1. Introduction

Pesticides play a crucial role in agriculture globally, where they are extensively employed to enhance and protect crop yields by controlling insects, weeds, mollusks, and fungi [

1]. Changing or straying from these traditional practices can be challenging, especially in regions where agriculture is crucial for supporting rural economies [

2,

3]. However, the long-term use of chemical pesticides which has been shown to have adverse effects on ecosystems. There is also increasing evidence of negative impacts on human health, including acute neurologic poisoning, chronic neurodevelopmental impairment, cancers, liver diseases, and potential immune dysfunction [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Farm workers who apply chemical pesticides in particular are at high risk of health complications as those substances can enter the body through the skin, lungs, and mucous membranes, as well as through diet [

9]. Most pesticides, such as chlorpyrifos, are synthetic compounds consisting primarily of organophosphates, which irreversibly inhibit the synthesis of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) [

10,

11]. This inhibition results in excessive stimulation of both muscarinic and nicotinic receptors, leading to symptoms such as cramps, lacrimation, paralysis, muscular weakness, muscular fasciculation, diarrhea, and blurred vision [

12,

13]. Reduced AChE concentrations in capillary blood can indicate exposure to organophosphates. Symptoms of acute organophosphate poisoning include heightened salivation, diarrhea, vomiting, muscle tremors, gastrointestinal discomfort, and confusion [

14]. Symptoms can begin within minutes or hours of exposure and can persist for days to weeks. Long-term exposure to lower doses of organophosphates has been associated with polyneuropathy and cardiovascular diseases [

15]. While reducing overall pesticide use can be problematical, means of mitigating the severity of adverse reactions and diseases caused by exposure to these substances are worth investigating.

If a body is exposed to harmful chemicals from insecticides or pesticides, it can result in oxidative damage by malondialdehyde (MDA) and hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) to various organs, notably the liver [

16]. Despite the liver's vital role in shielding the body from such chemical exposure, excessive pesticide exposure can diminish the liver’s detoxification ability and can lead to liver cell damage [

17]. Additionally, reports indicate that organophosphates can induce the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), disrupting the antioxidant system and causing oxidative damage to cells [

18]. Increased lipid peroxidation and decreased AChE activity are consequences of occupational pesticide exposure in humans [

19,

20]. Such exposure also reduces the concentrations of reduced glutathione, a non-enzymatic antioxidant, and antioxidant enzymes catalase, superoxide dismutase, and glutathione peroxidase [

21,

22]. Antioxidants have been proposed as a potential treatment for acute organophosphate pesticide poisoning because of their ability to counteract ROS damage in the liver [

23,

24].

Continual exposure to pesticides has been linked with the onset of liver disorders, such as hepatitis and fibrosis [

25,

26]. These chemicals, such as organophosphates, can disrupt hepato-biliary functions, signaling liver injury [

27]. Subsequent to liver injury, hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), which are key players in fibrosis, become activated and undergo a transformation into a myofibroblast-like state to engage in the process of injury repair [

28]. The activated HSCs express α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) and produce type-I collagen, which serves as a major component of the extracellular matrix (ECM) [

29]. Therefore, the activation of HSCs plays a pivotal role in the formation of liver fibrosis. Strategies aimed at inhibiting hepatic stellate cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis hold promise in the treatment of fibrosis [

30].

Plants are recognized as valuable resources for mitigating reactive oxygen species (ROS), potentially serving as food ingredients to counteract the adverse effects of pesticides [

31,

32]. An

in vivo experimental study found that green tea extracts, abundant in polyphenols, notably decreased pesticide-induced oxidative stress and pulmonary fibrosis [

33]. Olive leaf extract has also been shown to have notable antioxidant and antiapoptotic effects in rats exposed to chlorpyrifos-induced neurotoxicity and reproductive toxicity [

34].

The

Lauraceae family encompasses 52 genera, totaling around 2,550 species which are distributed primarily in tropical and warm regions of southeastern Asia and Brazil [

35]. Among these,

Litsea martabanica (Kurz) Hook. f. is found in Thailand, China, and Myanmar [

36]. The traditional utilization of this plant is deeply ingrained in the traditional wisdom of highland communities. Various parts of the plant, including roots, leaves, and stems, have been used as medicinal remedies in the highland areas of northern Thailand. These applications extend to treating kidney disease, mitigating toxic allergy symptoms, and facilitating detoxification [

37]. In a previous study, we highlighted the root of

L. martabanica for its potential as an anti-pesticide detoxifying agent which was attributed to its substantial antioxidant and AChE activity [

25]. That investigation also discovered, drawing on the wisdom of highland communities, that in addition to boiling the plant's roots for consumption to mitigate pesticide exposure, the leaves can also be utilized for the same purpose. The present study assessed the impacts of leaf water extract derived from

L. martabanica, including the desirable properties described in traditional knowledge and wisdom, for developing products for use by farmers in highland communities. The use of

L. martabanica leaf water extract could potentially play a role in promoting both environmental sustainability and human health by enhancing healthcare accessibility through its traditional uses to help protect people in lowland areas from toxicity caused by chemical residues in food, potable water, and food crops.

4. Discussion

An investigation was performed to study the detoxifying and antioxidant properties of the root of

L. martabanica in reducing the toxicity induced by chlorpyrifos in rats [

25] which is consistent with the traditional approach to therapeutic use applied by Thai highland communities. Using leaves rather than roots could help reduce the environmental degradation caused by highland communities which traditionally cut down whole trees to obtain the roots. In this study, the identification and authentication of herbal drug substances was crucial to ensuring their authenticity before proceeding to further steps. For that reason, physico-chemical examination, total ash, acid-insoluble ash, ethanol-soluble extractive value, water-soluble extractive value, and water content of the crude drugs (

Table 1) will be among the criteria used to evaluate the quality of the raw material used in future studies. To that end, we examined the microscopic characteristics and chemical compositions to establish

L. martabanica’s monograph to help ensure appropriate quality control of raw material and extracts. Additionally, we investigated the antioxidant effects and anti-pesticide capabilities of

L. martabanica as an aid to the further development of products for human use. This effort aligns with the project’s intention to employ traditional knowledge and wisdom and potentially transforming

L. martabanica leaf water extract into various forms including granules, infusions, and effervescent tablets for possible wider application.

Previous research of bioactive compounds has shown that phenolic and flavonoid compounds are abundant in

L. martabanica roots, suggesting that phenolic and flavonoid compounds may serve as active ingredients [

25]. Furthermore, it is possible that a cluster of terpenoids could serve as the active component in preventing pesticide toxicity [

47]. Moreover, phenolic, and flavonoid compounds possess antioxidant capabilities, which aid in the reduction of oxidative stress [

48]. Consequently, it is plausible that these chemicals are the active components in

L. martabanica leaf water extract that are responsible for the reduction of liver fibrosis activity.

In this study, the chemical composition of the water extracts of L. martabanica leaf were analyzed using HPTLC with detection under UV light at 254 and 366 nm. An anisaldehyde-sulfuric acid, a universal reagent for natural products, and DPPH spraying reagent were also used. Evaluation using accepted chemical standards found the extract of L. martabanica to be free of caffeic acid, ellagic acid, gallic acid, kaempferol, quercetin, and rutin.

Chromatographic techniques can establish chemical profiles that are useful for quality control and for determining the authenticity of raw materials and herbal products. These specifications can provide guidance for quality control and can serve as a reference for future research on the repeatability of the extract preparation process. Phytochemical screening revealed the presence of phenolics, flavonoids, saponins, and terpenoids. The bioactive compounds found in this plant will be used in future studies using bioassay-guided isolation.

Antioxidants are crucial for neutralizing free radicals and safeguarding cells against oxidative damage [

49]. To evaluate antioxidant capabilities, it is necessary to utilize three models, encompassing the DPPH and superoxide radical assays, i.e., employing multiple models is necessary to comprehensively evaluate antioxidant activity and mechanisms, including DPPH assay and superoxide radical assay [

50,

51]. The outcomes from all antioxidant tests in this study demonstrated that the leaf water extract of

L. martabanica displayed considerable antioxidant properties in both DPPH and superoxide radical assays. Moreover, previous research and literature reviews have highlighted the antioxidant activity present in plants of the genus

Litsea, with this attribute being observed across different parts of the plants, including leaves, roots, and stems [

52,

53,

54]. For example, the methanolic extract of

L. glutinosa has demonstrated antioxidant properties including hydrogen peroxide scavenging activity, total antioxidant capacity, nitric oxide scavenging activity assay, and reducing power test [

55]. The 80% ethanol extract and solvent fractions of

L. japonica leaves have radical-scavenging antioxidant activity [

56]. Our own earlier experiments have produced consistent results, confirming that the water extract of

L. martabanica leaf water extract also exhibits antioxidant effects.

The liver is the major organ that deals with drugs and hazardous substances that can cause inflammation and oxidative stress [

57]. Free radicals drive liver cell fibrosis, disrupting normal cellular processes like growth, division, and death regulation. This oxidative stress triggers Kupffer cells to release fibrosis-promoting factors, including TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, and TGFβ, while hepatic stellate cells produce collagen, leading to fibrosis [

58]. Targeting hepatic stellate cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis offers potential in fibrosis treatment [

30]. Compounds like luteolin inhibit fibrosis-related genes, block cytokine pathways, and induce hepatic stellate cell apoptosis [

59]. In our study, we utilized the LX-2 cell line, which possesses characteristics resembling hepatic stellate cells and is commonly used for investigating human hepatic fibrosis. The present study observed that the water extracts ethyl acetate and butanol as well as the residue of

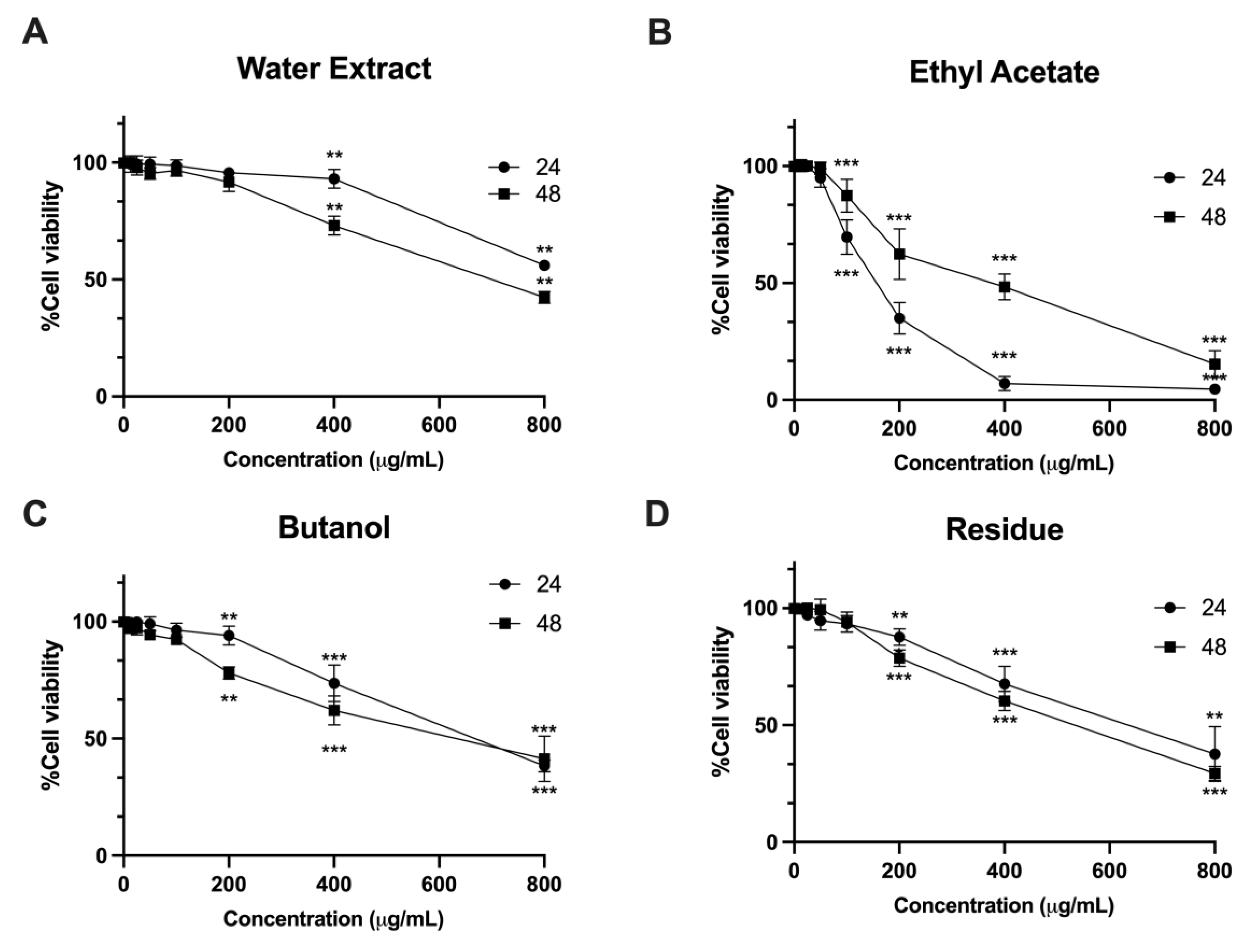

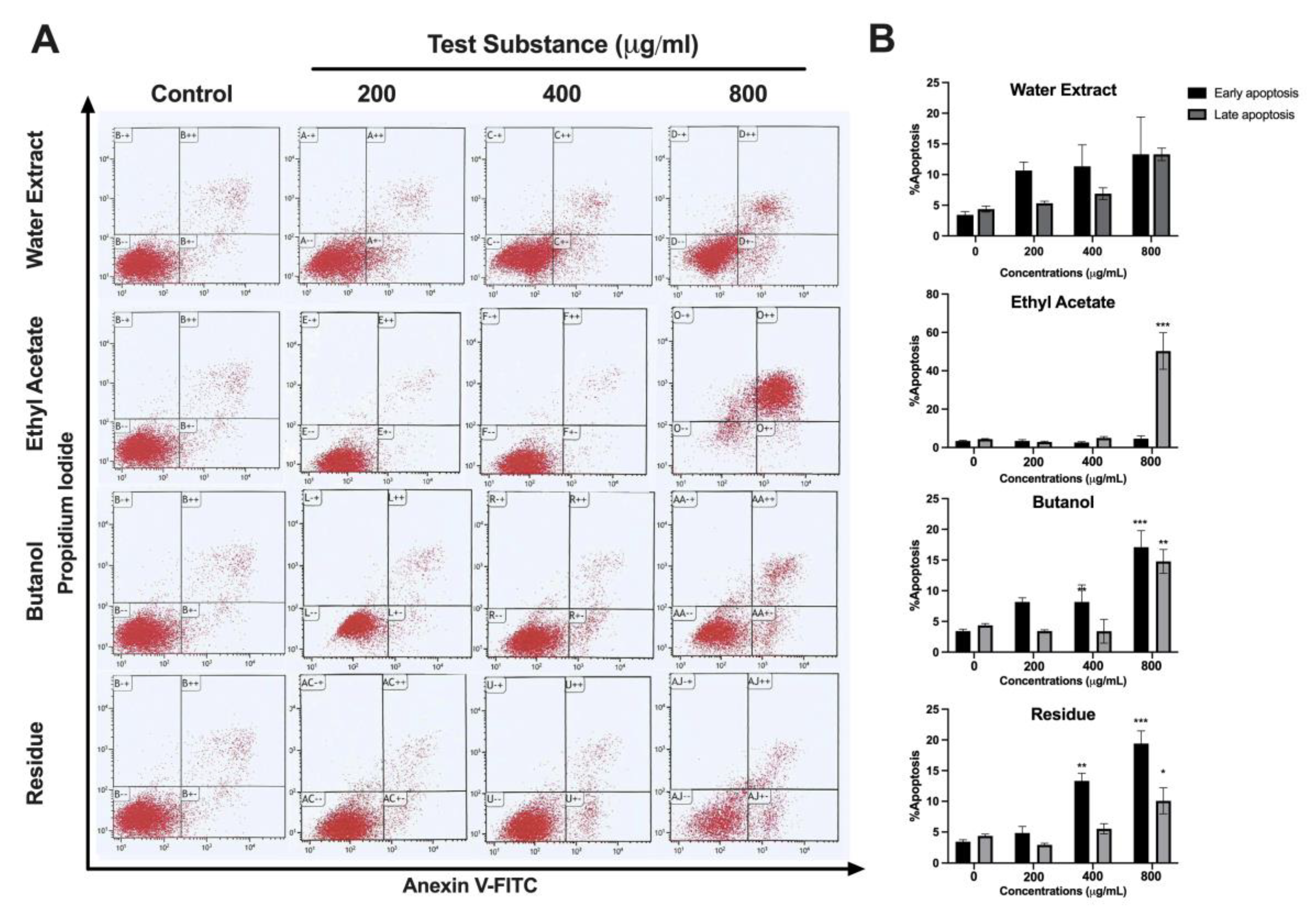

L. martabanica leaf at concentrations ranging from 200 – 800 µg/mL significantly inhibited cell growth compared to control cells. The results also showed that

L. martabanica leaf water extract tended to induce apoptosis, but only at very high concentrations. Ethyl acetate (800 µg/mL), butanol, and residue (400 and 800 µg/mL), were able to induce apoptosis cell death, demonstrating early apoptosis. The identification of ethyl acetate fraction as an active ingredient presents an intriguing possibility for further investigation.

The objective of this test, however, was to verify the efficacy of the selected water extract. Its administration is intended to imitate traditional concoctions based on local knowledge, with the goal of expanding upon traditional knowledge and developing new products for future use. The present animal research study used conventional extraction methods, including water extraction, in order to conduct a more comprehensive examination of the impacts of L. martabanica leaf water extract.

The toxicity of organophosphate pesticides largely arises from inhibiting AChE, which results in an accumulation of acetylcholine [

10].

L. martabanica root water extracts have previously been shown to have anti-pesticide effects, such as improving AChE activity in rats exposed to chlorpyrifos [

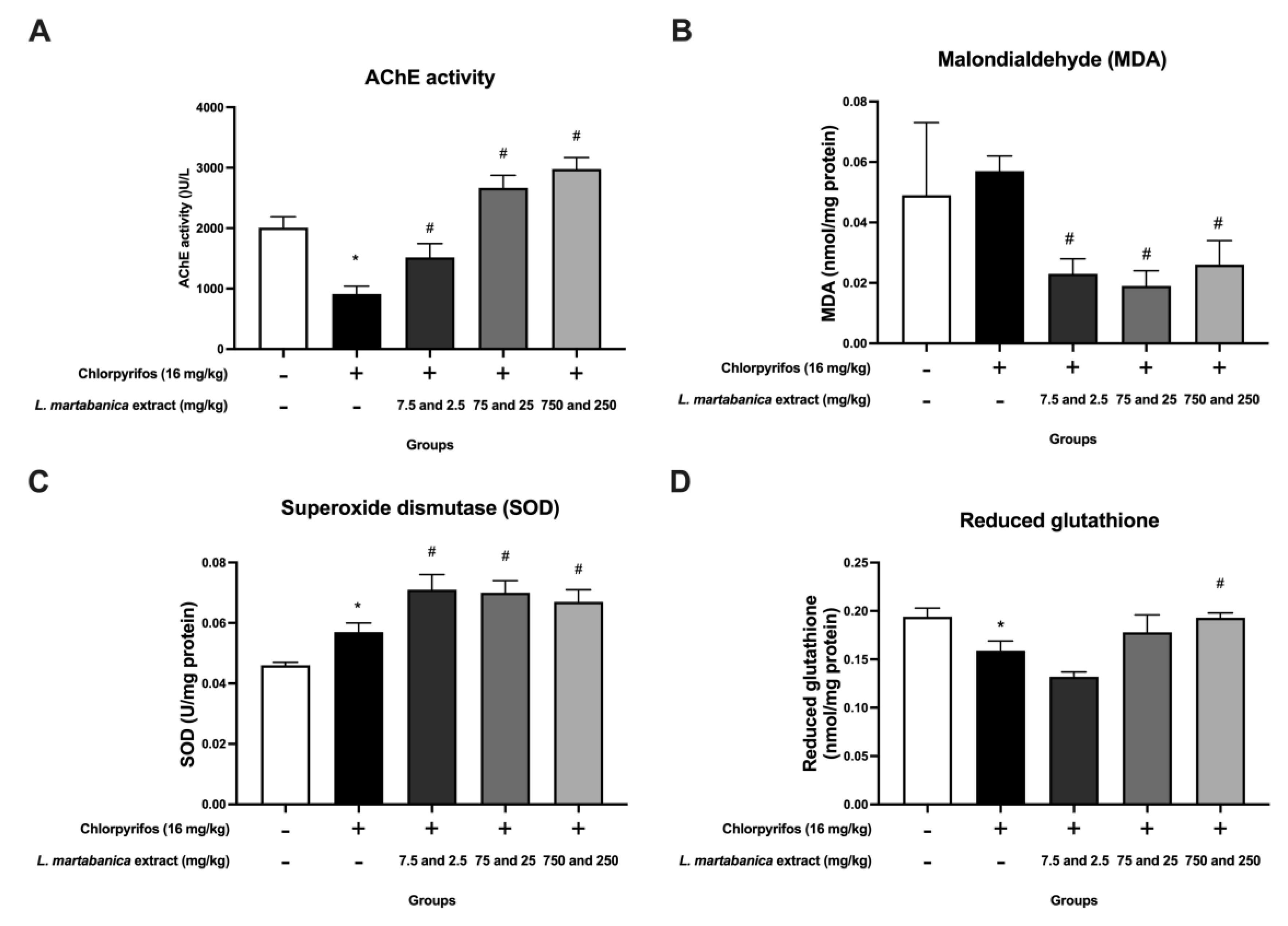

25]. In our study, the rats exposed to chlorpyrifos experienced a decrease in AChE activity. Treatment with

L. martabanica leaf water extract demonstrated promise in reversing this effect, indicating potential as an anti-pesticide agent. Additionally, organophosphate pesticides are involved in oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [

18]. In our study, chlorpyrifos increased MDA levels while decreasing reduced glutathione, but treatment with

L. martabanica leaf water extract reversed these effects. Furthermore, the

L. martabanica leaf water extract was found to elevate SOD levels. According to prior studies, the methanol leaf extract of

L. glutinosa, including neophytadiene (sesquiterpenoids), increased SOD, GSH, and GPx concentrations substantially while decreasing MDA in comparison to the control group. Furthermore, it exhibited the potential to exert hepatoprotective effects via TGF-β1 signaling pathways [

47]. Based on our study evaluating the quality of the extracts, antioxidant effects in vitro, and anti-pesticide properties in the animal study, it is plausible that the active ingredients belong to the terpenoids group.

Long-term exposure to high doses of organochloride and organophosphate pesticides commonly used in agriculture has been linked to persistent hematotoxicity and a higher incidence of aplastic anemia in humans [60,61]. Additionally, studies have demonstrated a significant decrease in hemoglobin concentration, RBC count, and hematocrit with increased exposure to chlorpyrifos [

62]. The reduction in red blood cell count could potentially be attributed to an elevated rate of erythrocyte destruction within the hematopoietic organ, erythropoiesis inhibition, hemosynthesis impairment, or osmoregulatory dysfunction [

63]. In our investigation, we observed a decrease in RBCs, hematocrit, and hemoglobin levels across all chlorpyrifos-exposed groups. Despite some decreases in values such as RBCs, hematocrit, and hemoglobin after receiving various doses of the extract, they remained within the normal range [

64,

65,

66,

67]. Interestingly, a previous study reported that chlorpyrifos triggers a rise in white blood cells [

62]. An increase in the total number of white blood cells (WBCs) caused by exposure to toxic substances, including pesticides, is a response to stress conditions [

68]. Our investigation confirmed this relationship, showing an increase in white blood cells after chlorpyrifos exposure, with specific increases observed in neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and eosinophils, although without reaching statistical significance. Exposure to

L. martabanica leaf water extract appeared to restore these white blood cell counts to normal levels, with all white blood cell parameters remaining within normal ranges [

69].

To assess the potential impact on renal and hepatic functions, we conducted thorough clinical blood chemistry assessments. The kidneys, due to their high blood perfusion, are particularly susceptible to toxic substances. Such toxins can be actively filtered by the kidneys, potentially leading to their accumulation in renal tubules, emphasizing the importance of monitoring BUN and creatinine levels as sensitive indicators of renal health [

70,

71]. Most studies have reported that chlorpyrifos increases BUN and creatinine levels [

72]. In our study, we observed a decrease in chlorpyrifos-induced BUN levels, while creatinine levels remained normal. This change does not imply abnormality from chlorpyrifos at this concentration. Despite some decreases in values such as BUN after administering the water extracts at various doses, all values remained within normal ranges [

66,

67,

70]. These findings suggest that the administration of

L. martabanica leaf water extract had no discernible effect on kidney function or increase in kidney toxicity.

Chlorpyrifos leads to hepatotoxic changes by elevating AST, ALT, and ALP levels while reducing total protein and albumin [

73,

74]. Moreover, chlorpyrifos may cause liver dysfunction due to liver membrane permeability changes [

75]. Our findings were in line with this, showing that chlorpyrifos increased AST levels but without statistical significance and significantly decreased total protein, with a trend toward decreasing albumin. Although

L. martabanica leaf water extract returned AST to normal levels, it did not impact albumin levels. For this reason,

L. martabanica leaf water extract might reduce ROS-induced cellular damage by enhancing antioxidant enzyme activity in liver tissues, thus reversing AST levels.

Serum alkaline phosphatase activity (ALP) is a valuable indicator of liver disease, especially cholestatic disease. Additionally, ALP levels can serve as an indicator of bone mineral density loss [

76]. Exposure to chlorpyrifos has been documented to affect chondrogenesis in the growth plate cartilage of long bones in chick embryos, disrupting ossification [

77]. Our research showed a reduction in ALP levels following chlorpyrifos administration compared to the normal group. However, co-administration of

L. martabanica leaf water extract with chlorpyrifos failed to normalize ALP levels. Thus, it is plausible that

L. martabanica leaf water extract does not restore normal ossification or other bone processes. Furthermore, the extract does not induce toxicity in the liver or bones, as evidenced by the ALP value remaining within the normal range.

Due to the short 16-day duration of chlorpyrifos exposure and the potentially low concentration of chlorpyrifos, it is possible that the experimental animals did not experience pathological effects on red blood cell production, kidney, or liver functions as a result. Additional long-term, high-dose chlorpyrifos exposure studies will be necessary to confirm whether chlorpyrifos has an effect on laboratory animals and whether these specific L. martabanica leaf water extracts can alleviate the condition.

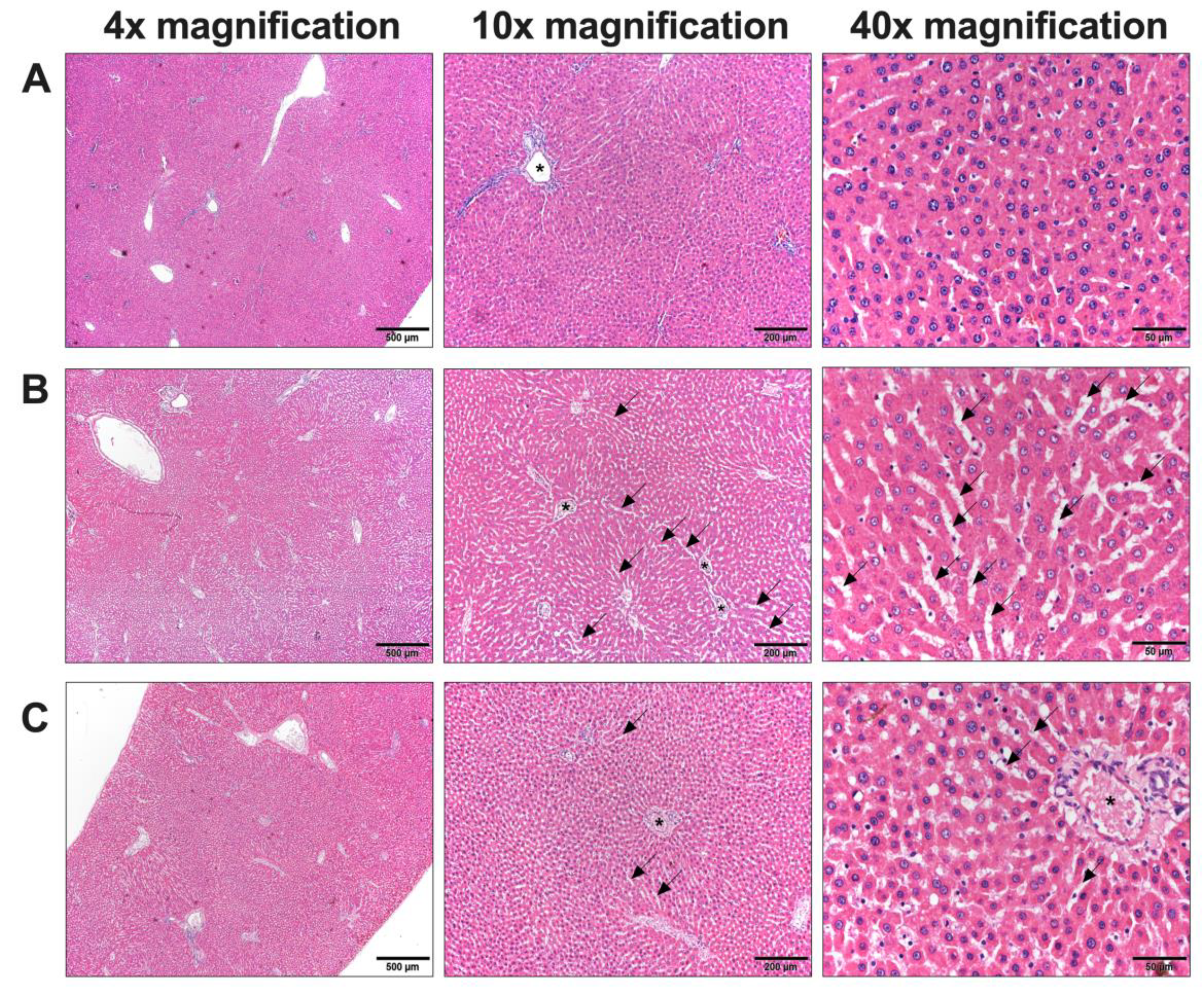

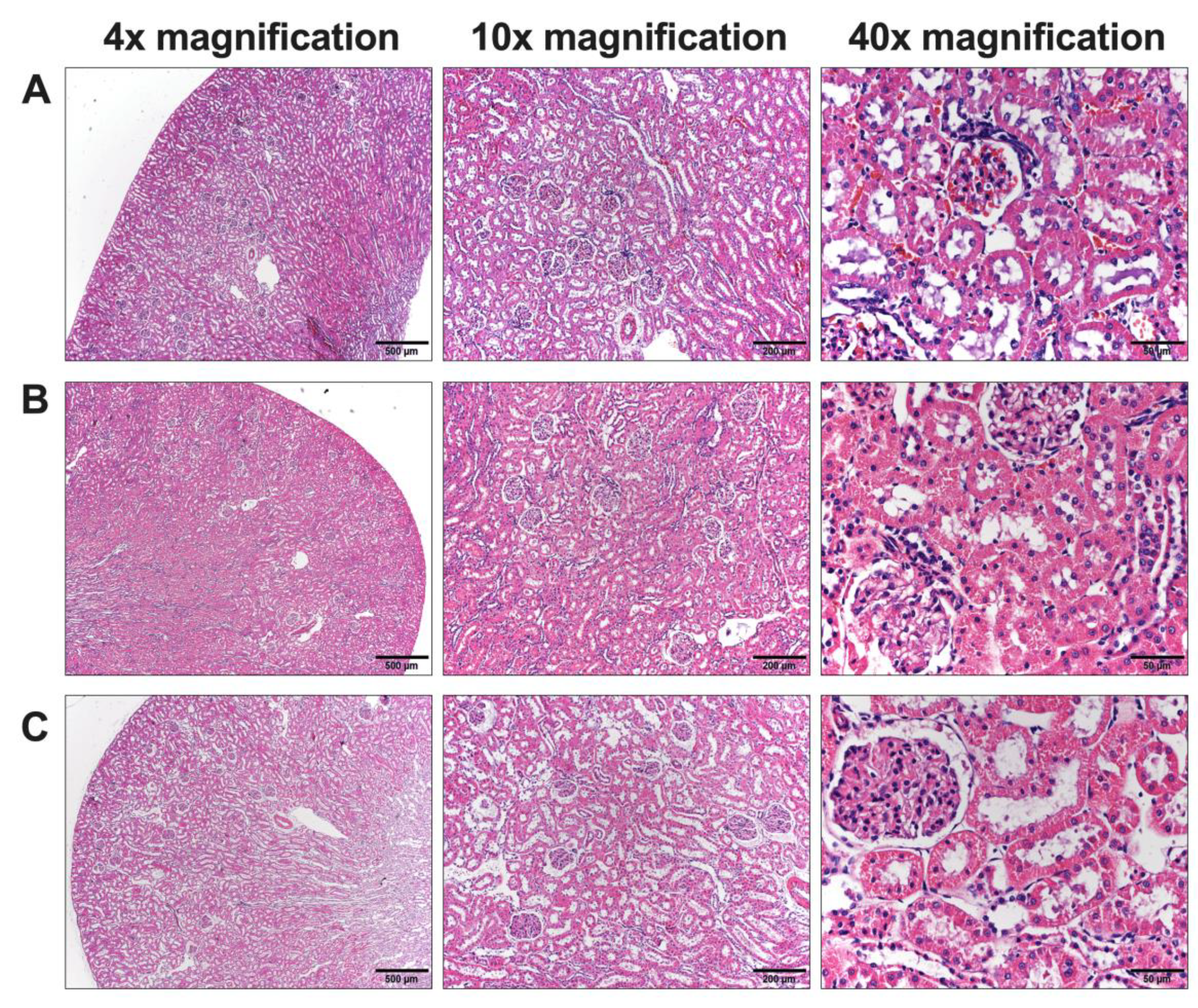

Due to the presence of abnormalities, in particular blood chemistry analyses related to kidney and liver function, it was essential to conduct a histological examination to identify potential cellular-level abnormalities in these organs. Upon examination, the kidney cells appeared normal, while abnormalities were evident in the liver cells. In our study, rats administered chlorpyrifos (control group) exhibited widened sinusoids and liver enlargement compared to the normal group. The cells displayed hyperchromatic and hypertrophied nuclei with variations in size. No dispersed cell necrosis or lymphocytic infiltration was observed. These pathology changes in liver cells could be both a regenerative and an early inflammatory process [

78]. The duration of chlorpyrifos treatment in our study was 16 days, consistent with previous studies [

79].

The administration of high concentrations of L.

martabanica water extracts led to the restoration of normal liver tissue characteristics. Regarding the pathology of the liver,

L. martabanica potentially inhibits oxidative stress by facilitating the action of antioxidants, including MDA, which restore the liver to its normal state [

80]. This is consistent with previous studies which have reported that neophytadiene, one type of sesquiterpenoids (terpenoids) was found to have protective effects [

47]. Additionally, flavonoids and phenolic substances typically have antioxidant properties that aid in the reduction of liver fibrosis [

81]. Our findings suggest that the water extracts of

L. martabanica may protect liver cells from oxidative damage caused by chlorpyrifos and improve liver function.