Submitted:

06 May 2024

Posted:

08 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

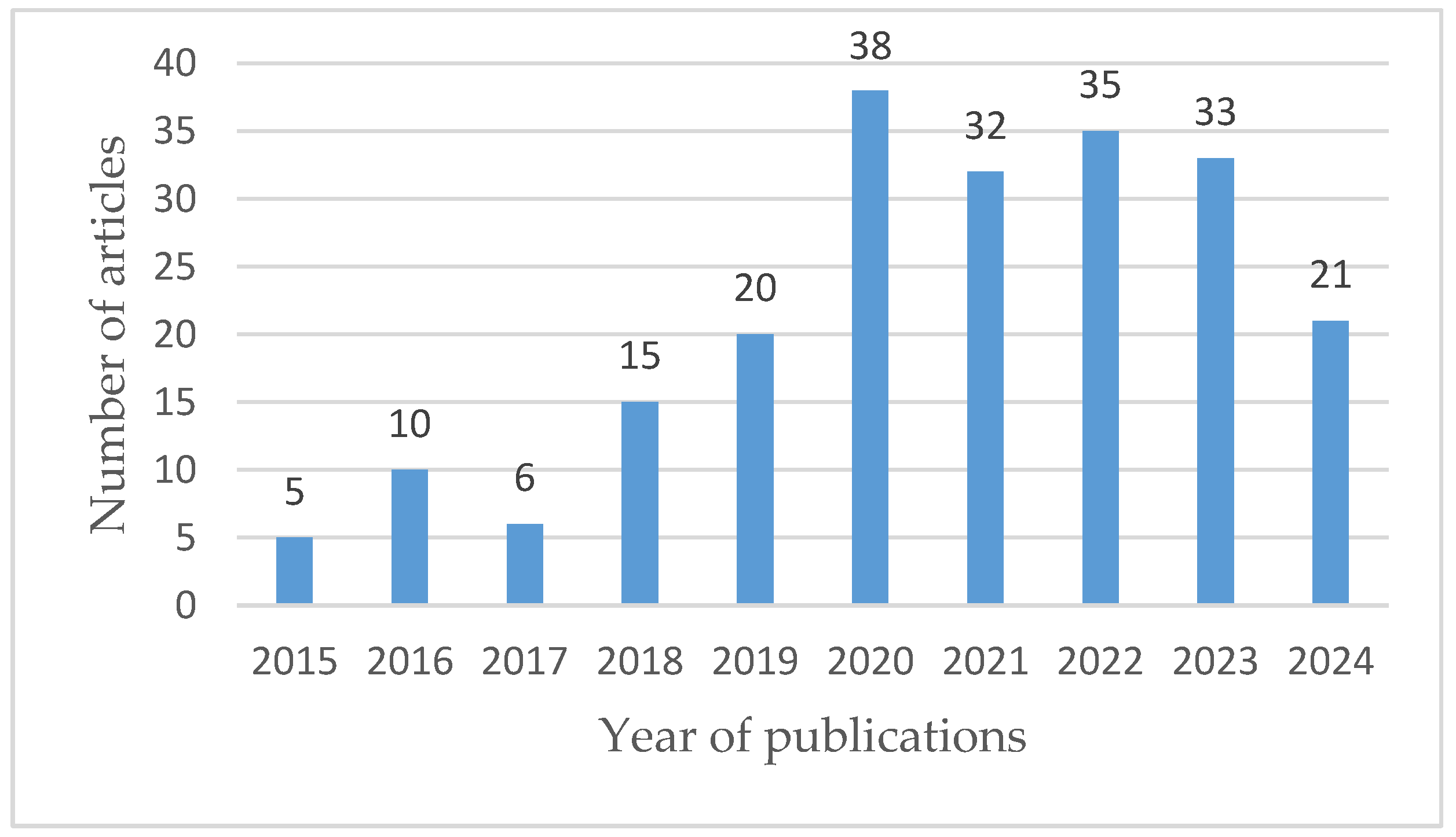

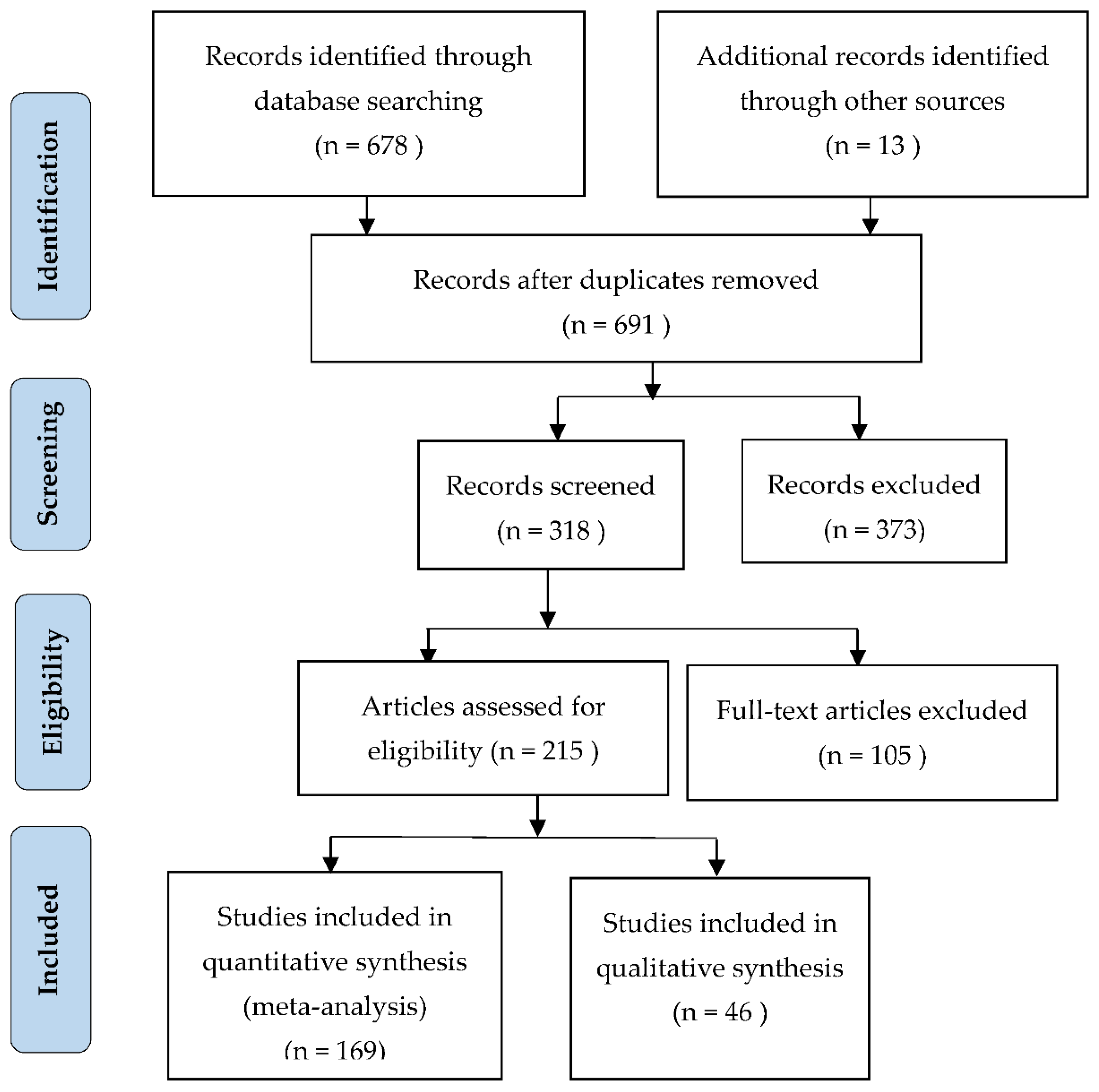

2. Materials and Methods

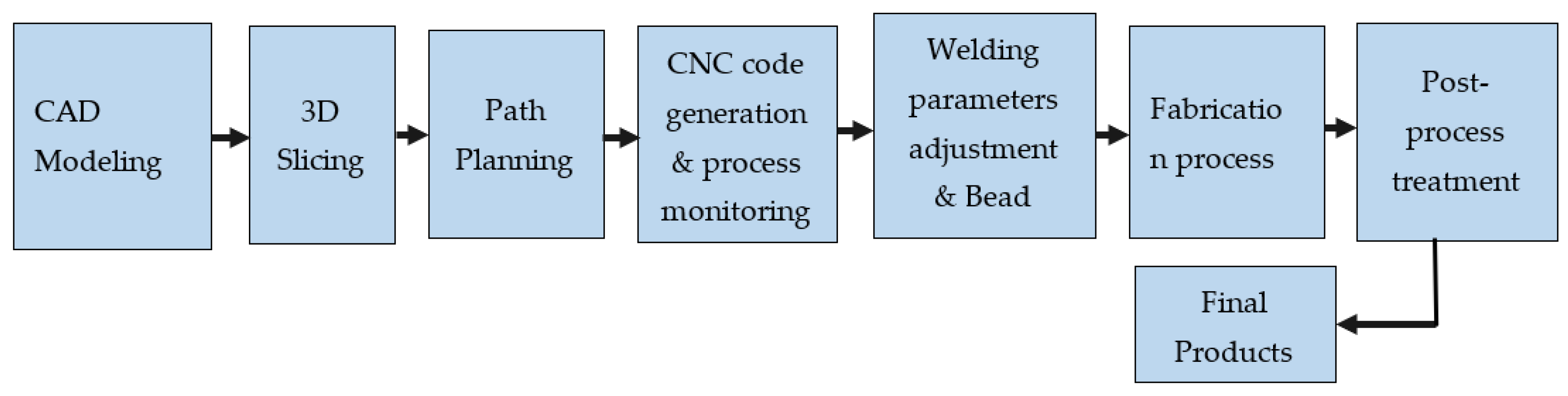

3. Overview of WAAM of Process and Products

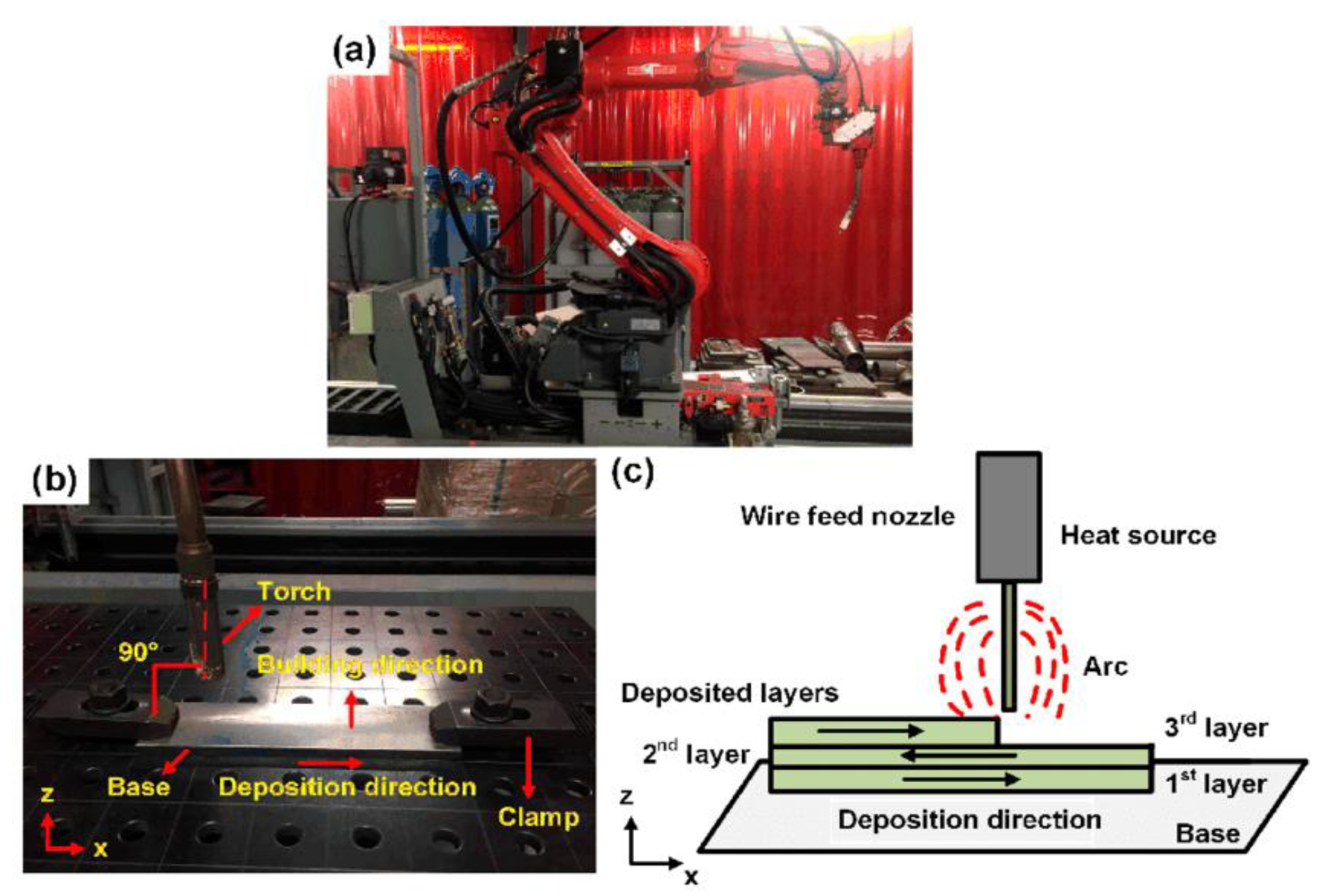

3.1. A Robotic System for WAAM

3.2. Residual Stress in WAAMed Products

3.3. Residual Stress Measurement Methods

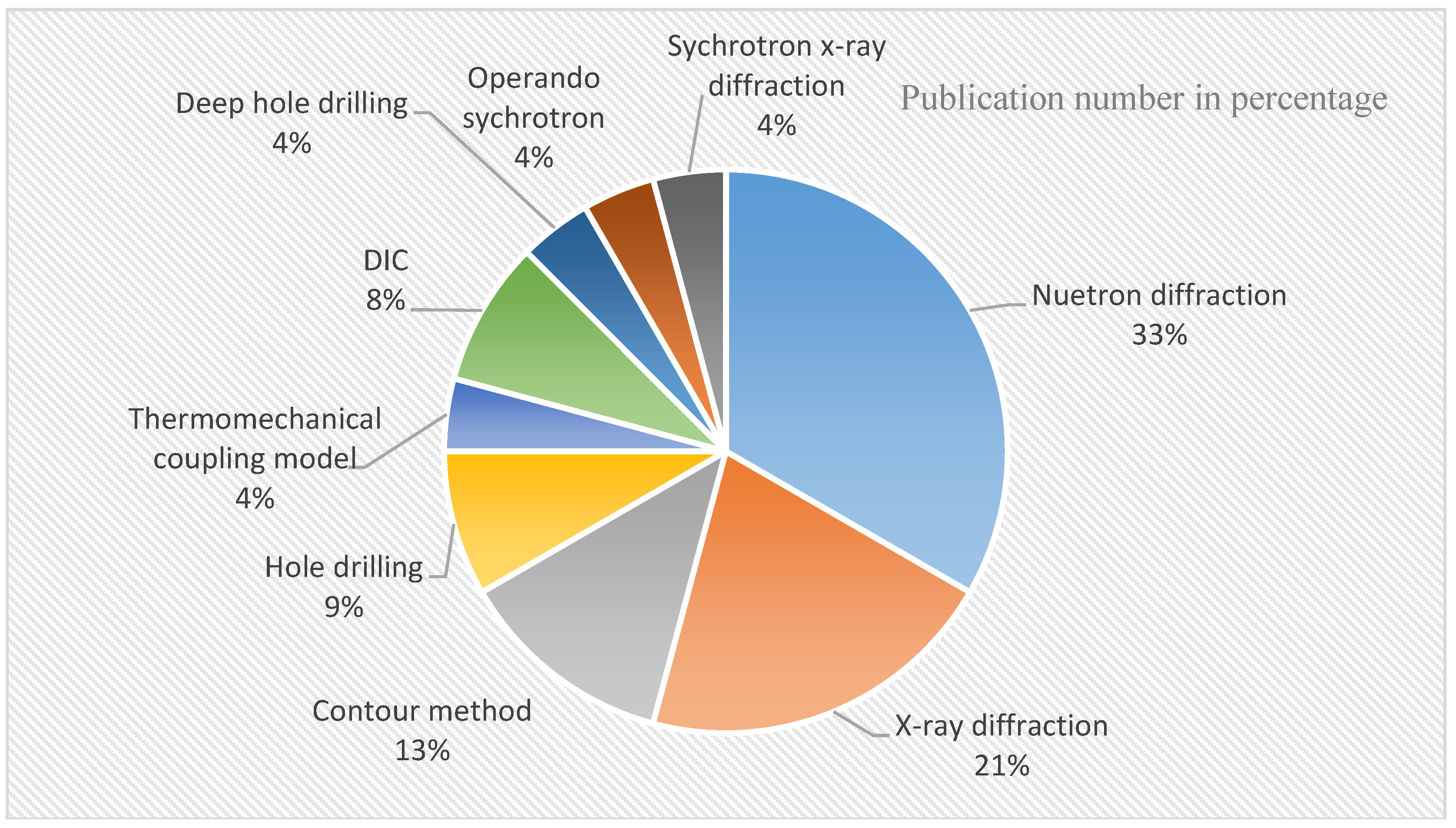

3.3.1. Experimental Methods for RS Measurement in WAAM Parts

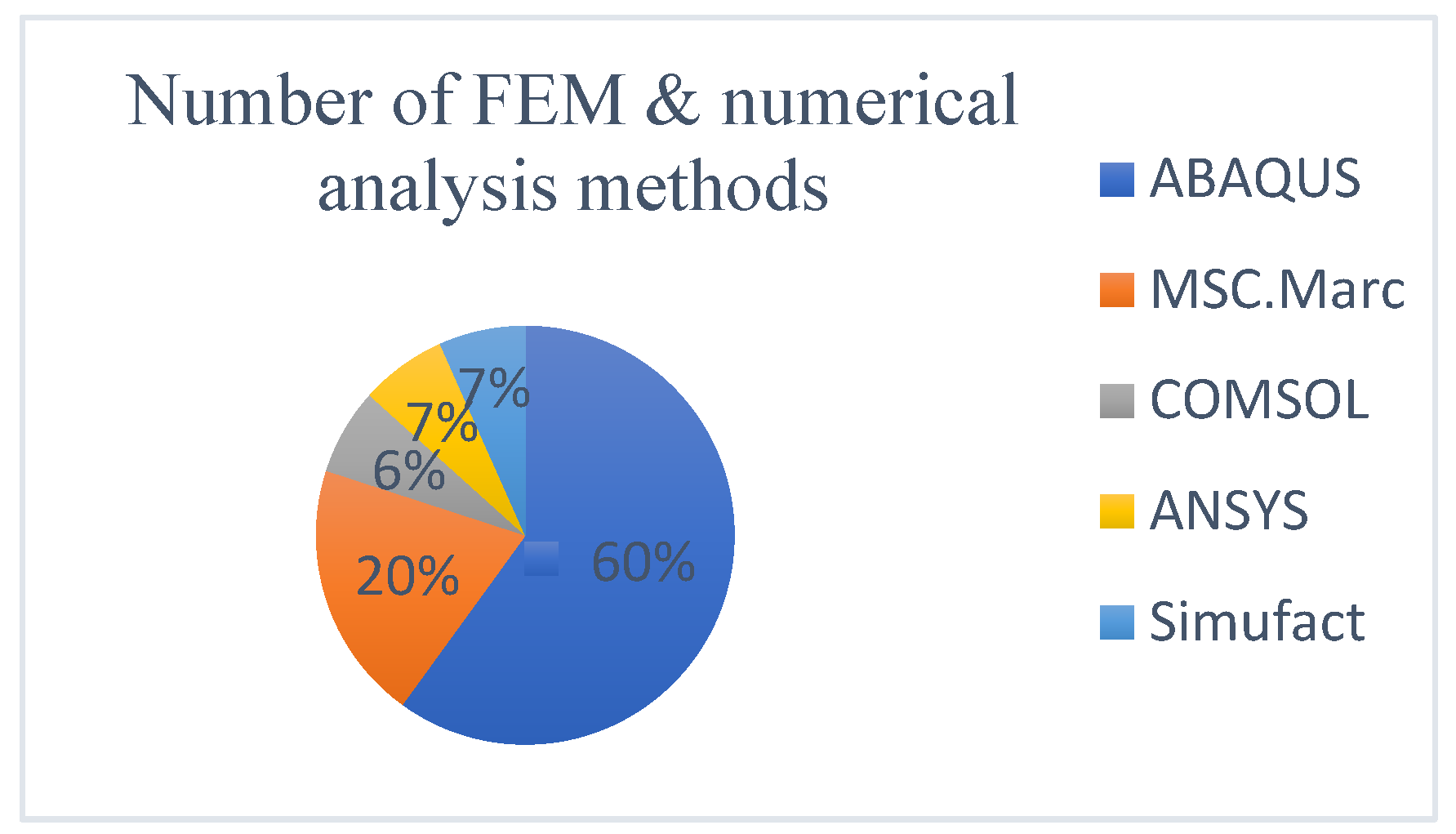

3.3.2. Numerical Analysis of RS in WAAM Products

3.4. Factors Influencing RS in WAAM

4. Impact of RS on Mechanical Properties in WAAM Components

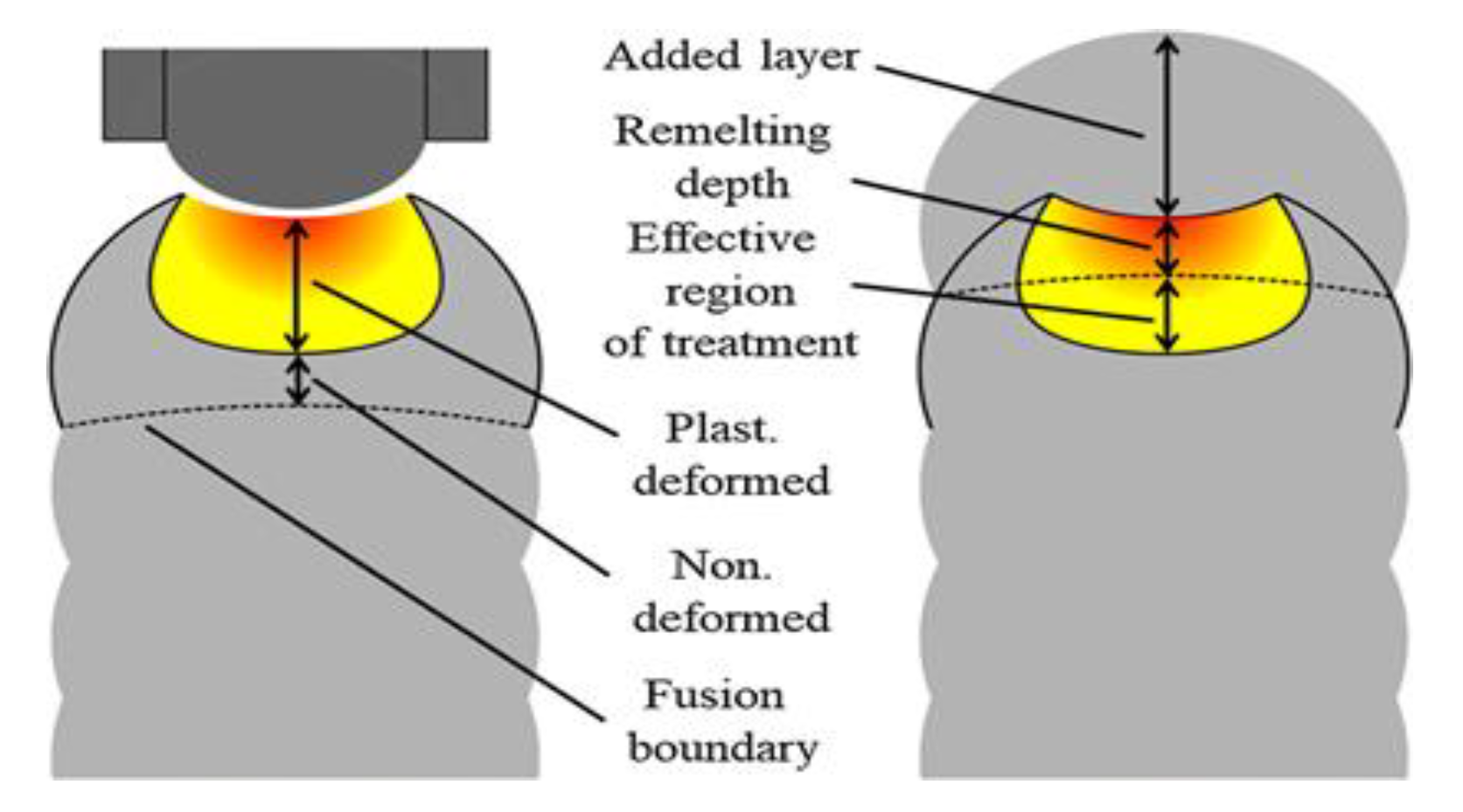

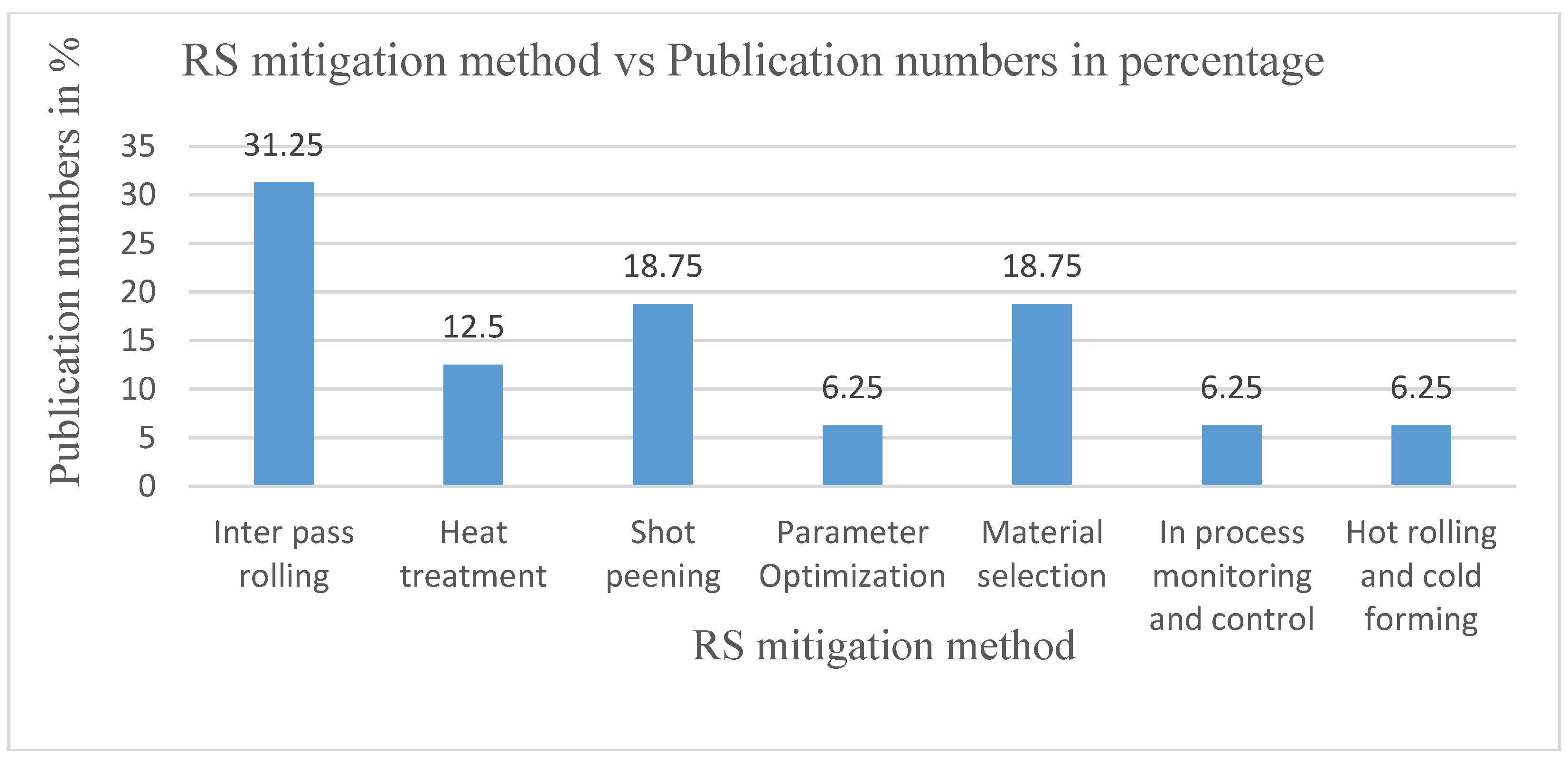

5. Mitigation Strategies for RS in WAAM and Practical Applications

6. Discussion

6.1. Challenges and Limitations

6.2. Future Directions

| (1) Non-destructive methods | ▪ Ultrasonic Waves ▪ Magnetic Barkhausen |

| (2) Semi-destructive methods | ▪ Ring Core ▪ Deep Hole method |

| (3) Destructive methods | ▪ Bridge Curvature ▪ Sectioning Techniques ▪ Slitting or Crack Compliance |

- Most researchers used frequently non-destructive methods like XRd, ND, and some other semi-destructive and fully destructive techniques of measuring RS in components’ WAAM. Thus, future studies can perform those techniques listed above.

- In the future, researchers should determine the most suitable quantity and varieties of shielding gas, in addition to other process and input parameters, throughout the WAAM processes.

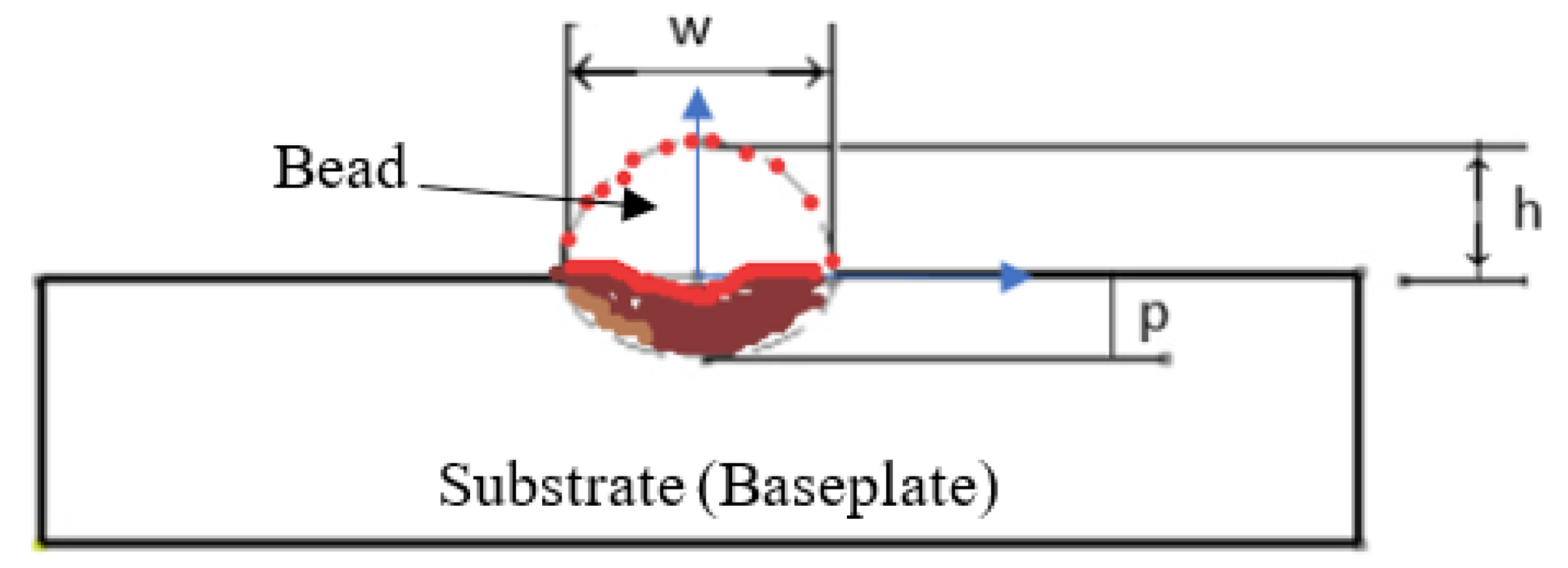

- As explained in Section 5, the mathematical formula provides a particular formation of bead profile and the relationship of wire diameter with the width and thickness (height) of beads. The result of variation in wire diameter, the thickness, and width of beads can vary consequently heat distribution of the process results in a variation of RS in WAAM parts. Therefore, the future researcher can focus on a variety of wire diameters to reduce RS in WAAM parts with less diameter of wire diameter.

- Materials weld-ability depends on their physical properties that influence the accumulation of RS in products of WAAM. In the future, further research endeavors should aim to investigate these physical properties of materials which are listed in Table 3, and other robot adjustable effects to RS fabricated components through WAAM.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bhuvanesh Kumar M, Sathiya P, Senthil SM. A critical review of wire arc additive manufacturing of nickel-based alloys: principles, process parameters, microstructure, mechanical properties, heat treatment effects, and defects. J Brazilian Soc Mech Sci Eng. 2023; Volume 45, pp. 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Tangestani R, Farrahi GH, Shishegar M, Aghchehkandi BP, Ganguly S, Mehmanparast A. Effects of Vertical and Pinch Rolling on Residual Stress Distributions in Wire and Arc Additively Manufactured Components. J Mater Eng Perform. 2020; Volume 29, pp. 2073–84. [CrossRef]

- Derekar KS. Aspects of wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM) of alumnium alloy 5183. Award Inst Coventry Univ. 2020; pp. 1–227.

- Rodrigues TA, Duarte V, Miranda RM, Santos TG, Oliveira JP. Current status and perspectives on wire and arc additive manufacturing (WAAM). Materials. 2019; Volume 12, pp. 1121. [CrossRef]

- Laghi V, Palermo M, Gasparini G, Veljkovic M, Trombetti T. Assessment of design mechanical parameters and partial safety factors for Wire-and-Arc Additive Manufactured stainless steel. Eng Struct. 2020; Volume 225, pp. 111314. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham CR, Flynn JM, Shokrani A, Dhokia V, Newman ST. Invited review article: Strategies and processes for high quality wire arc additive manufacturing. Addit Manuf. 2018; Volume 22, pp. 672–86. [CrossRef]

- Klobčar D, Baloš S, Bašić M, Djurić A, Lindič M, Ščetinec A. WAAM and Other Unconventional Metal Additive Manufacturing Technologies. Adv Technol Mater. 2020; Volume 45, pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Mathews R, Karandikar J, Tyler C, Smith S. Residual stress accumulation in large-scale Ti-6Al-4V wire-arc additive manufacturing. Procedia CIRP. 2024; Volume 121, pp. 180–5. [CrossRef]

- Wu B, Pan Z, van Duin S, Li H. Thermal Behavior in Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing: Characteristics, Effects and Control. Transactions on Intelligent Welding Manufacturing. Springer Singapore; 2019; pp. 3–18. [CrossRef]

- Williams SW, Martina F, Addison AC, Ding J, Pardal G, Colegrove P. Wire + Arc additive manufacturing. Vol. 32, Materials Science and Technology (United Kingdom). 2016; pp. 641–647.

- Jimenez X, Dong W, Paul S, Klecka MA, To AC. Residual Stress Modeling with Phase Transformation for Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing of B91 Steel. Jom. 2020; Volume 72, pp. 4178–86. [CrossRef]

- Jin W, Zhang C, Jin S, Tian Y, Wellmann D, Liu W. Wire arc additive manufacturing of stainless steels: A review. Appl Sci. 2020; Volume 10, pp. 1563. [CrossRef]

- Huang W, Wang Q, Ma N, Kitano H. Distribution characteristics of residual stresses in typical wall and pipe components built by wire arc additive manufacturing. J Manuf Process. 2022; Volume 82, pp. 434–47. [CrossRef]

- Mohan Kumar S, Rajesh Kannan A, Pravin Kumar N, Pramod R, Siva Shanmugam N, Vishnu AS, et al. Microstructural Features and Mechanical Integrity of Wire Arc Additive Manufactured SS321/Inconel 625 Functionally Gradient Material. J Mater Eng Perform. 2021; Volume 30, pp. 5692–703. [CrossRef]

- Kumar V, Singh A, Bishwakarma H, Mandal A. Simulation of Metallic Wire-Arc Additive Manufacturing (Waam) Process Using Simufact Welding Software. J Manuf Eng. 2023; Vlume 18, pp. 080–5. [CrossRef]

- Knezović N, Topić A. Wire and Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM) – A New Advance in Manufacturing., Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems. Springer International Publishing; 2019; Volume 42, pp. 65–71. [CrossRef]

- Costello SCA, Cunningham CR, Xu F, Shokrani A, Dhokia V, Newman ST. The state-of-the-art of wire arc directed energy deposition (WA-DED) as an additive manufacturing process for large metallic component manufacture. Int J Comput Integr Manuf. 2023; Vlume 36, pp. 469–510. [CrossRef]

- Barath Kumar MD, Manikandan M. Assessment of Process, Parameters, Residual Stress Mitigation, Post Treatments and Finite Element Analysis Simulations of Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing Technique. Metals and Materials International. The Korean Institute of Metals and Materials; 2022; Volume 28, pp. 54–111. [CrossRef]

- Ivántabernero, Paskual A, Álvarez P, Suárez A. Study on Arc Welding Processes for High Deposition Rate Additive Manufacturing. Procedia CIRP. 2018; Volume 68, pp. 358–62. [CrossRef]

- Shukla P, Dash B, Kiran DV, Bukkapatnam S. Arc behavior in wire arc additive manufacturing process. Procedia Manuf. 2020; Volume 48, pp. 725–9. [CrossRef]

- Zhao XF, Wimmer A, Zaeh MF. Experimental and simulative investigation of welding sequences on thermally induced distortions in wire arc additive manufacturing. Rapid Prototyp J. 2023; Volume 29, pp. 53–63. [CrossRef]

- Cambon C, Bendaoud I, Rouquette S, Soulié F. A WAAM benchmark: From process parameters to thermal effects on weld pool shape, microstructure and residual stresses. Mater Today Commun. 2022; Volume 33, pp. 104235. [CrossRef]

- Er C, Ganguly S, Xu X, Cabeza S, Coules H, Williams S. Study of residual stress and microstructural evolution in as-deposited and inter-pass rolled wire plus arc additively manufactured Inconel 718 alloy after ageing treatment. 2021; Volume 801, pp. 7346. [CrossRef]

- Hönnige JR, Colegrove PA, Ganguly S, Eimer E, Kabra S, Williams S. Control of Residual Stress and Distortion in Aluminium Wire + Arc Additive Manufacture with Rolling. Addit Manuf. 2018; Volume 22, pp. 775-783. [CrossRef]

- Schroepfer KWD, Wildenhain RS, Kannengiesser AHT, Hensel AKJ. Influence of the WAAM process and design aspects on residual stresses in high - strength structural steels. Weld World. 2023; Volume 67, pp. 987–96. [CrossRef]

- Geng R, Du J, Wei Z, Xu S, Ma N. Modelling and experimental observation of the deposition geometry and microstructure evolution of aluminum alloy fabricated by wire-arc additive manufacturing. J Manuf Process. 2021; Volume 64, pp. 369–78. [CrossRef]

- Klein T, Spoerk-Erdely P, Schneider-Broeskamp C, Oliveira JP, Abreu Faria G. Residual Stresses in a Wire and Arc-Directed Energy-Deposited Al–6Cu–Mn (ER2319) Alloy Determined by Energy-Dispersive High-Energy X-ray Diffraction. Metall Mater Trans A Phys Metall Mater Sci. 2024; Volume 55, pp. 736–44. [CrossRef]

- Ermakova A, Mehmanparast A, Ganguly S, Razavi N, Berto F. Investigation of mechanical and fracture properties of wire and arc additively manufactured low carbon steel components. Theor Appl Fract Mech. 2020;Volume 109, pp. 0–8. [CrossRef]

- Derekar KS. A review of wire arc additive manufacturing and advances in wire arc additive manufacturing of aluminium. Mater Sci Technol (United Kingdom). 2018; Volume 34, pp. 895–916. [CrossRef]

- Taşdemir A, Nohut S. An overview of wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM) in shipbuilding industry. Ships Offshore Struct. 2020; Volume 16, pp. 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Williams SW, Martina F, Addison AC, Ding J, Pardal G, Colegrove P. Wire + Arc additive manufacturing. Mater Sci Technol (United Kingdom). 2016; Volume 32, pp. 641–7.

- Müller J, Grabowski M, Müller C, Hensel J, Unglaub J, Thiele K, et al. Design and parameter identification of wire and arc additively manufactured (WAAM) steel bars for use in construction. Metals. 2019; Volume 9, pp. 725. [CrossRef]

- Abbaszadeh M, Hönnige JR, Martina F, Neto L, Kashaev N, Colegrove P, et al. Numerical Investigation of the Effect of Rolling on the Localized Stress and Strain Induction for Wire + Arc Additive Manufactured Structures. J Mater Eng Perform. 2019; Volume 28, pp. 4931–42. [CrossRef]

- Song SS, Chen J, Quan G, Ye J, Zhao Y. Numerical analysis and design of concrete-filled wire arc additively manufactured steel tube under axial compression. Eng Struct. 2024; Volume 301, pp. 117294. [CrossRef]

- Wu Q, Mukherjee T, De A, DebRoy T. Residual stresses in wire-arc additive manufacturing - Hierarchy of influential variables. Addit Manuf. 2020; Volume 35. pp. 101355. [CrossRef]

- Ding D, Pan Z, Cuiuri D, Li H. Wire-feed additive manufacturing of metal components: technologies, developments and future interests. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2015; Volume 81, pp. 465–81. [CrossRef]

- Jafari D, Vaneker THJ, Gibson I. Wire and arc additive manufacturing : Opportunities and challenges to control the quality and accuracy of manufactured parts. Mater Des. 2021; Volume 202, pp. 109471. [CrossRef]

- Wu B, Pan Z, Chen G, Ding D, Yuan L, Cuiuri D, et al. Mitigation of thermal distortion in wire arc additively manufactured Ti6Al4V part using active interpass cooling. Sci Technol Weld Join. 2019; Volume 24, pp. 484–94. [CrossRef]

- Rozaimi M, Yusof F. Research challenges, quality control and monitoring strategy for Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing. J Mater Res Technol. 2023; Volume 24, pp. 2769–94. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad B, Zhang X, Guo H, Fitzpatrick ME, Neto LMSC, Williams S. Influence of Deposition Strategies on Residual Stress in Wire + Arc Additive Manufactured Titanium Ti-6Al-4V. Metals. 2022; Volume 12, pp. 253. [CrossRef]

- Schönegger S, Moschinger M, Enzinger N. Computational welding simulation of a plasma wire arc additive manufacturing process for high-strength steel. Eur J Mater. 2024; Volume 4, pp. 2297051. [CrossRef]

- Qvale P, Njaastad EB, Bræin T, Ren X. A fast simulation method for thermal management in wire arc additive manufacturing repair of a thin-walled structure. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2024; Volume 132, pp. 1573–1583. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Suder W, Ding J, Williams S. The effect of wire size on high deposition rate wire and plasma arc additive manufacture of Ti-6Al-4V. 2021; Volume 288, pp. 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Gupta AK, Bansal H, Madan A. Study on CNC Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing process for Higher Deposition Rate and Mechanical Strength. 2022; Vlome 10, pp. 9695.

- Agustinus Ananda P. WAAM Application for EPC Company. MATEC Web Conf. 2019; Volume 269, pp. 05002. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Dong Z, Miao J, Liu H, Babkin A, Chang Y. Forming accuracy improvement in wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM): a review. Rapid Prototyp J. 2022; Volume 29, pp. 1355- 2546. [CrossRef]

- Chaurasia M, Sinha MK. Investigations on Process Parameters of Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM): A Review. Lect Notes Mech Eng. 2021; pp. 845–53. [CrossRef]

- Gowthaman PS, Jeyakumar S, Sarathchandra D. Effect of Heat Input on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of 316L Stainless Steel Fabricated by Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing. J Mater Eng Perform. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tomar B, Shiva S, Nath T. A review on wire arc additive manufacturing: Processing parameters, defects, quality improvement and recent advances. Mater Today Commun. 2022; Volume 31, pp. 103739. [CrossRef]

- Voropaev A, Korsmik R, Tsibulsky I. Features of filler wire melting and transferring in wire-arc additive manufacturing of metal workpieces. Materials. 2021; Volume 14, pp. 5077. [CrossRef]

- Chen C, He H, Zhou S, Lian G, Huang X, Feng M. Prediction of multi-bead profile of robotic wire and arc additive manufactured components recursively using axisymmetric drop shape analysis. Virtual Phys Prototyp. 2023; Volume 18, pp. 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Ayed A, Valencia A, Bras G, Bernard H, Michaud P, Balcaen Y, et al. Effects of WAAM Process Parameters on Metallurgical and Mechanical Properties of Ti-6Al-4V Deposits. Lect Notes Mech Eng. 2020; pp. 26–35. [CrossRef]

- Le VT, Si D, Khoa T, Paris H. Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal Wire and arc additive manufacturing of 308L stainless steel components : Optimization of processing parameters and material properties. Eng Sci Technol an Int J. 2021; Volume 24, pp. 1015–26. [CrossRef]

- Lin Z, Goulas C, Ya W, Hermans MJM. Microstructure and mechanical properties of medium carbon steel deposits obtained via wire and arc additive manufacturing using metal-cored wire. Metals. 2019; Volume 9, pp. 673. [CrossRef]

- Song GH, Lee CM, Kim DH. Investigation of path planning to reduce height errors of intersection parts in wire-arc additive manufacturing. Materials. 2021; Volume 14, pp. 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Z, Shen H, Liu B, Du W, Jin J, Lin J. Residual thermal stress prediction for continuous tool-paths in wire-arc additive manufacturing: a three-level data-driven method. Virtual Phys Prototyp. 2022; Volume 17, pp. 105–24. [CrossRef]

- Guo C, Li G, Li S, Hu X, Lu H, Li X, et al. Additive manufacturing of Ni-based superalloys: Residual stress, mechanisms of crack formation and strategies for crack inhibition. Nano Mater Sci. 2023; Volume 5, pp. 53–77. [CrossRef]

- Scotti FM, Teixeira FR, Silva LJ da, de Araújo DB, Reis RP, Scotti A. Thermal management in WAAM through the CMT Advanced process and an active cooling technique. J Manuf Process. 2020; Volume 57, pp. 23–35. [CrossRef]

- Ahsan MRU, Tanvir ANM, Ross T, Elsawy A, Oh MS, Kim DB. Fabrication of bimetallic additively manufactured structure (BAMS) of low carbon steel and 316L austenitic stainless steel with wire + arc additive manufacturing. Rapid Prototyp J. 2020; Volume 26, pp. 519–30. [CrossRef]

- Wu Q, Ma Z, Chen G, Liu C, Ma D, Ma S. Obtaining fine microstructure and unsupported overhangs by low heat input pulse arc additive manufacturing. J Manuf Process. 2017; Volume 27, pp. 198–206. [CrossRef]

- Doumenc G, Couturier L, Courant B, Paillard P, Benoit A, Gautron E, et al. Investigation of microstructure, hardness and residual stresses of wire and arc additive manufactured 6061 aluminium alloy To cite this version : HAL Id : hal-03827007. Materialia. 2022; Volume 25, pp. 101520. [CrossRef]

- Tröger J alexander, Hartmann S, Treutler K, Potschka A, Wesling V. Simulation-based process parameter optimization for wire arc additive manufacturing. Prog Addit Manuf. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nagallapati V, Khare VK, Sharma A, Simhambhatla S. Active and Passive Thermal Management in Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing. Metals. 2023; Volume 13, pp. 682. [CrossRef]

- Ahsan MRU, Seo GJ, Fan X, Liaw PK, Motaman S, Haase C, et al. Effects of process parameters on bead shape, microstructure, and mechanical properties in wire + arc additive manufacturing of Al0.1CoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy. J Manuf Process. 2021;Volume 68, pp. 1314–27. [CrossRef]

- He T, Yu S, Shi Y, Huang A. Forming and mechanical properties of wire arc additive manufacture for marine propeller bracket. J Manuf Process. 2020; Volume 52, pp. 96–105. [CrossRef]

- Su C, Chen X, Gao C, Wang Y. Effect of heat input on microstructure and mechanical properties of Al-Mg alloys fabricated by WAAM. Appl Surf Sci. 2019; Volume 486, pp. 431–40. [CrossRef]

- Scharf-Wildenhain R, Haelsig A, Hensel J, Wandtke K, Schroepfer D, Kromm A, et al. Influence of Heat Control on Properties and Residual Stresses of Additive-Welded High-Strength Steel Components. Metals. 2022; Volume 12, pp. 951. [CrossRef]

- Javadi Y, Smith MC, Abburi Venkata K, Naveed N, Forsey AN, Francis JA, et al. Residual stress measurement round robin on an electron beam welded joint between austenitic stainless steel 316L(N) and ferritic steel P91. Int J Press Vessel Pip. 2017; Volume 154, pp. 41–57. [CrossRef]

- Saleh B, Fathi R, Tian Y, Jinghua NR, Aibin J. Fundamentals and advances of wire arc additive manufacturing : materials, process parameters, potential applications, and future trends. Archives of Civil and Mechanical Engineering. Springer London; 2023; Volume 23, pp. 1–71. [CrossRef]

- Rosli NA, Alkahari MR, bin Abdollah MF, Maidin S, Ramli FR, Herawan SG. Review on effect of heat input for wire arc additive manufacturing process. J Mater Res Technol. 2021; Volume 11, pp. 2127–45. [CrossRef]

- Liew J, Li Z, Alkahari MR, Ana N, Rosli B, Hasan R. Review of Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing for 3D Metal Printing Review of Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing for 3D Metal Printing. 2019; Volume 13, pp. 346-353. [CrossRef]

- Woo W, Kim DK, Kingston EJ, Luzin V, Salvemini F, Hill MR. Effect of interlayers and scanning strategies on through-thickness residual stress distributions in additive manufactured ferritic-austenitic steel structure. Mater Sci Eng A. 2019; Volume 744, pp. 618–29. [CrossRef]

- Geng H, Li J, Gao J, Lin X. Theoretical model of residual stress and warpage for wire and arc additive manufacturing stiffened panels. Metals. 2020; Volume 10, pp. 666. [CrossRef]

- Rouquette S, Cambon C, Bendaoud I, Soulié F, Rouquette S, Cambon C, et al. Residual stresses in ss316l specimens after deposition of melted filler wire. ICRS11 11th Int Conf Residual Stress - Nancy – Fr – 27-30th March 2022.

- Kumaran M, Senthilkumar V, Justus Panicke CT, Shishir R. Investigating the residual stress in additive manufacturing of repair work by directed energy deposition process on SS316L hot rolled steel substrate. Mater Today Proc. 2021; Volume 47, pp. 4475–8. [CrossRef]

- Mishurova T, Sydow B, Thiede T, Sizova I, Ulbricht A, Bambach M, et al. Residual stress and microstructure of a Ti-6Al-4V wire arc additive manufacturing hybrid demonstrator. Metals. 2020; Volume 10, pp. 701. [CrossRef]

- Martina F, Roy MJ, Szost BA, Terzi S, Colegrove PA, Williams SW, et al. Residual stress of as-deposited and rolled wire + arc additive manufacturing Ti – 6Al – 4V components. 2016; Volume 32, pp. 1439–48. [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Lin C, Wang J, Wang J, Yan L, Luo Y, et al. Residual stress distributions in thick specimens excavated from a large circular wire+arc additive manufacturing mockup. J Manuf Process. 2020; Volume 56, pp. 474–81. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Jin X, Liu C, Xiao M, Lu J, Fan H, et al. Residual stress, mechanical properties, and grain morphology of Ti-6Al-4V alloy produced by ultrasonic impact treatment assisted wire and arc additive manufacturing. Metals. 2018; Volume 8, pp.934. [CrossRef]

- Boruah D, Dewagtere N, Ahmad B, Nunes R, Tacq J, Zhang X, et al. Digital Image Correlation for Measuring Full-Field Residual Stresses in Wire and Arc Additive Manufactured Components. Materials. 2023; Volume 16, pp. 1702. [CrossRef]

- Steel S, Microstructure C. Wire Arc Additive Manufactured Mild Steel and Austenitic Properties and Residual Stresses. 2022.

- Gao L, Chuang AC, Kenesei P, Ren Z, Balderson L, Sun T. An operando synchrotron study on the effect of wire melting state on solidification microstructures of Inconel 718 in wire-laser directed energy deposition. Int J Mach Tools Manuf. 2024; Volume 194, pp. 104089. [CrossRef]

- Robin IK, Sprouster DJ, Sridharan N, Snead LL, Zinkle SJ. Synchrotron based investigation of anisotropy and microstructure of wire arc additive manufactured Grade 91 steel. J Mater Res Technol. 2024; Volume 29, pp. 5010–21. [CrossRef]

- Kumar V, Mandal A. Parametric study and characterization of wire arc additive manufactured steel structures. 2021; Volume 115, pp. 1723–33. [CrossRef]

- Saleh B, Fathi R, Tian Y, Radhika N, Jiang J, Ma A. Fundamentals and advances of wire arc additive manufacturing: materials, process parameters, potential applications, and future trends. Archives of Civil and Mechanical Engineering. Springer London; 2023. [CrossRef]

- Shen C, Reid M, Liss KD, Pan Z, Ma Y, Cuiuri D, et al. Neutron diffraction residual stress determinations in Fe3Al based iron aluminide components fabricated using wire-arc additive manufacturing (WAAM). Addit Manuf. 2019; Volume 29, pp. 100774. [CrossRef]

- Rouquette S, Cambon C, Bendaoud I, Cabeza S, Soulié F. Effect of Layer Addition on Residual Stresses of Wire Arc Additive Manufactured Stainless Steel Specimens. J Manuf Sci Eng. 2024; Volume 146, pp. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues TA, Cipriano Farias FW, Zhang K, Shamsolhodaei A, Shen J, Zhou N, et al. Wire and arc additive manufacturing of 316L stainless steel/Inconel 625 functionally graded material: Development and characterization. J Mater Res Technol. 2022; Volume 21, pp. 237–51. [CrossRef]

- Théodore J, Couturier L, Girault B, Cabeza S, Pirling T, Frapier R, et al. Relationship between microstructure, and residual strain and stress in stainless steels in-situ alloyed by double-wire arc additive manufacturing (D-WAAM) process. Materialia. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Manikandan MDBKM. Evaluation of Microstructure, Residual Stress, and Mechanical Properties in Different Planes of Wire + Arc Additive Manufactured Nickel - Based Superalloy. Met Mater Int. 2022; Volume 28, pp. 3033–56. [CrossRef]

- Sun J, Hensel J, Köhler M, Dilger K. Residual stress in wire and arc additively manufactured aluminum components. J Manuf Process. 2021; Volume 65, pp. 97–111. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues TA, Cipriano Farias FW, Avila JA, Maawad E, Schell N, Santos TG, et al. Effect of heat treatments on Inconel 625 fabricated by wire and arc additive manufacturing: an in situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction analysis. Sci Technol Weld Join. 2023; Volume 28, pp. 534–9. [CrossRef]

- Wandtke K, Becker A, Schroepfer D, Kromm A, Kannengiesser T, Scharf-Wildenhain R, et al. Residual Stress Evolution during Slot Milling for Repair Welding and Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing of High-Strength Steel Components. Metals. 2024 Volume 14, pp. 82. [CrossRef]

- Wu Q, Mukherjee T, Liu C, Lu J, DebRoy T. Residual stresses and distortion in the patterned printing of titanium and nickel alloys. Addit Manuf. 2019; Volume 29, pp. 100808. [CrossRef]

- Han Y. A Finite Element Study of Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing of Aluminum Alloy. Appl Sci. 2024; Volume 14, pp. 810. [CrossRef]

- Khaled H, Abusalma J. Parametric Study of Residual Stresses in Wire and Arc Additive Manufactured Parts. 2020.

- Saadatmand M, Talemi R. Study on the thermal cycle of wire arc additive manufactured (WAAM) carbon steel wall using numerical simulation. Frat ed Integrita Strutt. 2020; Volume 14, pp. 98–104. [CrossRef]

- Eisazadeh H, Achuthan A, Goldak JA, Aidun DK. Effect of material properties and mechanical tensioning load on residual stress formation in GTA 304-A36 dissimilar weld. J Mater Process Technol. 2015; Volume 222, pp. 344–55. [CrossRef]

- Nezamdost MR, Esfahani MRN, Hashemi SH, Mirbozorgi SA. Investigation of temperature and residual stresses field of submerged arc welding by finite element method and experiments. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2016; Volume 87, pp. 615–24. [CrossRef]

- Huang H, Ma N, Chen J, Feng Z, Murakawa H. Toward large-scale simulation of residual stress and distortion in wire and arc additive manufacturing. Addit Manuf. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Han YS. Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing: A Study of Process Parameters Using Multiphysics Simulations. Materials. 2023; Volume 16, pp. 7267. [CrossRef]

- Jia J, Zhao Y, Dong M, Wu A, Li Q. Numerical simulation on residual stress and deformation for WAAM parts of aluminum alloy based on temperature function method. China Weld (English Ed. 2020; Volume 29, pp. 1–8.

- Feng, G.; Wang H. W, Y.; Deng, D.; Zhang J. Numerical Simulation of Residual Stress and Deformation in Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing. Crystals. 2022; Volume 12, pp. 803. [CrossRef]

- Graf M, Pradjadhiana KP, Hälsig A, Manurung YHP, Awiszus B. Numerical simulation of metallic wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM). AIP Conf Proc. 2018; Volume 960, pp. 140010. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad SN, Manurung YHP, Mat MF, Minggu Z, Jaffar A, Pruller S, et al. FEM simulation procedure for distortion and residual stress analysis of wire arc additive manufacturing. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2020; Volume 834, pp. 012083. [CrossRef]

- Cadiou S, Courtois M, Carin M, Berckmans W, Le masson P. 3D heat transfer, fluid flow and electromagnetic model for cold metal transfer wire arc additive manufacturing (Cmt-Waam). Addit Manuf. 2020; Volume 36, pp. 101541. [CrossRef]

- Drexler H, Haunreiter F, Raberger L, Reiter L, Hütter A, Enzinger N. Numerical Modeling of Distortions and Residual Stresses During Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing of an ER 5183 Alloy with Weaving Deposition. BHM Berg- und Hüttenmännische Monatshefte. 2024; Volume 169, pp. 38–47. [CrossRef]

- Bonifaz EA, Palomeque JS. A mechanical model in wire + Arc additive manufacturing process. Prog Addit Manuf. 2020; Volume 5, pp. 163–9. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-gordillo E, Gómez-ortega A, Morales-estrella R, Pérez-barrera J, Gonzalez-carmona J, Alvarado-orozco J. Effect of Cold Metal Transfer Parameters during Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing of Ti6Al4V Multi- layer Walls. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Silva WF. Evaluation of the properties of Inconel ® 625 preforms manufactured using WAAM technology. Res Sq. 2024; pp. 1–21.

- Derekar KS, Addison A, Joshi SS, Zhang X, Lawrence J, Xu L, et al. Effect of pulsed metal inert gas (pulsed-MIG) and cold metal transfer (CMT) techniques on hydrogen dissolution in wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM) of aluminium. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2020; Volume 107, pp. 311–31. [CrossRef]

- Rosli NA, Alkahari MR, Ramli FR, Sudin MN, Maidin S. Influence of Process Parameters in Wire and Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM) Process. J Mech Eng. 2020; Volume 17, pp. 69–78. [CrossRef]

- Derekar KS, Ahmad B, Zhang X, Joshi SS, Lawrence J, Xu L, et al. Effects of Process Variants on Residual Stresses in Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing of Aluminum Alloy 5183. J Manuf Sci Eng Trans ASME. 2022; Volume 144, pp. 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Yuan Q, Liu C, Wang W, Wang M. Residual stress distribution in a large specimen fabricated by wire-arc additive manufacturing. Sci Technol Weld Join. 2023; Volume 28, pp. 137–44. [CrossRef]

- Fu R, Tang S, Lu J, Cui Y, Li Z, Zhang H, et al. Hot-wire arc additive manufacturing of aluminum alloy with reduced porosity and high deposition rate. Mater Des. 2021; pp. 199109370. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Li Y, Gao M, Zeng X. Wire arc additive manufacturing of Al-6Mg alloy using variable polarity cold metal transfer arc as power source. Mater Sci Eng A. 2018; Volume 711, pp. 415–23. [CrossRef]

- Corbin DJ, Nassar AR, Reutzel EW, Kistler NA, Beese AM, Michaleris P. Impact of directed energy deposition parameters on mechanical distortion of laser deposited Ti-6Al-4V. Solid Free Fabr 2016 Proc 27th Annu Int Solid Free Fabr Symp - An Addit Manuf Conf SFF 2016.; pp. 670–9.

- Xiong J, Lei Y, Li R. Finite element analysis and experimental validation of thermal behavior for thin-walled parts in GMAW-based additive manufacturing with various substrate preheating temperatures. Appl Therm Eng. 2017;1 Volume 26, pp. 43–52. [CrossRef]

- Zhao J, Quan G zheng, Zhang Y qing, Ma Y yao, Jiang L he, Dai W wei, et al. Influence of deposition path strategy on residual stress and deformation in weaving wire-arc additive manufacturing of disc parts. J Mater Res Technol. 2024; Volume 30, pp. 2242–56. [CrossRef]

- Ouellet T, Croteau M, Bois-Brochu A, Lévesque J. Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing of Aluminium Alloys †. Eng Proc. 2023; Volume 43, pp. 2–6. [CrossRef]

- Li JLZ, Alkahari MR, Rosli NAB, Hasan R, Sudin MN, Ramli FR. Review of wire arc additive manufacturing for 3d metal printing. Int J Autom Technol. 2019; Volume 13, pp. 346–53. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Wang X, Paddea S, Zhang X. Fatigue crack propagation behaviour in wire+arc additive manufactured Ti-6Al-4V: Effects of microstructure and residual stress. Mater Des. 2016; Volume 90, pp. 551–61. [CrossRef]

- Gu J, Gao M, Yang S, Bai J, Zhai Y, Ding J. Microstructure, defects, and mechanical properties of wire + arc additively manufactured Al[sbnd]Cu4.3-Mg1.5 alloy. Mater Des. 2020; Volume 186, pp. 108357. [CrossRef]

- Kindermann RM, Roy MJ, Morana R, Francis JA. Effects of microstructural heterogeneity and structural defects on the mechanical behaviour of wire + arc additively manufactured Inconel 718 components. Materials Science and Engineering A. 2022, Volume 839, pp. 142826. [CrossRef]

- Yildiz AS, Koc BI, Yilmaz O. Thermal behavior determination for wire arc additive manufacturing process. Procedia Manuf. 2020;Volume 54, pp. 233–7. [CrossRef]

- Ali Y, Henckell P, Hildebrand J, Reimann J, Bergmann JP, Barnikol-Oettler S, et al. On the Influence of Linear Energy/Heat Input Coefficient on Hardness and Weld Bead Geometry in Chromium-Rich Stringer GMAW Coatings. J Manuf Proces. 2022; Volume 15, pp. 6019. [CrossRef]

- Romanenko D, Prakash VJ, Kuhn T, Moeller C, Hintze W, Emmelmann C. Effect of DED process parameters on distortion and residual stress state of additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V components during machining. Procedia CIRP. 2022; Volume 11, pp. 271–6.

- Layer-by-layer model-based adaptive control for wire arc additive manufacturing of thin-wall structures. 2022; Volume 33, pp. 1165–80.

- Liu B, Lan J, Liu H, Chen X, Zhang X, Jiang Z, et al. The Effects of Processing Parameters during the Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing of 308L Stainless Steel on the Formation of a Thin-Walled Structure. Materials. 2024; Volume 17, pp. 1337. [CrossRef]

- Ali MH, Han YS. A Finite Element Analysis on the Effect of Scanning Pattern and Energy on Residual Stress and Deformation in Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing of EH36 Steel. Materials. 2023; Volume 16. pp. 4698. [CrossRef]

- Chen S, He T, Wu X, Lei G. Synergistic effect of carbides and residual strain on the mechanical behavior of Ni-17 Mo-7Cr superalloy made by wire-arc additive manufacturing. Mater Lett. 2021; Volume 287, pp. 129291. [CrossRef]

- Winczek J, Gucwa M, Makles K, Mičian M, Yadav A. The amount of heat input to the weld per unit length and per unit volume. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2021; Volume 1199, pp. 012067. [CrossRef]

- Koli Y, Arora S, Ahmad S, Priya, Yuvaraj N, Khan ZA. Investigations and Multi-response Optimization of Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing Cold Metal Transfer Process Parameters for Fabrication of SS308L Samples. J Mater Eng Perform. 2023; Volume 32, pp. 2463–75. [CrossRef]

- Cambon C, Rouquette S, Bendaoud I, Bordreuil C, Wimpory R, Soulie F. Thermo-mechanical simulation of overlaid layers made with wire + arc additive manufacturing and GMAW-cold metal transfer. Weld World. 2020; Volume 64, pp. 1427–35. [CrossRef]

- Omiyale BO, Olugbade TO, Abioye TE, Farayibi PK. Wire arc additive manufacturing of aluminium alloys for aerospace and automotive applications: a review. Mater Sci Technol (United Kingdom). 2022; Volume 38, pp. 391–408. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Pan Z, Carpenter K, Han J, Wang Z, Li H. Comparative study on crystallographic orientation, precipitation, phase transformation and mechanical response of Ni-rich NiTi alloy fabricated by WAAM at elevated substrate heating temperatures. Mater Sci Eng A. 2021; Volume 800, pp. 140307. [CrossRef]

- Ding J, Colegrove P, Martina F, Williams S, Wiktorowicz R, Palt MR. Development of a laminar flow local shielding device for wire + arc additive manufacture. J Mater Process Technol. 2015; Volume 226, pp. 99–105. [CrossRef]

- Tonelli L, Laghi V, Palermo M, Trombetti T, Ceschini L. AA5083 (Al–Mg) plates produced by wire-and-arc additive manufacturing: effect of specimen orientation on microstructure and tensile properties. Prog Addit Manuf. 2021; Volume 6, pp. 479–94. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Shen C, Hua X, Li F, Zhang Y, Zhu Y. Influence of wire-arc additive manufacturing path planning strategy on the residual stress status in one single buildup layer. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2020; Volume 111, pp. 797–806. [CrossRef]

- Pawlik J, Cieślik J, Bembenek M, Góral T, Kapayeva S, Kapkenova M. On the Influence of Linear Energy/Heat Input Coefficient on Hardness and Weld Bead Geometry in Chromium-Rich Stringer GMAW Coatings. Materials. 2022; Volume 15, pp. 6019. [CrossRef]

- Denlinger ER, Heigel JC, Michaleris P, Palmer TA. Effect of inter-layer dwell time on distortion and residual stress in additive manufacturing of titanium and nickel alloys. J Mater Process Technol. 2015; Volume 215, pp. 123–31. [CrossRef]

- Gudur S, Nagallapati V, Pawar S, Muvvala G, Simhambhatla S. A study on the effect of substrate heating and cooling on bead geometry in wire arc additive manufacturing and its correlation with cooling rate. Mater Today Proc. 2019; Volume 41, pp. 431–6. [CrossRef]

- Singh S, Jinoop AN, Tarun Kumar GTA, Palani IA, Paul CP, Prashanth KG. Effect of interlayer delay on the microstructure and mechanical properties of wire arc additive manufactured wall structures. Materials. 2021; Volume 14, pp. 4187. [CrossRef]

- Bermingham MJ, Nicastro L, Kent D, Chen Y, Dargusch MS. Optimising the mechanical properties of Ti-6Al-4V components produced by wire + arc additive manufacturing with post-process heat treatments. J Alloys Compd. 2018; Volume 753, pp. 247–55. [CrossRef]

- Kumar A, Maji K. Selection of Process Parameters for Near-Net Shape Deposition in Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing by Genetic Algorithm. J Mater Eng Perform. 2020; Volume 29, pp. 3334–52. [CrossRef]

- Ali Y, Henckell P, Hildebrand J, Reimann J, Bergmann JP, Barnikol-Oettler S. Wire arc additive manufacturing of hot work tool steel with CMT process. J Mater Process Technol. 2019; Volume 269, pp. 109–16. [CrossRef]

- Laghi V. Tensile properties and microstructural features of 304L austenitic stainless steel produced by wire-and-arc additive manufacturing. 2020; Volume 106, pp. 3693–705. [CrossRef]

- Dinovitzer M, Chen X, Laliberte J, Huang X, Frei H. Effect of wire and arc additive manufacturing (WAAM) process parameters on bead geometry and microstructure. Addit Manuf. 2019; Volume 26, pp. 138–46. [CrossRef]

- Naveen Srinivas M, Vimal KEK, Manikandan N, Sritharanandh G. Parametric optimization and multiple regression modelling for fabrication of aluminium alloy thin plate using wire arc additive manufacturing. Int J Interact Des Manuf. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Zavdoveev A, Pozniakov V, Baudin T, Kim HS, Klochkov I, Motrunich S, et al. Optimization of the pulsed arc welding parameters for wire arc additive manufacturing in austenitic steel applications. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2022; Volume 119, pp. 5175–93. [CrossRef]

- Lu X, Li MV, Yang H. Comparison of wire-arc and powder-laser additive manufacturing for IN718 superalloy: unified consideration for selecting process parameters based on volumetric energy density. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2021; Volume 114, pp. 1517–31. [CrossRef]

- Vora J, Pandey R, Dodiya P, Patel V, Khanna S, Vaghasia V, et al. Fabrication of Multi-Walled Structure through Parametric Study of Bead Geometries of GMAW-Based WAAM Process of SS309L. Materials. 2023; Volume 16, pp. 5147. [CrossRef]

- Athaib NH, Haleem AH, Al-Zubaidy B. A review of Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM) of Aluminium Composite, Process, Classification, Advantages, Challenges, and Application. J Phys Conf Ser. 2021; Volume 1973, pp. 012083. [CrossRef]

- Scharf-Wildenhain R, Haelsig A, Hensel J, Wandtke K, Schroepfer D, Kannengiesser T. Heat control and design-related effects on the properties and welding stresses in WAAM components of high-strength structural steels. Weld World. 2023; Volume 67, pp. 955–65. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Zhang X, Wang X, Ding J, Traoré Y, Paddea S, et al. Crack path selection at the interface of wrought and wire + arc additive manufactured Ti-6Al-4V. Mater Des. 2016; Volume 104, pp. 365–75. [CrossRef]

- Yang YH, Guan ZP, Ma PK, Ren MW, Jia HL, Zhao P, et al. Wire arc additive manufacturing of a novel ATZM31 Mg alloy: Microstructure evolution and mechanical properties. J Magnes Alloy. 2023; Volume 10, pp. 44. [CrossRef]

- Koli Y, Yuvaraj N, Sivanandam A, Vipin. Control of humping phenomenon and analyzing mechanical properties of Al–Si wire-arc additive manufacturing fabricated samples using cold metal transfer process. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part C J Mech Eng Sci. 2022; Volume 236, pp. 984–96. [CrossRef]

- Jing Y, Fang X, Xi N, Chang T, Duan Y, Huang K. Improved tensile strength and fatigue properties of wire-arc additively manufactured 2319 aluminum alloy by surface laser shock peening. Mater Sci Eng A. 2023; Volume 864, pp. 144599. [CrossRef]

- Chi J, Cai Z, Wan Z, Zhang H, Chen Z, Li L, et al. Effects of heat treatment combined with laser shock peening on wire and arc additive manufactured Ti17 titanium alloy: Microstructures, residual stress and mechanical properties. Surf Coatings Technol. 2020; Volume 396, pp. 125908. [CrossRef]

- Sousa BM, Coelho FGF, Júnior GMM, de Oliveira HCP, da Silva NN. Thermal and microstructural analysis of intersections manufactured by wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM). Weld World. 2024; pp. 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Ma D, Xu C, Sui S, Tian J, Guo C, Wu X, et al. Microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of wire arc additively manufactured Mg-Gd-Y-Zr alloy by post heat treatments. Virtual Phys Prototyp. 2023; Volume 18, pp. 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Szost BA, Terzi S, Martina F, Boisselier D, Prytuliak A, Pirling T, et al. A comparative study of additive manufacturing techniques: Residual stress and microstructural analysis of CLAD and WAAM printed Ti-6Al-4V components. Mater Des. 2016; Volume 89, pp. 559–67. [CrossRef]

- Kumar A, Maji K, Shrivastava A. Investigations on Deposition Geometry and Mechanical Properties of Wire Arc Additive Manufactured Inconel 625. Int J Precis Eng Manuf. 2023; Volume 24, pp. 1483–500. [CrossRef]

- Vazquez L, Rodriguez MN, Rodriguez I, Alvarez P. Influence of post-deposition heat treatments on the microstructure and tensile properties of ti-6al-4v parts manufactured by cmt-waam. Metals. 2021; Volume 11, pp. 1161. [CrossRef]

- Kindermann RM, Roy MJ, Morana R, Francis JA. Materials Science & Engineering A Effects of microstructural heterogeneity and structural defects on the mechanical behaviour of wire + arc additively manufactured Inconel 718 components. Mater Sci Eng A. 2022; Volume 839, pp. 42826. [CrossRef]

- Geng H, Li J, Xiong J, Lin X, Zhang F. Optimization of wire feed for GTAW based additive manufacturing. J Mater Process Technol. 2017; Volume 243, pp. 40–7. [CrossRef]

- Li R, Xiong J, Lei Y. Investigation on thermal stress evolution induced by wire and arc additive manufacturing for circular thin-walled parts. J Manuf Process. 2019; Volume 40, pp. 59–67. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Neel Kamal, G, Ganesan, Siddhartha, Karade Shahu, Mehta, Avinash Kumar, KP, Karunakaran. Effect of Multiple Technologies on Minimizing the Residual Stresses in Additive Manufacturing. ICRS 11 - 11th Int Conf Residual Stress SF2M; IJL, Mar 2022, Nancy, Fr. 2022; pp. 040150.

- Ali MH, Han YS. Effect of phase transformations on scanning strategy in waam fabrication. Materials. 2021; Volume 14. [CrossRef]

- Gornyakov V, Sun Y, Ding J, Williams S. Modelling and optimising hybrid process of wire arc additive manufacturing and high-pressure rolling. Mater Des. 2022; Volume 223, pp. 111121. [CrossRef]

- Lailatul Mufidah KT. Efficient modelling and evaluation of rolling for mitigation of residual stress and distortion in wire arc additive manufacturing. Cranfield.ac.uk. 2021; Volume 7, pp. 265.

- Zhang T, Li H, Gong H, Ding J, Wu Y, Diao C, et al. Hybrid wire - arc additive manufacture and effect of rolling process on microstructure and tensile properties of Inconel 718. J Mater Process Technol. 2022; Volume 299, pp. 321-6. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava S, Garg RK, Sharma VS, Sachdeva A. Measurement and Mitigation of Residual Stress in Wire-Arc Additive Manufacturing: A Review of Macro-Scale Continuum Modelling Approach. Arch Comput Methods Eng. 2021; Volume 28, pp. 3491–515. [CrossRef]

- Montevecchi F, Venturini G, Scippa A, Campatelli G. Finite Element Modelling of Wire-arc-additive-manufacturing Process. Procedia CIRP. 2016; Volume 55, pp. 109–14. [CrossRef]

- Bankong BD, Abioye TE, Olugbade TO, Zuhailawati H, Gbadeyan OO, Ogedengbe TI. Review of post-processing methods for high-quality wire arc additive manufacturing. Mater Sci Technol (United Kingdom). 2023; Volume 39, pp. 129–46. [CrossRef]

- Hönnige JR, Colegrove PA, Ahmad B, Fitzpatrick ME, Ganguly S, Lee TL, et al. Residual stress and texture control in Ti-6Al-4V wire + arc additively manufactured intersections by stress relief and rolling. Mater Des. 2018; Volume 150, pp. 193–205. [CrossRef]

- Li K, Klecka MA, Chen S, Xiong W. Wire-arc additive manufacturing and post-heat treatment optimization on microstructure and mechanical properties of Grade 91 steel. Addit Manuf. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Nie L, Wu Y, Gong H, Chen D, Guo X. Effect of shot peening on redistribution of residual stress field in friction stir welding of 2219 aluminum alloy. Materials. 2020; Volume 13, pp. 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Sun R, Li L, Zhu Y, Guo W, Peng P, Cong B, et al. Microstructure, residual stress and tensile properties control of wire-arc additive manufactured 2319 aluminum alloy with laser shock peening. J Alloys Compd. 2018; Volume 747, pp. 255–65. [CrossRef]

- Ermakova A, Razavi N, Cabeza S, Gadalinska E, Reid M, Paradowska A, et al. The effect of surface treatment and orientation on fatigue crack growth rate and residual stress distribution of wire arc additively manufactured low carbon steel components. J Mater Res Technol. 2023; Volume 24, pp. 2988–3004. [CrossRef]

- Ding Y, Muñiz-Lerma JA, Trask M, Chou S, Walker A, Brochu M. Microstructure and mechanical property considerations in additive manufacturing of aluminum alloys. MRS Bull. 2016; Volume 41, pp. 745–51. [CrossRef]

- Busachi A, Erkoyuncu J, Colegrove P, Martina F, Ding J. Designing a WAAM based manufacturing system for defence applications. Procedia CIRP. 2015; Volume 37, pp. 48–53. [CrossRef]

- Abusalma, H., Eisazadeh, H., Hejripour, F., Bunn, J., & Aidun D. Parametric study of residual stress formation in Wire and Arc Additive Manufacturing. J Manuf Process. 2022; Volume 75, pp. 863-876. [CrossRef]

- Kyvelou P, Huang C, Li J, Gardner L. Residual stresses in steel I-sections strengthened by wire arc additive manufacturing. Structures. 2024; Volume 60. [CrossRef]

- Wu B, Pan Z, Ding D, Cuiuri D, Li H, Xu J, et al. A review of the wire arc additive manufacturing of metals: properties, defects and quality improvement. J Manuf Process. 2018; Volume 35, pp. 127–39. [CrossRef]

- Colegrove PA, Donoghue J, Martina F, Gu J, Prangnell P, Hönnige J. Application of bulk deformation methods for microstructural and material property improvement and residual stress and distortion control in additively manufactured components. Scr Mater. 2017; Volume 135, pp. 111–8. [CrossRef]

- Karmuhilan M, Sood AK. Intelligent process model for bead geometry prediction in WAAM. Mater Today Proc. 2018; Volume 5, pp. 24005–13. [CrossRef]

- Tang S, Wang G, Huang C, Li R, Zhou S, Zhang H. Investigation, modeling and optimization of abnormal areas of weld beads in wire and arc additive manufacturing. Rapid Prototyp J. 2020; Volume 26, pp. 183–95. [CrossRef]

- Pawlik J, Cieślik J, Bembenek M, Góral T, Kapayeva S, Kapkenova M. On the Influence of Linear Energy/Heat Input Coefficient on Hardness and Weld Bead Geometry in Chromium-Rich Stringer GMAW Coatings. Materials. 2022; Volume 15, pp. 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Veiga F, Suárez A, Aldalur E, Bhujangrao T. Effect of the metal transfer mode on the symmetry of bead geometry in waam aluminum. Symmetry. 2021; Volume 13, pp. 1245. [CrossRef]

- Ding D, Pan Z, Cuiuri D, Li H. A multi-bead overlapping model for robotic wire and arc additive manufacturing (WAAM). Robot Comput Integr Manuf. 2015; Volume 31, pp. 101–10. [CrossRef]

- Geng H, Xiong J, Huang D, Lin X, Li J. A prediction model of layer geometrical size in wire and arc additive manufacture using response surface methodology. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2017; Volume 93, pp. 175–86. [CrossRef]

- Banaee SA, Kapil A, Marefat F, Sharma A. Generalised overlapping model for multi-material wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM). Virtual Phys Prototyp. 2023; Volume 18, pp. 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Surovi NA, Soh GS. Acoustic feature based geometric defect identification in wire arc additive manufacturing. Virtual Phys Prototyp. 2023; Volume 18, pp. 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y tao, Li W gang, Liu A. Optimization of geometry quality model for wire and arc additive manufacture based on adaptive multi-objective grey wolf algorithm. Soft Comput. 2020; Volume 24, pp. 17401–16. [CrossRef]

- Alomari Y, Birosz MT, Andó M. Part orientation optimization for Wire and Arc Additive Manufacturing process for convex and non-convex shapes. Sci Rep. 2023; Volume 13, pp. 2203. [CrossRef]

- Wani ZK, Abdullah AB. Bead Geometry Control in Wire Arc Additive Manufactured Profile - A Review. Pertanika J Sci Technol. 2024; Volume 32, pp. 917–42. [CrossRef]

- Vora J, Parikh N, Chaudhari R, Patel VK, Paramar H, Pimenov DY, et al. applied sciences Optimization of Bead Morphology for GMAW-Based Wire-Arc Metal-Cored Wires. 2022; Valome 12, pp. 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Bai H, Ren C, Fang X, Lu B. A comprehensive prediction model of bead geometry in wire and arc additive manufacturing. J Phys Conf Ser. 2020; Valome 1624, pp. 1624. [CrossRef]

- Chintala A, Tejaswi Kumar M, Sathishkumar M, Arivazhagan N, Manikandan M. Technology Development for Producing Inconel 625 in Aerospace Application Using Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing Process. J Mater Eng Perform. 2021; Valome 30, pp. 5333–41. [CrossRef]

- Hamrani A, Bouarab FZ, Agarwal A, Ju K, Akbarzadeh H. Advancements and applications of multiple wire processes in additive manufacturing: a comprehensive systematic review. Virtual Phys Prototyp. 2023; Valome 18, pp. 1–34. [CrossRef]

- Queguineur A, Rückert G, Cortial F, Hascoët JY. Evaluation of wire arc additive manufacturing for large-sized components in naval applications. Weld World. 2018; Valome 62, pp. 259–66. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Cui Q, Pang C, Xu P, Luo W, Li J. Integrated vehicle chassis fabricated by wire and arc additive manufacturing: structure generation, printing radian optimisation, and performance prediction. Virtual Phys Prototyp. 2024; Valome 19, pp. 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Singh SR, Khanna P. Wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM): A new process to shape engineering materials. Mater Today Proc. 2021; Valome 44, pp. 118–28. [CrossRef]

- Vishnukumar M, Pramod R, Rajesh Kannan A. Wire arc additive manufacturing for repairing aluminium structures in marine applications. Mater Lett. 2021; Valome 299, pp. 130112. [CrossRef]

- Shah A, Aliyev R, Zeidler H, Krinke S. A Review of the Recent Developments and Challenges in Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM) Process. J Manuf Mater Process. 2023; Valome 7, pp. 97. [CrossRef]

- Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing: Review on Recent Findings and Challenges in Industrial Applications and Materials Characterization. Metals. 2021; Volume 11, pp. 939. [CrossRef]

- Boţilă LN. Considerations regarding aluminum alloys used in the aeronautic/aerospace industry and use of wire arc additive manufacturing WAAM for their industrial applications. 2020; Valome 4, pp. 9–24.

- Liu J, Xu Y, Ge Y, Hou Z, Chen S. Wire and arc additive manufacturing of metal components: a review of recent research developments. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2020; Valome 111, pp. 149–98. [CrossRef]

- Arana M, Ukar E, Rodriguez I, Aguilar D, Álvarez P. Influence of deposition strategy and heat treatment on mechanical properties and microstructure of 2319 aluminium WAAM components. Mater Des. 2022; Valome 221, pp. 110974. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Zhang Q, Chong C, Yap R, Tay K, Hang T, et al. Challenges associated with the wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM) of Aluminum alloys. Mater Today Proc. 2019; Valome 221, pp. 6–20. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Li F, Chen S, Lu Z. Unit block–based process planning strategy of WAAM for complex shell–shaped component. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2019; Valome 104, pp. 3915–27. [CrossRef]

- Pant H, Arora A, Gopakumar GS, Chadha U, Saeidi A, Patterson AE. Applications of wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM) for aerospace component manufacturing. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2023; Valome 127, pp. 4995–5011. [CrossRef]

- Bachus NA, Strantza M, Clausen B, D’Elia CR, Hill MR, Ko JYP, et al. Novel bulk triaxial residual stress mapping in an additive manufactured bridge sample by coupling energy dispersive X-ray diffraction and contour method measurements. Addit Manuf. 2024; Valome 83, pp. 104070. [CrossRef]

- J.V. Gordon, C.V. Haden, H.F. Nied RPV and D. Fatigue crack growth anisotropy, texture and residual stress in austenitic steel made by wire and arc additive manufacturing. Mater Sci Eng A. 2018; Valome 115, pp. 60–6. [CrossRef]

| Methods | Materials | Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| ND | 316L stainless steel | The process parameters' influence on RS is barely noticeable in the melted zone. | [22] |

| Fe3Al alloy | Large columnar grains result in anisotropy and RS is tensile in the building direction, and the tension to compression progressively moves up from the beginning to the end of the deposition way. | [23] | |

| AA6061 | RS indicates the occurrence of tensile stresses with a greater magnitude in the constructed parts, substrate exhibits fewer compressive stresses. No significant dissimilarities were seen in mechanical properties. | [61] | |

| 2319 aluminum alloy | RS along the build direction in the deposited wall is tensile stress, extending up to the floor. The inter-pass rolled walls, reduced RS to enhanced strength in the longitudinal direction. | [24] | |

| Fe3Al | RS and distortions resulting from the WAAM process are major concerns as they not only influence the part tolerance but can also cause premature failure in the final component during service. | [86] | |

| stainless steel 304L | The alteration of RS in the specimen after introducing a new deposit. Longitudinal stress was predominantly tensile, reaching its peak at the boundary between the parent material and the layers where the thermal loads were applied. | [87] | |

| Inconel 625 | Measurements showed that lower RS formed in the direct interface functionally graded materials (FGM) compared to the smooth gradient FGM | [88] | |

| Contour and ND | Ti-6Al-4V alloy, stainless steel | The stress in the baseplate varies RS. The lattice parameters were not valid in the baseplate for ND measurements. Cutting out a stress-free exit was used to correct reference samples. | [76,77,89] |

| XRD | Alloy C-276 | The amplitude of tensile RS was perceived in the travel direction compared to the build orientation. The residual strain in the lattice reveals the RS in the material. The larger amplitude of compressive RS was found in the build axis. | [90] |

| Al-5356 alloy | The height of the beam can impact both the level and pattern of longitudinal RS in both the substrate and the beam. This variation primarily affects transverse RS in the substrate and has minimal influence on the beam itself. | [91] | |

| G 79 5 M21 Mn4Ni1.5CrMo (EN ISO 16834-A) | RS, hardness, and microstructure are influenced by welding parameters, geometry, and component design. Heat input causes decreased tensile RS which causes unfavorable grain structure and mechanical response. | [25] | |

| SS308L austenitic stainless steel (SS) | Accumulation of compressive RS attributed to elevated heat input and rapid cooling rates. Greater stress happened closer to the welding base than in other areas. | [26] | |

| Al–6Cu–Mn alloy | The advancement of RS indicates that the most crucial area of the sample is near the substrate, where significant tensile stresses near the material's yield strength are dominant. | [27] | |

| Grade 91 (modified 9Cr–1Mo) -steel | RS varies the characteristics of the material and its microscopic structure WAAMed ferritic/martensitic (FM). The heat treatment applied to the originally manufactured steel did not remove its anisotropic properties. | [83] | |

| Inconel 625 | Post-treatment heat processes can enhance corrosion resistance, and alleviate RS. Measurements indicated that the smooth-gradient approach produced secondary phases like d-phase (Ni3Nb) and carbides, which were absent in the direct interface method. | [88,92] | |

| DIC | Mild steel (AWS ER70S-6) | DIC was employed to oversee the flexural distortion of WAAM components while being released from the clamped H-profiles, and residual tensions were deduced from the strain distribution observed during the unclamping process. | [80,93] |

| Deep hole drilling | Mild steel (G3Si1) & austenitic SS (SS304) | RSs are under compression in the mild steel section and under tension in the austenitic stainless steel (SS) section. These stresses fluctuate across the thickness because of differences in cooling rates on the interior and exterior surfaces. | [81] |

| Hole drilling | Ti-6Al-4V | Grain size decreased after ultrasonic impact therapy and RS of fabricated parts in WAAM after post-UIT are improved. | [79,94] |

| Thermomechanical coupling & Contour | Stainless steels (SS) SUS308LSi | RS is tensile in the layers bordering the surface's upper surface, compressive in the layers near the substrate surface, and tensile near the underside of the substrate. | [13] |

| FEM Softwares | Material | Summary | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANSYS | B91 steel (ER90S-B91 steel) | A thermomechanical assessment of WAAM B91 steel was performed sequentially to assess the variation in residual stress throughout the component. | [11] |

| Simufact | Steels | The dynamic temperature changes, alteration, stress accumulation, and deformation, hold significant importance for applications involving high-strength steels. | [41] |

| ABAQUS | Aluminum alloy | Deposition pattern and travel speed have an impact on RS and warpage in WAAM parts. Results of thermomechanical FE simulations show that the out-in deposition pattern leads to the highest levels of RS and warpage. Increasing travel speed lowers peak temperature and thermal gradient in deposition, reducing RS. | [95] |

| Inconel 718 | Utilized a comprehensive 3D transient heat transfer model to calculate the temperature distribution and gradient in the WAAM process for various process parameters which results in RS. The derived temperature data was utilized in a mechanical model to forecast RS and distortion. | [96] | |

| Carbon steel | The modeling outcomes indicate that as the count of deposited layers rises, the maximum temperature rises resulting in RS while the average cooling rate decreases. | [97] | |

| Austenitic stainless steel (304) and low Carbon steel (A36) | By systematically altering one mechanical property at a time, we isolated the influence of each on RS formation in dissimilar welds. Results show that longitudinal residual stress in both alike and different welds can be diminished within the weld zone by an amount equivalent to the stress caused by applied mechanical tensile force once the tensioning force is released post-cooling. | [98] | |

| API X65 steel | Thermal conditions and RS are forecasted precisely to allow for the regulation of the fusion zone's shape, microstructure, and mechanical characteristics in the Submerged Arc Welding joint. | [99] | |

| Structural steel ER70S-6 wire | The residual stress and deformation of two extensive builds were examined, revealing highly consistent numerical findings and favorable correspondence with experimental outcomes. | [100] | |

| EH36 steel | The effect of the scanning speed on thermal profiles and RS indicates that higher scan speeds result in reduced peak temperatures and heightened cooling rates, thus leading to a rise in the volume portion of martensite within the deposition. | [101] | |

| Aluminum alloy | The RS and deformation were computed using the moving heat sources (MHS) method and the segmented temperature function (STF) method. | [102] | |

| Ti-6Al-4V, S355JR steel & AA2319 | Reduced profile radii of roller effectively eliminate almost all tensile RS near the surfaces. | [33] | |

| MSC. Marc | Y309L | Elevated RS is generated within the deposition layers and also within the middle of the substrate. | [103] |

| Welding filler G3Si1 | Simulation and validation regarding geometry and microstructure variations within the welding passes were conducted with RS reality and simulation using measurement inertia of the thermocouples.Top of Form | [104] | |

| S316L | The variances in RS are influenced by both the fluctuating temperature distribution during the freezing phase and the forces applied to the WAAM structure following the cooling process. | [105] | |

| COMSOL-5.4 | 304 Stainless steel | Large-scale images and high-speed recordings were used for the wall constructed to verify the accuracy of the measurements of the molten pool and the form of the deposition determined which decided the RS in parts. | [106] |

| Process parameters and other factors | Short description | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Material properties: weldability of the materials | Not all materials are equally suitable for WAAM. The process often requires materials with good weldability characteristics, such as low susceptibility to cracking and good fusion properties. For instance, materials' thermal conductivity, coefficient of thermal expansion, and phase transformations can impact RS induced. | [13,35,130,131] |

| Deposition power: Arc current & voltage | In the WAAM process controlling the heat input is critical to prevent overheating, distortion, and metallurgical issues such as excessive grain growth or phase transformations. Variations in heat input alter materials' weldability consequences of RS. | [25,66,67,115,132,133] |

| Speed: wire feed speed, welding travel speed, and deposition rate | Rapid deposition and cooling can lead to increased RS, especially near the deposition zone. The rapid solidification and higher deposition rate can cause thermal gradients and differential cooling rates, resulting in higher levels of tensile RS. Increasing the welding travel speed reduces the amount of time the material spends in the high-temperature zone and leads to lowering the magnitude of RS. | [112,134,135,136] |

| Shielding gas: types of shielding gas, and shielding gas flow rate | Shielding gas plays a crucial role in WAAM processes as it protects the molten weld pool from atmospheric contamination and influences the heat transfer characteristics during deposition. Both the type of shielding gas, gas flow rates such as argon and helium, and reactive gases like CO2 and O2 can have significant effects on RS formation in WAAM products. | [3,38,137] |

| Nozzle distance: Nozzle tip to work distance (Welding torch distances) | The welding torch distance, in WAAM processes can have a significant influence on RS in the final products. Optimizing the nozzle tip to work distance in WAAM processes involves balancing the heat input, cooling rates, distortion control, interlayer bonding, and defect formation to minimize RS and ensure the production of high-quality parts. | [23,24] |

| Printing position: Electrode to layer angle (wire) (θ) and layer height | The printing position affects heat dissipation and buildup, influencing the cooling rate and thermal gradients within the part. The printing position affects the flow of molten metal and the geometry of the deposited beads results in variation of RS. | [37,65,130,138,139] |

| Layer thickness: Substrate thickness, deposition thickness | Decreasing the layer thickness in WAAM fabrication can lead to shorter thermal cycles and reduced heat input per layer. This may result in lower overall RS due to less thermal distortion and reduced HAZ size. | [126,140] |

| Cooling rate: Deposition of layer time, dwell time between layers | The rapid heating and cooling cycles involved in WAAM can lead to the development of significant RS and distortion in the fabricated parts. These can adversely affect the structural integrity and dimensional accuracy of the components, making it challenging to achieve desired weld properties and, as a result, change the RS in printed parts. | [58,59,60,61,103,141] |

| Preheating substrate (Baseplate) | Preheating the substrate in WAAM processes offers several benefits for managing RS in the final products. By reducing thermal gradients, mitigating distortion, improving metallurgical bonding, enhancing ductility, and optimizing cooling rates, preheating helps to create parts with lower levels of RS and improved mechanical properties. | [97,142,143] |

| Part geometry: Printed part shapes & volume of the parts | The geometry of printed parts in WAAM processes significantly influences RS. Understanding how shape complexity, part orientation, volume, and material accumulation patterns affect thermal gradients and cooling rates is crucial for managing RS and ensuring the production of high-quality parts with desired mechanical properties and dimensional accuracy in WAAM. | [9,26] |

| Post-Weld Heat Treatment (PWHT) | PWHT plays a crucial role in managing RS in WAAM products. By subjecting the parts to controlled heating and cooling cycles, PWHT can effectively alleviate RS, improve material properties, and enhance the overall quality and implementation of the manufactured parts. | [1,4,61,117,144] |

| Scanning pattern | The scanning pattern plays a crucial role in influencing heat accumulation, cooling rates during AM deposition, and consequently, the formation of RS. | [101] |

| Wire filler: wire filler diameters and wire grade | The filler wire diameter and wire grade are two key factors that can significantly influence RS in WAAM products. | Not studied |

| Methods | Material and Strategies | Practical Applications And Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inter pass rolling | Ti-6Al-4V alloy | Enhances the bonding and adhesion between the successive layers of material. It also helps redistribute stresses by applying compressive force leading to refined grain structures and minimizing distortion results minimize RS. | [24,76,77,176] |

| Heat treatment (HT) | Grade 91 steel, Ti-6Al-4V | HT post-processing involves controlled heating and cooling cycles to relieve RS. HT is extensively utilized within the aerospace sector to reduce RS in WAAM to produce turbine blades, improving fatigue life and performance. | [83,144,177] |

| Shot peening | 2319 aluminum alloy | Shot peening entails subjecting the surface of a component to bombardment with small, high-velocity particles to induce compressive stresses that counteract tensile RS. It is employed in the automotive sector to enhance the fatigue resistance of WAAM-produced suspension components. | [178,179] |

| Rolling and laser shock peening | Low carbon steel | The methods eliminate harmful tensile RS at the top of the WAAM wall, thereby enhancing fatigue life and slowing down crack growth rates. The bottom region of the WAAM wall demonstrates improved RS conditions, leading to enhanced fatigue performance, all achieved without surface rolling treatment. | [180] |

| Rolling | AA2319, S335JR steel | Increased rolling loads result in elevated maximum equivalent plastic strain and deeper penetration of the equivalent plastic strain results in RS. | [33] |

| Parameter optimization | Al-Cu4.3-Mg1.5 alloy | Adjusting WAAM process parameters, such as deposition speed and layer thickness, can optimize the build conditions to diminish RS. Systematic parameter optimization is applied in the construction industry to reduce RS in large-scale WAAM-printed metal structures. | [37] |

| Material selection | aluminum alloys | Choosing materials with tailored properties, such as low thermal expansion coefficients, can minimize RS formation during WAAM. Specialized materials are used in the energy sector to create high-performance WAAM components with reduced RS. | [181,182] |

| In-process monitoring and control | IN718 Superalloy | Real-time monitoring and control systems adjust process parameters during WAAM to minimize RS formation. In-process monitoring and control are used in aerospace manufacturing to reduce RS variations in critical engine components. | [183] |

| Hot-rolling and cold-forming | ER70S-6 welding wire | The incorporation of WAAM stiffeners at the flange tips of hot-rolled I-sections is demonstrated to result in the creation of favorable tensile RS, which are beneficial for structural stability, reaching maximum values equivalent to the material's yield strength. | [184] |

| Peening and UITs | Ti alloy & Al alloy | Through Ultrasonic Impact Treatment (UIT), grain refinement and randomization of orientation are accomplished, contributing to the enhancement of RS and mechanical strength. | [185] |

| Rolling | Titanium alloys | Offer substantial advantages such as diminishing RS and distortion, as well as refining grain structure. | [186] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).