1. Introduction

Chalcones (

1) are intermediary compounds of the biosynthetic pathway of a large and widespread group of plant constituents known collectively as flavonoids [

1,

2]. Among the naturally occurring chalcones and their synthetic analogs, several compounds displayed cytotoxic (cell growth inhibitor) activity toward cultured tumor cells. Chalcones are also effective

in vivo as cell proliferating inhibitors, antitumor promoting, anti-inflammatory, and chemopreventive agents [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

The molecular mechanisms of the published biological/pharmacological effects can be associated with their (a) non-covalent interactions with biological macromolecules and (b) covalent modification of preferably the soft nucleophilic thiol function(s) of amino acids, peptides, and proteins [7-13]. This latter reaction can alter intracellular redox status (redox signaling), which can modulate events such as DNA synthesis, enzyme activation, selective gene expression, and cell cycle regulation [

14,

15]. Several biological effects (e.g., NF-κB pathway inhibition (anti-inflammatory effect) [

16,

17], activation of the Nrf2 pathway (antitumor/cytoprotective effect) [17-19], inhibition of protein kinases (antitumor effect) [7-9], and interaction with tubulin at colchicine binding site (antimitotic effect) [6-12] of chalcones have been associated with their Michael-type reactivity toward cysteine residues of proteins. It was suggested that the lower GSH depletion potential of chalcones with strong electron donor substituents (e.g., dimethylamino) on the B ring could be the consequence of the lower Michael-type reactivity of the derivatives toward GSH [

20]. On the other hand, higher reactivity toward GSH and other thiols was found to parallel with higher NQO1-inducing potential of the investigated chalcones.[

21].

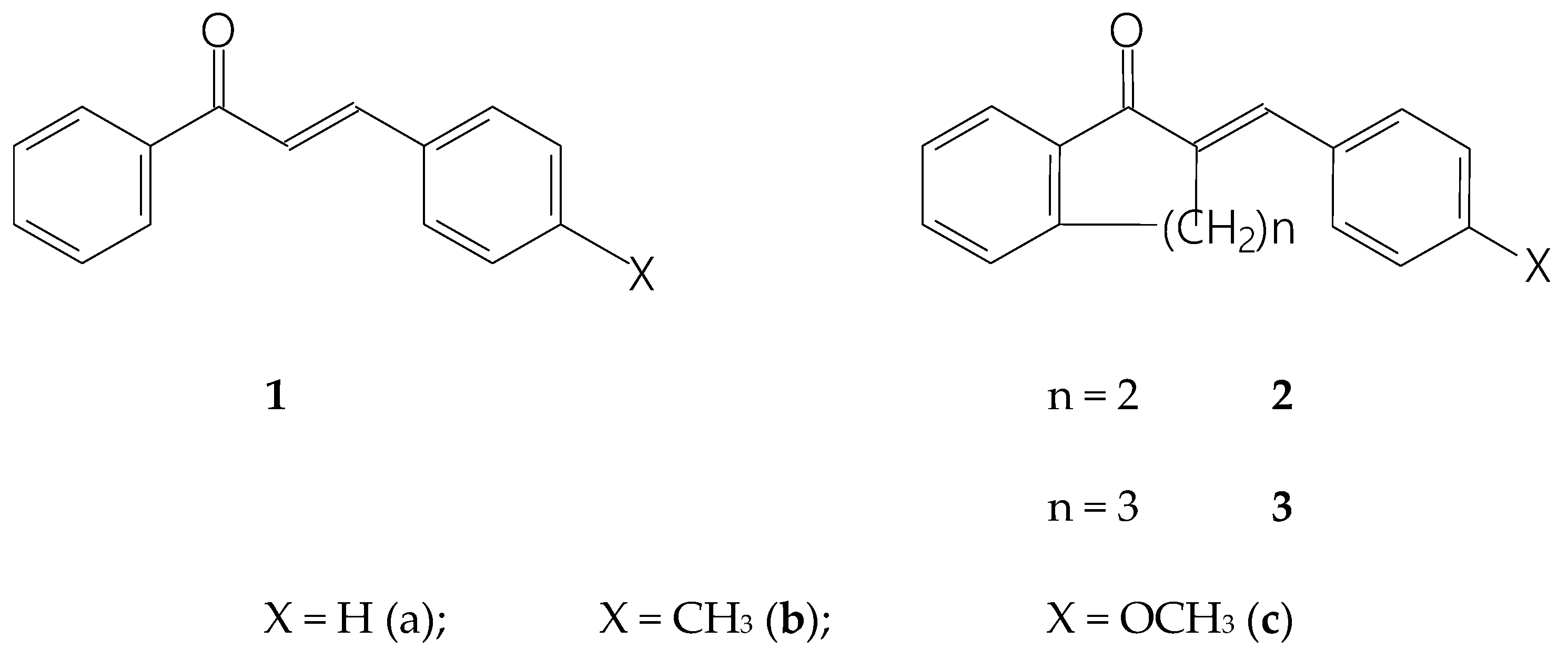

The chalcone structure can be divided into three structural units: the aromatic rings A and B and the propenone linker (

Figure 1). Modifying any of them can tune the main feature of interactions of the synthetic chalcones towards the non-covalent or the covalent pathway. In our previous studies, we have investigated how the substitution of the B-ring and modifying the ring size (n=5-7) of cyclic chalcone analogs affect the cancer cell cytotoxic effect of more than 100 derivatives. It was found that the relative position of the two aromatic rings, as well as the steric properties of the aromatic substituents, plays a determining role in the cytotoxicity of the compounds [22-24].

In our earlier works, reactivity the open-chain

1b,

1c, and their seven-membered cyclic analogs

3b and

3c with reduced glutathione (GSH) and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) was investigated under three conditions with different pH: (a) pH 8.0, (b) pH 6.3, and (c) pH 3.2 [25, 26]. It was found, that both open-chain chalcones (

1b and

1c) showed high and comparable reactivity under each condition [

25]. On the contrary, between the cyclic analogs, the less cytotoxic methyl substituted

3b showed the higher reactivity [

26]. In the comparison of the cytotoxicities of respective six- (

2b and

2c) and seven-membered (

3b and

3c) derivatives, a reduction in cytotoxicities was observed in both pairs (

Table 1).

Based on our previous results, we investigated how the ring size and the 4’-substitution affect the thiol-reactivity of 2b and 2c in the present work. Comparison of the initial reactivities of the open-chain 1a and 1b with the respective 3a and 3b showed that the incorporation of a seven-membered ring into the chalcone moiety reduced the initial reactivity of the polar carbon-carbon double bond towards the thiol nucleophiles. However, no previous data have been published on the effect of the ring size of the cyclic chalcone analogs on their reactivity towards thiols. The diastereomeric selectivity of the addition reactions could also be compared using the earlier HPLC-UV method.

Thiol additions to enones are reported to be reversible, resulting in the formation of an equilibrium mixture. To qualitatively characterize the progress of the reactions, the composition of the incubation mixtures was analyzed at the 15, 45, 75, 105, 135, 165, 195, 225, 255, 285, and 315 min timepoints by HPLC-UV. Furthermore, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were used to analyze the stability and regioselectivity of chalcone analogs on a structural basis. In the analyses, methanethiol (CH3SH) and its deprotonated form (CH3S-) were used as model thiols.

3. Discussion

Reactivity of chalcones and chalcone analogs with cellular thiols is considered to be one of the molecular mechanisms of their biological activity. The subject of this study was the thiol reactivity of some cyclic chalcone analogs (

2b and

2c) that displayed different levels of

in vitro cyctotoxic activities towards murine and human cancer cell lines (

Table 1). Spontaneous thiol reactivity with GSH and NAC of

2b and

2c was investigated under the previously used

in vitro conditions [

25,

26].

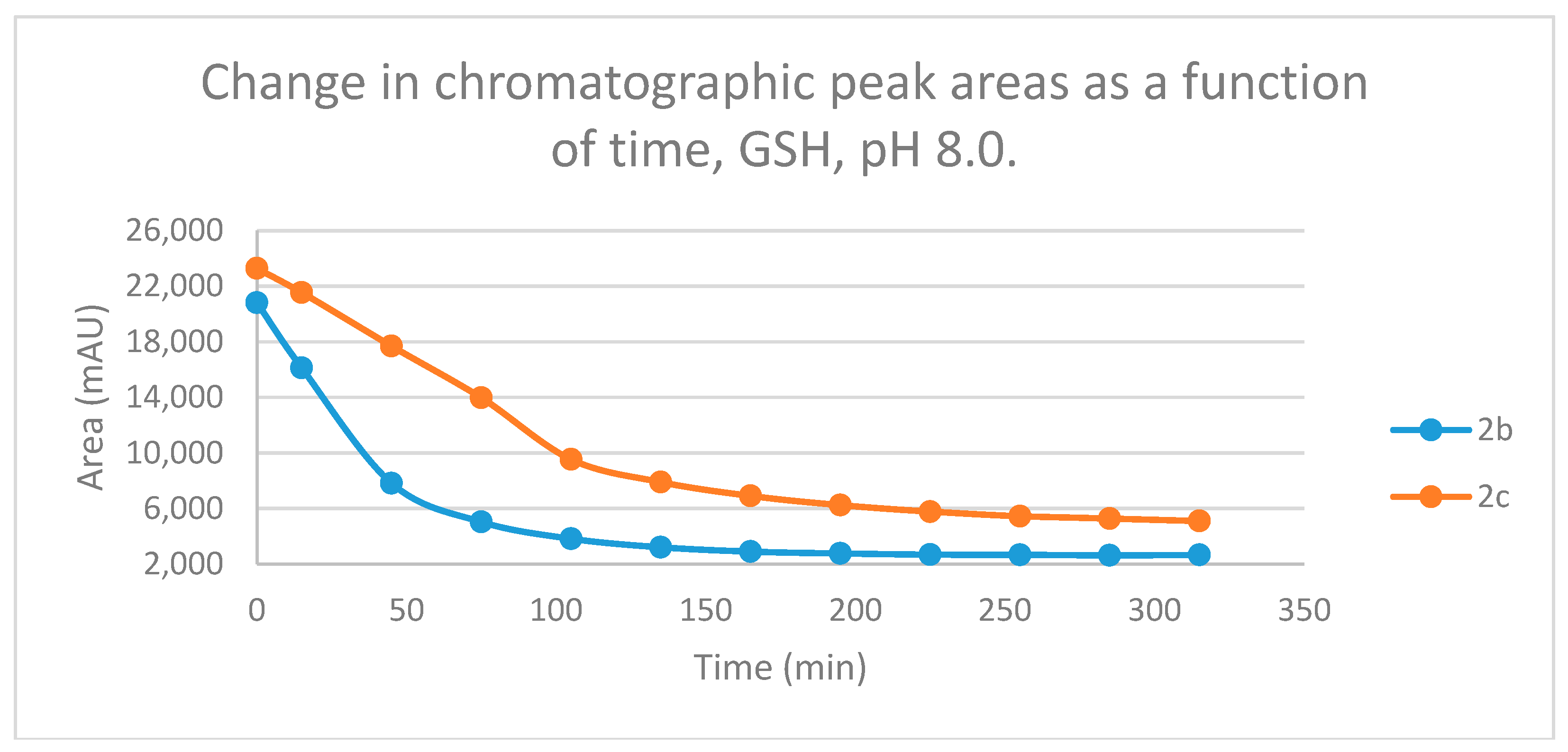

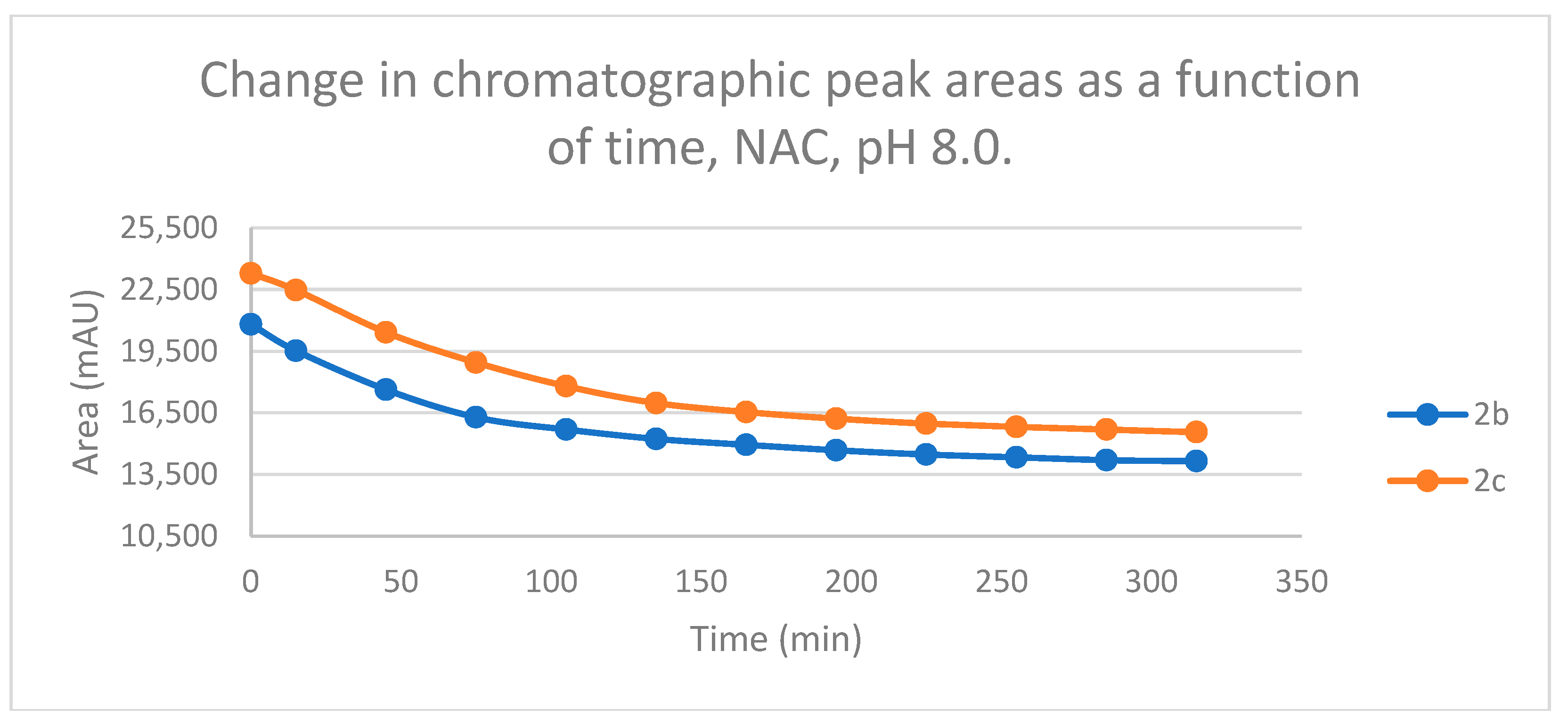

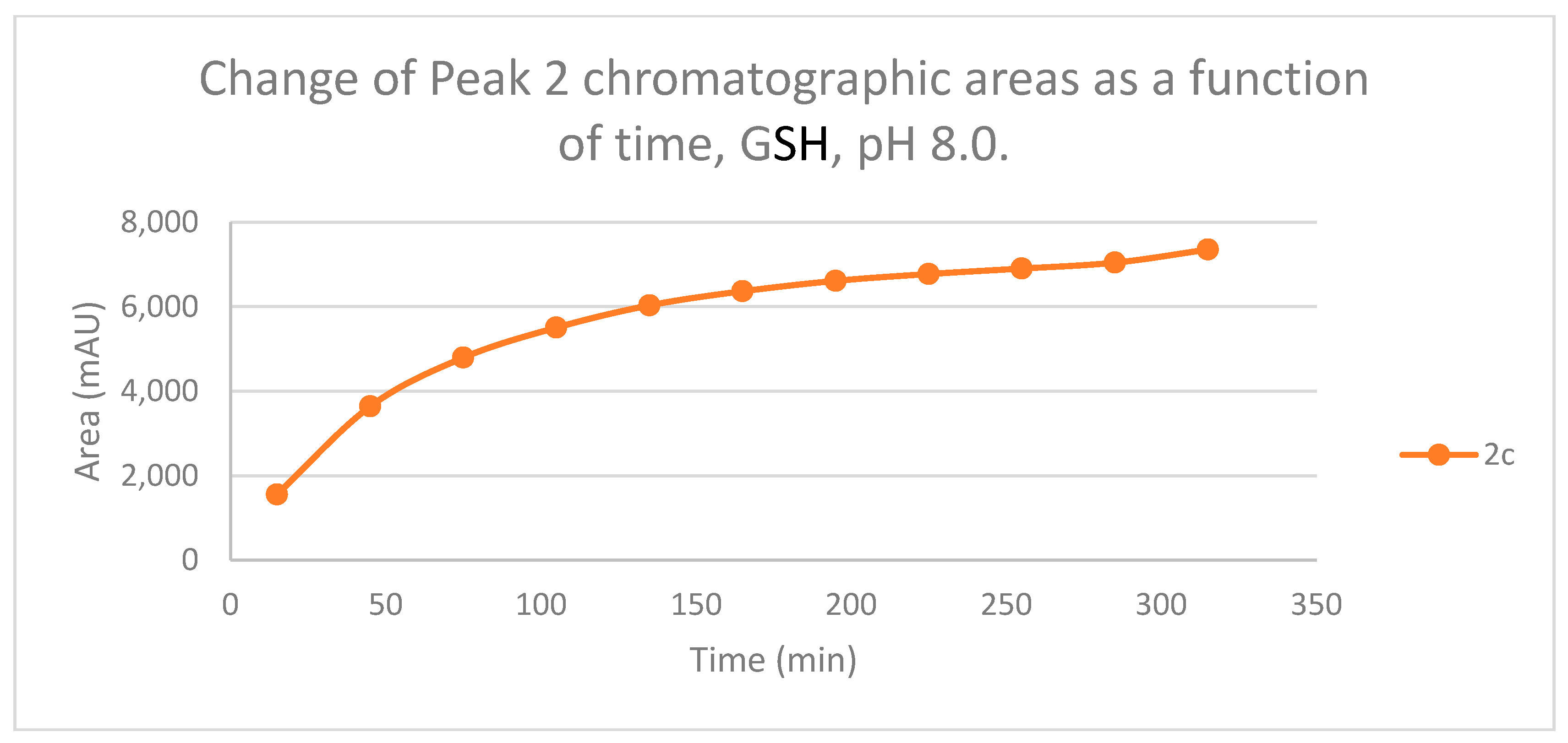

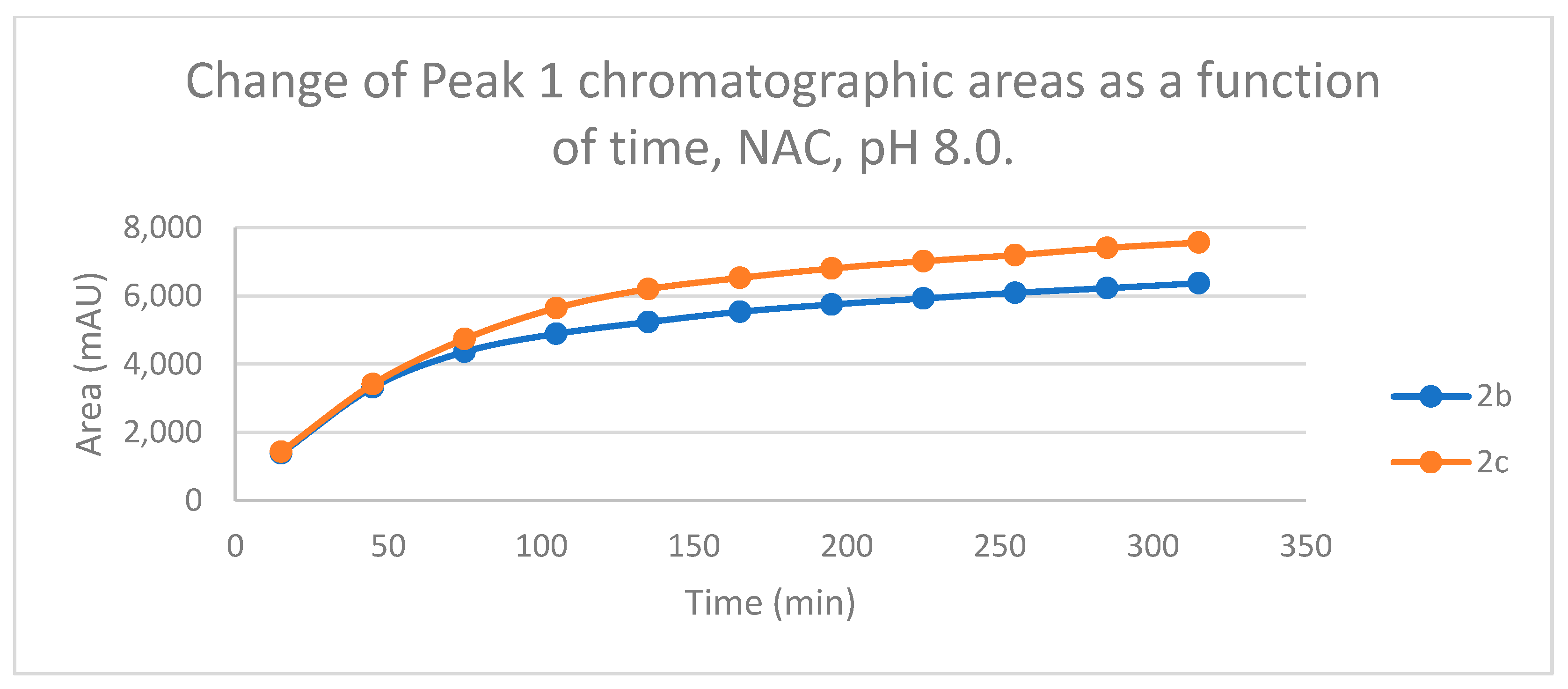

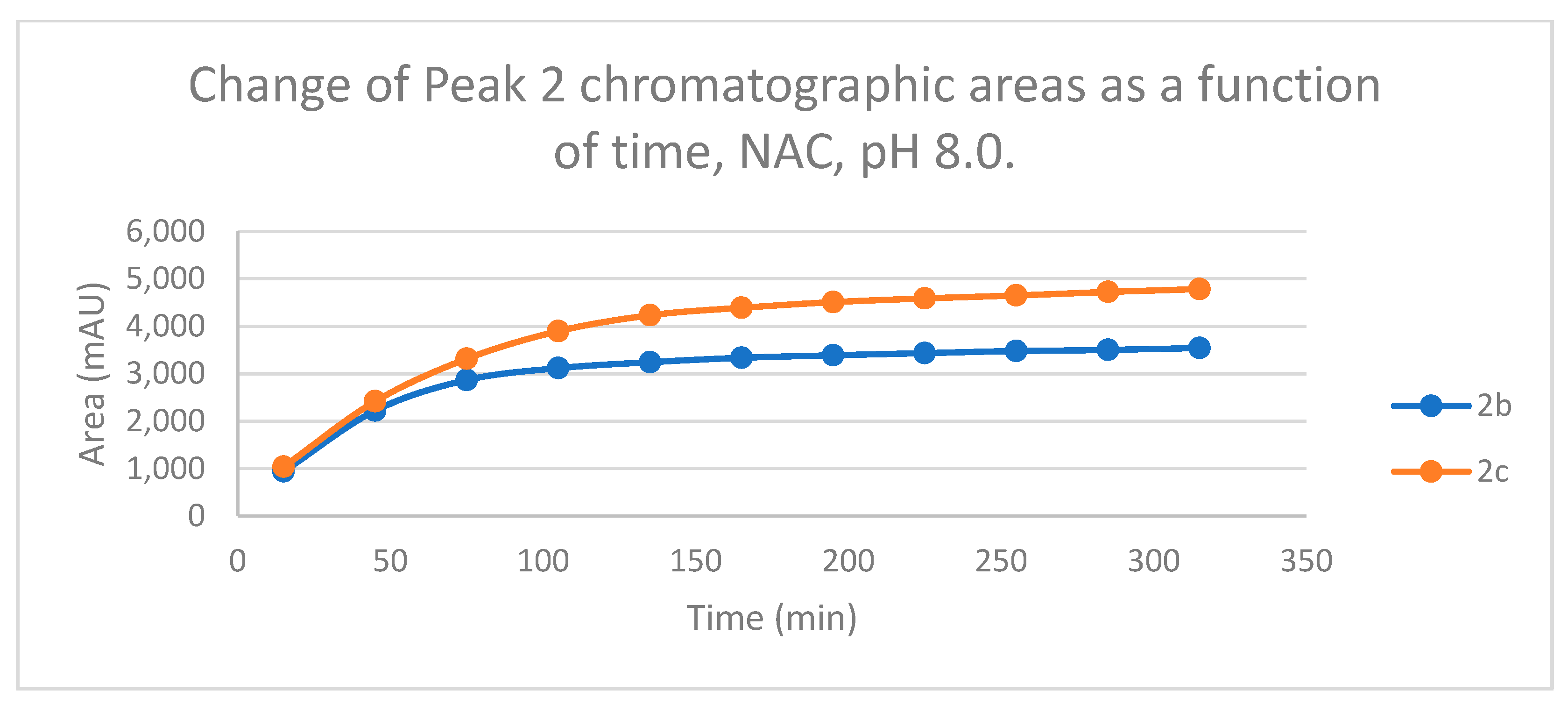

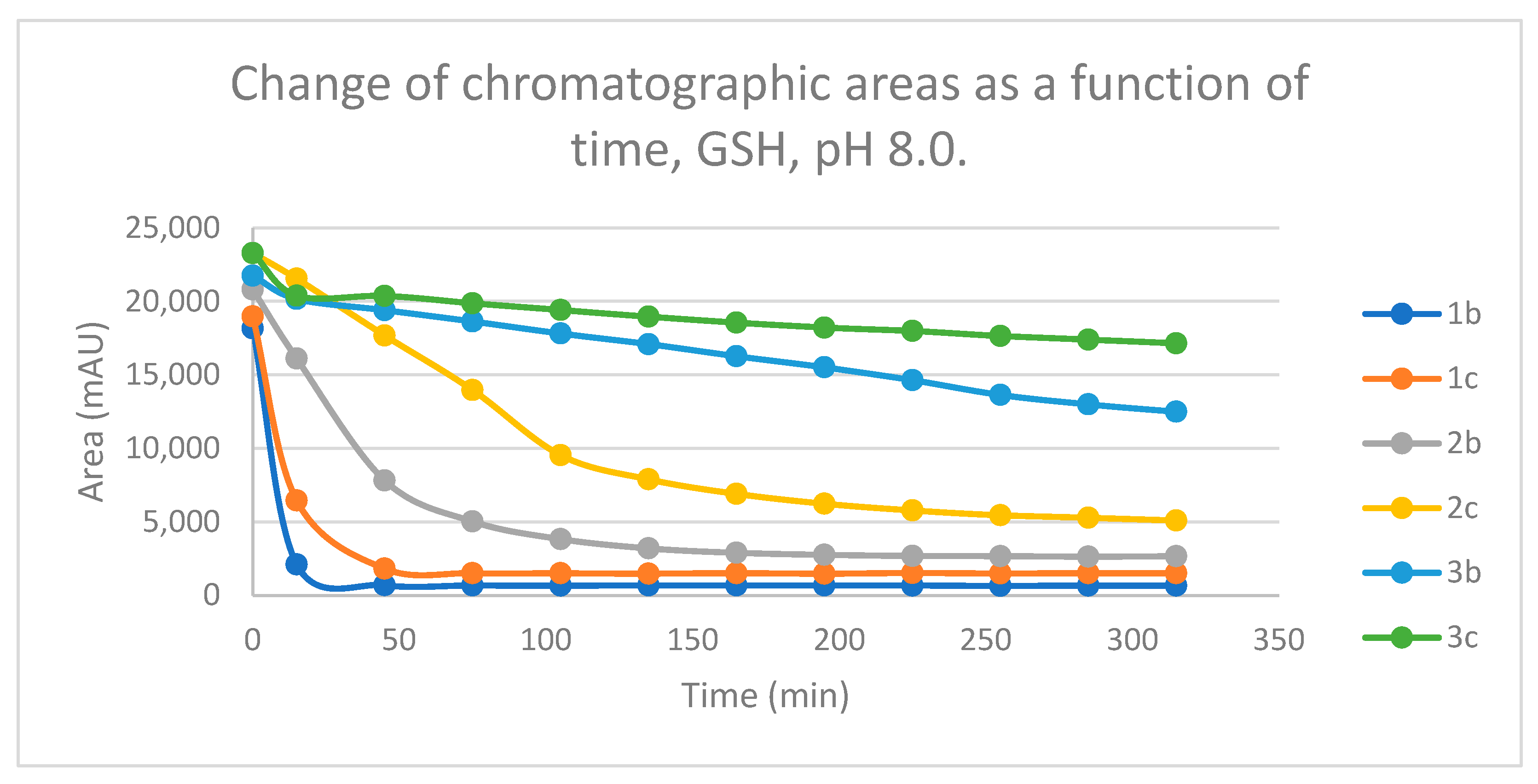

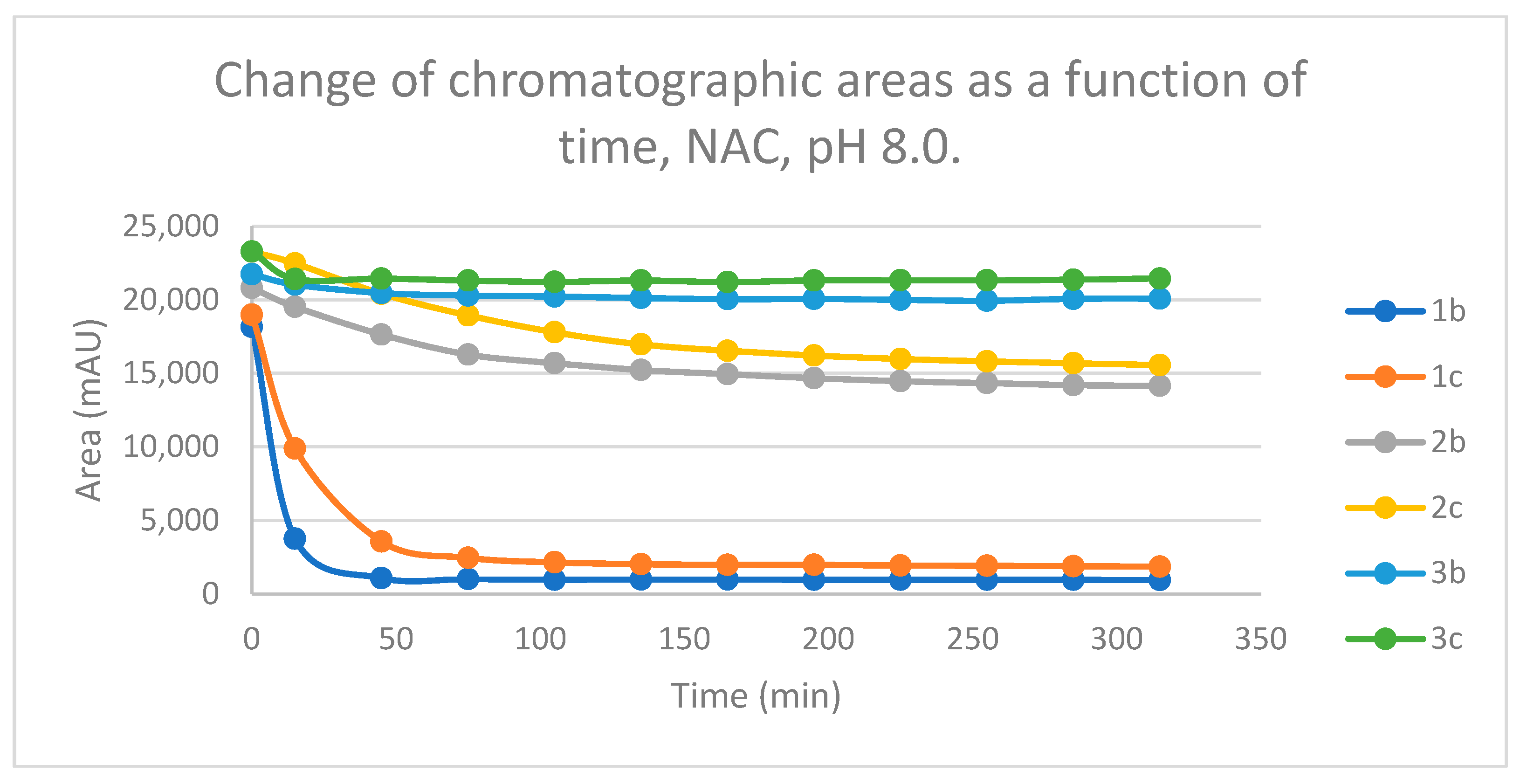

Studies performed under basic (pH 8.0) conditions – mimicking the milieu of the GST-catalyzed reactions [

27] - showed the compounds (

2b and

2c) to have relatively high reactivity with GSH and NAC (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13). Such reactivities are comparable with those of the respective open-chain

1b and

1c [

25]. On the other hand, both the initial reactivity and the 315-minute conversion of

2b and

2c are much higher than those of the respective seven-membered analogs

3b and

3c [

26]. The composition of the incubation of

2b with GSH reached the equilibrium by the end of the 315 minutes incubation periods. The composition of the other incubations is also close to the equilibrium (

Figure 12).

The (quasi)equilibrium composition (pH 8.0) of the chalcones with different substituents (

b and

c) are rather similar with both GSH and NAC. The conversion of the methyl-substituted derivatives (

b) is somewhat higher in each case. The respective values of the GSH and the NAC incubations, however, are different. The GSH incubations of chalcones

2 and

3 are much higher in the corresponding conjugates than the NAC incubations. Compositions were most shifted towards the product formation in the case of the conformationally most flexible open chain chalcones (

1) (

Figure 14 and

Figure 15). Based on these observations, the differences can be explained by the higher conformational mobilities (entropy tag) of the GSH-conjugates.

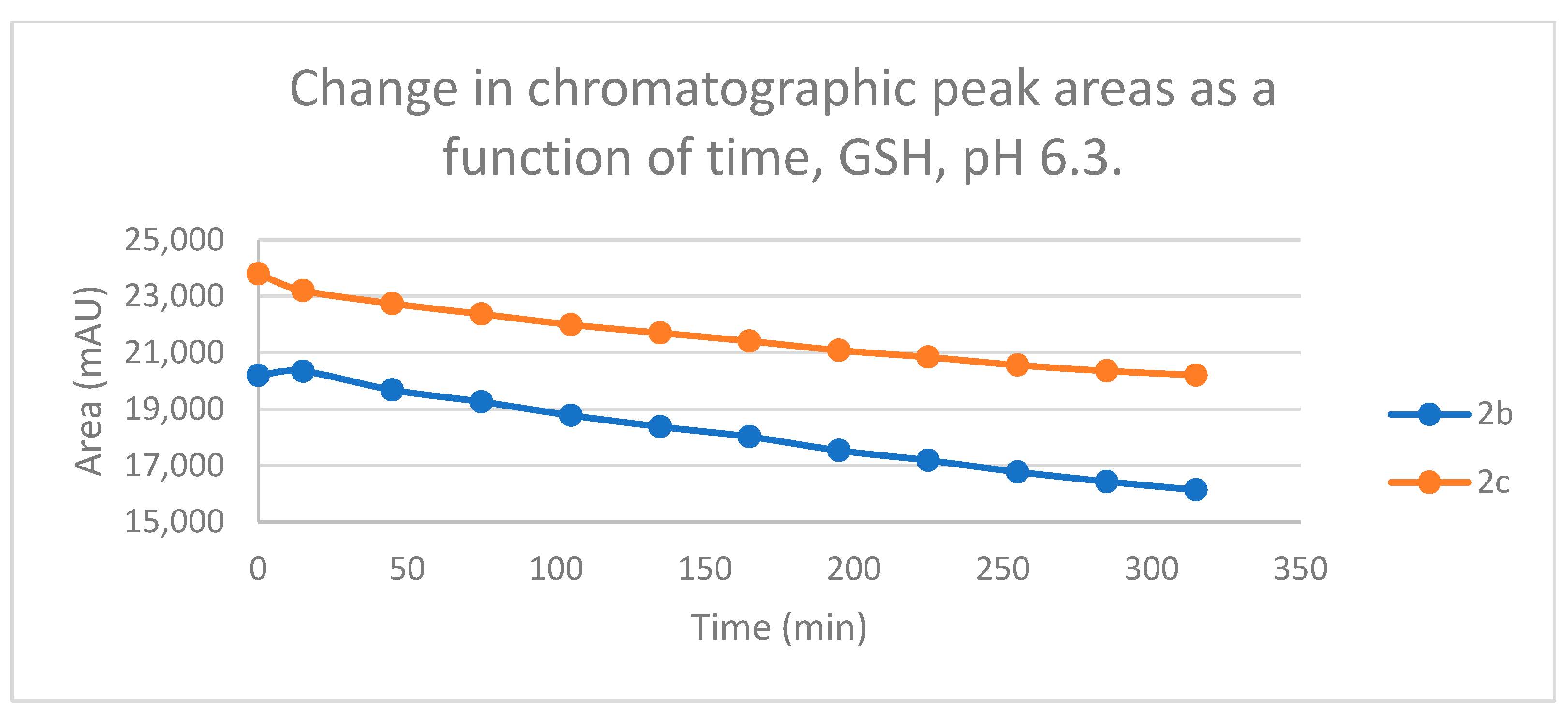

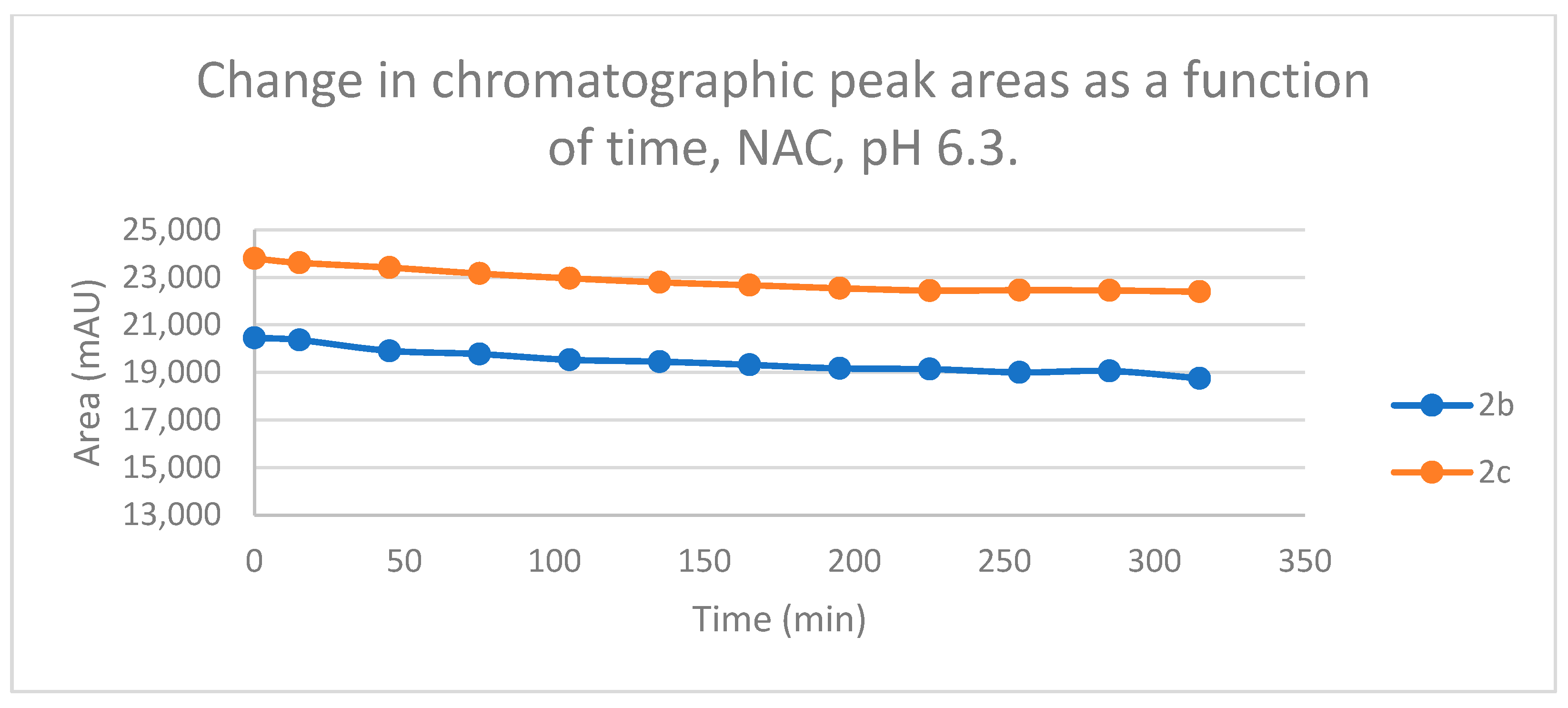

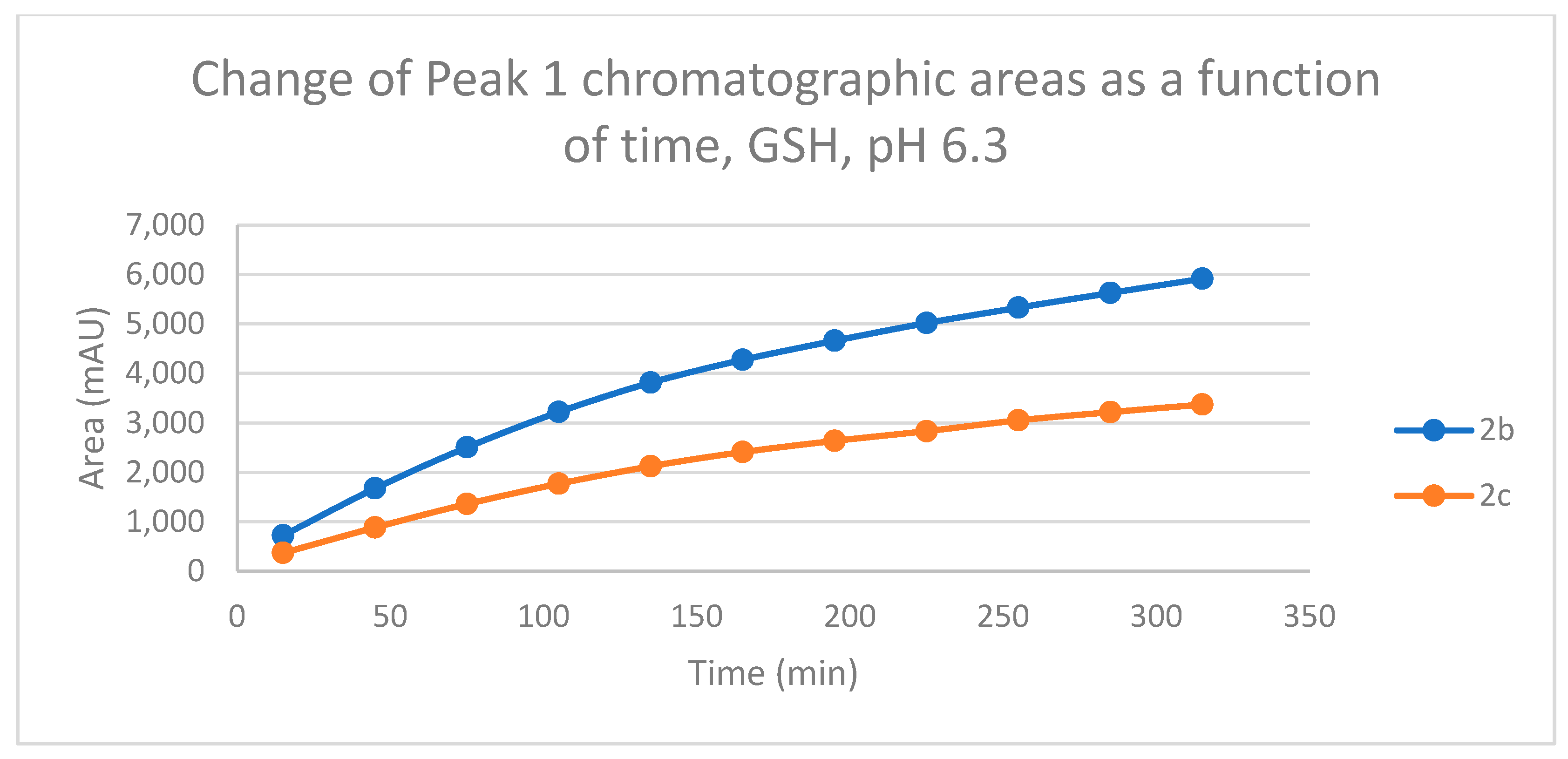

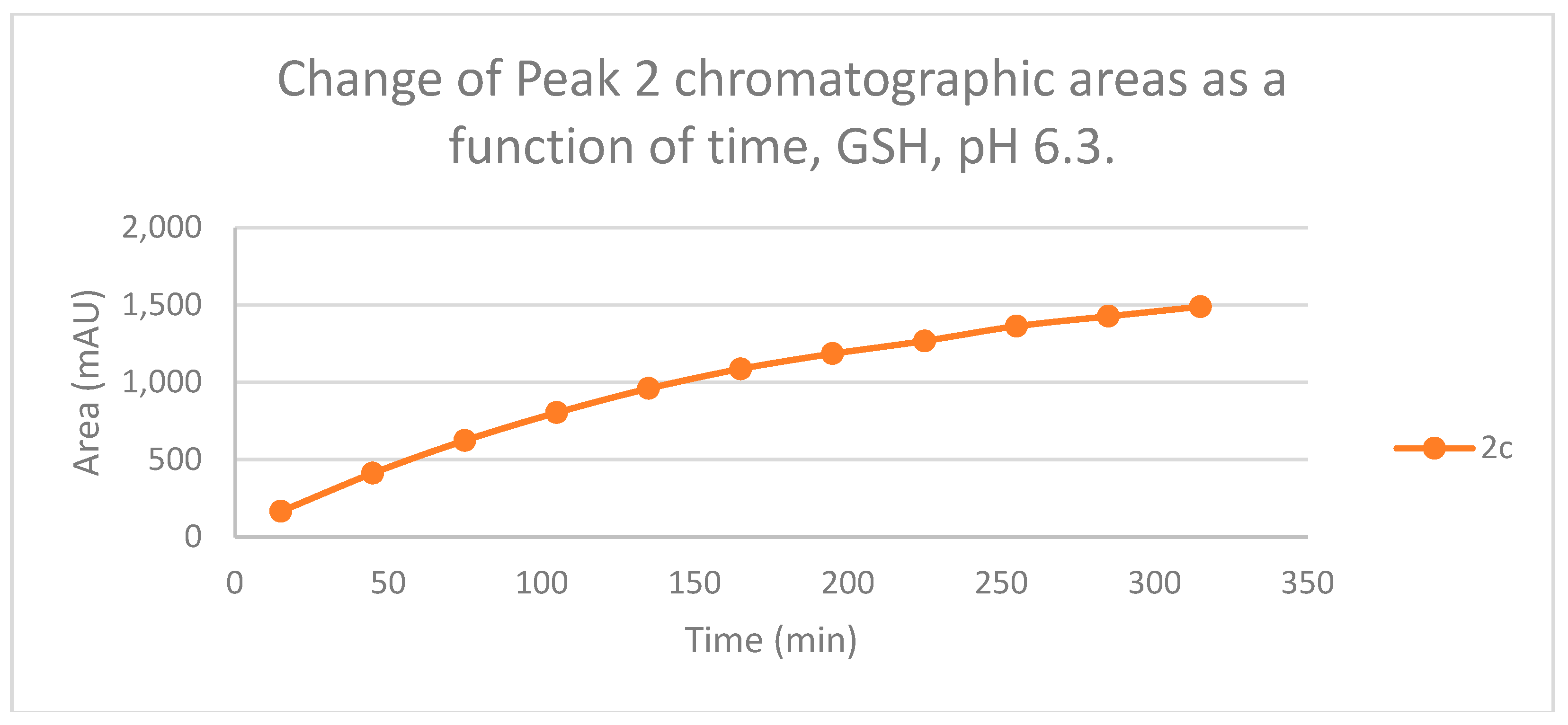

Under slight acidic conditions (pH 6.3), the (quasi)equilibrium compositions of

2 and

3 contain much less GSH and NAC conjugates. Reactivity of the open-chain chalcones (

1b and

1c) is much higher than the two cyclic ones (

2 and

3). Reactivity of each series (

1,

2 and

3) is more pronounced with GSH. Similar to the pH 8.0 conditions, the conversion of the methyl-substituted (

b) derivatives is higher under each investigated condition (

Figures S25 and S26).

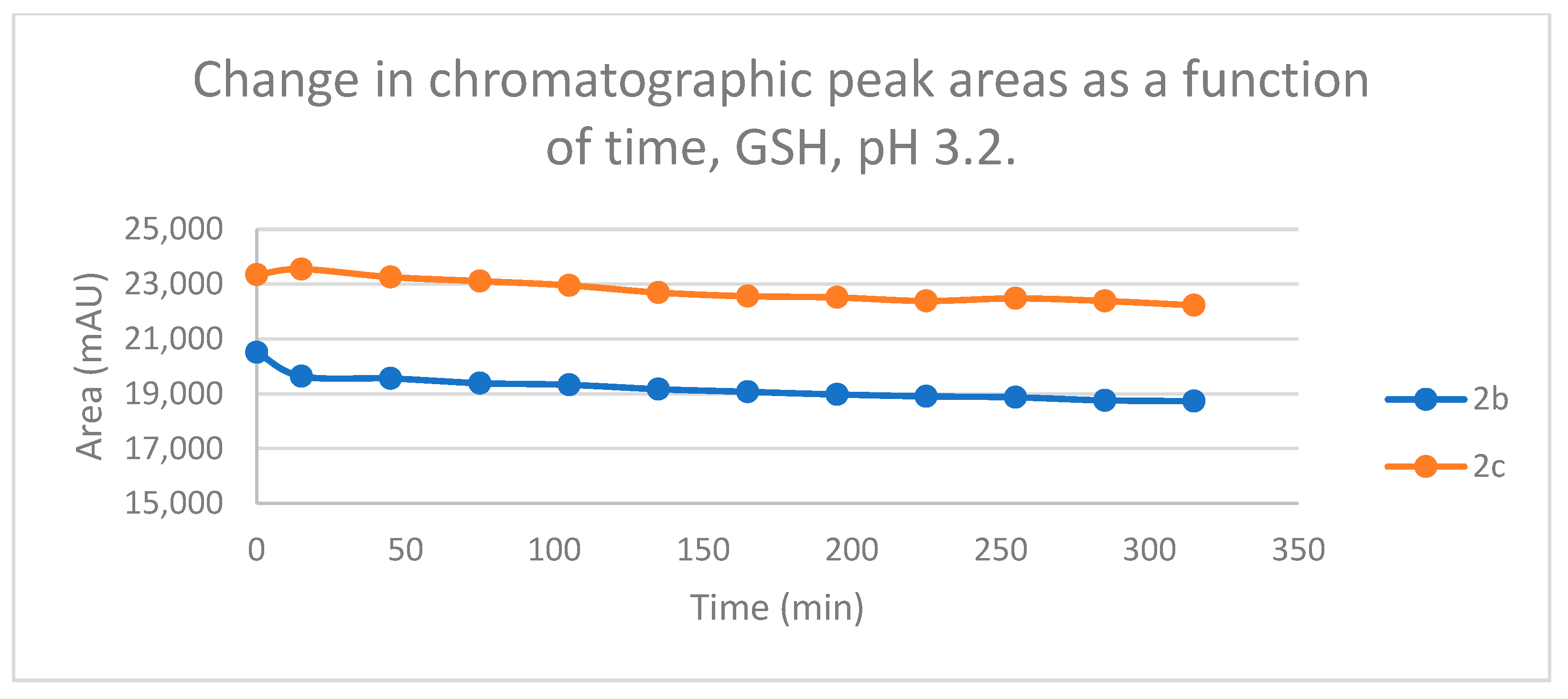

Under acidic (pH 3.2) conditions, the 315 minute-conversions were much lower than under the above conditions. Towards both thiol, the methyl substituted derivatives (

b) showed somewhat higher reactivity. The only significant difference was the more pronounced reactivity of

1b against GSH (

Figures S27 and S28).

13C NMR shifts, indicating the electron density around the particular nucleus of the β-C atom of

2b (136.8 ppm) and

2c (136.6 ppm), - as well as that of

1b and

1c [

25], and

3b and

3c [

26] - were reported to be similar [

32]. Accordingly, the observed difference in the reactivity of chalcones

b and

c can be explained by the stability of the respective thiol adducts. Humphlett et al. demonstrated that the activity of the α-hydrogen atom of the adduct, the resonance stabilization of the enone formed by cleavage, and the anionic stability of the thiolate ion are the determining factors of the reverse process [

33]. Since the 4’-methyl substitution can more effectively increase the electron density on the carbon–carbon double bond, and the formed chalcone is resonance stabilized, the elimination process is more effective in the case of the 4’-OCH

3 (

c) than the 4’-CH

3 (

b) derivatives. This is also reflected in the composition of the (quasi)equilibrium mixtures of the three series: the equilibrium mixture is always reacher in the respective 4’-OCH

3 chalcones (

Figure 12).

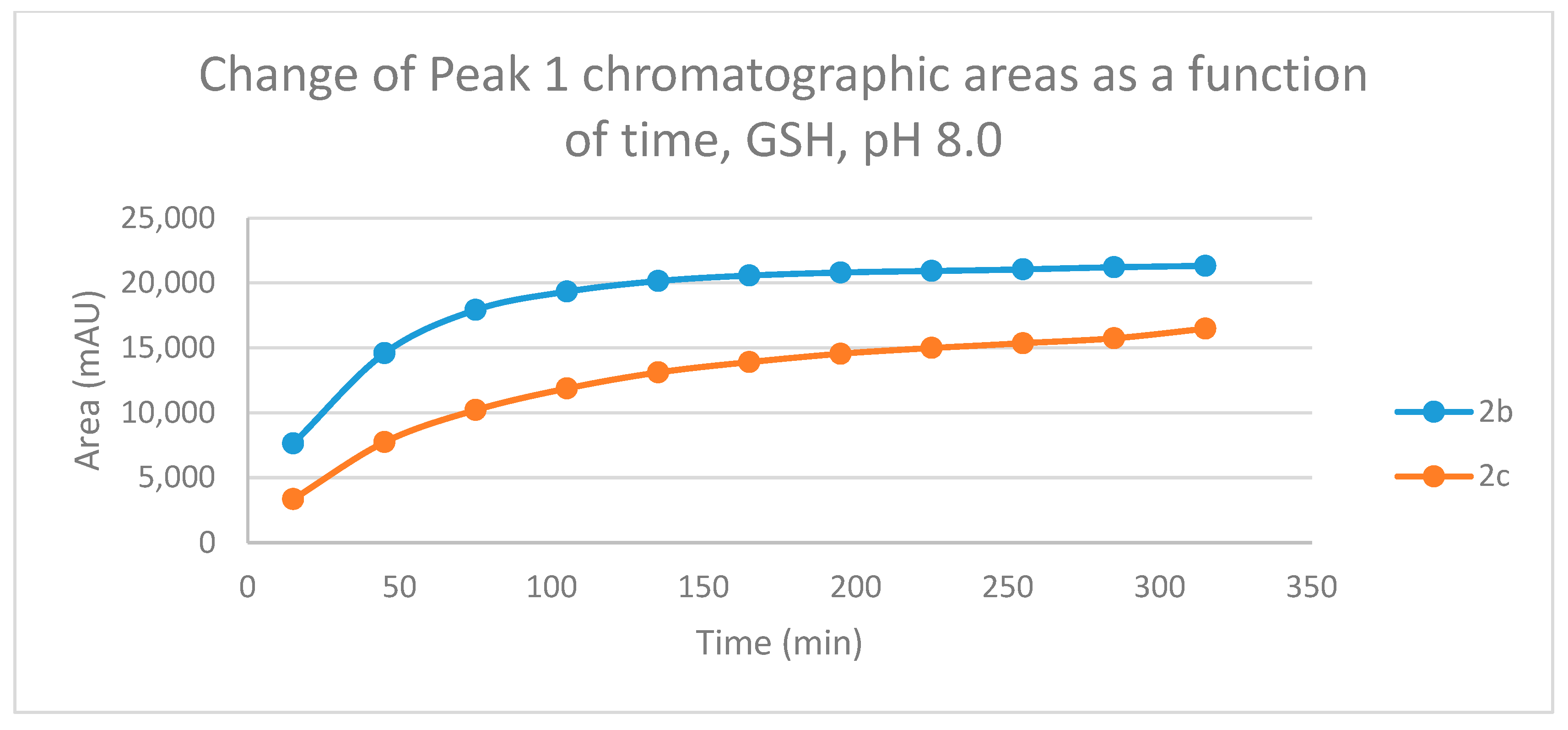

As for the isomeric composition of the thiol-adducts, in the case of the 2b//GSH incubations, formation of only one GSH peak were observed, disrespectfully from the actual pH. Since the tR values of the partially separated 2c-GSH conjugates are rather close to each other, it is reasonable to presume that the formed 2b-GSH diastereomers are not separated under the present chromatographic conditions. The diastereomeric ratio (A(GSH-1)/A(GSH-2)) of the separated 2c-GSH conjugates showed about two-times (2.2) excess of the more polar (GSH-1) peak. The ratio was constant, it did not change over the incubation period. Similar observation was obtained when the incubations of 2c were performed under slightly acidic (pH 6.3), and acidic (pH 3.2) conditions; the A(GSH-1)/A(GSH-2) ratios were about two (2.2) and three (3.3), respectively.

In agreement with the constant A

(GSH-1)/A

(GSH-2) diastereomeric ratios, negligible amount of

2c (

Z)-isomers could be detected. These observations are similar with those obtained with the respective open-chain

1b and

1c [

25], and opposite to those obtained with the seven-membered cyclic analogs

3b and

3b [

26]. In the latter case, much higher amounts of (

Z)-isomers were formed under all the three pH conditions. Since the incubations are kept in the dark, it is the retro-Michael reaction the only source of formation of the (

Z)-isomers.

According to the above, diastereoselective addition of GSH onto the C=C bond of

2c could be observed under all the three experimental conditions. It can be considered that the similar reactions of

2b are also diastereoselective; the experimental results, however, did not provide unambiguous evidence to state that. Since the highest diastereoselectivity ratio (3.2-3.3) was observed under the acidic (pH 3.2) conditions (

Table 2), the results provide further experimental support to consider that the protonated thiol forms a six-membered, hydrogen-bond stabilized intermediate, of which equatorial 4-X-phenyl group determines the structure of the adduct [

31].

HPLC analysis of the NAC incubations under basic conditions (pH 8.0) showed two separated chromatographic peaks with both compounds. The ratios of the NAC-1/NAC-2 peak areas of 2b and 2c were between 1.5-1.8, and 1.4-1.6, respectively. In this case, however, the change in the ratio of the two chromatographic peak areas as a function of the pH, showed different patterns for the two compounds. In case of 2c, no NAC-2 peak could be observed under the two acidic conditions. Thus, reaction of 2c with both thiols resulted in a time-independent constant excess of the more polar diastereomeric adducts without (NAC) or with (GSH) formation of small amount of (Z)-2c.

On the contrary, the A

(NAC-1)/A

(NAC-2) ratios of

2b under the slightly acidic (pH 6.3) and the acidic (pH 3.2) conditions changed between 2.2-4.9 and 0.7-1.8, respectively. In both cases the increase in the ratios was continuous over the incubation time and reached the maximum at the 315 min timepoint. Since relatively high (

Z)-isomeric peaks were observed in the pH 6.3 incubations, the continuously increasing A

(NAC-1)/A

(NAC-2) ratio (between 2.2-4.6) can be partly explained by conversion of the kinetically controlled product to the thermodynamically more stable one, through retro-Michael reaction. Investigations of the respective 4’-CH

3 (

3b) and 4’-OCH

3 (

3c) substituted seven-membered analogs also showed a similar increase in the ratio of the chromatographic areas of the NAC-conjugates accompanied by formation of increased amount of the respective (

Z)-isomers. The ratio of the NAC-1/NAC-2 areas, however, are opposite in the two series. The numerical value of the ratio of the peaks in both series (

2 and

3) was found to be higher in the case of the 4’-CH

3 derivative [

26]. The retro-Michael (elimination) reaction of the thiol-adducts can result not only the (

E) but the (

Z) isomers as well. Difference in thiol-reactivity of the (Z) isomers can be the reason for the different level of the isomeric adducts in the incubation mixtures.

By the end of the incubation period under acidic conditions (pH 3.2), the initial integrated chromatographic area (AUC) of

2b and

2c was reduced by 30.8% and 23.6%, respectively (

Table 3). Similar to the results obtained in the pH 6.3 incubations, only one

2c-NAC adduct could be detected in the HPLC chromatograms. The ratio of the

2b-NAC isomeric peaks continuously increased (from 0.7 to 1.8) and reached its maximum (1.8) at the 315 min timepoint. The AUC values of the 2-NAC conjugates are rather low; however, several other small peaks appeared in the chromatograms. Similar results were observed in the NAC-incubation of the seven-membered analogs

3b and

3c [

26]. The structures of the formed products could not be identified.

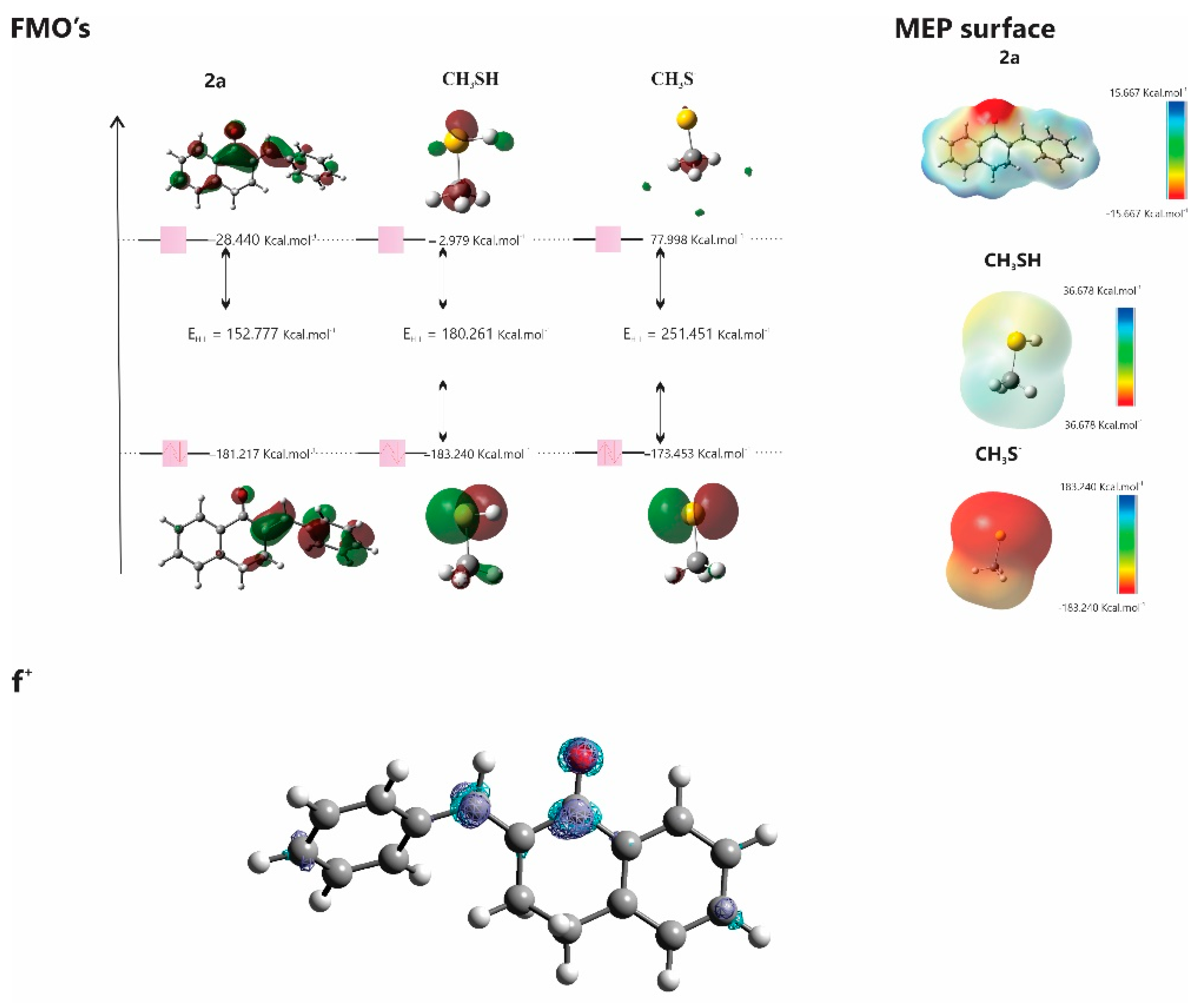

We evaluated the physicochemical properties and varying reactivities of

1a and its cyclic analogs (

2a and

3a) with the modell thiols

CH3SH and

CH3S-. We observed that all compounds but

CH3SH have similar electron-accepting capabilities.

CH3SH exhibits greater chemical stability. LUMO energy analysis indicates that

1a is more acidic compared to

2a and

3a. These results experimentally support the observations, aligning with the Lewis Acid-Base Theory (HSAB), suggesting that reactions prefer partners of similar hardness [

36]. In the case of the α,β−unsaturated ketone, the carbonyl oxygen atom withdraws electrons from the C=C bond –generating an electron deficiency at C

β – the most likely site to receive nucleophilic attacks.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Chemicals and Reagents

L-Glutathione reduced (GSH), and N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) was obtained from Sigma Aldrich (Budapest, Hungary). Methanol CHROMASOLV gradient for HPLC was obtained from Honeywell (Honeywell, Hungary). Trifluoroacetic acid HiperSolve CHROMANORM was obtained through VWR (Budapest, Hungary). Formic acid was obtained at Fischer Chemical. Deionized water for use in HPLC and HPLC-MS measurements was purified by Millipore Direct QTM (Catalogue Number: PROG00002) at the Institute of Pharmaceutical Chemistry of the Faculty of Pharmacy at the University of Pécs. Mobile phases used for HPLC measurements were degassed by an ultrasonic water bath before use. The compounds were synthesized as previously described [

22,

23]. The structure of the parent chalcones (

2b,

2c) and their (

Z)-isomers ((

Z)-

2b, (

Z)-

2c) were verified by HPLC-MS method (

Figures S1-S6). Authentic (Z)-

2b and (Z)-

2c were synthesized as published earlier [

26].

4.2. Preparation of solutions

To evaluate the reactivity of the investigated chalcone analogs with thiols, reduced glutathione (GSH) and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) solutions of three different pHs - 3.2, 6.3, and 8.0 - were prepared The pH of the solutions was set using 1M NaOH. Both the GSH and NAC solutions were prepared in water to a total volume of 1.5 cm3 with a concentration of 2.0 x 10-1 mol.L-1 (0.3 mmol). Chalcone solution was prepared freshly before incubation to a 4.6 volume of HPLC grade methanol (4.6 cm3 of 6.5 x 10-3 mol.L-1, 0.03 mmol).

The NAC or GSH solutions were mixed with the chalcone solution to a final volume of 6.1 cm3, to the final concentration of 4.9 x 10-2 mol.L-1 of thiol, and 4.9 x 10-3 mol.L-1 of chalcone with a molar ratio of 10:1 (thiol:chalcone). The obtained solution was kept in the dark during preparation and analysis in a temperature-controlled (37 °C) water bath for 315 minutes. To monitor the reaction by HPLC-UV, samples were taken at time points 15, 45, 75, 105, 135, 165, 195, 225, 255, 285, and 315 minutes.

4.3. HPLC-UV measurements

The measurements were performed on an Agilent 1100 HPLC system with a UV-Vis detector. The wavelength was set at 260 nm. The separation of the components was carried out in a reversed-phase chromatographic system. A Zorbax Eclipse XBD-C8 (150 mm x 4.6 mm, particle size 5 µm) column (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) was used. The injection volume was 10 µL. During the measurement, the column oven was set at room temperature of 25°C. Data were recorded and evaluated using Agilent ChemStation (B.03.01). The gradient elution was performed at the flow rate of 1.2 mL/min; the mobile phase consisted of (A) water and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and (B) methanol and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. The gradient profile was as follows: an isocratic period of 8 minutes of 40% mobile phase B followed by a linear increase to 60% for 4 minutes, a second linear gradient to 90% for 3 minutes, and a 5-minute isocratic period of 90%. The column was then equilibrated to its initial conditions with a 2-minute linear gradient to 40%, followed by 3 minutes of the isocratic period.

4.4. HPLC-MS measurements

The measurements in the case of chalcone-GSH adducts were performed on HPLC Ultimate 3000 coupled with a mass spectrometer Q Exactive Focus (Dionex, Sunnyvale, USA). The HPLC separation was performed on an Accucore C18 column (150 mm x 2.1 mm, particle size 2.6 µm), and the Accucore C18 defender guard precolumn (150 mm x 2.1 mm, particle size 2.6 µm) was also used. The injection volume was 5 µL; the flow rate was 0.4 mL/min. Data analysis and evaluations were performed using Thermo Scientific TranceFinder version 4.1.191.0. A binary gradient of eluents, consisting of the mobile phases A and B, was used. (A) water and 0.1% formic acid, (B) methanol, and 0.1% formic acid. The gradient elution was as follows: isocratic elution for 1 minute, 20% eluent B continued by a linear gradient to 100% in 14 minutes, followed by an isocratic plateau for 2 minutes. The column was equilibrated to 20% in 0.5 minutes and continued isocratically for 2.5 minutes. The sampler temperature was at room temperature, and the column oven was at 30 °C.

A Q-Exactive Focus mass spectrometer was operated with an Orbitrap mass analyzer and APCI (atmospheric pressure chemical ionization). The ionization parameters were constant during the measurement and were set to sheat gas (nitrogen gas) 30 A.U., auxiliary gas (nitrogen gas) 10 A.U. Probe heater was set to 300 °C. Capillary temperature 350 °C. The spray voltage (+) was 5000 V, and the S lens R.F. level was 50%. Spectra were acquired in the mass/charge ratio (m/z) range of 50-2,000.

In the case of chalcone-NAC adducts, the HPLC specifications were similar to the chalcone-GSH separation method except for the gradient elution timetable, which was as follows. 1 minute of isocratic elution of 10% of eluent B, followed by a linear increase to 95% till 14 minutes B, followed by an isocratic period of 3 minutes at 95% B, eluent B then was decreased to 10% in 0.1 minutes the column was reequilibrate at 10% eluent B for 2.9 minutes. Diode array detector (DAD) was also performed at 260 nm wavelength alongside MS analysis. Mass spectrometry specifications followed the ionization method: HESI +/- having 35000 resolution at 200 m/z and a scan range of 100-1000 amu. The rest of the specifications were the same as the previously mentioned one.

4.5. Molecular modeling analysis

DFT theoretical calculations were performed on G16 software package [

34]. The molecular geometries were optimized using the hybrid exchange and correlation functional with long-range correction, M06-2X, combined with the basis set 6-311++G(d,p) in the gas phase [

35]. Frontier molecular orbitals (HOMO and LUMO) [

36] were calculated by using DFT. Molecular electrostatic potential maps contributed to the global electrophilicity analysis through their electronic isodensity surfaces. MEP [

37] maps provide a visual representation of the electrostatic potential on the surface of a molecule, which can reveal regions of high and low electron density. The electrostatic potential V(

r) [

38] at point

r is defined as.

where Z

a is the charge of nuclei

a at point

ra and

is the charge density at point

r. The local electrophilicity of the molecules was determined by the Fukui function [39, 40] and then it was possible to predict the molecular site selectivity.

where

is the number of electrons in the system, and the constant term

in the partial derivative is external potential.

Figure 1.

Structural formula and numbering of 4-X-chalcones (1) and (E)-2-(4’-X-phenylmethylene)-1-tetralones (2) and -benzosuberones (3).

Figure 1.

Structural formula and numbering of 4-X-chalcones (1) and (E)-2-(4’-X-phenylmethylene)-1-tetralones (2) and -benzosuberones (3).

Figure 2.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of chalcones 2b and 2c in the chalcone-GSH incubations at pH 8.0.

Figure 2.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of chalcones 2b and 2c in the chalcone-GSH incubations at pH 8.0.

Figure 3.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of chalcones 2b and 2c in the chalcone–NAC incubations at pH 8.0.

Figure 3.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of chalcones 2b and 2c in the chalcone–NAC incubations at pH 8.0.

Figure 4.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of adduct 1 of 2b and 2c in the chalcone-GSH incubations at pH 8.0.

Figure 4.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of adduct 1 of 2b and 2c in the chalcone-GSH incubations at pH 8.0.

Figure 5.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of adduct 2 of 2c in the chalcone-GSH incubations at pH 8.0.

Figure 5.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of adduct 2 of 2c in the chalcone-GSH incubations at pH 8.0.

Figure 6.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of adduct 1 of 2b and 2c in the chalcone-NAC incubations at pH 8.0.

Figure 6.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of adduct 1 of 2b and 2c in the chalcone-NAC incubations at pH 8.0.

Figure 7.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of adduct 2 of 2b and 2c in the chalcone-NAC incubations at pH 8.0.

Figure 7.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of adduct 2 of 2b and 2c in the chalcone-NAC incubations at pH 8.0.

Figure 8.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of chalcones 2b and 2c in the chalcone–GSH incubations at pH 6.3.

Figure 8.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of chalcones 2b and 2c in the chalcone–GSH incubations at pH 6.3.

Figure 9.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of chalcones 2b and 2c in the chalcone–NAC incubations at pH 6.3.

Figure 9.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of chalcones 2b and 2c in the chalcone–NAC incubations at pH 6.3.

Figure 10.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of adduct 1 of 2b and 2c in the chalcone-GSH incubations at pH 6.3.

Figure 10.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of adduct 1 of 2b and 2c in the chalcone-GSH incubations at pH 6.3.

Figure 11.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of adduct 2 of 2c in the chalcone-GSH incubations at pH 6.3.

Figure 11.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of adduct 2 of 2c in the chalcone-GSH incubations at pH 6.3.

Figure 12.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of chalcones 2b and 2c in the chalcone–GSH incubations at pH 3.2.

Figure 12.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of chalcones 2b and 2c in the chalcone–GSH incubations at pH 3.2.

Figure 13.

HOMO and LUMO plots for 2a, CH3SH, and CH3S- calculated at the M06-2X/6-311++G(d,p) level of theory. MEP surface at ρ(r) = 4.0 × 10−4 electrons/Bohr3 contour of the total SCF electronic density for molecules 2a ,CH3SH, and CH3SH-. Isosurfaces of the nucleophilic attack (f+) for molecule 2a at the M06-2X/6-311++G(d,p) level of theory.

Figure 13.

HOMO and LUMO plots for 2a, CH3SH, and CH3S- calculated at the M06-2X/6-311++G(d,p) level of theory. MEP surface at ρ(r) = 4.0 × 10−4 electrons/Bohr3 contour of the total SCF electronic density for molecules 2a ,CH3SH, and CH3SH-. Isosurfaces of the nucleophilic attack (f+) for molecule 2a at the M06-2X/6-311++G(d,p) level of theory.

Figure 14.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of chalcones 1b, 1c, 2b, 2c, 3b and 3c in the chalcone-GSH incubations at pH 8.0.

Figure 14.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of chalcones 1b, 1c, 2b, 2c, 3b and 3c in the chalcone-GSH incubations at pH 8.0.

Figure 15.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of chalcones 1b, 1c, 2b, 2c, 3b and 3c in the chalcone-NAC incubations at pH 8.0.

Figure 15.

Change in the chromatographic peak area of chalcones 1b, 1c, 2b, 2c, 3b and 3c in the chalcone-NAC incubations at pH 8.0.

Table 1.

IC

50 (μM) data of selected

E-2-(4’-X-benzylidene)-1-tetralones (

2) and -benzosuberones (

3) [

22].

Table 1.

IC

50 (μM) data of selected

E-2-(4’-X-benzylidene)-1-tetralones (

2) and -benzosuberones (

3) [

22].

| CCompound |

PP388 |

LL1210 |

MMolt 4/C8 |

CCEM |

| 2a |

30.2 |

121 |

32.4 |

7.42 |

| 2b |

17.7 |

161 |

500 |

460 |

| 2c |

22.1 |

44 |

9.41 |

8.84 |

| 3a |

12.7 |

106 |

42.7 |

28.9 |

| 3b |

11.8 |

25 |

21.3 |

11.4 |

| 3c |

1.6 |

0.34 |

0.47 |

0.35 |

Table 2.

Retention times (tR)1 and integrated peak areas (A) of the investigated cyclic chalcone analogs (2b and 2c) and their GSH adducts2.

Table 2.

Retention times (tR)1 and integrated peak areas (A) of the investigated cyclic chalcone analogs (2b and 2c) and their GSH adducts2.

| pH3

|

Compound |

tR

(E)-isomer |

Area Ratio4

A315/A0

|

tR

(Z)-isomer |

Area

(Z)-isomer |

tR

GSH-1 |

Area

GSH-1 |

tR

GSH-2 |

Area

GSH-2 |

| 3.2 |

2b |

16.8 |

0.91 |

ND5

|

- |

14.7 |

753 |

ND5

|

- |

| 3.2 |

2c |

16.3 |

0.95 |

16.7 |

51.3 |

13.3 |

565 |

13.5 |

171 |

| 6.3 |

2b |

17.2 |

0.80 |

ND5

|

- |

15.3 |

5914 |

ND5

|

- |

| 6.3 |

2c |

16.8 |

0.85 |

17.1 |

67.6 |

14.5 |

3371 |

14.6 |

1489 |

| 8.0 |

2b |

17.1 |

0.13 |

ND5

|

- |

15.1 |

21325 |

ND5

|

- |

| 8.0 |

2c |

16.9 |

0.22 |

17.2 |

85.9 |

14.6 |

16474 |

14.8 |

7353 |

Table 3.

Retention times (tR)1 and integrated peak areas (A) of the investigated cyclic chalcone analogs (2b and 2c) and their NAC adducts2.

Table 3.

Retention times (tR)1 and integrated peak areas (A) of the investigated cyclic chalcone analogs (2b and 2c) and their NAC adducts2.

| pH3

|

Com-pound |

tR

(E)-isomer |

Area Ratio4

A315/A0

|

tR

(Z)-isomer |

Area

(Z)-isomer |

tR

NAC-1 |

Area

NAC-1 |

tR

NAC-2 |

Area

NAC-2 |

| 3.2 |

2b |

16.8 |

0.69 |

ND5

|

ND5

|

15.8 |

738 |

16.2 |

412 |

| 3.2 |

2c |

16.4 |

0.76 |

ND5

|

ND5

|

15.2 |

660 |

ND5

|

- |

| 6.3 |

2b |

17.2 |

0.92 |

17.0 |

119 |

16.2 |

1607 |

16.3 |

327 |

| 6.3 |

2c |

16.8 |

0.94 |

ND5

|

ND5

|

15.7 |

4050 |

ND5

|

|

| 8.0 |

2b |

16.9 |

0.68 |

ND5

|

ND5

|

15.9 |

6372 |

16.0 |

3545 |

| 8.0 |

2c |

16.8 |

0.67 |

ND5

|

ND5

|

15.7 |

7564 |

15.8 |

4785 |

Table 4.

Reactivity indices were obtained for

1a[

26],

2a, 3a[

26]

, CH3SH[

26]

, and

CH3S-[

26] at the M06-2X/6-311++G(d,p) level of theory.

Table 4.

Reactivity indices were obtained for

1a[

26],

2a, 3a[

26]

, CH3SH[

26]

, and

CH3S-[

26] at the M06-2X/6-311++G(d,p) level of theory.

| Descriptors |

1a

kcal.mol-1

|

2a

kcal.mol-1

|

3a

kcal.mol-1

|

CH3SH

kcal.mol-1

|

CH3S-

kcal.mol-1

|

| EHOMO |

-183.25 |

-181.22 |

-180.38 |

-183.240 |

-173.453 |

| ELUMO |

-35.98 |

-28.44 |

-28.44 |

-2.979 |

77.998 |

| ΔEHOMO-LUMO |

147.27 |

152.78 |

151.94 |

180.261 |

251.451 |

| Chemical potential (μ) |

-109.608 |

-108.122 |

-104.405 |

-93.109 |

-47.728 |

|

) |

147.264 |

144.292 |

151.930 |

180.261 |

251.451 |

|

) |

40.791 |

35.976 |

35.873 |

24.047 |

4.530 |