Submitted:

08 April 2024

Posted:

09 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Selection of Relevant Literature and Network and Semantic Analysis

2.1. Search Criteria and Meta-Sources

2.2. Identification of Articles by the Top-Down Analysis

2.3. Analysis of the Selected Literature

2.3.1. Network and Temporal Analysis

- the density map allows to visualize the relevant keywords and how these are clustered according to their co-occurrences in the articles;

- the network map allows to explore the most relevant linked keywords;

- the overlay map allows to analyse the temporal appearance of the keywords.

- the red cluster focuses mainly on:

- “spatial data infrastructures” and related technologies like “metadata”, “standards” (see “inspire” and “open geospatial consortium”), “interoperability”, “data sharing”, “Web processing services”, “geo-spatial services”, in application for “disaster prevention” and “disaster management”;

- the green cluster is mainly about:

- “spatio temporal analysis”, “principal component analysis” and “environmental monitoring” by “remote sensing” and “space optics”. Sources like “landsat” and “modis” appear and keywords indicating application fields like “agriculture”, “climate change”, “crops”, “vegetation”, “droughts”, “ecosystems”, “land cover”, “land use”, “soil salinization”;

- the blue cluster is mainly related with:

- “decision support systems” exploiting “big data” and “database systems” for their “digital storage”, “artificial intelligence” for “data acquisition”, “data integration”, “decision making” and “semantic Web” techniques for global scale applications including “sustainable development”, “Earth science” and “Earth observation”.

- Among the keywords that appeared just at the beginning of the considered period (up to 2012) we can find “geographic information systems”, “photogrammetry”, “metadata”, “decision support systems”;

- in the intermediate period of time, we have “spatial data infrastructures” and “remote sensing” and later “disasters”;

- while the most recent keywords are “big data”, “artificial intelligence”, “earth observation”, and applications to “agriculture”, “droughts”, “soil salinization”.

2.3.2. Semantic Analysis

3. Relevant Initiatives and Projects for Building SDI for Remote Sensing

3.1. The European Initiatives for Environmental Research Infrastructures—ENVRI

- Common data policies for further development of the common standards and policies for data life cycle, cataloguing, curation, provenance and service provision within environmental research infrastructures;

- Open science to sharing data and software;

- Capacity building for improved skills of the research infrastructure (RI) personnel so they can develop and maintain the FAIR infrastructures;

- Innovation of each RI by establishing a specific ENVRI-FAIR service catalogue section in the EOSC catalogue;

- Global cooperation for a cohesive global RI, including other RI clusters, regional and international initiatives in the environmental sector;

- Exposure of thematic data services and tools from the RI catalogues to the EOSC catalogue of services, including COPERNICUS, GEO and other end-users.

3.1.1. The European Plate Observing System (EPOS)

3.1.2. Sentinel Hub (ESA Copernicus Project)

3.2. Google Earth Engine

3.3. The Open Data Cube (ODC)

3.4. The System for Earth Observation Data Access, Processing and Analysis for Land Monitoring (SEPAL)

3.5. The Big Data Analytic Platform (BADP) of the Joint Research Center (JRC)

3.6. The OpenEO project

3.7. The High Performance Cloud Computing for Remote Sensing Big Data Management and Processing (pipsCloud)

3.8. The U.S. GeoPlatform of the National Spatial Data Infrastructure (NSDI)

3.9. The EarthExplorer of the United States Geological Survey USGS (EE)

3.10. Earthdata from NASA

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

References

- Page, M.J., McKenzie, J.E., Bossuyt, P.M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T.C., Mulrow, C.D., Shamseer, L.,Tetzlaff, J.M., Akl, E.A., Brennan, S.E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J.M.,Hr´objartsson, A., Lalu, M.M., Li, T., Loder, E.W., Mayo-Wilson,E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L.A., Stewart, L.A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A.C., Welch, V.A., Whiting, P., Moher, D., 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71, arXiv:https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n71.full.pdf.

- Nebert DD (ed) (2004) Developing spatial data infrastructures: the SDI cookbook. Global Spatial Data Infrastructures Association (Online: Spatial Data Infrastructure Cookbook v2.0 (PDF) January 2004).

- Granell, C., Díaz, L., Gould, M. (2010). Service-oriented applications for environmental models: Reusable geospatial services. Environmental Modelling & Software, 25(2), 182-198, ISSN 1364-8152. [CrossRef]

- Evangelidis, K., Ntouros, K., Makridis, S., & Papatheodorou, C. (2014). Geospatial services in the Cloud. Computers & Geosciences, 63, 116-122.

- Müller, M., Bernard, L., & Kadner, D. (2013). Moving code–Sharing geoprocessing logic on the Web. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 83, 193-203.

- Lehmann, A., Giuliani, G., Ray, N., Rahman, K., Abbaspour, K. C., Nativi, S., ... & Beniston, M. (2014). Reviewing innovative Earth observation solutions for filling science-policy gaps in hydrology. Journal of Hydrology, 518, 267-277.

- Yue, P., Guo, X., Zhang, M., Jiang, L., & Zhai, X. (2016). Linked Data and SDI: The case on Web geoprocessing workflows. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 114, 245-257.

- Innerebner, M., Costa, A., Chuprikova, E., Monsorno, R., & Ventura, B. (2017). Organizing earth observation data inside a spatial data infrastructure. Earth Science Informatics, 10, 55-68.

- Woodgate, P., Coppa, I., Choy, S., Phinn, S., Arnold, L., & Duckham, M. (2017). The Australian approach to geospatial capabilities; positioning, earth observation, infrastructure and analytics: issues, trends and perspectives. Geo-spatial information science, 20(2), 109-125.

- Wiemann, S., Karrasch, P., & Bernard, L. (2018). Ad-hoc combination and analysis of heterogeneous and distributed spatial data for environmental monitoring–design and prototype of a web-based solution. International journal of digital earth, 11(1), 79-94.

- Magno, R., De Filippis, T., Di Giuseppe, E., Pasqui, M., Rocchi, L., & Gozzini, B. (2018). Semi-automatic operational service for drought monitoring and forecasting in the Tuscany region. Geosciences, 8(2), 49.

- Cignetti, M., Guenzi, D., Ardizzone, F., Allasia, P., & Giordan, D. (2019). An open-source web platform to share multisource, multisensor geospatial data and measurements of ground deformation in mountain areas. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 9(1), 4.

- Hu, L., Zhang, C., Zhang, M., Shi, Y., Lu, J., & Fang, Z. (2023). Enhancing FAIR data services in agricultural disaster: A review. Remote Sensing, 15(8), 2024.

- Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IJ, Appleton G, Axton M, Baak A, Blomberg N, Boiten J-W, Da Silva Santos LB, Bourne PE+43 more. 2016. The FAIR guiding principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Nature 3:160018.

- Gomes, V.C.F.; Queiroz, G.R.; Ferreira, K.R. An Overview of Platforms for Big Earth Observation Data Management and Analysis. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1253. [CrossRef]

- https://www.epos-eu.org/.

- https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/.

- https://scihub.copernicus.eu/.

- https://earthengine.google.com/.

- https://www.opendatacube.org/.

- https://sepal.io/.

- https://jeodpp.jrc.ec.europa.eu/bdap/.

- https://openeo.org.

- http://www.pipscloud.net/index.asp.

- https://ngda-themes-dev-geoplatform.hub.arcgis.com/.

- https://www.fgdc.gov/initiatives/geospatial-platform.

- https://www.usgs.gov/.

- https://www.usgs.gov/products.

- https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov.

| Dimension | Choice Description/Motivation | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| SDI goal | Aimed at specifying main goal(s) of the SDI | This dimension is usually described in the papers |

| SDI scope | Aimed at reporting the geographic coverage of data in the SDI | It is usually described in the papers, though some of them deal with methodological aspects and do not explicit data coverage |

| Data variety | Fundamental to define data types that are dealt with in each paper | This dimension is usually described in the papers |

| Data velocity | Meant to understand time resolution of data considered | Papers do not describe accurately this dimension; only some papers explicit the goal to deal with near real-time data |

| Data volumes | Meant to define the volume of the data managed | Usually, papers do not describe this dimension |

| Data veracity | Meant to understand if data credibility/trust is represented, for example by quality indicators, or is implicitly modeled by data uncertainty/vagueness | Usually, papers do not describe this dimension |

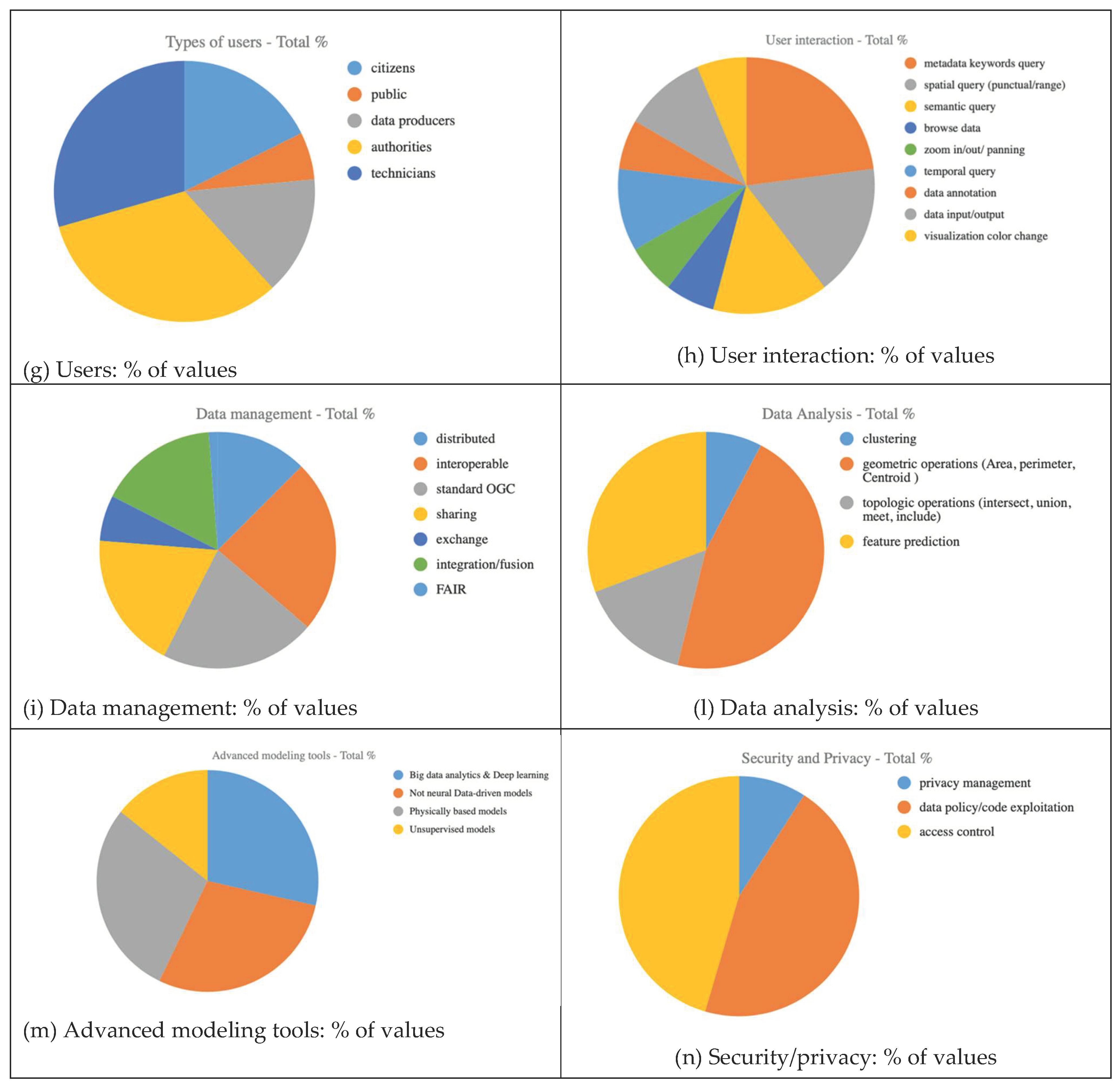

| Users | It details target users of the SDI | Most papers do not specify values for this dimension; aside when decision support is the main goal |

| User interaction | Aimed at detailing functions offered for user interaction | Besides discovery via metadata, papers do not describe accurately this dimension |

| Data management | Main architectural/technical pillars of data management | This dimension is usually well described in the papers |

| Data analysis | Meant to understand if SDI provides also analysis tools, typical of geographic information systems | Papers do not describe accurately this dimension |

| Advanced modeling tools | Meant to understand if SDI provides AI modeling facilities, typical of recent information systems | Usually, papers do not describe this dimension |

| Security/privacy | Meant to understand if specific policies or related concerns are considered in papers | Usually, papers do not describe this dimension |

| Platform | Description | Scope | Data and Interoperability | Functionalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1.1 EPOS (European Plate Observing System) | Pan-European infrastructure for solid Earth science, providing facilities, data, and services for researchers; it focuses on interoperability standards to ensure seamless data exchange and accessibility among different geoscientific communities. | European Research Infrastructure. | Use only OGC standards and target FAIR principles Integration of diverse datasets related to Earth's structure, dynamics, and hazards. It includes satellite observations, unmanned aerial vehicles, and citizen science projects. |

Data storage and catalogue service plus processing. Open policy. Maximize public benefit following FAIR principles. Future directions: embracing emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, and advanced sensing techniques; expanding geographic coverage beyond Europe. |

| 3.1.2 Sentinel Hub (component of the Copernicus European space Program) | It provides free and open access to Earth observation data from remote sensing collected by the satellites of Sentinel fleet. It offers customizable services for users to access, process, and analyze satellite imagery. | Developed in the framework of Copernicus (ESA and European Community). | Only RS data and derived products Use only OGC standards Multispectral imagery: data across different wavelengths, enabling detailed analysis of land cover, vegetation, and other environmental features. |

Data storage and catalogue service plus processing. Open policy It applies cloud computing technologies, for efficient storage, processing, and access to large volumes of Earth observation data. Features are made available through OGC services and a RESTful API. Compatibility with other Earth observation systems is delegated to downstream services. |

| 3.2 Google Earth Engine (GEE) | A cloud-based platform for planetary-scale geospatial analysis that provides access to a vast amount of remote sensing data and other geospatial data. | Built from a collection of technologies made available by Google. It operates within its proprietary framework rather than conforming to widely recognized SDI standards. | Only proprietary tools After the free availability of Landsat series in 2008, Google archived diverse datasets, including satellite data from Copernicus program, GIS-based vector datasets, social, demographic, weather, digital elevation models, and climate data. |

Data storage and catalogue service plus processing. GEE focuses on processing and analyzing Earth Observation data rather than serving as a broader infrastructure for spatial data exchange and sharing. Its user-friendly front-end facilitates interactive algorithm development, allowing users to add and curate their data. |

| 3.3 Open Data Cube (ODC), past Australian Geoscience Data Cube |

It enables cataloguing massive EO datasets, providing access and manipulation through command line tools and a Python API. It provides OGC web services and tools for deployment, data access, and statistics extraction. | Supported by organizations like Analytical Mechanics Associates (AMA), and US Geological Survey (USGS) | Proprietary tools and OGC standards Mainly satellite data management. |

Data storage and catalogue service plus processing. Open policy (API available) ODC's source code and tools are open and distributed through various git repositories. ODC lacks tools for easy data and application sharing, requiring manual efforts. |

| 3.4 System for Earth Observation Data Access, Processing, and Analysis for Land Monitoring (SEPAL) | A cloud computing platform for automatic land cover monitoring. It combines cloud services like Google Earth Engine (GEE) and Amazon Web Services (AWS) with free software. SEPAL focuses on creating a pre-configured environment to manage computational resources in the cloud. | Developed by several private and governamental organizations among which ESA, Google, NASA, ETH Zurich, etc. Initiated by the UN FAO Forestry Department and financed by Norway. | Only proprietary tools Mainly EO data for land monitoring |

Open policy (API available) SEPAL's source code is available under the MIT license. It offers tools for image search, storage browsing, machine initiation, and applications like RStudio and Jupyter Notebook. SEPAL lacks web services for data access and processing requests, and users are responsible for developing applications to utilize available computational resources. |

| 3.5 Big Data Analytic Platform (BADP) | Built on Open source software to serve JRC users and designed to handle large-scale geospatial data streams, offering a scalable solution to multi-petabyte data volumes. The system employs distributed storage and a cluster of computing nodes using commodity hardware for both storage and processing. | Successor of the European Joint Research Center (JRC) Earth Observation Data and Processing Platform (JEODPP). It supports a variety of projects in agriculture, forestry, environment, disaster risk management, development, health, and energy. | EO and geospatial data | Data storage and catalogue service plus processing. |

| 3.6 OpenEO | A project consolidating technologies for storing and processing Earth Observation (EO) data in the cloud. It aims to alleviate concerns about vendor dependency by offering a standardized, open-source application programming interface (API) for EO data and Copernicus applications. | A collaborative initiative involving multiple contributors and institutions around the world. ESA openEO platform implements the specifications of OpenEO project and provides intuitive programming libraries to process a wide variety of EO datasets. | Only RS data and derived products Target OGC standards EO data |

Open policy (API available) The project significantly contributes to reducing barriers for the EO community in adopting cloud computing technologies and big EO data analysis platforms. In December 2023 openEO has been submitted to OGC for consideration as an OGC community standard. Several members of the OCG already endorsed the OCG submission of openEO, among which ESA and Eurac Research. |

| 3.7 High performance cloud computing for remote sensing big data management and processing (pipsCloud) | Solution for managing and processing extensive EO data through cloud computing. | Proprietary solution developed by Chinese research institutions, with a proprietary file system, developed exclusively by Chinese institutions. | Only proprietary tools Remote sensing data. |

Data storage and catalogue service plus processing. The platform lacks functionalities for exporting data using OGC standards, hinders science reproducibility, and is restricted for internal use by participating institutions. |

| 3.8 U.S. GeoPlatform of the National Spatial Data Infrastructure (NSDI) | A platform making more FAIR all U.S. federal official National Geospatial Data Assets (NGDAs ). | The Geospatial Platform is a U.S. cross-agency collaborative Open Government effort, emphasizing government-to-citizen communication, accountability, and transparency. | Only OGC standards and target FAIR principles Remote Sensing data and geospatial data |

Only data storage and catalogue service. |

| 3.9 EarthExplorer of the United States Geological Survey USGS (EE) | A web-based platform that provides users the ability to query, search, and order satellite images, aerial photographs, and cartographic products from several sources. | In 2008, USGS has democratized the use of Landsat data by making all new and archived Landsat imagery accessible over the Internet under a free and open data policy. | Only proprietary tools. The world’s largest civilian collection of images of the Earth’s surface, including LANDSAT images, aerial photography, elevation and land cover datasets, digitized maps, MODIS land data products from the NASA Terra and Aqua missions, ASTER level-1B data products over the U.S. and Territories from the NASA ASTER mission. |

Only data storage and catalogue service. It provides several facilities among which advanced search and query capabilities, allowing users to specify criteria such as geographic extent, time range, and specific sensors; an ordering system that enables users to request and download the selected data products. The platform incorporates security measures to protect user data and ensure proper authentication and authorization processes. |

| 3.10 NASA Earthdata website | NASA gateway providing full and open access to NASA’s collection of Earth science data | NASA worldwide imagery | Only RS data and derived products Proprietary tools and OGC standards |

Data storage and catalogue service plus processing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).