Submitted:

28 April 2024

Posted:

29 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; Songyang, Z.; Wan, M. Telomeres-structure, function, and regulation. Exp Cell Res. 2013, 319, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notterman, D.A.; Schneper, L. Telomere Time-Why We Should Treat Biological Age Cautiously. JAMA Netw Open. 2020, 3, e204352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, R.I.G.; DeVries, J.H.; Hess-Fischl, A.; Hirsch, I.B.; Kirkman, M.S.; Klupa, T.; Ludwig, B.; Nørgaard, K.; Pettus, J.; Renard, E.; et al. The Management of Type 1 Diabetes in Adults. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2021, 44, 2589–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garey, C.; Lynn, J.; Floreen Sabino, A.; Hughes, A.; McAuliffe-Fogarty, A. Preeclampsia and other pregnancy outcomes in nulliparous women with type 1 diabetes: a retrospective survey. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2020, 36, 982–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeoni, U.; Barker, D.J. Offspring of diabetic pregnancy: long-term outcomes. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009, 14, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stier, A.; Hsu, B.Y.; Marciau, C.; Doligez, B.; Gustafsson, L.; Bize, P.; Ruuskanen, S. Born to be young? Prenatal thyroid hormones increase early-life telomere length in wild collared flycatchers. Biol Lett. 2020, 16, 20200364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, B.M.; Knight, B.A.; Hill, A.; Hattersley, A.T.; Vaidya, B. Fetal thyroid hormone level at birth is associated with fetal growth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011, 96, E934–E938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eom, Y.S.; Wilson, J.R.; Bernet, V.J. Links between thyroid disorders and glucose homeostasis. Diabetes Metab J. 2022, 46, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddow, J.E.; Palomaki, G.E.; Allan, W.C.; Williams, J.R.; Knight, G.J.; Gagnon, J.; O’Heir, C.E.; Mitchell, M.L.; Hermos, R.J.; Waisbren, S.E.; Faix, J.D.; Klein, R.Z. Maternal thyroid deficiency during pregnancy and subsequent neuropsychological development of the child. N Engl J Med. 1999, 341, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Escobar, G.M.; Obregón, M.J.; del Rey, F.E. Maternal thyroid hormones early in pregnancy and fetal brain development. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004, 18, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, D.K.; Scharfman, H.E. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Growth Factors. 2020, 22, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briana, D.D.; Malamitsi-Puchne, R.A. Developmental origins of adult health and disease: The metabolic role of BDNF from early life to adulthood. Metabolism. 2018, 81, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzzardi, M.A.; Sanguinetti, E.; Bartoli, A.; Kemeny, A.; Panetta, D.; Salvadori, P.A.; Burchielli, S.; Iozzo, P. Elevated glycemia and brain glucose utilization predict BDNF lowering since early life. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018, 38, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasic, J.; Abramovic, I.; Vrtaric, A.; Nikolac Gabaj, N.; Kralik-Oguic, S.; Katusi Bojanac, A.; Jezek, D.; Sincic, N. Impact of Preanalytical and Analytical Methods on Cell-Free DNA Diagnostics. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021, 9, 686149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joglekar, M.V.; Satoor, S.N.; Wong, W.K.M.; Cheng, F.; Ma, R.C.W.; Hardikar, A.A. An Optimised Step-by-Step Protocol for Measuring Relative Telomere Length. Methods Protoc. 2020, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panelli, D.M; Bianco, K. Cellular aging and telomere dynamics in pregnancy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2022, 34, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daneels, L.; Martens, D.S.; Arredouani, S.; Billen, J.; Koppen, G.; Devlieger, R.; Nawrot, T.S.; Ghosh, M.; Godderis, L.; Pauwels, S. Maternal Vitamin D and Newborn Telomere Length. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martens, D.S.; Van Der Stukken, C.; Derom, C.; Thiery, E.; Bijnens, E.M.; Nawrot, T.S. Newborn telomere length predicts later life telomere length: Tracking telomere length from birth to child- and adulthood. EBioMedicine. 2021, 63, 103164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Send, T.S.; Gilles, M.; Codd, V.; Wolf, I.; Bardtke, S.; Streit, F.; Strohmaier, J.; Frank, J.; Schendel, D.; Sütterlin, M.W.; Denniff, M.; Laucht, M.; Samani, N.J.; Deuschle, M.; Rietschel, M.; Witt, S.H. Telomere Length in Newborns is Related to Maternal Stress During Pregnancy. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017, 42, 2407–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.V.; Schneider, K.M.; Teumer, A.; Rudolph, K.L.; Hartmann, D.; Rader, D.J.; Strnad, P. Association of Telomere Length with Risk of Disease and Mortality. JAMA Intern Med. 2022, 182, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dong, X.; Cao, L.; Sun, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, R.; Covasa, M.; Zhong, L. Association between telomere length and diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis. J Int Med Res. 2016, 44, 1156–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, J.A.; Temple, R.C.; Hughes, J.C.; Dozio, N.C.; Brennan, C.; Stanley, K.; Murphy, H.R.; Fowler, D.; Hughes, D.A.; Sampson, M.J. Cord blood telomere length, telomerase activity and inflammatory markers in pregnancies in women with diabetes or gestational diabetes. Diabet Med. 2010, 27, 1264–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilfillan, C.; Naidu, P.; Gunawan, F.; Hassan, F.; Tian, P.; Elwood, N. Leukocyte Telomere Length in the Neonatal Offspring of Mothers with Gestational and Pre- Gestational Diabetes. PLoS One. 2016, 11, e0163824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Jing, C.; Li, F. The Association Between Maternal Subclinical Hypothyroidism and Growth, Development, and Childhood Intelligence: A Meta-analysis. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2018, 10, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos-Moreno, M.P.; Fries, G.R.; Gubert, C.; Dos Santos, B.T.M.Q.; Fijtman, A.; Sartori, J.; Ferrari, P.F.; Rosa, A.R.; Yatham, L.N.; Kauer-Sant, A.M. Telomere Length, Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and BDNF Levels in Siblings of Patients with Bipolar Disorder: Implications for Accelerated Cellular Aging. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017, 20, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Losada, M.L.; Bouhaben, J.; Arroyo-Pardo, E.; Aparicio, A.; López-Parra, A.M. Loneliness, Depression, and Genetics in the Elderly: Prognostic Factors of a Worse Health Condition? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 19, 15456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Teng, W.; Shan, Z.; Yu, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, S.; Fan, C.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H. The effect of maternal subclinical hypothyroidism during pregnancy on brain development in rat offspring. Thyroid. 2010, 20, 909–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, M.E.; Xu, B.; Lu, B.; Hempstead, B.L. New insights in the biology of BDNF synthesis and release: implications in CNS function. J Neurosci. 2009, 41, 12764–12767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Maternal euthyroid group (ETG, n=35) Median IQR; Mean ± SD | Maternal subclinical hypothyroid group (SHG, n=35) Median IQR; Mean ± SD |

p |

| Age (years) | 31 (27-34) 30.8±5.0 |

31 (26-35) 30.1±6.1 |

0.908 0.609 |

| Duration of T1DM (y) | 15.0 (6.0-21.0) 14.8±9.5 |

14.0 (8.0-21.5) 14.1±8.0 |

0.854 0.798 |

| Less than 8 years n (%) | 11 (31.4) | 12 (34.3) | |

| More than 8 years n (%) | 24 (68.6) | 23 (65.7) | >0.9 |

| Years of onset T1DM (years) | 14.0 (9.0-25.0) 16.3±9.8 |

14.5 (9.0-23.0) 16.1±8.8 |

0.991 0.908 |

| Before 10 years n (%) | 13 (37.1) | 14 (40.0) | |

| After 10 years n (%) | 22 (62.9) | 21 (60.0) | >0.9 |

| Height (cm) | 166.6±5.7 | 165.2±4.9 | 0.610 |

| BMI before pregnancy (kg/m2) | 24.7±5.3 | 23.0±4.3 | 0.158 |

| BMI < 25 n (%) | 21 (60.0) | 26 (72.2) | |

| BMI 25–29.9 n (%) | 9 (25.7) | 5 (13.9) | |

| BMI ≥ 30 n (%) | 5 (14.3) | 5 (13.9) | 0.640 |

| Gestational weight gain (kg) |

13.6±5.2 |

12.3±3.9 |

0.158 |

| BMI at the time of CS (kg/m2) | 29.2±5.0 | 27.6±4.5 | 0.160 |

| BMI < 25 n (%) | 7 (20) | 11 (31.4) | |

| BMI 25–29.9 n (%) | 14 (40) | 16 (45.7) | |

| BMI ≥ 30 n (%) | 14 (40) | 8 (22.9) | 0.265 |

| Primiparous n (%) | 21 (60.0) | 20 (57.1) | |

| Multiparous n (%) | 14 (40.0) | 15 (42.9) | >0.9 |

| HbA1c in the first trimester (%) | 7.1±1.7 | 6.7±0.9 | 0.238 |

| HbA1c in the second trimester (%) | 6.5±1.4 | 6.2±0.8 | 0.349 |

| HbA1c in the third trimester (%) | 6.1±1.1 | 6.1±0.7 | 0.958 |

| TSH in first trimester (mIU/L) | 1.7 (1.1-2.0) | 3.2 (2.8-4.2) | <0.001 |

| FT3 in the first trimester (pmol/L) | 3.9 (3.6-4.3) | 3.6 (3.4-4.1) | 0.132 |

| FT4 in the first trimester (pmol/L) | 11.6 (11.0-12.2) | 11.7 (11.0-12.8) | 0.327 |

| BDNF in the first trimester (ng/L) | 861.8 (571.9-1152) | 736.6 (569.7-915.3) | 0.220 |

| BDNF at the time of CS (ng/L) | 613.8 (403.5-1031.0) | 586.1 (459.1-819.5) | 0.831 |

| Maternal serum glucose conc. at the time of CS (mmol/L) |

5.4 (4.3-7.0) |

5.2 (3.9-6.0) |

0.184 |

| Maternal telomere length (T/S) | 2.1±1.3 |

1.4±0.9 | 0.015 |

| Variable | Maternal euthyroid group (ETG, n=35) Median IQR; Mean ± SD | Maternal subclinical hypothyroid group (SHG, n=35) Median IQR; Mean ± SD |

p |

| Male n (%) | 15 (42.9) | 16 (45.7) | |

| Female n (%) | 20 (57.1) | 19 (54.3) | 0.500 |

| Term birth n (%) | 31 (88.6) | 32 (91.4) | |

| Preterm birth n (%) | 4 (11.4) | 3 (8.2%) | 0.500 |

| Birthweight (g) | 3456.6±624.7 | 3763.1±601.2 | 0.040 |

| Length (cm) | 48.8±2.5 | 50.1±2.3 | 0.030 |

| Ponderal index | 2.9±0.3 | 3.0±0.2 | 0.572 |

| Macrosomic newborn n (%) | 5 (14.3) | 13 (37.1) | |

| Euthrophic new-born n (%) | 30 (85.7) | 22 (62.9) | 0.029 |

| LGA n (%) | 6 (17.2) | 14 (40) | |

| AGA n (%) | 29 (82.8) | 21 (60) | 0.034 |

| Apgar index at 1 min | 9.8±0.5 | 9.9±0.4 | 0.597 |

| Apgar index at 5 min | 9.8±0.8 | 9.9±0.2 | 0.418 |

| Umbilical vein serum glucose conc. (mmol/L) | 4.4 (3.1-6.2) | 4.5 (3.2-5.3) | 0.509 |

| Umbilical vein serum C-peptide conc. | 0.75 (0.56-1.95) | 0.84 (0.51-1.55) | 0.767 |

| Umbilical vein serum BDNF conc. | 299.8 (185.7-450.4) | 303.6 (253.2-433.0) | 0.505 |

| Neonatal telomere lengths (T/S) | 2.7±1.4 | 2.0±0.9 | 0.010 |

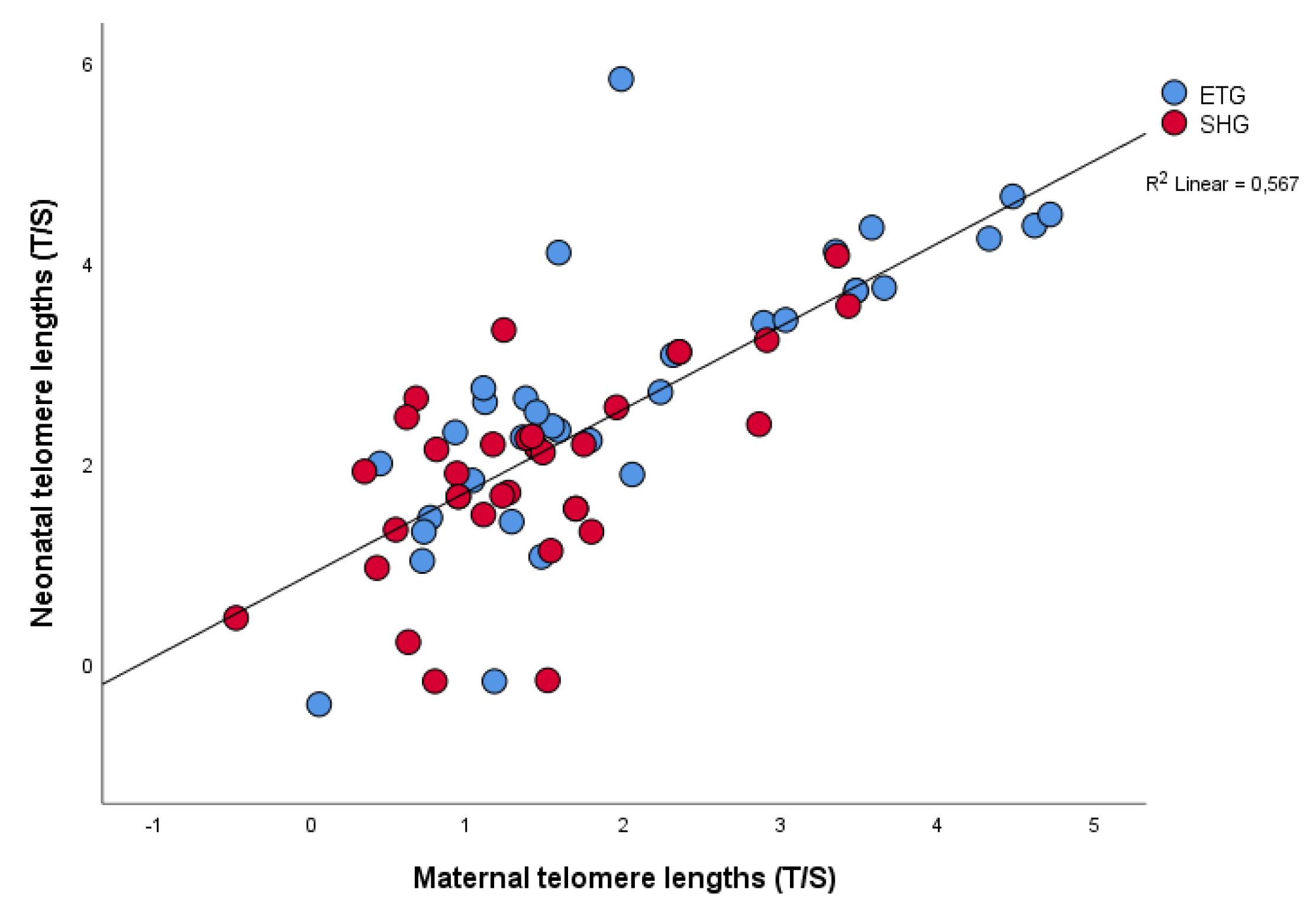

| rrho | p | |

| Maternal LTL: Neonatal LTL | 0.719 | <0.001 |

| Maternal LTL: BDNF conc. in 1 st trimester in maternal vein serum | 0.370 | 0.003 |

| Neonatal LTL: TSH in 1st trimester in maternal serum | - 0.296 | 0.018 |

| Neonatal LTL: Glucose conc. in maternal vein serum at Caesarean Section | - 0.411 | 0.006 |

| Neonatal LTL: BDNF conc. in 1st trimester in maternal vein serum | 0.510 | <0.001 |

| Neonatal LTL: C-peptide concentration in umbilical vein serum at birth | -0.275 | 0.045 |

| Maternal telomere length | Neonatal telomere length | |||

| Variable | β Coefficient (95% CI) | p | β Coefficient (95% CI) | p |

| Gestational weight gain (kg) | -0.259 (-0.122; -0.010) | 0.022 | -0.266 (-0.138; -0.009) | 0.026 |

| TSH in the first trimester (mIU/L) | -0.231 (-0.422; -0.015) | 0.036 | -0.237 (-0.493; - 0.010) | 0.041 |

| BDNF in the first trimester (ng/L) | 0.523 (0.790; 1.950) | <0.001 | 0.421 (0.536; 1.873) | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).