1. Introduction

“I had an historical dream! I was at Berlinguer’s funeral. There was this Pertini character trying to escape by bike, I chased him.”

Patient n.17

Several phenomenological similarities between dream features and psychotic symptoms have been often observed and underlined (e.g., [

1]). As reviewed in Limosani et al. [

2], besides sensory perceptions in absence of external stimulations which are shared by dreams and psychosis (i.e., hallucinations), cognition is characterized, in both states, by disorganized thought and unrealistic ideational contents, accompanied by bizarre experiences for which the subject shows an impairment of reality testing and, subjectively, a very intense emotional involvement.

Interestingly, each of these phenomena seem to be based on common neuroanatomical and neurochemical mechanisms. Vivid sensorimotor imagery is related to a specific kind of neurotransmission imbalance, with lowered serotoninergic and noradrenergic tone relative to an increase of the cholinergic one [

3]; disorganized thoughts are probably linked to the drastic reduction of functional brain connectivity, involving the majority of brain areas in dreams [

4] and the thalamocortical circuits in schizophrenia [

5], whereas bizarre experiences and the absence of reality testing are most likely depending on a reduction of frontal cortex activity, especially as far as the dorsolateral areas are concerned [

6]. Finally, the physiological basis for emotional involvement could be the remarkable activation of amygdala and other limbic areas, clearly showed by functional neuroanatomy in both REM sleep [

4,

7] and schizophrenia [

8].

These similarities clearly bear implications for both psychopathology and research on dream processes. On the one hand, it has been suggested, in the past, that dream may represent a natural model for psychosis (e.g., [

3]) and it has also been speculated that schizophrenia could be a kind of “trapped state” between waking and dreaming, with the encroachment of experiences usually occurring in dreams into another state of consciousness [

9]. In other terms, sleep would somehow intrude wakefulness, provoking the emergence of dream features in what should be the normal, “lucid”, waking ideation.

For sleep and dream researchers, however, the dream-psychosis relationship is also extremely interesting the other way round, i.e. addressing the influence of wakefulness on sleep mentation and the possibility that specific predictions can be made on psychotic patients’ dreams given the peculiar characteristics of their disorder. As a matter of fact, there are solid research lines trying to understand whether and to what extent waking experience is reflected in dreaming, in line with the widely held “continuity hypothesis” according to which a thematic continuity would exist between waking-life experiences and dreams [

10].

Last but not least, the relationships between wakefulness and dreams would be reflected not only in dream content, but also in its associated emotions [

11]. Notably, a primary function of sleep for emotion regulation has been repeatedly proposed, also in light of REM sleep’s peculiar neurotransmitters balance, which is believed to provide optimal conditions for offline processing of affects (see [

12] and, for a review, [

13]). Our own group has recently shown that poor sleep quality might impair sleep-related processes of affect regulation [

14]. Thus, we deem extremely interesting to look at dream features in the disturbances of the schizophrenic spectrum, where emotional dysregulation is a key characteristic.

According to what said so far, waking-life psychotic symptoms could be directly linked to specific dream characteristics. When coming to schizophrenia and the whole of schizophrenia spectrum disorders, this would imply that psychiatric symptoms could be predictors of differences in the dreams of psychotic patients relative to those of controls. However, probably due to the methodological difficulties of collecting dream reports in patients suffering from schizophrenia, the data available on this topic are still very sparse and foggy.

Dream reports in schizophrenia were found to be shorter in a number of rather old studies (e.g., [

15,

16,

17]), but their results were obtained with different methodologies and did not clarify whether they were accounted for by an actual reduction in dream generation or by patients’ reduced ability to recall and report their dreams, e.g. due to the impairment of verbal fluency repeatedly shown in schizophrenia [

18].

Concerning their qualitative features, schizophrenic patients’ dream reports, compared to healthy controls’, were occasionally displaying reduced emotional involvement and emotional expression [

19,

20], less affect and less change in dream scenery [

21], more frequent presence of familiar people [

22] or of strangers [

23,

24], less words referring to the semantic field of hearing and a less active role of the dreamer [

20].

Cognitive bizarreness – a distinctive property of the dreaming mental state defined as “impossibility or improbability in the domains of dream plot, cognition and affect” [

25] - has been considered as a cognitive marker shared by psychotic waking and dreaming state, but to what extent the high bizarreness in schizophrenic patient’s waking ideation is maintained during dreams is still an open issue. Early studies found less bizarreness in schizophrenic patients’ dreams in comparison to the dreams of a normal control population [

15,

26,

27], whereas more recent literature seems to point to equal [

24] or even higher bizarreness scores in schizophrenic patients [

28]. Interestingly, a study by Scarone et al. [

29] showed that a comparable degree of formal cognitive bizarreness was shared by the waking cognition of schizophrenic subjects and the dream reports of both normal controls and schizophrenics.

According to the continuity hypothesis, the magnitude of the differences between controls’ and schizophrenic patients’ dreams could increase as a function of their severity [

30]. Schredl and Engelhardt [

31] found significant correlations between the scores at the Symptom-Checklist-90-R scales and dream reports features: the scores for depressive symptoms correlated with emotional tone, whereas ‘‘psychoticism” and ‘‘paranoid ideation” scales correlated with dream bizarreness, both in the sample of patients with a specific related diagnosis (major depression and schizophrenia respectively) and in the sample of patients affected by other mental disorders. These data suggest that it is the severity of specific symptoms (such as depressive mood or psychotic symptoms), rather than the diagnostic classification, to be primarily related to dream content.

Contrasting results have been obtained in the abovementioned study by Scarone et al. [

29], who found no correlation between the severity score at the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (from now on BPRS) and dream bizarreness in a sample of schizophrenic patients. This disagreement between studies could be due to the different instruments used to assess psychopathology.

In sum, this sparse and contrasting literature does not allow to draw clear conclusions on the relationships between dream features and psychosis. Therefore, here we compare dream reports of schizophrenic patients to those of healthy controls with regards both to quantity (Dream Recall Frequency, from now on DRF) and quality (length, content), in order to provide further data to enlighten the issue of whether psychotic symptomatology is reflected in dream content. Within the frame of this general objective, we specifically intend to focus on a few issues that have been covered very little, if at all, by previous research: a) the relationship of dream features with illness severity, as measured through the BPRS; b) the possible role of lexical access ability, indexed by verbal fluency performance, in affecting dream reports’ length; c) the amount and types of emotions reported in dreams in the clinical vs. the control group.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Our sample includes 46 patients with diagnosed psychotic symptoms (F 10, M 36, age range: 19-54 years, mean age: 35.7 ± 10.6) recruited at two residential facilities (Rehabilitation Community “Beyond dreams”, Sessa Aurunca (Caserta), Italy, n=26) and a day-treatment center (“Integrazioni”, Casoria (Napoli), Italy, n=20), as well as 28 healthy control subjects (F 17, M 11, age range: 20-59 years, mean age: 33.0 ± 6.8), who volunteered at the University of Campania “L.Vanvitelli” (Caserta, Italy), recruited among psychology students and their relatives and friends.

The main inclusion criterion for the patients’ group (PG) was having a diagnosis of schizophrenia or any other psychotic disorder according to DSM-V criteria (APA, 2000), including schizoaffective disorder. All patients were being treated with combined individual and group integrative psychotherapy. Family therapy was also followed by 24% of the subjects. Pharmacological treatments, that had to have been stable for at least three weeks before the study, were distributed as follows: no medication, 10.9%; mono therapy with antipsychotics 32.6%, polytherapy with antipsychotics with tranquilizers and/or hypnotics, 56.5%). Other inclusion criteria were: a) absence of comorbidity with other psychiatric or neurological disorders; b) no evidence of mental retardation; c) for inpatients in the residential facility, having stayed there for not less than 1 month and not more than 18 months.

As for the healthy control group (CG), inclusion criteria were: a) age between 18 and 60; b) absence of any history of organic and/or psychiatric disturbances; c) absence of any history of sleep disorders; d) regular sleep habits, evaluated through the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Italian Version [

32]. Also, only subjects who reported to recall at least one dream per week were recruited.

All demographic characteristics of the two samples, including clinical diagnosis, therapies for the patients’ group, are listed in

Table 1.

2.2. Procedure

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Department of Psychology, University of Campania (Italy). After providing information about the study, consent forms from both patients and healthy controls were obtained.

Before dream reports collection, psychopathological severity of each PG participant was evaluated through the BPRS, Expanded Edition 4.0 [

33] during a one-hour individual therapy session. Moreover, a verbal fluency test [

34] was administered to the same group to evaluate lexical access ability.

Participants were requested, 5 days a week (over a period of 30 days for the patients group and of 15 days for the healthy controls), to report, immediately at spontaneous awakening, the mental activity they had memory of through the following classical instruction (presented in written form): "Please tell me everything you can remember of what was going through your mind before you woke up.” [

35]. For patients in the residential facility, it was the facility staff who solicited them to fill in the diaries and questionnaires at awakening, whereas patients from the day-treatment center and normal controls were instructed to write down or audio-record their dreams first thing after awakening.

2.3. Instruments

For psychotic symptoms’ severity assessment, we administered the BPRS [

33], in its Italian version [

36]. The severity of each one of the 24 symptoms is rated on a scale from 1-7, ranging from 1 (Absent) to 7 (Extremely severe). Ratings are based both on the patient’s answers to the interviewer’s questions and on the observed behavior during the interview. According to total BPRS total score, psychotic subjects were assigned to one of seven severity groups (Absent 0-24, Very Mild 25-48, Mild 49-72, Moderate 73-96, Moderately severe 97-120, Severe 121-144, Extremely severe 145-168).

The Verbal Fluency Test used in our study [

34] consists in two tasks: Semantic fluency and Phonemic fluency. Subjects are given 1 min to produce as many words as possible within three semantic categories (i.e., “Car brands”, “Fruits”, “Animals”) or starting with three given letters (i.e., “P”, “F”, “L”), respectively. Total scores for both tasks correspond to the total number of words generated at each task. These scores are then corrected for age and education in order to obtain equivalent scores from 0 to 4, where 0 is considered “pathological” and 4 “above normal”.

2.4. Dream Analysis

Dream reports were evaluated by two independent raters, with a third rater, blind to the design and aims of the research, called to resolve possible disagreements. Whenever the subjects claimed that they had made “more than one dream”, if they referred them to different bouts of sleep, only the report of the dream preceding the awakening was taken into account. Otherwise, the different dreams were considered as a single report.

Dream Recall Frequency (DRF) is defined as the percentage of days in which a dream report was obtained over the whole number of days of the protocol.

Length of reports was measured in temporal units (TUs) according to Foulkes and Schmidt’s method [

37]. A TU is assigned whenever: a) a character performs an action that, in waking life, could not be performed synchronically with his/her previous action; b) a character responds to another character or event; c) there is a topical change in the dream report.

Following Occhionero and Cicogna [

38], type of Self-representation was coded into six categories:

1) Presence of Self as a pure thinking agent;

2) Total or partial Self body image, more or less associated with proprioceptive, kinesthetic, agreeable or painful sensations;

3) Representation of Self as a passive observer of the dream events;

4) A precise hallucination of both mind and body, analogous to wakefulness;

5) Identification with other characters in the dream;

6) A double representation of Self with two distinct and relatively active roles.

A seventh category – 0) Absence of Self-representation both as a physical entity and as thinking subjectivity – was added here to describe reports in which it is not possible to identify any type of self-representation.

A number of dream content dimensions (as in [

39]) were analyzed through a set of dichotomous categorical variables (presence/absence of that feature in the dream report):

- -

Continuity, scored as present when the report’s narrative structure did not show sudden interruptions or changes of main settings or characters (when the report was described as containing more than one dream, no continuity was assigned)

- -

Impossibility/Implausibility Bizarreness, referring to events whose occurrence is implausible during wake;

- -

Space/Time Bizarreness, referring to spatiotemporal distortions;

- -

Perceptive Bizarreness, referring to images, characters or objects with distorted shapes, colors or dimensions;

- -

Emotions, referring to spontaneously verbalized emotions which are clearly expressed by the subject and felt by the dreamer himself during the dream (other characters’ emotions reported by the dreamer were not included);

- -

Positive Emotions;

- -

Negative Emotions;

- -

Somatic Sensations, referring to spontaneously verbalized somatic sensations clearly expressed by the dreamer;

- -

Non-self Characters, referring to any additional character besides the Self;

- -

Unknown Characters, referring to strangers or unfamiliar characters, appearing as single individuals or undefined groups;

- -

Interactions, referring to direct (Self) and indirect (Others) interactions between characters;

- -

Friendly Interactions, referring to friendly direct (Self) and indirect (Others) interactions between characters;

- -

Aggressive Interactions, referring to aggressive direct (Self) and indirect (Others) interactions between characters;

- -

Sexual Interactions, referring to sexual direct (Self) and indirect (Others) interactions between characters;

- -

Setting, referring to a specific, clearly identifiable setting in which the oneiric scene takes place.

Three dream content dimensions were also assessed as continuous variables:

- a)

emotions (only those spontaneously verbalized by the subject in the dream report are included in scoring these variables): total number of emotions (including both the dreamer’s and other characters’ emotions), number of self (dreamer’s) emotions, number of non-self (other characters’) emotions;

- b)

characters: number of characters (these were scored only when they appeared as single individuals: both familiar and unknown characters were included but the dreamer and undefined groups were excluded);

- c)

interactions (all actions identified by verbs clearly referring to interactions): total number of interactions, number of self-interactions (those between the dreamer and other characters), number of non-self interactions (those between two or more non-self characters).

These continuous variables were all analyzed both as absolute numbers and as percentage over the number of TUs.

2.5. Statistics

A Kruskall-Wallis ANOVA was conducted to test between-group (CG vs PG) differences in dreams variables. Except for the analysis of between-groups differences in (DRF) and white reports frequency, patients producing 0 dream reports over the whole data collection period were excluded from the analysis (N = 19). Spearman’s correlation coefficient (rr) was used to detect possible correlations between age, global score at the BPRS, verbal fluency (phonemic and semantic), and dream variables in PG. Between-group differences in age and years of education were assessed with the Mann-Whitney U test, whereas differences in gender distribution with the Chi-Square (χ2) test.

All analyses were performed with Jamovi 2.3.21 (The Jamovi Project, 2023), and the statistical significance level was set at p ≤ 0.05. Descriptive statistics are reported as mean ± standard deviation.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Sample

The two groups did not differ in age (total sample: 35.7 ± 10.6; CG: 33.0 ± 6.8; PG: 36.0 ± 11; U = 99.5, p = .634) but differed in gender (total sample: F 27, M 47, CG: F 17, M 11; PG, F 10, M 36; χ2 = 6.81, p = .009) and years of education (CG: 16.0 ± 2,7; PG: 11.4 ± 2.3, U = 28.0, p = .003).

More than half of the cases (56.5%) are schizophrenias of the paranoid and disorganized types, whereas the remaining 43.5 % is divided between unspecified schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and schizotypic personality disorders. Only 5 patients are actually drug-free and 26 of them are taking benzodiazepines and/or hypnotic drugs in addition to antipsychotic medications.

Table 1 summarizes the patients’ characteristics derived from initial clinical assessment, namely diagnoses, pharmacotherapies, BPRS score and Verbal Fluency.

3.2. Inter-Rater Agreement

Inter-rater agreement turned out to be satisfactorily high both for the analysis of temporal units (r=0.94) and for that of content variables (r=0.92).

3.3. Dream Recall Frequency

Nineteen patients did not produce any dream report across the entire data collection period (non-recallers: 41.3%). Instead, all the healthy controls produced at least one dream report. A total of 159 dream reports were obtained from the patients’ group over the 30-days study period while controls’ dream reports were 111 overall. Therefore, DRF in the patients’ group was significantly lower than in controls (18% ± 1.33 vs. 27% ± 4.25, χ21 = 9.30, p = .002). In PG, non-recallers did not differ from recallers in age, years of education, and gender distribution, but significantly differed in BPRS global score, reporting higher severity of psychopathological symptoms (

Table 2).

DRF did not significantly differ between in-patients (21.61 ± 1.71) and patients treated at the day-care facility (i.e., sleeping at home) (13.23 ± 2.26; χ21 = 3.8, p = .060).

In PG, a significantly higher proportion of contentless dreams, i.e., “white reports”, was referred by schizophrenic patients compared to controls (PG: 4.00 ± 0.40 vs. CG: 0.00 ± 0.00, χ21 = 8.12, p = .004).

3.4. Between-Group Differences in Dream Report Features

Overall, PG reported significantly lower DRF and shorter dream reports than CG, and dream recall length was higher in the in-patients group (2.70 ± 1.20) relative to the day-care facility patients (1.62 ± 0.77; χ21 = 4.48, p = .034).

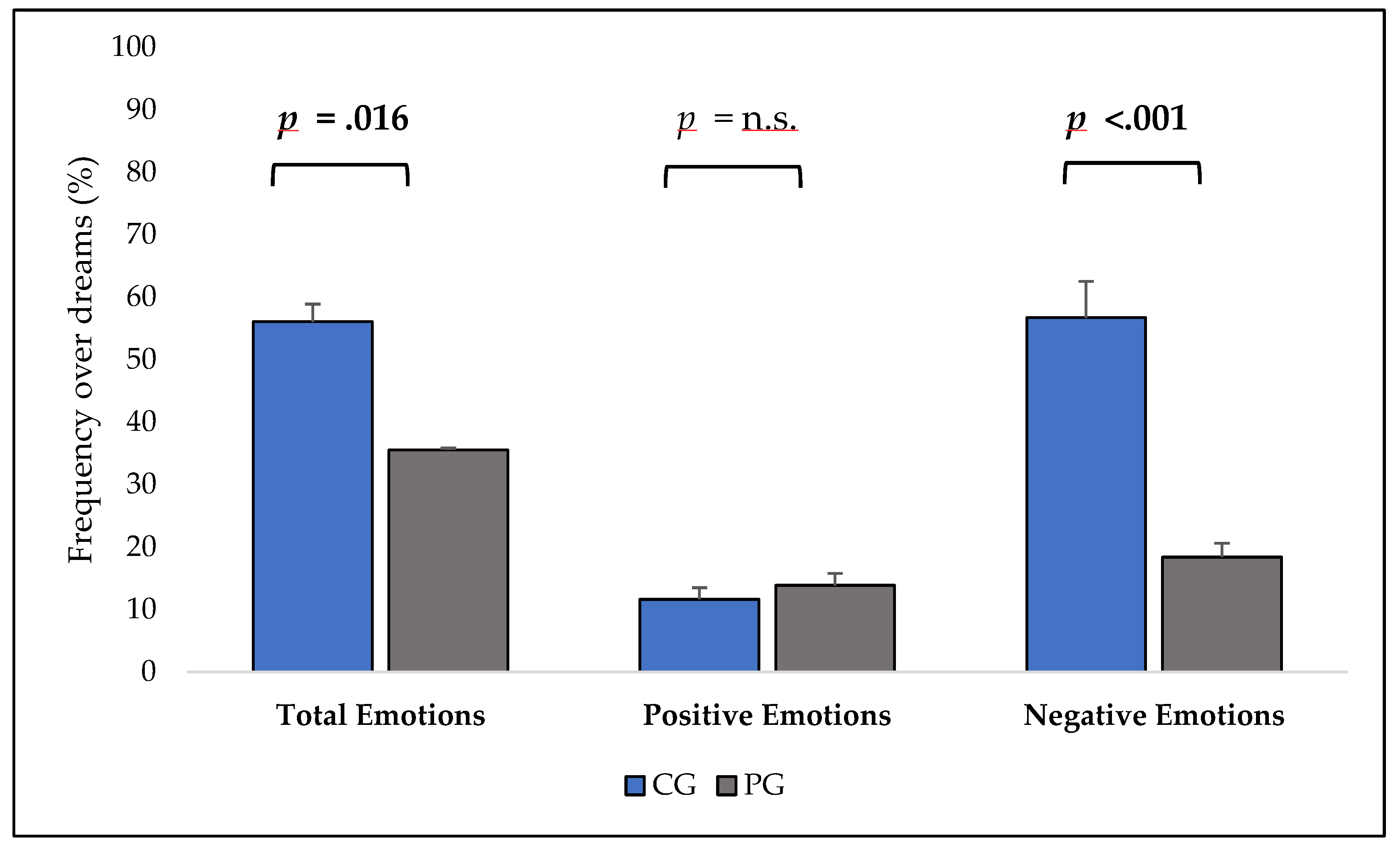

In addition, dream reports in PG were characterized by a significantly decreased number of emotions (

Figure 1), reduced presence of non-self, unknown, and total characters, less interactions and a higher frequency of a precise setting. Furthermore, PG reported higher space/time bizarreness (see

Table 3 for the complete results).

The two groups did not differ in the type of Self-representation in dreams (

Table 4).

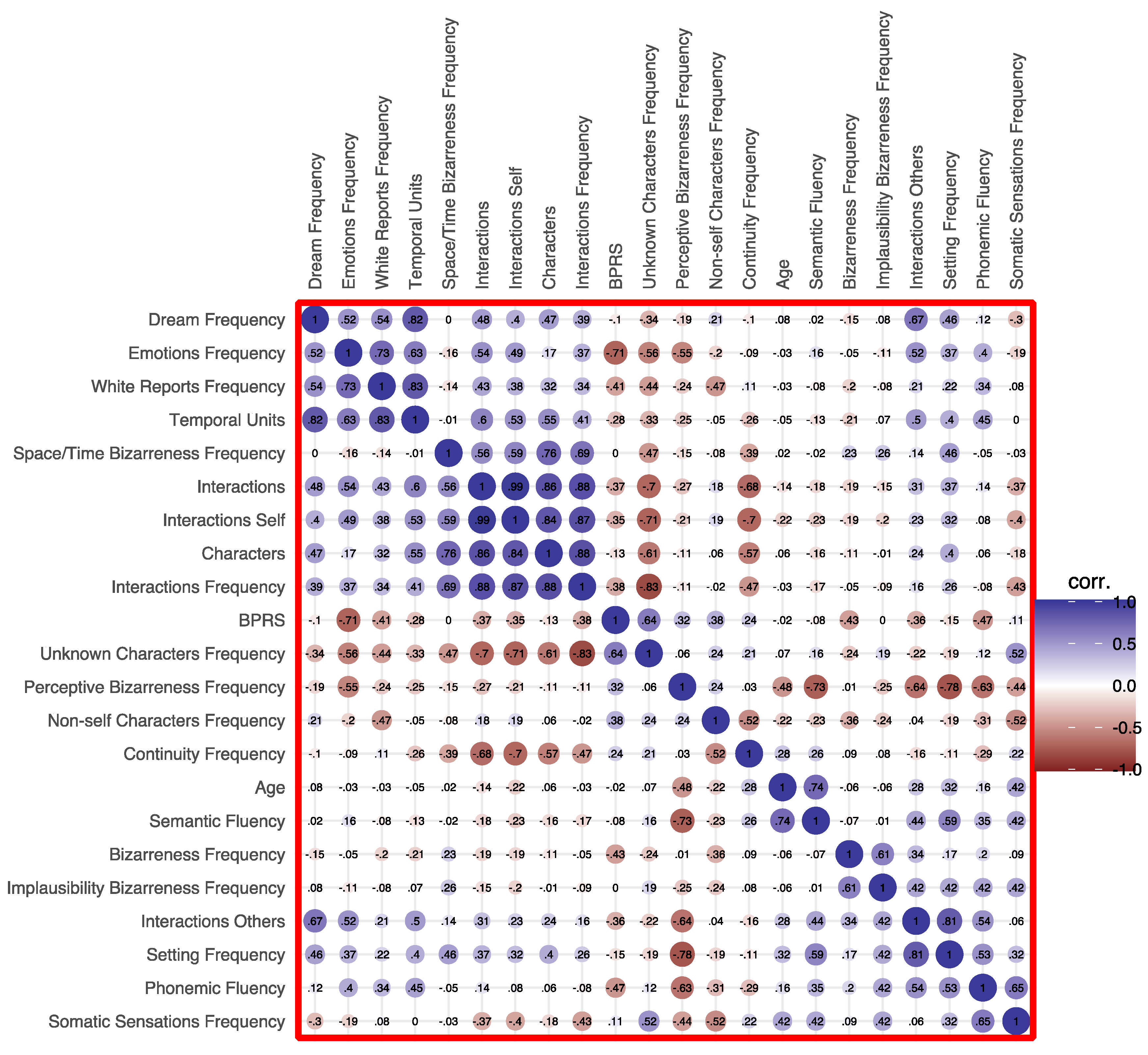

3.5. Associations in Patients’ Group between Age, Severity of Symptoms and Verbal Fluency with Dream Variables

Spearman’s correlation analysis yielded a few significant correlations between age and dream features, in that older age was correlated with a higher frequency of white reports (rr = .526, p = .005), whereas young age was correlated with a higher frequency of dreams with general bizarreness (rr = –.389, p = .045) and implausible contents (rr = –.410, p = .034).

As for BPRS, its global score was positively correlated with the frequency of non-self-characters in dreams (rr = .423, p = .028) and negatively correlated with the number of emotions (rr = –.419, p = .030), but not with DRF (rr=.208, ns) and dream recall length (rr= - .209, ns).

Finally, regarding verbal fluency, phonemic fluency positively correlated with dream report length (i.e., temporal units; r

r = .636, p = .040) and frequency of somatic sensations (r

r = .645, p = .037). Furthermore, both phonemic and semantic fluency were negatively correlated with frequency of perceptive bizarreness (r

r = –.634, p = .036 and r

r = –.730, p = .011 respectively). The full heatmap for correlations is depicted in

Figure 2.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the very few studies analyzing the dream characteristics of a fairly wide sample of individuals with psychotic symptoms (relative to healthy subjects) in their habitual life context, and assessing the relationships between their dream features to their illness severity and lexical ability.

Consistent with previous findings [

15,

23,

26], our study shows in the individuals suffering from psychotic disturbances a decreased DRF in comparison with healthy subjects. Also, dream reports are shown to be shorter in this group, which is also in agreement with a number of past results [

15,

16,

17,

29]. When interpreting these data, however, it is always very difficult to understand to what extent they depend on a reduced oneiric production or, instead, on a lower efficiency of dream recovery processes in schizophrenic subjects. This is a well-known issue in all those populations who show a similar quantitative reduction in dreams, such as the elderly [

40]. Here, the overall low DRF in the patients’ population is largely accounted for by the rather high percentage of complete non recallers, dramatically decreasing the DRF value, which would be otherwise similar between patients and healthy controls. Secondly, we showed a rather high proportion of contentless reports in the patients’ sample (those mental activities the subjects are aware of but whose content they are unable to verbalize, also called “white reports”). Finally, it is of interest that non recallers show a significantly higher BPRS and that the latter is negatively correlated with phonemic fluency. Therefore, illness severity would be a relevant factor in hindering the dream recall processes, possibly via an impairment of lexical access ability.

Concerning dream content, a quite solid profile emerges of a global poverty of patients’ dreams relative to those of healthy subjects. In their reports there are less characters, less settings, a lower number of total interactions, accounted for by the reduction of friendly and aggressive ones, both referring to first-person interactions or to other people’s interactions witnessed as an observer. It does not come as a real surprise that bizarreness is not enhanced in PG, except for an increase of the space-time type, not determining a significant change in the total score. This result goes in support of other previous findings showing that the gap between patients and controls in bizarre cognition during wakefulness is filled during dreams [

29].

One of the core results of this study refers to the rather impoverished emotional pattern of schizophrenic patients, with a decreased average number of emotions (paralleled by a lower number of reports in which emotions are expressed). Strikingly, this result, which is concordant with previous data [

19], almost totally depends on the significant reduction of negative emotions. Apparently, the classical phenomenon observed in healthy subjects of negative dream emotions prevailing over positive ones [

41,

42] appears inverted in psychotic individuals. Considering that this phenomenon in healthy subjects has been interpreted as a possible index of the role of dreams in emotion regulation (e.g., [

11,

14]), our result on the patients’ group comes as an impressive counterpart of their severe emotional dysregulation during wakefulness and warrants further investigations, e.g., in terms of its magnitude as a function of illness severity, given that, in our sample, the more severe the disturbance, the less emotional the dream report.

Another interesting finding is the lack of differences between CG and PG in the representation of Self and one’s own body. This feature has been occasionally described in healthy subjects [

38,

43,

44], with data pointing to the presence of changes in the representation of the Self according to age and to the sleep state from which the dream is recalled (being more similar to wakefulness in REM sleep dreams and more polymorph in NREM sleep dreams). To our knowledge, this is the first time that Self representation is assessed in a clinical population. Even on this aspect, there appear to be no particular atypical characteristics transposed from wake symptomatology to the dreaming experience. The same can be observed for the frequency of somatic sensations, which also does not differentiate PG from CG.

The findings in this study have to be interpreted cautiously in light of a crucial methodological issue. In fact, here we decided to address our sample, especially the patients’ group, which has very peculiar characteristics and needs, in the most ecological way possible, i.e., by collecting data at spontaneous awakening in the habitual living context. This approach is somewhere in between the rigor and the high level of experimental control achieved by asking for dream recall at provoked awakenings in the lab - which is however an extremely difficult procedure for clinical samples as demanding and delicate to deal with as the patients affected by psychoses - and the retrospective interviews, much easier to collect but very unreliable in terms of waking interference and content bias [

24]. Both meaningful advantages and limitations of this study actually come at the same time from this methodological choice. On one hand, our sample of patients is quite large compared to most literature on the topic, and the design of the study allowed to have a fairly extended collection period (30 days in PG, 15 days in CG), definitely of little feasibility with a laboratory protocol (this usefully enlarged the total number of dream transcripts despite the low DRF expected). Also, the patients’ habitual sleep habits were respected, allowing to rule out the insertion in dreams of a non familiar environment (see the interesting discussion on that in [

45]). On the limitations’ side, however, the lack of prompted reports, soliciting dream recall with more effectiveness and completeness than the mere spontaneous report, does not allow us to obtain conclusive evidence on the role of memory retrieval impairments in the scarcity and poorness of dream reports. Furthermore, it is obviously difficult to control for the actual adherence of the persons sleeping at home (control subjects and the patients of the day care center) to the instruction of reporting their dream immediately at awakening. Lastly, with our design we cannot get objective sleep data, making it impossible to relate dream report changes to the sleep states the awakening emerges from.

A final speculation should be reserved to the issue of whether the present findings are in favor of the “continuity hypothesis” [

10], whose original formulation might be usefully reported here: “

(…) dreams are continuous with waking life; the world of dreaming and the world of waking are one. The dream world is neither discontinuous nor inverse in its relationship to the conscious world. We remain the same person, the same personality with the same characteristics, and the same basic beliefs and convictions whether awake or asleep. The wishes and fears that determine our actions and thoughts in everyday life also determine what we will dream about”). It still seems hazardous to us to answer such a question in a straightforward manner. In our study, the massive misperceptions, hallucinations, bizarre and disorganized thoughts and behaviors that are commonly associated to the psychotic experience do not seem to emerge in dreaming, at least not more pronouncedly than in healthy subjects. However, the manifestations of psychoses, especially in patients who have a long history of the disease and are chronically medicated, are often rather characterized by a prevalence of cognitive symptoms, such as remarkable deficits in working memory and attention [

46]. Therefore, to what extent the impoverished dream reports found in our sample are a result of a “continuity” with waking clinical features remains an open issue, which could prompt, in the future, to characterize patients in a more refined way, e.g., through the use of instruments assessing day-by-day symptomatology in the positive, negative and cognitive dimensions.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed in a meaningful way to this manuscript. Conceptualization, G.F. and F.C.; methodology, O.D.R., A.L., G.F.; formal analysis, O.D.R., D.G., T.M., A.C., B.A., A.L.; investigation, D.G., T.M., B.A., S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C., G.F., F.C.; writing—review and editing, G.F., F.C., O.D.R., A.L.; supervision, G.F. and F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.