Submitted:

18 April 2024

Posted:

22 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Expert Opinions on Solid Tumor Therapy

1.2. Objectives

2. Danger of Information-Generating Approaches to Cancer Biology: The Current State of Confusion

2.1. Off-Target Effects of Drugs Designed for Targeted Therapies

2.2. Precision Oncology for Treating Patients with Solid Tumors: Ever-Increasing Information and More (Empty) Promises

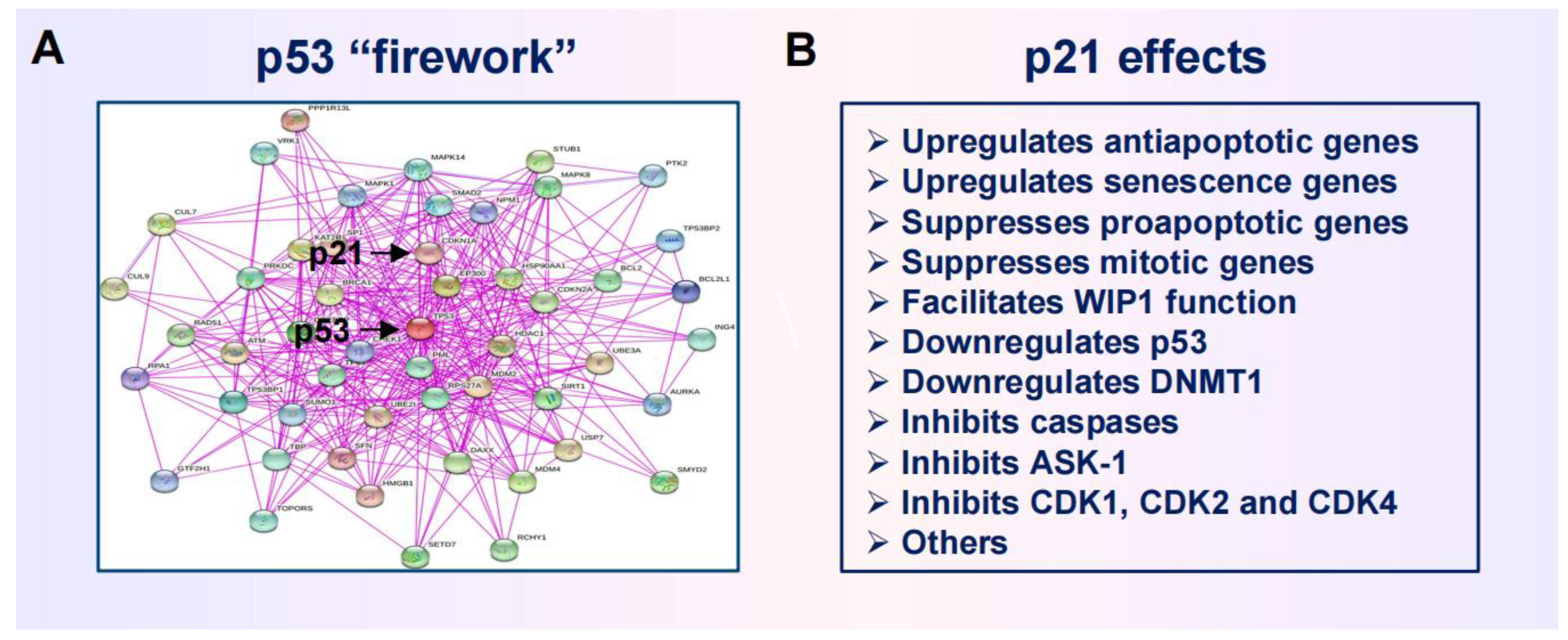

2.3. Anticancer Strategies Targeting the p53 “Firework”

3. Impact of Genome Chaos on Cancer Cell Resistance To Therapeutic Agents

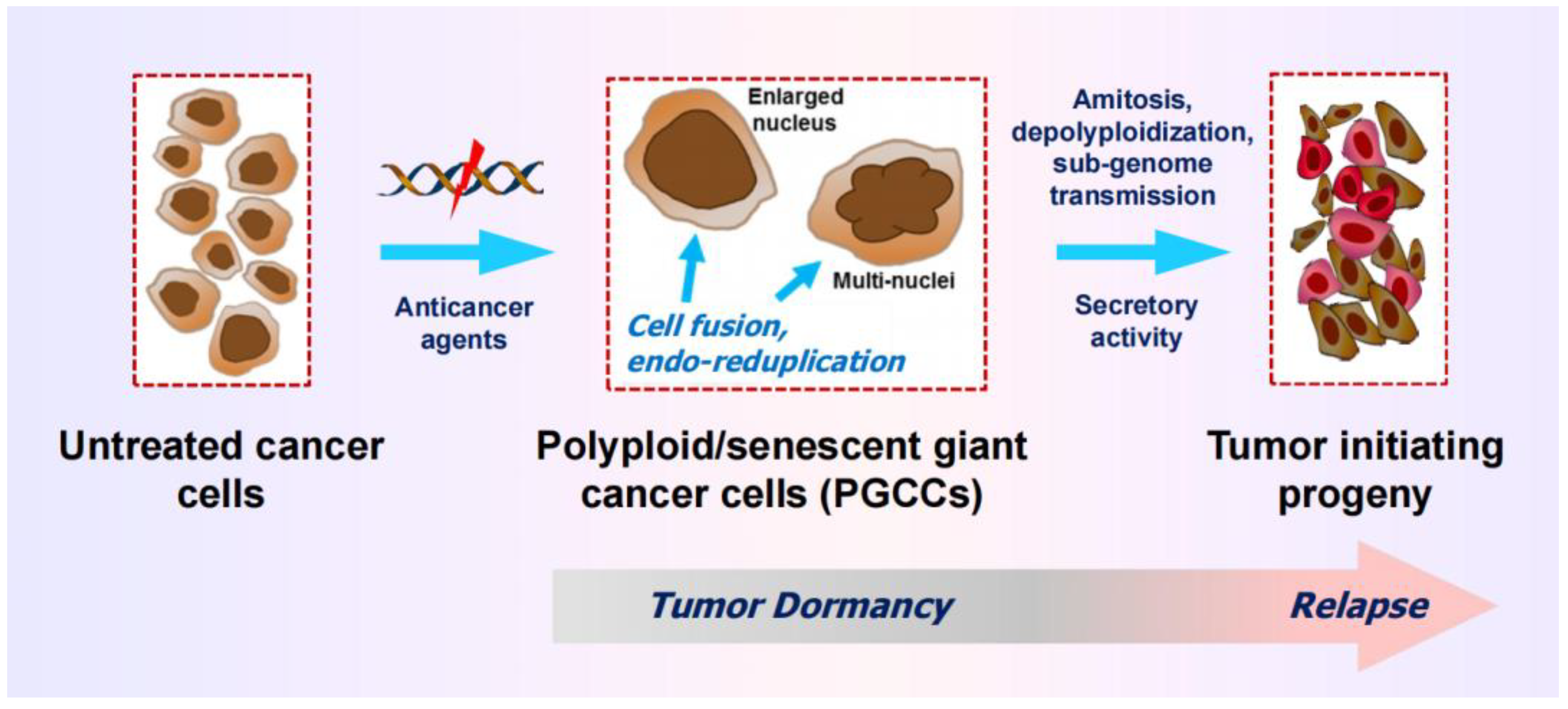

3.1. Therapy-Induced Dormancy via polyploidy/Multinucleation

3.2. The Creation of PGCCs Complicates the Interpretation of Chemosensitivity Data

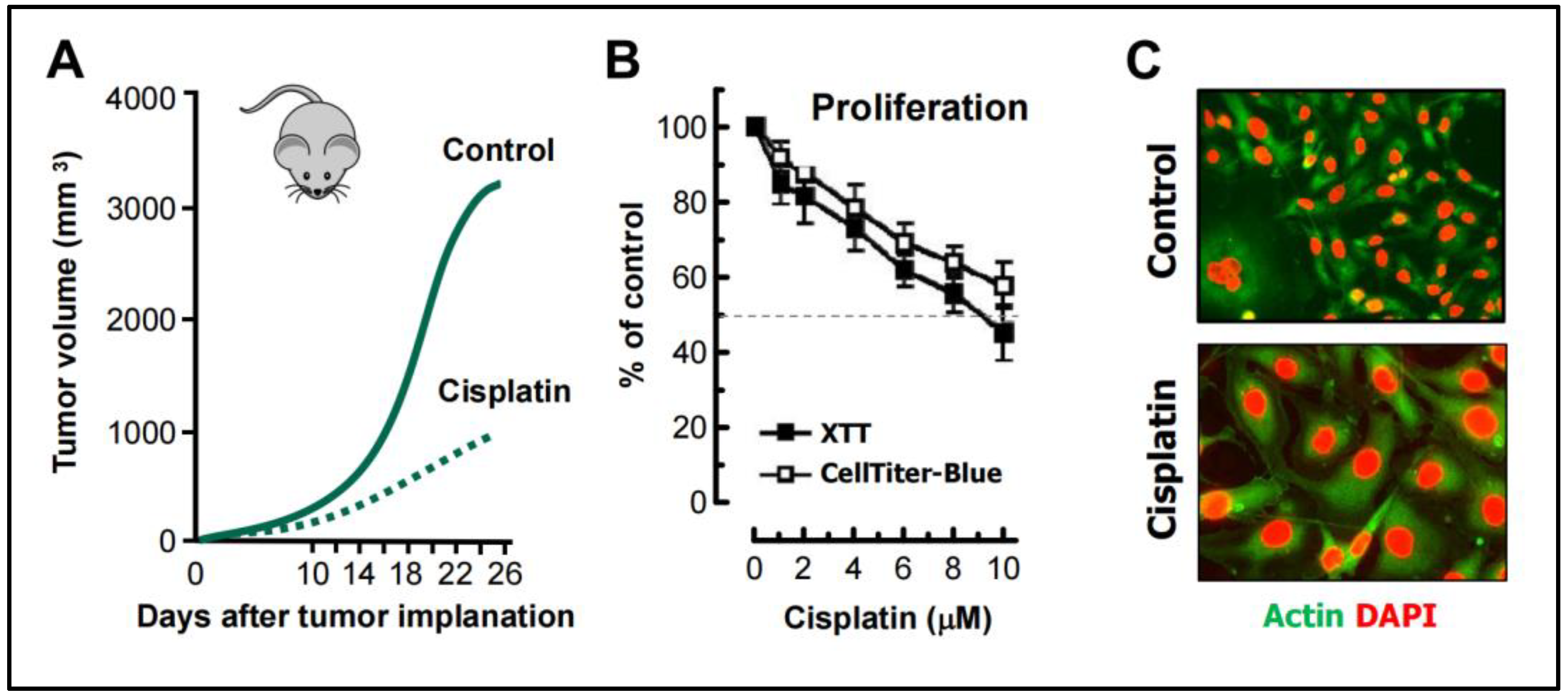

- Weng et al [68] studied the mechanism of cisplatin resistance in B16-F10 (mouse melanoma) cells grown in C57BL (immune proficient) mice. As expected, cisplatin treatment resulted in significant reduction (by ~75%) of tumor volume compared to the control group (Figure 5A). Tumors in cisplatin-treated mice were highly enriched with PGCCs which were shown to be more malignant than the parental cancer cells. A similar observation was reported by Puig et al [70] with a rat colon carcinoma isografts established in immunocompetent rats. In the latter study, tumor repopulation resulting from PGCCs was observed late times (>40 days) after cisplatin treatment (for details, see [25]).

- Figure 5B shows cisplatin sensitivity of MDA-MB-231 breast carcinoma cells evaluated by the 96-well plate XTT and CellTiter-Blue assays. The IC50 (half-maximum inhibitory concentration) vales were ~10 µM.

- Further studies involving single cell assays demonstrated that cisplatin sensitivity reflected proliferation arrest via the creation of PGCCs (predominantly mononucleated giants; Figure 5C), and that virtually all emerging PGCCs remained adherent to the culture dish and remained viable and metabolically active [69].

3.3. Common Features of PGCCs and Senescent Cancer Cells

4. Rethinking Pro-Apoptotic Strategies to Combat Solid Tumors

4.1. Dark side of Apoptosis in Solid Tumor Therapy

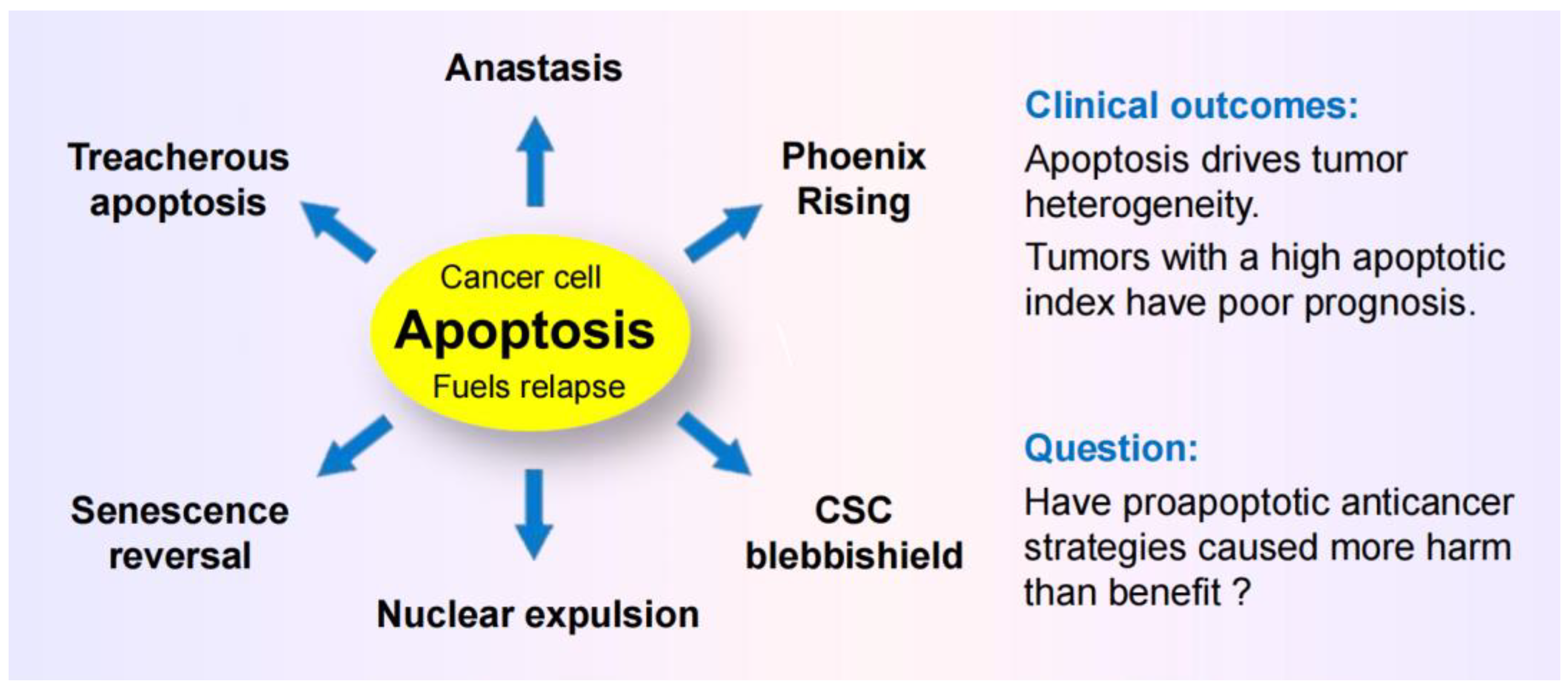

- Caspase 3, which has canonically served as a marker of programmed cell death, is known to promote survival through processes that are called “Phoenix Rising” [82,88,89] or “Failed Apoptosis” [80,83,86]. These processes are initiated by DNA double-strand breaks (e.g., arising in the course of regulated cell death), resulting in activation of stress response signaling pathways (e.g., orchestrated by ATM) and caspase 3-mediated secretion of prostaglandine E2 and other prosurvival factors. (This calls for revisiting thousands of articles that have relied on caspase 3 activation as a marker of cell “lethality.”)

- The term “anastasis” refers to a homeostatic process that enables mammalian cells to recover after engaging regulated cell death [81,84,85,87,94,95]]. Like prosurvival function of caspase 3, anastasis poses an obvious challenge in cancer therapy. Thus, cancer cells triggered to undergo apoptosis (e.g., in response to chemotherapeutic drugs) can recover from late stages of apoptosis (even after formation of apoptotic bodies) [91,94] and give rise to aggressive variants with increased aneuploidy [94,95]. (This calls for revisiting thousands of articles that use the terms “apoptosis” and “lethality” interchangeably!)

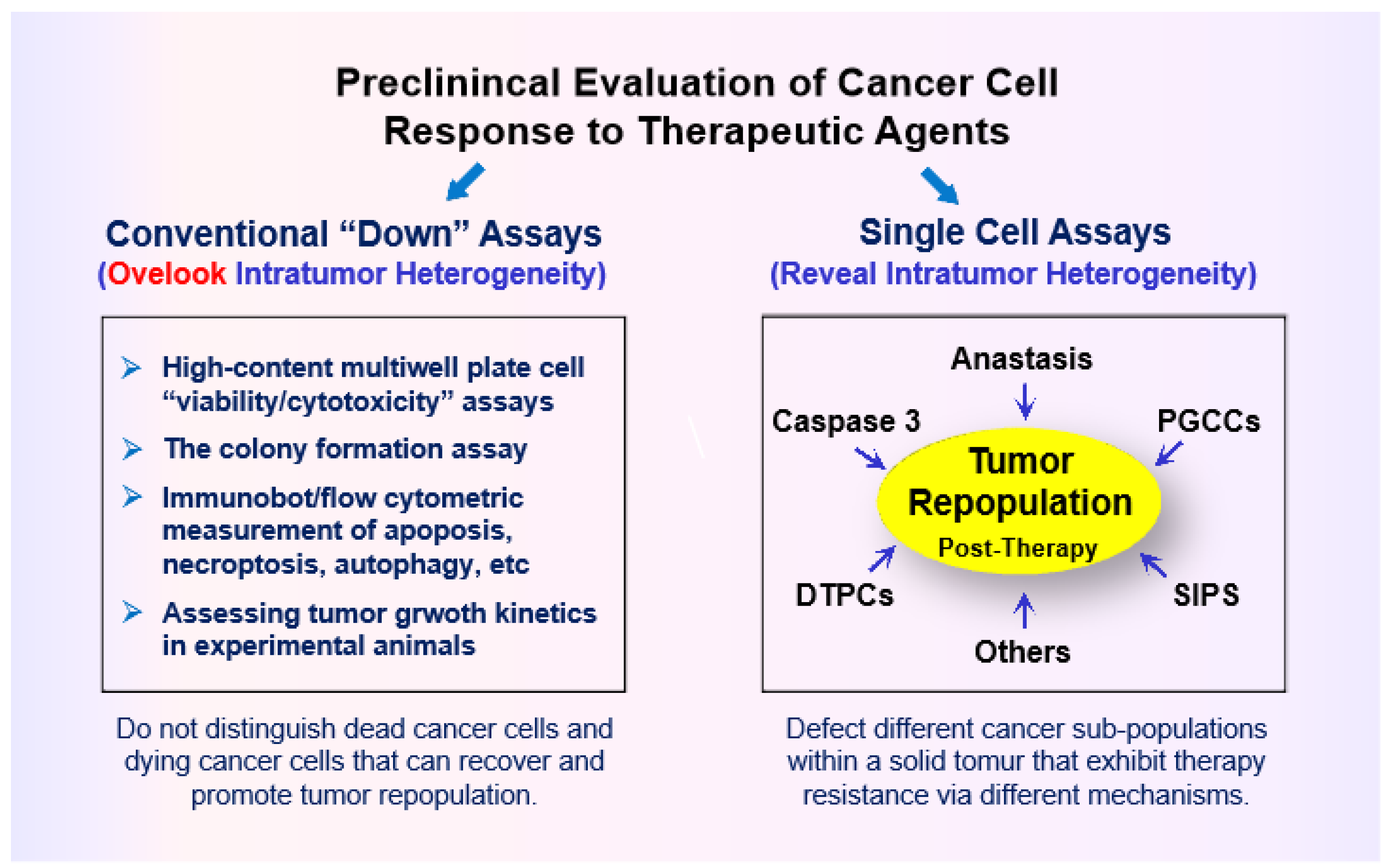

- Studies with adenocarcinoma tumor samples have revealed the presence of densely populated apoptotic cells within an individual tumor [96]. Such “apoptotic islands” contribute to intratumor heterogeneity and are associated with cancer cell survival [96]. This process of cancer cell survival - called “Treacherous Apoptosis” by Dhanasekaran [90] - cannot be recapitulated by the conventional preclinical “down” assays listed in Figure 1.

- In a recent report, Park et al [97] demonstrated that apoptotic cancer cells can promote metastasis through a process called nuclear expulsion. This involves the release of chromatin and associated proteins (nuclear expulsion products; NEPs) by apoptotic cells, which bind to neighboring cancer cells and leads to their metastatic outgrowth in an ERK-dependent manner. NEPs were detected in cancer cell lines as well as tumor biopsies from patients with different types of solid tumors. The authors concluded that apoptosis-induced nuclear expulsion might be a generalized phenotype in cancer that underlies metastatic spread. The relationship (if any) between this process and treacherous apoptosis remains to be determined.

- Clinical studies reported since the 1990s have revealed that solid tumors with high apoptotic index tend to have a poor prognosis. The dark side of apoptosis based on clinical outcomes was well documented over a decade ago [98,99,100], and has been fairly recently reviewed for colon cancer [101,102] and breast cancer [103,104,105].

4.2. Cancer Stem Cell Survival after Engaging Apoptosis

4.3. Questions

5. Exploiting the Apoptotic Threshold for Managing Solid Tumors

5.1. Apoptosis-Promoting Preclinical Chemosensitivity Studies Often Generate Clinically Irrelevant Information

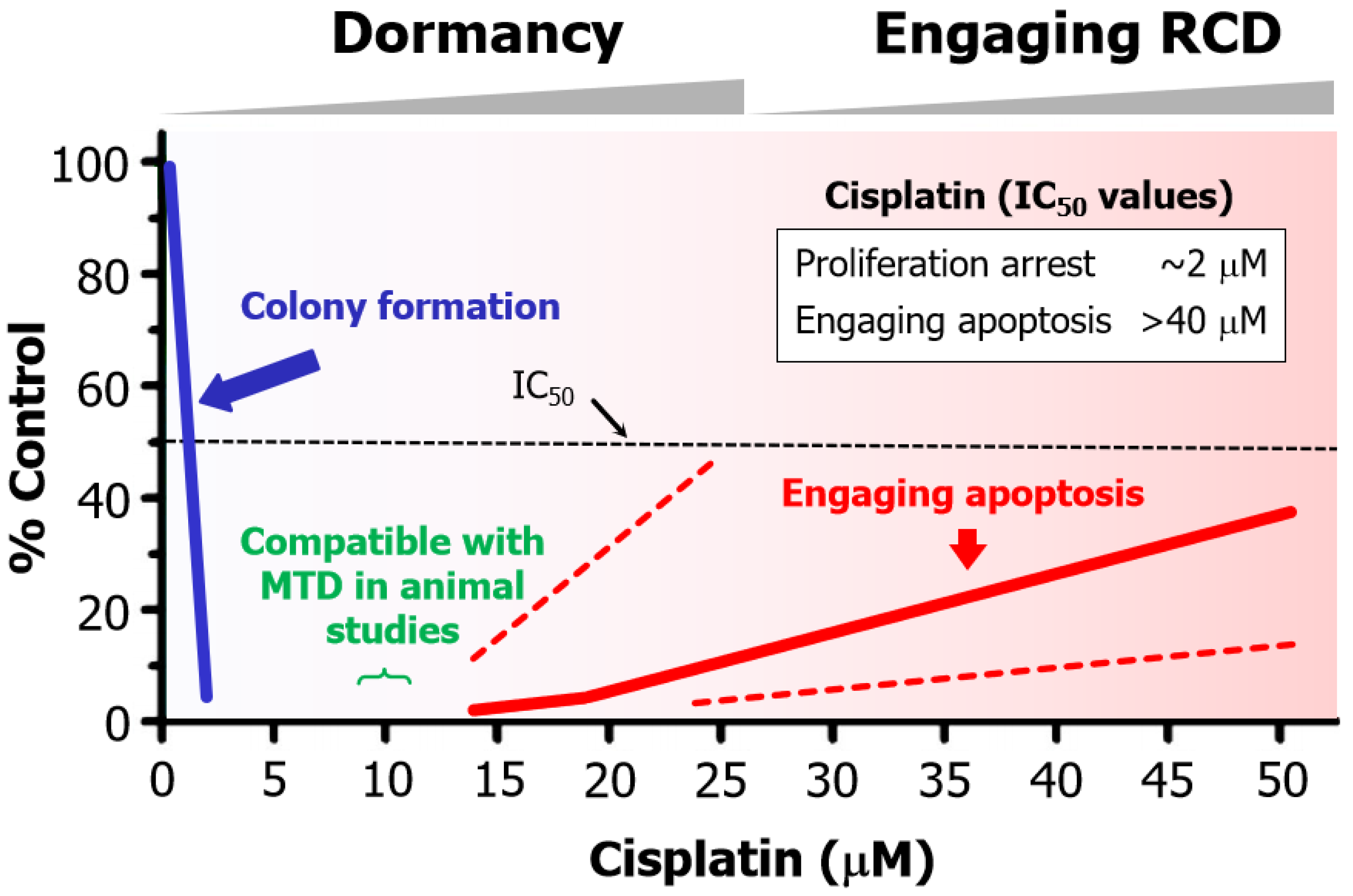

- Cisplatin concentrations between 5 and 10 µM used in cell-based studies are determined to be comparable to concentrations that may be achieved in tumor/tissues of treated patients and tumor-bearing laboratory animals [70]. Higher concentrations result in severe side effects in animal studies [70]. Thus, ~10 µM cisplatin is denoted as the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) in Figure 6.

- The basis for this discrepancy is known [109]. Relatively low concentrations of cisplatin induce sufficient amounts of DNA lesions that inhibit cell proliferation, whereas very high drug concentrations are needed to damage the cytoplasmic compartments to engage apoptosis.

5.2. Chemotherapy-Induced Cancer Cell Dormancy: lesser Evil Than Apoptosis?

6. Conclusions

6.1. Preclinical “Down” Assays have Caused More Harm Than Benefit

6.2. Conflicting Reports on Cancer Cell Fate After Engaging Apoptosis

6.3. Intratumor Heterogeneity: How Complex Does it Get?

6.4. Where Will All This Lead?

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Prasad, V. Perspective: The precision-oncology illusion. Nature 2016, 537, S63. [CrossRef]

- Szabo, L. Cancer treatment hype gives false hope to many patients. Kaiser Health News (2017)https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2017/04/27/cancer-treatment-hype-gives-false-hope-many-patients/100972794/ (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Maeda, H.; Khatami, M. Analyses of repeated failures in cancer therapy for solid tumors: Poor tumor-selective drug delivery, low therapeutic efficacy and unsustainable costs. Clin. Transl. Med. 2018, 7, 11.

- Joyner, M.J.; Paneth, N. Promises, promises, and precision medicine. J. Clin. Invest. 2019, 129, 946–948.

- Marine, J.-C.; Dawson, S.-J.; Dawson, M.A. Non-genetic mechanisms of therapeutic resistance in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 743–756. [CrossRef]

- Pich, O.; Bailey, C.; Watkins, T.B.K.; Zaccaria, S.; Jamal-Hanjani, M.; Swanton, C. The translational challenges of precision oncology. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 458–478. [CrossRef]

- Heng, J.; Heng, H.H. Genome chaos, information creation, and cancer emergence: Searching for new frameworks on the 50th anniversary of the “war on cancer”. Genes 2022, 13, 101.

- Lohse, S. Mapping uncertainty in precision medicine: A systematic scoping review. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2023, 29, 554–564. [CrossRef]

- Fojo, T. Journeys to failure that litter the path to developing new cancer therapeutics. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2324949. [CrossRef]

- Suehnholz, S.P.; Nissan, M.H.; Zhang, H.; Kundra, R.; Nandakumar, S.; Lu, C.; Carrero, S.; Dhaneshwar, A.; Fernandez, N.; Xu, B.W.; et al. Quantifying the expanding landscape of clinical actionability for patients with cancer. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14, 49–65. [CrossRef]

- Kailen, W.G. Preclinical cancer target validation: How not to be wrong. NIH Wednesday Afternoon Lectures (WELS) series, January 24, 2018 [https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=27066] (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Belluz, J. Most cancer drugs fail in testing. This might be a big reason why. Science _VOX blog (2019) https://www.vox.com/2019/9/16/20864066/cancer-studies-fail (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Horgan, J. The cancer industry: hype vs. reality. Cancer medicine generates enormous revenues but marginal benefits for patients (2020) https://www.scientificamerican.com/blog/cross-check/the-cancer-industry-hype-vs-reality/ (accessed 15 April 2024).

- Horgan, J. The cancer industry: Hype versus reality (2023) https://johnhorgan.org/cross-check/the-cancer-industry-hype-versus-reality (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Azra, R. The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last. New York, Basic Books, 2019.

- Lin, A.; Giuliano, C.J.; Palladino, A.; John, K.M.; Abramowicz, C.; Yuan, M.L.; Sausville, E.L.; Lukow, D.A.; Liu, L.; Chait, A.R.; et al. Off-target toxicity is a common mechanism of action of cancer drugs undergoing clinical trials. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaaw8412. [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Gao, W.; Hu, H.; Zhou, S. Why 90% of clinical drug development fails and how to improve it? Acta. Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 3049−3062.

- Sadri, A. Is target-based drug discovery efficient? Discovery and “off-target” mechanisms of all drugs. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 12651−12677. [CrossRef]

- Bruin, M.A.C.; Sonke, G.S.; Beijnen, J.H.; Huitema, A.D.R. Pharmacokinetics and harmacodynamics of PARP inhibitors in oncology. Clin, Pharmacokinet. 2022, 61, 1649–1675.

- Mirzayans, R.; Murray, D. Intratumor heterogeneity and therapy resistance: Contributions of dormancy, apoptosis reversal (anastasis) and cell fusion to disease recurrence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1308. [CrossRef]

- Mirzayans, R. When therapy-induced cancer cell apoptosis fuels tumor relapse. Onco 2024, 4, 37–45. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, R.A. Coming full circle-from endless complexity to simplicity and back again. Cell 2014, 157, 267–271. [CrossRef]

- Kailen, W.G. Publish Houses of Brick, not Mansions of Straw. Nature 2017, 5454, 387.

- Mirzayans, R.; Murray, D. What are the reasons for continuing failures in cancer therapy? Are misleading/inappropriate preclinical assays to be blamed? Might some modern therapies cause more harm than benefit? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13217.

- Mirzayans, R.; Murray, D. Intratumor heterogeneity and treatment resistance of solid tumors with a focus on polyploid/senescent giant cancer cells (PGCCs). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11534. [CrossRef]

- Kastenhuber, E.R.; Lowe, S.W. Putting p53 in context. Cell 2017, 170, 1062–1078. [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V.N. p53 proteoforms and intrinsic disorder: An illustration of the protein structure-function continuum concept. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1874. [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, A.; Iwakuma, T. Emerging non-canonical functions and regulation of p53. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1015. [CrossRef]

- Horvat, A.; Tadijan, A.; Vlaši´c, I.; Slade, N. p53/p73 Protein network in colorectal cancer and other human malignancies. Cancers 2021, 13, 2885.

- Montero-Calle, A.; Garranzo-Asensio, M.; Torrente-Rodríguez, R.M.; Ruiz-Valdepeñas Montiel, V.; Poves, C.; Dziaková, J.; Sanz, R.; Díaz del Arco, C.; Pingarrón, J.M.; Fernández-Aceñero, M.J.; et al. p53 and p63 Proteoforms Derived from Alternative Splicing Possess Differential Seroreactivity in Colorectal Cancer with Distinct Diagnostic Ability from the Canonical Proteins. Cancers 2023, 15, 2102. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M. Census and evaluation of p53 target genes. Oncogene 2017, 36, 3943–3956. [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Sai, Y.; Zhou, L.; Liu, Z.; Du, P.; Wu, J.; Zhang, J. Current insights into the regulation of programmed cell death by TP53 mutation in cancer. Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 1023427.

- Levine, A.J.; Berger, S.L.The interplay between epigenetic changes and the p53 protein in stem cells. Genes Dev. 2017, 31, 1195–1201. [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, J.E.; Reich, N.O. p53 and TDG are dominant in regulating the activity of the human de novo DNA methyltransferase DNMT3A on nucleosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100058. [CrossRef]

- Murray, D.; Mirzayans, R.; McBride, W.H. Defenses against pro-oxidant forces—Maintenance of cellular and genomic integrity and longevity. Radiat. Res. 2018, 190, 331–349. [CrossRef]

- Markowska, M.; Budzinska, M.A.; Coenen-Stass, A.; Kang, S.; Kizling, E.; Kolmus, K.; Koras, K.; Staub, E.; Szczurek, E. Synthetic lethality prediction in DNA damage repair, chromatin remodeling and the cell cycle using multi-omics data from cell lines and patients. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 7049. [CrossRef]

- Vitale, I.; Pietrocola, F.; Guilbaud, E.; Aaronson, S.A.; Abrams, J.M.; Adam, D.; Agostini, M.; Agostinis. P.; Alnemri. E.S.; Altucci, L.; et al. Apoptotic cell death in disease-Current understanding of the NCCD 2023. Cell Death Differ. 2023, 30, 1097−1154. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, U.; Roy, R.; Ghosh, S.; Chakrabarti, G. The interplay between autophagy and apoptosis: its implication in lung cancer and therapeutics. Cancer Lett. 2024, 585, 21666. [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.; Kin, T.; Beck, W.T. Impact of complex apoptotic signaling pathways on cancer cell sensitivity to therapy. Cancers 2024, 16, 984. [CrossRef]

- Newton, K.; Strasser, A.; Kayagaki, N.; Dixit, V.M. Cell death. Cell 2024, 187, 235−256.

- Kayagaki, N.; Webster, J.D.; Newton, K. Control of cell death in health and disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2024, 19, 157−180. [CrossRef]

- Kulbay, M.; Paimboeuf, A.; Ozdemir, D.; Bernier, J. Review of cancer cell resistance mechanisms to apoptosis and actual targeted therapies. J. Cell. Biochem. 2022; 123, 1736–1761. [CrossRef]

- Tuval, A.; Strandgren, C.; Heldin, A.; Palomar-Siles, M.; Wiman, K.G. Pharmacological reactivation of p53 in the era of precision anticancer medicine. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 21, 106–120. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, M.; Wei, H.; Chen, Y. Targeting p53 pathways: mechanisms, structures, and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 92. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, T.; Su, W.; Dou, Z.; Zhao, D.; Jin, X.; Lei, H.; Wang, J.; Xie, X.; Cheng, B.; et al. Mutant p53 in cancer: from molecular mechanism to therapeutic modulation. Cell Death and Dis. 2022, 13, 974. [CrossRef]

- Levine, A.J. Targeting the p53 protein for cancer therapies: The translational impact of p53 research. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 362–364. [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.W.; Beatty, P.H.; Lewis, J.D. Molecular targeting of the most functionally complex gene in precision oncology: p53. Cancers 2022, 14, 5176. [CrossRef]

- Murai, J.; Pommier, Y. BRCAness, homologous recombination deficiencies, and synthetic lethality. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 1173–1174.

- Groelly, F.J.; Fawkes, M.; Dagg, R.A.; Blackford, A.N.; Tarsounas, M. Targeting DNA damage response pathways in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2023, 23, 78–94. [CrossRef]

- Cong, K.; Cantor, S.B. Exploiting replication gaps for cancer therapy. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 2363–2369. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Pan, W.; Xing, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, J.; Xu, Z. Recent advances in DDR (DNA damage response) inhibitors for cancer therapy. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 230, 114109. [CrossRef]

- Yap, T.A.; Plummer, R.; Azad, N.S.; Helleday, T. The DNA Damaging Revolution: PARP Inhibitors and Beyond. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2019, 39, 185–195. [CrossRef]

- Lord. C.J.; Ashworth, A. PARP Inhibitors: The first synthetic lethal targeted therapy. Science 2017, 355, 1152–1158.

- O’Neil, N.J.; Bailey, M.L.; Hieter, P. Synthetic lethality and cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2017, 18, 613-623.

- Heng, J.; Heng, H.H. Genome chaos, information creation, and cancer emergence: searching for new frameworks on the 50th anniversary of the “war on cancer”. Genes 2022, 13, 101.

- Heng, H.H. Genome Chaos: Rethinking Genetics, Evolution, and Molecular Medicine; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; p. 556.

- Ye, C.J.; Sharpe, Z.; Alemara, S.; Mackenzie, S.; Liu, G.; Abdallah, B.; Horne, S.; Regan, S.; Heng, H.H. Micronuclei and genome chaos: Changing the system inheritance. Genes 2019, 10, 366. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, J.A. How chaotic is genome chaos? Cancers 2021, 13, 1358.

- Liu, J.; Erenpreisa, J.; Sikora, E. Polyploid giant cancer cells: An emerging new field of cancer biology. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 81, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- 60Erenpreisa, J.; Cragg, M.S. Three steps to the immortality of cancer cells: Senescence, polyploidy and self-renewal. Cancer Cell Int. 2013, 13, 92. [CrossRef]

- Coward, J.; Harding, A. Size does matter: Why polyploid tumor cells are critical drug targets in the war on cancer. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 123. [CrossRef]

- Amend, S.R.; Torga, G.; Lin, K.C.; Kostecka, L.G.; de Marzo, A.; Austin, R.H.; Pienta, K.J. Polyploid giant cancer cells: Unrecognized actuators of tumorigenesis, metastasis, and resistance. Prostate 2019, 79, 1489–1497. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Niu, N.; Zhang, J.; Qi, L.; Shen, W.; Donkena, K.V.; Feng, Z.; Liu, J. Polyploid giant cancer cells (PGCCs): The evil roots of cancer. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2019, 19, 360–367. [CrossRef]

- Dudkowska, M.; Staniak, K.; Bojko, A.; Sikora, E. Chapter Five - The role of autophagy in escaping therapy-induced polyploidy/senescence Author links open overlay panel. Adv. Cancer Res. 2021, 150, 209–247.

- Zhang, J.; Qiao, Q.; Xu, H.; Zhou, R.;Liu, X. Human cell polyploidization: The good and the evil. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 81, 54–63. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Niu, N.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Sood, A.K. The life cycle of polyploid giant cancer cells and dormancy in cancer: Opportunities for novel therapeutic interventions. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 81, 132–144. [CrossRef]

- Trabzonlu, L.; Pienta, K.J.; Trock, B.J.; De Marzo, A.M.; Amend. S.R. Presence of cells in the polyaneuploid cancer cell (PACC) state predicts the risk of recurrence in prostate cancer. Prostate 2023, 83, 277–285. [CrossRef]

- Weng, C.H.; Wu, C.S.; Wu, J.c.; Kung, M. L; Wu, M.H.; Tai, M.H. Cisplatin-induced giant cells formation is involved in chemoresistance of melanoma cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7892. [CrossRef]

- Mirzayans, R.; Andrais, B.; Murray, D. Impact of chemotherapeutic drugs on cancer cell proliferation, morphology and metabolic activity. J. Cancer Biol. Res. 2018, 6, 1118.

- Puig, P.E.; Guilly, M.N.; Bouchot, A.; Droin, N.; Cathelin, D.; Bouyer, F.; Favier, L.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Kroemer, G.; Solary, E.; et al. Tumor cells can escape DNA-damaging cisplatin through DNA endoreduplication and reversible polyploidy. Cell Biol. Int. 2008, 32, 1031–1043. [CrossRef]

- Roninson, I.B. Tumor cell senescence in cancer treatment. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 2705–2715.

- Barley, R.D.C.; Enns, L.; Paterson, M.C.; Mirzayans, R. Aberrant p21WAF1-dependent growth arrest as the possible mechanism of abnormal resistance to ultraviolet light cytotoxicity in Li-Fraumeni syndrome fifibroblast strains heterozygous for TP53 mutations. Oncogene 1998, 17, 533–543.

- Brown, J.M.; Wouters, B.G. Apoptosis, p53, and tumor cell sensitivity to anticancer agents. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 1391–1399.

- te Poele, R.H.; Okorokov, A.L.; Jardine, L.; Cummings, J.; Joe,l S.P. DNA damage is able to induce senescence in tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 1876–83.

- Yang, L.; Fang, J.; Chen, J. Tumor cell senescence response produces aggressive variants. Cell Death Discov. 2017, 3, 17049. [CrossRef]

- Tonnessen-Murray, C.A.; Frey, W.D.; Rao, S.G.; Shahbandi, A.; Ungerleider, N.A.; Olayiwola, J.O.; Murray, L.B.; Vinson, B.T.; Chrisey, D.B.; Lord, C.J.; Jackson, J.G. hemotherapy-induced senescent cancer cells engulf other cells to enhance their survival. J. Cell Biol. 2019, 218, 3827–3844.

- Was, H.; Czarnecka, J.; Kominek, A.; Barszcz, K.; Bernas, T.; Piwocka, K.; Kaminska, B. Some chemotherapeutics-treated colon cancer cells display a specific phenotype being a combination of stem-like and senescent cell features. Cancer Biol. The. 2018, 19, 63–75. [CrossRef]

- Czarnecka-Herok, J.; Sliwinska, M.A.; Herok, M.; Targonska, A.; Strzeszewska-Potyrala, A.; Bojko, A.; Wolny, A.; Mosieniak, G.; Sikora, E. Therapy-induced senescent/polyploid cancer cells undergo atypical divisions associated with altered expression of meiosis, spermatogenesis and EMT genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8288. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.C.; Cullen, S.P.; Martin, S.J. Apoptosis: controlled demolition at the cellular level. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 231–241. [CrossRef]

- Ichim, G.; Tait, S.W.G. A fate worse than death: apoptosis as an oncogenic process. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 539–548. [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.M.; Tang, H.L. Anastasis: Recovery from the brink of cell death. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 180442.

- Zhao, R.; Kaakati, R.; Lee, A.K.; Liu, X.; Li, F.; Li, C.-Y. Novel roles of apoptotic caspases in tumor repopulation, epigenetic reprogramming, carcinogenesis, and beyond. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2018, 37, 227–236. [CrossRef]

- Berthenet, K.; Castillo Ferrer, C.; Fanfone, D.; Popgeorgiev, N.; Neves, D.; Bertolino, P.; Gibert, B.; Hernandez-Vargas, H.; Ichim, G. Failed apoptosis enhances melanoma cancer cell aggressiveness. Cell Rep. 2020, 31, 107731. [CrossRef]

- Mirzayans, R.; Murray, D. Do TUNEL and other apoptosis assays detect cell death in preclinical studies? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9090.

- Zaitceva, V.; Kopeina, G.S.; Zhivotovsky, B. Anastasis: Return journey from cell death. Cancers 2021, 13, 3671. [CrossRef]

- Castillo Ferrer, C.; Berthenet, K.; Ichim, G. Apoptosis—Fueling the oncogenic fire. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 4445–4463.

- Mohammed, R.N.; Khosravi, M.; Rahman, H.S.; Adili, A.; Kamali, N.; Soloshenkov, P.P.; Thangavelu, L.; Saeedi, H.; Shomali, N.; Tamjidifar, et. al. Anastasis: cell recovery mechanisms and potential role in cancer. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 20, 81.

- Corsi, F.; Capradossi, F.; Pelliccia, A.; Briganti, S.; Bruni, E.; Traversa, E.; Torino, F.; Reichle, A.; Ghibelli, L. Apoptosis as driver of therapy-induced cancer repopulation and acquired cell-resistance (CRAC): A simple in vitro model of Phoenix Rising in prostate cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1152. [CrossRef]

- Eskandari, E.; Eaves, C.J. Paradoxical roles of caspase-3 in regulating cell survival, proliferation, and tumorigenesis. J. Cell Biol. 2022, 221, e202201159. [CrossRef]

- Dhanasekaran, R. Treacherous apoptosis—Cancer cells sacrifice themselves at the altar of heterogeneity. Hepatolog. 2022, 76, 549–550. [CrossRef]

- Jinesh, G.G.; Brohl, A.S. Classical epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and alternative cell death process-driven blebbishield metastatic-witch (BMW) pathways to cancer metastasis. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 296. [CrossRef]

- Kalkavan, H.; Rühl, S.; Shaw, J.J.P.; Green, D.R. Non-lethal outcomes of engaging regulated cell death pathways in cancer. Nat. Cancer 2023, 4, 795–806. [CrossRef]

- Nano, M.; Montell, D.J. Apoptotic signaling: Beyond cell death. Semin, Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 156, 22–34. [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.L.; Tang, H.M.; Mak, K.H.; Hu, S.; Wang, S.S.; Wong, K.M.; Wong, C.S.T.; Wu, H.Y.; Law, H.T.; Liu, K.; et al. Cell survival, DNA damage, and oncogenic transformation after a transient and reversible apoptotic response. Mol. Biol. Cell 2012, 23, 2240–2252. [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.M.; Talbot, C.C., Jr.; Fung, M.C.; Tang, H.L. Molecular signature of anastasis for reversal of apoptosis. F1000Research 2017, 6, 43.

- Khatib, S.A.; Ma, L.; Dang, H.; Forgues, M.; Chung, J.-Y.; Ylaya, K.; Hewitt, S.M.; Chaisaingmongkol, J.; Rucchirawat, M.; Wang, X.W. Single-cell biology uncovers apoptotic cell death and its spatial organization as a potential modifier of tumor diversity in HCC. Hepatology 2022, 76, 599–611. [CrossRef]

- Park, W.Y.; Gray, J.M.; Holewinski, R.J.;Andresson, T.; So, J.S.; Carmona-Rivera, C.; Hollander, M.C.; Yang, H.H.; Lee, M.; Kaplan, M.J.; et al. Apoptosis-induced nuclear expulsion in tumor cells drives S100a4-mediated metastatic outgrowth through the RAGE pathway. Nat. Cancer 2023, 4, 419–435. [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, M.P.V. The dark side of apoptosis. In Molecular Mechanisms of Tumor Cell Resistance to Chemotherapy, Resistance to Targeted Anti-Cancer Therapeutics 1; Bonavida, B., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 245–258.

- Wang, R.A.; Li, Q.L.; Li, Z.S.; Zheng, P.J.; Zhang, H.Z.; Huang, X.F.; Chi, S.M.; Yang, A.G.; Cui, R. Apoptosis drives cancer cells proliferate and metastasize. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2013, 17, 205–211. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.A.; Li, Z.S.; Yan, Q.G.; Bian, X.W.; Ding, Y.Q.; Du, X.; Sun, B.C.; Zhang, X.H. Resistance to apoptosis should not be taken as a hallmark of cancer. Chin. J. Cancer 2014, 33, 47–50. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Li, S.; Cheng, I.; Deng, M.; He, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, C.H.; Zhao, X.Y.; Huang, J. High expression of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 is a good prognostic factor in colorectal cancer: Result of a metaanalysis.World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 5018–5033. [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, L.; Meyer, M.; Fay, J.; Curry, S.; Bacon, O.; Duessmann, H.; John, K.; Boland, K.C.; McNamara, D.A.; Kay, E.W.; et al. Low levels of Caspase-3 predict favourable response to 5FU-based chemotherapy in advanced colorectal cancer: Caspase-3 inhibition as a therapeutic approach. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2087. [CrossRef]

- Pu, X.; Storr, S.J.; Zhang, Y.; Rakha, E.A.; Green, A.R.; Ellis, I.O.; Martin, S.G. Caspase-3 and caspase-8 expression in breast cancer: caspase-3 is associated with survival. Apoptosis 2017, 22, 357–368. [CrossRef]

- Lindner, A.U.; Lucantoni, F.; Varešlija, D.; Resler, A.; Murphy, B.M.; Gallagher, W.M.; Hill, a.D.K.; Young, L.S.; Prehn, J.H.M. Low cleaved caspase-7 levels indicate unfavourable outcome across all breast cancers. Mol. Med. 2018, 96, 1025–1037. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhong, D.N.; Qin, H.; Wu, P.R.; Wei, K.L.; Chen, G.; He, R.Q.; Zhong, J.C. Caspase-3 over-expression is associated with poor overall survival and clinicopathological parameters in breast cancer: a meta-analysis of 3091 cases. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 8629–8641. [CrossRef]

- Jinesh, G. G.; Kamat, A. M. Endocytosis and serpentine filopodia drive blebbishield-mediated resurrection of apoptotic cancer stem cells. Cell Death Disco. 2016, 2, 15069. [CrossRef]

- Elmore, S. Apoptosis: A review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007, 35, 495–516. [CrossRef]

- Mirzayans, R.; Andrais, B.; Kumar, P.; Murray, D. The growing complexity of cancer cell response to DNA-damaging agents: Caspase 3 mediates cell death or survival? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 708.

- Berndtsson, M.; Hägg, M.; Panaretakis, T.; Havelka, A.M.; Shoshan, M.C.; Linder, S. Acute apoptosis by cisplatin requires induction of reactive oxygen species but is not associated with damage to nuclear DNA. Int. J. Cancer 2007, 120, 175–180. [CrossRef]

- 1Murray, D.; Mirzayans, R. Cellular responses to platinum-based anticancer drugs and UVC: Role of p53 and implications for cancer therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5766. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.L.; Liu, J.P.; Bao, R.X.; Yan, G.Q.; Feng, X.; Xu, Y.P.; Sun, Y.P.; Yan, W.; Ling, A.Q.; Xiong, Y.; et al. Acetylation accumulates PFKFB3 in cytoplasm to promote glycolysis and protects cells from cisplatin-induced apoptosis. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 508. [CrossRef]

- Barkinge, J.L.; Gudi, R.; Sarah, H.; Chu, F.; Borthakur, A.; Prabhakar, B.S.; Prasad, K.V.S. The p53 induced Siva-1 plays a signifi cant role in cisplatin-induced apoptosis. J. Carcinog. 2009, 8, 2.

- Zhang, H.; Sun, J.; Ma, R.; Zhao, S. Role of episamarcandin in promoting the apoptosis of human colon cancer HCT116 cells through the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2021, 2021, 9663738. [CrossRef]

- Eastman, A. Improving anticancer drug development begins with cell culture: Misinformation perpetrated by the misuse of cytotoxicity assays. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 8854–8866. [CrossRef]

- Nicoletto, R.E.; Ofner, C.M. Cytotoxic mechanisms of doxorubicin at clinically relevant concentrations in breast cancer cells. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2022, 89, 285–311. [CrossRef]

- Gourdier, I.; Crabbe, L.; Andreau, K.; Pau, B.; Kroemer, G. Oxaliplatin-induced mitochondrial apoptotic response of colon carcinoma cells does not require nuclear DNA. Oncogene 2004, 23, 7449–7457. [CrossRef]

- Mirzayans, R. When Therapy-Induced Cancer Cell Apoptosis Fuels Tumor Relapse. Onco. 2024, 4, 37–45. [CrossRef]

- Jänicke, R.U.; Sohn, D.; Schulze-Osthoff, K. The dark side of a tumor suppressor: Anti-apoptotic p53. Cell Death Differ. 2008, 15, 959–976. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.; Altschuler, S.J.; Wu, L.F. Patterns of early p21 dynamics determine proliferation-senescence cell fate after chemotherapy. Cell 2019, 178, 361–373. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).