Submitted:

16 April 2024

Posted:

17 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

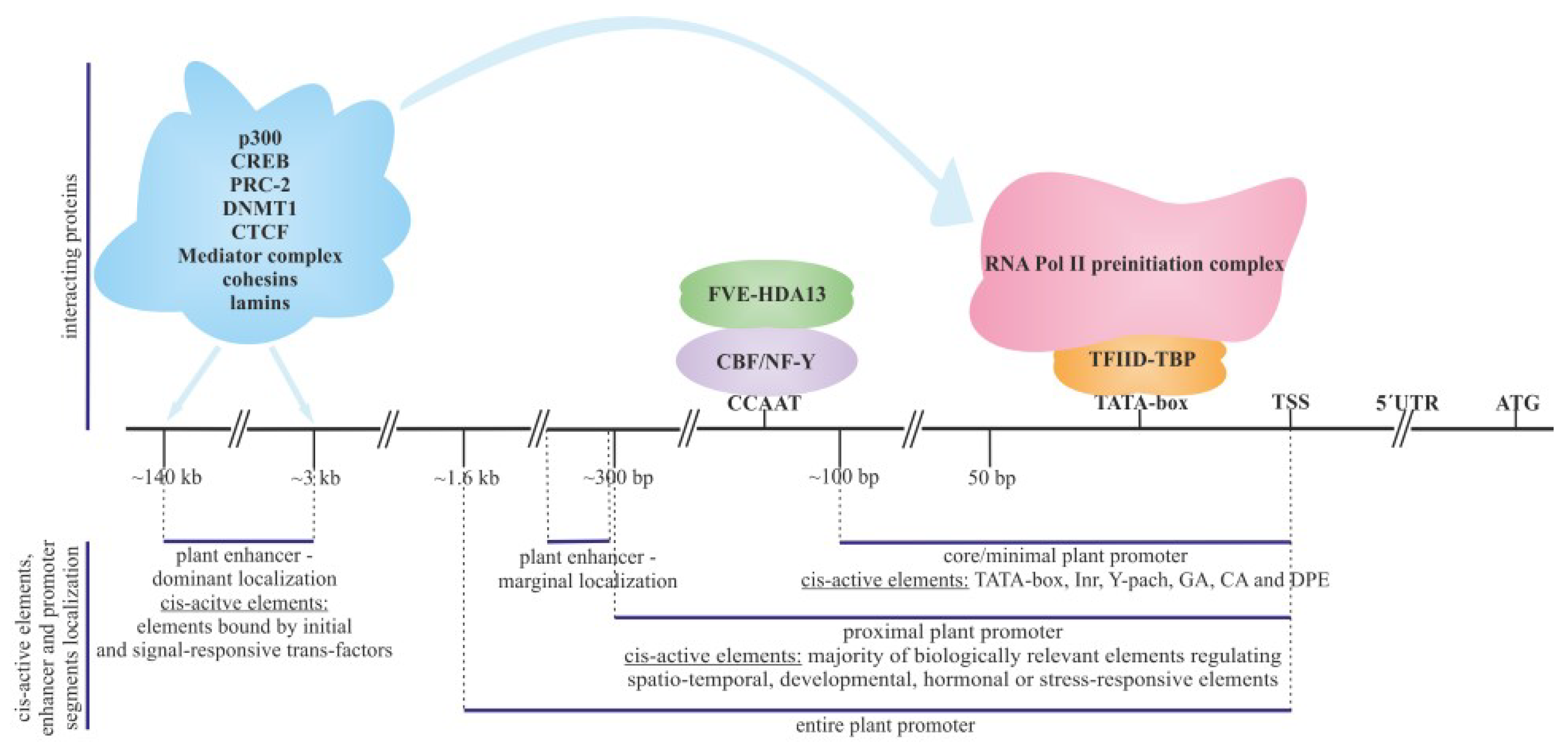

2. Sections of Plant Promoters

2.1. Core Promoter

2.2. Proximal Promoter

2.3. Plant Enhancers

3. Objectives and General Methodology of Synthetic Promoter Creating

3.1. Methods of Synthetic Promoter Generating

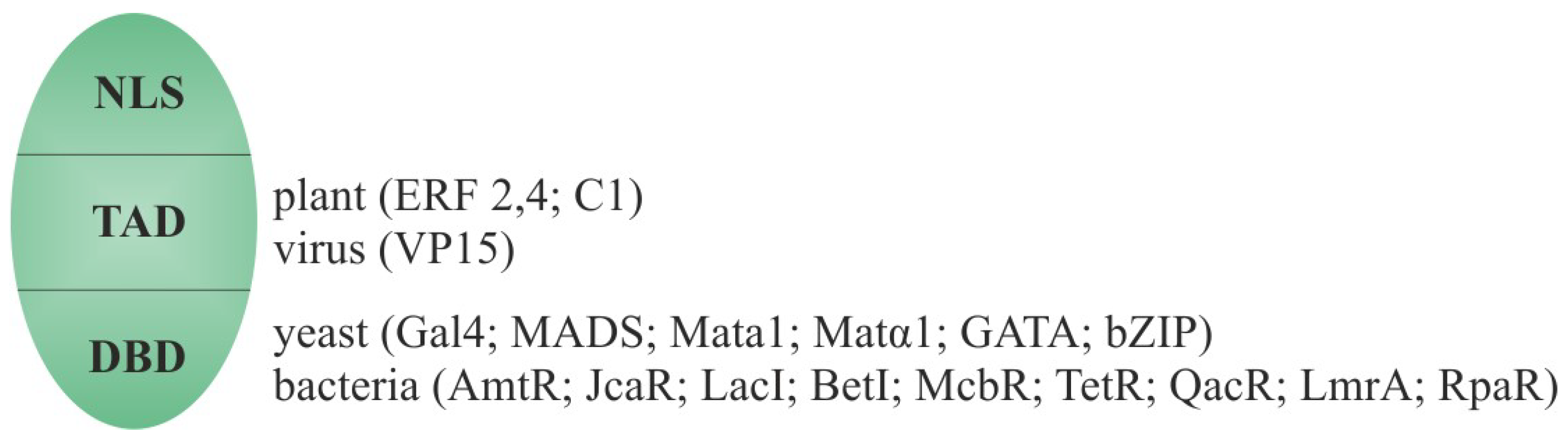

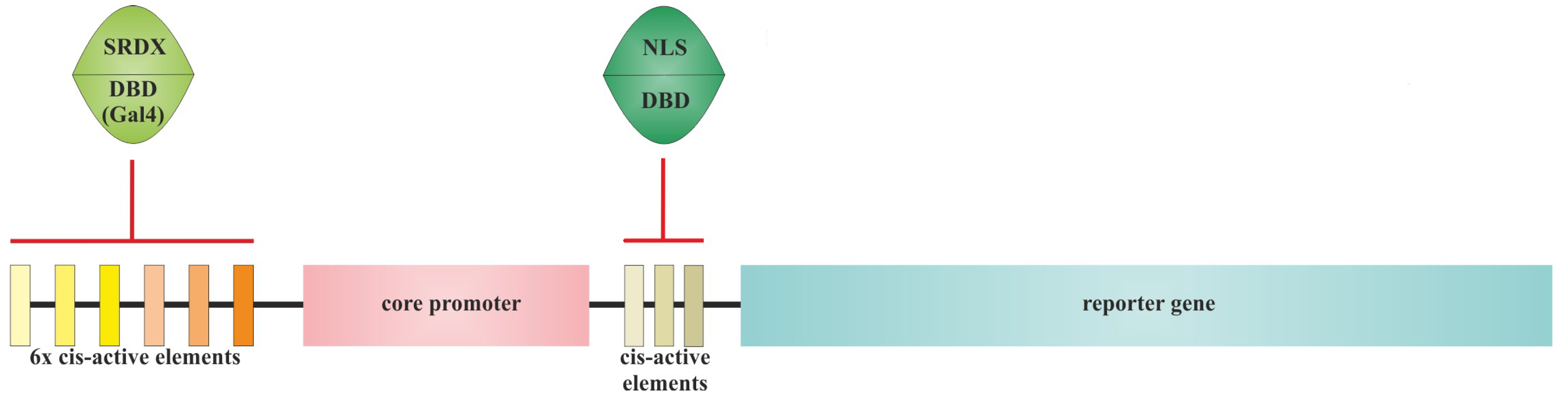

3.2. Cis-Elements Juggling and Domain Swapping

4. Native and Synthetic Bidirectional Promoters

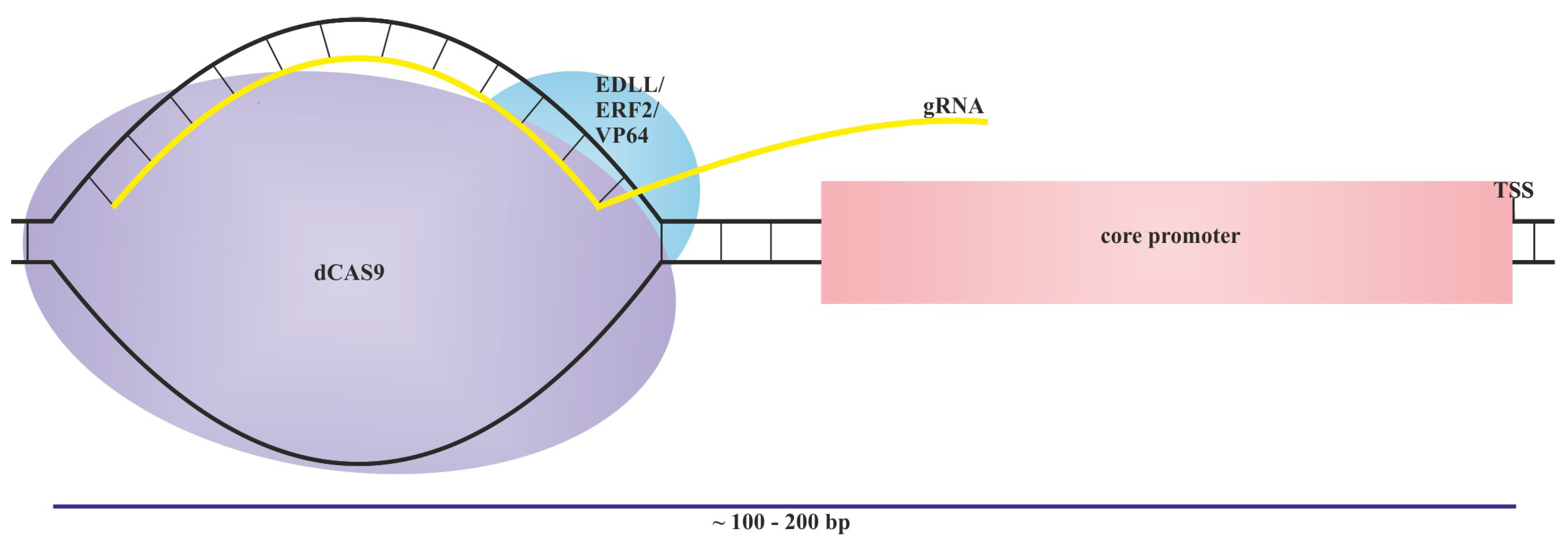

5. Orthogonal Expression Systems

6. Machine Learning and Deep Learning Support to Synthetic Promoter Preparing

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Henry, R.J. Innovations in plant genetics adapting agriculture to climate change. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2020, 56, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.R.; Chen, C.W.; Huang, Y.W.; Lee, H.J. Cell-Penetrating Peptides for Use in Development of Transgenic Plants. Molecules, 2023, 28, 3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Jain, G.; Sushmita; Chandra, S.; Kalia, V.; Upadhyay, S.K.; Dubey, R.S.; Verma, P.C. Failure of metanol detoxification in pests confers broad spectrum insect resistance in PME overexpressing transgenic cotton. Plant Sci. 2023, 333, 111737. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Chen, Z.; Chen, H.; Wang, C.; Song, L.; Sun, Y.; Cai, Y.; Zhou, D.; Ouyang, L.; Zhu, C.; He, H.; Peng, X. Stacking Multiple Genes Improves Resistance to Chilo suppressalis, Magnaporthe oryzae, and Nilaparvata lugens in Transgenic Rice. Genes (Basel). 2023, 14, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrière, Y.; Degain, B.; Unnithan, G.C.; Tabashnik, B.E. Inheritance and fitness cost of laboratory-selected resistance to Vip3Aa in Helicoverpa zea (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J Econ Entomol. 2023, 116, 1804–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lithanatudom, P.; Chawansuntati, K.; Saenjum, C.; Chaowasku, T.; Rattanathammethee, K.; Wungsintaweekul, B.; Osathanunkul, M.; Wipasa, J. In-vitro antimalarial activity of metanolic leaf- and stem-derived extracts from four Annonaceae plants. BMC Res Notes. 2023, 16, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khayri, J.M.; Sudheer, W.N.; Banadka, A.; Lakshmaiah, V.V.; Nagella, P.; Al-Mssallem, M.Q.; Alessa, F.M.; Rezk, A.A. Biotechnological approaches for the production of gymnemic acid from Gymnema sylvestre R. Br. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 4459–4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamuli, R.; Nguyen, T.; Macdonald, J.R.; Pierens, G.K.; Fisher, G.M.; Andrews, K.T.; Adewoyin, F.B.; Omisore, N.O.; Odaibo, A.B.; Feng, Y. Isolation and In Vitro and In Vivo Activity of Secondary Metabolites from Clerodendrum polycephalum Baker against Plasmodium Malaria Parasites. J Nat Prod. 2023, 86, 2661–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Wen, Z.; Shen, T.; Cai, X.; Hou, Q.; Shang, C.; Qiao, G. Overexpression of PavbHLH28 from Prunus avium enhances tolerance to cold stress in transgenic Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, L.; Yu, X.; Zhao, J.; Tian, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, G.; Zhang, L.; Guo, X. Enhancing cold and drought tolerance in cotton: a protective role of SikCOR413PM1. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.Z.; Lum, A.; Schepers, E.; Liu, L.; Weston, R.T.; McGinness, B.S.; Heckert, M.J.; Xie, W.; Kassa, A.; Bruck, D.; Rauscher, G.; Kapka-Kitzman, D.; Mathis, J.P.; Zhao, J.Z.; Sethi, A.; Barry, J.; Lu, A.L.; Brugliera, F.; Lee, E.L.; van derWeerden, N.L.; Eswar, N.; Maher, M.J.; Anderson, M.A. Novel insecticidal proteins from ferns resemble insecticidal proteins from Bacillus thuringiensis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023, 120, e2306177120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, H.; Wen, Z.; Hootman, T.; Himes, J.; Duan, Q.; McMath, J.; Ditillo, J.; Sessler, R.; Conville, J.; Niu, Y.; Matthews, P.; Francischini, F.; Huang, F.; Bramlett, M. eCry1Gb.1Ig, A Novel Chimeric Cry Protein with High Efficacy against Multiple Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) Strains Resistant to Different GM Traits. Toxins (Basel). 2022, 14, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Ren, Z.; Xie, R.; Yin, C.; Ma, W.; Zhou, F.; Chen, H.; Lin, Y. Development of 'multiresistance rice' by an assembly of herbicide, insect and disease resistance genes with a transgene stacking system. Pest Manag Sci. 2021, 77, 1536–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Ng, E.; Lu, J.; Fenwick, T.; Tao, Y.; Bertain, S.; Sandoval, M.; Bermudez, E.; Hou, Z.; Patten, P.; Lassner, M.; Siehl, D. Desensitizing plant EPSP synthase to glyphosate: Optimized global sequence context accommodates a glycine-to-alanine change in the active site. J Biol Chem. 2019, 294, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.H.; Kim, J.K.; Jeong, Y.S.; You, M.K.; Lim, S.H.; Kim, J.K. Stepwise pathway engineering to the biosynthesis of zeaxanthin, astaxanthin and capsanthin in rice endosperm. Metab Eng. 2019, 52, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Zeng, D.; Yu, S.; Cui, C.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Chen, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, X.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y.G. From Golden Rice to aSTARice: Bioengineering Astaxanthin Biosynthesis in Rice Endosperm. Mol Plant. 2018, 11, 1440–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghissi, A.A.; Pei, S.; Liu, Y. Golden rice: scientific, regulatory and public information processes of a genetically modified organism. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2016, 36, 535–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, R.; Li, L. Golden Rice-Lessons learned for inspiring future metabolic engineering strategies and synthetic biology solutions. Methods Enzymol. 2022, 671, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyediran, I.; Rice, M.E.; Conville, J.; Boudreau, E.; Morsello, S.; Burd, T. Btcorn hybrids expressing mCry3A and eCry3.1Ab Proteins protect cornroots against western cornroot worm injury. Pest Manag Sci. 2023, 79, 4839–4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, L.; Fu, J.; Shen, W.; Fang, Z.; Dai, Y.; Jia, R.; Liu, B.; Liang, J. Fitness and Ecological Risk of Hybrid Progenies of Wild and Herbicide-Tolerant Soybeans With EPSPS Gene. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 922215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Liu, B.; Liu, L.; Fang, Z. Fitness of Insect-resistant transgenic rice T1C-19 under four growing conditions combining land use and weed competition. GM Crops Food. 2021, 12, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohnishi, Y.; Kawashima, T. Evidence of a novelsilencingeffect on transgenes in the Arabidopsisthaliana sperm cell. Plant Cell. 2023, 35, 3926–3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravanrouy, F.; Niazi, A.; Moghadam, A.; Taghavi, S.M. MAP30 transgenic tobacco lines: from silencing to inducing. Mol Biol Rep. 2021, 48, 6719–6728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrix, B.; Hoffer, P.; Sanders, R.; Schwartz, S.; Zheng, W.; Eads, B.; Taylor, D.; Deikman, J. Systemic GFP silencing is associated with high transgene expression in Nicotiana benthamiana. PLoS One. 2021, 16, e0245422–doi2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Wu, Y.; Shi, R.; Sun, M.; Li, Q.; Zhang, G.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W. Overexpression of wheat α-mannosidase gene TaMP impairs salt tolerance in transgenic Brachypodium distachyon. Plant Cell Rep. 2020, 39, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdeen, A.; Miki, B. The pleiotropic effects of the bar gene and glufosinate on the Arabidopsis transcriptome. Plant Biotechnol J. 2009, 7, 266–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, X.; Hu, B.; Pu, Z.; Wang, L.; Leustek, T.; Li, C. Co-overexpression of AtSAT1 and EcPAPR improves seed nutritional value in maize. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 969763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcher, M.S.; Vuu, K.M.; Zhou, A. Design of orthogonal regulatory systems for modulating gene expression in plants. Nat Chem Biol. 2020, 16, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brophy, J.A.N.; Magallon, K.J.; Duan, L.; Zhong, V.; Ramachandran, P.; Kniazev, K.; Dinneny, J.R. Synthetic genetic circuits as a means of reprogramming plant roots. Science. 2022, 377, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villao-Uzho, L.; Chávez-Navarrete, T.; Pacheco-Coello, R.; Sánchez-Timm, E.; Santos-Ordóñez, E. Plant Promoters: Their Identification, Characterization, and Role in Gene Regulation. Genes, 2023, 14, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strader, L.; Weijers, D.; Wagner, D. Plant transcription factors — being in the right place with the right company. Curr Op Plant Biol. 2022, 65, 102136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biłas, R.; Szafran, K.; Hnatuszko-Konka, K.; Kononowicz, A.K. Cis-regulatory elements used to control gene expression in plants. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2016, 127, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewska, M.; Wysokińska, H.; Kuźma, Ł.; Szymczyk, P. Eukaryotic and prokaryotic promoter databases as valuable tools in exploring the regulation of gene transcription: a comprehensive overview. Gene. 2018, 644, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Yang, S.; Fan, B.; Zhu, C.; Chen, Z. The Mediator Complex: A Central Coordinator of Plant Adaptive Responses to Environmental Stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Malley, R.C.; Huang, S.C.; Song, L.; Lewsey, M.G.; Bartlett, A.; Nery, J.R.; Galli, M.; Gallavotti, A.; Ecker, J.R. Cistrome and Epicistrome Features Shape the Regulatory DNA Landscape. Cell. 2016, 165, 1280–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyboulet, F.; Wydau-Dematteis, S.; Eychenne, T.; Alibert, O.; Neil, H.; Boschiero, C.; Nevers, M.C.; Volland, H.; Cornu, D.; Redeker, V.; Werner, M.; Soutourina, J. Mediator independently orchestrates multiple steps of preinitiation complex assembly in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 9214–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eychenne, T.; Novikova, E.; Barrault, M.B.; Alibert, O.; Boschiero, C.; Peixeiro, N.; Cornu, D.; Redeker, V.; Kuras, L.; Nicolas, P.; Werner, M.; Soutourina, J. Functional interplay between Mediator and TFIIB in preinitiation complex assembly in relation to promoter architecture. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 2119–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.Q.; Ranjan, A.; Liu, S.; Tang, X.; Ling, Y.; Wisniewski, J.; Mizuguchi, G.; Li, K.Y; Jou, V.; Zheng, Q.; Lavis, L.D.; Lionnet, T.; Wu, C. Spatiotemporal coordination of transcription preinitiation complex assembly in live cells. Mol Cell. 2021, 81, 3560–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Jin, R.; Yu, X.; Shen, M.; Wagner, J.D.; Pai, A.; Song, C.; Zhuang, M.; Klasfeld, S.; He, C.; Santos, A.M.; Helliwell, C.; Pruneda-Paz, J.L.; Kay, S.A.; Lin, X.; Cui, S.; Garcia, M.F.; Clarenz, O.; Goodrich, J.; Zhang, X.; Austin, R.S.; Bonasio, R.; Wagner, D. Cis and trans determinants of epigenetic silencing by Polycomb repressive complex 2 in Arabidopsis. Nat Genet. 2017, 49, 1546–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, K.; Von Koskull-Döring, P.; Bharti, S.; Kumar, P.; Tintschl-Körbitzer, A.; Treuter, E.; Nover, L. Tomato heat stress transcription factor HsfB1 represents a novel type of general transcription coactivator with a histone-like motif interacting with the plant CREB binding protein ortholog HAC1. Plant Cell. 2004, 16, 1521–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Pavangadkar, K.A.; Thomashow, M.F.; Triezenberg, S.J. Physical and functional interactions of Arabidopsis ADA2 transcriptional coactivator proteins with the acetyltransferase GCN5 and with the cold-induced transcription factor CBF1. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006, 1759, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Zhi, P.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Xu, J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, X.; Chang, C. Epigenetic Activation of Enoyl-CoA Reductase By An Acetyltransferase Complex Triggers Wheat Wax Biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2020, 183, 1250–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louphrasitthiphol, P.; Siddaway, R.; Loffreda, A.; Pogenberg, V.; Friedrichsen, H.; Schepsky, A.; Zeng, Z.; Lu, M.; Strub, T.; Freter, R. Tuning transcription factor availability through acetylation-mediated genomic redistribution. Mol. Cell. 2020, 79, 472–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, J.; Schmidt, F.; Schulz, M.H. Widespread effects of DNA methylation and intra-motif dependencies revealed by novel transcription factor binding models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, M.; Roosjen, M.; Crespo García, I.; van den Berg, W.; Malfois, M.; Boer, R.; Weijers, D.; Hohlbein, J. Cooperative action of separate interaction domains promotes high-affinity DNA binding of Arabidopsis thaliana ARF transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023, 120, e2219916120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, C.G.; Vaishnav, E.D.; Sadeh, R.; Abeyta, E.L.; Friedman, N.; Regev, A. Deciphering eukaryotic gene-regulatory logic with 100 million random promoters. Nat Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahein, A.; López-Malo, M.; Istomin, I.; Olson, E.J.; Cheng, S.; Maerkl, S.J. Systematic analysis of low-affinity transcription factor binding site clusters in vitro and in vivo establishes their functional relevance. Nat Commun. 2022, 13, 5273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sielemann, J.; Wulf, D.; Schmidt, R.; Bräutigam, A. Local DNA shape is a general principle of transcription factor binding specificity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 6549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zrimec, J.; Börlin, C.S.; Buric, F. Deep learning suggests that gene expression is encoded in all parts of a co-evolving interacting gene regulatory structure. Nat Commun. 2020; 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zrimec, J.; Zelezniak, A.; Gruden, K. Toward learning the principles of plant gene regulation. Trends Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 1206–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-González, A.; Caro, E. Effect of transcription terminator usage on the establishment of transgene transcriptional gene silencing. BMC Res Notes. 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Felippes, F.; McHale, M.; Doran, R.L.; Roden, S.; Eamens, A.L.; Finnegan, E.J.; Waterhouse, P.M. The key role of terminators on the expression and post-transcriptional gene silencing of transgenes. Plant J. 2020, 104, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Bansal, M. Variation of gene expression in plants is influenced by gene architecture and structural properties of promoters. PLoS One. 2019, 14, e0212678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurbidaeva, A.; Purugganan, M. Insulators in Plants: Progress and Open Questions. Genes (Basel). 2021, 12, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chico, J.M.; Lechner, E.; Fernandez-Barbero, G.; Canibano, E.; García-Casado, G.; Franco-Zorrilla, J.M.; Hammann, P.; Zamarreño, A.M.; García-Mina, J.M.; Rubio, V.; Genschik, P.; Solano, R. CUL3BPM E3 ubiquitin ligases regulate MYC2, MYC3, and MYC4 stability and JA responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020, 117, 6205–6215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Miao, M.; Kud, J.; Niu, X.; Ouyang, B.; Zhang, J.; Ye, Z.; Kuhl, J.C.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, F. SlNAC1, a stress-related transcription factor, is fine-tuned on both the transcriptional and the post-translational level. New Phytol. 2013, 197, 1214–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Liao, K.; Wang, L.N.; Shi, L.L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.J.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.F.; Chen, Y.Q.; Chen, Q.F.; Xiao, S. Calcium-dependent activation of CPK12 facilitates its cytoplasm-to-nucleus translocation to potentiate plant hypoxia sensing by phosphorylating ERF-VII transcription factors. Mol Plant. 2023, 16, 979–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Lin, R.; Tang, M.; Wang, L.; Fan, P.; Xia, X.; Yu, J.; Zhou, Y. SlMPK1- and SlMPK2-mediated SlBBX17 phosphorylation positively regulates CBF-dependent cold tolerance in tomato. New Phytol. 2023, 239, 1887–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.J.; Shan, W.; Liu, X.C.; Zhu, L.S.; Wei, W.; Yang, Y.Y.; Guo, Y.F.; Bouzayen, M.; Chen, J.Y.; Lu, W.J.; Kuang, J.F. Phosphorylation of transcription factor bZIP21 by MAP kinase MPK6-3 enhances banana fruit ripening. Plant Physiol. 2022, 188, 1665–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisner, N.; Maymon, T.; Sanchez, E.C.; Bar-Zvi, D.; Brodsky, S.; Finkelstein, R.; Bar-Zvi, D. Phosphorylation of Serine 114 of the transcription factor ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE 4 is essential for activity. Plant Sci. 2021, 305, 110847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantz, D.; Berg, J.M. Reduction in DNA-binding affinity of Cys2His2 zinc finger proteins by linker phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004, 101, 7589–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, A.J.C.; Matiolli, C.C.; Newman, D.W.; Vieira, J.G.P.; Duarte, G.T.; Martins, M.C.M.; Gilbault, E.; Hotta, C.T.; Caldana, C.; Vincentz, M. The sugar-responsive circadian clock regulator bZIP63 modulates plant growth. New Phytol. 2021, 231, 1875–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, A.; Matiolli, C.C.; Viana, A.J.C.; Hearn, T.J.; Kusakina, J.; Belbin, F.E. Circadian Entrainment in Arabidopsis by the Sugar-Responsive Transcription Factor bZIP63. Curr Biol. 2018, 28, 2597–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidhara, P.; Weiste, C.; Collani, S.; Krischke, M.; Kreisz, P.; Draken, J.; Feil, R.; Mair, A.; Teige, M.; Müller, M.J.; Schmid, M.; Becker, D.; Lunn, J.E.; Rolland, F.; Hanson, J.; Dröge-Laser, W. Perturbations in plant energy homeostasis prime lateral root initiation via SnRK1-bZIP63-ARF19 signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021, 118, e2106961118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Neuwald, A.F.; Hilakivi-Clarke, L.; Clarke, R.; Xuan, J. ChIP-GSM: Inferring active transcription factor modules to predict functional regulatory elements. PLoSComput. Biol. 2021, 17, e1009203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, P.; Su, Z. PCRMS: A database of predicted cis-regulatory modules and constituent transcription factor binding sites in genomes. Database 2022, 2022, baac024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoutzias, G.D.; Robertson, D.L.; Van de Peer, Y.; Oliver, S.G. Choose your partners: Dimerization in eukaryotic transcription factors. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2008, 33, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire-Rios, A.; Tanaka, K.; Crespo, I.; van der Wijk, E.; Sizentsova, Y.; Levitsky, V.; Lindhoud, S.; Fontana, M.; Hohlbein, J.; Boer, D.R.; et al. Architecture of DNA elements mediating ARF transcription factor binding and auxin-responsive gene expression in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 24557–24566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Zavaliev, R.; Wu, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Cheng, J.; Dillard, L.; Powers, J.; Withers, J.; Zhao, J.; Guan, Z.; Borgnia, M.J.; Bartesaghi, A.; Dong, X.; Zhou, P. Structural basis of NPR1 in activating plant immunity. Nature. 2022, 605, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Che, Z.; Xu, G.; Ming, Z. Crystal structure of transcription factor TGA7 from Arabidopsis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2022, 637, 637,322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Kang, N.Y.; Pandey, S.K.; Cho, C.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, J. Dimerization in LBD16 and LBD18 transcription factors is critical for lateral root formation. Plant Physiol. 2017, 174, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Gao, J.; Sun, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, C.; Sulis, D.B.; Wang, J.P.; Chiang, V.L.; Li, W. Dimerization of PtrMYB074 and PtrWRKY19 mediates transcriptional activation of PtrbHLH186 for secondary xylem development in Populus trichocarpa. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 918–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchette, M.; Bataille, A.R.; Chen, X.; Poitras, C.; Laganiere, J.; Lefebvre, C.; Deblois, G.; Giguere, V.; Ferretti, V. Genome-wide computational prediction of transcriptional regulatory modules reveals new insights into human gene expression. Genome Res. 2006, 16, 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leivar, P.; Antolín-Llovera, M.; Ferrero, S.; Closa, M.; Arró, M.; Ferrer, A.; Boronat, A.; Campos, N. Multilevel control of Arabidopsis 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase by protein phosphatase 2A. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 1494–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.P.; Rohwer, J.M.; Ghirardo, A.; Hammerbacher, A.; Ortiz-Alcaide, M.; Raguschke, B.; Schnitzler, J.P.; Gershenzon, J.; Phillips, M.A. Deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate synthase controls flux through the methylerythritol 4-phosphate pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant. Physiol. 2014, 165, 1488–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zboińska, M.; Romero, L.C.; Gotor, C.; Kabała, K. Regulation of V-ATPase by Jasmonic Acid: Possible Role of Persulfidation. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 13896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Guo, W.; Mo, B.; Pan, Q.; Lu, J.; Wang, Z.; Peng, X.; Zhang, Z. Mitogen-activated protein kinase 2 specifically regulates photorespiration in rice. Plant Physiol. 2023, 193, 1381–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Wei, D.; Lei, L.; Zheng, H.; Wallace, I.S.; Li, S.; Gu, Y. CALCIUM-DEPENDENT PROTEIN KINASE32 regulates cellulose biosynthesis through post-translational modification of cellulose synthase. New Phytol. 2023, 239, 2212–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, V.; Archibald, B.N.; Brophy, J.A.N. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional controls for tuning gene expression in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2023, 71, 102315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiansson, E.; Thorsen, M.; Tamás, M.J.; Nerman, O. Evolutionary forces act on promoter length: identification of enriched cis-regulatory elements. Mol Biol Evol. 2009, 26, 1299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.L.; Singer, D.S. Core promoters in transcription: old problem, new insights. Trends Biochem Sci. 2015, 40, 165–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, D.J.; Chambon, P. The SV40 early region TATA box is required for accurate in vitro initiation of transcription. Nature. 1981, 290, 310–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, C.; Grotewold, E. Genome wide analysis of Arabidopsis core promoters. BMC Genomics. 2005, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, A.; Mendieta, J.P.; Vollmers, C.; Schmitz, R.J. Simple and accurate transcriptional start site identification using Smar2C2 and examination of conserved promoter features. Plant J. 2022, 112, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jores, T.; Tonnies, J.; Wrightsman, T.; Buckler, E.S.; Cuperus, J.T.; Fields, S.; Queitsch, C. Synthetic promoter designs enabled by a comprehensive analysis of plant core promoters. Nat Plants. 2021, 7, 842–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loganantharaj, R. Discriminating TATA box from putative TATA boxes in plant genome. Int J Bioinform Res Appl, 2. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, C.P. An inspection of the domain between putative TATA box and translation start site in 79 plant genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987, 15, 6643–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savinkova, L.K.; Sharypova, E.B.; Kolchanov, N.A. On the Role of TATA Boxes and TATA-Binding Protein in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plants (Basel). 2023, 12, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amack, S.C.; Ferreira, S.S.; Antunes, M.S. Tuning the Transcriptional Activity of the CaMV 35S Promoter in Plants by Single-Nucleotide Changes in the TATA Box. ACS Synth Biol. 2023, 12, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Tsunoda, T; Obokata, J. Photosynthesis nuclear genes generally lack TATA-boxes: a tobacco photosystem I gene responds to light through an initiator. Plant J. 2002, 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achard, P.; Lagrange, T.; El-Zanaty, A.F.; Mache, R. Architecture and transcriptional activity of the initiator element of the TATA-less RPL21 gene. Plant J. 2003, 35, 743–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, K.; Ansari, S.A.; Srivastava, R.; Lodhi, N.; Chaturvedi, C.P.; Sawant, S.V.; Tuli, R. The TATA-box sequence in the basal promoter contributes to determining light-dependent gene expression in plants. Plant Physiol. 2006, 142, 364–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civán, P.; Svec, M. Genome-wide analysis of rice (Oryza sativa L. subsp. japonica) TATA box and Y Patch promoter elements. Genome. 2009, 52, 294–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.Y.; Yoshioka, Y.; Hyakumachi, M.; Obokata, J. Characteristics of core promoter types with respect to gene structure and expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. DNA Res. 2011, 18, 333–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahmuradov, I.A.; Gammerman, A.J.; Hancock, J.M.; Bramley, P.M.; Solovyev, V.V. PlantProm: a database of plant promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 114–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.Y.; Ichida, H.; Matsui, M.; Obokata, J.; Sakurai, T.; Satou, M.; Seki, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Abe, T. Identification of plant promoter constituents by analysis of local distribution of short sequences. BMC Genomics. 2007, 8, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, T.W.; Kadonaga, J.T. The downstream core promoter element, DPE, is conserved from Drosophila to humans and is recognized by TAFII60 of Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1997, 11, 3020–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.Y.; Ichida, H.; Abe, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Sugano, S.; Obokata, J. Differentiation of core promoter architecture between plants and mammals revealed by LDSS analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 6219–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R.; Rai, K.M.; Srivastava, M.; Kumar, V.; Pandey, B.; Singh, S.P.; Bag, S.K.; Singh, B.D.; Tuli, R.; Sawant, S.V. Distinct role of core promoter architecture in regulation of light-mediated responses in plant genes. Mol Plant. 2014, 7, 626–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.Y; Yoshioka, Y.; Hyakumachi, M.; Obokata, J. Characteristics of core promoter types with respect to gene structure and expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. DNA Res. 2011, 18, 333–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.Y.; Yoshitsugu, T.; Sakurai, T.; Seki, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Obokata, J. Heterogeneity of Arabidopsis core promoters revealed by high-density TSS analysis. Plant J. 2009, 60, 350–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, H.; Matsuo, M.; Satoh, S.; Hata, T.; Hachisu, R.; Nakamura, M.; Yamamoto, Y.Y.; Kimura, H.; Matsui, M.; Obokata, J. Cryptic promoter activation occurs by at least two different mechanisms in the Arabidopsis genome. Plant J. 2021, 108, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, E.J.Y.; Maranas, C.J.; Nemhauser, J.L. A comparative analysis of stably expressed genes across diverse angiosperms exposes flexibility in underlying promoter architecture. G3 (Bethesda). 2023, 13, jkad206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, S.; Ware, D. Genome-wide computational prediction and analysis of core promoter elements across plant monocots and dicots. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e79011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves-Sanjuan, A.; Gnesutta, N.; Gobbini, A.; Martignago, D.; Bernardini, A.; Fornara, F.; Mantovani, R.; Nardini, M. Structural determinants for NF-Y subunit organization and NF-Y/DNA association in plants. Plant J. 2021, 105, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laloum, T.; De Mita, S.; Gamas, P.; Baudin, M.; Niebel, A. CCAAT-box binding transcription factors in plants: Y so many? Trends Plant Sci. 2013, 18, 157–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvenzani, V.; Testoni, B.; Gusmaroli, G.; Lorenzo, M.; Gnesutta, N.; Petroni, K.; Mantovani, R.; Tonelli, C. Interactions and CCAAT-binding of Arabidopsis thaliana NF-Y subunits. PLoS One. 2012, 7, e42902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Wei, W.; Tao, J.J.; Lu, X.; Bian, X.H.; Hu, Y.; Cheng, T.; Yin, C.C.; Zhang, W.K.; Chen, S.Y.; Zhang, J.S. Nuclear factor Y subunit GmNFYA competes with GmHDA13 for interaction with GmFVE to positively regulate salt tolerance in soybean. Plant Biotechnol J. 2021, 19, 2362–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.P.; Lin, J.J.; Li, W.H. Positional distribution of transcription factor binding sites in Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 25164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mironova, V.V.; Omelyanchuk, N.A.; Wiebe, D.S.; Levitsky, V.G. Computational analysis of auxin responsive elements in the Arabidopsis thaliana L. genome. BMC Genomics. 2014, 15, S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solovyev,V.V.; Shahmuradov, I.A.; and Salamov, A.A. Identification of promoter regions and regulatory sites. In: Computational Biology of Transcription Factor Binding (Methods in Molecular Biology); Ladunga, I. (ed). Springer Science+Business Media, Humana Press, New York City, USA, 2010, vol. 674, pp. 57-83.

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Guan, S.; Wang, F.; Tang, J.; Zhang, R.; Xie, L.; Lu, Y. Characterization of the cis elements in the proximal promoter regions of the anthocyanin pathway genes reveals a common regulatory logic that governs pathway regulation. J Exp Bot. 2015, 66, 3775–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, W.; Xu, D.; Li, J.; Luo, X.; Li, L.; Bian, Y.; Li, F.; Hao, Y.; He, Z.; Xia, X.; Song, X.; Cao, S. Efficient proteome-wide identification of transcription factors targeting Glu-1: A case study for functional validation of TaB3-2A1 in wheat. Plant Biotechnol J. 2023, 21, 1952–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksouri, N.; Castro-Mondragón, J.A.; Montardit-Tarda, F.; van Helden, J.; Contreras-Moreira, B.; Gogorcena, Y. Tuning promoter boundaries improves regulatory motif discovery in nonmodel plants: the peach example. Plant Physiol. 2021, 185, 1242–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keilwagen, J.; Grau, J.; Paponov, I.A.; Posch, S.; Strickert, M.; Grosse, I. De-novo discovery of differentially abundant transcription factor binding sites including their positional preference. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011, 7, e1001070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.Y.; Guo, X.J.; Chen, Z.X.; Chen, W.Y.; Wang, J.R. Identification and positional distribution analysis of transcription factor binding sites for genes from the wheat fl-cDNA sequences. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2017, 81, 1125–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, L.; Pelletier, J.M.; Hsu, S.W.; Baden, R.; Goldberg, R.B.; Harada, J.J. Combinatorial interactions of the LEC1 transcription factor specify diverse developmental programs during soybean seed development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020, 117, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Xie, L.; Tian, X.; Liu, S.; Xu, D.; Jin, H.; Song, J.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, D.; Li, G.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, X.; He, Z.; Cao, S. TaNAC100 acts as an integrator of seed protein and starch synthesis exerting pleiotropic effects on agronomic traits in wheat. Plant J. 2021, 108, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, K.; Do, A.; Senay-Aras, B.; Perales, M.; Alber, M.; Chen, W.; Reddy, G.V. Concentration-dependent transcriptional switching through a collective action of cis-elements. Sci Adv. 2022, 8, eabo6157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerji, J.; Rusconi, S.; Schaffner, W. Expression of a beta-globin gene is enhanced by remote SV40 DNA sequences. Cell. 1981, 27, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, J.C.; Agarwal, V.; Inoue, F. A systematic evaluation of the design and context dependencies of massively parallel reporter assays. Nat Methods, 2020, 17, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, B.; Zicola, J.; Oka, R.; Stam, M. Plant Enhancers: A Call for Discovery. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 974–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field Adelman, K. Evaluating Enhancer Function and Transcription. Annu Rev Biochem. 2020, 89, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louwers, M.; Bader, R.; Haring, M.; van Driel, R.; de Laat, W.; Stam, M. Tissue- and expression level-specific chromatin looping at maize b1 epialleles. Plant Cell. 2009, 21, 832–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; McMullen, M.D.; Bauer, E.; Schön, C.C.; Gierl, A.; Frey, M. Prolonged expression of the BX1 signature enzyme is associated with a recombination hotspot in the benzoxazinoid gene cluster in Zea mays. J Exp Bot. 2015, 66, 3917–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, F.; Boutry, M.; Hsu, M.Y.; Wong, M.; Chua, N.H. The 5'-proximal region of the wheat Cab-1 gene contains a 268-bp enhancer-like sequence for phytochrome response. EMBO J. 1987, 6, 2537–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, Y.L.; Watson, L.A.; Gray, J.C. The transcriptional enhancer of the pea plastocyanin gene associates with the nuclear matrix and regulates gene expression through histone acetylation. Plant Cell. 2003, 15, 1468–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jores, T.; Tonnies, J.; Dorrity, M.W.; Cuperus, J.T.; Fields, S.; Queitsch, C. Identification of Plant Enhancers and Their Constituent Elements by STARR-seq in Tobacco Leaves. Plant Cell. 2020, 32, 2120–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabidi, M.A.; Arnold, C.D.; Schernhuber, K. Enhancer–core-promoter specificity separates developmental and housekeeping gene regulation. Nature. 2015, 518, 556–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwafuchi-Doi, M.; Zaret, K.S. Pioneer transcription factors in cell reprogramming. Genes Dev. 2014, 28, 2679–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.; Klasfeld, S.; Zhu, Y.; Fernandez Garcia, M.; Xiao, J.; Han, S.K.; Konkol, A.; Wagner, D. LEAFY is a pioneer transcription factor and licenses cell reprogramming to floral fate. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, X.; Blanc-Mathieu, R.; GrandVuillemin, L.; Huang, Y.; Stigliani, A.; Lucas, J.; Thévenon, E.; Loue-Manifel, J.; Turchi, L.; Daher, H.; Brun-Hernandez, E.; Vachon, G.; Latrasse, D.; Benhamed, M.; Dumas, R.; Zubieta, C.; Parcy, F. The LEAFY floral regulator displays pioneer transcription factor properties. Mol Plant. 2021, 14, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, J.; Abe, N.; Rinaldi, L.; McGregor, A.P.; Frankel, N.; Wang, S.; Alsawadi, A.; Valenti, P.; Plaza, S.; Payre, F.; Mann, R.S.; Stern, D.L. Low affinity binding site clusters confer hox specificity and regulatory robustness. Cell. 2015, 160, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.I.; Barolo, S. Low-affinity transcription factor binding sites shape morphogen responses and enhancer evolution. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013, 368, 20130018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Corral, R.; Park, M.; Biette, K.M.; Friedrich, D.; Scholes, C.; Khalil, A.S.; Gunawardena, J.; DePace, A.H. Transcriptional kinetic synergy: A complex landscape revealed by integrating modeling and synthetic biology. Cell Syst. 2023, 14, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, G.D.; Ching, W.H.; Cornejo-Páramo, P.; Wong, E.S. Decoding enhancer complexity with machine learning and high-throughput discovery. Genome Biol. 2023, 24, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramasamy, S.; Aljahani, A.; Karpinska, M.A.; Cao, T.B.N.; Velychko, T.; Cruz, J.N.; Lidschreiber, M.; Oudelaar, A.M. The Mediator complex regulates enhancer-promoter interactions. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2023, 30, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wei, L.; Chen, S.S.; Cai, X.W.; Su, Y.N.; Li, L.; Chen, S.; He, X.J. The CBP/p300 histone acetyltransferases function as plant-specific MEDIATOR subunits in Arabidopsis. J Integr Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 755–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Yang, R.; Chen, H. The Arabidopsis thaliana Mediator subunit MED8 regulates plant immunity to Botrytis Cinerea through interacting with the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor FAMA. PLoS One. 2018, 13, e0193458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Jiang, H.; Li, L.; Zhai, Q.; Qi, L.; Zhou, W.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Zheng, W.; Sun, J.; Li, C. The Arabidopsis mediator subunit MED25 differentially regulates jasmonate and abscisic acid signaling through interacting with the MYC2 and ABI5 transcription factors. Plant Cell. 2012, 24, 2898–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.P.; Tang, Z.; Chen, C.W.; Shimada, M.; Koche, R.P.; Wang, L.H.; Nakadai, T.; Chramiec, A.; Krivtsov, A.V.; Armstrong, S.A.; Roeder, R.G. A UTX-MLL4-p300 Transcriptional Regulatory Network Coordinately Shapes Active Enhancer Landscapes for Eliciting Transcription. Mol Cell. 2017, 67, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haring, M.; Bader, R.; Louwers, M.; Schwabe, A.; van Driel, R.; Stam, M. The role of DNA methylation, nucleosome occupancy and histone modifications in paramutation. Plant J. 2010, 63, 366–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Chen, D.; Schumacher, J. Dynamic control of enhancer activity drives stage-specific gene expression during flower morphogenesis. Nat Commun. 2019, 10, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creyghton, M.P.; Cheng, A.W.; Welstead, G.G.; Kooistra, T.; Carey, B.W.; Steine, E.J.; Hanna, J.; Lodato, M.A.; Frampton, G.M.; Sharp, P.A.; Boyer, L.A.; Young, R.A.; Jaenisch, R. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010, 107, 21931–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Kim, Y.W.; Kang, J.; Kim, A. Histone H3K4me1 and H3K27ac play roles in nucleosome eviction and eRNA transcription, respectively, at enhancers. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e21781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, M.; Huang, M. Dynamic enhancer transcription associates with reprogramming of immune genes during pattern triggered immunity in Arabidopsis. BMC Biol. 2022, 20, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Ruscio, A.; Ebralidze, A.K.; Benoukraf, T.; Amabile, G.; Goff, L.A.; Terragni, J.; Figueroa, M.E.; De Figueiredo Pontes, L.L.; Alberich-Jorda, M.; Zhang, P.; Wu, M. ; D'Alò, F; Melnick, A. ; Leone, G.; Ebralidze, K.K.; Pradhan, S.; Rinn, J.L.; Tenen, D.G. DNMT1-interacting RNAs block gene-specific DNA methylation. Nature. 2013, 503, 371–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran, M.; Yates, C.M.; Skalska, L.; Dawson, M.; Reis, F.P.; Viiri, K.; Fisher, C.L.; Sibley, C.R.; Foster, B.M.; Bartke, T.; Ule, J.; Jenner, R.G. The interaction of PRC2 with RNA or chromatin is mutually antagonistic. Genome Res. 2016, 26, 896–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorito, E.; Sharma, Y.; Gilfillan, S.; Wang, S.; Singh, S.K.; Satheesh, S.V.; Katika, M.R.; Urbanucci, A.; Thiede, B.; Mills, I.G.; Hurtado, A. CTCF modulates Estrogen Receptor function through specific chromatin and nuclear matrix interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 10588–10602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray-Jones, H.; Spivakov, M. Transcriptional enhancers and their communication with gene promoters. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021, 78, 6453–6485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uyehara, C.M.; Apostolou, E. 3D enhancer-promoter interactions and multi-connected hubs: Organizational principles and functional roles. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, Q.; Chilton, M.D.; de Fontes, C.M.; He, C.; Nuccio, M.; Zhu, T.; Wu, Y.; Chen, J.S.; Shi, L. Trait stacking in transgenic crops: challenges and opportunities. GM Crops. 2010, 1, 220–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehryar, K.; Khan, R.S.; Iqbal, A.; Hussain, S.A.; Imdad, S.; Bibi, A.; Hamayun, L.; Nakamura, I. Transgene Stacking as Effective Tool for Enhanced Disease Resistance in Plants. Mol Biotechnol. 2020, 62, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, R.; Thomson, J.G.; Thilmony, R. A versatile and robust Agrobacterium-based gene stacking system generates high-quality transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Plant J. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Krichevsky, A.; Zaltsman, A.; King, L.; Citovsky, V. Expression of complete metabolic pathways in transgenic plants. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev. 2012, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peremarti, A.; Twyman, R. M.; Gómez-Galera, S.; Naqvi, S.; Farré, G.; Sabalza, M.; et al. Promoter diversity in multigene transformation. Plant Mol. Biol. 2010, 73, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P. H.; Prather, K. J.; Prazeres, D. M. F.; Monteiro, G. A. Analysis of DNA repeats in bacterial plasmids reveals the potential for recurrent instability events. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 87, 2157–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mall, T.; Gupta, M.; Dhadialla, T.S.; Rodrigo, S. Overview of Biotechnology-Derived Herbicide Tolerance and Insect Resistance Traits in Plant Agriculture. Methods Mol Biol. 2019, 1864, 313–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Yu, S.; Zeng, D.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Xie, X.; Shen, R.; Tan, J.; Li, H.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Guo, J.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y.G. Development of "Purple Endosperm Rice" by Engineering Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in the Endosperm with a High-Efficiency Transgene Stacking System. Mol Plant. 2017, 10, 918–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Liu, Y.G. TransGene Stacking II Vector System for Plant Metabolic Engineering and Synthetic Biology. Methods Mol Biol. 2021, 2238, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.J.; Kim, B.R.; Kim, S.U. Metabolic flux analysis of diterpene biosynthesis pathway in rice. Biotechnol Lett. 2005, 27, 1375–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.J.; Chung, M.Y.; Lee, H.A.; Lee, S.B.; Grandillo, S.; Giovannoni, J.J.; Lee, J.M. Natural overexpression of CAROTENOID CLEAVAGE DIOXYGENASE 4 in tomato alters carotenoid flux. Plant Physiol. 2023, 192, 1289–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manickavasagam, M.; Ganapathi, A.; Anbazhagan, V.R.; Sudhakar, B.; Selvaraj, N. Vasudevan, A.; Kasthurirengan, S. Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation and development of herbicide-resistant sugarcane (Saccharum species hybrids) using axillary buds. Plant Cell Rep. 2004, 23, 134–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Zhu, L.; Wu, G. Development of a general method for detection and quantification of the P35S promoter based on assessment of existing methods. Sci Rep. 2014, 4, 7358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betts, S.D.; Basu, S.; Bolar, J.; Booth, R.; Chang, S.; Cigan, A.M.; Farrell, J.; Gao, H.; Harkins, K.; Kinney, A.; Lenderts, B.; Li, Z.; Liu, L.; McEnany, M.; Mutti, J.; Peterson, D.; Sander, J.D.; Scelonge, C.; Sopko, X.; Stucker, D.; Wu, E.; Chilcoat, N.D. Uniform Expression and Relatively Small Position Effects Characterize Sister Transformants in Maize and Soybean. Front Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohn, A.F.; Trtikova, M.; Chapela, I.; Van den Berg, J.; du Plessis, H.; Hilbeck, A. Transgene behavior in Zea mays L. crosses across different genetic backgrounds: Segregation patterns, cry1Ab transgene expression, insecticidal protein concentration and bioactivity against insect pests. PLoS One. 2020, 15, e0238523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.; Zhu, Q.; Wei, Z.; Owens, L.A.; Fish, T.; Kim, H.; Thannhauser, T.W.; Cahoon, E.B.; Li, L. Multi-strategy engineering greatly enhances provitamin A carotenoid accumulation and stability in Arabidopsis seeds. aBIOTECH. 2021, 2, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpin, C. Gene stacking in transgenic plants--the challenge for 21st century plant biotechnology. Plant Biotechnol J. 2005 Mar;3(2):141-55. [CrossRef]

- Spatola Rossi, T.; Fricker, M.; Kriechbaumer, V. Gene Stacking and Stoichiometric Expression of ER-Targeted Constructs Using "2A" Self-Cleaving Peptides. Methods Mol Biol, 2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.M.; Frankman, E.L.; Tzfira, T. A versatile vector system for multiple gene expression in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2005, 10, 357–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, T.; Kurose, T.; Hino, T.; Tanaka, K.; Kawamukai, M.; Niwa, Y.; Toyooka, K.; Matsuoka, K.; Jinbo, T.; Kimura, T. Development of series of gateway binary vectors, pGWBs, for realizing efficient construction of fusion genes for plant transformation. J Biosci Bioeng. 2007, 104, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Teng, C.; Wei, H.; Liu, S.; Xuan, H.; Peng, W.; Li, Q.; Hao, H.; Lyu, Q.; Lyu, S.; Fan, Y. Development of a set of novel binary expression vectors for plant gene function analysis and genetic transformation. Front Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1104905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; AlAbed, D.; Whitteck, J.T.; Chen, W.; Bennett, S.; Asberry, A.; Wang, X.; DeSloover, D.; Rangasamy, M.; Wright, T.R.; Gupta, M. A combinatorial bidirectional and bicistronic approach for coordinated multi-gene expression in corn. Plant Mol Biol. 2015, 87, 341–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Hasi, A.; Wang, Z. Structural and Functional Analysis of a Bidirectional Promoter from Gossypium hirsutum in Arabidopsis. Int J Mol Sci. 2018, 19, 3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaiz, A.; Martinez, M.; Gonzalez-Melendi, P.; Grbic, V.; Diaz, I.; Santamaria, M.E. Plant Defenses Against Pests Driven by a Bidirectional Promoter. Front Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ma, X.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Yang, W.; Nugroho, R.D.; Luo, L.; Zhou, X.; Tang, C.; Fan, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, J.; Chen, R. Metabolic engineering of astaxanthin-rich maize and its use in the production of biofortified eggs. Plant Biotechnol J. 2021, 19, 1812–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogl, T.; Kickenweiz, T.; Pitzer, J.; Sturmberger, L.; Weninger, A.; Biggs, B.W.; Köhler, E.M.; Baumschlager, A.; Fischer, J.E.; Hyden, P.; Wagner, M.; Baumann, M.; Borth, N.; Geier, M.; Ajikumar, P.K.; Glieder, A. Engineered bidirectional promoters enable rapid multi-gene co-expression optimization. Nat Commun. 2018, 9, 3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laxa, M.; Fromm, S. Co-expression and regulation of photo respiratory genes in Arabidopsis thaliana: A bioinformatic approach. Curr. Plant Biol. 2018, 14, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Dey, N.; Maiti., I.B. Analysis of cis-sequence of subgenomic transcript promoter from the Figwort mosaic virus and comparison of promoter activity with the cauliflower mosaic virus promoters in monocot and dicot cells. Virus Res. 2002, 90, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakei, Y.; Masuda, H.; Nishizawa, N.K.; Hattori, H.; Aung, M.S. Elucidation of Novel cis-Regulatory Elements and Promoter Structures Involved in Iron Excess Response Mechanisms in Rice Using a Bioinformatics Approach. Front Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 660303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherpa, T.; Jha, D.K.; Kumari, K.; Chanwala, J.; Dey, N. Synthetic sub-genomic transcript promoter from Horseradish Latent Virus (HRLV). Planta. 2023, 257, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, S.; Sengupta, S.; Patro, S.; Purohit, S.; Samal, S.K.; Maiti, I.B.; Dey, N. Development of an intra-molecularly shuffled efficient chimeric plant promoter from plant infecting Mirabilis mosaic virus promoter sequence. J Biotechnol. 2014, 169, 103–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koschmann, J.; Machens, F.; Becker, M.; Niemeyer, J.; Schulze, J.; Bülow, L.; Stahl, D.J.; Hehl, R. Integration of bioinformatics and synthetic promoters leads to the discovery of novel elicitor-responsive cis-regulatory sequences in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2012, 160, 178–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jameel, A.; Noman, M.; Liu, W.; Ahmad, N.; Wang, F.; Li, X.; Li, H. Tinkering Cis Motifs Jigsaw Puzzle Led to Root-Specific Drought-Inducible Novel Synthetic Promoters. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameel, A.; Ketehouli, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Li, X.; Li, H. Detection and validation of cis-regulatory motifs in osmotic stress-inducible synthetic gene switches via computational and experimental approaches. Funct Plant Biol. 2022, 49, 1043–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.M.; Kallam, K.; Tidd, H.; Gendarini, G.; Salzman, A.; Patron, N.J. Rational design of minimal synthetic promoters for plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 11845–11856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, C.N.; Lee, T.Y.; Hung, Y.C.; Li, G.Z.; Tseng, K.C.; Liu, Y.H.; Kuo, P.L.; Zheng, H.Q.; Chang, W.C. PlantPAN3.0: a new and updated resource for reconstructing transcriptional regulatory networks from ChIP-seq experiments in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47(D1), D1155–D1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.M.; Park, S.H.; Park, S.Y.; Ma, S.H.; Do, J.H.; Kim, A.Y.; Jeon, M.J.; Shim, J.S.; Joung, Y.H. Identification of essential element determining fruit-specific transcriptional activity in the tomato HISTIDINE DECARBOXYLASE A gene promoter. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 1721–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, M.S.; Mazarei, M.; Millwood, R.J.; Liu, W.; Hewezi, T.; Stewart, C.N.Jr. Functional analysis of soybean cyst nematode-inducible synthetic promoters and their regulation by biotic and abiotic stimuli in transgenic soybean (Glycine max). Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shokouhifar, F.; Bahrabadi, M.; Bagheri, A.; Mamarabadi, M. Transient expression analysis of synthetic promoters containing F and D cis-acting elements in response to Ascochyta rabiei and two plant defense hormones. AMB Express. 2019, 9, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Z.; Myers, Z.A.; Petrella, D.; Engelhorn, J.; Hartwig, T.; Springer, N.M. Mapping responsive genomic elements to heat stress in a maize diversity panel. Genome Biol. 2022, 23, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, D.; South, P.F. Design and Analysis of Native Photorespiration Gene Motifs of Promoter Untranslated Region Combinations Under Short Term Abiotic Stress Conditions. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 828729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Guo, H.; Shen, S.; Yu, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhu, E.; Zhang, P.; Song, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K. Generation of the salicylic acid deficient Arabidopsis via a synthetic salicylic acid hydroxylase expression cassette. Plant Methods. 2022, 18, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Lv, S.; Hou, D.; Mo, C.; Wassie, M.; Yu, B.; Hu, T. A synthetic light-inducible photorespiratory bypass enhances photosynthesis to improve rice growth and grain yield. Plant Commun. 2023, 4, 100641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhullar, S.; Chakravarthy, S.; Advani, S.; Datta, S.; Pental, D.; Burma, P.K. Strategies for development of functionally equivalent promoters with minimum sequence homology for transgene expression in plants: cis-elements in a novel DNA context versus domain swapping. Plant Physiol. 2003, 132, 988–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, S.; Bordiya, Y.; Rodriguez, N.; Kim, J.; Gardner, E.C.; Gollihar, J.D.; Sung, S.; Ellington, A.D. Orthogonal control of gene expression in plants using synthetic promoters and CRISPR-based transcription factors. Plant Methods. 2022, 18, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danila, F.; Schreiber, T.; Ermakova, M.; Hua, L.; Vlad, D.; Lo, S.F.; Chen, Y.S.; Lambret-Frotte, J.; Hermanns, A.S.; Athmer, B.; von Caemmerer, S.; Yu, S.M.; Hibberd, J.M.; Tissier, A.; Furbank, R.T.; Kelly, S.; Langdale, J.A. A single promoter-TALE system for tissue-specific and tuneable expression of multiple genes in rice. Plant Biotechnol J. 2022, 20, 1786–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber, T.; Tissier, A. Generation of dTALEs and Libraries of Synthetic TALE-Activated Promoters for Engineering of Gene Regulatory Networks in Plants. Methods Mol Biol. 2017, 1629, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallam, K.; Moreno-Giménez, E.; Mateos-Fernández, R.; Tansley, C.; Gianoglio, S.; Orzaez, D.; Patron, N. Tunable control of insect pheromone biosynthesis in Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Biotechnol J. 2023, 21, 1440–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Perez, E.; Diego-Martin, B.; Quijano-Rubio, A.; Moreno-Giménez, E.; Selma, S.; Orzaez, D.; Vazquez-Vilar, M. A copper switch for inducing CRISPR/Cas9-based transcriptional activation tightly regulates gene expression in Nicotiana benthamiana. BMC Biotechnol. 2022, 22, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brückner, K.; Schäfer, P.; Weber, E.; Grützner, R.; Marillonnet, S.; Tissier, A. A library of synthetic transcription activator-like effector-activated promoters for coordinated orthogonal gene expression in plants. Plant J. 2015, 82, 707–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.E.; Neumann, M.; Duro, D.I.; Schmid, M. CRISPR-based tools for targeted transcriptional and epigenetic regulation in plants. PLoS One. 2019 Sep 26;14(9):e0222778. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Giménez, E.; Selma, S.; Calvache, C.; Orzáez, D. GB_SynP: A Modular dCas9-Regulated Synthetic Promoter Collection for Fine-Tuned Recombinant Gene Expression in Plants. ACS Synth Biol. 2022, 11, 3037–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, H.; Gould, D. PCR Assembly of Synthetic Promoters. Methods Mol Biol, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.; Chernajovsky, Y.; Gould, D. Assembly PCR synthesis of optimally designed, compact, multi-responsive promoters suited to gene therapy application. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 29388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Moreno, J.P.; Yaschenko, A.E.; Neubauer, M.; Marchi, A.J.; Zhao, C.; Ascencio-Ibanez, J.T.; Alonso, J.M.; Stepanova, A.N. A rapid and scalable approach to build synthetic repetitive hormone-responsive promoters. Plant Biotechnol J. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, H.; Du, J.; Hu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yang, N.; Mei, M.; Xiong, Z.; Tang, K.; Yi, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, S. Determination of Nucleotide Sequences within Promoter Regions Affecting Promoter Compatibility between Zymomonas mobilis and Escherichia coli. ACS Synth Biol. 2022, 11, 2811–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, S.; Ranjan, R.; Pattanaik, S.; Maiti, I.B.; Dey, N. Efficient chimeric plant promoters derived from plant infecting viral promoter sequences. Planta, 2014, 239, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjan, R.; Dey, N. Development of vascular tissue and stress inducible hybrid-synthetic promoters through dof-1 motifs rearrangement. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2012, 63, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efremova, L.N.; Strelnikova, S.R.; Gazizova, G.R.; Minkina, E.A.; Komakhin, R.A. A Synthetic Strong and Constitutive Promoter Derived from the Stellaria media pro-SmAMP1 and pro-SmAMP2 Promoters for Effective Transgene Expression in Plants. Genes. 2020, 11, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Xie, C.; Song, B.; Ou, Y.; Lin, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J. Construction of efficient, tuber-specific, and cold-inducible promoters in potato. Plant Sci. 2015, 235, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; McHale, L.K.; Finer, J.J. Changes to the core and flanking sequences of G-box elements lead to increases and decreases in gene expression in both native and synthetic soybean promoters. Plant Biotechnol J. 2019, 17, 724–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Yuan, Z.; Wu, L.; Zhou, S.; Deng, Y. Precise Prediction of Promoter Strength Based on a De Novo Synthetic Promoter Library Coupled with Machine Learning. ACS Synth Biol. 2022, 11, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttanus, H.M.; Triola, E.H.; Velasquez-Guzman, J.C.; Shin, S.M.; Granja-Travez, R.S.; Singh, A.; Dale, T.; Jha, R.K. Targeted mutagenesis and high-throughput screening of diversified gene and promoter libraries for isolating gain-of-function mutations. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1202388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lee, J.H.; Poindexter, M.R.; Shao, Y.; Liu, W.; Lenaghan, S.C.; Ahkami, A.H.; Blumwald, E.; Stewart, C.N.Jr. Rational design and testing of abiotic stress-inducible synthetic promoters from poplar cis-regulatory elements. Plant Biotechnol J. 2021, 19, 1354–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Tagaloguin, P.; Chaffin, T.A.; Shao, Y.; Mazarei, M.; Millwood, R.J.; Stewart, C.N.Jr. Drought stress-inducible synthetic promoters designed for poplar are functional in rice. Plant Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shao, Y.; Chaffin, T.A.; Lee, J.H.; Poindexter, M.R.; Ahkami, A.H.; Blumwald, E.; Stewart, C.N.Jr. Performance of abiotic stress-inducible synthetic promoters in genetically engineered hybrid poplar (Populus tremula × Populus alba). Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1011939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, K.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Ye, X.; Xia, X.; He, Z.; Cao, S. Dissecting conserved cis-regulatory modules of Glu-1 promoters which confer the highly active endosperm-specific expression via stable wheat transformation. Crop J. 2019, 7, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waclawovsky, A.J.; Freitas, R.L.; Rocha, C.S.; Contim, L.A.; Fontes, E.P. Combinatorial regulation modules on GmSBP2 promoter: a distal cis-regulatory domain confines the SBP2 promoter activity to the vascular tissue in vegetative organs. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006, 1759, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, R.L.; Carvalho, C.M.; Fietto, L.G.; Loureiro, M.E.; Almeida, A.M.; Fontes, E.P. Distinct repressing modules on the distal region of the SBP2 promoter contribute to its vascular tissue-specific expression in different vegetative organs. Plant Mol Biol. 2007, 65, 603–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, A.; Kirkpatrick, L.D.; Ornelas, I.J.; Washington, L.J.; Hummel, N.F.C.; Gee, C.W.; Tang, S.N.; Barnum, C.R.; Scheller, H.V.; Shih, P.M. A Suite of Constitutive Promoters for Tuning Gene Expression in Plants. ACS Synth Biol. 2023, 12, 1533–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deb, D.; Dey, N. Synthetic Salicylic acid inducible recombinant promoter for translational research. J Biotechnol. 2019, 297, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepasi, M.; Iranbakhsh, A.; Saadatmand, S.; Ebadi, M.; Oraghi Ardebili, Z. Silicon nanoparticles (SiNPs) stimulated secondary metabolism and mitigated toxicity of salinity stress in basil (Ocimum basilicum) by modulating gene expression: a sustainable approach for crop protection. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2024, 31, 16485–16496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, H.N.; Joseph, K.S.; Paek, K.Y.; Park, S.Y. Production of specialized metabolites in plant cell and organo-cultures: the role of gamma radiation in eliciting secondary metabolism. Int J Radiat Biol. 2024, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, L.; Huang, W.; Yuan, M.; Zhou, F.; Li, X.; Lin, Y. Overexpression of OsSWEET5 in rice causes growth retardation and precocious senescence. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e94210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uy, A.L.T.; Yamamoto, A.; Matsuda, M.; Arae, T.; Hasunuma, T.; Demura, T.; Ohtani, M. The Carbon Flow Shifts from Primary to Secondary Metabolism during Xylem Vessel Cell Differentiation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2023, 64, 1563–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cun, Z.; Zhang, J.Y.; Hong, J.; Yang, J.; Gao, L.L.; Hao, B.; Chen, J.W. Integrated metabolome and transcriptome analysis reveals the regulatory mechanism of low nitrogen-driven biosynthesis of saponins and flavonoids in Panax notoginseng. Gene. 2024, 901, 148163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Ranjan, R. In silico characterization of synthetic promoters designed from mirabilis mosaic virus and rice tungro bacilliform virus. Virusdisease. 2020, 31, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, D.; Dey, N.; Leelavathi, S.; Ranjan, R. Development of efficient synthetic promoters derived from pararetrovirus suitable for translational research. Planta. 2021, 253, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patro, S.; Kumar, D.; Ranjan, R.; Maiti, I.B.; Dey, N. The development of efficient plant promoters for transgene expression employing plant virus promoters. Mol Plant. 2012, 5, 941–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khadanga, B.; Chanwala, J.; Sandeep, I.S.; Dey, N. Synthetic Promoters from Strawberry Vein Banding Virus (SVBV) and Dahlia Mosaic Virus (DaMV). Mol Biotechnol. 2021, 63, 792–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethi, L.; Deb, D.; Khadanga, B.; Dey, N. Synthetic promoters from blueberry red ringspot virus (BRRV). Planta. 2021, 253, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Duan, L.; Pruneda-Paz, J.L.; Oh, D.H.; Pound, M.; Kay, S.; Dinneny, J.R. The 6xABRE Synthetic Promoter Enables the Spatiotemporal Analysis of ABA-Mediated Transcriptional Regulation. Plant Physiol. 2018, 177, 1650–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persad, R.; Reuter, D.N.; Dice, L.T.; Nguyen, M.A.; Rigoulot, S.B.; Layton, J.S.; Schmid, M.J.; Poindexter, M.R.; Occhialini, A.; Stewart, C.N.Jr.; Lenaghan, S.C. The Q-System as a Synthetic Transcriptional Regulator in Plants. Front Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persad-Russell, R.; Mazarei, M.; Schimel, T.M.; Howe, L.; Schmid, M.J.; Kakeshpour, T.; Barnes, C.N.; Brabazon, H.; Seaberry, E.M.; Reuter, D.N.; Lenaghan, S.C.; Stewart, C.N.Jr. Specific Bacterial Pathogen Phytosensing Is Enabled by a Synthetic Promoter-Transcription Factor System in Potato. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 873480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, H.; Ling, F.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, Y.; Wang, R. Comprehensive construction strategy of bidirectional green tissue-specific synthetic promoters. Plant Biotechnol J. 2020, 18, 668–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In, S.; Lee, H.A.; Woo, J.; Park, E.; Choi, D. Molecular Characterization of a Pathogen-Inducible Bidirectional Promoter from Hot Pepper (Capsicum annuum). Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2020, 33, 1330–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ma, X.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Yang, W.; Nugroho, R.D.; Luo, L.; Zhou, X.; Tang, C.; Fan, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, J.; Chen, R. Metabolic engineering of astaxanthin-rich maize and its use in the production of biofortified eggs. Plant Biotechnol J. 2021, 19, 1812–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shantharaj, D.; Minsavage, G.V.; Orbović, V.; Moore, G.A.; Holmes, D.R.; Römer, P.; Horvath, D.M.; Lahaye, T.; Jones, J.B. A promoter trap in transgenic citrus mediates recognition of a broad spectrum of Xanthomonas citri pv. citri TALEs, including in planta-evolved derivatives. Plant Biotechnol J. 2023, 21, 2019–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Salmerón, V.; Schürholz, A.K.; Li, Z.; Schlamp, T.; Wenzl, C.; Lohmann, J.U.; Greb, T.; Wolf, S. Inducible, Cell Type-Specific Expression in Arabidopsis thaliana Through LhGR-Mediated Trans-Activation. J Vis Exp. 2019, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, B.M.; Lee, Y.S.; Wang, P.; Azodi, C.; Grotewold, E.; Shiu, S.H. Modeling temporal and hormonal regulation of plant transcriptional response to wounding. Plant Cell. 2022, 34, 867–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zrimec, J.; Fu, X.; Muhammad, A.S.; Skrekas, C.; Jauniskis, V.; Speicher, N.K.; Börlin, C.S.; Verendel, V.; Chehreghani, M.H.; Dubhashi, D.; Siewers, V.; David, F.; Nielsen, J.; Zelezniak, A. Controlling gene expression with deep generative design of regulatory DNA. Nat Commun. 2022, 13, 5099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Li, D.; Huang, R. EVMP: enhancing machine learning models for synthetic promoter strength prediction by Extended Vision Mutant Priority framework. Front Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1215609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.Y.; Zhao, B.G.; Shen, Z.; Mei, Y.C.; Li, G.; Dong, F.Q.; Zhang, J.; Chao, Q.; Wang, B.C. Integrating ATAC-seq and RNA-seq to identify differentially expressed genes with chromatin-accessible changes during photosynthetic establishment in Populus leaves. Plant Mol Biol. 2023, 113, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartor, R.C.; Noshay, J.; Springer, N.M.; Briggs, S.P. Identification of the expressome by machine learning on omics data. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019, 116, 18119–18125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Jiang, H.; Kong, L.; Chen, Y.; Lang, K.; Fan, X.; Zhang, L.; Pian, C. Deep6mA: A deep learning framework for exploring similar patterns in DNA N6-methyladenine sites across different species. PLoS Comput Biol. 2021, 17, e1008767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N'Diaye, A.; Byrns, B.; Cory, A.T.; Nilsen, K.T.; Walkowiak, S.; Sharpe, A.; Robinson, S.J.; Pozniak, C.J. Machine learning analyses of methylation profiles uncovers tissue-specific gene expression patterns in wheat. Plant Genome. 2020, 13, e20027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Shu, Y.; Meng, F.; Lu, Y.; Liu, B.; Bai, X.; Guo, D. Cis-regulatory element based gene finding: an application in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Inform. 2008, 21, 177–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mishra, H.; Singh, N.; Misra, K.; Lahiri, T. An ANN-GA model based promoter prediction in Arabidopsis thaliana using tilling microarray data. Bioinformation. 2011, 6, 240–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boer, C.G.; Taipale, J. Hold out the genome: a roadmap to solving the cis-regulatory code. Nature. 2024, 625, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washburn, J.D.; Mejia-Guerra, M.K.; Ramstein, G.; Kremling, K.A.; Valluru, R.; Buckler, E.S.; Wang, H. Evolutionarily informed deep learning methods for predicting relative transcript abundance from DNA sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019, 116, 5542–5549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasmeen, E.; Wang, J.; Riaz, M.; Zhang, L.; Zuo, K. Designing artificial synthetic promoters for accurate, smart, and versatile gene expression in plants. Plant Commun. 2023, 4, 100558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, E.G.; Elorriaga, E.; Liu, Y.; Duduit, J.R.; Yuan, G.; Tsai, C.J.; Tuskan, G.A.; Ranney, T.G.; Yang, X.; Liu, W. Plant Promoters and Terminators for High-Precision Bioengineering. Biodes Res. 2023, 5, 0013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazier, A.; Blazeck, J. Advances in promoter engineering: Novel applications and predefined transcriptional control. Biotechnol J. 2021, 16, e2100239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Kim, W.C. A Fruitful Decade Using Synthetic Promoters in the Improvement of Transgenic Plants. Front Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Stewart, C.N.Jr. Plant synthetic promoters and transcription factors. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2016, 37, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Kim, W.C. A Fruitful Decade Using Synthetic Promoters in the Improvement of Transgenic Plants. Front Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.J.Y.; Nemhauser, J.L. Building a pipeline to identify and engineer constitutive and repressible promoters. Quant Plant Biol. 2023, 4, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morey, K.J.; Antunes, M.S.; Albrecht, K.D.; Bowen, T.A.; Troupe, J.F.; Havens, K.L.; Medford, J.I. Developing a synthetic signal transduction system in plants. Methods Enzymol. 2011, 497, 581–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyashita, E.; Komatsu, K.R.; and Saito, H. Large-scale analysis of RNA-protein interactions for functional RNA motif discovery using FOREST. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2509, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rigoulot, S.B.; Schimel, T.M.; Lee, J.H.; Sears, R.G.; Brabazon, H.; Layton, J.S.; Li, L.; Meier, K.A.; Poindexter, M.R.; Schmid, M.J.; Seaberry, E.M.; Brabazon, J.W.; Madajian, J.A.; Finander, M.J.; DiBenedetto, J.; Occhialini, A.; Lenaghan, S.C.; Stewart, C.N.Jr. Imaging of multiple fluorescent proteins in canopies enables synthetic biology in plants. Plant Biotechnol J. 2021, 19, 830–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigoulot, S.B.; Barco, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Meier, K.A.; Moore, M.; Fabish, J.; Whinna, R.; Park, J.; Seaberry, E.M.; Gopalan, A.; Dong, S.; Chen, Z.; Que, Q. Automated, High-Throughput Protoplast Transfection for Gene Editing and Transgene Expression Studies. Methods Mol Biol. 2023, 2653, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigoulot, S.B.; Park, J.; Fabish, J.; Seaberry, E.M.; Parrish, A.; Meier, K.A.; Whinna, R.; Dong, S. Enabling High-throughput Transgene Expression Studies Using Automated Liquid Handling for Etiolated Maize Leaf Protoplasts. J Vis Exp. 2024, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczyk, P. Closely-Spaced Repetitions of CAMTA Trans-Factor Binding Sites in Promoters of Model Plant MEP Pathway Genes. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).