1. Introduction

Responsible consumption implies that when purchasing products or services, people think beyond their immediate needs and consider the ethical, social, environmental, economic, and cultural consequences of their purchase [

1]. Responsible consumption has been studied, defined, and measured since the 1970s, involving concepts such as green consumers, environmental movements, and ecology [

2]. Carrillo [

3] states that responsible consumption is defined by social, ethical, ecological, and cultural spheres, and it aims to satisfy needs of society. It also concerns others, justice, and solidarity, which allows for the positioning of the consumer as a member of a community that is likely to improve relationships between people and the planet [

4].

However, Mendoza and García López [

5] state that responsible consumption requires an analysis of consumer logic when performing the actions of consumption and decision making through observation, as well as previous knowledge of the object of consumption that goes beyond the fulfillment of personal needs and includes economic, social, and ecological aspects. The authors also point out the importance of information for a consumer when making decisions on purchases or extending the life of the inputs that represent the product or service itself, for example, by acquiring products whose packaging can continue to be used or can be returned to the company or organization that sold it. To ensure that they satisfy the consumer's quality of life conditions, value of time spent shopping, simplification of consumption channels for purchasing through local markets, product availability, among others.

Responsible consumption also involves sensitizing people to their consumption behavior and raising awareness of the impacts of consumption habits, with the aim of satisfying people's basic needs while protecting the environment by avoiding the excessive use of resources. Among people's basic needs are clothing, food, health, education, culture and leisure, transport, housing, and the minimum necessary energy resources [

6]. Since food is a basic need that must be fulfilled at least twice a day, it is of great importance that the consumer is aware of and responsible for not only their private everyday food consumption decisions but also the public consequences of them [

7].

Various authors have developed scales to measure responsible consumption, comprising different dimensions. Jain et al., [

8] designed in India a measurement instrument based on sustainable consumption, ethical consumption, rationality, minimalism, and local consumption, incorporating minimalism as a key dimension in responsible consumption. Minimalism refers to acquiring only the things necessary to live, thus avoiding consumerism. The authors found that the ethical and minimalist dimensions are the most important for consumer satisfaction. A scale measuring the responsible consumption of Spanish-speaking consumers found that consumer literacy and company reputation were the factors with the highest impact on responsible consumption [

9] In the scale proposed for South America by Bianchi et al [

10], according to their literature review, they consider three dimensions of responsible consumption: ethical, ecological and social or supportive. They found that positively worded items present higher reliability. They also found that care should be taken to evaluate the attitude of individuals rather than that of companies. It is concluded that more items should be included in the ecological dimension and that the dimension of adequate use of resources should be considered because they show better indicators of responsible consumption.

Responsible food consumption has been evaluated from different perspectives. A survey administered in European countries [

11] focused on determining where food is bought, the factors considered when choosing food, and the frequency of the disposal of food waste at home. In Spain, Chinea et al. [

12] identified the psychosocial variables upon which sustainable consumption behavior is based. Another study in Turkey analyzed the behavior of tourists in relation to their attitude to local food consumption, which favors the development of local businesses, the consumption of local food and encourages tourists to take care of the resources of the destinations where they travel. Having tourists who behave responsibly can benefit the local population not only economically, but also environmentally and socially. [

13].

The existing research in this area indicates that the measurement of responsible food consumption is conducted at different stages of the food supply chain, considers psychosocial dimensions, and, in general, is aimed at adults, with a lack of similar research on children or adolescents. The present study therefore aims to address this research gap by considering the ethical, environmental, social, solidarity-based, and consumer health dimensions of responsible food consumption in a group of adolescents.

Previous works have identified factors that influence the consumption of ultra-processed food by adolescents, such as individual, interpersonal, and contextual aspects, as well as public policies [

14] However, they do not consider the environmental impact of such consumption, instead focusing only on the impact on public health. The instrument validated in this work allows for the identification of both responsible consumption—considering the dimensions mentioned above—and food consumption frequency, which can have an effect on adolescents’ nutritional status [

15].

The questionnaire used in this study evaluated the dimensions of knowledge, attitude, emotions, and practice. According to the reasoned action model, behavior is the result of the interrelationship between critical attitude, previous knowledge, and emotions. In this way, depending on the expected results of their behavior, people engage with each one of these dimensions before participating in consumer behavior [

16]. As for the practice dimension, it is identified as the behaviors or actions that are carried out intentionally with the purpose of caring for the environment or minimizing its damage [

17]

It is important for decision making and activities to be carried out in relation to this age group, whether from institutions, educational centers, organizations and/or associations. Such activities can be lectures, workshops or courses in which the importance of working from a responsible food consumption approach is evidenced. Therefore, this work aims to design and validate a responsible food consumption scale in adolescents “Escala de consumo resposable de alimentos en adolescentes” (ECRAA) using a sample of junior high school students.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Subjects

The data included in this study were obtained from 288 junior high school students. The sample was obtained by simple random sampling. From two localities in the municipality of Santa Cruz Xoxocotlán and one locality in the municipality of Ejutla de Crespo in the state of Oaxaca, Mexico. The localities and schools where the ECRAA was applied were San Isidro Monjas (Escuela Secundaria No. 193), Esquipulas (Escuela Secundaria 21 de noviembre), and Heroica Ciudad de Ejutla de Crespo (Escuela Secundaria Técnica 130). The study was authorized by the authorities of each school. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) to be a student officially enrolled in junior high school; (b) to be older than 10 and younger than 18 years of age; and (c) to voluntarily participate in the online survey. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) lacking a device upon which to answer the online survey; (b) to be outside the age range of the target population; and (c) to decline to participate in the online survey.

Procedure

The instrument was developed in 4 stages:

Stage 1: Design of the instrument. A responsible food consumption scale was created based on reasoned action theory [

15] and considering the following subvariables: knowledge, emotions, attitudes, and practice.

Stage 2: Validation of the instrument. In this stage, the appropriateness of the instrument for adolescents was evaluated. Ten experts in community nutrition and adolescent psychology with at least 15 years of experience in their professional practice, preselected through snowball sampling, participated. They were asked to read the instrument and complete a questionnaire about their assessment of it, which included evaluation scales on clarity, objectivity, organization, sufficiency, and coherence. For codification, a 5-point Likert scale was used for each item: deficient = 1, regular = 2, good = 3, very good = 4, and excellent = 5. The questionnaires were administered at the experts’ workplaces. After the evaluation, two questions on the ECRAA were modified to gain more precision following recommendations by the experts. These results were processed and analyzed in Microsoft Excel using Aiken’s V coefficient to measure the domain of the items proposed in relation to the content.

Stage 3: Application of the instrument. The survey was conducted through Google Forms and included 39 items in Spanish –now translated to English in this article– that took 10–12 minutes to answer. In this questionnaire, the thematic axes were identification data, sociodemographic information, and the evaluation of responsible consumption in the subvariables of knowledge, attitudes, emotions, and practice.

Stage 4: Data analysis. The results were tested with a confirmatory factor analysis in Amos Vo. 24. The Hu and Bentler goodness-of-fit index was used. Then, reliability was estimated using the omega coefficient. The elimination of four questions, suggested following the analysis, was performed to achieve Cronbach’s Alpha values higher than 0.8. These four questions were as follow: Em6—I like to buy packaged foods that generate little or no waste; P1—When I eat packaged foods I never finish all the contents; A2—At school, I prefer to buy food prepared at the school cooperative rather than packaged foods; and A14—At home or at school I prefer to eat a handmade tortilla rather than a machine-made tortilla. Results section shows the final questions used in the survey.

Total value on the responsible food consumption index scored 115 points making a 100%, such number was obtained from the addition the values assigned to each answer. Determination of responsible food consumption levels was calculated in thirds with the resulting categories being as follow: 0 to 38 points as low level, 39 to 77 points as medium level and 78 to 115 points as high level.

3. Results

The questionnaire was administered to 288 junior high school students aged 12–14: 56.9% were female, and 43.1% were male. First-year students were the most willing to answer the questionnaire (43.8%).

To evaluate the content validity and appropriateness of the questionnaire, clarity, objectivity, organization, sufficiency, and coherence were considered. According to the experts, the 23 items of the scale of responsible food consumption in adolescents (ECRAA) were adequate (V > .70).

Table 1 shows the results of the analysis of each dimension.

The average value for the 23 items in the five evaluated attributes obtained was 0.92, with a minimum value of 0.84 and a maximum value of 1. The practice dimension had the highest average value of 0.96, while the objectivity and sufficiency dimensions had the highest average value of 0.93.

Regarding the confirmatory factor analysis, the ECRAA’s structure was analyzed with goodness-of-fit indices (χ2= 350.577, p < 0.001; CFI= 0.935; TLI= 0.925; RMSEA= 0.045, χ2/df = 1.594). The factorial loads were found to be adequate. The average variance extracted (AVE) and the composite reliability were found to be acceptable (

Table 2). In summary, the 23-item model is satisfactory.

Table 2.

Factorial loads of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (AFC).

Table 2.

Factorial loads of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (AFC).

| Item |

Knowledge |

Attitudes |

Emotions |

Practice |

| 1 |

1 |

|

|

|

| 2 |

-0.97 |

|

|

|

| 3 |

-0.87 |

|

|

|

| 4 |

-1.04 |

|

|

|

| 5 |

-0.64 |

|

|

|

| 6 |

-0.80 |

|

|

|

| 7 |

|

1.08 |

|

|

| 8 |

|

1.13 |

|

|

| 9 |

|

1.0 |

|

|

| 10 |

|

1.08 |

|

|

| 11 |

|

1.0 |

|

|

| 12 |

|

1.14 |

|

|

| 13 |

|

-0.68 |

|

|

| 14 |

|

|

0.96 |

|

| 15 |

|

|

0.89 |

|

| 16 |

|

|

1.08 |

|

| 17 |

|

|

1.14 |

|

| 18 |

|

|

1 |

|

| 19 |

|

|

|

1.0 |

| 20 |

|

|

|

1.10 |

| 21 |

|

|

|

0.84 |

| 22 |

|

|

|

0.57 |

| 23 |

|

|

|

1.11 |

| AVE |

0.80 |

1.05 |

1.04 |

0.89 |

| FC |

0.85 |

0.93 |

0.88 |

0.85 |

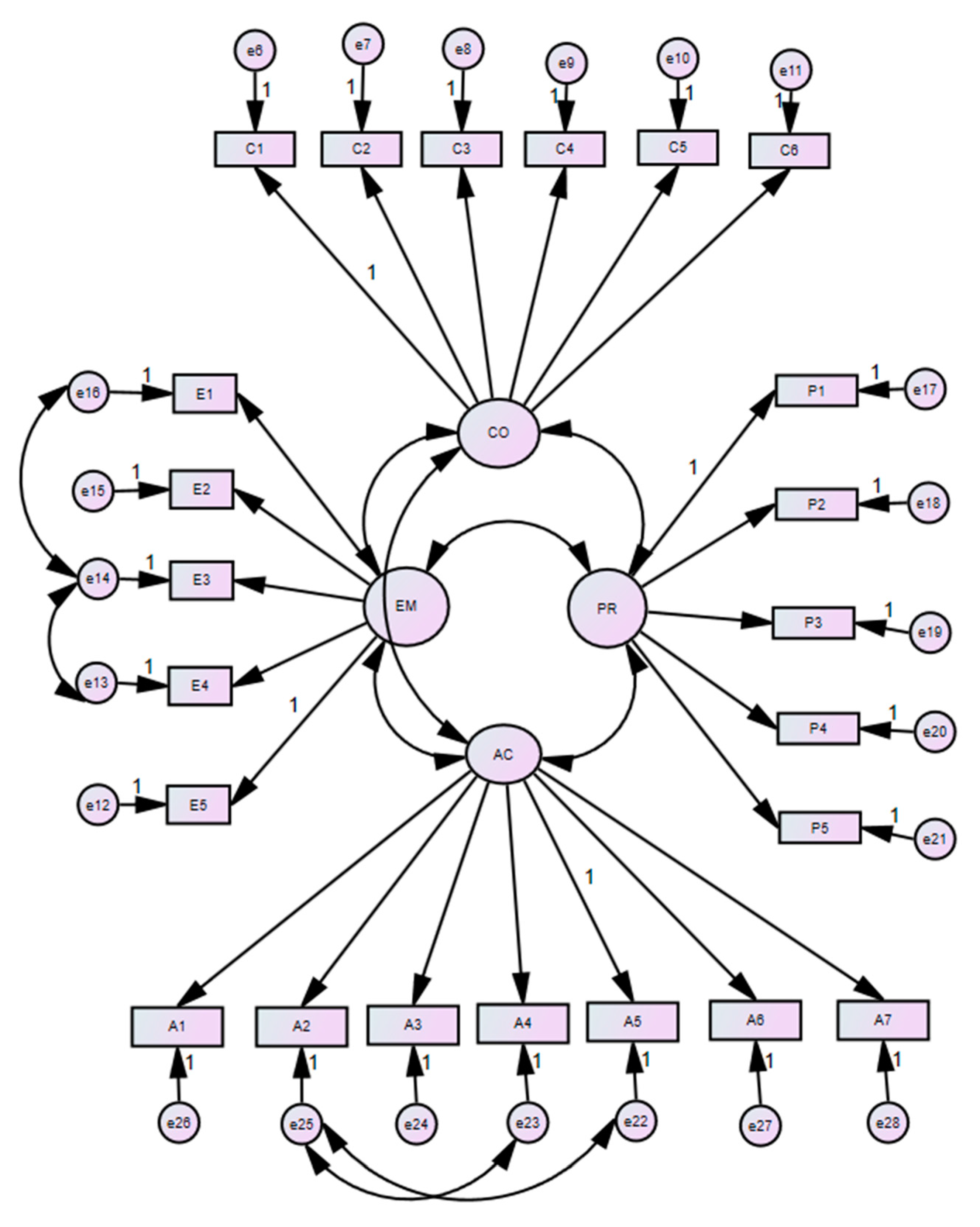

Figure 1.

Model of the internal structure of the questionnaire to identify responsible food consumption in adolescents (ECRAA). The factorial loads are shown in

Table 2.

Figure 1.

Model of the internal structure of the questionnaire to identify responsible food consumption in adolescents (ECRAA). The factorial loads are shown in

Table 2.

Factorial Loads

Regarding reliability, Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was determined. The value obtained (> .70) was acceptable, as shown in

Table 3.

A total average of 75.2 was found as a result of calculations from the responsible food consumption index coming from the ECRAA, with a minimum of 51.3 and a maximum of 96.5 which was categorized as medium level.

Table 4 presents the final version of the ECRAA and the values assigned to each answer.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The aim of this work was to determine the validity of the ECRAA based on its content, structure, and reliability using a sample of junior high school students. The scale evaluates four aspects determining responsible food consumption: knowledge, attitudes, emotions, and practice. The contribution of the ECRAA relies on the identification of the level of responsible food consumption in adolescents, a vulnerable group, and it focuses on topics that may become risk factors for their life and health in the future from the perspective of various disciplines [

18]. The scales used to measure responsible consumption have been validated with a confirmatory factor analysis [

8]; [

10]; [

19]. What makes the ECRAA different is that it focuses on food consumption. In addition, the development of the ECRAA included an analysis conducted by a panel of experts on nutrition and diet, and the creation of a model of factors that have an impact on the consumption and the reliability of data. Therefore, the ECRAA is an adequate instrument for determining the index of responsible food consumption in adolescents.

The scale used to measure responsible consumption designed by Gupta and Agrawal [

20] considers social, ethical, sustainable, green, and environmental aspects. The ECRAA presented in this work includes these topics but focuses on foods, and it contains questions aimed at adolescents, considering food products that are more accessible and available to them.

The current context of life on the planet, in which the consequences of both environmental pollution and the increasing prevalence of non-transmissible diseases are evident, endangers the security and quality of life of future generations [

21]. Therefore, the scientific value of the ECRAA is that it allows for the generation of a baseline from which to work with this age group to aid in the prevention of future ecological and health problems.

The advantages of the ECRAA include the following: it is an instrument that is easy to follow and apply, it maintains adolescents' attention because it is brief and the time it takes to answer it is less than 20 minutes., and it measures how much adolescents practice responsible food consumption. This complements the data obtained on knowledge, attitudes, and emotions; thus, the index of responsible food consumption is accurately determined based on the four dimensions.

Despite the abovementioned advantages, the following limitations were identified in the present work: The first is that the scale was applied online, which does not allow for real control over the context and the situation in which the scale is answered. The second drawback is that, since the scale is self-reported, there may be a risk of bias in the answers given, resulting from a search for answers that are desirable and socially expected, particularly if adolescents' need for acceptance and belonging is considered [

22]. In future studies, it would be recommended to apply the scale in person, which would also allow clarifying doubts that may arise at the time of answering it. On the other hand, for the limitation of obtaining socially accepted or desired responses, the scale can be applied by a trained person [

23].

It is concluded that the ECRAA is validity and has satisfactory properties. It can be used in school, institutional, corporate, and social environments, and for academic and scientific research purposes. In future studies, other tests of reliability and analysis can be applied (convergent and discriminant validity, known-groups validity, nomological validity, and/or social desirability bias). In addition, other studies can be performed in different contexts, countries, or cultures to prove the reliability, validity, and invariability in their environments.

Author Contributions

Gloria Irene Ponce Quezada: conceptualization, analysis, survey administration, and the writing of the first draft. María Eufemia Pérez Flores: conceptualization, methodology, survey administration follow-up, analysis, project management, and fund acquisition.

Funding

This study was financially supported by Instituto Politécnico Nacional through Secretaría de Investigación y Posgrado in the research project El consumo responsable de los alimentos: evaluación de una propuesta participativa y solidaria en una población de adolescentes de los Valles Centrales de Oaxaca [Responsible food consumption: evaluation of a participative, solidarity-based proposal in a population of adolescents in the Central Valleys of Oaxaca], 20231296 and CONAHCYT for the grant for the Doctorado en Ciencias en Conservación y Administración de Recursos Naturales [Doctorate in Science of Conservation and Management of Natural Resources program], CVU 578859.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to anonymous and voluntary participation in this survey.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Instituto Politécnico Nacional for their support of this study through and to CONAHCYT for the grant for the Doctorate program. They also thank the school authorities: the assistant principal and principal at Escuela Secundaria General 21 de noviembre, and the academic coordinator, assistant principal, and principal at Escuelas Secundarias Técnicas Número 30 y 193.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- D. M. Romero Valenzuela and B. O. Camarena Gómez, ‘El consumo sustentable y responsable: conceptos y análisis desde el comportamiento del consumidor’, Revista Vértice Universitario, jul. 2023, vol. 25, no. 94. [CrossRef]

- S. Dueñas Ocampo, J. Perdomo-Ortiz and L.E.V. Castaño, ‘The concept of socially responsible consumption and its measurement. A review of the literature’, Estudios Gerenciales, 2014, vol. 30, no. 132, pp. 287–300.

- Á. Carrillo Punina, “Factores que impulsan y limitan el consumo responsable”, ECA Sinergia, 2017, Vol. 8, No. 2, 99–112.

- D. S. López, R. L. Marín and S. Ruiz De Maya, “Introducing Personal Social Responsibility as a key element to upgrade CSR”, ESIC, 2017, Vol. 21, 146–163.

- M. Mendoza Acevedo and S. I. García López Legorreta, ‘Diagnóstico del Consumo responsable. Caso estudio: el valle de Toluca, estado de México’, Perspectivas: Revista Científica de la Universidad de Belgrano, jul. 2022, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 2–14.

- B. Nubia-Arias, ‘El consumo responsable: educar para la sostenibilidad ambiental.’, AiBi Revista de Investigación, Administración e Ingeniería, jan. 2016, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 29–34. [CrossRef]

- G. P. Prendergast and A. S. L. Tsang, ‘Explaining socially responsible consumption’, Journal of Consumer Marketing, feb. 2019, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 146–154. [CrossRef]

- V. K. Jain, A. Dahiya, V. Tyagi and P. Sharma, ‘Development and validation of scale to measure responsible consumption’, APBJA, 2023, vol.15, no. 5, pp. 795-814. [CrossRef]

- B. Amezcua, A.D. La Peña, M.T. Ríos and J.M. Soto, ‘Escala para la medición del comportamiento de consumo responsable en consumidores Hispanohablantes’, Ciencias Administrativas. Teoría y Praxis, 2018, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 11–26.

- E. C. Bianchi, G. Kosiak de Gesualdo, Ferreyra Silvia, B. Carmelé, D. Tubaro and J.M. Bruno, ‘Hacia una escala de consumo responsable sustentable (CRS)’, oct 2013.

- J. Paužuolienė, L. Šimanskienė and M. Fiore, ‘What about Responsible Consumption? A Survey Focused on Food Waste and Consumer Habits’, Sustainability, jul. 2022, vol. 14, no. 14, p. 8509. [CrossRef]

- C. Chinea, E. Suárez, B. Hernández and D. Gil, ‘Evaluating responsible consumption through the purchase of organic products, life meaningfulness and the meaning attributed to food. Responsible consumption and personal meanings’, Psyecology, 2023 vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 20–41.

- S. Balıkçıoğlu Dedeoğlu, D. Eren, N. Sahin Percin and S. Aydin, ‘Do tourists’ responsible behaviors shape their local food consumption intentions? An examination via the theory of planned behavior’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, nov. 2022, vol. 34, no. 12, pp. 4539–4561. [CrossRef]

- P. Henrique. Guerra, E. H. Corgosinho Ribeiro, R. Fagundes Lopes, L. M. Balestreri Nunes, I. C. Viali, B. Da Penha F., I. Aparecida de Almeida, M. Huber Garzella and J. A. Cardoso da Silveira ‘Variables Associated with Ultra-Processed Foods Consumption among Brazilian Adolescents: A Systematic Review’, Adolescents, Jul. 2023, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 467–477.

- A. Martí del Moral, C. Calvo and A. Martínez, ‘Ultra-processed food consumption and obesity—a systematic review’, Nutr. Hosp, 2020, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 177–185.

- C. Izquierdo Maldonado, I. Vaca Aguirre and R. Mena Campar, ‘El nuevo sujeto social del consumo responsable’, Estudios de la Gestión, Revista Internacional de Administración, 2018, vol. 4, pp. 97–123. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Mejía Gil, ‘Consumo responsable: de la teoría a la práctica’, in Marketing Social: Un enfoque latinoamericano, Fondo Editorial Universidad EAFIT, 2022, pp. 77–106.

- D. V. Figueroa Verdecia, Y. Navarro Sánchez and F.A. Romero Guzmán, ‘Situación actual de la adolescencia y sus principales desafíos’, Gaceta Médica Espirituana, 2018, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 98–105.

- L. E. Villa Castaño, J. Perdomo, S. Dueñas and W. Durán, ‘Consumo socialmente responsable: medición y contrastación en Colombia, México y Perú’, Political Science, 2018.

- S. Gupta and R. Agrawal, ‘Environmentally Responsible Consumption: Construct Definition, Scale Development, and Validation’, Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag, Jul. 2018, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 523–536.

- A. B. Gilmore, A. Fabbri, F. Baum, A. Bertscher, K. Bondy, H. Chang, S. Demaio, A. Erzse, N. Freudenberg, S. Friel, K. J. Hofman, P. Johns, S. Abdool Karim, J. Lacy-Nichols, C. Maranha Paes de Carvallo, R. Marten, M. McKee, M. Petticrew, L. Robertson, V. Tangcharoensathien, A. M. Thow, ‘Defining and conceptualising the commercial determinants of health’, The Lancet, apr. 2023, vol. 401, no. 10383, pp. 1194–1213. [CrossRef]

- A. D. Calero, J.P. Barreyro, J. Formoso and I. Injoque-Ricle, ‘Inteligencia emocional y necesidad de pertenencia al grupo de pares durante la adolescencia’, Subjetividad y procesos cognitivos, 2001 vol. 22, no. 2.

- G. Montes, ‘Metodología y técnicas de diseño y realización de encuestas en el área rural’, Temas Sociales, 2000, no. 21, pp. 39–50.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).