Submitted:

05 April 2024

Posted:

08 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Algorithm Literacy: A Dimension of MIL Still in Its Infancy

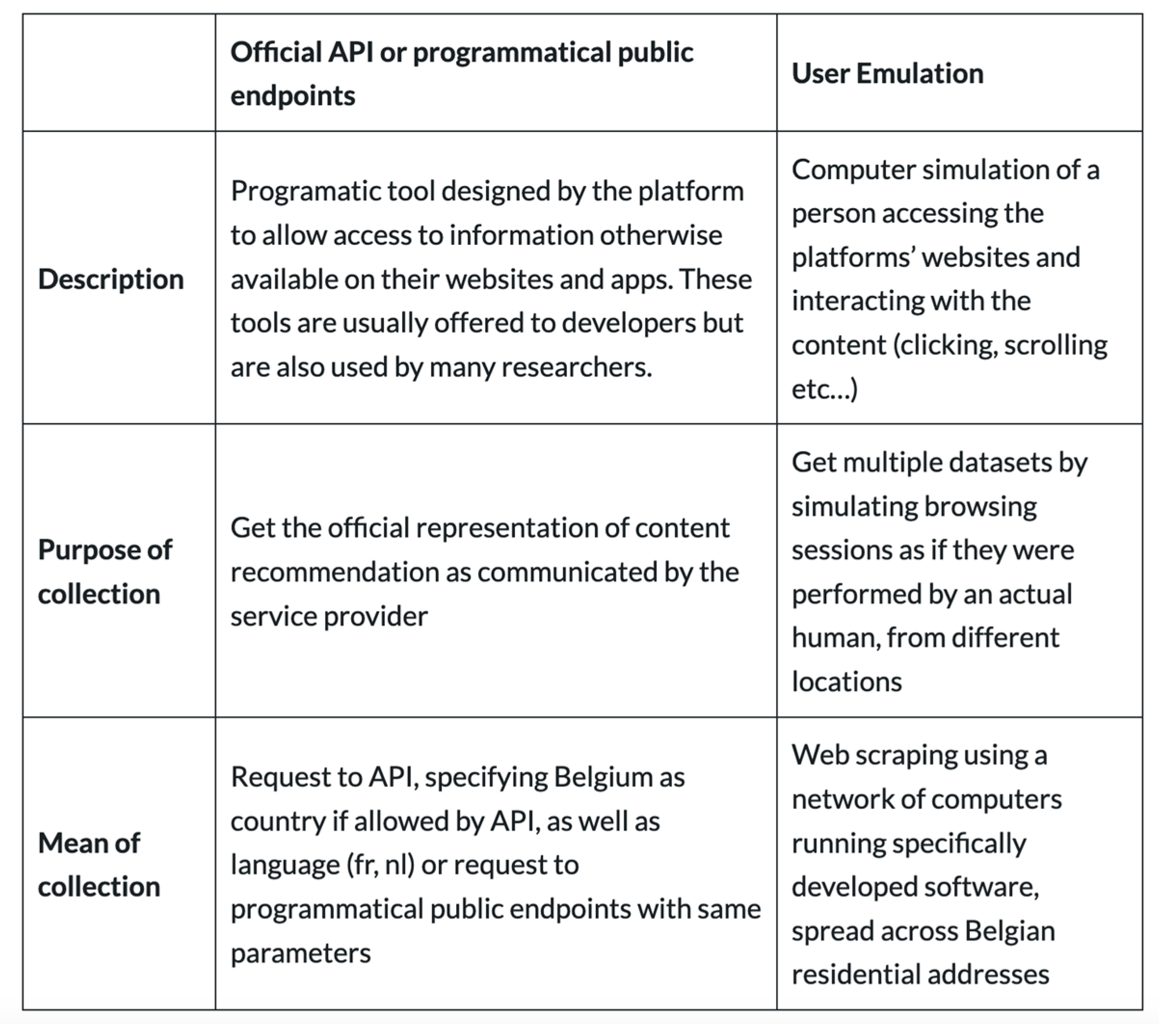

1.2. MIL Methodology, Research Design and Data Collection

- (1)

- The initial inquest: the online “trending” information of the moment

- (2)

- The Apache.be investigation and new story

- (3)

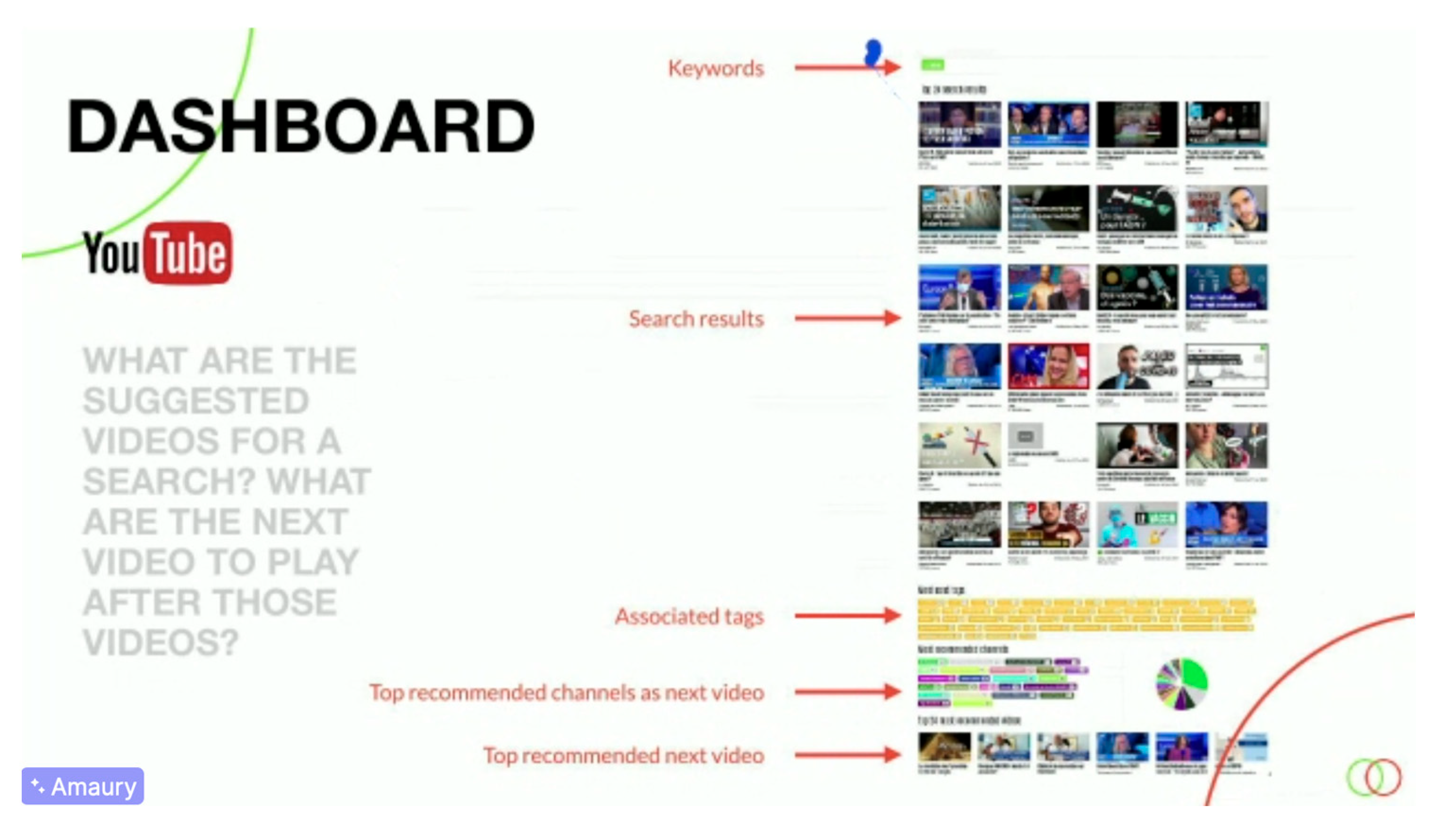

- A zoom on a search scenario of use with the Dashboard

- (4)

- An explanation of a key algorithmic notion

- (5)

- The resolution: the disinformation risk avoided/dealt with

- (6)

- The MIL solutions and competences called for.

- -

- A modular approach (stories, podcasts, quizzes) to allow for a variety of entries for practitioners and educators,

- -

- Authentic documents and examples to remain as close as possible to users’ experiences and societal issues,

- -

- A competence-based framework with verbalised notions and actions to stimulate critical thinking and foster civic actions,

- -

- A multi-stakeholder strategy that shows the perspectives of the different actors involved in understanding algorithms and in the co-design of MIL interventions (developers, journalists, experts).

3. Results

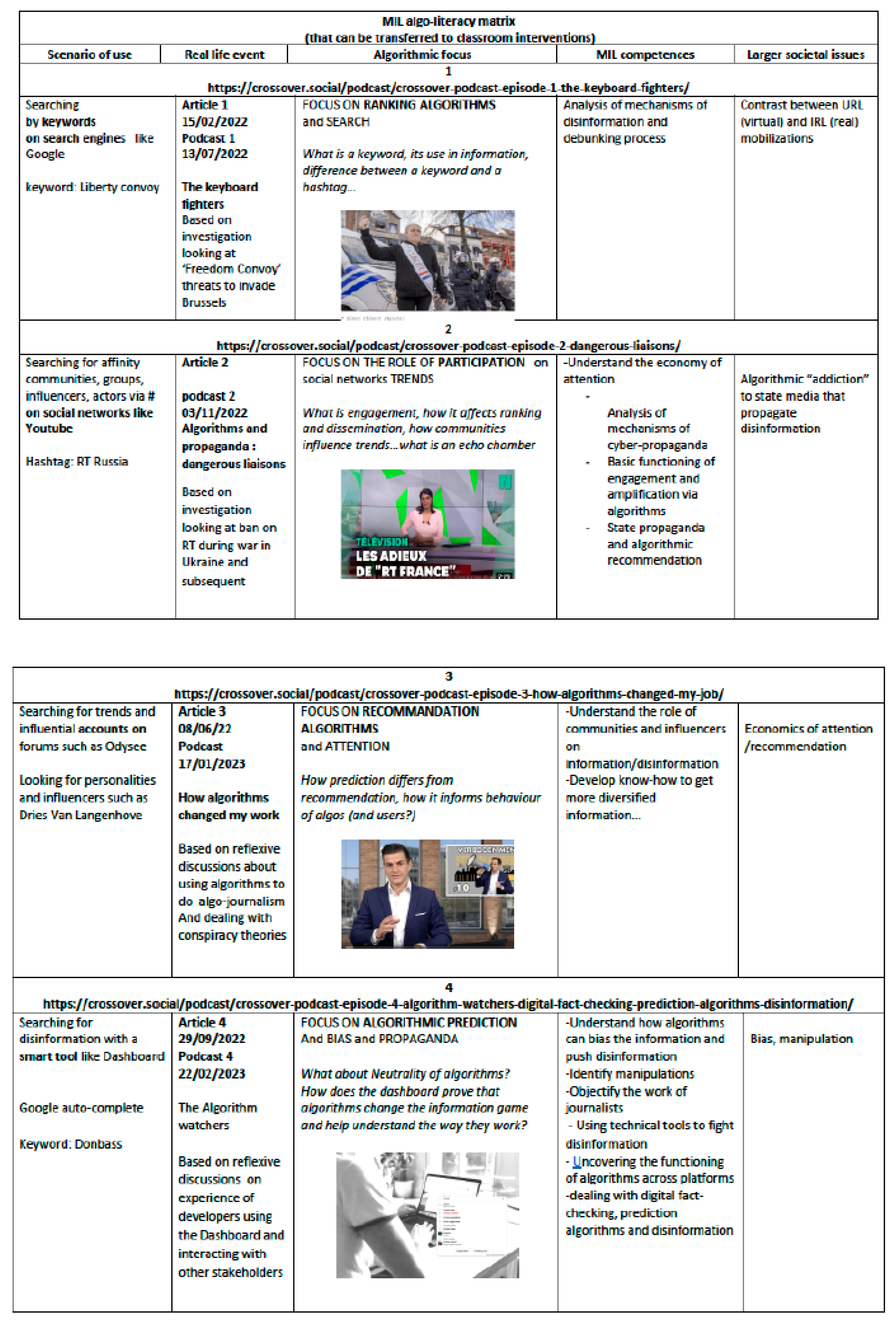

3.1. The MIL Algorithm-Literacy Matrix of Scenarios of Use

- Scenario 1, “the keyboard fighters”, showed the mismatch between the online calls for action and real-life mobilisations as the “liberty convoy” threats, that seemed threatening online, turned out to be insubstantial in real life. The role of algorithmic ranking was thus debunked in relation to user search. The MIL lesson drawn was that disinformation did not always work and had to be verified by facts (See podcast 1).

- Scenario 2, “algorithms and propaganda: dangerous liaisons”, revealed how algorithms tended to promote state propaganda: as Russia Today was banned by the European decision (due to the war in Ukraine), algorithms recommended a new state-controlled media, CGTN, the state channel of the Chinese Communist Party, that relayed Russian propaganda. The role of algorithmic recommendation was thus exposed in relation to user engagement. The MIL lesson drawn was that disinformation was amplified along polarised lines (See podcast 2).

- Scenario 3, “how algorithms changed my life”, unveiled how conspiracy theories circulated on influential accounts, in “censorship free” and unmoderated networks like Odysee. It followed an influencer, the extreme right political personality Dries Van Langenhove, who called for racism, violence and anti-covid stances. The role of algorithmic recommendation was thus unveiled in relation to user echo chambers. The MIL lesson drawn was that information diversity was key to avoid being caught in the rabbit holes of the attention economy (See podcast 3).

- Scenario 4, “the algorithm watchers”, demonstrated how Google auto-complete systematically offered users the Donbass Insider recommendation when they typed Donbass in their search bar, across all people user-meters. Donbass Insider relayed Russian false messages about the war in Ukraine and was linked to Christelle Néant, a Franco-Russian pro-Kremlin blogger and self-styled journalist. The role of algorithmic prediction was revealed in relation to user interactions with the tool affordances. The MIL lesson drawn was that queries and prompts can lead to automated bias and manipulation (See podcast 4).

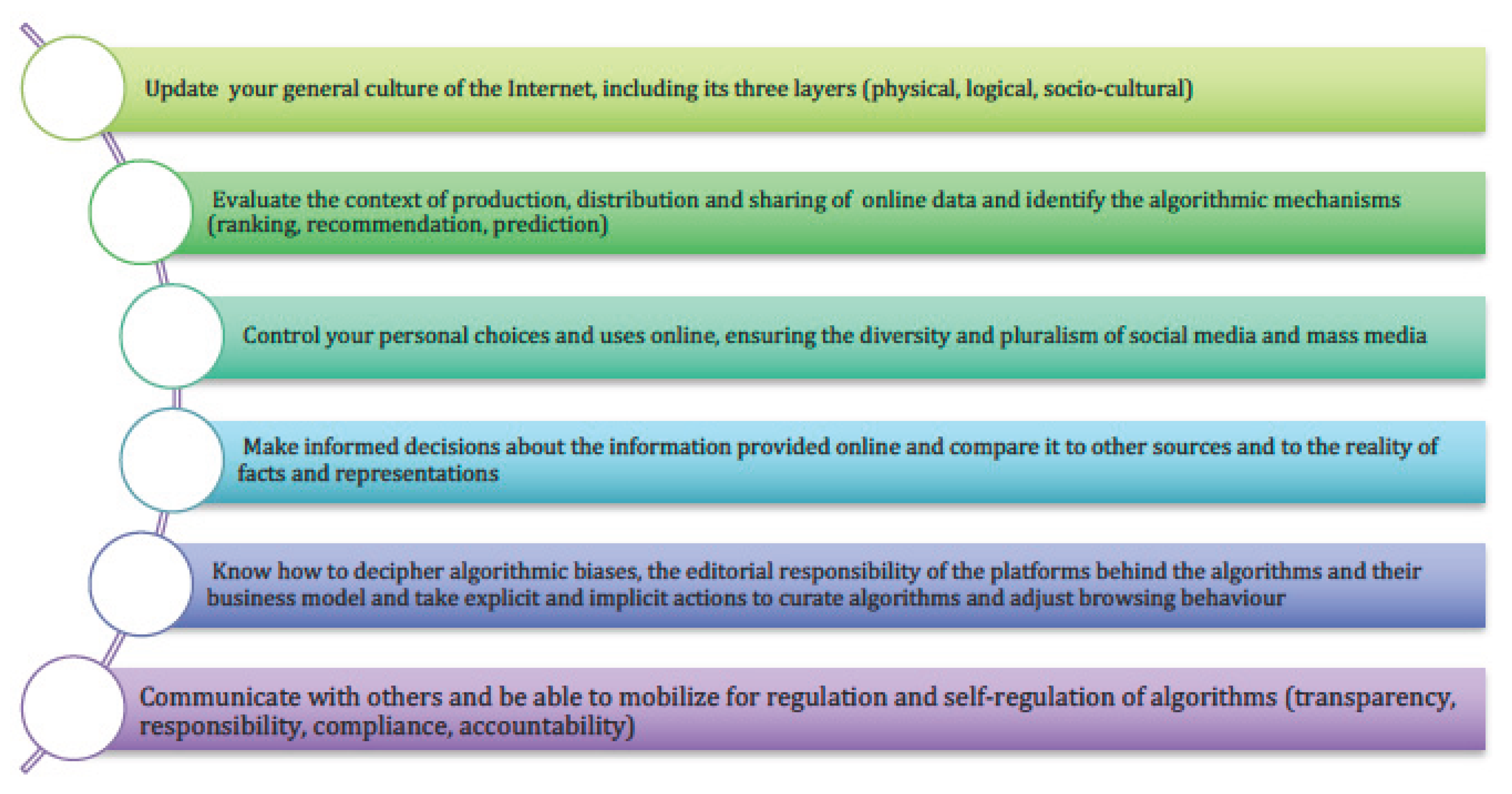

3.2. MIL AL-Competence Framework

- -

- Know the new context of news production and amplification via algorithms

- -

- Pay attention to emotions and how they are stirred by sensationalist contents and take a step back from “hot” news,

- -

- Be suspicious and aware of “weak signals” for disinformation (lack of traffic on some accounts, except for some divisive topics; very little activity among and across followers on a so-called popular website or community, …)

- -

- Fight confirmation biases and other cognitive biases

- -

- Vary sources of information

- -

- Be vigilant about divisive issues where opinion dominates and facts and sources are not presented

- -

- Modify social media uses to avoid filter bubbles and (unsolicited) echo chambers

- -

- Set limits to tracking so as to reduce targeting (as less data are collected from your devices)

- -

- Deactivate some functionalities regularly and set the parameters of your accounts

- -

- Browse anonymously (use VPNs)

- -

- Decipher algorithms, their biases and platform responsibility

- -

- “Ride” algorithms for specific purposes

- -

- Pay attention to RGPD and platform loyalty to data protection

- -

- Mobilise for more transparency and accountability about their impact

- -

- Require social networks to delete fake news accounts, to ban toxic personalities, to moderate contents

- -

- Encourage the creation of information verification sites and use them

- -

- Use technical fact checking tools like the Dashboard or InVID-Weverify

- -

- Signal or report to platforms or web managers if misuses are detected

- -

- Comment and/or rectify “fake news”, whenever possible

- -

- Alert fact checkers, journalists or the community of affinity

3.3. The Knowledge Base with Pedagogical Pathways and Design Considerations

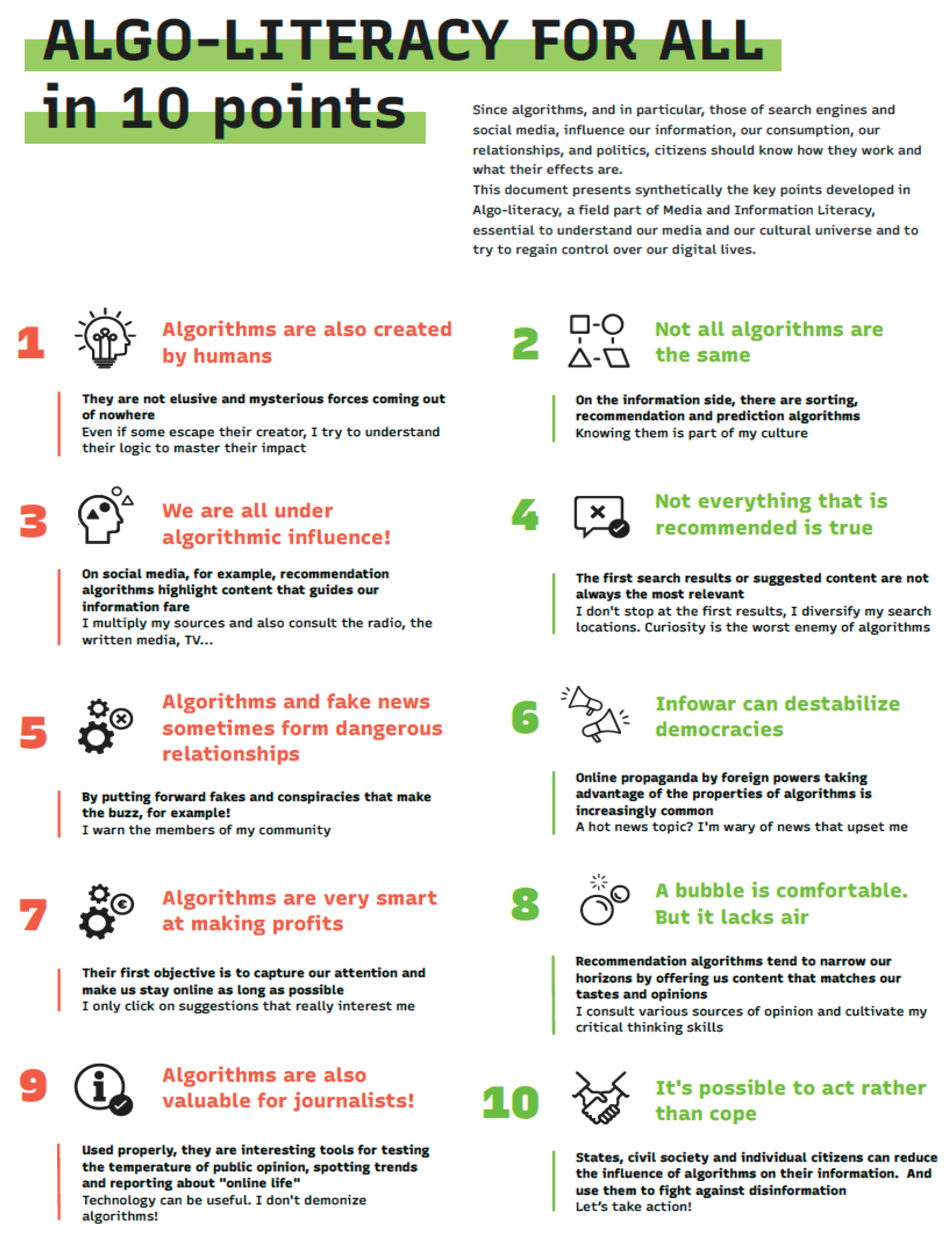

Apart from understanding how algorithms work, understanding the economic and geopolitical models behind them, and using your critical thinking skills wisely (without becoming paranoid), you can build some strategies to control your information better. Here is a list of reasonable goals if you want to reduce the influence of algorithms on your information. It's up to you to find the solution that goes with it!

4. Discussion

4.1. Understanding Opacity

4.2. Confirming the Definition of Algorithm Literacy

4.3. Fine-Tuning the Competence Framework with MIL Design

5. Conclusions

References

- European commission, DG-Connect (2018). A multi-dimensional approach to disinformation - Report of the independent High level Group on fake news and online disinformation. Publications Office of the European Union. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/final-report-high-level-expert-group-fake-news-and-online-disinformation.

- Seaver, N. (2019). Captivating Algorithms: Recommender Systems as Traps. Journal of Material Culture, 24(4), 421-436. [CrossRef]

- Dogruel, L., Facciorusso, D., & Stark, B. (2020). ‘I’m still the master of the machine.’ Internet users’ awareness of algorithmic decision-making and their perception of its effect on their autonomy. Special Issue of Digital Communication Research. Information, Communication & Society, 25:9, 1311-1332. [CrossRef]

- boyd, d. , Crawford, K. (2012). Critical questions for big data: provocations for a cultural, technological, and scholarly phenomenon, Information, Communication & Society, 15 (5), 662-679. [CrossRef]

- Hill, J. (2022), "Policy responses to false and misleading digital content : A snapshot of children’s media literacy", Documents de travail de l'OCDE sur l'éducation, 275, Éditions OCDE. [CrossRef]

- Crossover Project (2021-22). https://crossover.social.

- Beer, D. (2017). The social power of algorithms. Information, Communication & Society, 20(1), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Dogruel, L. Masur, P. and Joeckel, S. (2022) Development and Validation of an Algorithm Literacy Scale for Internet Users, Communication Methods and Measures, 16 (2), 115-133. [CrossRef]

- Cotter, K. M. (2020). Critical algorithmic literacy: Power, epistemology, and platforms [Dissertation]. Michigan State University, Michigan. https://search.proquest.com/openview/3d5766d511ea8a1ffe54c53011acf4f2/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y.

- Nguyen, D. and Beijnon, B. (2023): The data subject and the myth of the ‘black box’ data communication and critical data literacy as a resistant practice to platform exploitation, Information, Communication & Society, 27 (2), 333-349. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, P. (2016) Data literacy conceptions, community capabilities. The Journal of Community Informatics, 12 (3). [CrossRef]

- Shin, D. Rasul, A. and Fotiadis, A. (2022), "Why am I seeing this? Deconstructing algorithm literacy through the lens of users", Internet Research, Vol. 32 No. 4, pp. 1214-1234. [CrossRef]

- Head, A. Fister, B. and MacMillan, M. (2020). Information literacy in the age of algorithms. https://projectinfolit.org/pubs/algorithm-study/pil_algorithm-study_2020-01-15.pdf.

- Swart, J. (2021). Experiencing Algorithms: How Young People Understand, Feel About, and Engage With Algorithmic News Selection on Social Media. Social Media + Society, 7(2). [CrossRef]

- Bucher, T. (2017). The algorithmic imaginary: Exploring the ordinary affects of Facebook algorithms. Information, Communication & Society, 20(1), 30-44. [CrossRef]

- Brisson-Boivin, Kara and Samantha McAleese. (2021). Algorithmic Awareness: Conversations with Young Canadians about Artificial Intelligence and Privacy. MediaSmarts. Ottawa. https://mediasmarts.ca/sites/default/files/publication-report/full/report_algorithmic_awareness.pdf.

- Nygren, T. Frau-Meigs, D, Corbu, N and Santoval, S. (2022). Teachers’ views on disinformation and media literacy supported by a tool designed for professional fact-checkers: perspectives from France, Romania, Spain and Sweden, SN Soc Sci 2:40. [CrossRef]

- Moylan, R. and Code J. (2023) Algorithmic futures: an analysis of teacher professional digital competence frameworks through an algorithm literacy lens, Teachers and Teaching, Theory and practice. [CrossRef]

- Cotter, K. et Reisdorf, B. C. (2020). Algorithmic Knowledge Gaps: A New Horizon of (Digital) Inequality. International Journal of Communication, 14, 745-765. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/12450.

- Frau-Meigs, D. (2024). User empowerment through media and information literacy responses to the evolution of generative artificial intelligence (GAI). UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000388547.

- Frau-Meigs, Divina (2012). Transliteracy as the new research horizon for media and information literacy. Media Studies, 3(6). https://hrcak.srce.hr/ojs/index.php/medijske-studije/article/view/6064.

- Frau-Meigs, D. (2022a). Transliteracy and the digital media: Theorizing Media and Information Literacy, In: International Encyclopedia of Education (4th Edition) Robert Tierney, Fazal Rizvi and Kadriye Ercikan (eds). Elsevier.

- Carroll, J. M. (2000). Making use: Scenario-based design of human-computer interactions. The MIT Press.

- Alexander, I. F. , & Maiden, N., (Eds.) (2004). Scenarios, stories, use cases through the systems development life cycle. Wiley.

- Hargittai, E. , Gruber, J., Djukaric, T., Fuchs, J. et Brombach, L. (2020). Black box measures? How to study people’s algorithm skills. Information, Communication & Society, 23(5), 764-775. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, A. (2019). Chasing Frankenstein’s Monster: Information literacy in the black box society. Journal of Documentation, 75(6), 1475-1485. [CrossRef]

- Frau-Meigs, D. and Corbu, N. (eds.) (2024). Disinformation Debunked: MIL to build online resilience. Routledge.

- Potter, W. J., & Thai, C. L. (2019). Reviewing media literacy intervention studies for validity. Review of Communication Research, 7, 38–66. [CrossRef]

- Savoir Devenir, Algo-literacy Prebunking kit (2022). https://savoirdevenir.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/PREBUNKING-KIT-ENG.pdf.

- Kahne, J., Hodgin, E., & Eidman-Aadahl, E. (2016). Redesigning civic education for the digital age: Participatory politics and the pursuit of democratic engagement. Theory & Research in Social Education, 44 (1), 1-35. [CrossRef]

- McGrew, S., Breakstone, J., Ortega, T., Smith M. and Wineburg, S. (2018). Can Students Evaluate Online Sources? Learning From Assessments of Civic Online Reasoning. Theory & Research in Social Education, 46(2), 165-193. [CrossRef]

- Frau-Meigs, D. (2022b). How Disinformation Reshaped the Relationship between Journalism and Media and Information Literacy (MIL): Old and New Perspectives Revisited, Digital Journalism, 10 (5), 912-922. [CrossRef]

- Pasquale, F. (2015). The Black Box Society. The Secret Algorithms That Control Money and Information. Harvard UP.

- Burrell, J. (2016). How the machine ‘thinks’: Understanding opacity in machine learning algorithms. Big Data & Society, 3(1). [CrossRef]

- Le Deuff, O. and Roumanos, R (2021). Enjeux définitionnels et scientifiques de la littératie algorithmique : entre mécanologie et rétro-ingénierie documentaire », tic&société 15 (2-3). [CrossRef]

- Masterman, L. (1985). Teaching the media. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Wineburg S, and McGrew, S. ( 2019). Lateral Reading and the Nature of Expertise: Reading Less and Learning More When Evaluating Digital Information. Teachers college Record 121 (22), 1-40. [CrossRef]

- Rieder, B. (2020). Engines of Order: A Mechanology of Algorithmic Techniques. Amsterdam University Press.

- European Commission, DG-EAC (2022). Guidelines for teachers and educators on tackling disinformation and promoting digital literacy through education and training. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Kemper, J., & Kolkman, D. (2018). Transparent to whom? No algorithmic accountability without a critical audience. Information, Communication & Society, 19(4), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Kitchin, R. (2017). Thinking critically about and researching algorithms. Information, Communication & Society, 20(1), 14–29. [CrossRef]

|

| GOALS | SOLUTIONS |

|---|---|

| Limiting the amount of data collected from your devices to reduce targeting | Setting your cookies to limit tracking |

| Browsing anonymously | Using a VPN |

| Not falling for sensationalist news | Watching out for information that arouses a lot of emotion and verify it |

| Going beyond the beaten path, varying your sources of information | Opening your community to people with different profiles. Snooping elsewhere than in the first page of Google or searching on other sites |

| Making sure that informing yourself is a voluntary act, that respects clear rules | Mobilising for an increased regulation of algorithms, for more transparency about their impact. |

| Fake accounts and bots are created by the millions every day and are often the basis of raging debates. What are the signs that should make you suspicious? |

|

| Answer: the correct answers (in bold) are only clues. The more of them that converge, the higher the probability that you are dealing with a bot. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).