1. Introduction

Life expectancy is steadily increasing worldwide. The same holds true for Japan, where Japanese men and women had an average life expectancy of 81.05 years and 87.09 years, respectively, in 2022, making Japanese the longest-living citizens globally [

1]. Although an increase in life expectancy is a welcome development, it poses some medical challenges. The difference between healthy life expectancy and average life expectancy in Japan is approximately 9 years for men and 12 years for women [

2]. Currently, the Japanese government is implementing various measures to narrow the gap between healthy life expectancy and average life expectancy. Disease prevention and management are indubitably important. In particular, regular effective exercise, which is crucial for disease prevention and management, is recommended to extend the healthy life expectancy [

3]. Exercise interventions for patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), one of the issues affecting the elderly, do not seem to substantially improve the cognitive functions, except for the language function [

4], but have been shown to slow down the decline in cognitive function [

5], maintain and improve the patients’ activities of daily living, and improve the caregivers’ quality of life [

6].

In Japan, the level of independence in daily living among elderly individuals at home is assessed using a six-point index based on disability severity. The government subsidizes the costs of assistance provided for household chores, daytime rehabilitation training, and home clinical care. A 2-week functional recovery training program is also offered to individuals who are deemed to require assistance, primarily because of osteoarticular disease, and who mostly exhibit independence in daily living. This training program aims to improve or maintain motor and cognitive functions and mainly involves gait training (e.g., stretching exercises), muscle training, aerobic training, and cross-step training.

The current study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a personalized dual-task intervention that combined exercise with cognitive tasks in improving physical and cognitive functions among independently living elderly individuals. In this study, two groups of hospitalized elderly patients who exhibited independence in daily living and participated in a functional training program twice weekly were compared. The first group received standard 20-min cross-step training alone, whereas the second group received standard 20-min cross-step training and performed the dual tasks of reading and answering questions on an LCD screen while verbalizing the text. Statistical comparison of the results between the two groups showed that dual-task training was more effective than single-task training.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This multicenter, prospective intervention study adopted a randomized trial design and enrolled outpatients from April 2023 to October 2023 at seven different hospitals in Japan. Patient data were collected from Izumi Memorial Hospital, Kawakita Sogo Hospital, Nishi-Hiroshima Rehabilitation Hospital, Sogo Tokyo Hospital, Kyoto Konoe Rehabilitation Hospital, Kyoto O’Hara Memorial Hospital, and Aomori Shin-Toshi Hospital and were subsequently analyzed.

2.2. Participants

The inclusion criteria were as follows: patients aged >65 years who were mostly independent in their activities of daily living. The participants were unaware of their group assignments, study hypotheses, and primary outcome measures.

At each institution, the patients were randomly assigned using a random number table to either the robot-assisted therapy group (cross-step exercises in which the participants read aloud the questions presented on the screen, contemplated them, and then responded) or the conventional therapy group (cross-step exercises only). For a stratified analysis, the patients were divided into two groups (namely, mild and severe) according to baseline (pretreatment) severity, as assessed using the 30-s chair stand test (CS-30) score and Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Japanese version (MoCA-J) score (see below). Differences between the intervention groups were analyzed using G*Power, with repeated-measures analysis of covariance (between factors) with the following values: effect size f = 0.30, α = 0.05, 1-β = 0.80, and number of measurements = 3. Power analysis indicated that the required number of study patients was 88 (22 × 4 groups).

2.3. "Robot-Assisted" and Conventional Therapy Programs

The participants were patients who visited seven different hospitals. The group receiving the 20-min robot-assisted session was compared to the group receiving traditional functional restoration training at these hospitals. Assessments were conducted before, during, and after the start of the study. During the study period, each participant underwent a total of 8 training sessions twice a week, excluding evaluation days and Sundays.

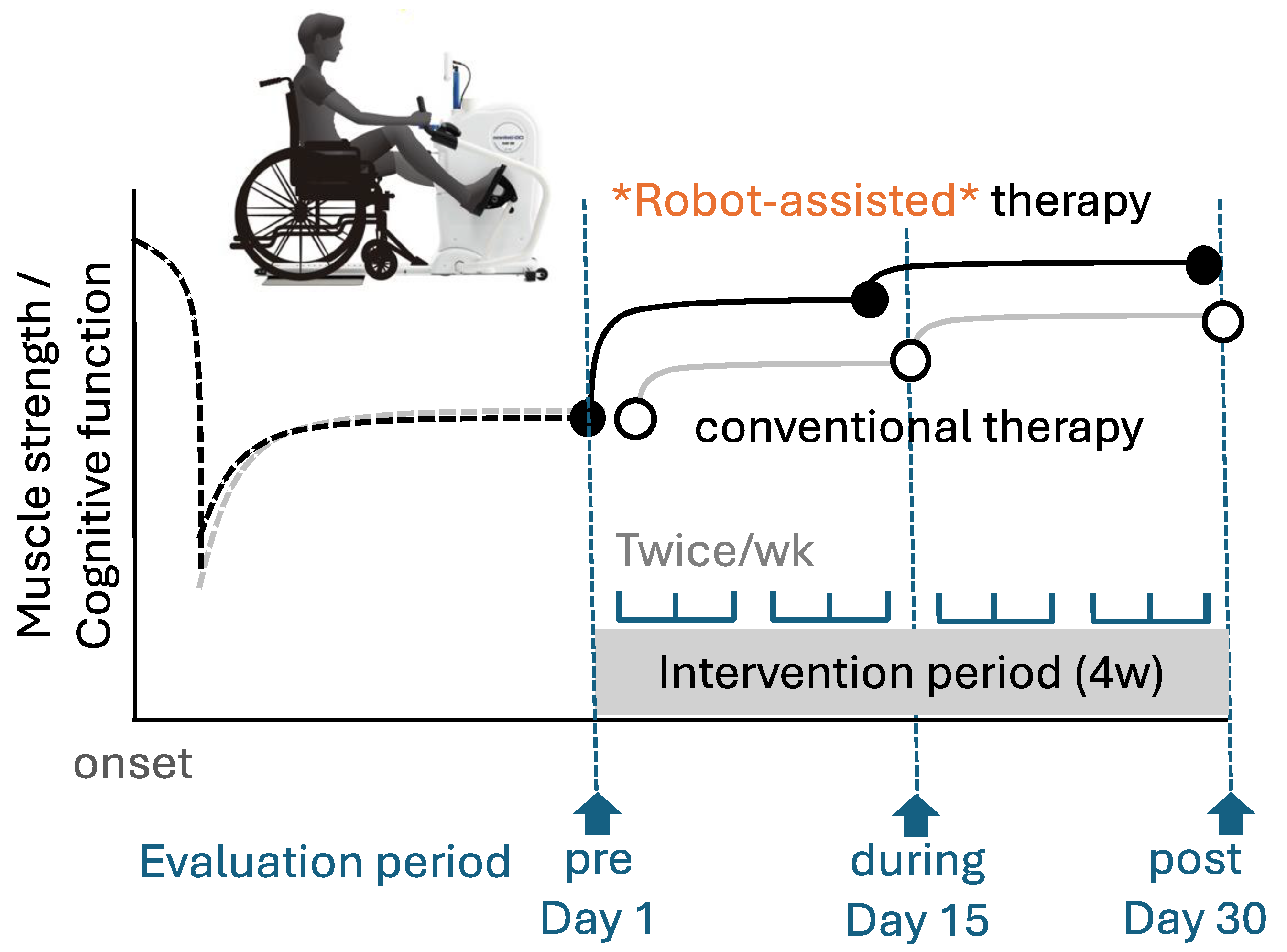

The equipment used for the 20-min robot-assisted session was Cross Step WE-100 (OG Wellness, Okayama, Japan), which is designed to facilitate simultaneous movements of the upper and lower limbs, offering optimal aerobic exercise for the elderly. Physical training included upper-limb movements with the left and right arms gripping the handles, as well as simultaneous lower-limb movements with the left and right feet placed on the foot pedals (

Figure 1). The alternating movements of the arms and lower extremities were coordinated with the movements of the entire body, thereby forcing the exercise of the major limbs and other body muscle groups. The pulse rate was recorded at the auricle throughout the 20-min exercise.

The exercise machine was connected to a personal computer that displayed questions on an LCD screen and provided voice instructions. Each participant wore a microphone with headphones and responded by following the voice instructions while viewing the LCD display.

The Cross Step device offers four exercise modes. In this study, the “multitasking mode,” which allows the user to set upper and lower heart rate limits and perform controlled exercises within that range, was selected. The upper pulse rate limit was set as 200 minus age in years, the upper heart rate limit was set as the upper pulse rate minus 20, and the lower pulse rate limit was set as the lower pulse rate minus 40. The target heart rate for this study was set at 100–110 beats per minute.

Because the exercise duration was set at 20 min, the initial 30 s was set for warm-up, during which coordinated movements of the upper and lower limbs were performed. The countdown for the remaining 20 min commenced after the heart rate increased above the preset lower pulse rate limit. During this period, the LCD display flashed “warm up,” and instructions for responding to the questions was provided through the microphone and headphones. After the warm-up phase, the task mode began, and the task question was presented to the participants to be read aloud and answered. As the question was read, the time remaining to respond was displayed in the upper-left corner of the screen. Each participant was instructed to answer within this period. Failure to answer before the time limit expired was marked as an incorrect answer, and the system proceeded to the next question. This process continued throughout the 20-min exercise session, with participants alternating the movements of their upper and lower extremities while vocalizing their responses to the task displayed on the LCD screen. During the cool-down phase, the term “cool down” was flashed above the exercise time displayed on the screen.

The problems presented were generated by a private educational organization that supports education in Japan. A total of 550 arithmetic, Japanese, and puzzle problems were provided by Gaudia (Gaudia Co., Kanagawa, Japan), and a total of 281 social study questions were supplied by Nichinokenkanto (Nichinokenkanto Co., Kanagawa, Japan). The difficulty level of these questions was set at fifth-grade elementary school level. For instance, consider the following problem scenario: Japan comprises 47 prefectures. The shape of one of these prefectures was deliberately rotated, altering the typical map orientation. Subsequently, the elderly participants on training were instructed to identify which prefecture was depicted on the map. In another problem, the middle kanji character was removed from a 3 × 3 grid, and the elderly participants were prompted to determine which kanji character could be inserted to form a two-character idiom in conjunction with the surrounding kanji characters. Each question was meticulously crafted by three rehabilitation specialists to require not only memorization but also engagement of at least one of the following cognitive functions: executive function, attention, orientation, and visuospatial cognition.

The system was configured to allow the participants to answer a minimum of six questions within a 30-s timeframe from the moment when the question was presented and to answer 12 questions every 15 s during the exercise. The questions were randomly presented from those registered in the designated fields.

2.4. Variables and Timing

The participants were divided into intervention and control groups to verify the effectiveness of the robot-assisted therapy. Progress was investigated at three time points (

Figure 1). Sarcopenia was evaluated using the CS-30, which is particularly useful for assessing muscle strength as the main outcome [

7]. The chair stand test has been confirmed to be useful for evaluating muscle strength and physical performance [

8,

9]. The CS-30 score correlated with sarcopenia (odds ratio: 0.88; 95% confidence interval [95% CI]: 0.82–0.93). The optimal number of stands in the CS-30 that predicted sarcopenia was 15 for females (sensitivity, 76.4%; specificity, 76.8%) and 17 for males (sensitivity, 75.0%; specificity, 71.7%) [

7]. The patients were evaluated on admission (pre), during the intervention (during), and after the intervention (post) using the CS-30. Sarcopenia was defined as low muscle strength.

As for the secondary outcome, the MoCA-J score was utilized to determine the presence or absence of MCI using a MoCA-J score of <26 as the threshold [

10,

11].

All patients were diagnosed by attending physicians at each hospital. A licensed physical therapist or occupational therapist performed all screening and testing procedures.

For a stratified analysis, patients in the intervention and control groups were divided into a severe group (sarcopenia, CS-30 score <17 for men and <15 for women) and a mild/moderate cognitive impairment group (MoCA-J score <26).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The CS-30 and MoCA-J scores were used as objective variables in the repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc

t-tests for pairwise comparisons. Sex and age were used as covariates in the ANOVA. Analyses were performed using JASP software version 0.18.1 (

https://jasp-stats.org). Post-hoc comparisons were conducted using Tukey’s post-hoc correction. All objective variables were tested for data equality using Levene’s test and Mauchly’s sphericity test. A

p value of <0.05 denoted the presence of a statistically significant difference.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

The acquisition of informed consent from patients was waived because the analysis used anonymous clinical data obtained after each patient agreed to the treatment with written consent. The opt-out method was employed to obtain consent using a poster and website approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tokyo Jikei University Hospital (approval number: #32-338(10423); date of approval: 9th November 2021).

3. Results

3.1. Participants

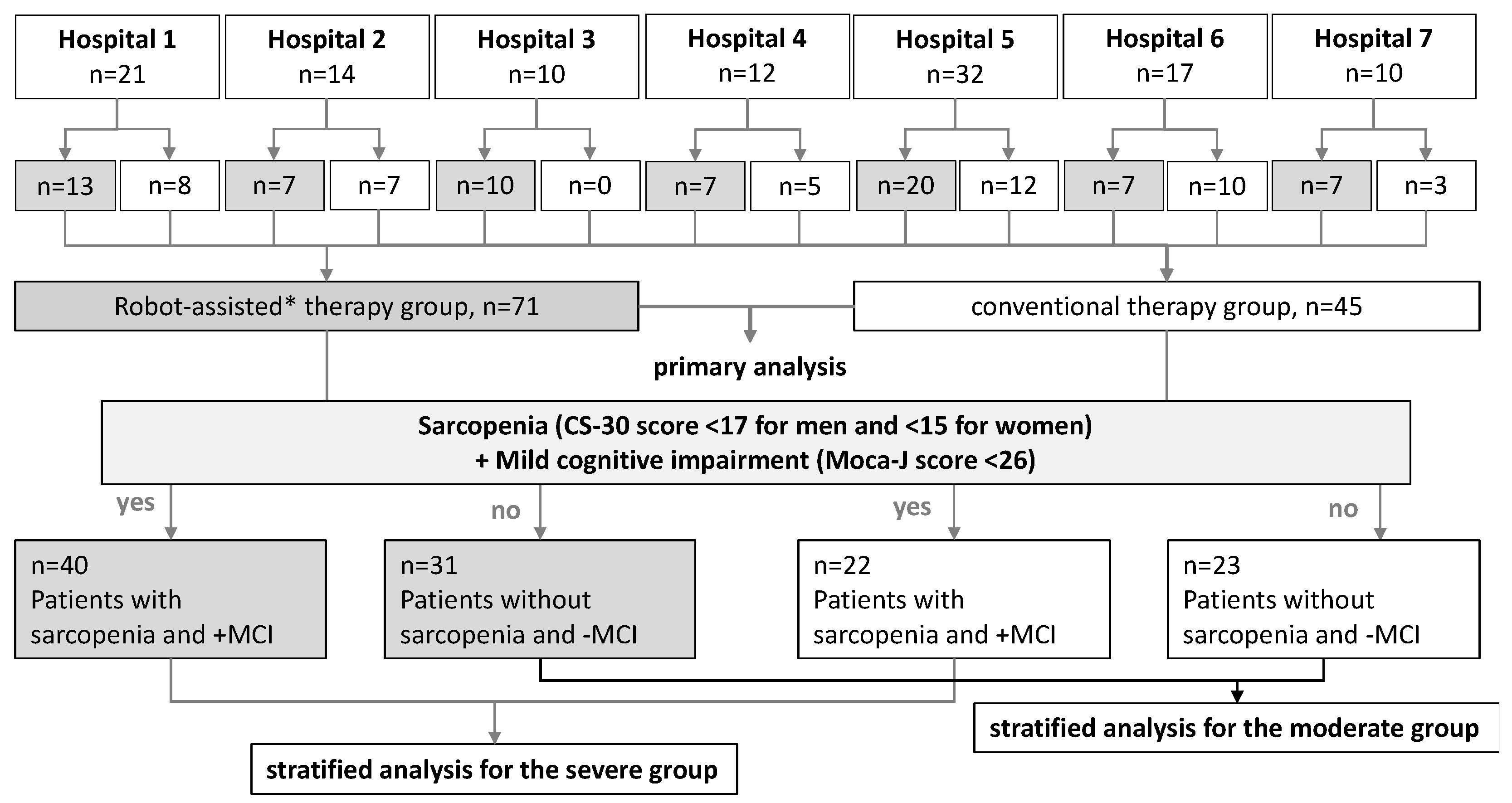

During the study period, rehabilitation was prescribed to 116 patients with a history of various conditions (e.g., cerebrovascular diseases, vertebral fractures, lower-limb fractures, angina pectoris, hypertension, hyperlipidemia) at all seven medical institutions. At each hospital, the patients were randomly assigned to either the robot-assisted or conventional therapy group. The number of patients varied among the participating hospitals and ranged from 10 to 32 per institution. All patients were included in the study (

Table 1), and there were no dropouts. Data from all 116 patients were analyzed (

Figure 2).

3.2. Descriptive Data

Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics of the patients. The number of patients randomly allocated to the robot-assisted and conventional therapy groups was 71 (61%) and 45 (39%), respectively. In addition to comparing the intervention groups, the robot-assisted and control groups were further divided into severe and moderate groups to perform a stratified analysis based on severity, as assessed using the presence or absence of sarcopenia and cognitive dysfunction (

Figure 2).

3.3. Outcome Data

The CS-30 score (median, first to third quarters) before the intervention was 14 (range, 10–17) in the robot-assisted group and 14 (range, 11–17) in the conventional therapy group. The total MoCA-J score before the intervention was 22 (range, 20–24) in the robot-assisted group and 23 (range, 21–26) in the conventional therapy group. The Barthel index score was very high in almost all patients, irrespective of background, intervention group, and severity (

Table 1), indicating that they were independent in daily self-care. The power grip, CS-30, MoCA-J, and Barthel index scores did not differ between the robot-assisted and control groups; however, significant differences in these parameters were noted between the severe and moderate groups at baseline (

Table 1).

3.4. Effects of the Interventions on the Lower-Limb Function

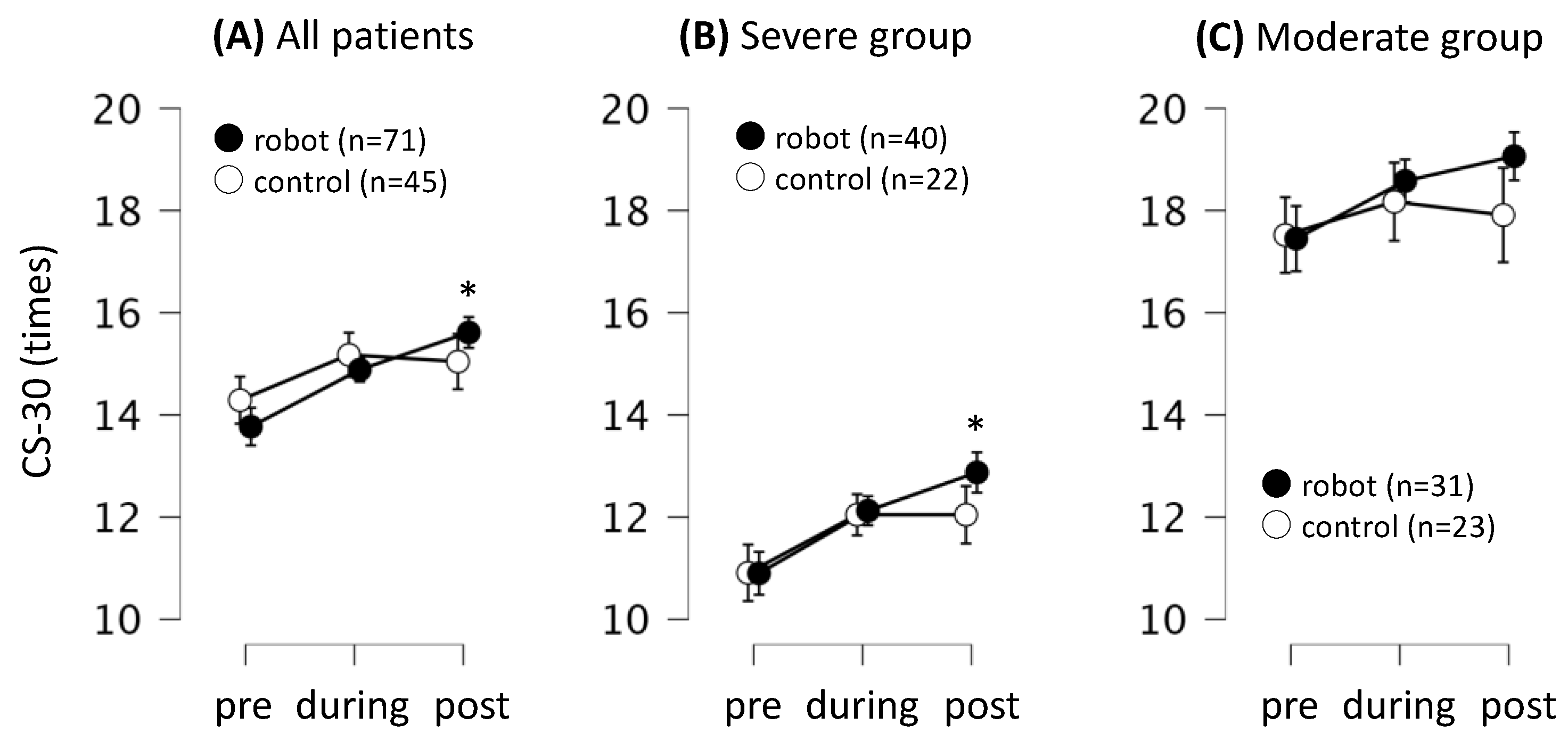

Further analysis compared the effects of each intervention on the CS-30 score. The two interventions showed no significant differences in the changes in the lower-limb function, as assessed using the CS-30 score (time course × group interaction;

F = 0.76,

p = 0.46, η2 = 0.00, by Greenhouse-Geisser sphericity correction). The CS-30 score of the robot-assisted group increased by approximately 1.7 times at post-intervention, and the improvement over time was significant relative to the pre-intervention score (mean difference = 1.7, 95% CI: 0.3–3.2,

t = 3.57,

pTukey = 0.01, Cohen’s

d = 0.31). Similar results were obtained for the severe group (mean difference = 2.0, 95% CI: 0.4–3.6,

t = 3.75,

pTukey < 0.01, Cohen’s

d = 0.56), but not for the moderate group (mean difference = 1.1, 95% CI: 3.8–5.9,

t = 0.66,

pTukey = 0.69, Cohen’s

d = 0.23). No significant changes in the lower-limb function were observed in the conventional therapy group (

p > 0.05;

Figure 3 and

Table 2).

3.5. Effects of the Interventions on the Cognitive Function

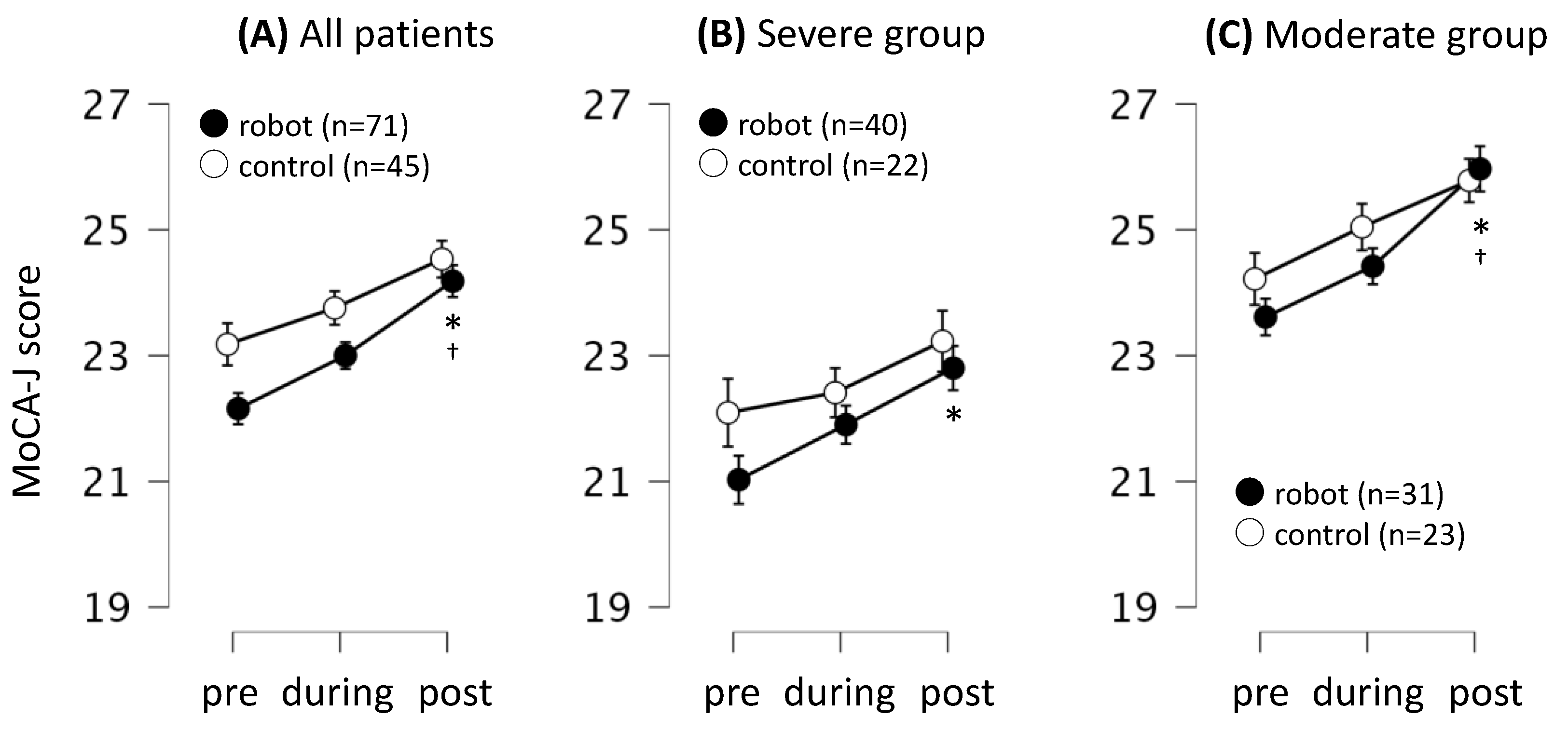

The effects of each intervention on the cognitive function were also analyzed using the MoCA-J score. The trend for the changes in cognitive function was similar between the robot-assisted and conventional therapy groups (time course × group interaction;

F = 0.71,

p = 0.49, η

2 < 0.01;

Figure 4). In the robot-assisted group, the MoCA-J score was higher after the intervention than before the pre-intervention (mean difference = 2.0, 95% CI: 1.0–3.0,

t = 5.74,

pTukey < 0.01, Cohen’s

d = 0.56). Furthermore, the MoCA-J score after the intervention was higher than that during the intervention (mean difference = 1.2, 95% CI: 0.1–2.2,

t = 3.38,

pTukey = 0.01, Cohen’s

d = 0.33). The intervention increased the MoCA-J score in both the severe group (mean difference = 2.6, 95% CI: 0.1–3.0,

t = 3.23,

pTukey = 0.02, Cohen’s

d = 0.54) and moderate group (mean difference = 2.6, 95% CI: 1.2–3.9,

t = 5.73,

pTukey < 0.01, Cohen’s

d = 0.70) compared to the respective baseline values. Furthermore, the MoCA-J score of the moderate group after the intervention was higher than that during the intervention (mean difference = 1.6, 95% CI: 0.2–2.9,

t = 3.48,

pTukey = 0.04, Cohen’s

d = 0.43). However, the changes in the cognitive function observed in the conventional group were not statistically significant (

p > 0.05) (

Figure 4 and

Table 3).

4. Discussion

This randomized trial revealed that our individualized training program tailored for independently living older adults resulted in improvements in the CS-30 and MoCA-J scores only in the dual-task intervention group. The CS-30, which is often used as a screening tool for sarcopenia in elderly Japanese individuals and correlates with lower-limb extensor muscle strength [

7], showed greater improvement in the intervention group with severe conditions (sarcopenia and MCI). The MoCA-J score improved not only in the intervention group with severe conditions but also in the group with mild conditions (without sarcopenia and MCI). The minimal clinically important difference of MoCA was approximately 1.0–2.2, indicating that the improvement in the MoCA score was observed even from the second week of the intervention. While elderly Japanese individuals are known to have a slim physique, our findings suggest that combining cognitive training with conventional cross-step training is potentially highly effective in improving balance, posture, gait, and cognitive functions in elderly men and women.

Dual-task paradigms, which are primarily investigated in psychology, often focus on the assessment of changes following the completion of two simultaneous tasks. Previous studies reported the favorable outcomes of training on balance and gait across various populations, including the elderly [12-14] and patients with stroke [

15]. Intervention studies also showed improvements in locomotion amplitude and velocity during walking after dual-task training in elderly individuals [

12]. Moreover, independently living elderly individuals exhibited improvements in balance and gait performance with dual-task engagement. Notably, a previous study of independently living elderly participants who completed 21 sessions (40 min/session) of dual-task training over a 7-week period reported significant improvements in gait speed, lower-limb muscle strength, and reaction time in cognitive tasks (specifically, attention dispersion) [

13]. Another study reported that elderly participants exhibited improved walking ability after completing 45-min dual-task training sessions thrice weekly for 8 weeks [

14]. However, the improvements observed after another dual-task intervention that incorporated verbal tasks in community-dwelling patients with stroke varied, with the Stroop dual-task intervention showing the most significant enhancement. Inconsistent results were reported for the improvement in walking speed with time and speech tasks, which were not part of the training. The latter findings suggest a potential limitation in the translation of training effects to dual cognitive-motor tasks [

15].

The simultaneous processing and execution of multiple tasks become increasingly challenging with age, particularly in individuals with cognitive decline or impairment. In addition to the processing capacity required for each task, the effective allocation and division of attention are crucial for the proper handling of multiple tasks. Balance control is commonly impaired under dual-task conditions in the elderly population. Given that compromised balance during dual-task situations can predict adverse outcomes such as falls [

16,

17], in addition to cognitive and physical decline, interventions aimed at enhancing balance during dual-task scenarios [

18,

19] have been recognized as important medical necessities in aging societies [

20,

21].

In this study, cross-step exercise training was performed. While cross-step exercise, aerobics, and treadmill walking are commonly employed for lower-limb training in the elderly in Japan, we opted for the cross-step exercise to mitigate the risk of falls during dual-task performance. The cross-step equipment features a load setting that is adjustable according to the heart rate, ensuring that each participant receives a comparable training intensity. This approach aims to maintain consistent motor task levels, even after dual-task training sessions. A previous study suggested that the conduct of dual-task protocols, such as when patients with stroke are engaged simultaneously in voice and walking tasks, is often marred by cognitive-motor interference, with a resultant increase in execution time and fewer steps in any motor task owing to slower and reduced joint movements [

22]. However, considering that our study entailed only 20 min of training sessions twice a week, we believe that the cognitive load was relatively low. Therefore, although our study evaluated the aspects of gait, further investigation of gait and related parameters remains a potential area for future research.

In Japan, compulsory education spans nine years from elementary to junior high school, providing individuals with foundational knowledge aligned with educational guidelines. The cognitive tasks used in this study were developed at a Japanese educational institution. During the actual study, when the participants read and answered the questions aloud while performing the cross-step exercises, it was observed that the questions for which they managed to provide correct answers were not at the junior high school level, but rather at the fifth-grade elementary school level. Hence, the difficulty level of the questions was set to the fifth-grade elementary school level. These cognitive tasks encompassed inhibitory control tasks (e.g., alternating letters of the alphabet, auditory selection responses) and working memory tasks (e.g., sequential subtraction, fluent verbal utterances, reverse spelling) [

23]. Even tasks that could not be solved required considerable effort from the elderly participants, particularly those demanding inhibitory control. Consequently, it can be inferred that brain hemodynamics during exercise are likely influenced by dual-task demands.

According to the task integration hypothesis, participants can develop coordination skills by practicing two tasks simultaneously, rather than practicing a single task. Efficient integration and coordination between the two tasks acquired during dual-task training are crucial for improving dual-task performance [

24]. This implied that the activities assigned to participants in the dual-task training group (task + cognitive task) were significantly more challenging than those assigned to participants in the single-task training group (task only).

We recently reported that aphasia in patients who are independent in their daily lives can be improved through repetitive high-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation, and speech and hearing training targeted at areas of language activation identified during a recitation task using functional magnetic resonance imaging [

25]. It is noteworthy that patients with aphasia and higher brain dysfunction benefit from responding aloud to tasks rather than simply contemplating them internally. This approach offers the advantage of identifying sites of language activation. Therefore, for elderly patients who may experience difficulties with higher brain functions, engaging in tasks involving reading, comprehending, and responding aloud during exercise is highly meaningful. In addition, even tasks deemed unsolvable may affect cerebral hemodynamics during exercise, particularly in dual-task scenarios, given that elderly individuals expend considerable efforts to complete tasks, especially those requiring inhibitory control.

This study has several limitations. In the present study, training was conducted twice a week and included 20-min sessions for ease of participation. Because most reports on dual-task training programs are based on a long-term follow-up of approximately six months, with training sessions lasting for 45–60 min at least three times a week, both the frequency of training sessions and the duration of training should be considered when comparing the effectiveness of different training programs reported in the literature. Therefore, whether dual-task training programs are effective in improving single-task performance should be clarified. It is also possible that the elderly participants in our study regularly visited the hospital for other illnesses, suggesting that they might not have specifically evaluated tasks other than those included in the training program. Additionally, we used the CS-30 only to measure performance under dual-task conditions. In future studies, if the number of training sessions is increased, the assessment of balance during walking should be correlated with improvements in fall prevention using more comprehensive measures of physical performance, such as gait speed and the inclination angle between the center of gravity and center of pressure. This should provide a better understanding of the effectiveness of both dual- and single-task training.

5. Conclusions

Our study showed that individualized dual-task training combining traditional interventions with a range of cognitive tasks was feasible for community-dwelling elderly individuals who were somewhat independent in their daily lives. Moreover, the participants successfully complied with instructions regarding attentional focus, directing their attention effectively towards the specified tasks and leading to measurable improvements in cognitive function. Therefore, the results obtained from this approach may be broadly applicable to older adults.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A. and T.H.; methodology, M.A.; software, T.H.; validation, T.H. and T.H.; statistical analysis, T.H.; investigation, M.A.; resources, T.H. and M.A.; data curation, T.H.; writing—original draft preparation, T.H.; writing—review and editing, T.H. and M.A.; visualization, T.H.; supervision, T.H. and M.A.; project administration, M.A. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Jikei University School of Medicine (approval number: 32-338(10423); date of approval: 9th November 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

All patients provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ikuo Kimura, PT Megumi Narita, PT Kazuki Ishizuka, and OT Naoto Otaki of Izumi Memorial Hospital, Dr. Satoshi Miyano, OT Misako Abe, and PT Shinsuke Muta of Sogo Tokyo Hospital, Dr. Takatugu Okamoto, PT Mai Watanabe, PT Hideyuki Matuda, and OT Syogo Uemori of Nishi-Hiroshima Rehabilitation Hospital, Dr. Kiyohito Kakita, OT Tuyoshi Masuda, PT Kaori Kishi, and OT Kengo Yoshihara of Kyoto O’Hara Memorial Hospital, Dr. Kensyaku Tei, Dr. Kazuaki Masuda, OT Yuki Owa, and OT Kou Watanabe of Aomori Shin-Toshi Hospital, Dr. Kouhei Miyamura of Kawakita Sogo Hospital, and OT Nobuko Nakatake of Kyoto Konoe Rehabilitation Hospital for their cooperation and advice throughout the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Director-General for Statistics, I.S.M.a.I.R.M.o.H. Labour and welfare Government of Japan. Abridged Life Tables for Japan 2022; Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: Tokyo, Japan, 2022; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, L.a.W. Vital Statistics; e-Stat, 2018–2021.

- Myers, J.; Prakash, M.; Froelicher, V.; Do, D.; Partington, S.; Atwood, J.E. Exercise capacity and mortality among men referred for exercise testing. N Engl J Med 2002, 346, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gates, N.; Fiatarone Singh, M.A.; Sachdev, P.S.; Valenzuela, M. The effect of exercise training on cognitive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013, 21, 1086–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venturelli, M.; Scarsini, R.; Schena, F. Six-month walking program changes cognitive and ADL performance in patients with Alzheimer. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2011, 26, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, D.E.; Mehling, W.; Wu, E.; Beristianos, M.; Yaffe, K.; Skultety, K.; Chesney, M.A. Preventing loss of independence through exercise (PLIE): a pilot clinical trial in older adults with dementia. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0113367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, S.; Ozaki, H.; Natsume, T.; Deng, P.; Yoshihara, T.; Nakagata, T.; Osawa, T.; Ishihara, Y.; Kitada, T.; Kimura, K.; et al. The 30-s chair stand test can be a useful tool for screening sarcopenia in elderly Japanese participants. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2021, 22, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.K.; Woo, J.; Assantachai, P.; Auyeung, T.W.; Chou, M.Y.; Iijima, K.; Jang, H.C.; Kang, L.; Kim, M.; Kim, S.; et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 Consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020, 21, 300–307e2 e302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Yasunaga, M.; Sugiyama, M.; Ijuin, M.; Sakuma, N.; Inagaki, H.; Iwasa, H.; Ura, C.; Yatomi, N.; et al. Brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment in older Japanese: validation of the Japanese version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2010, 10, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van het Reve, E.; de Bruin, E.D. Strength-balance supplemented with computerized cognitive training to improve dual task gait and divided attention in older adults: a multicenter randomized-controlled trial. BMC Geriatr 2014, 14, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adcock, M.; Sonder, F.; Schättin, A.; Gennaro, F.; de Bruin, E.D. A usability study of a multicomponent video game-based training for older adults. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act 2020, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azadian, E.; Torbati, H.R.; Kakhki, A.R.; Farahpour, N. The effect of dual task and executive training on pattern of gait in older adults with balance impairment: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2016, 62, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayouk, J.F.; Boucher, J.P.; Leroux, A. Balance training following stroke: effects of task-oriented exercises with and without altered sensory input. Int J Rehabil Res 2006, 29, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundin-Olsson, L.; Nyberg, L.; Gustafson, Y. ‘Stops walking when talking’ as a predictor of falls in elderly people. Lancet 1997, 349, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauchet, O.; Annweiler, C.; Allali, G.; Berrut, G.; Dubost, V. Dual task-related changes in gait performance in older adults: a new way of predicting recurrent falls? J Am Geriatr Soc 2008, 56, 181–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, A.F.; Olsson, E.; Wahlund, L.O. Effect of divided attention on gait in subjects with and without cognitive impairment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2007, 20, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manckoundia, P.; Pfitzenmeyer, P.; d’Athis, P.; Dubost, V.; Mourey, F. Impact of cognitive task on the posture of elderly subjects with Alzheimer’s disease compared to healthy elderly subjects. Mov Disord 2006, 21, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchet, O.; Dubost, V.; Herrmann, F.; Rabilloud, M.; Gonthier, R.; Kressig, R.W. Relationship between dual-task related gait changes and intrinsic risk factors for falls among transitional frail older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res 2005, 17, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausdorff, J.M.; Yogev, G.; Springer, S.; Simon, E.S.; Giladi, N. Walking is more like catching than tapping: gait in the elderly as a complex cognitive task. Exp Brain Res 2005, 164, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plummer-D’Amato, P.; Altmann, L.J.; Saracino, D.; Fox, E.; Behrman, A.L.; Marsiske, M. Interactions between cognitive tasks and gait after stroke: a dual task study. Gait Posture 2008, 27, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marusic, U.; Taube, W.; Morrison, S.A.; Biasutti, L.; Grassi, B.; De Pauw, K.; Meeusen, R.; Pisot, R.; Ruffieux, J. Aging effects on prefrontal cortex oxygenation in a posture-cognition dual-task: an fNIRS pilot study. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act 2019, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, A.F.; Larish, J.F.; Strayer, D.L. Training for attentional control in dual task settings: A comparison of young and old adults. J Exp Psychol Appl 1995, 1, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohara, K.; Kuriyama, C.; Hada, T.; Suzuki, S.; Nakayama, Y.; Abo, M. A pilot study verifying the effectiveness of high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in combination with intensive speech-language-hearing therapy in patients with chronic aphasia. NeuroRehabilitation 2021, 49, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).