Introduction

Alcohol consumption is currently an alarming public health disorder. Despite its historical use dating back over 7000 years BC, in China [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46], there are no established safe levels for the consumption of this substance [

47] Alcohol consumption is associated with various conditions such as hepatic cirrhosis, hepatic fibrosis, cancer pancreatic diseases, psychiatric disorders [

48], diabetes [

1], and cardiovascular diseases [

2]. The primary damages associated with alcohol consumption are inflammatory, involving the production of chemical mediators such as interleukins (IL-6, IL-8, IL-1B, and TNF-α), TGF-β, and reactive oxygen species (ROS), causing harm to cellular components. In general, ethanol exerts a depressant effect on the central nervous system (CNS), influencing various neurotransmitter pathways and acting directly on various peripheral organs [

3] The intensity of its effects varies according to individual characteristics—such as metabolism, genetic vulnerability, lifestyle, gender, nutritional factors, and duration of consumption—as well as the quantity of substance ingested [

4].

Alcohol dependence during detoxification is associated with profound neurobiological and cognitive consequences. Volumetric analyses disclosed noteworthy reductions, reaching up to 10% in bilateral gray matter and up to 20% in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Additional, albeit less pronounced, decreases were observed in the temporal cortex, insula, and cerebellum. White matter losses, particularly in the corpus callosum, exhibited a scattered distribution. Integration of neuropsychological assessments highlighted a discernible correlation between compromised neuropsychological function and diminished gray matter volume in specific cerebral regions, including the frontal lobe, insula, hippocampus, thalamus, and cerebellum. [

5]. Concurrently, chronic alcohol consumption induced a reduction in white matter throughout the brain. These findings collectively emphasize the pervasive impact of alcohol dependence on both gray and white matter structures, providing nuanced insights into the intricate interplay between regional neuroanatomical alterations and cognitive performance [

6,

7]

Animal studies have demonstrated that chronic ethanol consumption induces mitochondrial apoptosis mediated by neuroimmune responses facilitated by cross-talk between neurons and glial cells [

8]. The Graham’s Disinhibition Hypothesis (1980) posits that alcohol influences neural regions associated with inhibition and behavioral control, impacting self-regulation, attention, information processing, and decision-making (49) This theoretical framework suggests that alcohol-induced aggressive behavior may be linked to a narrowed attentional focus, akin to the concept of alcohol myopia, where cognitive processing emphasizes only a limited aspect of the environmental scene, potentially distorting perceptual judgments.

Furthermore, instances of alcohol-related aggression frequently manifest within the context of chronic alcohol consumption and dependence. Empirical studies have estimated that up to 50% of alcohol-dependent men exhibit violent tendencies, with the prevalence varying between 16% and 50%, contingent upon factors such as age and the severity of investigated violent behaviors [

9]. Noteworthy considerations extend to self-harm and suicide [

10].

Taurine, is a potent antioxidant aminoacid and plays crucial role in neuroprotection by regulating cellular osmolarity, exhibiting antioxidant properties, modulating GABAergic neurotransmission, maintaining calcium homeostasis, and inhibiting excitotoxicity and inflammatory mediators [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Excessive extracellular glutamate can lead to cellular damage and taurine has demonstrated neuroprotective effects by reducing intracellular calcium concentration and inhibiting oxidative stress (WU et al., 2009[

13]). Due to the broad and diverse activity that taurine has demonstrated, research conducted in 2023 by Singh suggested that taurine deficiency may serve as an indicator for aging process.

Taurine’s role in neural development is highlighted by its significantly higher levels in the immature brain compared to adults, with deficiency leading to developmental deficits that can be prevented by gestational taurine supplementation [

19,

20,

21,

22]. In vitro studies with neonatal mouse cells demonstrated that taurine stimulates cell proliferation and synaptogenesis (49). Additionally, exposure to taurine increased neural precursor cells in adult mice, suggesting a role in stimulating cell proliferation through DNA replication.

Given these findings, based on the neuroprotective effects of the taurine, including antioxidant action, neuromodulation of GABAergic neurotransmission, and inhibition of excitotoxicity and inflammatory responses, collectively influence both cell proliferation and survival, we hope that taurine administration holds promise for reversing neurodegeneration inhibition induced by chronic ethanol consumption in rats.

Materials and Methods

Wistar rats weighing between 240-260 g were employed in this study. The animals were provided by the Central Animal Facility of São Paulo State University (Botucatu-SP). They were transferred to the Pharmacology Laboratory’s Animal Facility within the Department for drugs and medicines at the School of Pharmaceutical Sciences in Araraquara–UNESP, a minimum of seven days prior to the commencement of the experiments.

Throughout the study, the animals had ad libitum access to pelleted food and water, and they were subjected to a light-dark cycle of 12 hours each. The ethical considerations of this project were endorsed by the Ethics Committee on Animal Use (CEUA) at the School of Pharmaceutical Sciences in Araraquara–UNESP, under protocol CEUA/FCF/CAr 72/15.

Experimental Procedure

The animals were randomly assigned to four groups: H2O/Sal, EtOH/Sal, H2O/TAU, and EtOH/TAU. In the EtOH group, the ethanol were provided in bottles with different concentrations over a 28-day period (5 % in the 1st week, 10% in the 2nd week, and 20% in the 3rd and 4th weeks). Animals in the TAU group received daily taurine injections (i.p., 300 mg/kg, diluted in sterile 0.9% saline solution, at a volume of 1 ml/kg). Control group animals (Sal) received injections of the vehicle only (sterile 0.9% saline solution, at a volume of 1 ml/kg). Animals in the control group (H2O) were maintained with ad libitum access to water.

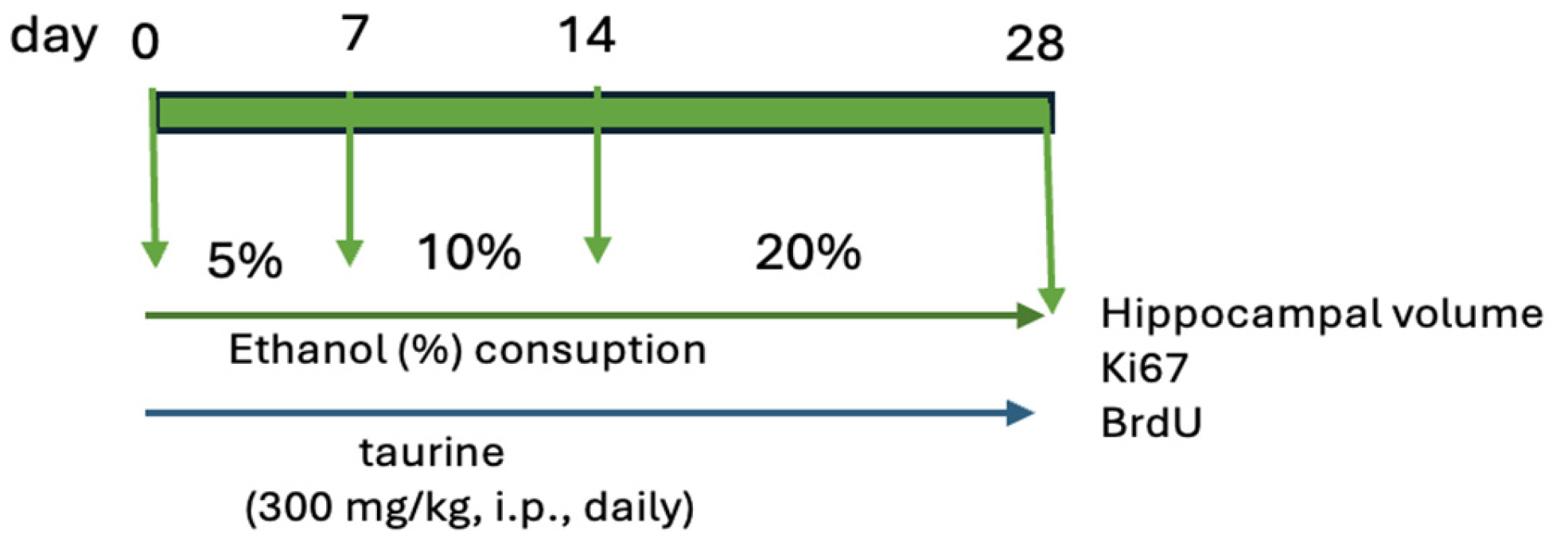

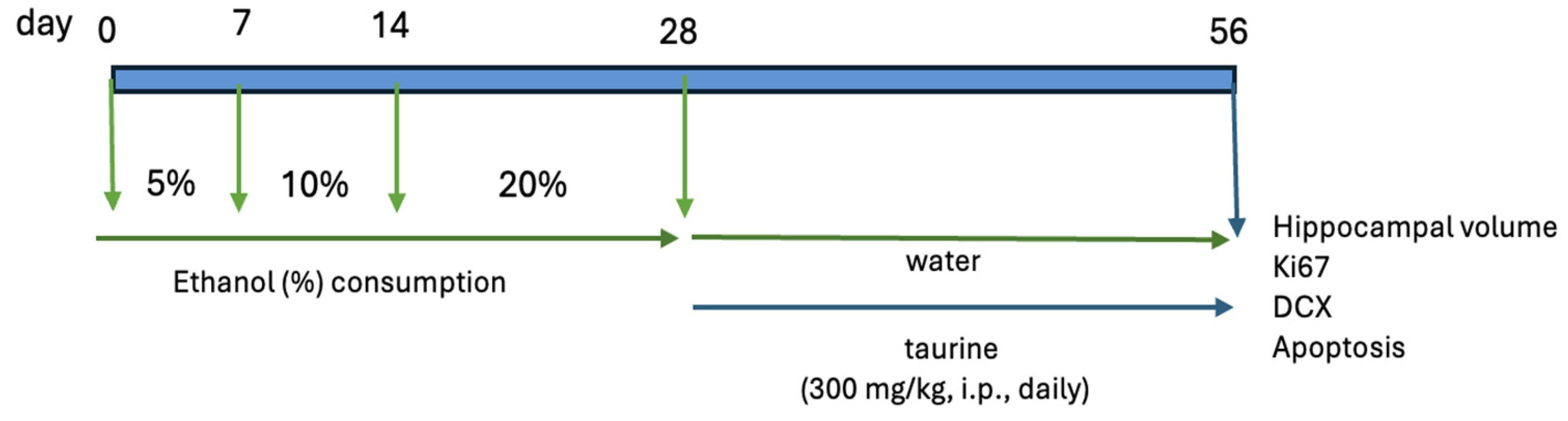

The study was bifurcated into two experiments. The first experiment examined the protective effects of taurine on hippocampal neurogenesis when submitted to the impact of ethanol consumption (

Figure 1) The second experiment investigated whether taurine administration could reverse the deleterious effects of ethanol consumption on hippocampal neurogenesis (

Figure 2)

Pyknotic Cells Analysis

A series of histological sections were stained with cresyl violet (CV) for the analysis of volume and the number of pyknotic cells (cells in the process of neural loss) [

23]. Initially, the sections were sequentially mounted on special slides (Superfrostplus Gold, Fisher Scientific, USA) and air-dried in an oven at 37°C for 8 hours. The slides were then stained with cresyl violet and coverslipped using DPX (BDH, Gallard-Schlesinger Industries Inc., CarlePlace, NY, USA) as the mounting medium.

For hippocampal volume analysis, images were captured using a digital camera attached to the microscope and analyzed using the Axio Vision program (Zeiss, Brazil). The analyzed areas were summed, multiplied by the thickness of the section (40 μm), and multiplied by the distance between sections to calculate the total volume estimate of the structure, expressed in mm³. For the quantitative analysis of pyknotic cells, only those showing a contracted body and intensely stained nuclear condensation were considered (Figure 15). The quantification results represent the average of the sum of the results found in each of the multiple sections of an animal. For statistical analysis, ANOVA and the Bonferroni multiple comparison test were used. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Immunohistochemical Analysis (BrdU, Ki-67 and DCX)

For immunohistochemical processing of Ki-67 (cell proliferation), BrdU (cell survival), and DCX (neurogenesis and cell maturation), histological sections were sequentially mounted on special slides (Superfrostplus Gold, Fisher Scientific, USA) and air-dried in an oven at 37°C for 8 hours. To unmask the antigen, slides were boiled in citric acid (0.01 M, pH 6.0) for 6 minutes and cooled to room temperature for 20 minutes. Subsequently, the sections were quickly immersed in distilled water and then washed in PBS. At this stage, slides processed for Ki-67 and DCX were incubated with primary antibodies. Slides were incubated with primary antibody against Ki-67 (mouse-derived, 1:200, Novocastra Laboratories Ltd., Newcastle, UK) in PBS containing 0.5% Tween-20 (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) for 48 hours at 4°C; or with primary antibody against DCX (rabbit-derived, 1:500, ABCam, Cambridge, MA, USA) in PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) for 48 hours at 4°C.

Slides processed for BrdU underwent additional steps. The tissue was digested in trypsin solution (0.1% in 0.1 M Tris buffer, pH 7.5, containing 0.1% CaCl2) for 8 minutes. After washing in PBS, the sections were denatured in acidic solution (2.4N HCl in PBS) for 30 minutes. After washing, the sections were incubated with primary antibody against BrdU (mouse-derived, 1:200, Novocastra Laboratories Ltd., Newcastle, UK) in PBS containing 0.5% Tween-20 (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) for 48 hours at 4°C. Following this, sections processed for Ki-67 and BrdU were again washed in PBS and incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody (horse against mouse, 1:200, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) in PBS for 120 minutes at room temperature.

Sections processed for DCX were incubated with biotinylated secondary antibodies (goat against rabbit, 1:200, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for the same duration. After washing in PBS, all sections were incubated with the avidin-biotin complex (Vectastain Elite ABC kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 90 minutes at room temperature. Sections were washed with PBS and subjected to the reaction using 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as the chromogen. The reaction was stopped with further PBS washes. Slides were counterstained with cresyl violet and coverslipped using DPX (BDH, Gallard-Schlesinger Industries Inc., Carle Place, NY, USA) as the mounting medium.

Statistical Analysis

The quantitative analysis of neurons immunoreactive to Ki-67, BrdU, and DCX was carried out in a blinded fashion using light microscopy, focusing solely on cells with clearly defined boundaries and conspicuous labeling. The analysis was conducted bilaterally across all sections spanning the entire dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. The quantification results represent the mean of the total neurons found in each of the multiple sections from an individual animal. Statistical analysis employed ANOVA and the Bonferroni multiple comparison test, with significance set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

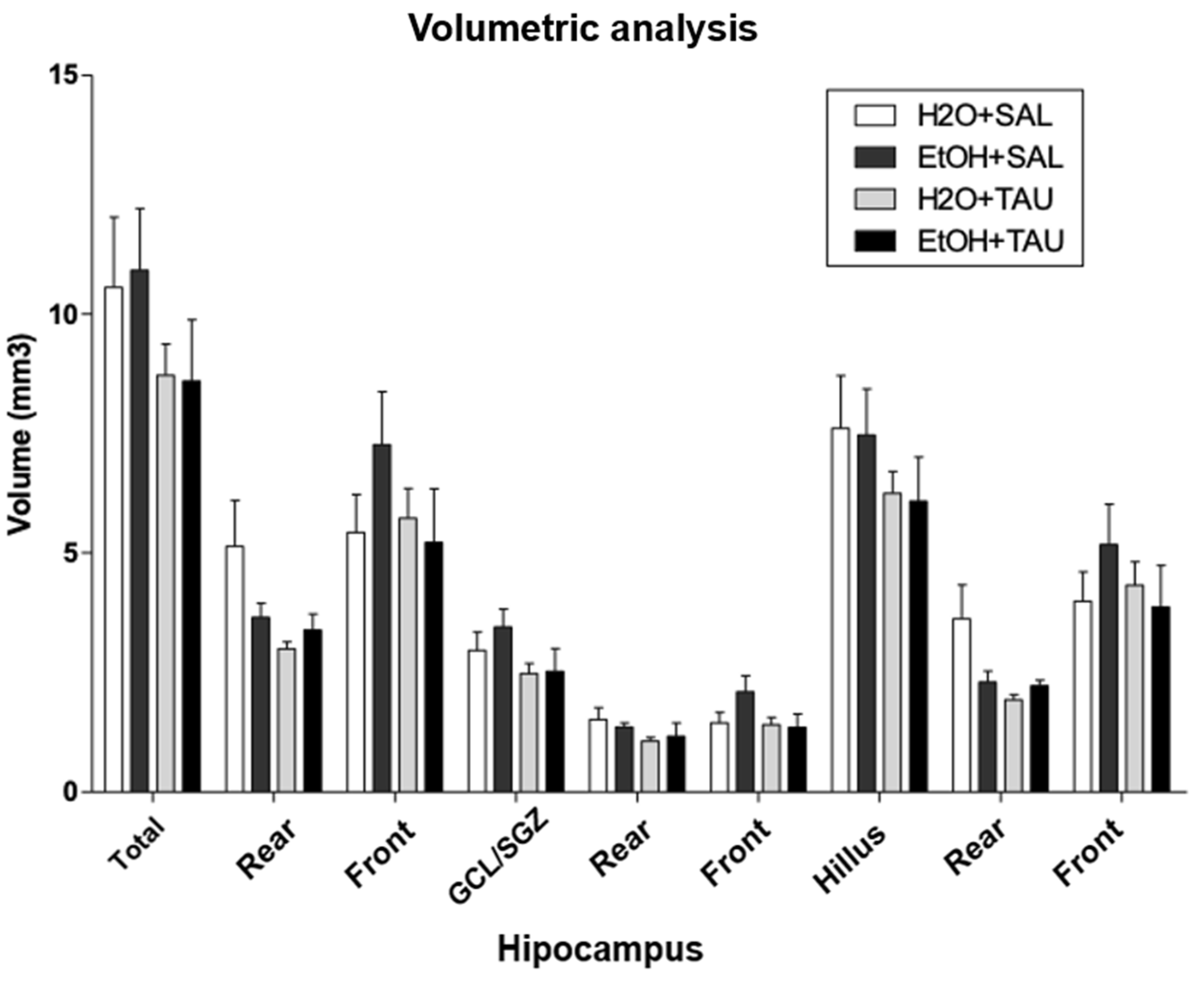

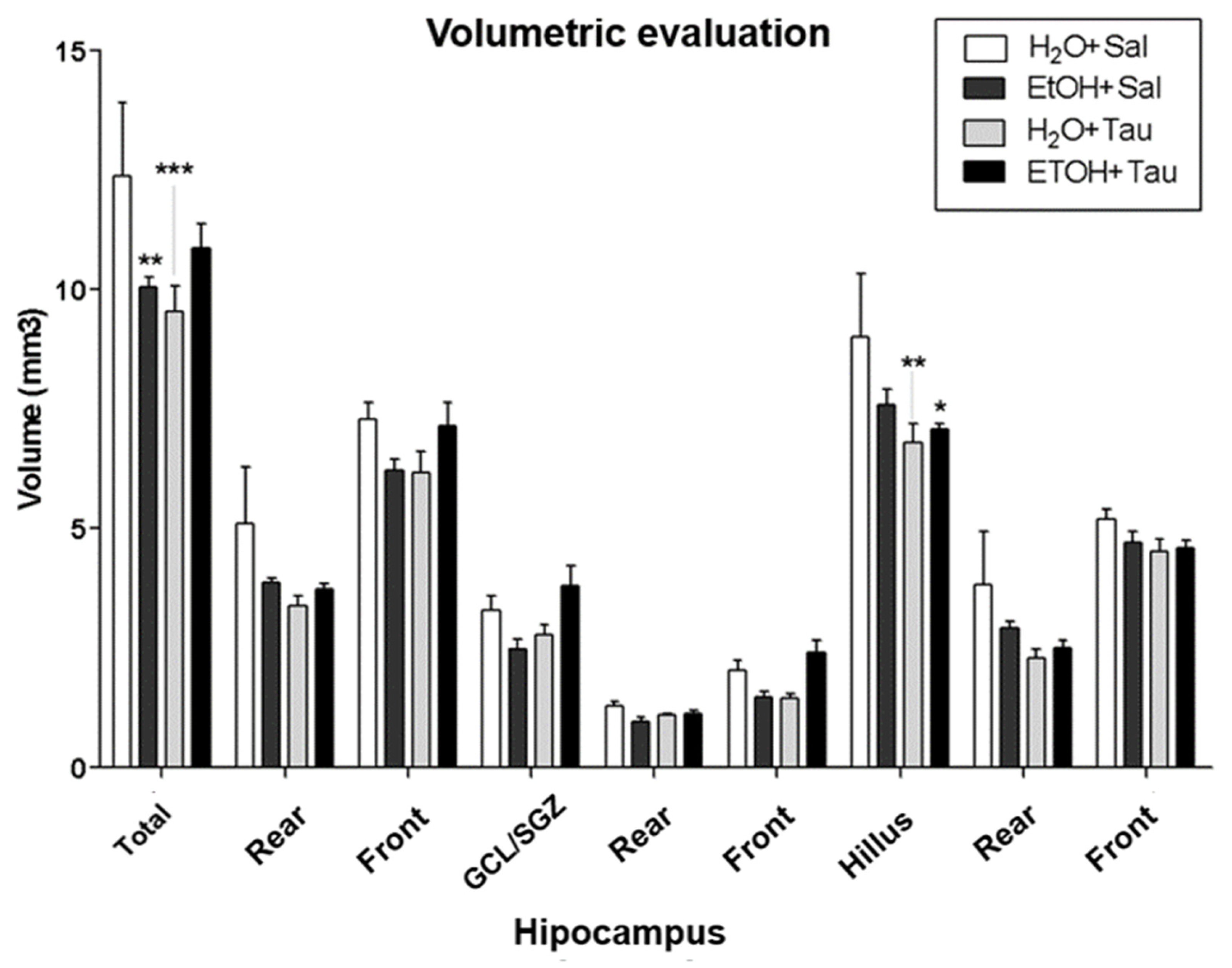

The results showed a decrease in hippocampal volume among rats exposed to chronic alcohol consumption. Volumetric assessment revealed a significant reduction in hippocampal volume across all experimental cohorts compared to the H2O/Saline (control) group (

Figure 3,

Table 1). Specifically, the EtOH/Saline group displayed an 18.8% decrease in dentate gyrus volume. The H2O/TAU group also exhibited reductions of 23.0% in the dentate gyrus and 24.7% in the hilus, while the combination of EtOH/TAU group manifested a volume decrease of 6.9%, limited to the hilus.

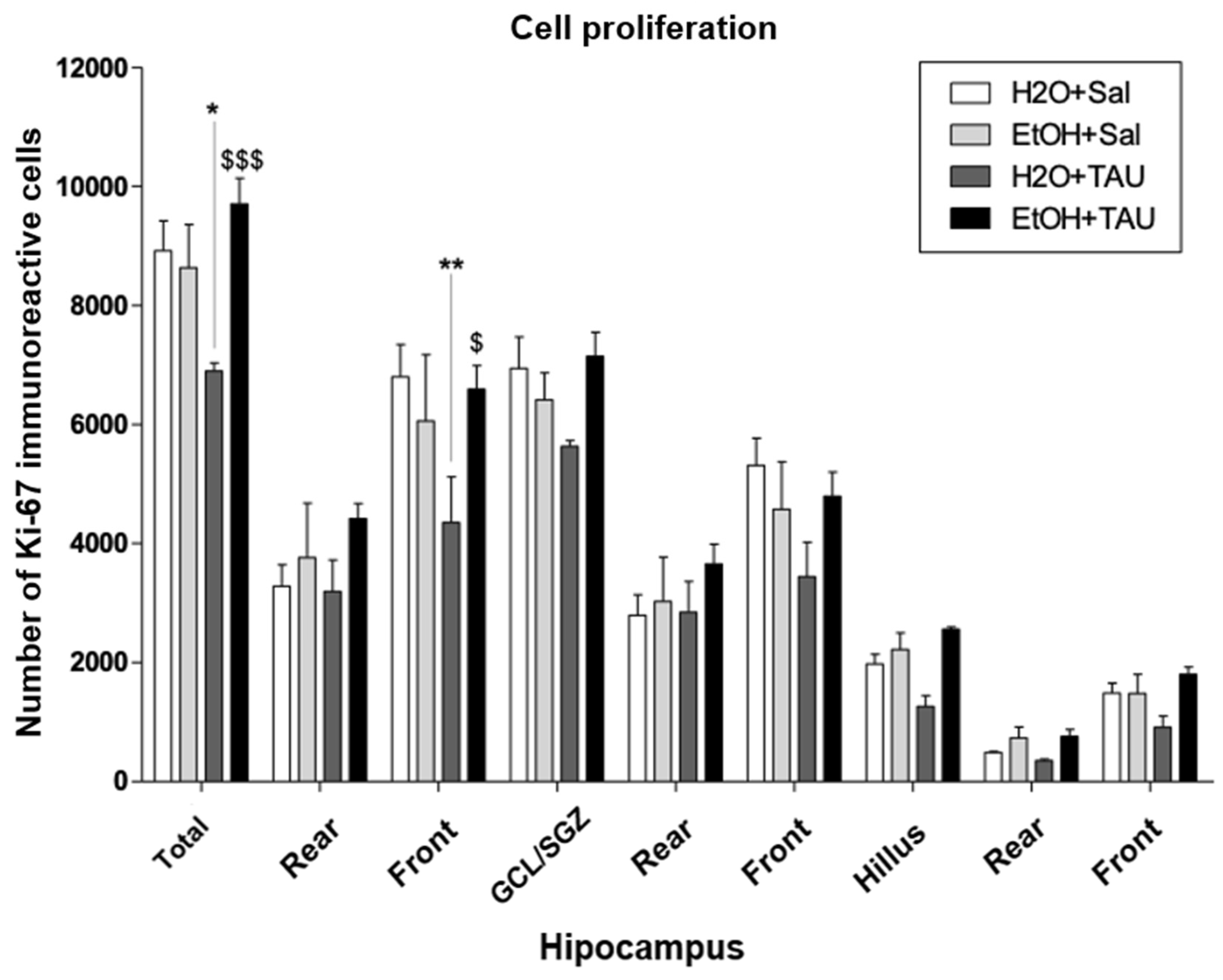

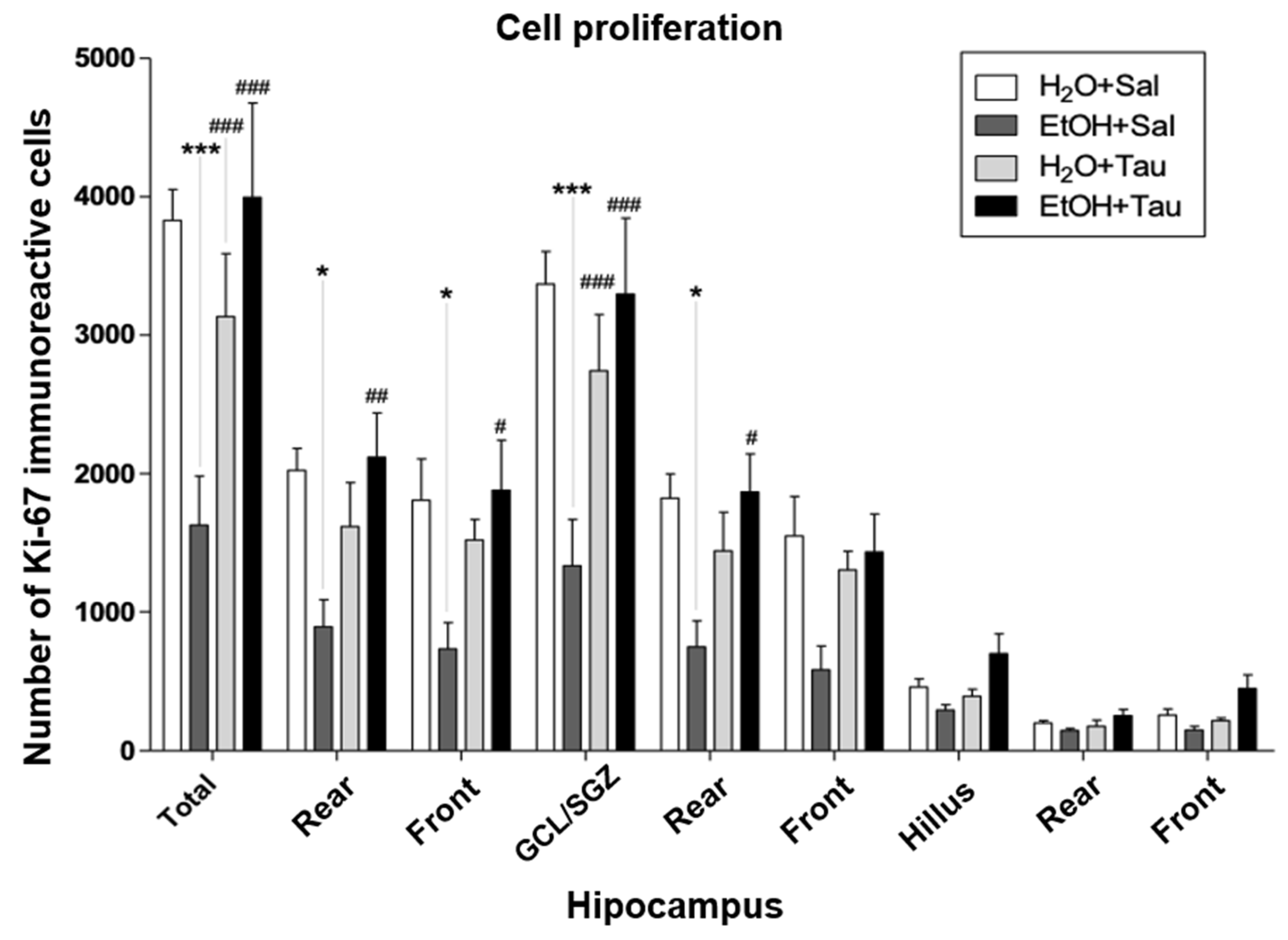

Cellular Proliferation – Ki-67

The gene encoding the Ki-67 protein (MKI67) acts as an intracellular signaling promoter of division and is overexpressed in conditions such as cancer. However, Ki-67 expression is intrinsic to life, playing a crucial role in cellular renewal and the creation of new neural networks [

24] Accordingly, a lower number of Ki-67 immunopositive cells were identified among the experimental groups, suggesting that alcohol significantly reduces the expression of proliferative stimuli in the dentate gyrus cells, with a total decrease of 57.5%. There was a reduction of 55.9% in the rear portion, 59.4% in the front, and 60.5% in the granular cell layer. The results (EtOH/TAU) demonstrated a substantial increase in the number of Ki-67 immunoreactive cells in the entire dentate gyrus (145.8%), in its rear and front portions (137.4% and 155.9%, respectively), and in the granular cell layer (147.5%) and its rear portion (149.5%).

Figure 4 and

Table 2 illustrate the pattern of Ki-67 immunoreactive cell labeling in the different experimental groups.

Figure 3 shows the image of the slices showing the pattern of labeling of Ki-67 immunoreactive cells in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus in the different experimental groups. Thus, taurine significantly promoted neuroprotection against the effects of ethanol on cellular proliferation in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, surpassing control levels.

BrdU Analysis

Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assays have been extensively employed for detecting DNA synthesis both in vivo and in vitro. The fundamental concept underlying this technique is that BrdU, when integrated as a thymidine analog into nuclear DNA, serves as a distinctive label that can be traced using antibody probes [

25], enabling the analysis of cellular survival in the dentate gyrus.

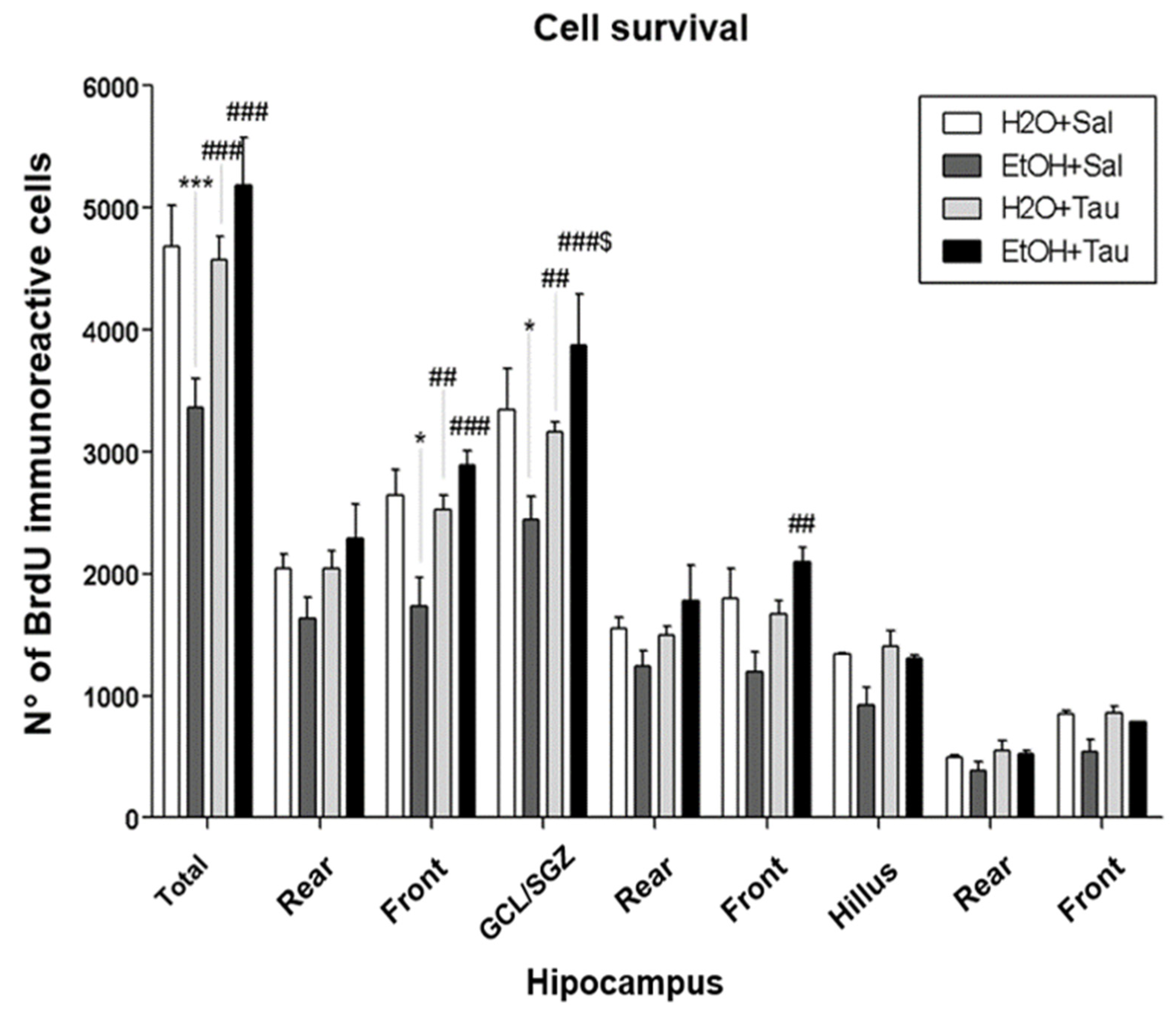

The results demonstrated that the administration of taurine significantly promoted neuroprotection against the effects of ethanol (

Figure 4 and

Table 3). The

Figure 6 show the image of the BrdU labeling pattern immunoreactive cells in the different experimental groups.

Figure 6.

Effect of taurine on hippocampal neuroprotection: BrdU number profile of immunoreactive cells in the dentate gyrus of rats submitted to the chronic ethanol consumption (n=5)* p<0,05 vs. H2O/Saline, ** p<0,01 vs. H2O/Saline, *** p<0,001 vs. H2O/Saline # p<0,05 vs. EtOH/Saline, ## p<0,01 vs EtOH/Saline, ### p<0,001 vs. EtOH/Saline $ p<0,05 vs. EtOH/TAU, $$ p<0,01 vsEtOH/TAU, $$$ p<0,001 vs. EtOH/TAU.

Figure 6.

Effect of taurine on hippocampal neuroprotection: BrdU number profile of immunoreactive cells in the dentate gyrus of rats submitted to the chronic ethanol consumption (n=5)* p<0,05 vs. H2O/Saline, ** p<0,01 vs. H2O/Saline, *** p<0,001 vs. H2O/Saline # p<0,05 vs. EtOH/Saline, ## p<0,01 vs EtOH/Saline, ### p<0,001 vs. EtOH/Saline $ p<0,05 vs. EtOH/TAU, $$ p<0,01 vsEtOH/TAU, $$$ p<0,001 vs. EtOH/TAU.

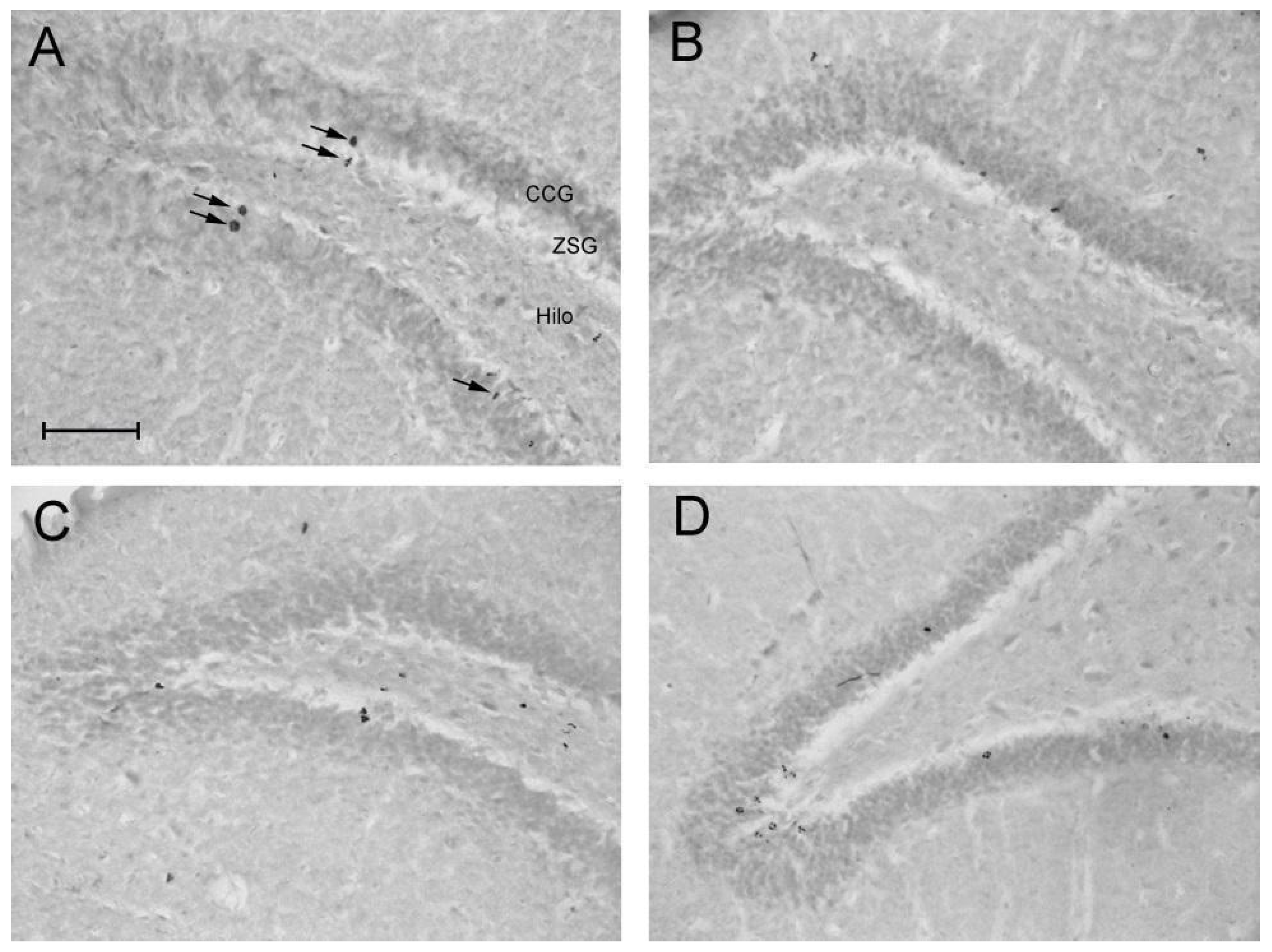

Figure 7.

Effect of taurine on hippocampal neuroprotection: Pattern of labeling with BrdU in the dentate gyrus of rats submitted to the chronic ethanol consumption. (A) - H2O/Saline group, (B) - EtOH/Saline group, (C) - H2O/TAU group, (D) - EtOH/TAU group. CCG – Granular Cell Layer, ZSG – Subgranular Zone. Arrows indicate BrdU immunoreactive cells. Calibration bar: 50µm.

Figure 7.

Effect of taurine on hippocampal neuroprotection: Pattern of labeling with BrdU in the dentate gyrus of rats submitted to the chronic ethanol consumption. (A) - H2O/Saline group, (B) - EtOH/Saline group, (C) - H2O/TAU group, (D) - EtOH/TAU group. CCG – Granular Cell Layer, ZSG – Subgranular Zone. Arrows indicate BrdU immunoreactive cells. Calibration bar: 50µm.

The EtOH/Saline group exhibited the lowest number of BrdU-immunopositive cells among the experimental groups, indicating a reduction in cell survival in the dentate gyrus of 28.2%, in the frontal portion of 34.3%, and in the Granular Cell Layer (GCL) of 27%, when compared to the control (H2O/saline). In contrast, taurine led to an increase in cell survival in the entire dentate gyrus (26.4%), its frontal portion (31.3%), and the GCL (22.9%) when associated with ethanol, in comparison to the control. The results suggested that taurine effectively mitigated the deleterious effects of ethanol. There was an observed increase in the number of BrdU-immunopositive cells in the EtOH/TAU group compared to EtOH/saline: dentate gyrus (54.0%), frontal portion (66.6%), GCL (58.9%), and frontal portion (75.1%), all exceeding values observed in the control group (H2O/saline), although not statistically significant.

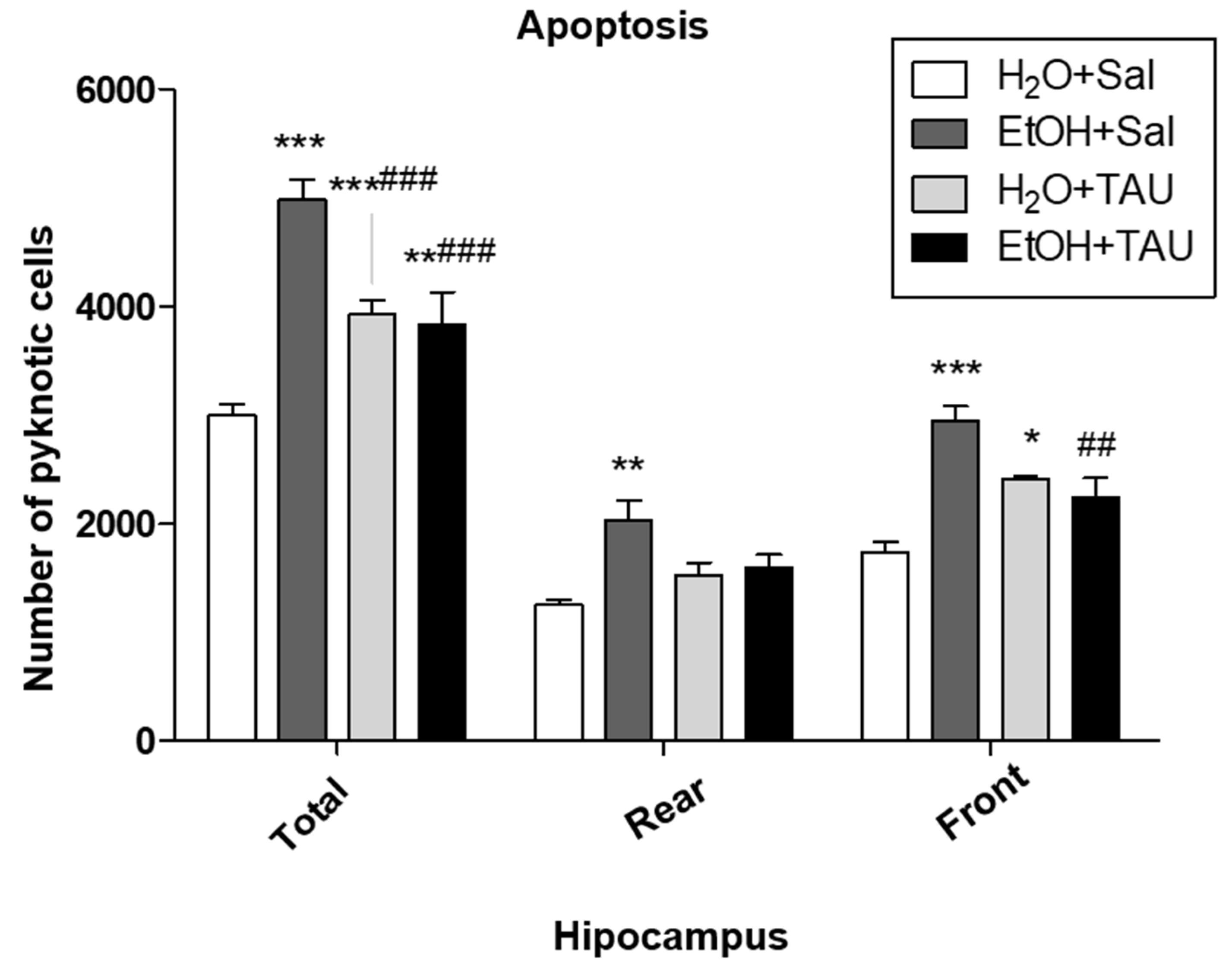

Pyknotic Cells and Apoptosis

In general, all experimental groups exhibited a significant increase in apoptosis in the dentate gyrus or its anterior and posterior divisions compared to the untreated control group. Quantitative analysis revealed a significant rise in the number of picnotic cells in the dentate gyrus (66.3%) and in its anterior and posterior portions (62.2% and 69.3%, respectively) in the EtOH+Sal group. Taurine conferred protection against ethanol-induced effects, resulting in a 38.2% reduction in picnotic cells in the dentate gyrus, a reduction comparable to that observed with taurine treatment alone (H2O + TAU).

Chronic ethanol administration also led to a significant increase in apoptosis in the granular cell layer and a decrease in hippocampal volume compared to the control group. These findings are consistent with existing literature. Chronic and excessive ethanol consumption may impair neuronal signal transduction pathways [

49].

Table 4.

Effects of taurine administration in the apoptosis on hipocampus of rats submitted to ethanol chronic consumption.

Table 4.

Effects of taurine administration in the apoptosis on hipocampus of rats submitted to ethanol chronic consumption.

| |

Groups |

| |

H2O+Sal |

EtOH+Sal |

H2O+TAU |

EtOH+TAU |

| Total |

2994±108 |

4980±196*** |

3924±135***###

|

3834±295 **###

|

| Rear |

1254±44 |

2034±181** |

1518±125 |

1590±124 |

| Front |

1740±97 |

2946±135 *** |

2406±30 * |

2244±175 ##

|

Figure 8.

Effects of taurine administration in the apoptosis on hipocampus of rats submitted to ethanol chronic consumption. * p<0,05 vs. H2O+Sal, ** p<0,01 vs. H2O+Sal, *** p<0,001 vs. H2O+Sal # p<0,05 vs. EtOH+Sal, ## p<0,01 vs. EtOH+Sal, ### p<0,001 vs. EtOH+Sal.

Figure 8.

Effects of taurine administration in the apoptosis on hipocampus of rats submitted to ethanol chronic consumption. * p<0,05 vs. H2O+Sal, ** p<0,01 vs. H2O+Sal, *** p<0,001 vs. H2O+Sal # p<0,05 vs. EtOH+Sal, ## p<0,01 vs. EtOH+Sal, ### p<0,001 vs. EtOH+Sal.

In vitro studies using rat cortical neuron cultures revealed that ethanol induced a reduction in CREB (cAMP response element binding protein) activity and decreased expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), essential for neurotransmitter synthesis and other molecules necessary for neuronal survival [

50]. These data suggest that neuronal death following ethanol exposure is related to intracellular signaling alteration caused by CREB activity suppression and decreased BDNF levels [

51].

There are few studies on the neuroprotective effects of taurine against ethanol, and to date, these studies have only analyzed the cerebellum of neonatal mice [

39,

40] demonstrated the neuroprotective action of taurine in cerebellar cells of neonatal mice subjected to acute ethanol intoxication. These studies showed a significant reduction in the number of cells immunopositive for apoptosis markers Caspase-3 and Tunel in various cerebellar regions after acute taurine administration in animals receiving subcutaneous ethanol injection. However, they also showed that taurine was unable to neuroprotect Purkinje cells in 4-day-old animals. Thus, the authors suggested that the neuroprotective effects of taurine are not linear, presenting differences depending on the neuronal type studied and the taurine concentration in the plasma. Analysis of the number of picnotic cells through cresyl violet staining can be used as an indicator of apoptosis [

52].

Effect of Taurine in the Reversion of Damages Caused by Chronic Ethanol Consumption

Hippocampal volume. The group of ethanol only, the hippocampal volume were returned to control value and no differences were observed on hippocampal volume with taurine treatment after 28 days of chronic ethanol consumption.

Figure 9.

Effect of taurine administration in the hipocampus volume in the reversion of damage in rats induced by chronic ethanol consumption. , ** p<0,01 vs. H2O/Saline, *** p<0,001 vs. H2O/Saline # p<0,05 vs. EtOH/Saline, ## p<0,01 vs EtOH/Saline, ### p<0,001 vs. EtOH/Saline $ p<0,05 vs. EtOH/TAU, $$ p<0,01 vsEtOH/TAU, $$$ p<0,001 vs. EtOH/TAU.

Figure 9.

Effect of taurine administration in the hipocampus volume in the reversion of damage in rats induced by chronic ethanol consumption. , ** p<0,01 vs. H2O/Saline, *** p<0,001 vs. H2O/Saline # p<0,05 vs. EtOH/Saline, ## p<0,01 vs EtOH/Saline, ### p<0,001 vs. EtOH/Saline $ p<0,05 vs. EtOH/TAU, $$ p<0,01 vsEtOH/TAU, $$$ p<0,001 vs. EtOH/TAU.

Table 5.

Effects of taurine administration on the hippocampal volume of rats submittedd to the chronic ethanol consumption model.

Table 5.

Effects of taurine administration on the hippocampal volume of rats submittedd to the chronic ethanol consumption model.

| |

Groups |

| Volume (mm3) |

H2O+Sal |

EtOH+Sal |

H2O+TAU |

EtOH+TAU |

| Total |

10,56060±1,46681 |

10,91056±1,30071 |

9,71863±1,14263 |

9,48331±1,37000 |

| Rear |

5,13207±0,96041 |

3,64709±0,29817 |

3,31896±0,35086 |

3,38753±0,27393 |

| Front |

5,42852±0,79271 |

7,26346±1,10776 |

6,39967±0,85093 |

6,09578±1,27249 |

| CCG/ZSG |

2,95701±0,38283 |

3,44498±0,37652 |

2,96266±0,52089 |

2,64812±0,41388 |

| Rear |

1,51283±0,25227 |

1,35442±0,09274 |

1,35019±0,29253 |

1,17730±0,23180 |

| Front |

1,44418±0,21550 |

2,09056±0,33438 |

1,61247±0,24195 |

1,47082±0,25428 |

| Hilus |

7,60359±1,10831 |

7,46558±0,96729 |

6,75597±0,64120 |

6,83519±1,06357 |

| Rear |

3,61925±0,71099 |

2,29268±0,23049 |

1,96877±0,10218 |

2,21023±0,09516 |

| Front |

3,98434±0,61746 |

5,17290±0,84616 |

4,78720±0,62665 |

4,62496±1,03964 |

Ki67. The results observed in this experiment demonstrated that after 28 days following the cessation of ethanol consumption, cellular proliferation returned to levels comparable to those of the control group animals, which received only water (Figure and Table...).

Figure 10.

Effect of taurine administration in the hipocampus cell proliferation (Ki-67) in the reversion of damage in rats induced by chronic ethanol consumption. , ** p<0,01 vs. H2O/Saline, *** p<0,001 vs. H2O/Saline # p<0,05 vs. EtOH/Saline, ## p<0,01 vs EtOH/Saline, ### p<0,001 vs. EtOH/Saline $ p<0,05 vs. EtOH/TAU, $$ p<0,01 vsEtOH/TAU, $$$ p<0,001 vs. EtOH/TAU.

Figure 10.

Effect of taurine administration in the hipocampus cell proliferation (Ki-67) in the reversion of damage in rats induced by chronic ethanol consumption. , ** p<0,01 vs. H2O/Saline, *** p<0,001 vs. H2O/Saline # p<0,05 vs. EtOH/Saline, ## p<0,01 vs EtOH/Saline, ### p<0,001 vs. EtOH/Saline $ p<0,05 vs. EtOH/TAU, $$ p<0,01 vsEtOH/TAU, $$$ p<0,001 vs. EtOH/TAU.

Table 6.

Effects of taurine administration on the number of ki-67 immunoreactive cells in the dentate gyrus of rats submitted to the chronic ethanol consumption model (n=5).

Table 6.

Effects of taurine administration on the number of ki-67 immunoreactive cells in the dentate gyrus of rats submitted to the chronic ethanol consumption model (n=5).

| |

Grupos |

| |

H2O+Sal |

EtOH+Sal |

H2O+TAU |

EtOH+TAU |

| Total |

8920±500 |

8632±729 |

6896±136 * |

9704±436 $$$

|

| Rear |

3280±361 |

3760±918 |

3192±529 |

4416±257 |

| Front |

6800±545 |

6056±1116 |

4352±769 ** |

6592±394 $

|

| CCG/ZSG |

6944±525 |

6416±448 |

5632±98 |

7144±405 |

| Rear |

2792±347 |

3024±742 |

2840±520 |

3656±331 |

| Front |

5312±455 |

4576±798 |

3440±583 |

4792±409 |

| Hillus |

1976±161 |

2216±283 |

1264±180 |

2560±32 |

| Rea |

488±16 |

736±179 |

352±29 |

760±118 |

| Front |

1488±168 |

1480±319 |

912±190 |

1800±123 |

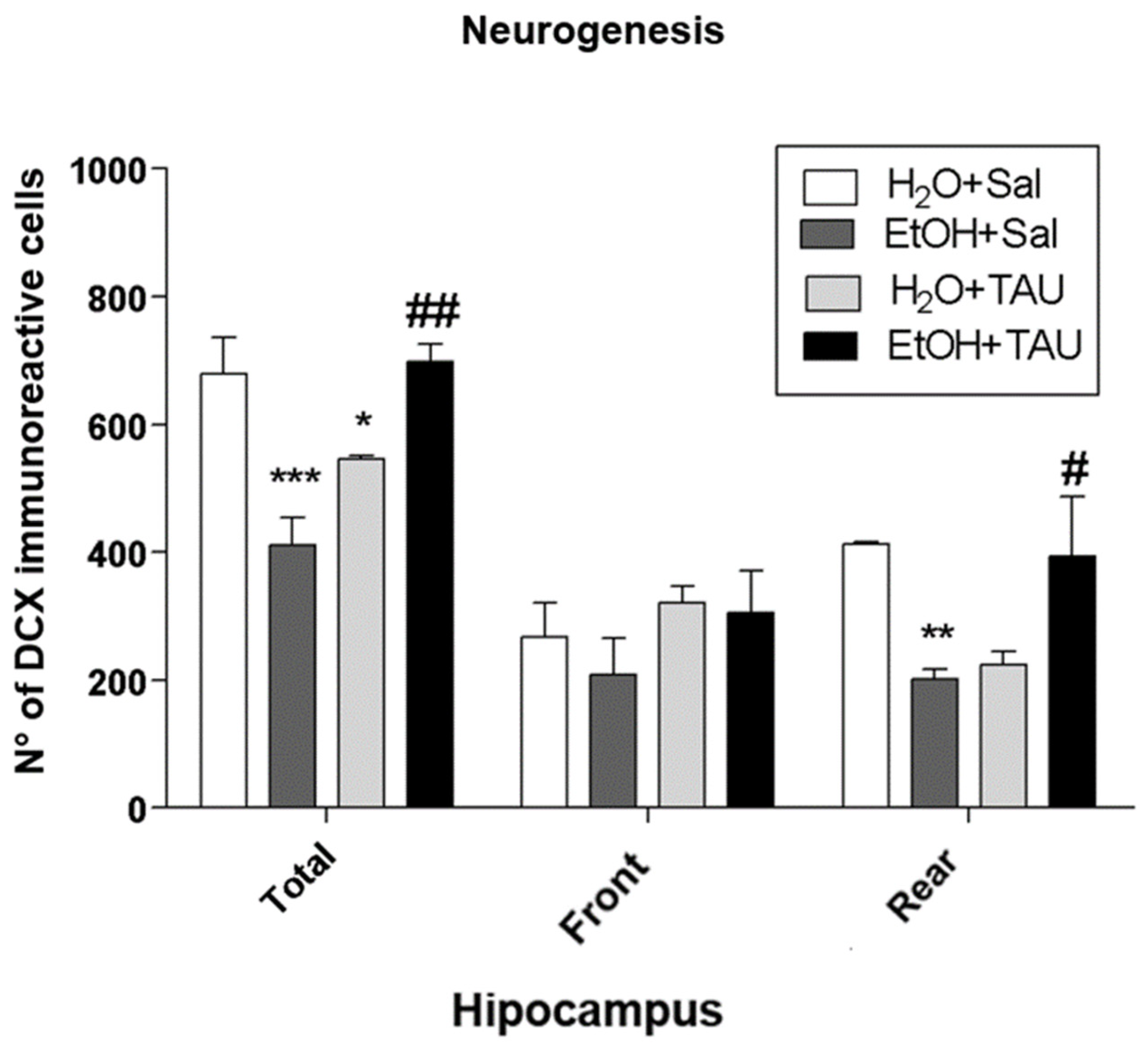

Neurogenesis

The assessment of neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus revealed that the administration of ethanol and/or taurine induced alterations in hippocampal neurogenesis The exposure to ethanol induced a significant reduction in neurogenesis. The ETOH/SAL group exhibited the lowest number of doublecortin (DCX)-immunoreactive cells among the experimental groups; when compared to water, it showed a significant decrease in neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus (39.5%) and its frontal portion (51.1%) (

Figure 11 and

Table 7).

Taurine also demonstrated neuroprotective effects against ethanol-induced neurogenesis impairment. The EtOH/TAU group showed a substantial increase in the number of DCX-immunoreactive cells in the dentate gyrus (41.3%) and frontal portion (59%) compared to the control (EtOH/saline). Taurine also significantly reduced neurogenesis in the entire dentate gyrus (19.7%) when compared to the control.

4. Discussion

The metabolism of ethanol is linked to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The ethanol conversion to acetaldehyde generates free radicals, unstable molecular species capable of causing damage to macromolecules essential for cellular homeostasis, such as lipid peroxidation, crosslinks, DNA adducts, and DNA strand breaks. Consequences particularly detrimental to the proper functioning of the brain include mitochondrial dysfunction, altered neuronal signaling, and inhibition of neurogenesis [

53].

Studies have demonstrated that in response to ethanol exposure, the rodent hippocampus undergoes two distinct periods of significant cell proliferation: the first, after two days of abstinence [

28], and the second after seven days [

27]. According to these studies, during this second period, there is a fourfold increase in cell proliferation, with survival and neuronal differentiation rates similar to those observed in the control group [

27]. These findings suggest that this complex hippocampal self-repair mechanism is responsible for neuronal repopulation in this structure.

The significant reduction in the number of Ki-67 immunoreactive cells observed in our experiments in ethanol-treated animals is supported by literature studies describing a substantial inhibitory effect of ethanol on cellular proliferation in the hippocampus [

26,

31,

32,

33], against the reports not statistically significant differences after 10 days [

34] or 6 weeks [

23] of chronic ethanol intake, suggesting that the animals’ organisms may have developed tolerance to its inhibitory effects, although its mechanisms remain unclear at present.

The neuroprotective effects of taurine and its derivatives have been extensively documented, with particular emphasis on the discovery and enhanced understanding of the Tau-T taurine receptor, which plays a pivotal role in elucidating potential mechanisms of action of this compound. Taurine has been linked to the mitigation of neuroinflammation in rat models of Alzheimer’s disease, where a notable increase in disease markers was observed. It has been identified as a partial agonist of glycine receptors, leading to the reduction of glutamatergic currents and a decrease in pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukins [

54]). In the realm of neurodegenerative disorders, taurine supplementation has shown efficacy in decreasing the secretion of inflammatory markers including TNFα, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-17 [

35], thereby reducing senescence and extending lifespan. Consequently, the downregulation of inflammatory cytokines affords protection against systemic inflammation, including shielding against neuroinflammation and synaptic loss through the deactivation of microglia-mediated inflammation and activation of the NOX2-NF-kB pathway. Administration of high doses of taurine in rat models of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) has been demonstrated to ameliorate white matter injury and neuronal damage by suppressing inflammatory mediators, glial activation, and neutrophil infiltration, while concurrently enhancing CBS expression [

36,

37]. Taurine supplementation shows promise in alleviating cognitive impairment across diverse conditions. However, excessive taurine levels in the cerebrospinal fluid can induce cognitive retardation, particularly during sensitive developmental periods. This review examines taurine’s role in various cognitive impairments and its effects on cognition in aging, Alzheimer’s disease, streptozotocin-induced brain damage [

54], ischemia, mental disorders, genetic diseases, and drug/toxin-induced cognitive deficits. Evidence suggests that taurine may enhance cognitive function through diverse mechanisms, underscoring its potential as a therapeutic agent for cognitive disorders [

38]. Taurine also exerts inhibitory effects on microglia-mediated neuroinflammation in paraquat-induced Parkinson’s disease (PD) models. In Alzheimer’s disease (AD), taurine increases the population of reactive astrocytes, thus limiting Aβ-induced inflammation. Furthermore, it exhibits promise in attenuating neurotoxic injury in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) cell line models [

55].

However, studies on the neuroprotective effects of taurine against ethanol are scarce, and so far, have been limited to the analysis of the cerebellum in neonatal mice [

39,

40]. demonstrated the neuroprotective action of taurine in cerebellar cells of neonatal mice subjected to acute ethanol intoxication. There was a significant reduction in the number of cells immunopositive for the apoptosis markers Caspase-3 and Tunel in various cerebellar regions after acute taurine administration in ethanol-intoxicated animals. However, they also found that taurine did not protect Purkinje cells in 4-day-old animals. This suggests that the neuroprotective effects of taurine are not linear, varying according to the neuronal type studied and the concentration of taurine in the plasma

The results observed in our experiment showed that after 28 days following the cessation of ethanol consumption, cell proliferation returned to the parameters of the control group animals, which received only water. This likely occurred due to the fact that after ethanol exposure, during the abstinence period, there is a natural brain recovery process, both in humans [

41] and animals [

27,

28]. Although this mechanism is not yet fully understood, it may provide important insights into this endogenous self-repair process. Studies have shown that this neuronal self-repair can be positively influenced by various factors such as physical exercise [

42] and enriched environments [

43]. Animals in the EtOH+TAU group did not show statistically significant differences when compared to animals in the H

2O+Sal and EtOH+Sal groups, suggesting that 28 days after ethanol consumption, taurine had no effect.

Chen et al., and Rivas-Aranciba et al. [

38,

44] demonstrated that taurine administration promoted cognitive improvements. Rivas-Aranciba 2000 showed that, young, adult, or elderly animals exposed to ozone, which induces significant oxidative stress could be reverted by taurine administration. The same study also showed that control animals, not exposed to ozone but receiving taurine, did not exhibit changes in cognitive tests compared to control animals receiving saline injections. Other studies have shown similar results, where taurine improved hippocampal neurogenesis after lipopolysaccharide injection [

56] or in elderly animals [

45], but did not induce changes in control groups or healthy young animals, respectively. It is known that the use of isoflurane, an anesthetic that can induce cognitive deficits, especially in elderly patients after surgery. Therefore, [

46] found that pre-treatment with taurine in elderly rats subjected to isoflurane prevented cognitive dysfunction in these animals by inhibiting apoptosis in the hippocampus. Thus, according to these data, it is likely that taurine does not stimulate neurogenesis or promote cognitive improvements in healthy adult brains but only in situations where there is already a pre-existing deficit.

According to Kim and co-workers [

57], the inflammation triggers the halogenation of taurine, via the myeloperoxidase (MPO) system in phagocytes, forming taurine chloramine (TauCl). The TauCl inhibits the production of inflammatory mediators and boosts antioxidant protein expression in macrophages. This process aids in resolving inflammation by reducing proinflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen metabolites while enhancing antioxidant defense.

In astrocytes, Seoul and co-workers [

58] demonstrated that Tau-Cl elevates nuclear translocation of nuclear factor E2-related factor (Nrf2) expression, regulating the Nrf2-controlled antioxidants enzymes such as heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1), NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), glutamate–cysteine ligase catalytic (GCLC), and glutamate–cysteine ligase modifier (GCLM) via the Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) pathway. This action rescues cells from oxidative death induced by H2O2, enhancing HO-1 expression, and suppressing ROS production in the brain, thereby promoting neuroprotection. Maybe, the same mechanism of taurine neuroprotection could occur, against alcohol hippocampus injury. New studies need to be conducted to confirm this hypothesis.

Figure 1.

Experimental protocol of taurine neuroprotection effect on chronic consumption ethanol.

Figure 1.

Experimental protocol of taurine neuroprotection effect on chronic consumption ethanol.

Figure 2.

Experimental protocol of taurine effect on neuronal damage induced by chronic ethanol consumption.

Figure 2.

Experimental protocol of taurine effect on neuronal damage induced by chronic ethanol consumption.

Figure 3.

Hippocampal volume profile after chronic ethanol ingestion and taurine (300 mg/kg, i.p) administration.

Figure 3.

Hippocampal volume profile after chronic ethanol ingestion and taurine (300 mg/kg, i.p) administration.

Figure 4.

Effect of taurine on hippocampal neuroprotection: number of Ki-67 profiles in the dentate gyrus of rats submitted to the chronic ethanol consumption (n=5). * p<0.05 vs. H2O/Sal, ** p<0.01 vs. H2O/Sal $ p<0,05 vs. H2O /TAU, $$ p<0,01 vs. H2O /TAU, $$$ p<0,001 vs. H2O /TAU.

Figure 4.

Effect of taurine on hippocampal neuroprotection: number of Ki-67 profiles in the dentate gyrus of rats submitted to the chronic ethanol consumption (n=5). * p<0.05 vs. H2O/Sal, ** p<0.01 vs. H2O/Sal $ p<0,05 vs. H2O /TAU, $$ p<0,01 vs. H2O /TAU, $$$ p<0,001 vs. H2O /TAU.

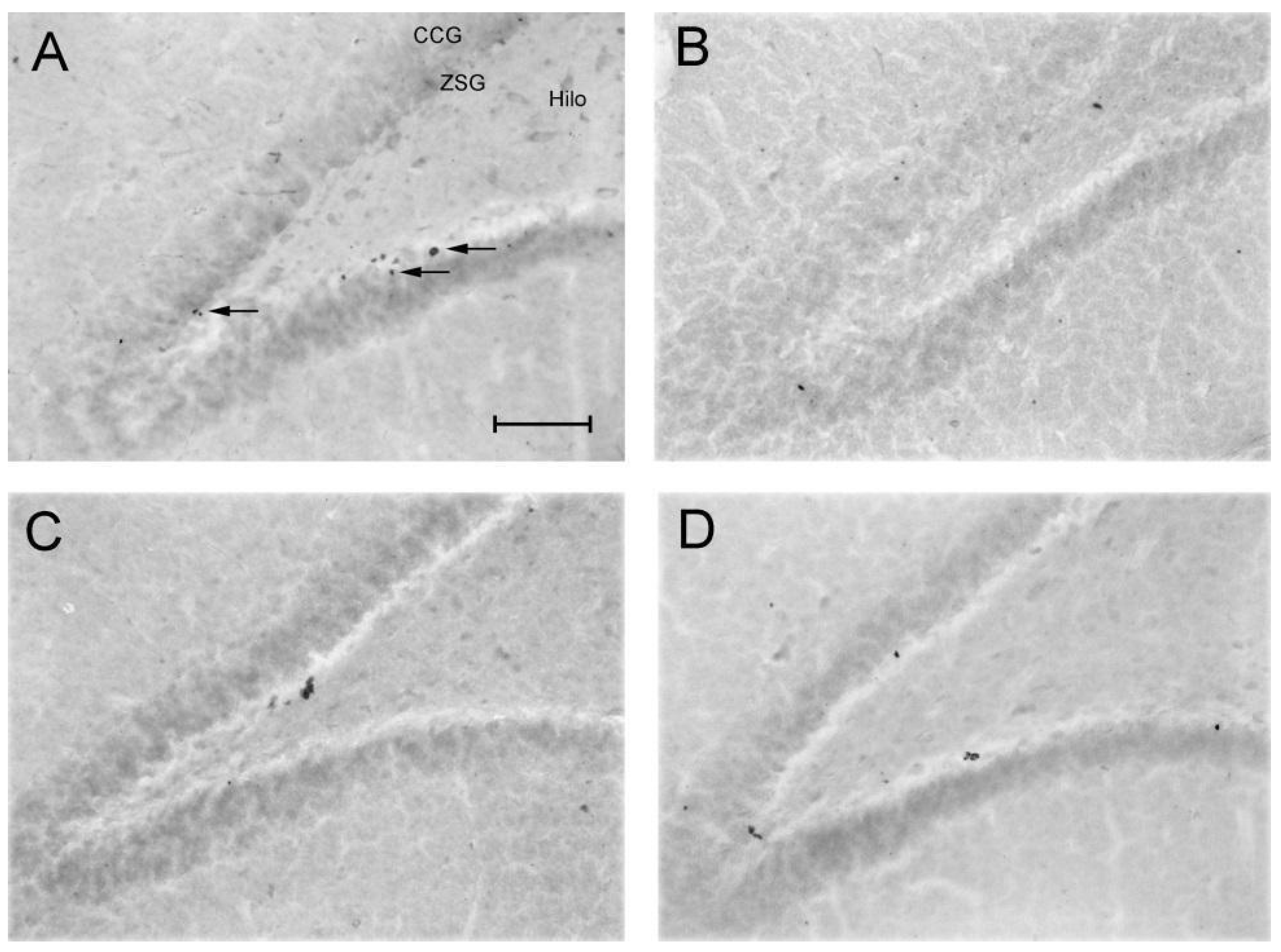

Figure 5.

Effect of taurine on hippocampal neuroprotection: Pattern of labeling of Ki-67 in the dentate gyrus of rats submitted to the chronic ethanol consumption (A) H2O/Saline group, (B) - EtOH/Saline group, (C) - H2O/TAU group, (D) - EtOH/TAU group; (CCG) Granular Cell Layer, (ZSG) – Subgranular Zone. Arrows indicate the Ki-67 immunoreactive cells. Calibration bar: 50µm.

Figure 5.

Effect of taurine on hippocampal neuroprotection: Pattern of labeling of Ki-67 in the dentate gyrus of rats submitted to the chronic ethanol consumption (A) H2O/Saline group, (B) - EtOH/Saline group, (C) - H2O/TAU group, (D) - EtOH/TAU group; (CCG) Granular Cell Layer, (ZSG) – Subgranular Zone. Arrows indicate the Ki-67 immunoreactive cells. Calibration bar: 50µm.

Figure 11.

Effect of taurine on hippocampal neurogenesis: Profile of the number of doublecortin (DCX) immunoreactive cells in the dentate gyrus of rats submitted to chronic ethanol consumption (n=5). * p<0.05 vs. H2O/Sal, ** p<0.01 vs. H2O/Sal, *** p<0.001 vs. H2O/Sal # p<0.05 vs. EtOH/Sal, ## p<0.01 vs. EtOH/Sal, ### p<0.001 vs. EtOH/Sal.

Figure 11.

Effect of taurine on hippocampal neurogenesis: Profile of the number of doublecortin (DCX) immunoreactive cells in the dentate gyrus of rats submitted to chronic ethanol consumption (n=5). * p<0.05 vs. H2O/Sal, ** p<0.01 vs. H2O/Sal, *** p<0.001 vs. H2O/Sal # p<0.05 vs. EtOH/Sal, ## p<0.01 vs. EtOH/Sal, ### p<0.001 vs. EtOH/Sal.

Table 1.

Hippocampal volume after chronic ethanol ingestion and taurine (300 mg/kg, ip) administration.

Table 1.

Hippocampal volume after chronic ethanol ingestion and taurine (300 mg/kg, ip) administration.

| |

Group |

| Volume (mm3) |

H2O/saline |

EtOH/saline |

H2O/TAU |

EtOH/TAU |

| Total |

12,36226±1,53917 |

10,04155±0,20212 ** |

9,52152±0,53921 *** |

10,84123±0,51103 |

| front |

5,08508±1,19848 |

3,84620±0,10077 |

3,35689±0,21497 |

3,71245±0,11551 |

| rear |

7,27718±0,34074 |

6,19536±0,24083 |

6,16464±0,43300 |

7,12878±0,48910 |

| CCG/ZSG |

3,27341±0,29104 |

2,46813±0,20353 |

2,75107±0,21078 |

3,78732±0,40809 |

| Rear |

1,28045±0,09668 |

0,95367±0,07898 |

1,08909±0,03094 |

1,10152±0,07934 |

| Front |

2,00947±0,20732 |

1,44919±0,12654 |

1,43784±0,08977 |

2,39427±0,25436 |

| Hilus |

8,99334±1,31628 |

7,57343±0,33789 |

6,77045±0,40031 * |

7,05391±0,12157 * |

| Rear |

3,80463±1,12453 |

2,89252±0,14875 |

2,26780±0,19631 |

2,48492±0,17100 |

| Front |

5,18870±0,19987 |

4,68090±0,24565 |

4,50266±0,27223 |

4,56899±0,16133 |

Table 2.

Effect of taurine on hippocampal neuroprotection: Number of Ki-67 in the dentate gyrus of rats submitted to the chronic ethanol consumption.

Table 2.

Effect of taurine on hippocampal neuroprotection: Number of Ki-67 in the dentate gyrus of rats submitted to the chronic ethanol consumption.

| |

Groups |

| |

H2O+Sal |

EtOH+Sal |

H2O+TAU |

EtOH+TAU |

| Total |

3828±224 |

1626±354*** |

3135±453###

|

3996±681###

|

| Rear |

2022±160 |

892±194* |

1617±317 |

2118±319##

|

| Front |

1806±300 |

734±188* |

1518±148 |

1878±364#

|

| CCG/ZSG |

3369±234 |

1332±335*** |

2742±407###

|

3297±549###

|

| Rear |

1821±176 |

748±187* |

1440±280 |

1866±275#

|

| Front |

1548±286 |

584±171 |

1302±136 |

1431±275 |

| Hillus |

459±59 |

294±37 |

393±50 |

699±142 |

| Rear |

201±17 |

144±18 |

177±45 |

252±45 |

| Front |

258±44 |

150±27 |

216±21 |

447±100 |

Table 3.

Effect of taurine on hippocampal neuroprotection: BrdU number of immunoreactive cells in the dentate gyrus of rats submitted to chronic ethanol consumption.

Table 3.

Effect of taurine on hippocampal neuroprotection: BrdU number of immunoreactive cells in the dentate gyrus of rats submitted to chronic ethanol consumption.

| |

Group |

| |

H2O/Saline |

EtOH/Saline |

H2O/TAU |

EtOH/TAU |

| Total |

4686±330 |

3363±241*** |

4569±197 ###

|

5180± 397 ###

|

| Rear |

2046±114 |

1629±174 |

2046±139 |

2292±280 |

| Front |

2640±216 |

1734±235 * |

2523±120 ##

|

2888±117 ###

|

| CCG/ZSG |

3342±342 |

2439±190 * |

3165±83 ##

|

3876±411 ###$

|

| Rear |

1548±96 |

1242±132 |

1497±75 |

1780±292 |

| Front |

1794±246 |

1197±164 |

1668±109 |

2096±122 ##

|

| Hilus |

1344±12 |

924±141 |

1404±130 |

1304±26 |

| Rear |

498±18 |

387±68 |

549±81 |

520±29 |

| Front |

846±30 |

537±108 |

855±59 |

784±4 |

Table 7.

Effect of taurine on hippocampal neurogenesis: Profile of the number of doublecortin (DCX) immunoreactive cells in the dentate gyrus of rats submitted to chronic ethanol consumption (n=5).

Table 7.

Effect of taurine on hippocampal neurogenesis: Profile of the number of doublecortin (DCX) immunoreactive cells in the dentate gyrus of rats submitted to chronic ethanol consumption (n=5).

| |

Groups |

| |

H2O/Sal |

EtOH/Sal |

H2O/TAU |

EtOH/TAU |

| Total |

679±56 |

411±43 *** |

546±7 * |

580±119 ###

|

| Rear |

267±55 |

209±56 |

321±27 |

260±59 |

| Front |

412±3 |

202±15 ** |

225±21 |

321±90 #

|