1. Introduction

Children overweight and obesity are global health problems. The trend is growing everywhere. The prevalence of overweight (including obesity) among children and adolescents aged 5–19 has risen dramatically from just 8% in 1990 to 20% in 2022[

1,

2]. Diet patterns in countries with a traditional healthy diet, such as China or Spain, are progressively farther from the original food, recipes, and cooking methods. Fast food is increasingly available, published, and demanded by children and young people [

3]. At the same time, sedentary habits are increasing. Public policies against these problems are insufficient, poorly funded, and even handicapped by food industry pressures [

4].

Children’s obesity prevention must be embedded into health and education systems[

5]. School health education should be a priority because of its universal scope, children's unique learning power, and the opportunity to build healthy habits instead of replacing inappropriate ones [

6].

However, health education is usually approached only broadly from the natural sciences area and is focused primarily on theoretical knowledge; more practical content is introduced from physical education, traditionally oriented towards accomplishing cardiovascular exercises [

7]. Occasionally, educational programs from the health area are applied as extraordinary and extracurricular activities. Results obtained on these approaches are variable. Though usually favourable in the short term, they fail to modify behaviours effectively [

8,

9].

New teaching methodologies are now being considered to integrate learning objectives addressing content and skills. A good number of authors show and describe the positive impact that this kind of educational proposal has on students, including project-based learning and problem-based learning (PBL). Here, the teacher assumes a role as a mediator and guide of his students, replacing the former teacher-instructor model.

PBL implementation is not limited to using already developed resources in the classroom but focuses on creating new ones. On the contrary, it requires previous work, a careful and individualized dedication to each group, and consideration of individual needs. As far as we know, there are no reported experiences related to PBL applied to health, not only for achieving theoretical curricula content but also for awakening children’s consciousness regarding their health. We aimed to evaluate the feasibility and impact of an innovative and active methodology in the teaching and learning processes, addressing the necessary curricular knowledge and awareness related to acquiring healthy habits.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted an observational study in the fourth grade of primary school (9-year-old children). It was carried out at a semi-private school with two lines (25-27 students each) for four consecutive years. The chosen topic was related to the knowledge about the human body, health, and hygiene, emphasizing the importance of developing healthy habits. A meta-comprehensive project was designed for the first year, redesigned and oriented towards the problem-based learning approach for the next one, and implemented with some variations over the following two years to meet and respond to the characteristics and needs of each group. To verify the effectiveness of this methodology, one of the lines was established as a control group, while the experience was implemented in the other one. In control groups, traditional teacher-centred methods were used.

2.1. Design of Learning Methods

PBL usually starts from the pedagogical model based on the Theory of Multiple Intelligences [

10]. It depends on cooperative learning techniques and uses thinking-based learning strategies such as thinking routines, graphic organizers, and mind maps.

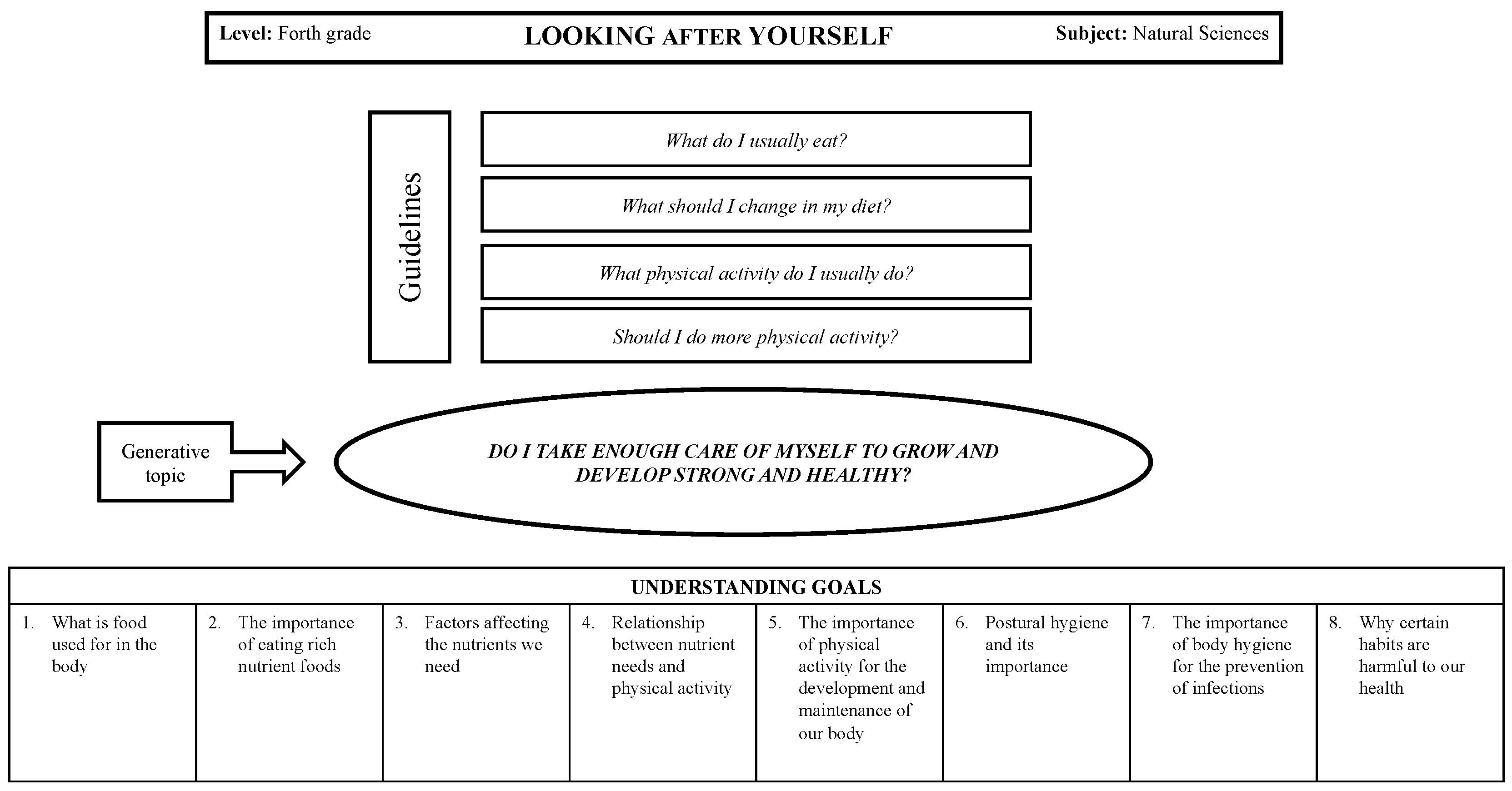

Figure 1 displays the design of questions generated and understanding goals.

The final objective of both projects was to elaborate a weekly menu according to the needs of the students.

Table 1 shows the

performance activities established to acquire the necessary knowledge. These activities were classified into start-up, follow-up, assessment, and evaluation activities. Graphic organizers were provided to support students in capturing, searching, synthesizing, and representing information. Mind mapping helped them to check, review, and self-assess the content to be learned. Students were also given several rubrics that allowed them to consider and assess all issues related to completing the different graphic organizers, individually and as a group. The rubrics and their achievement standards served as a guide to judge the quality of their work, both for teachers and students. The use of rubrics throughout the entire teaching and learning process allowed the students to progress in achieving the levels.

2.2. Sample and Data Collection

An opportunity sample was used through four academic years. The teacher who carried out the experience taught both lines for two school years (the second and third of the four years encompassing this study) and only one line for the other two. Children in the second line, the first and fourth years, formed the control group, which integrated 54 students. The exposed group included 159 students.

To evaluate the meta-comprehension project, we used the written test results established to control content acquisition and the improvement achieved when responding to the healthy habits questionnaire as a pre-test and post-test. This questionnaire, provided as Supplementary

Table 1, was designed “ad hoc.” The control group followed the traditional teaching method based on the textbook and performed the same tests and questionnaires.

2.3. Data Analysi

We estimated the mean and 95% confidence intervals for the written test results. The pre-and post-test results were compared using the paired means comparison test. We applied the variance analysis to compare the differences obtained between groups, considering both year and intervention.

2.4. Ethical Issues

We have done an observational study. The teaching methodology was registered in the annual scholar planning and approved by the school management. Only standard evaluation tools were used; to analyse and compare results, every child was identified by a number. No personal data were used.

3. Results

Table 2 summarises the mean pre-and post-tests, stratified by academic year and group. In all cases, the post-test results were significantly higher than the pre-test results, in the control group with a difference of 3.62 points (95% CI 3.23-4.00) and in the exposed groups with an average difference of 6.94 points (95% CI 6.32-7.56) (p<0.001). While all groups improved the number of correct answers, this improvement was higher in the intervention groups (p<0.001). It highlights that the baseline average scores obtained in the first year (2015-16 academic year) were clearly lower than those obtained in subsequent years. However, the increase was still significantly higher in the exposed lines.

The acquisition of curricular content was not particularly modified depending on the developed method.

Table 3 shows the written test results for each control and exposed group and the ranges they recovered. They did not show differences, except perhaps the wider range in the control groups, where some students reached lower scores.

Lastly, we analysed the answers to specific questions pre and post-test (Table 4). In the control group, there was a significant improvement for questions 6, 13, 14, and 16 to 28. In the exposed group, considerable progress was made in all the questions, but questions 1, 6, and 11 had a high percentage of correct answers since the pre-test. Comparing the students of both groups' pre-test answers, we realized that the rate of correct answers was higher in the control group only for questions 1 and 3. On the contrary, the percentage of correct answers was higher for 14 out of 28 questions in the exposed group.

4. Discussion

Our results show that by applying new methodologies, the acquisition of curricular content is similar to the groups with the teacher-centred groups. However, the pre-post comparison of the answers to the questionnaire showed a significantly better acquisition of health-related notions in the exposed group. For the questions addressed to conceptual items, the percentage of correct answers improved both in the intervention and control groups. The exposed group improved the questions about attitudes or behaviour intention.

Strength and limitation. We have designed and evaluated a problem-based learning focused on health: “Looking after yourself.” The guidelines applied and the final product are fully reproducible and can be adapted to different scholar levels. The mediating action of the teacher in the classroom must be considered. The teacher should have enough knowledge about the needs of the students, as well as a strong motivation regarding health, to offer them a better response and guidance, helping students to achieve more significant progress and commitment, precisely for those students who need it most.

Our study has some limitations. We used an opportunity sample in just one primary school. Despite including multiple intelligences and skills in the project, our intervention did not modify the scholar environment nor included parental involvement. Although we are aware of the importance of these factors having a high impact on health behaviour, it also means that this PBL approach could be applied in other socio-cultural contexts with the same or similar effect. Another limitation is the lack of some evaluation in the long term.

Nevertheless, the long-term effect depends on the successive interventions through scholarly time and on the parental implication. All the studies reviewed show a weakness regarding the outcome measurement. Curricula evaluation is focused on the cognitive area, so the knowledge acquired is easy to measure, but attitudinal achievements are subjectively evaluated. Health behaviour practices are sometimes assessed by self-administering questionnaires without any previous validation. We also measure attitudes through an “ad hoc” questionnaire. To grant the design, implementation, and evaluation of good teaching practices related to healthy diet and physical activity, reaching a consensus about the relevant outcome and the method used to measure it is essential.

School-based programs represent an ideal setting to enhance healthy eating. Nevertheless, elementary school teachers often display low nutritional knowledge, self-efficacy, and skills to deliver nutrition education effectively [

11]. There are too few structured scholarly interventions to promote healthy habits. Most of them are based on curricular content, frequently under the guidance of nutrition specialists or other healthcare professionals [

12]; however, those that apply cross-curricular strategies or practical learning are more effective [

11,

13,

14,

15]. Other published studies show community interventions improve healthy behaviours. Talks delivered by health professionals add knowledge, but their effects are time-dependent [

16,

17]. Practical learning by applying cooking sessions, school gardens, or even taste [

18] has been shown to increase children’s motivation related to the intake of fruits and vegetables [

19,

20]. Our study shows that, although all students improve their results, the increase is more significant in those who work on projects. PBL helps the understanding, organization, and synthesis of information, apart from promoting other interpersonal skills, but it does not replace the time of individual work to consolidate new knowledge [

21]. The questions in the questionnaires encompass curricular content and health knowledge as a product of reflection and critical thinking. At this point, intervention groups evidenced significantly greater progress, supporting that PBL helps people learn to think and develop critical, analytical, and reflective thinking. Therefore, the strategies to be carried out must be explicitly instructed and guided, requiring effort and capacity from both students and teachers [

21].

In an interesting review, Peralta et al. [

11,

13] show that resources developed for elementary school teachers to facilitate teaching healthy eating are scarce. Moreover, only some of them embed cross-curricular strategies, experimental learning strategies, or contingent reinforcement activities. The proposal PBL can be considered a cross-curricular strategy because it is developed in a transversal way into several curricula subjects, and it uses experimental learning strategies (e.g., a research project in which children actively look for ingredients of the usual food). PBL methodologies are feasible and can be developed with the usual available resources. This way, better and more homogeneous academic results can be achieved, and at the same time, students can be involved in critical consideration of related health issues. The final product integrates knowledge, beliefs, values, and attitudes, which are, in fact, the starting point for building healthy behaviour. We agree with Murimi et al. [

14] regarding the necessity of multicomponent interventions that are age-appropriate and have an adequate duration. Nevertheless, each effort counts, and all teachers could increase the health awareness of their pupils.

5. Conclusions

We can conclude that healthy lifestyle promotion can be integrated into school curricula using problem-based learning. This methodology allows the acquisition of content and helps children understand the importance of healthy choices regarding food and physical activity and incorporate them into their daily lives.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

BMH conducted the experiment, collected data, and wrote the original draft. PND and ABC participated in conceptualising and designing the methodology; BMH and ABC made data curation and formal analysis. All authors who reviewed and edited it have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We thank the school management, teachers, and fourth-primary-grade children at “la Asunción” School in Granada for contributing to this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lee, S.M. School health guidelines to promote healthy eating and physical activity. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2011, 60, 1–78. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight#:~:text=lived%20in%20Asia.-,Over%20390%20million%20children%20and%20adolescents%20aged%205%E2%80%9319%20years,1990%20to%2020%25%20in%202022. (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Bissell, K.; Baker, K.; Pember, S.E.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y. Changing the Face of Health Education via Health Interventions: Social Ecological Perspectives on New Media Technologies and Elementary Nutrition Education. Health Communication 2019, 34, 1575–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collin, J.; Hill, S.E.; Kandlik Eltanani, M.; Plotnikova, E.; Ralston, R.; Smith, K.E. Can public health reconcile profits and pandemics? An analysis of attitudes to commercial sector engagement in health policy and research. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0182612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.; Moore, T.H.; Hooper, L.; Gao, Y.; Zayegh, A.; Ijaz, S.; Elwenspoek, M.; Foxen, S.C.; Magee, L.; O’Malley, C.; et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Jimenez, R.; Al-Kazaz, M.; Jaslow, R.; Carvajal, I.; Fuster, V. Children Present a Window of Opportunity for Promoting Health: JACC Review Topic of the Week. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2018, 72, 3310–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herlitz, L.; MacIntyre, H.; Osborn, T.; Bonell, C. The sustainability of public health interventions in schools: A systematic review. Implementation Science 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laxer, R.E.; Dubin, J.A.; Brownson, R.C.; Cooke, M.; Chaurasia, A.; Leatherdale, S.T. Noncomprehensive and Intermittent Obesity-Related School Programs and Policies May Not Work: Evidence from the COMPASS Study. Journal of School Health 2019, 89, 818–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curran, T.; Wexler, L. School-Based Positive Youth Development: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of School Health 2017, 87, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, H. Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences; Books, B., Ed.; Basic Books: New York, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Peralta, L.R.; Dudley, D.A.; Cotton, W.G. Teaching Healthy Eating to Elementary School Students: A Scoping Review of Nutrition Education Resources. Journal of School Health 2016, 86, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balderas-Arteaga, N.; Mendez, K.; Gonzalez-Rocha, A.; Pacheco-Miranda, S.; Bonvecchio, A.; Denova-Gutiérrez, E. Healthy lifestyle interventions within the curriculum in school-age children: systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Promotion International 2024, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudley, D.; Cotton, W.; Peralta, L. Teaching Approaches and Strategies that Promote Healthy Eating in Primary School Children: A Systematic Review and Metha-Analysis. 2015.

- Murimi, M.W.; Moyeda-Carabaza, A.F.; Nguyen, B.; Saha, S.; Amin, R.; Njike, V. Factors that contribute to effective nutrition education interventions in children: A systematic review. Nutrition Reviews 2018, 76, 553–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoy-Cumillaf, A.; Fuentes-Merino, P.; Giakoni-Ramírez, F.; Duclos-Bastías, D.; Bruneau-Chávez, J.; Merellano-Navarro, E. The Effects of a Physical Activity Intervention on Adiposity, Physical Fitness and Motor Competence: A School-Based, Non-Randomized Controlled Trial. Children 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arufe Giráldez, V.; Puñal Abelenda, J.; Navarro-Patón, R.; Sanmiguel-Rodríguez, A. Impact of a Series of Educational Talks Taught by Health Professionals to Promote Healthy Snack Choices among Children. Children (Basel) 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menor-Rodriguez, M.J.; Cortés-Martín, J.; Rodríguez-Blanque, R.; Tovar-Gálvez, M.I.; Aguilar-Cordero, M.J.; Sánchez-García, J.C. Influence of an Educational Intervention on Eating Habits in School-Aged Children. Children 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battjes-Fries, M.C.E.; Haveman-Nies, A.; van Dongen, E.J.I.; Meester, H.J.; van den Top-Pullen, R.; de Graaf, K.; van ’t Veer, P. Effectiveness of Taste Lessons with and without additional experiential learning activities on children's psychosocial determinants of vegetables consumption. Appetite 2016, 105, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrenberg, S.; Leone, L.A.; Sharpe, B.; Reardon, K.; Anzman-Frasca, S. Using repeated exposure through hands-on cooking to increase children's preferences for fruits and vegetables. Appetite 2019, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahota, P.; Christian, M.; Day, R.; Cocks, K. The feasibility and acceptability of a primary school-based programme targeting diet and physical activity: The PhunkyFoods Programme. Pilot and Feasibility Studies 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swartz, R.J.; Costa, A.L.; Beyer, B.K.; Reagan, R.; Kallick, B. El aprendizaje basado en el pensamiento. Cómo desarrollar en los alumnos las competencias del siglo XXI., 3rd Edition ed.; Teachers Collegue Press. Columbia University: New York, 2015; p. 282. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).