1. Introduction

Researchers are continuously exploring novel combinations of nanoparticles and base fluids to enhance the thermal conductivity, convective heat transfer coefficient, and overall heat transfer performance of nanofluids. Recent studies have focused on optimizing the nanoparticle concentration, size, shape, and surface characteristics to achieve superior heat transfer enhancement. Hybrid nanofluids are being investigated for various thermal management applications, including cooling systems in electronics, heat exchangers, solar thermal collectors, and automotive cooling systems. The ability of hybrid nanofluids to improve heat transfer efficiency and thermal stability makes them promising candidates for addressing thermal management challenges in modern engineering systems. Computational modeling and numerical simulation techniques play a crucial role in predicting the heat and mass transfer characteristics of hybrid nanofluids.

Researchers are developing advanced computational models based on techniques such as computational fluid dynamics (CFD), molecular dynamics (MD), and lattice Boltzmann methods to simulate the behavior of hybrid nanofluids at the nanoscale and macroscopic levels. Despite the promising performance of hybrid nanofluids in laboratory settings, there are practical challenges related to scalability, stability over long-term usage, and cost-effectiveness that need to be addressed for their widespread industrial applications. Researchers are working on developing scalable synthesis methods, improving nanoparticle dispersion techniques, and conducting cost-benefit analyses to facilitate the transition of hybrid nanofluids from the lab to real-world applications. Umair Khan et al. [

1] studies aimed at offering a computational solution for the flow of a wall jet (WJ) incorporating thermal and mass transportation phenomena. Their study focuses on a colloidal suspension consisting of SAE50 and zinc oxide nanoparticles, which are submerged in a Brinkman-extended Darcy model. Belal et al. [

2] examined how the utilization of blended individual and hybrid nano additives, including graphene nanoplatelets, ZnO, and an ionic liquid (IL) named Trihexyltetradecylphosphonium bis(2,4,4-trimethylpentyl) phosphinate, affects the rheological, tribological, and physical properties of rapeseed oil.

The work of Zia Ullah et. al. [

3] primarily focuses on the enhanced rate of chemical processes in the magneto-nanofluid flow and the physical manifestation of viscous dissipation. Oriana Palma Calabokis et al. [

4] studied the problem to enhance the wear and friction properties of frictional components—which are mostly found in rolling bearings, gearboxes, and engines—metal conditioners (MC) are added to lubricants. Its primary objective in entering the Brazilian market is to increase its market share in internal combustion engines. Their investigation focused on the effects of mixing metal conditioners (MC) with SAE 5W-30 API SN commercial engine oil on the thermal and rheological characteristics. Zawar Hussain et al. [

5] investigated the flow of copper and alumina nanoparticles mixed with sodium alginate-based Casson hybrid nanofluid across a stretching sheet. In this problem, they assumed convective and slip boundary conditions. Najiyah Safwa Khashi'ie et al. [

6] investigated the presence of velocity slip and convective conditions; a hybrid Cu-Al

2O

3/water nanofluid flows towards a stretching/shrinking sheet. It is considered necessary to maintain an adequate wall mass suction to maintain the shrinking flow through a permeable sheet. Bilal et al. [

7] described features of a three-dimensional boundary layer flow of Williamson fluid that is restricted by a bidirectional stretched surface in magnetohydrodynamics (MHD). It is assumed that the fluid conductivity varies with temperature. Heat transfer via generative/absorptive processes is also taken into account. Muhammad Ramzan et al. [

8] simulated the three-dimensional MHD flow over an extending sheet of micropolar and Williamson fluids. Their study examines activation energy and heat radiation influence. Also, Brownian motion, chemical reaction, and thermal migration impact are calculated. Numerical investigation is conducted on continuous three-dimensional mixed convection flow of nanofluids under slip circumstances over a permeable vertical stretching/shrinking sheet in magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) by Anuar Jamaludin et al. [

9]. In their study, two types of nanofluids, namely Cu-water and Ag-water, were examined. Ishtiaq Khan et al. [

10] studied the utilization of nanoliquids holds significant potential across various fields including heat exchangers, food processing, biomedicine, cooling electronics, and transportation. Their analysis takes into account of the impact of velocity slips, zero mass flux, and thermal convection. Interestingly, the zero-mass flux situation at the wall negates the hybrid nano liquid flow's wall mass transfer rate.

Nanofluids hold considerable importance for researchers owing to their notably high heat transfer rates, making them valuable for industrial applications Tanzila Hayat et al. [

11]. Recently, a novel class of nanofluids, termed "hybrid nanofluids," has emerged, aiming to further augment heat transfer rates. The newly developed 3D model is utilized to investigate the influence of heat generation, heat radiation, and chemical reaction on a stretching wall with rotation. Awatif Alhowaity et al. [

12] examined the energy and mass transfer rates in the flow of a Williamson hybrid nanofluid (NF) is a porous surface that is stretched and contains silver (Ag) and magnesium oxide (MgO) nanoparticles (NPs). By dispersing magnesium oxide (MgO) and silver (Ag) nanoparticles in the base fluid (engine oil), the hybrid nanofluid is created. Additionally, the present analysis investigates the effects of a constant magnetic field heat source and heat dissipation. The introduction of the hybrid nanofluid concept has sparked advancements in enhancing heat transfer within boundary layer flows Suriya Uma Devi et al. [

13]. In their study the novel thermo physical properties models have been developed and experimental thermal conductivity values are compared with our proposed model. Two distinct types of fluids, specifically Hybrid nanofluid (Cu-Al

2O

3/Water) and Nanofluid (Cu/Water), are utilized in the investigation of move past a stretching sheet.

Ram Prakash Sharma et al. [

14] study compares the effects of both linear and nonlinear stretching sheets on the heat transfer properties over a curved surface spiralling in a circle at different radial distances. The impacts of the Soret-Dufour phenomenon in the presence of injection velocity and heat source/sink are also examined in this article. Silver and copper oxide hybrid nanoparticles are used, with water serving as the base fluid. The investigation is conducted on the flow of a methanol-based hybrid fluid over a curved stretching sheet by Revathi et al. [

15] study by considering the cross-diffusion effects (Soret–Dufour numbers) and also activation energy. Further, the visualization of entropy generation in the fluid flow is also performed. For instance, specific heat and thermal conductivity exhibit an increase at higher temperatures. Experimental research has revealed that methanol-based hybrid nanofluids (CH

3OH + SiO

2 + Al

2O

3) effectively increase the rate of absorption of CO

2 in a tray column absorber. Motahar Reza et al. [

16] conducted a numerical study to examine the effects of Soret and Dufour phenomena on the creation of entropy in a (AlN-Al2O3) hybrid nanofluid flowing across a stretched plate through a permeable medium saturated with hybrid nanofluid. To explore the impact of thermo-diffusion and diffuse-thermal effects on entropy generation in this scenario, a transverse magnetic field has been employed. Their study investigates the enhancement of heat transfer rates using a mixture of Aluminium Nitride (AlN) and Alumina (Al

2O

3) nanoparticles. The demand for improved thermal conductivity to handle boosting the density of heat in miniature and various technical procedures has prompted an examination of the thermal transport properties of hybrid nanofluids by Asmat Ullah Yahya et al. [

17]. In this context, MoS

2 and ZnO are combined as a highly diluted homogeneous composition within a great quantity of engine oil. This colloidal fluid flows over a stretched sheet through a porous media, in the presence of heat transformation. The study of Shami Alsallami et al. [

18] goals at enhancement of engine oil's thermal characteristics by adding a suspension of Williamson hybrid nanofluid. Zinc oxide (ZnO) and molybdenum disulfide (MoS

2) are suspended in the hybrid nanofluid. Viscosity dissipation properties and external heat sources are added to increase the system's heating capability. The problem studied by Sreedevi et al. [

19] entails the analysis of thermal and mass transformation in an inconstant magneto-hydrodynamic movement of a hybrid nanofluid on a stretching sheet. The scenario includes the presence of chemical reactions, suction, slip effects, and thermal radiation.

The work of Mubashar Arshad et al. [

20] examines the three-dimensional magneto-hydrodynamic nanofluid flow over two stretching surfaces, taking into account the effects of thermal radiation and chemical reactions in addition to the effect of an inclining magnetic field. In their comparative study, several rotational nanofluids and hybrid nanofluids with a constant angular velocity are investigated. The analysis of a nonlocal fractional model for viscous nanofluid with hybrid nanostructure is presented by Yu-Ming Chu et al. [

21]. To develop a hybrid nanofluid, copper (Cu) and aluminium oxide (Al

2O

3) nanoparticles were mixed and distributed within a base fluid of water (H

2O). Within a microchannel, the magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) free convection flow of the Cu-Al

2O

3-H

2O nanofluid was examined. The flow of an incompressible hybrid nanofluid over a rotating disk that is endlessly impermeable is examined by Tassaddiq et al. [

22]. To improve the examination of the nanoliquids flow's fine point, the effect of a magnetic field has been included. In their work, magnetic ferrite nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) contained in a carrier fluid like water are studied in relation to the classical von Karman flow over a spinning disk. The standard fluid water which suspends two different kinds of hybrid nanoparticles—single-walled CNTs (SWCNTs) and multi-walled CNTs (MWCNTs) considered in the study by Shanmugapriya et al. [

23]. To further explore the complexities of hybrid nanofluid flow, the effects of heat radiation, activation energy, and magnetic fields have been included in addition to binary chemical reactions.

The study of Sohail Ahmad et al. [

24] revels that, the hybrid nanofluids demonstrate superior mechanical resistance, physical strength, chemical stability, thermal conductivity, and other properties in comparison to individual nanoliquids. In their study, it is aimed to introduce a novel investigation into the magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) flow of hybrid nanoparticles through a permeable medium, considering viscous dissipation, as they pass over a stretching surface. The study of Abdulmajeed Almaneea [

25] examines the impact of hybrid nanoparticles on thermal and mass transformation in both heterogeneous and homogeneous chemical reactions. The Williamson parameter can have a notable impact on momentum transport. The Darcy-Forchheimer flow of a Casson hybrid nanofluid through a continuously expanding curved surface was studied by Gohar et al. [

26]. The Darcy-Forchheimer effect characterizes the viscous fluid flow within a porous medium. Hybrid nanofluids are created using carbon nanotubes (CNTs) in cylindrical form and iron oxide. An inquiry is underway to elucidate the flow behavior of a Ree-Eyring hybrid nanofluid under stretching flow conditions by Ali et al. [

27]. Studied SiO

2 and GO are under investigation for their potential use as hybrid nanoparticles in combination with carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) in water at low concentrations. A concentration range between 0.0 and 0.4 % is recommended for use as the base fluid (CMC-water). The work of Wei-Feng Xia et al. [

28] focuses on the three-dimensional nonlinear mixed convective boundary layer flow of a micropolar hybrid nanofluid under numerous slip conditions and in the presence of microorganisms along the narrowing surface. The goal of their study is to learn more about carbon nanotubes (CNTs), which are very popular because of their consistent physicochemical properties, high thermal and electrical conductivities, mechanical and chemical stability, and lightweight design. The objective of the research of Saeed Dinarv et al. [

29] analyze the Falkner-Skan problem, which is the steady laminar incompressible two-dimensional boundary layer flow of a TiO

2-CuO/water hybrid nanofluid over a fixed or moving wedge or corner. One-phase hybrid nanofluids are modelled using a novel mass-centric approach in which the masses of the base fluid, the first and second nanoparticles, and both are regarded as essential inputs for establishing the effective thermophysical parameters of the hybrid nanofluid. The extension of a hybrid nanofluid made of Cu, Al

2O

3, and H

2O between two infinite vertical parallel plates is covered in the study of Muhammad Saqib et al. [

30]. studied the energy equation in conjunction with the Brinkman-type fluid model to depict the flow phenomena between two parallel plates filled with hybrid nanofluids.

Overall, research in the field of heat and mass transfer of hybrid nanofluids continues to evolve, driven by the demand for efficient thermal management solutions in various industrial sectors. As advancements in nanomaterial synthesis, characterization techniques, and computational modeling tools progress, hybrid nanofluids are expected to play an increasingly important role in enhancing heat transfer efficiency and sustainability in diverse engineering applications. The present study aims at understanding the heat and mass transformation of Casson hybrid nano fluid (MoS2 + ZnO) based with engine oil over a stretched wall with chemical reaction and thermo-diffusion effects.

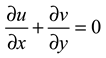

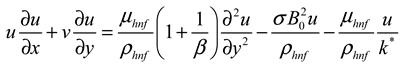

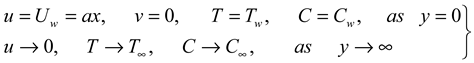

2. Materials and Methods

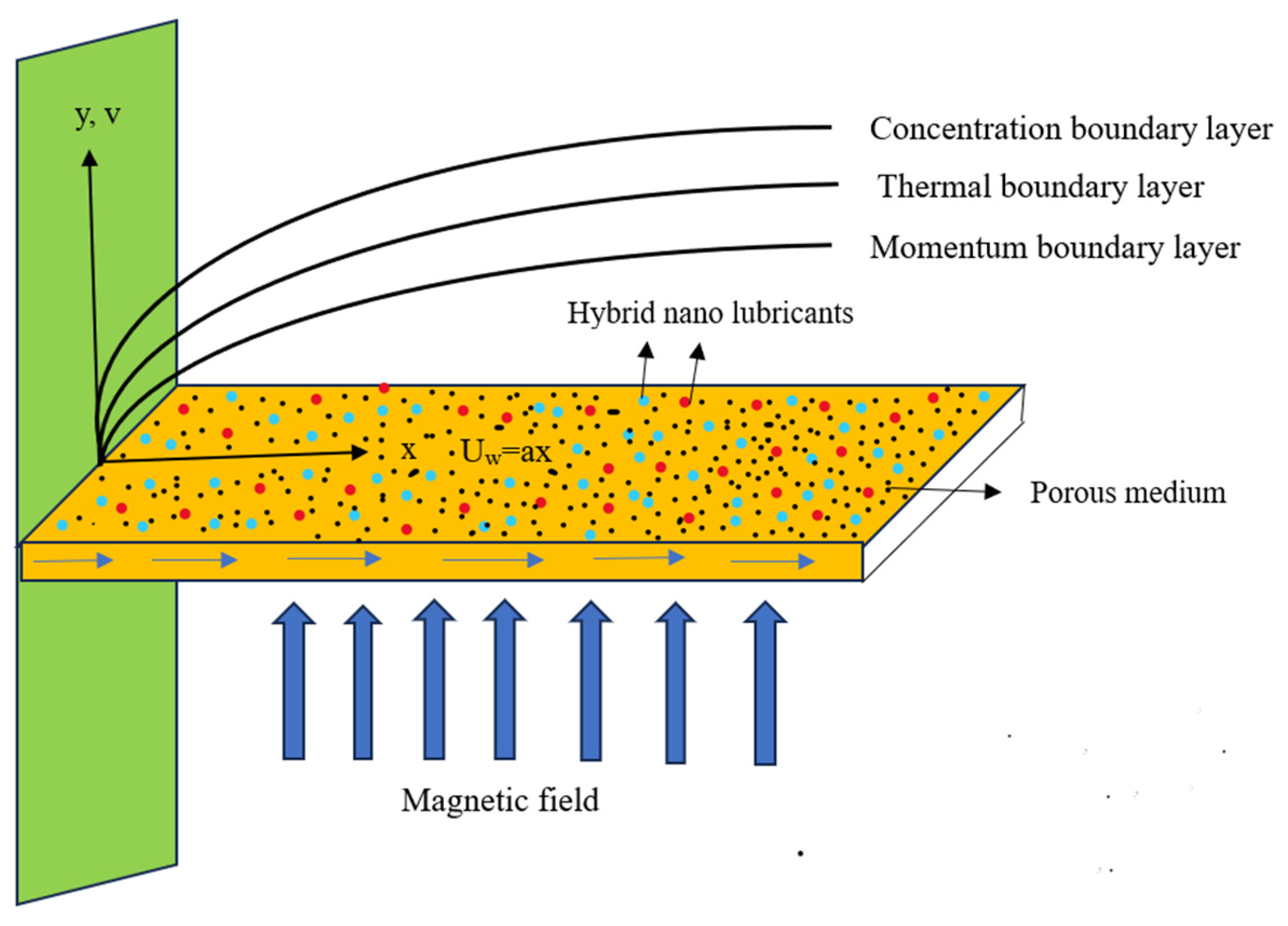

Consider a mathematical formulation for two two-dimensional (2D) in-compressible Casson hybrid nanofluids past a stretched surface. Cartesian coordinates (x, y) and velocity components (u, v) with a fluid flow arrangement are shown in

Figure 1 as the problem’s design. The interface of the applied magnetic field with dynamic viscosity and a porous media is used to study mass diffusion and heat transfer. The magnetic field B

0 is applied along the x-axis. The governing equations of this problem are as follows:

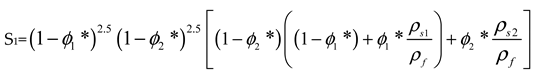

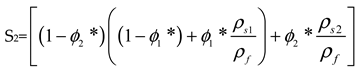

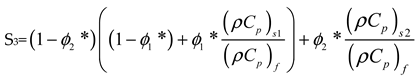

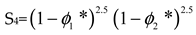

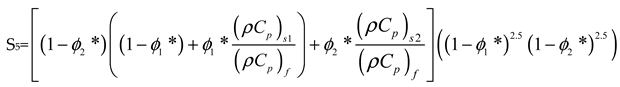

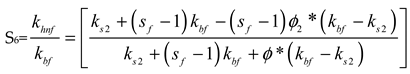

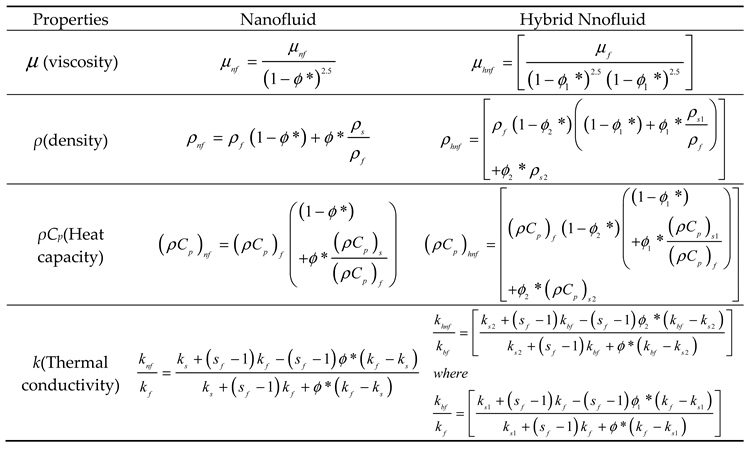

The flow of the hybrid nanofluids are explained here with the help of thermo-physical characteristics. , and are the volume fraction of hybrid nano fluids. To create the required nanolubricant, ZnO nanoparticles are mixed with 0.01 vol of MoS2/engine oil. Considering = 0.04 and = 0 for MoS2 /Engine oil in this model. For hybrid nano lubricant = 0.03 and = 0.01 to yield MoS2 + ZnO /Engine oil over all the research.

The flow of the hybrid nanofluids are explained here with the help of thermo-physical characteristics.

,

and

are the volume fraction of hybrid nano fluids. To create the required nanolubricant, ZnO nanoparticles are mixed with 0.01 vol of MoS2/engine oil. Considering

= 0.04 and

= 0 for

MoS2 /Engine oil in this model. For hybrid nano lubricant

= 0.03 and

= 0.01 to yield

MoS2 +

ZnO /Engine oil over all the research. To be explicit,

Table 1 presents the valuable thermo-physical characteristics of both nano lubricants and hybrid nano lubricants. The fundamental thermo-physical properties of nanofluids are derived from the literature review mentioned below.

Table 2 provides information on the thermophysical properties of engine oil used as the base fluid.

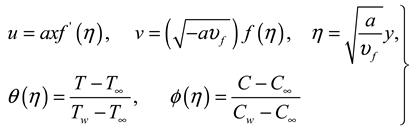

2.1. Similarity Variables

In order to solve equations (1)–(4) subject to the boundary conditions (5), the similarity transformation and stream function are mentioned. They're provided by

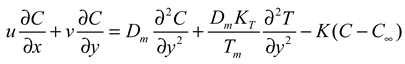

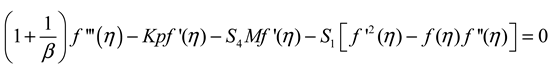

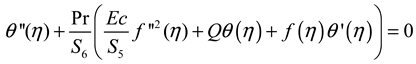

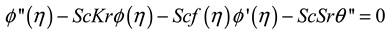

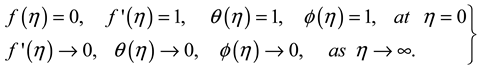

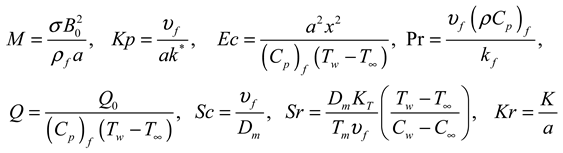

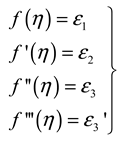

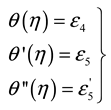

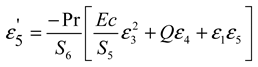

The transformed ordinary differential equations are:

where M denotes the magnetic parameter, Sc Schmidt number, Kp denotes the porosity parameter, Sr is the Soret effect parameter, Kr is the chemical reaction parameter, Pr represents Prandtl number, Eckert number is Ec, Q denotes heat source, where β is the Casson fluid parameter.

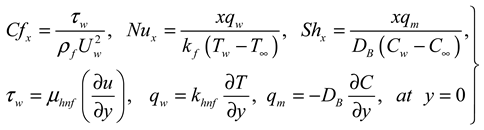

The Physical quatities of intrest are given below

Utilizing similarity transformation, we get

where Rex is a local Reynolds number, Cfx is skin friction co-effeciant, Nux is local Nussult number, and Shx is Sherwood number.

4. Result and Disscusion

In two cases, numerical solutions are computed, namely:

- (i)

MoS2 /Engine oil (simple nano lubricant) and

- (ii)

ZnO + MoS2 /Engine oil (hybrid nano lubricant).

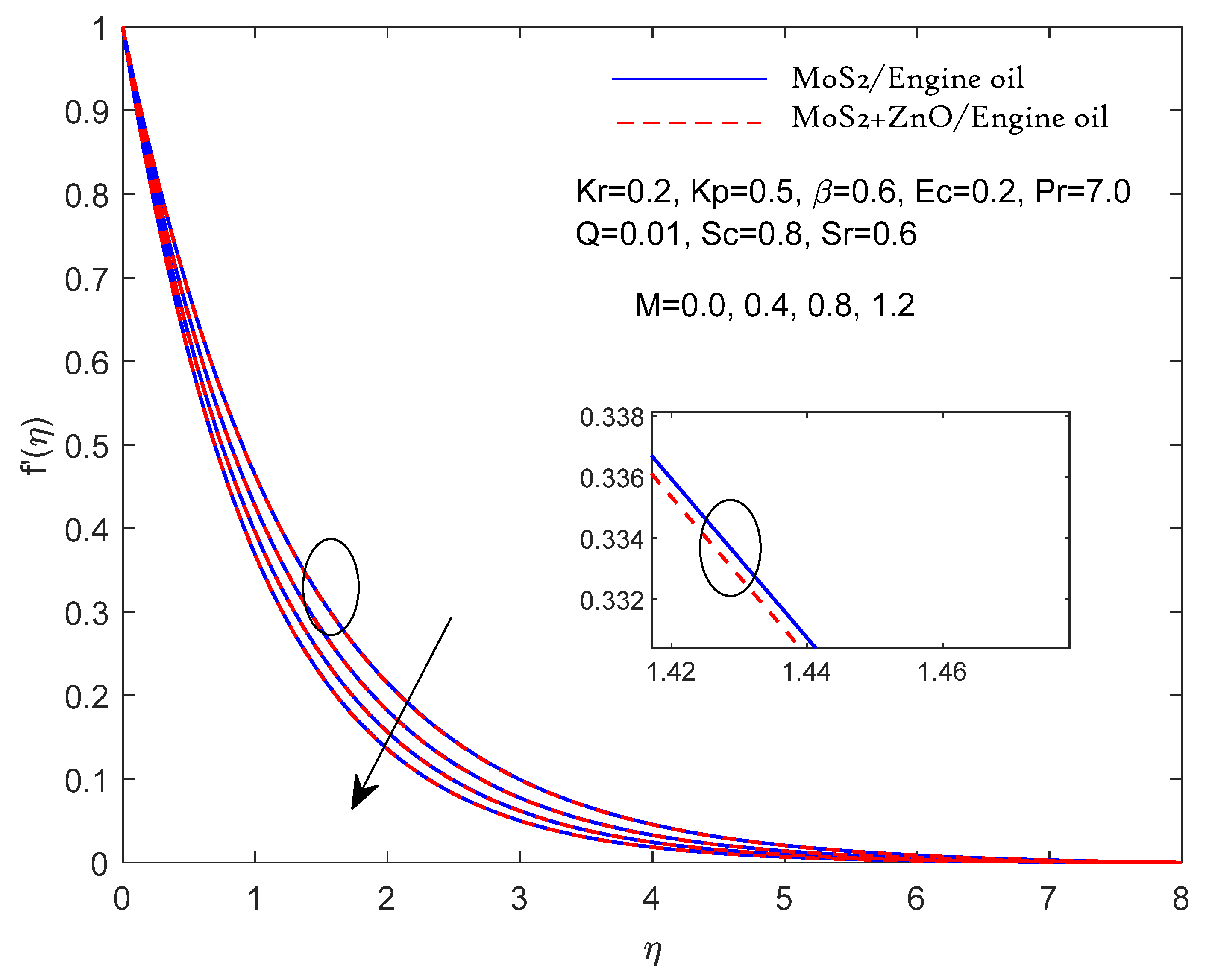

According to

Table 3, the above results can be verified if they compare reasonably with previous

Pr results in limiting cases. In

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12, two results are presented for single nano lubricant (MoS

2/Engine oils) and for hybrid nano lubricant (MoS

2/Engine oils + ZnO).

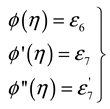

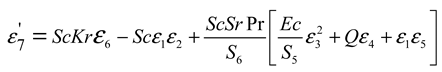

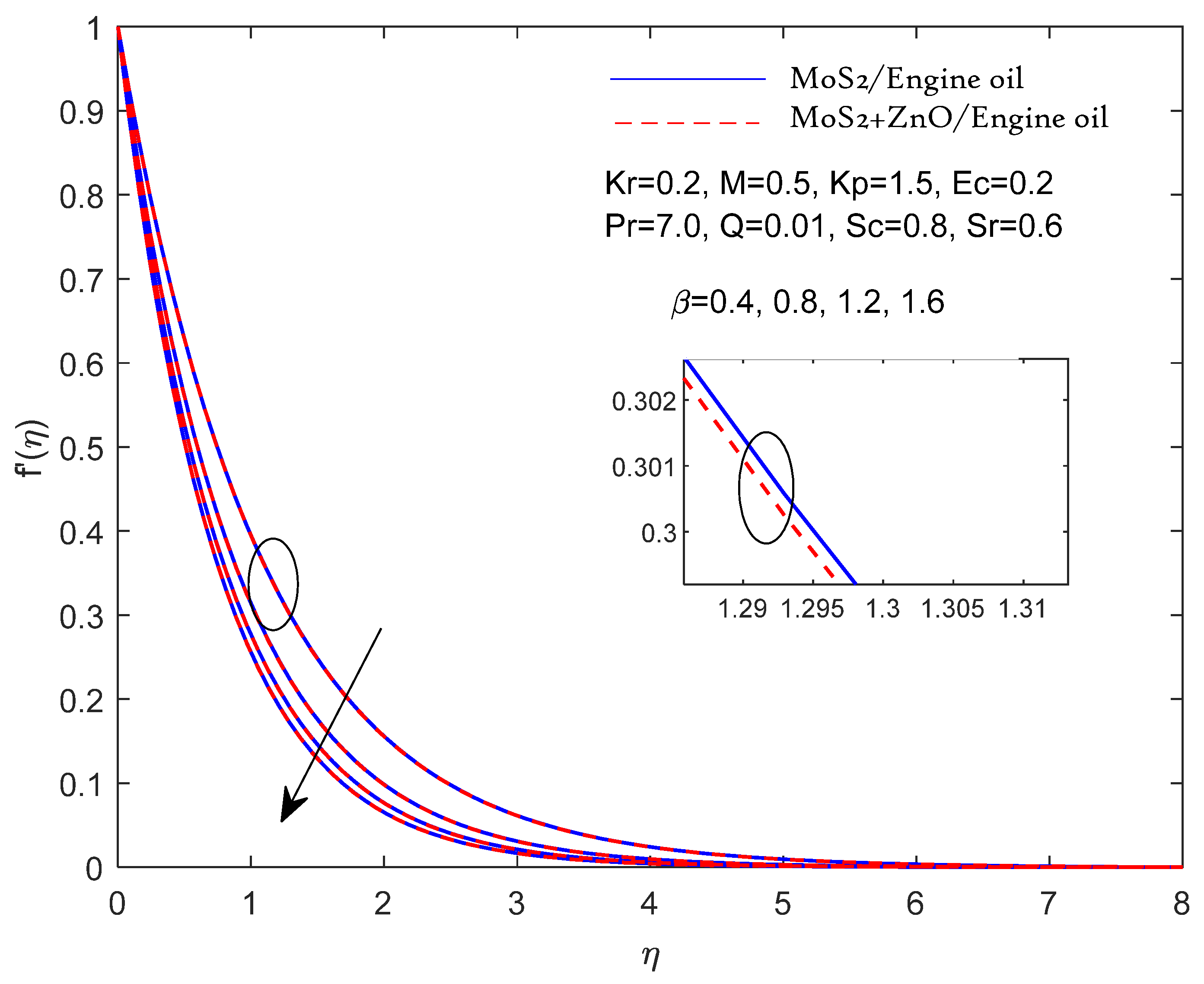

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 depicts the effects of magnetic characteristics parameters

M and porosity parameters

Kp on nondimensional horizontal velocity component f′ (η) respectively. Increasing these two parameters (

M and

Kp) dramatically slows down the flow of both nano lubricant (single nano lubricants as well as hybrid nano lubricants). According to physical principles, a larger value of

M indicates a greater Lorentz force opposing the flow. The parameter

Kp also corresponds to the lower porosity of the medium and higher resistance to flow with higher inputs.

Figure 4 represents the effect of the Casson lubricant parameter on the velocity. Rising Casson fluid parameter value decreases the velocity profile due to its shear-thinning property, hence, the wall thickness decreases.

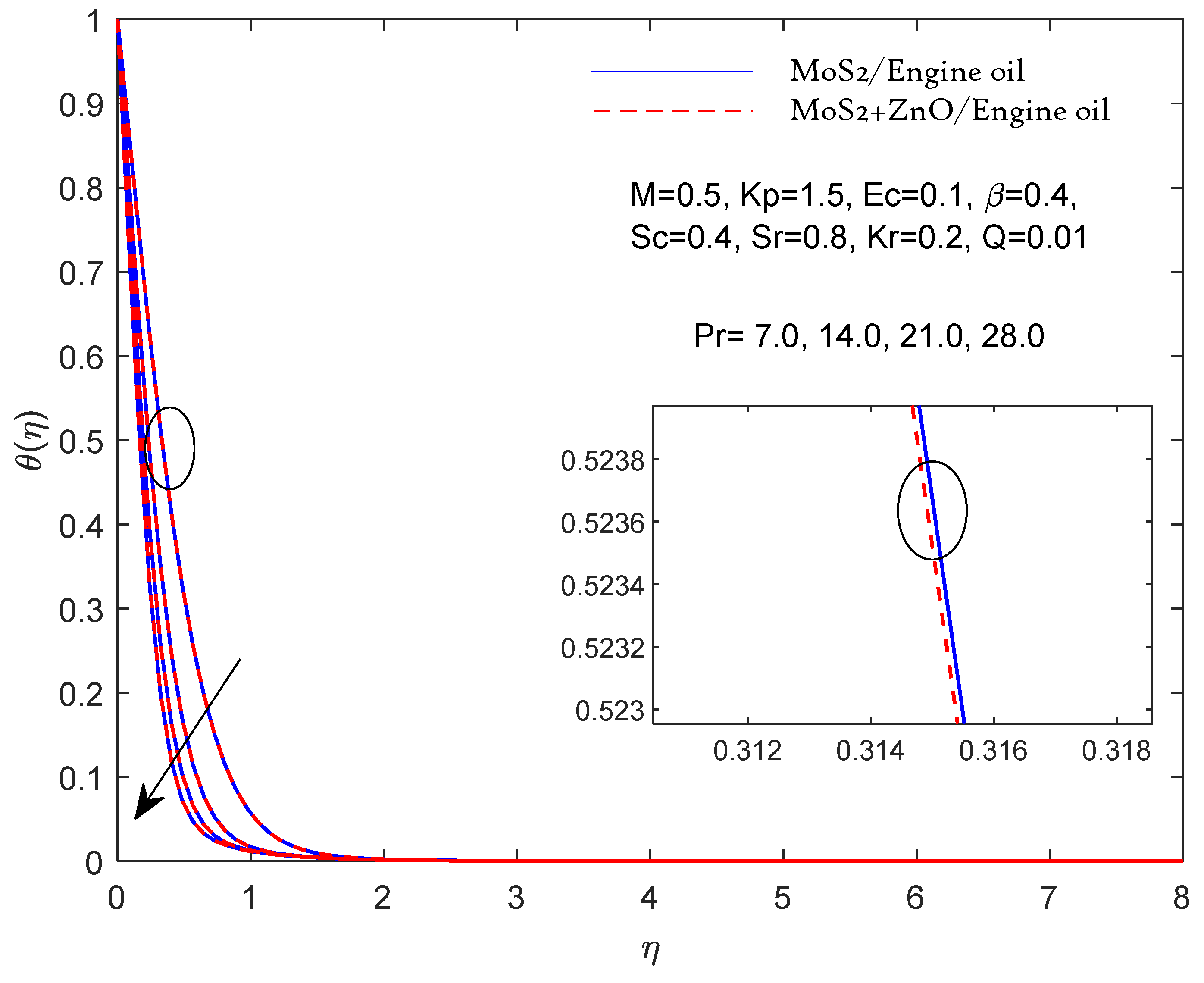

Figure 5 shows the results of the Prandtl number on the thermal profile. The value of

Pr increases temperature profile decreases. Hence Increasing Pr results in a decrease in the thermal diffusivity of the fluid, which further reduces the thickness of the thermal boundary layer. Furthermore, compared to the single nanofluid, the hybrid nanofluid's velocity has been observed to be slower.

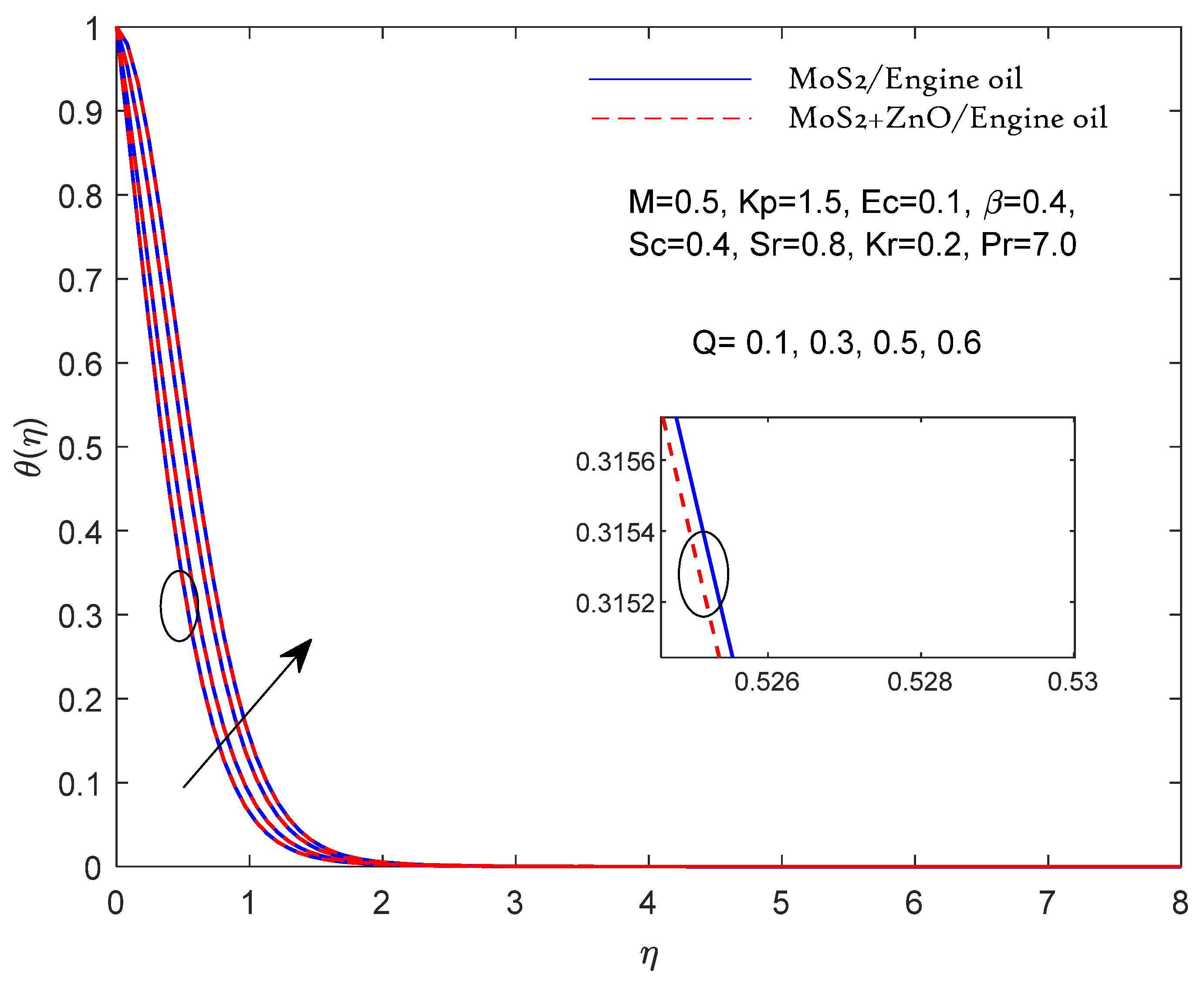

Figure 6 represents the effect of heat source parameter

Q on the temperature profile. Increases the temperature profile with increasing value of heat source parameter

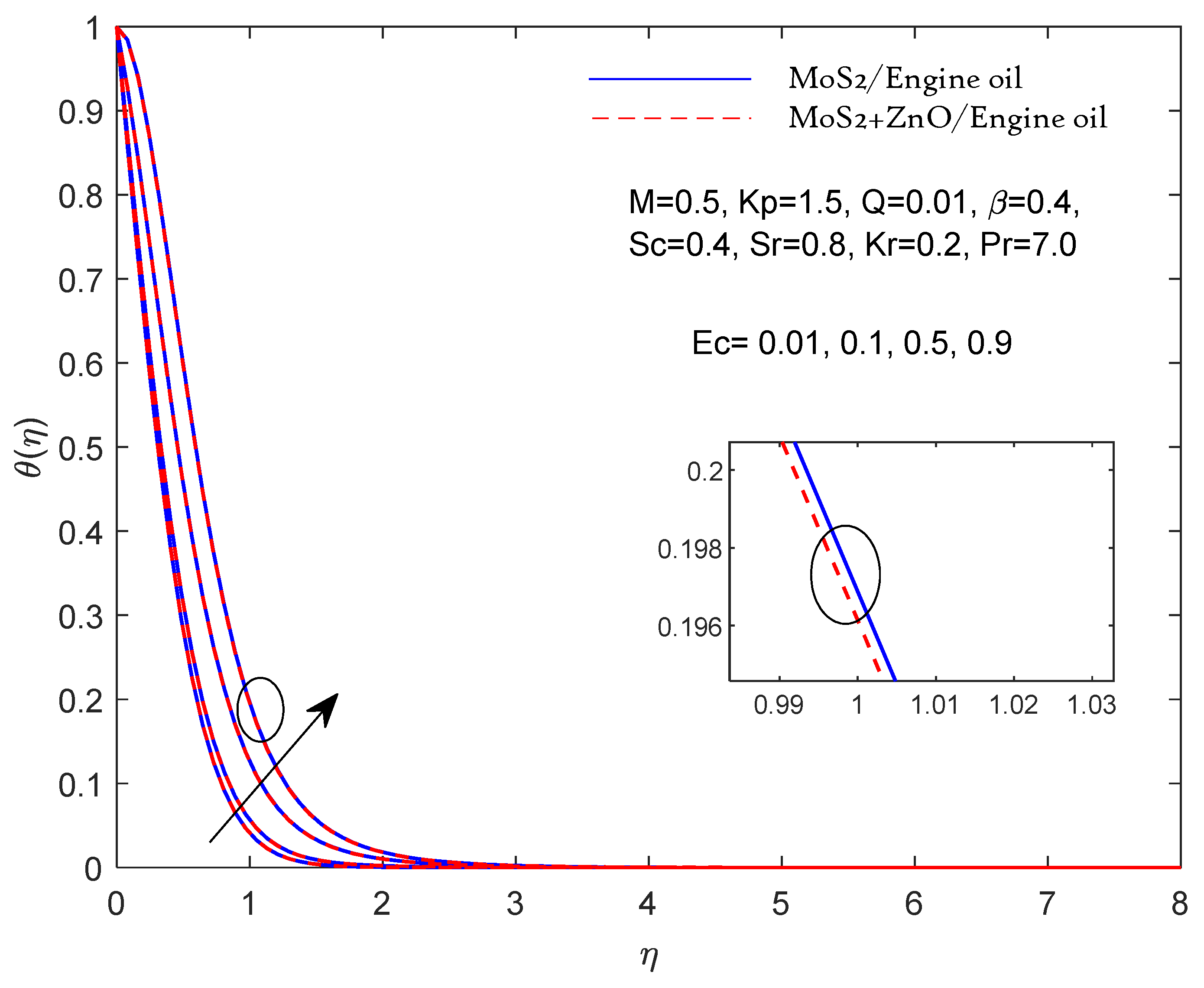

Q. Figure 7 represents the effect of Eckert number on the temperature profile. The temperature profile increases with the increasing value of

Ec. The conversion of mechanical energy to heat energy through thermal dissipation is represented by the greater Eckert number. Furthermore, it was noted that nanofluids have a higher temperature than other nanofluids. This is because hybrid nanofluids have higher thermal conductivities.

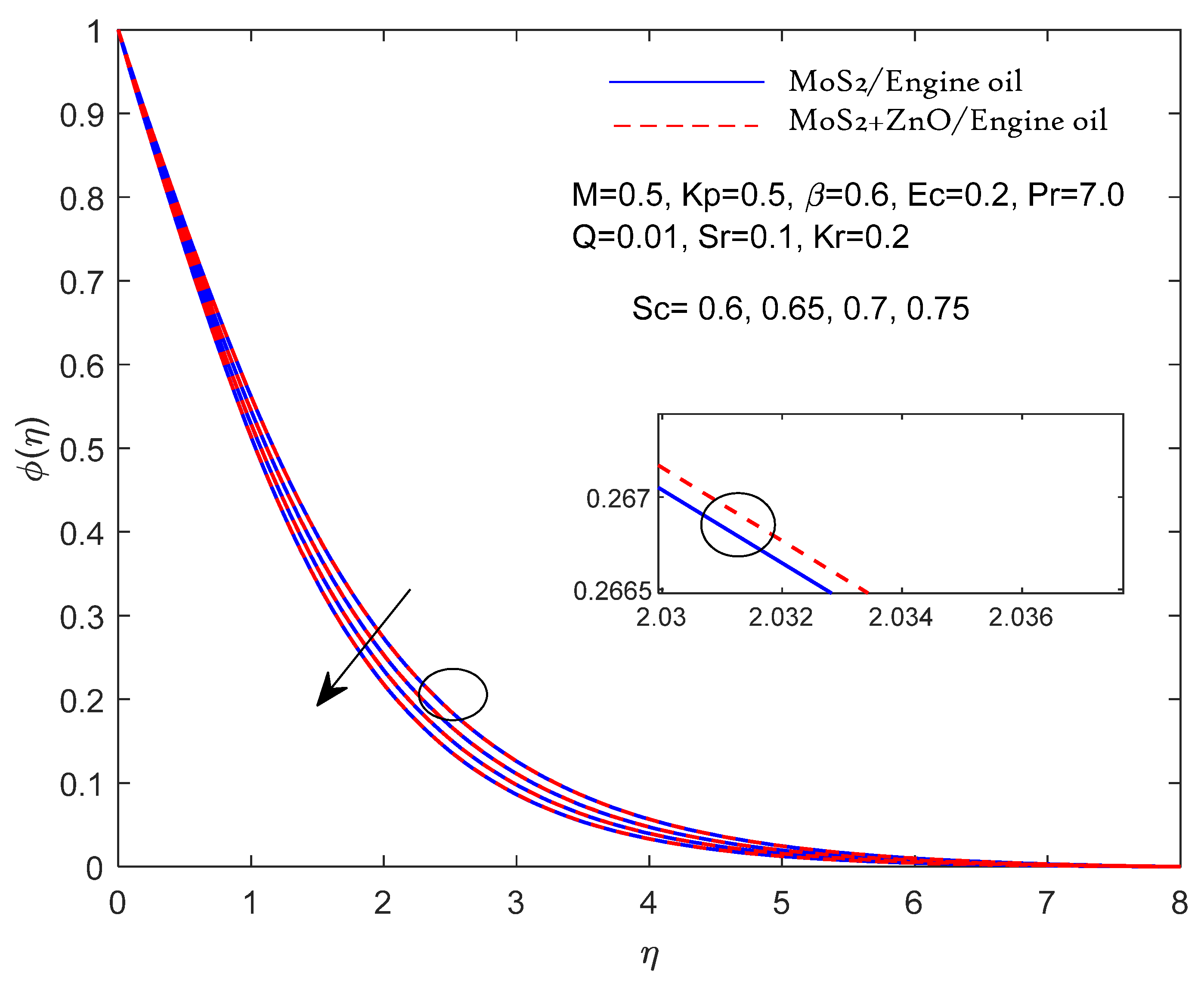

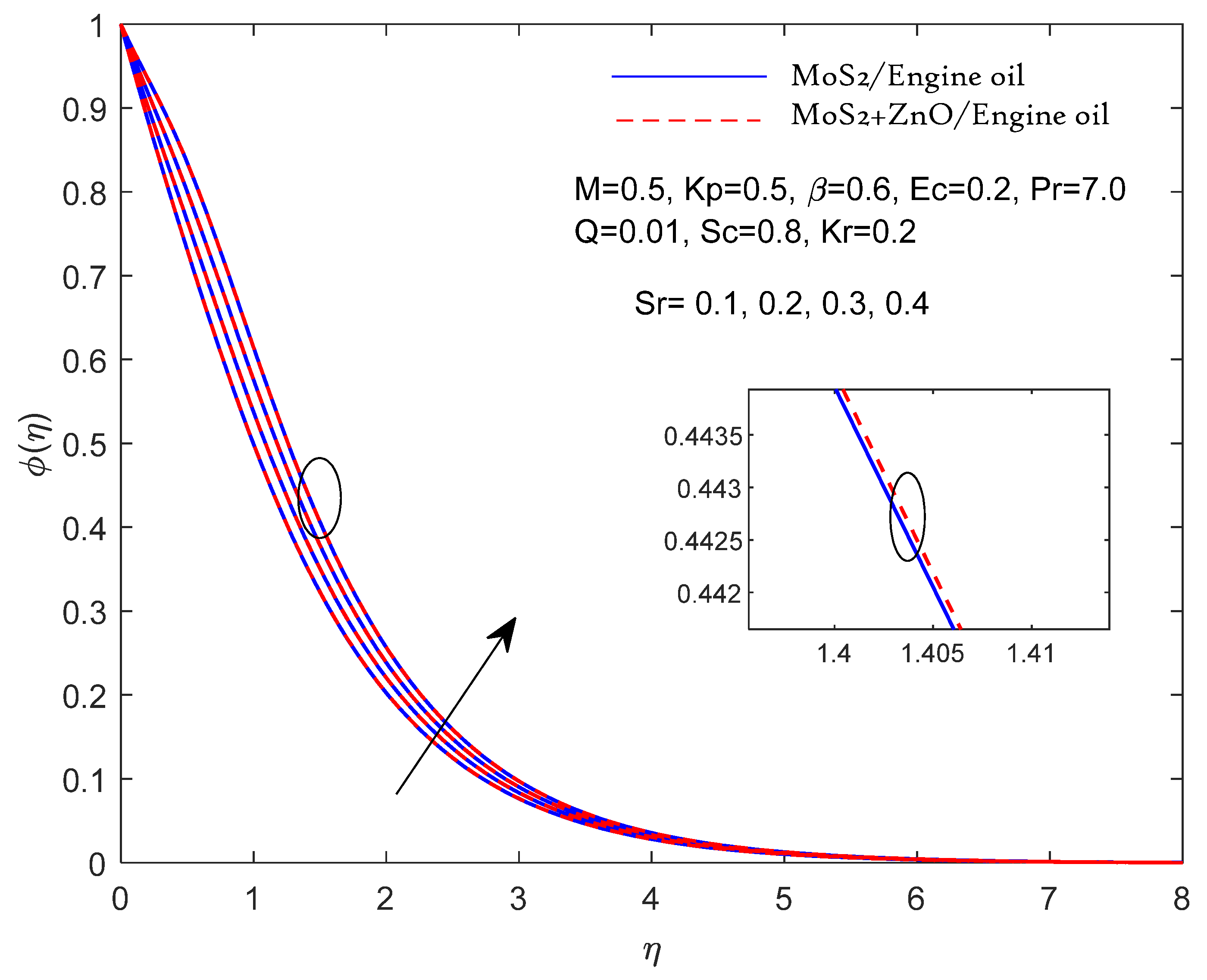

Figure 8 represents the effects of Schmidt number on the concentration profile. Increasing the value of the Schmidt number the concentration profile decreases.

Figure 9 shows the Soret effect on the concentration profile. Incremented Soret number increases the concentration profile, because the concentration is affected by the temperature gradient. Physically higher value of the Soret number corresponds to a higher temperature gradient which results in higher convection flow and hence the concentration profile increases.

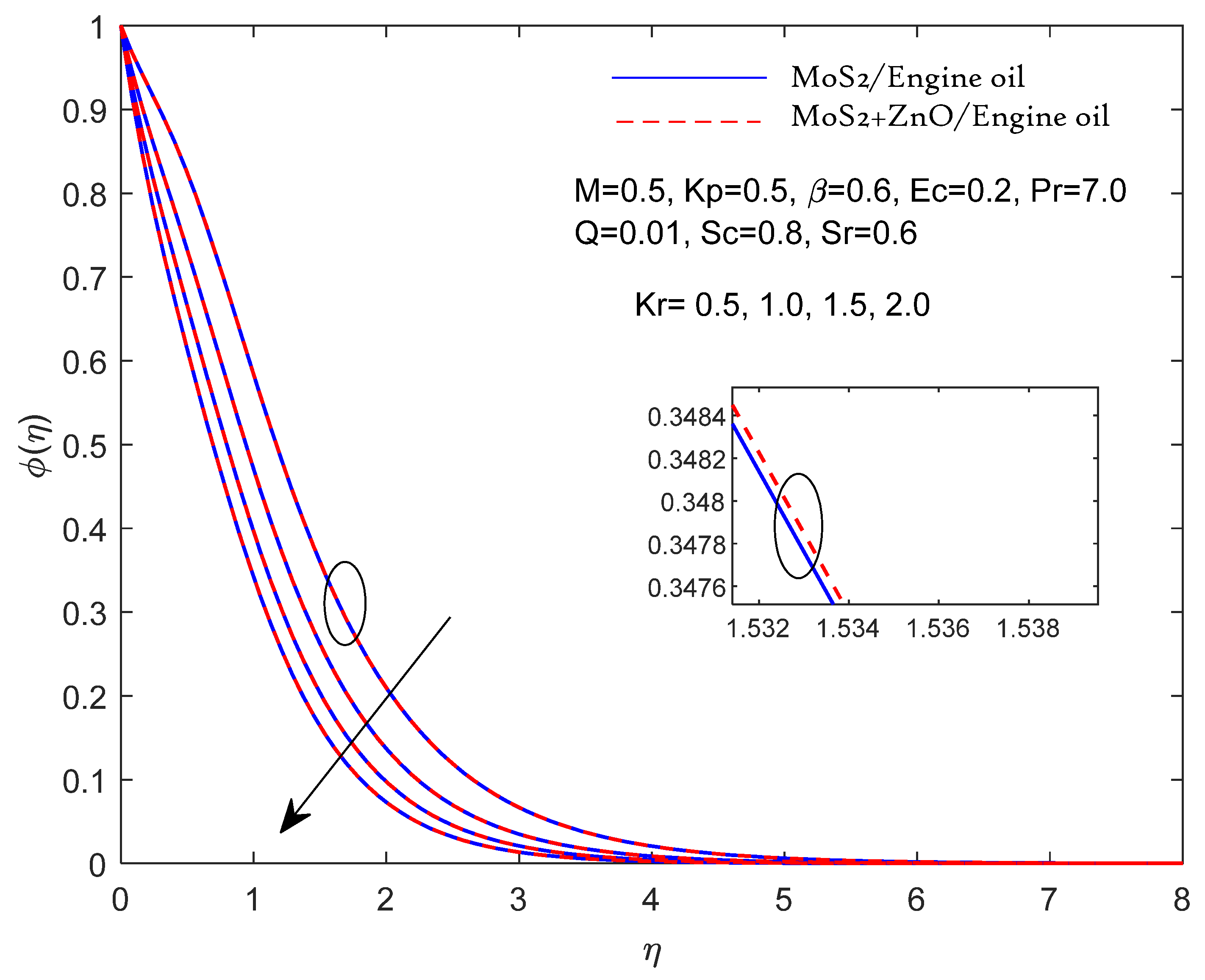

Figure 10 shows the chemical reaction (

Kr) on the concentration profile. Increasing the values of

Kr, decreases the concentration profile due to consumption character of this chemical reaction, hence concentration profile decreases.

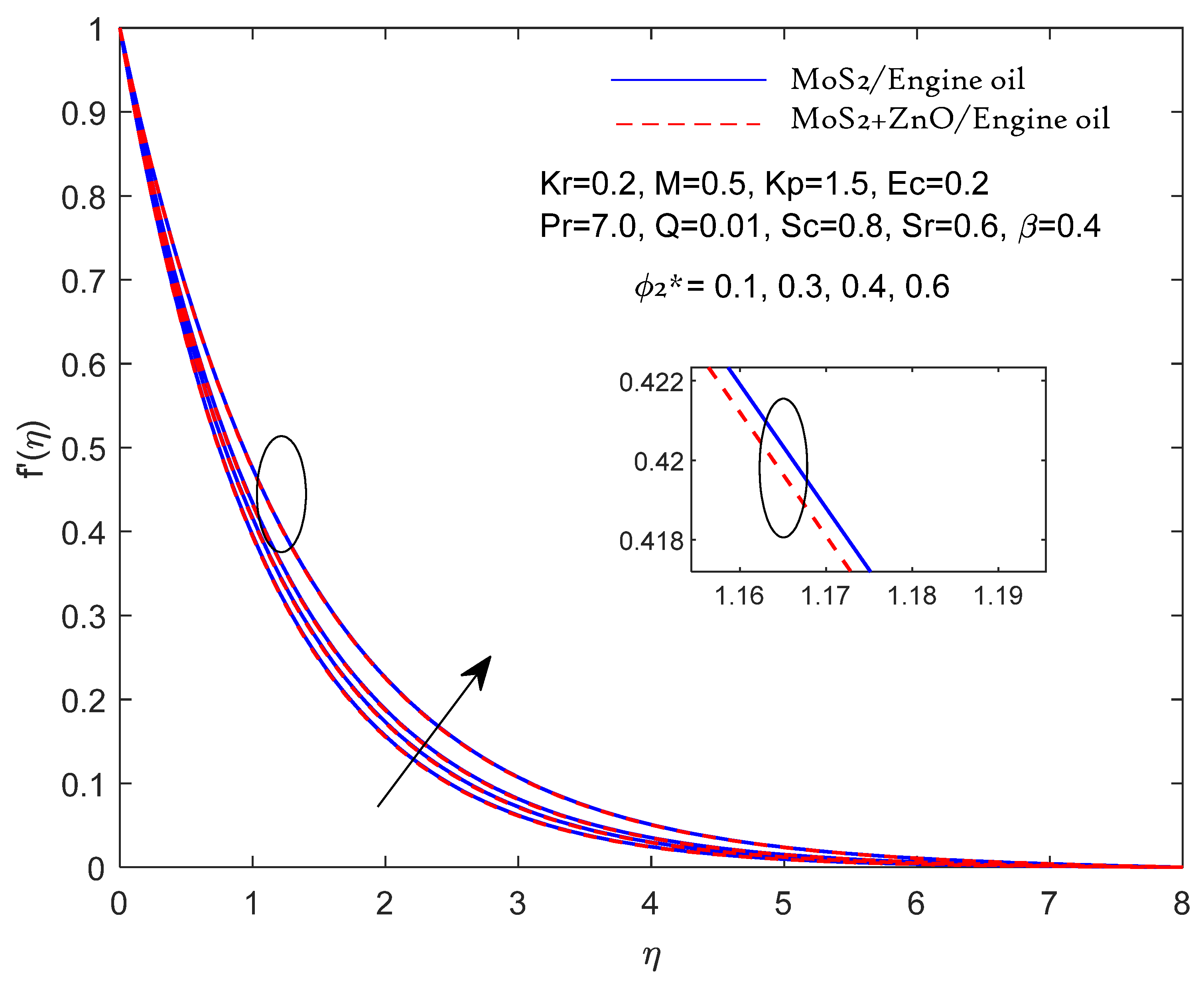

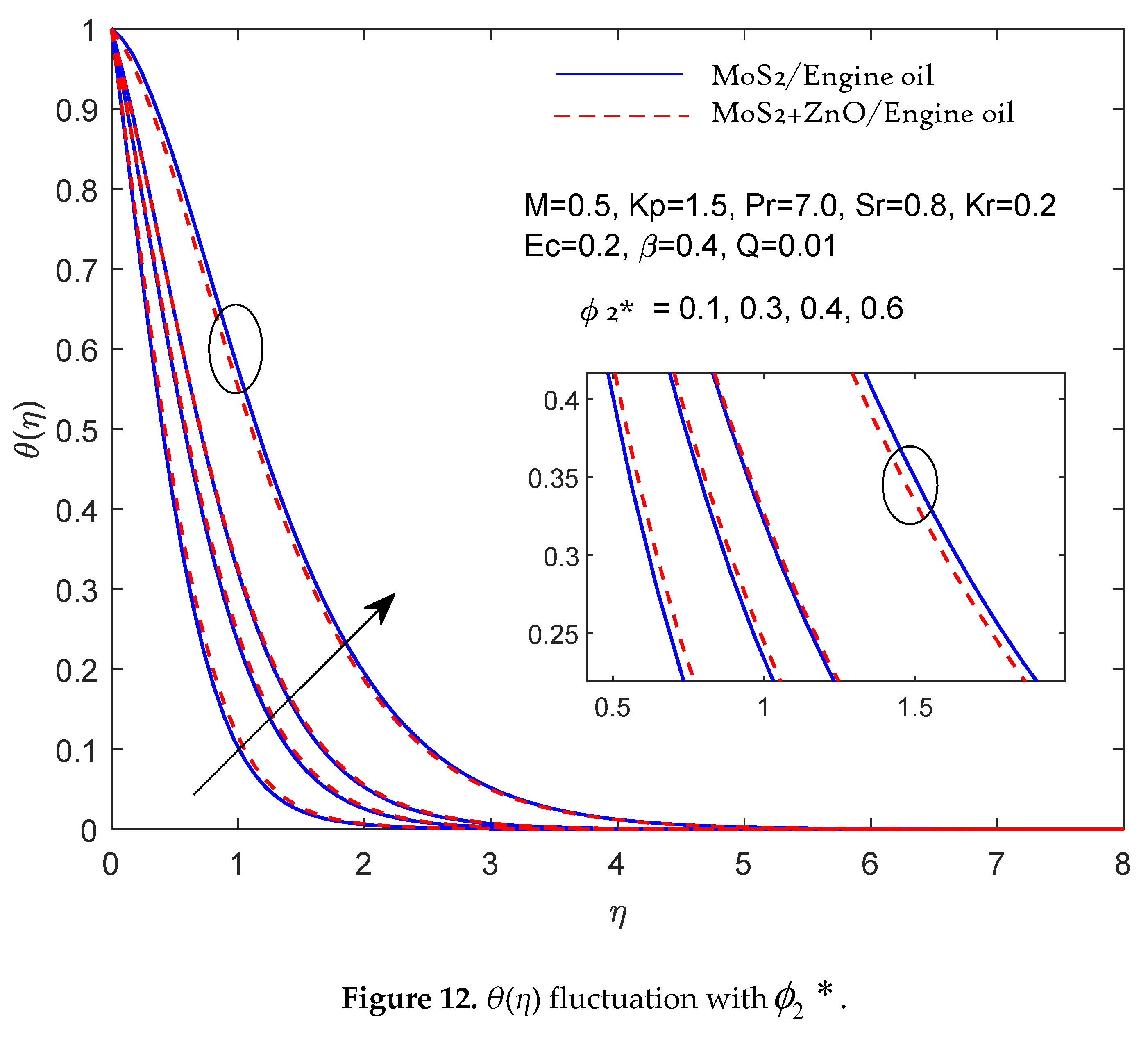

Figure 11 and

Figure 12. It is discovered that as augmentation occurs, the velocity

f’ (η) decreases.

and the temperature rises till

=0.4 but the temperature is slower with

>0.4 due to mass flux and thermal diffusion. The flow is being slowed down because of the viscosity, which is increases

and has the effect of slowing down the flow. Moreover,

Table 4 shows the skin fraction profile

- f′′ (0) results for the various inputs

M, Kp, and

β in ZnO + MoS

2/Engine oil (hybrid nanofluid) variation. It is seen that

M, Kp, and

β rise directly for the absolute values of

- f′′ (0) because the fluid flow slows down due to the conflicting forces of the electromagnetic interaction and the medium's porosity. The absolute value of the Nusselt number -

θ′ (0) increases with progressing values of

Pr,

Table 5 provides information about the Prandtl number

Pr. Also, it is noted that -

θ′(0) decreases reciprocally with Eckert number

Ec and heat source parameter

Q.

The value of Sherwood number

-ϕ′(0) increases with

Ec, Kr, and

Q are shown in

Table 6. It is also observed that -

ϕ′(0) decreases to

Pr, Sc, and

Sr.

Table 3.

Comparison of (-θ (0)) with the results of Asmat Ullah et al. [

13], Shami A.M. et al. [

14], and P. shreedevi et al. [

15], for various values of (Pr),

and

all r maining parameters zero.

Table 3.

Comparison of (-θ (0)) with the results of Asmat Ullah et al. [

13], Shami A.M. et al. [

14], and P. shreedevi et al. [

15], for various values of (Pr),

and

all r maining parameters zero.

| Pr |

Asmat Ullah et al. [13] |

Shami A.M. et al. [14] |

P. shreedevi et al. [15] |

Our results |

| 2.0 |

0.9112 |

0.91138 |

0.911341 |

0.911325 |

| 6.13 |

1.7597 |

1.75965 |

1.759676 |

1.759671 |

| 7.0 |

1.8953 |

1.8955 |

1.895397 |

1.895393 |

| 20.0 |

3.3540 |

- |

3.353915 |

3.353921 |

Table 4.

Results for Skin friction factor - f″ (η).

Table 4.

Results for Skin friction factor - f″ (η).

| M |

Kp |

β |

−f″(η)

|

| 0.0 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.7256 |

| 0.5 |

0.8227 |

| 1.0 |

0.9097 |

| 1.5 |

0.1 |

0.9191 |

| 0.3 |

0.9547 |

| 0.5 |

0.9889 |

| 0.5 |

0.1 |

0.5170 |

| 0.2 |

0.6993 |

| 0.3 |

0.8228 |

Table 5.

Results for Nusselt number - θ′ (η).

Table 5.

Results for Nusselt number - θ′ (η).

| Pr |

Q |

Ec |

−θ′(η)

|

| 7.0 |

0.01 |

0.1 |

1.5082 |

| 8.0 |

1.6176 |

| 10.0 |

1.8150 |

| 7.0 |

0.02 |

1.4899 |

| 0.05 |

1.4341 |

| 0.09 |

1.3574 |

| 0.01 |

0.15 |

1.3899 |

| 0.2 |

1.2715 |

| 0.25 |

1.1532 |

Table 6.

Results for Sherwood number −ϕ′(η).

Table 6.

Results for Sherwood number −ϕ′(η).

| Pr |

Ec |

Sc |

Sr |

Kr |

Q |

−ϕ′(η) |

| 6.3 |

0.1 |

0.4 |

0.8 |

0.2 |

0.01 |

0.0643 |

| 7.0 |

0.0396 |

| 7.5 |

0.0227 |

| 7.0 |

0.2 |

0.1128 |

| 0.25 |

0.1494 |

| 0.3 |

0.1860 |

| 0.1 |

2.5 |

0.0735 |

| 3.0 |

0.0624 |

| 3.5 |

0.0511 |

| 0.4 |

0.5 |

0.1848 |

| 0.6 |

0.1364 |

| 0.7 |

0.0880 |

| 0.8 |

0.3 |

0.1002 |

| 0.4 |

0.1541 |

| 0.5 |

0.2031 |

0.2 |

0.02 |

0.0453 |

| 0.04 |

0.0568 |

| 0.06 |

0.0685 |

Figure 2.

Velocity f′ (η) fluctuation with M.

Figure 2.

Velocity f′ (η) fluctuation with M.

Figure 3.

Velocity f′ (η) fluctuation with Kp.

Figure 3.

Velocity f′ (η) fluctuation with Kp.

Figure 4.

Velocity f′ (η) fluctuation with β.

Figure 4.

Velocity f′ (η) fluctuation with β.

Figure 5.

θ(η) fluctuation with Pr.

Figure 5.

θ(η) fluctuation with Pr.

Figure 6.

θ(η) fluctuation with Q.

Figure 6.

θ(η) fluctuation with Q.

Figure 7.

θ(η) fluctuation with Ec.

Figure 7.

θ(η) fluctuation with Ec.

Figure 8.

fluctuation with Sc.

Figure 8.

fluctuation with Sc.

Figure 9.

fluctuation with Sr.

Figure 9.

fluctuation with Sr.

Figure 10.

fluctuation with Kr.

Figure 10.

fluctuation with Kr.

Figure 11.

Velocity f′ (η) fluctuation with .

Figure 11.

Velocity f′ (η) fluctuation with .

Figure 12.

θ(η) fluctuation with .

Figure 12.

θ(η) fluctuation with .