Submitted:

06 May 2024

Posted:

09 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Pancreatic Cancer: Overview, Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment

Overview and Application of Oncolytic Viruses

Overview and Application of Tanapox Oncolytic Virus

Results

Replication Kinetics of TPV in Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells

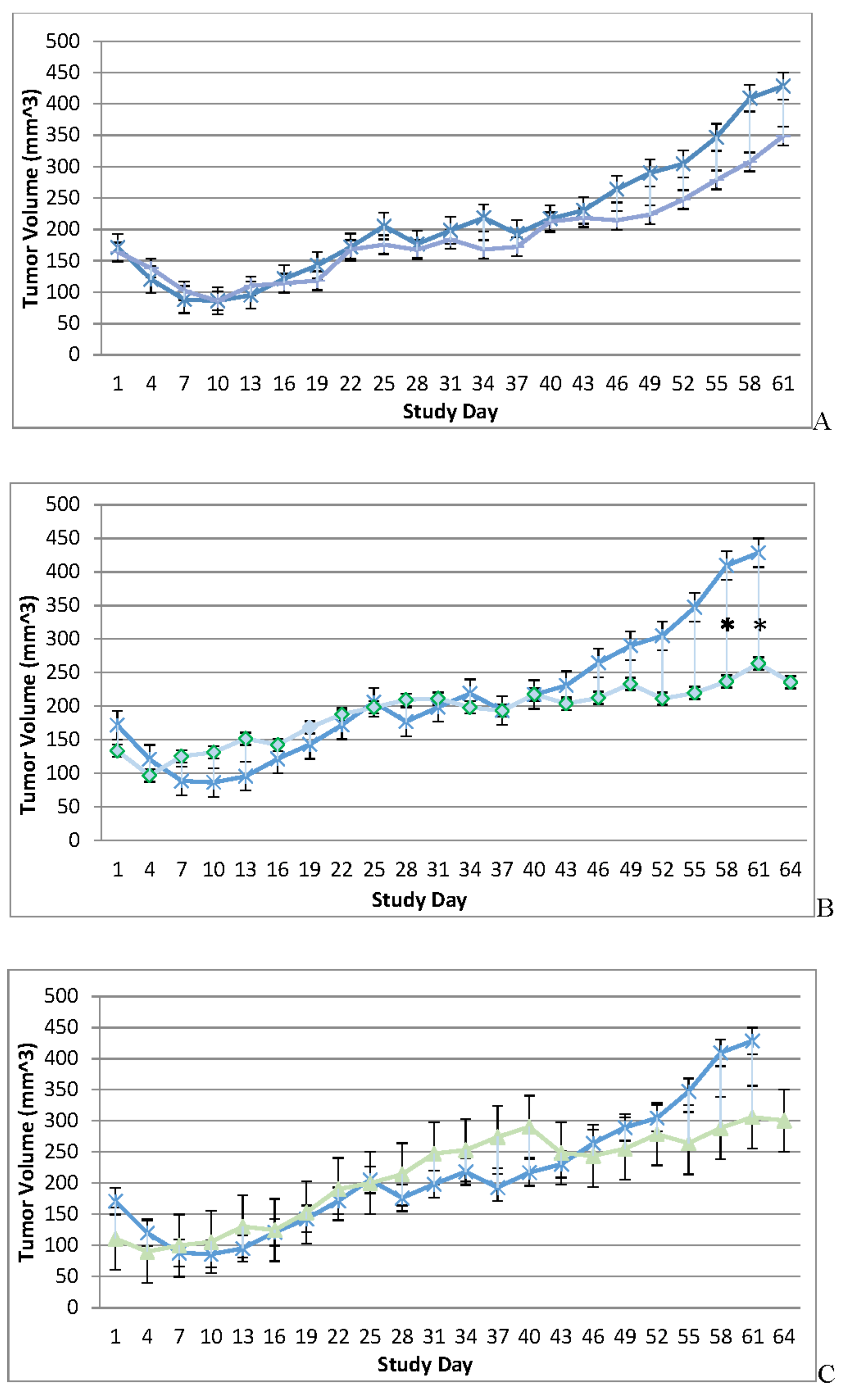

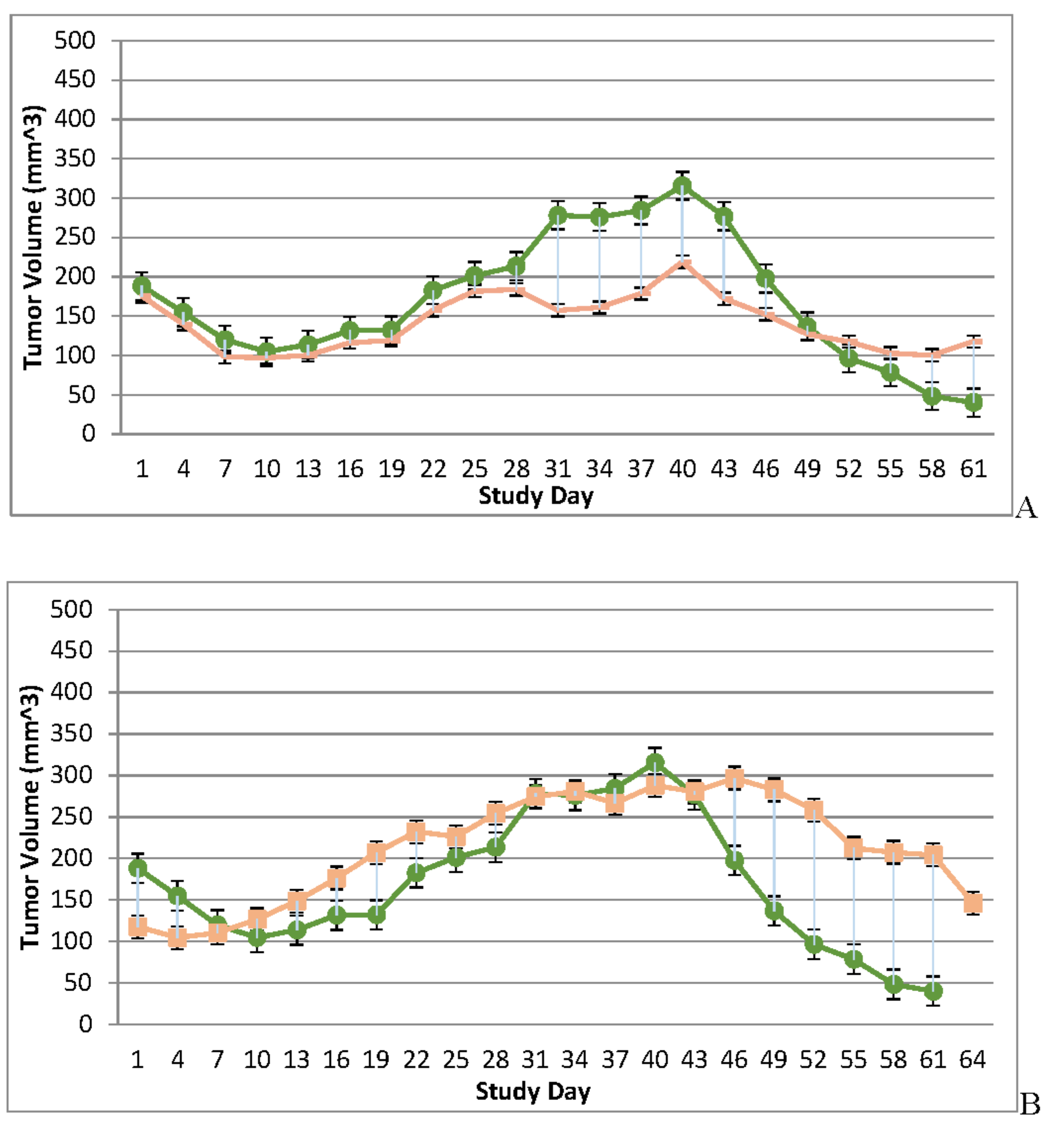

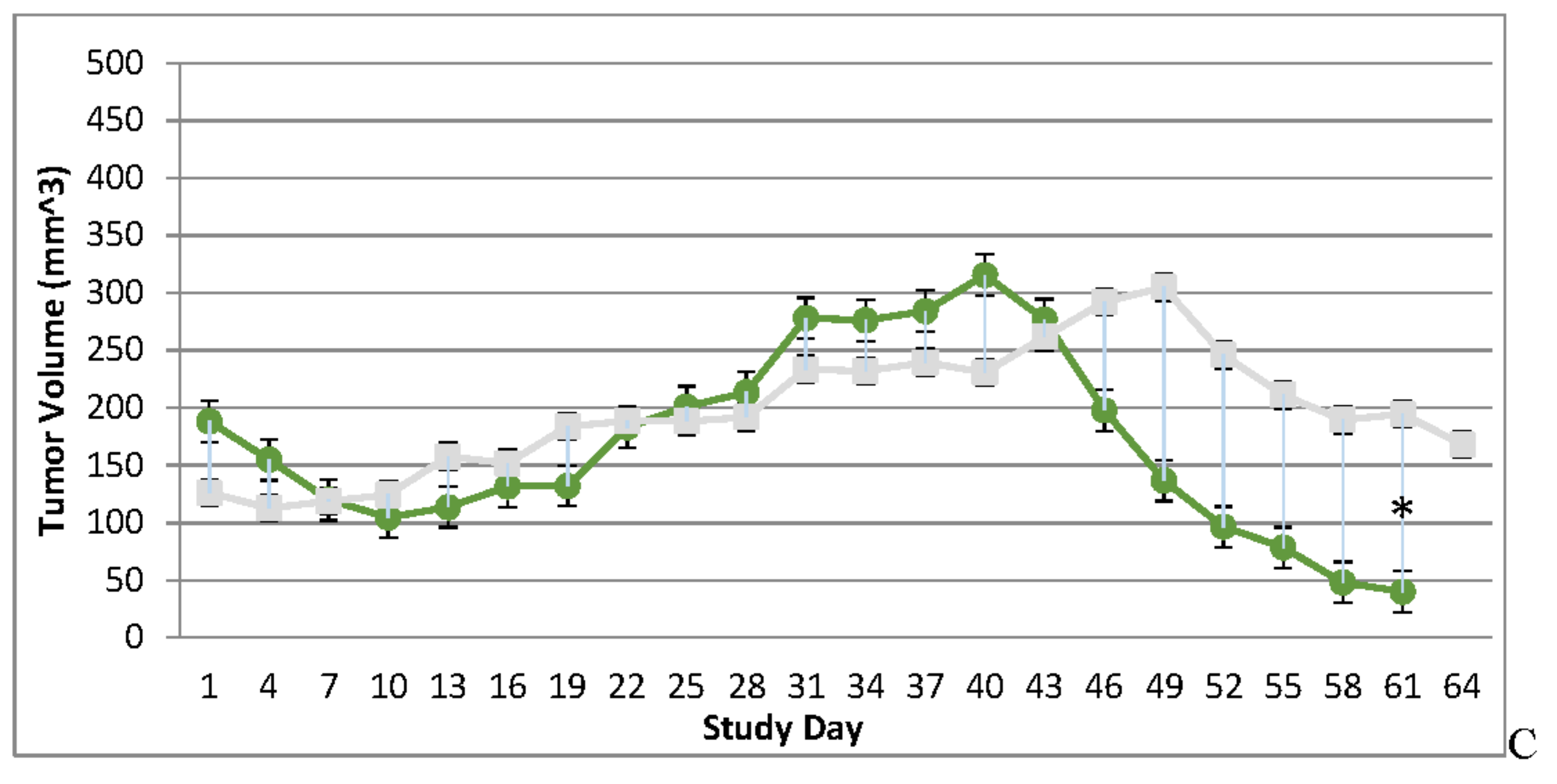

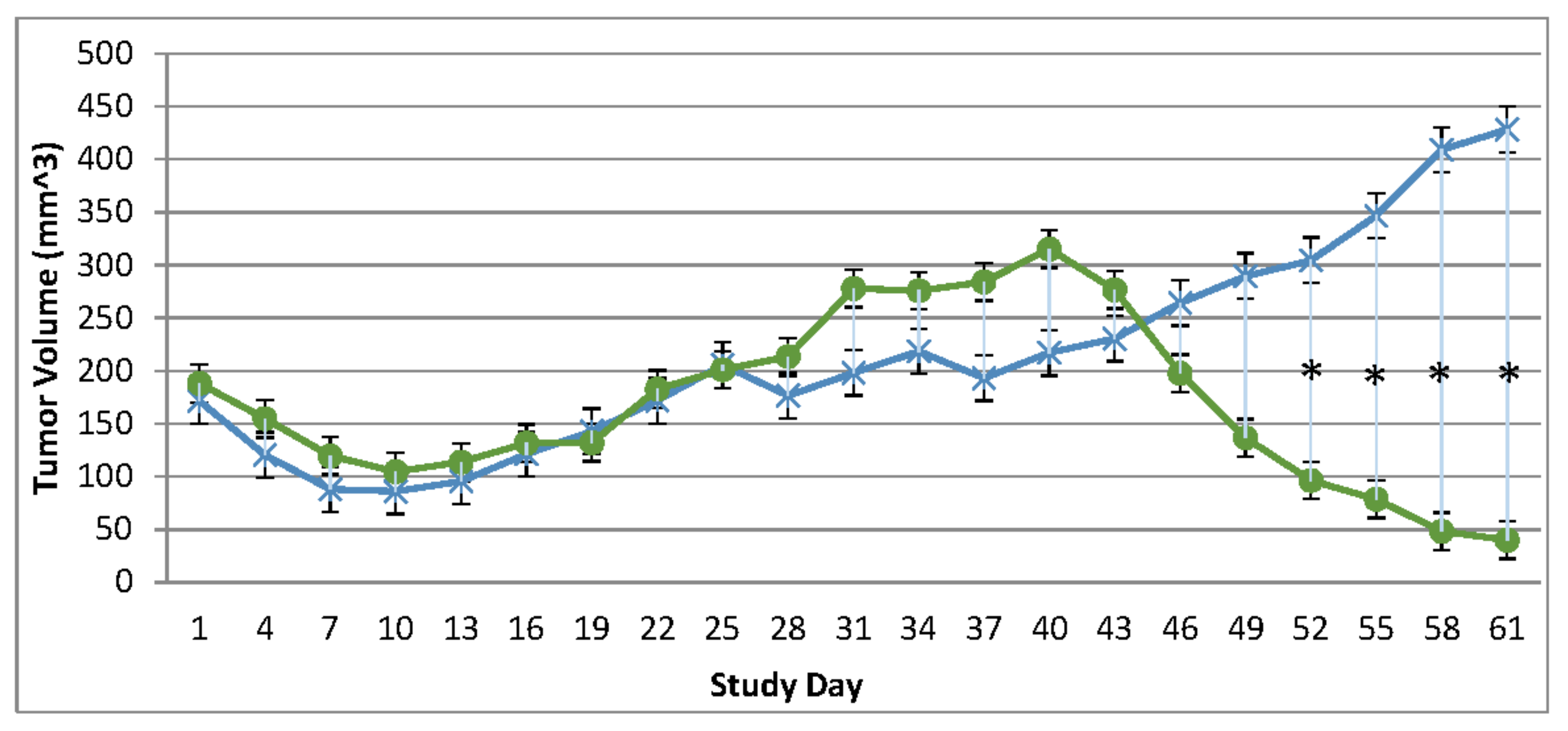

Treatment if BxPc-3 Xenografts with Tanapoxvirus Recombinants In Vivo

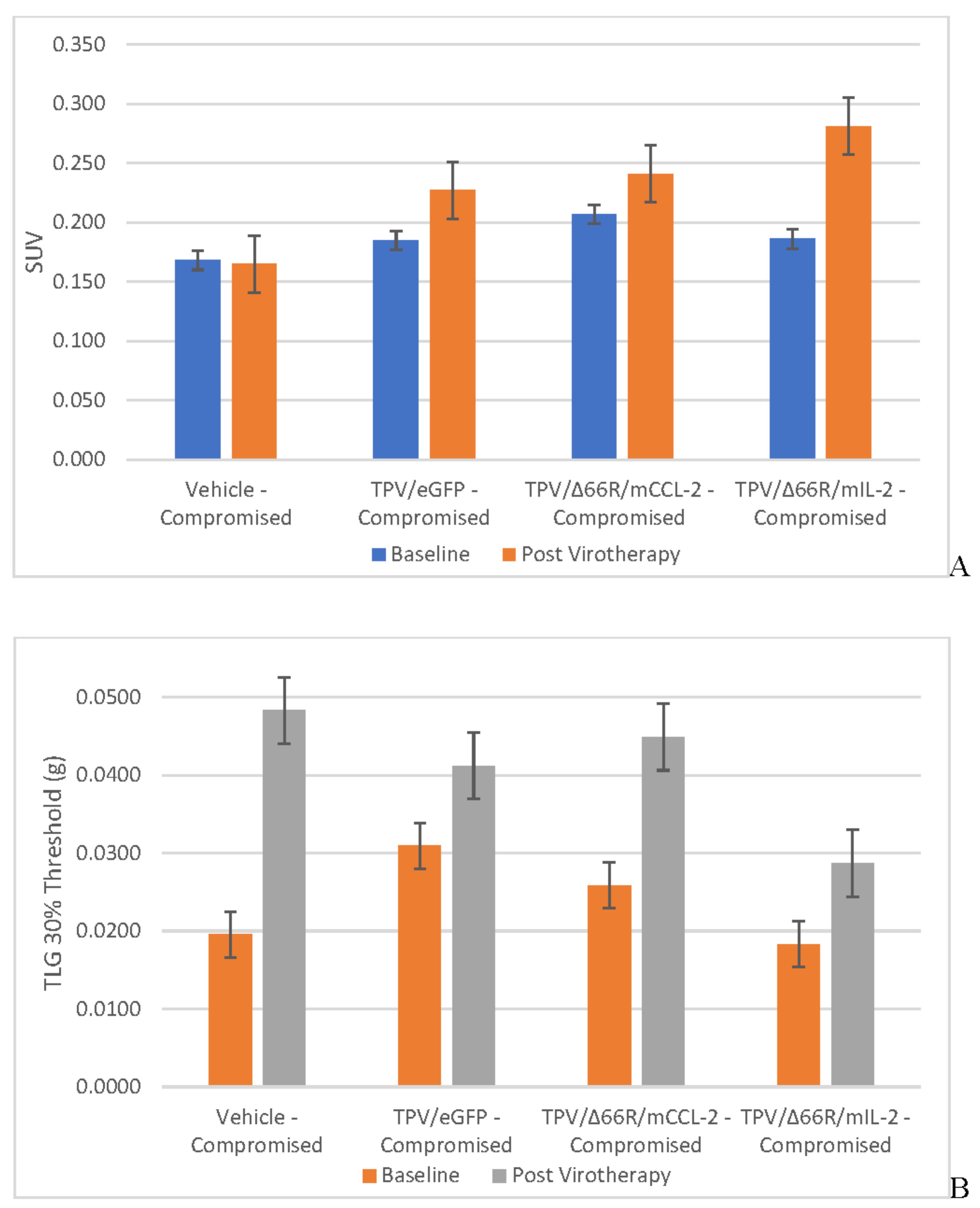

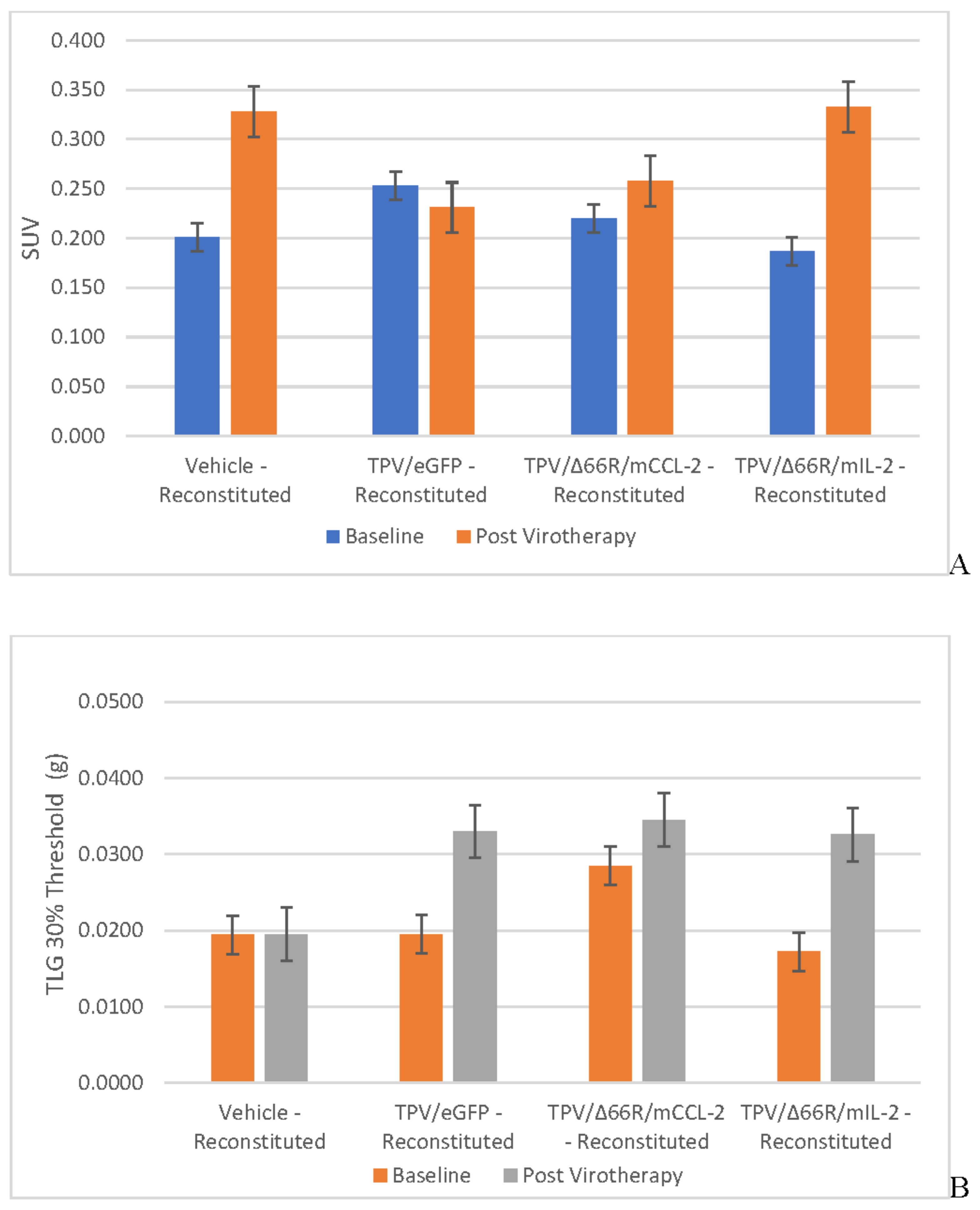

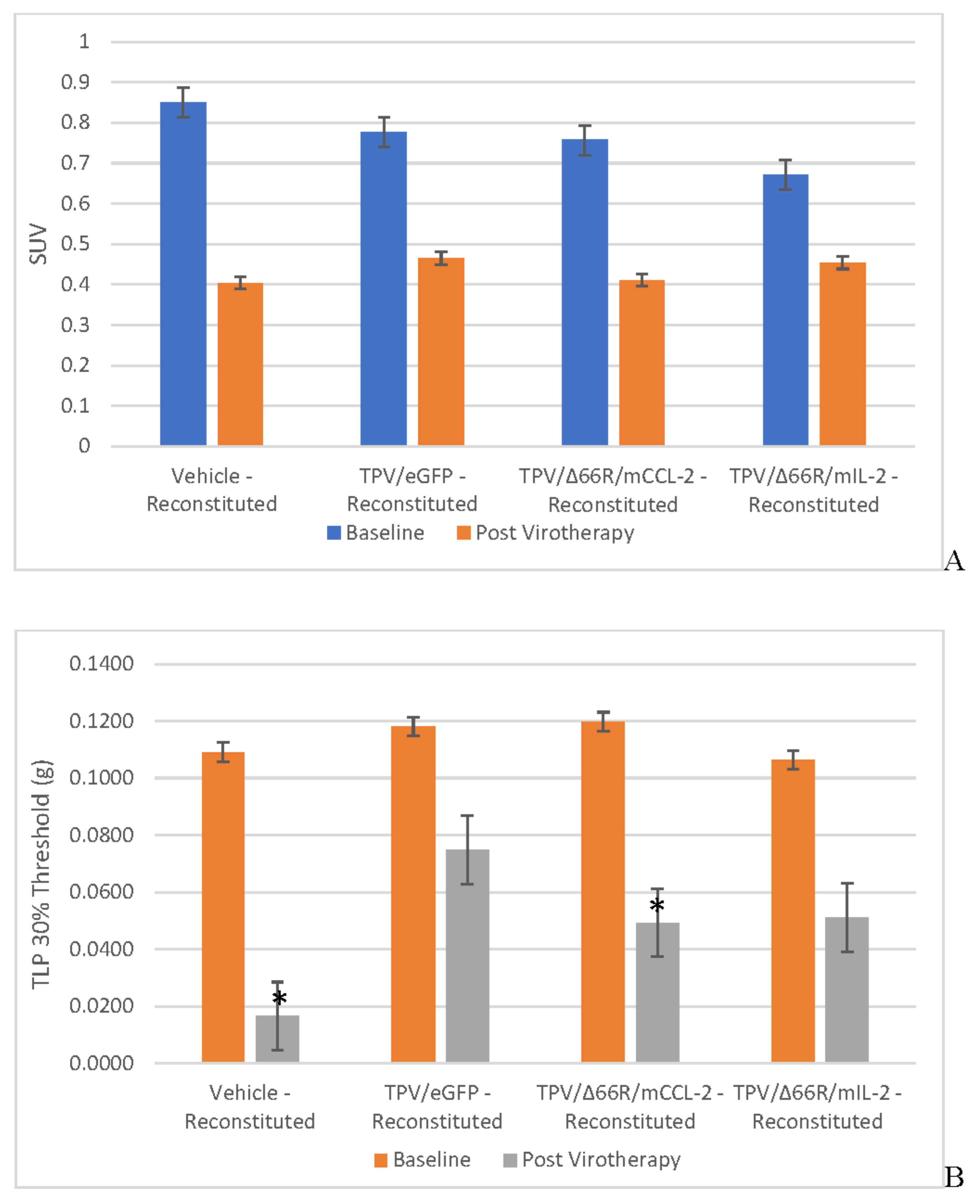

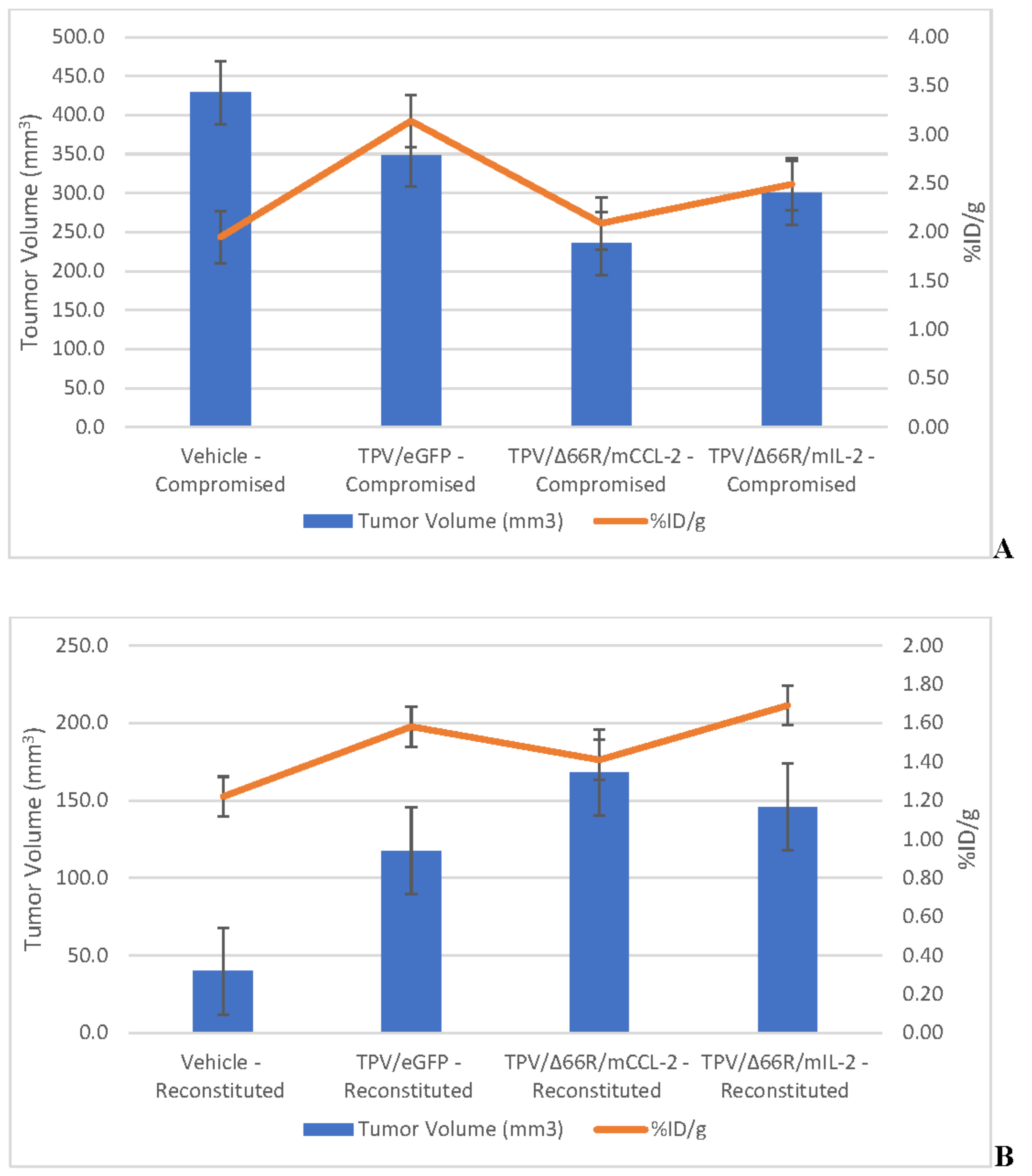

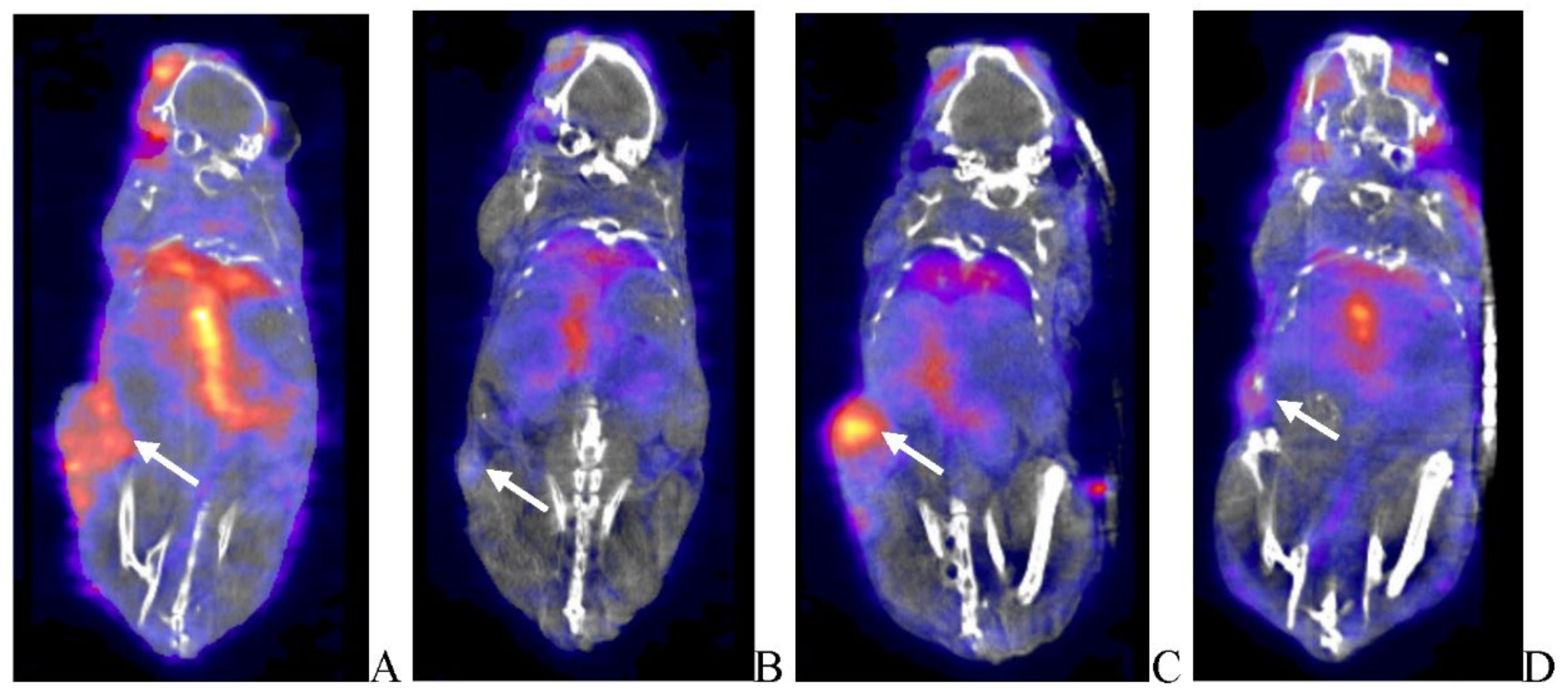

Tumor Metabolic Activity Assessment via [18F]-FDG PET/CT Imaging

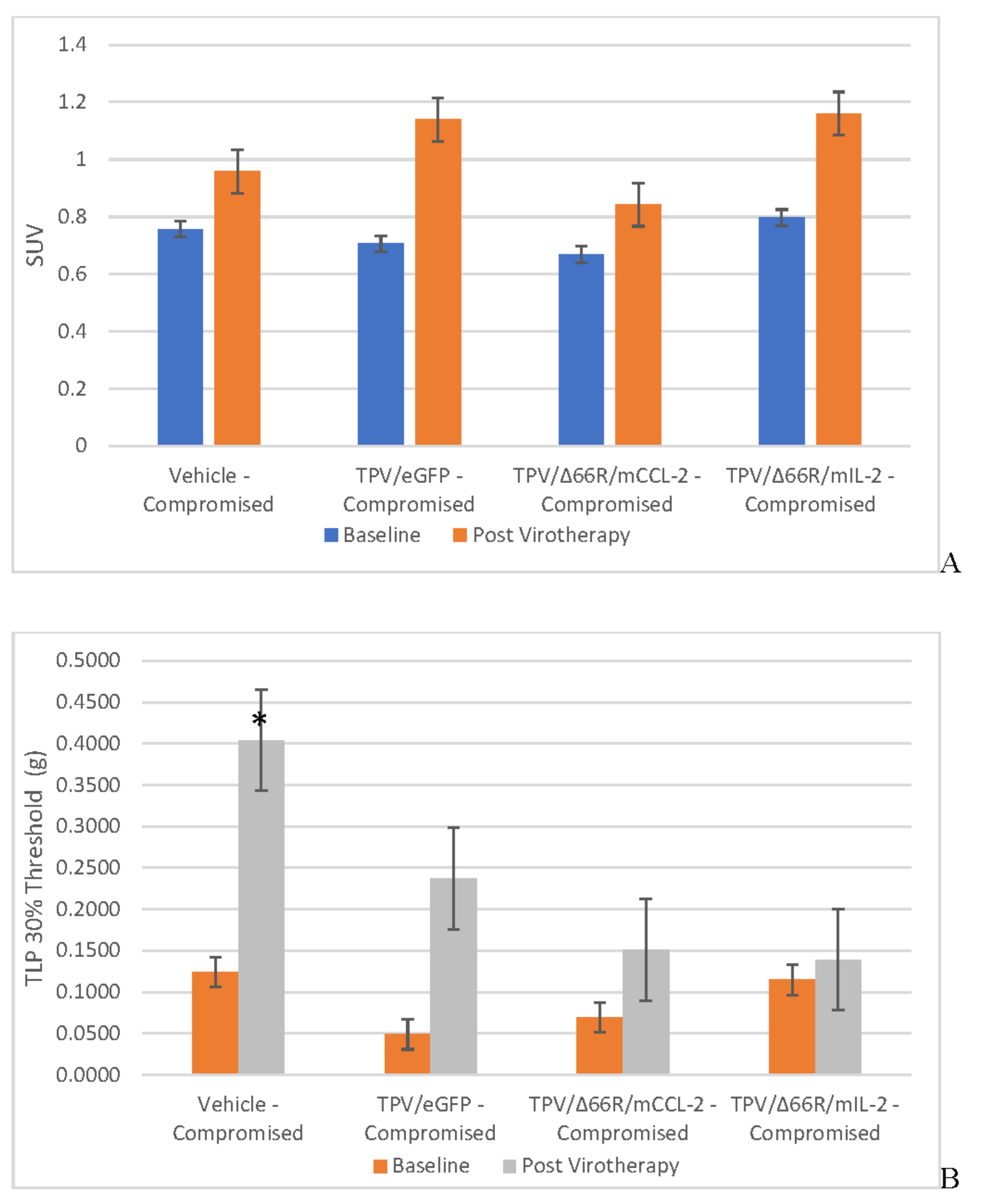

Tumor Cell Proliferation Assessment via [18F]-FLT PET/CT IMAGING

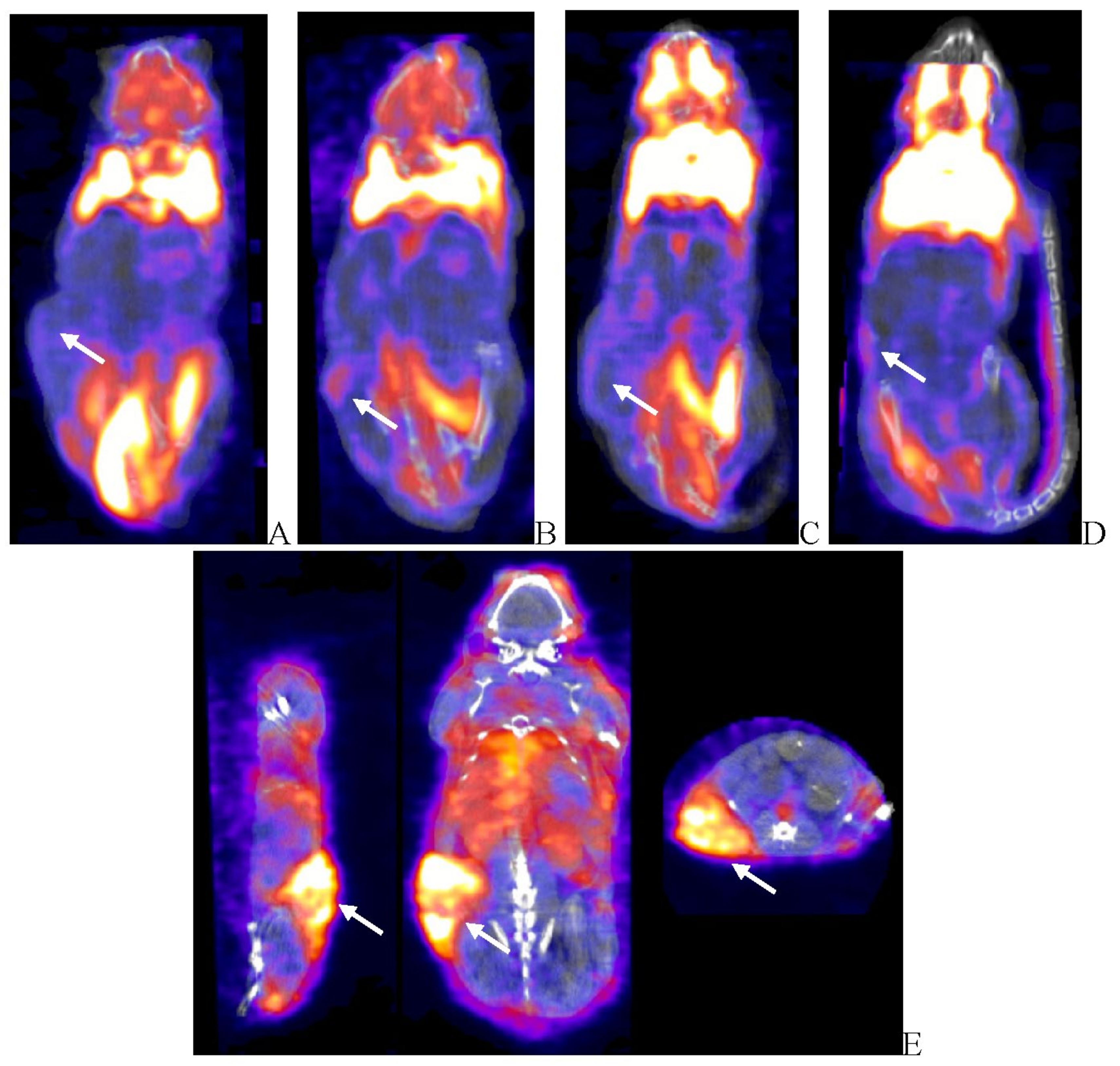

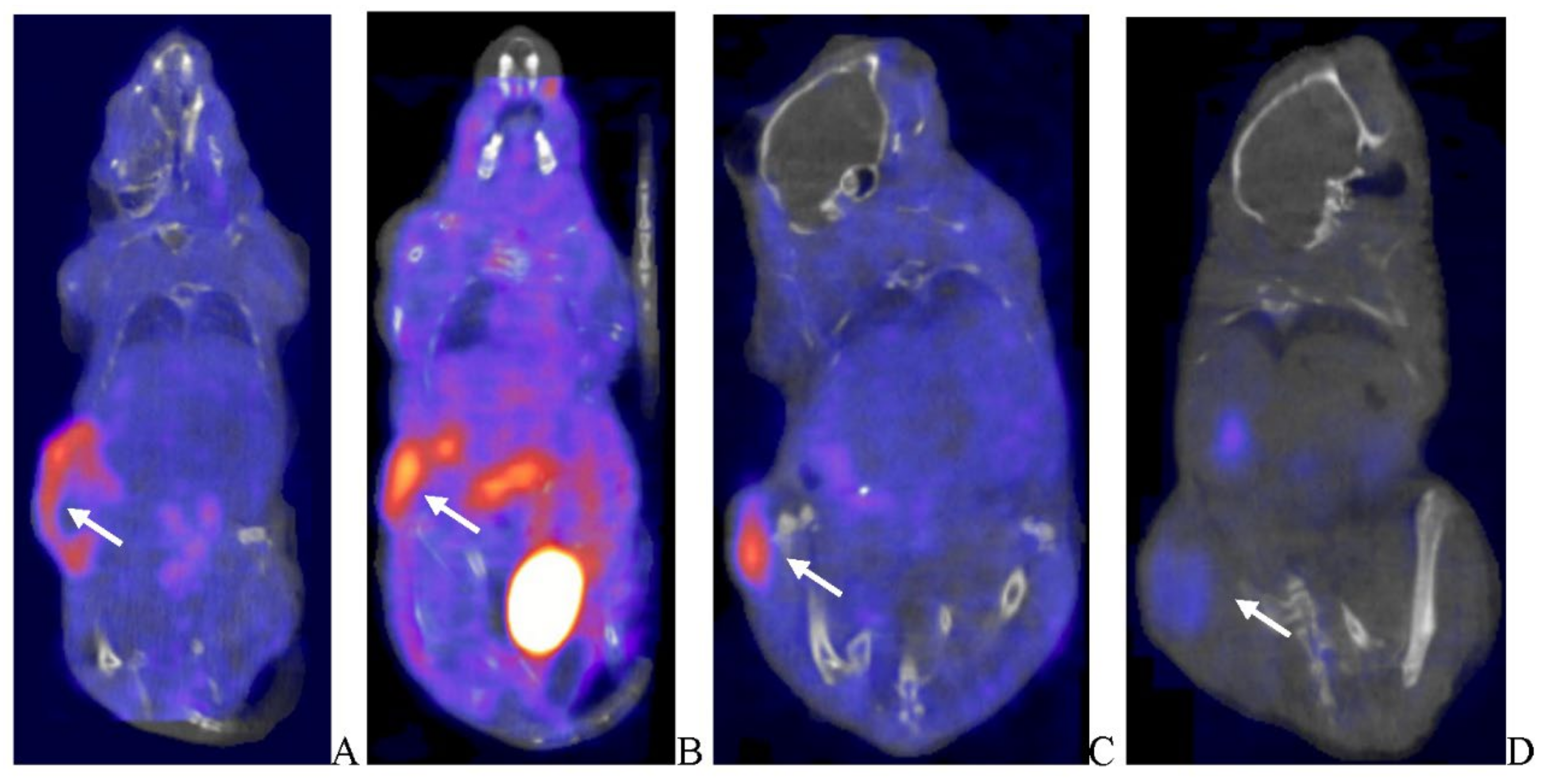

In Vivo Tumor TPV Transgene Expression Assessment via SPECT/CT Imaging

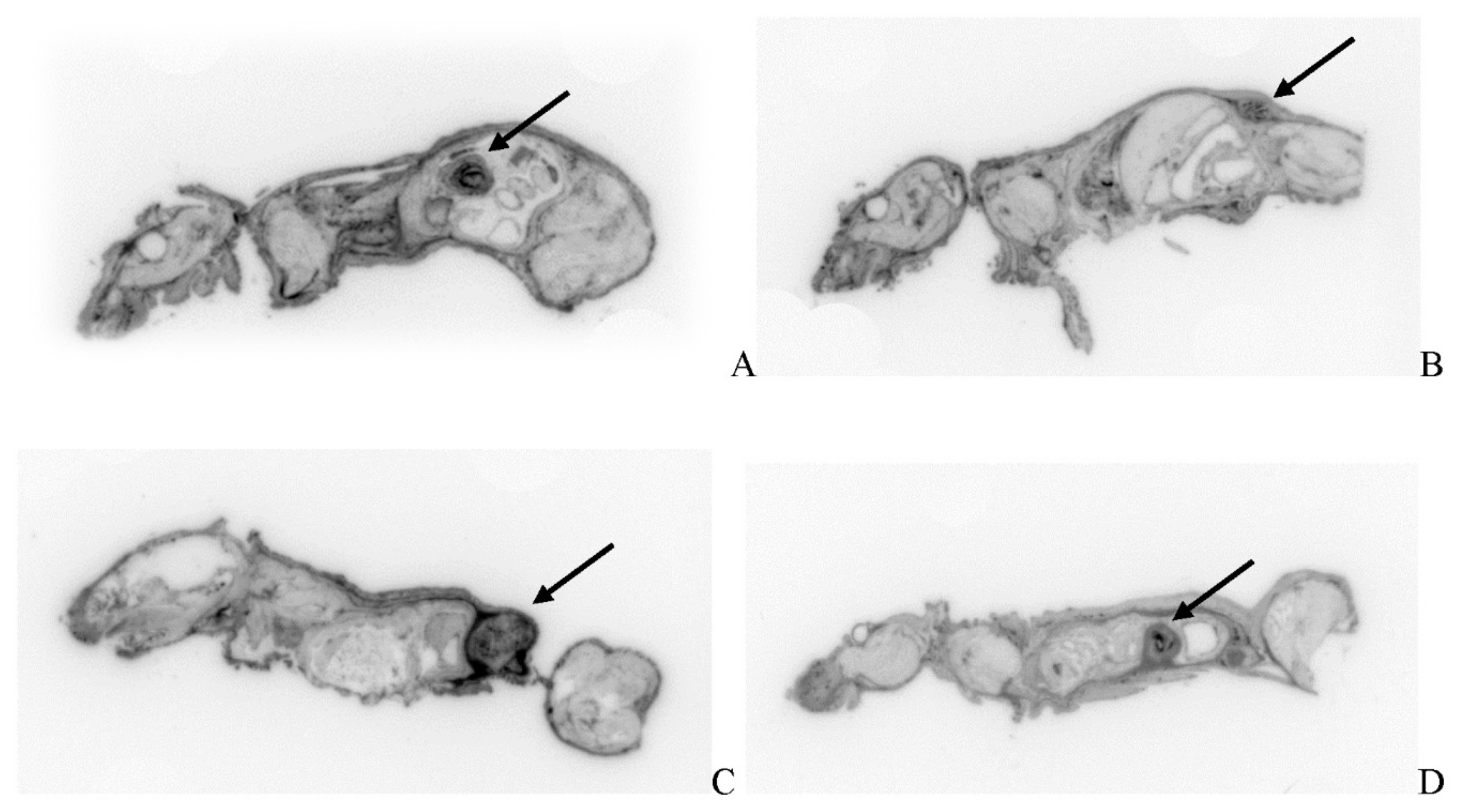

Ex VivotTumor TPV Transgene Expression Assessment via Quantitative Whole-Body Autoradiography (QWBA)

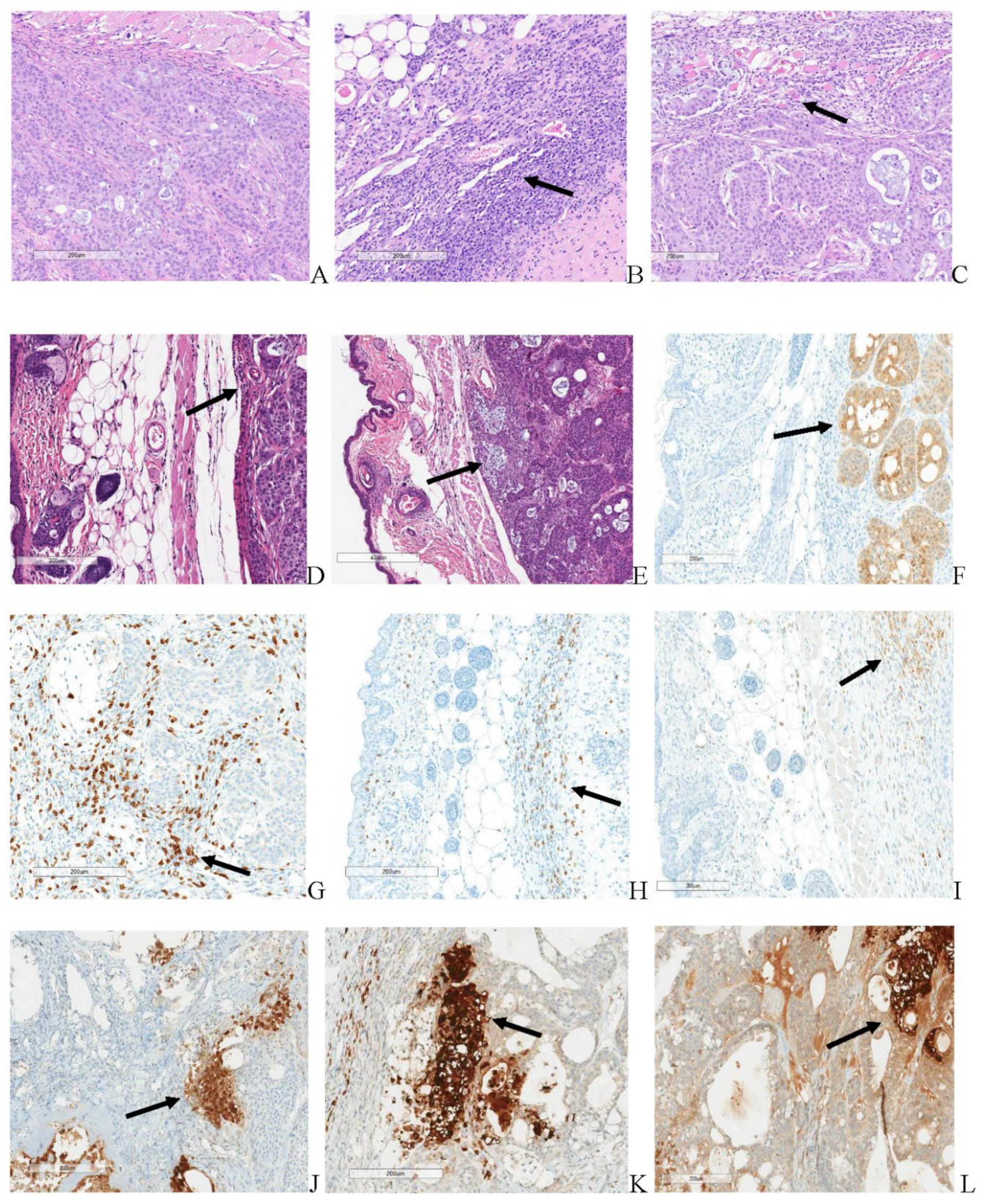

Biomarker Analysis and Pathology

Pathology

Discussion

Methods and Materials

Cells, Viruses and Reagents

Viral Replication Assessment via Phase Contrast and Florescent Microscopy

Viral Plaque Assay

Animal Model

In Vivo Study Design Summary

BxPc-3 Human PDAC Xenografts and Virotherapy

CD3+ T-Cell Isolation and Adoptive Transfer

[18F]-FDG and [18F]-FLT PET Imaging Agents

[125I]-anti GFP Antibody and [125I]-Anti-mCherry Antibody SPECT Imaging Agents

PET/CT Imaging

SPECT/CT Imaging

Quantitative Whole-Body Autoradiography (QWBA)

CD-3+ T-cell Biomarker Assay

Tissue Processing and Histopathological Assessment

Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Previdi, M.C.; Carotenuto, P.; Zito, D.; Pandolfo, R.; Braconi, C. Noncoding RNAs as Novel Biomarkers in Pancreatic Cancer: What Do We Know? Future Oncology 2017. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haeberle, L.; Esposito, I. Pathology of Pancreatic Cancer. Translational Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2019. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, D.P.; Hong, T.S.; Bardeesy, N. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2014. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahib, L.; Smith, B.D.; Aizenberg, R.; Rosenzweig, A.B.; Fleshman, J.M.; Matrisian, L.M. Projecting Cancer Incidence and Deaths to 2030: The Unexpected Burden of Thyroid, Liver, and Pancreas Cancers in the United States. Cancer Research 2014. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouanet, M.; Lebrin, M.; Gross, F.; Bournet, B.; Cordelier, P.; Buscail, L. Gene Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer: Specificity, Issues and Hopes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, A.; Herman, J.; Schulick, R.; Hruban, R.H.; Goggins, M. Pancreatic Cancer. In Proceedings of the The Lancet; 2011.

- Hruban, R.H.; Canto, M.I.; Goggins, M.; Schulick, R.; Klein, A.P. Update on Familial Pancreatic Cancer. Advances in Surgery 2010. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuigan, A.; Kelly, P.; Turkington, R.C.; Jones, C.; Coleman, H.G.; McCain, R.S. Pancreatic Cancer: A Review of Clinical Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Treatment and Outcomes. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2018. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Xu, J.W.; Cheng, Y.G.; Gao, J.Y.; Hu, S.Y.; Wang, L.; Zhan, H.X. Early Detection of Pancreatic Cancer: Where Are We Now and Where Are We Going? International Journal of Cancer 2017. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islami, F.; Goding Sauer, A.; Miller, K.D.; Siegel, R.L.; Fedewa, S.A.; Jacobs, E.J.; McCullough, M.L.; Patel, A.v.; Ma, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; et al. Proportion and Number of Cancer Cases and Deaths Attributable to Potentially Modifiable Risk Factors in the United States. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.-H.; Eibl, G. Obesity-Induced Adipose Tissue Inflammation as a Strong Promotional Factor for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cells 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.; Zhang, X.; Parsons, D.W.; Lin, J.C.H.; Leary, R.J.; Angenendt, P.; Mankoo, P.; Carter, H.; Kamiyama, H.; Jimeno, A.; et al. Core Signaling Pathways in Human Pancreatic Cancers Revealed by Global Genomic Analyses. Science 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozenblum, E.; Schutte, M.; Goggins, M.; Hahn, S.A.; Panzer, S.; Zahurak, M.; Goodman, S.N.; Sohn, T.A.; Hruban, R.H.; Yeo, C.J.; et al. Tumor-Suppressive Pathways in Pancreatic Carcinoma. Cancer Research 1997. [Google Scholar]

- van Heek, N.T.; Meeker, A.K.; Kern, S.E.; Yeo, C.J.; Lillemoe, K.D.; Cameron, J.L.; Offerhaus, G.J.A.; Hicks, J.L.; Wilentz, R.E.; Goggins, M.G.; et al. Telomere Shortening Is Nearly Universal in Pancreatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia. American Journal of Pathology 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.M.; Heaphy, C.M.; Shi, C.; Eo, S.H.; Cho, H.; Meeker, A.K.; Eshleman, J.R.; Hruban, R.H.; Goggins, M. Telomeres Are Shortened in Acinar-to-Ductal Metaplasia Lesions Associated with Pancreatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia but Not in Isolated Acinar-to-Ductal Metaplasias. Modern Pathology 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hruban, R.H.; Goggins, M.; Parsons, J.; Kern, S.E. Progression Model for Pancreatic Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 2000.

- Carter, H.; Samayoa, J.; Hruban, R.H.; Karchin, R. Prioritization of Driver Mutations in Pancreatic Cancer Using Cancer-Specific High-Throughput Annotation of Somatic Mutations (CHASM). Cancer Biology and Therapy 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omura, N.; Goggins, M. Epigenetics and Epigenetic Alterations in Pancreatic Cancer. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology 2009.

- M., S.; R.H., H.; J., G.; R., M.; W., H.; S.K., R.; C.A., M.; S.A., H.; I., S.-W.; W., S.; et al. Abrogation of the Rb/P16 Tumor-Suppressive Pathway in Virtually All Pancreatic Carcinomas. Cancer Research 1997.

- Matsubayashi, H.; Canto, M.; Sato, N.; Klein, A.; Abe, T.; Yamashita, K.; Yeo, C.J.; Kalloo, A.; Hruban, R.; Goggins, M. DNA Methylation Alterations in the Pancreatic Juice of Patients with Suspected Pancreatic Disease. Cancer Research 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, N.; Matsubayashi, H.; Abe, T.; Fukushima, N.; Goggins, M. Epigenetic Down-Regulation of CDKN1C/P57KIP2 in Pancreatic Ductal Neoplasms Identified by Gene Expression Profiling. Clinical Cancer Research 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, N.; Fukushima, N.; Hruban, R.H.; Goggins, M. CpG Island Methylation Profile of Pancreatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia. Modern Pathology 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, N.; Fukushima, N.; Maitra, A.; Matsubayashi, H.; Yeo, C.J.; Cameron, J.L.; Hruban, R.H.; Goggins, M. Discovery of Novel Targets for Aberrant Methylation in Pancreatic Carcinoma Using High-Throughput Microarrays. Cancer Research 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, N.; Fukushima, N.; Chang, R.; Matsubayashi, H.; Goggins, M. Differential and Epigenetic Gene Expression Profiling Identifies Frequent Disruption of the RELN Pathway in Pancreatic Cancers. Gastroenterology 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, N.; Fukushima, N.; Maehara, N.; Matsubayashi, H.; Koopmann, J.; Su, G.H.; Hruban, R.H.; Goggins, M. SPARC/Osteonectin Is a Frequent Target for Aberrant Methylation in Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma and a Mediator of Tumor-Stromal Interactions. Oncogene 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, N.; Maitra, A.; Fukushima, N.; van Heek, N.T.; Matsubayashi, H.; Iacobuzio-Donahue, C.A.; Rosty, C.; Goggins, M. Frequent Hypomethylation of Multiple Genes Overexpressed in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Research 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Parsi, M.A.; Li, A.; Li, C.P.; Goggins, M. DNA Methylation Alterations In Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Brush Samples of Patients With Suspected Pancreaticobiliary Disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, A.; Ducourouble, M.; van Seuningen, I. Epigenetic Regulation of the Human Mucin Gene MUC4 in Epithelial Cancer Cell Lines Involves Both DNA Methylation and Histone Modifications Mediated by DNA Methyltransferases and Histone Deacetylases. The FASEB Journal 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheufele, F.; Hartmann, D.; Friess, H. Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer—Neoadjuvant Treatment in Borderline Resectable/Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Translational Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2019. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.Y.; Yang, F.; Jin, C.; Fu, D.L. Utility of PET/CT in Diagnosis, Staging, Assessment of Resectability and Metabolic Response of Pancreatic Cancer. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2014, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstantinidis, I.T.; Warshaw, A.L.; Allen, J.N.; Blaszkowsky, L.S.; del Castillo, C.F.; Deshpande, V.; Hong, T.S.; Kwak, E.L.; Lauwers, G.Y.; Ryan, D.P.; et al. Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Cancer: Need for Standardization and Methods for Optimal Clinical Trial Design. Ann Surg Oncol 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springfeld, C.; Jäger, D.; Büchler, M.W.; Strobel, O.; Hackert, T.; Palmer, D.H.; Neoptolemos, J.P. Chemotherapy for Pancreatic Cancer. Presse Medicale 2019. [CrossRef]

- Klaiber, U.; Hackert, T.; Neoptolemos, J.P. Adjuvant Treatment for Pancreatic Cancer. Translational Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2019. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Amanam, I.; Chung, V. Current and Future Therapies for Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Journal of Surgical Oncology 2017. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillen, S.; Schuster, T.; Büschenfelde, C.M.; Friess, H.; Kleeff, J. Preoperative/Neoadjuvant Therapy in Pancreatic Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Response and Resection Percentages. PLoS Medicine 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, J.; Combs, S.E.; Springfeld, C.; Hartwig, W.; Hackert, T.; Büchler, M.W. Advanced-Stage Pancreatic Cancer: Therapy Options. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2013. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conroy, T.; Desseigne, F.; Ychou, M.; Bouché, O.; Guimbaud, R.; Bécouarn, Y.; Adenis, A.; Raoul, J.L.; Gourgou-Bourgade, S.; de La Fouchardière, C.; et al. FOLFIRINOX versus Gemcitabine for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Hoff, D.D.; Ervin, T.; Arena, F.P.; Chiorean, E.G.; Infante, J.; Moore, M.; Seay, T.; Tjulandin, S.A.; Ma, W.W.; Saleh, M.N.; et al. Increased Survival in Pancreatic Cancer with Nab-Paclitaxel plus Gemcitabine. New England Journal of Medicine 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falasca, M.; Kim, M.; Casari, I. Pancreatic Cancer: Current Research and Future Directions. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta—Reviews on Cancer 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahal, A.; Musher, B. Oncolytic Viral Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer. Journal of Surgical Oncology 2017. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaRocca, C.J.; Warner, S.G. A New Role for Vitamin D: The Enhancement of Oncolytic Viral Therapy in Pancreatic Cancer. Biomedicines 2018. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, S.J.; Peng, K.W.; Bell, J.C. Oncolytic Virotherapy. Nature Biotechnology 2012. [CrossRef]

- Vähä-Koskela, M.J.V.; Heikkilä, J.E.; Hinkkanen, A.E. Oncolytic Viruses in Cancer Therapy. Cancer Letters 2007. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, J.; McFadden, G. Viruses for Tumor Therapy. Cell Host and Microbe 2014. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichty, B.D.; Breitbach, C.J.; Stojdl, D.F.; Bell, J.C. Going Viral with Cancer Immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Cancer 2014. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, H.L.; Kohlhapp, F.J.; Zloza, A. Oncolytic Viruses: A New Class of Immunotherapy Drugs. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2015.

- Eissa, I.R.; Naoe, Y.; Bustos-Villalobos, I.; Ichinose, T.; Tanaka, M.; Zhiwen, W.; Mukoyama, N.; Morimoto, T.; Miyajima, N.; Hitoki, H.; et al. Genomic Signature of the Natural Oncolytic Herpes Simplex Virus HF10 and Its Therapeutic Role in Preclinical and Clinical Trials. Frontiers in Oncology 2017. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bretscher, C.; Marchini, A. H-1 Parvovirus as a Cancer-Killing Agent: Past, Present, and Future. Viruses 2019. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, M.J. Targets and Mechanisms for the Regulation of Translation in Malignant Transformation. Oncogene 2004. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, M. Oncorine, the World First Oncolytic Virus Medicine and Its Update in China. Current Cancer Drug Targets 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoda, R.T.; Nagalo, B.M.; Borad, M.J. Oncolytic Adenoviruses in Gastrointestinal Cancers. Biomedicines 2018. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freytag, S.O.; Barton, K.N.; Brown, S.L.; Narra, V.; Zhang, Y.; Tyson, D.; Nall, C.; Lu, M.; Ajlouni, M.; Movsas, B.; et al. Replication-Competent Adenovirus-Mediated Suicide Gene Therapy with Radiation in a Preclinical Model of Pancreatic Cancer. Molecular Therapy 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eissa, I.R.; Bustos-Villalobos, I.; Ichinose, T.; Matsumura, S.; Naoe, Y.; Miyajima, N.; Morimoto, D.; Mukoyama, N.; Zhiwen, W.; Tanaka, M.; et al. The Current Status and Future Prospects of Oncolytic Viruses in Clinical Trials against Melanoma, Glioma, Pancreatic, and Breast Cancers. Cancers 2018. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoda, R.; Nagalo, B.M.; Arora, M.; Egan, J.B.; Bogenberger, J.M.; DeLeon, T.T.; Zhou, Y.; Ahn, D.H.; Borad, M.J. Oncolytic Virotherapy in Upper Gastrointestinal Tract Cancers. Oncolytic Virotherapy 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andtbacka, R.H.I.; Kaufman, H.L.; Collichio, F.; Amatruda, T.; Senzer, N.; Chesney, J.; Delman, K.A.; Spitler, L.E.; Puzanov, I.; Agarwala, S.S.; et al. Talimogene Laherparepvec Improves Durable Response Rate in Patients with Advanced Melanoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, K.J.; Senzer, N.N.; Binmoeller, K.; Goldsweig, H.; Coffin, R. Phase I Dose-Escalation Study of Talimogene Laherparepvec (T-VEC) for Advanced Pancreatic Cancer (Ca). Journal of Clinical Oncology 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayral, M.; Lulka, H.; Hanoun, N.; Biollay, C.; Sèlves, J.; Vignolle-Vidoni, A.; Berthommé, H.; Trempat, P.; Epstein, A.L.; Buscail, L.; et al. Targeted Oncolytic Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Eradicates Experimental Pancreatic Tumors. Human Gene Therapy 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- TOOLAN, H.W. A Virus Associated with Transplantable Human Tumors. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Toolan, H.W.; Ledinko, N. Inhibition by H-1 Virus of the Incidence of Tumors Produced by Adenovirus 12 in Hamsters. Virology 1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, K.L.; Mancias, J.D.; Kimmelman, A.C.; Der, C.J. KRAS: Feeding Pancreatic Cancer Proliferation. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2014. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noonan, A.M.; Farren, M.R.; Geyer, S.M.; Huang, Y.; Tahiri, S.; Ahn, D.; Mikhail, S.; Ciombor, K.K.; Pant, S.; Aparo, S.; et al. Randomized Phase 2 Trial of the Oncolytic Virus Pelareorep (Reolysin) in Upfront Treatment of Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Molecular Therapy 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, D.H.; Bekaii-Saab, T. The Continued Promise and Many Disappointments of Oncolytic Virotherapy in Gastrointestinal Malignancies. Biomedicines 2017. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, G.L.; Moss, B. Infectious Poxvirus Vectors Have Capacity for at Least 25 000 Base Pairs of Foreign DNA. Gene 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.A.; Galanis, C.; Woo, Y.; Chen, N.; Zhang, Q.; Fong, Y.; Szalay, A.A. Regression of Human Pancreatic Tumor Xenografts in Mice after a Single Systemic Injection of Recombinant Vaccinia Virus GLV-1h68. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, M.H.; Liu, S.L.; Chen, N.G.; Zhang, T.P.; You, L.; Q. Zhang, F.; Chou, T.C.; Szalay, A.A.; Fong, Y.; Zhao, Y.P. Oncolytic Vaccinia Virus in Combination with Radiation Shows Synergistic Antitumor Efficacy in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Letters 2014. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- al Yaghchi, C.; Zhang, Z.; Alusi, G.; Lemoine, N.R.; Wang, Y. Vaccinia Virus, a Promising New Therapeutic Agent for Pancreatic Cancer. Immunotherapy 2015. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downs-Canner, S.; Guo, Z.S.; Ravindranathan, R.; Breitbach, C.J.; O’Malley, M.E.; Jones, H.L.; Moon, A.; McCart, J.A.; Shuai, Y.; Zeh, H.J.; et al. Phase 1 Study of Intravenous Oncolytic Poxvirus (VvDD) in Patients with Advanced Solid Cancers. Molecular Therapy 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, W.M.; McFadden, G. Oncolytic Poxviruses. Annual Review of Virology 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monroe, B.P.; Nakazawa, Y.J.; Reynolds, M.G.; Carroll, D.S. Estimating the Geographic Distribution of Human Tanapox and Potential Reservoirs Using Ecological Niche Modeling. International Journal of Health Geographics 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downie, A.W.; Taylor-Robinson, C.H.; Caunt, A.E.; Nelson, G.S.; Manson-Bahr, P.E.C.; Matthews, T.C.H. Tanapox: A New Disease Caused by a Pox Virus. British Medical Journal 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downie, A.W.; Taylor-Robinson, C.H.; Caunt, A.E.; Nelson, G.S.; Manson-Bahr, P.E.C.; Matthews, T.C.H. Tanapox: A New Disease Caused by a Pox Virus. British Medical Journal 1971, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunetti, C.R.; Amano, H.; Ueda, Y.; Qin, J.; Miyamura, T.; Suzuki, T.; Li, X.; Barrett, J.W.; McFadden, G. Complete Genomic Sequence and Comparative Analysis Ofthe Tumorigenic Poxvirus Yaba Monkey TumorVirus. Journal of Virology 2003, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Essani, K.; Smith, G.L. The Genome Sequence of Yaba-like Disease Virus, a Yatapoxvirus. Virology 2001, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broët, P.; Romain, S.; Daver, A.; Ricolleau, G.; Quillien, V.; Rallet, A.; Asselain, B.; Martin, P.M.; Spyratos, F. Thymidine Kinase as a Proliferative Marker: Clinical Relevance in 1,692 Primary Breast Cancer Patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2001, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alegre, M.M.; Robison, R.A.; O’Neill, K.L. Thymidine Kinase 1 Upregulation Is an Early Event in Breast Tumor Formation. Journal of Oncology 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, B.H.; Hwang, T.; Liu, T.C.; Sze, D.Y.; Kim, J.S.; Kwon, H.C.; Oh, S.Y.; Han, S.Y.; Yoon, J.H.; Hong, S.H.; et al. Use of a Targeted Oncolytic Poxvirus, JX-594, in Patients with Refractory Primary or Metastatic Liver Cancer: A Phase I Trial. The Lancet Oncology 2008, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hengstschläger, M.; Knöfler, M.; Müllner, E.W.; Ogris, E.; Wintersberger, E.; Wawra, E. Different Regulation of Thymidine Kinase during the Cell Cycle of Normal versus DNA Tumor Virus-Transformed Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1994, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martuza, R.L.; Malick, A.; Markert, J.M.; Ruffner, K.L.; Coen, D.M. Experimental Therapy of Human Glioma by Means of a Genetically Engineered Virus Mutant. Science 1991, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, B.; Cripe, T.; Chiocca, E. “Buy One Get One Free”: Armed Viruses for the Treatment of Cancer Cells and Their Microenvironment. Current Gene Therapy 2009, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattaneo, R.; Miest, T.; Shashkova, E.v.; Barry, M.A. Reprogrammed Viruses as Cancer Therapeutics: Targeted, Armed and Shielded. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2008, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrad, S.J.; El-Aswad, M.; Kurban, E.; Jeng, D.; Tripp, B.C.; Nutting, C.; Eversole, R.; Mackenzie, C.; Essani, K. Oncolytic Tanapoxvirus Expressing FliC Causes Regression of Human Colorectal Cancer Xenografts in Nude Mice. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Cancer Research 2015, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Suryawanshi, Y.R.; Kordish, D.H.; Woyczesczyk, H.M.; Jeng, D.; Essani, K. Tanapoxvirus Lacking a Neuregulin-like Gene Regresses Human Melanoma Tumors in Nude Mice. Virus Genes 2017, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suryawanashi, Y.R.; Zhang, T.; Woyczesczyk, H.M.; Christie, J.; Byers, E.; Kohler, S.; Eversole, R.; Mackenzie, C.; Essani, K. T-Independent Response Mediated by Oncolytic Tanapoxvirus Recombinants Expressing Interleukin-2 and Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 Suppresses Human Triple Negative Breast Tumors. Medical Oncology 2017, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, I.; Rollins, B.J. CCL2 (Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1) and Cancer. Seminars in Cancer Biology 2004, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.L.; Warren, M.K.; Rose, W.L.; Gong, W.; Wang, J.M. Human Recombinant Monocyte Chemotactic Protein and Other C-c Chemokines Bind and Induce Directional Migration of Dendritic Cells in Vitro. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 1996, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collington, S.J.; Hallgren, J.; Pease, J.E.; Jones, T.G.; Rollins, B.J.; Westwick, J.; Austen, K.F.; Williams, T.J.; Gurish, M.F.; Weller, C.L. The Role of the CCL2/CCR2 Axis in Mouse Mast Cell Migration In Vitro and In Vivo. The Journal of Immunology 2010, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, M.W.; Roth, S.J.; Luther, E.; Rose, S.S.; Springer, T.A. Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein 1 Acts as a T-Lymphocyte Chemoattractant. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1994, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.Y.; Yuzhalin, A.E.; Gordon-Weeks, A.N.; Muschel, R.J. Targeting the CCL2-CCR2 Signaling Axis in Cancer Metastasis. Oncotarget 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, J.N.; Meleth, S.; Hughes, K.B.; Gillespie, G.Y.; Whitley, R.J.; Markert, J.M. Enhanced Inhibition of Syngeneic Murine Tumors by Combinatorial Therapy with Genetically Engineered HSV-1 Expressing CCL2 and IL-12. Cancer Gene Therapy 2005, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monti, P.; Leone, B.E.; Marchesi, F.; Balzano, G.; Zerbi, A.; Scaltrini, F.; Pasquali, C.; Calori, G.; Pessi, F.; Sperti, C.; et al. The CC Chemokine MCP-1/CCL2 in Pancreatic Cancer Progression: Regulation of Expression and Potential Mechanisms of Antimalignant Activity. Cancer Research 2003, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Henney, C.S.; Kuribayashi, K.; Kern, D.E.; Gillis, S. Interleukin-2 Augments Natural Killer Cell Activity. Nature 1981, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, W.; Lin, J.X.; Leonard, W.J. IL-2 Family Cytokines: New Insights into the Complex Roles of IL-2 as a Broad Regulator of T Helper Cell Differentiation. Current Opinion in Immunology 2011, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vacchelli, E.; Aranda, F.; Obrist, F.; Eggermont, A.; Galon, J.; Cremer, I.; Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L. Trial Watch: Immunostimulatory Cytokines in Cancer Therapy. OncoImmunology 2014, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Suryawanshi, Y.R.; Szymczyna, B.R.; Essani, K. Neutralization of Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Potentially Enhances Oncolytic Efficacy of Tanapox Virus for Melanoma Therapy. Medical Oncology 2017, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheers, C.; Waller, R. Activated Macrophages in Congenitally Athymic “nude” Mice and in Lethally Irradiated Mice. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 1975, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, A.; Yingjun, S. Mouse Xenograft Models vs GEM Models for Human Cancer Therapeutics. DMM Disease Models and Mechanisms 2008, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essani, K.; Dugre, R.; Dales, S. Biogenesis of Vaccinia: Involvement of Spicules of the Envelope during Virion Assembly Examined by Means of Conditional Lethal Mutants and Serology. Virology 1982, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, S.J.; Eisenbarth, J.A.; Wagner-Utermann, U.; Mier, W.; Henze, M.; Pritzkow, H.; Haberkorn, U.; Eisenhut, M. A New Precursor for the Radiosynthesis of [18F]FLT. Nuclear Medicine and Biology 2002, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlhac, F.; Soussan, M.; Maisonobe, J.A.; Garcia, C.A.; Vanderlinden, B.; Buvat, I. Tumor Texture Analysis in 18F-FDG PET: Relationships between Texture Parameters, Histogram Indices, Standardized Uptake Values, Metabolic Volumes, and Total Lesion Glycolysis. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 2014, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, J.C.; Maass-Moreno, R.; Thomas, A.; Ling, A.; Padiernos, E.B.; Steinberg, S.M.; Hassan, R. 18F-FDG PET Assessment of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: Total Lesion Volume and Total Lesion Glycolysis—the Central Role of Volume. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 2020, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J.; Chang, S.H.; Lee, T.Y.; Yoon, S.Y.; Cheon, Y.K.; Shim, C.S.; So, Y.; Chung, H.W. oo Prognostic Value of FDG-PET/CT Total Lesion Glycolysis for Patients with Resectable Distal Bile Duct Adenocarcinoma. Anticancer research 2015, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Im, H.J.; Bradshaw, T.; Solaiyappan, M.; Cho, S.Y. Current Methods to Define Metabolic Tumor Volume in Positron Emission Tomography: Which One Is Better? Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 2018, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draper, N.R. Analysis of Messy Data Volume 1: Designed Experiments, Second Edition by George A. Milliken, Dallas E. Johnson. International Statistical Review 2009, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royston, P. Approximating the Shapiro-Wilk W-Test for Non-Normality. Statistics and Computing 1992, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegel, E.R.; Littell, R.; Milliken, G.; Stroup, W.; Wolfinger, R. SAS® System for Mixed Models. Technometrics 1997, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.; Berry, J.J. The Efficiency of Simulation-Based Multiple Comparisons. Biometrics 1987, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, M.; Andoh, A.; Araki, Y.; Fujiyama, Y.; Bamba, T. Ligation of the Fas Antigen Stimulates Chemokine Secretion in Pancreatic Cancer Cell Line PANC-1. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology (Australia) 2001, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J., I.; P., S.; S.M., C.; T., V.-K.; H., L.; T., H.; S., B.; I., C.; V., D.; R.K., J. Metformin Reduces Desmoplasia in Pancreatic Cancer by Reprogramming Stellate Cells and Tumor-Associated Macrophages. PLoS ONE 2015, 10.

- Xie, K. Interleukin-8 and Human Cancer Biology. Cytokine and Growth Factor Reviews 2001, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solez, K.; Battaglia, D.; Fahmy, H.; Trpkov, K. Pathology of Kidney Transplant Rejection. Current opinion in nephrology and hypertension 1993, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojicevic, A.; Jovanovic, M.; Matkovic, M.; Nestorovic, E.; Stanojevic, N.; Dozic, B.; Glumac, S. Heart Transplant Rejection Pathology. Vojnosanitetski pregled 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, G.R.; Gilbert-Barness, E.F. Pathology of Transplant Rejection and Immunosuppressive Therapy: Part I--Graft-vs.-Host Disease and Organ Rejection. Advances in pediatrics 1990, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, M.; Liu, Z.; Tang, J. Screening and Identification of Key Regulatory Connections and Immune Cell Infiltration Characteristics for Lung Transplant Rejection Using Mucosal Biopsies. International Immunopharmacology 2020, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López Panqueva, R. del P. Liver Biopsies in Transplant Pathology: Histopathological Diagnosis and Clinicopathological Correlation in the Early Post-Transplant Period. Revista Colombiana de Gastroenterologia 2016, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Hoff, D.D.; Ervin, T.; Arena, F.P.; Chiorean, E.G.; Infante, J.; Moore, M.; Seay, T.; Tjulandin, S.A.; Ma, W.W.; Saleh, M.N.; et al. Increased Survival in Pancreatic Cancer with Nab-Paclitaxel plus Gemcitabine. New England Journal of Medicine 2013, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falasca, M.; Kim, M.; Casari, I. Pancreatic Cancer: Current Research and Future Directions. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta—Reviews on Cancer 2016, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahal, A.; Musher, B. Oncolytic Viral Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer. Journal of Surgical Oncology 2017, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Immune System Status | Oncolytic Virotherapy | Mean Tumor Volume (mm3) | SUV | TLG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunocompromised | NA–Control | 428.62 | 0.165 | 0.048 |

| Immunocompromised | TPV/eGFP | 348.68 | 0.227 | 0.041 |

| Immunocompromised | TPV/∆66R/m-IL-2/mCherry | 300.44 | 0.281 | 0.029 |

| Immunocompromised | TPV/∆66R/m-CCL-2/mCherry | 235.50 | 0.241 | 0.045 |

| Immune Reconstituted | NA–Control | 39.99 | 0.328 | 0.195 |

| Immune Reconstituted | TPV/eGFP | 117.62 | 0.231 | 0.033 |

| Immune Reconstituted | TPV/∆66R/m-IL-2/mCherry | 145.87 | 0.333 | 0.033 |

| Immune Reconstituted | TPV/∆66R/m-CCL-2/mCherry | 168.06 | 0.258 | 0.035 |

| Immune System Status | Oncolytic Virotherapy | Mean Tumor Volume (mm3) | SUV | TLP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunocompromised | NA–Control | 428.62 | 0.959 | 0.404 |

| Immunocompromised | TPV/eGFP | 348.68 | 1.14 | 0.237 |

| Immunocompromised | TPV/∆66R/m-IL-2/mCherry | 300.44 | 1.16 | 0.139 |

| Immunocompromised | TPV/∆66R/m-CCL-2/mCherry | 235.50 | 0.843 | 0.151 |

| Immune Reconstituted | NA–Control | 39.99 | 0.404 | 0.017 |

| Immune Reconstituted | TPV/eGFP | 117.62 | 0.465 | 0.745 |

| Immune Reconstituted | TPV/∆66R/m-IL-2/mCherry | 145.87 | 0.454 | 0.051 |

| Immune Reconstituted | TPV/∆66R/m-CCL-2/mCherry | 168.06 | 0.411 | 0.049 |

| Immune System Status | Oncolytic Virotherapy | Mean Tumor Volume (mm3) | Percent Injected Dose / Gram Tissue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunocompromised | NA–Control | 428.62 | 1.95 |

| Immunocompromised | TPV/eGFP | 348.68 | 3.14 |

| Immunocompromised | TPV/∆66R/m-IL-2/mCherry | 300.44 | 2.49 |

| Immunocompromised | TPV/∆66R/m-CCL-2/mCherry | 235.50 | 2.09 |

| Immune Reconstituted | NA–Control | 39.99 | 1.22 |

| Immune Reconstituted | TPV/eGFP | 117.62 | 1.58 |

| Immune Reconstituted | TPV/∆66R/m-IL-2/mCherry | 145.87 | 1.69 |

| Immune Reconstituted | TPV/∆66R/m-CCL-2/mCherry | 168.06 | 1.41 |

| Immune System Status | Oncolytic Virotherapy | Mean Tumor Volume (mm3) | Nanogram Antibody / Gram Myocardium | Nanogram Antibody / Gram Tumor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunocompromised | NA–Control | 428.62 | 110 | 441 |

| Immunocompromised | TPV/eGFP | 348.68 | 158 | 528 |

| Immunocompromised | TPV/∆66R/m-IL-2/mCherry | 300.44 | 38 | 156 |

| Immunocompromised | TPV/∆66R/m-CCL-2/mCherry | 235.50 | 36 | 138 |

| Immune Reconstituted | NA–Control | 39.99 | 88 | 325 |

| Immune Reconstituted | TPV/eGFP | 117.62 | 82 | 281 |

| Immune Reconstituted | TPV/∆66R/m-IL-2/mCherry | 145.87 | 50 | 149 |

| Immune Reconstituted | TPV/∆66R/m-CCL-2/mCherry | 168.06 | 48 | 81 |

| Treatment | Vehicle | TPV/eGFP | TPV/∆66R/mCCL-2 | TPV/∆66R/mIL-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. animals per group | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

|

Tumor transplant (Number Examined) |

(6) | (6) | (6) | (6) |

| Adenocarcinoma; malignant, primary | ||||

| Present | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Caspase positive | ||||

| Moderate | - | - | 1 | - |

| Marked | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 |

| CD3 positive | ||||

| Minimal | 2 | 2 | - | 2 |

| Mild | 4 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Moderate | - | - | 4 | 1 |

| Marked | - | - | 1 | - |

| CD4 positive | ||||

| Minimal | 4 | 5 | - | 5 |

| Mild | 2 | - | 4 | 1 |

| Moderate | - | - | 2 | - |

| CD68 positive | ||||

| Minimal | - | - | - | 1 |

| Mild | 4 | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| Moderate | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| CD8 positive | ||||

| Minimal | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Treatment | Vehicle | TPV/eGFP | TPV/∆66R/mCCL-2 | TPV/∆66R/mIL-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. animals per group | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

|

Tumor transplant (Number Examined) |

(5) | (6) | (6) | (6) |

| Adenocarcinoma; malignant, primary | ||||

| Present | - | 2 | - | 1 |

| Caspase positive | ||||

| Minimal | 2 | 2 | - | - |

| Moderate | - | 1 | - | - |

| Marked | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| CD3 positive | ||||

| Mild | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| Moderate | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Marked | 1 | 2 | 5 | 4 |

| CD4 positive | ||||

| Minimal | - | 1 | - | - |

| Mild | - | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Moderate | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| Marked | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| CD68 positive | ||||

| Minimal | - | - | 1 | - |

| Mild | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| Moderate | - | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| Marked | 5 | 1 | - | - |

| CD8 positive | ||||

| Minimal | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Group | Animal Number | Immune System Status | Treatment Condition | BxPc-3 Mass Dose / Animal | PET/CT Imaging Agent | SPECT/CT Imaging Agent | Primary Endpoints |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 | D | NA | 5 x 106 cells | NA | Tumor Volume | |

| 2 | 9 | D | Vehicle | [18F]-FDG & [18F]-FLT | [125I] α-GFP | Tumor Volume, PET, SPECT, QWBA and Histology | |

| 3 | 9 | C | Vehicle | [18F]-FDG & [18F]-FLT | [125I] α-GFP | ||

| 4 | 9 | D | TPV/eGFP | [18F]-FDG & [18F]-FLT | [125I] α-GFP | ||

| 5 | 9 | C | TPV/eGFP | [18F]-FDG & [18F]-FLT | [125I] α-GFP | ||

| 6 | 9 | D | TPV/∆66R/mCCL-2 | [18F]-FDG & [18F]-FLT | [125I] α-mCherry | ||

| 7 | 9 | C | TPV/∆66R/mCCL-2 | [18F]-FDG & [18F]-FLT | [125I] α-mCherry | ||

| 8 | 9 | D | TPV/∆66R/mIL-2 | [18F]-FDG & [18F]-FLT | [125I] α-mCherry | ||

| 9 | 9 | C | TPV/∆66R/mIL-2 | [18F]-FDG & [18F]-FLT | [125I] α-mCherry | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).