1. Introduction

Benign Paroxysmal Torticollis (BPT) is a movement disorder and from a neurological semiotics should be described as cervical dystonia. [

1] BPT of infancy was first described by Snyder in 1969 [

2] as recurrent episodes of an abnormal rotation and inclination of the head to one side and attributed the cause to a vestibular disorder. He suggested that because the attacks observed in 4 patients evolved into benign paroxysmal vertigo(BPVC) as the years progressed. [

1,

2] Afterwards some authors postulated might BPT be due to vestibular disorders or those in central vestibular region or vestibule-cerebellar connections, especially when ataxia is associated. [

3] However, to date the etiology of BPT is not certain. There are relatively few reports of this functional disorder. In fact, only about 150 cases have been reported in the literature since 1969 [

2]. This is because BPT is a benign event, with favorable prognosis and little influence on the child's quality of life, the recurrence of critical episodes is important for the diagnosis, but it is not always possible because it escapes both the doctor and the parents who are not always worried about these manifestations. [

4,

5,

6] BPT is considered a rare disease and is described on the ORPHANET website [

7] where the prevalence of the disease is reported as < 1/1 000 000. In the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-II), [

8] BPT was reported in chapter “Infantile periodic syndromes that are commonly precursors of migraine”. Subsequently it has been displaced from the appendix section of classification in the body text of the ICHD-III beta version [

9]. Now in ICHD-III, 2018, [

10] the “Infantile periodic syndromes” are denominated “Episodic syndromes that may be associated with migraine. and in chapter 1.6 there are the Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome (CVS), Abdominal Migraine (AM), Benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood (BPVC) and in point 1.6.3 the BPT. Infantile episodic syndromes are characterized by reversible and stereotyped attacks, with periodic recurrence. Children are healthy and neurologically normal between attacks.

The purpose of this review is to evaluate the manifestation of the "migraine" condition of BPT through the comparison of case studies and above all the natural history of the disorder by carrying out comparison and evaluation of longitudinal studies.

3. Results

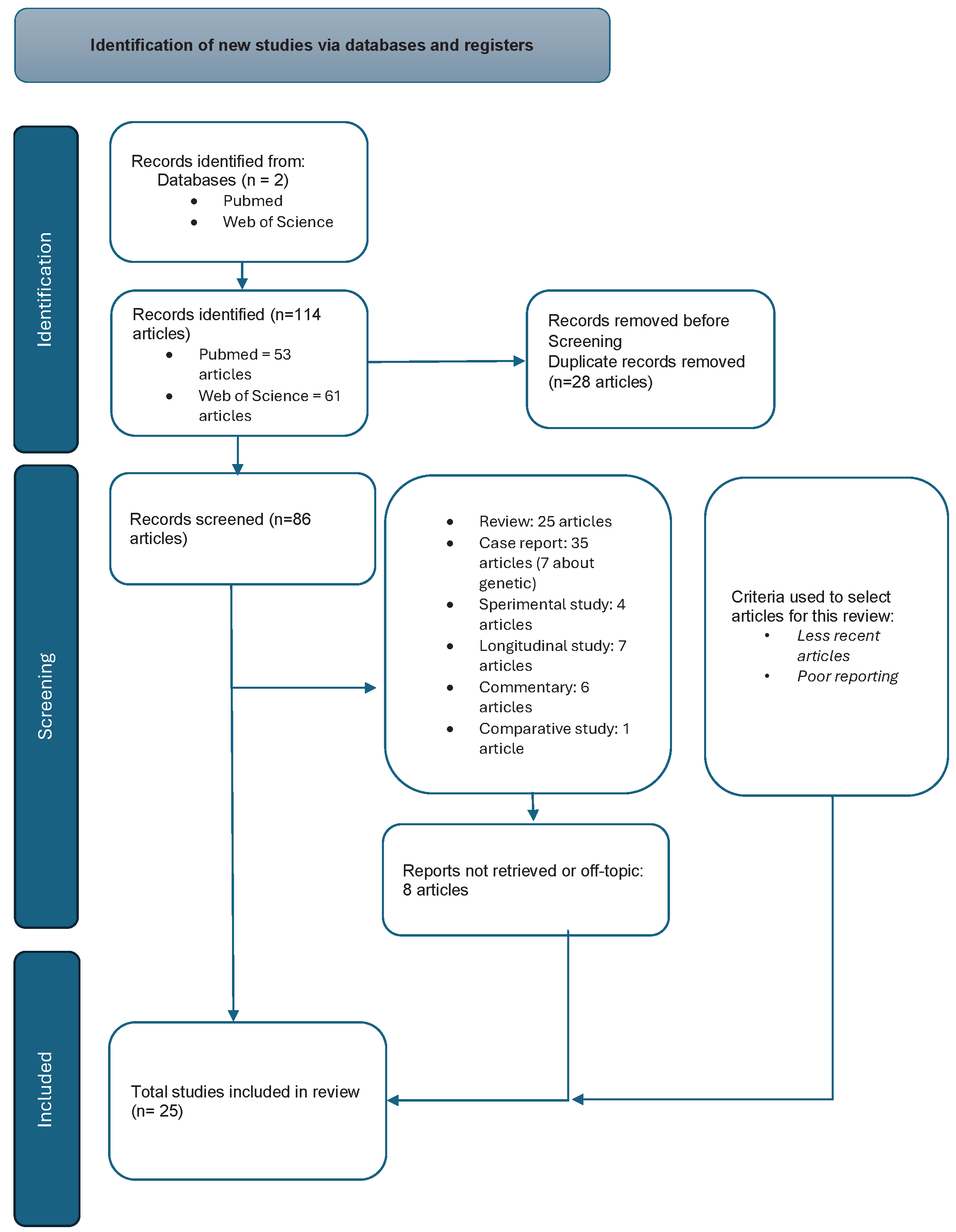

They were considered 114 articles, 53 recruited by PubMed and 61 by Web of Science; of these articles 25 are reviews. They were excluded because they were duplicates in the two databases 28 articles, 8 because they were out of topic. The articles were distinguished in the following way: 35 case report, 7 case report referred to genetic etiology, 4 experimental studies, 13 longitudinal studies, 6 commentaries and 1 comparative study.

In

Figure 1 we show the Prisma flow chart.

Table 1 lists the articles taken into consideration for the purpose of this review, of which 6 refer to longitudinal studies, 6 to genetic research studies and 8 to cases report. The studies reported in the table were published over a long period of time, from 1968 to 2021. This is due to the rarity of Benign Paroxysmal Torticollis (BPT) and they all refer to inconsistent case series with the exception of the studies by Drigo [

5], Moavero [

12] and Greene [

4] who report case series of more than 20 subjects also followed over time. 273 cases reported by 15 authors were evaluated, a higher number than previous reviews on this topic. Based on these reports we can outline a clinical manifestation of BPT and its evolution over.

The prevalence of BPT is difficult to establish. As already mentioned in the introduction, the diagnosis of BPT is underestimated and therefore the real prevalence and epidemiology is not possible. In this regard, the study by Al-Twaijri [

13] is very interesting. The Author, out of a total of 5,848 patients from the general pediatric neurology outpatient database, found 1,106 patients with migraine and 108 patients with equivalent migraine (1.8% of the total, 9.8% of migraine sufferers). Among migraine equivalents, BPT was present in 11 children (10.2% of patients with migraine equivalents). Another retrospective study showed that up to 70% of children with primaries headaches had a previous history of one of more of the episodic syndromes. [

14]

Table 1.

List of selected articles Authors.

Table 1.

List of selected articles Authors.

| Author, Year, Journal |

-

1.

C. Harrison, 1969, Am. J. Dis. Child[ 2] |

-

2.

T.Deonna, 1981, Arch. Dis. Child.[ 15] |

-

3.

A Hanukoglu, 1984, Clin. Pediatr. (Phila.) [ 16] |

-

4.

H D Bratt,1992, J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. [ 17] |

-

5.

P Drigo, 2000, Brain Dev. [ 5] |

-

6.

N J Giffin, 2002, Dev. Med. Child Neurol. [ 18] |

- 7.

Waleed A Al-Twaijri, 2002 Pediatr.Neurol. [ 13] |

-

8.

Fernández-Espuelas, 2006 Rev. Neurol. [ 1] |

-

9.

N Paul Rosman, 2009 Child Neurol. [ 19] |

- 10.

A Hadjipanayis, 2015, J. Paediatr. Child Health [ 6] |

- 11.

Jacob Brodsky, 2018, Eur. J. Paediatr.Neurol. EJPN Off. J. Eur. Paediatr. Neurol. Soc. [ 20] |

- 12.

Annika Danielsson, 2018, Dev. Med. Child Neurol. [ 21] |

- 13.

R Moavero, 2019, Cephalalgia Int. J. Headache [ 12] |

- 14.

Greene KA, 2021, Pediatr. Res. [ 4] |

- 15.

Meyeon Shin, 2016, Child Neurol. [ 22] |

- 16.

Marta Vila-Pueyo, 2014, Eur. J. Paediatr.Neurol. EJPN Off. J. Eur. Paediatr. Neurol. Soc. [ 23] |

- 17.

E Cuenca-León, 2008, Cephalalgia Int. J. Headache [ 24] |

- 18.

Rothner, AD, 2016, Headache [ 25] |

- 19.

Nuria García Segarra, 2014, J. Neurol.Sci [ 26] |

- 20.

Zlatanovic, D, 2017, Vojnosanit. Pregl. [ 27] |

Snyder [

2] described 12 cases of BPT in infants beginning at 2–8 months of age. The attacks were variably recurrent and self-limiting, without premonitory symptoms. The infants would develop a head tilt with head rotation. Some had no other symptoms; others showed paleness, agitation, irritability, and vomiting. Episodes could last hours or days. There didn't appear to be any relics. The attacks were spontaneous and stereotyped. They could occur 2-3 times a month. No predisposing events were reported. There was no loss of consciousness and/or awareness and the attacks could remain unilateral or alternating. Torticollis may be associated with tortipelvis and dystonic posture that may regress during sleep. Some children appear ataxic when attempting to walk during torticollis.

In

Table 2 all the essential clinical data of 15 Authors are summarized.

273 cases reported by 15 authors were evaluated. In 59% of cases described the torticollis lasted from a few hours to a few days, but in 41% of cases it persisted for more than 1 week; Only on the 4.5% of cases was detected history familial of BPT. The family history was positive for migraine in a range between 25% and 100% of cases described by Greene, [

4] Giffin, [

18] and Rosman [

19], for kinetosis in 54%, and for migraine and/or kinetosis in 83%. The onset is in the first few months of life, 5-8 months, the initially episodes are longer and more frequent, and regress by the age of 3-5 years. Perhaps this is due an immaturity of the central nervous and of the neurotransmitters in in the first months and years of life. BPT is often accompanied by symptoms like some features of migraine: vomiting, ataxia, pallor, irritability, apathy, and drowsiness. Subsequently the syndrome resolves spontaneously and may be replaced by more migrainous features. [

4,

5,

6,

12,

13,

18,

19,

21] Greene [

4] found 63 of 73 parents (90%) with migraine and 2 with Hemiplegic Migraine (HM). Brodsky [

20] found evolution of BPT to Benign Paroxysmal Vertigo of Childhood (BPVC) in 42.9% of cases, 15.4% of cases of BPVC to Vestibular Migraine (VM). 2 of 14 patients progressed through all three disorders. The prolonged torticollis episodes and abnormal rotary chair testing were associated with a higher risk of progression from BPT to BPVC. Greene [

4] show that 19% of patients observed (14/73 pt) developed migraine (median age 9.25 years, range 2.5-23) and 63% (n = 46) developed another episodic syndrome associated with migraine. The patients who developed migraine were greater in number among those with any migrainous symptoms during BPT attacks versus those without. The symptoms relieved were: phonophobia (58 vs. 21%, p = 0.02), photophobia and phonophobia (55 vs. 23%, p=0.05), and photophobia, phonophobia, and motion sensitivity (60 vs. 22%, p = 0.02). Drigo [

5] classified on the basis of duration of symptoms two types of BPT. In the first type, the episodes last several hours or days (“periodic torticollis”), and in the second type, the episodes last only a few minutes and are accompanied by ocular signs (“paroxysmal”). Hadjipanayis [

6] and Greene [

4] described the BPT on the basis of duration of episodes the condition “Typical” 6 days (1 min-28 days), “Shortest” 2 days (1 min-10 days), “Longest” 9 days (2 min-42 days).

The etiopathogenesis of BPT is unknown. Many different underlying disorders involving vestibular and cerebellar structures, immaturity of brain, or even a channelopathy were proposed. [

19] Surface Electromyography (EMG) recordings have observed continuous electrical discharge from the sternocleidomastoid in BPT, confirming that the torticollis is a dystonia. [

28]

BPT is considered one of the “episodic syndromes that may be associated with migraine” in the International Classification of Headache Disorders, Third Edition (ICHD-3). [

29] Current understanding of the clinical phenotype of BPT is based largely on case reports and case series. BPT often have a family history of migraine. Mutations in genes including Calcium Channel Voltage-dependent P/Q Type Alpha 1A subunit (CACNA1A), [

21] Proline-rich transmembrane protein 2 gene (PRRT2),[

18] and ATPase Na+/K+ Transporting Subunit Alpha 2 (ATP1A2) [

21] have been identified in families with BPT. Such mutations are known to cause Familial hemiplegic migraine(FHM). These genes encode ion channels or transmembrane proteins involved in cell signaling. Interestingly, mutations in these genes, are also known to cause other paroxysmal disorders, such as epilepsy, episodic ataxia, paroxysmal tonic upgaze, alternating hemiplegia(AH), and paroxysmal dyskinesia. The frequency of mutations in CACNA1A and PRRT2 in BPT is not known. In 2007, Giffin first documents in 4 cases of BPT a mutation in CACNA1A. [

18] The 4 cases subsequently developed paroxysmal vertigo(BPVC) and episodes of ataxia. The hypothesis of channelopathy [

18] suggest that cerebellar cortex where CACNA1A gene is abundantly expressed, probably contributes to the expression of BPT. In 2009, Rosman et al. [

19] reported neuromotor assessment of 10 children with BPT and 5 showed gross motor delay during the period with recurrent attacks of torticollis while the motor delay remained persistent in persistent in 4 cases with parents migraineurs. In 2016, Shin [

22] attempted to determine the frequency of CACNA1A mutations in BPT by analyzing eight children found 3 different polymorphisms of the CACNA1A gene, but no pathogenic mutation and found no mutation or familiarity for hemiplegic migraine, episodic ataxia or paroxysmal tonic upward gaze. She therefore hypothesized that CACNA1A mutations were more likely in children with BPT and a positive family history of migraine. Accordingly, other investigations are designed to elucidate the natural long-term development of BPT, the relationship of this disorder to migraine and other paroxysmal disorders, and the frequency of mutations in CACNA1A, PRRT2, ATP1A2, and Sodium Voltage-gated channel Alpha subunit 1 (SCN1A). [

21,

30] Danielsson [

21] found in one patient, a variant of unclear clinical significance in ATP1A2 (NM_000702), c.2273G>C (p.Gly758Ala). This variant has previously been described in Hemiplegic migraine. This is a female patient which had a brother with BPT and a father who suffered from migraine. In another female carried a variant of unclear clinical significance in CACNA1A (NM_023035) c.5176G>A (p.Val1726Met). Neither of these female patients had any paroxysmal diseases at the time of the second follow-up. This specific gene is responsible for encoding the main subunit of the alpha-1 pore which is the main voltage-dependent calcium channel, also involved in familial hemiplegic migraine type 1. In the cohort studied by Author, with a median follow-up of 13 years, 5 of 11 children developed migraine, abdominal migraine (AM), or cyclic vomiting (BCV). Cuenca-León [

24] have reported two novel and one previously cited non-synonymous base changes in the CACNA1A gene in a cohort of Spanish cases with different migraine variants, Hemiplegic Migraine(HM), Basilar migraine(BM) or Children Periodic Syndrome(CPS) . He screened 27 Spanish patients with hemiplegic migraine (HM), basilar-type migraine or childhood periodic syndromes (CPS) for mutations in these genes. Two novel CACNA1A variants, p.Val581Met and p.Tyr1245Cys, and a previously annotated change, p.Cys1534Ser, were identified in individuals with HM, although they have not yet been proven to be pathogenic. Interestingly, p.Tyr1245Cys was detected in a patient displaying a changing, age-specific phenotype that began as BPT evolving into benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood and later becoming HM. In another patient presenting the age-specific sequential phenotypes of BPT, BPVC and FHM a change from A to G at cDNA nucleotide 3734 in exon 22 was identified, prompting the new gene variant p.Tyr1245Cys, located at domain III, segment 1 (DIII-S1) of Cav2. Among patients who had their onset in childhood with episodes of BPV (n=4), one developed HM, one BM and two continued to display BPVC at the ages of 5 and 6 years, the latter with accompanying headache. All BPVC patients had normal Electroencephalogram (EEG) and audiometric testing; clinical screening of vestibular function in school-aged children was also normal.

The diagnosis of BPT it is mainly based on the clinic. A correct medical history and physical examination are essential to making the diagnosis. Good story and detailed description, as well as video recording [

19] and home video are essential. The diagnosis is one of exclusion and is confirmed when a pattern of stereotyped episodes is recognized

In the

Table 3 are indicated the ICHD-III diagnostic criteria.

The differential diagnosis must be made with respect to organic and neurological pathologies such as gastroesophageal reflux, idiopathic torsional dystonia, and complex partial epilepsy and all malformities conditions and space-occupying processes in the posterior cranial fossa, as well as cervical vertebral anomalies and craniovertebral junction anomalies. Neurological examination, electroencephalogram (EEG), and brain imaging tests are generally normal in patients with BPT and help in differential diagnoses. [

6,

19]. In some cases at the first presentation it may be necessary to exclude these secondary and dangerous forms quoad vitam. At the time of diagnosis, the family must be reassured that it is a benign pathology that tends to disappear spontaneously.

There is an attack therapy and a preventive one, even if the majority of children do not take drugs. [

5] Attack therapy is based on anti-inflammatory or pain-relieving drugs to improve the child's discomfort. Greene [

4] in his large study reported that 64% of his 73 patients had used drugs for the acute treatment of BPT episodes. The most used acute medications were ibuprofen (41%), acetaminophen (41%), ondansetron (12%), and diphenhydramine (10%). only a minority of patients used other medications which included caffeine (n=3) cyproheptadine (n=2), prochlorperazine (n=2), metoclopramide (n=1), lorazepam (n=1), clonidine (n=1), cannabidiol injections (n=1). 16% used preventive drugs and 50% reported benefits, the other 50% did not complete the therapeutic cycle. Another author reported 4 patients who showed a positive response to topiramate treatment. [

31]

4. Discussion

BPT represents, together with infantile colic, according to the criteria and classification of the ICHD-III, 2018, [

10] a very early manifestation of the migraine condition. However, the pathogenesis is not clear and univocal. Based on the literature consulted, a clinical spectrum of BPT can be outlined which includes at one extreme the simpler and more benign forms which have no specific evolution and at the other the forms which are accompanied by an altered motor development. These forms are often linked to genetic mutations of CACNA1A gene and PRRT2 and can evolve into hemiplegic migraine and basilar migraine with consequent alteration of the quality of life. [

18,

19] The most frequent evolution of BPT is benign paroxysmal vertigo in childhood, an evolution found by several authors. [

4,

20] This is intriguing for the pathogenetic interpretation of BPT. BPT and BPVC are vestibular disorders to be considered of migraine origin, although they present very differently and typically occur in distinct age groups. It is unclear whether these disorders are caused by the same pathophysiological process with different symptoms at different ages or whether these are entirely distinct entities. Brodsky [

20] described a number of patients in his study population showing progression from BPT to BPVC and from BPVC to VM. A phenomenon which has been termed “vestibular march”, like the term “atopic march”, term used in pediatric allergology. The peripheral origin of BPT is also suggested by the anomalous response to the rotary chair test found by some authors as in VM and BPVC. [

2,

5] It is possible that BPT progressing to BPVC may have a more peripheral vestibular pathophysiological pattern compared to cases of isolated BPT or BPVC without progression, which may be more migraineurs in origin. Snyder [

2] suggested in the first BPT observation that the cause is peripheral vestibular dysfunction such as paroxysmal vertigo in childhood. This was supported by the fact that the attacks in four of his 12 patients evolved into benign paroxysmal vertigo (BPVC)when the children got older. The sternocleidomastoid dystonia demonstrated by Kimura [

28] can be considered an atypical and prolonged motor aura (when it persists for more than 1 hour). This may occur earlier (with or without the other migraine symptoms such as vomiting and paleness) in the same individual and in the same way that typical migraine aura can occur. Mutations in the α12.1 subunit of the CACNA1A gene have been found in more than half of families with FHM, including all those with cerebellar features. [

18] The cerebellar cortex, where the gene is abundantly expressed, likely contributes to the expression of dystonic episodes. BPT in childhood is a benign and self-limiting disorder, not always free from developmental clinical phenomena. It constitutes an important cause of paroxysmal movement disorder or dyskinesia in childhood. Child neurologists are well trained to distinguish between these benign events and serious neurologic causes. In the description of BPT which is the first manifestation of a migraine condition together with infantile colic, the concept is reiterated that primary headaches are age employees. On the other hand, the phenotypic spectrum of mutations in the CACNA1A gene has been associated with three neurological phenotypes: familial and sporadic hemiplegic migraine type 1, episodic ataxia type 2, and spinocerebellar ataxia type 6.21. Vestibular instability, probably due to an altered calcium ion channel expressed primarily in the inner ear and brain, could lead to reversible depolarization of hair cells, resulting in otoneurologic symptoms found in both migraine and periodic syndromes. [

32] The coexistence of typical migraine syndromes has rarely occurred in children with one of the two subtypes of younger onset, namely benign paroxysmal torticollis and benign paroxysmal vertigo. [

13] Furthermore, structural changes have been demonstrated in the brains of children and adolescents with migraine. In this neuroimaging study the Authors demonstrated that, compared to control subjects, young patients with migraine have decreased gyrification index in the nociceptive pathway and cognitive evaluation of pain. Cortical thickness density decreased in patients older than 12 years, compared to younger one patient. [

33]