1. Introduction

Despite the simplicity of the geometry, the flow around cylindrical structures is of fundamental significance and involves complex flow mechanisms, including vortex shedding/impingement/interaction, shear layer separation/reattachment, transition from steady to unsteady state, transition from two-dimensional (2D) to three-dimensional (3D) state, fluid-structure interaction and flow-induced noise/vibration [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Abundant studies have been conducted to elucidate the flow around circular or square cylinders, due to their extensive engineering applications [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Especially, two tandem circular cylinders have attracted considerable attention in recent decades [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

The flow around two tandem circular cylinders is influenced by the Reynolds number (

Re), the spacing ratio (

L/

D, where

L is the center-to-center distance between two cylinders and

D is the cylinder diameter), the turbulence intensity of the approaching flow, the boundary condition, the blockage ratio and the cylinder aspect ratio [

16,

17,

18]. No consensus has been reached about the classification of flow patterns, being ascribed to diverse influencing factors and different classification standards. On one hand, experimental studies categorized flow pattern with the aid of various flow visualization techniques, such as surface oil-flow visualization, soap film visualization, laser-induced fluorescence and smoke-wire flow visualization [

19,

20]. On the other hand, numerical studies defined diverse flow regimes by various physical quantities, such as vorticity/velocity field,

Q-criterion,

λ2-criterion, pressure/force coefficient, Strouhal number and streamlines [

21,

22,

23].

The flow around two tandem circular cylinders with equal diameters is classified into

Single Body Flow (i.e., proximity flow, extended-body flow or overshoot flow),

Reattachment Flow,

Bi-stable Flow and

Co-shedding Flow (i.e., binary-vortex flow) [

24,

25]. Particularly, Zdravkovich [

26] found that, when 1.2 ≤

L/

D ≤ 4.0, the shear layers might reattach on the downstream cylinder in three different manners, namely alternate reattachment, quasi-steady reattachment and intermittent reattachment. Alam et al. [

27] and Alam [

28] provided four types of reattachment flow, namely the reverse-flow reattachment, the front-side reattachment, the front reattachment and the rear-side reattachment. Zhou and Alam [

12] pointed out that about 50% of previous investigations were conducted at

Re = 1×10

4~ 3.5×10

5, but approximate 20% at

Re = 1×10

3~1×10

4 and only 3% at

Re > 3.5×10

5. Rastan and Alam [

29] indicated that

Single Body Flow (SB) was absent for

Re ≥ 2×10

4, a hysteresis zone (HS) was observed within

Re = 50~500, and

Bi-Stable Flow (BS) was acquired at

Re ≥ 1000, being distinguished by spontaneous intermittent switches between the alternate reattachment flow (AR) and the co-shedding flow (CS) at a fixed

Re and

L/

D.

Only few investigations were devoted to clarifying the flow around two different-sized tandem circular cylinders. Alam and Zhou [

30] analyzed the wake of two tandem circular cylinders with

d/

D = 0.24~1.0 and

L’/

d = 5.5 at

Re = 2.72×10

4, where

d was the upstream-cylinder (UC) diameter,

D was the downstream-cylinder (DC) diameter, and

L’ was the distance from the UC center to the forward stagnation point of the DC.

Co-shedding Flow was subdivided into

Intermittent Lock-in (

d/

D ≥ 0.4) and

No Lock-in (

d/

D = 0.24). Zafar and Alam [

31] found that, when 0.3 ≤

d/

D ≤ 1.0 (

Co-shedding Flow), the DC wake featured a primary vortex street followed by a secondary vortex street, having a frequency 1.73 times smaller than the primary frequency. Shan [

32] classified

Co-shedding Flow into prime vortex shedding (PVS) mode, two-layer vortex shedding (TVS) mode and secondary vortex shedding (SVS) mode. Wang et al. [

33] categorized

Co-shedding Flow into

Lock-in (

L’/

d ≥ 3.0 at

d/

D = 1.0;

L’/

d ≥ 3.5 at

d/

D = 0.8),

Subharmonic Lock-in (

L’/

d ≥ 3.5 at

d/

D = 0.6) and

No Lock-in (

L’/

d ≥ 4.5 at

d/

D = 0.4;

L’/

d ≥ 7.0 at

d/

D = 0.2). Alam et al. [

34] investigated two tandem cylinders with

d/

D = 0.25~1.0 and

L’/

d = 5.5~20 at

Re = 0.8×10

4~2.42×10

4. Five flow regimes were identified, namely

Reattachment Flow,

Lock-in,

Intermittent Lock-in,

Subharmonic Lock-in and

No Lock-in. Mahir and Altaç [

35] observed four flow patterns, including over-shoot, symmetric-reattachment, front-side reattachment and co-shedding, for

d/

D = 0.3~2.0 and

G/

D = 0.5~4.0 at

Re = 100~200, where

G was the gap distance. Gao et al. [

36] displayed that, for

d/

D = 2/3 and

L/

D = 1.8~3.8 at

Re = 200, the flow was characterized by a bi-stability phenomenon, and co-shedding might occur depending on the initial perturbation.

Special attention should be paid to the spanwise periodicity of the flow field between two tandem circular cylinders. Papaioannou et al. [

37] disclosed that the case of

d/

D = 1.0 and

L/

D = 2.0 at

Re = 500 belonged to

Reattachment Flow, and obvious spanwise periodicity was observed for both the gap region and the DC downstream in terms of the instantaneous vorticity field. Hu et al. [

38] showed that, for

d/

D = 1 and

L/

D = 1.5~2.5 at

Re = 2.8×10

5~7.0×10

5, whether for

Reattachment Flow (

L/

D = 1.5) or for

Co-shedding Flow (

L/

D = 2.5), both the instantaneous velocity contours at different

Z planes and the instantaneous vorticity contours in the

Y = 0 plane demonstrated the evident spanwise periodicity. Deng et al. [

39] examined the spatial evolution of vortices in the wake of two tandem circular cylinders with

d/

D = 1 and

L/

D = 1.5~8.0 at

Re = 220, and verified the existence of the spanwise periodicity in terms of both instantaneous streamlines and instantaneous vorticity contours.

This study is dedicated to systematically analyzing the spanwise periodicity of time-averaged flow structures within the gap, and further defining different flow regimes for the flow around two tandem circular cylinders with a diameter ratio of d/D = 0.6 at Re = 3900. Seventeen spacing ratios (i.e., L/D = 1.00, 1.10, 1.15, 1.20, 1.25, 1.50, 2.00, 2.25, 2.50, 3.00, 3.15, 3.24, 3.30, 3.50, 4.00, 5.00 and 6.00) are considered in an effort to adequately capture various flow regimes and detailedly illustrate the transition process among them. Flow properties and statistical parameters are presented for each flow regime, such as velocity contours, vorticity contours, force coefficient, reattachment/separation angle, Strouhal number, wavelet scalogram, Q-criterion iso-surface and the spanwise periodicity length.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Governing Equation

This study solves the turbulence by using the large eddy simulation (LES) technique. The filtered incompressible continuity and momentum equations can be written as [

40]:

where

(

i = 1, 2 and 3) are the filtered velocity components in the streamwise (

X axis), transverse (

Y axis) and spanwise directions (

Z axis) respectively,

represents the filtered pressure field,

ρ is the density,

ν signifies the kinematic viscosity,

t symbolizes the time, and

τij denotes the subgrid scale stress tensor to be modeled.

where

is the resolved strain rate tensor and

is the subgrid-scale (SGS) eddy viscosity, which is calculated through the dynamic one equation eddy-viscosity model.

where

is the grid filter size, and the SGS kinetic energy

is obtained by solving its transport equation. The simple filtering method is employed here, and the maxDeltaRatio coefficient is set as 1.1. For the two model constants, the officially recommended values of

Ck = 0.094 and

Cε = 1.048 are utilized in this study [

41].

2.2. Boundary Condition

Four kinds of boundary conditions are involved in this study:

(1) Inlet: A fixed uniform velocity is prescribed ( = 1 m/s, = = 0 m/s), and the zero-gradient condition is applied for the pressure field ( = 0). The turbulent intensity is set as I = 0.5%, and therefore the turbulent kinetic energy is fixed as k = 3.75×10-5 m2/s2.

(2) Outlet: For the velocity field, the convective outflow boundary condition is adopted [

42,

43]:

, where

denotes all the three velocity components, and

uc is the convective velocity at the outlet. For the pressure field, the homogeneous Dirichlet condition (

= 0 Pa) is exerted at the outlet. For the turbulent kinetic energy, the zero-gradient condition (

= 0) is used.

(3) Cylinder surfaces: No-slip impermeable boundary condition is prescribed for the velocity field ( = = = 0 m/s), the zero-gradient condition is employed for the pressure field ( = 0), and the kLowReWallFunction is adopted for the turbulent kinetic energy.

(4) Top, bottom, front and back boundaries: The symmetric boundary condition is utilized, which means that the normal gradient of all variables is equal to zero (i.e., = = = = = 0).

2.3. Numerical Scheme

The Pressure Implicit with Splitting of Operators (PISO) algorithm is employed to deal with the pressure-velocity decoupling, the MUSCL scheme is chosen to discretize the convection term, the Gauss linear scheme is employed to discretize both the diffusion term and the pressure gradient term, and the Euler implicit scheme is adopted for the temporal discretization. For details of these numerical algorithms, readers can refer to the references [

44,

45]. The preconditioned conjugate gradient (PCG) method, combined with the diagonal incomplete Cholesky (DIC) preconditioner, is applied to solve the pressure matrix up to an accuracy of 10

-6 at each time step. The preconditioned biconjugate gradient (PBCG) method, combined with the diagonal incomplete LU (DILU) preconditioner, is used to solve the velocity/scalar matrix up to an accuracy of 10

-7 at each time step.

2.4. Validation Case

In order to validate the accuracy of the present numerical model, the flow field around a single cylinder at

Re = 3900 is simulated and compared with the results reported in the literature. The circular cylinder, with a diameter of

D = 1m and a height of

H = 4

D, is vertically mounted between the top and bottom planes (

Figure 1(a)). The (streamwise) length, (transverse) width and (spanwise) height of the computational domain are

L = 30

D,

B = 20

D and

H = 4

D, respectively. The junction section between the cylinder and the bottom plane is centered at the origin of the Cartesian coordinate system, the inlet plane is located at 10

D upstream of the cylinder, and the outlet plane is situated at 20

D downstream of the cylinder.

Table 1 manifests that the validation case consists of 5.74 million grid points, being clustered near the cylinder surface. The node number along the cylinder circumference (

NC) is set as 280, and the near-wall grid size

δ (i.e., the distance between the first-cell centroid and the cylinder surface) is equal to 0.002

D, ensuring that the non-dimensional wall distance (

) is less than 1.0. Besides,

NLu is the node number along

Lu (the distance between the inlet plane and the UC center),

NLd is the node number along

Ld (the distance between the DC center and the outlet plane), and

NZ denotes the node number along

H (the spanwise height). A grid independence study was performed to guarantee sufficient grid resolution, however only the details of the employed medium mesh are presented here for brevity. In addition, the time step value (∆

t) is fixed at 0.002 s, which can guarantee that the maximum Courant-Friedrichs-Lewy (CFL) number is around 0.5.

When it comes to the spanwise-averaged time-averaged pressure coefficient (

) along the cylinder surface, the normalized spanwise-averaged time-averaged streamwise velocity (

) along the

Y = 0 line in the wake, and the values of

and

(the normalized spanwise-averaged fluctuating streamwise velocity) at three cross-sections (i.e.,

X/

D = 1.06, 1.54 and 2.02),

Figure 1(b, c) and

Figure 2 demonstrate that the present numerical results overall agree well with the results reported by Zhou et al. [

40], Lourenco and Shih [

46], Norberg [

47], Ma et al. [

48], Kravchenko and Moin [

49] and Parnaudeau et al. [

50]. Furthermore,

Table 2 proves that the present numerical results are also consistent with the previous experimental or numerical data, in terms of several important statistical parameters (including

St,

,

, −

,

,

Lr/

D and

).

Table 1.

Computational grid characteristics of both the validation case and the seventeen research cases.

Table 1.

Computational grid characteristics of both the validation case and the seventeen research cases.

| Case |

Computational domain |

Time step ∆t (s) |

δ/D

|

NC |

NLu |

NL |

NLd |

NZ |

Total node number (✕106) |

| Single Cylinder |

30.00D × 20D × 4D

|

0.0020 |

0.002 |

280 |

113 |

/ |

230 |

61 |

5.74 |

|

L/D = 1.00 |

31.00D × 20D × 8D

|

0.0015 |

0.002 |

280 |

134 |

98 |

230 |

121 |

15.45 |

|

L/D = 1.10 |

31.10D × 20D × 8D

|

0.0015 |

0.002 |

280 |

134 |

106 |

230 |

121 |

17.16 |

|

L/D = 1.15 |

31.15D × 20D × 8D

|

0.0015 |

0.002 |

280 |

134 |

106 |

230 |

121 |

17.16 |

|

L/D = 1.20 |

31.20D × 20D × 8D

|

0.0015 |

0.002 |

280 |

134 |

112 |

230 |

121 |

17.45 |

|

L/D = 1.25 |

31.25D × 20D × 8D

|

0.0015 |

0.002 |

280 |

134 |

112 |

230 |

121 |

17.45 |

|

L/D = 1.50 |

31.50D × 20D × 8D

|

0.0015 |

0.002 |

280 |

136 |

131 |

230 |

121 |

17.49 |

|

L/D = 2.00 |

32.00D × 20D × 8D

|

0.0015 |

0.002 |

280 |

113 |

186 |

230 |

121 |

16.03 |

|

L/D = 2.25 |

32.25D × 20D × 8D

|

0.0015 |

0.002 |

280 |

113 |

208 |

230 |

121 |

16.69 |

|

L/D = 2.50 |

32.50D × 20D × 8D

|

0.0015 |

0.002 |

280 |

113 |

217 |

230 |

121 |

16.93 |

|

L/D = 3.00 |

33.00D × 20D × 4D

|

0.0015 |

0.002 |

280 |

113 |

237 |

230 |

61 |

8.81 |

|

L/D = 3.15 |

33.15D × 20D × 4D

|

0.0015 |

0.002 |

280 |

113 |

244 |

230 |

61 |

8.90 |

|

L/D = 3.24 |

33.24D × 20D × 4D

|

0.0015 |

0.002 |

280 |

113 |

248 |

230 |

61 |

8.96 |

|

L/D = 3.30 |

33.30D × 20D × 4D

|

0.0015 |

0.002 |

280 |

113 |

249 |

230 |

61 |

8.97 |

|

L/D = 3.50 |

33.50D × 20D × 4D

|

0.0015 |

0.002 |

280 |

113 |

255 |

230 |

61 |

9.05 |

|

L/D = 4.00 |

34.00D × 20D × 4D |

0.0015 |

0.002 |

280 |

113 |

272 |

230 |

61 |

9.28 |

|

L/D = 5.00 |

35.00D × 20D × 4D

|

0.0015 |

0.002 |

280 |

113 |

307 |

230 |

61 |

9.75 |

|

L/D = 6.00 |

36.00D × 20D × 4D

|

0.0015 |

0.002 |

280 |

113 |

342 |

230 |

61 |

10.23 |

Table 2.

Comparison of the Strouhal number based on the instantaneous lift coefficient (St), the spanwise-averaged time-averaged drag coefficient (), the spanwise-averaged fluctuating lift coefficient (), the spanwise-averaged time-averaged base pressure coefficient (−), the normalized spanwise-averaged time-averaged recirculation length (Lr/D), the spanwise-averaged time-averaged separation angle () and the normalized spanwise-averaged time-averaged minimum streamwise velocity along the Y = 0 line () for the validation case.

Table 2.

Comparison of the Strouhal number based on the instantaneous lift coefficient (St), the spanwise-averaged time-averaged drag coefficient (), the spanwise-averaged fluctuating lift coefficient (), the spanwise-averaged time-averaged base pressure coefficient (−), the normalized spanwise-averaged time-averaged recirculation length (Lr/D), the spanwise-averaged time-averaged separation angle () and the normalized spanwise-averaged time-averaged minimum streamwise velocity along the Y = 0 line () for the validation case.

| Case |

Re |

St |

|

|

|

Lr/D

|

|

|

| Present (LES) |

3900 |

0.210 |

1.030 |

0.170 |

0.917 |

1.374 |

87.25° |

-0.299 |

| Zhou et al. [40] (LES) |

3900 |

0.217 |

1.000 |

/ |

0.890 |

1.550 |

/ |

/ |

| Tian and Xiao [41] (LES) |

3900 |

/ |

1.040 |

0.170 |

0.890 |

1.400 |

87.0° |

/ |

| Kravchenko and Moin [49] (LES) |

3900 |

0.210 |

1.040 |

/ |

0.940 |

1.350 |

88.0° |

-0.370 |

| Parnaudeau et al. [50] (Expt.) |

3900 |

0.208 |

/ |

/ |

/ |

1.510 |

/ |

-0.340 |

| Meyer et al. [51] (LES) |

3900 |

0.210 |

1.050 |

/ |

0.920 |

1.380 |

88.0° |

/ |

| Young and Ooi [52] (LES) |

3900 |

0.212 |

1.030 |

0.177 |

0.908 |

/ |

/ |

/ |

| Dong et al. [53] (Expt.) |

4000 |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

1.470 |

/ |

-0.252 |

| Dong et al. [53] (DNS) |

3900 |

0.208 |

/ |

/ |

0.930 |

1.360 |

/ |

-0.291 |

| Rajani et al. [54] (LES, SSM) |

3900 |

0.214 |

1.050 |

/ |

0.928 |

1.211 |

87.5° |

-0.270 |

| Rajani et al. [54] (LES, DSM) |

3900 |

0.210 |

1.010 |

/ |

0.900 |

1.198 |

87.5° |

-0.280 |

| Jiang and Cheng [55] (LES) |

3900 |

0.212 |

0.994 |

0.161 |

0.893 |

1.444 |

/ |

/ |

| Lysenko et al. [56] (LES, SMAG) |

3900 |

0.190 |

1.180 |

0.440 |

0.800 |

0.900 |

89.0° |

-0.260 |

| Lysenko et al. [56] (LES, TKE) |

3900 |

0.209 |

0.970 |

0.090 |

0.910 |

1.670 |

88.0° |

-0.270 |

| Wornom et al. [57] (LES) |

3900 |

0.210 |

0.990 |

0.108 |

0.880 |

1.450 |

89.0° |

/ |

| Franke and Frank [58] (LES) |

3900 |

0.209 |

0.978 |

/ |

0.850 |

1.640 |

88.2° |

/ |

Figure 1.

(a) Configuration of the validation case, (b) Comparison of the spanwise-averaged time-averaged pressure coefficient along the cylinder surface, and (c) Comparison of the normalized spanwise-averaged time-averaged streamwise velocity along the Y = 0 line.

Figure 1.

(a) Configuration of the validation case, (b) Comparison of the spanwise-averaged time-averaged pressure coefficient along the cylinder surface, and (c) Comparison of the normalized spanwise-averaged time-averaged streamwise velocity along the Y = 0 line.

Figure 2.

(a, c, e) Comparison of the normalized spanwise-averaged time-averaged streamwise velocity, and (b, d, f) Comparison of the normalized spanwise-averaged fluctuating streamwise velocity at three cross-sections.

Figure 2.

(a, c, e) Comparison of the normalized spanwise-averaged time-averaged streamwise velocity, and (b, d, f) Comparison of the normalized spanwise-averaged fluctuating streamwise velocity at three cross-sections.

2.5. Research Scope

In order to systematically analyze the spanwise periodicity of the time-averaged flow structure within the gap, seventeen research cases are simulated for two tandem circular cylinders with

d/

D = 0.6 at

Re = 3900, namely

L/

D = 1.00, 1.10, 1.15, 1.20, 1.25, 1.50, 2.00, 2.25, 2.50, 3.00, 3.15, 3.24, 3.30, 3.50, 4.00, 5.00 and 6.00. As shown by

Table 1 and

Figure 3, the spanwise height is selected as

H = 8

D for

L/

D = 1.00~2.50, because the spanwise periodicity length (

Pz) lies in the range of (1.06~5.73)

D for these spacing ratios. However,

H = 4

D is adopted for

L/

D = 3.00~6.00 due to the fact that the possible spanwise periodicity length is only about (2.14~2.32)

D under this condition. The total grid points of each case fall within the scope of 8.81×10

6~17.49×10

6, and the grid points are clustered within the gap and near the cylinder surface. With respect to

δ/

D,

NLu,

NLd and the boundary conditions, all the seventeen research cases have the similar characteristics as the validation test. Moreover,

NL (the node number along the distance between two cylinder centers), the time step ∆

t and the computational domain are also provided in

Table 1. All the simulations are first run over 500s (i.e., approximate 100 vortex-shedding cycles) to reach the fully-developed wake, and then the flow fields are averaged for another 1000s (i.e., about 200 vortex-shedding cycles) to yield statistically independent time-averaged results.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Flow Pattern and Statistical Parameter

Different flow regimes are identified by examining the instantaneous spanwise vorticity (

) contours in the mid-height plane (

Z =

H/2), the time-averaged spanwise vorticity (

) contours in the transverse plane, the time-averaged

Q-criterion iso-surfaces within the gap, and the Strouhal number of the UC (

Std) and the DC (

StD).

Table 3 proves that six flow patterns can be defined in this study, namely

Small-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (

L/

D = 1.00~1.50),

Large-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (

L/

D = 2.00~2.25),

Non-periodic Reattachment Flow (

L/

D = 2.50~3.15),

Bi-stable Flow (

L/

D = 3.24),

Intermittent Lock-in Co-shedding Flow (

L/

D = 3.30~3.50) and

Subharmonic Lock-in Co-shedding Flow (

L/

D = 4.00~6.00).

Table 3 reveals that, in terms of St

d, St

D,

,

,

,

and

, an abrupt increase or decrease can be always observed in the vicinity of Bi-stable Flow (L/D = 3.24), being consistent with the previous observations [

25,

27,

32,

35,

37]. With regard to Large-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 2.00~2.25) and Non-periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 2.50~3.15), no dominant Strouhal number is recognized for the UC, the reason of which will be given out in the following sub-sections. When it comes to L/D = 3.30~6.00 (Co-shedding Flow), there are two dominant Strouhal numbers for the DC (i.e., the relatively larger

= 0.300~0.334 and the relatively smaller

= 0.167~0.169). In this study, the separation or reattachment angle is defined as the turning point between the positive and negative values of the normalized spanwise-averaged time-averaged wall shear stress along the cylinder surface, being similar to Hu et al. [

7] and Zhou et al. [

40].

Table 3 manifests that

only exists at L/D = 1.00~3.24, lying in the range of 51.45°~60.46°. In the vicinity of Bi-stable Flow (L/D = 3.24), a sharp increase from 86.03° to 91.00° can be detected for

, but, on the contrary, a sudden decline from 107.54° to 97.97° is captured for

.

3.2. Small-Scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 1.00~1.50)

With the aid of the instantaneous spanwise vorticity (

) contours in the mid-height plane (

Z =

H/2),

Figure 4(a, d, g, j, m, p) indicates that, when

L/

D = 1.00~1.50, the UC shear layers continuously reattach on two sides of the DC, and meanwhile a recirculating flow prevails within the gap region. Obviously, this flow pattern belongs to

Reattachment Flow in the literature. Furthermore, concerning the time-averaged spanwise vorticity (

) contours and the time-averaged streamwise velocity (

Umean) contours in the transverse plane within the gap, small-scale spanwise-periodic time-averaged flow structures (

Pz/

D = 1.06~3.74) can be observed (

Figure 4(b, e, h, k, n, q) and

Figure 5(a, c, e, g, i, k)). This is the reason why this flow pattern is named as

Small-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow. It should be noted that

Single Body Flow can not be identified here for two tandem circular cylinders with

d/

D = 0.6 at

Re = 3900, in accordance with Wang et al. [

33].

The 3D time-averaged vortical structures within the gap are displayed by means of the time-averaged

Q-criterion iso-surfaces (

Qmean). As expected,

Figure 4(c, f, i, l, o, r) manifests that distinct spanwise-periodic 3D time-averaged vortical structures can be recognized for

L/

D = 1.00~1.50. The strength of 3D time-averaged vortical structures continuously enhances with the increase of

L/

D, and hence

Qmean = 0.01, 0.05 and 0.10 are selected for

L/

D = 1.00~1.20, 1.25 and 1.50, respectively. Besides,

Figure 5(b, d, f, h, j, l) proves that, with regard to

Small-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (

L/

D = 1.00~1.50), the two cylinders have the same dominant Strouhal number when implementing the Fast Fourier Transform of the instantaneous lift coefficient (i.e.,

=

= 0.257,

=

= 0.262,

=

= 0.263,

=

= 0.264,

=

= 0.266 and

=

= 0.263), being consistent with Liu [

18] and Gao et al. [

36].

Table 3 and

Figure 4(a, d, g, j, m, p) reveal that, under the circumstance of

L/

D = 1.00~1.50, the spanwise-averaged time-averaged reattachment angle of the DC is relatively large (

= 57.86°~60.46°), and therefore only a small part of shear-layer vortices, shedding from two sides of the UC, are drawn into the gap region after impinging onto two sides of the DC. Due to the combined effect of both the limited amount of vortices within the gap region and the stabilization action caused by small

L/

D values, small-scale spanwise-periodic time-averaged flow structures (

Pz/

D = (0, 4]) are generated between two cylinders, which is actually the formation mechanism of

Small-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (

L/

D = 1.00~1.50).

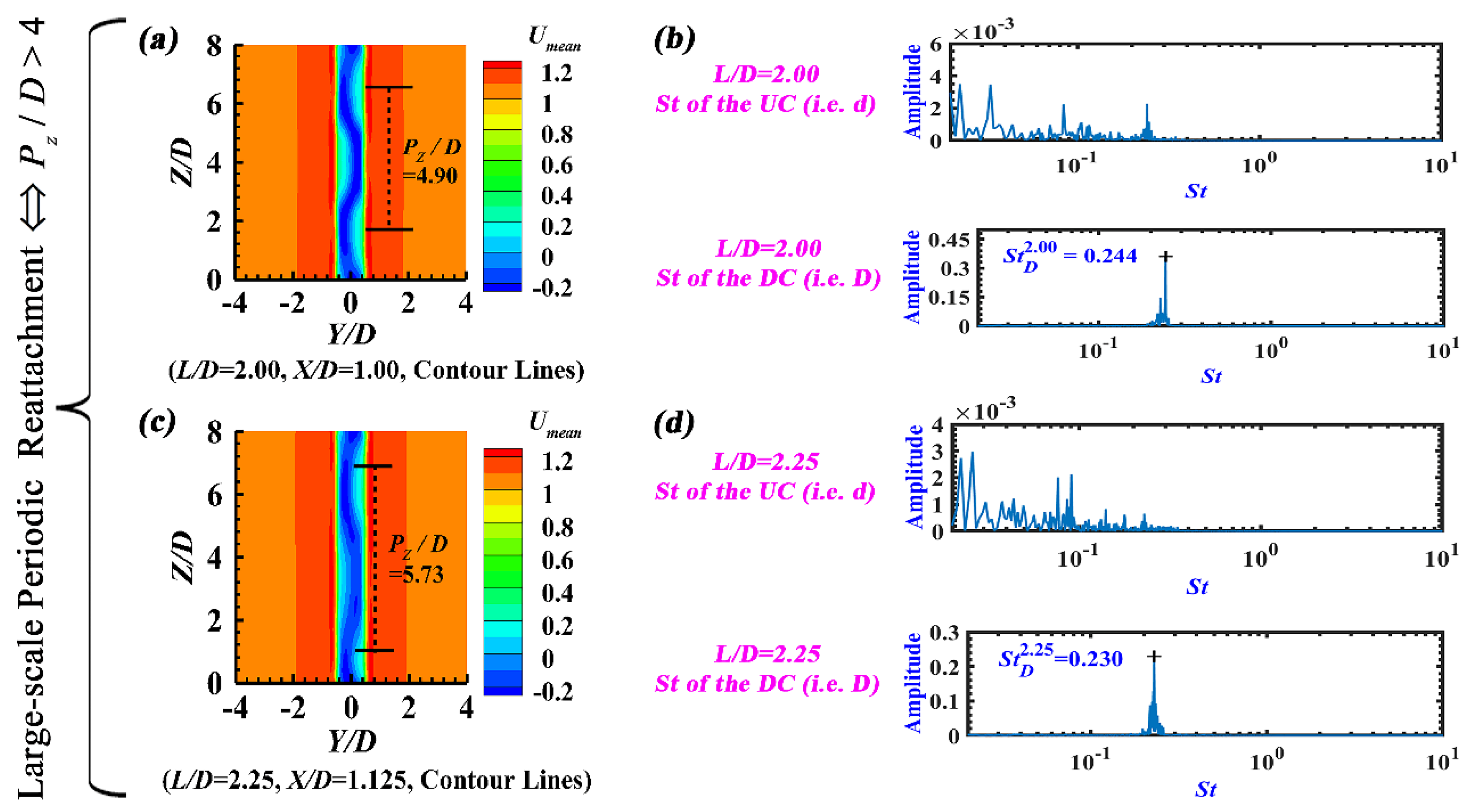

3.3. Large-Scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 2.00~2.25)

Figure 6(a, d) shows that, when

L/

D = 2.00 and 2.25, the UC shear layers still constantly reattach on the DC, and an unsteady recirculating flow occurs within the gap. Moreover,

Figure 6(b, e),

Figure 6(c, f) and

Figure 7(a, c) confirm that large-scale spanwise-periodic time-averaged flow structures (

Pz/

D = 4.90~5.73) can be captured from the time-averaged spanwise vorticity (

) contours and the time-averaged streamwise velocity (

Umean) contours in the transverse plane, as well as the time-averaged

Q-criterion iso-surfaces (

Qmean = 0.10) within the gap. Therefore, this flow pattern is called as

Large-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow in this study.

Figure 7(b, d) reveals that, when

L/

D = 2.00 and 2.25, the DC possesses one dominant Strouhal number (i.e.,

= 0.244 and

= 0.230), which results from its alternately shedding Karman vortex street in the wake, but the UC has no dominant Strouhal number. One reason is that no vortex shedding occurs from the UC (

Figure 6(a, d)), and the other reason is that the feedback effect of the DC vortex shedding on the UC is negligible due to relatively larger

L/

D values. In fact, both

Small-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (

L/

D = 1.00~1.50) and

Large-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (

L/

D = 2.00~ 2.25) share some similarity with

Reverse-Flow Reattachment proposed by Alam [

28] and Zhou et al. [

40], considering that for these flow regimes a part of the reattached shear layers is towards upstream after impinging onto the DC and the reverse flow can extend up to the backside of the UC. Nevertheless, in this study (unequal diameter case), the two shear layers simultaneously reattach on the two sides of the DC (

Figure 4(a, d, g, j, m, p) and

Figure 6(a, d)), but, in Alam [

28] and Zhou et al. [

40] (equal diameter case), the two shear layers alternately reattach on the two sides of the DC.

Table 3 and

Figure 6(a, d) disclose that, when

L/

D = 2.00~2.25, the spanwise-averaged time-averaged reattachment angle of the DC is

= 53.97°~55.04°, being smaller than

= 57.86°~60.46° of

Small-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow. Consequently, relative to

L/

D = 1.00~1.50, more shear-layer vortices, shedding from the two sides of the UC, are drawn into the gap at

L/

D = 2.00~2.25. Meanwhile, the spacing ratio of

L/

D = 2.00~2.25 is still small enough to provide the stabilization action necessary for the embroiled shear-layer vortices within the gap to produce the large-scale spanwise-periodic time-averaged flow structures (

Pz/

D > 4), which is the formation mechanism of

Large-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (

L/

D = 2.00~2.25). In terms of the time-averaged streamlines, the time-averaged streamwise/vertical velocity contours and the time-averaged spanwise vorticity contours, a pronounced asymmetry was detected in horizontal

X-

Y planes by Khorrami et al. [

59] for

Reattachment Flow (

d/

D = 1.0 and

L/

D = 1.435), but no clear explanation for its occurrence was given out. From

Figure 4~

Figure 7, it can be deduced that, in terms of the time-averaged spanwise vorticity contours, the time-averaged streamwise velocity contours and the time-averaged

Q-criterion iso-surfaces, a remarkable asymmetry along the transverse direction (

Y axis) exists in horizontal

X-

Y planes within the gap for

L/

D = 1.00~2.25, which means that both

Small-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow and

Large-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow are responsible for the aforementioned asymmetry. For example,

Figure 8(a, b, c, d, e, f) illustrates that the time-averaged streamwise velocity (

Umean) contours are asymmetric at different heights for

L/

D = 1.50 and 2.00, despite that the spanwise-averaged time-averaged streamwise velocity (

) contours are symmetric (

Figure 8(g, h)).

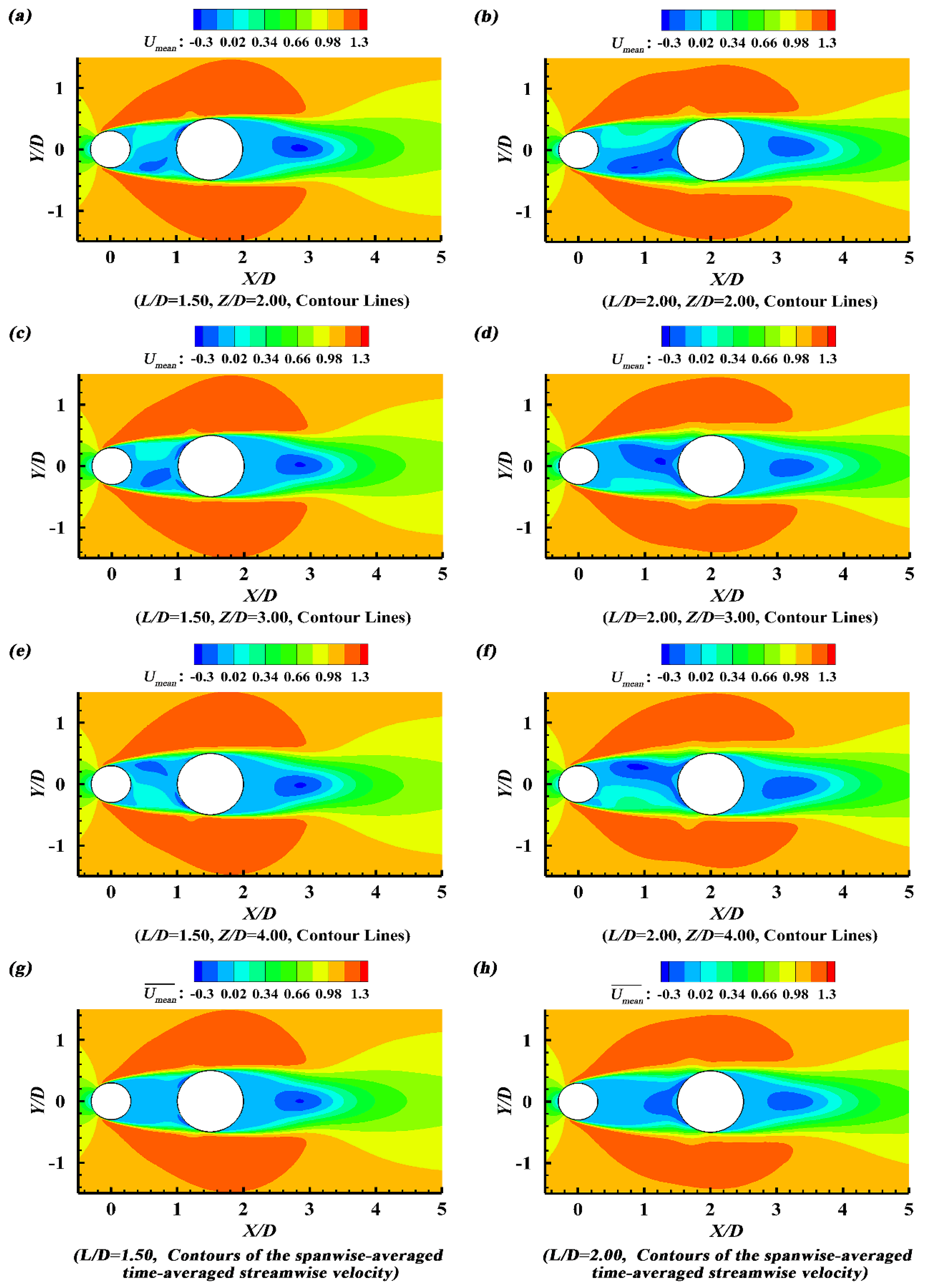

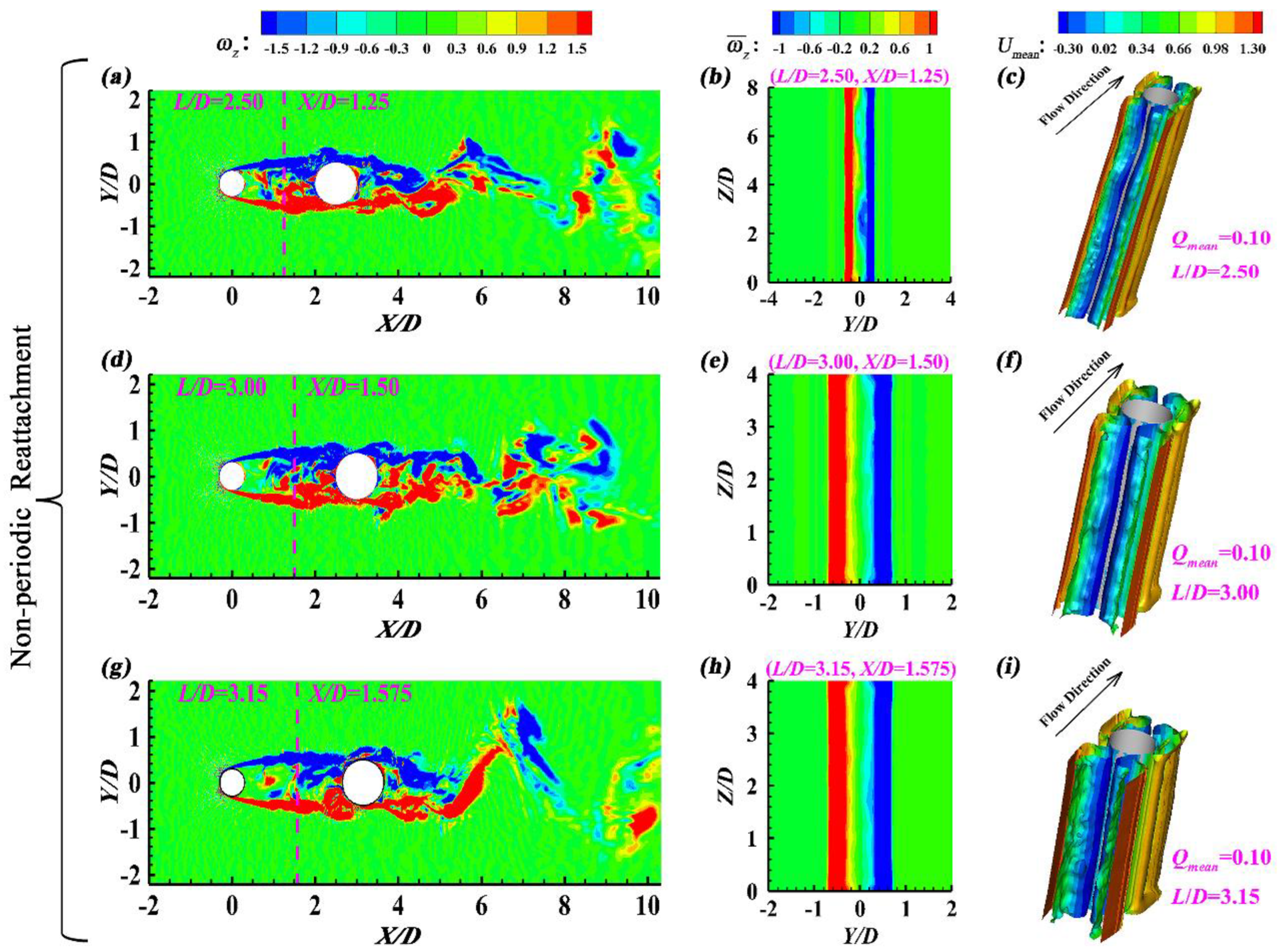

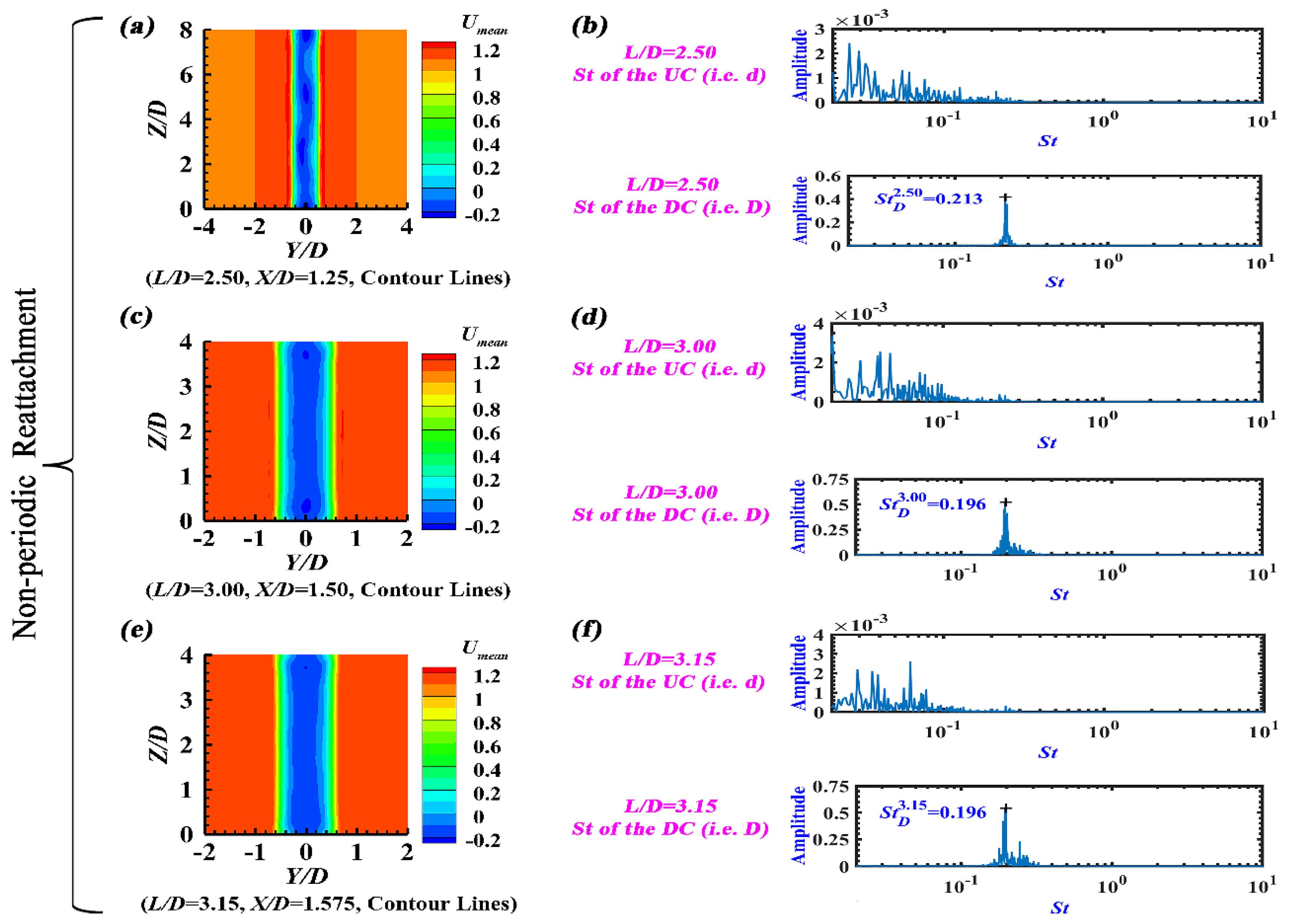

3.4. Non-Periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 2.50~3.15)

Figure 9(a, d, g) proves that, when

L/

D = 2.50~3.15, the UC shear layers also simultaneously reattach on the two sides of the DC. Under this condition, the reverse flow within the gap fails to reach the backside of the UC, behaving like the

Reverse-Flow No Reattachment observed by Zhou et al. [

40].

Figure 9(b, e, h),

Figure 9(c, f, i) and

Figure 10(a, c, e) demonstrate that no obvious spanwise-periodic time-averaged flow structures can be recognized for

L/

D = 2.50~3.15, in terms of the time-averaged spanwise vorticity (

) contours, the time-averaged streamwise velocity (

Umean) contours and the time-averaged

Q-criterion iso-surfaces of (

Qmean = 0.10) within the gap. Therefore, this flow pattern is defined as

Non-periodic Reattachment Flow in this study. Furthermore,

Figure 10(b, d, f) makes it clear that, only one dominant Strouhal number is observed for the DC (

= 0.213,

= 0.196 and

= 0.196), but no dominant Strouhal number is discerned for the UC, being identical to both

Large-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (

L/

D = 2.00~2.25) in this study and the steady reattachment regime reported by Alam et al. [

27].

Table 3 and

Figure 9(a, d, g) manifest that, when

L/

D = 2.50~3.15, the spanwise-averaged time-averaged reattachment angle of the DC is

= 52.54°~53.74°, being smaller than

= 53.97°~55.04° of

Large-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow and

= 57.86°~60.46° of

Small-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow. Consequently, relative to

L/

D = 1.00~2.25, more shear-layer vortices, shedding from the two sides of the UC, are drawn into the gap at

L/

D = 2.50~3.15. Meanwhile, the spacing ratio of

L/

D = 2.50~3.15 is too large to provide the stabilization action necessary for the embroiled shear-layer vortices to generate the spanwise-periodic time-averaged flow structures within the gap, which is the formation mechanism of

Non-periodic Reattachment Flow.

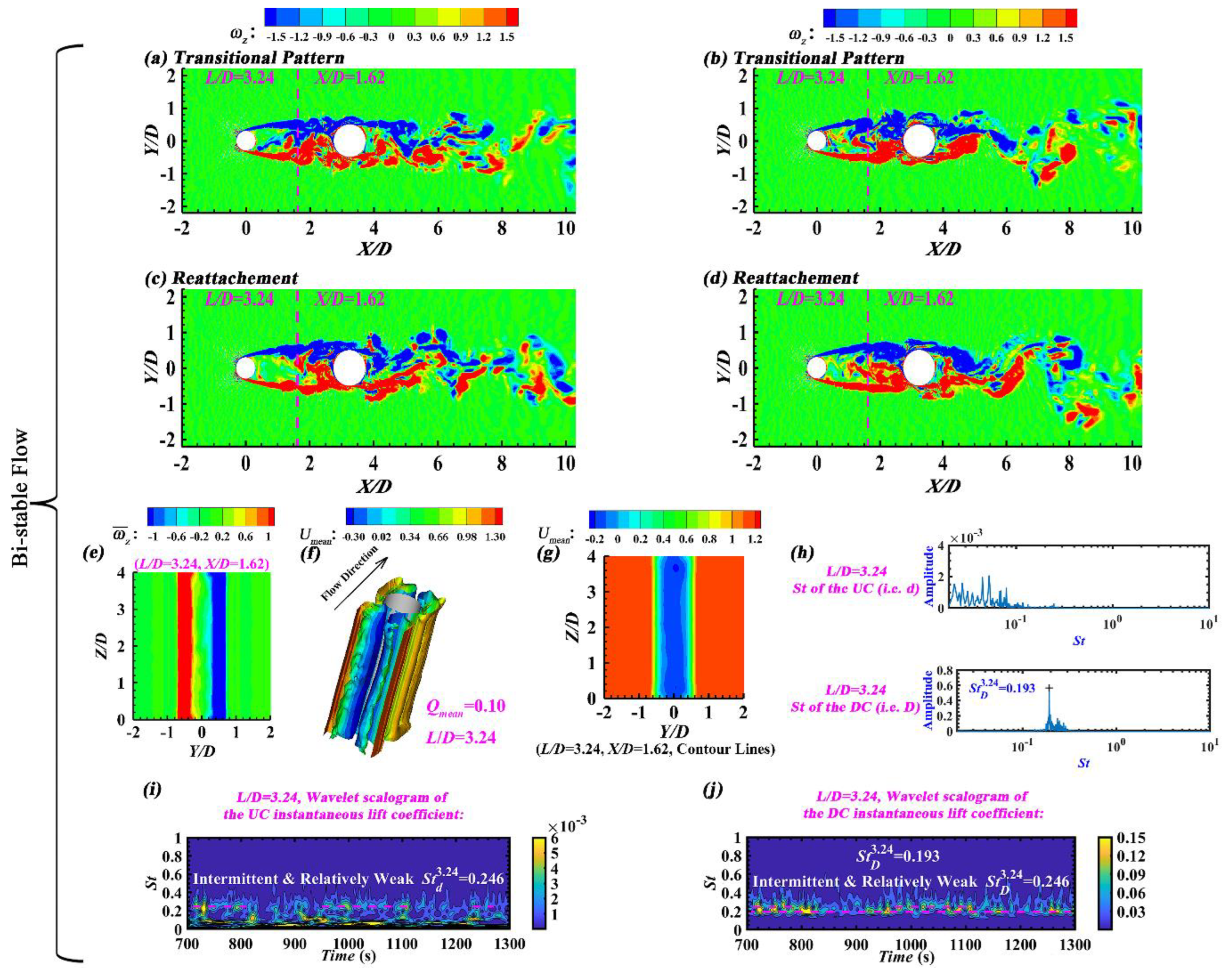

3.5. Bi-Stable Flow (L/D = 3.24)

This study reconfirms the occurrence of the well-known

Bi-stable Flow at the transition from

Reattachment Flow to

Co-shedding Flow [

25,

60].

Figure 11 verifies the co-existence of two flow states at a given configuration, namely the reattachment pattern (

Figure 11(c, d)) and the transitional pattern (

Figure 11(a, b)), switching intermittently from one to another.

Bi-stable Flow defined in this study is different from that reported by Gao et al. [

36] and Carmo et al. [

61]. As stated by Rastan and Alam [

29], the latter is actually the hysteresis (HS) phenomenon in the literature [

19,

62,

63].

Figure 11(e, f, g) shows that, being identical to

Non-periodic Reattachment Flow (

L/

D = 2.50~3.15), no obvious spanwise-periodic time-averaged flow structures are detected for

Bi-stable Flow (

L/

D = 3.24), in terms of the time-averaged spanwise vorticity (

) contours, the time-averaged streamwise velocity (

Umean) contours, and the time-averaged

Q-criterion iso-surfaces (

Qmean = 0.10) within the gap. Besides, no dominant Strouhal number is perceived for the UC and only one dominant Strouhal number is recognized for the DC (

= 0.193,

Figure 11(h)) for

L/

D = 3.24 when implementing the Fast Fourier Transform of the instantaneous lift coefficient, having similar characteristic as

Non-periodic Reattachment Flow (

L/

D = 2.50~3.15,

Figure 10(b, d, f)) and

Large-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (

L/

D = 2.00~2.25,

Figure 7(b, d)). For

Bi-stable Flow, the reattachment pattern is predominant, but the transitional pattern is intermittent and relatively weak, being consistent with the results of Kitagawa and Ohta [

6] and Alam et al. [

64].

Figure 11(i, j) presents that, when performing the continuous wavelet analysis of the instantaneous lift coefficient, an intermittent and relatively weak Strouhal number (

=

= 0.246) is clearly visible for both cylinders, which corresponds to the transitional pattern of

Bi-stable Flow. In addition, the present critical spacing ratio (

L/

D)

c is equal to 3.24, being close to the value in the literature [

6,

7,

21,

23,

25,

27,

33,

37,

60,

65].

3.6. Co-Shedding Flow (L/D = 3.30~6.00)

Figure 12(a, d, g, j, m) illustrates that antisymmetric Karman vortex shedding mode is captured both within the gap region and behind the DC for

L/

D = 3.30~6.00, which means the occurrence of

Co-shedding Flow. Moreover,

Figure 12(b, e, h, k, n),

Figure 12(c, f, i, l, o) and

Figure 13(a, c, e, g, i) indicate that the spanwise-periodic time-averaged flow structures (

Pz/

D = 2.14~2.32) can be observed with the aid of the time-averaged spanwise vorticity (

) contours, the time-averaged streamwise velocity (

Umean) contours and the time-averaged

Q-criterion iso-surfaces (

Qmean = 0.10) within the gap. Alam and Zhou [

30], Wang et al. [

33] and Alam et al. [

34] subdivided

Co-shedding Flow into lock-in, intermittent lock-in, subharmonic lock-in and no lock-in, depending on the values of

Re,

d/

D and

L/

D.

Figure 13(b, d) manifests that, for

L/

D = 3.30 and 3.50, there is only one dominant Strouhal number for the UC (i.e.,

= 0.300 and

= 0.308, respectively), being attributed to the UC vortex-shedding. However, two dominant Strouhal numbers are visible for the DC (i.e.,

=

= 0.300 &

= 0.168 at

L/

D = 3.30;

=

= 0.308 &

= 0.169 at

L/

D = 3.50). Obviously,

and

are generated by the influence of the UC vortex-shedding, but

and

are caused by the DC vortex-shedding. Considering that

=

,

≠ (0.48~0.52)

,

=

and

≠ (0.48~0.52)

, this flow regime belongs to

Intermittent Lock-in Co-shedding, which was also observed by Alam et al. [

34] (please see the first row of

Figure 6(a, d) in their article).

Figure 13(f, h, j) demonstrates that, for

L/

D = 4.00, 5.00 and 6.00, one dominant Strouhal number of the DC is equal to that of the UC (i.e.,

=

= 0.319,

=

= 0.330 and

=

= 0.334, respectively), and the other dominant Strouhal number of the DC is nearly half that of the UC (i.e.,

= (0.48~0.52)

= 0.167,

= (0.48~0.52)

= 0.168 and

= (0.48~0.52)

= 0.167, respectively, lying within the uncertainty due to the frequency resolution in power spectral density). Therefore, this flow regime belongs to

Subharmonic Lock-in Co-shedding, being in accordance with the results of Alam et al. [

34]. In fact,

Figure 12(b, e, h, k, n),

Figure 12(c, f, i, l, o) and

Figure 13(a, c, e, g, i) prove that both

Intermittent Lock-in Co-shedding (

L/

D = 3.30~3.50) and

Subharmonic Lock-in Co-shedding (

L/

D = 4.00~6.00) have the similar spanwise-periodic length (

Pz/

D = 2.14~2.32) for the time-averaged flow structures within the gap, and the strength of the spanwise periodicity continuously decreases with the increase of

L/

D.

Figure 12.

Co-shedding Flow (L/D = 3.30~6.00): (a, d, g, j, m) The instantaneous spanwise vorticity () contours in the mid-height plane, (b, e, h, k, n) The time-averaged spanwise vorticity () contours in the transverse plane, and (c, f, i, l, o) The time-averaged Q-criterion iso-surfaces within the gap.

Figure 12.

Co-shedding Flow (L/D = 3.30~6.00): (a, d, g, j, m) The instantaneous spanwise vorticity () contours in the mid-height plane, (b, e, h, k, n) The time-averaged spanwise vorticity () contours in the transverse plane, and (c, f, i, l, o) The time-averaged Q-criterion iso-surfaces within the gap.

Figure 13.

Co-shedding Flow (L/D = 3.30~6.00): (a, c, e, g, i) The time-averaged streamwise velocity (Umean) contours in the transverse plane, and (b, d, f, h, j) The Strouhal number based on the instantaneous lift coefficient.

Figure 13.

Co-shedding Flow (L/D = 3.30~6.00): (a, c, e, g, i) The time-averaged streamwise velocity (Umean) contours in the transverse plane, and (b, d, f, h, j) The Strouhal number based on the instantaneous lift coefficient.

4. Conclusions

Flows around two different-sized tandem circular cylinders with d/D = 0.6 are systematically studied at seventeen spacing ratios (L/D = 1.00, 1.10, 1.15, 1.20, 1.25, 1.50, 2.00, 2.25, 2.50, 3.00, 3.15, 3.24, 3.30, 3.50, 4.00, 5.00 and 6.00) at Re = 3900. The analysis focuses on the flow regimes and the spanwise periodicity of the time-averaged flow structures within the gap. The main findings include the following:

By examining the instantaneous spanwise vorticity () contours, the time-averaged spanwise vorticity () contours, the time-averaged streamwise velocity (Umean) contours, the time-averaged Q-criterion iso-surfaces and the Strouhal number based on the instantaneous lift coefficient, the flow is divided into six regimes, namely Small-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 1.00~1.50, Pz/D = (0, 4] within the gap), Large-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 2.00~2.25, Pz/D > 4 within the gap), Non-periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 2.50~3.15, no spanwise periodicity within the gap), Bi-stable Flow (L/D = 3.24, no spanwise periodicity within the gap), Intermittent Lock-in Co-shedding (L/D = 3.30~3.50, ≠ (0.48~0.52), Pz/D = 2.14~2.32 within the gap) and Subharmonic Lock-in Co-shedding (L/D = 4.00~6.00, = (0.48~0.52), Pz/D = 2.14~2.32 within the gap). Moreover, it is concluded that, the formation mechanisms of the aforementioned three reattachment sub-flow regimes are related to both the L/D value (determining the strength of the stabilization action necessary for the generation of the spanwise-periodic time-averaged flow structures within the gap) and the spanwise-averaged time-averaged reattachment angle of the DC (, deciding the amount of the UC shear-layer vortices drawn into the gap).

For Bi-stable Flow (L/D = 3.24), the reattachment pattern is predominant, while the transitional pattern is secondary. Although no dominant Strouhal number is detected for the UC and only one dominant Strouhal number is recognized for the DC ( = 0.193) when implementing the Fast Fourier Transform, an intermittent and relatively weak Strouhal number ( = = 0.246) is clearly visible for both cylinders when performing the continuous wavelet analysis, which corresponds to the frequency of the transitional pattern in Bi-stable Flow. Additionally, with regard to Reattachment Flow, a pronounced asymmetry along the transverse direction was observed within the gap by some researchers, but no clear explanation for its occurrence has ever been given. This study displays that both Small-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 1.00~1.50) and Large-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 2.00~2.25) are essentially responsible for the aforementioned asymmetry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Z. and Y.L.; methodology, D.Z., J.D. and D.L.; software, D.Z. and J.X.; validation, D.Z. and J.X.; formal analysis, D.Z. and Y.L.; investigation, D.Z. and J.X.; resources, D.Z., D.L. and J.D.; data curation, D.Z., Y.L. and J.X.; writing-original draft preparation, D.Z.; writing-review and editing, D.L., J.D. and Y.L.; visualization, D.Z. and J.X.; supervision, D.L., J.D. and Y.L.; project administration, D.Z. and Y.L.; funding acquisition, D.Z., D.L., J.D. and Y.L.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (51909024, 51939007 and 52179060), State Key Laboratory of Hydraulics and Mountain River Engineering (SKHL2019), and Cambridge Tsinghua Joint Research Initiative Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The computing resources from the Lingyun Supercomputing Center in Dalian University of Technology are highly acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, D.; Yang, Q.; Ma, X.; Dai, G. Free surface characteristics of flow around two side-by-side circular cylinders. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2018, 6(3), 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Mao, Z.; Tian, W.; Zhang, T. Numerical investigation on vortex-induced vibration suppression of a circular cylinder with axial-slats. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2019, 7(12), 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamain, J.; Touboul, J.; Rey, V.; Belibassakis, K. Porosity Effects on the Dispersion Relation of Water Waves through Dense Array of Vertical Cylinders. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8(12), 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Cao, Z.; Guo, Z. Numerical investigation of vortex shedding from a 5:1 rectangular cylinder at different angles of attack. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10(12), 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abucide-Armas, A.; Portal-Porras, K.; Fernandez-Gamiz, U.; Zulueta, E.; Teso-Fz-Betoño, A. Convolutional Neural Network Predictions for Unsteady Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes-Based Numerical Simulations. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11(2), 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, T.; Ohta, H. Numerical investigation on flow around circular cylinders in tandem arrangement at a subcritical Reynolds number. J. Fluids Struct. 2008, 24(5), 680–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, X.; You, Y. On the flow around two circular cylinders in tandem arrangement at high Reynolds numbers. Ocean Eng. 2019, 189, 106301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yang, S.; Wang, L.; Huan, C.; Zhang, J. Numerical Investigation on Vortex-Induced Vibrations of Two Cylinders with Unequal Diameters. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11(2), 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Zhen, X.; Huang, Y.; Wang, W. Numerical investigation on hydrodynamic characteristics of immersed buoyant platform. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9(2), 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadri, M.; Kadivar, E.; El Moctar, O. Numerical Simulation of Cavitation Control around a Circular Cylinder Using Porous Surface by Volume Penalized Method. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12(3), 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahir, N.; Rockwell, D. Vortex formation from a forced system of two cylinders. Part I: tandem arrangement. J. Fluids Struct. 1996, 10(5), 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Alam, M.M. Wake of two interacting circular cylinders: a review. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2016, 62, 510–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Alam, M.M.; Zhou, Y. Drag reduction of circular cylinder using linear and sawtooth plasma actuators. Phys. Fluids 2021, 33(12), 124105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazvanova, A.; Yin, G.; Ong, M.C. Numerical Investigation of Flow around Two Tandem Cylinders in the Upper Transition Reynolds Number Regime Using Modal Analysis. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10(10), 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, H.; Luo, Z.; Yang, T.; Dong, G. Study of Hydrokinetic Energy Harvesting of Two Tandem Three Rigidly Connected Cylinder Oscillators Driven by Fluid-Induced Vibration. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12(3), 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowdy, D.G. Uniform flow past a periodic array of cylinders. Eur. J. Mech. B-Fluids 2016, 56, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Ma, C.; Kim, E.S.; Nowakowski, G.; Mauer, E.; Bernitsas, M.M. Flow-induced vibration of tandem circular cylinders with selective roughness: Effect of spacing, damping and stiffness. Eur. J. Mech. B-Fluids 2019, 74, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.M. The predominant frequency for viscous flow past two tandem circular cylinders of different diameters at low Reynolds number. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part M- J. Eng. Marit. Environ. 2020, 234(2), 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasaka, Y.; Kon, S.; Schouveiler, L.; Le Gal, P. Hysteretic mode exchange in the wake of two circular cylinders in tandem. Phys. Fluids 2006, 18(8), 084104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.F.; Yang, J.C.; Ni, M.J.; Zhang, N.M.; Yu, X.G. Experimental and numerical studies on the three-dimensional flow around single and two tandem circular cylinders in a duct. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34(3), 033610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Zhou, Y. Strouhal numbers in the wake of two inline cylinders. Exp. Fluids 2004, 37, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, B.S.; Meneghini, J.R. Numerical investigation of the flow around two circular cylinders in tandem. J. Fluids Struct. 2006, 22(6-7), 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.C.; Ahn, J.; Hwang, J.H. Numerical simulation of flow past two circular cylinders in tandem and side-by-side arrangement at low Reynolds numbers. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2016, 20, 1594–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, A.; Hussaini, M.Y. An application of delayed detached eddy simulation to tandem cylinder flow field prediction. Comput. Fluids 2012, 60, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grioni, M.; Elaskar, S.A.; Mirasso, A.E. A numerical study of the flow interference between two circular cylinders in tandem by scale-adaptive simulation model. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 2020, 13(1), 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdravkovich, M.M. The effects of interference between circular cylinders in cross flow. J. Fluids Struct. 1987, 1(2), 239–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Moriya, M.; Takai, K.; Sakamoto, H. Fluctuating fluid forces acting on two circular cylinders in a tandem arrangement at a subcritical Reynolds number. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2003, 91(1-2), 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M. The aerodynamics of a cylinder submerged in the wake of another. J. Fluids Struct. 2014, 51, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastan, M.R.; Alam, M.M. Transition of wake flows past two circular or square cylinders in tandem. Phys. Fluids 2021, 33(8), 081705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Zhou, Y. Strouhal numbers, forces and flow structures around two tandem cylinders of different diameters. J. Fluids Struct. 2008, 24(4), 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, F.; Alam, M.M. A low Reynolds number flow and heat transfer topology of a cylinder in a wake. Phys. Fluids 2018, 30(8), 083603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X. Effect of an upstream cylinder on the wake dynamics of two tandem cylinders with different diameters at low Reynolds numbers. Phys. Fluids 2021, 33(8), 083605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Alam, M.M.; Zhou, Y. Two tandem cylinders of different diameters in cross-flow: Effect of an upstream cylinder on wake dynamics. J. Fluid Mech. 2018, 836, 5–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Elhimer, M.; Wang, L.; Jacono, D.L.; Wong, C.W. Vortex shedding from tandem cylinders. Exp. Fluids 2018, 59(3), 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahir, N.; Altaç, Z. Numerical investigation of flow and heat transfer characteristics of two tandem circular cylinders of different diameters. Heat Transf. Eng. 2017, 38(16), 1367–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Etienne, S.; Yu, D.; Wang, X.; Tan, S. Bi-stable flow around tandem cylinders of different diameters at low Reynolds number. Fluid Dyn. Res. 2011, 43(5), 055506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, G.V.; Yue, D.K.; Triantafyllou, M.S.; Karniadakis, G.E. Three-dimensionality effects in flow around two tandem cylinders. J. Fluid Mech. 2006, 558, 387–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.X.; Liu, C.B.; Hu, H.Z.; Zheng, Y.G. Three-dimensional numerical simulation of the flow around two cylinders at supercritical Reynolds number. Fluid Dyn. Res. 2013, 45(5), 055504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Ren, A.L.; Zou, J.F.; Shao, X.M. Three-dimensional flow around two circular cylinders in tandem arrangement. Fluid Dyn. Res. 2006, 38(6), 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Alam, M.M.; Cao, S.; Liao, H.; Li, M. Numerical study of wake and aerodynamic forces on two tandem circular cylinders at Re = 103. Phys. Fluids 2019, 31(4), 045103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Xiao, Z. New insight on large-eddy simulation of flow past a circular cylinder at subcritical Reynolds number 3900. AIP Adv. 2020, 10(8), 085321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Cheng, L.; An, H.; Draper, S. Flow around a surface-mounted finite circular cylinder completely submerged within the bottom boundary layer. Eur. J. Mech. B-Fluids 2021, 86, 169–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Cheng, L.; An, H.; Zhao, M. Direct numerical simulation of flow around a surface-mounted finite square cylinder at low Reynolds numbers. Phys. Fluids 2017, 29(4), 045101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Jiang, C.; Liang, D.; Cheng, L. A review on TVD schemes and a refined flux-limiter for steady-state calculations. J. Comput. Phys. 2015, 302, 114–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Jiang, C.; Cheng, L.; Liang, D. A refined r-factor algorithm for TVD schemes on arbitrary unstructured meshes. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 2016, 80(2), 105–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenco, L.M.; Shih, C. Characteristics of the plane turbulent near wake of a circular cylinder. A Particle Image Velocimetry Study 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg, C. An experimental investigation of the flow around a circular cylinder: influence of aspect ratio. J. Fluid Mech. 1994, 258, 287–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Karamanos, G.S.; Karniadakis, G.E. Dynamics and low-dimensionality of a turbulent near wake. J. Fluid Mech. 2000, 410, 29–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravchenko, A.G.; Moin, P. Numerical studies of flow over a circular cylinder at ReD = 3900. Phys. Fluids 2000, 12(2), 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnaudeau, P.; Carlier, J.; Heitz, D.; Lamballais, E. Experimental and numerical studies of the flow over a circular cylinder at Reynolds number 3900. Phys. Fluids 2008, 20(8), 085101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.; Hickel, S.; Adams, N.A. Assessment of implicit large-eddy simulation with a conservative immersed interface method for turbulent cylinder flow. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2010, 31(3), 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.E.; Ooi, A. Comparative assessment of LES and URANS for flow over a cylinder at a Reynolds number of 3900. 16th Australasian Fluid Mechanics Conference, Australia 2007, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, S.; Karniadakis, G.E.; Ekmekci, A.; Rockwell, D. A combined direct numerical simulation–particle image velocimetry study of the turbulent near wake. J. Fluid Mech. 2006, 569, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajani, B.N.; Kandasamy, A.; Majumdar, S. LES of flow past circular cylinder at Re= 3900. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 2016, 9(3), 1421–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Cheng, L. Large-eddy simulation of flow past a circular cylinder for Reynolds numbers 400 to 3900. Phys. Fluids 2021, 33(3), 034119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, D.A.; Ertesvåg, I.S.; Rian, K.E. Large-eddy simulation of the flow over a circular cylinder at Reynolds number 3900 using the OpenFOAM toolbox. Flow Turbul. Combust. 2012, 89(10), 491–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wornom, S.; Ouvrard, H.; Salvetti, M.V.; Koobus, B.; Dervieux, A. Variational multiscale large-eddy simulations of the flow past a circular cylinder: Reynolds number effects. Comput. Fluids 2011, 47(1), 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, J.; Frank, W. Large eddy simulation of the flow past a circular cylinder at ReD = 3900. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2002, 90(10), 1191–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorrami, M.R.; Choudhari, M.M.; Lockard, D.P.; Jenkins, L.N.; McGinley, C.B. Unsteady flowfield around tandem cylinders as prototype component interaction in airframe noise. AIAA J. 2007, 45(8), 1930–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalan, H.; Jaiman, R. Numerical study of the flow interference between tandem cylinders employing non-linear hybrid URANS–LES methods. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2015, 142, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, B.S.; Meneghini, J.R.; Sherwin, S.J. Possible states in the flow around two circular cylinders in tandem with separations in the vicinity of the drag inversion spacing. Phys. Fluids 2010, 22(5), 054101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jester, W.; Kallinderis, Y. Numerical study of incompressible flow about fixed cylinder pairs. J. Fluids Struct. 2003, 17(4), 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, B.S.; Meneghini, J.R.; Sherwin, S.J. Secondary instabilities in the flow around two circular cylinders in tandem. J. Fluid Mech. 2010, 644, 395–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Rastan, M.R.; Wang, L.; Zhou, Y. Flows around two nonparallel tandem circular cylinders. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2022, 220, 104870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahir, N.; Altaç, Z. Numerical investigation of convective heat transfer in unsteady flow past two cylinders in tandem arrangements. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2008, 29(5), 1309–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 3.

(a) The 3D computational domain, (b) The 2D computational grids in the X-Y plane, and (c) Close-up view around two tandem circular cylinders for different research cases.

Figure 3.

(a) The 3D computational domain, (b) The 2D computational grids in the X-Y plane, and (c) Close-up view around two tandem circular cylinders for different research cases.

Figure 4.

Small-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 1.00~1.50): (a, d, g, j, m, p) The instantaneous spanwise vorticity () contours in the mid-height plane, (b, e, h, k, n, q) The time-averaged spanwise vorticity () contours in the transverse plane, and (c, f, i, l, o, r) The time-averaged Q-criterion iso-surfaces within the gap.

Figure 4.

Small-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 1.00~1.50): (a, d, g, j, m, p) The instantaneous spanwise vorticity () contours in the mid-height plane, (b, e, h, k, n, q) The time-averaged spanwise vorticity () contours in the transverse plane, and (c, f, i, l, o, r) The time-averaged Q-criterion iso-surfaces within the gap.

Figure 5.

Small-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 1.00~1.50): (a, c, e, g, i, k) The time-averaged streamwise velocity (Umean) contours in the transverse plane, and (b, d, f, h, j, l) The Strouhal number based on the instantaneous lift coefficient.

Figure 5.

Small-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 1.00~1.50): (a, c, e, g, i, k) The time-averaged streamwise velocity (Umean) contours in the transverse plane, and (b, d, f, h, j, l) The Strouhal number based on the instantaneous lift coefficient.

Figure 6.

Large-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 2.00~2.25): (a, d) The instantaneous spanwise vorticity () contours in the mid-height plane, (b, e) The time-averaged spanwise vorticity () contours in the transverse plane, and (c, f) The time-averaged Q-criterion iso-surfaces within the gap.

Figure 6.

Large-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 2.00~2.25): (a, d) The instantaneous spanwise vorticity () contours in the mid-height plane, (b, e) The time-averaged spanwise vorticity () contours in the transverse plane, and (c, f) The time-averaged Q-criterion iso-surfaces within the gap.

Figure 7.

Large-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 2.00~2.25): (a, c) The time-averaged streamwise velocity (Umean) contours in the transverse plane, and (b, d) The Strouhal number based on the instantaneous lift coefficient.

Figure 7.

Large-scale Periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 2.00~2.25): (a, c) The time-averaged streamwise velocity (Umean) contours in the transverse plane, and (b, d) The Strouhal number based on the instantaneous lift coefficient.

Figure 8.

The asymmetry in horizontal planes for L/D = 1.50 & 2.00: (a, b, c, d, e, f) The time-averaged streamwise velocity contours at different heights, and (g, h) The spanwise-averaged time-averaged streamwise velocity contours.

Figure 8.

The asymmetry in horizontal planes for L/D = 1.50 & 2.00: (a, b, c, d, e, f) The time-averaged streamwise velocity contours at different heights, and (g, h) The spanwise-averaged time-averaged streamwise velocity contours.

Figure 9.

Non-periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 2.50~3.15): (a, d, g) The instantaneous spanwise vorticity () contours in the mid-height plane, (b, e, h) The time-averaged spanwise vorticity () contours in the transverse plane, and (c, f, i) The time-averaged Q-criterion iso-surfaces within the gap.

Figure 9.

Non-periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 2.50~3.15): (a, d, g) The instantaneous spanwise vorticity () contours in the mid-height plane, (b, e, h) The time-averaged spanwise vorticity () contours in the transverse plane, and (c, f, i) The time-averaged Q-criterion iso-surfaces within the gap.

Figure 10.

Non-periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 2.50~3.15): (a, c, e) The time-averaged streamwise velocity (Umean) contours in the transverse plane, and (b, d, f) The Strouhal number based on the instantaneous lift coefficient.

Figure 10.

Non-periodic Reattachment Flow (L/D = 2.50~3.15): (a, c, e) The time-averaged streamwise velocity (Umean) contours in the transverse plane, and (b, d, f) The Strouhal number based on the instantaneous lift coefficient.

Figure 11.

Bi-stable Flow (L/D = 3.24): (a, b, c, d) The instantaneous spanwise vorticity contours in the mid-height plane, (e) The time-averaged spanwise vorticity contours in the transverse plane, (f) The time-averaged Q-criterion iso-surfaces, (g) The time-averaged streamwise velocity contours in the transverse plane, (h) The Strouhal number obtained by Fast Fourier Transform, and (i, j) The wavelet scalogram of the instantaneous lift coefficient.

Figure 11.

Bi-stable Flow (L/D = 3.24): (a, b, c, d) The instantaneous spanwise vorticity contours in the mid-height plane, (e) The time-averaged spanwise vorticity contours in the transverse plane, (f) The time-averaged Q-criterion iso-surfaces, (g) The time-averaged streamwise velocity contours in the transverse plane, (h) The Strouhal number obtained by Fast Fourier Transform, and (i, j) The wavelet scalogram of the instantaneous lift coefficient.

Table 3.

Classification of flow regimes, and comparison of the spanwise periodicity length (Pz/D) within the gap, the Strouhal number (Std or StD) based on the instantaneous lift coefficient, the spanwise-averaged time-averaged drag coefficient ( or ), the spanwise-averaged time-averaged separation angle ( or ) and the spanwise-averaged time-averaged reattachment angle of the DC () for all the seventeen research cases.

Table 3.

Classification of flow regimes, and comparison of the spanwise periodicity length (Pz/D) within the gap, the Strouhal number (Std or StD) based on the instantaneous lift coefficient, the spanwise-averaged time-averaged drag coefficient ( or ), the spanwise-averaged time-averaged separation angle ( or ) and the spanwise-averaged time-averaged reattachment angle of the DC () for all the seventeen research cases.

| Flow Regime |

Case |

Pz/D |

Std |

StD |

|

|

|

|

|

| Small-scale Periodic Reattachment |

L/D = 1.00 |

1.06 |

0.257 |

0.257 |

0.751 |

0.237 |

86.10° |

57.86° |

98.55° |

|

L/D = 1.10 |

1.67 |

0.262 |

0.262 |

0.757 |

0.201 |

86.21° |

60.05° |

98.93° |

|

L/D = 1.15 |

2.12 |

0.263 |

0.263 |

0.762 |

0.186 |

86.24° |

60.15° |

100.08° |

|

L/D = 1.20 |

2.59 |

0.264 |

0.264 |

0.765 |

0.173 |

86.25° |

60.30° |

100.26° |

|

L/D = 1.25 |

2.78 |

0.266 |

0.266 |

0.766 |

0.156 |

86.26° |

60.46° |

100.40° |

|

L/D = 1.50 |

3.74 |

0.263 |

0.263 |

0.777 |

0.129 |

86.26° |

59.01° |

101.92° |

| Large-scale Periodic Reattachment |

L/D = 2.00 |

4.90 |

/ |

0.244 |

0.759 |

0.136 |

86.14° |

55.04° |

104.31° |

|

L/D = 2.25 |

5.73 |

/ |

0.230 |

0.748 |

0.134 |

86.11° |

53.97° |

105.15° |

| Non-periodic Reattachment |

L/D = 2.50 |

/ |

/ |

0.213 |

0.738 |

0.146 |

86.08° |

53.74° |

105.46° |

|

L/D = 3.00 |

/ |

/ |

0.196 |

0.724 |

0.170 |

86.05° |

52.78° |

106.91° |

|

L/D = 3.15 |

/ |

/ |

0.196 |

0.721 |

0.186 |

86.04° |

52.54° |

107.51° |

| Bi-stable Flow |

L/D = 3.24 |

/ |

/

(0.246)a

|

0.193

(0.246)b

|

0.719 |

0.188 |

86.03° |

51.45° |

107.54° |

|

Intermittent Lock-inCo-shedding

|

L/D = 3.30 |

2.32 |

0.300 |

0.300 &

0.168 |

1.048 |

0.698 |

91.00° |

/ |

97.97° |

|

L/D = 3.50 |

2.14 |

0.308 |

0.308 &

0.169 |

1.050 |

0.702 |

91.00° |

/ |

97.76° |

|

Subharmonic Lock-inCo-shedding

|

L/D = 4.00 |

2.27 |

0.319 |

0.319 &

0.167 |

1.098 |

0.707 |

91.23° |

/ |

96.49° |

|

L/D = 5.00 |

2.14 |

0.330 |

0.330 &

0.168 |

1.104 |

0.764 |

91.21° |

/ |

96.29° |

|

L/D = 6.00 |

2.27 |

0.334 |

0.334 &

0.167 |

1.115 |

0.787 |

91.22° |

/ |

96.11° |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).