Submitted:

04 April 2024

Posted:

08 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- A pivotal aspect of omnichanneling is the capacity to personalize interactions and offerings for individual customers, thereby enhancing customer satisfaction and brand loyalty. [1].

2. Materials and Methods

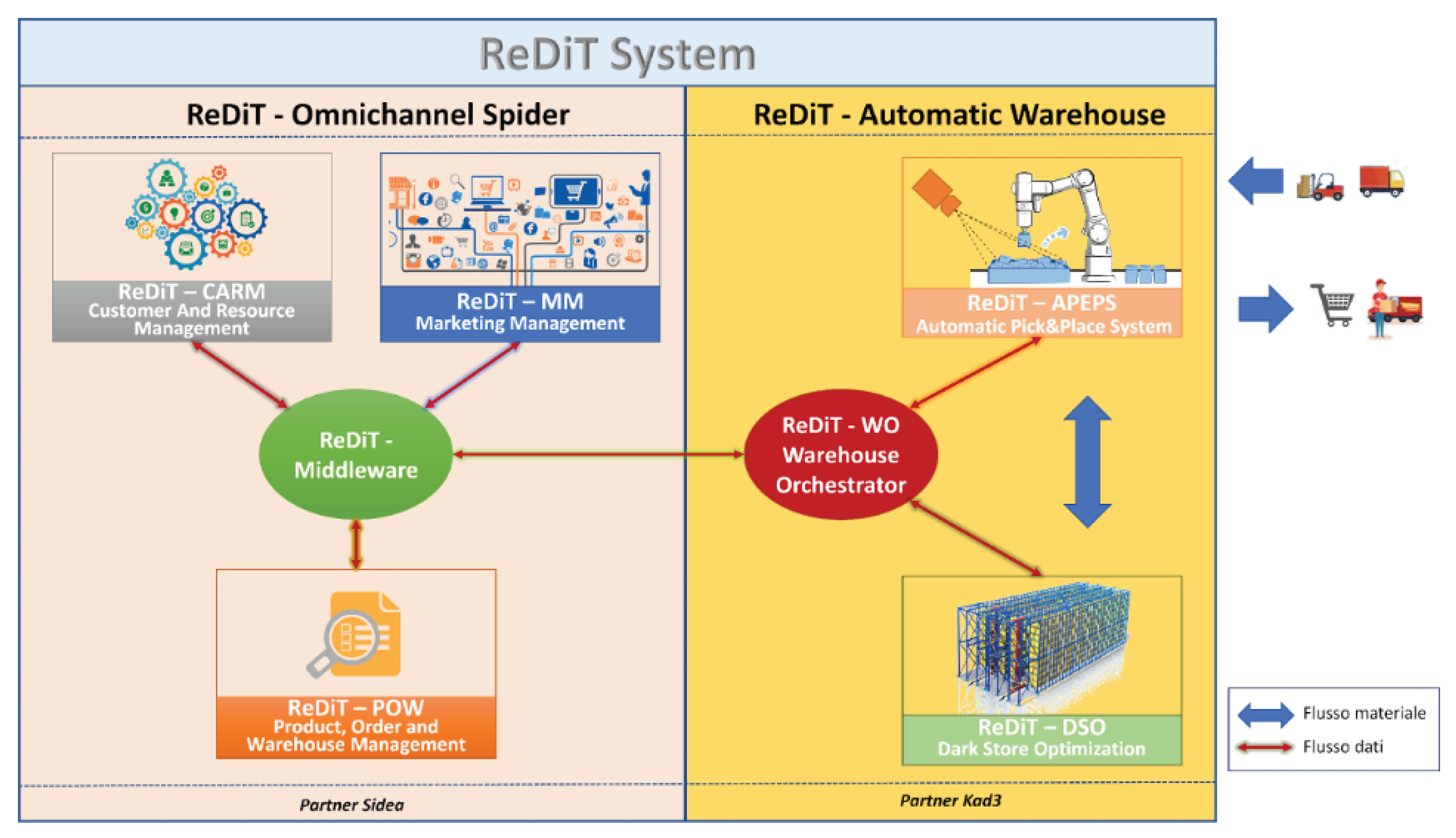

2.1. ReDiT Proposal

- The "ReDiT Omnichannel Spider" (ReDiT-OS) macro-system is designed to deploy a stand-alone architecture supporting a "unified commerce" sales solution capable of managing cross-channel transactions;

- The "ReDiT Automatic Warehouse" (ReDiT-AW) macro-system is tailored to implement a dedicated solution for dark-store picking in e-commerce. The framework consists of an automated system comprising a picking warehouse and conveyor belts for package handling, designed for streamlining and automating the process of picking and order fulfillment.

2.1.1. Architectural Overview of the "ReDiT" Solution

ReDiT Omnichannel Spider

- ReDiT Middleware. The central component driving the system and serving as the pivotal orchestrator for facilitating communication among different units of the framework. This architectural unit enables efficient automation of processes, reducing human error and ensuring optimal connectivity between different components.

- ReDiT Product, Order and Warehouse Management (ReDiT-POW). This subsystem has the ability to autonomously and centrally manage: product, order and warehouse data in the specific context. Core modules include the Product Information Management (PIM) dedicated to a structured and organized aggregation of product information, the Order Management System (OMS) for centralized order processing, and the Warehouse Management System (WMS) dedicated to the operational management of physical flows in warehouses.

-

ReDiT Customer and Resource Management (ReDiT-CARM). Implementing omnichannel approaches in the "Health & Pharma" industry requires rigorous integration and synchronization of data across various communication and distribution channels. In order to ensure a seamless and personalized shopping experience across all channels, the adoption of centralized data management becomes mandatory. Data centralization, particularly within the health and pharmaceutical sectors, is acknowledged as a crucial requirement for enhancing operational efficiency, guaranteeing personalized customer experiences, ensuring regulatory compliance and protecting data security and integrity. In this scenario, the ReDiT-CARM subsystem is designed to synchronize and centralize relevant data, including customer data, with the aim of enabling automatic customer recognition and optimizing administrative, accounting, and customer service activities. This subsystem includes:

- -

- the Customer Relationship Management (CRM) to manage customer interactions across various channels;

- -

- the Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) for centralized management of inventory engagement, accounting, and administrative tasks;

- -

- the Retail Omnichannel (RO) dedicated to recording transactions at checkout, facilitating omnichannel sales processes, improving inventory management, and elevating both in-store operational efficiency and the overall customer shopping experience. The inclusion of the RO module constitutes a significant transformation of the traditional point-of-sale paradigm.

- ReDiT Marketing Management (ReDiT-MM). This module supports advanced omnichannel marketing management, by incorporating other submodules, such as the Loyalty Engine dedicated to omnichannel customer recognition and retention. Additionally, the ReDiT-MM includes the Marketing Automation and Marketing Intelligence modules designed to automate and analyze marketing campaigns across multiple distribution channels.

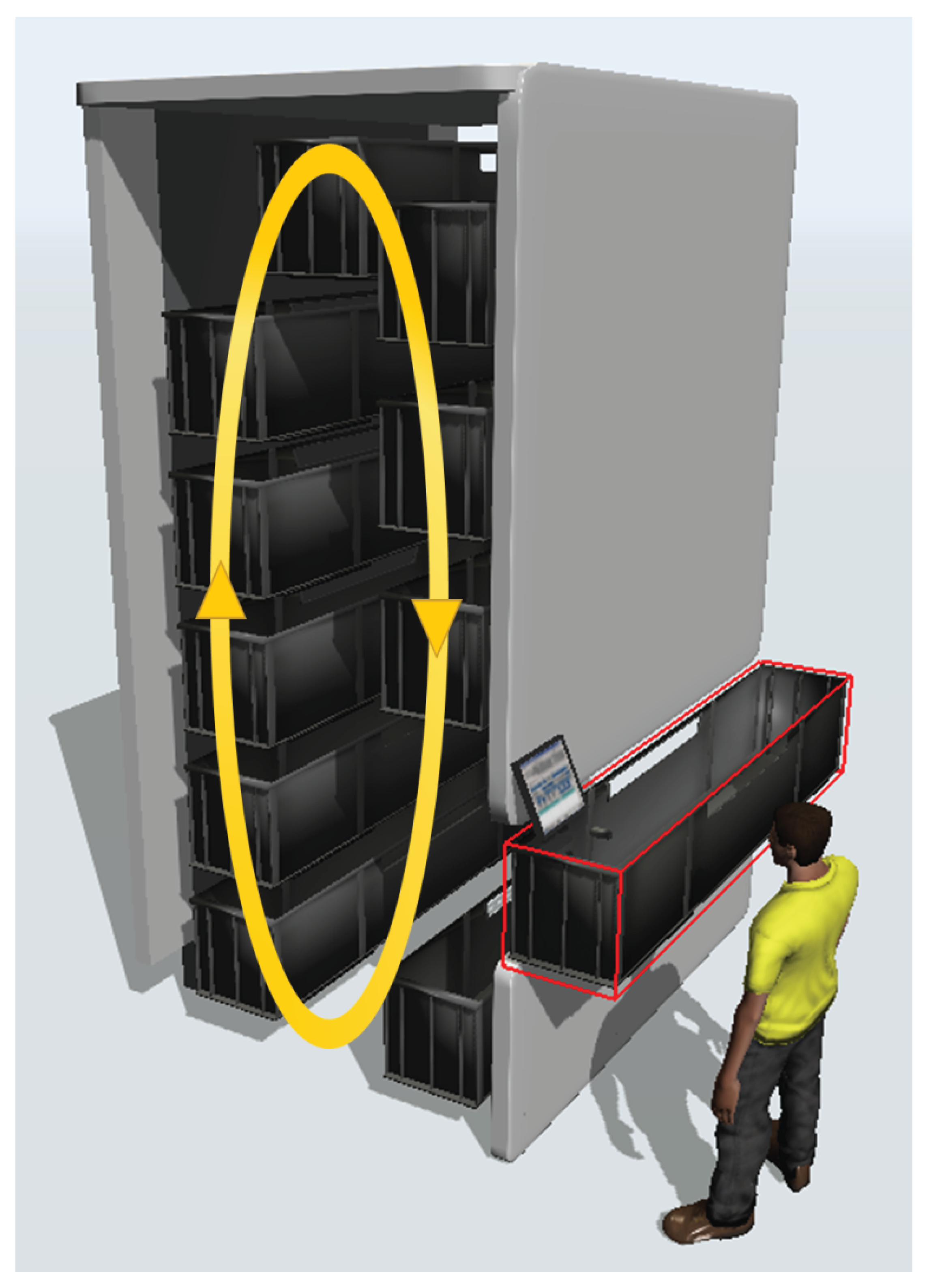

ReDiT Automatic Warehouse

- ReDiT Automatic Pick&Place System (ReDiT-APEPS). This component includes a vision system able to identify the precise location of individual products within the handling area in order to pick them up and create the order cart. In addition, this system includes a robotic arm equipped with the capability to receive commands for picking and positioning products associated with a specific order.

- ReDiT Dark Store Optimization (ReDiT-DSO). This subsystem is critical for the long-term optimization of the time associated with the order fulfillment process. This module is also equipped with an artificial intelligence system that identifies the best configuration to store individual products based on customers’ preferences and their typical spending patterns. Warehouse optimization constitutes an essential element of the ReDiT system because it directly affects the speed of order fulfillment and total service costs.

-

ReDiT Warehouse Orchestrator (ReDiT-WO). As the core of the entire ReDiT Automatic Warehouse, it is responsible for coordinating the actions of the ReDiT-DSO and ReDiT-APEPS according to the requests communicated by the ReDiT Middleware. In particular, two basic tasks are in charge to the ReDiT-WO:

- -

- Receiving orders from the ReDiT-Middleware module and coordinating the picking operations from warehouse and the order preparation by means of the ReDiT-APEPS subsystem.

- -

- Defining product pickup and storage schedules by coordinating ReDiT-APEPS and ReDiT-DSO.

According to the architecture of aforementioned solution, the ReDiT-Middleware and the ReDiT-WO subsystems represent the core nodes of the ReDiT system architecture as they provide the integration and coordination of diverse modules regardless of the type of product to be handled and the channels used. The proper development of these two subsystems allows the entire framework to handle with different volumes of orders/goods and different product families (e.g., belonging to the pharmaceutical, electronic, and food fields). Therefore, a well-designed architecture for these modules provides the ReDiT system with flexible and scalable characteristics.

2.1.2. Integrated Technical Architecture of the "ReDiT Omnichannel Spider"

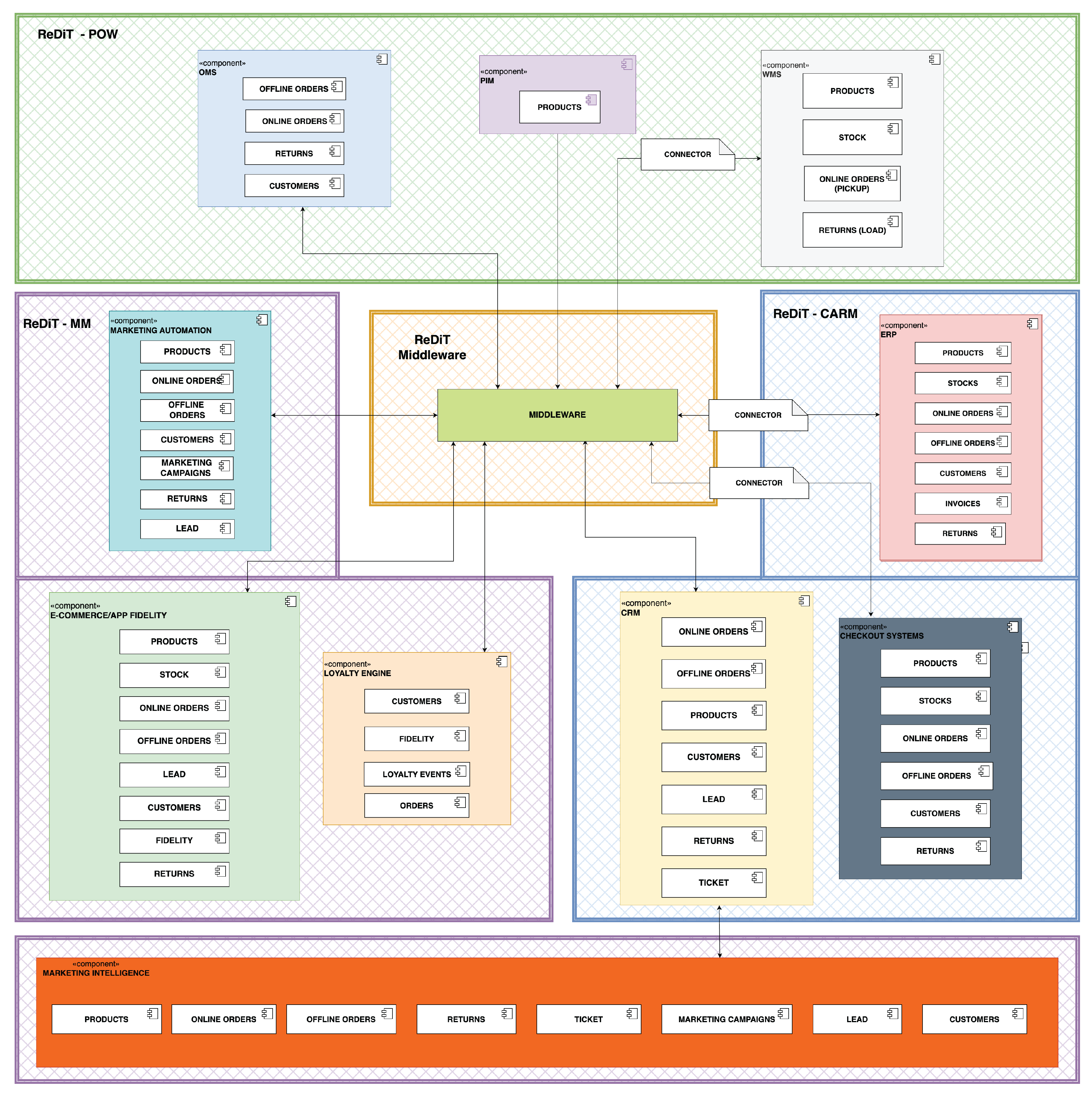

2.1.3. Component Diagram

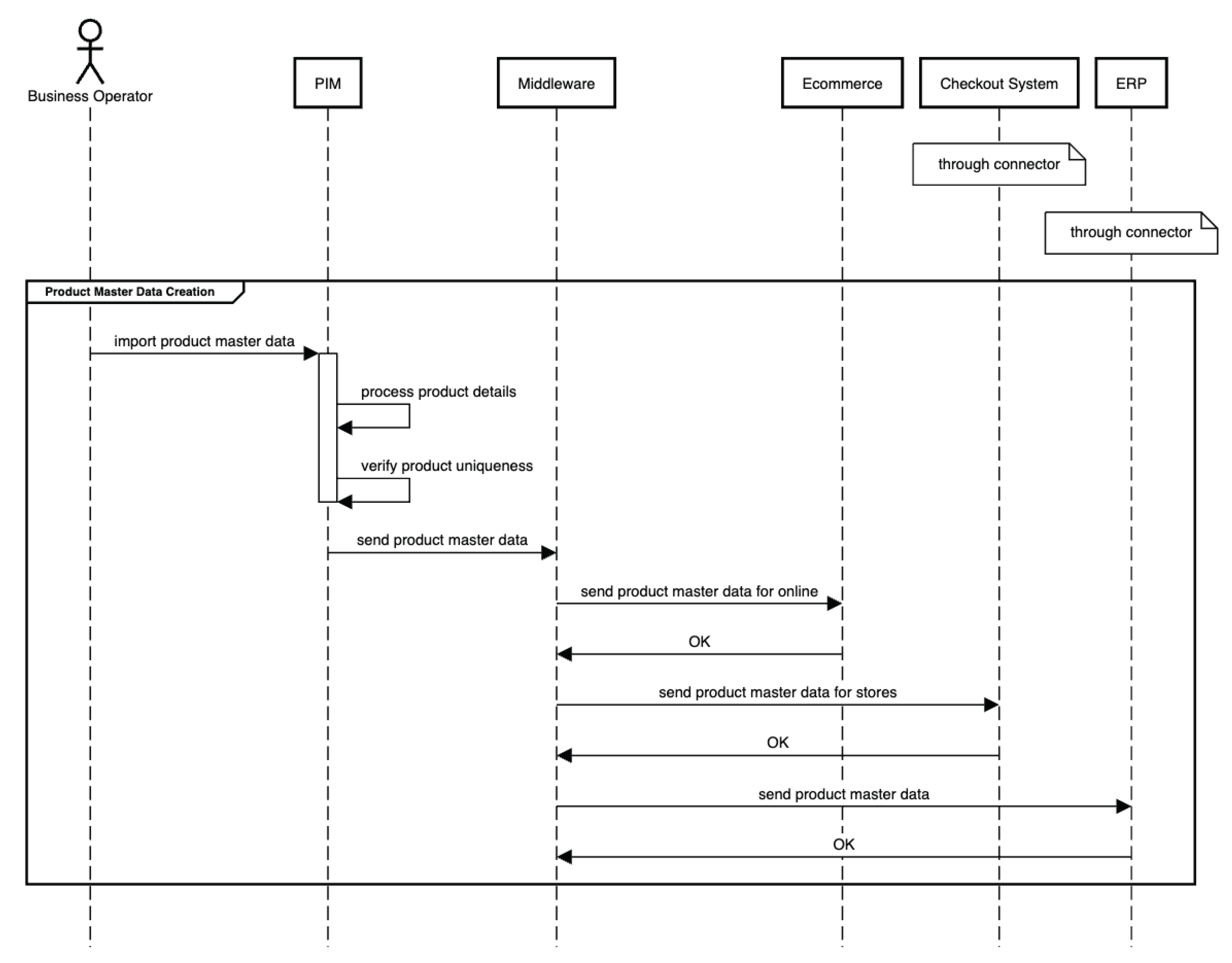

- Unidirectional flow from the PIM. In the proposed omnichannel system, the PIM establishes a unidirectional flow of communication with the Middleware. This one-way communication enables the PIM to consistently transmit product data, facilitating efficient product lifecycle management across all relevant business components.

- Two-way flow from/to the WMS. This flow enables a two-way exchange of data which is critical for efficient management of warehouse operations. The Warehouse Management System (WMS) receives relevant information concerning availability, inventory, and goods movements. It also sends inventory updates, thereby ensuring synchronized and streamlined warehouse management.

- Two-way flow to/from ERP. This two-way communication enables automatic stock updates as a response to sales or returns. This synchronism aims to prevent undesirable scenarios, such as out-of-stock sales or overstocking. Two-way flow to/from ERP also includes the communication of pivotal aspects such as internal movement of goods and synchronization of accounting/administrative documents, contributing to an optimized management of business activities.

- Two-way flow to/from the cash system. Bidirectional communication between the cash system and other components is essential for delivering an omnichannel shopping experience and for optimizing business operations. This communication allows both online and offline sales data (including returns) and customer master records to be synchronized between the components in charge.

- Two-way flow to/from e-commerce. The flow to/from e-commerce allows for automatic sharing of customer data, leads, orders, and returns made online. This data sharing facilitates customer service in accessing up-to-date information, making it easier to handle inquiries, resolve problems, and provide personalized customer service. Moreover, this communication is crucial for implementing omnichannel loyalty programs and effectively managing loyalty activities. Synchronizing this data with analytics and monitoring tools is also essencial for obtaining comprehensive insights into system performance and user experience on e-commerce platforms. Furthermore, sharing this data is important for crafting targeted campaigns, enhancing customer engagement, and optimizing online sales strategies.

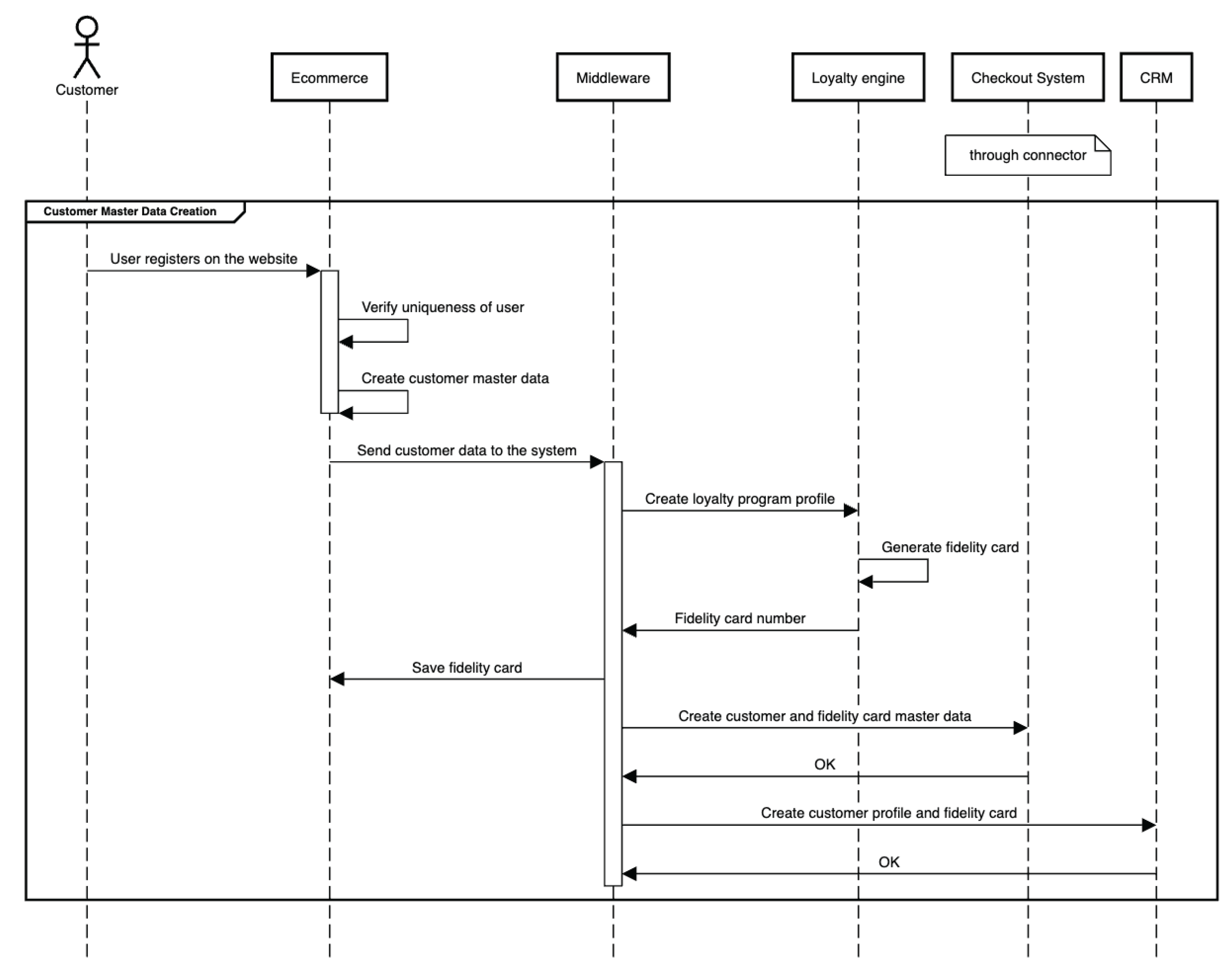

- Two-way flow to/from the Loyalty Engine. Two-way communication with the Loyalty Engine system plays a crucial role in the effective creation and management of loyalty programs. Indeed, the Loyalty Engine imports and synchronizes customer data as it enables the creation of detailed customer profiles and the implementation of loyalty programs. On the other hand, the Loyalty Engine provides the data needed to create interactive reports and dashboards in the Marketing Intelligence system. These reports include key metrics such as program participation, points earned and redeemed, popular rewards, and purchase trends. Such two-way communication facilitates analysis of customer purchasing activities, segmentation, identification of effective loyalty models, and evaluation of loyalty program performance.

- Two-way flow to/from CRM. Automatic data sharing to/from CRM includes detailed information on customer contacts, interactions, purchase history, and leads generated by marketing activities. This communication also facilitates the automation of marketing campaigns, empowering the creation of lead nurturing campaigns that automatically send personalized emails tailored to the actions and attributes of contacts registered in the CRM, thereby improving the generation of qualified leads and enhancing campaign effectiveness. Additionally, the streamlining of lead scoring management enables the assessment of lead quality derived from marketing initiatives. Data on leads collected within the Marketing Automation system can be seamlessly transferred to the CRM, where it undergoes scoring. This approach assists in identifying the most promising leads and improving sales opportunity management processes.

- Two-way flow to/from marketing intelligence system and marketing automation tool. The Marketing Automation platform collects data on customer behaviors and interactions, such as email opens, link clicks, site visits, and conversions. This data are then used to construct comprehensive contact profiles, enriching the understanding of individual customers. Marketing Intelligence leverages the acquired data to conduct in-depth analysis, identify behavior trends, analyze the customer journey, identify customer segments and discover cross-selling and upselling opportunities. Data communication between the Marketing Automation system and the Marketing Intelligence system enables the personalization of communications based on the acquired data and insights. Targeted messages and offers can be created to improve engagement, increase conversions and develop deeper customer relationships. The integration also enables automated data-driven decision making, such as sending follow-up messages, scoring leads, and launching specific campaigns in response to customer behavior. Finally, communication between the two components enables accurate measurement of the performance of marketing activities. Data collected is used to calculate crucial KPIs such as conversion rate and ROI of campaigns, providing clear evidence of the effectiveness of marketing strategies and guiding future decisions.

2.1.4. Analysis of the Technical Architecture and operational processes within the "ReDiT Automatic Warehouse"

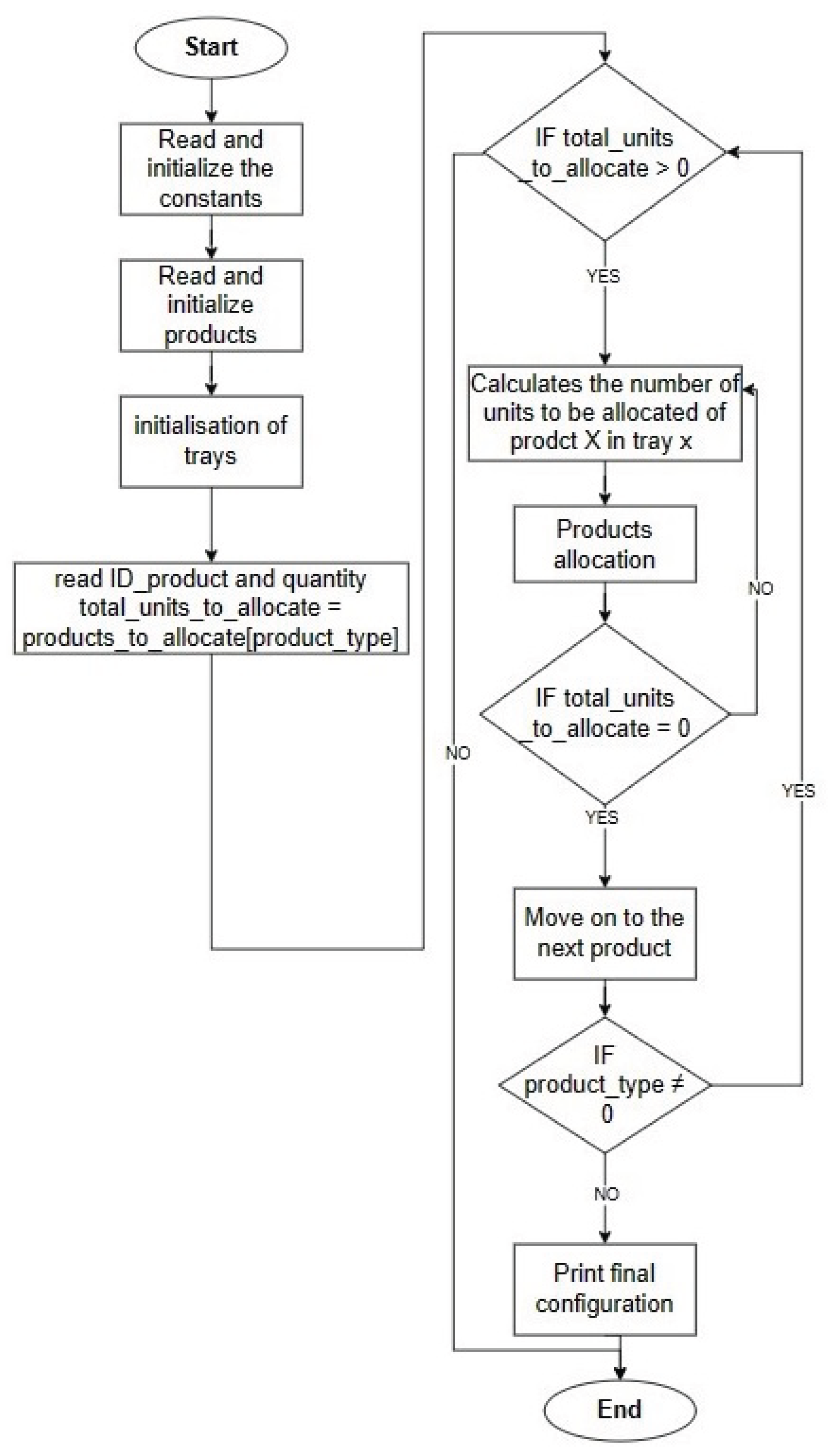

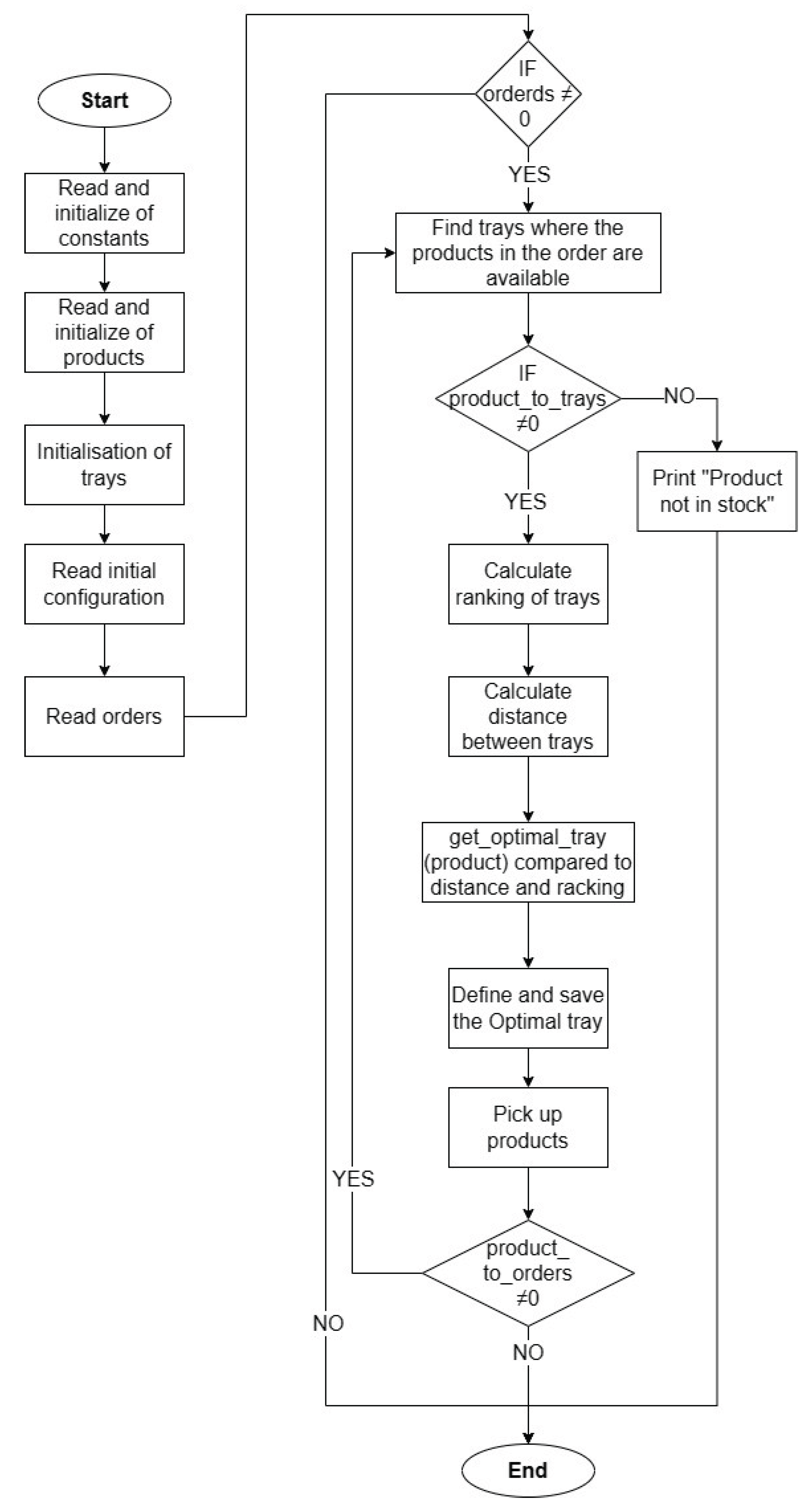

2.2. Algorithmic Approach

Methodology

Allocation phase

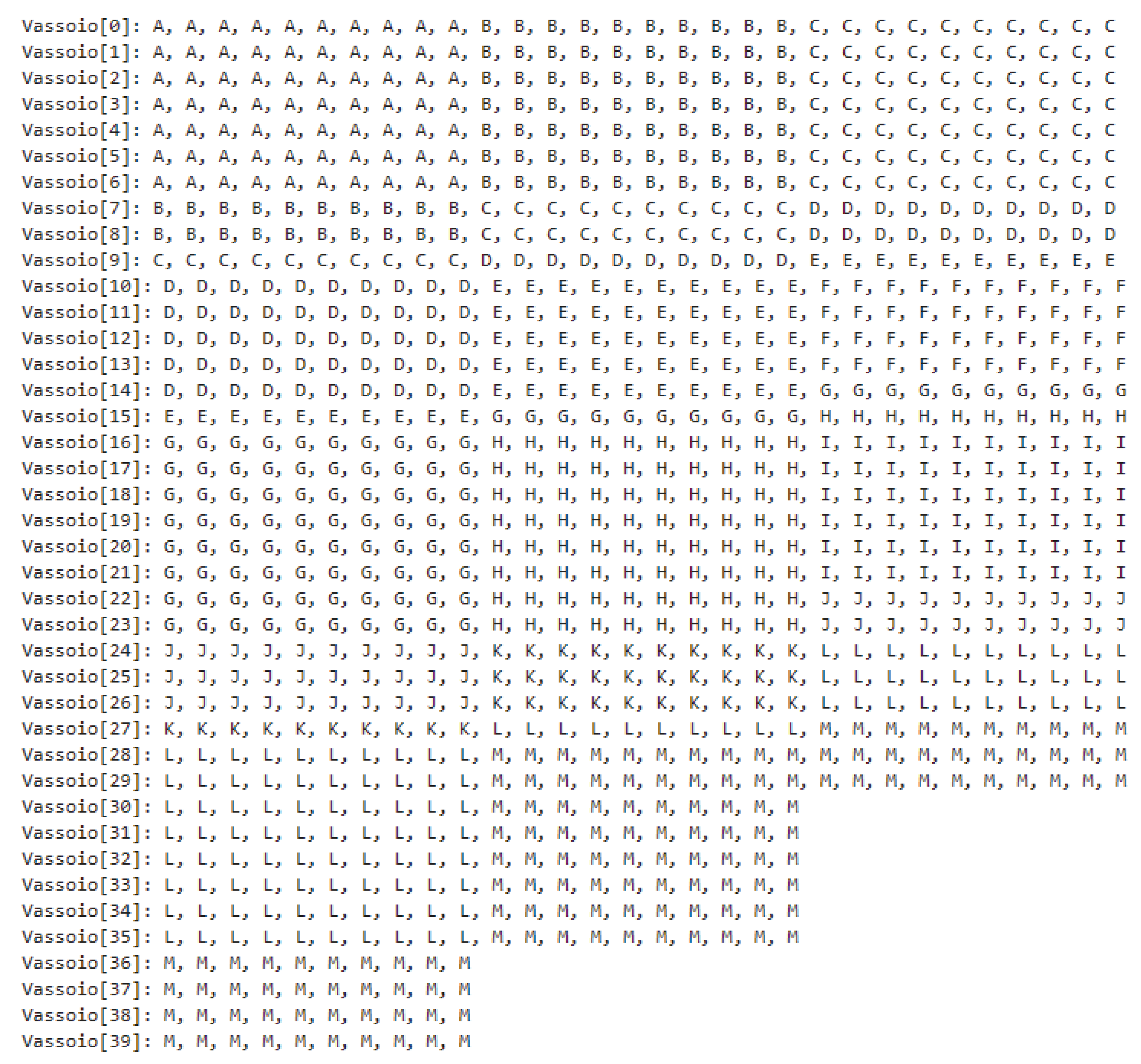

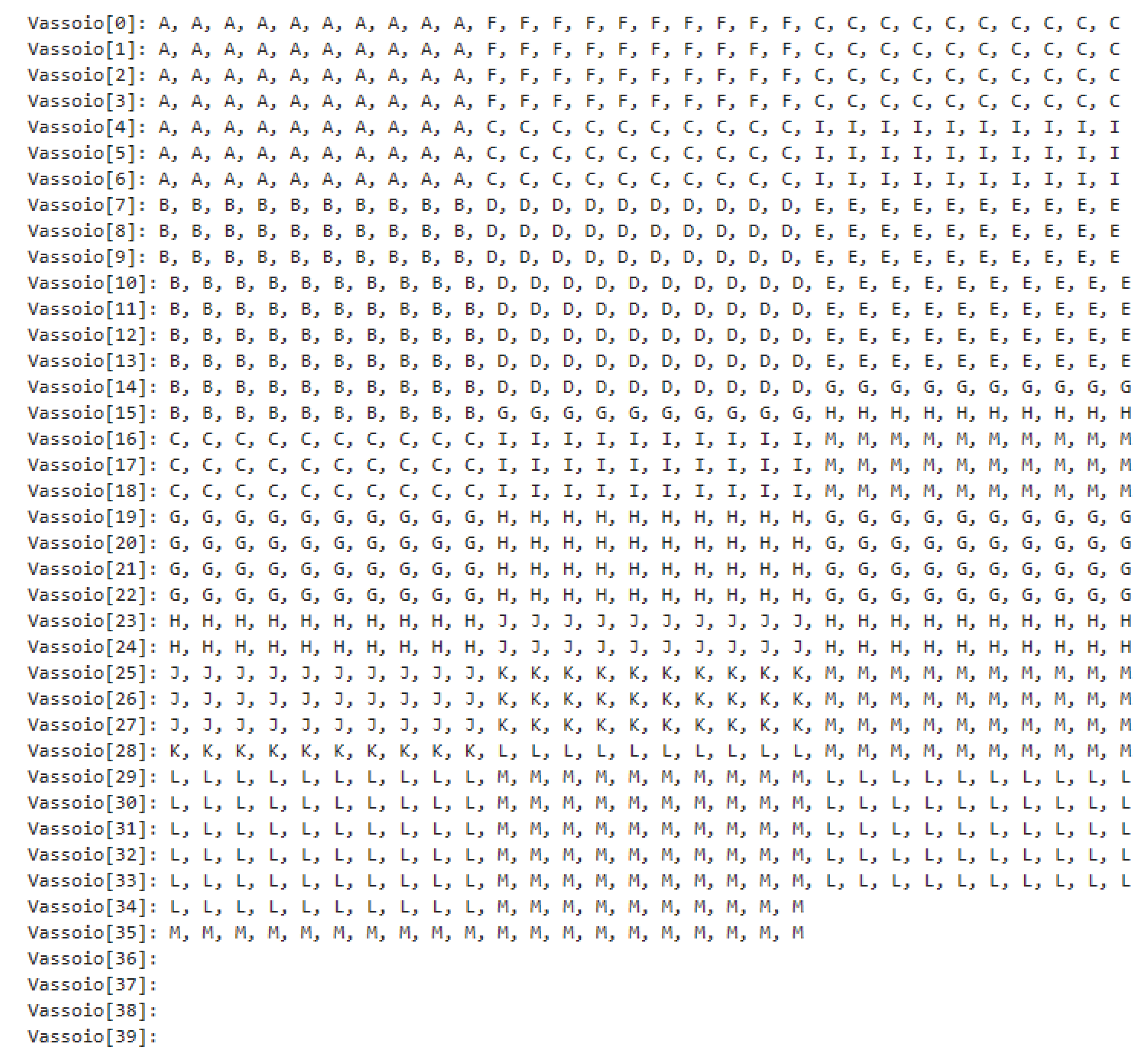

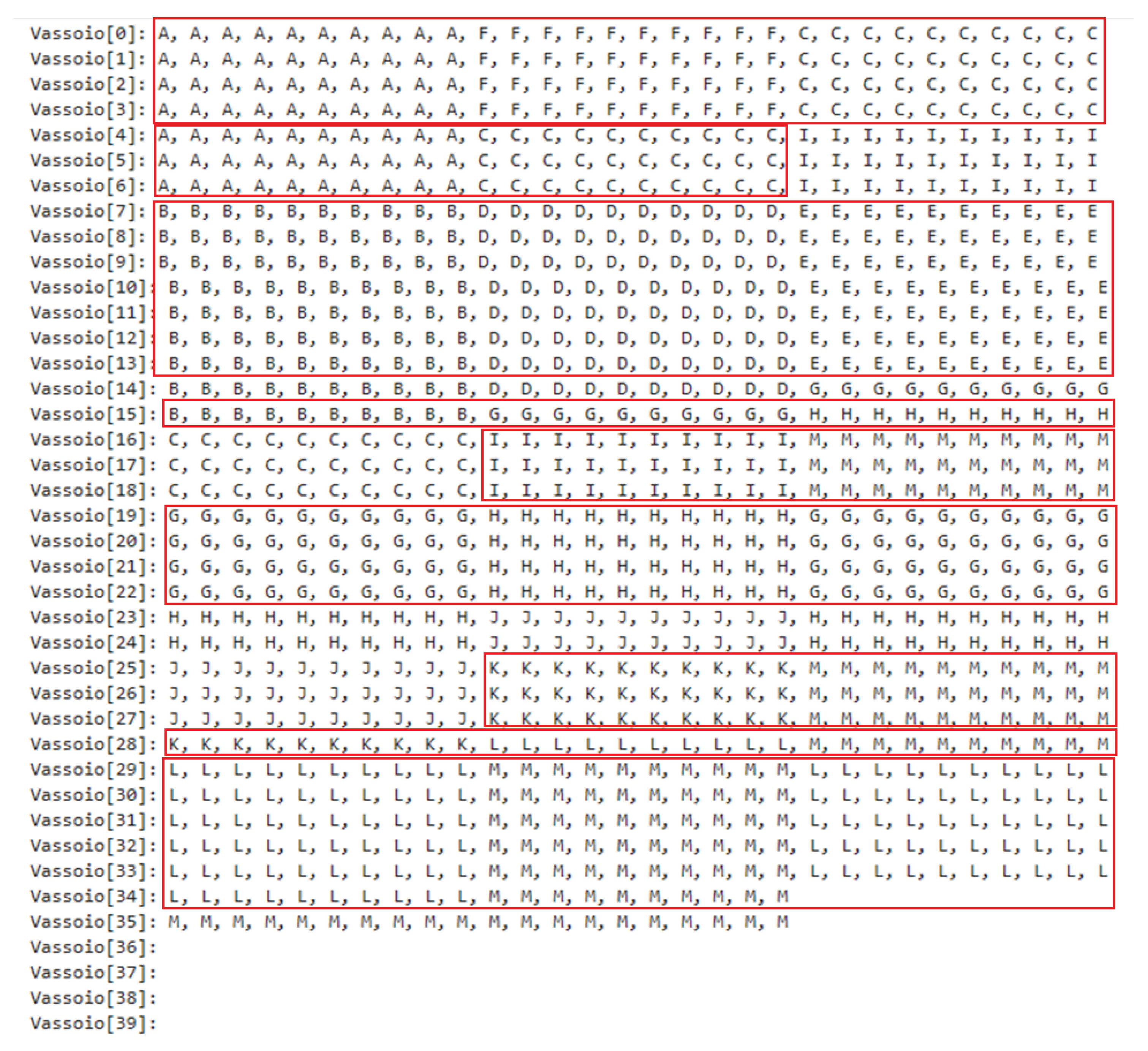

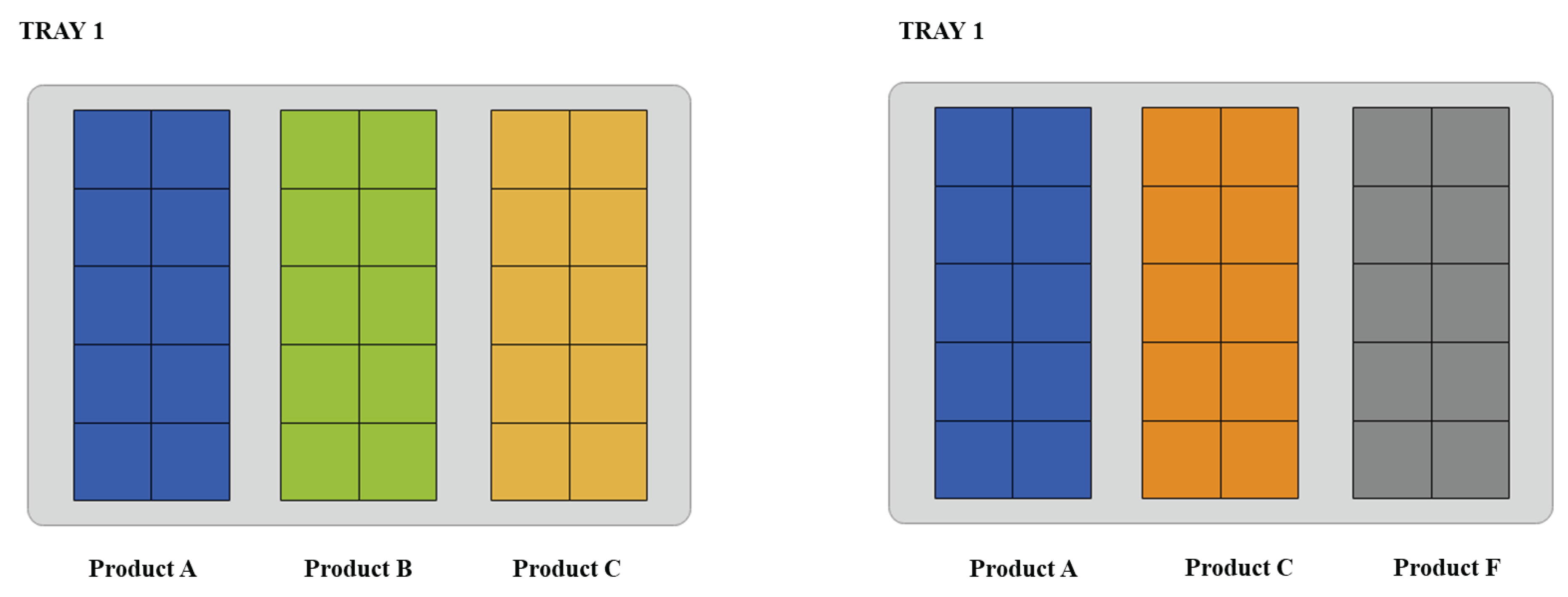

- A maximum of 3 types of products can be placed in each tray.

- A maximum of 10 units can be inserted for each product type.

- tray_capacity: 30 (maximum capacity of a single tray)

- products_per_type: 10 (number of products per type in a single tray)

- types_per_tray: 3 (number of product types in a single tray)

- num_trays: 40 (number of trays)

- Initialization of Trays: An array of strings representing the trays is created using list comprehension. Each element has the form "Tray[i]", where i is the tray index. This initialization is based on the variable num_trays.

- A dictionary named allocated_products is created with keys representing the trays and initially empty values (empty lists) representing the products assigned to each tray.

- A while loop is used to assign products to trays until there are still products to allocate. The tray chosen for allocation is determined using the min function, which selects the tray with the fewest products already assigned.

- The remaining space in the tray (space_left) is calculated, which is the maximum capacity of the tray minus the length of the list of products already assigned to the tray. The number of products to allocate (to_allocate) is then calculated as the minimum between the maximum quantity of products per type, the remaining quantity of that type of product, and the remaining space in the tray. If to_allocate is equal to the maximum quantity of products per type, the allocation is made, and the remaining quantity of that type of product is updated.

- If there are correlated products defined in the correlations variable, a similar check is made to allocate correlated products if there is available space in the tray.

- The final arrangement of products in the trays is printed, showing the products assigned to each tray.

- A dictionary named initial_configuration is created to represent the initial configuration by copying the allocated_products dictionary.

- Definition of he function "calculate_tray_time": this function computes the total movement time between trays, considering the round-trip time as well. If the previous tray_index is None, it indicates the first tray, and the round-trip time is calculated solely based on the tray_index. If the previous tray_index is not None, it calculates the movement time between the two trays and adds the round-trip time.

- Use of defaultdict for allocation_times: defaultdict is employed to manage the allocation_times dictionary, which automatically initializes values to zero for new keys.

- Iteration over products in unique_products_list: Iteration is based on the sorted list unique_products_list, which contains all the products present in the trays.

- Calculation of allocation times for each product: The code iterates through the trays, and for each product, it calculates the allocation time using the calculate_tray_time function and adds the cobot time (cobot_time). Cobot_time is the time to perform the product allocation task, assumed to be carried out by a cobot. The total time for each product is then added to the allocation_times dictionary.

Picking Phase

- all_products: a set of all products present in the trays.

- product_to_trays: a dictionary mapping each product to the trays where it is present.

- tray_to_quantities: a dictionary mapping each tray to a Counter object that tracks the quantities of each product in the tray.

- tray_ranking: this sorts the trays in descending order according to their tray ranking (tray_ranking). Essentially, trays with higher rankings, which have been frequently selected in the past, are positioned at the top of the list.

- tray_distance: in cases where there is a tie in the ranking, trays are organized based on the distance between the current tray (current_tray_force_low) and the tray under consideration (x). This preference is designed to select the tray that is closest to the current tray.

- total_time: A variable to track the total time spent in order picking.

- current_tray: The current tray from which the picking sequence starts.

- visited_trays: A set to keep track of the trays already visited during picking.

- sequence: A list to record the picking sequence, containing tuples with information about the tray and associated products.

3. Results

3.1. Operational Processes and Data Flows in the "ReDiT Omnichannel Spider" Corporate Macro-System

Creating Product Master Data

Creating Omnichannel Customer Master Data

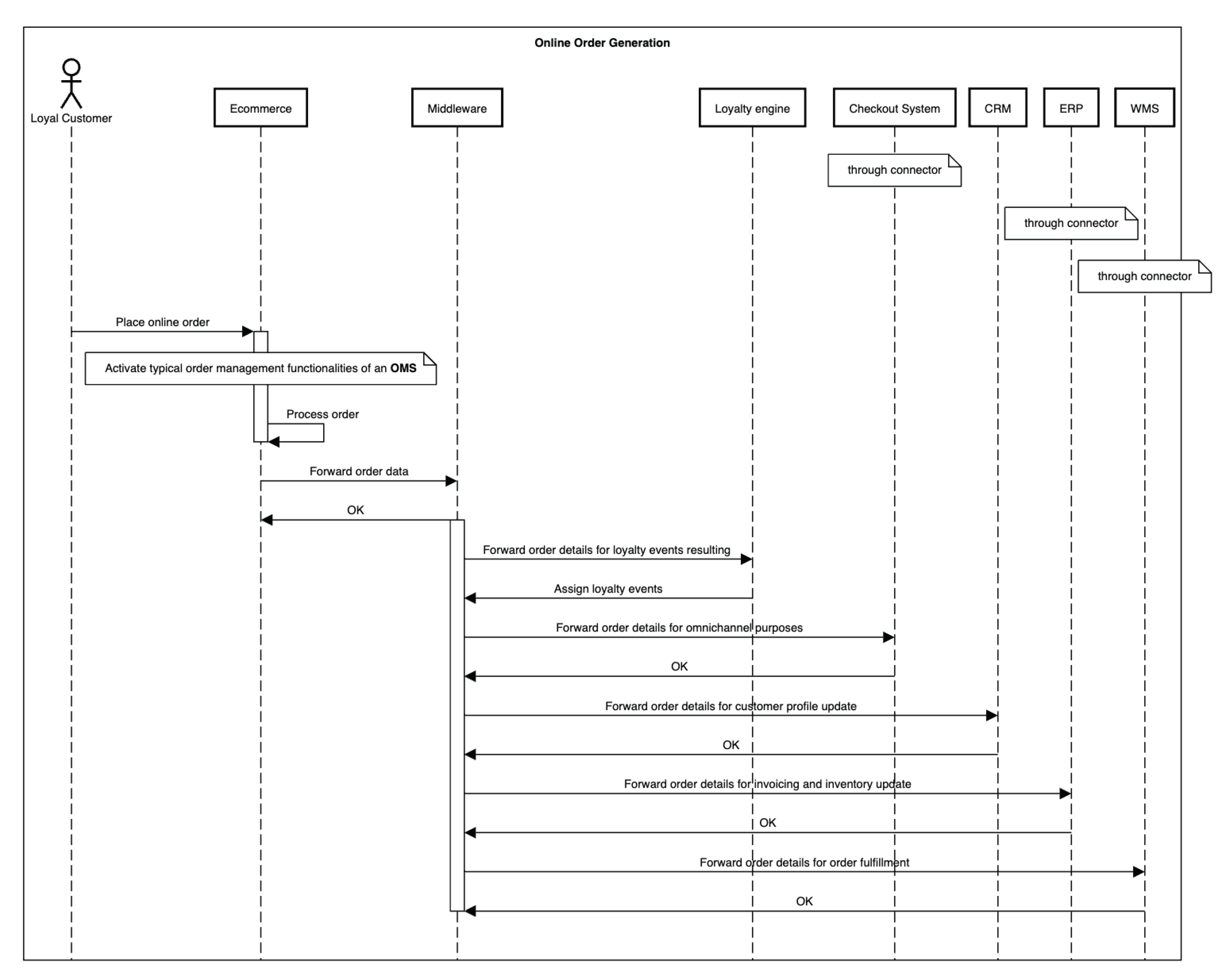

Online Order Generation, fulfillment and delivery

Offline Order Creation and Management

Return Request Management.

-

Authorization of the return request The flow is composed by the following steps:

- The loyal customer submits a return request directly from their e-commerce private area.

- The e-commerce handles the request.

- The request data is transmitted to the components responsible for handling it, including the loyalty engine, so that the the loyalty data associated with that order are updated; to the cash system in order to achieve omnichannelity; to the ERP in order to update stocks and process accounting documents; to the CRM for updating the customer file.

- The e-commerce platform sends the data of the return order to the courier software which is responsible for generating the shipping label.

- The shipping label is transmitted to the e-commerce platform, and it becomes available in the customer’s private area where the customer can access and print the label to be used for preparing the pakage to be consigned to the designated shipper. This process simplifies the return procedure, allowing customers to facilitate return shipping without additional complexity.

-

Receiving the returned goods in the warehouse and generating the refund:

- After the loyal customer entrusts the returned items to the courier, the courier takes care of delivering them to the destination, which typically is the warehouse of the company that originally fulfilled the order.

- Once the goods are back at the warehouse, a company operator verifies their condition and suitability.

- Subsequently, the goods are loaded into the WMS for proper inventory management.

- Next, the operator accesses the ERP system to initiate the refund process for the customer.

- The return status is updated to "completed" and is notified to the pertinent component, such as the e-commerce platform, the cash system, and the CRM platform, ensuring that all systems are updated to the latest status of the return transaction.

Creating and Analyzing Marketing Campaigns

Service Ticket Creation and Management

Inventory generation and update

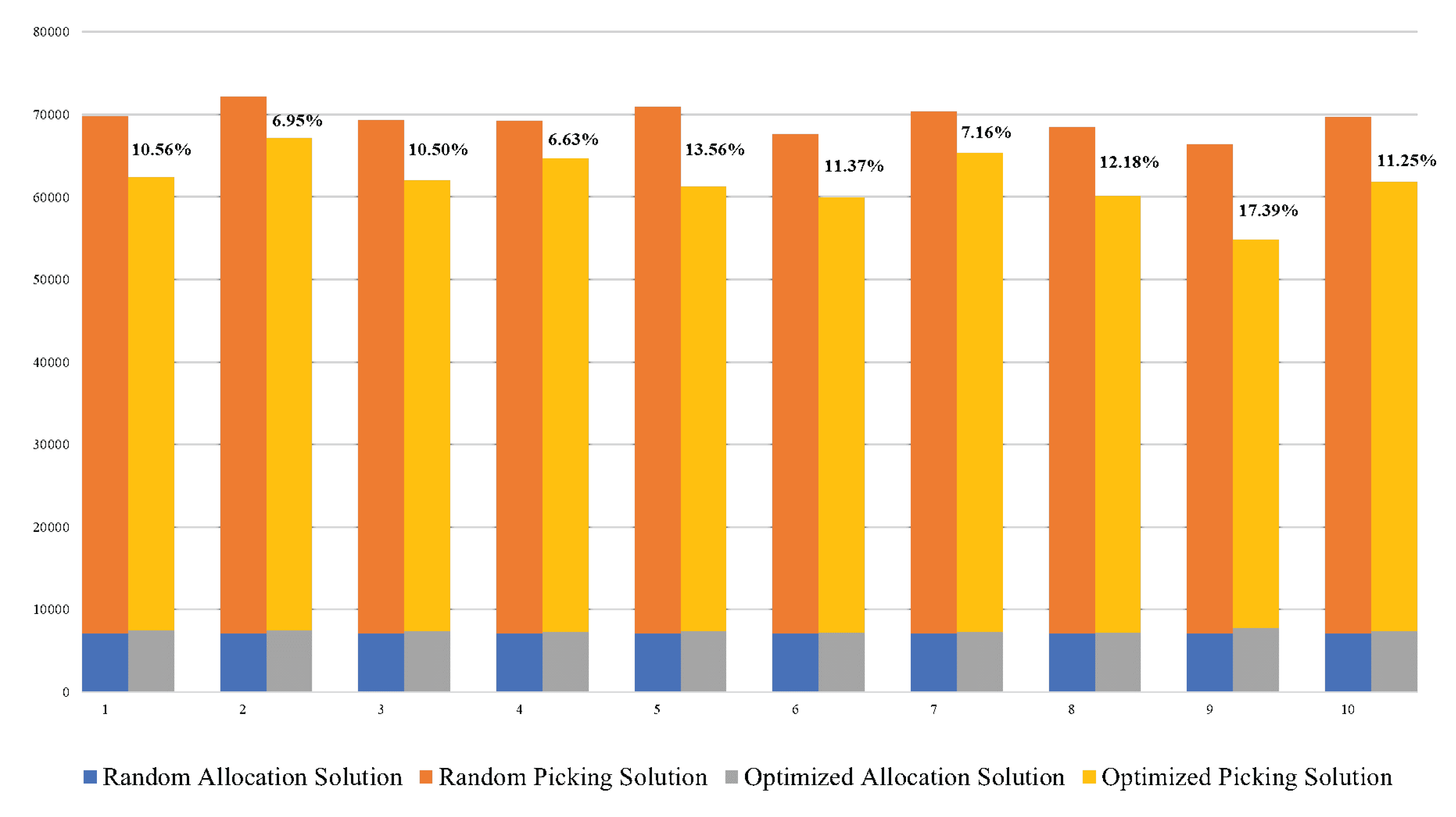

3.2. Performance Analysis of the "ReDiT Automatic Warehouse" Optimization Algorithm

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SLAP | Storage Location Assignment Problem |

| WMS | Warehouse Management System |

| ERP | Enterprise Resource Planning |

References

- Cotarelo, M.; Fayos, T.; Calderón, H.; Mollá, A. Omni-channel intensity and shopping value as key drivers of customer satisfaction and loyalty. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiberi, S. Impresa digitale: gestire contenuti, dati, tecnologia, organizzazione nell’era del cliente omnicanale; HOEPLI EDITORE, 2019.

- Akter, S.; Hossain, T.M.T.; Strong, C. What omnichannel really means? Journal of Strategic Marketing 2021, 29, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, A.; Holzapfel, A.; Kuhn, H. Distribution systems in omni-channel retailing. Business Research 2016, 9, 255–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.m.; Shin, S.y. Effects of omni channel characteristics on consumers’ perceived risk, attitude, and intention. The Research Journal of the Costume Culture 2018, 26, 346–359. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J.K.; Oh, M.O. Effects of omni-channel service characteristics on utilitarian/hedonic shopping value and reuse intention. Journal of Digital Convergence 2017, 15, 183–191. [Google Scholar]

- Caiazzo, G. Verso l’omnicanalità: la sfida all’integrazione tra lo shop online ed il punto vendita fisico. PhD thesis, Scuola universitaria professionale della Svizzera italiana, 2018.

- Simone, A.; Sabbadin, E. The new paradigm of the omnichannel retailing: key drivers, new challenges and potential outcomes resulting from the adoption of an omnichannel approach. International Journal of Business and Management 2018, 13, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiano, M. Omnichannel Marketing: Lo sviluppo di una piattaforma digitale nel fashion retail. PhD thesis, Scuola universitaria professionale della Svizzera italiana, 2019.

- Vianelli, D.; de Luca, P.; Pegan, G. ; others. La gestione della complessità nelle strategie omnicanale dell’impresa internazionale. In Contributi in onore di Gaetano Maria Golinelli; Rogiosi Editore, 2020; pp. 1299–1308.

- Bruzzi, S. Innovazione scientifica e innovazione imprenditoriale nel settore farmaceutico. Impresa Progetto-Electronic Journal of Management, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mennini, F.S.; Gianfrate, F.; Spandonaro, F. Dinamiche determinanti del settore farmaceutico in Europa. L’industria 2005, 26, 103–118. [Google Scholar]

- Asmare, A.; Zewdie, S. Omnichannel retailing strategy: a systematic review. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 2022, 32, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettucci, M.; D’Amato, I.; Perego, A.; Pozzoli, E. Omnicanalità: Assicurare continuità all’esperienza del cliente; Leading Management SDA, Egea, 2016.

- Saghiri, S.; Mirzabeiki, V. Omni-channel integration: the matter of information and digital technology. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 2021, 41, 1660–1710. [Google Scholar]

- Nobre, J.; Vita, J. Analysis of the dark store from the perspective of urban law. Rev. Direito Cid. 2021, 13, 1373–1392. [Google Scholar]

- Capital, V. Grocery Fulfillment and Dark Stores—Clear Aisles, Full Carts, Can’t Lose? WWW Document, 2020.

- Dablanc, L.; Morganti, E.; Arvidsson, N.; Woxenius, J.; Browne, M.; Saidi, N. The rise of on-demand ‘Instant Deliveries’ in European cities. Supply Chain Forum Int. J. 2017, 18, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, F.M. Tutto sui dark store: cosa sono e a cosa servono. LogisticaIT 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Makarchuk, M. The “dark side” of retail: industry challenges and specifics of inventory management for dark stores. https://www.leafio.ai/blog/the-dark-side-of-retail-industry-challenges-and-specifics-of-inventory-management-for-dark-stores/, 2023. Accessed: 2024-03-27.

- Deagor. Cos’è il Dark Store e perché sta prendendo piede? https://www.deagor.io/it/cose-il-dark-store-e-perche-sta-prendendo-piede/, 2021. Accessed: 2024-03-27.

- Uskonen, J. What’s the Key to Dark Store Profitability? https://www.relexsolutions.com/resources/the-keys-to-dark-store-profitability/, 2021. Accessed: 2024-03-27.

- Dukic, G.; Opetuk, T.; Lerher, T. A throughput model for a dual-tray Vertical Lift Module with a human order-picker. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 170, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Goetschalckx, M.; McGinnis, L. Research on warehouse operation: A comprehensive review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 177, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolaños Zuñiga, J.; Saucedo Martínez, J.; Salais Fierro, T.; Marmolejo Saucedo, J. Optimization of the Storage Location Assignment and the Picker-Routing Problem Using Mathematical Programming. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wu, Y.; Ma, W. Optimization of storage location assignment in an automated warehouse. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2021, 80, 103356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Méndez-Mediavilla, F.; Temponi, C.; Kim, J.; Jimenez, J. A Heuristic Storage Location Assignment Based on Frequent Itemset Classes to Improve Order Picking Operations. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Yan, D.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, G.; Wei, L.; Zhang, D.; Yu, A.; Chen, X. Digital twin-driven joint optimisation of packing and storage assignment in large-scale automated high-rise warehouse product-service system. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2021, 34, 783–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muppani (Muppant), V.; Adil, G. Efficient formation of storage classes for warehouse storage location assignment: A simulated annealing approach. Omega, Special Issue on Logistics: New Perspectives and Challenges 2008, 36, 609–618. [Google Scholar]

- Leon, J.; Li, Y.; Peyman, M.; Calvet, L.; Juan, A. A Discrete-Event Simheuristic for Solving a Realistic Storage Location Assignment Problem. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keung, K.; Lee, C.; Ji, P. Data-driven order correlation pattern and storage location assignment in robotic mobile fulfillment and process automation system. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2021, 50, 101369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, M.; Zaerpour, N.; de Koster, R. The impact of integrated cluster-based storage allocation on parts-to-picker warehouse performance. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 146, 102207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Sun, L.; Li, Z.; Li, W.; Cao, N.; Higgs, R. Study on a storage location strategy based on clustering and association algorithms. Soft Comput. 2020, 24, 5499–5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, R.Q.; Fan, K. Improving order-picking operation through efficient storage location assignment: A new approach. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 139, 106186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, K.W.; Chan, H.L. Data mining-based algorithm for storage location assignment in a randomised warehouse. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 55, 4035–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenc, A.; Lerher, T. PickupSimulo–Prototype of Intelligent Software to Support Warehouse Managers Decisions for Product Allocation Problems. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.; Smith, J. Gravity Clustering: A Correlated Storage Location Assignment Problem Approach. 2020 Winter Simulation Conference (WSC), 2020, pp. 1288–1299.

- Micale, R.; La Fata, C.; La Scalia, G. A combined interval-valued ELECTRE TRI and TOPSIS approach for solving the storage location assignment problem. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 135, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinelli, L.; Vivaldini, K.; Becker, M. Intelligent warehouse product position optimization by applying a multi-criteria tool. International Workshop on Robotics in Smart Manufacturing. Springer, 2013, pp. 137–145.

- Papcun, P. ; others. Augmented Reality for Humans-Robots Interaction in Dynamic Slotting “Chaotic Storage” Smart Warehouses. Advances in Production Management Systems. Production Management for the Factory of the Future. APMS 2019; Ameri, F.; Stecke, K.; von Cieminski, G.; Kiritsis, D., Eds. Springer, Cham, 2019, Vol. 566.

- Liu, J.; Liao, X.; Zhao, W.; Yang, N. A classification approach based on the outranking model for multiple criteria ABC analysis. Omega 2016, 61, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacramento Quintanilla, Ángeles Pérez, F.B.; Lino, P. Heuristic algorithms for a storage location assignment problem in a chaotic warehouse. Engineering Optimization 2015, 47, 1405–1422. [CrossRef]

- Amir Foroughi, Nils Boysen, S.E.; Schneider, M. High-density storage with mobile racks: Picker routing and product location. Journal of the Operational Research Society 2021, 72, 535–553. [CrossRef]

| ID-product | Quantity |

|---|---|

| A | 70 |

| B | 90 |

| C | 100 |

| D | 80 |

| E | 70 |

| F | 40 |

| G | 100 |

| H | 90 |

| I | 6 |

| J | 50 |

| K | 40 |

| L | 120 |

| M | 150 |

| Iterations | Allocation time (sec) | Picking time (sec) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7080 | 62675 |

| 2 | 7080 | 65115 |

| 3 | 7080 | 62280 |

| 4 | 7080 | 62175 |

| 5 | 7080 | 63850 |

| 6 | 7080 | 60535 |

| 7 | 7080 | 63310 |

| 8 | 7080 | 61420 |

| 9 | 7080 | 59320 |

| 10 | 7080 | 62600 |

| Iterations | Allocation time (sec) | Picking time (sec) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7485 | 54905 |

| 2 | 7490 | 59685 |

| 3 | 7330 | 54750 |

| 4 | 7300 | 57360 |

| 5 | 7375 | 53935 |

| 6 | 7195 | 52735 |

| 7 | 7260 | 58090 |

| 8 | 7195 | 52960 |

| 9 | 7730 | 47125 |

| 10 | 7325 | 54515 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).