1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, has led to a significant increase in global morbidity and mortality [

1]. Additionally, a subset of infected patients experience persistent symptoms that may last for at least three months following the infection, referred to as post COVID-19 condition by the World Health Organization (WHO) [

2]. Although the prevalence of post COVID-19 condition is yet to be determined [

3], the WHO estimates that around 10% of people might suffer from this condition following COVID-19 infection [

4].

Post COVID-19 conditions can occur after COVID-19 of varying severity and present a range of persistent symptoms, with fatigue, dyspnea and cognitive problems being the most common [

1,

3]. These enduring symptoms can hamper daily activities, limit physical activity, lead to psychological symptoms, cognitive dysfunction, and subsequently impact quality of life [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Currently, there is no standardized clinical assessment for measuring the impact of post COVID-19 on an individual's everyday life [

9].

The EQ-5D-5L is a widely used and concise tool for assessing generic health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [

10]. It consists of self-assessment questions that cover five health dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and depression/anxiety. Each dimension offers five possible response options, ranging from ‘no problems’ to ‘extreme problems’ [

11]. The EQ-5D-5L has found extensive use in cost utility analysis aiding policy-makers in healthcare resource allocation [

12]. Recently, it has been applied in studies examining the outcomes of post COVID-19 patients [

13,

14]. However, concerns have been raised about its brevity limiting its ability to measure the long term consequences of, for example infectious diseases such as COVID-19 [

15]. A previous study on patients with persistent symptoms following another infectious disease, Q-fever, revealed that EQ-5D-5L was able to capture fatigue and cognitive problems related to that condition [

16]. To date, no studies have explored whether EQ-5D-5L dimensions and the EQ visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS) can adequately capture significant symptoms in post COVID-19 condition. This exploratory study aimed to investigate whether EQ-5D-5L dimensions capture the most common persistent symptoms such as fatigue, memory/concentration problems and dyspnea in patients with post COVID-19 condition and whether adding these symptoms improves the explained variance of HRQoL.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Study Design and Cohorts

This study is a component of the longitudinal project at the Uppsala University Hospital, known as “COMBAT post Covid”, which investigates the long-term consequences of COVID-19 [

17,

18,

19,

20]. This exploratory cross-sectional study comprised two cohorts of adults (age 18 years and older) who had a history of COVID-19 between 2020-2022; “Hospitalized COVID” and “Post COVID outpatients”. Data included in this study was gathered through a questionnaire.

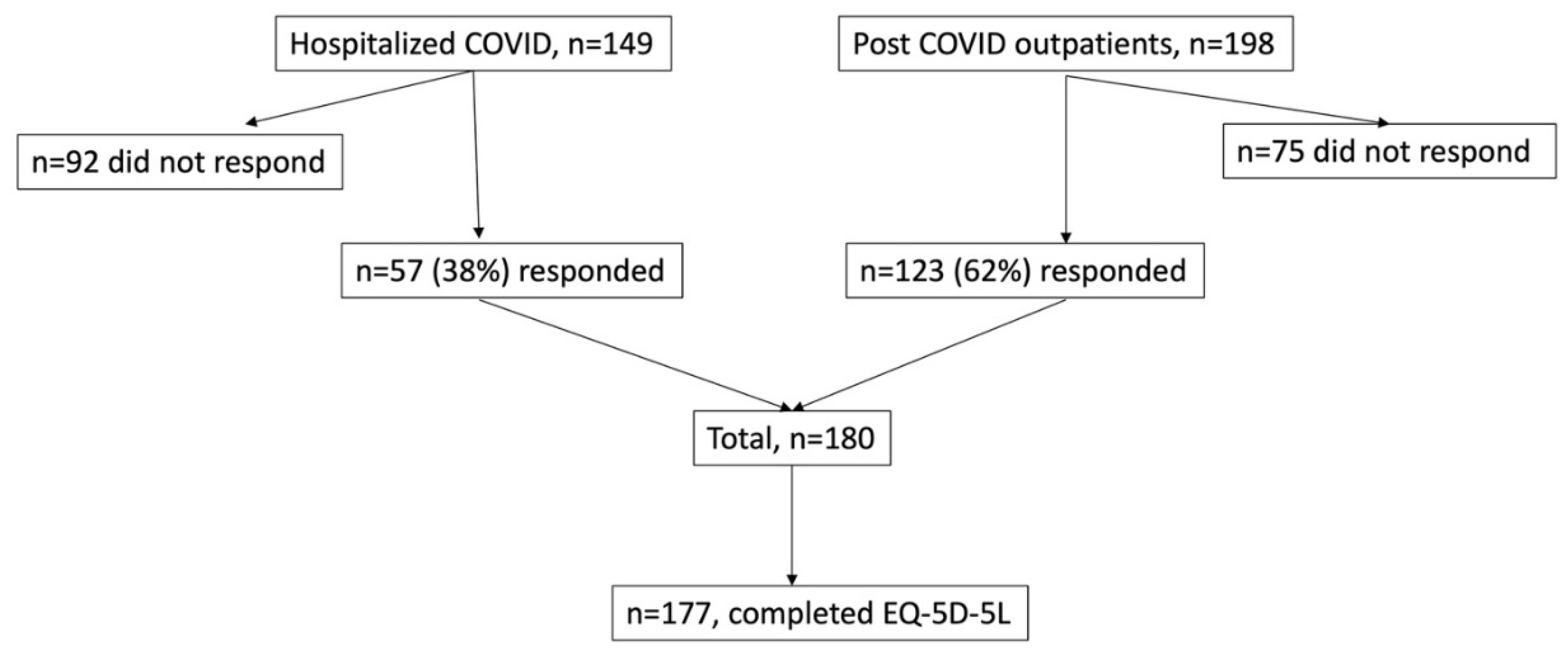

The “Hospitalized COVID” cohort included patients who had been admitted to the Department of Infectious Diseases at the Uppsala University Hospital for COVID-19 treatment. The patients had confirmed COVID-19 infection through a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal swab. They were contacted by telephone call between ten and eleven months after their initial infection. Furthermore, between April and July 2021, twelve months after the initial infection, 57 of the 149 hospitalized patients (38%) participated in a COVID-19 follow-up visit at the Department of Respiratory, Allergy, and Sleep Research at the Uppsala University Hospital,

Figure 1.

The “Post COVID outpatients” cohort comprised patients who were referred to the Post Covid outpatient clinic in the Uppsala Region. Enrolled criteria for the outpatients included the presence of persistent symptoms lasting at least 12 weeks after a COVID-19 diagnosis, which could be microbiologically verified by a positive PCR for SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal swab or probable, as per WHO and Delphi study, referred to as post COVID-19 condition [

2]. Between October 2021 and December 2022, a survey was sent to the home addresses of all enrolled patients (n=198) in the Post Covid cohort, along with a return envelope. A single reminder was sent to all participants within one month. Out of the invited patients, 123 (62%) responded,

Figure 1.

From the two cohorts, a total of 180 patients were initially included. Three individuals had missing answers within the EQ-5D-5L and they were excluded from the analyses. The final study population comprised 177 patients,

Figure 1.

EQ-5D-5L

Patients assessed their HRQoL using the EQ-5D-5L, which consist of five dimensions: mobility, self-care (ADL), usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Each dimension is evaluated for severity using a five-point scale: 1=no problem, 2=slight problems, 3=moderate problems, 4=severe problems and 5=extreme problems [

11]. Additionally, the questionnaire includes a Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS), where responders rate their health on a vertical axis ranging from zero “the worst imaginable condition” to 10, indicating “the best imaginable condition”. The EQ-5D-5L was present as a health profile by combining the responses into a five-number profile, ranging from 11111 (full health) to 55555 (worst health) [

11].

2.2. Persistent Symptoms and Their Severity

Patients were asked about any persistent symptoms following their initial COVID-19 infection. These symptoms included problems with fatigue, memory/concentration, dyspnea, cough, sore throat, nasal congestion, impaired taste and/or smell, heart palpitations, chest pain, vertigo, headache, muscle/joint pain, sleeping, depression, anxiety, gastrointestinal tract (including nausea, vomiting and stomach pain) and skin. Patients were then asked to rate the intensity of each symptom on a scale from 1 (very mild) to 10 (most severe). A score of zero was assigned if the patient did not experience any symptom. The most common persistent symptoms were problems with fatigue, memory/concentration, and dyspnea,

Figure S1. These symptoms were subsequently used in further analysis. Based on previous studies on symptoms such as pain, fatigue and dyspnea graded in 10-points scales, we choose to set the optimal cut-off point to distinguish between no/mild and severe symptom severity at 7 [

21,

22].

2.3. Covariates

The questionnaire collected sociodemographic characteristics, including education level (classified as: at least 3 years of university education resulted in an academic degree, at least 2 years vocational school, and up to secondary school), marital status (categorized as married, living with partner, single, divorced, widowed), country of birth (categorized as Sweden or other countries), primary work status (categorized as working, unemployed, on sick leave, retired, student or other), smoking status (classified as never, ex or current smoker) and use of snuff (user or non-user). Age and sex at birth (females or males) were determined using patient’s Swedish personal identification number.

Participants were also inquired about the severity of COVID-19 symptoms at onset (including very mild/mild, moderate, severe, or very severe), and whether they were hospitalized at infection onset. They reported any pre-existing medical conditions diagnosed by a doctor, including hypertension, heart disease (such as heart failure or acute myocardial infarction), thyroid disease, diabetes mellitus, lung disease (including asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)), cancer, conditions requiring immunosuppressive treatment, depression/anxiety, and chronic pain. Participants provided their weight and height, which were used to calculate their body mass index (BMI).

2.4. Ethics

This study followed the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr 2021-01891 and Dnr 2022-01261-01). All participants gave written informed consent to use their questionnaire answers.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to present the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of all patients. Categorical variables were expressed as proportions, continuous variables as means with standard deviations, and ordinal variables as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). Missing values within sociodemographic and clinical variables were <5% across all categorical variables and were not included in percentage calculations,

Table S1.

Patients with the most common persistent symptoms; fatigue, memory/concentration problems and dyspnea, were divided into two severity groups based on the rating score in a 10-point scale, with a cut off at 7.

The EQ-5D-5L health states were converted into a single utility score using a scoring algorithm. In this study, the Swedish value set and scoring algorithm were used to calculate utility scores (23). The potential values for Sweden from this algorithm range between -0.314 (worst imaginable health status) to 1 (best imaginable health status) [

23].

Spearman's correlation was used to investigate correlations among fatigue, memory/concntration problems, dyspnea, EQ-5D-5L dimensions, and the utility score. Correlation coefficients were interpreted as following: 0.1–0.29 (poor), 0.3–0.5 (fair), 0.6-0.79 (moderately strong), and 0.8-1.0 (very strong) [

24].

Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values were calculated to assess potential multicollinearity between different EQ-5D-5L dimensions. A VIF less than 5 indicated a low correlation of that predictor compare to other predictors [

25]. We found that a low VIF value that excluded significant multicollinearity concerns in the subsequent statistical models,

Figure S2.

Multiple regression analysis was used to assess the impact of EQ-5D-5L dimension scores (independent variables) on the severity of the symptoms: fatigue, memory/concentration problems and dyspnea (dependent variables). An exploratory analysis involved nine distinct multiple regression models to compare adjusted R-squared values for EQ-VAS (dependent variable).

All statistical analysis was conducted using R, version 4.1.1 (R Core Team, 2023) [

26]. The statistical significance level was set as 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Health Outcomes

This study included 177 patients, of whom 55.4% were females, and the average age of the study participants was 52 years,

Table 1. The mean EQ-5D-5L utility score in the study population was 0.77,

Table 1. All subjects who reported no problems on all EQ-5D-5L dimensions were categorized into the group of no/milder symptoms, except for one with severe fatigue problem. Perfect health on the EQ-5D-5L was reported by only 7% of the study patients. Patients in the higher severity groups of symptoms exhibited a lower prevalence of current employment, along with a higher incidence of comorbidities such as heart disease, lung disease, depression/anxiety and chronic pain. They also reported a higher number of persistent symptoms following COVID-19 and a lower EQ-VAS score, indicating the worst self-reported HRQoL,

Table 1. For example, patients experiencing severe fatigue reported an average 3.6 persistent symptoms and EQ-VAS score of 3, whereas those in the no/mild fatigue group had an average of 1.2 persistent symptoms and an EQ-VAS score of 6.

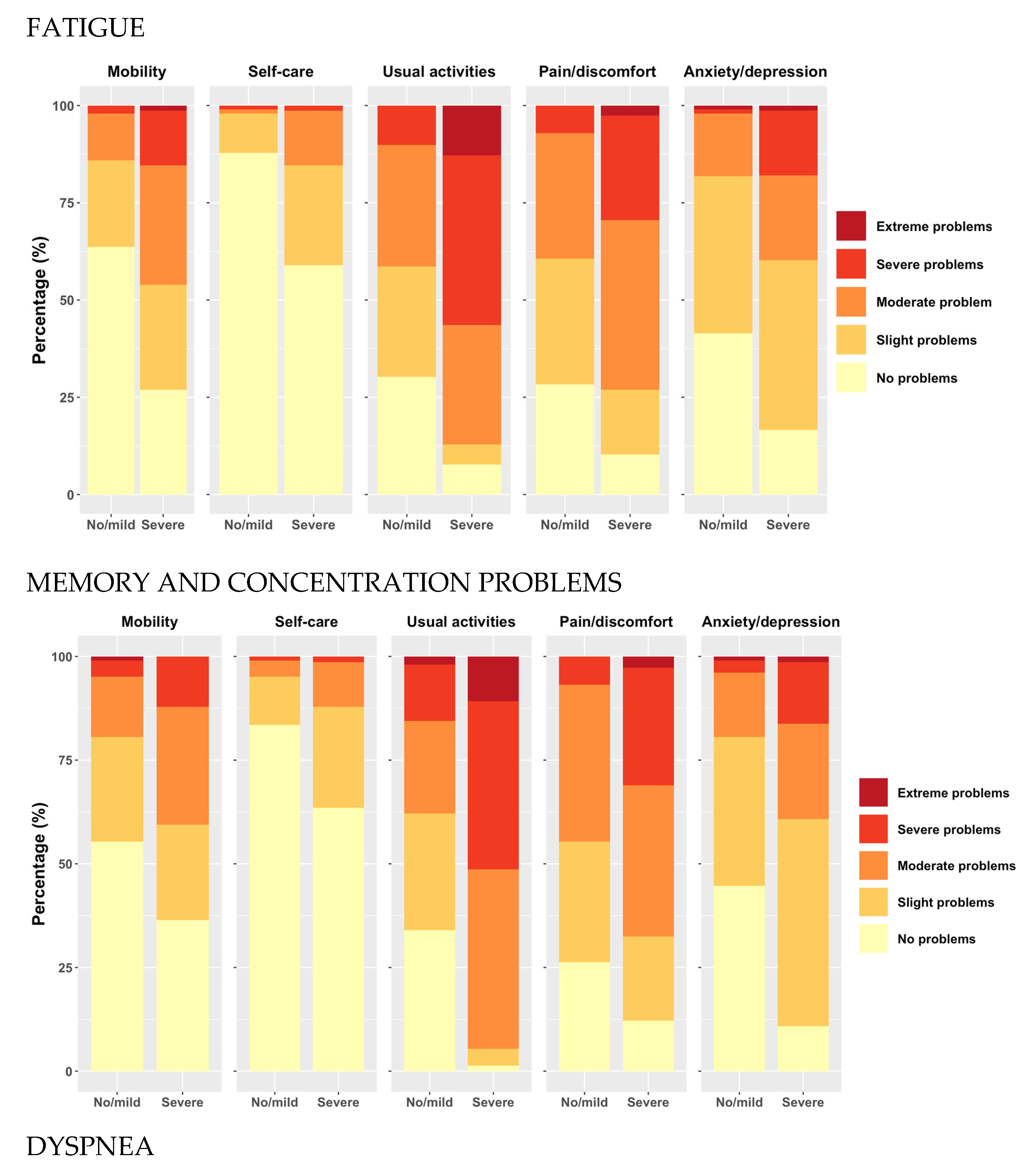

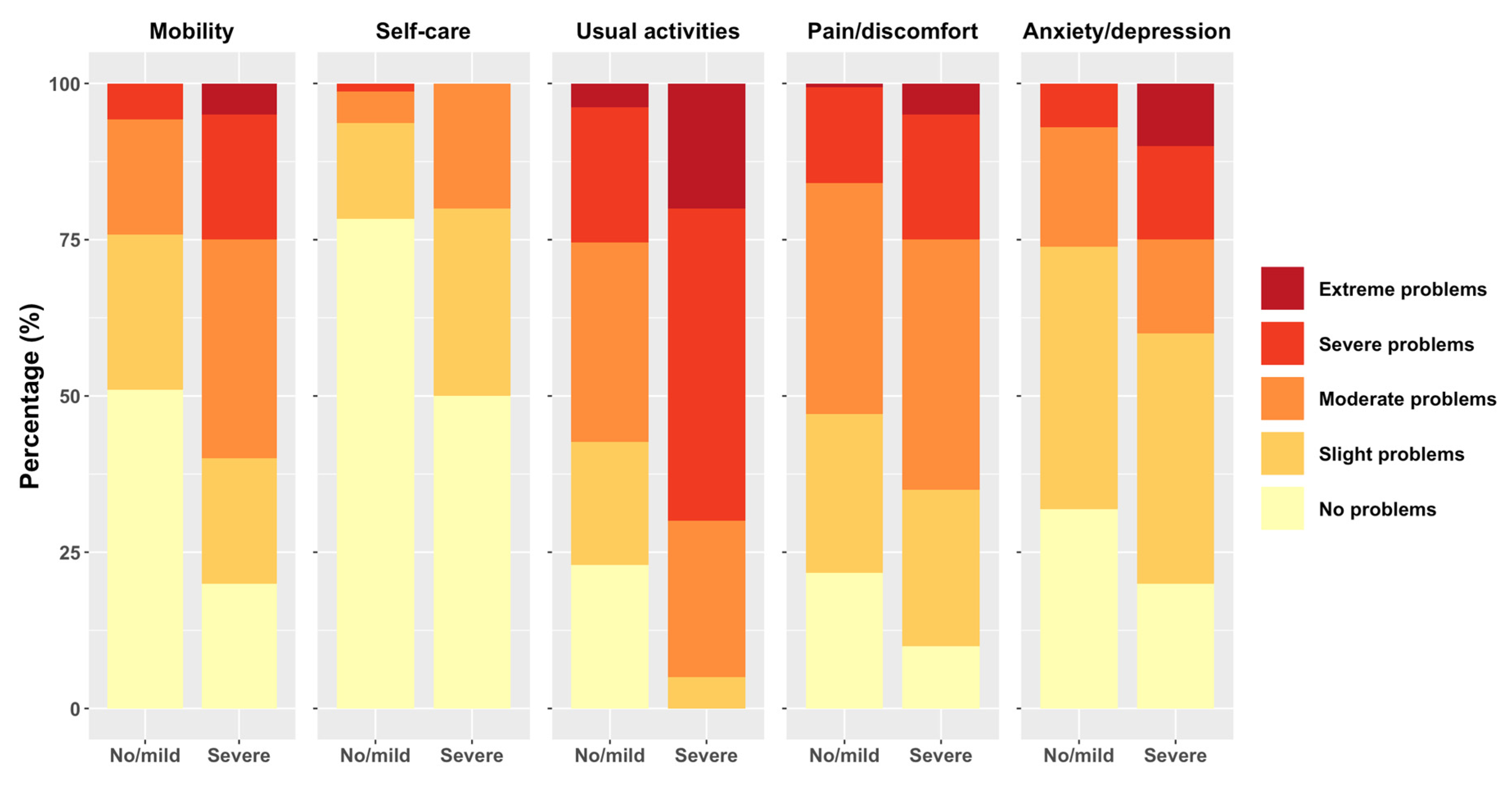

3.2. Distribution of Patients on EQ-5D-5L Dimensions for Fatigue, Memory/Concentration Problems and Dyspnea

The proportion of study patients reporting problems on the EQ-5D-5L was higher when experiencing severe fatigue, memory/concentration problems, or dyspnea in all dimensions. Among patients with severe fatigue, memory/concentration problems, and dyspnea, a notable higher proportion reported severe or extreme problems, particularly in the usual activities and pain/discomfort dimensions. For example, substantial percentage of patients with severe fatigue, memory/concentration problems and dyspnea reported extreme problems in “usual activities”. Notably, the self-care dimension exhibited the fewest reported problems across all respondents,

Figure 2.

3.3. Correlation of EQ-5D-5L Dimensions and Utility Scores with Fatigue, Memory/Concentration Problems, and Dyspnea

The strongest correlations were found between fatigue and memory/concentration problems, and between fatigue or memory/concentration problems and the “usual activities” dimension of EQ-5D-5L,

Table 2 and

Figure S3. Moderate correlations were observed between fatigue and memory/concentration problems and the other four dimensions of EQ-5D-5L (i.e. mobility, self-care, pain, and anxiety). Both fatigue and memory/concentration problems had a strong negative correlation with the utility scores, while dyspnea had a moderate negative correlation with utility scores.

3.4. Multiple Regression Analyses

Multiple regression analyses showed that the EQ-5D-5L dimensions explained 47.1% of the variance in fatigue, 54.6% in memory/concentration problems, and 14.4% in dyspnea,

Table 3. For fatigue and memory/concentration problems, it was evident that reporting problems at any level of “usual activities” significantly increased the severity of these symptoms compared to having no problems with “usual activities”. A similar pattern was found for experiencing severe problems with “self-care” (level 4) compared to no problems with self-care. No study patient reported an extreme problem with “self-care” (level 5). In addition, for memory/concentration problems, we found that reporting slight to moderate problems with anxiety/depression was linked to more severe complaints related to these symptoms compared to not having anxiety/depression. In the context of dyspnea, reporting slight problems with “self-care” (level 2) was associated with more pronounced complaints related to dyspnea compared to having no problems in this dimension (level 1). Furthermore, study patients who scored “1” (level 1) across all EQ-5D-5L dimensions reported fatigue, memory/concentration problems and dyspnea as 1.76, 0.99 and 1.48, respectively, on a scale of 0 to 10.

3.5. Explanatory Power of EQ-5D-5L with and without Symptoms for EQ VAS

The exploratory power of the EQ-VAS for the EQ-5D-5L’s utility score was lower than for the EQ-5D-5L dimensions (37.6% vs 57.7%). When comparing the explained variance of the EQ-VAS for EQ-5D-5L dimensions with symptom(s), we found that adding fatigue increased the exploratory power the most, with an increase of 5.5%. Then, adding memory/concentration problems or dyspnea increased the exploratory power with 1%, and 0.8%. respectively. Adding fatigue in combination with memory/concentration problems or dyspnea to the EQ-5D-5L resulted in a 5.3% increase of exploratory power, whereas adding all symptoms showed a 5.1% increase.

Table 4.

Explanatory power of EQ-5D-5L with and without fatigue, memory/concentration problems, and dyspnea for EQ-VAS.

Table 4.

Explanatory power of EQ-5D-5L with and without fatigue, memory/concentration problems, and dyspnea for EQ-VAS.

| Dependent variable |

Independent variables |

|

F value |

| EQ VAS |

Utility score** |

0.376 |

106.7** |

| |

MO*-ADL**-AC**-PA*-AN* |

0.577 |

13.63** |

| |

MO*-ADL**-AC**-PA-AN-FA** |

0.632 |

16.1** |

| |

MO*-ADL**-AC**-PA-AN-MC* |

0.587 |

13.48** |

| |

MO-ADL**-AC**-PA-AN*-DY |

0.585 |

13.38** |

| |

MO*-ADL**-AC**-PA-AN-FA**-MC |

0.630 |

15.26** |

| |

MO*-ADL**-AC**-PA-AN-FA**-DY |

0.630 |

15.24** |

| |

MO*-ADL**-AC**-PA-AN-MC-DY |

0.591 |

13.1** |

| |

MO*-ADL**-AC**-PA-AN-MC-DY-FA** |

0.628 |

14.48** |

4. Discussion

Main Findings

Our study revealed that while the EQ-5D-5L dimensions offered some insight into fatigue and memory/concentration problems, they performed poorly in capturing dyspnea. Specifically, the EQ-5D-5L explained 55% of the variance in memory/concentration problems, 47% in fatigue and 14% only in dyspnea. Among these dimensions, the “usual activities” dimension exhibited the strongest correlation with fatigue and memory/concentration problems. This correlation was consisting across all levels within this dimension, indicating a progressive increase in problems with usual activity corresponding to the severity of fatigue and memory/concentration problems. In contrast, the other EQ-5D-5L dimensions demonstrated only moderate to weak correlations with fatigue and memory/concentration problems. Notably, the “usual activities” dimension alone showed a stronger association with fatigue and memory/concentration problems then the utility score representing all EQ-5D-5L dimensions.

Additionally, we found that the “self-care” dimension had a statistically significant impact on fatigue and memory/concentration problems, but only at level 4 within this dimension. It is noteworthy that no patient reported level 5 in the “ADL” dimension. This observation suggest that the study patients generally did not experience high levels of problems in their activities of daily living.

Our study revealed that dyspnea displayed weak associations with all EQ-5D-5L dimensions, and these correlations were inconsistent across different levels of any dimension. When assessing dyspnea, we did not identify a statistically significant trend across multiple levels of any EQ-5D-5L dimension. Instead, we found only an isolated significant association with slight problems in the “self-care” dimension. However, our descriptive analysis did highlight a higher prevalence of moderate, severe, and extreme problems in the “mobility” dimension, as well as severe and extreme problems in the ‘’usual activities’’ dimension and “depression and anxiety” among patients with severe dyspnea, as compared to those with no/milder symptoms. This suggests that there might be unaccounted factors or complexities underlying dyspnea in patients with post COVID-19 condition that may contribute to the weak overall associations observed in the regression analysis. Further research is needed to explore these associations.

In our exploratory analysis, we observed that adding fatigue to the EQ-5D-5L significantly improved the explained variance of the EQ-VAS. However, adding memory/concentration problems or dyspnea had little effect on the explained variance. Notably, when two symptoms such as fatigue and memory/concentration problems or fatigue and dyspnea were added to the EQ-5D-5L, the explained variance was slightly lower than when adding fatigue alone. This may be attributed to the strong correlation between fatigue and memory/concentration problems, as well as the moderate correlation between fatigue and dyspnea.

We found that using the utility score as an independent variable alone resulted in significantly weaker explained variance compared to using all the EQ-5D-5L dimensions as independent variables. This suggests that despite the utility score being a summary of the dimensions, a substantial amount of information is lost when using it exclusively. Therefore, our finding suggests that in the clinical practice, it may be more informative to consider all the EQ-5D-5L dimension rather than relying solely in the utility score that represents them.

Comparison to Previous Studies

Our findings were consistent with previous research, Geraerds et al. They found that EQ-5D-5L partially capture fatigue and memory/concentration problems in patients with Q-fever [

16]. Similarly, a study on COPD patients, observed a correlation between EQ-5D-5L and fatigue [

27]. A Dutch study found that in the general population fatigue was partially covered by the EQ-5D-5L, with the domains “usual activities” and “pain and discomfort”, whereas “self-care” contributed the least. In this study, the link between EQ-5D-5L domains and fatigue was stronger in subjects with at least one chronic disease compared to healthy individuals [

28]. However, there is a study that found limited additional explanatory power of EQ-5D-5L with regard to fatigue [

15]. This disparity might arise from their use of the 3-level EQ-5D variant and the simultaneous inclusion of multiple dimensions, which could have weakened the impact of individual symptoms.

Furthermore, the cognitive dimension has been added to EQ-5D-5L and EQ-5D in studies involving patients following stroke, or with hearing and vision impairments [

29,

30]. In trauma-related research, the addition of question about cognitive symptoms has been shown to enhance the EQ-5D's explanatory power for EQ-VAS [

31,

32,

33].

In terms of respiratory symptoms, our results align with the findings from a study on COPD patients, which suggested a potential inadequacy in the EQ-5D-5L's ability to capture dyspnea, especially in a general healthy population [

34]. However, in contrast to our study, Nolan et al. found a strong correlation between the utility score and dyspnea, using a disease-specific assessment for chronic respiratory conditions [

27]. This discrepancy raises the possibility of enhancing the EQ-5D-5L by including questions related to respiratory symptoms.

Finally, it is important to note that in our study, fatigue significantly surpassed memory/concentration problems in contributing to the EQ-5D-5L's predictive capacity for EQ-VAS scores. This nuance challenges our findings in the context of post COVID-19 condition. Nonetheless, the potential added value of incorporating a fatigue dimension into the EQ-5D-5L should be explored using various methodologies in future studies on the sequelae of infectious diseases such as COVID-19.

Strengths and Limitations

The strength of this study is that it is among the first evaluating sensitivity of the EQ-5D- in capturing fatigue, memory/concentration problems, and dyspnea in patients with post COVID-19 condition. Furthermore, it includes two cohorts of Swedish patients with different severity of initial COVID-19 infection, both hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients. This diversity provides a more comprehensive understanding of the HRQoL and the severity of persistent symptoms in patients with post COVID-19. Additionally, the measurement of the HRQoL employed the EQ-5D-5L and the EQ-VAS, both robust and comprehensive tolls. These instruments have been previously validated across diverse populations.

The study carries some potential limitations. Firstly, the relatively small number of participants, along with a modest response rate, may impede the generalizability of our results. Therefore, it is important to view this study as exploratory in nature. Secondly, the representativeness of the study sample may be constrained due to testing limitation in Sweden during the early days of the pandemic. A notable part of the cohort from the post COVID outpatients did not have laboratory-confirmed diagnosis, further limiting the study’s scope and generalizability.

Third, a limitation arises from the absence of data on the duration of persistent symptoms, as this information was not available during the study for post COVID outpatients. However, all patients reported symptoms persistent for at least three months, meeting the criteria for the post COVID-19 condition diagnosis [

2].

Fourth, the methodology employed a simple question to assess persistent symptoms and rate their severity in a 10-points scale, with a cutoff at 7, drawing inspiration from other scales designed for dyspnea and pain. Notably, a relatively small proportion of patients reported severe dyspnea, potentially introducing limitations to the precision of the measurements for this specific symptom (defined as differential misclassification). In contrary, the number of patients in the subgroups categorized as having no/mild or severe severity levels for the symptoms of fatigue and memory/concentration problems was approximately equal.

Additionally, some of information collected through the questionnaire, such as severity of symptoms at infection onset, may introduce recall bias, as patients might have difficulty accurately recall in past details.

5. Conclusions

Our exploratory study has illuminated both the strengths and challenges of the EQ-5D-5L tool in assessing HRQoL among post COVID-19 patients. The EQ-5D-5L demonstrated its partial ability in capturing fatigue and memory/concentration problems in these patients. However, it faced difficulties in adequately addressing dyspnea. The addition of a fatigue dimension emerged as a valuable enhancement in the context of post COVID-19 condition. This could enhance the tool’s sensitivity and its ability to capture the everyday life problems in these patients. It has the potential to identify those who are most affected by their symptoms enabling healthcare providers to priorities them for rehabilitation efforts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: The prevalence of symptoms in the study population.; Table S1: The frequency of missing values. Figure S2: Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values for EQ-5D-5L dimensions. Figure S3: Heatmap of Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients. The blue color represents a positive correlation and the red color represents a negative correlation between two variables. The scale to the right of the heatmap shows the strength of the correlation coefficient between the variables.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.K., H.J.; methodology, M.A.K. and X.Z.and C.W..; software, C.W..; validation, all authors; investigation, M.A.K., H.J, and E.R.; resources, M.A.K, C.J..; data curation, C.W. X.Z., M.A.K; writing—original draft preparation, C.F. and C.W.; writing—review and editing, all authors.; visualization, M.A.K., C.W..; supervision, M.A.K., X.Z., project administration, M.A.K.; funding acquisition, M.A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Åke Wiberg Stiftelsen (stipendium M23-0133, M22-0119 and M21-0080), Lars Hiertas Minne Stiftelsen (stipendium F02021-0144 and F02022-0098) and Sven och Dagmar Saléns Stiftelse (stipendium 2022) and Tore Nilsons Stiftelsen (stipendium 2021-00935).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study followed the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr 2021-01891 and Dnr 2022-01261-01).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be available on demand.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Crook H, Raza S, Nowell J, Young M, Edison P. Long covid-mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ. 2021;374:n1648. [CrossRef]

- WHO. A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post_COVID-19_condition-Clinical_case_definition-2021.1 Last seen 20231013. 2021.

- O'Mahoney LL, Routen A, Gillies C, Ekezie W, Welford A, Zhang A; et al. The prevalence and long-term health effects of Long Covid among hospitalised and non-hospitalised populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;55:101762. [CrossRef]

- Rajan S, Khunti K, Alwan N, Steves C, MacDermott N, Morsella A; et al. In the wake of the pandemic: Preparing for Long COVID. European Observatory Policy Briefs. Copenhagen (Denmark)2021.

- Wahlgren C, Forsberg G, Divanoglou A, Ostholm Balkhed A, Niward K, Berg S; et al. Two-year follow-up of patients with post-COVID-19 condition in Sweden: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2023;28:100595. [CrossRef]

- Havervall S, Rosell A, Phillipson M, Mangsbo SM, Nilsson P, Hober S; et al. Symptoms and Functional Impairment Assessed 8 Months After Mild COVID-19 Among Health Care Workers. JAMA. 2021;325(19):2015-6. [CrossRef]

- Moller M, Borg K, Janson C, Lerm M, Normark J, Niward K. Cognitive dysfunction in post-COVID-19 condition: Mechanisms, management, and rehabilitation. J Intern Med. 2023;294(5):563-81. [CrossRef]

- Fedorowski A, Olsen MF, Nikesjo F, Janson C, Bruchfeld J, Lerm M; et al. Cardiorespiratory dysautonomia in post-COVID-19 condition: Manifestations, mechanisms and management. J Intern Med. 2023;294(5):548-62. [CrossRef]

- Mazer B, Ehrmann Feldman D. Functional Limitations in Individuals With Long COVID. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2023;104(9):1378-84. [CrossRef]

- Zhou T, Guan H, Wang L, Zhang Y, Rui M, Ma A. Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients With Different Diseases Measured With the EQ-5D-5L: A Systematic Review. Front Public Health. 2021;9:675523. [CrossRef]

- Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen M, Kind P, Parkin D; et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20(10):1727-36. [CrossRef]

- Devlin NJ, Brooks R. EQ-5D and the EuroQol Group: Past, Present and Future. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15(2):127-37. [CrossRef]

- Sigfrid L, Drake TM, Pauley E, Jesudason EC, Olliaro P, Lim WS; et al. Long Covid in adults discharged from UK hospitals after Covid-19: A prospective, multicentre cohort study using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;8:100186. [CrossRef]

- Malik P, Patel K, Pinto C, Jaiswal R, Tirupathi R, Pillai S; et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (PCS) and health-related quality of life (HRQoL)-A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2022;94(1):253-62. [CrossRef]

- Jelsma J, Maart S. Should additional domains be added to the EQ-5D health-related quality of life instrument for community-based studies? An analytical descriptive study. Popul Health Metr. 2015;13:13. [CrossRef]

- Geraerds A, Polinder S, Spronk I, Olde Loohuis AGM, de Groot A, Bronner MB; et al. Sensitivity of the EQ-5D-5L for fatigue and cognitive problems and their added value in Q-fever patients. Qual Life Res. 2022;31(7):2083-92. [CrossRef]

- Kisiel MA, Nordqvist T, Westman G, Svartengren M, Malinovschi A, Janols H. Patterns and predictors of sick leave among Swedish non-hospitalized healthcare and residential care workers with Covid-19 during the early phase of the pandemic. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(12):e0260652. [CrossRef]

- Kisiel MA, Lee S, Malmquist S, Rykatkin O, Holgert S, Janols H; et al. Clustering Analysis Identified Three Long COVID Phenotypes and Their Association with General Health Status and Working Ability. J Clin Med. 2023;12(11). [CrossRef]

- Kisiel MA, Janols H, Nordqvist T, Bergquist J, Hagfeldt S, Malinovschi A; et al. Predictors of post-COVID-19 and the impact of persistent symptoms in non-hospitalized patients 12 months after COVID-19, with a focus on work ability. Ups J Med Sci. 2022;127. [CrossRef]

- Kisiel MA, Lee S, Janols H, Faramarzi A. Absenteeism Costs Due to COVID-19 and Their Predictors in Non-Hospitalized Patients in Sweden: A Poisson Regression Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(22). [CrossRef]

- Oldenmenger WH, de Raaf PJ, de Klerk C, van der Rijt CC. Cut points on 0-10 numeric rating scales for symptoms included in the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale in cancer patients: A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(6):1083-93. [CrossRef]

- Williams MW, Smith EL. Clinical utility and psychometric properties of the Disability Rating Scale with individuals with traumatic brain injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2017;62(3):407-8. [CrossRef]

- Sun S, Chuang LH, Sahlen KG, Lindholm L, Norstrom F. Estimating a social value set for EQ-5D-5L in Sweden. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2022;20(1):167. [CrossRef]

- Chan YH. Biostatistics. Basic statystic for doctors. Correlation Analysis. . J. SM, editor2003.

- James G, Witten, D., Hastie, T., and Tibshirani, R. . An introduction to statistical learning: With applications in R. . New York: Springer; 2013.

- Team RC. R:A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. V. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 21 May 2023).2023 [.

- Nolan CM, Longworth L, Lord J, Canavan JL, Jones SE, Kon SS; et al. The EQ-5D-5L health status questionnaire in COPD: Validity, responsiveness and minimum important difference. Thorax. 2016;71(6):493-500. [CrossRef]

- Spronk I, Polinder S, Bonsel GJ, Janssen MF, Haagsma JA. The relation between EQ-5D and fatigue in a Dutch general population sample: An explorative study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19(1):135. [CrossRef]

- de Graaf JA, Kuijpers M, Visser-Meily J, Kappelle LJ, Post M. Validity of an enhanced EQ-5D-5L measure with an added cognitive dimension in patients with stroke. Clin Rehabil. 2020;34(4):545-50. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Rowen D, Brazier J, Tsuchiya A, Young T, Longworth L. An exploratory study to test the impact on three "bolt-on" items to the EQ-5D. Value Health. 2015;18(1):52-60. [CrossRef]

- Ophuis RH, Janssen MF, Bonsel GJ, Panneman MJ, Polinder S, Haagsma JA. Health-related quality of life in injury patients: The added value of extending the EQ-5D-3L with a cognitive dimension. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(7):1941-9. [CrossRef]

- Geraerds A, Bonsel GJ, Janssen MF, de Jongh MA, Spronk I, Polinder S; et al. The added value of the EQ-5D with a cognition dimension in injury patients with and without traumatic brain injury. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(7):1931-9. [CrossRef]

- Geraerds A, Bonsel GJ, Polinder S, Panneman MJM, Janssen MF, Haagsma JA. Does the EQ-5D-5L benefit from extension with a cognitive domain: Testing a multi-criteria psychometric strategy in trauma patients. Qual Life Res. 2020;29(9):2541-51. [CrossRef]

- Hoogendoorn M, Oppe M, Boland MRS, Goossens LMA, Stolk EA, Rutten-van Molken M. Exploring the Impact of Adding a Respiratory Dimension to the EQ-5D-5L. Med Decis Making. 2019;39(4):393-404. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).