Submitted:

06 April 2024

Posted:

08 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of PVDF Polymeric Membrane

2.3. PVDF UF Membrane Modification

2.4. Membrane Characterization

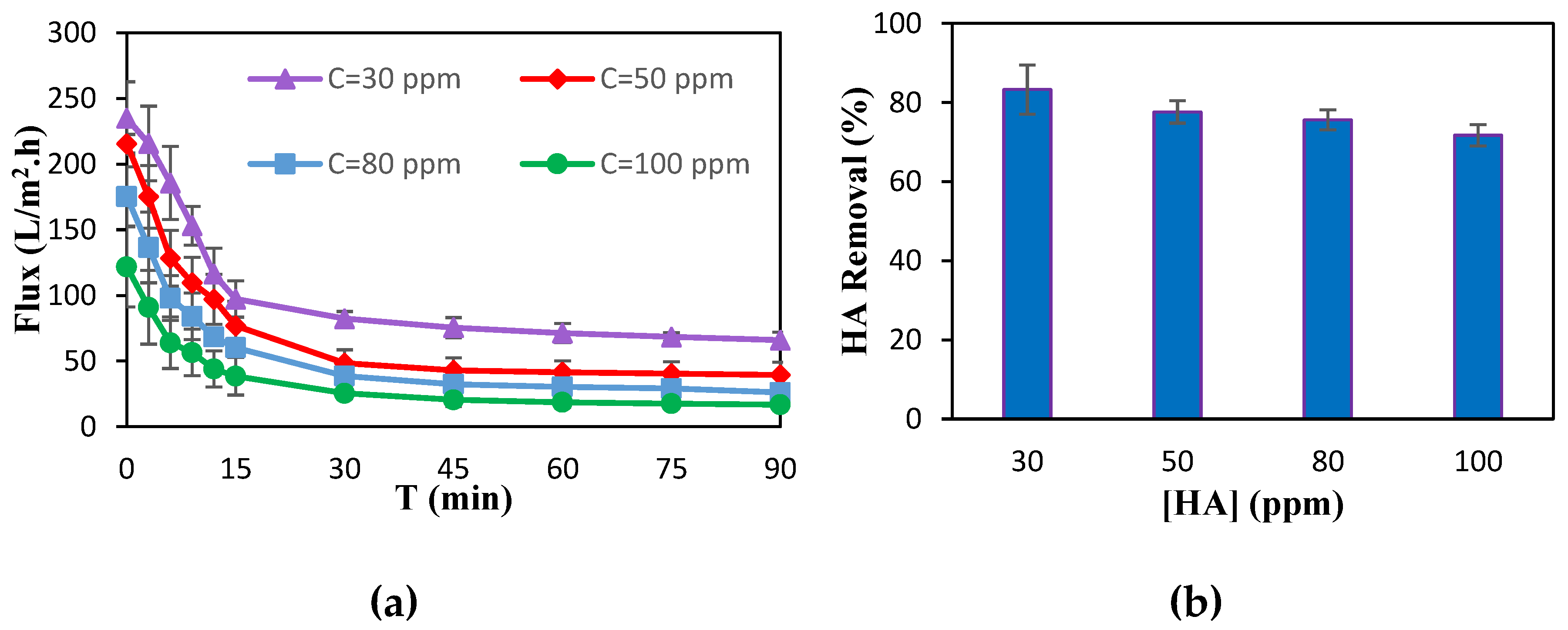

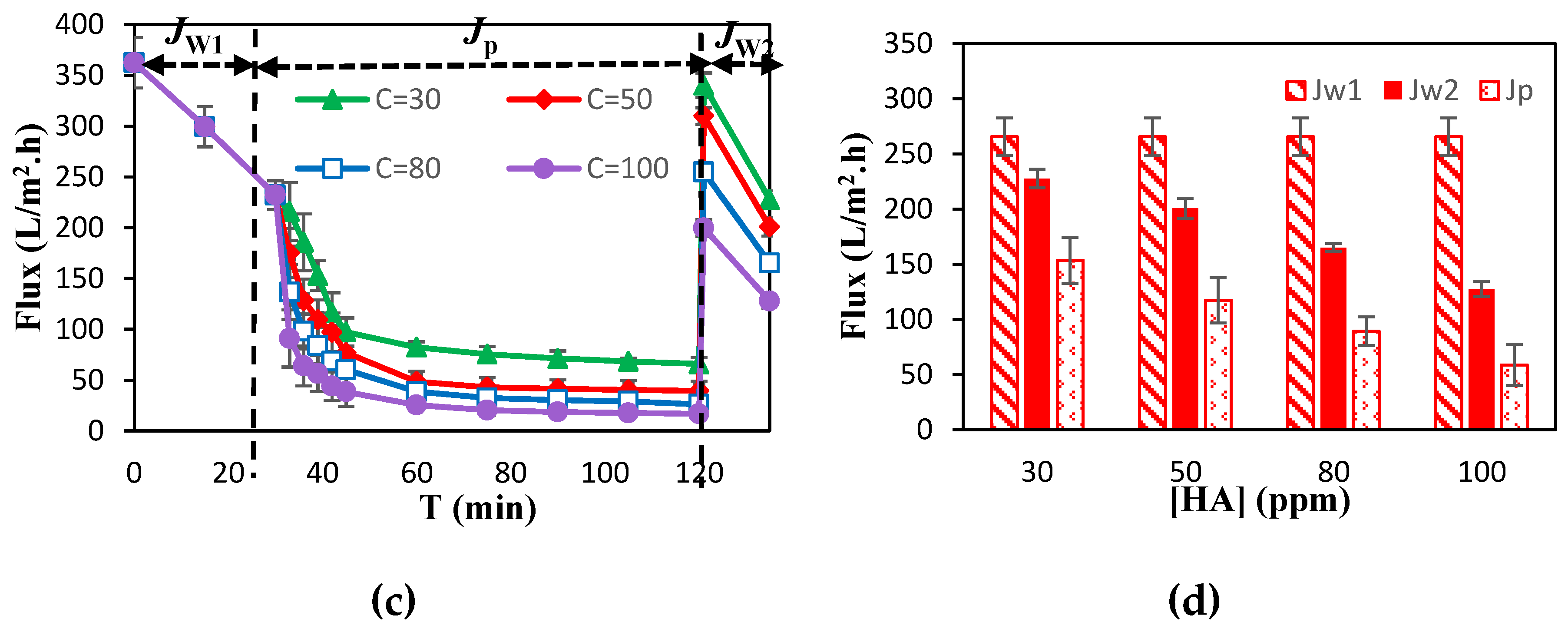

2.5. Preparation of Synthetic Wastewater and Determination of Effective Parameters

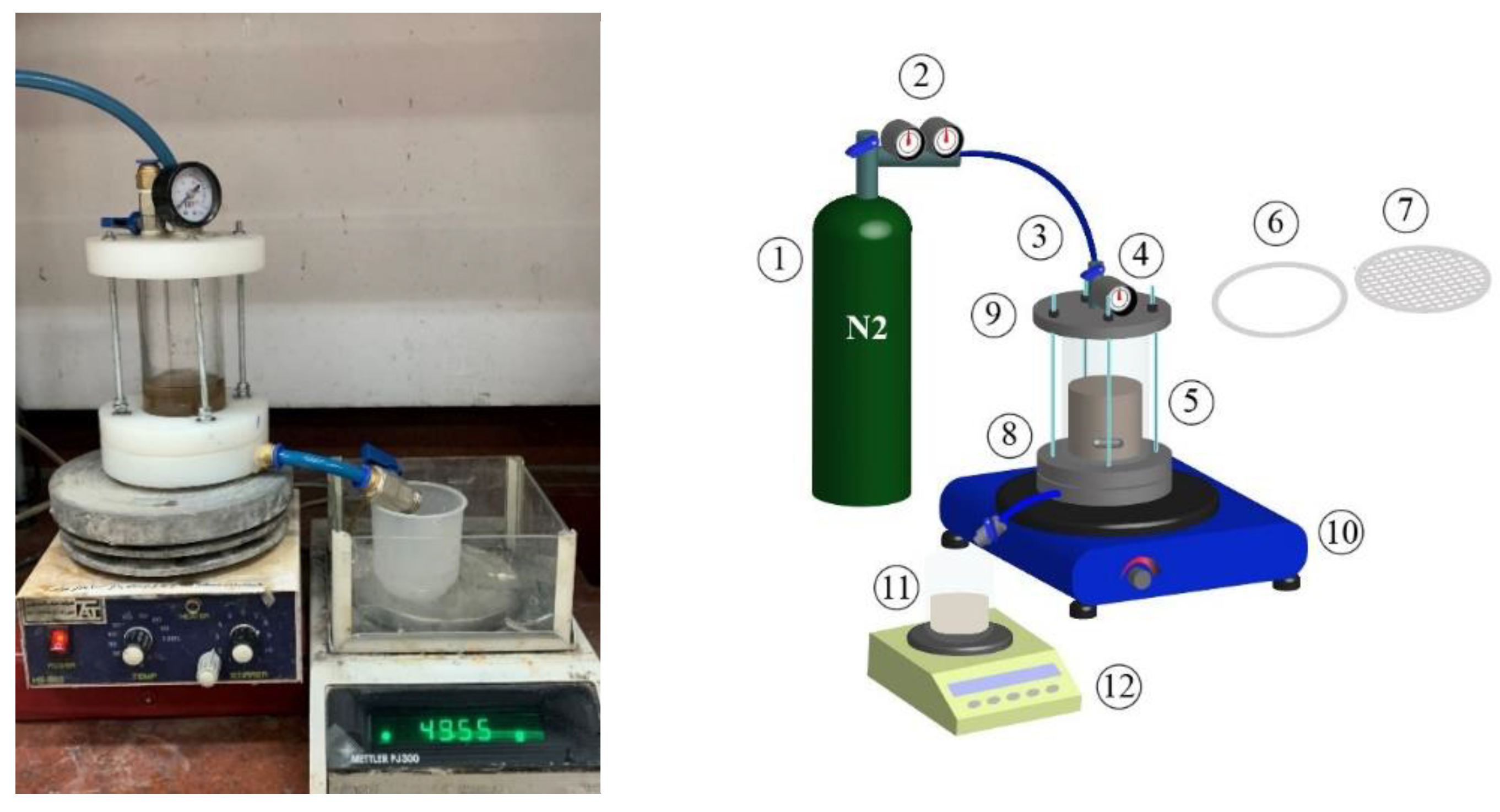

2.6. Filtration Test

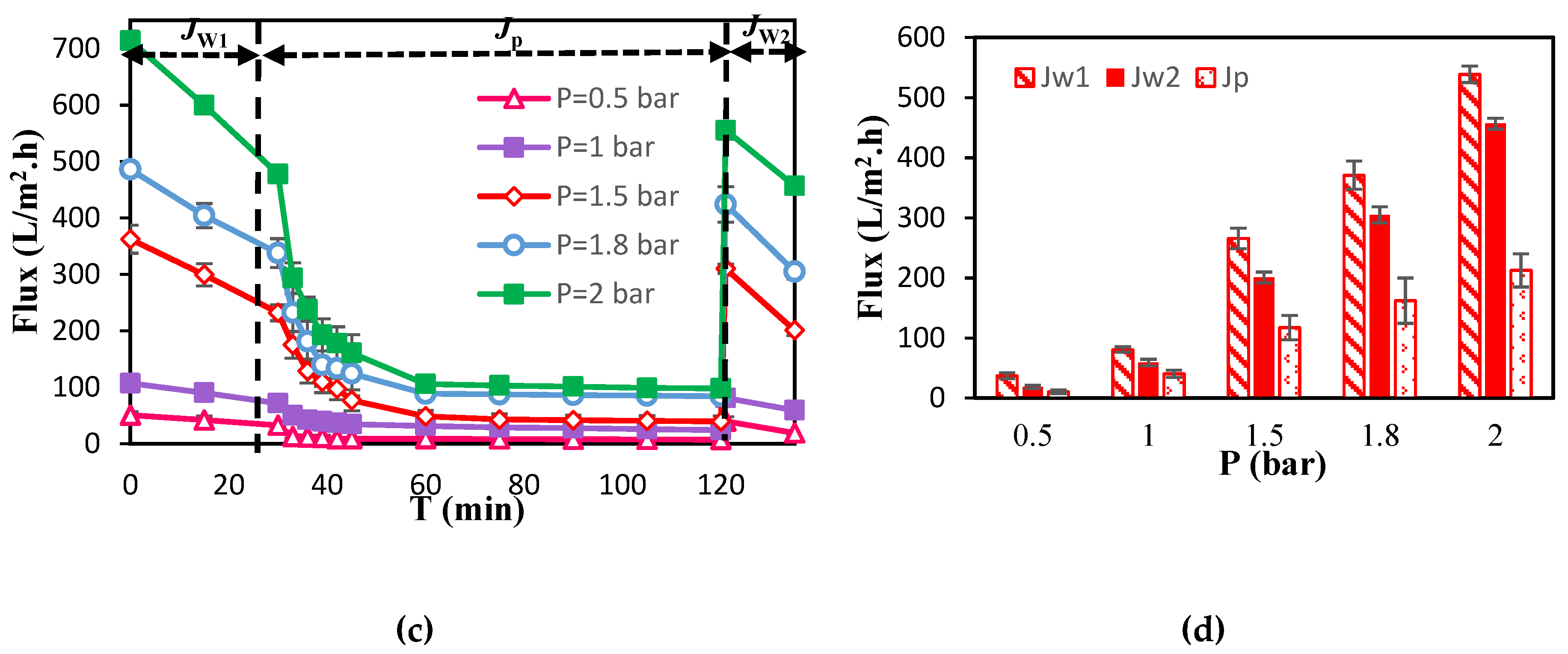

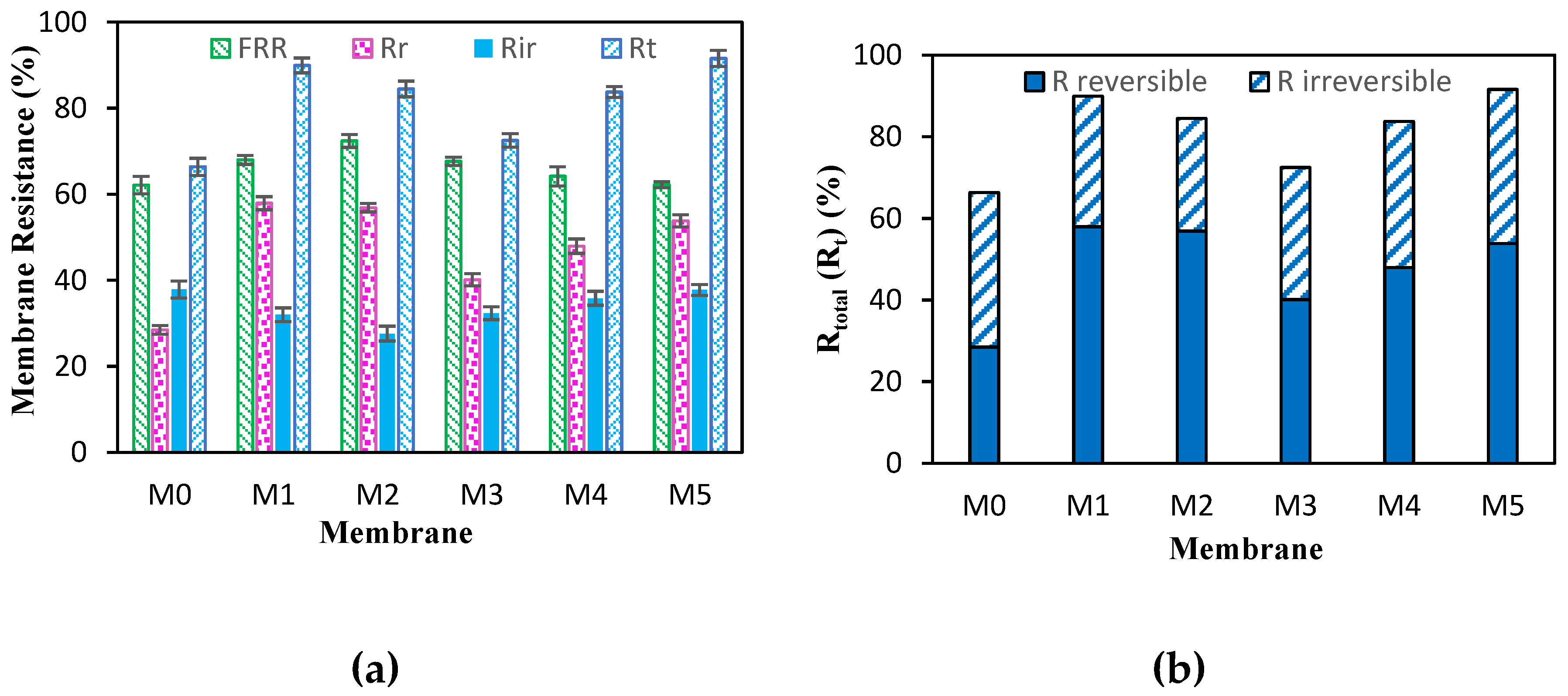

2.7. Fouling and Resistances Measurements of Membranes

3. Results and Discussion

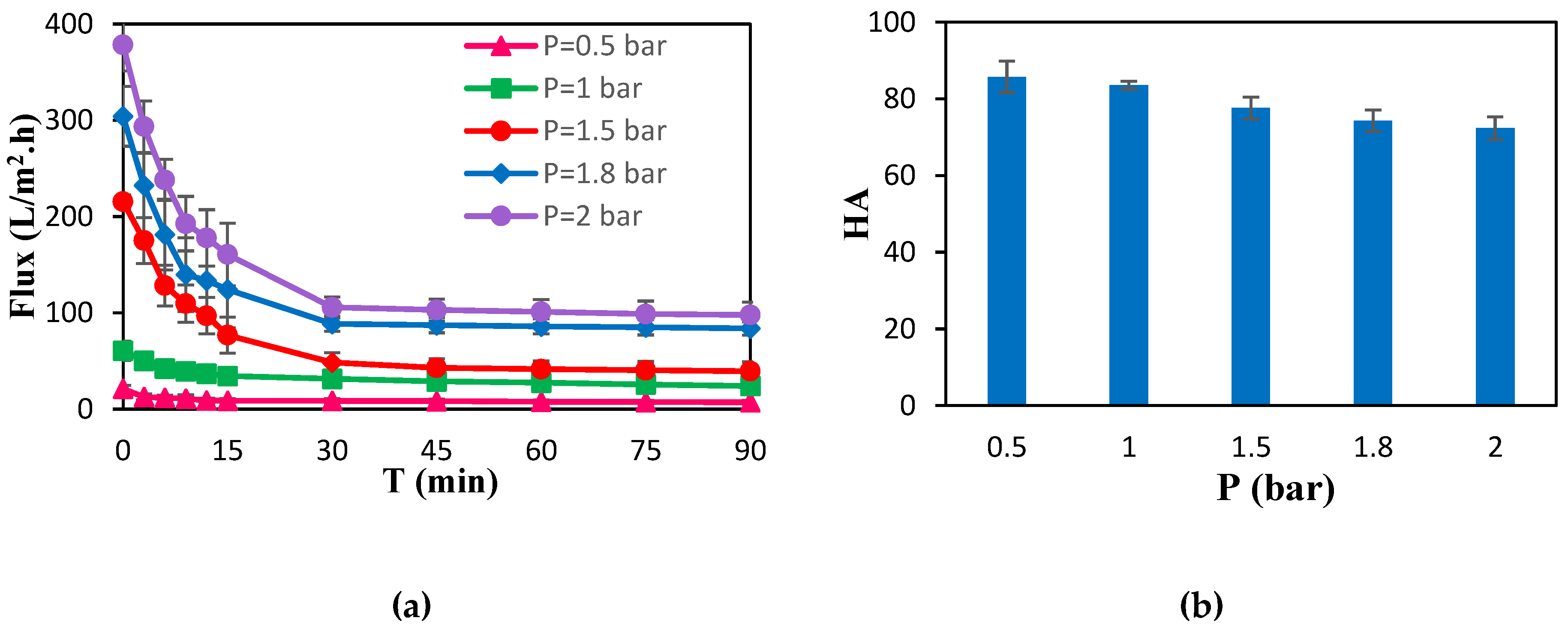

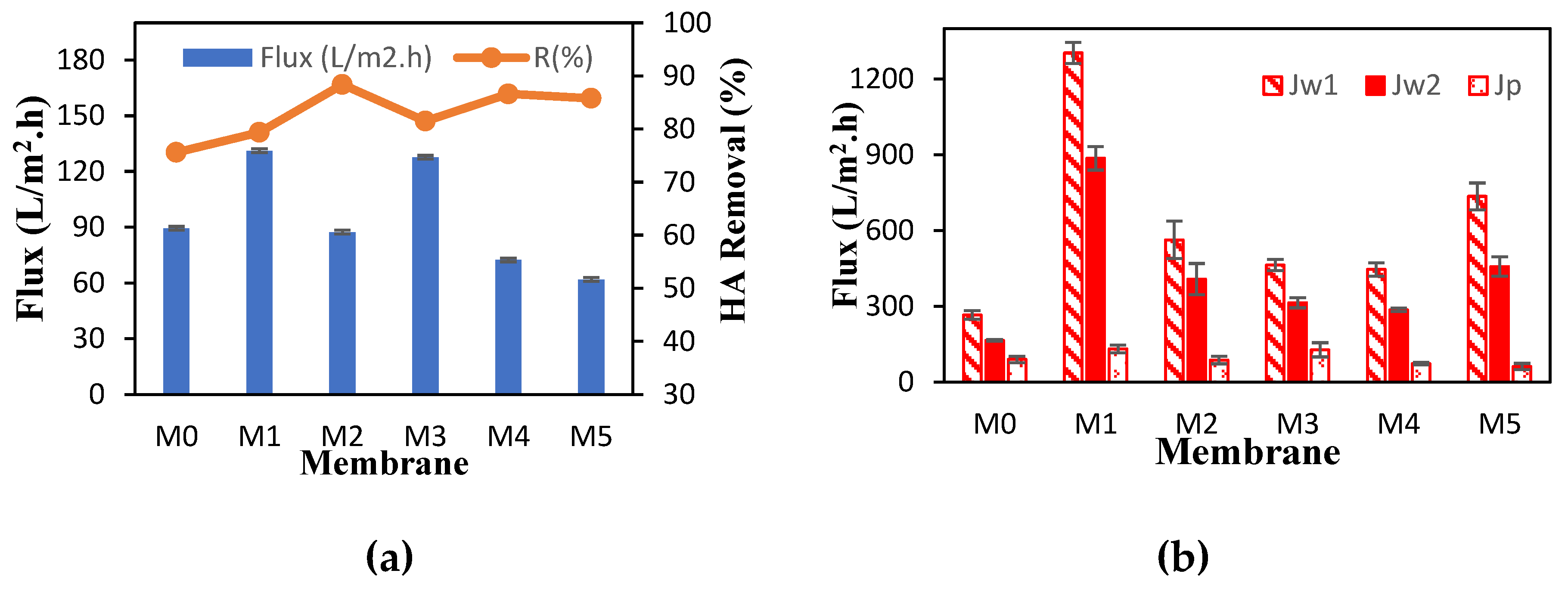

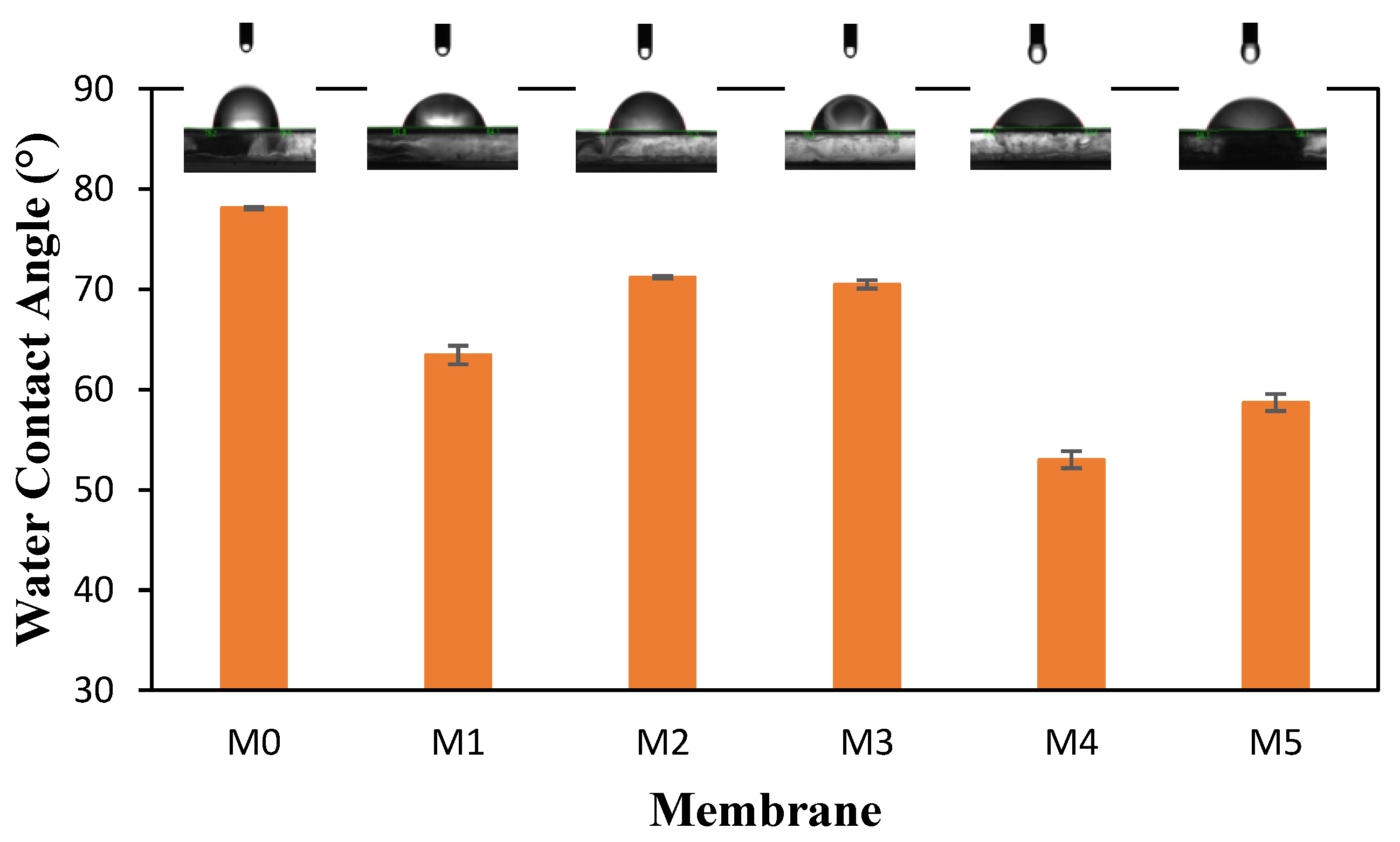

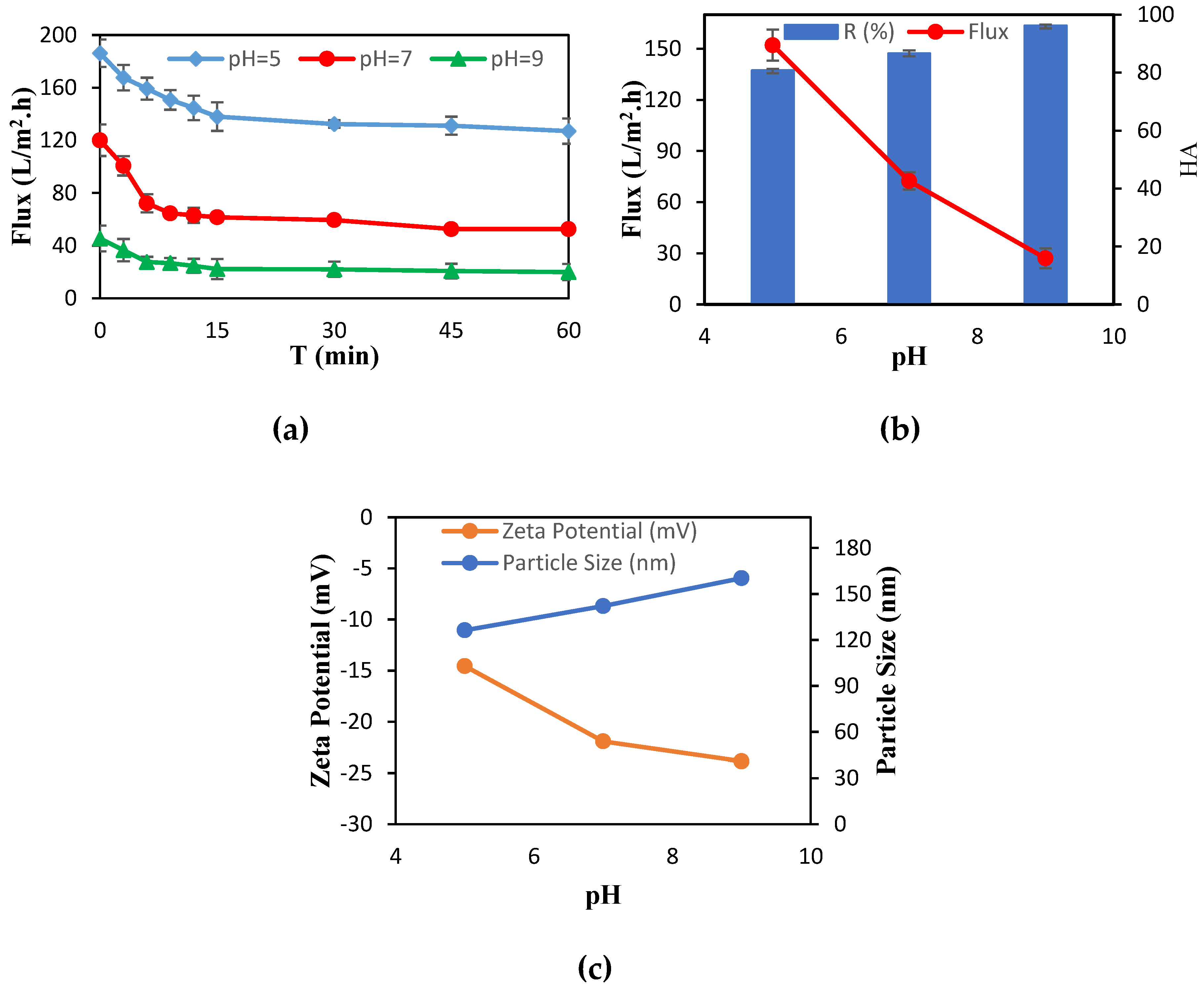

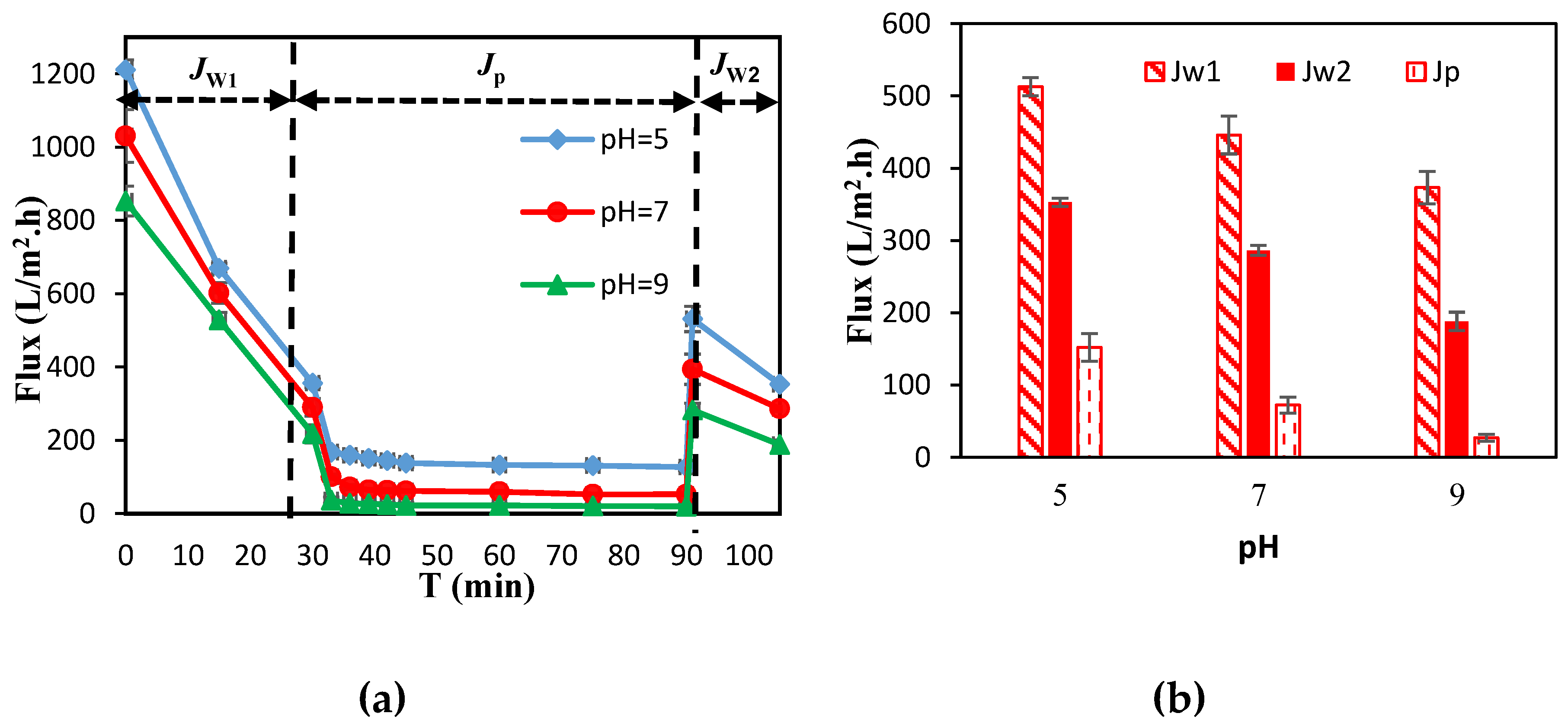

3.1. Membrane Separation Performance

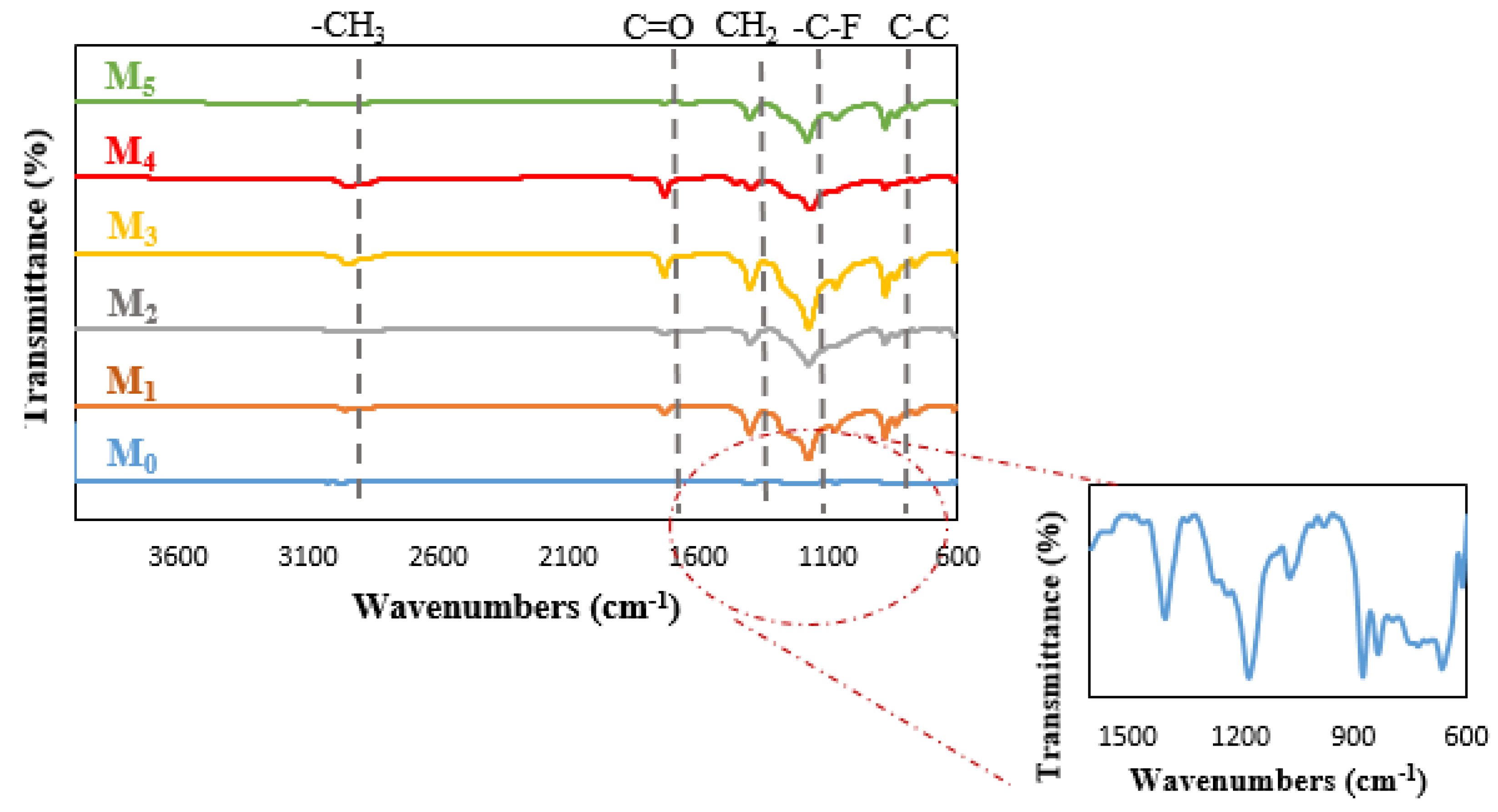

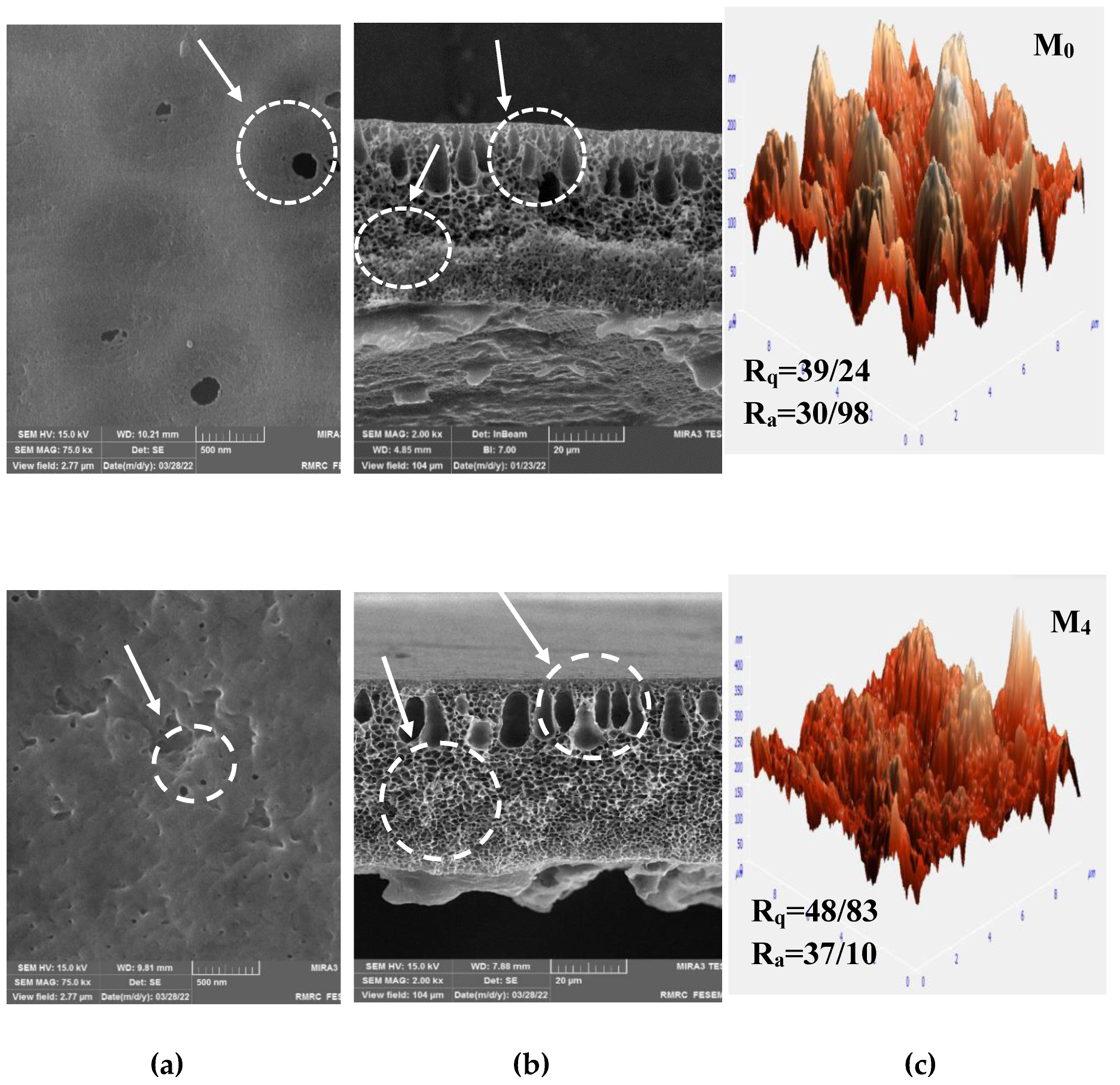

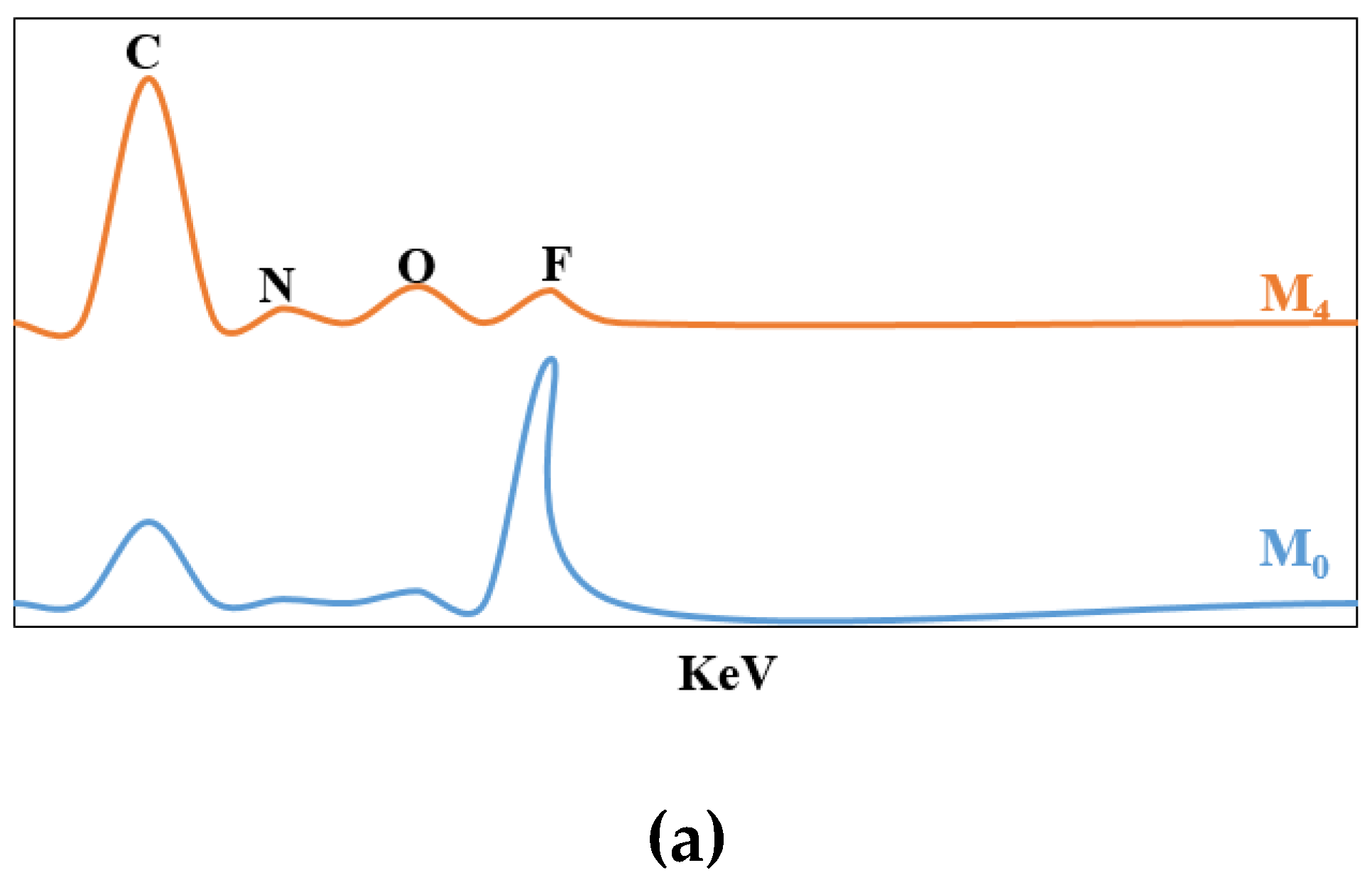

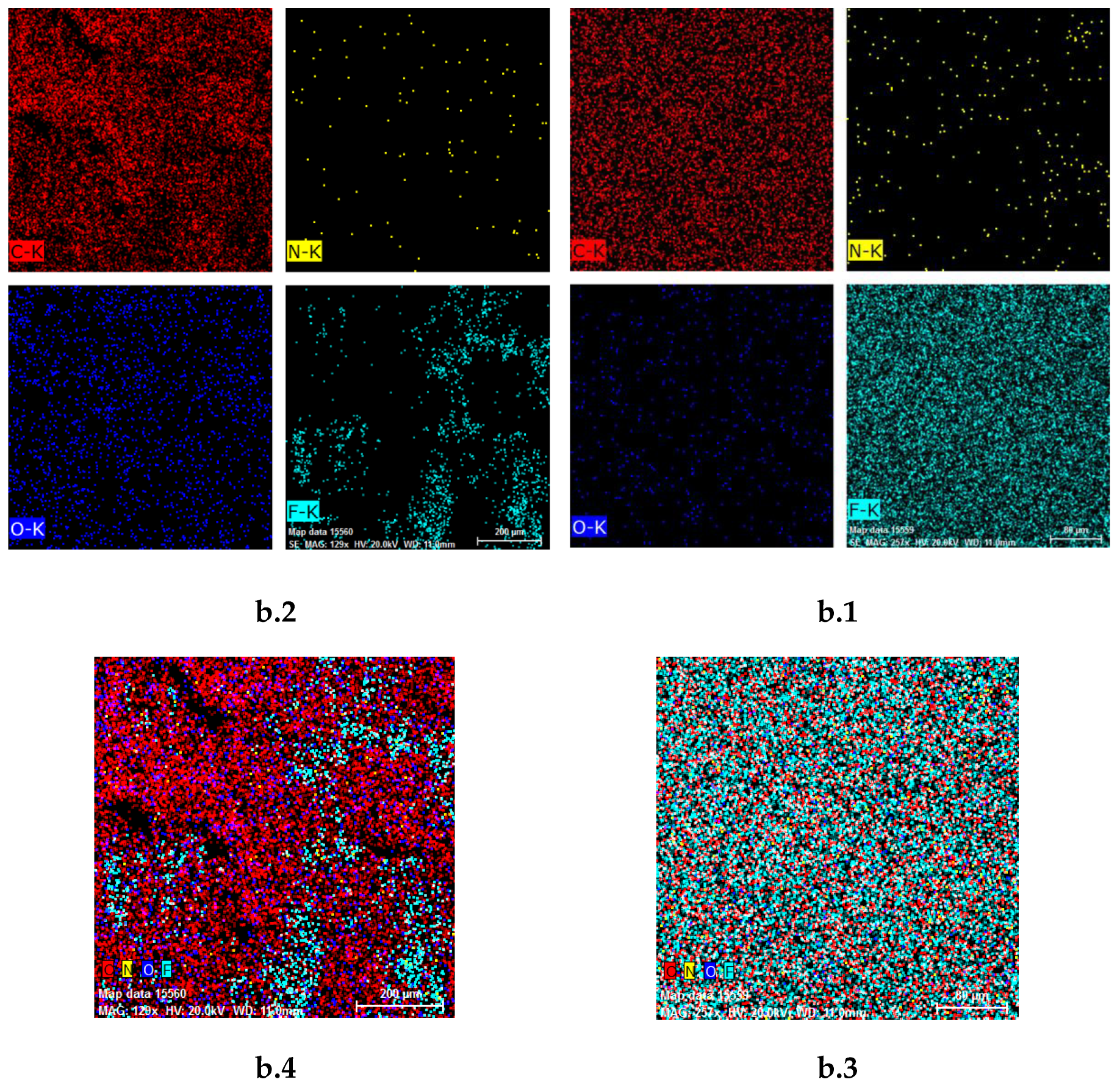

3.2. Membrane Characterization

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Credit Author Statement

Consent for publication

Financial interests

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Availability of data and materials

Acknowledgments

Competing interests

References

- Y. H. Teow, B. S. Ooi, and A. L. Ahmad, “Study on PVDF-TiO2 mixed-matrix membrane behaviour towards humic acid adsorption,” J. Water Process Eng., vol. 15, pp. 99–106, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- I. Nazri, A. L. Ahmad, and M. H. Hussin, “Microcrystalline cellulose-blended polyethersulfone membranes for enhanced water permeability and humic acid removal,” Membranes, vol. 11, no. 9. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Kumar, Z. Gholamvand, A. Morrissey, K. Nolan, M. Ulbricht, and J. Lawler, “Preparation and characterization of low fouling novel hybrid ultrafiltration membranes based on the blends of GO−TiO2 nanocomposite and polysulfone for humic acid removal,” J. Memb. Sci., vol. 506, pp. 38–49, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Algamdi, I. H. Alsohaimi, J. Lawler, H. M. Ali, A. M. Aldawsari, and H. M. A. Hassan, “Fabrication of graphene oxide incorporated polyethersulfone hybrid ultrafiltration membranes for humic acid removal,” Sep. Purif. Technol., vol. 223, pp. 17–23, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Li et al., “High-performance electrocatalytic microfiltration CuO/Carbon membrane by facile dynamic electrodeposition for small-sized organic pollutants removal,” J. Memb. Sci., vol. 601, p. 117913, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Y. He, Y. J. Zhang, H. Chen, Z. C. Han, and L. C. Liu, “Low-cost and facile synthesis of geopolymer-zeolite composite membrane for chromium(VI) separation from aqueous solution,” J. Hazard. Mater., vol. 392, p. 122359, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. D. Kusworo, N. Ariyanti, and D. P. Utomo, “Effect of nano-TiO2 loading in polysulfone membranes on the removal of pollutant following natural-rubber wastewater treatment,” J. Water Process Eng., vol. 35, p. 101190, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Luo, W. Chen, H. Song, and J. Liu, “Antifouling behaviour of a photocatalytic modified membrane in a moving bed bioreactor for wastewater treatment,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 256, p. 120381, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Makhetha and R. M. Moutloali, “Antifouling properties of Cu(tpa)@GO/PES composite membranes and selective dye rejection,” J. Memb. Sci., vol. 554, pp. 195–210, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Yong, Y. Zhang, S. Sun, and W. Liu, “Properties of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) ultrafiltration membrane improved by lignin: Hydrophilicity and antifouling,” J. Memb. Sci., vol. 575, pp. 50–59, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. I. Mat Nawi et al., “Development of Hydrophilic PVDF Membrane Using Vapour Induced Phase Separation Method for Produced Water Treatment,” Membranes (Basel)., vol. 10, no. 6, p. 121, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Xu et al., “A comprehensive description of the threshold flux during oil/water emulsion filtration to identify sustainable flux regimes for tannic acid (TA) dip-coated poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) membranes,” J. Memb. Sci., vol. 563, pp. 43–53, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. Oulad, S. Zinadini, A. A. Zinatizadeh, and A. A. Derakhshan, “Fabrication and characterization of a novel tannic acid coated boehmite/PES high performance antifouling NF membrane and application for licorice dye removal,” Chem. Eng. J., vol. 397, p. 125105, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. D’souza and R. Shegokar, “Polyethylene glycol (PEG): A versatile polymer for pharmaceutical applications,” Expert Opin. Drug Deliv., vol. 13, no. 9, pp. 1257–1275, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhao, Y. Yang, C. Li, and L. Hou, “Fabrication of GO modified PVDF membrane for dissolved organic matter removal: Removal mechanism and antifouling property,” Sep. Purif. Technol., vol. 209, pp. 482–490, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Li, L. Wu, C. Zhang, W. Chen, and C. Liu, “Applied Surface Science Hydrophilic and antifouling modi fi cation of PVDF membranes by one-step assembly of tannic acid and polyvinylpyrrolidone,” vol. 483, no. April, pp. 967–978, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. H. Teow, B. S. Ooi, A. L. Ahmad, and J. K. Lim, “Investigation of Anti-fouling and UV-Cleaning Properties of PVDF/TiO2 Mixed-Matrix Membrane for Humic Acid Removal,” Membranes (Basel)., vol. 11, no. 1, p. 16, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Jiang, K. Cheng, N. Zhang, N. Yang, L. Zhang, and Y. Sun, “One-step modification of PVDF membrane with tannin-inspired highly hydrophilic and underwater superoleophobic coating for effective oil-in-water emulsion separation,” vol. 255, no. August 2020, 2021.

- F. Sun et al., “Dopamine-decorated lotus leaf-like PVDF/TiO2 membrane with underwater superoleophobic for highly efficient oil-water separation,” Process Saf. Environ. Prot., vol. 147, pp. 788–797, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Karimi, A. Khataee, A. Ghadimi, and V. Vatanpour, “Ball-milled Cu2S nanoparticles as an efficient additive for modification of the PVDF ultrafiltration membranes: Application to separation of protein and dyes,” J. Environ. Chem. Eng., vol. 9, no. 2, p. 105115, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Yan et al., “Bio-inspired mineral-hydrogel hybrid coating on hydrophobic PVDF membrane boosting oil/water emulsion separation,” Sep. Purif. Technol., vol. 285, p. 120383, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Ren, W. Xia, X. Feng, and Y. Zhao, “Surface modification of PVDF membrane by sulfonated chitosan for enhanced anti-fouling property via PDA coating layer,” Mater. Lett., vol. 307, p. 130981, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Abdulazeez, B. Salhi, A. M. Elsharif, M. S. Ahmad, N. Baig, and M. M. Abdelnaby, “Hemin-Modified Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube-Incorporated PVDF Membranes: Computational and Experimental Studies on Oil–Water Emulsion Separations,” Molecules, vol. 28, no. 1, p. 391, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Ho, Y. H. Teow, W. L. Ang, and A. W. Mohammad, “Novel GO/OMWCNTs mixed-matrix membrane with enhanced antifouling property for palm oil mill effluent treatment,” Sep. Purif. Technol., vol. 177, pp. 337–349, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. Ni, X. Zheng, Y. Zhang, X. Zhang, and Y. Li, “Multifunctional porous materials with simultaneous high water flux, antifouling and antibacterial performances from ionic liquid grafted polyethersulfone,” Polymer (Guildf)., vol. 212, p. 123183, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Sakarkar, S. Muthukumaran, and V. Jegatheesan, “Evaluation of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) loading in the PVA/titanium dioxide (TiO2) thin film coating on polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane for the removal of textile dyes,” Chemosphere, vol. 257, p. 127144, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Singh and M. K. Purkait, “Evaluation of mPEG effect on the hydrophilicity and antifouling nature of the PVDF-co-HFP flat sheet polymeric membranes for humic acid removal,” J. Water Process Eng., vol. 14, pp. 9–18, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- P. Shi, X. Hu, Y. Wang, M. Duan, S. Fang, and W. Chen, “A PEG-tannic acid decorated microfiltration membrane for the fast removal of Rhodamine B from water,” Sep. Purif. Technol., vol. 207, pp. 443–450, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. S. M. Yatim, O. B. Seng, and K. A. Karim, “Fluorosilaned-TiO 2 /PVDF membrane distillation with improved wetting resistance for water recovery from high solid loading wastewater,” J. Membr. Sci. Res., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 55–64, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Xu et al., “Polyphenol engineered membranes with dually charged sandwich structure for low-pressure molecular separation,” J. Memb. Sci., vol. 601, p. 117885, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. S. Khoo, W. J. Lau, Y. Y. Liang, M. Karaman, M. Gürsoy, and A. F. Ismail, “Eco-friendly surface modification approach to develop thin film nanocomposite membrane with improved desalination and antifouling properties,” J. Adv. Res., vol. 36, pp. 39–49, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Fan et al., “Enhancing the antifouling and rejection properties of PVDF membrane by Ag3PO4-GO modification,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 801, p. 149611, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Alpatova, M. Meshref, K. N. McPhedran, and M. Gamal El-Din, “Composite polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane impregnated with Fe2O3 nanoparticles and multiwalled carbon nanotubes for catalytic degradation of organic contaminants,” J. Memb. Sci., vol. 490, pp. 227–235, Sep. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Liu et al., “Multi-functional tannic acid (TA)-Ferric complex coating for forward osmosis membrane with enhanced micropollutant removal and antifouling property,” J. Memb. Sci., vol. 626, p. 119171, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Khezraqa, H. Etemadi, H. Qazvini, and M. Salami-Kalajahi, “Novel polycarbonate membrane embedded with multi-walled carbon nanotube for water treatment: A comparative study between bovine serum albumin and humic acid removal,” Polym. Bull., vol. 79, no. 3, pp. 1467–1484, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Kallem, I. Othman, M. Ouda, S. W. Hasan, I. AlNashef, and F. Banat, “Polyethersulfone hybrid ultrafiltration membranes fabricated with polydopamine modified ZnFe2O4 nanocomposites: Applications in humic acid removal and oil/water emulsion separation,” Process Saf. Environ. Prot., vol. 148, pp. 813–824, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. A. G. Krishnan, S. Abinaya, G. Arthanareeswaran, S. Govindaraju, and K. Yun, “Surface-constructing of visible-light Bi2WO6/CeO2 nanophotocatalyst grafted PVDF membrane for degradation of tetracycline and humic acid,” J. Hazard. Mater., vol. 421, p. 126747, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Mondal, N. S. Samanta, V. Meghnani, and M. K. Purkait, “Selective glucose permeability in presence of various salts through tunable pore size of pH responsive PVDF-co-HFP membrane,” Sep. Purif. Technol., vol. 221, pp. 249–260, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Türk, B. Ünlu, and M. S. Mustapa, “Preparation of Innovative PEG/Tannic Acid/TiO2 Hydrogels and Effect of Tannic Acid Concentration on Their Hydrophilicity,” Int. J. Integr. Eng., vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 266–273, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. Wang, A. Xie, X. Dai, Y. Yan, and J. Dai, “Facile surface coating of metal-tannin complex onto PVDF membrane with underwater Superoleophobicity for oil-water emulsion separation,” Surf. Coatings Technol., vol. 389, p. 125630, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Zhang, X. Song, Y. Chen, B. Jiang, L. Zhang, and H. Jiang, “A facile and economic route assisted by trace tannic acid to construct a high-performance thin film composite NF membrane for desalination,” Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol., vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 956–968, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Fahrina et al., “Functionalization of PEG-AgNPs Hybrid Material to Alleviate Biofouling Tendency of Polyethersulfone Membrane,” Polymers, vol. 14, no. 9. 2022. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Range |

|---|---|

| Pollutant Concentration (ppm) | 30, 50, 80, 100 |

| Additive to Nanoparticles Weigh Percentage Ratio )w%( (PEG:TA) | 0:0 (M0), 1:0 (M1), 0:1 (M2), 1:1 (M3), 4:1 (M4), 1:4 (M5) |

| pH | 5, 7, 9 |

| Pressure (bar) | 0.5. 1, 1.5, 1.8, 2 |

| Membrane | PEG:TA | Jp (L/m2.h) | R (%) | FRR (%) | Rr (%) | Rir (%) | Rt (%) | ε (%) | Dm (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M0 | 0:0 | 89.39 | 75.59 | 62.12 | 28.47 | 37.87 | 66.34 | 56.98 | 21.59 |

| M1 | 1:0 | 131.21 | 79.37 | 67.98 | 57.92 | 32.01 | 89.93 | 73.46 | 44.59 |

| M2 | 0:1 | 87.4 | 88.38 | 72.39 | 56.86 | 27.6 | 84.47 | 49.38 | 40.92 |

| M3 | 1:1 | 127.62 | 81.49 | 67.64 | 40.12 | 32.35 | 72.48 | 65.74 | 29.89 |

| M4 | 4:1 | 72.43 | 86.62 | 64.17 | 47.93 | 35.82 | 83.76 | 46.62 | 34.24 |

| M5 | 1:4 | 61.9 | 85.79 | 62.23 | 53.81 | 37.76 | 91.58 | 37.03 | 48.48 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).