgren, R.A.; Eitzel, M. A Review of Vegetated Buffers and a Meta-analysis of Their Mitigation Efficacy in Reducing Nonpoint Source Pollution. J. Environ. Qual. 2010, 39, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remaury, A. Effet de la densité de plantation de peupliers à croissance rapide sur l’érosion des sols recouvrant des pentes de stériles miniers en région boréale. (Mémoire de maîtrise), Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue, 2017. Available online: https://depositum.uqat.ca/id/eprint/713.

- CORPEN. Les fonctions environnementales des zones tampons – Les bases scientifiques et techniques des fonctions de protection des eaux. 2007, Première édition, Paris, 176p. Available online: https://professionnels.ofb.fr/sites/default/files/pdf/Zones-tampons/CORPEN%20.

- Borin, M.; Vianello, M.; Morari, F.; Zanin, G. Effectiveness of buffer strips in removing pollutants in runoff from a cultivated field in North East Italy. Agr Ecosyst Environ. 2005, 105, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, T.J.; Dosskey, M.G.; Hoagland, K.D. Filter Strip Performance and Processes for Different Vegetation, Widths and Contaminants. Journal of Environmental Quality 1999, 28, 1479–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouisat, A.; Douaik, A.; Al Faiz, C.; Harrouni, C.; Derradji, A.; Benaoda, N.-E. Suivi De La Cinétique Du Développement Racinaire Des Plantes Destinées A La Stabilisation Des Talus Marneux De L’axe Autoroutier Fès-Taza (Nord Du Maroc). European Scientific Journal. 2020, 16, 287–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Event | T1 | T2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potential optimal dimensions | Width (m) | 12.70 | 22.95 |

| Length (m) | 300 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).