Submitted:

30 April 2024

Posted:

02 May 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

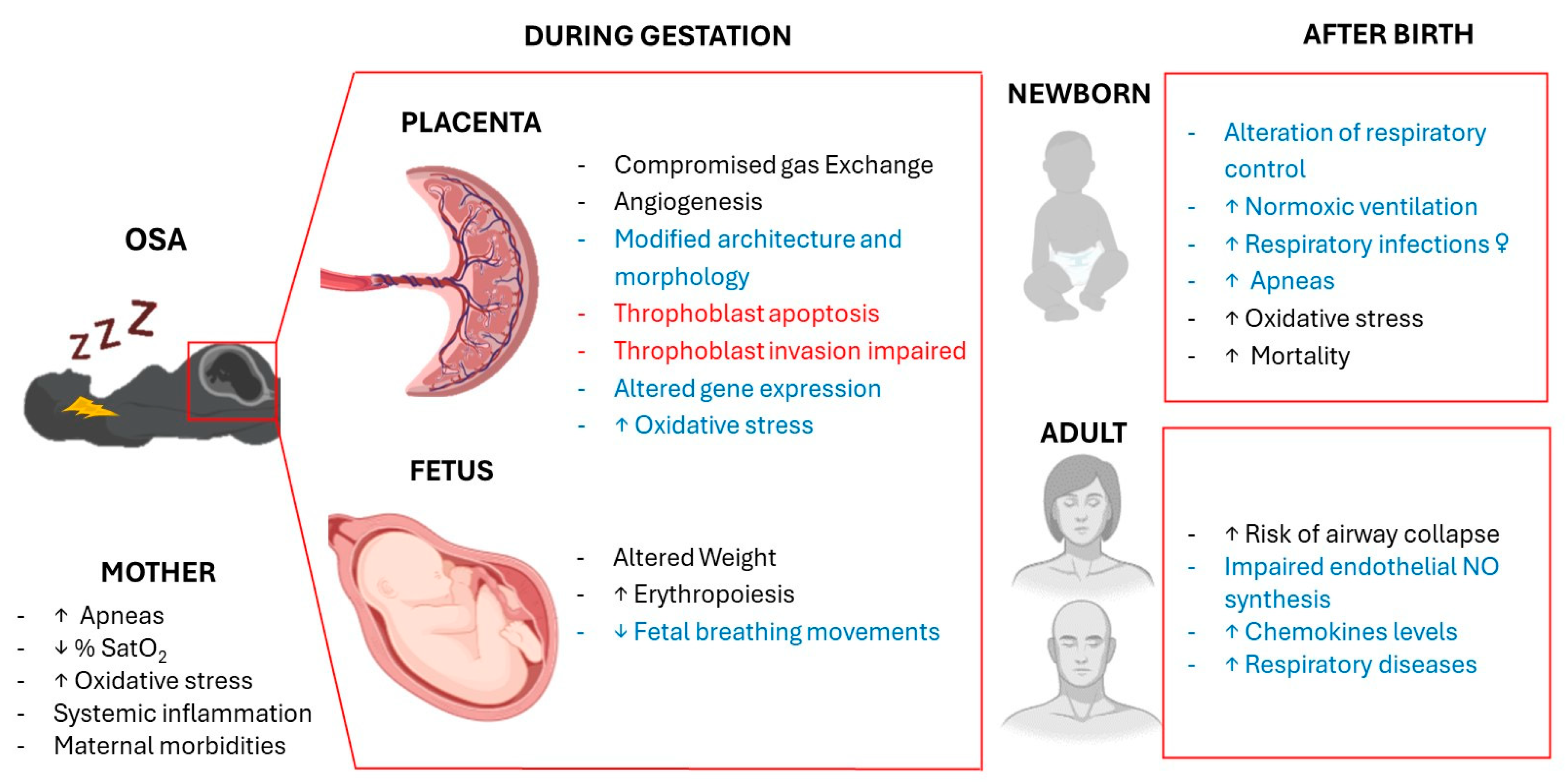

1. Introduction

2. Maternal Respiratory Disturbances

2.1. Hormonal changes

2.2. Anatomical changes

2.3. Respiratory changes during labour and delivery

3. Effects of Intermittent Hypoxia in the Placenta

4. Fetal Respiratory Distress

5. Offspring Respiratory Disorders

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Canever JB, Zurman G, Vogel F, Sutil DV, Diz JBM, Danielewicz AL, Moreira BS, Cimarosti HI, de Avelar NCP. Worldwide prevalence of sleep problems in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2024, 119, 118–134. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinzer R, Vat S, Marques-Vidal P, Marti-Soler H, Andries D, Tobback N, Mooser V, Preisig M, Malhotra A, Waeber G, Vollenweider P, Tafti M, Haba-Rubio J. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in the general population: The HypnoLaus study. Lancet Respir Med. 2015, 3, 310–318. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mediano O, González Mangado N, Montserrat JM, Alonso-Álvarez ML, Almendros I, Alonso-Fernández A, et al. Documento internacional de consenso sobre apnea obstructiva del sueno. Arch Bronconeumol. 2022, 58, 52–68. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary B, Dasti S, Park Y, Brown T, Davis H, Akhtar B. Hour-to-hour variability of oxygen saturation in sleep apnea. Chest 1998, 113, 719–722. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez C, Almaraz L, Obeso A, Rigual R. Carotid body chemoreceptors: From natural stimuli to sensory discharges. Physiol Rev. 1994, 74, 829–898. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, R.; Baker, T.L.; Watters, J.J.; Kumar, S. Obstructive Sleep Apnea-Associated Intermittent Hypoxia-Induced Immune Responses in Males, Pregnancies, and Offspring. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhakar NR, Peng YJ, Nanduri J. Carotid body hypersensitivity in intermittent hypoxia and obtructive sleep apnoea. J Physiol. 2023, 601, 5481–5494. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, T. Rationale, design and findings from the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study: Toward understanding the total societal burden of sleep disordered breathing. Sleep Med Clin. 2009, 4, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pien, G.W.; Pack, A.I.; Jackson, N.; Maislin, G.; Macones, G.A.; Schwab, R.J. Risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing in pregnancy. Thorax 2014, 69, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu B, Bronas UG, Carley DW, Lee K, Steffen A, Kapella MC, Izci-Balserak B. Relationships between objective sleep parameters and inflammatory biomarkers in pregnancy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2020, 1473, 62–73. [CrossRef]

- Louis JM, Koch MA, Reddy UM, Silver RM, Parker CB, Facco FL, Redline S, Nhan-Chang CL, Chung JH, Pien GW, Basner RC, Grobman WA, Wing DA, Simhan HN, Haas DM, Mercer BM, Parry S, Mobley D, Carper B, Saade GR, Schubert FP, Zee PC. Predictors of sleep-disordered breathing in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018, 218, e1–e521. [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriou D, Athanasiadou KI, Sifnaios E, Vagiakis E, Katsaounou P, Psaltopoulou T, Paschou SA, Trakada G. Sleep disorders during pregnancy: An underestimated risk factor for gestational diabetes mellitus. Endocrine 2024, 83, 41–50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis JM, Mogos MF, Salemi JL, Redline S, Salihu HM. Obstructive sleep apnea and severe maternal-infant morbidity/mortality in the United States, 1998-2009. Sleep 2014, 37, 843–849. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalyfa A, Cortese R, Qiao Z, Ye H, Bao R, Andrade J, Gozal, D. Late gestational intermittent hypoxia induces metabolic and epigenetic changes in male adult offspring mice. J Physiol 2017, 595, 2551–2568. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlgren J, Samuelsson AM, Jansson T, Holmäng A. Interleukin-6 in the maternal circulation reaches the rat fetus in mid-gestation. Pediatr Res. 2006, 60, 47–51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras G, Gutiérrez M, Beroíza T, Fantín A, Oddó H, Villarroel L, Cruz E, Lisboa C. Ventilatory drive and respiratory muscle function in pregnancy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991, 144, 837–841. [CrossRef]

- Lyons HA, Antonio R. The sensitivity of the respiratory center in pregnancy and after administration of progesterone. Trans Assoc Am Physicians 1959, 72, 173–180.

- Weinberger SE, Weiss ST, Cohen WR, Johnson, TS. Pregnancy and the lung. Am Rev Respir Dis 1980, 121, 559–581. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAuliffe F, Kametas N, Costello J, Rafferty GF, Greenough A, Nicolaides K. Respiratory function in singleton and twin pregnancy. BJOG 2002, 109, 765–769. [CrossRef]

- Izci B, Vennelle M, Liston WA, Dundas KC, Calder AA, Douglas NJ. Sleep-disordered breathing and upper airway size in pregnancy and post-partum. Eur Respir J. 2006, 27, 321–327. [CrossRef]

- Izci B, Riha RL, Martin SE, Vennelle M, Liston WA, Dundas KC, Calder AA, Douglas NJ. The upper airway in pregnancy and pre-eclampsia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003, 167, 137–140. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bende M, Gredmark T. Nasal stuffiness during pregnancy. Laryngoscope 1999, 109, 1108–1110. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams PE, Goldspink G. Changes in sarcomere length and physiological properties in immobilized muscle. J Anat. 1978, 127 Pt 3, 459–468.

- Froeliger A, Deneux-Tharaux C, Madar H, Bouchghoul H, Le Ray C, Sentilhes L. TRAAP study group. Closed- or open-glottis pushing for vaginal delivery: A planned secondary analysis of the TRAnexamic Acid for Preventing postpartum hemorrhage after vaginal delivery study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2024, 230, S879–S889.e4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lui B, Burey L, Ma X, Kjaer K, Abramovitz SE, White RS. Obstructive sleep apnea is associated with adverse maternal outcomes using a United States multistate database cohort, 2007-2014. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2021, 45, 74–82. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltepe E, Fisher SJ. Placenta: The forgotten organ. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2015, 31, 523–552. [CrossRef]

- Zamudio, S. The placenta at high altitude. High Alt. Med. Biol. 2003, 4, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutter, D. , Kingdom, J., Jaeggi, E. Causes and mechanisms of intrauterine hypoxia and its impact on the fetal cardiovascular system: A review. Int. J. Pediatr. 2010, 2010, 401323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sferruzzi-Perri AN, Camm EJ. The Programming Power of the Placenta. Front Physiol. 2016, 7, 33. [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, O.R. , Sferruzzi-Perri, A. N., Coan, P.M., Fowden, A. L. Environmental regulation of placental phenotype: Implications for fetal growth. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2012, 24, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalisch-Smith JI, Simmons DG, Dickinson H, Moritz KM. Review: Sexual dimorphism in the formation, function and adaptation of the placenta. Placenta 2017, 54, 10–16. [CrossRef]

- Hung TH, Burton GJ. Hypoxia and reoxygenation: A possible mechanism for placental oxidative stress in preeclampsia. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2006, 45, 189–200. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso M, Evangelista M, Parolini O. Human term placental cells: Phenotype, properties and new avenues in regenerative medicine. Int J Mol Cell Med. 2012, 1, 64–74.

- Goplerud JM, Delivoria-Papadopoulos M. Physiology of the placenta—Gas exchange. Ann Clin Lab Sci 1985, 15, 270–278.

- Browne VA, Julian CG, Toledo-Jaldin L, Cioffi-Ragan D, Vargas E, Moore LG. Uterine artery blood flow, fetal hypoxia and fetal growth. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2015, 370, 20140068. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravishankar S, Bourjeily G, Lambert-Messerlian G, He M, De Paepe ME, Gündoğan F. Evidence of Placental Hypoxia in Maternal Sleep Disordered Breathing. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2015, 18, 380–386. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Gubory KH, Fowler PA, Garrel C. The roles of cellular reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress and antioxidants in pregnancy outcomes. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010, 42, 1634–1650. [CrossRef]

- Hung TH, Skepper JN, Burton GJ. In vitro ischemia-reperfusion injury in term human placenta as a model for oxidative stress in pathological pregnancies. Am J Pathol. 2001, 159, 1031–1043. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavie, L. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome--an oxidative stress disorder. Sleep Med Rev. 2003, 7, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuffe JS, Walton SL, Singh RR, Spiers JG, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Wilkinson L, Little MH, Moritz KM. Mid- to late term hypoxia in the mouse alters placental morphology, glucocorticoid regulatory pathways and nutrient transporters in a sex-specific manner. J Physiol. 2014, 592, 3127–3141. [CrossRef]

- Higgins JS, Vaughan OR, Fernandez de Liger E, Fowden AL, Sferruzzi-Perri AN. Placental phenotype and resource allocation to fetal growth are modified by the timing and degree of hypoxia during mouse pregnancy. J Physiol. 2016, 594, 1341–1356. [CrossRef]

- Rosario GX, Konno T, Soares MJ. Maternal hypoxia activates endovascular trophoblast cell invasion. Dev Biol. 2008, 314, 362–375. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valverde-Pérez E, Prieto-Lloret J, Gonzalez-Obeso E, Cabero MI, Nieto ML, Pablos MI, Obeso A, Gomez-Niño A, Cárdaba-García RM, Rocher A, Olea E. Effects of Gestational Intermittent Hypoxia on Placental Morphology and Fetal Development in a Murine Model of Sleep Apnea. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2023, 1427, 73–81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakefield SL, Lane M, Mitchell M. Impaired mitochondrial function in the preimplantation embryo perturbs fetal and placental development in the mouse. Biol Reprod. 2011, 84, 572–580. [CrossRef]

- Adelman DM, Gertsenstein M, Nagy A, Simon MC, Maltepe E. Placental cell fates are regulated in vivo by HIF-mediated hypoxia responses. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 3191–3203. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song W, Chang WL, Shan D, Gu Y, Gao L, Liang S, Guo H, Yu J, Liu X. Intermittent Hypoxia Impairs Trophoblast Cell Viability by Triggering the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Pathway. Reprod Sci. 2020, 27, 477–487. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannubilo SR, Cecati M, Marzioni D, Ciavattini A. Circulating miRNAs and Preeclampsia: From Implantation to Epigenetics. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 1418. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myatt L, Webster RP. Vascular biology of preeclampsia. J Thromb Haemost. 2009, 7, 375–384. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton JS, Care AS, Davidge ST. Mechanisms of Uterine Artery Dysfunction in Pregnancy Complications. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2017, 69, 343–359. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang U, Baker RS, Braems G, Zygmunt M, Künzel W, Clark KE. Uterine blood flow--a determinant of fetal growth. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003, 110 Suppl. 1, S55–S61. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds LP, Redmer DA. Utero-placental vascular development and placental function. J Anim Sci 1995, 73, 1839–1851. [CrossRef]

- Genbacev O, Zhou Y, Ludlow JW, Fisher SJ. Regulation of human placental development by oxygen tension. Science 1997, 277, 1669–1672. [CrossRef]

- Jauniaux E, Poston L, Burton GJ. Placental-related diseases of pregnancy: Involvement of oxidative stress and implications in human evolution. Hum Reprod Update 2006, 12, 747–755. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zygmunt M, Herr F, Münstedt K, Lang U, Liang OD. Angiogenesis and vasculogenesis in pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003, 110, S10–S18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med. 2003, 9, 669–676. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishnan S, Anand V, Roy S. Vascular endothelial growth factor signaling in hypoxia and inflammation. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2014, 9, 142–160. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dailey L, Ambrosetti D, Mansukhani A, Basilico C. Mechanisms underlying differential responses to FGF signaling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2005, 16, 233–247. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang K, Jiang YZ, Chen DB, Zheng J. Hypoxia enhances FGF2- and VEGF-stimulated human placental artery endothelial cell proliferation: Roles of MEK1/2/ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT1 pathways. Placenta 2009, 30, 1045–1051. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almendros I, Martínez-Ros P, Farré N, Rubio-Zaragoza M, Torres M, Gutiérrez-Bautista ÁJ, Carrillo-Poveda JM, Sopena-Juncosa JJ, Gozal D, Gonzalez-Bulnes A, Farré R. Placental oxygen transfer reduces hypoxia-reoxygenation swings in fetal blood in a sheep model of gestational sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol 2019, 127, 745–752. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almendros I, Farré R, Planas AM, Torres M, Bonsignore MR, Navajas D, Montserrat JM. Tissue oxygenation in brain, muscle, and fat in a rat model of sleep apnea: Differential effect of obstructive apneas and intermittent hypoxia. Sleep 2011, 34, 1127–1133. [CrossRef]

- Cahill LS, Zhou YQ, Seed M, Macgowan CK, Sled JG. Brain sparing in fetal mice: BOLD MRI and Doppler ultrasound show blood redistribution during hypoxia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2014, 34, 1082–1088. [CrossRef]

- Carter, A.M. Placental gas exchange and the oxygen supply to the fetus. Compr Physiol 2015, 5, 1381–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giussani, D.A. The fetal brain sparing response to hypoxia: Physiological mechanisms. J Physiol 2016, 594, 1215–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal W, Ciriello J. Effect of maternal chronic intermittent hypoxia during gestation on offspring growth in the rat. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2013, 209, 564.e1–564.e9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortese R, Khalyfa A, Bao R, Andrade J, Gozal D. Epigenomic profiling in visceral white adipose tissue of offspring of mice exposed to late gestational sleep fragmentation. Int J Obes 2015, 39, 1135–1142. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortese R, Gileles-Hillel A, Khalyfa A, Almendros I, Akbarpour M, Khalyfa AA, Qiao Z, Garcia T, Andrade J, Gozal D. Aorta macrophage inflammatory and epigenetic changes in a murine model of obstructive sleep apnea: Potential role of CD36. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 43648. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koos, B.J. Breathing and sleep states in the fetus and at birth. In: Marcus CL, Carroll JL, Donnelly DF, Loughlin GM, editors. Sleep and breathing in children: Developmental changes in breathing during sleep. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Informa Healthcare; 2008. p. 1–17.

- Koos BJ, Rajaee A. Fetal breathing movements and changes at birth. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014, 814, 89–101. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick J, Campbell K, Carmichael L, Natale R, Richardson B. A definition of human fetal apnea and the distribution of fetal apneic intervals during the last ten weeks of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980, 136, 471–477. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arduini D, Rizzo G, Giorlandino C, Valensise H, Dell'Acqua S, Romanini C. The development of fetal behavioural states: A longitudinal study. Prenat Diagn. 1986, 6, 117–124. [CrossRef]

- Patrick J, Campbell K, Carmichael L, Natale R, Richardson B. Patterns of human fetal breathing during the last 10 weeks of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1980, 56, 24–30.

- Koos BJ, Matsuda K, Power GG. Fetal breathing and cardiovascular responses to graded methemoglobinemia in sheep. J Appl Physiol 1990, 69, 136–140. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platt LD, Manning FA, Lemay M, Sipos L. Human fetal breathing: Relationship to fetal condition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1978, 132, 514–518. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tauman R, Many A, Deutsch V, Arvas S, Ascher-Landsberg J, Greenfeld M, Sivan Y. Maternal snoring during pregnancy is associated with enhanced fetal erythropoiesis--a preliminary study. Sleep Med. 2011, 12, 518–522. [CrossRef]

- Templeton A, Kelman GR. Maternal blood-gases, (PAo2-Pao2), physiological shunt and VD/VT in normal pregnancy. Br J Anaesth 1976, 48, 1001–1004. [CrossRef]

- Dawes, GS. Foetal and neonatal physiology; a comparative study of the changes at birth. Year Book Medical Publishers, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Longo, L.D. The Rise of Fetal and Neonatal Physiology: Basic Science to Clinical Care, Perspectives in Physiology. Am Physiol Society 2013. [CrossRef]

- Herrington RT, Harned HS Jr, Ferreiro JI, Griffin CA 3rd. The role of the central nervous system in perinatal respiration: Studies of chemoregulatory mechanisms in the term lamb. Pediatrics 1971, 47, 857–864. [CrossRef]

- Chou PJ, Ullrich JR, Ackerman BD. Time of onset of effective ventilation at birth. Biol Neonate. 1974, 24, 74–81. [CrossRef]

- Cohen G, Katz-Salamon M. Development of chemoreceptor responses in infants. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2005, 149, 233–42. [CrossRef]

- Rigatto H, De La Torre Verduzco R, Gates DB. Effects of O2 on the ventilatory response to CO2 in preterm infants. J Appl Physiol. 1975, 39, 896–899. [CrossRef]

- Kumar P, Hanson MA. Re-setting of the hypoxic sensitivity of aortic chemoreceptors in the new-born lamb. J Dev Physiol. 1989, 11, 199–206.

- Richardson HL, Parslow PM, Walker AM, Harding R, Horne RS. Maturation of the initial ventilatory response to hypoxia in sleeping infants. J Sleep Res. 2007, 16, 117–127. [CrossRef]

- Liu Q, Fehring C, Lowry TF, Wong-Riley MT. Postnatal development of metabolic rate during normoxia and acute hypoxia in rats: Implication for a sensitive period. J Appl Physiol 2009, 106, 1212–1222. [CrossRef]

- Trachsel D, Erb TO, Hammer J, von Ungern-Sternberg BS. Developmental respiratory physiology. Paediatr Anaesth. 2022, 32, 108–117. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wani TM, Rafiq M, Akhter N, AlGhamdi FS, Tobias JD. Upper airway in infants-a computed tomography-based analysis. Paediatr Anaesth. 2017, 27, 501–505. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez I, Vega-Briceño L, Muñoz C, Mobarec S, Brockman P, Mesa T, Harris P. Polysomnographic findings in 320 infants evaluated for apneic events. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2006, 41, 215–221. [CrossRef]

- Praud JP, Reix P. Upper airways and neonatal respiration. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2005, 149, 131–141. [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan R, Corwin MJ, Hunt CE, Lister G, Tinsley LR, Baird T, Silvestri JM, Crowell DH, Hufford D, Martin RJ, Neuman MR, Weese-Mayer DE, Cupples LA, Peucker M, Willinger M, Keens TG. Collaborative Home Infant Monitoring Evaluation (CHIME) Study Group. Cardiorespiratory events recorded on home monitors: Comparison of healthy infants with those at increased risk for SIDS. JAMA 2001, 285, 2199–2207. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daftary AS, Jalou HE, Shively L, Slaven JE, Davis SD. Polysomnography Reference Values in Healthy Newborns. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019, 15, 437–443. [CrossRef]

- Hershenson MB, Colin AA, Wohl ME, Stark AR. Changes in the contribution of the rib cage to tidal breathing during infancy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990, 141, 922–925. [CrossRef]

- Rosen, C.L. Maturation of breathing during sleep. In: Marcus CL, Carroll JL, Donnelly DF, Loughlin GM, editors. Sleep and breathing in children: Developmental changes in breathing during sleep. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Informa Healthcare; 2008. p. 117–30.

- Johnson SM, Randhawa KS, Epstein JJ, Gustafson E, Hocker AD, Huxtable AG, Baker TL, Watters JJ. Gestational intermittent hypoxia increases susceptibility to neuroinflammation and alters respiratory motor control in neonatal rats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2018, 256, 128–142. [CrossRef]

- Gozal D, Reeves SR, Row BW, Neville JJ, Guo SZ, Lipton AJ. Respiratory effects of gestational intermittent hypoxia in the developing rat. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003, 167, 1540–1547. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soy M, Keser G, Atagündüz P, Tabak F, Atagündüz I, Kayhan S. Cytokine storm in COVID-19: Pathogenesis and overview of anti-inflammatory agents used in treatment. Clin Rheumatol. 2020, 39, 2085–2094. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Adams-Chapman I, Fanaroff AA, Hintz SR, Vohr B, Higgins RD. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Neurodevelopmental and growth impairment among extremely low-birth-weight infants with neonatal infection. JAMA 2004, 292, 2357–2365. [CrossRef]

- Di Fiore JM, Martin RJ, Gauda EB. Apnea of prematurity--perfect storm. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2013, 189, 213–222. [CrossRef]

- Raffay TM, Di Fiore JM, Chen Z, Sánchez-Illana Á, Vento M, Piñeiro-Ramos JD, Kuligowski J, Martin RJ, Tatsuoka C, Minich NM, MacFarlane PM, Hibbs AM. Hypoxemia events in preterm neonates are associated with urine oxidative biomarkers. Pediatr Res. 2023, 94, 1444–1450. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Fernández A, Ribot Quetglas C, Herranz Mochales A, Álvarez Ruiz De Larrinaga A, Sánchez Barón A, Rodríguez Rodríguez P, Gil Gómez AV, Pía Martínez C, Cubero Marín JP, Barceló Nicolau M, Cerdà Moncadas M, Codina Marcet M, De La Peña Bravo M, Barceló Bennasar A, Iglesias Coma A, Morell-Garcia D, Peña Zarza JA, Giménez Carrero MP, Durán Cantolla J, Marín Trigo JM, Piñas Cebrian MC, Soriano JB, García-Río F. Influence of Obstructive Sleep Apnea on Systemic Inflammation in Pregnancy. Front Med 2021, 8, 674997. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ślusarczyk J, Trojan E, Głombik K, Budziszewska B, Kubera M, Lasoń W, Popiołek-Barczyk K, Mika J, Wędzony K, Basta-Kaim A. Prenatal stress is a vulnerability factor for altered morphology and biological activity of microglia cells. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015, 9, 82. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao M, Lei J, Deng F, Zhao C, Xu T, Ji B, Fu M, Wang X, Sun M, Zhang M, Gao Q. Gestational Hypoxia Impaired Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthesis Via miR-155-5p/NADPH Oxidase/Reactive Oxygen Species Axis in Male Offspring Vessels. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e032079. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison NR, Johnson SM, Hocker AD, Kimyon RS, Watters JJ, Huxtable AG. Time and dose-dependent impairment of neonatal respiratory motor activity after systemic inflammation. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2020, 272, 103314. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Master ZR, Porzionato A, Kesavan K, Mason A, Chavez-Valdez R, Shirahata M, Gauda EB. Lipopolysaccharide exposure during the early postnatal period adversely affects the structure and function of the developing rat carotid body. J Appl Physiol 2016, 121, 816–827. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyeler SA, Hodges MR, Huxtable AG. Impact of inflammation on developing respiratory control networks: Rhythm generation, chemoreception and plasticity. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2020, 274, 103357. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald FB, Dempsey EM, O'Halloran KD. Effects of Gestational and Postnatal Exposure to Chronic Intermittent Hypoxia on Diaphragm Muscle Contractile Function in the Rat. Front Physiol. 2016, 7, 276. [CrossRef]

- McDonald FB, Dempsey EM, O'Halloran KD. Early Life Exposure to Chronic Intermittent Hypoxia Primes Increased Susceptibility to Hypoxia-Induced Weakness in Rat Sternohyoid Muscle during Adulthood. Front Physiol. 2016, 7, 69. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).