1. Introduction

Neurodegenerative disorders are caused by the dysfunction of nigral dopaminergic neurons [

1]. Neurodegenerative disorders is caused by various factors including age, family history, smoking, and exposure to specific chemicals such as 1-methyl-4-phenyl tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), annonacin, and antagonistic compounds to β2-adrenoreceptor [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Chronic neurodegenerative pathologies in central nervous system (CNS) show common features including oxidated inflammation, denatured protein, synaptic dysfunctions and defective autophagia [

6,

7]. In the neurodegenerative disorders, various antioxidants in phytoextracts are effective on preventing of the disorders without side effects [

8]. Additionally, activation of various compounds, including levodopa, dopamine agonists, safinamide, and monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors have been used to treat the disorders [

6].

SH-SY5Y cells, neuroblastoma cell are used widely in various neuronal studies for metabolism, neurotoxicity, neuroprotection and differentiation. Among the those, this cell line is the most applied for neurodegenerative disorders [

8,

9,

10]. For modeling of neurodegenerative disorders in in vitro, the cell line exposed to 6-Hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) in many studies [

11,

12].

6-OHDA, a neurotoxin, is known to induce neurodegenerative disorders besides PD [

9]. Although 6-OHDA does not induce all neurodegenerative disorders, 6-OHDA exposure models in neurons presented various pathologic features, including neurodegeneration, inflammation, and apoptosis due to oxidative stress [

9]. 6-OHDA enters dopaminergic and noradrenergic neurons and inhibits the reuptake of their neurotransmitters [

10]. During neuronal destruction, reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide, accumulate in neurons [

10].

Under intrinsic cellular stresses, such as DNA damage, hypoxia, UV, and exposure to chemicals, mitochondria in neurons release cytochrome c through assembled Bax proteins, and the released cytochromes and activated caspase 9 enhance cellular apoptosis [

11]. When 6-OHDA triggers the production of ROS, monoamine oxidase (MAO) A and B are expressed in neurons, and MAOB produces ROS by the degradation of dopamine in neurons [

12]. To protect against stress, cells express several proteins, including members of the Bcl-2 family [

13], cytokine response modifier A (crmA) [

14], and inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) [

15]. The Bcl-2 family of 20 proteins is involved in the regulation of cellular apoptosis. The Bcl-2 proteins (A1, Bcl-2, Bcl-w, Bcl-xL, Bcl-B, and Mcl-1) inhibit apoptotic proteins, including Bax, Bak, and Bok [

16]. Caspase-3 (Cas3) interacts with caspase-8 and -9, which play a central role in apoptosis, and Cas3 activates the production of Aβ peptide from the cleavage of amyloid-beta 4A precursor protein associated with Alzheimer’s disease [

17].

Allium senescens is a perennial aromatic herb distributed in northern Europe and Asia, especially the Ulleung Island in Korea [

18].

A. senescens is effective in refreshing blood and controlling cholesterol levels in the blood [

19], to activate detoxification and restore functions in the liver [

20].

The genus

Artemia of anostracan crustaceans is also known as brine shrimp [

21,

22]. There are four distinct developmental stages of brine shrimp: cyst, emergence, nauplius, and adult [

21,

22]. This animal’s plankton provides a useful model for neurological research because of its short developmental stages [

21,

22]. The central nervous system (CNS) and ventral system are actively developed during the nauplius stages of brine shrimp [

21,

22].

The goal of this research was to explore the potentiality of preventive function of the hydrolytic extract of A. senescens against oxidative neurodegeneration and to prove the usefulness of the extract as a functional food.

2. Materials and Methods

- A. senescens extract

After drying and grinding (35 mesh), the leaves of A. senescens (Ulleung, Korea) were extracted twice with hydration for 90 min. The filtered extract was concentrated (R-3000, BuCHI Labortechnik AG, Germany) at 60 ℃and lyophilized using a freeze dryer (FD8505, Ilshin Lab Co., Korea). The extract was supported by EVERBIO (Chungcheongbuk-do, Korea).

- Cell culture

SH-SY5Y cells (Korea Cell Bank, Seoul, Korea) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 µg/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C and 5% CO2. To establish treatment dosages, SH-SY5Y cells were exposed to 40, 80, 100, 200, 300, and 400 µM 6-OHDA (162957, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and 50, 100, 500, 1000, and 2000 µg/mL of the extracts for 12 h. SH-SY5Y cells were exposed to 6-OHDA for 1 h after treatment with the extract (500 µg/mL).

- Animal plankton culture.

The cysts (1 g) of brine shrimp (

Artemia franciscana) were cultured in 3 L of artificial seawater (pH 8.2, 28 °C) with air supply for 2 days. After sorting early Nauplii using a submarine assay [

22], treatment dosages of 6-OHDA and the extract were established. For whole-mount immunohistochemistry and the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay, nauplii were exposed to 6-OHDA for 30 min after treatment with the extract for 30 min.

- Cell viability test

To evaluate viability, neuroblast cells were stained with Annexin V-conjugated propidium iodide (PI) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and counted using a flow cytometer (FACScalibur, BD science, San Jose, CA, USA) and FlowJo 10.6.1 (BD Biosciences).

- Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using the RiboEx reagent (GeneAll, Seoul, Korea). The RNA was then reverse-transcribed into cDNA using a Maxime RT PreMix (iNtRON, Seongnam, Korea), and quantitative PCR was performed with primers (

Table 1) with the following cycling parameters: 1 min at 95 °C, followed by 35 cycles of 35 s at 59 °C and 35 cycles of 1 min at 72 °C. The expression levels of the target genes in the samples were normalized to those of the housekeeping gene GAPDH, and the relative quantities of the target genes were determined with respect to those of the control.

- Flow cytometry

All cellular samples were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 4 h and treated with 0.02% Tween 20 for 5 min. After blocking using an Fc blocking solution (BD Bioscience), samples were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-anti-MAOB (Biocompare, Inc., CA, USA) and Alexa Fluor 680-anti-Cas3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., TX, USA) for 2 days. The treated samples were washed using phosphate-buffered saline and analyzed using a flow cytometer (BD FACScalibur) and FlowJo 10.7.0 (BD Bioscience).

- Mitochondrial apoptosis

After exposure to the three substances for 3 days, EC cells were stained with JC-1 Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assay Kit (Invitrogen, MA, USA), and mitochondrial activity was estimated using a flow cytometer (BD FACScalibur) and FlowJo 10.6.1 (BD Biosciences).

- Cellular ROS detection

All cultured cells exposed to 6-OHDA and the extract were stained with DCFDA - Cellular ROS Assay Kit (Abcam) for 30 min and were measured using a flow cytometer (BD FACScalibur) and FlowJo 10.7.0 (BD Bioscience).

- TUNEL assay

All nauplius samples were stained with a TUNEL assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and the fluorescence intensity and counting of stained colonies were estimated using a fluorescence microscope (Eclipse Ts-2, Nikon, Shinagawa, Japan) and the imaging software NIS-elements V5.11 (Nikon).

- Whole-mount immunohistochemistry.

All nauplius samples were treated with 4% paraformaldehyde for 4 h and treated with 0.02% Tween 20 for 15 min. The treated samples were stained with Alexa Fluor 680-anti-Cas3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., TX, USA) for 4 days [

21,

22]. The fluorescence intensity of the stained nauplii was evaluated and imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Eclipse Ts-2, Nikon, Shinagawa, Japan) and imaging software, NIS-elements V5.11 (Nikon). All cultured cells were pretreated 10% BSA(Sigma) for 4 hours to be specificity of antibodies.

- Statistical analysis

All experiments were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the post hoc test (Scheffe’s method) using Prism 7 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) software.

4. Discussion

his study documented the protective function of

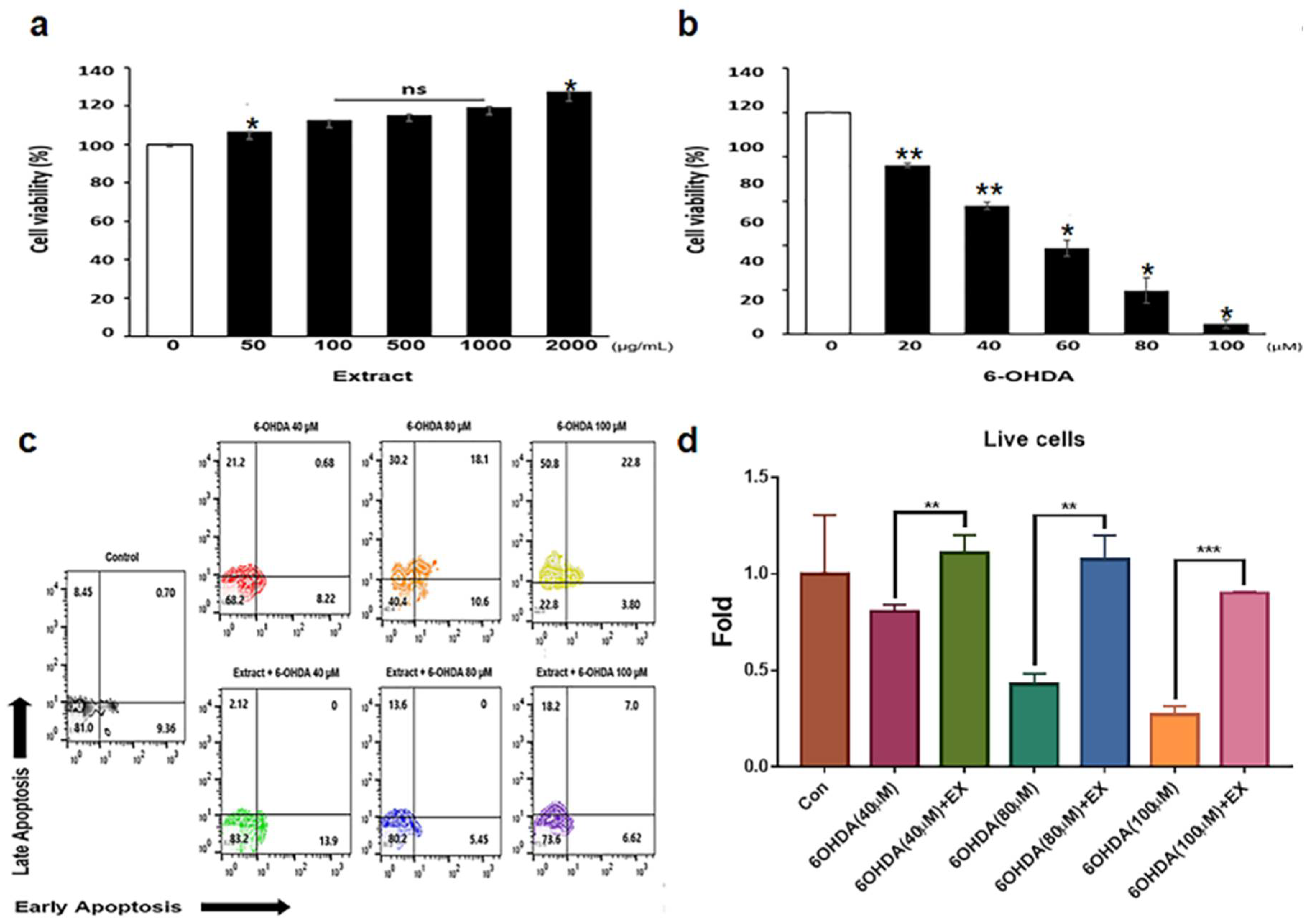

A. senescence extract against modeled cells for oxidative neurodegeneration and an invertebrate animal, brine shrimp. Based on the results of cell viability analysis (

Figure 1), the extract was not cytotoxic to neuronal cells. Non-cytotoxic phytoextracts are useful in the application of functional foods. Interestingly, this study demonstrated three protective functions against 6-OHDA induced oxidative stress.

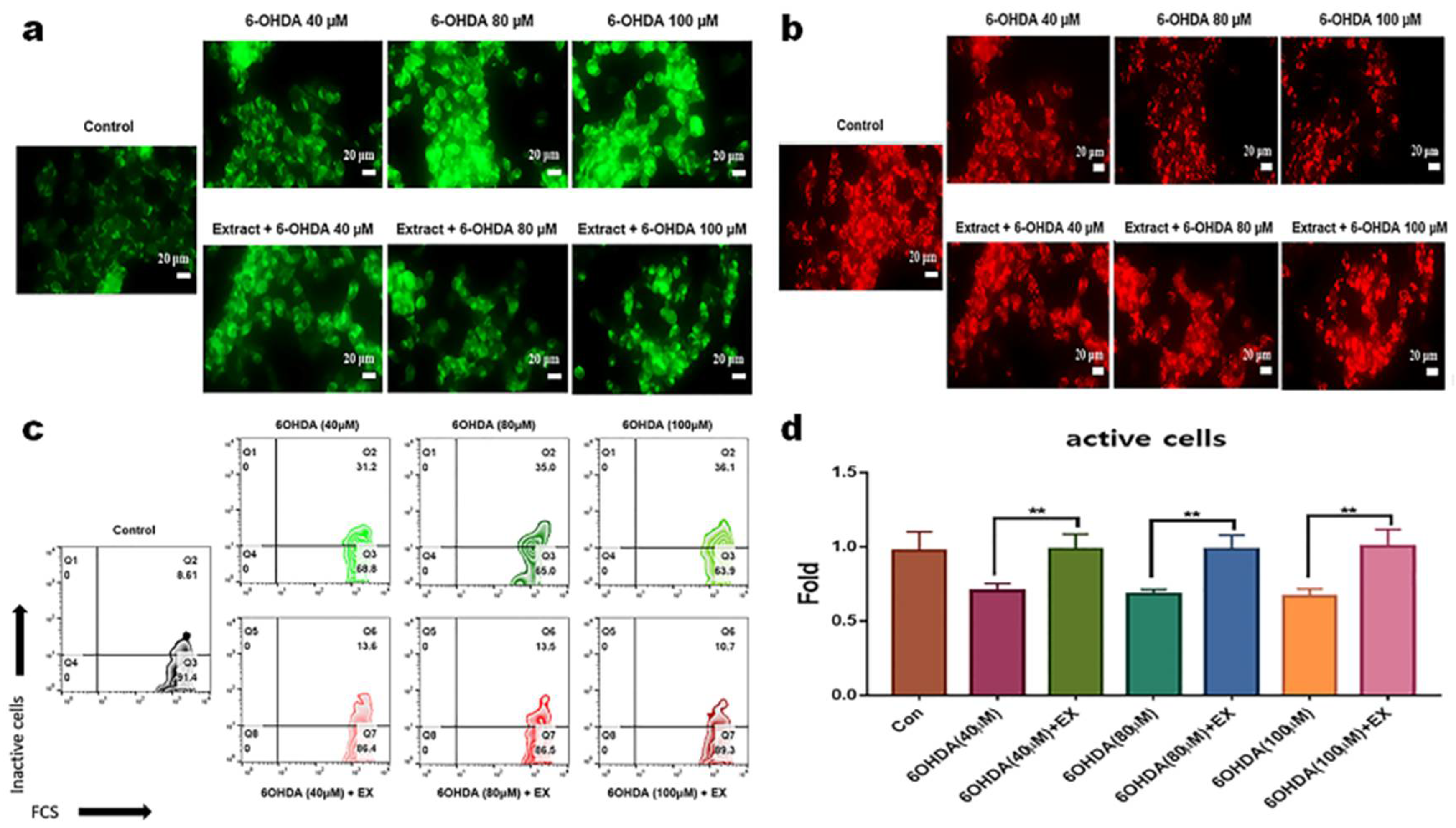

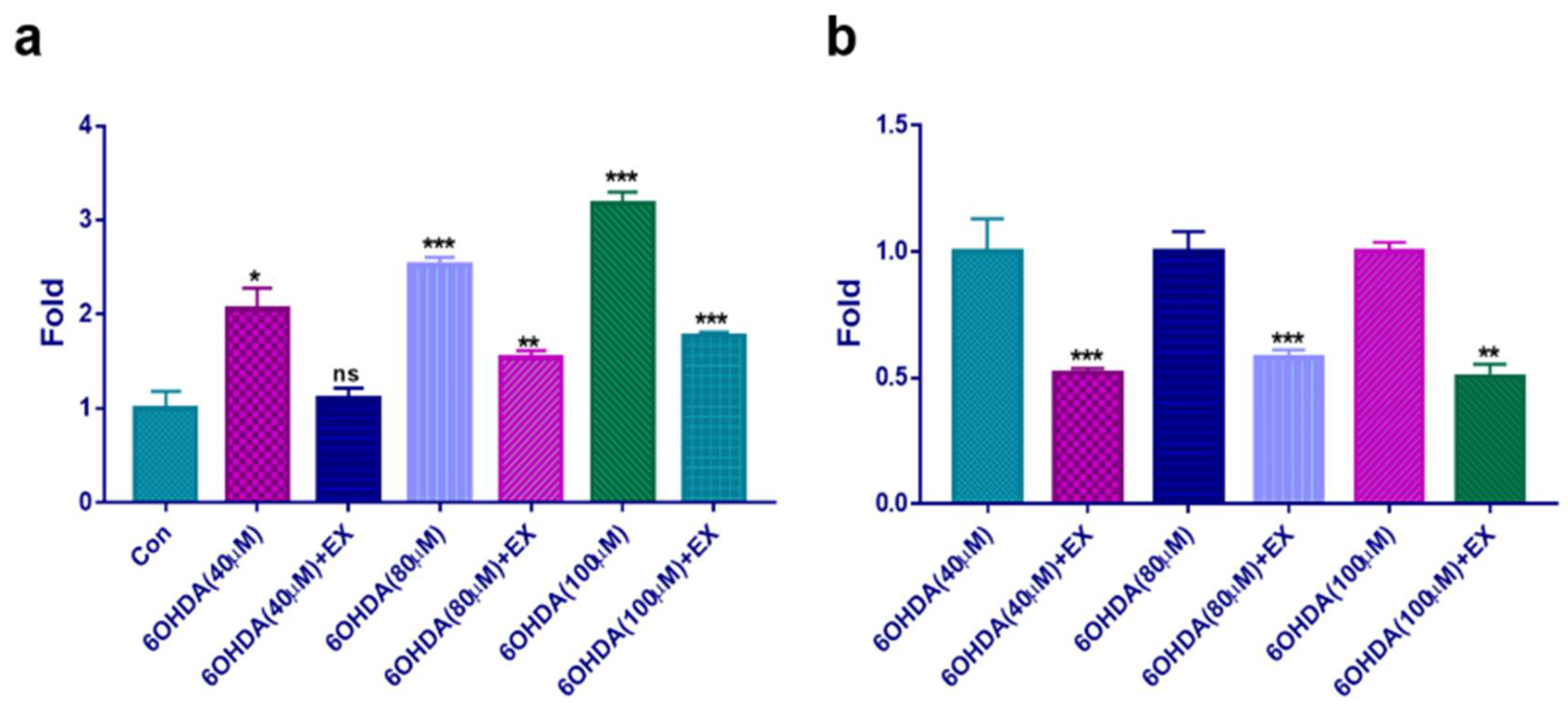

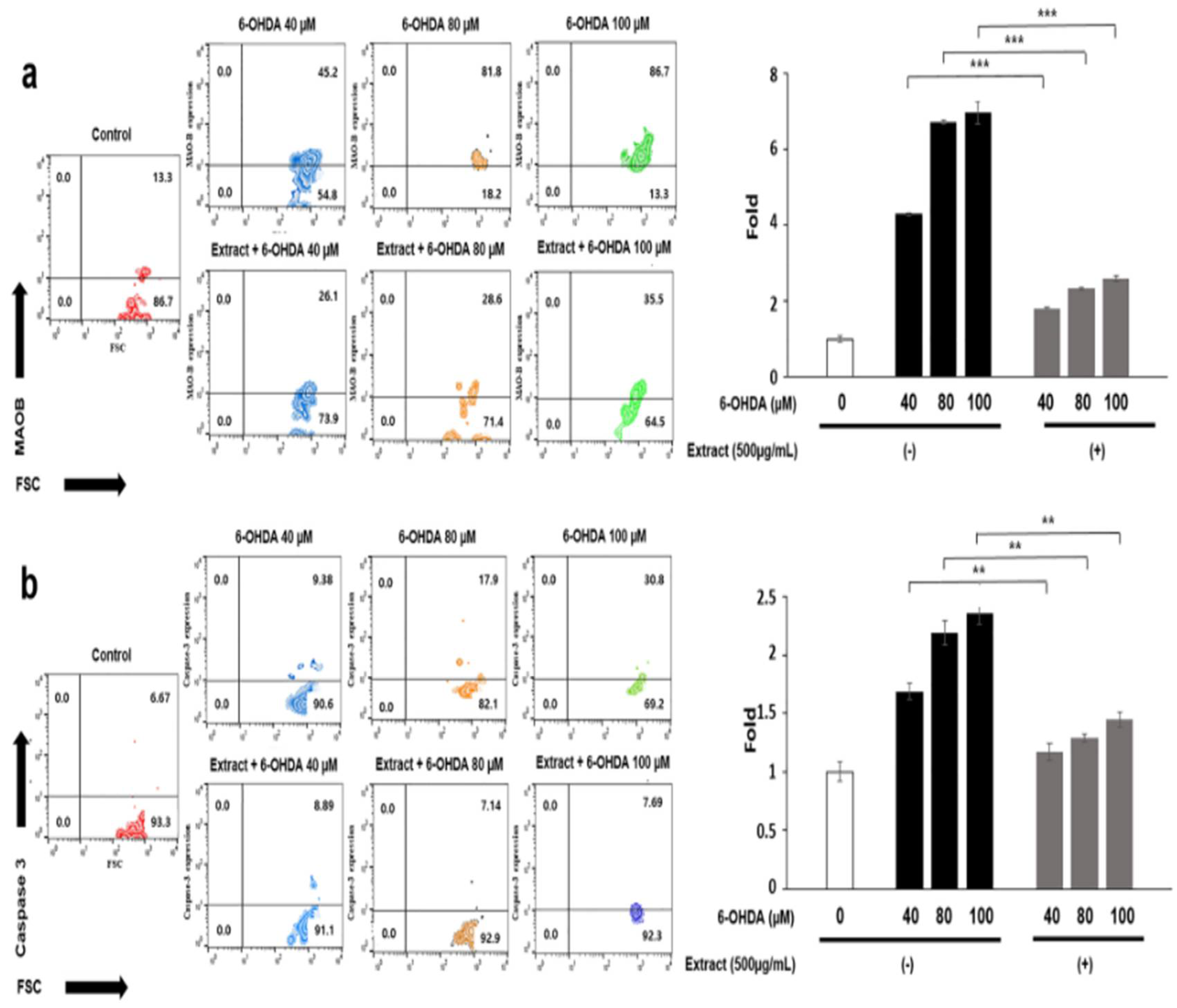

First, the extract prevented mitochondrial apoptosis by decreasing ROS levels in neuroblast cells. Although 6-OHDA inhibited mitochondrial activity, the extract maintained its activity in addition to decreasing ROS under 6-OHDA treatment. Moreover, the extract downregulated MAOB and Cas3 in the neuroblast cells. Under ROS accumulation, the CNS triggers neurodegeneration and accelerates aging [

23]. ROS are toxic to various molecules, including proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and DNA [

24]. Furthermore, accumulated ROS causes neurodegenerative disorders [

25]. These results documented the potential functions of the extract in the prevention of oxidative neurodegeneration.

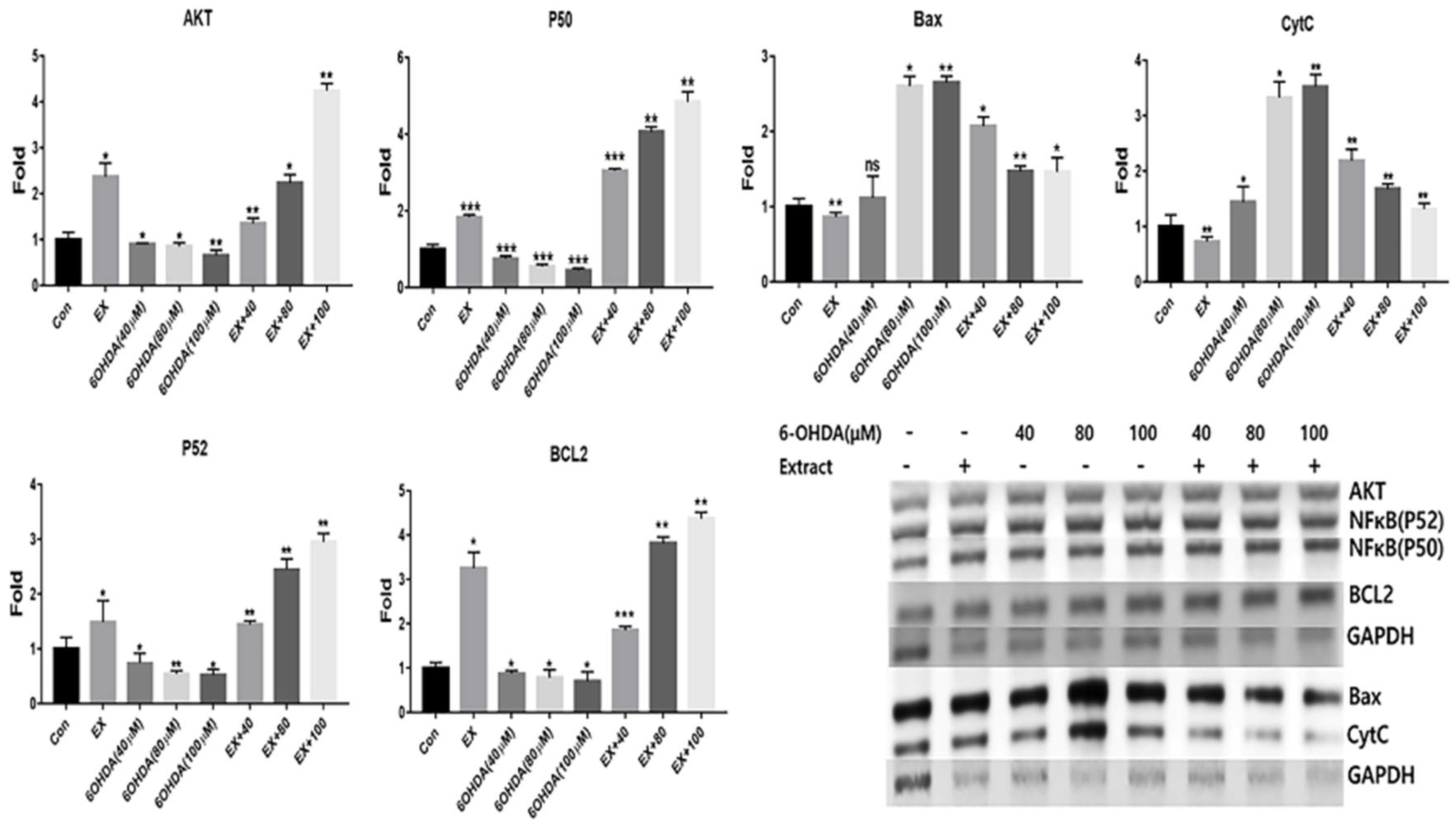

Second, the extract was found to drive the expression of apoptotic and anti-apoptotic genes. The extract activated the upregulation of anti-apoptotic genes, but not of apoptotic genes. As shown in

Figure 5, all concentrations of 6-OHDA decreased the apoptotic markers. However, the extract dramatically increased the levels of the apoptotic markers despite exposure to 6-OHDA. In particular, the protective effect of extract for neurodegeneration increased dependently on 6-OHDA concentrations (

Figure 5). Increased ROS levels trigger the upregulation of apoptotic genes in the mitochondria [

26]. In neurons, NF-κB affects neuronal survival and apoptosis under mitochondrial dysfunction [

27]. Furthermore, with increased ROS levels, activation of NF-κβ without upregulation of BCL-2 promoted the activation of the apoptotic signaling pathway [

27]. The activation of these two molecules indicates that the extract protects neuronal cells from apoptosis induced by 6-OHDA. Increased ROS levels inhibits the upregulation of

AKT and

BCL-2 genes, but not of Bax, which activates the upregulation of CytC and Cas3 [

28]. Although 100 μM 6-OHDA significantly downregulated

AKT gene expression and upregulated

Bax and

CytC genes, the extract dramatically modulated AKT, Bax, and CytC gene expression to promote the survival of neuroblast cells following exposure to 6-OHDA (

Figure 5). These results suggest that the extract is effective in preventing mitochondrial apoptosis in neuroblast cells.

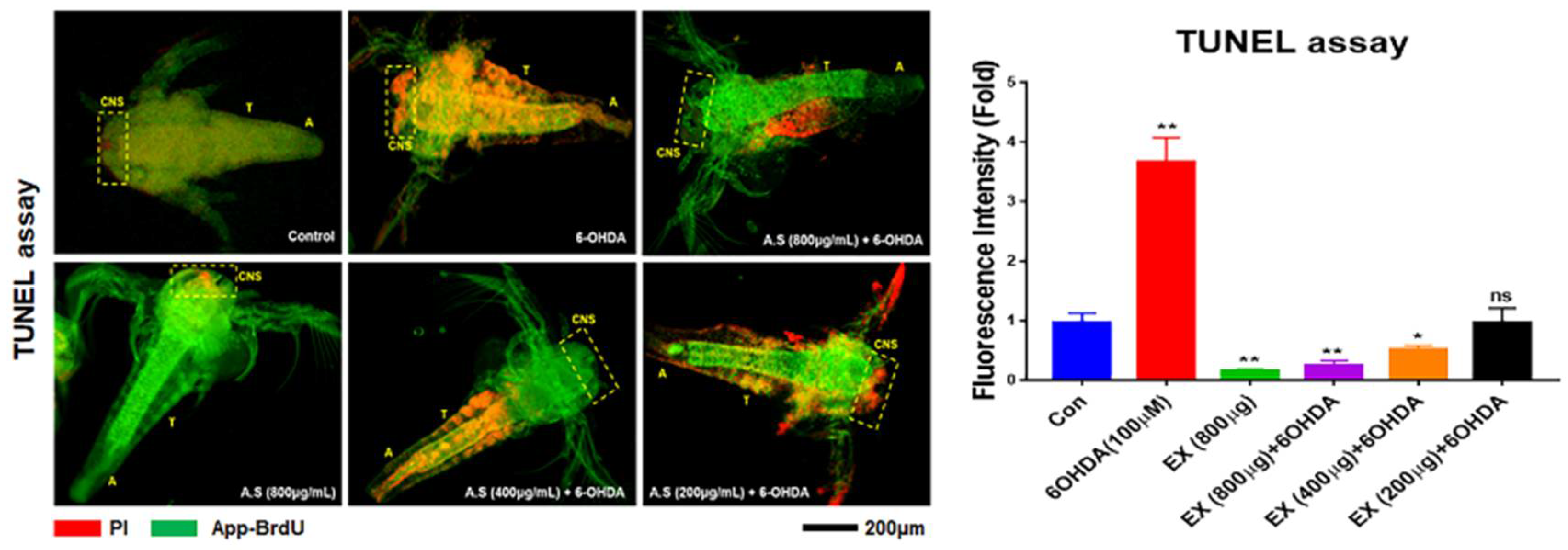

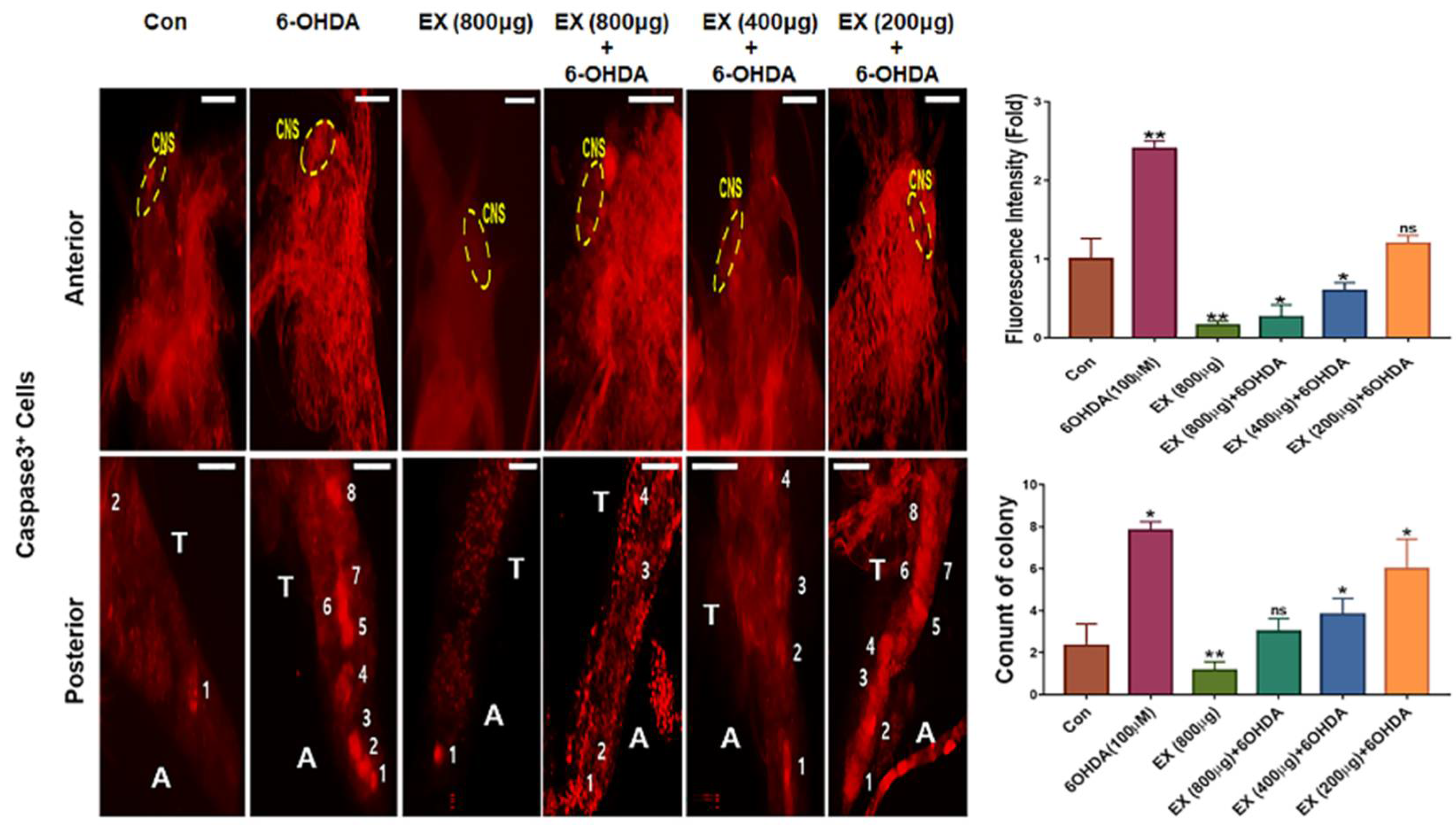

Third, the extract protected the CNS and VNS against oxidative apoptosis in vivo. In the developing brine shrimp (

Figure 6), the extract prevented apoptosis of cells of the CNS and VNS and VC under 6-OHDA treatment. Without the extract, 6-OHDA treatment accelerated the apoptosis of CNS and VNS and VC in brine shrimp. Interestingly, 6-OHDA intensely induced apoptosis of protocerebrum, particularly mushroom bodies (MB) in the CNS of nauplii, but the protective function of the extract against oxidative stress was dramatically effective in nauplii (

Figure 6 and 7). Brine shrimp is used in toxicological assays for chemicals, water pollution, and natural products [

29]. Additionally, the neuronal development of brine shrimp is activated in the early nauplius [

21]. Neuronal cells in the early nauplius show a sensitive response to toxic chemicals [

21,

29]. PD is caused by the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in a specific area, called the substantia nigra. Corresponding with this specific area, in insects, functions of the MB include the reception and processing of sensory signals from olfactory, visual, mechanosensory systems, establishment of memory for behavior, and motor control [

30]. In brine shrimp, MBs are localized at the protocerebrum and are synthesized dopamine transporters [

21]. At an extract concentration of 800 μg/mL, although the protective effect was not intense in segmental neurons, protection of the CNS was dramatically effective in early nauplii (

Figure 6). These results suggest that the extract is more effective in the CNS than in the VNS, in vivo. Compared with cells treated with 6-OHDA alone, those treated with the extract showed dramatically reduced mitochondrial apoptosis in the CNS and VC, in vivo (

Figure 7). These protective effects of the extract in vivo provide conclusive evidence for its potential for the prevention of oxidative neurodegeneration, in addition to the results from neuroblast cells.

Figure 1.

Cellular viability and apoptosis of Allium senescens extract and 6-OHDA in neuroblast cells. (a, b) Cellular viability of neuroblast cells treated with the extract and 6-OHDA (P < 0.05). (c) Apoptosis of neuroblast cells treated with the extract (500); 500 μg/mL and the indicated concentrations of 6-OHDA. (d) Histograms showing the relative fold changes in the number of live cells under treatment with the extract and 6-OHDA based on the panel C. ns; not significant, EX; Allium senescens extract 500 μg/mL, 6-OHDA; 6-hydroxydopamine. (** P <0.01, *** P <0.001). .

Figure 1.

Cellular viability and apoptosis of Allium senescens extract and 6-OHDA in neuroblast cells. (a, b) Cellular viability of neuroblast cells treated with the extract and 6-OHDA (P < 0.05). (c) Apoptosis of neuroblast cells treated with the extract (500); 500 μg/mL and the indicated concentrations of 6-OHDA. (d) Histograms showing the relative fold changes in the number of live cells under treatment with the extract and 6-OHDA based on the panel C. ns; not significant, EX; Allium senescens extract 500 μg/mL, 6-OHDA; 6-hydroxydopamine. (** P <0.01, *** P <0.001). .

Figure 2.

Protective effect of the extract for mitochondrial apoptosis of neuroblast cells. (a, b) Estimation of mitochondrial membrane potential using fluorescence microscopy. Red and green colors indicate live and dead cells, respectively. (c, d) Flow cytometric counts of inactive cells and histograms (d) showing the counts of inactivated cells based on the panel C. EX; Allium senescens extract 500 μg/mL, 6-OHDA; 6-hydroxydopamine. (** P <0.01, *** P <0.001). (White bars = 20 μm) (** P <0.01). .

Figure 2.

Protective effect of the extract for mitochondrial apoptosis of neuroblast cells. (a, b) Estimation of mitochondrial membrane potential using fluorescence microscopy. Red and green colors indicate live and dead cells, respectively. (c, d) Flow cytometric counts of inactive cells and histograms (d) showing the counts of inactivated cells based on the panel C. EX; Allium senescens extract 500 μg/mL, 6-OHDA; 6-hydroxydopamine. (** P <0.01, *** P <0.001). (White bars = 20 μm) (** P <0.01). .

Figure 3.

Evaluation of ROS production in neuroblast cells treated with the extract . (a) ROS production under various conditions. (b) Relative fold changes for ROS production in cells exposed to various concentrations of 6-OHDA and treated with the extract. Con; control, EX; Allium senescens extract 500 μg/mL, 6-OHDA; 6-hydroxydopamine, ns; not significant. (*P < 0.05, ** P <0.01, *** P <0.001). .

Figure 3.

Evaluation of ROS production in neuroblast cells treated with the extract . (a) ROS production under various conditions. (b) Relative fold changes for ROS production in cells exposed to various concentrations of 6-OHDA and treated with the extract. Con; control, EX; Allium senescens extract 500 μg/mL, 6-OHDA; 6-hydroxydopamine, ns; not significant. (*P < 0.05, ** P <0.01, *** P <0.001). .

Figure 4.

Expression of the markers for mitochondrial apoptosis in neuroblast cells treated with the extract. (a, b) After gating for population of live cells, the results for the markers of mitochondrial apoptosis were evaluated using flow cytometry. Histograms showing relative fold changes in cell counts. EX; Allium senescens extract 500 μg/mL, 6-OHDA; 6-hydroxydopamine (*P < 0.05, ** P <0.01, *** P <0.001). .

Figure 4.

Expression of the markers for mitochondrial apoptosis in neuroblast cells treated with the extract. (a, b) After gating for population of live cells, the results for the markers of mitochondrial apoptosis were evaluated using flow cytometry. Histograms showing relative fold changes in cell counts. EX; Allium senescens extract 500 μg/mL, 6-OHDA; 6-hydroxydopamine (*P < 0.05, ** P <0.01, *** P <0.001). .

Figure 5.

The mRNA levels for apoptotic markers in neuroblast cells treated with the extract Evaluation of levels of the antiapoptotic markers (AKT, P50, P52, BCL-2) and apoptotic markers (Bax and CytC). Histograms showing relative fold changes in the signal intensity of the amplified DNA products. EX; Allium senescens extract 500 μg/mL, 6-OHDA; 6-hydroxydopamine, ns; not significant, EX+40, 80, 100; 6-OHDA treatment after exposure to the extract. (*P < 0.05, ** P <0.01, *** P <0.001). .

Figure 5.

The mRNA levels for apoptotic markers in neuroblast cells treated with the extract Evaluation of levels of the antiapoptotic markers (AKT, P50, P52, BCL-2) and apoptotic markers (Bax and CytC). Histograms showing relative fold changes in the signal intensity of the amplified DNA products. EX; Allium senescens extract 500 μg/mL, 6-OHDA; 6-hydroxydopamine, ns; not significant, EX+40, 80, 100; 6-OHDA treatment after exposure to the extract. (*P < 0.05, ** P <0.01, *** P <0.001). .

Figure 6.

Effects of the extract on oxidative stress in the CNS and VNS of brine shrimp.

Figure 6.

Effects of the extract on oxidative stress in the CNS and VNS of brine shrimp.

Figure 7.

Effects of the extract on mitochondrial apoptosis in the CNS and VC of brine shrimp.

Figure 7.

Effects of the extract on mitochondrial apoptosis in the CNS and VC of brine shrimp.

Table 1.

The list of primers for qRT-PCR.

Table 1.

The list of primers for qRT-PCR.

| Gene |

F/R* |

Seq (5’ → 3’) |

| AKT |

F |

GGCTGCCAAGTGTCAAATCC |

| R |

AGTGCTCCCCCACTTACTTG |

| NFκB-P50 |

F |

CGGAGCCCTCTTTCACAGTT |

| R |

TTCAGCTTAGGAGCGAAGGC |

| NFκB-P52 |

F |

AGGTGCTGTAGCGGGATTTC |

| R |

AGAGGCACTGTATAGGGCAG |

| Bcl2 |

F |

CTGCTGACATGCTTGGAAAA |

| R |

ATTGGGCTACCCCAGCAATG |

| BAX |

F |

AGCGCTCCCCCACTTACTTG |

| R |

GACAGGGACATCAGTCGCTT |

| Cyt |

F |

ATGAATGACCACTCTAGCCA |

| R |

ATAGAAACAGCCAGGACCGC |

| GAPDH |

F |

GTGGTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACA |

| R |

CTCTTCCTCTTGTGCTCTTGCT |