1. Introduction

1.1. Living with Young Onset Dementia

Young or early-onset dementia is when a person is diagnosed with a form of dementia while under the age of 65 [

1]. Living with younger onset dementia can be very different to the stereotypical image of dementia that is prevalent in society. An important factor is that for many younger people, getting a diagnosis of dementia often occurs when they are still working [

2]. Many people are forced to leave their employment or leave voluntarily if they feel they are unable to continue to manage their work. Loss of income can have a significant impact, both financially and mentally. This can be especially stressful if the person still has dependents at home [

3]. The unexpected nature and presentation of younger onset dementia and can also mean diagnosis takes longer than for those with older onset [

4]. People can also become socially isolated when they lose their work networks and friends that disappear [

2,

5].

This paper was co-written by The Smarties, a team of six researchers living with young onset dementia who worked alongside the academic researchers to conduct the research. The co-authors noted that young onset or early onset are used interchangeably, with choice determined by personal preference. However, for continuity this paper will continue using the term young-onset dementia. The co-authors living with dementia felt the most important thing for people to know about young onset dementia is that there is no one way a person with young onset dementia looks. Often, they are told ‘you are too young’ or ‘you don’t look like you have dementia’, which can invalidate their experiences and is an example of the stigma that they face [

6]. They also shared some juxtaposing opinions on getting a diagnosis, with one co-researcher reporting the experience as a loss,

“I lost my job three months after my diagnosis and I felt as though I had lost my life.” Whereas another felt that it could be positive “I

t felt like freedom as I was no longer tied to the work clock.” What these differing opinions reinforce, is that having dementia is different for everyone and how important it is to be aware of the individual behind the diagnosis. As one co-researcher said,

“I want people to see the me in Dementia.”

Despite the clear differences for people living with younger onset dementia, specialist services and support are lacking in the UK and are often not stage or age appropriate [

7,

8,

9]. Services that are typically tailored towards older people and can feel inappropriate for younger people if they feel like they are the only person there from their age group, or the activities are tailored towards the wrong era [

7]. Where appropriate services exist, access can vary by geographical location [

10]. This is what is known as a ‘post-code lottery’, a British term that draws attention to the differing quality of services that are determined by where you live [

11]. For example, one co-researcher pointed out that in Scotland, the central belt tends to be prioritised for flagship projects, and in counties that cover a larger geographical area such as Aberdeenshire, it can be harder to co-ordinate and arrange projects.

1.2. Volunteering

A potential option to meet the needs of people living with younger onset dementia in the UK could be through the creation of volunteering opportunities as a form of social prescribing [

12]. Volunteering could enable people to remain socially connected, embedded within their communities, and to take part in activities that are personally meaningful [

13,

14]. As Bartlett and O’Connor [

15] (p. 99) state in their exploration of social citizenship for people with dementia,

“Work, whether it is paid or unpaid, is arguably the single most important aspect of being a citizen.” While definitions of volunteering can vary greatly, for the purpose of this article we are choosing to define volunteering as the doing of something to make a difference, voluntarily, and without any expectation of reward of remuneration [

16]. Volunteering can be formal, such as projects hosted and facilitated by an organisation, or informal, such as doing the shopping for a neighbour.

This study chose to focus on the experiences of people living with young onset dementia who volunteer to understand more about how they do it and what barriers and enablers are present. This approach was guided by the recognition of the paucity of literature that explores living with dementia and volunteering, and because an exploration of this perspective was identified as important by the co-researchers who are living with dementia. Anecdotally, it appears that people with younger onset dementia in the UK predominantly volunteer in the dementia field, through activism, campaigning, and research participation. However, as one co-researcher noted opportunities to engage in meaningful research can vary by location. Volunteering opportunities tend to be accessed through involvement with lived experience groups such as the 3 Nations Working Group [

17], the Scottish Dementia Working Group [

18], and through the DEEP (Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project) networks [

19]. While most opportunities appear to be within the dementia field, there are examples of people doing alternative forms of volunteering, such as one co-researcher volunteered at a hospice post-diagnosis.

However, there are no data that we could identify to create a picture of the landscape of volunteering with dementia in the UK. This is perhaps due to the service-delivery model of volunteering that we have in the UK that positions one person as ‘the helper’ and another as ‘the helped’ [

20,

21]. Given the way that people with dementia tend to be positioned in terms of deficit and decline, they are likely to be presumed to be unable to be ‘the helper’ and are assumed to be ‘the helped’ [

22]. Furthermore, research has demonstrated that people with disabilities tend to be underrepresented in volunteering [

21]. Institutional factors and stigma act as significant barriers to involvement in volunteering by Disabled people [

23,

24]. These barriers are likely relatable to volunteering with dementia, as too often people feel like, as one co-researcher shared,

“just put on the rubbish pile” once they get a diagnosis of dementia. They experience what dementia activist Kate Swaffer has termed ‘prescribed dis-engagement’ [

25] where once a person receives a diagnosis of dementia they are treated as if they should give up all their interests and get their affairs in order.

Across the academic literature volunteering with dementia is markedly under-explored [

26]. Richardson et al. [

26] conducted a systematic review of the area and of 498 articles that were screened, they were only able to include three that met their inclusion criteria. These were Kinney et al. [

27] whose paper reports on a work-placement scheme at a zoo for people with early to late-stage dementia. Participants took part in educational activities and undertook supervised work activities. Secondly, Hewitt et al. [

28] also report on a work placement, where people with young onset dementia took part in gardening tasks and spent time discussing their work as a group. Finally, Robertson and Evans [

29] report on a project where people with dementia were matched with a work buddy in a hardware store to undertake tasks. Across the three studies from the systematic review, there were only small numbers of participants (n<12), however, there were overwhelmingly significant benefits reported by participants and their loved ones. Benefits to volunteering included increased social connections, a sense of meaning and purpose, improved wellbeing, giving something back and respite for carers. Findings that are echoed by a study by Söderlund et al. [

30] that explored the experience of people with dementia who volunteered at meeting centres. The researchers found that the work created opportunities for volunteers to develop social connections and to share their knowledge.

Outside of the academic literature, an example of a volunteering project designed specifically for people with dementia is DemenTalent [

31]. An organisation based in the Netherlands, DemenTalent supports people with dementia to volunteer in their community in a variety of roles, taking into consideration each person’s unique talents. The organisation offers a variety of volunteering projects and provides training for new start-ups. In a randomised controlled trial that took individualised support programs that included DemenTalent (n=11) and compared them with regular support programs (n=13) (both based in meeting centres), the researchers found that the support programs that included DementTalent were associated with an increase in positive affect and a positive effect on neuropsychiatric symptoms for participants, and lower emotional burden on caregivers [

32]. Furthermore, in their exploration of the implementation of DemenTalent in meeting centres, Van Rijn et al. [

33] found that stakeholders in the process most frequently referenced how human and financial resources were essential to the implementation being effective. Interestingly, the success of the organisation and its work is evidenced by its inclusion in the Dutch National Dementia Strategy 2021-2030 [

34]. However, for people in the UK there is no comparable program to support their involvement as volunteers.

Clearly, there needs to be a greater exploration of volunteering for people with young onset dementia in the UK. From the literature we can see that volunteering could be of benefit to people living with dementia and their loved ones. However, several barriers to volunteering have been found, such as stigma, prescribed disengagement [

25] and opportunities to access. More research is needed to look at the experiences of people with dementia who engage in volunteering in the UK to help us to begin to understand how we can create more opportunities and reduce barriers to accessing its benefits.

1.3. Aims

The aim of this paper is to explore how people with dementia volunteer in the UK. This includes a consideration of the benefits gained through volunteering, what barriers people may encounter in accessing volunteering opportunities, and to understand what supports or enablers are needed to improve access to volunteering for people with dementia.

2. Materials and Methods

While the focus of this paper is the findings about volunteering with young onset dementia; given the novel approach to collaborative thematic analysis employed, we will briefly describe who the co-production group are and how we worked together, the data collection methods and summarise our framework for thematic co-analysis.

2.1. The Smarties

The Smarties are a co-production group of six people living with young onset dementia and two academic researchers without dementia. The group met for eleven online workshops between June 2021 and February 2022. We chose to conduct this research in a co-produced way, focussing on creating a shared agenda, being democratic and working in a way that empowered both the researchers with and without dementia. Researching alongside people with lived experience helps to ensure the research is relevant and of importance to people who are living with a condition [

35]. Furthermore, lived experience researchers can offer unique insights on data that academic researchers may not reach on their own [

6]. We were guided by the key principles of co-production (sharing of power, including all perspectives, respecting and valuing the knowledge of all those working on the research, reciprocity, building and maintaining relationships and joint understanding) [

36].

In the following section we introduce the data we used for the analysis and detail how it was collected.

2.2. Data Collection

The secondary audio data used in this study came from the Dementia Diaries. Dementia Diaries is an audio diary project that brings together the personal experiences of people living with dementia from across the UK. Diarists record their audio diaries from home and can chose to discuss whatever they like. The diaries are uploaded onto the website and transcribed by volunteers. Thus, the diaries are openly accessible and there was no need to obtain informed consent from the diarists. However, R.E.V shared an accessible summary of the research with the diarists, so they were aware of how their diaries were being used. Finally, it felt inappropriate to anonymise or pseudonymise the diarists’ names in this paper, given they have chosen to share their experiences and be named on the internet precisely because they want their words to be shared widely to increase understanding of what it is like to live with dementia.

Some of the diarists are also members of The Smarties. To manage this, R.E.V checked with each person to see if they would prefer to have their diaries removed from the analysis, none of the group chose this option. At the workshops where a Smarties members diary was discussed, R.E.V checked in with the member to ensure they were happy to continue and advised if they felt uncomfortable at any stage to let her or R.A aware.

We collected diaries from the repository from 2015 (the beginning of the project) up until June 2021, using the following search words (volunt*; doing; giving; contribut*; helping; befriend*; buddy; charit*; goodwill; support*; campaign*; freely giving; research; assisting; aiding). Diaries were excluded if they were clearly not related to volunteering or voluntary activity, where we were unable to confirm if the diarist had young onset dementia, recorded speeches from events, group conversations, when a diarist was reading aloud from books, and duplicates.

The Smarties developed the following research questions to analyse the diaries.

Who volunteers and in what way?

What rewards or benefits do they get from volunteering?

What barriers or hurdles do they face with volunteering?

What allies or supporters do people need to volunteer?

426 diaries were identified that included key search words and related to our research questions. The diaries came from 42 different diarists (W = 47.6%, M = 52.4%). Over eight workshops we reviewed 37 diaries. Diaries were selected by R.E.V by concurrently working through the diarists alphabetically, and the research areas of interest (i.e., benefits, barriers, allies). The group voted for the diaries they felt were most important to be included in the analysis. In total, the group analysed 14 of the diaries.

In the following section we briefly summarise the framework of thematic co-analysis used by The Smarties to explore people’s experiences of volunteering with dementia.

2.3. Qualitative Analysis

Thematic Analysis is a commonly used qualitative method for analysis that involves looking for

‘patterns of shared meaning across a data set’ [

38] (p. 592). As an analytic technique it is useful for participatory, or co-produced methods because it does not require the researchers to have any specific understanding of certain theoretical constructs and is compatible with exploring lived experience [

39]. This research was inspired by Braun and Clarkes reflexive thematic analysis in that we wanted it to be

“creative, reflexive and subjective, with researcher subjectivity understood as a resource” [

38] (p. 591). Their six-steps were used as guide, but adapted to suit our specific needs as a group of people living with dementia researching in partnership online in what we call ‘thematic co-analysis’. For step one we familiarised ourselves with the data. Step two involved the developing of initial analytic thoughts by using body mapping as a visual aid to encourage creative and reflexive engagement with the data [

40]. For step three we began the process of condensing our initial analytic thoughts to ensure they were relevant to our research questions. Step four involved further refining of the analytic thoughts generated by the group. Finally, step five was the writing of our themes in a collaborative way, done through the recording and transcription of group discussions.

In the next section we detail the themes that were developed through our analysis.

3. Results

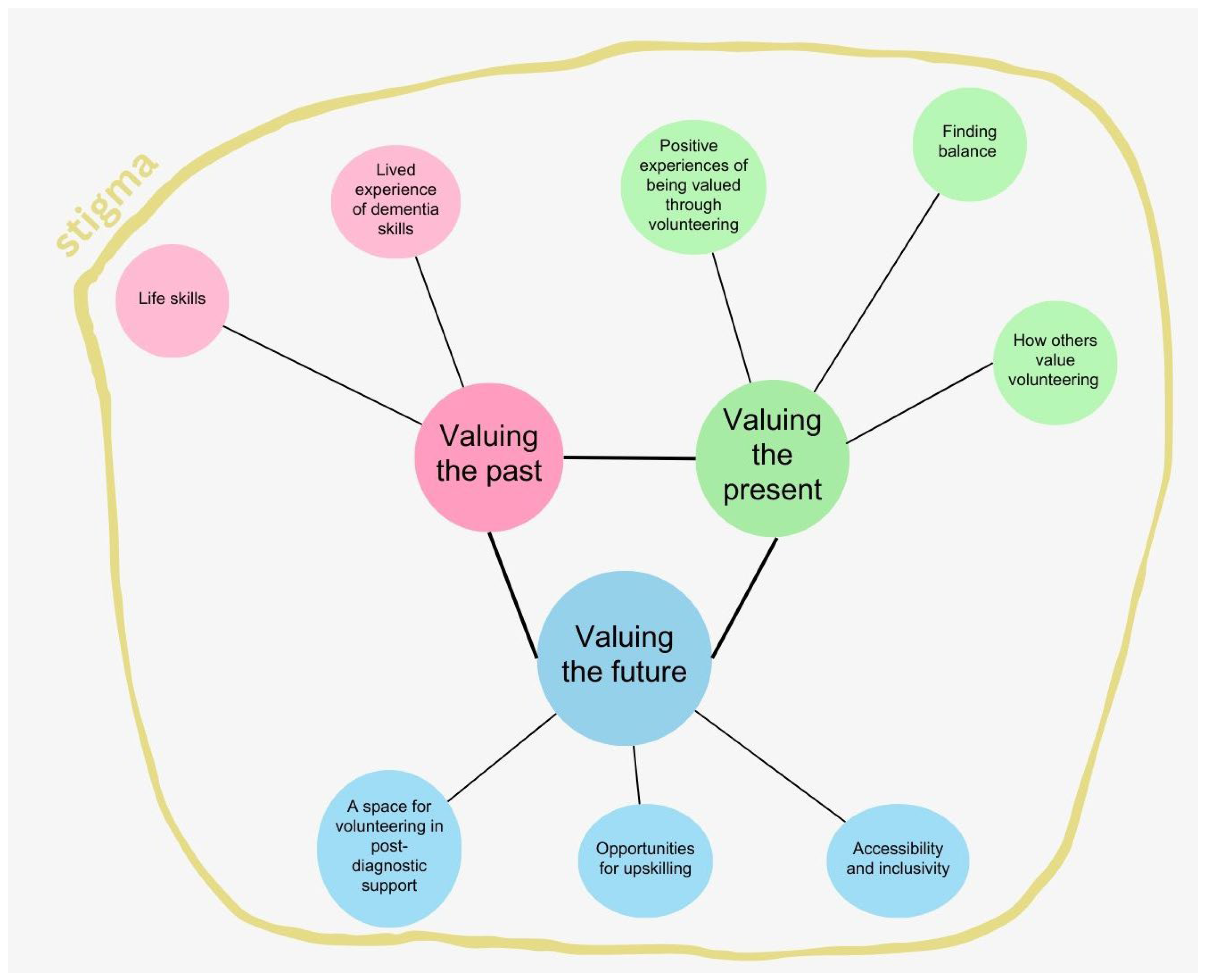

Figure 1.

Thematic map of themes and subthemes.

Figure 1.

Thematic map of themes and subthemes.

Stigma was found to be the overarching concept (or net) which influenced people’s experiences of volunteering with dementia. We found that dementia stigma is powerful, pervasive, and imbues many aspects of people’s lives with dementia. Throughout our analytic discussions, references to stigma were frequent. For this reason, it felt incorrect to attach stigma to one specific theme or themes, as it is relevant to them all. We chose to position stigma as a net, a net that covers and captures all our themes and findings, and a net from which we are trying to escape.

Often people with young onset dementia state that stigma is different for them. As mentioned in the introduction, an example of the influence of stigma on the lives of people with dementia is the way people are told they do not look like they have dementia. Trying to navigate the impact of getting a diagnosis alongside peoples preconceived ideas about what dementia should look like can be exhausting. There is a sense that getting dementia when you are older is more expected and acceptable.

Our three themes are unified around the concept of valuing a person with dementia as a way to challenge stigma and cast the net aside. The themes form a lifespan approach that we hope will support the involvement of people with dementia in volunteering. They are: 1) Valuing the past, which encompasses the subthemes of, ‘life skills’ and ‘lived experience of dementia skills’, 2) Valuing the present, which encompasses the subthemes of ‘positive experiences of being valued through volunteering’, ‘finding balance’, and ‘how others value volunteering’, and 3) Valuing the future, which encompasses the subthemes of, ‘a space for volunteering in post-diagnostic support’, ‘opportunities for upskilling through volunteering’, and ‘accessibility and inclusivity’.

3.1. Identified Themes

Despite the overarching net of stigma and its significant consequences on people’s lives, our findings demonstrate the variety of ways people with dementia do volunteer, the strengths and value they bring to their volunteering and the impact it has on the world. These findings all cluster together around the central and unifying concept of valuing people.

Value relates to the importance and worth that is held for someone or something. The valuing of people with dementia, as previously discussed, has the tendency to be limited. However, valuing people with dementia and their potential, was the hopeful message that was generated through our analysis. To value people with dementia is an active process and means resisting commonly held discriminatory and stigmatic beliefs. We have separated the valuing of a person into three themes which encompass their past, their present and their future.

3.1.1. Theme 1—Valuing the Past

This theme was focussed on valuing the history of a volunteer with dementia, which involves an awareness of the skills they have from their past experiences, hobbies and work that could be of use to volunteering roles. There are two subthemes: ‘life skills’ and ‘lived experience of dementia skills’.

3.1.1.1. Subtheme—Life Skills

3.1.1.2. Subtheme—Lived Experience of Dementia Skills

And others who were doing ‘lived experience of dementia skills’ volunteering:

In some instances, the volunteering combined both sets of skills:

Being an amateur musician, I approached our group to sing some background vocals when we recorded the song, which they did, and they were all fantastic. Everybody seemed to like it. We decided to put it onto YouTube and sell the CD which has 2 songs on it off the strength of that one which is what we did. We raised over 1,100 pounds now towards the Alzheimer’s research. Our target is 2,000 pounds (Paul, taken from

https://dementiadiaries.org/entry/970/since-i-got-diagnosed-i-feel-more-on-the-edge-to-write-music)

However, what became clear was that the opportunities to volunteer in the ‘lived experience of dementia skills’ field, far outweighed ‘life skills’ volunteering opportunities.

The co-researchers, offering their lived experience insight into the research, feel it is important to acknowledge that there is a sense that those of us living with dementia are often assumed to be only able to do dementia related volunteering now and our previous career or life skills are not always valued. For example, one of us commented “Made me realise that everyone I know, we only give talks about dementia, we don’t give talks about our past work much, which is very disheartening.”

3.1.2. Theme 2—Valuing the Present

This theme is focussed on valuing a volunteer with dementia in the ‘now’. This focus on the present is about the different aspects of the day-to-day of being a volunteer with dementia, which involves an awareness of how beneficial volunteering can be, how volunteers can sometimes take too much on or be seen to take too much on, and what happens when the people value volunteers with dementia and the ways that can be actioned. There are three subthemes: ‘Positive experiences of being valued through volunteering’, ‘finding balance’ and ‘how others value volunteering’.

3.1.2.1. Subtheme—Positive Experiences of Being Valued through Volunteering

There were many benefits associated with volunteering, including how it impacts on dementia symptom progression, such as:

At the end of 2020 I decided to retire. This led me to me leaving most of my clients and freeing up my time. I became involved with the administration part of Dementia Matters, and became the person responsible for recording attendance, adding information to a database (…) in doing all this I have stabilised myself so that I am hopefully not sliding further into my dementia, I don’t think. It keeps my mind active and helps me build friendships around the world. This is basically how I am able to survive, being locked out in these uneasy times” (Bill, taken from

https://dementiadiaries.org/entry/17279/bill-talks-about-how-finding-others-with-dementia-online-has-helped-him-during-lockdown)

As one co-researcher shared “My neurologist has said that I would have been in care three years ago without the research that I do.”

A sense of purpose and meaning was another benefit:

I volunteered to be a paper picker around the area that I live in, which is on The Spinney in Goldington. I pick up paper daily just about, bags, bags, bags. I walk across to Tesco; absolutely dreadful and I know it’s probably people just dropping paper, the wind blows it into the trees and all that sort of thing” (Phillip, taken from https://dementiadiaries.org/entry/983/i-volunteered-to-be-a-paper-picker)

3.1.2.2. Subtheme—Finding Balance

Our next subtheme on valuing a volunteer in the present, is having an awareness of the importance of finding balance, such as:

It was quite busy – maybe too busy, but anyways, because I was exhausted by the weekend… I did advanced dementia training in Dartford, as part of the KMPT trust I do volunteer work as an envoy, dementia envoy. And they asked me as part of that role to help the training, from the retired nurse point of view and because I have dementia and… But it was really good” (Tracey, taken from

https://dementiadiaries.org/entry/12802/tracey-has-had-a-really-busy-week-including-being-on-tv)

The previous extract demonstrates the balancing act of being over tired but being energised by volunteering. However, the following extract highlights the effort it can take for people with dementia to take part in voluntary activities:

Often people look from the outside and wonder how we who are in the early to mid-stages could possibly have dementia yet appear to be functioning well. The answer? The duck analogy and peer support. The duck analogy refers to the fact that while we appear to be doing well, like a duck gliding across a pond, in reality the air of normality usually masks a hell of a lot of hard work behind the scenes or like the duck, paddling like fury to stay afloat” (Julie, taken from

https://dementiadiaries.org/entry/11238/compare-dementia-to-the-duck-analogy-of-paddling-frantically-below-the-water)

The diary extract demonstrates how tiredness can affect people and how much hard work doing what a “simple task” can be.

3.1.2.3. Subtheme—How Others Value Volunteering

We, the researchers, volunteer our time and knowledge to campaign and raise awareness about dementia. As one researcher commented, “I am not retired, I didn’t choose to give up work and I am not unemployed, I am working really hard”. Currently, there is little recognition of volunteers with dementia and what they do, which contributes to the lack of value attributed to the role.

However, the issue with volunteering and dementia is the assumption that people with dementia cannot volunteer. As illustrated by the following diary extract:

Therefore, volunteer recruiters should take an interest in the person behind the diagnosis. The positive impact of being valued for what you can bring to your volunteering is demonstrated here:

Providing feedback was also highlighted as a crucial element to demonstrating the value held for a volunteer with dementia:

Value also related to the relationship between volunteers, as demonstrated here how important teamwork was to doing volunteering:

Yesterday I went to a meeting, here on Sheerness, and we had a project, we are starting to make the banner for the dementia walk in September and between us we sat down and we planned, we found out what we wanted to put on the banner, you know, and we’ll work together. And at the end of it we come up with a really good banner for us to carry when we go onto the walk, but it’s great to think that actually people are saying that we can’t do anything, that we have no capabilities to advise but we’ve proved them wrong (Keith, taken from

https://dementiadiaries.org/entry/12241/i-have-dementia-dementia-doesnt-have-me-says-keith)

As was peer-support:

When I was in paid work I managed complex cases as a Social Worker in a paperless office, so I needed proficiency in computers. Last week I was putting the finishing touches to the YODA newsletter, saving the document on my laptop. When I tried to publish this on the Facebook page and beyond I couldn’t work out how to transfer the file. At last I turned to my friend and fellow diarist, Howard Gordon who attached it to his blog and shared it for me. The beauty of teamwork! (Julie, taken from

https://dementiadiaries.org/entry/11238/compare-dementia-to-the-duck-analogy-of-paddling-frantically-below-the-water)

3.1.3. Theme 3—Valuing the Future

The final theme is focussed on thinking about the future for volunteers with dementia. This involves a consideration of what could be possible for people post-diagnosis, the steps to be taken and the barriers that need to be tackled to create opportunities for volunteers with dementia. There are three subthemes: ‘a space for volunteering in post-diagnostic support’, ‘opportunities for upskilling’ and ‘accessibility and inclusivity’.

3.1.3.1. Subtheme—A Space for Volunteering in Post-Diagnostic Support

The first subtheme poses the idea of including volunteering as a topic for consideration in post-diagnostic support. As shown in the following extract, a positive message about life post-diagnosis is important for people with dementia to hear:

And:

3.1.3.2. Subtheme—Opportunities for Upskilling through Volunteering

The second subtheme highlights the different ways volunteering could create opportunities for upskilling for people with dementia. For example, this diarist took on administrative duties and developed their skills in online networking:

also, public speaking:

I helped with some training, I did advanced dementia training in Dartford, as part of the KMPT trust I do volunteer work as an envoy, dementia envoy. And they asked me as part of that role to help the training, from the retired nurse point of view and because I have dementia and… But it was really good. I was a bit nervous, I always get a bit nervous talking to health professionals. But that went down really well (Tracey, taken from

https://dementiadiaries.org/entry/12802/tracey-has-had-a-really-busy-week-including-being-on-tv)

And developed an understanding of bureaucratic processes:

As a co-researcher noted about their volunteering “being involved with national NHS has made me understand where the power really is”

These diary extracts demonstrate how the diarists developed certain skills through their volunteering, that were beneficial both to their volunteering and their personal lives.

3.1.3.3. Subtheme—Accessibility and Inclusivity

This final subtheme focusses on how to make volunteering for people with dementia accessible and inclusive. Taking place during the Covid-19 pandemic our research was obviously influenced by the move to online working and we had many discussions around a future hybrid approach to volunteering. Many people felt isolated during lockdown, but interconnection through volunteering is a way of reducing that isolation, as we can see here:

Many people with dementia may be unable to travel for volunteering opportunities for a variety of reasons. Therefore, creating online volunteering roles and hybrid volunteering opportunities is an important next step for volunteering and dementia. As one co-researcher said:

Whether it’s research or a meeting or anything if it’s live then it needs to be zoomed so that other people can tap in and benefit from it.Even when it’s online, what we have all demonstrated over lockdown is the fact that online volunteer work can be valid and essential.

As was confirmed by another co-researcher “I believe I would not have been able to take part in any meaningful research without the explosion of Teams and Zoom during covid as I live in an isolated location and cannot travel.”

Another aspect related to access and inclusivity is a consideration of how volunteering costs could be a barrier. As you can see in the following diary extract:

I was asked by the universities to come several times, to help them out, which I did. Now, I would get my income, which was my pension, and which tax had been deducted. So, putting my cash in my pocket, I’d go out and get a bus to town, and get a train, and get a taxi at the other end, and repeat the journey. But when I got the money, the money was taxed. So I protested violently. But I never got a penny for doing this, it was all voluntary. And, they’re taxing money that’s already been taxed and it’s come out my pocket. So, aye. I kept complaining, but they kept taxing money that I’d paid out for a bus, train and taxi (James, taken from

https://dementiadiaries.org/entry/17891/james-reflects-on-some-of-the-issues-involved-in-paying-people-with-dementia-for-their-involvement)

As one researcher commented “I know of people living with dementia who volunteer, and they are living on the breadline. Not everyone gets benefits with dementia. Wouldn’t think that many folks would even think this may be the case.” This diary was recorded in 2021, but the diarist is referring to a time in 2000s. The co-researchers felt it was important to clarify that while similar issues do still exist, that some work arounds have been found. If volunteering is to be a credible option for people with dementia, then upfront costs need to be eradicated.

Finally, whether paid or unpaid, employee or volunteer, a person with dementia should be valued for the contribution they have to offer. As summarised in this diary extract:

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

As expected, and in line with the literature, there were clear benefits to volunteering for people with young onset dementia. The key benefits were a sense of purpose and meaning [

27,

28,

29,

30] and developing social connections [

27,

29,

30]. Our study also identified how people with dementia self-report that volunteering slows down their symptom progression. Given these significant benefits to a person’s wellbeing, it seems important for the role of volunteering to be given due consideration as an option for people in post-diagnostic support conversations. Volunteering could help to keep people active for longer, enabling them to stay at home, while also creating opportunities for carer respite, which would be beneficial for those with families living at home [

27,

41]. Currently, post-diagnostic support is variable and often does not give appropriate attention to living a good life post diagnosis. Diagnosis can be a very negative experience for people [

42] and often people are ‘prescribed disengagement’ at this stage [

25]. We argue that introducing the option of volunteering post-diagnosis could create more moments for hope. However, if volunteering is discussed in post-diagnostic conversations, there needs to be a time-sensitive awareness. For example, on the day of diagnosis may be inappropriate as someone is having to take in a huge life change and a lot of information that may be overwhelming. Whereas a few months later they may be more adjusted to the diagnosis and ready to pursue new activities.

Conversely, this finding must be taken into consideration with an awareness of the paucity of volunteering opportunities for people living with dementia in the UK. For professionals to be able to propose volunteering as a post-diagnostic suggestion, there would need a progression in our understanding of volunteering for people with dementia and a development of volunteering schemes and support for people with dementia. If the infrastructure and opportunities for volunteering are not available, then discussing volunteering post-diagnosis could be a fruitless endeavour.

Our study generated several important factors that will be crucial to the development of accessible and meaningful volunteer opportunities for people with young onset dementia. Firstly, we identified the importance of finding balance with volunteering pursuits, which is not something considered by the research that explicitly explores volunteering and dementia [

27,

28,

29]. This finding is especially pertinent to volunteers of an activist orientation, as considerable work needs to be done in addressing dementia stigma and volunteers are liable to take on too much in their pursuit to improve things for people who come after them [

43]. Volunteer activists are having to navigate their dementia symptoms alongside their voluntary campaigning and will need to ensure they strike an appropriate balance for them and create spaces for rest and recovery [

43,

44]. Often people with young onset dementia are not believed about their diagnosis or that they are struggling due to the outward presentation of them looking “normal”, which is demonstrative of how stigma can impact on how people think dementia should look [

6]. This is something volunteer coordinators would need to be conscious of and sensitive to when supporting volunteers with dementia, especially if they are volunteering in the community and could be exposed to such behaviours. On the other hand, some forms of dementia can have more visible symptoms that could be mis-interpreted. For example, one co-researcher was continually accused of being drunk because of the way their dementia impacted on their movement.

Other important skills for a dementia specific volunteer coordinator includes the giving of feedback. People do not want uncritical praise, they don’t want to be infantilised, they want someone to tell them what they are doing well and what needs work. They also need to create opportunities for peer support amongst volunteers with dementia. As with our study, previous literature suggests that dedicated time for socialising and discussing progress with peers is an important component of the success of a volunteer project [

27,

29]. Furthermore, volunteer coordinators should take an interest in the person and their individual interests [

32] and be sensitive, responsive, and flexible to fluctuating needs [

41]. They should be conscious that if opportunities to volunteer are initially offered, but then discontinued it could have an impact on a person’s self-esteem. Finally, they should create opportunities for upskilling through the volunteering work [

27,

29].

From an organisational perspective, places that want to offer volunteering opportunities to people with dementia should consider if they can create hybrid options. People with dementia may be isolated locationally, or they may be unable to travel and therefore opportunities need to be accessible online and in their local community. We propose that volunteering for people with dementia should be embedded in the community, such as in the DemenTalent program [

31]. This is crucial given how distributed people with young onset dementia are across the UK and that specialist service hubs may not be accessible to everyone. Furthermore, online volunteering is a growing area since the Covid-19 pandemic and could be a viable option for many people with younger onset dementia who are technologically competent. Finally, cost must be an essential consideration, organisations need to ensure there are no upfront costs to volunteering, and if there are, that payment is made in advance or on the day rather than people having to claim back for them.

4.2. Limitations

A limitation of this study could be the use of secondary data taken from the Dementia Diaries. Due to the activist leaning of many of the contributors, it could be argued this data is not necessarily representative of all people with young onset dementia in the UK. However, the Dementia Diaries enabled us to access the experiences of many people living with young onset dementia in the UK. Furthermore, this research occurred during the Covid-19 pandemic when all face-to-face research methods were prohibited. Using the Dementia Diaries allowed us to conserve data and avoid placing too much pressure on people with dementia to contribute to research at a time they likely had other more significant issues on their minds. Finally, the audio data was uniquely beneficial to participatory research with people with dementia as they were able to listen to the data as they read along, which the team agreed enhanced their engagement with the diaries.

Secondly, a lack of diversity amongst the co-production group and the Dementia Diarists is an important consideration. The Smarties come from across the UK, with an even spilt of males and females. However, we were also a group of white people, and the co-researchers living with dementia were in the mild to moderate stages. As Warran et al. [

45] discuss, there are significant issues around getting diverse groups together to do co-produced dementia research. The decisions made on who to include in this project came from the position of who came forward to be involved as time was limited. However, spending more time and energy actively seeking out a more representative group would have been a more appropriate choice. Furthermore, the Dementia Diarists are primarily white. In an attempt to address the lack of representation we automatically included any diaries from diarists from the Global Majority to ensure their voices were included in the analysis. Finally, while we are conscious of the importance of developing ways to include people with advanced dementia in research, the online nature of this project meant the co-researchers had to be able to use the online video conferencing software Zoom to take part. This inclusion criteria meant that those with more advanced dementia would have been unable to take an active part in the work.

4.3. Recommendations

Future research in this area would benefit from engaging a larger sample of people, potentially reaching out to a broader group of people with different volunteering experiences and a more representative sample. For example, in the ‘Time Well Spent 2023: Volunteering among the global majority’ report [

46], Global Majority volunteers were reported to be younger, more likely to be in employment, more religious and live in more urban areas in comparison with volunteers overall. The report found religion to be an important factor when considering volunteering. For many religious groups volunteering is an essential component to their faith and way of life [

47]. Therefore, an exploration of the cultural and spiritual differences of volunteering could be an important aspect to consider when attempting to understand the volunteering and dementia field.

Furthermore, if volunteering options are to become more widely available it will require a concerted outlook shift. Volunteering opportunities will need to be embedded in the community, in a variety of organisations and outside of the dementia field. This will involve the development of third-sector guides and a specific training program for organisations seeking to recruit volunteers with dementia, to ensure they have the appropriate skills and understanding of dementia (i.e., an awareness of stigma and recognition of the rights and capabilities of people with dementia) to deliver empowering opportunities for people to flourish.

Finally, one thing that came across frequently in the co-researcher’s discussions about the lack of appropriate services was how peer support networks had developed to fill the gap left by traditional services and the importance of a virtual community that sprung up post the Covid-19 pandemic. One example of this is the development of meeting centres across the UK to create community based, safe spaces for people with dementia to come together whatever their age and stage. While meeting centres in the Netherlands have been explored in the previous literature [

30,

32], research into the volunteering done by people with dementia in UK based meetings centres will be an important next step. Additionally, voluntarily developed peer-to-peer resources, such as the education work done by the lived experience group STAND [48] would benefit from future consideration.

5. Conclusions

Volunteering could be a viable option for people with young onset dementia to engage in stage and age-appropriate, locally based and personally meaningful activity. For this to happen will require a shift in people’s perceptions about what people with dementia can do and to resist commonly held stigmatic views about dementia. This research proposes this can be done through the valuing of people with dementia, with consideration of their past, the present and their future. The findings reported in this paper that aim to inform and support the recruitment and involvement of people with young onset dementia as volunteers will be developed into an accessible guide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.E.V, R.A, I.D, J.H, G.K, C.M, K.O. M.R, T.C.R. and H.W.; methodology, R.E.V, R.A, I.D, J.H, G.K, C.M, K.O. M.R, T.C.R. and H.W.; formal analysis, R.E.V, R.A, I.D, J.H, G.K, C.M, K.O. and M.R.; investigation, R.E.V, R.A, I.D, J.H, G.K, C.M, K.O. and M.R.; resources, R.E.V. and R.A.; data curation, R.E.V. and R.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.E.V; writing—review and editing, R.E.V, R.A, I.D, J.H, G.K, C.M, K.O, M.R., T.C.R and H.W.; supervision, T.C.R and H.W.; project administration, R.E.V, T.C.R. and H.W.; funding acquisition, R.E.V, T.C.R and H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Alzheimer’s Society, grant number 515.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was granted by the University of Edinburgh School of Health in Social Science Ethics Committee (HiSS30/03/21)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was not required from the participants of the Dementia Diaries project because the data used is in the public domain and freely available online.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all the diarists who contribute to the Dementia Diaries. This work would not have been possible without you.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Young Dementia Network: About young onset dementia. Available online: https://www.youngdementianetwork.org/about-young-onset-dementia/ (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Hayo, H.; Ward, A.; Parkes, J. Young onset dementia: A guide to recognition, diagnosis, and supporting individuals with dementia and their families; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2018.

- Mayrhofer, A.M.; Greenwood, N.; Smeeton, N.; Almack, K.; Buckingham, L.; Shora, S.; Goodman, C. Understanding the financial impact of a diagnosis of young onset dementia on individuals and families in the United Kingdom: Results of an online survey. Health Soc Care Community 2021, 29, pp. 664-671. [CrossRef]

- Loi, S.M.; Goh, A.M.Y.; Mocellin, R.; Malpas, C.B.; Parker, S.; Eratne, D.; Farrand, S.; Kelso, W.; Evans, A.; Walterfang, M.; Velakoulis, D. Time to diagnosis in younger-onset dementia and the impact of a specialist diagnostic service. Int Psychogeriatr 2022, 34, pp. 367-375. [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, N.; Smith, R. The experiences of people with young-onset dementia: A meta-ethnographic review of the qualitative literature. Maturitas 2016, 92, pp. 102-109. [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, R.; Fyvel, S.; Hill, A.; Maddocks, C.; Qureshi, M.; Ross, D.; Hay, S.; Robertson, M.; Gilder, W.; Henry, W.; Lamont, M.; Houston, A.; Wilson, F.S. Challenging Assumptions Around Dementia; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mayrhofer, A.; Mathie, E.; McKeown, J.; Bunn, F.; Goodman, C. Age-appropriate services for people diagnosed with young onset dementia (YOD): a systematic review. Aging & Mental Health 2018, 22, pp. 933-941. [CrossRef]

- Mayrhofer, A.; Mathie, E.; McKeown, J.; Goodman, C.; Irvine, L.; Hall, N.; Walker, M. Young onset dementia: Public involvement in co-designing community-based support. Dementia 2020, 19, pp. 1051–1066. [CrossRef]

- Giebel, C.; Eastham, C.; Cannon, J.; Wilson, J.; Wilson, J.; Pearson, A. Evaluating a young-onset dementia service from two sides of the coin: Staff and service user perspectives. BMC Health Serv Res 2020, 20, pp. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Stamou, V.; La Fontaine, J.; Gage, H.; Jones, B.; Williams, P.; O’Malley, M.; Parkes, J.; Carter, J.; Oyebode, J. Services for people with young onset dementia: The ‘Angela’ project national UK survey of service use and satisfaction. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2021, 36, pp. 411-422. [CrossRef]

- Giebel, C.; Hanna, K.; Tetlow, H.; Ward, K.; Shenton, J.; Cannon, J.; Butchard, S.; Komuravelli, A.; Gaughan, A.; Eley, R.; Rogers, C.; Rajagopal, M.; Limbert, S.; Callaghan, S.; Whittington, R.; Shaw, L.; Gabbay, M. “A piece of paper is not the same as having someone to talk to”: accessing post-diagnostic dementia care before and since COVID-19 and associated inequalities. Int J Equity Health 2021, 20, pp. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Nichol, B.; Wilson, R.; Rodrigues, A.; Haighton, C. Exploring the Effects of Volunteering on the Social, Mental, and Physical Health and Well-being of Volunteers: An Umbrella Review. Voluntas 2024, 35, pp. 97-128. [CrossRef]

- Cattan, M.; Hogg, E.; Hardill, I. Improving quality of life in ageing populations: What can volunteering do? Maturitas 2011, 70, pp 328-322. [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, C.E.; Dickens, A.P.; Jones, K.; Thompson-Coon, J.; Taylor, R.S.; Rogers, M.; Bambra, C.L.; Lang, I.; Richards, S.H. Is volunteering a public health intervention? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the health and survival of volunteers. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, pp. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, R., O’Connor, D. Broadening the dementia debate: Towards social citizenship; The Policy Press: Portland, USA, 2010.

- Institute for volunteering research: What is volunteering? Available online: https://www.uea.ac.uk/groups-and-centres/institute-for-volunteering-research (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Alzheimer’s Society: 3 Nations Working Group. Available online: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/get-involved/engagement-participation/three-nations-dementia-working-group (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Alzheimer Scotland: Scottish Dementia Working Group. Available online: https://www.alzscot.org/our-work/campaigning-for-change/have-your-say/scottish-dementia-working-group (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Dementia Voices: Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project. Available online: https://www.dementiavoices.org.uk/ (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Lukka, P.; Ellis Paine, A. An exclusive construct exploring different cultural concepts of volunteering. Voluntary Action 2001, 3, pp. 87–109.

- Southby, K.; South, J. Volunteering, Inequalities and Public Health: Barriers to Volunteering - summary report. Volunteering matters, London, 2016. Available online: https://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/id/eprint/3435/1/Barriers%20to%20Volunteering_summary.pdf (accessed 18 April 2024).

- Shakespeare, T.; Zeilig, H.; Mittler, P. Rights in Mind: Thinking Differently About Dementia and Disability. Dementia 2019, 18, pp. 1075–1088. [CrossRef]

- Southby, K.; South, J.; Bagnall, A.M. A Rapid Review of Barriers to Volunteering for Potentially Disadvantaged Groups and Implications for Health Inequalities. Voluntas 2019, 30, pp. 907–920. [CrossRef]

- Swaffer, K. Dementia and prescribed disengagementTM. Dementia 2015, 14, pp. 3-6. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.; Pedley, G.; Pelone, F.; Akhtar, F.; Chang, J.; Muleya, W.; Greenwood, N. Psychosocial interventions for people with young onset dementia and their carers: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics 2016, 28, pp. 1441-1454. [CrossRef]

- Kinney, J.M.; Kart, C.S.; Reddecliff, L. ‘That’s me, the Goother’: Evaluation of a program for individuals with early-onset dementia. Dementia 2011, 10, pp. 361–377. [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, P.; Watts, C.; Hussey, J.; Power, K.; Williams, T. Does a Structured Gardening Programme Improve Well-Being in Young-Onset Dementia? A Preliminary Study. Br J Occup Ther 2013, 76, pp. 355–361. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.; Evans, D. Evaluation of a workplace engagement project for people with younger onset dementia. J Clin Nurs 2015, 24, pp. 2331–2339. [CrossRef]

- Söderlund, M.; Hellström, I.; Vamstad, J.; Hedman, R. Peer support for the newly diagnosed: How people with dementia can co-produce meeting centre services. Ageing Soc 2022, 44, pp. 180-199. [CrossRef]

- DemenTalent: About DemenTalent. Available online: https://dementalent.nl/over-dementalent (accessed on 28 April 2024).

- Dröes, R.M.; van Rijn, A.; Rus, E.; Dacier, S.; Meiland, F. Utilization, effect, and benefit of the individualized meeting centers support program for people with dementia and caregivers. Clin Interv Aging 2019, 14, pp. 1527-1553. [CrossRef]

- Van Rijn, A.; Meiland, F.; Droës, R.M. Linking DemenTalent to Meeting Centers for people with dementia and their caregivers: a process analysis into facilitators and barriers in 12 Dutch Meeting Centers. Int Psychogeriatr 2019, 31, pp. 1433–1445. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health Welfare and Sport: National Dementia Strategy 2021-2030. Available online: https://www.government.nl/documents/publications/2020/11/30/national-dementia-strategy-2021-2030 (accessed 28 April 2024).

- Litherland, R.; Hare, P. People with dementia at the heart of research; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2024.

- Farr, M.; Davies, P.; Andrews, H.; Bagnall, D.; Brangan, E.; Davies, R. Co-producing knowledge in health and social care research: reflections on the challenges and ways to enable more equal relationships. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 2021, 8, pp. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- The University of Edinburgh: The Smarties. Available online: https://www.ed.ac.uk/health/research/current-research/smarties (accessed 18 April 2024).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health 2019, 11, pp. 589–597. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2013.

- Gastaldo, D.; Magalhães, L.; Carrasco, C.; Davy, C. Body-Map Storytelling as Research: Methodological considerations for telling the stories of undocumented workers through body mapping. Available online: https://www.migrationhealth.ca/undocumented-workers-ontario/body-mapping (accessed 28 April 2024).

- Roach, P.; Drummond, N. ‘It’s nice to have something to do’: Early-onset dementia and maintaining purposeful activity. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2014, 21, pp. 889-895. [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, M.; Carter, J.; Stamou, V.; LaFontaine, J.; Oyebode, J.; Parkes, J. Receiving a diagnosis of young onset dementia: a scoping review of lived experiences. Aging Ment Health 2021, 25, pp. 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Seetharaman, K.; Chaudhury, H. ‘I am making a difference’: Understanding advocacy as a citizenship practice among persons living with dementia. J Aging Stud 2020, 52, pp. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, R. Citizenship in action: the lived experiences of citizens with dementia who campaign for social change. Disabil Soc 2014, 29, pp. 1291- 1304. [CrossRef]

- Warran, K.; Greenwood, F.; Ashworth, R.; Robertson, M.; Brown, P. Challenges in co-produced dementia research: A critical perspective and discussion to inform future directions. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2023, 38, pp. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Kanemura, R.; McGarvey, A.; Farrow, A. Time Well Spent 2023: A national survey on the volunteer experience. Available online: https://www.ncvo.org.uk/news-and-insights/news-index/time-well-spent-2023/#/ (accessed 28 April 2024).

- Hylton, K.; Lawton, R.; Watt, W.; Wright, H.; Williams, K. Review of Literature, in The ABC of BAME New, mixed method research into black, Asian and minority ethnic groups and their motivations and barriers to volunteering. Available online: https://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/id/eprint/5601/1/The-ABC-of-BAME-Jump-Report-10.01.18-1.pdf (accessed 28 April 2024).

- Age Scotland: Peer-to-Peer Resources. Available online: https://www.agescotland.org.uk/our-impact/about-dementia/publications-and-resources/resources-from-the-life-changes-trust/peer-to-peer-resources (accessed 28 April 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).