Submitted:

22 April 2024

Posted:

23 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

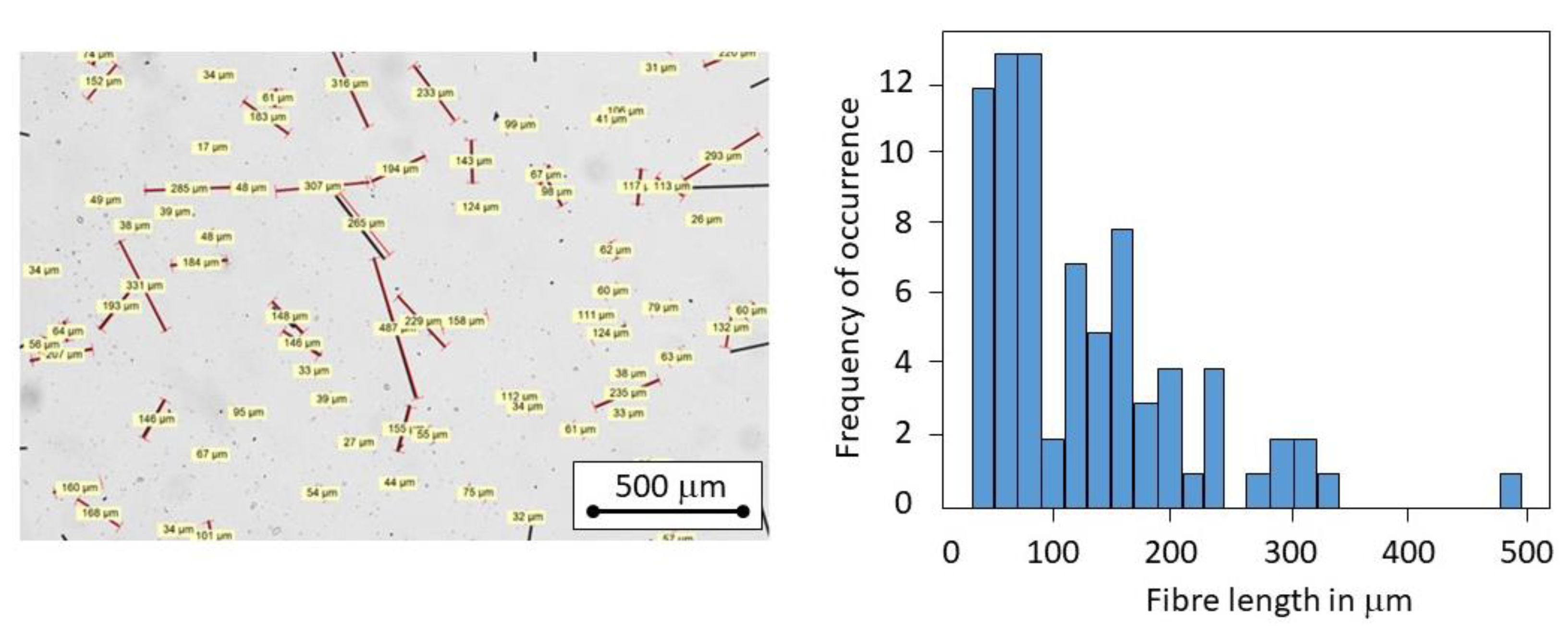

2.1. Materials

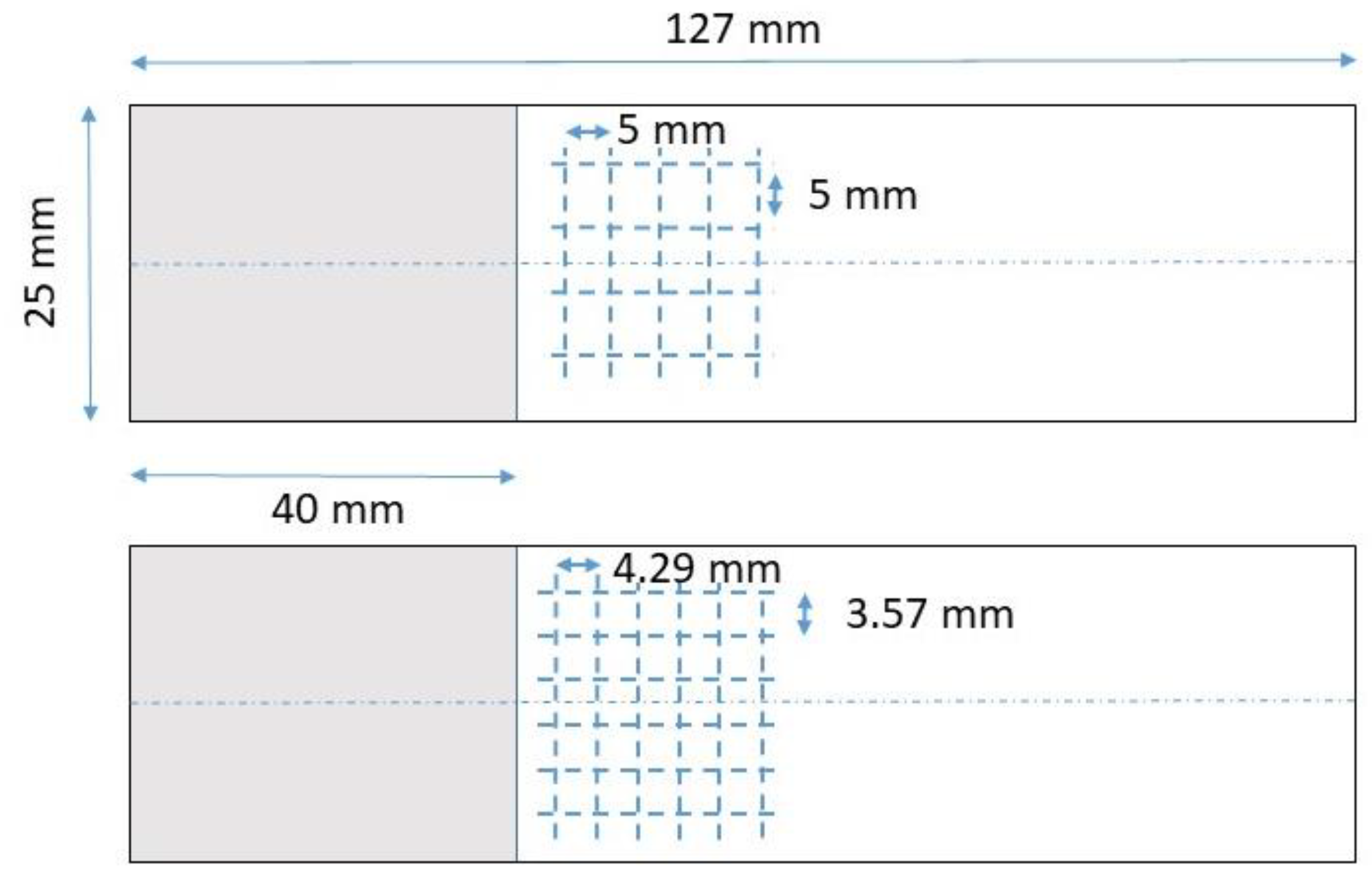

2.2. Laser Drilling

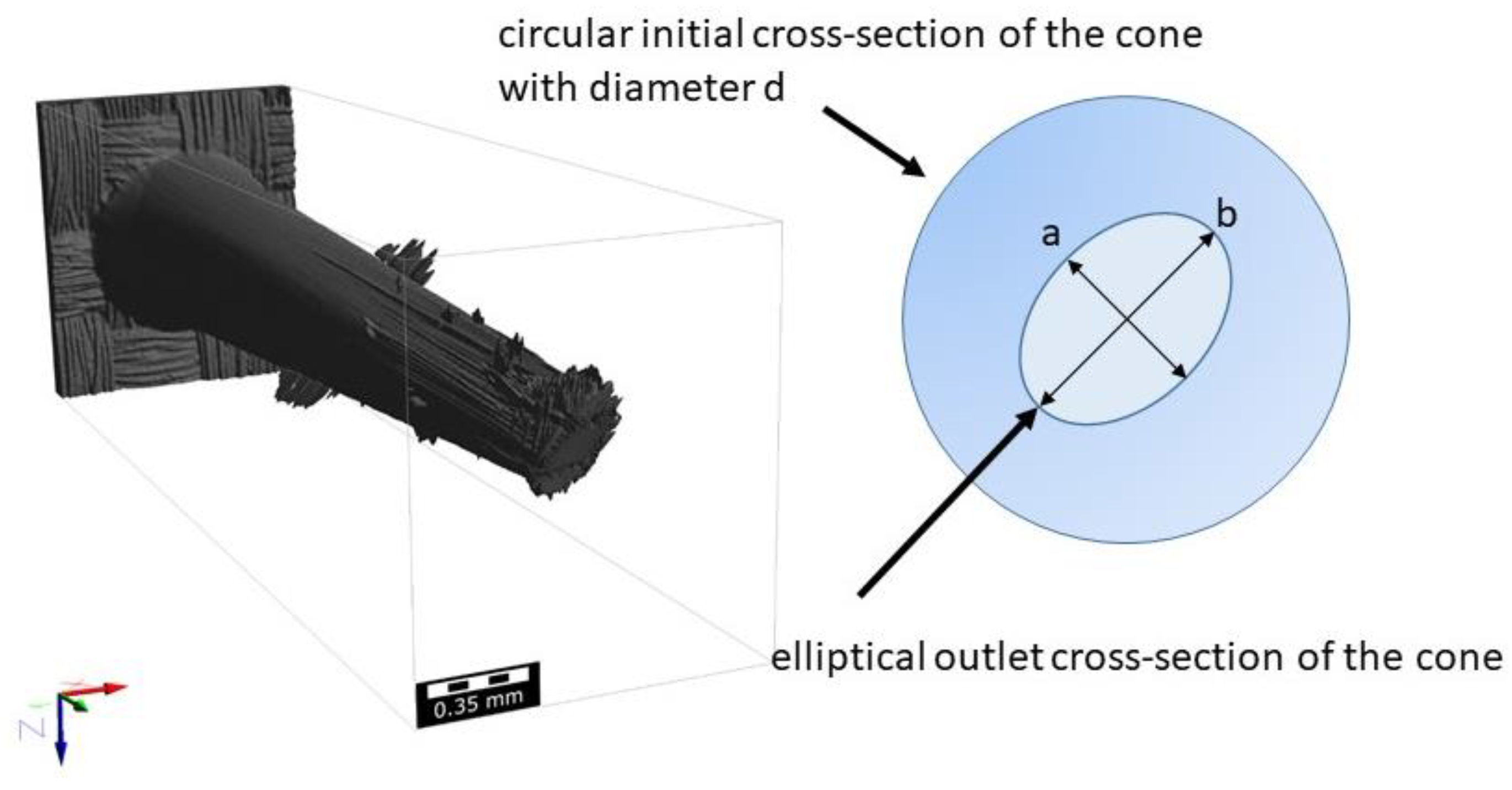

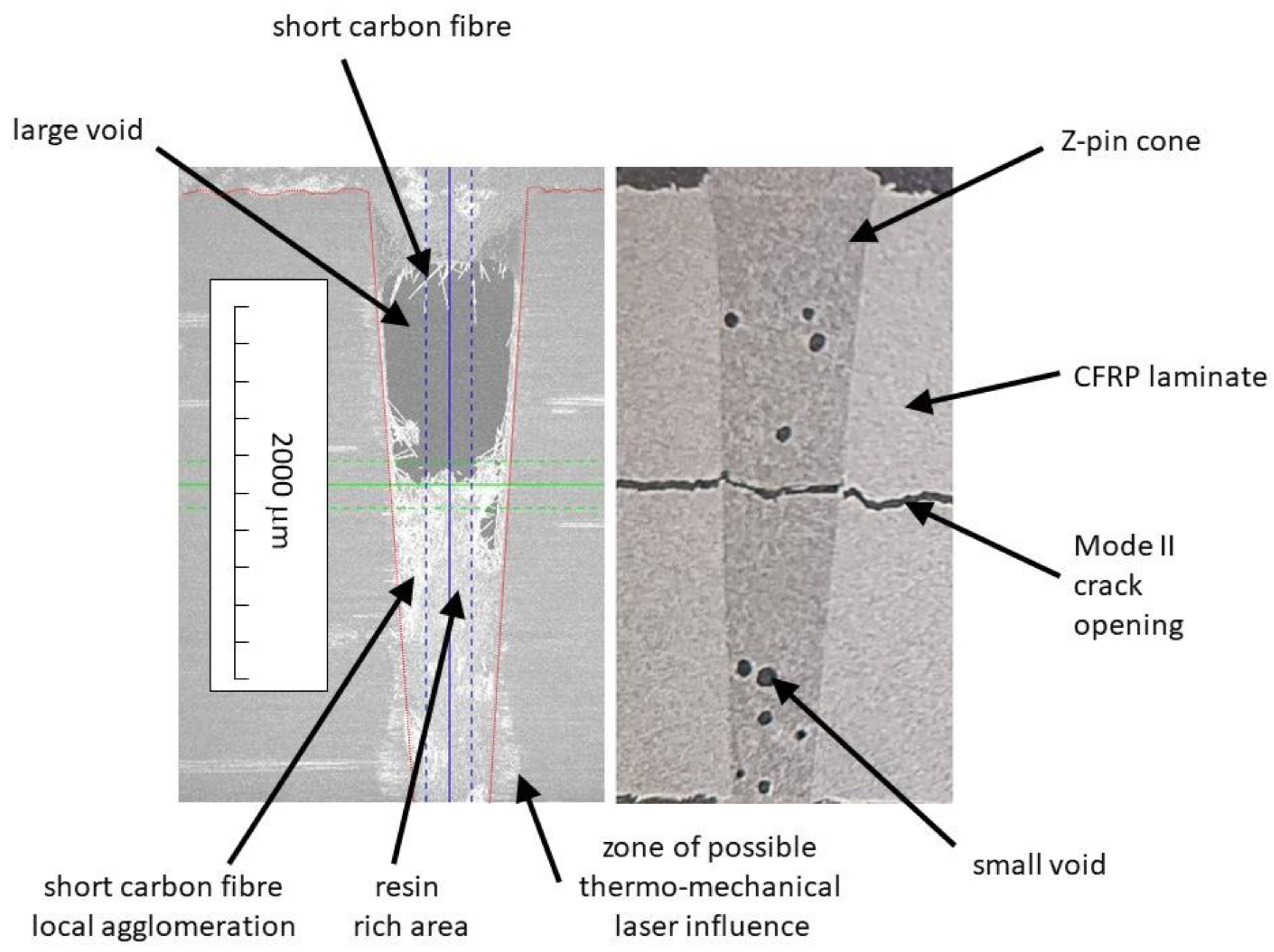

2.3. Z-Pin Manufacturing

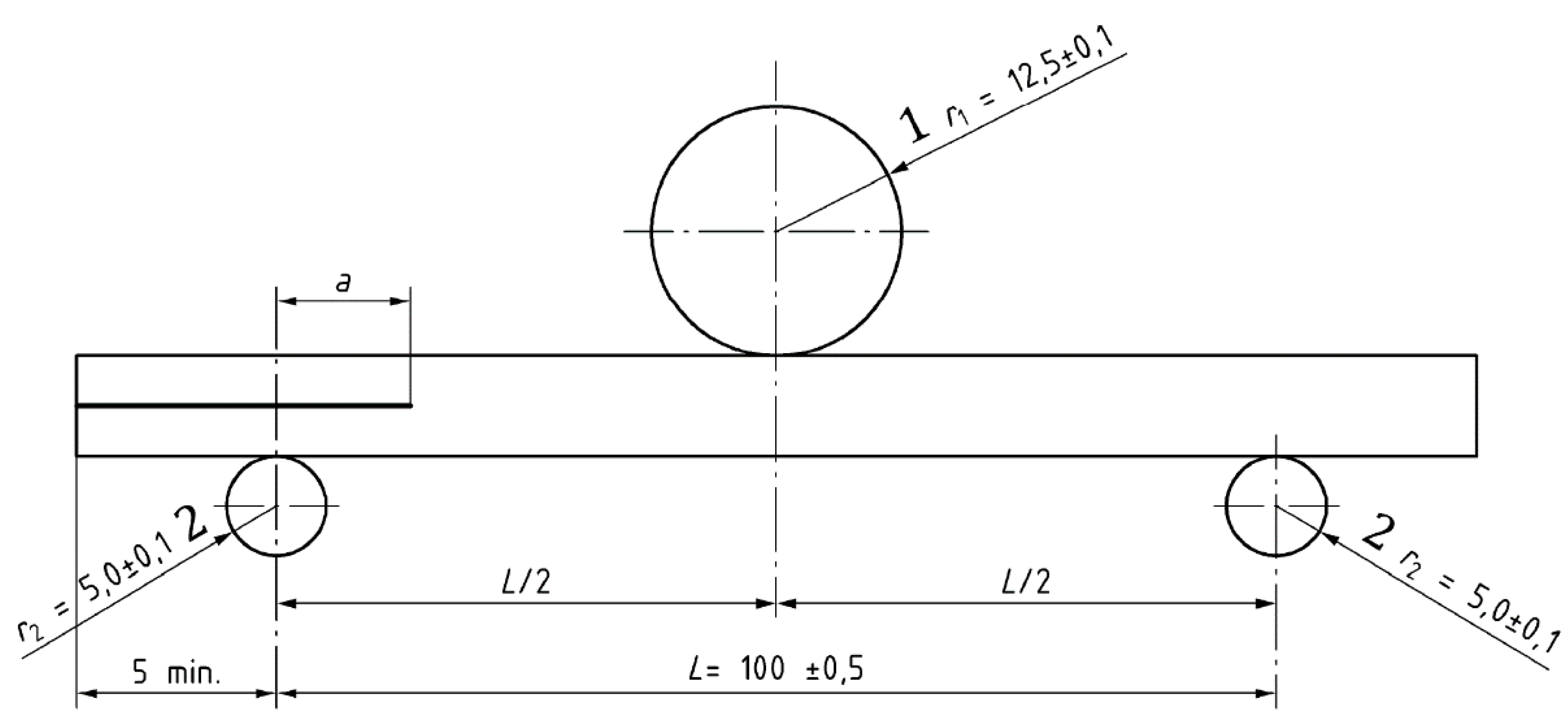

2.4. Mode II Testing

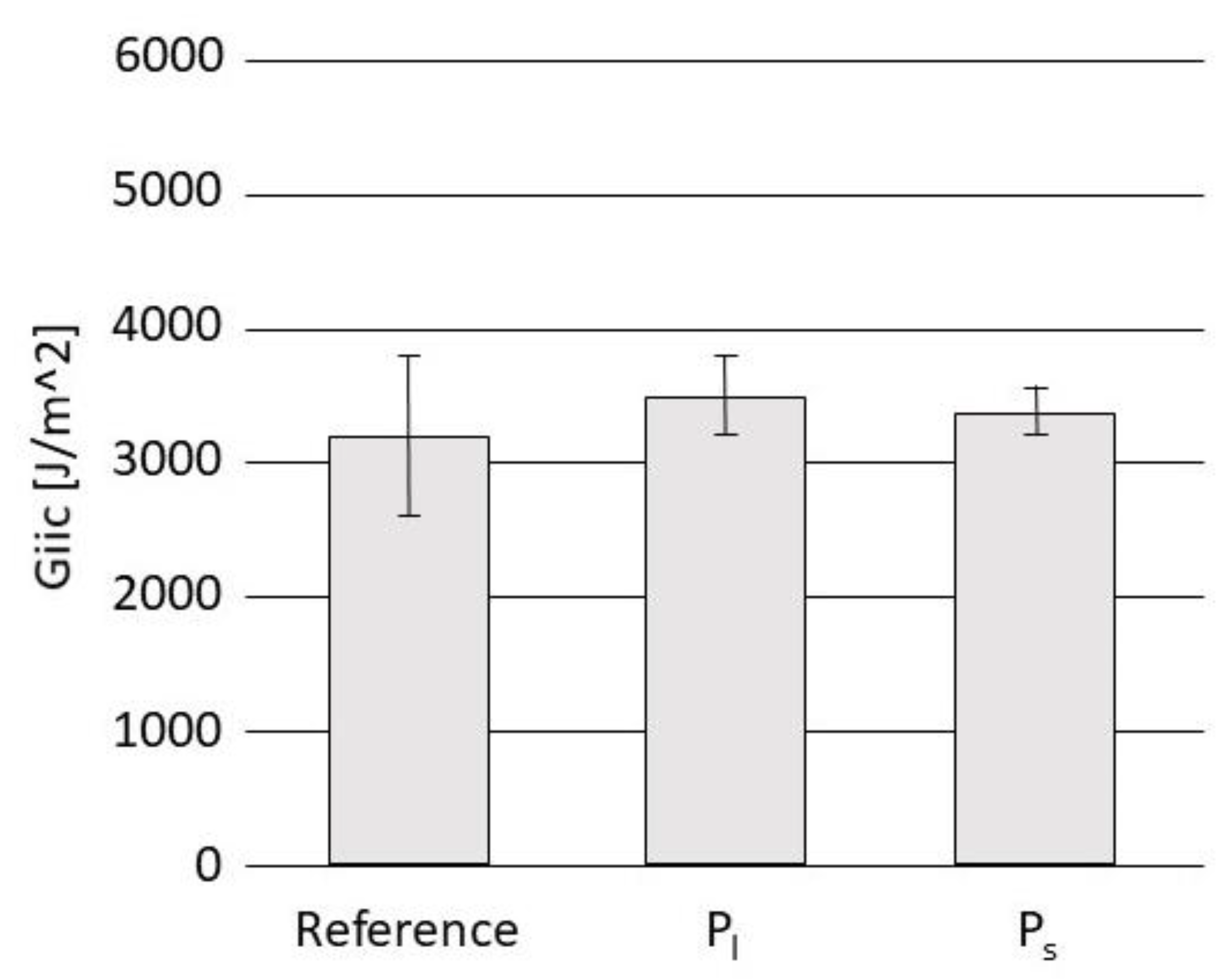

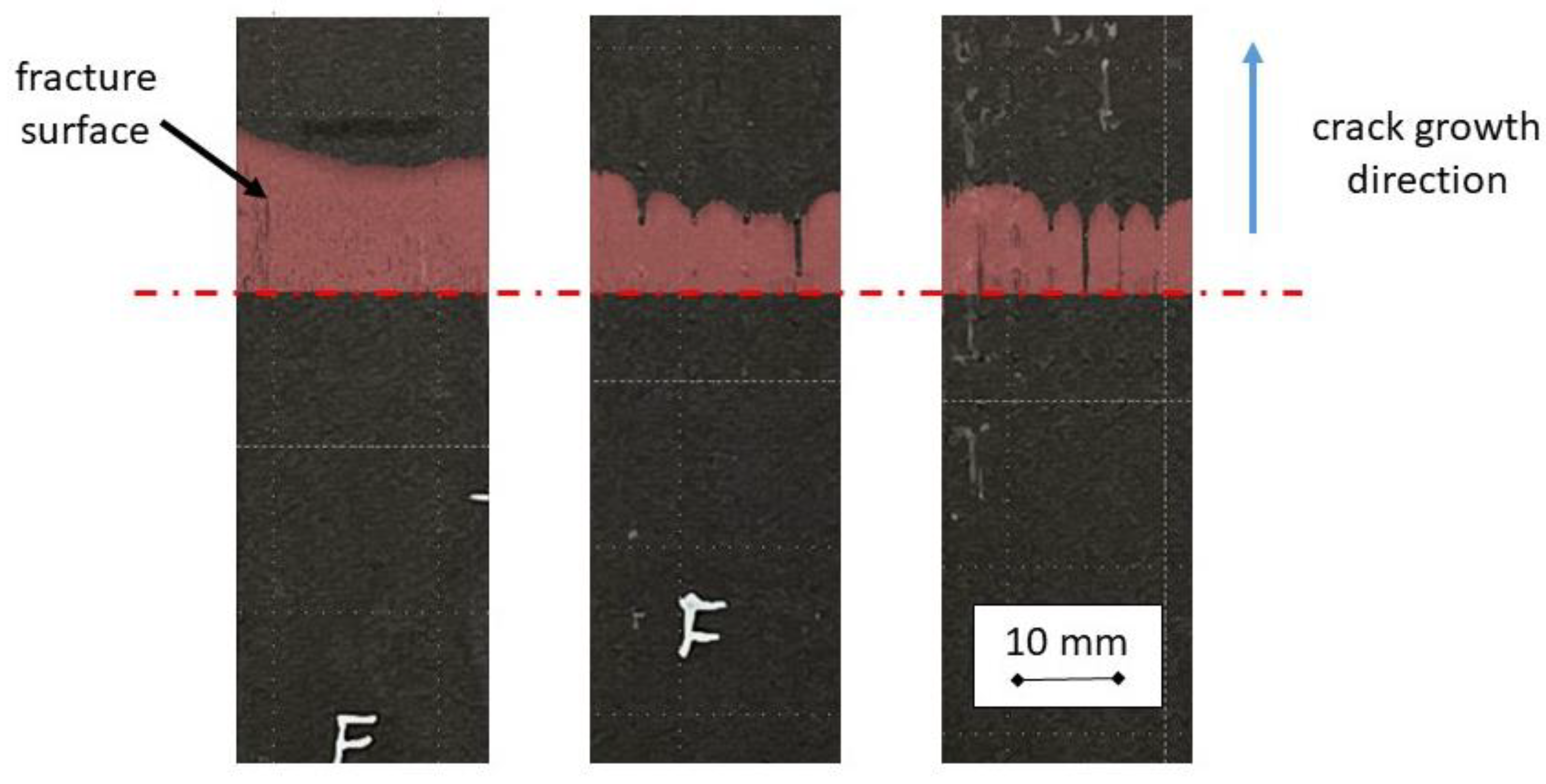

3. Results

4. Summary and Conclusion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Data Availability Statement

References

- EU, “European Green Deal,” [Online]. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_1669.

- U. P. Breuer, Commercial Aircraft Composite Technology, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2016.

- X.-S. Yi, “Development of multifunctional composites for aerospace application,” in Multifunctionality of Polymer Composites, Oxford, Elsevier, 2015, pp. 367-415.

- G. A. O. Davies and R. Olsson, “Impact on composite structures,” The Aeronautical Journal, pp. 541-563, 2004, 108 (1089).

- C. D. Stavropoulos and G. C. Papanicolaou, “Effect of thickness on the compressive performance of ballistically impacted carbon fibre reinforced plastic (CFRP) laminates,” Journal of Materials Science, pp. 931-936, 1997, 32 (4). [CrossRef]

- Gilliot, Matrix influence on the impact tolerance of carbon composites made of non-crimp fabric, Dissertation, Magdeburg: DLR Forschungsberichte, 2010.

- A. P. Mouritz, “Review of z-pinned composite laminates,” Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing, pp. 2383- 2397, 2007, 38 (12). [CrossRef]

- G. Freitas, C. G. Freitas, C. Magee, P. Dardzinski and T. Fusco, “Fiber insertion process for improved damage tolerance in aircraft laminates,” Journal of Advanced Materials, pp. 36-43, 1994, 25.

- M. Knaupp and G. Scharr, “Manufacturing process and performance of dry carbon fabrics reinforced with rectangular and circular z-pins,” Journal of Composite Materials, pp. 2163- 2172, 2014, 48 (17). [CrossRef]

- A.Mouritz, K. H. A.Mouritz, K. H. Leong and I. Herszberg, “A review of the effect of stiching on the in-plane mechanical properties of fibre-reinforced polymer composites,” Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing, pp. 979-991, 1997, 28 (12). [CrossRef]

- P. Chang, A. P. Mouritz and B. N. Cox, “Properties and failure mechanisms on z-pinned laminates in monotonic and cyclic tension,” Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing, pp. 1501- 1513, 2006, 37 (10). [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Mouritz, A.P.; Bannister, M.K. 3D Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites; Elsevier BV: Amsterdam, NX, Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- U. D. o. Defense, Composite Materials Handbook MIL-HDBK-17-1E, 2005.

- Z. Che, M. Z. Che, M. Li, S. Wang, Y. Wang, Y. Gu and W. Zhang, “Mode II interlaminar fracture toughness enhancement for fine z-pin reinforced carbon fiber composite with low fraction of pins,” Polymer Composites vol 43, no. 5, pp. 2992-3002, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Partridge and D. D. R. Cartié, “Delamination resistant laminates by z-fiber pinning: Part I manufacture and fracture performance,” Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing, pp. 55-64, 2005, 36(1). [CrossRef]

- P. Chang, The mechanical properties and failure mechanisms of z-pinned composites, Dissertation, Melbourn: School of Aerospace, Mechanical Manufacturing Engineering, RMIT University, 2005.

- Lander, Designing with z-pins:locally reinforced composite structures, Dissertation, Cranfield: Composite Centre Cranfield University, 2008.

- D. Tatsuno, R. D. Tatsuno, R. Tanaka and T. Yoneyama, “Through-Thickness Fiber Formation Integrated into Carbon-Fiber-Reinforced Thermoplastic Laminate Welding Method,” Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance Vol 31 (12), pp. 9615-9629, 22 May. [CrossRef]

- S. Carbon, “Die Verstärker: Unsere Carbonkurzfasern,” Available online:. Available online: https://www.sglcarbon.com/loesungen/material/sigrafil-carbon-kurzfasern (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- HEXION, “Technical Data SheetEPIKOTE™ Resin MGS RIMR 935 and EPIKURE™ Curing Agent MGS RIMH 936- 937,” Available online:. Available online: https://airheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/935TDS.pdf. (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- A. Carlsson, D. F. A. Carlsson, D. F. Adams and R. B. Pipes, Experimental characterization of advanced composite materials (Fourth Edition), London New York: CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group, 2024.

- F. León, Messtechnik, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2019.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).