Submitted:

30 April 2024

Posted:

30 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dumont, H. J.; Shiganova, T. A.; Niermann, U. (Eds.). Aquatic invasions in the Black, Caspian, and Mediterranean seas, Springer Science & Business Media 2004, Vol. 35.

- Oğuz, T.; Öztürk, B.; Temel, O.Ğ.U.Z. Mechanisms impeding the natural mediterranization process of Black Sea fauna. Journal of Black Sea/Mediterranean Environment 2011, 17(3), pp.234-253.

- Boltachev A.; Karpova E. Faunistic Revision of Alien Fish Species in the Black Sea. Russian Journal of Biological Invasions 2014, 5 (4), 225–241. [CrossRef]

- Shalovenkov, N. Alien species invasion: Case study of the Black Sea. Coasts and estuaries. Elsevier, 2019, 547-568. [CrossRef]

- Guskov G.E. Analysis of Distribution of Striped Seabream (Lithognathus mormyrus L., 1758) (Actinopterygii: Sparidae) in the Black Sea. Russian Journal of Biological Invasions, 2021, 12 (2), pp. 176–181. [CrossRef]

- Yankova M.; Pavlov D.; Ivanova P.; Karpova E.; Boltachev A.; Öztürk B.; Bat L.; Oral M.; Mgeladze M. Marine fishes in the Black Sea: recent conservation status. Mediterranean Marine Science 2014, 15(2), pp. 366-379. [CrossRef]

- Çinar, M.E.; Bilecenoğlu, M.; Yokeş, M.B.; Öztürk, B.; Taşkin, E., Bakir, K.;Doğan, A.; Açik, Ş. (2021) Current status (as of end of 2020) of marine alien species in Türkiye. PLoS ONE, 2021, 16(5): e0251086. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J. S.; Grande, T. C.; Wilson, M. V. H. 2016. Fishes of the World. 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, 2016, pp. 707.

- Şalcioğlu, A.; Gubili, C.; Krey, G.; Sakinan, S.; Bi̇lgi̇n, R. Molecular characterization and phylogeography of Mediterranean picarels (Spicara flexuosa, S. maena and S. smaris) along the coasts of Turkey and the Eastern Mediterranean. Regional Studies in Marine Science 2021, 45, 101836, pp 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Froese, R.; Pauly, D. Editors. FishBase. World Wide Web electronic publication. Available online: Search FishBase (accessed on 29/04/2024).

- Dulčić, J.; Pallaoro, A.; Cetinić, P.; Kraljević, M.; Soldo, A.; Jardas, I. Age, growth and mortality of picarel, Spicara smaris L.(Pisces: Centracanthidae), from the eastern Adriatic (Croatian coast). Journal of Applied Ichthyology 2003, 19(1), pp. 10-14. [CrossRef]

- Bektas, Y.; Aksu, I.; Kalayci, G.; Irmak, E.; Engin, S.; Turan, D. Genetic differentiation of three Spicara (Pisces: Centracanthidae) species, S. maena, S. flexuosa and S. smaris: and intraspecific substructure of S. flexuosa in Turkish coastal waters. Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2018, 18(2), pp. 301-311. [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, P. Differences among fish assemblages associated with nearshore Posidonia oceanica seagrass beds, rocky–algal reefs and unvegetated sand habitats in the Adriatic Sea. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2000, 50(4), pp. 515-529. [CrossRef]

- Karachle, P. K.; StergIou, K. I. Diet and feeding habits of Spicara maena and S. smaris (Pisces, Osteichthyes, Centracanthidae) in the North Aegean Sea. acta aDrIatIca 2014, 55(1), pp. 75-84.

- Tsangridis, A.; Filippoussis, N. Length-based approach to the estimation of growth and mortality parameters of Spicara smaris (L. ) in the Saranikos Gulf, Greece, and remarks on the application of the Beverton and Holt relative yield per recruit model. FAO Fish. Rep. 1988, 412, pp. 94-107.

- Ismen, A. Growth, mortality and yield per recruit model of picarel (Spicara smaris L.) on the eastern Turkish Black Sea coast. Fisheries Research 1995, 22(3-4), pp. 299-308. [CrossRef]

- Kessler, K. T. A zoological voyage to the northern coast of the Black Sea and Crimea in 1858. Kyiv, Ukraine 1860, 1–248, Pls. 1–2.

- Svetovidov, A.N. The Black Sea Fishes. Nauka, Moscow 1964. [The Fishes of the Black Sea]. Nauka Publ., Moscow-Leningrad, pp. 551. (In Russian).

- Bilgin, Ö.; Çarli, U.; Erdoğan, S.; Mavi̇ş, M. E.; Göksu, M.; Gürsu, G. G.; Yilmaz, M. Determination of Amino Acid Content of Picarel (Spicara smaris) Caught in the Black Sea (Around Sinop Peninsula) Using LC-MS / MS and Its Weight-Length Relationship. Türk Tarım ve Doğa Bilimleri Dergisi 2019, 6(2), pp. 130-136. (In Turkish). [CrossRef]

- Stojanov, S. Zwei fur die ichthyofauna des Schwarzen meers unbenannte arten aus der familie Maenidae. Bulletin de l’Institut Zoologique de l’Academie des Sciences de Bulgarie 1954, 3, pp. 257-271. (In Bulgarian, German summery).

- Stojanov S.; Gueorguiev, G.; Ivanov, L.; Hristov, D.; Kolarov, P.; Alexandrova, K.; Karapetkova M. 1963.The fishes of Black Sea. Varna, Bulgaria, 1963 pp. 246 (In Bulgarian).

- Stanciu M.; Ilie G. Lithognatus mormyrus, a new species of Sparidae at the Romanian littoral. Pontus Euxinus, Studii si cercetari CSMN-Constanta 1980, pp. 107–110.

- Vasil’eva, E.D. Fish of the Black Sea. Key to Marine, Brackish Water,Euryhaline, and Migratory Species with Color Illustrations, Collected by: S.V.Bogorodsky. VNIRO, Moscow, 2007; pp. 238. (In Russian).

- Boltachev A.R.; Karpova E.P.; Kirin M.P. The first discovery of the Atlantic shrew Lithognathus mormyrus (L., 1758) (Osteichthyes, Sparidae) in the Black Sea coastal zone of Crimea). Marine Ecological Journal 2013. T.ХII.No4. C. 96.

- Guchmanidze, A.; Boltachev, A. Notification of the first sighting of sand steenbras Lithognathus mormyrus (Linnaeus, 1758) and modern species diversity of the family Sparidae at the Georgian and Crimean Black Sea coasts. Journal of the Black Sea/Mediterranean Environment 2017, 23(1). pp. 48–55.

- Gus’kov, G.; Zherdev, N; Bukhmin, D. New and Rare Fish Species off the Northern Shore of the Black Sea and Anthropogenic Factors Affecting their Penetration and Naturalization. Sea 2022, 1, pp. 66-81. [CrossRef]

- Engin, S.; Keskin, A.; Akdemir, T.; Seyhan, D. Occurrence and new geographical record of striped seabream Lithognathus mormyrus (Linnaeus, 1758) in the Turkish coast of Black Sea. Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2015, 15(4), pp. 937-940. [CrossRef]

- Satilmis, H.; Sumer, C.; Aksu, H.; Çelik, S. About the new record of striped Seabream, Lithognathus mormyrus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Pisces: Teleostei: Sparidae) from the coastal waters of the southern Black Sea, Türkiye. Journal of Animal and Veterinary Advances 2014, 13(3), pp. 171-173.

- Kasapoğlu, N.; Çankırılıgil, E.; Düzgüneş, Z.; Çakmak, E.; Eroğlu, O. The bio-ecological and genetic characteristics of sand steenbras (Lithognathus mormyrus) in the Black Sea. Journal of the Black Sea/Mediterranean Environment 2020, 26(3), pp. 249-262.

- Aydin, M. The new maximum length of the striped sea bream (Lithognathus mormyrus L., 1758) in the Black Sea region. Aquatic Sciences and Engineering 2018, 33(2), pp. 50-52. [CrossRef]

- Aydin, M.; Sözer, A. The Length–Weight Relationship and Condition Factor of a Non-Native Fish Species: Striped Sea Bream (Lithognathus mormyrus L., 1758) in the Black Sea. Journal of Anatolian Environmental and Animal Sciences 2019, 4(3), pp. 319-324. [CrossRef]

- Karadurmuş, U.; Aydin, M. (2021). Morphological Characterization of Lithognathus mormyrus (Linnaeus, 1758) Populations in the Southern Black Sea (Türkiye). Aquatic Sciences and Engineering 2021, 37(1), pp. 38-45. [CrossRef]

- Maltsev V.; Vasilets V.E. First detection of the striped sea breams Lithognathus mormyrus (Sparidae) off the coast of South – Eastern Crimea. In the collection: Biological diversity: study, conservation, restoration, rational use. In Proceedings of the Materials of the II International Scientific and Practical Conference. 2020. pp. 621-626.

- Drensky P. Synopsis and distribution of fishes in Bulgaria. Annulaire de l’Universite de Sofia, Faculte de Sciences 1948, 44(3), pp. 11-71. (In Bulgarian, English summery).

- Drensky P. Fishes of Bulgaria. Fauna of Bulgaria 1951, 2. Sofia, BAS, 270 p. (In Bulgarian).

- Gueorguiev G.; Alexandrova, K.; Nikoloff, D. Observations sur la reproduction des poisons le long du littoral Bulgare de la Mer Noire. Bulletin de l’Institut Zoologique de l’Academie des Sciences de Bulgarie 1960, 9, pp. 255-292. (In Bulgarian, French summery).

- Manolov J. Apercu sur la composition d’espece de la familie Sparidae (Pisces) dans les eaux du littoral Bulgare de la Mer Noire. Proceedings of the Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries – Varna 1970, 10, pp. 165-189. (In Bulgarian, French summery).

- Bat, L.; Erdem, Y.; Ustaoglu, S.; Yardim, Ö; Satilmis, H. A study on the fishes of the central Black Sea coast of Türkiye. Journal of Black Sea/Mediterranean Environment 2005, 11(3), pp. 281-296.

- Boltachev, A.; Karpova, E.; Danilyuk, O. Findings of new and rare fish species in the coastal zone of the Crimea (the Black Sea). Journal of Ichthyology 2009, 49, pp. 277-291. [CrossRef]

- Papadopol, N.; Antone, V.; Bilba, A. New Data on the Sighting of Rare Fish Species of Mediterranean Origin in Romanian Black Sea Waters. Revista Cercetări Marine-Revue Recherches Marines-Marine Research Journal 2016, 46(2), pp. 4-9. [CrossRef]

- Aydin, M.; Saglam, H. First report of predation on egg capsules of invasive Rapa whelk by sharpsnout seabream (Diplodus puntazzo) in the Black Sea. Thalassas: An International Journal of Marine Sciences 2019, 35, pp. 319-321. [CrossRef]

- Aydın, M.; Özdemir, Ç. Age, growth, reproduction and fecundity of the Sharpsnout Seabream (Diplodus puntazzo Walbaum, 1792) in the Black Sea region. Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2021, 22(5). [CrossRef]

- Aydin, M. Maximum length and weight of sharpsnout seabream (Diplodus puntazzo Walbaum, 1792) for Black Sea and East Mediterranean Sea. Turkish Journal of Maritime and Marine Sciences 2019, 5(2), pp. 127-132.

- Drensky P. Contribution a l’etude des poisons de la Mer Noire, recoltes sur les cotes Bulgares. Journal of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences 1923, 25, pp. 6-112. (In Bulgarian, French Summery).

- Samsun, O.; Akyol, O.; Ceyhan, T.; Erdem, Y. Length-weight relationships for 11 fish species from the Central Black Sea, Türkiye. Ege Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2017, 34(4), pp. 455-458. [CrossRef]

- Karlou-Riga, C.; Petza, D.; Charitonidou, K.; Anastopoulos, P.; Koulmpaloglou, D. S.; Ganias, K. Ovarian dynamics in picarel (Spicara smaris, L., Sparidae) and implications for batch fecundity and spawning interval estimation. Journal of Sea Research 2020, 160, 101894. [CrossRef]

- ŞAHİN, T.; GENÇ, Y. Some biological characteristics of picarel (Spicara smaris, Linnaeus 1758) in the Eastern Black Sea Coast of Türkiye. Turkish Journal of Zoology 1999, 23(5), pp. 149-156. (In Turkish).

- Hammami, I.; Bahri-Sfar, L.; Kaoueche, M.; Grenouillet, G.; Lek, S.; Kara, M.H.; Ben Hassine, O. Morphological characterization of striped seabream (Lithognathus mormyrus, Sparidae) in some Mediterranean lagoons. Cybium 2013, 37(1-2), pp. 127-139.

- Aydın, M. Mırmır balığının (Lithognathus mormyrus L., 1758) Karadeniz’deki varlığı. Turkish Journal of Maritime and Marine Sciences 2017, 3, pp. 49-54.

- Guskov G.E.; Zhivoglyadov A.A.; Chepurnaya T.A.; Shimanskaya E.I. Detection of the Atlantic shrew Lithognathus mormyrus in net catches off the Caucasian coast of the Russian Federation. Modern problems of science and education 2017, (5).

- Dbar, R.S.; Vol’ter, E.R.; Malandziya, V.I. On the question of the invasion of the sand steenbras Lithognathus mormyrus (Linnaeus, 1758) into the Black Sea on the example of the water area of Abkhazia. In Proceedings of the Biologicheskoe raznoobrazie: Izuchenie, sokhranenie, vosstanovlenie, ratsional’noe ispol’zovanie. Mat. II Mezhdunar.nauchno-praktich. konf. (Biological Diversity: Re-search, Conservation, Restoration, and Rational Use.Proc. II Int. Sci.-Pract. Conf. Kerch, (May 27–30,2020)), Simferopol: Arial, 2020, pp. 293–297.

- Karpova, E. P. Naturalization of striped seabream Lithognathus mormyrus (Sparidae) in the Black Sea. Russian Journal of Biological Invasions 2020, 11, pp. 220-224. [CrossRef]

- Khaldi, A.; Chater, I.; Elleboode, R.; Mahé, K.; Chakroun-Marzouk, N. Age, growth and mortality of the striped seabream Lithognathus mormyrus (Linnaeus, 1758) in the Gulf of Tunis (Central Mediterranean Sea). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 2021. 101(1), pp. 159-167. [CrossRef]

- Bauchot, M.L.; Hureau, J.C. Sparidae. In Fishes of the north-eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean. Editor 1 Whitehead P. J. P., Editor 2 Bauchot M. L., Editor 3 Hureau J. C., Editor 4 Nielsen J., Editor 5 Tortonese E., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1986; Volume 2, pp. 883-907.

- Jaerisch, J.; Zander, C. D.; Giere, O. Feeding behaviour and feeding ecology of two substrate burrowing teleosts, Mullus surmuletus (Mullidae) and Lithognathus mormyrus (Sparidae), in the Mediterranean Sea. Bulletin of Fish Biology 2010, 12, pp. 27-39.

- Hamida, N. B. H.; Hamida, O. B. A. B. H.; Jarboui, O.; Missaoui, H. Diet composition and feeding habits of Lithognathus mormyrus (Sparidae) from the Gulf of Gabes (Central Mediterranean). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 2016, 96(7), pp. 1491-1498. [CrossRef]

- Kallianiotis, A.; Torre, M.; Argyri, A. Age, growth, mortality, reproduction and feeding habits of the striped seabream, Lithognathus mormyrus (Pisces: Sparidae) in the coastal waters of the Thracian Sea, Greece. Scientia Marina 2005, 69(3), pp. 391-404. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Al Fergani, E. S. (2016). Reproductive Biology of the Striped Seabream Lithognathus mormyrus (Linnaeus, 1758) from Al Haneah Fishing Site, Mediterranean Sea, Eastern Libya. Journal of Life Sciences 2016, 10, pp. 171-181. [CrossRef]

- Reis, I.; Ateş, C. Age, growth, length–weight relation, and reproduction of sand steenbras, Lithognathus mormyrus (Actinopterygii: Perciformes: Sparidae), in the Köyceğiz Lagoon, Mediterranean. Acta Ichthyologica et Piscatoria 2020, 50(4), pp. 445-451. [CrossRef]

- Emre, Y.; Balik, İ.; Sümer, Ç.; Oskay, D. A.; Yeşilçimen, H. Ö. Age, growth, length-weight relationship and reproduction of the striped seabream (Lithognathus mormyrus L., 1758)(Sparidae) in the Beymelek Lagoon (Antalya, Türkiye). Turkish Journal of Zoology 2010, 34(1), pp. 93-100. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, W.; Bauchot, M.L.; Schneider, M. Fiches FAO d'identification pour les besoins de la peche revision 1. Mediterranee et mer Noire. Zone de peche 37 1987, (2): Vertebres, Rome, FAO, pp. 761-1530.

- Kraljevic, M.; Matic-Skoko, S.; Ducic, J.; Pallaoro, A.; Jardas, I.; Glamuzina, B. Age and growth of sharpsnout seabream Diplodus puntazzo (Cetti, 1777) in the eastern Adriatic Sea. Cahiers de biologie marine 2007, 48(2), pp. 145- 154.

- Chaouch, H.; Hamida, O. B. A. B. H.; Ghorbel, M.; Jarboui, O. Diet composition and food habits of Diplodus puntazzo (Sparidae) from the Gulf of Gabès (Central Mediterranean). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 2013, 93(8), pp. 2257-2264. [CrossRef]

- Mouine, N.; Francour, P.; Ktari, M. H.; Chakroun-Marzouk, N. Reproductive Biology of Four Diplodus Species Diplodus vulgaris, D. annularis, D. sargus sargus and D. Puntazzo (Sparidae) in the Gulf of Tunis (Central Mediterranean). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 2012, 92(3), pp. 623–31. [CrossRef]

- Ventura, D.; Jona Lasinio, G.; Ardizzone, G. Temporal partitioning of microhabitat use among four juvenile fish species of the genus Diplodus (Pisces: Perciformes, Sparidae). Marine Ecology 2015, 36(4), pp. 1013-1032. [CrossRef]

- Pajuelo, J. G.; Lorenzo, J. M.; Domínguez-Seoane, R. Gonadal development and spawning cycle in the digynic hermaphrodite sharpsnout seabream Diplodus puntazzo (Sparidae) off the Canary Islands, northwest of Africa. Journal of Applied Ichthyology 2008, 24(1), pp. 68-76. [CrossRef]

- Chaouch, H.; Hamida-Ben Abdallah, O.; Ghorbel, M.; Jarboui, O. Reproductive biology of the annular seabream, Diplodus annularis (Linnaeus, 1758), in the Gulf of Gabes (Central Mediterranean). Journal of Applied Ichthyology 2013, 29(4), pp. 796-800. [CrossRef]

- Pita, C.; Gamito, S.; Erzini, K. Feeding habits of the gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) from the Ria Formosa (southern Portugal) as compared to the black seabream (Spondyliosoma cantharus) and the annular seabream (Diplodus annularis). Journal of Applied Ichthyology 2002, 18(2), pp. 81–86. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Jerez, P.; Gillanders, B.M.; Rodriguez-Ruiz, S.; Ramos-Esplá, A.A. Effect of an artificial reef in Posidonia meadows on fish assemblage and diet of Diplodus annularis. ICES Journal of Marine Science.: Journal Du Conseil 2002, 59, pp. 59-68. [CrossRef]

- Chaouch, H.; Hadj Hamida, O.B.; Ghorbel, M.; Othman, J. Feeding habits of the annular seabream, Diplodus annularis (Linnaeus, 1758) (Pisces: Sparidae), in the Gulf of Gabes (Central Mediterranean). Cahiers de Biologie Marine 2014, 55(1), pp. 13- 19.

- Alonso-Fernández, A.; Alós, J.; Grau, A.; Domínguez-Petit, R.; Saborido-Rey, F. The Use of Histological Techniques to Study the Reproductive Biology of the Hermaphroditic Mediterranean Fishes Coris julis, Serranus scriba, and Diplodus annularis. Marine and Coastal Fisheries 2011, 3(1), pp. 145–159. [CrossRef]

- Donnaloia, M.; Zupa, W.; Arnesano, M.; Neglia, C.; Facchini, M. T.; Carbonara, P. Reproductive biology of Diplodus annularis (linnaeus, 1758) in the central-western mediterranean seas. Biol Mar Mediterr 2017, 24(1), pp. 182-183.

- Matić-Skoko, S.; Kraljević, M.; Dulčić, J.; Jardas, I. Age, growth, maturity, mortality, and yield-per-recruit for annular sea bream (Diplodus annularis L.) from the eastern middle Adriatic Sea. Journal of Applied Ichthyology 2007, 23(2), pp. 152-157. [CrossRef]

- Gherardi, F. Biological invasions in inland waters: an overview. Biological invaders in inland waters: profiles, distribution, and threats 2007, pp. 3-25.

- Arndt, E.; Givan, O.; Edelist, D.; Sonin, O.; Belmaker, J. Shifts in eastern Mediterranean fish communities: Abundance changes, trait overlap, and possible competition between native and non-native species. Fishes 2018, 3(2), pp. 19. [CrossRef]

- Milardi, M.; Gavioli, A.; Soininen, J.; Castaldelli, G. Exotic species invasions undermine regional functional diversity of freshwater fish. Scientific Reports 2019, 9(1), 17921. [CrossRef]

- Turan, C.; Gürlek, M.; Özeren, A.; DOĞDU, S. A. First Indo-Pacific fish species from the Black Sea coast of Turkey: Shrimp scad Alepes djedaba (Forsskål, 1775)(Carangidae). Natural and Engineering Sciences 2017, 2(3), pp. 149-157. [CrossRef]

- Boltachev, A.R.; Yurakhno, V.M. New data on continuous mediterranization of ichthyofauna of the BlackSea, Vopr. Ikhtiol 2002, 42(6), pp. 744–750.

- Boltachev, A.R.; Karpova, E.P. Morskie ryby Krymskogo poluostrova (Marine Fishes of Crimean Peninsula), Simferopol: BiznesInform 2012.

- Schaltout, M.; Omstedt, A. Recent sea surface temperature trends and future scenarios for the Mediterranean Sea. Oceanologia 2014, 56(3), pp. 411-443.

- Daskalov, G.; Boicenko, L.; Grishin, A.; Lazar, L.; Mihneva, V.; Shlyahov, V.; Zengin, M. 2017. The architecture of collapse: Regime shift and recovery in a hierarchically structured marine ecosystem. Global Change Biology 2017, 23(4), pp. 1486-1498. [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of Mediterranean and Black Sea Fisheries 2022. General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean. Rome: FAO 2022. [CrossRef]

| NIS Fish species |

Finding date | Fishing gear mesh size |

Coordinates | Depth (m) |

Catch quantity (kg) | Mean Length (cm) | Mean weight (g) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude | Longitude | ||||||||

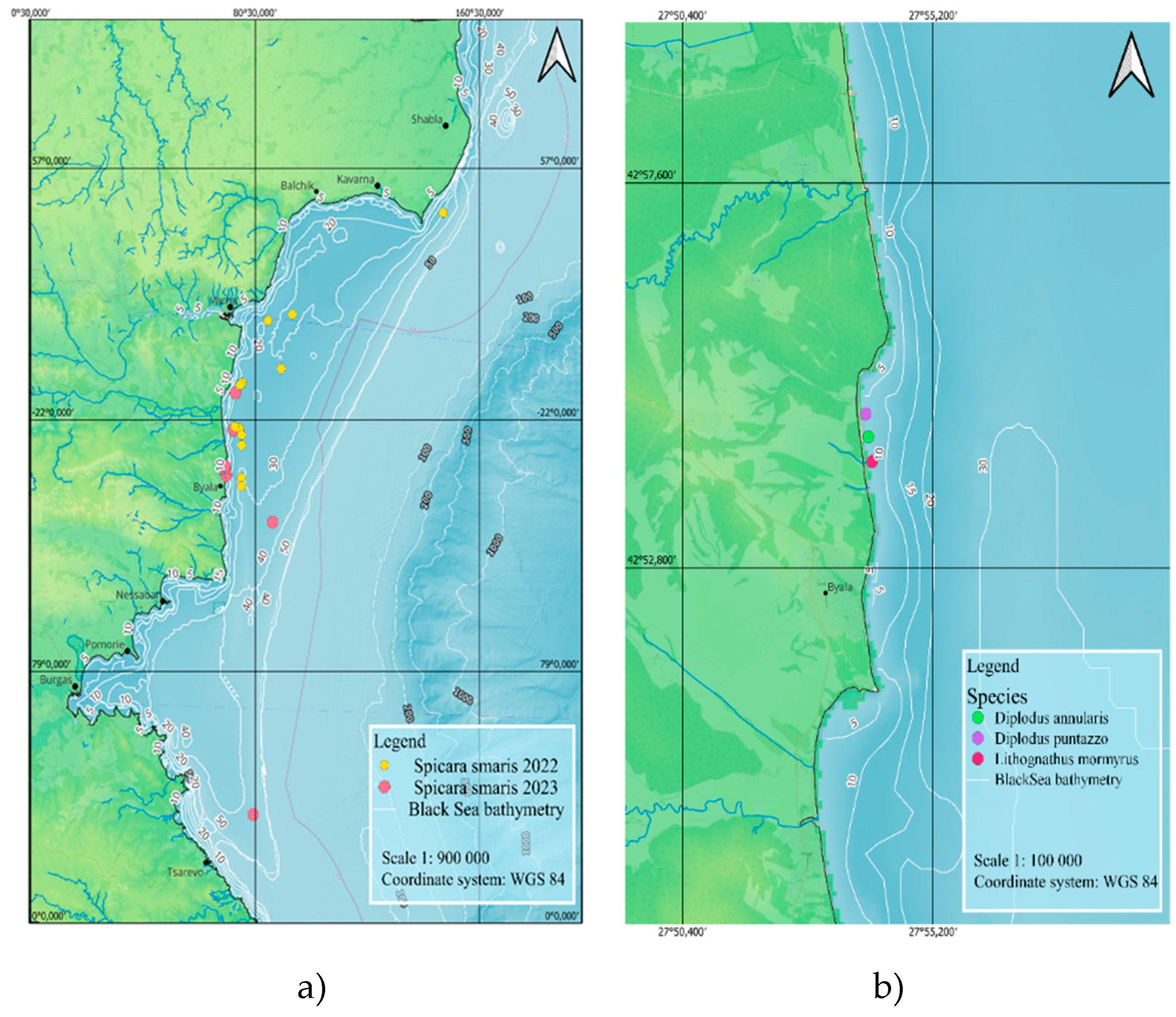

| S. smaris | 13.09.2022 | 16/16 mm | 43.193 | 28.061 | 18 | 21.4 | 0.01057 | 7.9 | 5.61 |

| 1.11.2022 | 16/16 mm | 42.982 | 27.926 | 26.5 | 27.1 | 0.01666 | 9.5 | 8.33 | |

| 1.11.2022 | 18/18 mm | 42.970 | 27.947 | 27 | 23.4 | 0.00846 | 9.6 | 8.46 | |

| 2.11.2022 | 16/16 mm | 43.067 | 27.949 | 24.7 | 27.8 | 0.00884 | 9.7 | 8.84 | |

| 2.11.2022 | 18/18 mm | 43.063 | 27.942 | 24 | 29 | 0.00622 | 8.6 | 6.22 | |

| 10.11.2022 | 16/16 mm | 43.182 | 28.022 | 23.3 | 23.2 | 0.03335 | 8.84 | 6.67 | |

| 11.11.2022 | 18/18 mm | 42.951 | 27.947 | 27.2 | 24.4 | 0.02146 | 8.9 | 7.15 | |

| 15.11.2022 | 16/16 mm | 43.381 | 28.527 | 32.6 | 32.4 | 0.00711 | 8.9 | 7.11 | |

| 18.11.2022 | 18/18 mm | 42.890 | 27.946 | 32.9 | 30.5 | 0.04728 | 9.2 | 7.73 | |

| 31.8.2023 | 16X16 mm | 42.979 | 27.925 | 25 | 26.2 | 40.95 | 12.3 | 19.12 | |

| 31.8.2023 | 16X16 mm | 42.978 | 27.924 | 24.9 | 26.4 | 7.23 | 12.3 | 19.9 | |

| 31.8.2023 | 16X16 mm | 43.048 | 27.929 | 26.2 | 25 | 6 | 12.4 | 18.8 | |

| 31.8.2023 | 16X16 mm | 42.980 | 27.923 | 25.1 | 26.1 | 4 | 12.2 | 19.66 | |

| 31.8.2023 | 32/32 mm | 42.895 | 27.902 | 1 | 5 | 60 | 12.4 | 18.96 | |

| 6.10.2023 | 16X16 mm | 42.261 | 27.980 | 43.3 | 42 | 28.5 | 11 | 14.32 | |

| 13.10.2023 | 16X16 mm | 42.808 | 28.036 | 32.1 | 35.5 | 7.1 | 10.93 | 14.25 | |

| L. mormyrus | 28.8.2023 | 32/32 mm | 42.902 | 27.901 | 1 | 5 | 20 | 20 | 107 |

| D. puntazzo | 30.8.2023 | 32/32 mm | 42.912 | 27.899 | 1 | 5 | 60 | 22.3 | 167.8 |

| D. annularis | 29.8.2023 | 32/32 mm | 42.907 | 27.899 | 1 | 5 | 50 | 19.7 | 114 |

| Species | Location of Detection |

Year of Discovery |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spicara smaris | Coast of Türkiye | 1860-1964 | [17,18] |

| Cape Galata, Varna (Bulgaria) | 1952 | [20] | |

| Coast of Türkiye from Sinop to the Georgian border | 1991 and 1992 | [16] | |

| Sinop (Türkiye) | 2018 | [19] | |

| Lithognathus mormyrus | Varna Bay Romania-Bulgaria |

1958 1980-2013 |

[21] [5,22,23,24] |

| Varna (Bulgaria) | 2007 | [5] | |

| Near the mouth of the Hosta River, Matsesta R., Kudepsta R., Mzymta R. (Russia) | 2007 | [5] | |

| Sukhumi, Pitsunda (Ab-khazia) | 2013 | [5] | |

| Cape Aya (Crimea) | 2013 | [5,24,25] | |

| Crimea | 2013 | [26] | |

| Çamburnu Harbour-Trabzon (Türkiye) | 2013 | [27] | |

|

Diplodus puntazzo Diplodus annularis |

Arhavi-Artvin (Türkiye) Derepazarı-Rize (Türkiye) Pazar-Rize (Turkiey) Rumeli Feneri-İstanbul (Türkiye) Sinop (Türkiye) Kobuleti (Georgia) Dzhubga (Russia) Sevastopol (Crimea) Aya Cape (Crimea) Trabzon (Türkiye) Kazachya Bay (Crimea) Caucasus Yalta (Crimea) Lazarevskoe (Russia) Gelendzhik (Russia) Ordu (Turkiey) Novorossiysk (Russia) Maly Utrish (Russia) Sukko (Russia) Karadag biological station (Crimea) Ordzhonikidze (Crimea) Turkish coast South-Eastern Crimea Near Burgas (Bulgaria) Near Sozopol (Bulgaria) Bulgarian Black Sea coast Sinop and Samsun (Türkiye) Crimea Agigea (Romania) Hopa region (Türkiye) between Sinop and Hopa (Türkiye) Ordu (Türkiye) Black Sea from Balchik to Sozopol (Bulgaria) Bulgarian Black Sea (rare presence) Central Black Sea, Sinop (Türkiye) |

2013 2013-2014 2013 2013 2013 2014 2014 2014 2015 2015 2016 2016 2016 2016 2017 2017-2018 2019 2019 2019 2019 2020 2020 - 1948 1950 1960-1970 between January 1998 and February 2003 from 1999 to 2008 2016 2017 between April 2018 and March 2019 2019 1923-1951 1960-1970 between September 2016 and February 2017 |

[27] Engin et. al. (2015) [27] Engin et. al. (2015) [27] Engin et. al. (2015) [27] Engin et. al. (2015) [28] Satilmis et. al. (2014) [25] Guchmanidze and Boltachev (2017) [5] Guskov (2021) [5] Guskov (2021) [25] Guchmanidze and Boltachev (2017) [29] Kasapoğlu et. al. (2020) [25] Guchmanidze and Boltachev (2017) [26] Gus'kov et. al. (2022) [5] Guskov (2021) [5] Guskov (2021) [5] Guskov (2021) [30,31] Aydin (2018), Aydin and Sözer (2019) [5] Guskov (2021) [5] Guskov (2021) [5] Guskov (2021) [5] Guskov (2021) [5] Guskov (2021) [32] Karadurmuş and Aydin (2021) [33] Maltsev et. al. (2020) [34] Drensky (1948) [35] Drensky (1951) [21,36,37] Gueorguiev et al. (1960), Stojanov et al. (1963), Manolov (1970) [38] Bat et. al. (2005) [39] Boltachev et. al. (2009) [40] Papadopol et. al. (2016) [41] Aydin and Saglam (2019) [42] Aydın and Özdemir (2021) [43] Aydin (2019) [34,35,44] Drensky (1923, 1948,1951) [21,37] Stojanov et al., 1963; Manolov, 1970 [45] Samsun et. al. (2017) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).