Submitted:

19 April 2024

Posted:

22 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Design

2.2. Information Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3. Resveratrol: Chemical Structure and Main Sources

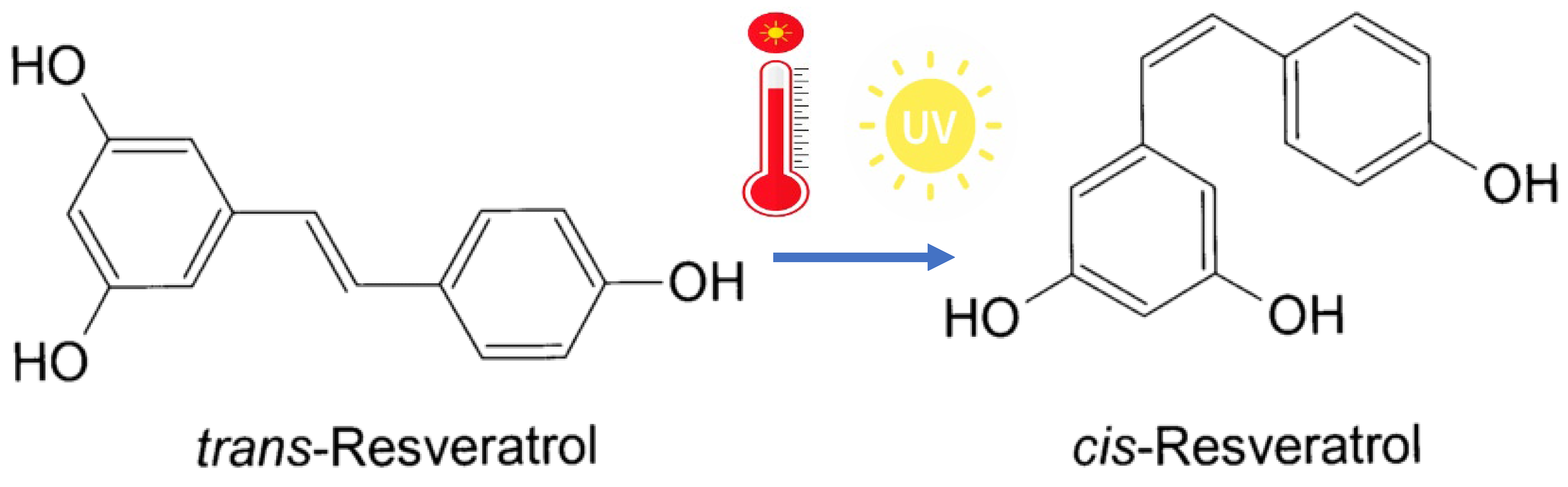

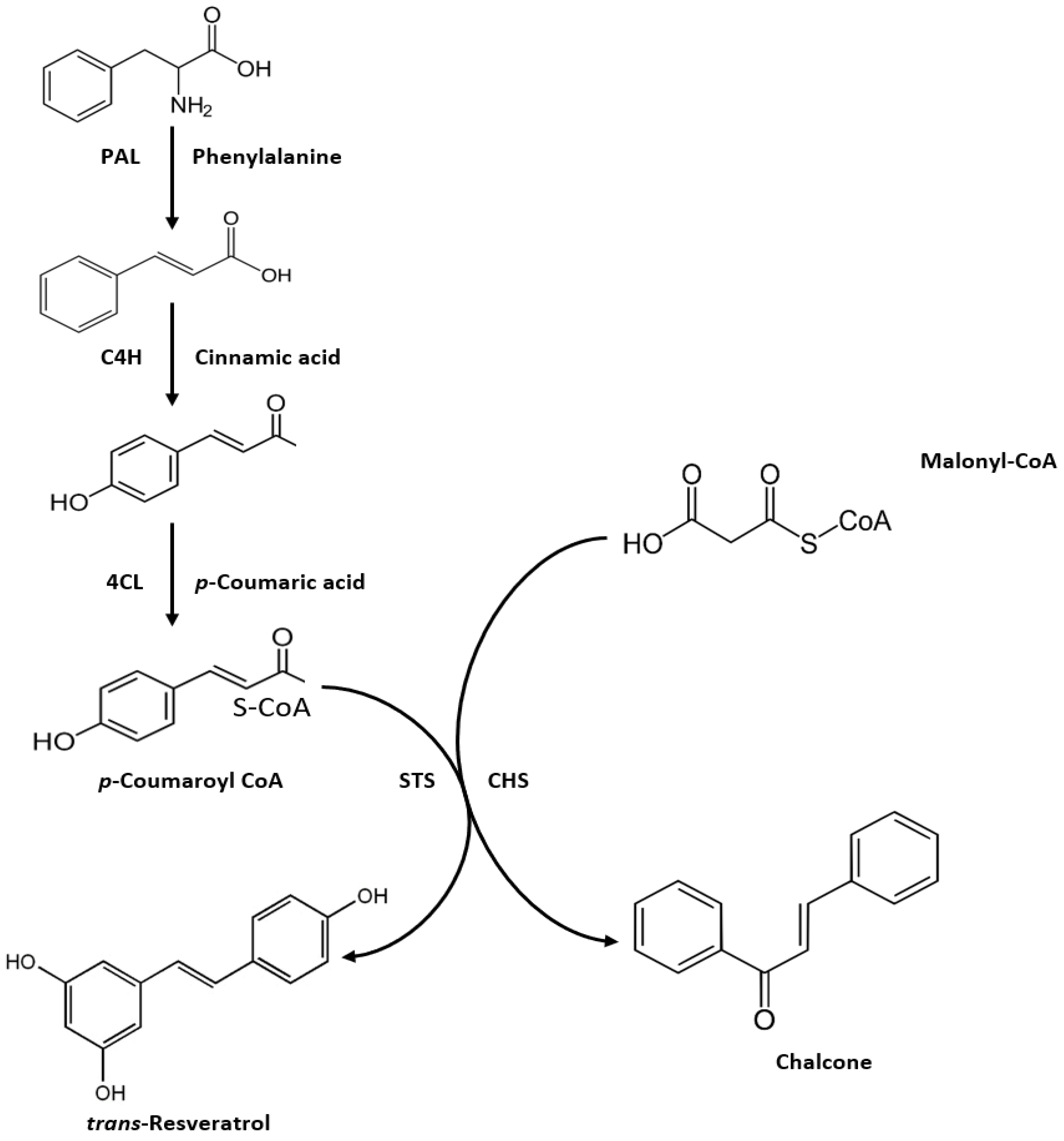

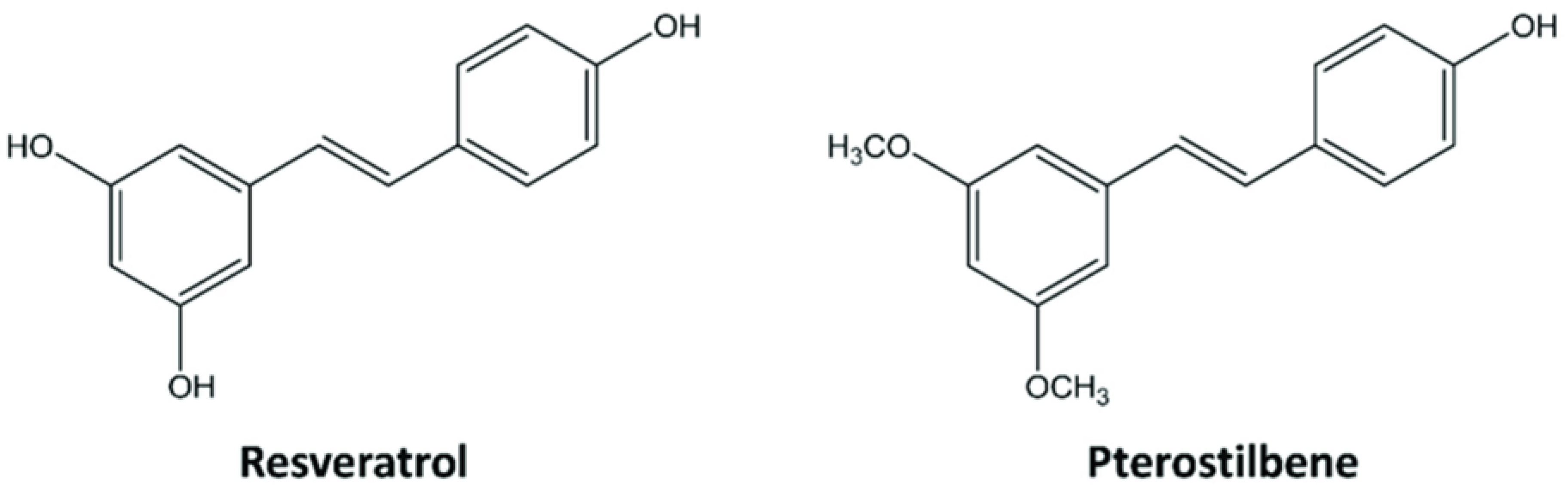

3.1. Chemical Characteristics and Biosynthesis

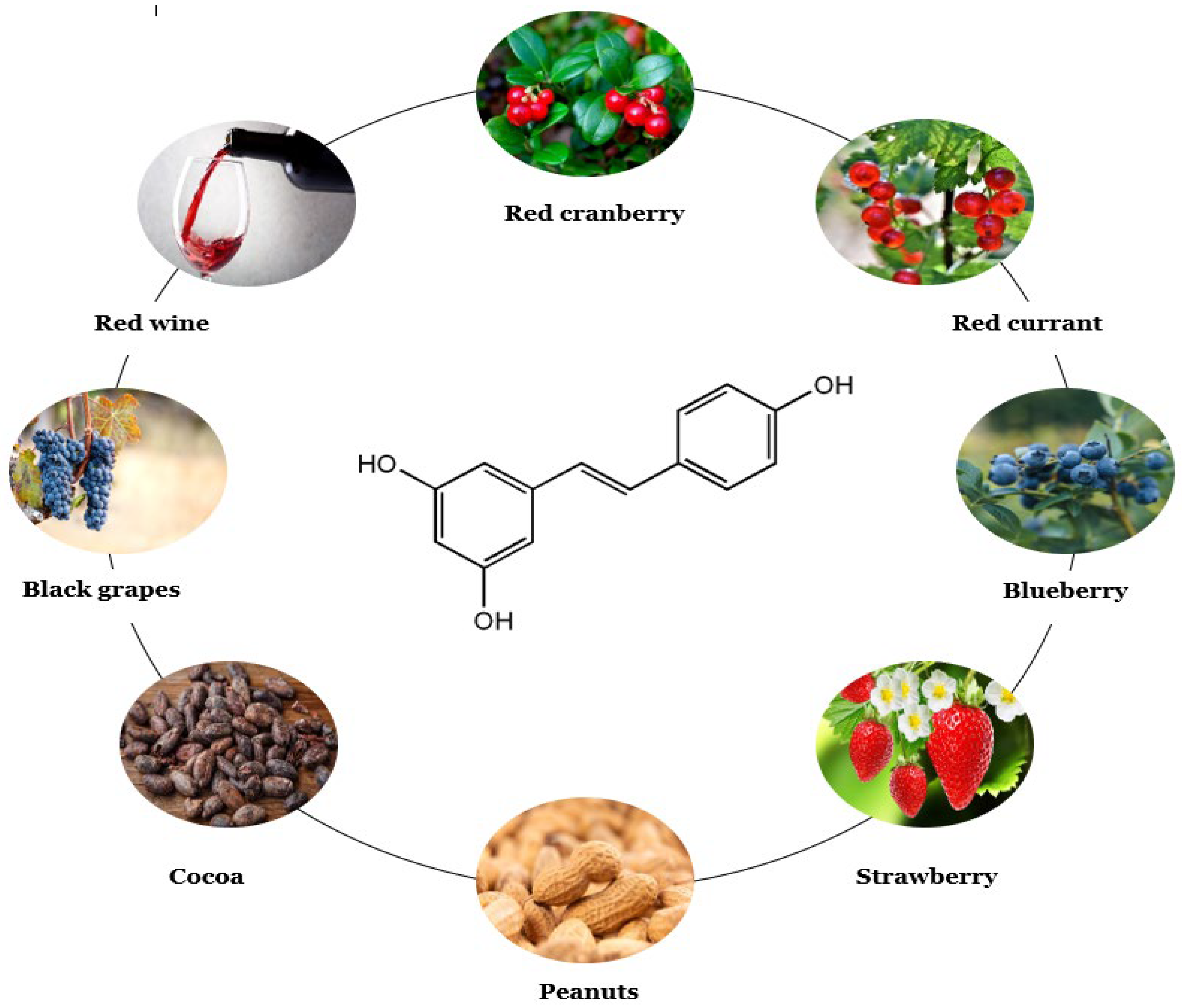

3.2. Main Plant Sources

3.3. Bioavailability

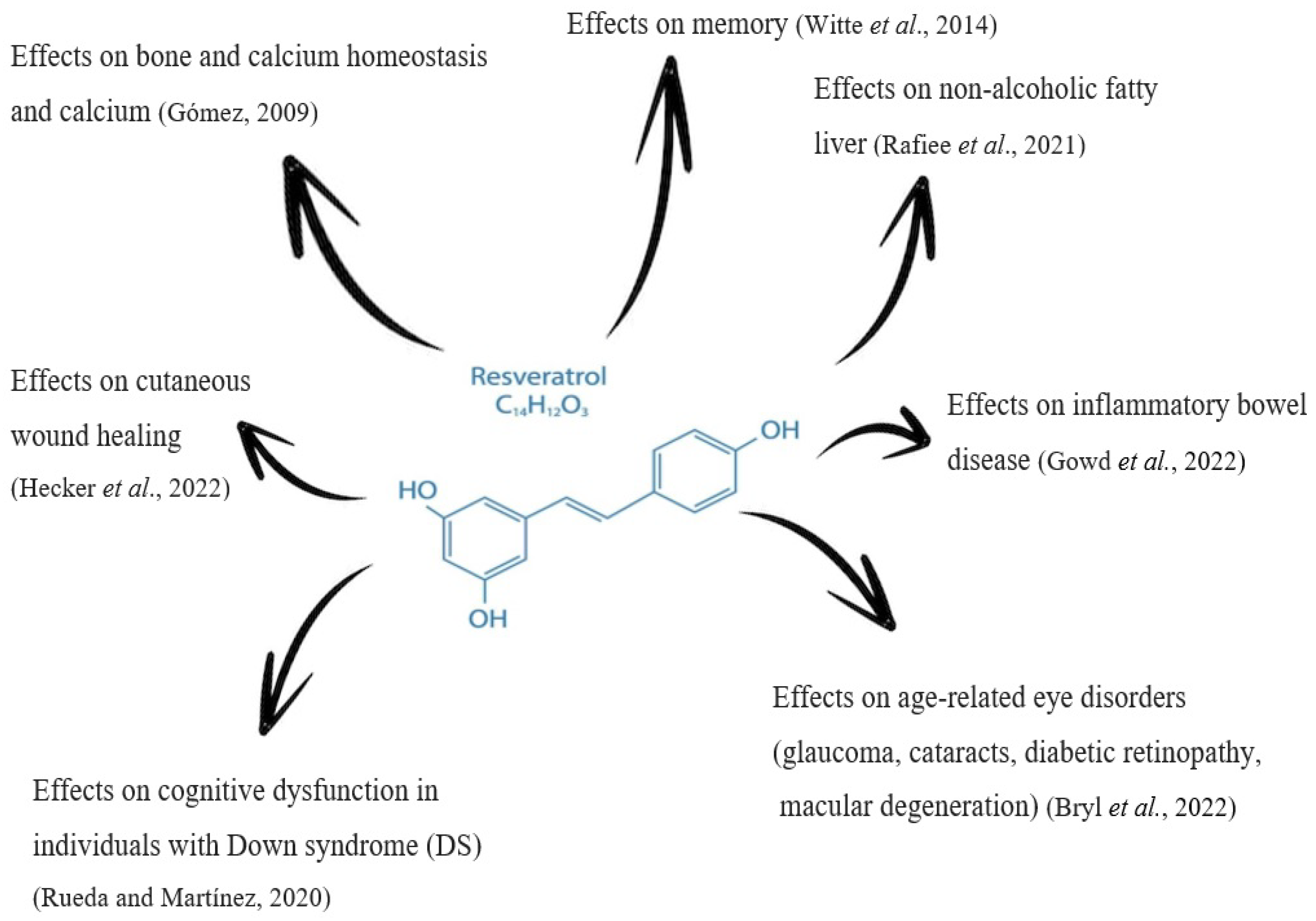

4. Physiological Functions of Resveratrol

4.1. Effect of Resveratrol in Cardiovascular Health

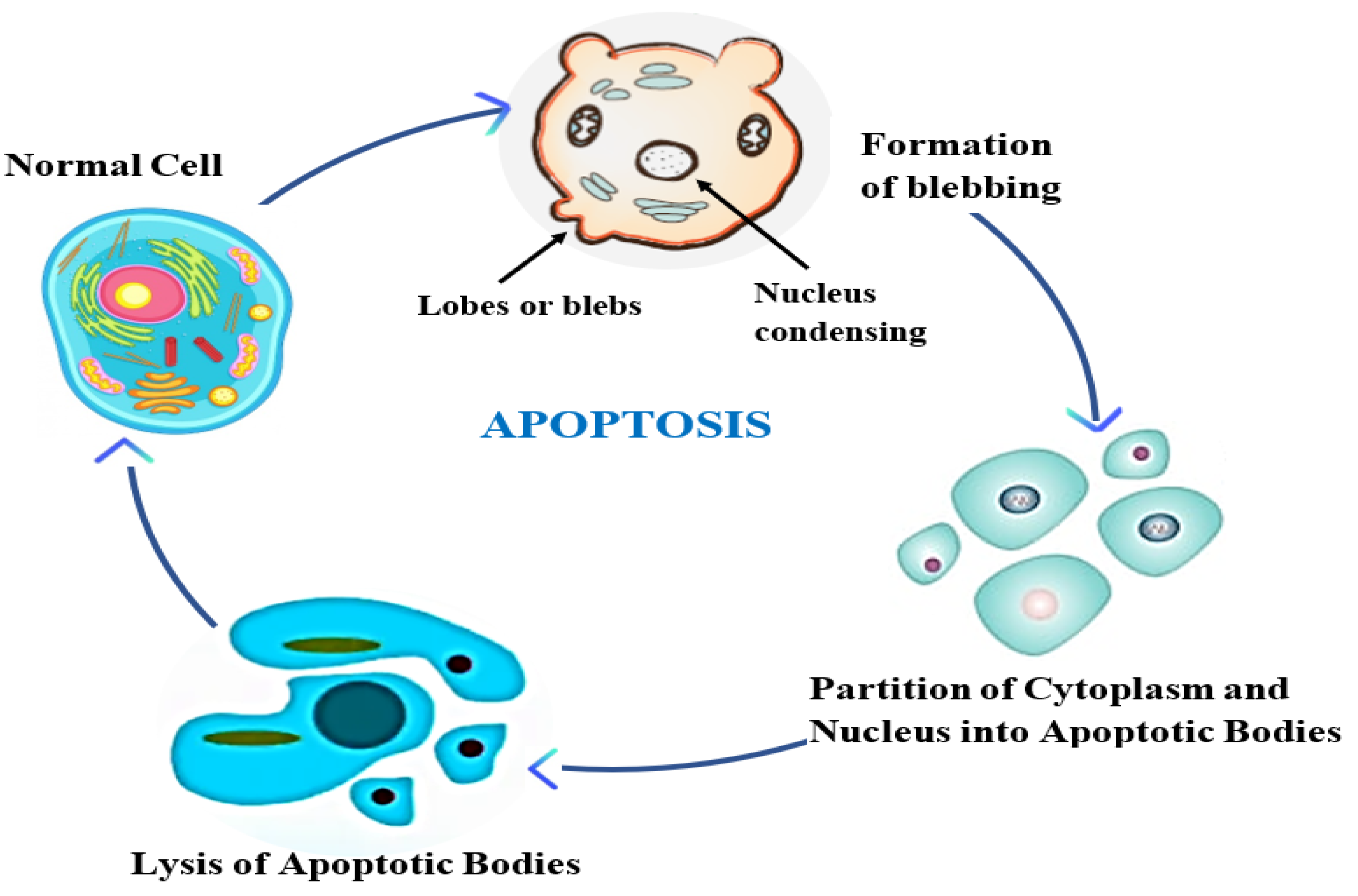

4.2. Effect of Resveratrol on Cancer

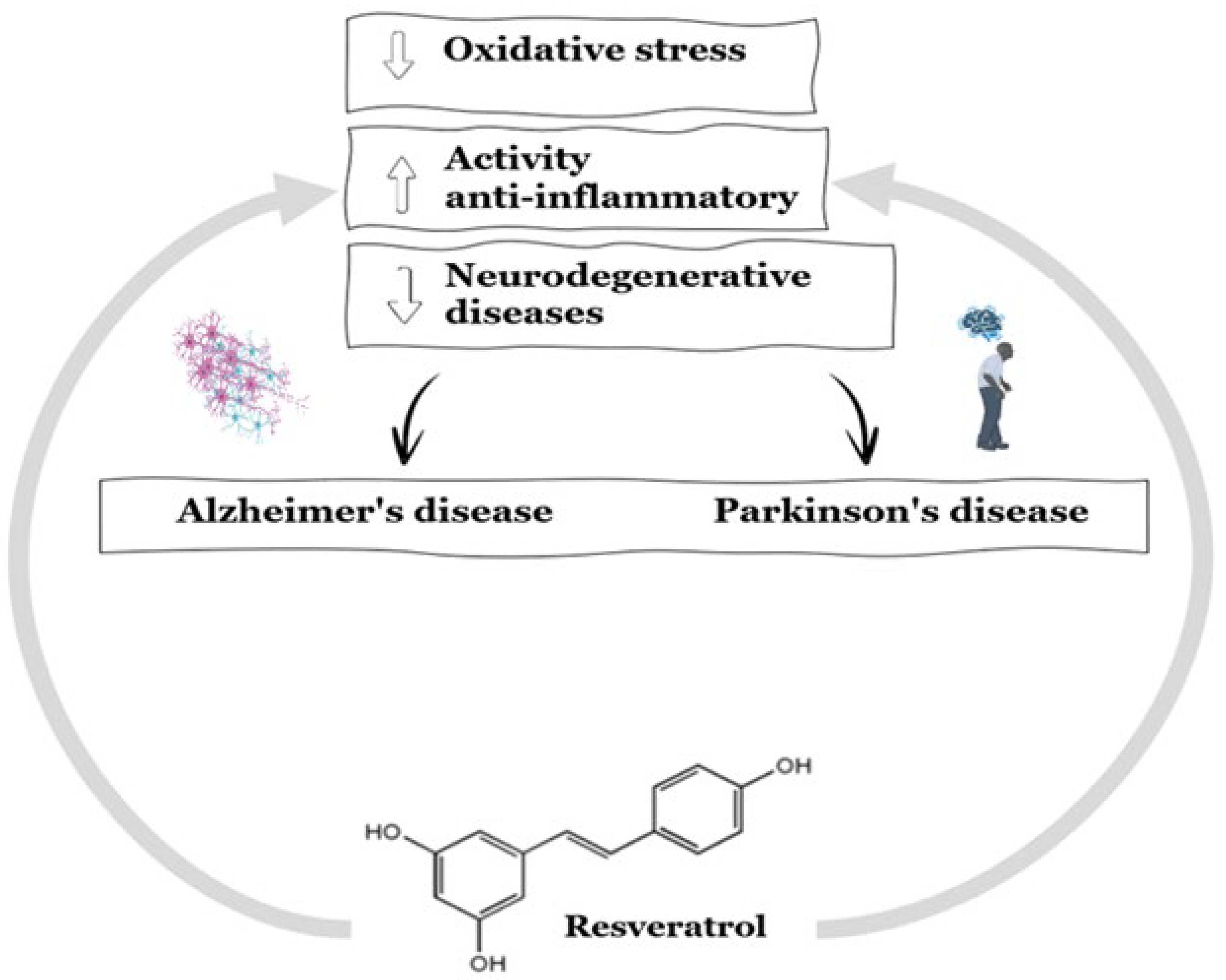

4.3. Effect of Resveratrol on Neurodegenerative Diseases

4.4. Effect of Resveratrol on Diabetes

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Competing Interests

References

- Agarwal, B.; Baur, J.A. Resveratrol and life extension. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2011, 1215, 138–143. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, B.B.; Bhardwaj, A.; Aggarwal, R.S.; Seeram, N.P.; Shishodia, S.; Takada, Y. Role of resveratrol in prevention and therapy of cancer: preclinical and clinical studies. Anticancer Res. 2004, 24, 2783–2840.

- Ashrafizadeh, M.; Ahmadi, Z.; Farkhondeh, T.; Samarghandian, S. Resveratrol targeting the Wnt signaling pathway: A focus on therapeutic activities. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 235, 4135–4145. [CrossRef]

- Bai, T.; Dong, D.-S.; Pei, L. Resveratrol mitigates isoflurane-induced neuroapoptosis by inhibiting the activation of the Akt-regulated mitochondrial apoptotic signaling pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2013, 32, 819–826. [CrossRef]

- Bastianetto, S.; Ménard, C.; Quirion, R. Neuroprotective action of resveratrol. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis. 2015, 1852, 1195–1201. [CrossRef]

- Baur, J.A.; Sinclair, D.A. Therapeutic potential of resveratrol: The in vivo evidence. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 493–506. [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, Z.E.; Pickering, J.; Eskiw, C.H. Better Living through Chemistry: Caloric Restriction (CR) and CR Mimetics Alter Genome Function to Promote Increased Health and Lifespan. Front. Genet. 2016, 7, 142. [CrossRef]

- Bryl, A.; Falkowski, M.; Zorena, K.; Mrugacz, M. The Role of Resveratrol in Eye Diseases—A Review of the Literature. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2974. [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, M. I. R., Vasco, M. P., Sánchez, M. B. and Botello, M. D. R. P. 2020. Revisión de los efectos beneficiosos/perjudiciales que aporta la ingesta de vino a los pacientes con diabetes. In XLI Jornadas de Viticultura y Enología de la Tierra de Barros (pp. 143-191). C.C. Santa Ana.

- Carradori, S., Fantacuzzi, M., Ammazzalorso, A., Angeli, A., De Filippis, B., Galati, S., Petzer, A., Petzer, J.P., Poli, G. and Tuccinardi, T. 2022. Resveratrol Analogues as Dual Inhibitors of Monoamine Oxidase B and Carbonic Anhydrase VII: A New Multi-Target Combination for Neurodegenerative Diseases? Molecules 27: 7816. [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, A., Carpéné, C. and Mercader, J. 2018. Resveratrol, Metabolic Syndrome, and Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 10 (11):1651.

- Cheong, H.; Ryu, S.-Y.; Kim, K.-M. Anti-Allergic Action of Resveratrol and Related Hydroxystilbenes. Planta Medica 1999, 65, 266–268. [CrossRef]

- Cortiñas, J.A.; Fernández-González, M.; González-Fernández, E.; Vázquez-Ruiz, R.A.; Rodríguez-Rajo, F.J.; Aira, M.J. Phenological behaviour of the autochthonous godello and mencía grapevine varieties in two designation origin areas of the NW Spain. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 265, 109221. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.A.C.; Fernández-González, M.; González-Fernández, E.; Vázquez-Ruiz, R.A.; Rodríguez-Rajo, F.J.; Aira, M.J. Potential Fertilization Capacity of Two Grapevine Varieties: Effects on Agricultural Production in Designation of Origin Areas in the Northwestern Iberian Peninsula. Agronomy 2020, 10, 961. [CrossRef]

- Cortiñas, J.A.; Fernández-González, M.; Vázquez-Ruiz, R.A.; Aira, M.J.; Rodríguez-Rajo, F.J. The understanding of phytopathogens as a tool in the conservation of heroic viticulture areas. Aerobiologia 2022, 38, 177–193. [CrossRef]

- Coveñas-Vilchez, C. L. 2023. Evaluación del efecto del resveratrol en la criopreservación de células madre espermatogoniales de Vicugna pacos (Linnaeus, 1758) “alpaca”. Facultad de Ciencias. Universidad de Perú.

- Cruz-Rosales, E. S. 2023. Efecto del resveratrol sobre la regulación de LIN28A en la línea celular de cáncer de mama T47D (Master's thesis, Tesis (MC)--Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del IPN Departamento de Genética y Biología Molecular).

- Cvejic, J.M.; Djekic, S.V.; Petrovic, A.V.; Atanackovic, M.T.; Jovic, S.M.; Brceski, I.D.; Gojkovic-Bukarica, L.C. Determination of trans- and cis-resveratrol in Serbian commercial wines.. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2010, 48, 229–234. [CrossRef]

- Das, D.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ray, D. Erratum to: Resveratrol and red wine, healthy heart and longevity. Hear. Fail. Rev. 2011, 16, 425–435. [CrossRef]

- de Lima, V. S., Bezerra, A. N., Albuquerque, N. V., Pereira, C. P., da Costa Alencar, C. M., Lima, A. T. A. and de Assis Ferreira, K. C. 2020. Efeitos da suplementação com polifenol resveratrol em pacientes com diabetes mellitus tipo 2: Uma revisão sistemática. Research, Society and Development 9(10), e3639108659-e3639108659.

- Di, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Shi, W. [Analysis for four isomers of resveratrol in red wine by high performance liquid chromatography].. 2004, 22, 424–7.

- Diaz-Costilla, K. S. 2021. Revisión crítica: Efecto de la suplementación con resveratrol en pacientes diagnosticados con diabetes mellitus tipo II. Revista Facultad de Ciencias. Universidad Norbert Wiener.

- Figueira, L. and González, J. C. 2022. Efecto antiinflamatorio y antioxidante del resveratrol en la aterosclerosis. Papel de la molécula de adhesión celular endotelial plaquetaria 1. Revista de la Facultad de Farmacia 85(1 and 2).

- Fontana, L.; Partridge, L. Promoting Health and Longevity through Diet: From Model Organisms to Humans. Cell 2015, 161, 106–118. [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). FAOSTAT. 2023. Food and agriculture data. https://www.fao.org/food-agriculture-statistics/en/.

- Frankel, E.; Waterhouse, A.; Kinsella, J. Inhibition of human LDL oxidation by resveratrol. Lancet 1993, 341, 1103–1104. [CrossRef]

- Gambini, J., López-Grueso, R., Olaso-González, G., Inglés, M., Abdelazid, K., El Alami, M., Bonet-Costa, V., Borrás, C. and Viña, J. 2013. Resveratrol: Distribución, propiedades y perspectivas. Revista española de geriatría y gerontología 48 (2): 79-88.

- Mishra, K.; Girdhani, S.; Bhosle, S.; Thulsidas, S.; Kumar, A. Potential of radiosensitizing agents in cancer chemo-radiotherapy. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2005, 1, 129–31. [CrossRef]

- Gómez, J. E. 2009. Efectos de los isómeros del resveratrol sobre la homeostasis del calcio y del óxido nítrico en células vasculares. Universidade Santiago de Compostela. http://hdl.handle.net/10347/2583.

- González-Pérez, J. 2023. Evaluación in vitro de una formulación de resveratrol como posible tratamiento de la retinopatía diabética. Universidad EIA.

- Gowd, V.; Kanika; Jori, C.; Chaudhary, A.A.; Rudayni, H.A.; Rashid, S.; Khan, R. Resveratrol and resveratrol nano-delivery systems in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2022, 109, 109101. [CrossRef]

- Gowd, V.; Kang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Chen, F.; Cheng, K.-W. Resveratrol: Evidence for Its Nephroprotective Effect in Diabetic Nephropathy. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2020, 11, 1555–1568. [CrossRef]

- Guarente, L. Sirtuins, Aging, and Metabolism. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2011, 76, 81–90. [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, A.R.; Chow, H.-H.S.; Martinez, J.A. Effects of resveratrol on drug- and carcinogen-metabolizing enzymes, implications for cancer prevention. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2017, 5, e00294. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Baek, K.-H. Induction of Resveratrol Biosynthesis in Grape Skins and Leaves by Ultrasonication Treatment. Korean J. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2013, 31, 496–502. [CrossRef]

- Hecker, A.; Schellnegger, M.; Hofmann, E.; Luze, H.; Nischwitz, S.P.; Kamolz, L.; Kotzbeck, P. The impact of resveratrol on skin wound healing, scarring, and aging. Int. Wound J. 2021, 19, 9–28. [CrossRef]

- Henz, T., Tres, L., Pagotto, P. and Carminatti, B. 2020. Nanotecnologias aplicadas a cosméticos e síntese do resveratrol: Uma revisão. Revista CIATEC-UPF, [S. I.], 12 (2): 29-40.

- Hernández, A. and Marina, A. 2023. Análisis del efecto del resveratrol como quimiosensibilizador en líneas celulares de cáncer cervicouterino a través de la inhibición de la vía de reparación NHEJ (Master's thesis, Tesis (MC)--Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del IPN Departamento de Genética y Biología Molecular.

- Hoca, M.; Becer, E.; Vatansever, H.S. The role of resveratrol in diabetes and obesity associated with insulin resistance. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 129, 555–561. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, T.-C.; Wu, J.M. Differential Effects on Growth, Cell Cycle Arrest, and Induction of Apoptosis by Resveratrol in Human Prostate Cancer Cell Lines. Exp. Cell Res. 1999, 249, 109–115. [CrossRef]

- International Organisation of Vine and Wine (OIV). 2023. https://www.oiv.int/what-we-do/statistics. Dijon (France).

- Jang, M.; Cai, L.; Udeani, G.O.; Slowing, K.V.; Thomas, C.F.; Beecher, C.W.W.; Fong, H.H.S.; Farnsworth, N.R.; Kinghorn, A.D.; Mehta, R.G.; et al. Cancer Chemopreventive Activity of Resveratrol, a Natural Product Derived from Grapes. Science 1997, 275, 218–220. [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.Y.; Im, E.; Kim, N.D. Mechanism of Resveratrol-Induced Programmed Cell Death and New Drug Discovery against Cancer: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13689. [CrossRef]

- Kapetanovic, I.M., Muzzio, M., Huang, Z., Thompson, T. and McCormick, D.L. 2011. Farmacocinética, biodisponibilidad oral y perfil metabólico del resveratrol y su análogo dimetiléter, pterostilbeno, en ratas. Quimioterapia contra el cáncer. Farmacéutico. 68: 593–601.

- Kosuru, R.; Rai, U.; Prakash, S.; Singh, A.; Singh, S. Promising therapeutic potential of pterostilbene and its mechanistic insight based on preclinical evidence. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 789, 229–243. [CrossRef]

- Kung, H.-C.; Lin, K.-J.; Kung, C.-T.; Lin, T.-K. Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Neuroprotection of Polyphenols with Respect to Resveratrol in Parkinson’s Disease. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 918. [CrossRef]

- Lasa, A.; Schweiger, M.; Kotzbeck, P.; Churruca, I.; Simón, E.; Zechner, R.; Portillo, M.d.P. Resveratrol regulates lipolysis via adipose triglyceride lipase. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 379–384. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yin, Y.; Ye, X.; Zeng, M.; Zhao, Q.; Keefe, D.L.; Liu, L. Resveratrol protects against age-associated infertility in mice. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 707–717. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; You, Y.; Lu, J.; Chen, X.; Yang, Z. Recent Advances in Synthesis, Bioactivity, and Pharmacokinetics of Pterostilbene, an Important Analog of Resveratrol. Molecules 2020, 25, 5166. [CrossRef]

- Llacuna, L. and Mach, N. 2012. Papel de los antioxidantes en la prevención del cáncer. Revista Española de Nutrición Humana y Dietética 16: 16-24.

- Londoño-David, L. M. and Torres Rivas, S. L. 2021. Ácido docosahexaenoico (DHA) y el resveratrol en el manejo de la angiogénesis a nivel ocular. Universidad Antonio Nariño. http://repositorio.uan.edu.co/handle/123456789/2667.

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The Hallmarks of Aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217. [CrossRef]

- Man, A.W.; Li, H.; Xia, N. Resveratrol and the Interaction between Gut Microbiota and Arterial Remodelling. Nutrients 2020, 12, 119. [CrossRef]

- Meng, T.; Xiao, D.; Muhammed, A.; Deng, J.; Chen, L.; He, J. Anti-Inflammatory Action and Mechanisms of Resveratrol. Molecules 2021, 26, 229. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.C.; Goel, M.; Barrow, C.J.; Deshmukh, S.K. Endophytic Fungi - An Untapped Source of Potential Antioxidants. Curr. Bioact. Compd. 2020, 16, 944–964. [CrossRef]

- Olesen, J.; Ringholm, S.; Nielsen, M.M.; Brandt, C.T.; Pedersen, J.T.; Halling, J.F.; Goodyear, L.J.; Pilegaard, H. Role of PGC-1α in exercise training- and resveratrol-induced prevention of age-associated inflammation. Exp. Gerontol. 2013, 48, 1274–1284. [CrossRef]

- Orallo, F. Comparative Studies of the Antioxidant Effects of Cis- and Trans- Resveratrol. Curr. Med. Chem. 2006, 13, 87–98. [CrossRef]

- Ozonas, R. and Angosto, M. C. 2016. Restricción calórica y longevidad. Anales de la Real Academia Nacional de Farmacia, 82: 76-86.

- https://www.analesranf.com/index.php/aranf/article/view/1770/1738.

- Öztürk, E.; Arslan, A.K.K.; Yerer, M.B.; Bishayee, A. Resveratrol and diabetes: A critical review of clinical studies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 95, 230–234. [CrossRef]

- Parraguez, J. and Andrés, S. 2022. Actividad antiagregante plaquetaria de inhibidores mitocondriales. Diss. Universidad de Talca (Chile). Escuela de Tecnología Médica.

- Paul, B.; Masih, I.; Deopujari, J.; Charpentier, C. Occurrence of resveratrol and pterostilbene in age-old darakchasava, an ayurvedic medicine from India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1999, 68, 71–76. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, B.; Nayak, R.; Patra, S.; Jit, B.P.; Ragusa, A.; Jena, M. Bioactive Metabolites from Marine Algae as Potent Pharmacophores against Oxidative Stress-Associated Human Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2020, 26, 37. [CrossRef]

- Raederstorff, D.; Kunz, I.; Schwager, J. Resveratrol, from experimental data to nutritional evidence: the emergence of a new food ingredient. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2013, 1290, 136–141. [CrossRef]

- Rafiee, S.; Mohammadi, H.; Ghavami, A.; Sadeghi, E.; Safari, Z.; Askari, G. Efficacy of resveratrol supplementation in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pr. 2020, 42, 101281. [CrossRef]

- Rayo Llenera, I. and Marín, E. 1998. Huerta Vino y corazón. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 51: 435-449.

- Ren, B.; Kwah, M.X.-Y.; Liu, C.; Ma, Z.; Shanmugam, M.K.; Ding, L.; Xiang, X.; Ho, P.C.-L.; Wang, L.; Ong, P.S.; et al. Resveratrol for cancer therapy: Challenges and future perspectives. Cancer Lett. 2021, 515, 63–72. [CrossRef]

- Rigon, R.B.; Fachinetti, N.; Severino, P.; Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Atanasov, A.G.; El Mamouni, S.; Chorilli, M.; Santini, A.; Souto, E.B. Quantification of Trans-Resveratrol-Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles by a Validated Reverse-Phase HPLC Photodiode Array. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4961. [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Aguilar, J.O.; Calderón-Santoyo, M.; Barros-Castillo, J.C.; Ragazzo-Sanchez, J.A. High-value biological compounds in jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam.) and their relationship with carcinogenesis. Rev. Bio Cienc. 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Revilla, N.R.; Martínez-Cué, C. Antioxidants in Down Syndrome: From Preclinical Studies to Clinical Trials. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 692. [CrossRef]

- Sabra, A.; Netticadan, T.; Wijekoon, C. Grape bioactive molecules, and the potential health benefits in reducing the risk of heart diseases. Food Chem. X 2021, 12, 100149. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Nieto, J. M., Itzel Sierra-Zurita, D., Ruiz-Ramos Mirna, M. and Mendoza-Núñez, V. M. 2023. Efecto del resveratrol sobre las funciones cognitivas en adultos mayores: Una revisión sistemática y metaanálisis. Nutrición Hospitalaria 40(6): 1253-1261.

- Santos, P. B. D. 2010. Efeito imunomodulatório do resveratrol em células do sistema imune in vitro e na administração via oral de ovalbumina em camundongos (Doctoral dissertation, Universidade de São Paulo).

- Bisbal, J.J.S.; Lloret, J.M.; Lozano, G.M.; Fagoaga, C. Especies vegetales como antioxidantes de alimentos. Nereis. Interdiscip. Ibero-American J. Methods, Model. Simulation. 2020, 71–90. [CrossRef]

- Iside, C.; Scafuro, M.; Nebbioso, A.; Altucci, L. SIRT1 Activation by Natural Phytochemicals: An Overview. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1225. [CrossRef]

- Bailo, P.S.; Martín, E.L.; Calmarza, P.; Breva, S.M.; Gómez, A.B.; Giráldez, A.P.; Callau, J.J.S.-P.; Santamaría, J.M.V.; Khialani, A.D.; Micó, C.C.; et al. Implicación del estrés oxidativo en las enfermedades neurodegenerativas y posibles terapias antioxidantes. Adv. Lab. Med. / Av. en Med. de Lab. 2022, 3, 351–360. [CrossRef]

- Kuršvietienė, L.; Stanevičienė, I.; Mongirdienė, A.; Bernatonienė, J. Multiplicity of effects and health benefits of resveratrol. Medicina 2016, 52, 148–155. [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Zhao, W.; Xu, S.; Weng, J. Resveratrol in Treating Diabetes and Its Cardiovascular Complications: A Review of Its Mechanisms of Action. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1085. [CrossRef]

- Hester, R.K. Naltrexone reduces heavy drinking in problem drinkers across the spectrum of dependence.. 2015, 76, e226–7. [CrossRef]

- Sung, B.; Chung, H.Y.; Kim, N.D. Role of Apigenin in Cancer Prevention via the Induction of Apoptosis and Autophagy. J. Cancer Prev. 2016, 21, 216–226. [CrossRef]

- Takaoka, M.J. 1940. Of the phenolic substances of white hellebore (Veratrum grandiflorum Loes.fil.). J Fac Sci Hokkaido Imp Univ. 3: 1-16.

- Tomás-Barberan, F. A. 2003. Los polifenoles de los alimentos y la salud. Alimentación, Nutrición y Salud. 10 (2): 41-53.

- Tovar, L. B. 2022. La muerte de las neuronas y las enfermedades de Alzheimer y Parkinson. Instituto de Geriatría. Gobierno Federal.

- Trela, B.C.; Waterhouse, A.L. Resveratrol: Isomeric Molar Absorptivities and Stability. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1996, 44, 1253–1257. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, A. P. 2021. Estrategias terapéuticas en un modelo experimental de caquexia cancerosa: Efectos de los polifenoles curcumina y resveratrol (Doctoral dissertation, Universitat Pompeu Fabra).

- Wada-Hiraike, O. Benefits of the Phytoestrogen Resveratrol for Perimenopausal Women. Endocrines 2021, 2, 457–471. [CrossRef]

- Wahab, A.; Gao, K.; Jia, C.; Zhang, F.; Tian, G.; Murtaza, G.; Chen, J. Significance of Resveratrol in Clinical Management of Chronic Diseases. Molecules 2017, 22, 1329. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xu, J.; Rottinghaus, G.E.; Simonyi, A.; Lubahn, D.; Sun, G.Y.; Sun, A.Y. Resveratrol protects against global cerebral ischemic injury in gerbils. Brain Res. 2002, 958, 439–447. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Klipfell, E.; Bennett, B.J.; Koeth, R.; Levison, B.S.; DuGar, B.; Feldstein, A.E.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Chung, Y.-M.; et al. Gut Flora Metabolism of Phosphatidylcholine Promotes Cardiovascular Disease. Nature 2011, 472, 57–63. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y. Gut microbiota derived metabolites in cardiovascular health and disease. Protein Cell 2018, 9, 416–431. [CrossRef]

- Weiskirchen, S. and Weiskirchen, R. 2016. Resveratrol: How much wine do you have to drink to stay healthy? Adv. Nutr. 7: 706–718. [CrossRef]

- Witte, A.V.; Kerti, L.; Margulies, D.S.; Flöel, A. Effects of Resveratrol on Memory Performance, Hippocampal Functional Connectivity, and Glucose Metabolism in Healthy Older Adults. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 7862–7870. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L., Chen, Q., Dong, B., Geng, H., Wang, Y., Han, D. and Jin, J. 2023. Resveratrol alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced liver injury by inducing SIRT1/P62-mediated mitophagy in gibel carp (Carassius gibelio). Frontiers in Immunology 14: 1177140.

- Yang, J.; Peng, S.; Zhang, B.; Houten, S.; Schadt, E.; Zhu, J.; Suh, Y.; Tu, Z. Human geroprotector discovery by targeting the converging subnetworks of aging and age-related diseases. GeroScience 2019, 42, 353–372. [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.C.; Barroso, M.F.; González-García, M.B.; Oliveira, M.B.P.; Delerue-Matos, C. New Trends in Food Allergens Detection: Toward Biosensing Strategies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 56, 2304–2319. [CrossRef]

- Yousef, M.; Vlachogiannis, I.A.; Tsiani, E. Effects of Resveratrol against Lung Cancer: In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1231. [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Sun, Z.-J.; Wu, S.-L.; Pan, C.-E. Effect of resveratrol on cell cycle proteins in murine transplantable liver cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2003, 9, 2341–2343. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.-D.; Luo, M.; Huang, S.-Y.; Saimaiti, A.; Shang, A.; Gan, R.-Y.; Li, H.-B. Effects and Mechanisms of Resveratrol on Aging and Age-Related Diseases. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 1–15. [CrossRef]

| Food | Resveratrol | Wine | Resveratrol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red cranberry | 3.00 mg/100 g | Red wine | 0.84-7.33 mg/1000 ml |

| Red currant | 1.57 mg/ 100 g | Rosé wine | 0.29 mg/1000 ml |

| Blueberry | 0.67 mg/ 100 g | White wine | 0-1.089 mg/ 1000 ml |

| Strawberry | 0.35 mg/ 100 g | Pinot noir | 6.25 mg/ 1000 ml |

| Peanuts | 0.07 mg/ 100 g | Merlot | 5.05 mg/1000 ml |

| Pure cocoa | 0.04 mg/ 100 g | Cabernet sauvignon | 1.71 mg/1000 ml |

| Peanut butter | 0.04 mg/ 100 g | Garnacha | 2.86 mg/1000 ml |

| Apple | 400 µg / 1000 g | Tempranillo | 4.14 mg/1000 ml |

| Tomato skins | 19 µg / 1 g | trans-Resveratrol | 3.06 mg/1000 ml |

| Beer | 1.34-77.0 µg / 1000 ml | cis-Resveratrol | 1.08 mg/1000 ml |

| Dark chocolate | 350 µg/ 1000 g | Wines with carbonic | 4.96 mg/1000 ml |

| Milk chocolate | 100 µg/ 1000 g | ||

| Itadori tea | 68 µg/ 100 ml | Wines aged in oak | 1.98 mg/1000 ml |

| Black grapes | 0.15 mg/ 100 g | ||

| White grapes | 0.03 mg/ 100 g |

| Biological actions of resveratrol to be highlighted | Ref. |

|---|---|

| In vitro studies | |

| Actions against cancer at different stages (initiation, promotion and progression of tumour cells). | Rivera-Aguilar et al., 2023 |

| Antithrombotic effect (platelet aggregator). | Wada-Hiraike, 2021 |

| Action on lipid metabolism, regulating lipolysis by increasing the mobilisation of fats in adipocytes. | Lasa et al.,2011 Parraguez and Andrés, 2022 |

| Has anti-allergic effects. | Cheong et al., 1999 Santos, 2010 |

| Osteogenesis and prevention of adipogenesis in stem cells | Coveñas Vilchez, 2023 |

| Elimination of human cancer cells through programmed cell death (PCD) mechanisms such as apoptosis, autophagy, and necroptosis. | Sung et al., 2016 |

| Treatment of diabetic retinopathy. | González-Pérez, 2023 |

| Anti-inflammatory action, regulatory mechanisms and immunomodulatory function. | Meng et al., 2021 |

| In vivo studies | |

| Chemoprotective agent against different diseases such as retinal degeneration. | Baur and Sinclair, 2006 Londoño and Torres, 2021 |

| Diabetes in mechanisms related to insulin secretion and obesity related to insulin resistance. | Su et al., 2022 Hoca et al., 2023 |

| Platelet anti-aggregant. | Wang et al., 2002 Wada-Hiraike, 2021 |

| Mechanism of human SIRT1 activation by resveratrol. | Agarwal and Baur, 2011 |

| Mimetic effects of calorie restriction. | Agarwal and Baur, 2011 |

| Anti-inflammatory action, regulatory mechanisms and immunomodulatory role. | Meng et al., 2021 |

| Action on cognitive functions. | Sánhez-Nieto et al., 2023 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).