Submitted:

19 April 2024

Posted:

23 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Results and Discussion

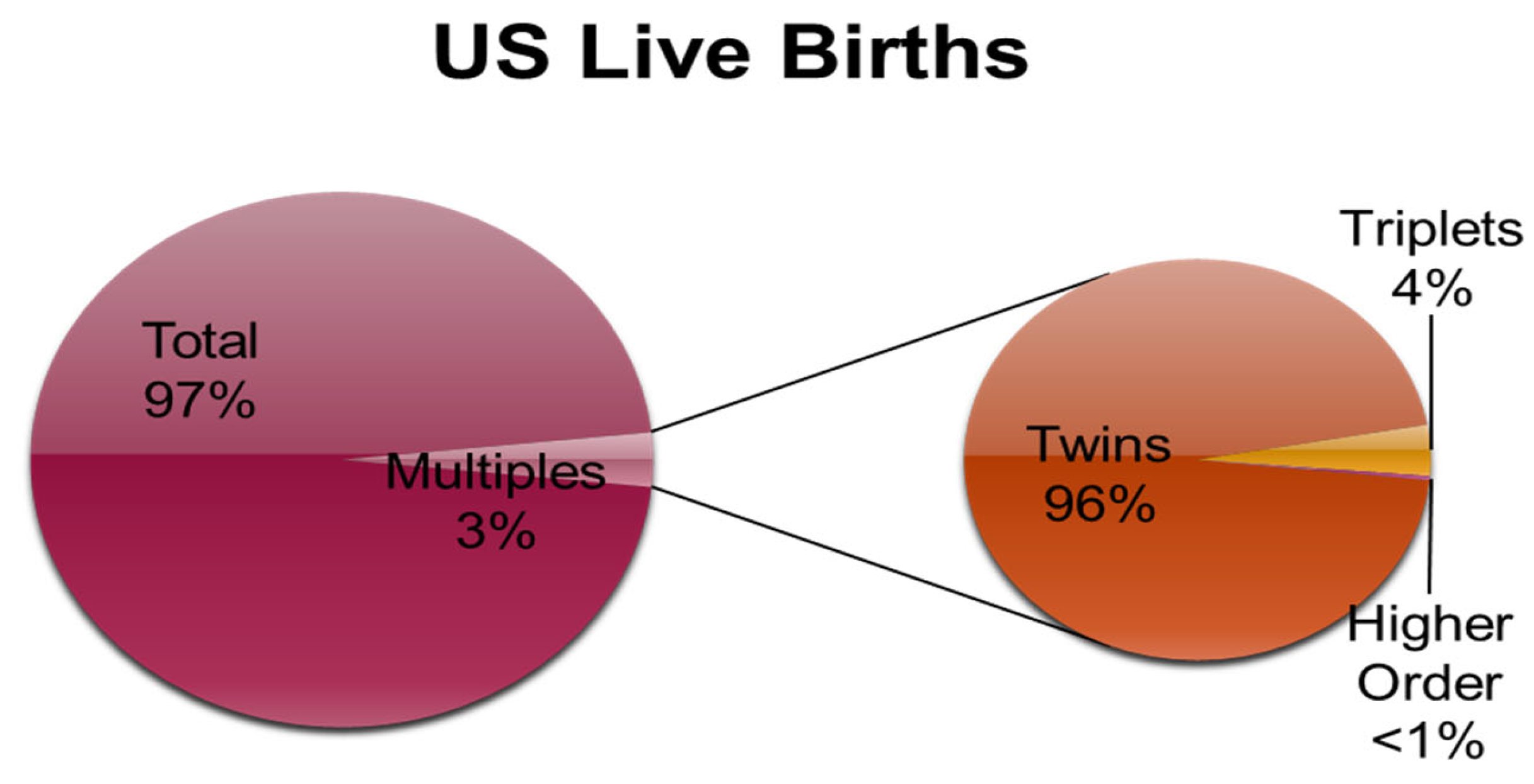

1. Multiple Pregnancy:

1.1. Biology of Twinning

1.2. Vanishing Twin Syndrome

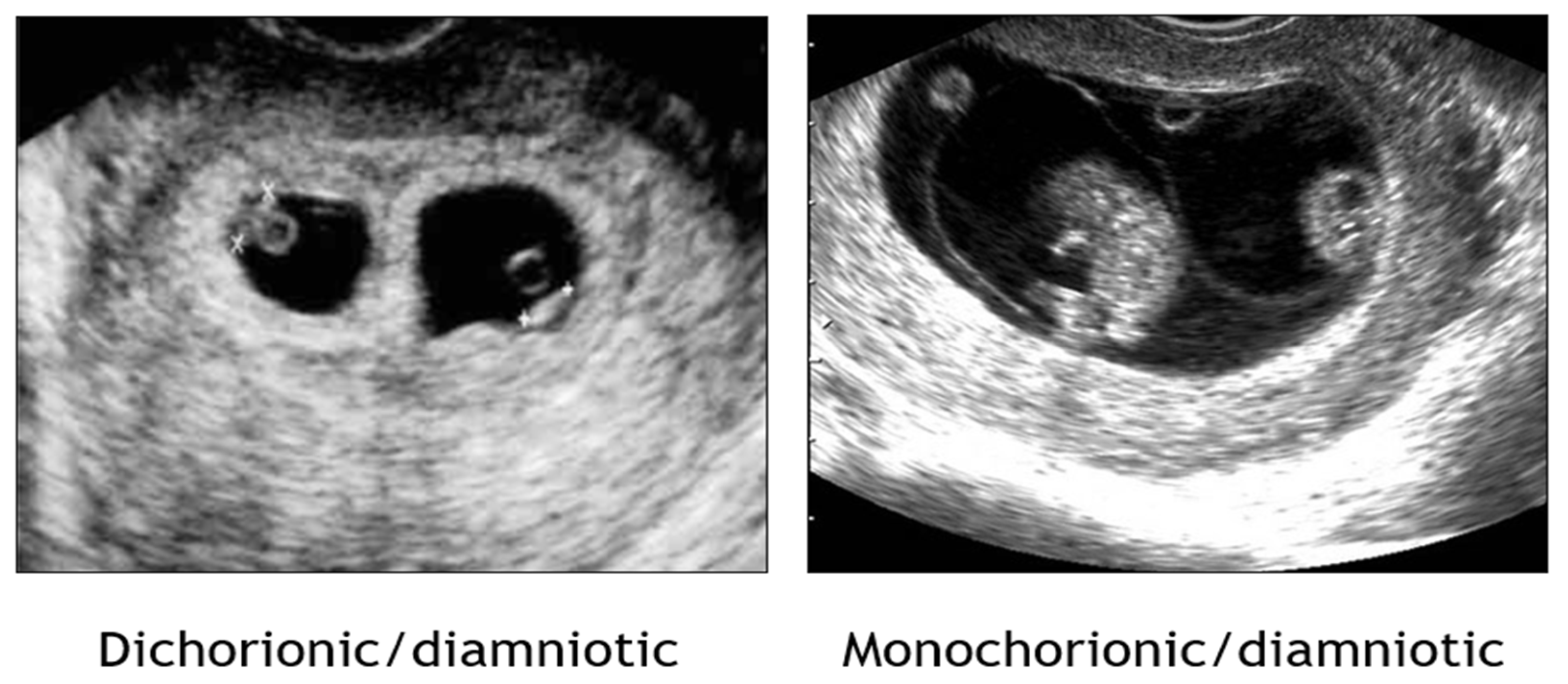

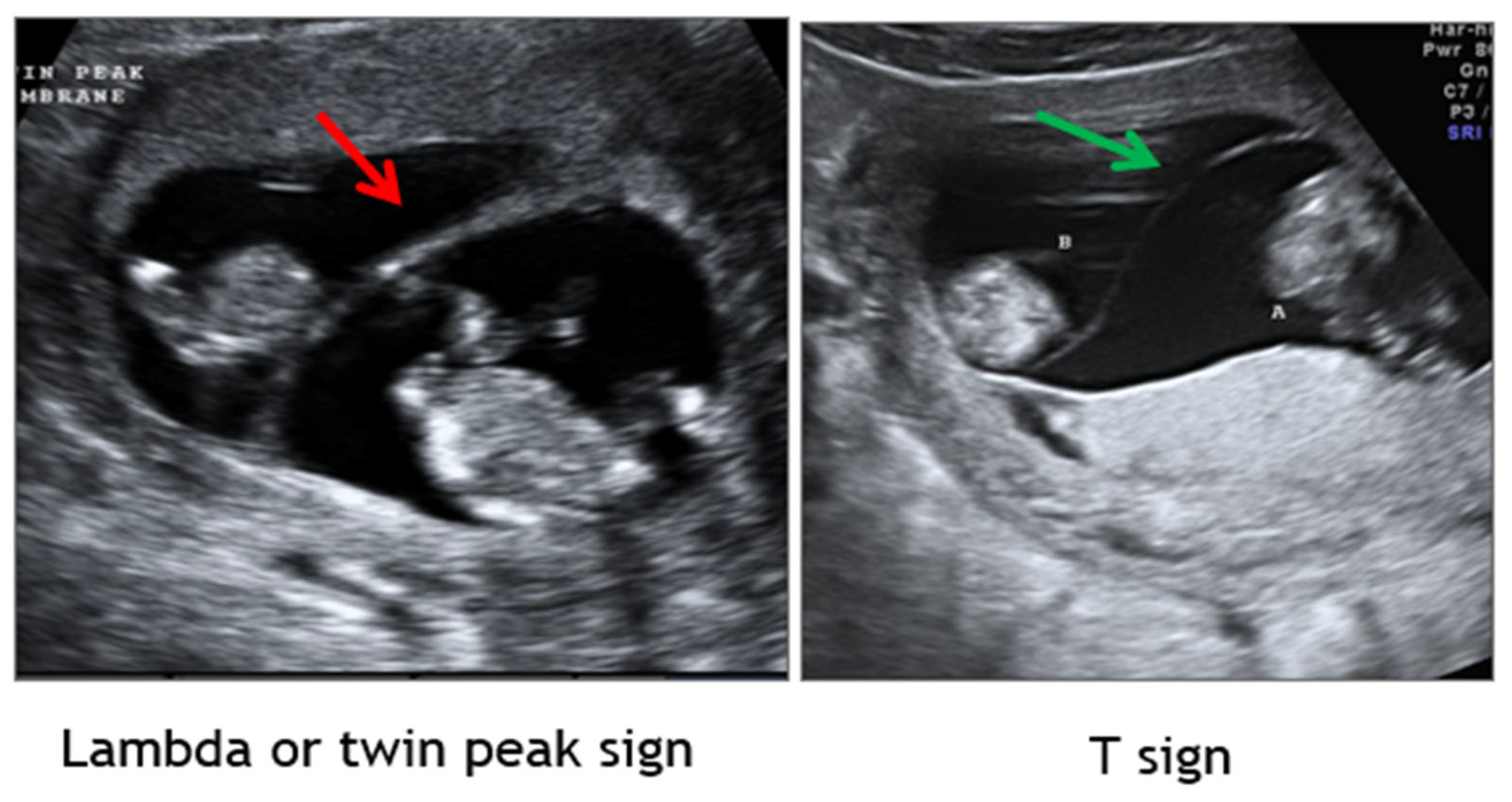

1.2. Establishment of Chorionicity and Amnionicity

2. Genetic Screening and Testing in Multiples

2.1. Screening

2.2. Diagnostic Testing

3. Nutrition, Maternal Activity, and Exercise in Multiple Gestation

4. Antepartum Twin Management: Surveillance of Growth and Fetal Status

4.1. Fetal Growth Restriction in Multiples & Delphi Procedure

4.2. Dichorionic Diamniotic Twins

4.3. Monochorionic Diamniotic Twins

4.4. Commentary on TTTS and Staging

4.5. Commentary on TAPS

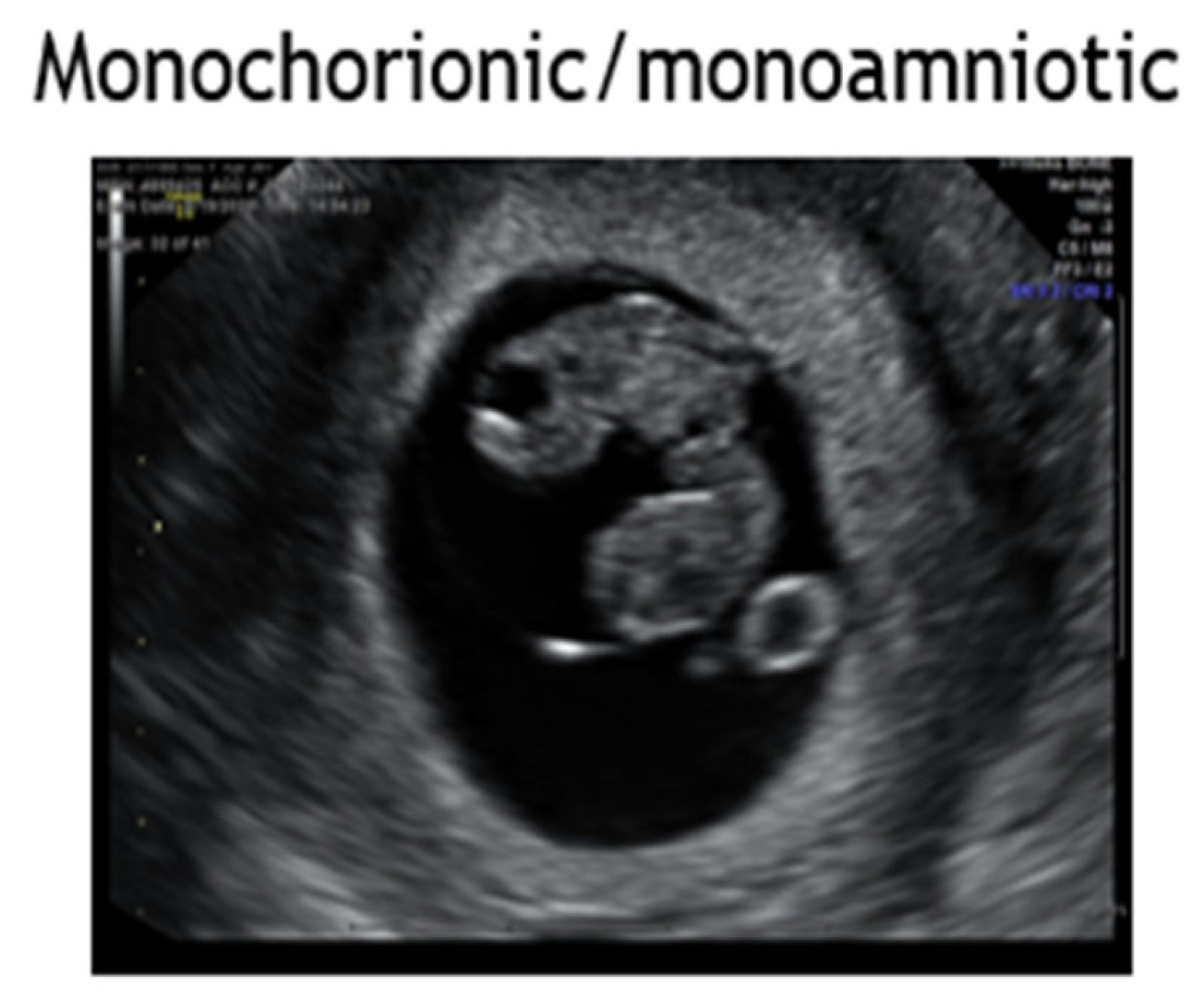

4.6. Monochorionic Monoamniotic Twins

4.6. Twin Reversed Arterial Perfusion

5. Conjoined Twins

6. High Order Multiples

7. Maternal Considerations in Multiples

7.1. Anemia in Twin Pregnancy

7.2. Hypertension in Twin/Multiple Pregnancy

7.3. Diabetes and Gestational Diabetes in Twin/Multiple Pregnancy:

8. Prevention of Preterm Birth in Twins and Multiples

8.1. Infections

8.2. Cervical shortening

8.3. Cervical insufficiency

8.4. fFN and Preterm Labor

9. Intrapartum Management of Multifetal Pregnancies: Delivery and Mode

9. Delayed Interval Delivery of the Second Twin

Key Updates, Recommendation Summary & Concluding Remarks

- Supplement folate pre- and periconception [Level Ia; A];

- Supplement iron and folate in the mid- and late trimesters [Level IIb; B].

- First trimester ultrasound remains paramount in discerning chorionicity in twins and high order multiple gestations [Level II-2A; B].

- Multiple marker screening by either first trimester screen or second trimester Maternal Serum Screen must be interpreted with caution as altered serum levels generated by an abnormal fetus may be “normalized” by the other twin. Serum screening is never valid in triplets or other higher order pregnancies [Level II; B].

- Each amniotic sac should be sampled in a diagnostic amniocentesis of multiple gestation except with a monochorionic twin pair in that monochorionicity was confirmed in the first trimester and growth is concordant. [Level II2b; B].

- In multiple gestations, women should increase their daily intake by 300 calories/fetus in the first trimester, 340 calories/fetus in the second trimester, and 452 calories/fetus in the third trimester [Level IV; C].

- Iron-rich diet in addition to the prenatal vitamin may be beneficial [Level Ib; A].

- Patients with twins/multiples should be advised to consume >=100gm protein daily [Level IV; C].

- Fetal fibronectin in setting of threatened preterm labor remains of high negative predictive value (~97%) for delivery within 2 weeks of sampling [Level IIb; B].

-

Cervical length monitoring is of limited utility in twin/multiple gestation:

- ○

- Cervical cerclage has not been demonstrated to be of benefit for either history-based (prophylactic) or short cervix on ultrasound (ultrasound-indicated) and may pose risk of increased preterm delivery in twins and/or multiples [Level IIa/b; B].

- ○

- Vaginal progesterone for treatment of short cervix has not been demonstrated to be of clear benefit in twins and multiple gestation [Level IIa; B].

- Of twins with imminent risk for preterm birth for any indication from 23-34 weeks’ gestational age, antenatal corticosteroids are well-established as beneficial to reduce fetal morbidity and mortality [Level 1b; A].

- Serial growth evaluation by ultrasound biometry is essential for management of all twin and multiple gestations given risk for fetal growth restriction and discordant twin pairs [Level III; B].

- Discordant twin pairs should receive antenatal testing until delivery, noting timing of delivery should be based on UA Doppler studies (when indicated for FGR), antenatal testing results, and other medical indications as appropriate for that comorbidity (eg, preeclampsia, diabetes, hypertensive disorders, renal disease) [Level III; B].

- Monochorionic twin pregnancies are at risk for TTTS and as such are recommended to have limited ultrasounds biweekly (ever 2 weeks) in the mid- and late-trimesters from 16 weeks to delivery along with antenatal testing beginning at 32 weeks until delivery [Level III; B].

- TTTS complicates 10-15% of monochorionic twin gestations [Level II; B]

- Identification of twin pairs affected by TTTS, Twin Reverse Arterial Perfusion (TRAP), Twin Anemia Polycythemia Sequence (TAPS), and selected fetal growth restriction is best for outcomes when identified early in onset to facilitate appropriate evaluation, surveillance, and referral when clinically appropriate [Level IV; C].

- Untreated TTTS is associated with fetal mortality of 60-100% [Level II; B]

- The Eurofetus study demonstrated that fetoscopic laser surgery generates more favorable outcomes compared to serial amnioreduction for TTTS when apparent as a stage II case between 16-26 weeks’ gestational age (66% vs. 57%); [Level II; B].

- Intrapartum monitoring should be continuous in multiple gestation; [Level III; B].

- Data indicate uncomplicated monochorionic-diamniotic twin pregnancies should be delivered at 37 weeks if not indicated sooner [Level III; B].

- Evidence supports delivery of monoamniotic twin pairs at 32-34 weeks by cesarean delivery given risk for stillbirth and inter-locking twins in parturition [Level III; B].

- Stillbirth rate of uncomplicated DC twins at 38 weeks matches singleton stillbirth rate at 42 weeks. Hence, delivery of uncomplicated dichorionic twins appears to be best-timed for 38 weeks, with some experts suggesting delivery at 37 weeks or shortly thereafter (by 38 weeks) [Level III; B].

- There appears to be unnecessary risk of prematurity when delivering uncomplicated DC twins prior to 36 weeks completed gestational age [Level III; B].

- Delivery of uncomplicated triplets is generally recommended by 35 weeks by cesarean except in the instance of an obstetrician experienced with vaginal delivery and the patient has been counseled appropriately regarding risks [level IIb, B].

- Delayed interval delivery may be considered in periviable or severely preterm pregnancies, noting monochorionicity, chorioamnionitis, preeclampsia and abruption are representations of many potential contraindications [Level IIb; B].

- Oxytocin infusion prophylactically in the third stage of labor to prevent postpartum hemorrhage [Level Ia; A].

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFI Amniotic Fluid Index |

| AFP Alphafeto Protein |

| BPP Biophysical Profile |

| CRL Crown Rump Length |

| DC Dichorionic |

| Di-Di Dichorionic Diamniotic |

| EFW Estimated Fetal Weight |

| FD Fetal Demise |

| FGR Fetal Growth Restriction |

| FSH Follicle Stimulating Hormone |

| HCG Human Chorionic Gonadotropin |

| LMP Last Menstrual Period |

| MC Monochorionic |

| MCA Middle Cerebral Artery |

| Mo-Di Monochorionic Diamniotic |

| Mo-Mo Monochorionic Monoamniotic |

| NST Nonstress Test |

| NT Nuchal Translucency |

| ONTD Open Neural Tube Defects |

| PAPP-A Pregnancy Associated Plasma Protein-A |

| PI Pulsatility Index |

| PSV Peak Systolic Velocity |

| RCT Randomized Controlled Trial |

| sFGR Selective Fetal Growth Restriction |

| SFLP Selective Fetoscopic Laser Photocoagulation |

| T21 Trisomy 21 |

| TAPS Twin Anemia-Polycythemia Sequence |

| tFF Total Fetal Fraction |

| TRAP Twin Reverse Arterial Perfusion |

| TTTS Twin-Twin Transfusion Syndrome |

| TTTS Twin-Twin Transfusion Syndrome |

| UA Umbilical Artery |

| USPSTF United States Preventative Services Task Force |

References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Interim Update Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician – Gynecologists Multifetal Gestations: Twin, Triplet, and Higher-Order Multifetal Pregnancies. Obstet & Gynecol. 2021, 137(169), 1140–43. [Review Level IV; C].

- Oepkes, D.; Sueters, M. Antenatal Fetal Surveillance in Multiple Pregnancies. Best Practice and Research: Clin Obstet and Gynaecol. 2017, 38, 59–70. [Review Level IV; C]. [CrossRef]

- Owen, D.; Wood, L.; and Neilson, J. Antenatal Care for Women with Multiple Pregnancies: The Liverpool Approach. Clin Obstet and Gynecol. 2004, 47, 263–271, [Review IV; C]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Audibert, F.; Gagnon, A. No. 262-Prenatal Screening for and Diagnosis of Aneuploidy in Twin Pregnancies. J Obstet and Gynaecol Canada 2017, 39, e347–e361, [Review IV; C]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, J.; Torloni, M.; Seuc, A.; Betran, A.; Widmer, M.; Souza, J.; Merialdi, M. Maternal and Perinatal Outcomes of Twin Pregnancy in 23 Low- and Middle-Income Countries. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 1–17, [WHOGS dataset n=276,187 singletons and n= 6476 twins; observational case-control; Level IIB; B]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.; Sairam, S.; Shehata, H. Obstetric Complications of Twin Pregnancies. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2004, 18, 557–576, [Review; Level IV; C]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, F.; D’Alton, M. Multiple Gestation: Clinical Characteristics and Management. In Creasy and Resnik’s Maternal-fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice, 8th ed.; Lockwood, C., Moore, T., Copel, J., Silver, R., Resnik, R., Dugoff, L., Louis, J.; Elsevier, 2018; pp. 660-686. [Review; Level IV; C].

- Gezer, A.; Rashidova, M.; Güralp, O.; Öçer, F. Perinatal mortality and morbidity in twin pregnancies: The relation between chorionicity and gestational age at birth. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2012, 285, 353–360, [Retrospective cohort/descriptive study; n=484 twin births; Level III]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, D.S.; Surita, F.G.; Cecatti, J.G. Multiple Pregnancy: Epidemiology and Association with Maternal and Perinatal Morbidity. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2018, 40, 554–562, [Review; Level IV; C]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health (UK). Multiple Pregnancy: The Management of Twin and Triplet Pregnancies in the Antenatal Period. London: RCOG Press; 2011, revised 2019. (NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 129). [RCOG Review; Level IV;C].

- Osterman M, Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Driscoll AK, Valenzuela CP, Division of Vital Statistics. Births: Final Data for 2021. National Vital Statistics Reports, 2023; 72:1:1-53. [Descriptive observational cohort; n=3,664,292 US births; Level III;B].

- McNamara, H.C.; Kane, S.C.; Craig, J.M.; Short, R.V.; Umstad, M.P. A review of the mechanisms and evidence for typical and atypical twinning. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016, 214, 172–191, [Review; Level IV; C]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, AL. 1931-1971: a critical review, with particular reference to the medical profession. In: Medicines for the Year 2000. Office to Health Economics; London: 1979:1-11. [Review; Level IV;C].

- Ranson SB, Studdert DM, Dombrowski MP, Mello MM, Brennan TA. Reduced medico-legal risk by compliance with obstetric clinical pathways: a case-control study. Obstet Gyncol 2003; 101:751-5. [Level IIb; B]. [CrossRef]

- Mogollon F, Casas-Vargas A, Rodriguez F, Usaquen W. Twins from different fathers: A heteropaternal superfecundation case report in Colombia. Biomedica. 2020; 40:4:604-608. [Case report, n= 1; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Hirshberg, A.; Dugoff, L. First-Trimester Ultrasound and Aneuploidy Screening in Multifetal Pregnancies. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 2015, 58(3), 559–73. [Review; Level IV; C]. [CrossRef]

- Maruotti, G.M.; Saccone, G.; Morlando, M.; Martinelli, P. First-trimester ultrasound determination of chorionicity in twin gestations using the lambda sign: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016, 202, 66-70. [Meta-analysis of twins, n=2292 from 9 studies; Level IIb; B]. [CrossRef]

- Sperling, L.; Tabor, A. Twin pregnancy: The role of ultrasound in management. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001, 80, 287-299. [Review; Level IV; C]. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Ting, Y.H.; Leung, T.Y. Determining chorionicity and amnionicity in twin pregnancies: Pitfalls. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2022, 84, 2–16, [Review; Level IV; C]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary-Goldman, J.; Berkowitz, R.L. First Trimester Screening for Down Syndrome in Multiple Pregnancy. Seminars in Perinatology 2005, 29(6), 395-400. [Review; Level IV; C]. [CrossRef]

- Rosner, J.Y.; Fox, N.S.; Saltzman, D.; Klauser, C.K.; Rebarber, A.; Gupta, S. Abnormal Biochemical Analytes Used for Aneuploidy Screening and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in Twin Gestations. Amer J of Perinatol. 2015, 32(14), 1331–35. [Retrospective cohort, descriptive analysis; n=340; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Hedriana, H.; Martin, K.; Saltzman, D.; Billings, P.; Demko, Z.; Benn, P. Cell-Free DNA Fetal Fraction in Twin Gestations in Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism-Based Noninvasive Prenatal Screening. Prenatal Diag. 2020, 40(2), 179–84. [Retrospective cohort, descriptive analysis; n=121,446 singleton, n=1454 monozygotic twins, n=3161 dizygotic twins; Level III;B]. [CrossRef]

- Casasbuenas, A.; Wong, A.E.; Sepulveda, W. Nuchal Translucency Thickness in Monochorionic Multiple Pregnancies: Value in Predicting Pregnancy Outcome.” J of Ultrasound in Med 2008, 27(3), 363–69. [Retrospective cohort, descriptive analysis; n=30 monochorionic multiple gestation; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Dugoff, L. et al. Cell-Free DNA Screening for Trisomy 21 in Twin Pregnancy: A Large Multicenter Cohort Study. American J of Obstet and Gynecol. 229, 4, 435.e1-435.e7. [Retrospective cohort, descriptive analysis; n=1447 twin pregnancies analyzed by cell free fetal DNA; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Fosler, L. et al. Aneuploidy Screening by Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing in Twin Pregnancy. Ultrasound in Obstet and Gynecol. 2017, 49(4), 470–77. [Retrospective cohort, descriptive analysis; n=115 stored samples with known outcome and n=487 prospectively collected samples from twin pregnancies requested to be analyzed by cell free fetal DNA; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Kim, H.M.; Cha, H.H.; Kim, J.I.; Seong, W.J. Correlation between Serum Markers in the Second Trimester and Preterm Birth before 34 Weeks in Asymptomatic Twin Pregnancies. Internat J of Gynecol and Obstet. 2022, 156(2), 355–60. [Retrospective cohort; n=12 twin pregnancies; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Delisle, M.F.; Brosseuk, L.; Wilson, R.D. Amniocentesis for Twin Pregnancies: Is Alpha-Fetoprotein Useful in Confirming That the Two Sacs Were Sampled? Fetal Diag and Ther 2007, 22(3), 221–25. [Retrospective cohort; n=260 twin pregnancies; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Lenis-Cordoba, N. et al. Amniocentesis and the Risk of Second Trimester Fetal Loss in Twin Pregnancies: Results from a Prospective Observational Study. J of Mat-Fetal and Neonal Med. 2013, 26(15): 1537–41. [Prospective case-control, n=368 control, n= 474 amniocenteses; Level IIa; B]. [CrossRef]

- Navaratnam, K. et al. Foetal Loss after Chorionic Villus Sampling and Amniocentesis in Twin Pregnancies: A Multicentre Retrospective Cohort Study. Prenat Diag. 2022, 42(12), 1554–61. [Retrospective comparative; n=3406 controls, n=258 CVS, n=406 amniocentesis; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Appelman, Z.; Furman, B. Invasive Genetic Diagnosis in Multiple Pregnancies. Obstet and Gynecol Clinics of N Amer. 2005, 32(1), 97–103. [Review; Level IV]. [CrossRef]

- Whitaker KM, Baruth M, Schlaff RA, Talbot H, Connolly CP, Jihong L, Wilcox. Provider advice on physical activity and nutrition in twin pregnancies: a cross-sectional electronic survey. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2019; 19:418. [Electronic survey; n=276 women delivering twins; Cross sectional survey study; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Georgieff, MK. Iron Deficiency in Pregnancy. 2020; 223:4:516-524. [Review; Level IV; C]. [CrossRef]

- Bricker, L. Optimal Antenatal Care for Twin and Triplet Pregnancy: The Evidence Base. Best Practice and Research: Clin Obstet and Gynaecol. 2014, 28(2), 305–17. [Review; Level IV; C]. [CrossRef]

- Ijzerman, R; Boomsma, D.; Stehouwer, C. Intrauterine Environmental and Genetic Influences on the Association between Birthweight and Cardiovascular Risk Factors: Studies in Twins as a Means of Testing the Fetal Origins Hypothesis. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 2005, 19, 10–14. [Review; Level IV; C]. [CrossRef]

- Briffa, C. ; Stirrup O, Huddy C, Richards J, Shetty S, Reed K, et al. Twin chorionicity-specific population birth-weight charts developed with adjustment for estimated fetal weight. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021, 58, 439-449. [Retrospective cohort; n=1664 twin pregnancies; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Stirrup, O.T.; Khalil, A.; D'Antonio, F.; Thilaganathan, B. Fetal growth reference ranges in twin pregnancy: analysis of the Southwest Thames Obstetric Research Collaborative (STORK) multiple pregnancy cohort. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015, 45, 301–307. [Retrospective comparative study; n=9866 exams, n=1802 dichorionic diamniotic twin, n= 323 monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Kalafat, E.; Sebghati, M.; Thilaganathan, B.; Khalil, A. Southwest Thames Obstetric Research Collaborative (STORK). Predictive accuracy of Southwest Thames Obstetric Research Collaborative (STORK) chorionicity-specific twin growth charts for stillbirth: a validation study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019; 53, 193–199. [Multi-center Cohort of n=1850 dichorionic, n=300 monochorionic twin pregnancies; Level III; B].

- Hamilton, E.F.; Platt, R.W.; Morin, L.; Usher, R.; Kramer, M. How small is too small in a twin pregnancy? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998; 179, 682–685. [Cohort n=1062 dichorionic twins, n=354 monochorionic twins, n=59,873 singleton pregnancies; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A. , Rodgers M, Baschat A, Bhide A, Gratacos E, Hecher K, et al. ISUOG Practice Guidelines: Role of ultrasound in twin pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016, 47, 247–263. [Review; Level IV; C]. [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A. , Beune I, Hecher K, Wynia K, Ganzevoort W, Reed K, Lewi L, et al. Consensus definition and essential reporting parameters of selective fetal growth restriction in twin pregnancy: a Delphi procedure. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019, 53, 47–54. [Review; Level IV; C]. [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Antepartum Fetal Surveillance. Obstet & Gynecol. 2014, 137(6), e116-e127. [Review; Level IV; C]. [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Indications for Outpatient Fetal Surveillance. Obstet & Gynecol. 2021, 137(6), e177–e197. [Review; Level IV; C]. [CrossRef]

- Stirrup, O.T.; Khalil, A. ; D'Antonio,F.; Thilaganathan, B. Fetal growth reference ranges in twin pregnancy: Analysis of the Southwest Thames Obstetric Research Collaborative (STORK) multiple pregnancy cohort. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015, 45, 301–307. [Comparative study; n=9866 exams, n=1802 dichorionic-diamniotic twins, n=323 monochorionic-diamniotic twin pregnancies; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Grewal J, Grantz K, Zhang C, Sciscione A, Wing DA, Grobman WA, et al. Cohort Profile: NICHD Fetal Growth Studies–Singletons and Twins. Int J Epidemiol. 2018; 47:1:25-251. [Prospective Cohort, n = 2334 low-risk singletons, n=468 obese, n= 171 twins; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Xia YQ, Lyu SP, Zhan J, Chen YT, et al. Development of fetal growth charts in twins stratified by chorionicity and mode of conception: a retrospective cohort study in China. Chin Med J; 2021:134:15:1819-1827. [Prospective cohort; n=929 twins, n=2019 singletons; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Chang YL, Chao AS, Chang SD, Cheng PJ, Lik WF, Hsu CC. Incidence, prognosis, and perinatal outcomes of and risk factors for severe twin-twin transfusion syndrome with right ventricular outflow obstruction in the recipient twin after fetoscopic laser photocoagulation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022; 22:326. [Retrospective cohort, n= 187 severe cases of TTTS; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Chiu LC, CHang YL, Chao AS, Chang SD, Cheng PJ, Liao YC. Effect of Gestational Age at Fetoscopic Laser Photocoagulation on Perinatal Outcomes for Patients with Twin-Twin Transfusion Syndrome. J Clin Med. 2023:12:5:1900. [Case-control; n=197 severe TTTS stratified by early vs. late; Level IIa; B]. [CrossRef]

- Roman A, Saccone G, Dude CM, et al. Midtrimester transvaginal ultrasound cervical length screening for spontaneous preterm birth in diamniotic twin pregnancies according to chorionicity. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018; 229:57-63. [Prospective descriptive cohort, n= 580 twins; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Klein K, Gregor H, Hirtenlehner-Ferber K, Stammler-Safar M, Witt A, Hanslik A, Husslein P, Krampl E. Prediction of spontaneous preterm delivery in twin pregnancies by cervical length at mid-gestation. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2008;11(5):552-557. [Prospective observational cohort; n=223 twin pregnancies; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Khalil MI, Alzahrani MH, Ullah A. The use of cervical length and change in cervical length for prediction of spontaneous preterm birth in asymptomatic twin pregnancies. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;169(2):193-196. [Prospective observational cohort; n=209 asymptomatic twin pregnancies with complete data; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Melamed N, Pittini A, Hiersch L, Yogev Y, Korzeniewski SJ, Romero R, Barrett R. Do Seial Measurements of Cervical Length Improve the Prediction of Preterm Birth in Asymptomatic Women with Twin Gestations. Am J Obstet Gynecol; 2016; 215:4:616.e1-616.e14. [Retrospective cohort; n=441 twins, n=2374 measurements; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, C.; Hecher, K. Update on twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2019, 58, 55-65. [Review; Level IV; C]. [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, C.; Hecher, K. Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome: Controversies in the diagnosis and management. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2022, 84. 143-154. [Review; Level IV; C]. [CrossRef]

- Sacco A, Van der Veeken L, Bagshaw E, Ferguson C, Mieghem TV. Maternal complications following open and fetoscopic fetal surgery: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Prenat Diagn; 2019:39:4:251-268. [Meta-analysis n=1193 open fetal surgery and n=9403 fetoscopic surgery; Level IIb; B]. [CrossRef]

- Baschat AA, Barber J, Pedersen N, Turan OM, Harman CR. Outcome after fetoscopic selective laser ablation of placental anastomoses vs equatorial laser dichorionization for the treatment of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol; 2013; 209:3:234e1-234.e8. [Comparative study; n=147 twin pregnancies underwent laser (S-LASER, n=71; ED-LASER, n=76; Level IIa; B]. [CrossRef]

- Cincinnati Fetal Center. Volumes & Outcomes Summary 2020. https://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/-/media/cincinnati%20childrens/home/service/f/fetal-care/conditions/2020%20volumesoutcomes_final.pdf [Observational cohort; n=8080; Level III; B].

- Moldenhauer, J.S.; Johnson, M.P. Diagnosis and Management of Complicated Monochorionic Twins. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015, 58(3), 632-642. [Review; Level IV; C]. [CrossRef]

- Quinn KH, Cao CT, Lacoursiere DY, Schrimmer D. Monoamniotic Twin pregnancy: Continuous inpatient electronic fetal monitoring (CIEFM) - an impossible goal? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011, 204, 161.e1–161.e6, [Retrospective case-control; n=10,402 hours of fetal monitoring; Level IIa; B]. [CrossRef]

- Wapner RJ, Sorokin Y, Thom EA, Johnson F, Dudley DJ, Spong CY, et al.. Single versus weekly courses of antenatal corticosteroids: Evaluation of safety and efficacy. NICHD MFMU Network. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006, 195, 633–642, [RCT, n=495, study terminated prior to target of 2400 patients by independent data and safety monitoring committee; Level Ib; A]. [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Antenatal Corticosteroid Therapy for Fetal Maturation. Obstet & Gynecol. 2017, 130, e102–e109, [Review; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Post A, Heyborne K. Managing Monoamniotic Twin Pregnancies. Clin Obstet Gynecol; 2015; 58:3:643-53. [Review; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Van Mieghem T, Abbasi N, Shinar S, Keunen J, Seaward G, Windrim R, Ryan G. Monochorionic monoamniotic twin pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM; 2022: 4:2S [Review; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Vitucci A, Fichera A, Fratelli N, Sartori E, Prefumo F. Twin Reversed Arterial Perfusion Sequence: Current Treatment Options. Int J Womens Health. 2020;12:435-443. PMCID: PMC7266514 [Level IV]. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelin E, Hirose S, Rand L, et al. Perinatal outcome of conservative management versus fetal intervention for twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence with a small acardiac twin. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2010;27(3):138–141. [Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Cabassa P, Fichera A, Prefumo F, et al. The use of radiofrequency in the treatment of twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence: a case series and review of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;166(2):127–132. [Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Prefumo F, Fichera A, Zanardini C, Frusca T. Fetoscopic cord transection for treatment of monoamniotic twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;43(2):234–235 [Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Oostra R, Shepens-Franke AN. Conjoined twins and conjoined triplets: At the heart of the matter. Birth Defects Res; 2022: 114:12:596-610.[Review; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Spietz, L. Conjoined twins. Prenatal Diagn; 2005: 25:9:814-819. [Review; Level III]. [CrossRef]

- Dias, T.; Akolekar, R. Timing of birth in multiple pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014; 28, 319–326, [Review; Level III; B]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhatre M, Craigo S. Triplet pregnancy: What do we tell the prospective parents. Prenat Diagn; 2021: 41:12:1593-1601.[Review; Level III; B]. [CrossRef]

- Dera-Szymanowska A, Filipowicz D, Misan N, Szymanowski K, Samson Chillon T, Asaad S, Sun Q, et al. Are Twin Pregnancies at Higher Risk for Iron and Calcium Deficiency than Singleton Pregnancies? Nutrients 2023; 15 (18), 4047. [Retrospective case-control, n=114 pregnancies, 61 singleton; Level III; B]. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blickstein I, Goldschmit R, Lurie S. Hemoglobin levels during twin vs. singleton pregnancies. Parity makes the difference. J Reprod Med 1995; 40:47-50 [Observational cohort; Level III; B].

- Shinar S, Skornick-Rapaport A, Maslovitz S. Iron Supplementation in Twin Pregnancy - The Benefit of Doubling the Iron Dose in Iron Deficient Pregnant Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2017 Oct;20(5):419-424. Epub 2017 Aug 22. [Level Ib; A]. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chantanahom N, Phupong V. Clinical risk factors for preeclampsia in twin pregnancies. PLoS One. 2021 Apr 15;16(4):e0249555. PMCID: PMC8049247. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N, Han Q, Zheng S, Chen R, Zhang H, Yan J. A New Model for the Predicting the Risk of Preeclampsia in Twin Pregnancy. Front Physiol 2022; 13 :850149. [Level III ; B]. [CrossRef]

- Simões, T.; Queirós, A.; Correia, L.; Rocha, T.; et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus complicating twin pregnancies. J Perinat Med. 2011, 39, 437–440, [Level III;B]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitris, M.C.; Kaufman, J.; Bodnar, L.M.; Platt, R.W.; et al. Gestational Diabetes in twin versus singleton pregnancies with normal weight or overweight pre-pregnancy body mass index: the mediating role of mid-pregnancy weight gain. Epidemiology 2022, 33, 278–286, [Level III;B]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauh-Hain, J.A.; Rana, S.; Tamez, H.; Wang, A.; et al. Risk for developing gestational diabetes in women with twin pregnancies. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009, 22, 293–299, [Level III;B]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwal, E.; Berger, H.; Hiersch, L.; et al. Gestational diabetes and fetal growth in twin compared with singleton pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021, 225, 420.e1–420.e13, [Level III;B]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau HCG, Subramaniam A, Andrews WW. Infection and preterm birth. Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2016; 21: 100–105.[Level IV]. [CrossRef]

- Denney JM, Culhane JF. Bacterial vaginosis: a problematic infection from both a perinatal and neonatal perspective. Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2009; 14: 200–203. [Level IV]. [CrossRef]

- US Preventive Services Task Force, Owens DK, Davidson KW,Krist AH, Barry MJ, Cabana M, et al. Screening for Bacterial Vaginosis in Pregnant Persons to Prevent Preterm Delivery: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2020; 323: 1286–1292. [Level III]. [CrossRef]

- Smaill FM, Vazquez JC. Antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019; 2019: CD000490 [Level III]. [CrossRef]

- Twin and Triplet Pregnancy. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2019. [Review; Level III; B]. [PubMed]

- Care A, Nevitt SJ, Medley N, Donegan S, Good L, Hampson L, et al. Interventions to prevent spontaneous preterm birth in women with singleton pregnancy who are at high risk: system-atic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical ResearchEd.). 2022; 376: e064547. [CrossRef]

- Conde-Agudelo A, Romero R, Da Fonseca E, O’Brien JM, Cetingoz E, Creasy GW, et al. Vaginal progesterone is as effective as cervical cerclage to prevent preterm birth in women with a singleton gestation, previous spontaneous preterm birth, and a short cervix: updated indirect comparison meta-analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2018; 219: 10–25. [CrossRef]

- EPPPIC Group. Evaluating Progestogens for Preventing Preterm birth International Collaborative (EPPPIC): meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomized controlled trials. Lancet (London, England). 2021; 397:1183–1194. [CrossRef]

- Romero R, Conde-Agudelo A, Da Fonseca E, O’Brien JM, Cetingoz E, Creasy GW, et al. Vaginal progesterone for preventing preterm birth and adverse perinatal outcomes in singleton gestations with a short cervix: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2018; 218: 161–180. [CrossRef]

- Norman JE, Marlow N, Messow CM, Shennan A, Bennett PR, Thornton S, et al. Vaginal progesterone prophylaxis for preterm birth (the OPPTIMUM study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet (London, England). 2016;387: 2106–211. [CrossRef]

- El-refaie W, Abdelhafez MS, Badawy A. Vaginal progesterone for prevention of preterm labor in asymptomatic twin pregnancies with sonographic short cervix: a randomized clinical trial of efficacy and safety. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293(1):61-67. [CrossRef]

- Schuit E, Stock S, Rode L, et al.; Global Obstetrics Network (GONet) collaboration. Effectiveness of pro-gestogens to improve perinatal outcome in twin pregnancies: an individual participant data meta-analysis. BJOG. 2015;122(1):27-37. [CrossRef]

- Romero R, Nicolaides K, Conde-Agudelo A, et al. Vaginal progesterone in women with an asymptomatic sonographic short cervix in the midtrimester decreases preterm delivery and neonatal morbidity: a systematic review and metaanalysis of individual patient data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(2):124:e1–124.e19. [CrossRef]

- Berghella V, Roman A. Cerclage in twins: we can do better! Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014; 211:1:5-6. [Level IV]. [CrossRef]

- Roman A, Calluzzo I, Fleischer A, Rochelson B.Physical examination indicated cerclage in twin pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014; 210: S391-S392. [Level III]. [CrossRef]

- Fuchs F, Lefevre C, Senat MV, Fernandez H. Accuracy of fetal fibronectin for the prediction of preterm birth in symptomatic twin pregnancies: a pilot study. Sci Rep 2018; 8:2160. [Level III]. [CrossRef]

- Conde-Agudelo A, Romero R. Cervicovaginal fetal fbronectin for the prediction of spontaneous preterm birth in multiple pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 23, 1365–1376. (2010). [Level III; n=1221 multiple gestations]. [CrossRef]

- Ganchimeg, T.; Morisaki, N.; Vogel, J.P.; et al. Mode and timing of twin delivery and perinatal outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: a secondary analysis of the WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health. BJOG 2014, 121 Suppl:89-100. [Comparative study, n=124,446 mother-infant pairs; Level IIa]. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.M. Delivery of Twins. Semin Perinatol. [Review with secondary analysis; Level III; B]. 2012, 36, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, B.K.; Miller, R.; D’Alton, M.; Grobman, W. Effectiveness of Timing Strategies for Delivery of Monochorionic Diamniotic Twins. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012, 207(1), 53.e1-53.e7. [Comparative study/decision tree analysis; n=9 strategies; Level IIb; B]. [CrossRef]

- Dodd, J.M.; Deussen, A.; Grivell, R.; Crowther, C. Elective Birth at 37 Weeks’ Gestation for Women with an Uncomplicated Twin Pregnancy at term; the Twins Timing of Birth Randomised Trial. BJOG 2012;119(8):964-73. [RCT; n=235 uncomplicated twin pregnancies at 36 6/7; Level Ib; A]. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, E, Oldenburg A, Rode L, Tabor A, Rasmussen S, Skibsted L.. Twin Births: Cesarean Section or Vaginal Delivery? Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2012, 91(4), 463–69.[Comparative Study; n=689 twin vaginal deliveries vs. n=371 planned twin cesarean deliveries, OR1.47, p=0.037 poor outcome with vaginal delivery; Level IIb; B]. [CrossRef]

- Aviram, A, Lipworth H, Asztalos E, Mei-Dan E, Melamed N, Cao X, Zaltz A, Hvidman L.. Delivery of Monochorionic Twins: Lessons Learned from the Twin Birth Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020, 223(6): 916.e1-916.e9. [RCT, n= 346 planned cesarean and n=324 planned vaginal delivery; Level Ib; A].

- Roman AS, Fishman S, Fox N, Klauser C, Saltzman D, Rebarber A. Maternal and neonatal outcomes after delayed-interval delivery of multifetal pregnancies. Am J Perinatol. 2011 Feb;28(2):91-6. Epub 2010 Jul 6. [Level IIb]. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkouh LJ, Sabin ED, Heyborne KD, Lindsay LG, Porreco RP. Delayed-interval delivery: extended series from a single maternal-fetal medicine practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Dec;183(6):1499-503. [Level IIb]. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamersley SL, Coleman SK, Bergauer NK, Bartholomew LM, Pinckert TL. Delayed-interval delivery in twin pregnancies. J Reprod Med. 2002 Feb;47(2):125-30. [Level IIb]. [PubMed]

- Lavery JP, Austin RJ, Schaefer DS, Aladjem S. Asynchronous multiple birth. A report of five cases. J Reprod Med. 1994 Jan;39(1):55-60. [Level IIb]. [PubMed]

- Livingston JC, Livingston LW, Ramsey R, Sibai BM. Second-trimester asynchronous multifetal delivery results in poor perinatal outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Jan;103(1):77-81. [Level IIb]. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Maternal | Fetal |

|---|---|

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy Iron deficiency anemia Acute fatty liver of pregnancy Thromboembolic events Placental abruption Preterm labor Preterm premature rupture of membranes Intra-amniotic infections Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy Postpartum hemorrhage Cesarean delivery Gestational diabetes Postpartum depression Mortality |

General Preterm birth Fetal growth restriction Growth discordance Birth anomalies Miscarriage Fetal demise Monochorionic Specific Twin-twin transfusion syndrome Twin anemia polycythemia syndrome Monoamnionic Specific Cord Entanglement |

| Ia | Evidence obtained from meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials |

| Ib | Evidence obtained from at least one randomized controlled trial |

| IIa | Evidence obtained from at least one well-designed controlled study without randomization |

| IIb | Evidence obtained from at least one other type of well-designed quasi-experimental study |

| III | Evidence obtained from well-designed non-experimental descriptive studies, such as comparative studies, correlation studies and case studies |

| IV | Evidence obtained from expert committee reports or opinions and/or clinical experience of respected authorities |

| A | At least one randomized controlled trial as part of a body of literature of overall good quality and consistency addressing the specific recommendation (Evidence levels Ia or Ib) |

| B | Well-controlled clinical studies available but no randomized clinical trials on the topic of the recommendations (Evidence Levels IIa, IIb, or III) |

| C | Evidence obtained from expert committee reports or opinions and/or clinical experiences of respected authorities, indicates an absence of directly applicable clinical studies of good quality (Evidence Level IV) |

| D | Recommended best practice based on the clinical experience of the authors |

| Screening Modality | Considerations | |

|---|---|---|

| First Trimester Screen | Monochorionic | Dichorionic |

| NT measurements averaged and calculated as single risk estimate. Increased NT of one twin may be early sign of TTTS. |

Each fetus treated as separate with NT as separate risks. Each twin has its own independent risk and overall pregnancy risk is based on combined risk of both twins. An unaffected twin can mask affected twin. |

|

| Maternal Serum Screen | ↓ PAPP-A, ↑ HCG, ↑ inhibin associated with preterm birth | |

| Noninvasive Prenatal Testing | tFF can be up to 35% higher, but fetal fraction per twin is lower May be particularly helpful for screening T21 |

|

| Quintero Stage | Findings |

|---|---|

| I | Oligohydramnios¹ in the donor twin and polyhydramnios² in the recipient twin |

| II | No visualization of the fetal bladder in the donor twin. |

| III | Abnormal umbilical artery Dopplers |

| IV | Hydrops fetalis³ in one or both fetuses |

| V | Demise in one or both of the fetuses |

| Leiden Stage | Findings |

|---|---|

| I | Donor MCA > 1.5 MoM, Recipient MCA-PSV < 1.0 MoM |

| II | Donor MCA > 1.7 MoM, Recipient MCA < 0.8 MoM |

| III | Stage 1 or Stage 2 with cardiac compromise* in the donor twin |

| IV | Donor Hydrops |

| V | Demise in one or both of the fetuses |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).