1. Introduction

Endotracheal intubation (ETI) is the insertion of a flexible plastic tube into the trachea. ETI is an essential emergency treatment to secure an airway in critically severe patients with loss of consciousness and respiratory failure, but it has been reported that can also cause severe hypoxia (26%), hemodynamic collapse (25%), and cardiac arrest (2%) [

1,

2]. In emergency situations where time for patient pretreatment and information about the patient are insufficient, complications occurring after emergency ETI are bound to increase [

3]. An investigation of emergency ETI involving 3,423 cases over 7 years treated outside the operating room revealed difficult airways in 10.3% of cases, with 4.2% composite complications among 2,294 senior residents involving aspiration (3.0%), esophageal intubation (1.1%), dental injury (0.2%), and pneumothorax (0.04%) and observed [

4].

Medical staff performed ETI directly using a Macintosh laryngoscope. However, to achieve a success rate of over 90%, approximately 47 to 56 times more experience is required, and even if you have a lot of experience, it cannot be easy to succeed in ETI in difficult airway situations [

5]. Among all patients requiring ETI, the proportion of difficult intubations is said to range from approximately 6% to 30%, although there is wide variation depending on the literature [

6,

7].

The video laryngoscope (VL) was first introduced in 2001, representing a significant advance in tracheal intubation comparable to the invention of the Macintosh laryngoscope nearly 80 years ago [

8]. VL has recently developed airway management by helping to overcome the difficulties in achieving adequate glottic visualization through direct laryngoscopy. The VL includes a laryngoscope with a high-quality digital camera mounted a few centimeters from the tip of the blade. This involves transferring images from this camera to a screen, providing an anterior view of the glottis and a wider viewing angle, thereby improving laryngeal visibility [

9,

10]. The use of this method is associated with improved glottic visibility, reduced airway trauma, and faster first intubation, especially for novice laryngoscopists, offering a safer risk profile compared to direct laryngoscopy [

11]. Therefore, video laryngoscopy is increasingly recognized as an essential tool during intubation [

12]. However, the learning curve involved in using a video laryngoscope correctly and developing the skills to maximize the likelihood of successful primary intubation still requires a learning curve that must be adjusted during training.

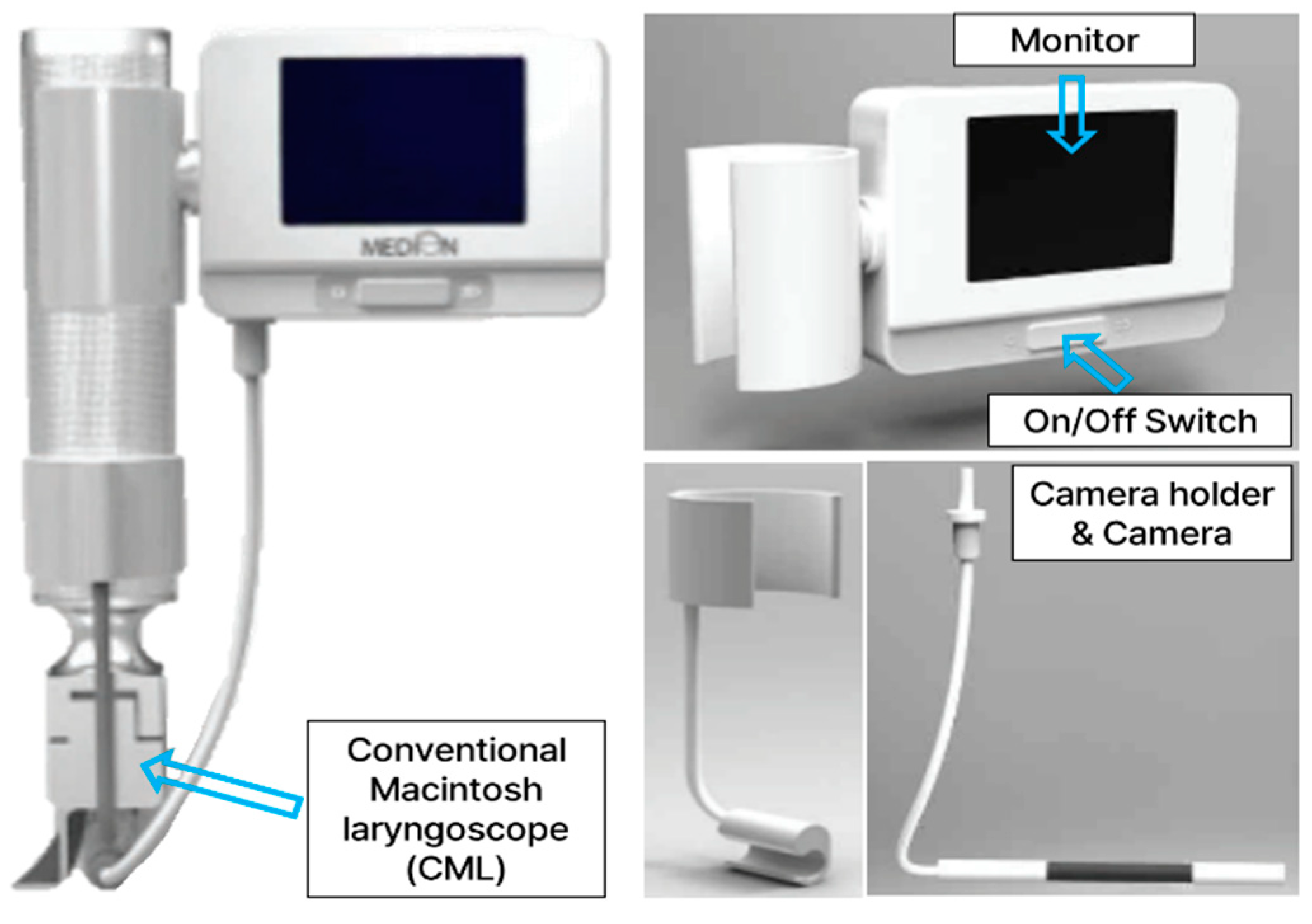

To minimize these drawbacks, we devised an attachable video laryngoscope (AVL) by the simple attachment of a camera and monitor to a conventional Macintosh laryngoscope (CML). Because most medical staff can adopt the feeling similarly of using CML, the product used in this study does not require specialized training or skills (

Figure 1).

The purpose of this study was to assess the usefulness of the AVL in difficult airways. We hypothesized that this novel device would be more successful and easier to use than other VL for physicians without VL experience but with CML experience.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Scenario Simulation

The simulation was performed as a comparative evaluation study of various VLs using a manikin model for ETI (Deluxe Difficult Airway Trainer®; Laerdal, Stavanger, Norway). The manikin was placed on a hospital bed with a general specification. The simulation scenarios included a normal airway and tongue edema.

2.2. Recruitment of Participants

The study participants were recruited from Wonju Severance Christian Hospital. Among the physicians who worked in the university hospital, 20 with no VL experience were recruited. Of these, 10 physicians who had clinical experiences in emergent using tracheal intubation (skilled group), and another 10 physicians who were affiliated with other departments, had few clinical experiences using tracheal intubation (unskilled group). This study was also carried out with approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Yonsei University Wonju Severance Christian Hospital (IRB approval number: YWMR-13-02-024).

2.3. Equipment

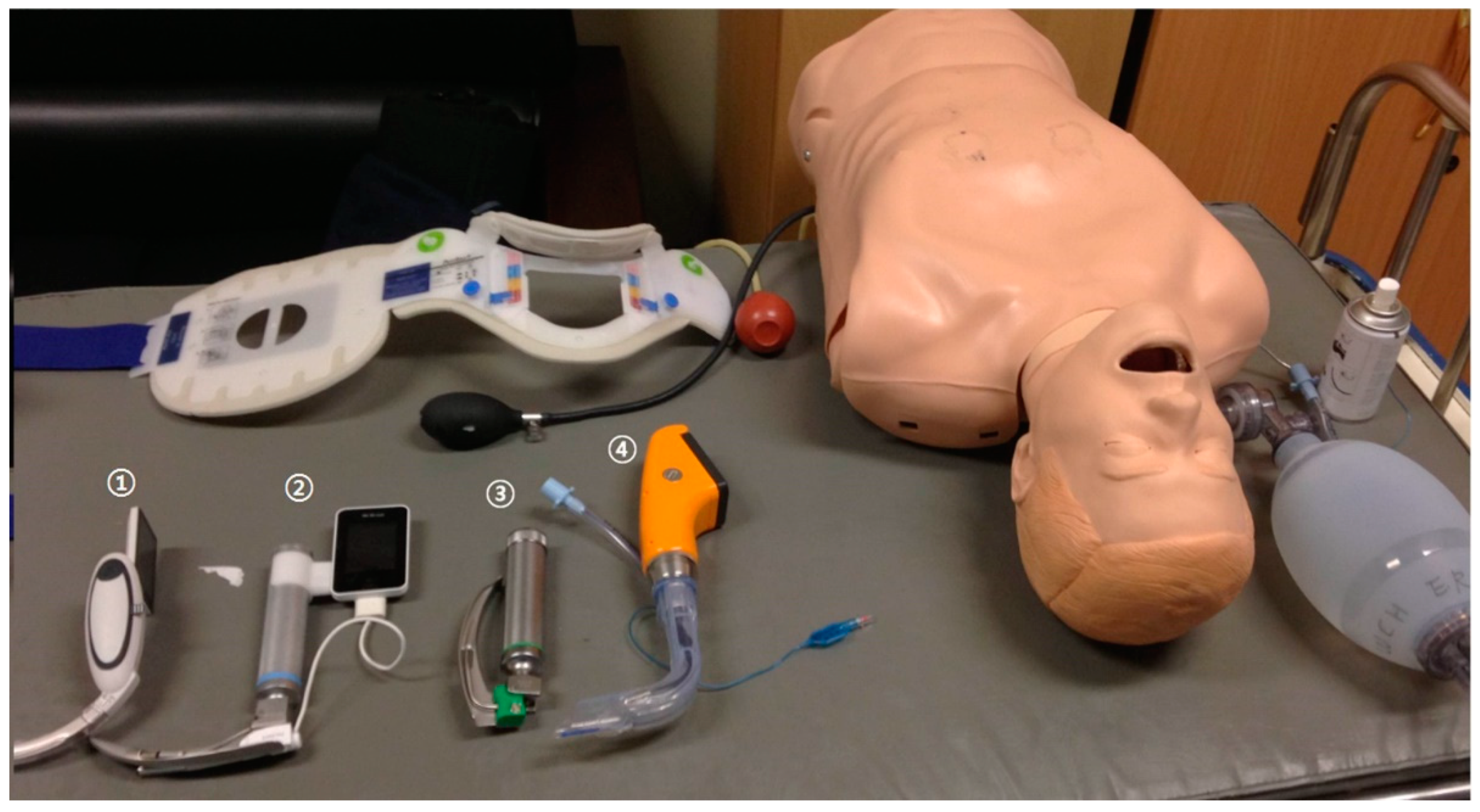

All participants were briefed on the use of each device for 3 minutes prior to use. There was no rehearsal. The sequence of use of the devices was decided randomly by picking labeled pieces of paper whenever the scenario changed. The intent was to prevent learning effects, regency effects, and primacy effects. For tracheal intubation, a 7.5-mm diameter tube was used in all circumstances. The tube cuff was blocked using a 10 mL syringe. A resuscitator bag (Ambu, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used for ventilation. The laryngoscopes that were used are shown in

Figure 2: ① McGrath MAC® (Aircraft Medical Limited, Edinburgh, Scotland), ② AV-scope® AVL (Caretek Inc., Wonju, Korea), ③ Blades 3 CML (Welch Allyn Inc., NY, USA), and ④ Pentax Airwayscope® (Pentax Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

2.4. Data Collection

When the respiration was confirmed by a positive pressure ventilation indicator attached to the manikin, tracheal intubation was considered successful. When the tube was inserted into the esophagus and caused stomach expansion, or when the intubation time exceeded 30 seconds, tracheal intubation was considered to have failed. The criterion of 30 seconds for tracheal intubation was set by the standards defined in the Advanced Cardiac Life Support [

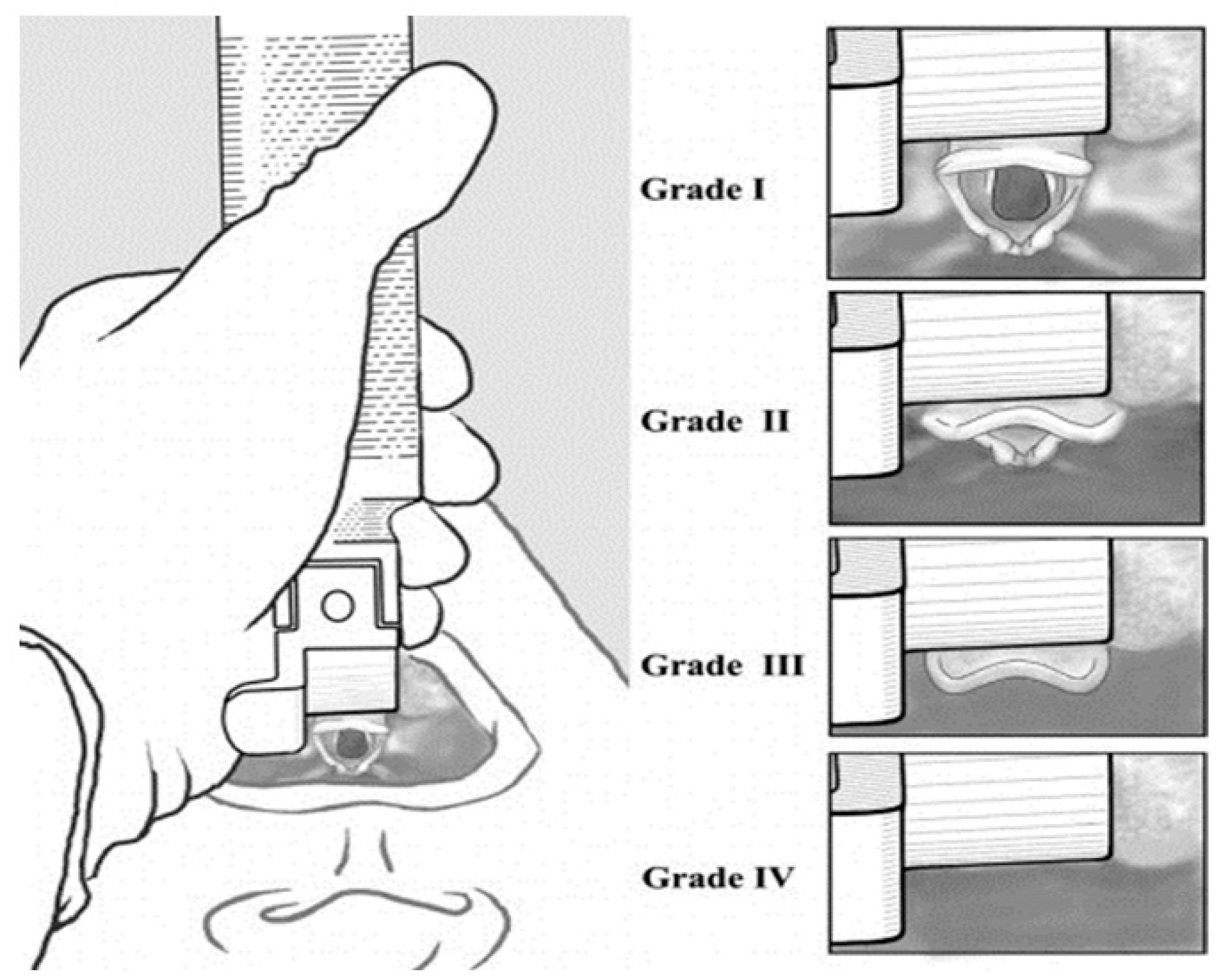

13]. The glottic view assessment was decided by the physician intubating the trachea with a laryngoscope, determining the grade using the Cormack and Lehane classification (

Figure 3), and then inserting the tube [

14]. The degree of difficulty of intubation according to the participants was ranked using a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) that ranged from 0 (very easy) to 10 (very difficult) after study completion.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The data for the success of the tracheal intubation attempts were analyzed using the χ2 test. Data for the quality of the glottic view were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Data for intubation time and the degree of difficulty of intubation were tested for normal distribution using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. If data had a normal distribution, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted. If data were not normally distributed, the Kruskal-Wallis test with Bonferroni correction was used. The α-error level for all analyses was set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

With two scenarios and four devices, 160 study cases were collected from the 20 participants.

3.1. Comparative Assessment by Device in the Skilled Group

Table 1 presented the comparative assessment of success rate, intubation time, visual field, and degree of difficulty of use by the device in the skilled group.

In the normal airway scenario, there were no significant differences in the success rates of tracheal intubation and intubation times with any of the devices (p=0.38 and p=0.68, respectively). The glottic view was classified as grade I-II, which indicated that it was possible to perform tracheal intubation with all devices.

In the tongue edema scenario, the Pentax AWS® (AWS) had the highest success rate (100%) followed by the AVL (60%), McGrath MAC® (MAC) (60%), and CML (20%) (p = 0.001). The intubation time in CML was the shortest (9.3 seconds). Also, the intubation time in AVL (19.2 [14.4-23.4] seconds) was longer than that of AWS (10.2 [9.8-11.7] seconds) but was similar to that of MAC (20.4 [16.6-23.9]) (p=0.007).

Considering the degree of difficulty of use, the AWS was significantly the easiest to use (1.5 [0.4-2.6]). Although the difficulty of use of AVL (2.8 [2.1-4.3]) was more difficult than that of AWS, it was significantly easier to use compared to CML (vs. 7.8 [5.5-8.1]) and MAC (vs. 5.3 [3.9-5.8]) (p<0.001).

3.2. Comparative Assessment by Device in the Unskilled Group

Table 2 presented the comparative assessment of success rate, intubation time, visual field, and degree of difficulty of use by the device in the unskilled group.

In the normal airway scenario, there were no significant differences in the success rates and times of tracheal intubation with any of the devices (p=0.19 and p=0.90, respectively). The glottic view was classified as grade I-II, which indicated that it was possible to perform tracheal intubation with all devices.

In the tongue edema scenario, the AWS had the highest success rate (80%) followed by the MAC (60%), AVL (50%), and CML (10%), but there was no significant (p = 0.12). The intubation time in AWS was the shortest (11.5 [9.1-16.7] seconds). Also, the intubation time in AVL (23.3 [18.8-27.3] seconds) was similar to that of MAC (20.0 [16.8-23.4]) and CML (26.7 seconds) (p=0.13).

Considering the degree of difficulty of use, the AWS was significantly the easiest to use (0.7 [0.1-1.8]). Although the difficulty of use of AVL (3.3 [3.1-4.9]) was more difficult than that of AWS, it was significantly easier to use compared to CML (vs. 8.8 [6.9-9.1]) (p<0.001).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the usefulness of AVL in the simulated tracheal intubation scenario using a manikin. To manage patient safety, and avoid ethical friction, it was thought that it would be most appropriate to use a manikin in this study. Additionally, the use of a manikin allowed more precise control of the study conditions [

15,

16]. Comparisons of VL have used parameters including success rate, time of tracheal intubation, scale of the secured visual field (based on the Cormack and Lehane classification), and VAS-assessed degree of difficulty of use [

15,

17,

18,

19].

Direct Laryngoscope has traditionally been the go-to method for airway management in emergency departments, but VL has seen a consistent rise in use over the past decade. As recently as 2012, physicians were using direct laryngoscopes rather than VL in emergency rooms [

20]. However, VL has emerged as a valuable tool in airway management, offering several advantages over traditional direct laryngoscopy. A study by Prekker et al. highlights its effectiveness in improving glottic visualization, particularly in patients with difficult airways or anatomical challenges [

21]. The enhanced visualization provided by video laryngoscopes can lead to higher first-pass success rates and reduced intubation-related complications [

22]. Additionally, video laryngoscopy allows for real-time feedback and teaching opportunities, aiding in the training of medical professionals [

23]. However, despite these benefits, video laryngoscopy also presents some drawbacks. Cost implications, device availability, and the learning curve associated with its use are notable concerns [

22]. Furthermore, the reliance on electronic equipment introduces the risk of technical failure, potentially hindering rapid airway management in critical situations [

24]. Overall, while video laryngoscopy offers significant advantages in airway management, clinicians must carefully weigh these benefits against the associated challenges to determine its optimal utilization in clinical practice.

In the normal airway scenario, the choice of the device was not influential to the outcome. In the normal airway setting, prior findings have been equivocal, with VL being found use and not useful in college students who were unskilled at tracheal intubation [

17,

18]. Interestingly, in the unskilled group who were not familiar with the CML, the degree of difficulty in using the AVL was not appreciably different compared with the McGrath MAC®, whereas the skilled group who were familiar with the CML did display an appreciable difference in comparison with the McGrath MAC®. These outcomes were expected because the AVL has the same shape and is used in the same manner as the CML.

Results have been reported from comparative studies on various video laryngoscopes. In the present study, the Pentax AWS® was more functional than the other two VLs concerning outcomes and the degree of difficulty of use. The Pentax AWS® was typically the easiest method concerning outcomes and the degree of difficulty of use [

17,

18]. Similarly, it was reported to emphasize the superior glottic visualization provided by the Pentax AWS compared to direct laryngoscopy, particularly in patients with limited neck mobility or difficult airway anatomy [

25]. These benefits should be considered in future AVL refinements. Additionally, its ergonomic handle design and intuitive user interface contribute to user satisfaction and ease of use in various clinical settings [

26]. The Pentax AWS® differs from the conventional video laryngoscopes in that it assists with inserting the tracheal tube using a tube guide and a monitor to indicate the direction of tube progression [

27]. Overall, the Pentax AWS stands out as a valuable tool in airway management, offering improved visualization, efficiency, and user-friendly features that benefit both patients and healthcare providers.

The VL represents the latest innovation in the area of airway management, enabling video-guided indirect laryngoscopy, and it is particularly useful for difficult airways. However, experience using the equipment and frequent use is required to ensure successful tracheal intubation [

28,

29]. Thus, the ideal device would be a tool that is designed to be used as a standard laryngoscope but that provides improved views of the larynx in an unanticipated difficult airway [

30]. However, in the results obtained from this study, the AVL did not exhibit usefulness compared to the other two VLs.

This study used a manikin simulation, which has some limitations. In the actual setting, fogging caused by breathing, bleeding due to trauma, vomiting, and secretions can all adversely affect the VL camera lens, but these real-world factors may not be influential in comparisons of the different VLs because the conditions were common through all comparisons. Nevertheless, real-world conditions should be considered in future studies, particularly when comparing an AVL with a general laryngoscope that has no camera. A second limitation concerned comparing the four devices in only one difficult scenario. There are multiple types of difficult airway including tongue edema, facial trauma, cervical immobility, jaw trismus, and pharyngeal obstruction. Only tongue edema was studied here because it is considered the most difficult airway obstacle [

31,

32]. This minimized learning effect bias. Still, information on device performance in all airway scenarios would be ideal. As a third limitation, we did not assess injury complications. Oral and dental injuries are also important in terms of the clinical view, but these complications are not important compared with the intubation success rate or time from the perspective of risk versus benefit in emergency airway management. That is why they were not considered in this study.

5. Conclusions

In the skilled group, the AVL had the shortest tracheal intubation time compared to other devices in normal airway scenarios. Additionally, in the tongue edema scenario, the success rate of tracheal intubation was higher than that of CML, but the tracheal intubation time took longer. Likewise, in the unskilled group, the AVL showed a similar success rate and time of tracheal intubation to the MAC. The AVL may be an alternative VL choice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.H.L.; methodology, W.J.L.; formal analysis, H.Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, W.J.L..; writing—review and editing, K.H.L.; project administration, H.Y.L. and S.J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Korea Medical Device Development Fund grant funded by the Korea government (the Ministry of Science and ICT, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea, the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety) (Project Number: RS-2020-KD000247). It was also supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (No. HR21C0885).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study was also carried out with approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Yonsei University Wonju Severance Christian Hospital (IRB approval number: YWMR-13-02-024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Griesdale, D.E.; Bosma, T.L.; Kurth, T.; Isac, G.; Chittock, D.R. Complications of endotracheal intubation in the critically ill. Intensive care medicine 2008, 34, 1835–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaber, S.; Amraoui, J.; Lefrant, J.Y.; Arich, C.; Cohendy, R.; Landreau, L.;…; Eledjam, J.J. Clinical practice and risk factors for immediate complications of endotracheal intubation in the intensive care unit: a prospective, multiple-center study. Critical care medicine 2006, 34, 2355–2361. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mort, T.C. Complications of emergency tracheal intubation: hemodynamic alterations-part I. Journal of intensive care medicine 2007, 22, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, L.D.; Mhyre, J.M.; Shanks, A.M.; Tremper, K.K.; Kheterpal, S. 3,423 emergency tracheal intubations at a university hospital: airway outcomes and complications. The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists 2011, 114, 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Nouruzi-Sedeh, P.; Schumann, M.; Groeben, H. Laryngoscopy via Macintosh blade versus GlideScope: success rate and time for endotracheal intubation in untrained medical personnel. The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists 2009, 110, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Griesdale, D.E.; Liu, D.; McKinney, J.; Choi, P.T. Glidescope® video-laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for endotracheal intubation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Canadian journal of anaesthesia 2012, 59, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orebaugh, S.L. Difficult airway management in the emergency department. The Journal of emergency medicine 2002, 22, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pintarič, T.S. Videolaryngoscopy as a primary intubation modality in obstetrics: A narrative review of current evidence. Biomolecules and Biomedicine 2023, 23, 949. [Google Scholar]

- Myatra, S.N.; Patwa, A.; Divatia, J.V. Videolaryngoscopy for all intubations: Is direct laryngoscopy obsolete? Indian J. Anaesth. 2022, 66, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott-Brown, S.; Russell, R. Video laryngoscopes and the obstetric airway. Int. J. Obstet. Anesth. 2015, 24, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulkumaran, N.; Lowe, J.; Ions, R.; Mendoza, M.; Bennett, V.; Dunser, M.W. Video laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for emergency orotracheal intubation outside the operating room: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British journal of anaesthesia 2018, 120, 712–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaouter, C.; Calderon, J.; Hemmerling, T.M. Videolaryngoscopy as a new standard of care. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2015, 114, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummins, R.O. ACLS: Principles and Practice. Dallas, TX: American Heart Association; 2004.

- Cormack, R.S. Cormack–Lehane classification revisited. British journal of anaesthesia 2010, 105, 867–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, J.W.; Lee, S.B.; Do, B.S. Comparison of the Macintosh laryngoscope and the GlideScope (R) video laryngoscope in easy and simulated difficult airway scenarios: a manikin study. Journal of The Korean Society of Emergency Medicine 2009, 20, 604–608. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, B.H.; Liu EH, C.; Lim RT, C.; Liow LM, H.; Goy RW, L. Ease of intubation with the GlideScope or Airway Scope by novice operators in simulated easy and difficult airways–a manikin study. Anaesthesia 2009, 64, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, M.A.; Hassett, P.; Carney, J.; Higgins, B.D.; Harte, B.H.; Laffey, J.G. A comparison of the Glidescope®, Pentax AWS®, and Macintosh laryngoscopes when used by novice personnel: a manikin study. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d'anesthésie 2009, 56, 802–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.K.; Huang, C.C.; Lee, Y.; Chen, T.Y.; Lai, H.Y. Comparison of 3 video laryngoscopes with the Macintosh in a manikin with easy and difficult simulated airways. The American journal of emergency medicine 2013, 31, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, S.; Celenza, A. Comparison of the Pentax AWS videolaryngoscope with the Macintosh laryngoscope in simulated difficult airway intubations by emergency physicians. The American journal of emergency medicine 2011, 29, 863–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.A. , III, Bair, A.E.; Pallin, D.J.; Walls, R.M.; Near III Investigators. Techniques, success, and adverse events of emergency department adult intubations. Annals of emergency medicine 2015, 65, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prekker, M.E.; Driver, B.E.; Trent, S.A.; Resnick-Ault, D.; Seitz, K.P.; Russell, D.W.;...; Semler, M.W. Video versus direct laryngoscopy for tracheal intubation of critically ill adults. New England Journal of Medicine 2023, 389, 418–429. [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.R. Direct and Indirect Laryngoscopy: Equipment and TechniquesDiscussion. Respiratory care 2014, 59, 850–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szarpak, L.; Kurowski, A.; Czyzewski, L.; Rodríguez-Núñez, A. Video rigid flexing laryngoscope (RIFL) vs Miller laryngoscope for tracheal intubation during pediatric resuscitation by paramedics: a simulation study. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2015, 33, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donald, E.; Griesdale, G.; Chau, A.; Isac, G.; Ayas, N.; Foster, D.; Choi, P. Video-laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy in critically ill patients: a pilot randomized trial. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia 2012, 59, 1032. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, M.F.; Dillman, D.; Fu, R.; Brambrink, A.M. Comparative effectiveness of the C-MAC video laryngoscope versus direct laryngoscopy in the setting of the predicted difficult airway. The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists 2012, 116, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonca, C.; Mesbah, A.; Velayudhan, A.; Danha, R. A randomised clinical trial comparing the flexible fibrescope and the Pentax Airway Scope (AWS)® for awake oral tracheal intubation. Anaesthesia 2016, 71, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thong, S.Y.; Lim, Y. Video and optic laryngoscopy assisted tracheal intubation–the new era. Anaesthesia and intensive care 2009, 37, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.J.; Kang, H.G.; Lim, T.H.; Chung, H.S.; Cho, J.; Oh, Y.M.; Kim, Y. M. Endotracheal intubation using a GlideScope video laryngoscope by emergency physicians: a multicentre analysis of 345 attempts in adult patients. Emergency Medicine Journal 2010, 27, 380–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirlich, N.; Piepho, T.; Gervais, H.; Noppens, R.R. Indirekte Laryngoskopie/Videolaryngoskopie. Übersicht über in Deutschland verwendete Instrumente in der Notfall- und Intensivmedizin [Indirect laryngoscopy/video laryngoscopy. A review of devices used in emergency and intensive care medicine in Germany]. Medizinische Klinik, Intensivmedizin und Notfallmedizin 2012, 107, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Chung, S.P.; Park, I.C.; Cho, J.; Lee, H.S.; Park, Y.S. Comparison of the GlideScope video laryngoscope and Macintosh laryngoscope in simulated tracheal intubation scenarios. Emergency Medicine Journal 2008, 25, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narang, A.T.; Oldeg, P.F.; Medzon, R.; Mahmood, A.R.; Spector, J.A.; Robinett, D.A. Comparison of intubation success of video laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy in the difficult airway using high-fidelity simulation. Simulation in Healthcare 2009, 4, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariya, T.; Inagawa, G.; Nakamura, K.; Fujimoto, J.; Aoi, Y.; Morita, S.; Goto, T. Evaluation of the Pentax-AWS® and the Macintosh laryngoscope in difficult intubation: a manikin study. Acta anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 2011, 55, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).