Submitted:

07 May 2024

Posted:

08 May 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Selected Epidemiological Aspects of TBI

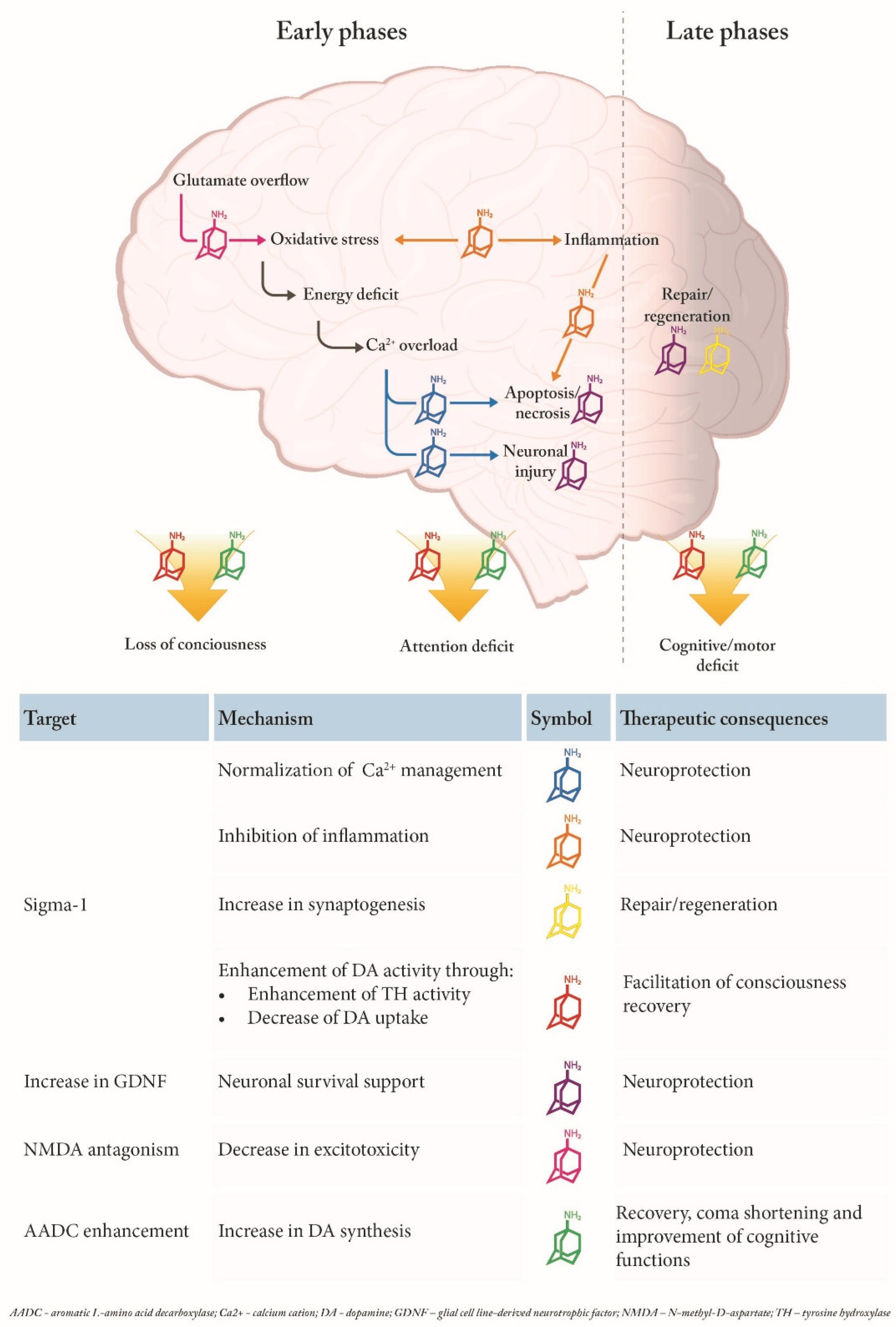

2. Pathophysiology of TBI and Possible Targets of Amantadine

3. Primary Damage

4. Secondary Damage

4.1. Cerebral Metabolic Dysfunction

4.2. Cerebrovascular autOREGULATION and Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Reactivity

4.3. Increased Intracerebral Pressure (ICP)

4.4. Cerebral Oedema

4.5. Excitotoxicity

4.6. Mitochondrial Dysfunction

4.7. Oxidative Stress

4.8. Inflammatory Processes

4.9. Necrosis and Apoptosis

4.10. Functional/Structural Recovery

4.11. Fatigue and Depression

5. Disorders of Consciousness (DOC) – Recovery Enhancement

6. Potential Mechanism of Amantadine Effects in TBI - NMDA Receptors and Beyond

6.1. Amantadine Targets and Their Potential Role in TBI

6.1.1. NMDA Receptors and Neuroprotection

6.1.2. Sigma 1 Receptors and Neuroprotection

6.1.3. AADC and Neuroactivation

6.1.3. GDNF and Neuroprotection/Regeneration

6.1.3. Other Possible MoAs

6. Preclinical and Clinical Evidence of Amantadine Efficacy in TBI

6.1. Preclinical Studies

6.2. Clinical Studies

6. Non-Traumatic Brain Injury

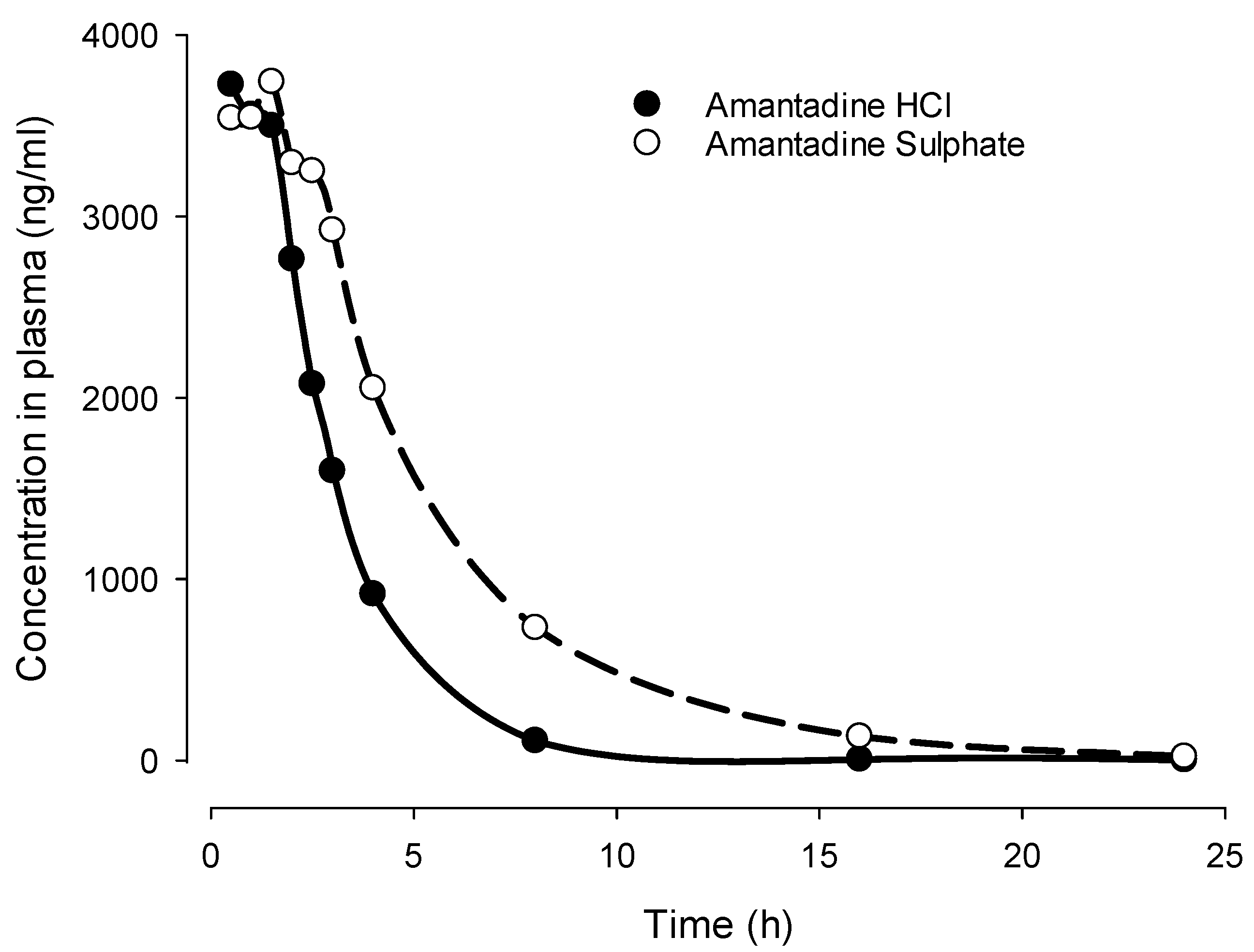

7. Differences between Amantadine Sulphate and Hydrochloride

- Possibility of treatment when oral use is not possible or difficult like in unconscious state (e.g., TBI) or swallowing difficulties (e.g., Parkinson´s disease).

- Faster onset of action as compared to oral administration which could offer advantage in e.g., TBI) or in akinetic crisis [186].

- Better monitoring of PK-PD relationship through flexible adjustment of infusion speed

8. Future Research Questions

- -

- What are the effects of amantadine in disorders of consciousness with a therapy duration of more than four weeks?

- -

- How does amantadine work in different disorders of consciousness, especially those with non-traumatic causes?

- -

- What is the interaction of amantadine administered in combination with other drugs (e.g., with cerebrolysin) in patients with impaired consciousness?

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agarwal, N. Traumatic Brain Injury. Available online: https://www.aans.org/Patients/Neurosurgical-Conditions-and-Treatments/Traumatic-Brain-Injury (accessed 2020).

- Dawodu, S.T. Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) - Definition, Epidemiology, Pathophysiology. Available online: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/326510-overview#showall.

- Lingsma, H.F.; Roozenbeek, B.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Murray, G.D.; Maas, A.I. Early prognosis in traumatic brain injury: from prophecies to predictions. Lancet Neurol 2010, 9, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazinova, A.; Rehorcikova, V.; Taylor, M.S.; Buckova, V.; Majdan, M.; Psota, M.; Peeters, W.; Feigin, V.; Theadom, A.; Holkovic, L.; et al. Epidemiology of Traumatic Brain Injury in Europe: A Living Systematic Review. Journal of neurotrauma 2021, 38, 1411–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majdan, M.; Plancikova, D.; Maas, A.; Polinder, S.; Feigin, V.; Theadom, A.; Rusnak, M.; Brazinova, A.; Haagsma, J. Years of life lost due to traumatic brain injury in Europe: A cross-sectional analysis of 16 countries. PLoS Med 2017, 14, e1002331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majdan, M.; Plancikova, D.; Brazinova, A.; Rusnak, M.; Nieboer, D.; Feigin, V.; Maas, A. Epidemiology of traumatic brain injuries in Europe: a cross-sectional analysis. Lancet Public Health 2016, 1, e76–e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, S.K.; Dixon, C.E.; Banik, N.L. Molecular mechanisms in the pathogenesis of traumatic brain injury. Histol Histopathol 2002, 17, 1137–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veenith, T.; Goon, S.; Burnstein, R.M. Molecular mechanisms of traumatic brain injury: the missing link in management. World J Emerg Surg 2009, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrahi, A.; Braun, M.; Ahluwalia, M.; Gupta, R.V.; Wilson, M.; Munie, S.; Ahluwalia, P.; Vender, J.R.; Vale, F.L.; Dhandapani, K.M.; et al. Revisiting Traumatic Brain Injury: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Interventions. Biomedicines 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traeger, J.; Hoffman, B.; Misencik, J.; Hoffer, A.; Makii, J. Pharmacologic Treatment of Neurobehavioral Sequelae Following Traumatic Brain Injury. Crit Care Nurs Q 2020, 43, 172–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, K.J. Pathophysiology of Traumatic Brain Injury. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2017, 28, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, A.C.; Daneshvar, D.H. The neuropathology of traumatic brain injury. Handb Clin Neurol 2015, 127, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.M.; Huang, S.C.; Hattori, N.; Glenn, T.C.; Vespa, P.M.; Yu, C.L.; Hovda, D.A.; Phelps, M.E.; Bergsneider, M. Selective metabolic reduction in gray matter acutely following human traumatic brain injury. Journal of neurotrauma 2004, 21, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enevoldsen, E.M.; Jensen, F.T. Autoregulation and CO2 responses of cerebral blood flow in patients with acute severe head injury. J Neurosurg 1978, 48, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, M.; Stein, D.M.; Hu, P.F.; Aarabi, B.; Sheth, K.; Scalea, T.M. Traditional systolic blood pressure targets underestimate hypotension-induced secondary brain injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012, 72, 1135–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, D.M.; Lindel, A.L.; Murdock, K.R.; Kufera, J.A.; Menaker, J.; Scalea, T.M. Use of serum biomarkers to predict secondary insults following severe traumatic brain injury. Shock 2012, 37, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unterberg, A.W.; Stover, J.; Kress, B.; Kiening, K.L. Edema and brain trauma. Neuroscience 2004, 129, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullock, R.; Zauner, A.; Woodward, J.J.; Myseros, J.; Choi, S.C.; Ward, J.D.; Marmarou, A.; Young, H.F. Factors affecting excitatory amino acid release following severe human head injury. J Neurosurg 1998, 89, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellergard, P.; Sjogren, F.; Hillman, J. The cerebral extracellular release of glycerol, glutamate, and FGF2 is increased in older patients following severe traumatic brain injury. Journal of neurotrauma 2012, 29, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lifshitz, J.; Sullivan, P.G.; Hovda, D.A.; Wieloch, T.; McIntosh, T.K. Mitochondrial damage and dysfunction in traumatic brain injury. Mitochondrion 2004, 4, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, C.; Roberts, K.N.; Markesbery, W.R.; Scheff, S.W.; Lovell, M.A. Oxidative stress in head trauma in aging. Free Radic Biol Med 2006, 41, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streit, W.J. Microglia as neuroprotective, immunocompetent cells of the CNS. Glia 2002, 40, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, S.M.; Rothwell, N.J.; Gibson, R.M. The role of inflammation in CNS injury and disease. Br J Pharmacol 2006, 147 Suppl 1, S232–S240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, H.W.; Hwang, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, M.J.; Han, H.S.; Lee, W.H.; Suk, K. Microglia-inhibiting activity of Parkinson’s disease drug amantadine. Neurobiol Aging 2012, 33, 2145–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubera, M.; Maes, M.; Budziszewska, B.; Basta-Kaim, A.; Leskiewicz, M.; Grygier, B.; Rogoz, Z.; Lason, W. Inhibitory effects of amantadine on the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by stimulated in vitro human blood. Pharmacol Rep 2009, 61, 1105–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandinger, K.P.; Hagenah, J.M.; Kluter, H.; Rothermundt, M.; Peters, M.; Vieregge, P. Effects of amantadine treatment on in vitro production of interleukin-2 in de-novo patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neuroimmunology 1999, 98, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, B.A.; Faden, A.I. Cell death mechanisms and modulation in traumatic brain injury. Neurotherapeutics 2010, 7, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossola, B.; Schendzielorz, N.; Chen, S.H.; Bird, G.S.; Tuominen, R.K.; Mannisto, P.T.; Hong, J.S. Amantadine protects dopamine neurons by a dual action: reducing activation of microglia and inducing expression of GDNF in astroglia [corrected]. Neuropharmacology 2011, 61, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranthi, K.; Anand Priya, V.V.M.; Punnagai, K.; Chellathai David, D. A Comparative Free Radical Scavenging Evaluation of Amantadine and Rasagiline. Biomedical & Pharmacology Journal 2019, 12, 1175–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenk, G.L.; Danysz, W.; Roice, D.D. The effects of mitochondrial failure upon cholinergic toxicity in the nucleus basalis. Neuroreport 1996, 7, 1453–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryskamp, D.A.; Korban, S.; Zhemkov, V.; Kraskovskaya, N.; Bezprozvanny, I. Neuronal Sigma-1 Receptors: Signaling Functions and Protective Roles in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Neurosci 2019, 13, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakkar, R.; Raju, R.V.S.; Rajput, A.H.; Sharma, R.K. Amantadine: An antiparkinsonian agent inhibits bovine brain 60 kDa calmodulin-dependent cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase isozyme. Brain Res 1997, 749, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deep, P.; Dagher, A.; Sadikot, A.; Gjedde, A.; Cumming, P. Stimulation of dopa decarboxylase activity in striatum of healthy human brain secondary to NMDA receptor antagonism with a low dose of amantadine. Synapse 1999, 34, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Ma, Y.; Ren, Z.; Xu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, B. Sigma-1 Receptor Modulates Neuroinflammation After Traumatic Brain Injury. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2016, 36, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titus, D.J.; Oliva, A.A.; Wilson, N.M.; Atkins, C.M. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors as therapeutics for traumatic brain injury. Curr Pharm Des 2014, 21, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.M.; Titus, D.J.; Oliva, A.A.; Furones, C.; Atkins, C.M. Traumatic Brain Injury Upregulates Phosphodiesterase Expression in the Hippocampus. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generali, J.A.; Cada, D.J. Amantadine: multiple sclerosis-related fatigue. Hosp Pharm 2014, 49, 710–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenberger, B.; Berg, T.; Herrmann, E.; Hinrichsen, H.; Gerlach, T.; Buggisch, P.; Spengler, U.; Goeser, T.; Nasser, S.; Wursthorn, K.; et al. Efficacy of amantadine on quality of life in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with interferon-alpha and ribavirin: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007, 19, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarantini, L.C.; Miranda-Scippa, A.; Schinoni, M.I.; Sampaio, A.S.; Santos-Jesus, R.; Bressan, R.A.; Tatsch, F.; de Oliveira, I.; Parana, R. Effect of amantadine on depressive symptoms in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with pegylated interferon: a randomized, controlled pilot study. Clinical neuropharmacology 2006, 29, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, D.E.; Bode, L.; Spannhuth, C.W.; Lau, T.; Huber, T.J.; Brodhun, B.; Ludwig, H.; Emrich, H.M. Amantadine in depressive patients with Borna disease virus (BDV) infection: an open trial. Bipolar Disord 2000, 2, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferszt, R.; Kuhl, K.P.; Bode, L.; Severus, E.W.; Winzer, B.; Berghofer, A.; Beelitz, G.; Brodhun, B.; MullerOerlinghausen, B.; Ludwig, H. Amantadine revisited: An open trial of amantadinesulfate treatment in chronically depressed patients with Borna disease virus infection. Pharmacopsychiatry 1999, 32, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogoz, Z.; Skuza, G.; Legutko, B. Repeated co-treatment with imipramine and amantadine induces hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene expression in rats. Journal of physiology and pharmacology : an official journal of the Polish Physiological Society 2007, 58, 219–234. [Google Scholar]

- Posner, J.B.; Saper, C.B.; Plum, F. Diagnosis of stupor and coma; Oxford University Press.: New-York, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zeman, A. Consciousness. Brain 2001, 124, 1263–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckwalter, J.A.; Parvizi, J.; Morecraft, R.J.; van Hoesen, G.W. Thalamic projections to the posteromedial cortex in the macaque. J Comp Neurol 2008, 507, 1709–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.S. Brain structures and mechanisms involved in the control of cortical activation and wakefulness, with emphasis on the posterior hypothalamus and histaminergic neurons. Sleep Med Rev 2000, 4, 471–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiff, N.D. Central thalamic contributions to arousal regulation and neurological disorders of consciousness. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008, 1129, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, S.M.; Guillery, R.W. The role of the thalamus in the flow of information to the cortex. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2002, 357, 1695–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureys, S. The neural correlate of (un)awareness: lessons from the vegetative state. Trends Cogn Sci 2005, 9, 556–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureys, S.; Faymonville, M.E.; Luxen, A.; Lamy, M.; Franck, G.; Maquet, P. Restoration of thalamocortical connectivity after recovery from persistent vegetative state. Lancet 2000, 355, 1790–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureys, S.; Goldman, S.; Phillips, C.; Van Bogaert, P.; Aerts, J.; Luxen, A.; Franck, G.; Maquet, P. Impaired effective cortical connectivity in vegetative state: preliminary investigation using PET. Neuroimage 1999, 9, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bales, J.W.; Wagner, A.K.; Kline, A.E.; Dixon, C.E. Persistent cognitive dysfunction after traumatic brain injury: A dopamine hypothesis. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 2009, 33, 981–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meythaler, J.M.; Brunner, R.C.; Johnson, A.; Novack, T.A. Amantadine to improve neurorecovery in traumatic brain injury-associated diffuse axonal injury: a pilot double-blind randomized trial. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2002, 17, 300–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plum, F.; Posner, J.B. The diagnosis of stupor and coma. Contemp Neurol Ser 1972, 10, 1–286. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cooksley, T.; Rose, S.; Holland, M. A systematic approach to the unconscious patient. Clin Med (Lond) 2018, 18, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laureys, S.; Celesia, G.G.; Cohadon, F.; Lavrijsen, J.; Leon-Carrion, J.; Sannita, W.G.; Sazbon, L.; Schmutzhard, E.; von Wild, K.R.; Zeman, A.; et al. Unresponsive wakefulness syndrome: a new name for the vegetative state or apallic syndrome. BMC Med 2010, 8, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacino, J.T.; Ashwal, S.; Childs, N.; Cranford, R.; Jennett, B.; Katz, D.I.; Kelly, J.P.; Rosenberg, J.H.; Whyte, J.; Zafonte, R.D.; et al. The minimally conscious state: definition and diagnostic criteria. Neurology 2002, 58, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, M.A.; Vanhaudenhuyse, A.; Thibaut, A.; Moonen, G.; Laureys, S. From unresponsive wakefulness to minimally conscious PLUS and functional locked-in syndromes: recent advances in our understanding of disorders of consciousness. J Neurol 2011, 258, 1373–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, G.; Fazekas, F. Cardiopulmonary arrest is the most frequent cause of the unresponsive wakefulness syndrome: A prospective population-based cohort study in Austria. Resuscitation 2016, 103, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Lei, J.; Gao, G.; Feng, J.; Mao, Q.; Jiang, J. Prevalence of persistent vegetative state in patients with severe traumatic brain injury and its trend during the past four decades: A meta-analysis. NeuroRehabilitation 2017, 40, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bender, A. S3-LL Neurologische Rehabilitation bei Koma und schwerer Bewusstseinsstörung im Erwachsenenalter. DEUTSCHE GESELLSCHAFT FÜR NEUROREHABILITATION E.V. (DGNR) (Hrsgb.), Leitlinien für die Neurorehabilitation. 2022, 1, 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, A.; Eifert, B.; Rubi-Fessen, I.; Jox, R.J.; Maurer-Karattup, P.; Muller, F. The Neurological Rehabilitation of Adults With Coma and Disorders of Consciousness. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2023, 120, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danysz, W.; Dekundy, A.; Scheschonka, A.; Riederer, P. Amantadine: reappraisal of the timeless diamond-target updates and novel therapeutic potentials. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2021, 128, 127–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornhuber, J.; Retz, W.; Riederer, P. Slow accumulation of psychotropic substances in the human brain. Relationship to therapeutic latency of neuroleptic and antidepressant drugs? Journal of neural transmission. Supplementum 1995, 46, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Danysz, W.; Gossel, M.; Zajaczkowski, W.; Dill, D.; Quack, G. Are NMDA antagonistic properties relevant for antiparkinsonian-like activity in rats? case of amantadine and memantine. J Neural Transm Park Dis Dement Sect 1994, 7, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesselink, M.B.; DeBoer, B.G.; Breimer, D.D.; Danysz, W. Brain penetration and in vivo recovery of NMDA receptor antagonists amantadine and memantine: A quantitative microdialysis study. Pharm Res 1999, 16, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monaghan, D.T.; Yao, D.; Cotman, C. L-[3H]Glutamate binds to kainate-, NMDA- and AMPA- sensitive binding sites: an autoradiographic analysis. Brain Res 1985, 340, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotman, C.W.; Iversen, L.L. Excitatory aminio acids in the brain - focus on NMDA receptors. Trends Neurosci 1987, 10, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faden, A.I.; Demediuk, P.; Panter, S.S.; Vink, R. The role of excitatory amino acids and NMDA receptors in traumatic brain injury. Science 1989, 244, 798–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rader, R.K.; Lanthorn, T.H. Experimental ischemia induces a persistent depolarisation blocked by decreased calcium and NMDA antagonists. Neurosci Lett 1989, 99, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikonomidou, C.; Turski, L. Why did NMDA receptor antagonists fail clinical trials for stroke and traumatic brain injury? Lancet Neurol 2002, 1, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, S.; Pouladi, M.A.; Talantova, M.; Yao, D.; Xia, P.; Ehrnhoefer, D.E.; Zaidi, R.; Clemente, A.; Kaul, M.; Graham, R.K.; et al. Balance between synaptic versus extrasynaptic NMDA receptor activity influences inclusions and neurotoxicity of mutant huntingtin. Nat Med 2009, 15, 1407–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, P.; Chen, H.S.; Zhang, D.; Lipton, S.A. Memantine Preferentially Blocks Extrasynaptic over Synaptic NMDA Receptor Currents in Hippocampal Autapses. J Neurosci 2010, 30, 11246–11250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, T.K. Novel pharmacologic therapies in the treatment of experimental traumatic brain injury - a review. J Neurotrauma 1993, 10, 215–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, C.G.; Danysz, W.; Quack, G. Glutamate in CNS Disorders as a target for drug development: an update. Drug News Perspect 1998, 11, 523–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danysz, W.; Parsons, C.G.; Bresink, I.; Quack, G. Glutamate in CNS disorders - A revived target for drug development. Drug News Perspect 1995, 8, 261–277. [Google Scholar]

- Loane, D.J.; Faden, A.I. Neuroprotection for traumatic brain injury: translational challenges and emerging therapeutic strategies. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2010, 31, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornhuber, J.; Schoppmeyer, K.; Riederer, P. Affinity of 1-aminoadamantanes for the sigma binding site in post-mortem human frontal cortex. Neurosci Lett 1993, 163, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, V.H.; Kassiou, M.; Johnston, G.A.R.; Christie, M.J. Comparison of binding parameters of sigma-1 and sigma-2 binding sites in rat and guinea pig brain membranes: novel subtype-selective trishomocubanes. Eur.J.Pharmacol. 1996, 311, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peeters, M.; Romieu, P.; Maurice, T.; Su, T.P.; Maloteaux, J.M.; Hermans, E. Involvement of the sigma 1 receptor in the modulation of dopaminergic transmission by amantadine. Eur.J Neurosci. 2004, 19, 2212–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piechal, A.; Jakimiuk, A.; Mirowska-Guzel, D. Sigma receptors and neurological disorders. Pharmacological reports : PR 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaciak, K.; Pytka, K. Revisiting the sigma-1 receptor as a biological target to treat affective and cognitive disorders. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 2022, 132, 1114–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnet, F.P. Sigma-1 receptor as regulator of neuronal intracellular Ca2+: clinical and therapeutic relevance. Biol Cell 2005, 97, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiser, S.D.; Patrick, S.L.; Mascarella, S.W.; Downing-Park, J.; Bai, X.; Carroll, F.I.; Walker, J.M.; Patrick, R.L. Stimulation of rat striatal tyrosine hydroxylase activity following intranigral administration of sigma receptor ligands. Eur J Pharmacol 1995, 275, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudelsky, G.A. Effects of sigma receptor ligands on the extracellular concentration of dopamine in the striatum and prefrontal cortex of the rat. Eur J Pharmacol 1995, 286, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, T.L.; Bridges, S.; Miller, C. Modulation of dopamine uptake in rat nucleus accumbens: effect of specific dopamine receptor antagonists and sigma ligands. Neurosci Lett 2001, 312, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Alvear, G.M.; Werling, L.L. sigma1 Receptors in rat striatum regulate NMDA-stimulated [3H]dopamine release via a presynaptic mechanism. Eur J Pharmacol 1995, 294, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousseaux, C.G.; Greene, S.F. Sigma receptors [sigmaRs]: biology in normal and diseased states. J Recept Signal Transduct Res 2015, 36, 327–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francardo, V. Sigma-1 receptor: a potential new target for Parkinson’s disease? Neural Regen Res 2014, 9, 1882–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, T.; Hayashi, T.; Su, T.P. Compromising sigma-1 receptors at the endoplasmic reticulum render cytotoxicity to physiologically relevant concentrations of dopamine in a nuclear factor-kappaB/Bcl-2-dependent mechanism: potential relevance to Parkinson’s disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2012, 341, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decoster, M.A.; Klette, K.L.; Knight, E.S.; Tortella, F.C. sigma receptor-mediated neuroprotection against glutamate toxicity in primary rat neuronal cultures. Brain Res 1995, 671, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurice, T.; Lockhart, B.P. Neuroprotective and anti-amnesic potentials of sigma (sigma) receptor ligands. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 1997, 21, 69–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, R.; Olivan, S.; Rando, A.; Casas, C.; Osta, R.; Navarro, X. Sigma-1R agonist improves motor function and motoneuron survival in ALS mice. Neurotherapeutics 2012, 9, 814–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, J.; Ieni, J.; Maurice, T. The anti-amnesic and neuroprotective effects of donepezil against amyloid beta25-35 peptide-induced toxicity in mice involve an interaction with the sigma1 receptor. Br J Pharmacol 2006, 149, 998–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oneill, M.; Caldwell, M.; Earley, B.; Canney, M.; Ohalloran, A.; Kelly, J.; Leonard, B.E.; Junien, J.L. The sigma receptor ligand JO 1784 (igmesine hydrochloride) is neuroprotective in the gerbil model of global cerebral ischaemia. Eur J Pharmacol 1995, 283, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Chen, F.; Chen, Z.; Yang, W.; Yue, S.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X. Sigma-1 Receptor: A Potential Therapeutic Target for Traumatic Brain Injury. Front Cell Neurosci 2021, 15, 685201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervero, C.; Blasco, A.; Tarabal, O.; Casanovas, A.; Piedrafita, L.; Navarro, X.; Esquerda, J.E.; Caldero, J. Glial Activation and Central Synapse Loss, but Not Motoneuron Degeneration, Are Prevented by the Sigma-1 Receptor Agonist PRE-084 in the Smn2B/- Mouse Model of Spinal Muscular Atrophy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2018, 77, 577–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.J.; O’Callaghan, J.P.; Miller, D.B.; Chalgeri, S.; Wennogle, L.P.; Davis, R.E.; Snyder, G.L.; Hendrick, J.P. Inhibition of calcium-calmodulin-dependent phosphodiesterase (PDE1) suppresses inflammatory responses. Mol Cell Neurosci 2020, 102, 103449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.M.; Juorio, A.V.; Qi, J.; Boulton, A.A. Amantadine increases aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase mRNA in PC12 cells. J Neurosci Res 1998, 53, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.; Biggs, C.S.; Starr, M.S. Effects of glutamate antagonists on the activity of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase. Amino Acids 1998, 14, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, A.; Kannari, K.; Shen, H.; Maeda, T.; Suda, T.; Matsunaga, M. Amantadine increases L-DOPA-derived extracellular dopamine in the striatum of 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats. Brain Res 2003, 972, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liepert, J. Update on pharmacotherapy for stroke and traumatic brain injury recovery during rehabilitation. Curr Opin Neurol 2016, 29, 700–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barra, M.E.; Izzy, S.; Sarro-Schwartz, A.; Hirschberg, R.E.; Mazwi, N.; Edlow, B.L. Stimulant Therapy in Acute Traumatic Brain Injury: Prescribing Patterns and Adverse Event Rates at 2 Level 1 Trauma Centers. J Intensive Care Med 2019, 885066619841603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karli, D.C.; Burke, D.T.; Kim, H.J.; Calvanio, R.; Fitzpatrick, M.; Temple, D.; Macneil, M.; Pesez, K.; Lepak, P. Effects of dopaminergic combination therapy for frontal lobe dysfunction in traumatic brain injury rehabilitation. Brain Injury 1999, 13, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bales, J.W.; Kline, A.E.; Wagner, A.K.; Dixon, C.E. Targeting Dopamine in Acute Traumatic Brain Injury. Open Drug Discov J 2010, 2, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caumont, A.S.; Octave, J.N.; Hermans, E. Amantadine and memantine induce the expression of the glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in C6 glioma cells. Neurosci Lett 2006, 394, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Tan, H.; Jiang, W.; Zuo, Z. Amantadine alleviates postoperative cognitive dysfunction possibly by increasing glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in rats. Anesthesiology 2014, 121, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, J.; Li, J.; Ni, C.; Zuo, Z. Amantadine Alleviates Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction Possibly by Preserving Neurotrophic Factor Expression and Dendritic Arborization in the Hippocampus of Old Rodents. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitroshina, E.V.; Mishchenko, T.A.; Shirokova, O.M.; Astrakhanova, T.A.; Loginova, M.M.; Epifanova, E.A.; Babaev, A.A.; Tarabykin, V.S.; Vedunova, M.V. Intracellular Neuroprotective Mechanisms in Neuron-Glial Networks Mediated by Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019, 2019, 1036907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.T.; Rao, V.L.; Sailor, K.A.; Bowen, K.K.; Dempsey, R.J. Protective effects of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor on hippocampal neurons after traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurosurg 2001, 95, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Xue, X.; Sun, J.; Wu, Q.; Wang, H.; Guo, Y.; Sun, B. The Promising Effects of Transplanted Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells on the Treatment in Traumatic Brain Injury. J Craniofac Surg 2018, 29, 1689–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnich, J.E.; Mann, S.L.; Stock, M.; Stolzenbach, K.A.; Mortell, B.M.; Soderstrom, K.E.; Bohn, M.C.; Kozlowski, D.A. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) gene delivery protects cortical neurons from dying following a traumatic brain injury. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2010, 28, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahlakeh, G.; Rahbarghazi, R.; Mohammadnejad, D.; Abedelahi, A.; Karimipour, M. Current knowledge and challenges associated with targeted delivery of neurotrophic factors into the central nervous system: focus on available approaches. Cell Biosci 2021, 11, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, K. Therapeutic potential of neurotrophic factors and neural stem cells against ischemic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2000, 20, 1393–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linnerbauer, M.; Rothhammer, V. Protective Functions of Reactive Astrocytes Following Central Nervous System Insult. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 573256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.H.; Kuo, L.T.; Luh, H.T. The Roles of Neurotrophins in Traumatic Brain Injury. Life (Basel) 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianutsos, G.; Chute, S.; Dunn, J.P. Pharmacological changes in dopaminergic systems induced by long term administration of amantadine. Eur J Pharmacol 1985, 110, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dineley, K.T.; Pandya, A.A.; Yakel, J.L. Nicotinic ACh receptors as therapeutic targets in CNS disorders. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2015, 36, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancesario, G.; Morrone, L.A.; D’Angelo, V.; Castelli, V.; Ferrazzoli, D.; Sica, F.; Martorana, A.; Sorge, R.; Cavaliere, F.; Bernardi, G.; et al. Levodopa-induced dyskinesias are associated with transient down-regulation of cAMP and cGMP in the caudate-putamen of hemiparkinsonian rats: reduced synthesis or increased catabolism? Neurochem Int 2014, 79, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerzon, K.; Krumkalns, E.V.; Brindle, R.L.; Marshall, F.J.; Root, M.A. The adamantyl group in medicinal agents. I. Hypoglycemic N- arylsulfonyl-N’-adamantylureas. J Med Chem 1963, 6, 760–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maj, J.; Sowinska, H.; Baran, L.; Sarnek, J. Pharmacological effects of 1,3-dimethyl-5-aminoadamantane, a new adamantane derivative. Eur J Pharmacol 1974, 26, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, R.S.; England, A.C., Jr.; Poskanzer, D.C.; Young, R.R. Amantadine in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. JAMA 1969, 208, 1168–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterworth, R.F. Amantadine for the Treatment of Traumatic Brain Injury and its Associated Cognitive and Neurobehavioural Complications. Journal of Pharmacology and Pharmaceutical Research 2020, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Gualtieri, T.; Chandler, M.; Coons, T.B.; Brown, L.T. Amantadine: a new clinical profile for traumatic brain injury. Clin Neuropharmacol 1989, 12, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uitti, R.J.; Rajput, A.H.; Ahlskog, J.E.; Offord, K.P.; Ho, M.M.; Prasad, M.; Rajput, A.; Basran, P. Amantadine treatment is an independent predictor of improved survival in parkinsonism. Can J Neurol Sci 1993, 20 (Suppl. 4), S235. [Google Scholar]

- Khasanova, D.R.; Saikhunov, M.V.; Kitaeva, E.A.; Khafiz’ianova, R.; Islaamov, R.R.; Demin, T.V. [Amantadine sulfate (PK-Merz) in the treatment of ischemic stroke: a clinical-experimental study]. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova 2009, 109, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Brison, E.; Jacomy, H.; Desforges, M.; Talbot, P.J. Novel treatment with neuroprotective and antiviral properties against a neuroinvasive human respiratory virus. J Virol 2014, 88, 1548–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quarato, G.; Scrima, R.; Ripoli, M.; Agriesti, F.; Moradpour, D.; Capitanio, N.; Piccoli, C. Protective role of amantadine in mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress mediated by hepatitis C virus protein expression. Biochem Pharmacol 2014, 89, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rejdak, K.; Grieb, P. Adamantanes might be protective from COVID-19 in patients with neurological diseases: multiple sclerosis, parkinsonism and cognitive impairment. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2020, 42, 102163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterworth, R.F. Amantadine, Parkinson’s Disease and COVID-19. Covid perspect res & rev 2020, 2020, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sommerauer, C.; Rebernik, P.; Reither, H.; Nanoff, C.; Pifl, C. The noradrenaline transporter as site of action for the anti-Parkinson drug amantadine. Neuropharmacology 2012, 62, 1708–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenk, G.L.; Danysz, W.; Mobley, S.L. MK-801, memantine and amantadine show neuroprotective activity in the nucleus basalis magnocellularis. Eur J Pharmacol 1995, 293, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, P.; Altagracia, M.; Kravzov, J.; Rios, C. Amantadine increases striatal dopamine turnover in MPTP-treated mice. Drug Dev Res 1993, 29, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, C.E.; Kraus, M.F.; Kline, A.E.; Ma, X.C.; Yan, H.Q.; Griffith, R.G.; Wolfson, B.M.; Marion, D.W. Amantadine improves water maze performance without affecting motor behavior following traumatic brain injury in rats. Restor Neurol Neurosci 1999, 14, 285–294. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Huang, X.J.; Van, K.C.; Went, G.T.; Nguyen, J.T.; Lyeth, B.G. Amantadine improves cognitive outcome and increases neuronal survival after fluid percussion traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurotrauma 2014, 31, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, L.; Ge, H.; Tang, J.; Fu, C.; Duanmu, W.; Chen, Y.; Hu, R.; Sui, J.; Liu, X.; Feng, H. Amantadine preserves dopamine level and attenuates depression-like behavior induced by traumatic brain injury in rats. Behavioural brain research 2015, 279, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleimeister, I.H.; Wolff, M.; Lam, T.R.; Brooks, D.M.; Patel, R.; Cheng, J.P.; Bondi, C.O.; Kline, A.E. Environmental enrichment and amantadine confer individual but nonadditive enhancements in motor and spatial learning after controlled cortical impact injury. Brain research 2019, 1714, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, E.Y.; Tsui, P.F.; Kuo, T.T.; Tsai, J.J.; Chou, Y.C.; Ma, H.I.; Chiang, Y.H.; Chen, Y.H. Amantadine ameliorates dopamine-releasing deficits and behavioral deficits in rats after fluid percussion injury. PloS one 2014, 9, e86354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okigbo, A.A.; Helkowski, M.S.; Royes, B.J.; Bleimeister, I.H.; Lam, T.R.; Bao, G.C.; Cheng, J.P.; Bondi, C.O.; Kline, A.E. Dose-dependent neurorestorative effects of amantadine after cortical impact injury. Neurosci Lett 2019, 694, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, S.; Mukherjee, A.; Sepulveda, S.; Becerra-Calixto, A.; Bravo-Vasquez, N.; Gherardelli, C.; Chavez, M.; Soto, C. Modeling Traumatic Brain Injury in Human Cerebral Organoids. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacino, J.T.; Whyte, J.; Bagiella, E.; Kalmar, K.; Childs, N.; Khademi, A.; Eifert, B.; Long, D.; Katz, D.I.; Cho, S.; et al. Placebo-controlled trial of amantadine for severe traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med 2012, 366, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnakers, C.; Hustinx, R.; Vandewalle, G.; Majerus, S.; Moonen, G.; Boly, M.; Vanhaudenhuyse, A.; Laureys, S. Measuring the effect of amantadine in chronic anoxic minimally conscious state. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 2008, 79, 225–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciurleo, R.; Bramanti, P.; Calabro, R.S. Pharmacotherapy for disorders of consciousness: are ‘awakening’ drugs really a possibility? Drugs 2013, 73, 1849–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loggini, A.; Tangonan, R.; El Ammar, F.; Mansour, A.; Goldenberg, F.D.; Kramer, C.L.; Lazaridis, C. The role of amantadine in cognitive recovery early after traumatic brain injury: A systematic review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2020, 194, 105815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, W.N.; Drew-Cates, J.; Wong, T.M.; Dombovy, M.L. Cognitive and behavioural efficacy of amantadine in acute traumatic brain injury: An initial double-blind placebo-controlled study. Brain Injury 1999, 13, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandler, M.C.; Barnhill, J.L.; Gualtieri, C.T. Amantadine for the agitated head-injury patient. Brain injury : [BI] 1988, 2, 309–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, M.F.; Maki, P. The combined use of amantadine and l-dopa/carbidopa in the treatment of chronic brain injury. Brain Injury 1997, 11, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, M.F.; Maki, P.M. Effect of amantadine hydrochloride on symptoms of frontal lobe dysfunction in brain injury: case studies and review. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences 1997, 9, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, M.F.; Smith, G.S.; Butters, M.; Donnell, A.J.; Dixon, E.; Yilong, C.; Marion, D. Effects of the dopaminergic agent and NMDA receptor antagonist amantadine on cognitive function, cerebral glucose metabolism and D2 receptor availability in chronic traumatic brain injury: a study using positron emission tomography (PET). Brain injury : [BI] 2005, 19, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickels, J.L.; Schneider, W.N.; Dombovy, M.L.; Wong, T.M. Clinical use of amantadine in brain injury rehabilitation. Brain Injury 1994, 8, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saniova, B.; Drobny, M.; Lehotsky, J.; Sulaj, M.; Schudichova, J. Biochemical and clinical improvement of cytotoxic state by amantadine sulphate. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2006, 26, 1475–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafonte, R.D.; Watanabe, T.; Mann, N.R. Amantadine : a potential treatment for the minimally conscious state. Brain Injury 1998, 12, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaele, R.; Nicoletti, G.; Vecchio, I.; Ruggieri, M.; Malaguarnera, M.; Rampello, L.; Brunetto, M.B.; Nicoletti, F. Use of amantadine in the treatment of the neurobehavioral sequelae after brain injury in elderly patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr Suppl 2002, 8, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saniova, B.; Drobny, M.; Kneslova, L.; Minarik, M. The outcome of patients with severe head injuries treated with amantadine sulphate. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2004, 111, 511–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whyte, J.; Katz, D.; Long, D.; DiPasquale, M.C.; Polansky, M.; Kalmar, K.; Giacino, J.; Childs, N.; Mercer, W.; Novak, P.; et al. Predictors of outcome in prolonged posttraumatic disorders of consciousness and assessment of medication effects: A multicenter study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005, 86, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.S.; Garmel, G.M. Improved neurological function after Amantadine treatment in two patients with brain injury. J Emerg Med 2005, 28, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafonte, R.D.; Lexell, J.; Cullen, N. Possible applications for dopaminergic agents following traumatic brain injury: part 2. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2001, 16, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafiee, S.; Ehteshami, S.; Moosazadeh, M.; Aghapour, S.; Haddadi, K. Placebo-controlled trial of oral amantadine and zolpidem efficacy on the outcome of patients with acute severe traumatic brain injury and diffuse axonal injury. Caspian J Intern Med 2022, 13, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimia, M.; Iranmehr, A.; Valizadeh, A.; Mirzaei, F.; Namvar, M.; Rafiei, E.; Rahimi, A.; Khadivi, A.; Aeinfar, K. A placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial of amantadine hydrochloride for evaluating the functional improvement of patients following severe acute traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg Sci 2023, 67, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosenbocus, S.; Chahal, R. Amantadine: A Review of Use in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013, 22, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Green, L.B.; Hornyak, J.E.; Hurvitz, E.A. Amantadine in pediatric patients with traumatic brain injury: a retrospective, case-controlled study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2004, 83, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beers, S.R.; Skold, A.; Dixon, C.E.; Adelson, P.D. Neurobehavioral effects of amantadine after pediatric traumatic brain injury: a preliminary report. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2005, 20, 450–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, P.D.; Blackman, J.A.; Mabry, J.L.; Buck, M.L.; Gurka, M.J.; Conaway, M.R. Dopamine agonist therapy in low-response children following traumatic brain injury. J Child Neurol 2006, 21, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, M.A.; Vargus-Adams, J.N.; Michaud, L.J.; Bean, J. Effects of amantadine in children with impaired consciousness caused by acquired brain injury: a pilot study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2009, 88, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, F.M.; Bickett, A.K.; Norton, J.H.; Pershad, R. Effectiveness of amantadine hydrochloride in the reduction of chronic traumatic brain injury irritability and aggression. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2014, 29, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, F.M.; Sherer, M.; Malec, J.F.; Zafonte, R.D.; Whitney, M.; Bell, K.; Dikmen, S.; Bogner, J.; Mysiw, J.; Pershad, R.; et al. Amantadine Effect on Perceptions of Irritability after Traumatic Brain Injury: Results of the Amantadine Irritability Multisite Study. Journal of neurotrauma 2015, 32, 1230–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, M.J.; Caliendo, E.; Lowder, R.; Watson, W.D.; Kurowski, B.; Baum, K.T.; Blackwell, L.S.; Koterba, C.H.; Hoskinson, K.R.; Tlustos, S.J.; et al. Prescribing Patterns of Amantadine During Pediatric Inpatient Rehabilitation After Traumatic Brain Injury: A Multicentered Retrospective Review From the Pediatric Brain Injury Consortium. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2022, 37, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molteni, E.; Canas, L.D.S.; Briand, M.M.; Estraneo, A.; Font, C.C.; Formisano, R.; Fufaeva, E.; Gosseries, O.; Howarth, R.A.; Lanteri, P.; et al. Scoping Review on the Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment of Pediatric Disorders of Consciousness. Neurology 2023, 101, e581–e593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, S.; Colantonio, A.; Santaguida, P.L.; Paton, T. Amantadine to enhance readiness for rehabilitation following severe traumatic brain injury. Brain injury : [BI] 2005, 19, 1197–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasivash, R.; Valizade Hasanloei, M.A.; Kazempour, A.; Mahdkhah, A.; Shaaf Ghoreishi, M.M.; Akhavan Masoumi, G. The Effect of Oral Administration of Amantadine on Neurological Outcome of Patients With Diffuse Axonal Injury in ICU. J Exp Neurosci 2019, 13, 1179069518824851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalaenovi, H.; Fattahi, A.; Koohpayehzadeh, J.; Khodadost, M.; Fatahi, N.; Taheri, M.; Azimi, A.; Rohani, S.; Rahatlou, H. The effects of amantadine on traumatic brain injury outcome: a double-blind, randomized, controlled, clinical trial. Brain injury : [BI] 2018, 32, 1050–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramish, J.A.; Kopp, B.J.; Patanwala, A.E. Effect of Amantadine on Agitation in Critically Ill Patients With Traumatic Brain Injury. Clinical neuropharmacology 2017, 40, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, F.M.; Sherer, M.; Malec, J.F.; Zafonte, R.D.; Dikmen, S.; Bogner, J.; Bell, K.R.; Barber, J.; Temkin, N. Amantadine Did Not Positively Impact Cognition in Chronic Traumatic Brain Injury: A Multi-Site, Randomized, Controlled Trial. Journal of neurotrauma 2018, 35, 2298–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passman, J.N.; Cleri, N.A.; Saadon, J.R.; Naddaf, N.; Gilotra, K.; Swarna, S.; Vagal, V.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Wong, J.; et al. In-Hospital Amantadine Does Not Improve Outcomes After Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: An 11-Year Propensity-Matched Retrospective Analysis. World Neurosurg 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeMarchi, R.; Bansal, V.; Hung, A.; Wroblewski, K.; Dua, H.; Sockalingam, S.; Bhalerao, S. Review of awakening agents. Can J Neurol Sci 2005, 32, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawyer, E.; Mauro, L.S.; Ohlinger, M.J. Amantadine enhancement of arousal and cognition after traumatic brain injury. Ann Pharmacother 2008, 42, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anghinah, R.; Amorim, R.L.O.; Paiva, W.S.; Schmidt, M.T.; Ianof, J.N. Traumatic brain injury pharmacological treatment: recommendations. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2018, 76, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plantier, D.; Luaute, J. Drugs for behavior disorders after traumatic brain injury: Systematic review and expert consensus leading to French recommendations for good practice. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2016, 59, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacino, J.T.; Katz, D.I.; Schiff, N.D.; Whyte, J.; Ashman, E.J.; Ashwal, S.; Barbano, R.; Hammond, F.M.; Laureys, S.; Ling, G.S.F.; et al. Practice Guideline Update Recommendations Summary: Disorders of Consciousness: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology; the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine; and the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2018, 99, 1699–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponsford, J.; Velikonja, D.; Janzen, S.; Harnett, A.; McIntyre, A.; Wiseman-Hakes, C.; Togher, L.; Teasell, R.; Kua, A.; Patsakos, E.; et al. INCOG 2.0 Guidelines for Cognitive Rehabilitation Following Traumatic Brain Injury, Part II: Attention and Information Processing Speed. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2023, 38, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargus-Adams, J.N.; McMahon, M.A.; Michaud, L.J.; Bean, J.; Vinks, A.A. Pharmacokinetics of amantadine in children with impaired consciousness due to acquired brain injury: preliminary findings using a sparse-sampling technique. PM R 2010, 2, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, C.C.; Collins, M.; Lovell, M.; Kontos, A.P. Efficacy of amantadine treatment on symptoms and neurocognitive performance among adolescents following sports-related concussion. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2013, 28, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghate, P.S.; Bhanage, A.; Sarkar, H.; Katkar, A. Efficacy of Amantadine in Improving Cognitive Dysfunction in Adults with Severe Traumatic Brain Injury in Indian Population: A Pilot Study. Asian J Neurosurg 2018, 13, 647–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Ma, L.; Yang, J. Persistent vegetative state after severe cerebral hemorrhage treated with amantadine: A retrospective controlled study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020, 99, e21822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avecillas-Chasin, J.M.; Barcia, J.A. Effect of amantadine in minimally conscious state of non-traumatic etiology. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2014, 156, 1375–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danielczyk, W. Twenty-five years of amantadine therapy in Parkinson´s disease. J Neural Transm 1995, 46 (Suppl.), 399–405. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Ji, X.; Li, H.; Liang, J. In Vivo DMPK Report - Amantadine. PK_20201211_WD_1; 2021; pp. 1–8. Unpublished work.

| Reference | Dose, treatment duration | Study design, | Clinical measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [150] | 50–200 mg/day BID |

Case Series Acute inpatient rehabilitation following brain injuries. N=12 |

Functional, neurobehavioral and cognitive status (e.g., attention, concentration, alertness, arousal, reaction time, agitation, anxiety) | Improvements in attention and concentration, alertness, arousal, processing time, psychomotor speed, mobility, vocalization, agitation, anxiety, and participation in therapy. |

| [147,148] | 25–400 mg/day | Case Series TBI N=7 |

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Test for Severe Impairment; Clock Drawing Test; The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test; Hopkins Attention Screening Test; The Brief Test of Attention; verbal fluency tests; The Trail Making Test; Boston Naming Test | All patients had significant frontal lobe dysfunction from TBI, and 4 were “responders” while 3 were “non-responders” to amantadine treatment, with improvements in alertness, attention, executive function, cognition, speech, behavior, mood, motivation, motor abilities and psychomotor speed, as well as less dyscontrol. |

| [145] | 50-150 mg BID over 2 weeks | RCT, Crossover TBI N=10 2 weeks on AMH, 2 weeks wash out, 2 weeks on placebo |

Neurobehavioural Rating Score (NRS) Orientation, memory, attention, executive Rate of patients’ cognitive recovery |

Amantadine had no effect on the rate of patients’ cognitive recovery. Results limited by small sample size, heterogeneous population, acute time course, and limited study power and high drop-out rate. |

| [53] | 200 mg/day over 6 weeks | RCT, Crossover Acute TBI N=35 6 weeks on AMH, 6 weeks on placebo |

Agitated Behavioural Scale (ABS); MMSE; Disability Rating Scale (DRS); GOS; and Functional Independence Measure (FIM-cog) scale; Galveston Orientation and Amnesia Test (GOAT) | Significant improvements in the MMSE, DRS, GOS, and FIM cognitive scale in both groups of patients recovering from acute TBI during the first 6 weeks of the study, but only in the amantadine-treatment group during the second 6 weeks. However, the groups had similar functional levels after the study had finished. Amantadine was safe in the study population. |

| [153] | up to 150 mg BID | RCT, crossover Brain injuries N=6 |

Attention and concentration, fatigue | Amantadine improved attention and concentration, and reduced fatigue. |

| [161] | 100 mg BID to 400 mg QD | Case Control, Retrospective TBI (pediatric) N = 118 (amantadine N=54) |

Ranchos Los Amigos (RLA) | Amantadine-treated subjects had a greater improvement in their RLA level during their admission. Subjective improvements noted in most patients administered amantadine. Side effects were minimal and resolved when treatment was reduced. |

| [162] | up to 150 mg/d (<10 y/o) or 200 mg/d (>10 y/o) |

RCT (BUT: no placebo) TBI (pediatric subjects) N=27 (amantadine N=17); Only per protocol set analysed: N=13 (amantadine N=9) |

Cognition | Improvements with amantadine in cognitive testing when compared to age- and severity-matched TBI control patients observed in those ≤2 years post injury. The results limited since just per-protocol analysis was used. |

| [169] | 200 mg BID | Retrospective Cohort Severe TBI N=123 (amantadine N=28) |

GCS and somatosensory evoked potentials | Amantadine failed to shorten the time to emerge from coma. |

| [149] | 400 mg/day | RCT, Open label, Crossover TBI N=22 |

Executive function | Amantadine improved performance on executive function tests, correlated with a significant increase in left prefrontal cortex glucose metabolism in the first 6 male subjects enrolled. |

| [155] | Not provided | Cohort TBI N=124 (amantadine N=47) |

DRS | Amantadine significantly improved recovery |

| [163] | 100 mg BID | RCT TBI N=10 (amantadine N=6) |

Coma Near Coma (CNC) scale, DRS, and Western NeuroSensory Stimulation Profile | Weekly rate of change in the CNC scale, DRS, and Western NeuroSensory Stimulation Profile was significantly greater with amantadine or pramipexole than without and slowed 6 weeks after treatment termination). |

| [151] | 200 mg BID (i.v.) | RCT, Open Label Closed head injury N=32 (amantadine N=18) |

GCS, survival, biochemical parameters: glycaemia, malondialdehyde (MDA; marker of lipid peroxidation), beta-carotene, total SH groups | Amantadine-treated patients had reduced MDA and increased Beta-carotene (antioxidant), as well as improved survival, after only 1 week of treatment. |

| [181] | 400 mg/day | RCT, crossover Brain injuries in pediatric population N=7 |

CNC Scale or Coma Recovery Scale – Revised (CRS-R) | Amantadine was well tolerated, but had no significant effect on CNC Scale or CRS-R. |

| [141] | 200 mg BID, 4 weeks | RCT, crossover Post-traumatic disorders of consciousness Patients in the vegetative state or minimally conscious state 4-16 weeks after severe TBI N=184 (amantadine N=87) |

DRS – primary outcome measure CRS-R |

Amantadine accelerated the rate of functional recovery during active treatment. The rate of improvement decreased during a 2-week wash-out period in the amantadine more than in placebo group, with no difference in DRS and CRS-R scores at 6 weeks. Amantadine did not increase the incidence of adverse effects. |

| [182] | 100 mg BID | Case Control, Retrospective Subjects with history of head concussion N= 50 (amantadine N=25) |

Verbal memory, reaction time | After 3–4 weeks, amantadine-treated patients made significantly greater improvements in verbal memory and reaction time, as well as reported fewer persistent post-concussion symptoms, when compared to matched controls (by age, sex, and concussion history). |

| [165] | 100 mg BID, 4 weeks | RCT TBI N=76 (amantadine N=38) |

Neuropsychiatric Inventory - Irritability (NPI-I); Neuropsychiatric Inventory - Aggression (NPI-A) | Among patients with moderate-severe irritability (≥6 months following TBI), 4 weeks of amantadine significantly improved the frequency and severity of irritability and aggression and was safe. |

| [166] | 100 mg BID | RCT TBI N=118 (amantadine N=61) |

Aggression, anger | Among patients (≥6 months post-TBI) with moderate-to-severe aggression, amantadine significantly reduced aggression, with no beneficial effect on anger. |

| [166] | 100 mg BID | RCT TBI N=168 (amantadine N=82) |

NPI | Because of a very large placebo effect, amantadine did not significantly improve irritability (in patients with moderate-severe irritability, who suffered TBI ≥6 months prior to enrollment). |

| [172] | 100 mg BID | Cohort, retrospective TBI N=139 (amantadine N=70) |

Agitation, length of stay in intensive care unit (ICU) | Agitation was significantly more prevalent in the amantadine group. Patients given amantadine had longer ICU lengths of stay and received more opioids. |

| [171] | 100 mg BID | RCT severe TBI N=40 (amantadine N=19) |

GCS | Patients having received amantadine had a faster rate of improvement in their GCS scores during the first week of treatment. No functional differences observed at 6-month follow-up. |

| [183] | 100 mg BID over 4 weeks | Observational severe TBI (at 2 months orally or through enteral feeding tube) |

Full Outline of Unresponsiveness (FOUR) score, DRS, GOS during 4 weeks of treatment and 2 weeks posttreatment was assessed. | Improvement of cognitive function over 4-weeks of treatment interval as shown by significant improvement on FOUR score, DRS, and GOS. Recovery speed slowed down after discontinuation of amantadine. Convulsions (adverse effect) occurred in 8 out of 50 patients (5 discontinued). |

| [173] | 100 mg BID | RCT TBI (at least 6 months prior to enrollment, with moderate-severe irritability) N=119 (amantadine N=59) |

Cognitive battery, irritability | No differences between groups were observed after 60 days of treatment, but the placebo responses were high. Cognitive battery baseline scores for the treatment group were higher, increasing the group’s susceptibility to ceiling effects. At day 28, the mean change for the placebo group was greater (more room for improvement?). |

| [170] | 100 mg BID increased to 200 mg BID within 3 days |

Double-blind placebo-controlled trial Acute TBI (patients admitted to the intensive care unit, ICU) N=66 (amantadine N=33) |

GCS, GOS duration of mechanical ventilation length of hospitalization fatality at the hospital mortality in patients. |

No significant differences between amantadine and placebo on the GCS, GOS, duration of mechanical ventilation and hospitalization, fatality at the hospital. Statistical differences were found on GCS and GOS in discharged and deceased patients. |

| [158] | 200 mg/day | RCT (with parallel placebo and zolpidem groups) Acute severe TBI N=66 (amantadine N=22) |

GCS, GOS | The improvement on GCS and GOS was non-significantly better with amantadine than with zolpidem or placebo. No clinically significant adverse events were observed. |

| [167] | 0.7 - 13.5 mg/kg/d; up to 400 mg/d. | N = 234 children and young adults (2 mo - 21 y) TBI, inpatient rehabilitation. (amantadine N= (21%) patients, 0.9 - 20 years) |

Retrospective review of behavioral descriptions of function based on, e.g., Coma Recovery Scale-Revised (CRS-R) and post-traumatic amnesia (PTA) as measured using, e.g., Children’s Orientation and Amnesia Test | Almost half of the patients admitted with a disorder of consciousness (median age 11.6 years) were treated with amantadine Nausea/abdominal discomfort (N=3) and agitation (N=3) were the most commonly reported adverse effects (8 patients; 16%). None of the adverse events were reported as serious |

| [159] | 100 mg BID for 14 days, then 150 mg BID for 7 days, then 200 mg BID for 21 days |

RCT (triple-blind, placebo-controlled Severe TBI N= 57 (amantadine N=29) |

GOS, DRS | On DRS, change from baseline was significantly (p = 0.015) better with amantadine (10.88 ± 5.24) than with placebo (8.04 ± 4.07). No significant difference between these groups was found for GOS |

| [174] | tbd | Retrospective Severe TBI amantadine N =60 control N=344 |

GCS GOS-Extended Score (GCS-ES) Length of stay Mortality Recovery of command following Days to command following |

No difference between these two groups in terms of mortality, rates of command following, or percentage of patients with severe (3-8) Glasgow Coma Scale scores at discharge. No difference in adverse events. Amantadine group was less likely to have a favorable recovery, had a longer length of hospital stay and a longer time to command following. |

| Equimolar doses | Amantadine Sulphate | Amantadine hydrochloride | Statistical analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| T½ (h) | 2.07±0.62 | 1.67±0.41 | Student T-test; P=0.001 |

| tmax (h) | 1.43±1.02 | 0.75±0.38 | NS |

| Cmax (ng/l) | 4045±689.35 | 3911±427.11 | NS |

| AUC 0-∞ (ng*h/ml) | 22226.88±4387.05 | 11690±1366.33 | Student T-test; P<0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).