3.1. The Widths of Different CIRs

In the classical model of Giacalone et al.(2002) [

7] and Kocharov (2003)[

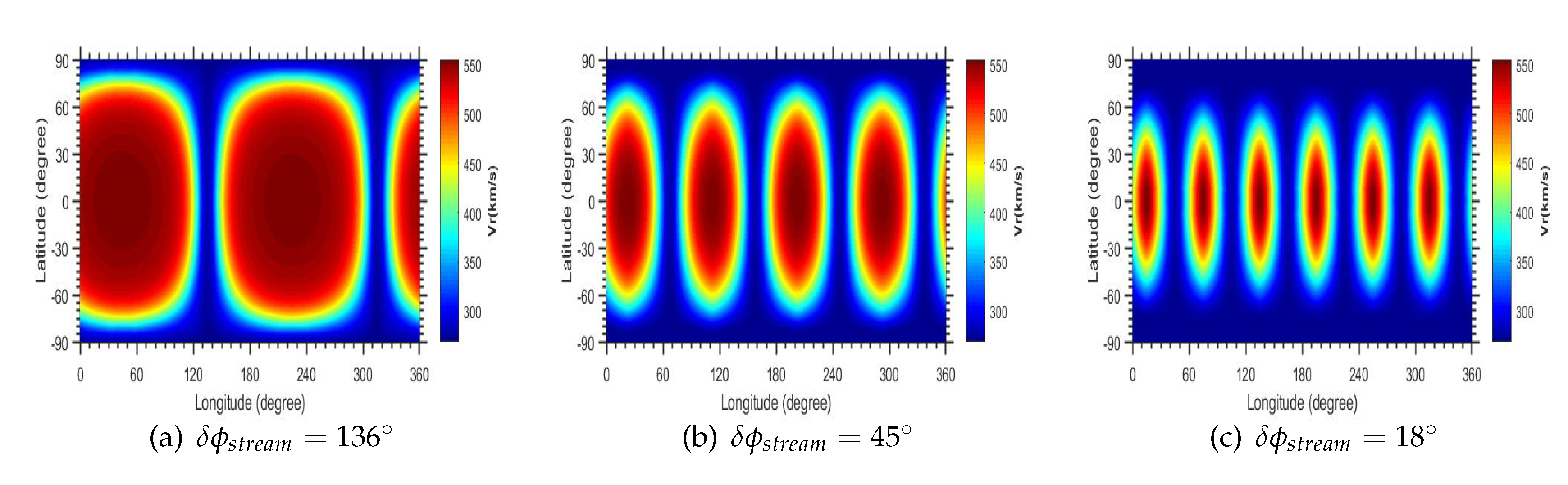

27], the compression width is derived from the azimuthal width

, which is one of the coefficients in the function of the radial flow speed assumed. In our model, the compression width

is calculated by fitting the radial solar wind speed profile perpendicular to the the stream interface (SI) at 1 AU using the function form of the flow speed in the model of [

27] (see Equation (

1) in [

27]).

In the observation, the thickness of the compression region along a given radius vector (

) is given by the product of the measured duration of the event and the mean of maximum and minimum solar wind speed across the compression region [

28,

29]. The compression region boundaries were selected where the pressure structure emerges from and decays back to the background. The width perpendicular to the stream interface (

) is more meaningful for the study of SIR evolution, which can be roughly estimated by the projected width (

) into the solar equatorial plane. The projected width (

) is approximately the product of duration, mean velocity, and

, where

is the spiral angle [

30]. In our model, the compression region boundaries are selected where the total perpendicular pressure

is

higher than the background. The radial extent

at 1 AU is calculated by

, where

W is a constant speed at which the compression moves radially outward in the inertial (not rotating) frame of reference,

is an azimuthal width of the compression region, and

is the Sun rotation rate.

W is calculated by the mean of maximum and minimum solar wind speed across the compression region in the solar equatorial plane at 1 AU. The azimuthal width

is calculated by the longitude difference between the compression region boundaries at 1 AU. The projected width (

) is then calculated by

. The spiral angle

is

, where

r is the heliocentric distance (1 AU). The width

is calculated by the distance between the compression region boundaries perpendicular to the stream interface (SI) at 1 AU.

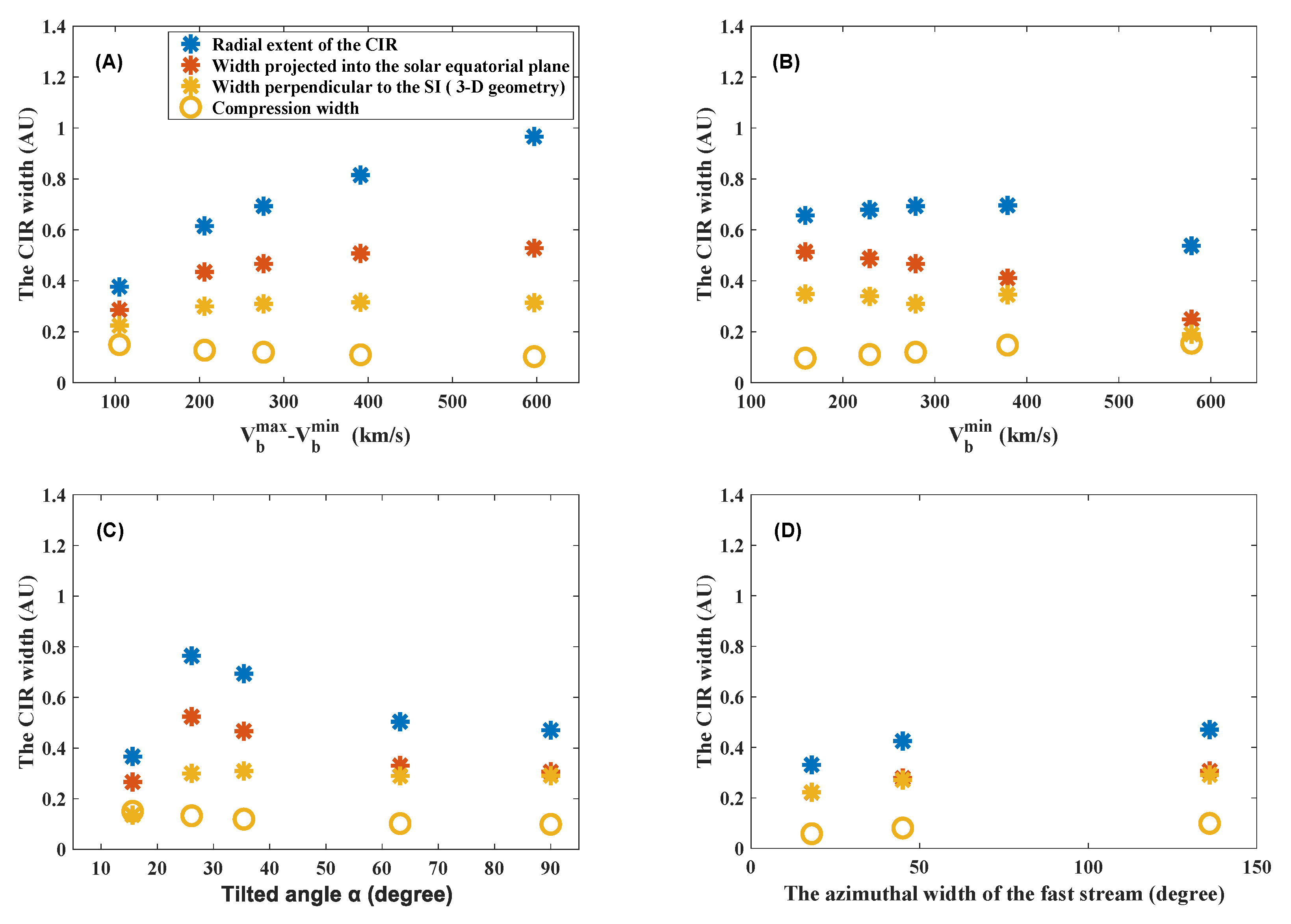

Figure 2 shows the CIR widths at 1AU. The yellow circles are the compression widths

derived from the solar wind profile. The blue asterisks are radial extents (

). The yellow asterisks are the CIR widths considering 3-D geometry (

). The red ones are the projected length into the equatorial plane (

).

As is shown in panel (A), for the cases in Set A, the compression width determined from the solar wind speed profile decreases as the solar wind speed difference increases. For the same slow solar wind speed, a larger fast wind speed implies a larger compression ratio, which corresponds to a smaller compression width. However, the widths determined from the pressure (i.e., , , and ) have a different trend from the compression width (). The increases as the solar wind speed difference increases. The compression region determined by the pressure expands to a greater width with a larger compression ratio. The radial extent () and the projected width () are more sensitive to the than the . As the varies from 105 to 597 , the varies from 0.22 AU to 0.31 AU, while the varies from 0.29 AU to 0.53 AU and varies from 0.38 AU to 0.97 AU. For the cases in Set B, the compression width () increases as the slow solar wind speed increases, since for the same solar wind speed difference, a larger slow wind speed implies a smaller compression ratio. Accordingly, the decreases as the slow solar wind speed increases. As the varies from 159 to 579 , the varies from 0.35 AU to 0.19 AU. Unlike Set A, the change in (0.12 AU) with is similar to (0.16 AU), while the change in (0.26 AU) is larger. For the cases in Set C, the compression width () decreases as the tilt angle increases. This is because, for a given fast and slow solar wind speed, the compression ratio perpendicular to the SI increases with the increasing tilt angle. As the tilt angle increases, on the one hand, increases and then remains almost constant, and on the other hand, the ratio of the projection on the equatorial plane to decreases. Thus and increase and then decrease, peaking at a tilt angle of about . The variation of , , and with the tilt angle is 0.17 AU, 0.25 AU, and 0.39 AU, respectively. The azimuthal width of the fast stream has little effect on the with of CIRs. and decrease slightly with the azimuthal width of the fast stream.

Our results indicate that different criteria lead to different CIR widths. The definitions and criteria should be paid attention to when discussing this quantity. The widths determined from the pressure (e.g., [

28,

29]) have different trends with the background parameters from the compression widths determined from the solar wind speed profile (e.g., [

27,

31]).

Jian (2008) [

30] found that, during 1979 – 1988, the SIR duration and width were smaller around solar minimum. The SIR width in their results correspond to

in our results. Around solar minimum, the solar wind speed difference is smaller [

30] and the tilted angle is smaller [

32]. The width

decreases as the solar wind difference decreases (Set A) and decreases when the tilt angle decreases from

(Set C). This can explain the observation. Jian (2019) [

21] reported that the SIRs are moderately wider in Solar Cycle 24 than in Solar Cycle 23. Although the mean solar wind speed difference is similar in this two Cycles, the mean minimum solar wind speed and the mean maximum solar wind speed are both slower in Cycle 24 than in Cycle 23. According to our results in Set B, the width

increases as the minimum solar wind speed

decreases when the solar wind speed difference

remains the same. Our results are consistent with the observations.

In the classic numerical models, the compression azimuthal widths of the CIRs (

) are independent with the other parameters [

7,

27]. Our model shows that the compression azimuthal widths (

in our results) are related to background parameters such as solar wind speed, tilt angle, and the azimuthal width of the fast stream.

3.2. Particle Acceleration in Various Compression Regions

This section explores the acceleration effect on particles in different compression regions and the impact of acceleration on particles with varying energy levels.

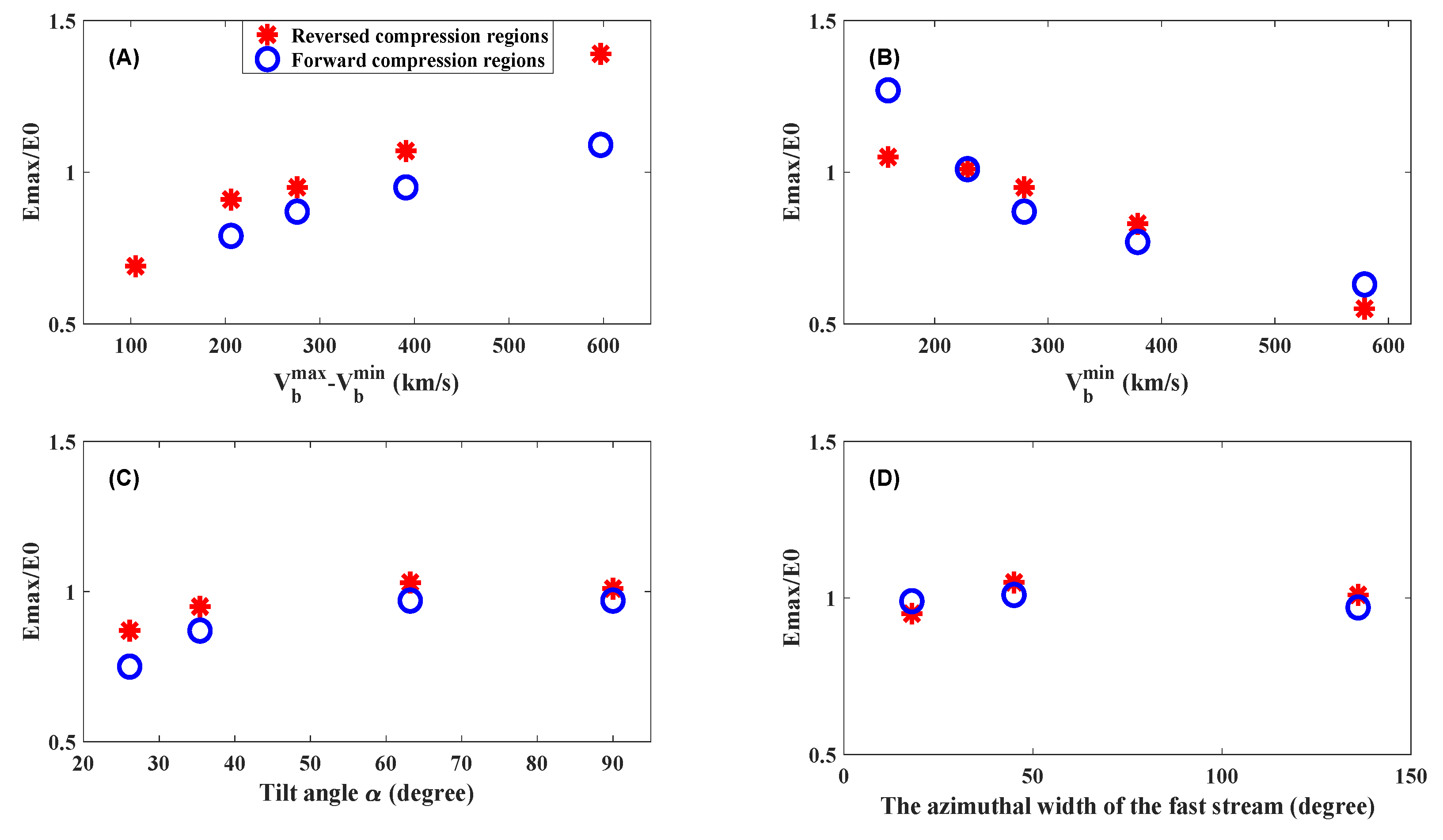

Figure 3 displays the ratio of the maximum energy to the original energy (

) at 1 AU after 60 hours versus the CIR parameters. The red and blue markers are for the reverse and the forward compression regions, respectively.

As is shown in panel (D), the acceleration effect is similar with different azimuthal widths of the fast streams. However, the acceleration effect is affected by the solar wind speed and tilt angle. As is shown in panel (A), the acceleration effect of both reverse and forward compression region increases as the solar wind speed difference increases. In the case with of 105 , the forward compression region is not formed. As the varies from 206 to 391 , the value of varies from 0.91 to 1.07 in the reverse compression regions and from 0.79 to 0.95 in the forward compression regions. The magnitude of change is similar in this range. However, the value of increases respectively by 0.32 and 0.14 in the reverse and forward compression region as varies from 391 to 597 . Panel (B) shows that the acceleration effect decreases as the slow solar wind speed increases. As the varies from 229 to 579 , the value of varies from 1.01 to 0.55 in the reverse compression regions and from 1.01 to 0.63 in the forward compression regions. In these cases, the value difference of the is less than 0.1 between the forward and reverse region. However, in the case with of 159 , the value of the in the forward compression region (1.27) is much larger than in the reverse compression region (1.05). The acceleration effect increases and then stays almost constant as the tilt angle increases (panel (C)). In the case with , both reverse and forward compression region are not formed. As varies from to , the value of varies from 0.87 to 1.03 in the reverse compression regions and from 0.75 to 0.97 in the forward compression regions. When and , the value of is almost the same.

In general, the particle acceleration effect in the reverse compression region is primarily affected by the solar wind speed difference, especially when the difference is larger than 390

. However, the acceleration effect in the forward compression region is mainly influenced by the slow (mean) solar wind speed, especially when the slow solar wind is smaller than 300

. The reverse compression regions could accelerate protons to higher energy than the forward compression regions in most cases. However, if the slow solar wind speed is small or large (Case 1 and Case 5 in Set B), the forward compression region could accelerate particles more strongly than the reversed compression region (for the protons with 5 MeV). The

of the SIRs usually varies between 200

and 500

in the observation [

21]. Therefore, the particle acceleration efficiency observed in the reverse compression is expected to be usually higher than in the forward compression region.

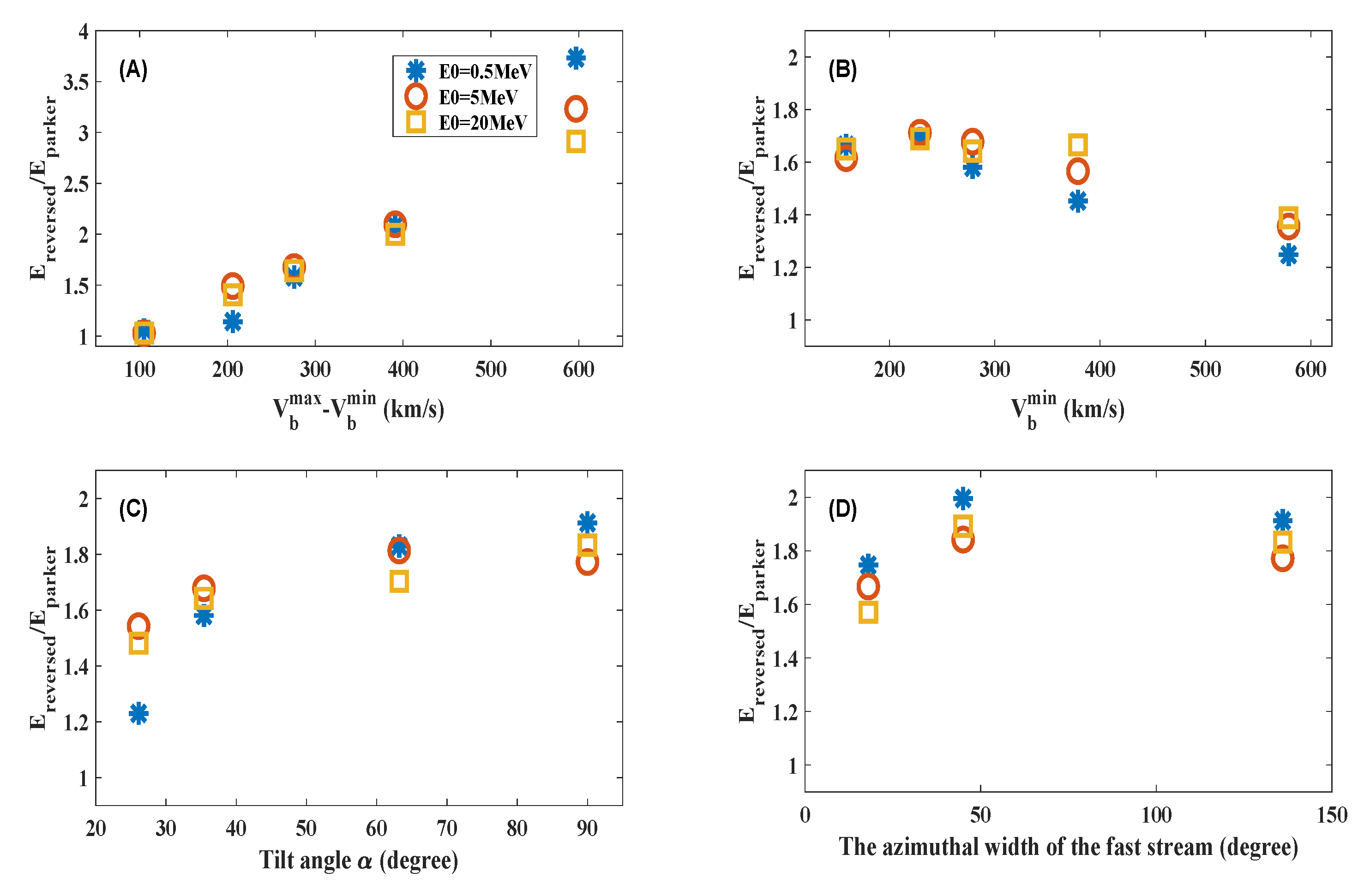

Figure 4 shows the maximum ratio of the maximum energy in the reversed compression region to that in the approximated Parker field at 1 AU in the first 60 hours versus the CIR parameters. The blue asterisks, red circles, and yellow squares are for protons with original energy of 0.5 MeV, 5 MeV, and 20 MeV, respectively. As can be seen from panel (D), for particles with different energies, the azimuthal width of the fast stream has similar effects on their acceleration. In all the panels, the values of

for 20 MeV particles are similar to those for 5 MeV particles. However, the acceleration of 0.5 MeV particles varies more with

(Set A),

(Set B), and tilt angle

(Set C) than particles with higher energy. Therefore, more attention must be paid to the influence of background parameters when studying particles at lower energies (sub-MeV particles).

3.3. The Intensity of SEP and the Parameters of CIRs

We then examine how different parameters affect particle intensities. Particles with energies ranging from 5 to 15 MeV are impulsively injected at of latitude in the inner boundary. The intensity distribution of 6.7-11.4 MeV particles in the solar equatorial plane is measured.

3.3.1. Peak Intensity and CIR Width

In this subsection, we investigate how the particle peak intensity related to the CIR width.

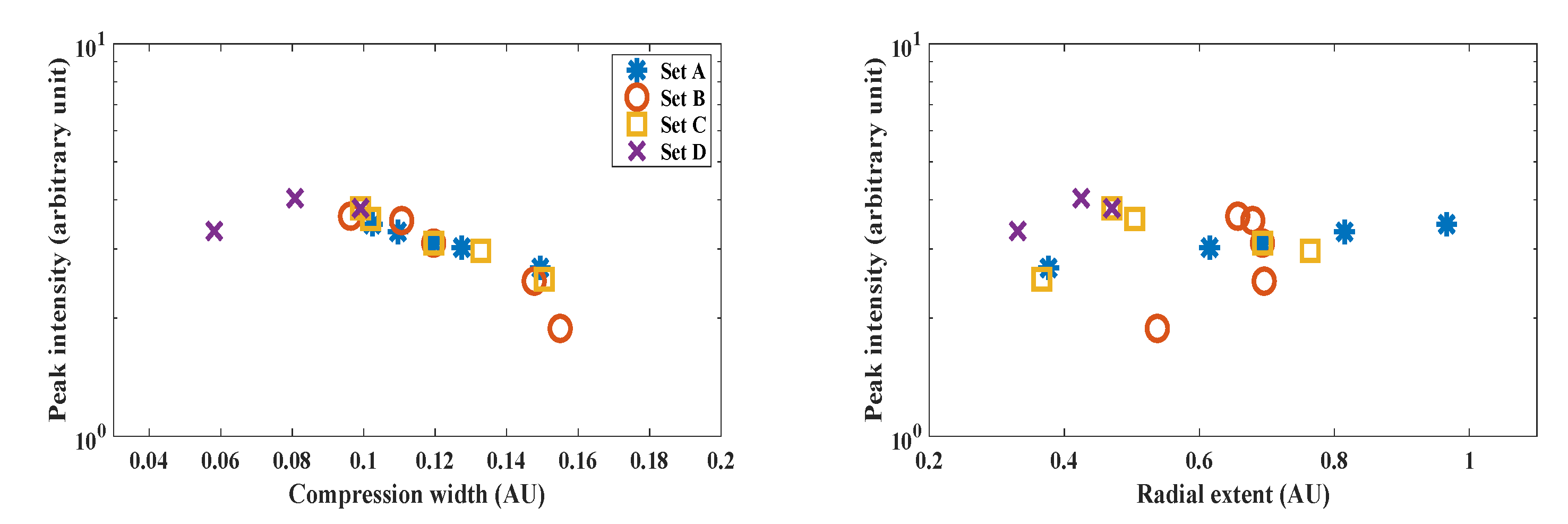

Figure 5 shows peak intensity versus the CIR width at 1 AU. The blue asterisks, red circles, yellow squares, and purple crosses indicate cases in Set A, Set B, Set C, and Set D, respectively.

Giacalone et al. (2002) [

7] found that the thinner the width of the compression, the higher the efficiency of the acceleration. The left panel in

Figure 5 shows peak intensity versus the compression width

. Our results of Set A, Set B, and Set C are consistent with theirs. For Set D, the peak intensity stays essentially constant as the compression width increases. The array of CIRs is more compact with the thinner fast stream, but the width of the fast stream does not affect the degree of CIR compression.

Bucík et al. (2011) [

29] analysed the observed events and found no relationship between the peak intensity (for 0.189 MeV/n He) and compression width for CIRs not bounded by reverse shocks. They interpreted that the compression is weak and therefore the acceleration could not operate. The compression width in their study corresponds to the radial extent

in our results. The right panel in

Figure 5 shows peak intensity versus the radial extent

. Our result shows the peak intensity does not correlate well with the pressure-derived radial extent

when a compressional mechanism dominates. The peak intensity is not sensitive to the CIR parameters and varies within one order of magnitude in different cases. Therefore, the impact of the CIR parameter on peak intensity is not significant in the CIRs without shocks. Our results are consistent with the statistical study of [

29].

3.3.2. The Temporal-Spatial Intenisty Distribution in Different CIRs

In this subsection, we investigate how the particle intensity varying with time and space related to the CIR parameters.

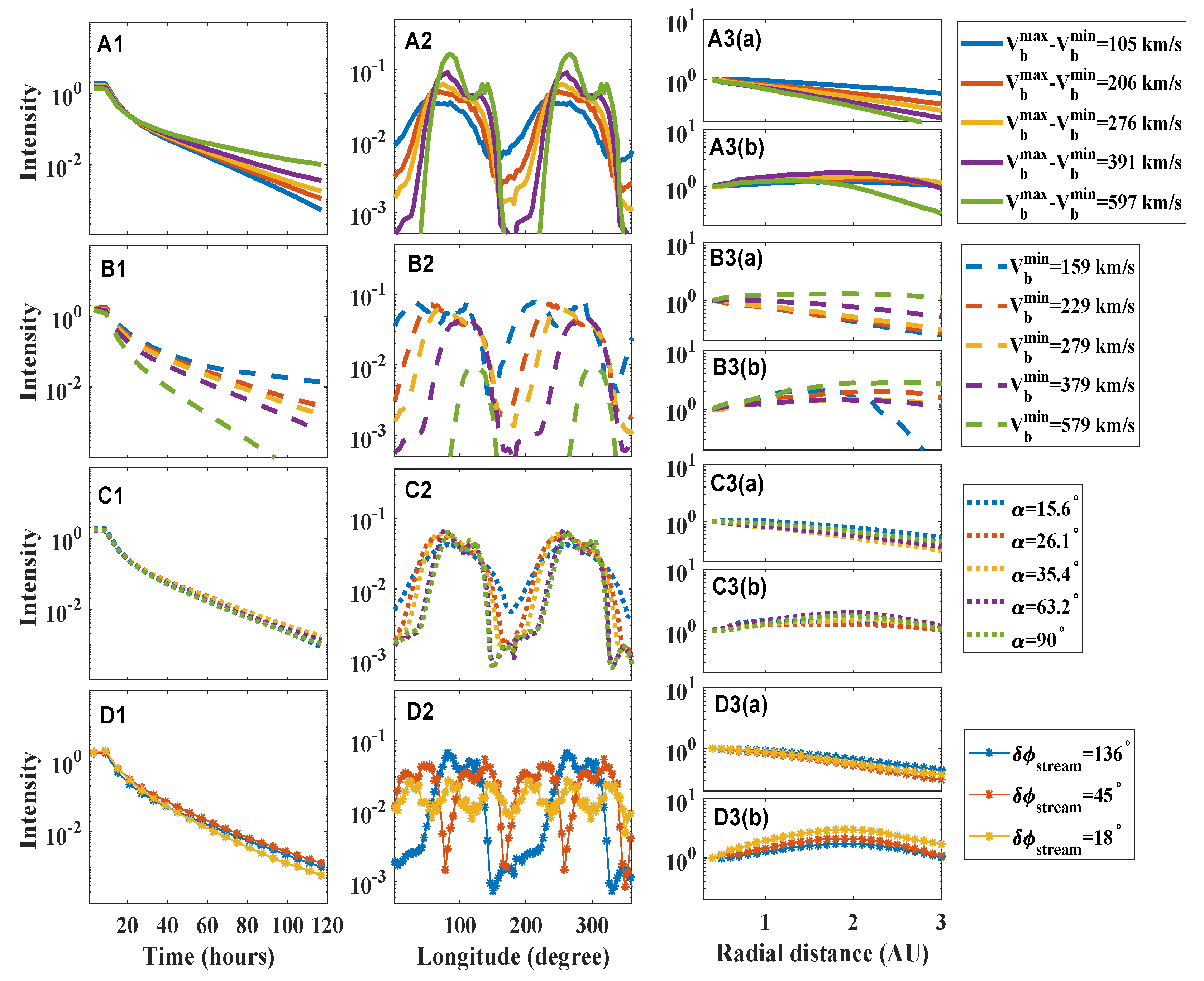

The distribution of particle intensity with time, longitude, and radial distance for different cases is illustrated in

Figure 6. The rows from top to bottom display the cases in Set A, B, C, and D, respectively . The columns from left to right represent the distribution of particle intensity varying with time, longitude, and radial distance, respectively.

Panel A1, B1, C1, and D1 show the variation of longitudinal-averaged particle intensity with time at 1 AU. As shown in the panels, the background parameters have little effect on the temporal peak intensity (longitudinally averaged). The intensity variation with time was little affected by the tilt angle (panel C1) and the azimuthal width of the fast stream (panel D1). During the initial 30 hours of the event, the intensity is mainly affected by the slow solar wind speed (panel B1) due to the stronger adiabatic cooling in the faster solar wind. As the event continues, the impact of the solar wind speed difference (panel A1) increases. This is mainly due to the acceleration effect. By 120 hours, the particle intensity difference in cases with different solar wind speeds has already exceeded one order of magnitude.

Panel A2, B2, C2, and D2 display the distribution of particle intensity at 1 AU with longitude at 60 hours. The longitudinal peak intensity is mainly influenced by the solar wind speed difference (panel A2), since the acceleration effect on the particles is stronger when the solar wind speed difference is larger. The intensity variability in the longitudinal direction is also dominated by the solar wind speed difference. On the one hand, the larger the solar wind speed difference, the stronger the acceleration effect in the compressed region. On the other hand, the larger the fast solar wind speed, the stronger the adiabatic cooling effect and the sparser the magnetic field in the rarefaction region. The intensity variation is secondarily affected by the azimuthal width of the fast stream (panel D2). This is due to the fact that more compactly arranged CIRs weaken the effect in the rarefaction region and thus reduce the longitudinal intensity variation. The slow solar wind speed (panel B2) also affects the longitudinal variation. The adiabatic cooling effect is weaker in the slower solar wind and therefore the particle intensity decreases less outside the compression region. The tilt angle (panel C2) has a slight effect on the amplitude, and only the case with a small tilt angle () has a slighter longitudinal intensity variation.

The longitudinal width of the particle intensity (intensity above a certain value, say

) is also affected by the background parameters. It is obvious that the azimuthal width of the fast stream (panel D2) affects the width. The smaller the width of the fast stream, the more CIR structures will be formed, and the smaller the particle width will be. The solar wind speed difference has the least effect on the particle intensity width, e.g. the difference in widths (with intensities greater than

) is at most

between cases in panel A1 (the smaller the speed difference, the wider the width). The effect of the slow solar wind speed (panel B2) on the width seems to be large. The smaller the slow solar wind speed, the wider the particle intensity width. The difference between different cases in panel B2 can be more than

. However, slow solar wind speeds are not that extreme in actual observations. The width difference is about

between the cases with slow solar wind speeds of 229

and 379

. The tilt angle also has a significant effect. The smaller the tilt angle, the larger the particle width. The difference in width between the cases with a tilt angle of

and

is about

. It is important to note that the regularity of the longitudinal width of the particles also depends on the chosen threshold (here

). The width of particle intensity differs from the CIR width discussed earlier (see red asterisks in Fig.

Figure 2). On the one hand, the chosen criteria (threshold, etc.) will affect the results. On the other hand, the particle intensity will be influenced by various effects (such as the focusing effect, the adiabatic effect, etc.) other than the compression width of the CIRs. In addition, the width of particle intensity also varies with time.

Column 3 in

Figure 6 displays the distribution of the longitudinal-averaged particle intensity with radial distance at 30 hours (panels A3(a)-D3(a)) and 120 hours (panels A3(b)-D3(b)), normalized by the intensity at 0.3 AU.

At 30 hours, the radial distribution of the particle intensity is mainly influenced by the solar wind speed (panel A3 (a) and panel B3 (a)). The larger the solar wind speed difference and the smaller the slow solar wind speed, the faster the particle intensity decreases with radial distance. On the one hand, in the solar wind at higher speed, particles reaching larger radial distances experience larger adiabatic effects and thus they decrease faster with radial distance. On the other hand, the focusing length is smaller in the slower solar wind, causing particles to propagate more slowly to larger radial distances. These two propagation effects combined affect the variation of the particle intensity with radius at this time. The effects of the tilt angle and the azimuthal width of the fast stream are small.

At 120 hours, the distribution of particle intensity with radial distance is flatter, since particles have sufficient time to propagate and particles are accelerated at larger radial distances. Also for these reasons, the effect of the solar wind speed on the radial distribution of particles is reduced, except for a few extreme cases. The case with of 597 in Set A (green solid line in panel A3(b)) and the case with the of 159 in Set B (blue solid line in panel B3(b)) have a roll over of the particle intensities at larger radial distance. This is mainly due to the extension of the magnetic field lines to higher latitudes. For larger compression ratios, the magnetic field lines are more strongly bent towards the north and south. Since the particles are only injected in the latitude range, the more the magnetic lines bend toward higher latitudes, the more particles leave the solar equatorial plane at smaller radial distances, resulting in a sudden drop in particle intensity with radius. At this time, the effect of the tilt angle is still small, but the effect of the azimuthal width of the fast stream is slightly increased.