Submitted:

08 April 2024

Posted:

09 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Overview

2.2. Data Sources

2.2.1. Landsat Surface Reflectance Data

2.2.2. Soil Data

2.2.3. DEM (Digital Elevation Model) Data

2.2.4. Existing Land Cover Products

2.2.5. Meteorological Data

2.2.6. Atmospheric-Ocean Circulation Indices Data

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Construction of Annual Long-Term Wetland Ecosystem Dataset

2.3.2. Subdivision of Land Cover Remote Sensing Classification System

2.3.3. Preprocessing of Landsat Satellite Images

2.3.4. Generation of Training and Validation Sample Sets

2.3.5. Classification and Image Post-Processing

2.3.6. Land Cover Mapping Accuracy Assessment

2.3.7. The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI)

2.3.8. Breakpoint Detection for Separating Trend and Seasonal Components (BFAST)

2.3.9. Cross-Wavelet Transform (CWT)

3. Results

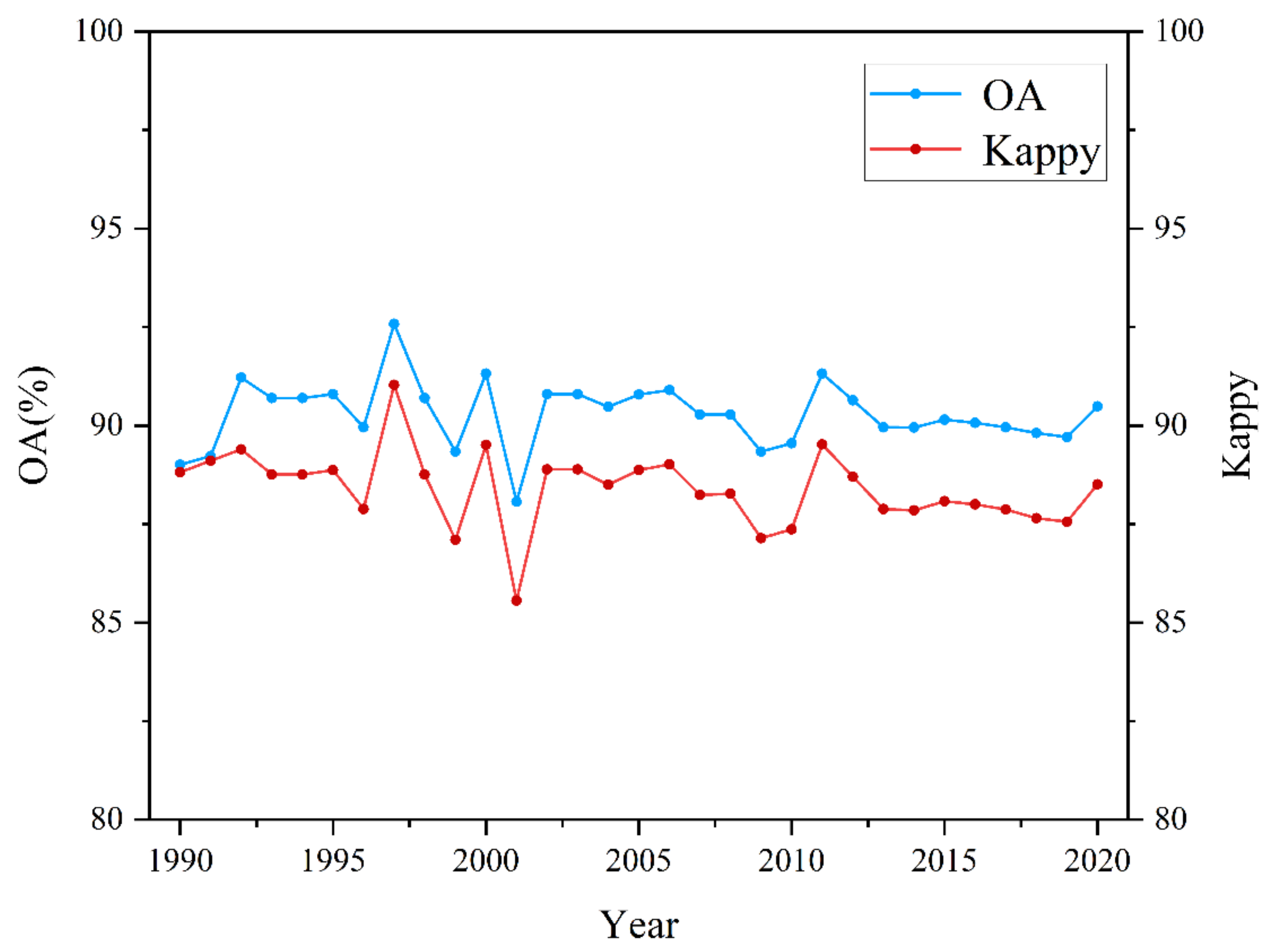

3.1. Accuracy of Wetland Extraction and Classification

3.2. Spatial and Temporal Analysis of Wetland Changes in Chaidamu Basin

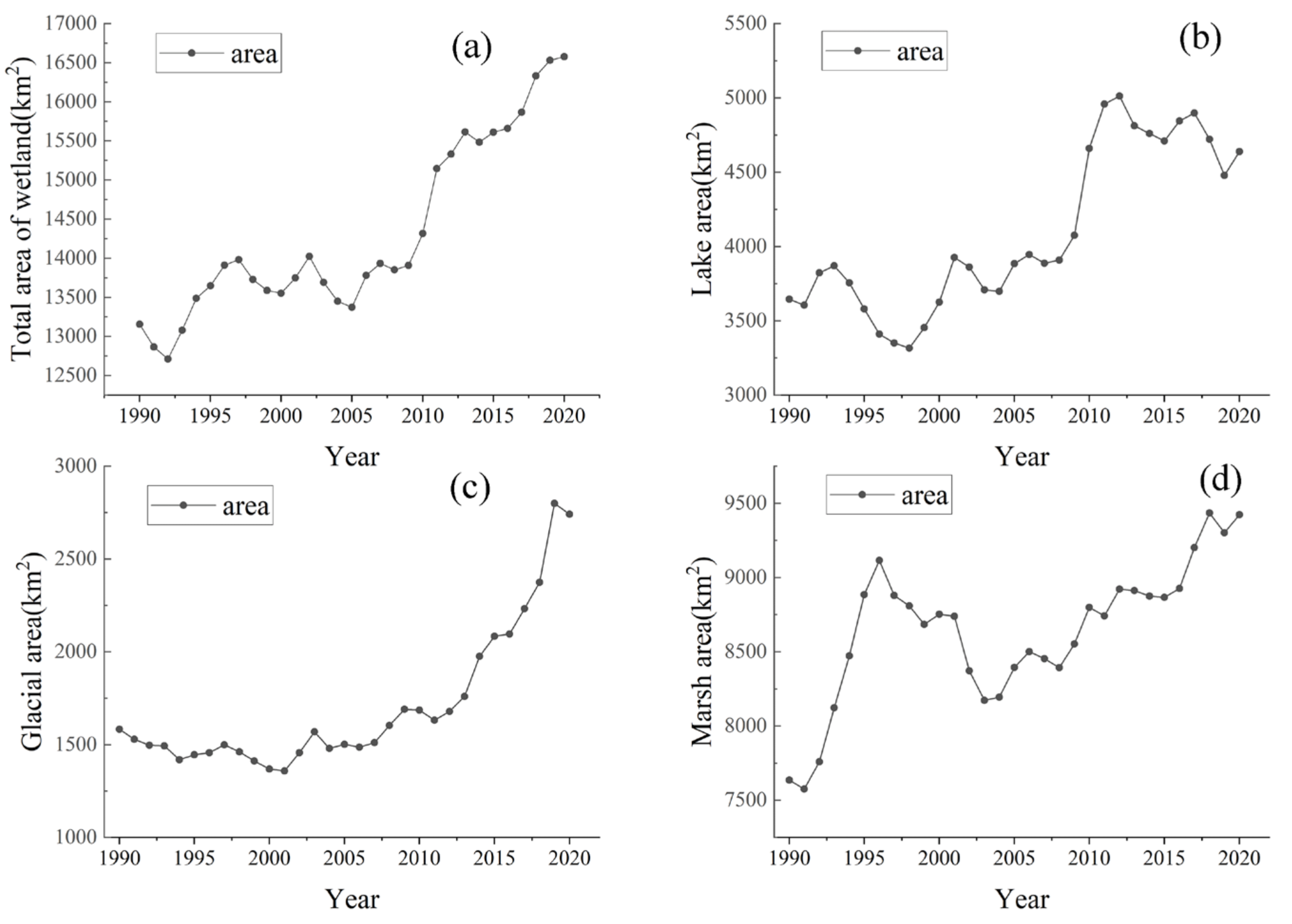

3.2.1. Analysis of Wetland Area Changes

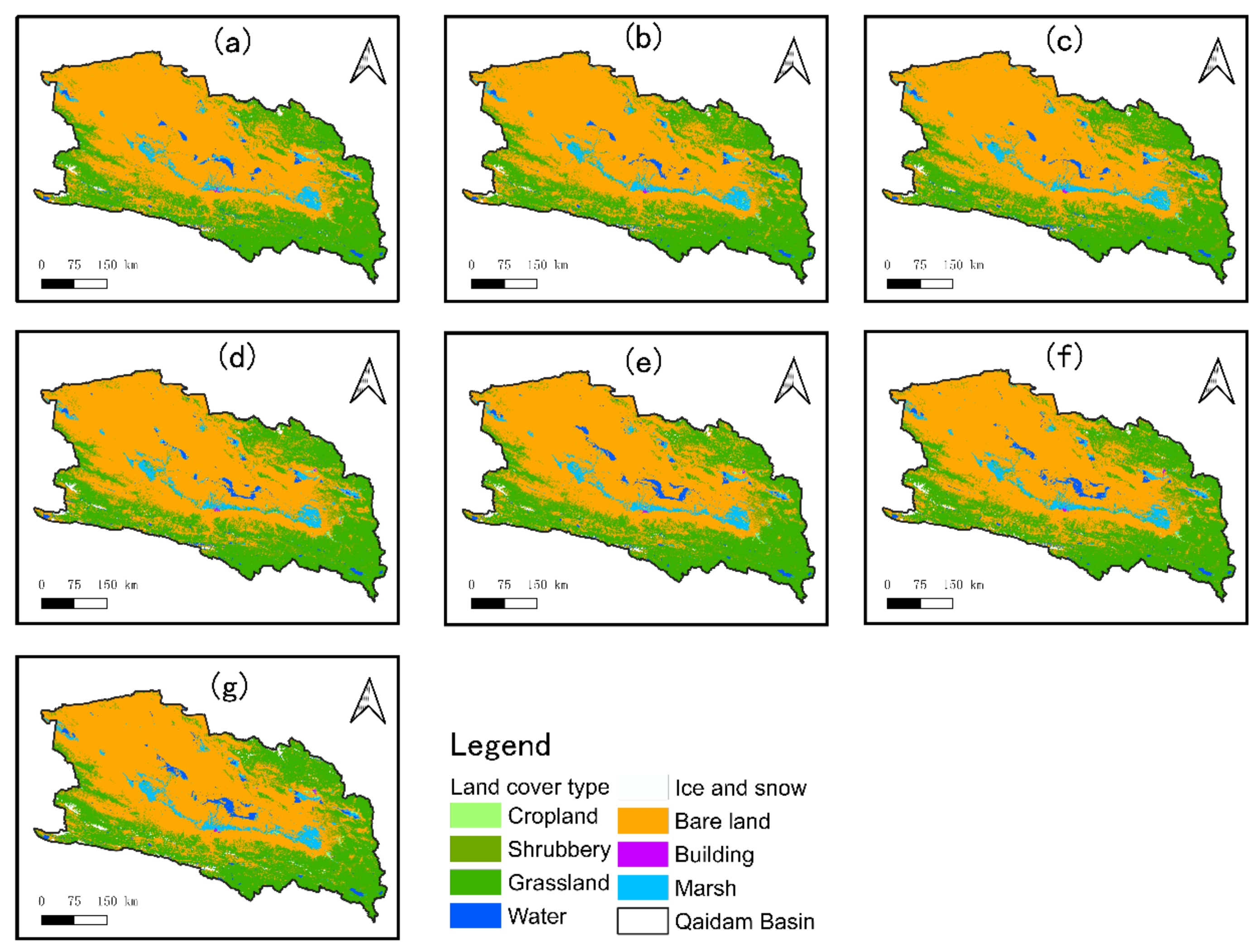

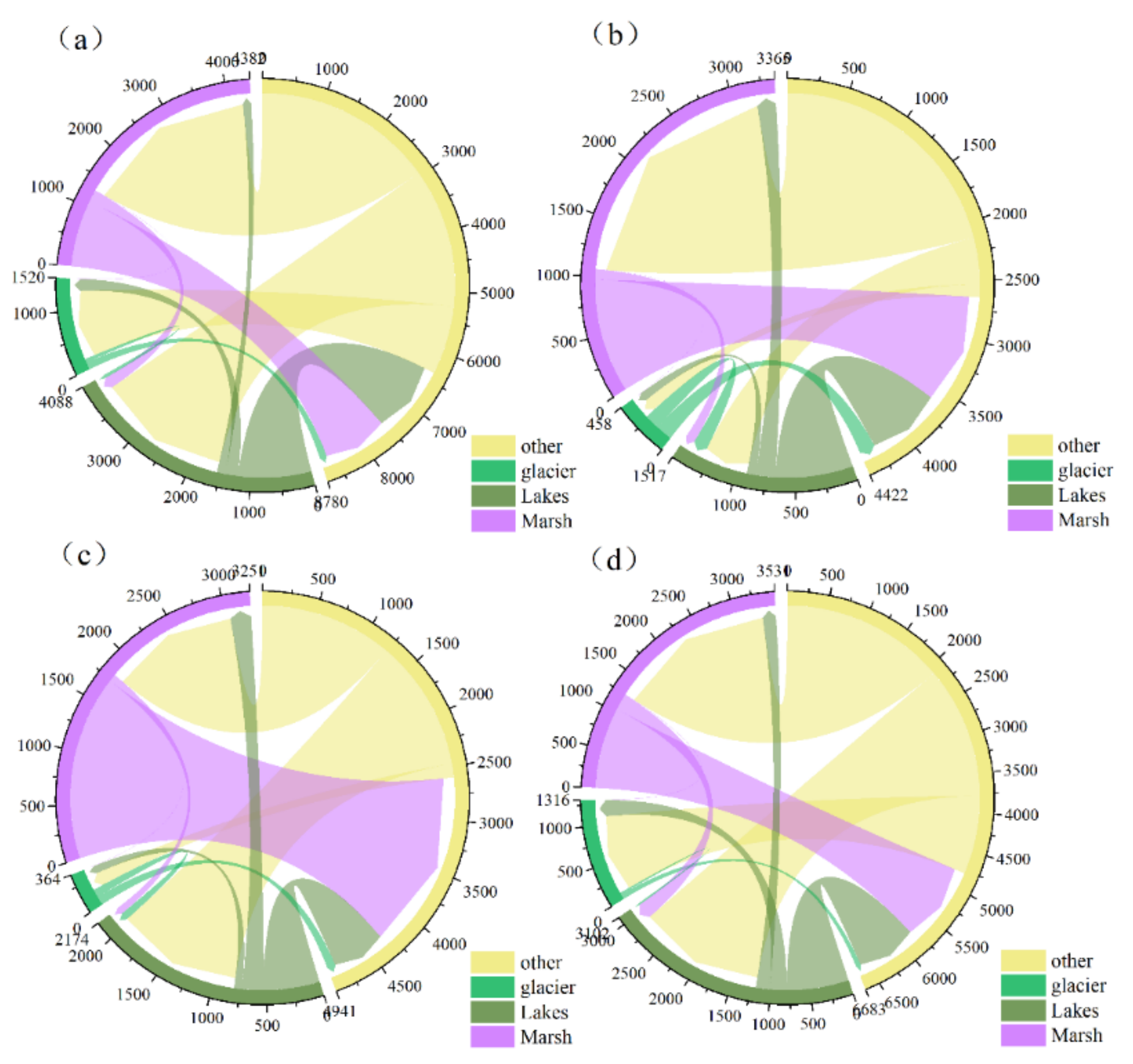

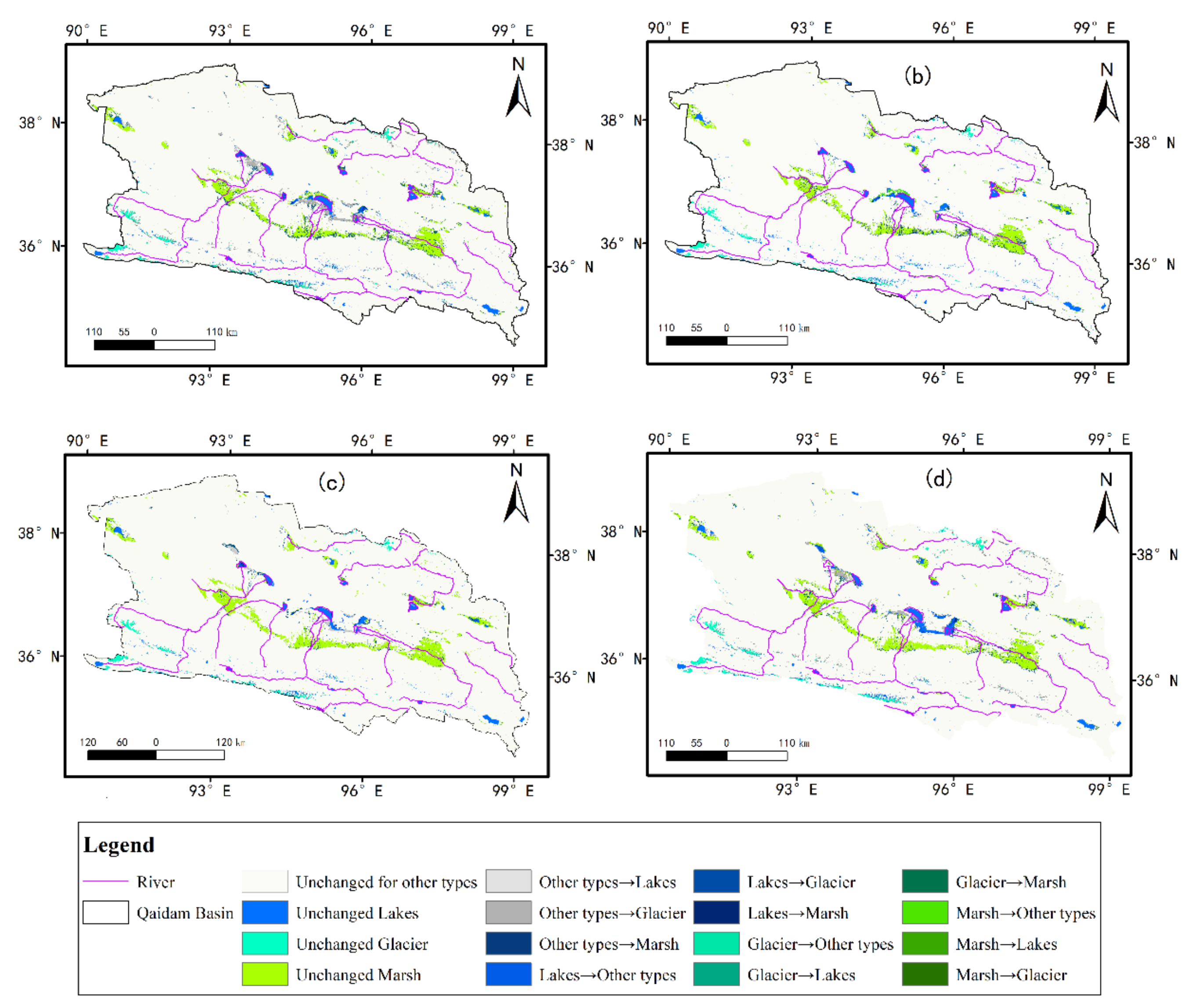

3.2.2. Analysis of Spatial Changes in Wetland Area

3.2.3. Analysis of SPEI Change and Trend

3.2.4. Effects of SPEI on Wetland Dynamics

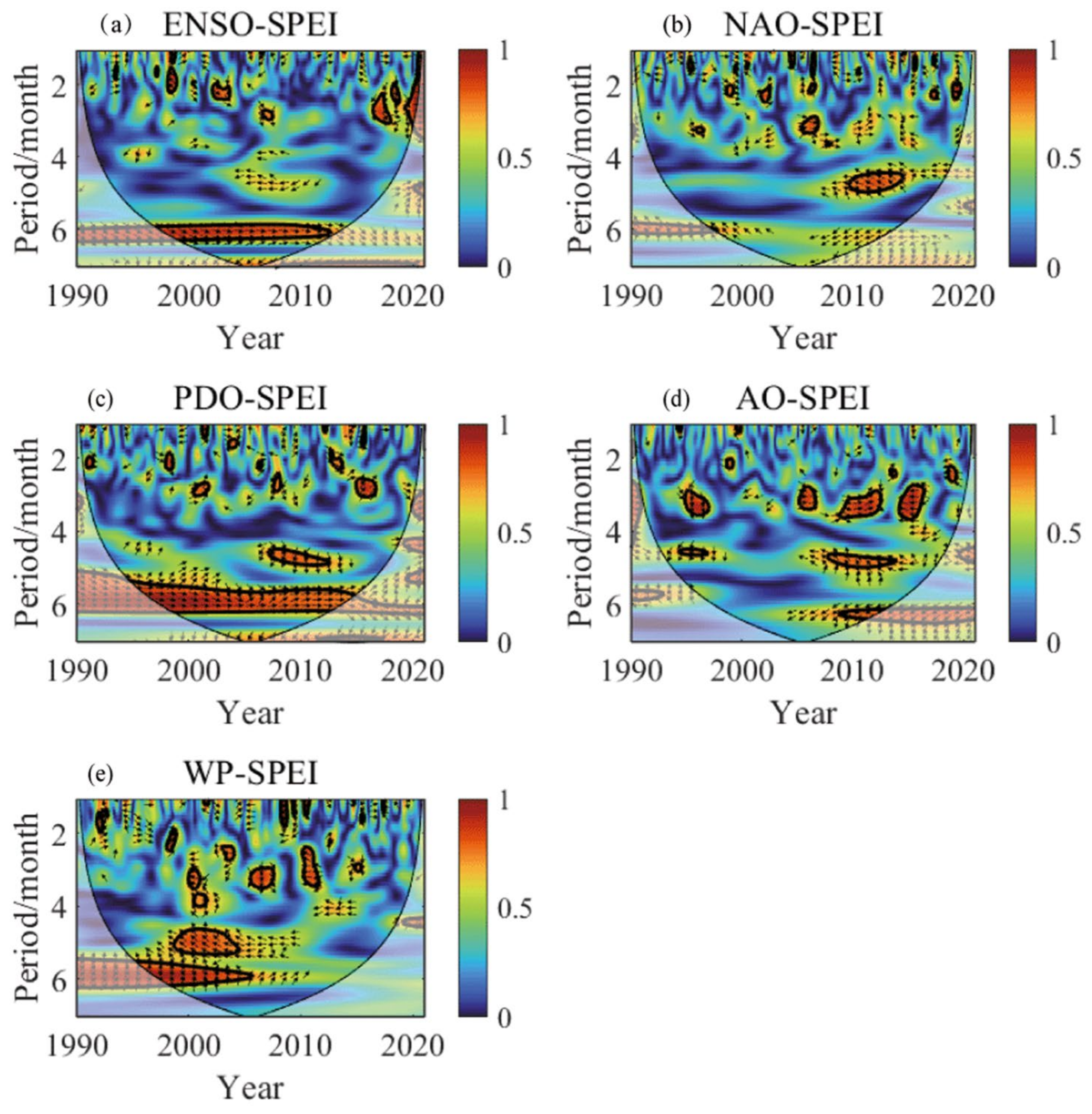

3.2.5. Response of SPEI12 to Atmospheric Circulation

4. Discussion

4.1. Land Cover Classification Results

4.2. SPEI Trend and Its Impact on Wetlands Ecosystems

4.3. Atmospheric Circulation Modes Effects on of the SPEI

5. Conclusion

- (1)

- The annual long-term land cover dataset of the Chaidamu Basin from 1990 to 2020 is categorized into the following land cover types and areas: cultivated land (516 km2, 0.2%), shrubland (13, 563 km2, 6%), grassland (74, 982 km2, 31%), water bodies (4, 052 km2, 2%), ice and snow (1, 746 km2, 0.7‰), marsh wetland (8, 641 km2, 4%), bare land (135, 080 km2, 56%), and built-up land (123 km2, 0.05%). The classification accuracy is represented by Overall Accuracy (OA) of 90.27% and Kappa (K) of 88.34%, meeting the requirements for studying wetland changes in relation to climate changes.

- (2)

- The wetland areas in the Chaidamu Basin, including total wetland area, lake wetland area, glacier wetland area, and marsh wetland area, exhibit a clear increasing trend from 1990 to 2020. There are four periods of change: Growth Period I (1990–1997), Oscillation Period (1998–2007), Growth Period II (2008–2020), during which mutual conversions between different wetland types and between non-wetland types and wetlands are substantial. The largest area of conversions is observed from non-wetland types to wetlands. Spatially, lake wetlands and marsh wetlands are distributed in the lower latitude central basin area, while glacier wetlands are found at higher altitudes in the Kunlun Mountains and Qilian Mountains.

- (3)

- SPEI at 3-month, 6-month, 9-month, and 12-month scales are all significantly negatively correlated (p < 0.5) with both total wetland area and wetland areas of different types. The lagging effect of SPEI12 on wetlands is the strongest (between September and December), with a correlation coefficient of <−0.75. Analyzing the trend of SPEI12 from 1990 to 2020, a significant decreasing trend (p < 0.5) is observed overall. However, the time series exhibits noticeable non-stationary characteristics, with three breakpoints occurring in June 1996, May 2002, and April 2011. This trend suggests that drought severity intensified during these periods.

- (4)

- The atmospheric circulation indices (ENSO, NAO, PDO, AO, WP) exhibit varying degrees of resonance with SPEI12. NAO, PDO, AO, and WP show longer resonance times, and their responses to SPEI12 are more pronounced.

- (5)

- This study presents recommended measures to address the ecological and environmental issues in the Chaidamu Basin. These measures encompass aspects such as public education, scientific research, monitoring, and water conservation promotion. It is anticipated that these measures will offer valuable insights for achieving regional sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alsafadi, K.; Bi, S.; Bashir, B.; Mohammed, S.; Sammen, S.S.; Alsalman, A.; Kenawy, A. Assessment of carbon productivity trends and their resilience to drought disturbances in the middle east based on multi-decadal space-based datasets. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 6237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson-D.; Valérie; Panmao, Z.; Anna, P.; Sarah, L.; Connors; Clotilde, P.; Sophie, B.; Nada, C. Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change 2, 2021, 1, 2391.

- Quan, Q.; Tian, D.S.; Luo, Y.Q.; Zhang, F.Y.; Tom, W. C.; Zhu, kai.; Chen, Y.H.; Zhou, Q.P.; Niu, S.L. Water scaling of ecosystem carbon cycle feedback to climate warming. Science Advances 2019, 8, 1131.

- Nielsen, D.L.; Kiya, P.; Watts, R.J.; Wilson, A.L. Empirical evidence linking increased hydrologic stability with decreased biotic diversity within wetlands. Hydrobiologia 2013, 708, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R., Shukla, S.K., Parmar, K. Wetlands Conservation and Restoration for Ecosystem Services and Halt Biodiversity Loss: An Indian Perspective. 2020, 75–85.

- Zhang, Y.H.; Yan, J.Z.; Cheng, X. Research progress on impacts of climate change and human activities on wetlands on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2023, 43, 2180–2193. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, R.J. Coastal flooding and wetland loss in the 21st century: Changes under the SRES climate and socio-economic scenarios. Global Environmental Change 2004, 14, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, N.C. How much wetland has the world lost? Long-term and recent trends in global wetland area. Marine and Freshwater Research 2014, 65, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.F.; Wu, H.; Liu, Y.H. Research status and prospect of wetland remote sensing mapping. Bulletin of National Natural Science Foundation of China 2022, 36, 420–431. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, D.; Zongming, W.; Baojia, D.; Lin, Li, Y.T.; Mingming, J.; Yuan, Z.; Kaishan, S.; Ming, J.; Yeqiao, W. National wetland mapping in China: A new product resulting from object-based and hierarchical classification of Landsat 8 OLI images. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 2020; 164, 11–25.

- Gong, P.; Niu, Z.G.; Cheng, X. China’s wetland change (1990–2000) determined by remote sensing. Scientia Sinica 2010, 40, 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.C.; Li, B.J.; Liu, X.P. Global annual land cover map at 30 m resolution from 2000 to 2015. National Remote Sensing Bulletin 2021, 25, 1896–1916. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Liao, A. Global land cover mapping at 30m resolution: A POK-based operational approach. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2015, 103, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Y.; Hu, F. GlobeLand30 land cover products are used for refined wind energy resource assessment. Resources Science 2017, 39, 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Chen, X. GLC_FCS30: Global land-cover product with fine classification system at 30 m using time-series Landsat imagery. Earth System Science Data 2021, 13, 2753–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Niu, X. Myanmar’s Land Cover Change and Its Driving Factors during 2000–2020. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousivand, A.; Arsanjani, J.J. Insights on the historical and emerging global land cover changes: The case of ESA-CCI-LC datasets. Applied Geography 2019, 106, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, V.; Hoffmann, P.; Rechid, D.; Böhner, J.; Bechtel, B. High-resolution land use and land cover dataset for regional climate modelling: A plant functional type map for Europe 2015. Earth System Science Data 2022, 4, 1735–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Huang, X. The 30 m annual land cover dataset and its dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. Earth System Science Data 2021, 13, 3907–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Ding, X.; Su, J.; Mu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, P.; Zhao, G. Land use and cover changes on the Loess Plateau: A comparison of six global or national land use and cover datasets. Land Use Policy 2022, 119, 106165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.J.; Shang, Z.Y.; Zhang, J. Standardized Establishment and Improvement of Accounting System of Agriculture Greenhouse Gas Emission. Scientia Agricultura Sinica. 2023, 56, 4467–4477. [Google Scholar]

- Alsafadi, K.; Bashir, B.; Mohammed, S.; Abdo, H.G.; Mokhtar, A.; Alsalman, A.; Cao, W. Response of Ecosystem Carbon–Water Fluxes to Extreme Drought in West Asia. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.J.; Ren, F.M.; Li, Y.P. Characteristics of regional meteorological drought events in Southwest China from 1960 to 2010. Acta Meteorologica Sinica 2014, 72, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.F.; Tang, W.J.; Li, S.L. Discussion on identification of drought-prone areas in southwest China. China Water Resources 2012, (05), 18–21+39.

- Wang, D.; Zhang, B.; An, M.L. Spatiotemporal characteristics of drought in Southwest China during the last 53 years based on SPEI. Journal of Natural Resources 2014, 29, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.J.; Ding, J.L.; Zhang, Y.Y. Response of vegetation cover to drought on the north slope of Tianshan Mountains from 2001 to 2015: Based on land use/land cover analysis. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2019, 39, 6206–6217. [Google Scholar]

- Mokhtar, A.; He, H.; Alsafadi, K. Evapotranspiration as a response to climate variability and ecosystem changes in southwest, China. Environ Earth Sci 2020, 79, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.I.; Sun, H.W.; Wang, J.P. Improvement of comprehensive meteorological drought index and its applicability analysis. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering 2020, 36, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Sobral, B.S.; De, O.J.F.; De, G.G. Drought characterization for the state of Rio de Janeiro based on the annual SPI index: Trends, statistical tests and its relation with ENSO. Atmospheric research 2019, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, H.R.; Wilhite, D.A. Objective Quantification of Drought Severity and Duration. Journal of Climate 1999, 12, 2747–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Ren, L. A New Physically Based Self-Calibrating Palmer Drought Severity Index and its Performance Evaluation. Water Resources Management 2015, 29, 4833–4847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Li, M.X.; Zheng, Y.Z. Regional adaptability of 7 meteorological drought indices in China. Scientia Sinica(Terrae) 2017, 47, 337–353. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, D.L.; Cheng, Z.G.; Zhao, L. Applicability analysis of four drought discrimination indexes in Northeast China. Arid Land Geography 2020, 43, 371–379. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; She, D.; Zheng, H. Elucidating Diverse Drought Characteristics from Two Meteorological Drought Indices (SPI and SPEI) in China. Journal of Hydrometeorology 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.J.; Wang, S.G.; Li, C.Y. Applicability analysis of three drought indices in southwest China. Plateau Meteorolog 2014, 33, 686–697. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Sun, J. Changes in Drought Characteristics over China Using the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. Journal of Climate 2015, 28, 5430–5447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Guo, B.; Zhang, Y. The sensitivity of the SPEI to potential evapotranspiration and precipitation at multiple timescales on the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain, China. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 2020, 143(1–2), 87–99.

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L. Recent changes in wetlands on the Tibetan Plateau: A review. J. Geogr. Sci. 2015, 25, 879–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Mao, D.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, C. Monitoring 40-Year Lake Area Changes of the Qaidam Basin, Tibetan Plateau, Using Landsat Time Series. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Liu, B.; Jiang, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Lu, X. Spatiotemporal change of marsh vegetation and its response to climate change in China from 2000 to 2019. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 2021, 126, e2020JG006154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Zhang, L.; He, Y. Effects and contributions of meteorological drought on agricultural drought under different climatic zones and vegetation types in Northwest China. Sci Total Environ 2022, 821, 153270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M.; Mo, X.; Liu, S.; Hu, S. Detection and attribution of lake water loss in the semi-arid Mongolian Plateau—A case study in the Lake Dalinor. Ecohydrology 2021, 14, e2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, X. Climate changes in the Qaidam Basin in NW China over the past 40 kyr. Palaeogeography, palaeoclimatology, palaeoecology 2020, 551, 109679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, C.; Feng, Y.; Hu, C.; Zhong, S.; Yang, J. Cenozoic sediment flux in the Qaidam Basin, northern Tibetan Plateau, and implications with regional tectonics and climate. Global and Planetary Change 2017, 155, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.M.; Li, Y.Q.; Zhou, C.Y. Climate change characteristics and causes of water vapor budget over the Tibetan Plateau during 1979–2016. Journal of Glaciology and Geocryology 2023, 45, 846–864. [Google Scholar]

- Rohrmann, A.; Heermance, R.; Kapp, P.; Cai, F. Wind as the primary driver of erosion in the Qaidam Basin, China. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2013, 374, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurskainen, P.; Adhikari, H.; Siljander, M.; Pellikka, P.K.E.; Hemp, A. Auxiliary datasets improve accuracy of object-based land use/land cover classification in heterogeneous savanna landscapes. Remote sensing of environment 2019, 233, 111354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Chen, X.; Gao, Y.; Xie, S.; Mi, J. GLC_FCS30: Global land-cover product with fine classification system at 30 m using time-series Landsat imagery. Earth System Science Data 2021, 13, 2753–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Liu, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, C.; Wang, J.; Huang, H.; Clinton, N. Stable Classification with Limited Sample: Transferring a 30-m Resolution Sample Set Collected in 2015 to Mapping 10-m Resolution Global Land Cover in 2017. Science Bulletin 2019, 64, 370–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.Y.; Xin, L.J. Temporal and spatial changes of cultivated land and grain production in China based on GlobeLand30 data. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering 2017, 33, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Bi, S.; Bashir, B.; Ge, Z.; Wu, K.; Alsalman, A.; Ayugi, B.O.; Alsafadi, K. Historical Trends and Characteristics of Meteorological Drought Based on Standardized Precipitation Index and Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index over the Past 70 Years in China(1951–2020). Sustainability 2023, 15, 10875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, I.; Osborn, T.J.; Jones, P.; Lister, D. Version 4 of the CRU TS Monthly High-Resolution Gridded Multivariate Climate Dataset. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnston, A.G., M. Chelliah, and S. B. Goldenberg, 1997: Documentation of highly ENSO-related SST region in the equatorial Pacific. Atmos.–Ocean, 35, 367–383.

- Hurrell, J.W. Decadal trends in the North Atlantic Oscillation: Regional temperatures and precipitation. Science 1995, 269, 676–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantua, N.J.; Hare, S.R.; Zhang, Y.; Wallace, J.M.; Francis, R.C. A Pacific interdecadal climate oscillation with impacts on salmon production. Bulletin of the american Meteorological Society 1997, 78, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.W.; Wallace, J.M.; Hegerl, G.C. Annular modes in the extratropical circulation. Part II: Trends. Journal of climate 2000, 13, 1018–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnston, A.G.; Livezey, R.E. Classification, seasonality and persistence of low-frequency atmospheric circulation patterns. Monthly weather review 1987, 115, 1083–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizizadeh, B.; Omarzadeh, D.; Kazemi Garajeh, M.; Lakes, T.; Blaschke, T. Machine learning data-driven approaches for land use/cover mapping and trend analysis using Google Earth Engine. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2023, 66, 665–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, V.; Deljouei, A.; Moradi, F.; Sadeghi, S.M.M.; Borz, S.A. Land Use and Land Cover Mapping Using Sentinel-2, Landsat-8 Satellite Images, and Google Earth Engine: A Comparison of Two Composition Methods. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Liu, J.; Kuang, W. Spatiotemporal patterns and characteristics of land-use change in China during 2010–2015. Journal of Geographical Sciences 2018, 28, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian-li; D. I. N. G.; Xiang-yu, G.E.; Jing-zhe; W. A. N. G. Ebinur Lake wetland identification and its spatio-temporal dynamic changes. Journal of natural resources 2021, 36, 1949–1963. [CrossRef]

- Appj, Brhw, Bvat. Cloud detection algorithm using SVM with SWIR2 and tasseled cap applied to Landsat 8. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 82, 101898.

- Brooks, E.B.; Thomas, V.A.; Wynne, R.H. Fitting the Multitemporal Curve: A Fourier Series Approach to the Missing Data Problem in Remote Sensing Analysis. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience & Remote Sensing 2012, 50, 3340–3353. [Google Scholar]

- Irish, R.R.; Barker, J.L.; Goward, S.N. Characterization of the Landsat-7 ETM+ Automated Cloud-Cover Assessment (ACCA) Algorithm. Photogrammetric Engineering & Remote Sensing, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Woodcock, C.E. Object-based cloud and cloud shadow detection in Landsat imagery. Remote Sensing of Environment 2012, 118, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; He, B.; Zhu, Z. Improving Fmask cloud and cloud shadow detection in mountainous area for Landsats 4–8 images. Remote Sensing of Environment 2017, 199, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foody, G.M.; Mathur, A. Toward intelligent training of supervised image classifications: Directing training data acquisition for SVM classification. Remote Sensing of Environment 2004, 93, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Chen, X. GLC_FCS30: Global land-cover product with fine classification system at 30 m using time-series Landsat imagery. 2020.

- Huang, Y.B.; Liao, S.B. Automatic extraction of land cover samples from multi-source data. National Remote Sensing Bulletin 2017, 21, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbesselt, J.; Zeileis, A.; Herold, M. Near real-time disturbance detection using satellite image time series. Remote Sensing of Environment 2012, 123, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Woodcock, C.E. Continuous Change Detection and Classification of Land Cover Using All Available Landsat Data. Remote Sensing of Environment 2013, 144, 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.E.; Yang, Z.; Cohen, W.B. Detecting trends in forest disturbance and recovery using yearly Landsat time series: 1. LandTrendr — Temporal segmentation algorithms [J]. Remote Sensing of Environment 2010, 114, 2897–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneibel, A.; Stellmes, M.; Röder, A. Assessment of spatio-temporal changes of smallholder cultivation patterns in the Angolan Miombo belt using segmentation of Landsat time series. Remote Sensing of Environment 2017, 195, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Galiano, V.F.; Ghimire, B., Rogan; Chica-Olmo, M.; Rigol-Sanchez, J.P. An assessment of the effectiveness of a random forest classifier for land-cover classification. ISPRS journal of photogrammetry and remote sensing 2012, 67, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.Q.; Shen, R.Q.; Wang, Jun. Land use change detection in Henan Province supported by GEE remote sensing cloud platform. Journal of Geomatics Science and Technology 2021, 38, 287–294.

- Zhang, M.; Li, G.; He, T. Reveal the severe spatial and temporal patterns of abandoned cropland in China over the past 30 years. Sci Total Environ 2023, 857, 159591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Beguería, S.; López-Moreno, J.I. A Multiscalar Drought Index Sensitive to Global Warming: The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 1696–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Response of Ecosystem Carbon–Water Fluxes to Extreme Drought in West Asia. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 1179.

- Alsafadi, K.; Al-Ansari, N.; Mokhtar, A.; Mohammed, S.; Elbeltagi, A.; Sh Sammen, S.; Bi, S. An evapotranspiration deficit-based drought index to detect variability of terrestrial carbon productivity in the Middle East. Environmental Research Letters 2022, 17, 014051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsafadi, K.; Mohammed, S.A.; Ayugi, B.; Sharaf, M.; Harsányi, E. Spatial–temporal evolution of drought characteristics over Hungary between 1961 and 2010. Pure and Applied Geophysics 2020, 177, 3961–3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, A.; Jalali, M.; He, H.; Al-Ansari, N.; Elbeltagi, A.; Alsafadi, K.; Abdo, H.G.; Sammen, S.S.; Gyasi-Agyei, Y.; Rodri-go-Comino, J. Estimation of SPEI Meteorological Drought Using Machine Learning Algorithms. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 65503–65523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.I.; Sinclair, C.D.; Werritty, A. Log-logistic flood frequency analysis. J. Hydrol 1988, 98, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbesselt, J.; Hyndman, R.; Zeileis, A.; Culvenor, D. Phenological change detection while accounting for abrupt and gradual trends in satellite image time series. Remote Sensing of Environment 2010, 114, 2970–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbesselt, J.; Hyndman, R.; Newnham, G.; Culvenor, D. Detecting trend and seasonal changes in satellite image time series. Remote Sensing of Environment 2010, 114, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbesselt, J.; Zeileis, A.; Herold, M. Near real-time disturbance detection using satellite image time series. Remote Sensing of Environment 2012, 123, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazelles, B.; Chavez, M.; Berteaux, D.; Ménard, F.; Vik, J.O.; Jenouvrier, S.; Stenseth, N.C. Wavelet analysis of ecological time series. Oecologia 2008, 156, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Li, X.Q.; Liu, L.X. Evolution analysis of ice and snow lakes in Qaidam Basin based on remote sensing and GIS. Yangtze River 2015, 46, 64–66+91. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Yao, X.J.; Xiao, J.S. Evolution of glaciers and lakes in Qinghai Province from 2000 to 2020. Journal of Natural Resources 2023, 38, 822–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.S.; Shao, Z.J.; Cao, G.C. Impact assessment of climate change on glacier resources in Qinghai Plateau. Journal of Arid Land Resources and Environmen 2005, (05), 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.S. Recent glacier retreat, climate change and sea level rise. Advances in Earth Science 1989, (03), 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, D.H. Glaciers and ecological environment on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau; China Tibetology Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Z.; Liu, Z.X.; Wang, Wendi. Response and trend prediction of glaciers on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau to climate change. Advances in Earth Science 1999, (06), 607–612.

- Du, Y.; Liu, B.K.; He, W.G. Changes of lake area and its causes in Qaidam Basin from 1976 to 2017. Journal of Glaciology and Geocryology 2018, 40, 1275–1284. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Gao, L.; Coscarelli, R. Drought and Wetness Variability and the Respective Contribution of Temperature and Precipitation in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Advances in Meteorology 2021, 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.J.; Yang, M.X.; Liang, X.W. The dramatic climate warming in the Qaidam Basin, northeastern Tibetan Plateau, during 1961–2010. International Journal Of Climatology 2014, 34, 1524–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.W.; Wang, N.L.; Chen, A.A. Impacts of Climate Change, Glacier Mass Loss and Human Activities on Spatiotemporal Variations in Terrestrial Water Storage of the Qaidam Basin, China. Remote Sensing 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.J.; Chen, Y.N.; Pan, Y.P. Assessment of candidate distributions for SPI/SPEI and sensitivity of drought to climatic variables in China. International Journal of Climatology 2019, 39, 4392–4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ding, M.; Li, L. Continuous Wetting on the Tibetan Plateau during 1970–2017. Water 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Lv, A.H.; Zhang, W.X. Temporal and spatial characteristics of drought in Qinghai Province and its response to atmospheric circulation. Journal of Arid Land Resources and Environment 2021, 35, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.Y.; Xiao, Y.; Ou-yang, Z.Y. Assessment of ecological importance of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau based on ecosystem service flows. Journal Of Mountain Science 2021, 18, 1725–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, D.L.; Guan, Z.Y.; Xu, J.Y. Prediction models for summertime Western Pacific Subtropical High based on the leading SSTA modes in the tropical Indo-Pacific sector. Transactions of Atmospheric Sciences 2021, 44, 405–417. [Google Scholar]

- Rapid expansion of wetlands on the Central Tibetan Plateau by global.

- Lv, C.Y.; Liu, M.X.; Li, Y. Characteristics of summer extreme heavy precipitation in the Qaidam Basin and causes of atmospheric circulation. Journal of Lanzhou University(Natural Sciences) 2021, 57, 252–262. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.S.; Zhou, S.W.; Wu, P. Response of winter precipitation in eastern Tibetan Plateau to Arctic Oscillation. Acta Meteorologica Sinica 2021, 79, 558–569. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, C.X. Effect of North Atlantic Oscillation on water vapor transport over the Tibetan Plateau in winter. Journal of Meteorological Research and Application 2023, 44, 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Wang., B.F.; Xin, M.Y. Atmospheric Circulation Analysis of Persistent Drought in Eastern Part of Northwest China. Journal of Anhui Agricultural Sciences. 2017, 45, 196–198. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).