Introduction

Mitochondrial encephalomyopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) syndrome is rare, inherited disorder that results in nervous system and muscle dysfunction and has distinctive imaging features. MELAS is one of the most prevalent mitochondrial disorders transmitted from mothers [

1]. Point mutations in the mitochondrial DNA are linked to this condition. Disease results from this impacting the synthesis of proteins in the mitochondria and the metabolism of nutrients. Early adulthood is frequently when sickness first manifests [

2].

As the name suggests, the hallmark of the MELAS syndrome is stroke-like events. This disorder's clinical course varies greatly; it can be asymptomatic with normal early development or progressive muscular weakness, encephalopathy, convulsions, lactic acidosis, cognitive impairment, and early death. MELAS primarily affects tissue with high energy demands such as the brain, muscles, and heart. Stroke like episodes can cause neurological deficits, while lactic acidosis results from impaired energy production. However, with considerable genetic and clinical manifestation variation, only around half of individuals exhibit conventional clinical signs [

3,

4].

Despite advancements in understanding its pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management, MELAS remains a diagnostic challenge due to its heterogeneous presentation and overlap with other mitochondrial disorders. In this case report, we present a comprehensive analysis of a patient diagnosed with MELAS, highlighting the clinical manifestations, diagnostic approach, therapeutic interventions, and prognosis. Our case underscores the importance of early recognition and multidisciplinary management of MELAS to improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

Case presentation:

A 31-year old male patient belonging from lower socioeconomic class presented to the emergency department with the chief complains of perspiration, uneasiness and weight loss with increase in appetite. The patient was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes mellitus at 15 years of age. He started developing myoclonic jerks, 3 years later, which made him unable to hold fine objects. Hence he was admitted at that time and was advised MRI. MRI performed showed no significant findings, so the patient was started on anti-epileptics. After starting anti-epileptics patient developed bilateral hearing impairment which was of insidious onset and gradually progressive (right followed by left) with loss of vision in left eye (in 2016) for which he was operated later. The patient experienced multiple hospital stays and numerous investigations following the recurrence of similar concerns, but no definitive results were found.

The patient’s clinical scenario is not associated with headache, vomiting, fever, dripping, or dragging of the foot. There is no difficulty in swallowing, chewing, or facial asymmetry.

There is no History of any sleep alteration or alteration in smell, ptosis or any sensory abnormality on the face, tinnitus, vertigo, regurgitation of food or fluid & no nasal twang of voice.

Past history:

The patient is a known case of type 1 diabetes mellitus since 15 years of age.

Physical Examination:

Physical examination showed a temperature of 98.6 F, pulse rate of 86/min, blood pressure of 110/82, SpO2 97% on room air, and RBS of 440 mg/dl. Respiratory examination showed a respiratory rate of 18/min and bilateral equal air entry was present. S1S2 were present on cardiovascular examination. The patient was conscious and well oriented to time, place and person. He was responding to verbal commands. On fundal examination, bilateral optic atrophy present.

On Neurological examination, tone was normal at all the joints. Power 5/5 was present in all four limbs. Deep tendon reflexes were normal with bilateral flexor plantar response. No significant family history was present. No cerebellar signs were present. Sensory examination showed no deficits.

Lab investigations:

Blood examination, liver function test, renal function test and lipid profile were normal [

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3]. ECG showed normal sinus rhythm within normal limits. HbA1c was 10.4 (normal <6) and serum lactate levels was 4.2mmol/L (normal range).

Radiological Examination:

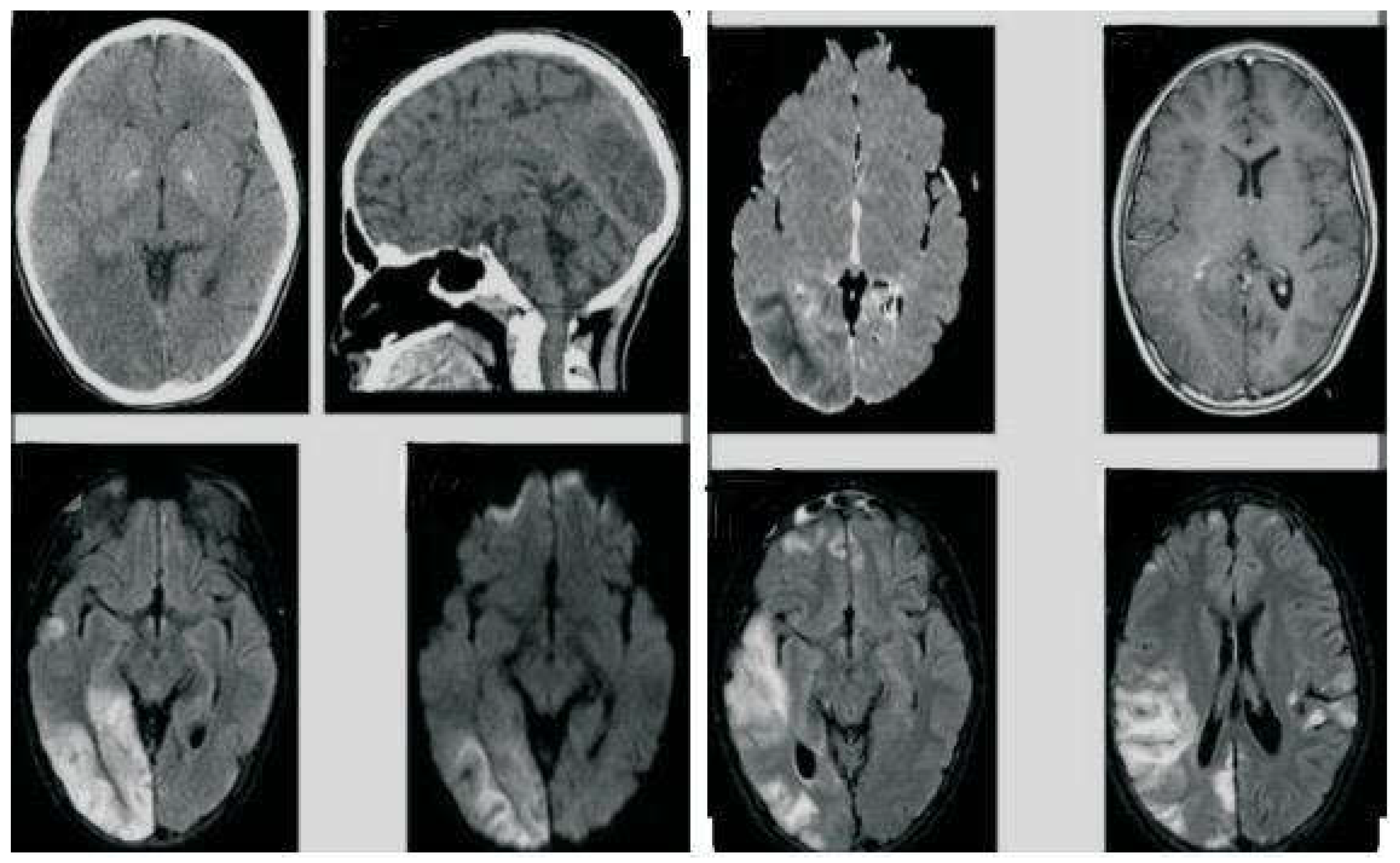

On MRI, Gliosis in right posterior Parieto-occipital lobe with dilatation of occipital horn of right lateral ventricle was noted (

Figure 1).

EEG performed showed mild diffuse generalised cerebral dysfunction but did not demonstrate conclusive epileptiform discharges. Laboratory values were within normal limits, but she had elevated lactate levels of 5.6 mmol/L (normal 0.5-1 mmol/L) in his CSF study. Pure tone audiometry showed bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. Cardiac function was normal. Genetic analysis targeting MT-TL1 gene was performed in New Delhi which came out to be positive.

Management:

There is no specific management in case of MELAS. Symptomatic management with multidisciplinary team of doctors was required. Apart from that anti epileptics, antidepressants, Insulin therapy, prokinetics where the main stay for the management.

Follow up:

This patient was followed up after 20 days, and there has been no recurrence or aggravation of his overall condition.

Diagnosis:

The patient was diagnosed with Mitochondrial encephalomyopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) syndrome based on the clinical presentation, imaging results, and response to the therapy.

Discussion:

Mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) is a multisystem mitochondrial disease that is progressively debilitating. MELAS is maternally inherited mitochondrial diseases. The estimated incidence of MELAS is 1 in 4,000 persons [

5]. The main clinical hallmarks of this type of the disease are hyper lactic acidemia and stroke-like episodes, and it was initially described by Pavlakis et al [

6].

All nucleated human cells include double membrane organelles called mitochondria, which carry out a number of vital tasks such as producing the majority of cellular energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). The electron transport chain (ETC) complexes, which move protons, transfer electrons, and create ATP, are located inside the inner mitochondrial membrane. Mitochondrial malfunction and subsequent mitochondrial disorders can be caused by mutations in the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) or nuclear DNA (nDNA) genes associated to the mitochondria. A malfunctioning mitochondria cannot produce enough ATP to meet the energy requirements of different organs, especially those with high energy demands, such as the neurological system [

7]. When the body breaks down carbohydrates for energy, lactic acid is produced as a by-product.

MELAS syndrome can cause stroke-like episodes, dementia, epilepsy, lactic acidemia, myopathy, recurrent headaches, hearing loss, diabetes, and short stature, among other symptoms. With 65–76% of affected people presenting at or before the age of 20, childhood is the typical age of onset. Merely 5–8% of people are present before the age of 2 and 1-6 years after the age of 40 [

8,

9]. In MELAS syndrome, sensorineural hearing loss is usually modest, insidiously progressive, and frequently an early clinical symptom as in our case [

10].

Genetic testing, imaging tests such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, and other techniques, tests of blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid in addition to muscle biopsy (if necessary) may be used to diagnose MELAS syndrome. Diagnostic workup in our case revealed normal lactate levels in blood but elevated lactate level in cerebrospinal fluid. MRI findings was consistent with mitochondrial dysfunction, and the presence of the m.3243A>G mutation on genetic testing. These findings supported the diagnosis of MELAS.

Management of MELAS remains largely supportive, focusing on symptom alleviation and metabolic stabilization. While no curative treatments exist, interventions such as mitochondrial cocktails, antioxidants, and ketogenic diet have shown promise in ameliorating symptoms and potentially altering disease progression. However, the effectiveness of these approaches varies among individuals, underscoring the need for personalized therapeutic regimens.

The long-term prognosis of MELAS is variable, influenced by factors such as age of onset, severity of symptoms, and presence of comorbidities. While some patients experience a relatively stable course with intermittent exacerbations, others may exhibit progressive neurological deterioration and multiorgan involvement. Early recognition, prompt intervention, and close monitoring are essential for optimizing outcomes and mitigating complications.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, our case highlights the clinical complexity and diagnostic challenges associated with MELAS. Through a multidisciplinary approach encompassing clinical evaluation, biochemical testing, and genetic analysis, we can enhance our understanding of MELAS pathophysiology and refine therapeutic strategies. Continued research efforts are warranted to unravel the intricacies of mitochondrial dysfunction and pave the way for novel treatment modalities in MELAS management.

Funding

None of the authors are financially interested in any of the products, devices, or drugs mentioned in this manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Being a case report study, there were no ethical issues and the IRB was notified about the topic and the case. Still, no formal permission was required as this was a record-based case report. Permission from the patient for the article has been acquired and ensured that their information or identity is not disclosed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Scaglia, F.; Northrop, J.L. The mitochondrial myopathy encephalopathy, lactic acidosis with stroke-like episodes (MELAS) syndrome: a review of treatment options. CNS Drugs. 2006, 20, 443–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Jiang, G.; Ju, X.; Fu, H. MELAS and macroangiopathy: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018, 97, e13866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancuso, M.; Orsucci, D.; Angelini, C.; Bertini, E.; Carelli, V.; Comi, G.P.; et al. The m.3243A>G mitochondrial DNA mutation and related phenotypes. A matter of gender? J Neurol. 2014, 261, 504–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, P.; Engelstad, K.; Wei, Y.; Kulikova, R.; Oskoui, M.; Battista, V.; et al. Protean phenotypic features of the A3243G mitochondrial DNA mutation. Arch Neurol. 2009, 66, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MELAS Syndrome.

- Pavlakis, S.G.; Phillips, P.C.; DiMauro, S.; De Vivo, D.C.; Rowland, L.P. Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes: a distinctive clinical syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1984, 16, 481–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hattab, A.W.; Adesina, A.M.; Jones, J.; Scaglia, F. MELAS syndrome: Clinical manifestations, pathogenesis, and treatment options. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 2015, 116, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yatsuga, S.; Povalko, N.; Nishioka, J.; Katayama, K.; Kakimoto, N.; Matsuishi, T.; et al. MELAS: a nationwide prospective cohort study of 96 patients in Japan. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012, 1820, 619–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, M.; Pavlakis, S.G. Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes (MELAS): current concepts. J Child Neurol. 1994, 9, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sproule, D.M.; Kaufmann, P. Mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes: basic concepts, clinical phenotype, and therapeutic management of MELAS syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008, 1142, 133–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).