1. Introduction

The accelerating effects of climate change, coupled with a growing demand for sustainable energy management, present an unprecedented challenge for present and future generations [

1]. The impacts of environmental degradation threaten global ecosystems, economies, and the very fabric of society [

2]. It is imperative that we equip today's youth with the knowledge, skills, and tools to not only mitigate climate change but also transition towards a sustainable energy future [

3]. Education stands as a fundamental pillar in creating a generation capable of addressing these complex issues [

4].

The continuous growth of populations, urbanization, and industrialization has significantly escalated energy consumption, exerting pressure on finite fossil fuel resources and exacerbating carbon dioxide emissions, with consequent adverse climatic impacts [

5]. In response, the emphasis has shifted towards renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal, which present cleaner and more sustainable options [

6]. Additionally, enhancing energy efficiency across diverse sectors is critical for minimizing energy waste and mitigating greenhouse gas emissions [

7]. The adoption of energy-efficient technologies, implementation of energy management systems, education and promotion of behavioral changes are vital measures in facilitating sustainable energy consumption practices [

8].

Amidst this climate and energy landscape, Artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative technology with far-reaching implications [

9]. Its capabilities in data processing, pattern recognition, and predictive modeling make it an invaluable tool for addressing the complexities of climate change and energy management [

10]. AI-powered solutions can optimize renewable energy generation, forecast energy demand, enhance grid efficiency, and drive innovation in energy storage [

11]. Moreover, AI can play a crucial role in climate science by analyzing vast datasets to improve climate models, identify environmental risks, and develop adaptation strategies [

12].

Crucially, AI holds immense potential to revolutionize education, especially in the domains of climate and energy [

13]. AI can personalize learning experiences, provide interactive simulations of complex systems, facilitate data-driven insights, and foster student engagement in climate action projects [

14]. To fully realize this potential, a holistic approach to integrating AI into the educational landscape is necessary [

15].

A comprehensive model for AI education focused on climate action must encompass several crucial dimensions [

16]. This includes the organizational structure for curriculum development and teacher training, financial resources for acquiring AI tools and infrastructure, technical capabilities to handle climate data and AI models, pedagogical strategies tailored to AI-enhanced learning, and social considerations to ensure accessibility and address potential biases [

17]. By carefully orchestrating these elements, we can create a robust educational framework that leverages the power of AI to equip future generations with the skills and knowledge to navigate the challenges of climate change and drive the transition to a sustainable energy future [

18].

The objective of this article is to delve into the synergy between artificial intelligence (AI) and education systems in the energy context, elucidating the transformative potential of AI in reshaping how we generate, distribute, and utilize energy resources [

19]. Through the analysis of extensive datasets, AI algorithms facilitate the optimization of energy systems and enable intelligent decision-making processes [

20]. This paper aims to showcase diverse ideas and applications where AI technologies can be harnessed to tackle energy-related challenges, paving the way for enhanced energy efficiency, waste reduction, and the promotion of sustainable practices [

21]. Ultimately, the integration of AI into education systems holds promise for fostering a cleaner and more sustainable energy future [

22].

2. The Evolution of Education Systems in Context of Energy

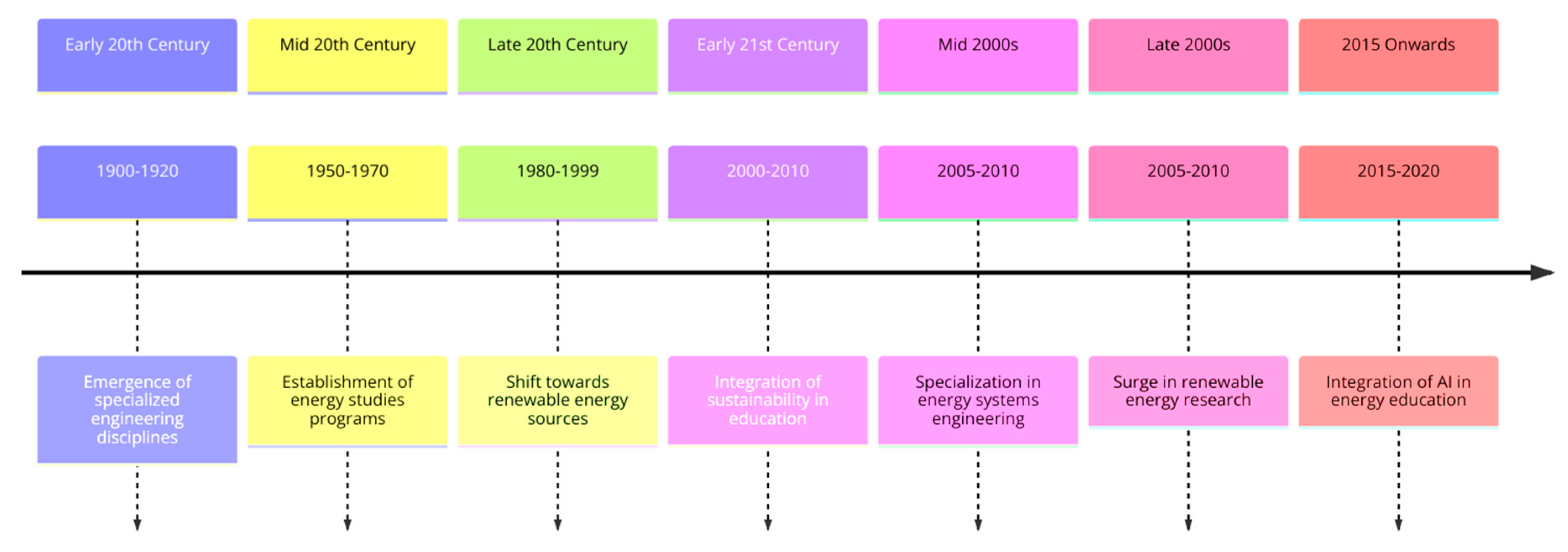

In the early 20th century, higher education institutions witnessed the burgeoning rise of specialized engineering disciplines, marking a pivotal era in the development of energy-related education [

23]. Institutions began offering programs in mechanical, electrical, and chemical engineering, laying the foundational groundwork for the study of energy systems. These programs focused primarily on traditional energy sources such as coal, oil, and natural gas, reflecting the industrialization trends of the time and the pressing need for skilled professionals to drive technological advancements in energy production and utilization [

24].

The mid-20th century heralded the establishment of energy studies programs within universities, spurred by mounting concerns surrounding energy security and environmental degradation. These interdisciplinary programs sought to provide a holistic education on energy-related topics, bridging the gap between engineering, economics, environmental science, and policy studies [

25]. By integrating diverse disciplinary perspectives, energy studies programs aimed to equip students with the knowledge and skills necessary to address complex energy challenges, including resource depletion, pollution, and geopolitical tensions [

26].

In the latter part of the 20th century, a noticeable transition towards renewable energy sources and sustainable energy practices began to take shape, prompting a notable evolution in the approach of higher education towards energy studies [

27]. In response to the pressing need for transitioning towards cleaner and more sustainable energy systems, higher education institutions took significant steps to broaden their energy studies programs. These expansions included incorporating coursework and research focused on renewable energy technologies, energy efficiency measures, and environmental sustainability practices [

28].

In the early 21st century, higher education institutions underwent a significant transformation marked by a deep integration of sustainability principles across various academic disciplines, particularly within the field of energy studies. This shift was driven by a growing acknowledgment of the intricate relationships between energy systems, environmental sustainability, socioeconomic factors, and policy considerations [

29]. In response, universities began to establish interdisciplinary programs and courses aimed at exploring the interconnectedness of energy, environment, economics, and society. These initiatives aimed to foster a comprehensive understanding of the complex challenges and opportunities inherent in contemporary energy systems, thereby equipping students with the skills needed to navigate sustainability issues in energy discourse effectively [

30].

During the mid-2000s, as modern energy systems became increasingly complex, specialized programs in energy systems engineering emerged within the academic sphere [

31]. These educational initiatives were developed to address the growing intricacies of energy infrastructure and management, advocating for a systems-oriented approach to energy planning, design, and governance. Drawing from diverse disciplines such as engineering, systems analysis, and policy development, energy systems engineering programs sought to instill in students a nuanced comprehension of the interconnected nature of energy systems and the imperatives of sustainable energy transition [

32].

Figure 1.

Evolution of Energy Studies in Higher Education. (Source: own elaboration).

Figure 1.

Evolution of Energy Studies in Higher Education. (Source: own elaboration).

The late 2000s witnessed a surge in research and innovation focused on renewable energy technologies, driven by mounting concerns over climate change mitigation and energy security [

33]. Universities played a pivotal role in fostering this era of heightened activity by establishing dedicated research centers and institutes focused on advancing renewable energy technologies [

34]. Through collaborative efforts involving academia, industry, and government stakeholders, these institutions propelled the boundaries of renewable energy research, contributing to the trajectory towards a more sustainable and resilient energy future [

35].

Starting from 2015, the trajectory of energy education within higher education institutions experienced further enhancement through the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) as a transformative technology [

36]. AI algorithms, equipped with sophisticated capabilities in data analytics, machine learning, and optimization, emerged as invaluable tools for enriching the efficacy and comprehensiveness of energy education [

37]. AI-driven platforms facilitated the synthesis and analysis of extensive and disparate datasets related to energy systems, enabling a holistic understanding of energy dynamics and informing evidence-based decision-making processes. By providing predictive analytics capabilities, AI empowered stakeholders to formulate proactive strategies for sustainable energy transition, thereby reshaping the landscape of energy scholarship in the 21st century and beyond [

38].

The latest trends in higher education's approach to energy studies continue to evolve, reflecting both technological advancements and pressing global needs. Key trends include:

Deepening Integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI): AI's role in energy education is expanding beyond data analytics to include the automation of complex energy systems management and the simulation of energy markets and scenarios. These advancements are helping to prepare students for cutting-edge roles in energy policy, management, and technology.

Increased Focus on Climate Change and Resilience: As concerns about climate change intensify, there is a growing emphasis on integrating climate resilience into energy curricula. This includes studying the impacts of climate variability on energy production and distribution, and designing energy systems that can withstand and adapt to climate-related disruptions.

Expansion of Interdisciplinary Studies: Universities are increasingly promoting cross-disciplinary studies that combine energy education with fields such as urban planning, public health, and international relations. This trend underscores the recognition that energy solutions are deeply interconnected with other societal challenges.

Virtual and Augmented Reality Tools: The use of VR and AR in education is on the rise, providing immersive learning experiences that help students understand complex energy systems and infrastructures in a virtual environment. This technology is particularly useful in simulating the effects of energy decisions in a controlled, risk-free setting.

Sustainability and Circular Economy Concepts: There is a notable shift towards incorporating principles of sustainability and the circular economy into energy programs. This reflects a broader move towards sustainability in academia and includes topics like waste-to-energy technologies, lifecycle assessment, and the economic impacts of recycling energy resources.

Global and Local Energy Policy Studies: As energy issues become more global due to the interconnectedness of markets and environmental impacts, educational programs are increasingly focusing on both global energy policy and localized, community-based energy solutions. This dual focus prepares students to think globally while acting locally.

3. AI-Integrated Energy Education Framework(AI-IEEF)

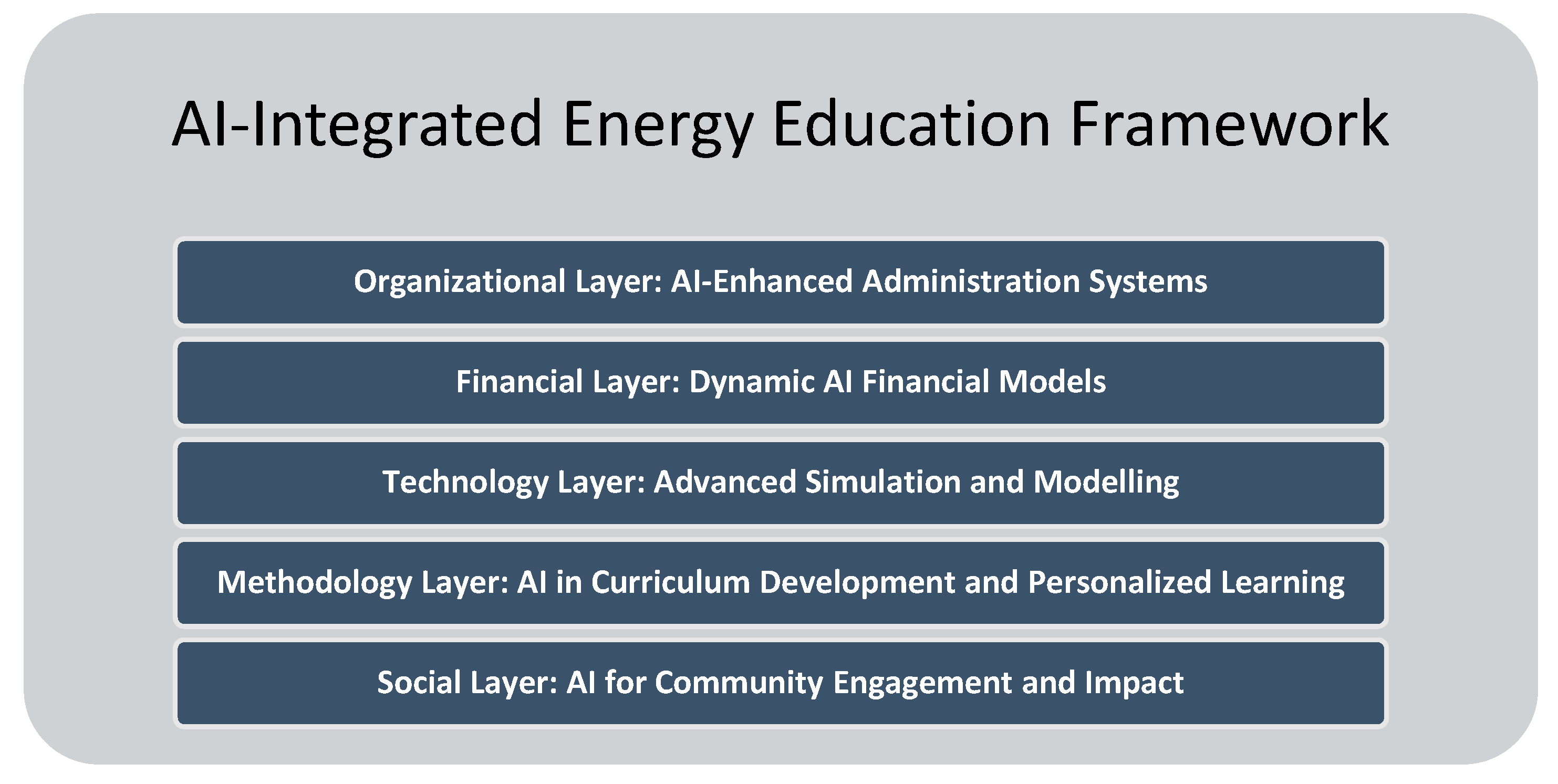

The "AI-Integrated Energy Education Framework" represents a pioneering approach to reshaping higher education in the energy sector. This comprehensive model systematically embeds artificial intelligence across multiple layers of the educational structure, including organizational, financial, technological, methodological, and social aspects. By harnessing the power of AI, institutions are equipped to streamline operations, optimize financial resources, enhance educational technologies, tailor learning experiences, and amplify community impact. This framework is designed to respond dynamically to the evolving landscape of energy challenges and opportunities, preparing students not just to participate in but to drive forward the transition towards sustainable energy systems.

At the heart of this framework lies the commitment to integrating cutting-edge AI technologies to create a responsive and efficient educational environment. AI-driven administrative systems optimize campus energy use and predict infrastructural needs, while AI-enhanced financial models ensure real-time adaptability in funding for critical research and sustainability projects. Advanced simulations and AI-facilitated curriculum development provide students with a deeply personalized and immersive learning experience. Moreover, AI's role extends into the community, enhancing the engagement and effectiveness of outreach programs and providing valuable insights into the social impacts of energy education. This model not only fosters academic excellence and innovation but also nurtures a generation of professionals capable of making informed, impactful decisions in the global energy sector.

The AI-Integrated Energy Education Framework incorporates artificial intelligence across organizational, financial, technological, methodological, and social layers:

Organizational Layer: AI-Enhanced Administration Systems - Develop AI-driven platforms to streamline university operations, focusing on energy management and sustainability. These systems could use predictive analytics to optimize energy consumption across campuses, anticipate maintenance needs for energy systems, and manage resources more efficiently. Additionally, AI can assist in the strategic planning of new programs and partnerships by analyzing trends in energy education and industry demands.

Financial Layer: Dynamic AI Financial Models - Implement AI-based financial tools that enable real-time budgeting and financial planning with a focus on sustainability projects and energy research funding. These models could predict financial needs for energy-focused academic programs and research initiatives, adjusting in real-time based on shifting priorities and available resources. AI could also be used to identify potential funding opportunities and streamline grant application processes for projects related to renewable energy and sustainability.

Technology Layer: Advanced Simulation and Modelling - Integrate cutting-edge AI tools to enhance the learning and research environment by using advanced simulations and models of energy systems. This includes the creation of virtual labs where students can engage with complex energy scenarios using AI to simulate outcomes of various interventions in virtual energy markets, renewable energy integration, and smart grid management. Such tools not only enhance learning but also prepare students for real-world challenges.

Methodology Layer: AI in Curriculum Development and Personalized Learning - Utilize AI to tailor educational content and delivery to individual student needs, optimizing learning pathways in energy studies. AI can analyze student performance and adapt curriculum in real-time, providing personalized resources, adjusting difficulty levels, and suggesting projects that align with both personal interest and industry needs. Additionally, AI can facilitate the inclusion of global energy case studies, keeping the curriculum up-to-date with the latest trends and technologies.

Social Layer: AI for Community Engagement and Impact - Leverage AI to analyze and improve the impact of community outreach programs related to energy education. AI tools can help in designing community-based energy projects that align with local needs and capabilities, enhancing the effectiveness of educational outreach. Furthermore, AI can be used to track the social impact of graduates in the energy sector, providing feedback to educational institutions on how well their programs are translating into real-world social and environmental benefits.

By integrating AI across these five layers, higher education institutions can create a responsive, efficient, and impactful model that not only advances energy education but also contributes significantly to sustainable energy solutions.

Figure 2.

Five layers of AI-Integrated Energy Education Framework. (Source: own elaboration).

Figure 2.

Five layers of AI-Integrated Energy Education Framework. (Source: own elaboration).

The AI-Integrated Energy Education Framework incorporates a multi-layered approach, where each layer is characterized by distinct key factors that collectively enhance the effectiveness and relevance of energy education. These layers—organizational, financial, technology, methodology, and social—each play a crucial role in the overall structure of the framework, contributing to its robustness and adaptability. The key factors within each layer are specifically designed to address the unique challenges and opportunities inherent in integrating artificial intelligence into educational settings. By defining and focusing on these factors, the framework aims to optimize various aspects of higher education from administration to curriculum development, ensuring that both the immediate educational needs and the broader community impacts are met. This structured approach facilitates a comprehensive evaluation and continuous improvement of the framework, making it a dynamic tool for advancing energy education in the age of AI.

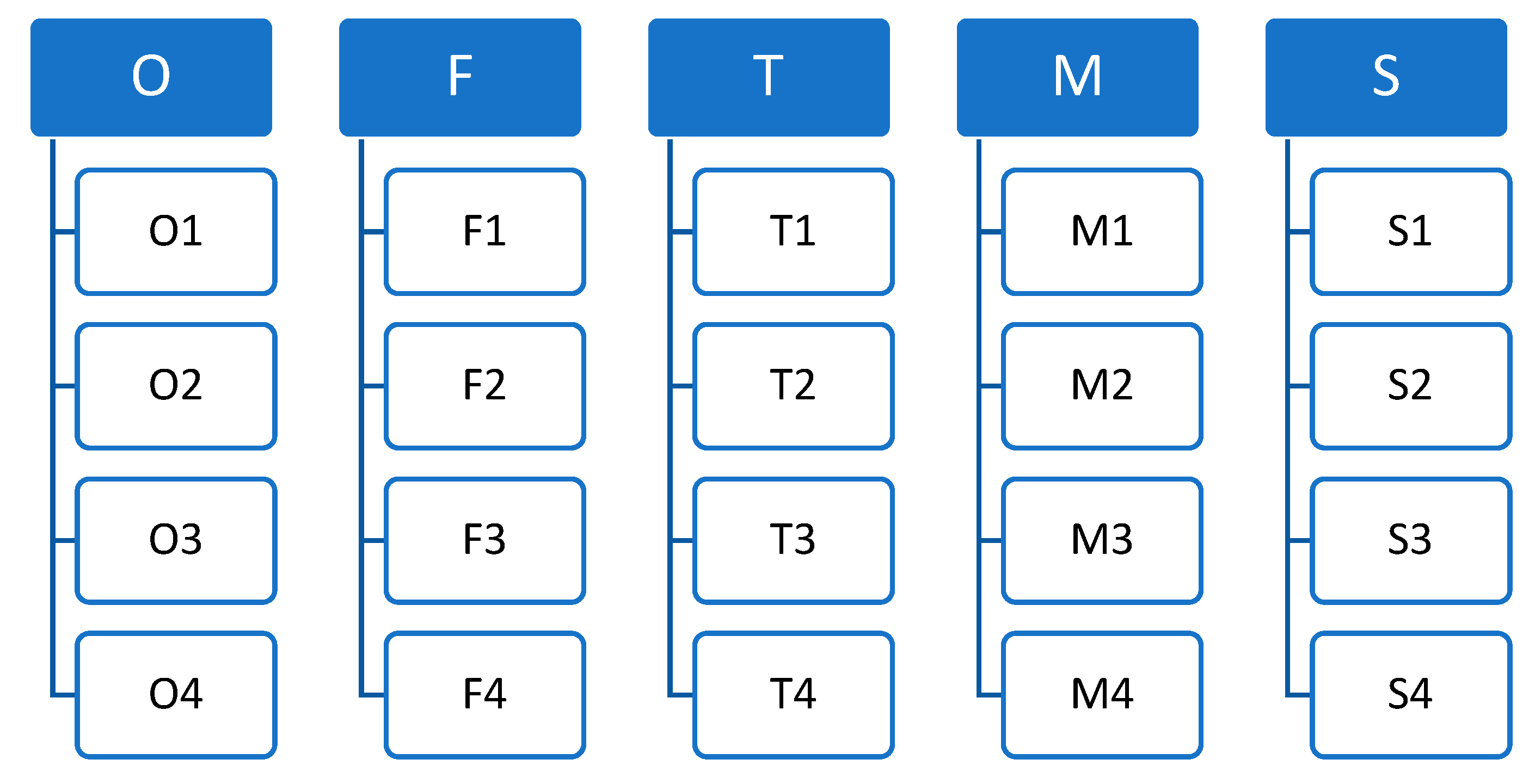

Here are AI-Integrated Energy Education Framework key factors for each layer:

1. Organizational Layer: AI-Enhanced Administration Systems

O1 - Energy Management Systems: Utilizing AI to monitor and optimize energy consumption across campus facilities.

O2 - Maintenance Prediction: Employing predictive analytics to forecast and schedule maintenance for energy-related infrastructure, reducing downtime and costs.

O3 - Resource Efficiency: Implementing AI-driven solutions to enhance resource allocation and efficiency, ensuring optimal use of both physical and human resources.

O4 - Strategic Planning Assistance: AI aids in the analysis of trends within energy education and the broader industry to inform strategic decisions regarding new programs and partnerships.

2. Financial Layer: Dynamic AI Financial Models

F1 - Real-Time Budgeting: Utilizing AI for dynamic financial planning and adjustments in real-time based on current financial data.

F2 - Funding Forecasting: AI tools predict financial requirements for energy-focused academic programs and initiatives, allowing for proactive budget allocation.

F3 - Grant Acquisition Support: Streamlining the process of identifying and applying for grants related to renewable energy and sustainability projects.

F4 - Resource Allocation Optimization: AI algorithms optimize the distribution of financial resources to maximize the impact on research and sustainability projects.

3. Technology Layer: Advanced Simulation and Modelling

T1 - Virtual Energy Labs: Creation of AI-powered virtual labs that simulate complex energy scenarios and interventions in energy markets.

T2 - Renewable Energy Integration Simulations: Using AI to model and predict the outcomes of integrating renewable energy sources into existing grids.

T3 - Smart Grid Management Tools: Advanced AI applications to manage and optimize smart grid operations, enhancing grid stability and efficiency.

T4 - Scenario Analysis: AI facilitates the exploration of various energy scenarios, helping students understand potential outcomes and implications.

4. Methodology Layer: AI in Curriculum Development and Personalized Learning

M1 - Adaptive Learning Algorithms: AI customizes learning experiences according to individual student needs and performance metrics.

M2 - Curriculum Real-Time Updating: Utilizing AI to keep educational content relevant with the latest energy studies and technological advancements.

M3 - Interactive Learning Projects: AI suggests and adjusts projects and practical exercises that align with both student interests and industry requirements.

M4 - Global Case Study Inclusion: Incorporation of global energy case studies into the curriculum, enabled by AI analysis and selection.

5. Social Layer: AI for Community Engagement and Impact

S1 - Community Project Design: AI assists in designing and implementing community-based energy projects tailored to local needs.

S2 - Impact Analysis: Analyzing the social and environmental impact of educational programs and community projects through AI metrics.

S3 - Graduate Tracking: Using AI to follow the careers of graduates in the energy sector to evaluate the real-world impacts of educational training.

S4 - Outreach Program Optimization: AI improves the effectiveness and reach of educational outreach programs, ensuring they meet community expectations and needs.

As we explore the integration of artificial intelligence into energy education, we are met with both significant opportunities and potential pitfalls. The "AI-Integrated Energy Education Framework" represents a shift towards utilizing AI to dramatically improve the efficiency and customization of learning environments, potentially transforming how educational content is delivered and assimilated. However, the adoption of such technology also raises complex questions regarding the implications of technological advancement, including ethical, economic, and educational considerations. Analyzing the advantages and disadvantages of this framework allows for a comprehensive discussion of AI’s impact on academia and society. Such analysis is crucial for responsibly guiding our technological initiatives, ensuring that we advance with a clear understanding of the responsibilities and consequences associated with these innovations.

Here are key advantages of proposed framework:

Enhanced Efficiency and Resource Management: AI's capability to analyze and optimize energy usage and other resources in real-time helps educational institutions reduce operational costs and improve sustainability.

Personalized Learning Experiences: AI enables the tailoring of educational content to meet the individual needs of students, adapting in real-time to their learning pace and preferences, which can lead to improved educational outcomes and student satisfaction.

Advanced Research Capabilities: The integration of AI-driven simulations and modeling tools allows students and researchers to engage with complex energy scenarios, enhancing their ability to conduct high-level research and develop innovative solutions.

Real-Time Financial Planning: AI-driven financial models can dynamically adjust to the changing needs of the institution, ensuring that funds are allocated efficiently and effectively, particularly in supporting cutting-edge energy research and sustainability projects.

Increased Community Engagement and Impact: AI tools can help design community-based projects that align with local needs and measure the impact of these initiatives, thereby strengthening the institution’s role in promoting sustainable energy solutions within the community.

While the AI-Integrated Energy Education Framework shows several benefits, it is important to consider potential disadvantages as well. Here are some disadvantages that should be taken into account:

High Implementation Costs: Setting up AI systems and maintaining them requires significant initial and ongoing investment, which might be prohibitive for some institutions, especially those with limited resources.

Dependency on Technology: Over-reliance on AI could make institutions vulnerable to technical failures or cyber-attacks, potentially disrupting educational and administrative operations.

Complexity and Skill Gaps: The complexity of AI systems necessitates specialized skills for operation and management. There could be a steep learning curve for staff and a need for continuous training to keep up with technological advancements.

Privacy and Ethical Concerns: The use of AI in educational settings raises concerns about data privacy, surveillance, and the ethical use of AI, such as biases in AI algorithms that could affect student assessment and learning opportunities.

Risk of Inequality: There is a risk that the benefits of AI-enhanced education may not be evenly distributed, possibly exacerbating existing disparities between institutions that can afford to implement such technologies and those that cannot.

Balancing these advantages and disadvantages will be crucial for institutions considering the adoption of the AI-Integrated Energy Education Framework. Such considerations will ensure that the potential benefits can be harnessed effectively while mitigating the associated risks.

5. Research Design and Methodology

This study employs a detailed methodology to assess the AI-Integrated Energy Education Framework using sophisticated fuzzy decision-making techniques. The evaluation process incorporates two main methods: the Fuzzy Delphi Method [

39] and the Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (FAHP) [

40]. Initially, the Fuzzy Delphi Method is utilized to gather and synthesize expert opinions and collective intelligence regarding each layer and key factor of the framework. This step aims to collect a wide range of perspectives to achieve a thorough understanding of the framework's effectiveness. Following this, the Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process is applied to determine the relative importance and assign weights to each component of the framework. These weights are crucial for effective prioritization and resource allocation, thereby directly influencing the framework's future development and successful deployment [

41]. The findings highlight the essential role of these weights in guiding the direction of future initiatives, ensuring they are well-aligned with the strategic goals of the AI-Integrated Energy Education Framework for efficient and sustainable management of energy education.

The research model outlines a structured four-step evaluation process for assessing the effectiveness of the framework:

Literature review.

The evaluation of AI-IEEF model by fuzzy Delphi method.

Weights for evaluation are determined by the fuzzy AHP method.

The interpretation of results and suggestions for further development are presented.

The initial step at this stage involves applying the fuzzy Delphi method to validate the layers and main factors proposed in the AI-Integrated Energy Education Framework (AI-IEEF) model. The Delphi method is characterized by four fundamental elements: independence of expert opinions, anonymity of judgments, a multi-stage nature of proceedings, and a collective aim to synthesize and agree on participant opinions. In relevant literature, the Delphi method is described as a technique for structuring group communication processes, designed to enhance the effectiveness of a community of independent individuals who collectively address a complex issue. The Delphi approach is classified among research methods in the realm of creative thinking and is defined as a multi-stage evaluation technique that relies on selective analysis of collected empirical data. Given that the traditional Delphi method has certain drawbacks, primarily the lengthy duration of the procedure and associated high research costs, modifications such as the fuzzy Delphi method are frequently utilized in scientific research [

42].

For purpose of the research, a panel of 11 experts, comprising 3 experts specializing in artificial intelligence (AI), 4 experts with expertise in education systems, and 4 experts in sustainable development and energy management, was surveyed to identify and prioritize the criteria and sub-criteria for evaluation. The survey, carried out in February 2024, provided key insights from experts that significantly influenced the direction of the research.

The panel of experts was divided into the following stages:

Evaluation of proposed layers.

Evaluation of main factors for each layer.

Fuzzification of the obtained values using triangular fuzzy numbers.

Data aggregation.

Data defuzzification.

Establishing an acceptance threshold.

Acceptance of layers and factors.

Following the adoption of the triangular fuzzy spectrum, experts' linguistic expressions (opinions) were gathered and converted into fuzzy values, as shown in

Table 1. In the second step, these expert opinions were consolidated using formula 1: the lower fuzzy number l (min) indicates the minimum possible value for each layer (or factor) as assessed by the experts, while the upper fuzzy number u (max) denotes the maximum possible value for each layer (or factor). The geometric mean (middle fuzzy number m) is used to represent the most probable value of each layer and factor.

In order to establish the layer and factor acceptance threshold, the aggregated values were defuzzied with Centre of Area method according to formula 2.

The last point at this stage, was to establish the acceptance threshold S=0,6, to filter and select the appropriate layer (5 of 5 were accepted,

Table 2) and 20 of 20 factors were accepted accordingly.

A graphical representation of the AI-IEEF model is shown in

Figure 3, along with all 20 key factors for each layer.

The next phase of this research aims to determine the weights for the specified layers and factors by employing the Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (FAHP). The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) is a well-established multi-criteria decision-making technique used to address complex issues in various fields. It operates on the principle of breaking down a decision problem into a hierarchical structure and then choosing the best solution based on the defined criteria and sub-criteria (layers and factors). However, a significant limitation of the AHP method is its inability to handle the uncertainties or vaguenesses typical in group decision-making processes. To overcome these challenges, the integration of fuzzy logic with AHP, referred to as FAHP, has been recommended [

43]. This combination provides a more accurate tool for assessing the issues and incorporating ambiguous or incomplete data. A critical step in the FAHP method is the creation of a pairwise comparison matrix, where standard numerical values are converted into fuzzy numbers using a specific membership function, often utilizing the triangular membership function as described in formula 3. This adjustment is consistent with Saaty's fundamental scale, which is detailed in

Table 3 and outlines the scale of relative importance.

The main purpose of pairwise comparisons is to evaluate how many times one element outweighs another in terms of their relative importance. If element A is favored very strongly over B, the fuzzy number is

and the fuzzy reciprocal value is

according to formula 4.

In the subsequent stage of the Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (FAHP), there is a crucial verification of the Consistency Ratio (C.R.). For matrices of sizes 3x3 and 4x4, it is expected that the C.R. should remain within 5% and 8% respectively. For larger matrices, the C.R. should not exceed 10% (C.R. ≤ 10%). If the consistency ratio falls within these limits, the pairwise comparisons are considered consistent. If, however, the C.R. exceeds 10%, it indicates a need for reassessment of the criteria to correct inconsistencies in the pairwise comparisons. This phase of the FAHP process also involves computing a defuzzied, normalized matrix for the selected criteria and determining the largest eigenvalue (λmax) of the matrix. The originator of the method indicated that pairwise comparisons are generally more consistent when the λmax value is close to the number of elements in the matrix (n). Based on this principle, the Consistency Index (C.I) is then calculated using formula 5.

and consistency ratio C.R to formula 6,

where R.I is a random consistency index, generated from several thousand matrices and proposed by the author in the form of

Table 4.

After verifying that the experts' opinions are consistent, fuzzy geometric mean

(formula 7) and fuzzy weights

for all the criteria were calculated (formula 8).

Next, fuzzy weights were defuzzied into crisp values w

i , with Centre of Area method (formula 9) and then normalized to

values, according to formula (10).

In the final phase of the study, the aggregation of results from eleven experts was performed using the geometric mean, which determined the ultimate weights for the five designated layers (as detailed in

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7). Following this, the next step in the Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (FAHP) involved implementing the same analytical methodology (described in formulas 3 to 10) to evaluate all factors within each layer. The research framework encompasses five layers, requiring a comparative analysis of all factors within each respective group. This comprehensive evaluation was conducted by a panel of eleven experts, culminating in the creation of a total of 55 tables. Due to the complexity of the empirical data, this article selectively presents excerpts of these calculations, which are available in Tables 10 - 12.

Following the validation (FAHP consistency test, CR<10%) and aggregation (using the geometric mean) of assessments from eleven experts for all pairwise comparisons (both layers and factors), the results were compiled as follows:

Weights for five layers,

Local weights for twenty factors,

Global weights for twenty factors, calculated as the product of the layer weight and the local factor weight.

6. Discussion

The Artificial Intelligence Integrated Energy Education Framework (AI-IEEF) represents a cutting-edge paradigm in modern energy education, providing a cohesive and adaptive approach to optimize energy management and enhance grid stability. As the need for efficient and sustainable energy solutions continues to grow, the adaptability of AI-IEEF becomes increasingly evident. Acknowledging the diverse contexts in which energy education operates, we present five distinct versions of AI-IEEF, each designed to meet specific scenarios. These variations underscore the importance of customizing the AI-IEEF to address the unique challenges and opportunities of different fields. Here, we explore the significance of these versions and their crucial role in influencing the future of energy management education:

1. Smart Campus Energy Education Variant – this variant focuses on turning the campus into a living lab for energy education. By integrating smart grid and predictive maintenance technologies into everyday campus operations, students can engage directly with cutting-edge solutions and data analytics for optimized energy management. Key factors:

Smart Grid Integration: Incorporating AI-enabled smart grid technologies to simulate and teach grid management in real time.

Energy Efficiency Modeling: Using AI to model and analyze campus energy usage, providing insights into consumption patterns.

Predictive Maintenance Training: Providing students with hands-on experience in predictive maintenance of campus energy infrastructure.

Renewable Energy Labs: Offering practical training in renewable energy sources through AI-managed solar and wind energy labs.

2. Global Energy Policy Analysis Variant – this variant emphasizes the role of policy in energy education by using AI to analyze, compare, and simulate the effects of global energy policies. It helps students understand the interconnectedness of international energy markets and the implications of strategic policy decisions. Key factors:

Policy Impact Simulations: Using AI to simulate the effects of different energy policies across various regions and economies.

Comparative Analysis Tools: Providing students with tools to compare global policy frameworks and their effectiveness.

Sustainability Metrics: Introducing students to AI models that assess the sustainability impact of policy decisions.

Cross-Border Collaboration: Creating AI platforms that facilitate policy collaboration across nations.

3. Renewable Energy Research and Development Variant – Designed to foster innovation in renewable energy, this variant helps students and researchers work collaboratively to develop, test, and commercialize new technologies. It focuses on optimizing research efforts through advanced simulations and collaborative platforms. Key factors:

Advanced Research Simulations: Using AI to model innovative renewable energy technologies.

Data-Driven Resource Management: Leveraging AI for optimizing research resources and funding allocations.

Collaborative Research Networks: Creating AI-based networks to connect research students with global experts and institutions.

Commercialization Support: Incorporating AI tools that facilitate the commercialization of renewable energy research.

4. Energy Workforce Development Variant – this variant is aimed at equipping students with the skills needed in the energy sector by closely aligning educational content with workforce demands. It uses AI to bridge gaps between academic training and professional requirements. Key factors:

Personalized Learning Paths: Utilizing AI to create individualized learning paths for students, catering to their unique career goals.

Skill Gap Analysis: Identifying gaps in student skills and aligning them with industry needs.

Industry Partnerships: Building connections with energy companies to ensure the curriculum meets workforce requirements.

Soft Skills Training: Integrating AI-driven assessments to enhance critical thinking, communication, and teamwork skills.

5. Community Engagement and Outreach Variant – this variant aims to involve students and faculty in developing sustainable energy projects that directly benefit local communities. By using AI to evaluate and refine these projects, it ensures that students learn the real-world impacts of their work and engage meaningfully with stakeholders. Key factors:

Localized Energy Projects: Developing AI-based frameworks for community-oriented energy projects.

Impact Evaluation: Using AI to measure and improve the social and environmental impact of community energy projects.

Educational Outreach Platforms: Creating online platforms to share knowledge with local stakeholders.

Sustainability Workshops: Conducting workshops to educate community members on sustainable energy practices.

These variants offer tailored approaches to energy education, equipping students to tackle a diverse range of challenges in the evolving energy sector. The Smart Campus Energy Education Variant turns campuses into living laboratories, where students interact with smart grid technologies and renewable systems to manage consumption using predictive analytics. The Global Energy Policy Analysis Variant employs AI simulations for international policy impact analysis, giving students a strategic understanding of policy-making across global markets. The Renewable Energy Research and Development Variant leverages collaborative research networks and advanced AI tools to accelerate innovation and commercialization of emerging energy technologies. The Energy Workforce Development Variant aligns curriculum content with industry requirements, offering personalized learning paths to fill skill gaps and improve career readiness. Finally, the Community Engagement and Outreach Variant promotes sustainable energy projects and measures their social impact through AI, fostering strong connections between students, institutions, and local communities. Together, these variants form a comprehensive framework that reflects the diverse challenges of energy education, preparing students for a technologically advanced, sustainable future.

7. Conclusions

The research explores the AI-Integrated Energy Education Framework (AI-IEEF), a groundbreaking model designed to transform energy management practices. Initially, a thorough evaluation was conducted to identify five distinct layers: Organizational (AI-enhanced administration systems), Financial (dynamic AI financial models), Technology (advanced simulation and modeling), Methodology (AI in curriculum development and personalized learning), and Social (AI for community engagement and impact). These layers, along with twenty key factors, were carefully selected through consensus by an expert panel, facilitated by the rigorous application of the fuzzy Delphi method. This foundational phase established a solid basis for subsequent analytical stages, ensuring that the chosen criteria were both relevant and reflective of the framework's multifaceted structure.

Following this, the Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) was introduced to determine the relative importance of each identified layer and factor. This analytical technique was used to calculate precise weights for each of the five layers and their corresponding key factors. By applying the Fuzzy AHP method, the research aimed to quantitatively evaluate the hierarchical relationships and contributions of each component. These weight calculations are critical, as they play a pivotal role in guiding the future development and effective implementation of the AI-IEEF. They inform resource allocation and strategic decision-making, ensuring the framework is optimized to meet the evolving needs of energy management. Furthermore, the five variants of the AI-IEEF, each tailored to a specific aspect of energy education, provide a comprehensive framework for addressing the diverse challenges and opportunities within the field.

Author Contributions

This paper was inspired by the assistance of artificial intelligence tools. The authors of this paper utilized the capabilities of the AI models to generate ideas and assist in formulating the main concepts discussed herein. However, it is important to note that the research and results, analysis, and conclusions presented in this paper were conducted entirely by the authors. While the AI model provided valuable assistance in generating ideas and content, the authors took full responsibility for the research process, including the selection of the topic, the development of the methodology, the collection and analysis of data, and the interpretation of the results. The authors used their expertise in the field of education, AI and energy systems to conduct the research and ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information presented.

Funding

Financed by the Minister of Science under the "Regional Excellence Initiative" Program. Agreement No. RID/SP/0045/2024/01.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- D. Khojasteh et al. Climate change science is evolving toward adaptation and mitigation solutions. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.-Clim. Change, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, Renewable energy, inequality and environmental degradation. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 356, 120563. [CrossRef]

- Danish, M.S.S. AI and Expert Insights for Sustainable Energy Future. Energies 2023, 16, 3309. [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, A.; Ellis, N.; Gladwin, D. Energy literacy: A review in education. J. Environ. Educ. 2024, 55, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Ye, S. F. Koch, and J. Zhang, Modelling Required Energy Consumption with Equivalence Scales. Energy J. 2022, 43, 123–145. [CrossRef]

- N.C. Gaitan, I. Ungurean, G. Corotinschi, and C. Roman, An Intelligent Energy Management System Solution for Multiple Renewable Energy Sources. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2531. [CrossRef]

- R.E. Liu et al., Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Western Canadian Natural Gas: Proposed Emissions Tracking for Life Cycle Modeling. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 9711–9720. [CrossRef]

- J. Sauerbrey, T. Bender, S. Flemming, A. Martin, S. Naumann, and O. Warweg, Towards intelligent energy management in energy communities: Introducing the district energy manager and an IT reference architecture for district energy management systems. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 2255–2265. [CrossRef]

- A. Holzinger, R. Goebel, R. Fong, T. Moon, K.-R. Mueller, and W. Samek, xxAI - Beyond Explainable Artificial Intelligence. in XXAI - BEYOND EXPLAINABLE AI: International Workshop, Held in Conjunction with ICML 2020, July 18, 2020, Vienna, Austria, Revised and Extended Papers, A. Holzinger, R. Goebel, R. Fong, T. Moon, K. R. Muller, and W. Samek, Eds., in Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence, vol. 13200. Cham: Springer International Publishing Ag, 2022, pp. 3–10. [CrossRef]

- A. Entezari, A. Aslani, R. Zahedi, and Y. Noorollahi, Artificial intelligence and machine learning in energy systems: A bibliographic perspective. Energy Strategy Reviews 2023, 45, 101017. [CrossRef]

- C. Chen, Y. Hu, M. Karuppiah, and P. M. Kumar, Artificial intelligence on economic evaluation of energy efficiency and renewable energy technologies. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2021, 47, 101358. [CrossRef]

- T. Schneider et al., Harnessing AI and computing to advance climate modelling and prediction. Nat. Clim. Change 2023, 13, 887–889. [CrossRef]

- X. Sun, S. Ullah, and F. Sher, How do digital financial inclusion, ICT diffusion, and education affect energy security risk in top energy-consuming countries? Energy Environ. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. C. Li and B. T.-M. Wong, Artificial intelligence in personalised learning: a bibliometric analysis. Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Annus, Education in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. TEM J. 2024, 13, 404–413. [CrossRef]

- I. Alvarez-Icaza and O. Huerta, Augmented intelligence for open education: bridging the digital gap with inclusive design methods. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1337932. [CrossRef]

- C.-C. Lin, A. Y. Q. Huang, and O. H. T. Lu, Artificial intelligence in intelligent tutoring systems toward sustainable education: a systematic review. Smart Learn. Env. 2023, 10, 41. [CrossRef]

- Z. Bahroun, C. Anane, V. Ahmed, and A. Zacca, Transforming Education: A Comprehensive Review of Generative Artificial Intelligence in Educational Settings through Bibliometric and Content Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12983. [CrossRef]

- A. Stecyk and I. Miciula, Harnessing the Power of Artificial Intelligence for Collaborative Energy Optimization Platforms. Energies 2023, 16, 5210. [CrossRef]

- i. Prasanth, D. J. Vadakkan, P. Surendran, and B. Thomas, Role of Artificial Intelligence and Business Decision. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2023, 14, 965–969.

- M. Ryo, Ecology with artificial intelligence and machine learning in Asia: A historical perspective and emerging trends. Ecol. Res. 2024, 39, 5–14. [CrossRef]

- M. Piran, A. Sharifi, and M. M. Safari, Exploring the Roles of Education, Renewable Energy, and Global Warming on Health Expenditures’. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14352. [CrossRef]

- F. Ozbay and I. Duyar, Exploring the role of education on environmental quality and renewable energy: Do education levels really matter?’. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2022, 4, 100185. [CrossRef]

- L.-G. Giraudet and A. Missemer, The history of energy efficiency in economics: Breakpoints and regularities’. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 97, 102973. [CrossRef]

- D. Peyerl, S. G. Relva, and V. O. da Silva, Energy Transition: Changing the Brazilian Landscape Over Time. in ENERGY TRANSITION IN BRAZIL, D. Peyerl, S. Relva, and V. DaSilva, Eds., Basel: Springer Nature Switzerland Ag, 2023, pp. 1–15. [CrossRef]

- K. Ekberg and M. Hultman, The Early History of Climate Change and Energy Policy in Sweden, 1974-1983’. Env. Hist. 2023, 29, 399–421. [CrossRef]

- T. Rokicki et al., Changes in the production of energy from renewable sources in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 993547. [CrossRef]

- J. Akpan and O. Olanrewaju, Sustainable Energy Development: History and Recent Advances’. Energies 2023, 16, 7049. [CrossRef]

- L. Kang, X. Wu, X. Yuan, and Y. Wang, Performance indices review of the current integrated energy system: From history and projects in China. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 53, 102785. [CrossRef]

- F. Triguero-Ruiz, A. Avila-Cano, and F. T. Aranda, Measuring the diversification of energy sources: The energy mix’. Renew. Energy 2023, 216, 119096. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhou, B. Sang, X. Feng, D. Wang, H. Yu, and Y. Li, Research on Application Technology of Mobile Energy Storage System for Multi-dimensional Scenarios. in 2023 5TH ASIA ENERGY AND ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING SYMPOSIUM, AEEES, New York: IEEE, 2023, pp. 1335–1340. [CrossRef]

- A. I. Arvanitidis, V. Agarwal, and M. Alamaniotis, Nuclear-Driven Integrated Energy Systems: A State-of-the-Art Review. Energies 2023, 11, 4293. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, P. Meng, X. Ding, L. Hu, X. Wu, and H. Hou, Review on Energy Storage Participation in Capacity Configuration and Scheduling Optimization in Modern Power System. in 2023 IEEE/IAS INDUSTRIAL AND COMMERCIAL POWER SYSTEM ASIA, I&CPS ASIA, New York: IEEE, 2023, pp. 1807–1811. [CrossRef]

- M. Rambabu, R. S. S. Nuvvula, P. P. Kumar, K. Mounich, M. E. Loor-Cevallos, and M. K. Gupta, Integrating Renewable Energy and Computer Science: Innovations and Challenges in a Sustainable Future. in 2023 12TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RENEWABLE ENERGY RESEARCH AND APPLICATIONS, ICRERA, in International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications. New York: IEEE, 2023, pp. 472–479. [CrossRef]

- E. F. Orumwense and K. Abo-Al-Ez, Applications, Challenges and Future Trends towards Enabling Internet of Things for Smart Energy Systems. in 2022 IEEE NIGERIA 4TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON DISRUPTIVE TECHNOLOGIES FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT (IEEE NIGERCON), New York: IEEE, 2022, pp. 641–647. [CrossRef]

- On Machine Learning-Based Techniques for Future Sustainable and Resilient Energy Systems-Web of Science Core Collection’. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000966724100001 (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- M. R. Tur, Energy Supply Security and Artificial Intelligence Applications’. Insight Turk. 2022, 24, 213–233. [CrossRef]

- J. Nyangon, Climate-Proofing Critical Energy Infrastructure: Smart Grids, Artificial Intelligence, and Machine Learning for Power System Resilience against Extreme Weather Events’. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2024, 30, 03124001. [CrossRef]

- D. Abdul, J. Wenqi, A. Tanveer, and M. Sameeroddin, Comprehensive Analysis of Renewable Energy Technologies Adoption in Remote Areas Using the Integrated Delphi-Fuzzy AHP-VIKOR Approach’. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 49, 7585–7610. [CrossRef]

- B. Xue, F. Lu, J. Guo, Z. Wang, Z. Zhang, and Y. Lu, Research on Energy Efficiency Evaluation Model of Substation Building Based on AHP and Fuzzy Comprehensive Theory’. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14493. [CrossRef]

- V. T. Nguyen and R. Chaysiri, Spherical Fuzzy AHP-VIKOR Model Application in Solar Energy Location Selection Problem: A Case Study in Vietnam. in 2022 17TH INTERNATIONAL JOINT SYMPOSIUM ON ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND NATURAL LANGUAGE PROCESSING (ISAI-NLP 2022) / 3RD INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND INTERNET OF THINGS (AIOT 2022), New York: IEEE, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Lu, L. Zhao, X. Wang, H. Zhao, J. Wang, and B. Li, Comprehensive performance assessment of energy storage systems for various application scenarios based on fuzzy group multi criteria decision making considering risk preferences. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108408. [CrossRef]

- S.W. Chisale and H. S. Lee, Evaluation of barriers and solutions to renewable energy acceleration in Malawi, Africa, using AHP and fuzzy TOPSIS approach. Energy Sustain Dev. 2023, 76, 101272. [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Fundamentals of Decision Making and Priority Theory With the Analytic Hierarchy Process. RWS Publications, 2012.

- J. Mazurek and P. Linares, Some notes on non-reciprocal matrices in the multiplicative pairwise comparisons framework. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2024, 75, 955–966. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).