1. Introduction

The wood related activities in Rwanda constitute an important downstream activity of the agro-forestry sub-sector in the Rwandan economy because of its high relevance in adding economic value to the wood and the very large value chain, support the diversification of the products that can be produced, and increases the incomes and employment of involved business operators. It is indicated by the “Made in Rwanda Policy ” and the “Domestic Market Recapturing Strategy (DMRS)” that for Rwanda to increase its trade competitiveness, and reduce trade imbalances forest and wooden furniture are one of the key cluster areas which should be promoted foster light manufacturing industry through wood processing (The Ministry of Commerce and Industry (MINICOM), November 2017). The latest study by Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) (2019) estimated that in Rwanda, the number of producers involved in wood-based SMEs were about 1,100 individuals and traders 1,000 people, and in total, the production segment includes around 6,600 permanent jobs and 10,000 temporary jobs (Tsanga et. al., 2019).

Unlike COVD-19, which put its feet of the pedal on Rwanda economic growth trajectory, the Rwandan economy has recorded a strong and inclusive growth trajectory over the past two decades (2000-2020) with the highest real growth rate of 9.4% in 2019, however, the latest data (National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR), 2021) show that Rwanda economic decelerated to -3.4 percent in 2020. This economic fallout is unequivocally attributed to COVID-19 and associated containment measures which were characterized by people’s movement restriction, business closures, border closures, to put it simply “series of lockdowns”. The virus containment measures undertaken by the Government of Rwanda come with difficult economic trade-offs. In particular, the heightened uncertainty, pressure on the exchange rate translates into tightening financial conditions and contraction of economic activities. According to the National Bank of Rwanda (BNR) and The International Monetary fund (June 2020), there has been a drastic drop of economy by -62.9% measured by the Composite Index of Economic Activity (CIEA) and The Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MINECOFIN) (2020), reported that weekly transactions declined by 75 percent compared to the same week in 2019 reflecting a massive downturn in business activity. Furthermore, Google’s COVID-19 community mobility report shows that between February and March 2019, the mobility index dropped to -56% to retail and recreation spaces and -57% to grocery and pharmacy areas.

The World Health Organization (WHO) (2020) has declared COVID-19 as a global pandemic on 11th March 2020, Rwanda was one of the first African countries to put in place measures that sought to halt the COVID-19 pandemic in its tracks and prevent health system being overloaded by COVID-19 patients which would ultimately have affected overall provision of health services. The country’s first recorded case of coronavirus was on March 14, 2020, and cases have risen sharply in July and December 2020. The Government has been implementing series of measures to ensure containment of COVID-19 spread the community and avoid the overwhelming situation for the health sector which were tailored to bi-weekly assessment.

Tewari et Al (2013) noted that SMEs represent over 90 percent of private business and contribute more than 50 percent of employment and Gross Domestic Products (GDP) in most African countries, furthermore, SMEs contribute about 40% of national income (GDP) in emerging economies and NISR (2018) through the establishment census showed that in Rwanda 99.7% of business fall under the category of micro, small and medium enterprises. Therefore, any disruption in economic activities has a direct effect on SMEs.

The impact of COVID-19 on the health sector and other socio-economic life of countries including Rwanda is unanimously accepted, the citizens, policymakers and international community have felt the magnitude of the effect of COVID-19 (World Bank, 2020; IMF, 2020; OECD, 2020; UNICEF, 2020; UNECA, 2020; UN, 2020; Bizoza & Sibomana, April 2020) and the literature about the effect of COVID has emerged immensely in recent months, in just a year, the google search (24th March 2021 at 7:47) using “Effect of Covid-19” billions of possible results, (4,860,000,000) while the narrow search by typing “Effect of COVID-19 on businesses” shows 978,000,000 publications and further trimming down to “ effects of COVID 19 on SMEs” still shows some millions of results as they stood at 5,120,000 publications relating to SMEs and COVID-19.

The proliferation of literature of COVID 19 on different spheres of life shows the magnitude of the issue the world has faced since early 2020. Beck and Cull, (2014) in their study on SMEs financing in Africa found that SMEs are most vulnerable when it comes to the inability to access needy financing, the regression results showed that smaller firms are less likely to access formal loans by 30%, while among small, and medium-size firms they are that rate ranges between 13% to 14% relative to large firms. According to ILO (2020), Most MSMEs are business entities that are often run by women, operate in drenched sectors of the informal sector and lack protection mechanisms, with these conditions MSMEs are believed to be the first to suffer devastating consequences of the economic downturn.

UN (2020) reported that Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) were likely to be among the most vulnerable business, following the imposition of travel bans, border closures, and quarantine measures. Many workers cannot move to their places of work or carry out their jobs, which has knock-on effects on incomes, particularly for informal and casually employed workers. This analysis on the COVID-19 effect on SMEs in Rwanda has been narrowed to the wood sub-sector due to the high level of heterogeneity characterizing the SMEs. Tewari et Al., (2013) noted that SMEs, account for a significant share of economic activity at any point of time and as a sector tends to be complex with large variation in firm size, age, are specialization, performance among other element variances which indicates that looking at them collectively hides important insight of higher policy relevance.

It is against the above backdrop that this study was sought to quantify the magnitude of COVID-19 effects on SMEs operating in the wood sub-sector in Rwandan context, through quantitative survey data identifying the recovery strategies and proposing actionable policy recommendations to strengthen SMEs resilience to shocks and foster employment potential in -post-COVID-19 era with particular emphasis on wood-based SMEs and their operators.

The main objective of the study is to analyse the impact of COVID-19 on SMEs in Rwanda with special emphasis on wood focused businesses, specifically, the analysis has helped to:

Model the effect of COVID-19 on sales, employment, and taxes of wood-based SMEs,

Identify the approach and mechanism applied by wood-based SMEs in the recovery process

Propose policy recommendations for SMEs resilience to shocks tailored to Wood-based businesses in Rwanda

2. Data and Methodology

2.1. Data

To analyse the impact of COVID-19 on wood-based SMEs in Rwanda, we have followed cross-sectional data collected between August- September 2020, this was the right period as the Government of Rwanda was embarking on gradual re-opening of the economy from what was total lock-down to relaxing people’s mobility and resumption of economic activities. The sample size was determined following the sample frame, provided by Rwanda Value Chain Wood association, and we followed the proximate Simple Random Sampling (SRS) technique to determine the optimal size which provided reliable and valid data to provide inference to overall SMEs at 95% confidence interval.

The following is the sampling formula:

Where : Minimum sample size, : Confidence interval (1.96), : 0.13 represent 13% relative precision and : our expected proportion 0.50.

By replacing the functions into the value, the required optimum sample size n was 227.

A team of 4 data collectors was deployed in different areas of wood processing centres from those with a big workshop to nursery trees businesses, across the country. The data collectors were introduced to the district by the Ministry of Trade and industry and in collaboration with the wood value chain association, to administer a designed questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of a different set of questions relating to SMEs’ conditions before lockdown, during the lockdown and right after lockdown. However, the businesses which did not open due to the COVID-19 effect or other reasons were not part of the assessment.

In Wood processing areas, or integrated Community Processing Centres (ICPCs): Upon arrival in the identified areas, researcher assistants had discussed with the head of cooperative (it is assumed that most wood processors belong to any form of cooperatives) and provided with them the lists of all members and choose randomly from that list. The research assistant has selected operators, thus head to their business location for the interview, it was possible that on a day of visit some identified business operators were not present to the business due to social distancing measures, in that respect, a second visit was planned, otherwise, the research assistant has decided to replace the identified personnel with the next business operators.

Selecting the respondents beyond the processing centres, the research assistants have applied the random walk methodology by using the commonly known place for furniture and other wood products workshops. This process was facilitated by the fact that assistants had adequate knowledge of the areas of operations which further contributed to accurate identification of the right respondents. To maximize the quality of the primary data collected, the team leader coordinated the work daily, the stronger supervision and coordination with researcher team, contributed to coming up well-balanced sampling in each category of business operators.

2.1. Methods for Data Analysis

The analysis framework has adopted an exploratory data analysis (EDA) which consists of analysing and investigating patters in the data sets and summarize their main characteristics, often employing data visualization methods. The EDA approach helped to quantify the direct effect of COVID-19 on SMEs because of Lcovid-19 preventions measures including lockdown which heavily disrupted businesses and other socio-economic operations. The effects were analysed at under three channels (i) the amounts of sales, (ii) the number of employments and (iii) the level of taxes by comparing before and after the outbreak of COVID-19 in Rwanda. To ascertain the significance of statistical impact, multiple regression with ordinary least square (OLS) regression model was applied (Gujarati, 2004).

The multiple regression of following form was used to analyse the significance of COVID-19 impact of SMEs in Rwanda:

Where is an independent variable, b0 is the intercept, bi is the parameter associated with and is error terms.

Estimating the Effect of COVID-19 on Employment

To Model the effect of COVID- 19 on SMEs sales, under the wood products sold between March-June 2019 and March-June 2020 were differentiated, thus,

Thus

Where, as employment level of March and May 2020 and as an employment level before lockdown namely March-May 2019. is the wood product sales in 2020 and is the wood product sales in 2019. is the dependent variable, measured a dynamic difference between two reference periods.

Therefore, fitted regression model is therefore made by the following variables;

Where,tax_after is the amount of tax paid between April and May 2020, Size_Entreprise is the dummy variable indicating the size of business (Small, medium and Large), experience is the experience the number of years the business has been in operations, Outstanding loan is the amount the business owns to other others and represent a financial obligation, Business_Plan is a categorical variable measuring the status of existence of a business plan in the business (existing plan and used by the business to access financing, existing and used for internal purposes only, and still being developed and non-existent business plan), Owner is the categorical variable indicating the ownership status (owned, cooperative, and partnership) and Sex is the dummy variable indicating the gender of the business owner (female vs male).

Fitted Model on COVID-19 on Employment Effect

To identify the employment effect, the reference period was set to the number of employees working in the business other than the owners and unpaid family members as of March 2020 and May 2020 (where the government has been implementing gradual re-opening of economic activities thus

Where, is the number of employees reported in May 2020, is the employees who were employed in March 2020 and is the dependent variable, obtained from the difference of the employment level between the reference periods.

Fitted Model on COVID-19 on Taxes Effect

To identify the effect of COVID-19 effect on SMEs, the reference period for tax amount paid by the business owners between December 2019 and January 2020 relative to the amount of taxes paid between April and May 2020.

Where, is the amount paid between December 2019 and January 2020, is the amount of tax paid between April and May 2020 and is the dependent variable measuring change of the taxes between the reference period.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Summary Statistics on Location and Demographic Characteristics

In total 244 SMEs operators were interviewed, from different areas of Rwanda. With Kigali areas (Gasabo, Kicukiro and Nyarugenge) accounting for more sampled businesses as they make almost half (48.4%) of sampled businesses. Other areas mainly districts were also represented by a marginally significant number of SMEs, Rubavu account for 7.4%, Karongi 7.0%, Musanze 6.2%. The least represented districts are Kamonyi and Nyabihu with 3.3% each and Rusizi with 2.9% (

Table 1). The Distribution of data by districts is also in line with the existence of Wood-centred SMEs where Kigali is the hub of many businesses.

The demographic analysis of SME owners shows that majority (47.1%) of business owners are under the category of 36-45 years old. This is consistent with the national average of active age in Rwanda population, 25% of SMEs owners are in 24-35 years old. The early young age (16-24 years old) of the sample SMEs operators is represented by 2.9%, while the old age business operators were represented by 7%; the analysis by marital status, shows that the business owners the wood sector are merely operated by married people (85.7%) while other marital status, such as single and widower represent a small proportion, namely 12.3% and 2.1% respectively. Further analysis by gender shows that there is big gender difference in the wood sector, with more dominance men (84.0%) versus of as women (16%). The big gender divide could be explained by the fact that, traditionally women were not involved in more physically demanding education trades such as masonry, carpentry, and other wood processing activities. The analysis of SMEs owners by the level of education shows that, a high percentage of respondents completed secondary education (46.3%), followed by those who have completed only primary education (29.1%) and the Tertiary education (Post-secondary diploma) is represented by 11.5%. Regarding business ownership, sole owned enterprises account for 72.1% among the surveyed, while cooperative business constitutes 20.1%. regarding the years of experience, the data show that most of surveyed business were very young as almost two in three 3 businesses have just between 2 and 5 years of existence (40.9%), the business with between 5- 10 years of experience account for 27% (

Table 2).

3.2. Summary Statistics on Business Size before and after COVID

The survey captured the data on business turn-over recorded in 2019, and the data were self-reporting the business owners, the data collectors, however, did not make counter verification to explore the exactness of the reported. The research assumed that since the questions were in the interval scale it was easy for the SMEs owners to remember the range of the business annual turnover. As a result, majority of the respondents (42.9%) of reported a turnover ranging between FRW 2,000,000 and FRW 12,000,000, followed by those who indicated that their annual turnover was below FRW 2 million or US

$2,000 and represent 40.1% of all surveyed businesses. Besides, 83% of surveyed businesses are classified as small, 12.4% medium enterprises and 4.5% were large enterprises (

Table 3). Recalling that Micro Small Medium Enterprises in Rwanda are categorized as follows, FRW 0.3 to FRW 12 Million are small enterprises, medium-size enterprises, were FRW 12 million to FRW 50 million while large enterprises have annual turnover of more than 50 million (MINICOM, 2010). According to Rwanda Development Board (RDB), micro-businesses account for 97.8% of all private sector.

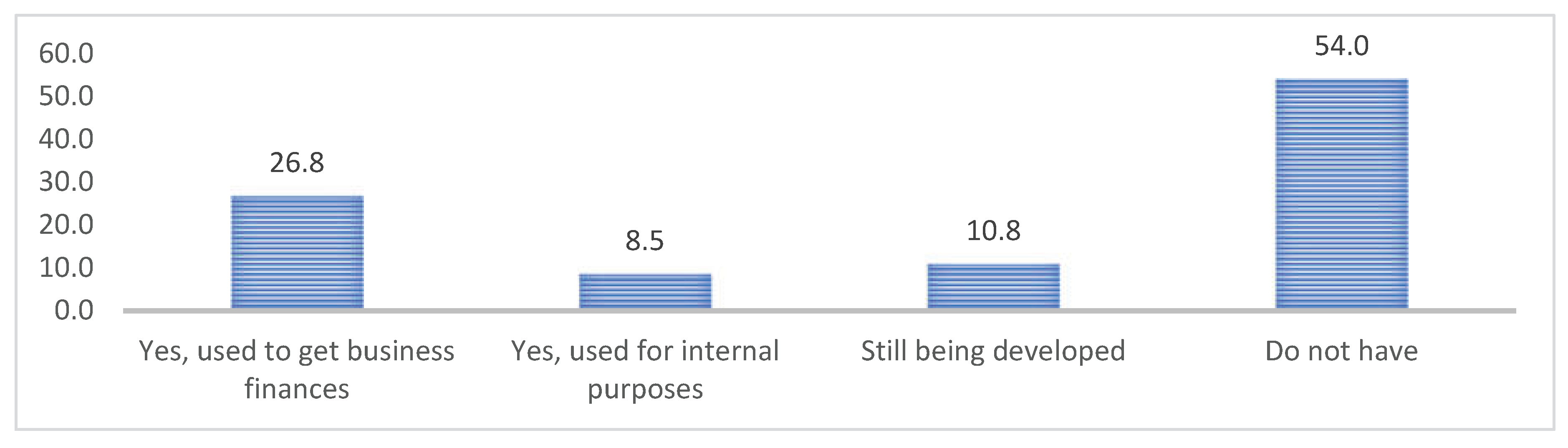

According to the Professional Accountants in Business Committee (2006), Business plans is a strategic instrument that has a duo role, from one hand it serves as an external sight that is used to obtain funding that is essential for the development and growth of the business, and internally serves to provide a plan for early strategic and corporate development. Among the surveyed businesses, shows that (

Figure 1), 26% have developed business plans and were used to access funding, 10% are still developing the business plans while almost half of the SMEs do not have the business plans.

Across business size, the data show that only large businesses have and use business plans access finances as reported by 80%, that rate reduces among medium-size enterprises with 65.2% and further decline substantively among small business as only 18.8% indicated that they have their business plans and were used to access business finances, 6.9% have business used for internal purposes only, and a majority 61.7% reported that they do not have businesses plans (

Table 4). Lack of business increases SMEs’ vulnerability as they can’t project internal projections for growth and fail to access financings due to a lack of important information on business growth prospects.

With regard to the number of years of experience in business, the data show that the mean age was 9.4 (±10.62std) years, but to adjust with large deviation, we observed that the median age of surveyed enterprises was 6 years, while the minimum number of years of business operation was just less than a year while the maximum was 64 years.

To understand the implication of COVID-19 SMEs in Rwanda, it is important to know the length of lockdown i.e., the time at which businesses were not in operational due to full implementation of virus containment to limit large scale transmission to the large community. In that respect, the data show that the average number of days for lock-down was 53.8 (± 18.9std) with the maximum days of business, closure was 109 days or 30% of the working days per year. These reported numbers of lockdowns are consistent with the national guidelines on business closure between March-May 2020.

3.3. The Effect of COVID-19 on SMEs

The analysis of the effect of COVID-19 on SMEs in Rwanda is structured around three main themes, mainly (i) sales, (ii) taxes and (iii) employment.

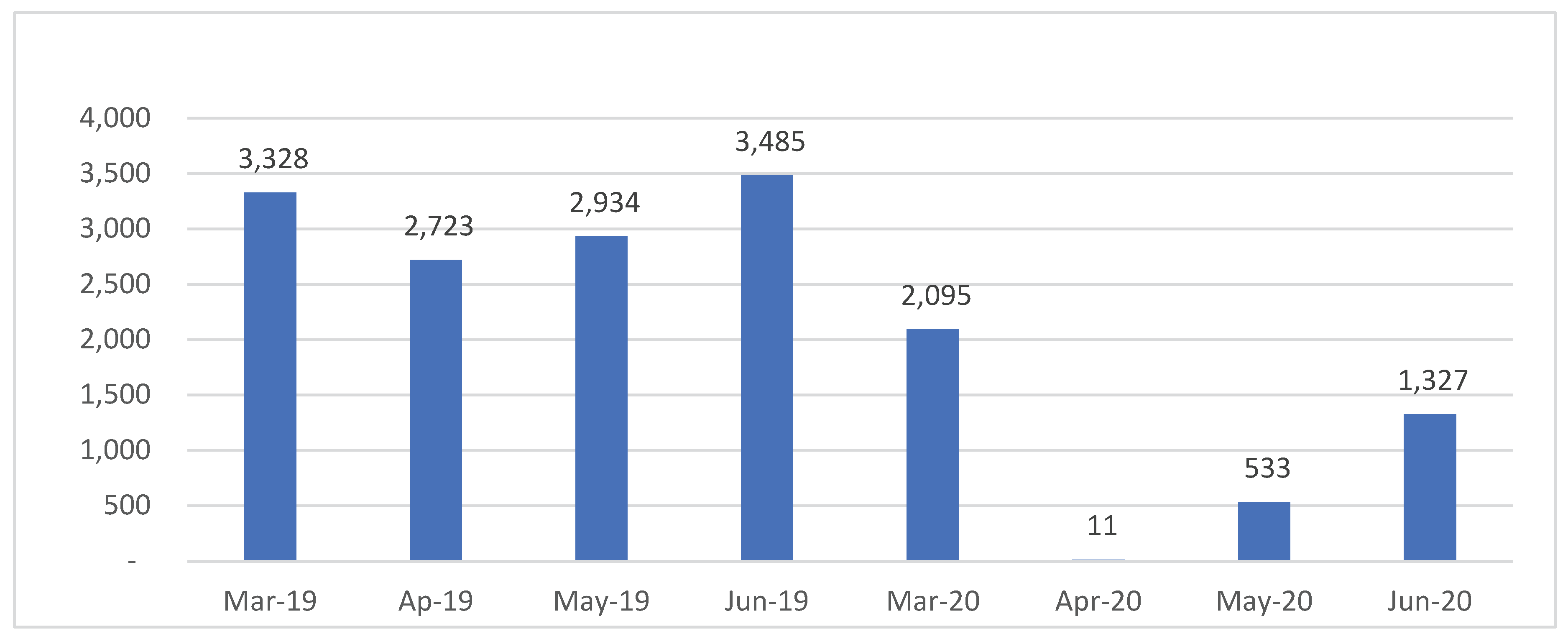

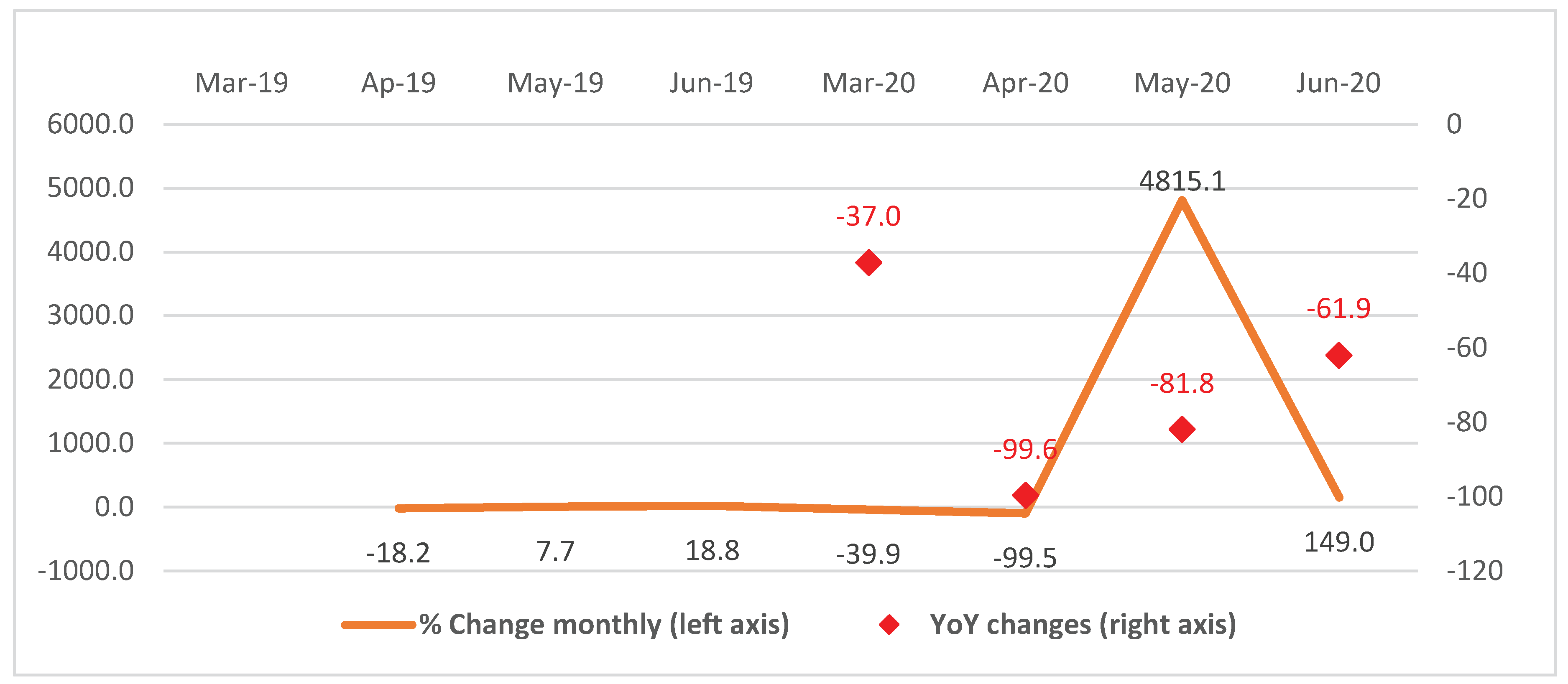

3.2.1. Effects on Business Sales

The guidelines for lockdown have indicated that, only essentials businesses were allowed to remain open, those were limited only to those SMEs operating in pharmaceuticals, sanitation and food provision. The data from surveyed businesses (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) shows that relative to 2019 data, there has been a drastic downward trend from FRW 3.3 million average sales in March 2019 to FRW 2.09 million average sales reflecting a decrease of -37 percent year on year analysis, the fall has further deepened in April 2020 with the sales declining to about -99% with only 11,000 sales, against 2.3 million sales in April 2019. However, the sales recovered in May 2020 with the decrease starting to reduce to -81.8 percent, the average sales reported was 533, 000 vs 2.9 million in the same month of 2019 and further negative sales were reported in June 2020, the change of -61.9 percent with the average sales of FRW1.3 million against FRW 3.4 million in 2019. The decline was a result of the country’s gradual opening strategy.

3.2.2. Effect on Taxes Paid

As early discussed, the government has announced series of fiscal measures to support businesses and households to cope with the financial shocks. To measure the effect of COVID-19, we took two months (December 2019 and January 2020) proceeding the lockdown, and two months of lockdown namely April and May of 2020.

Table 5 shows that the taxes paid by SMEs reduced by -44.2% percent in April and further -20.7% among the round timber sales, among those who trade processed timbers, there has been a reduction in tax paid by -24.6% . However, among the intermediately processed timbers such as joineries which are used for construction, recorded a high reduction of paid tax by -43.8% in April and further reduction to 81.2% in May 2020, among distributors of wood final products such as furniture, and other items, the reported tax payment contracted to -24.9% in April 2020 and further on -100.3 percent in May 2020 (

Table 5). The distributional effect of COIVID-19 on the tax differs across wood operations with a high effect among the high-end operators relative to the lower-level wood operators.

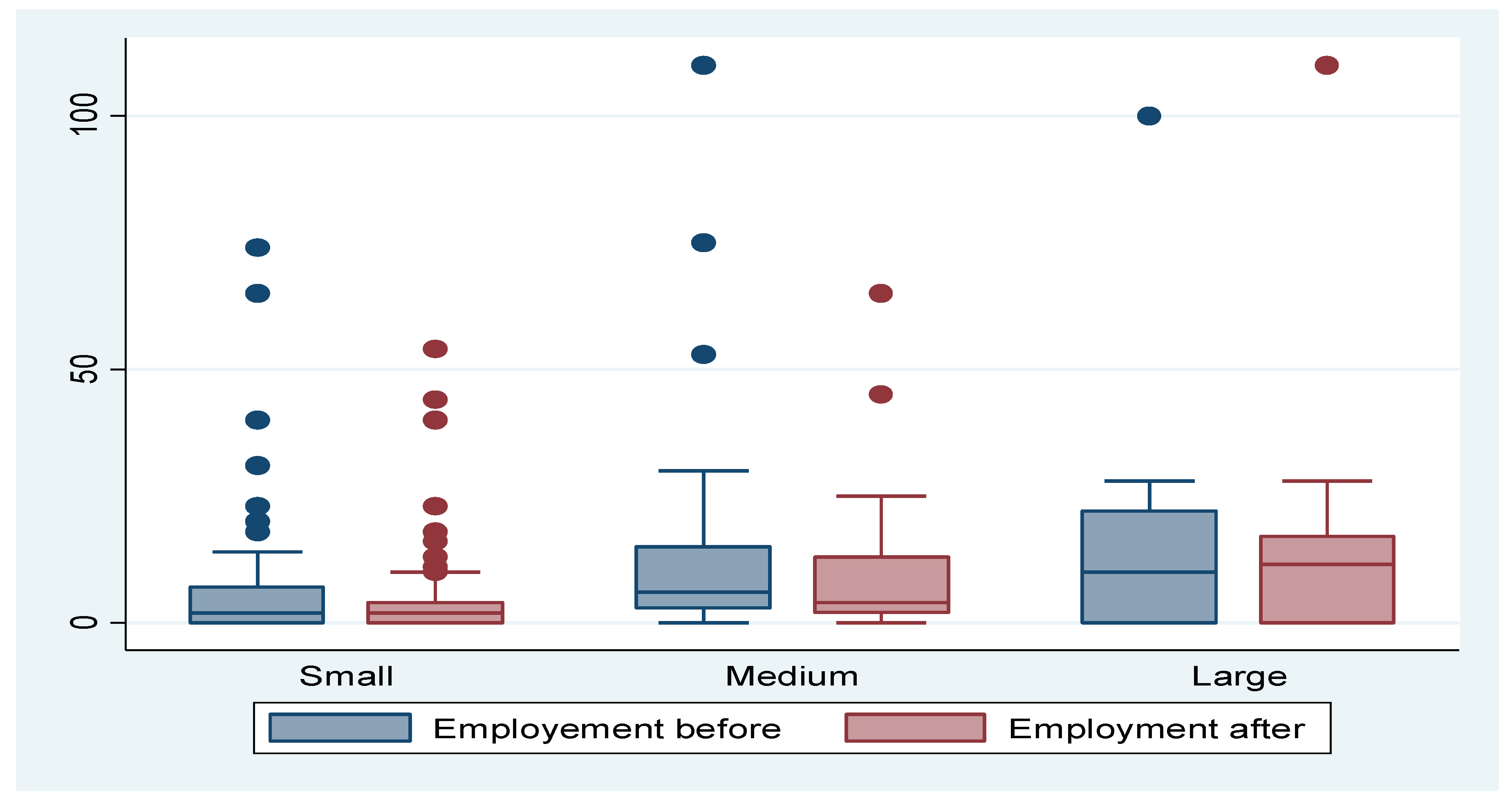

3.2.3. Effects on Level of Employment

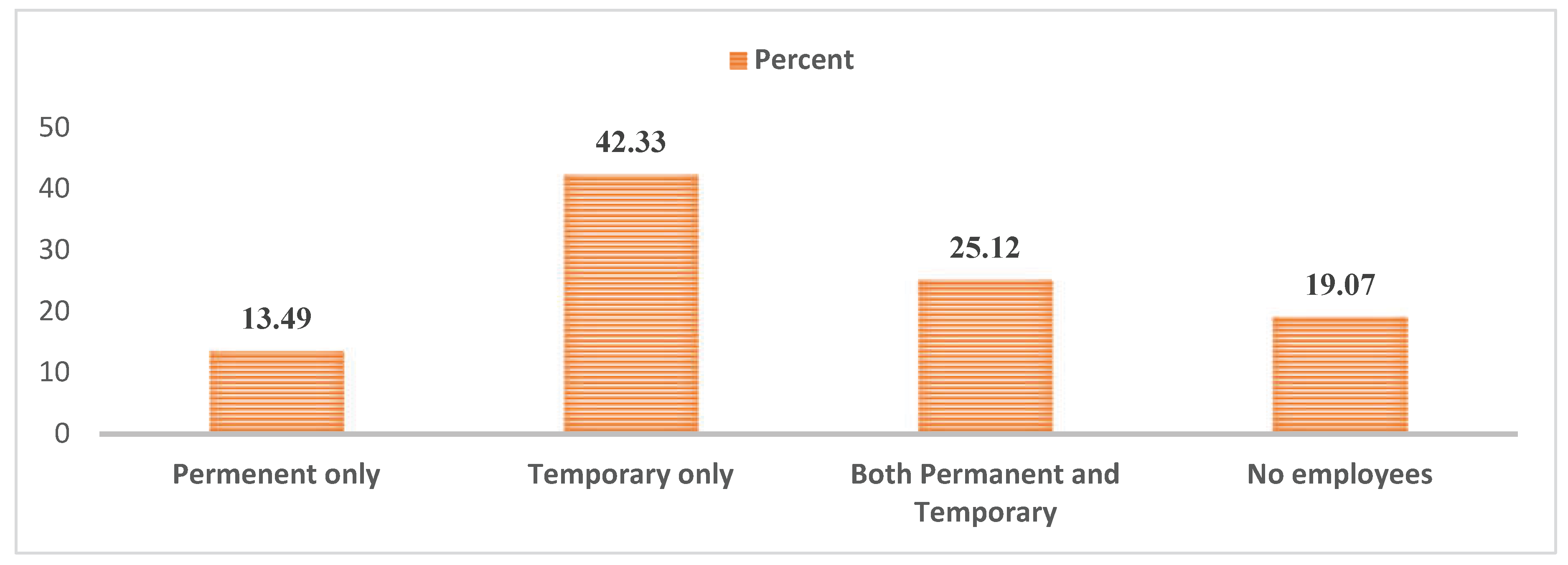

In total, 81% of surveyed businesses had at least one employee, other than the business owner.

Figure 4 shows that SMEs employ mainly temporally employees, (42.3%) who are called on a need basis, the survey data show that 1 in 4 SMEs utilize both temporary and permanent employees. And 13.5% had only permanent employees, however, 19% of surveyed businesses employ no employees, which indicates that the business owner is the sole person working for the business and helped by the family members (

Figure 4).

To understand the magnitude of employment change, we compared before lockdown the level of employment and after May employment (during the gradual opening period) and found out that, the business with less than 5 employees overall were not significantly affected by employment change as they reported positive change of 33.3%, however, this was because business with more than 5 employees downsized the number of employees, there has -35.9% reduction in employment among the businesses with 5-10 employees, and -24% among the business with 10-30 employees, and among the business which employs, more than 50 employees (both permanent and temporary combined) recorded a negative change of -36.4 percent. The average COVID-19 effect on employment is estimated at 12.6% among wood businesses in Rwanda.

Table 6.

SMEs level Employment trends.

Table 6.

SMEs level Employment trends.

| Levels of employees |

Before March 2020 |

After May 2020 |

Diff (%) |

| Freq. |

% |

Freq. |

% |

| Less than 5 |

72 |

48 |

96 |

64 |

33.3 |

| Between 5 and 10 |

39 |

26 |

25 |

16.67 |

-35.9 |

| Between 10 and 30 |

25 |

16.67 |

19 |

12.67 |

-24.0 |

| Between 30 and 50 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

0.0 |

| Above 50 |

11 |

7.33 |

7 |

4.67 |

-36.4 |

| Total |

150 |

100 |

150 |

100 |

-12.6 |

The analysis shows the following distribution of the relative effect of employment on each category of business in

Table 7.

Number of obs = 217

Wald chi2= 7.02

Prob > chi2 = 0.0300

Log pseudolikelihood = -145.71768

Pseudo R2 = 0.0258

COVID-19 has had a higher magnitude and negative effect among the small businesses with -1.17 less likelihood relative to medium-size enterprises, contrary, during the opening period, medium-size enterprises had more likelihood (+1.17) to employ people relative to small enterprises. Both findings for small and medium were significant at 0.05 significant level. Among the large enterprises, there was a -1.3 less likelihood to employ more people, relative to medium-size enterprises. The analysis of the employment effect among large enterprises versus small enterprises shows non-significant results, thus were omitted in the table. However, as descriptive data demonstrated, in the early opening, large enterprises and medium started with a small number of employees, because of gathering restrictions and uncertainty amid the crisis, therefore, a longer-term analysis of employment effect is strongly recommended both in the wood and non-wood subsector of SMEs.

Figure 5.

Employment status before and during lock-down. Source: survey data analysed.

Figure 5.

Employment status before and during lock-down. Source: survey data analysed.

3.2.4. Regression Findings

Multivariate analysis, (

Table 8) confirms the statistically significant effect of COVID-19 on employment among SMEs and highlight a statistically significant (0.05 sig. level) relationship between employment effect with level of taxes owed after lockdown with -1.2 marginal effect, the size of enterprises as earlier discussed with -5.5 marginal points, the type of business ownership with -7.14, more marginal effects among cooperative type relative to the operators who do not belong to any cooperative business arrangements, however, the employment effect was positively related with owning business plan with +0.68 likelihood, indicating that the companies which had a business plan were 0.68 units more likely to be employment resilient during Covid-19 relative to the business with no business plans.

Regarding the COVID-19 effect on sales, there is enough evidence that there has been a drastic effect, among SMEs in the wood sub-sector, however, the data not depict statistically significant variation concerning the magnitude of the effect on other time invariant attributes, such as, gender of the business owner, type of business ownership, owning business plan, business experience (years of existence), and amount of taxes paid, however, there is a significant variation of effect on sales with regard to the size of enterprises (large business), which their sales level declined by -3.4 marginal unit, relative to small and medium enterprises. Overall, there has been an even distribution of effects across different dynamics of the enterprises.

Regarding the effect of COVID on tax, unlike sales, which negatively relates to outcome by -0.0126 marginal points, namely any unit drop of sale has contributed to the fall of tax by -0.012 percent points, other variables seemed not to be statistically significant, therefore the COVID-19 effect on SMEs tax is smoothly distributed across SMEs by their varying characteristics.

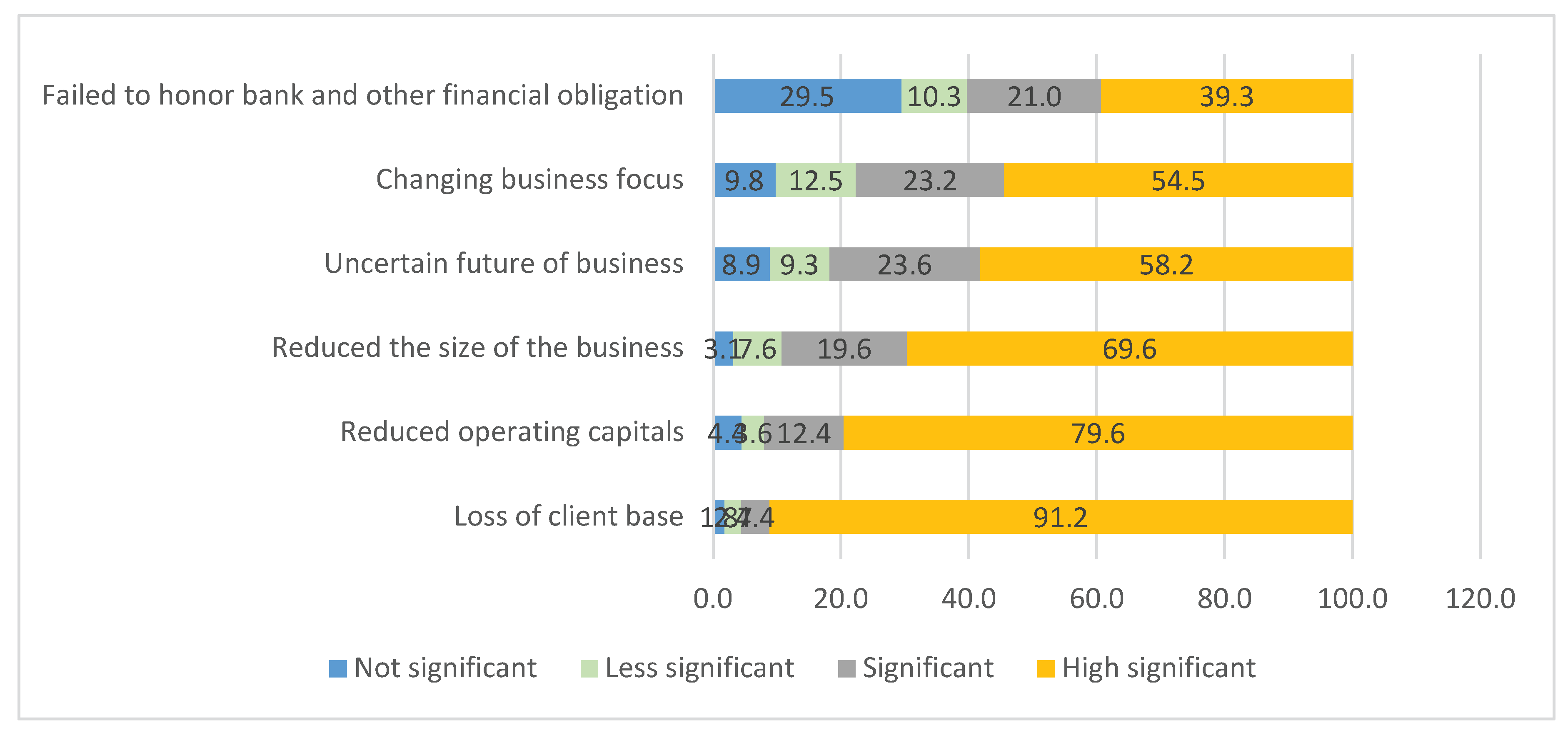

3.2.5. Other Reported Effect of COVID-19 on SMEs

The business owners were requested to provide their perception on other likely that COVID-19 has caused to them, and the following areas come out as the key impact which severely affected SMEs, loss of client base which was reported by 91.2%, followed by reduction of operating capital which as indicated by 79.6% and the reduction of the size of the business as reported by 69.6%, however, more than a half (60.3%) of the respondents noted that they failed to honour bank or other financial obligations as consequences of COVID-19 and their associated prevention measures (

Figure 6)

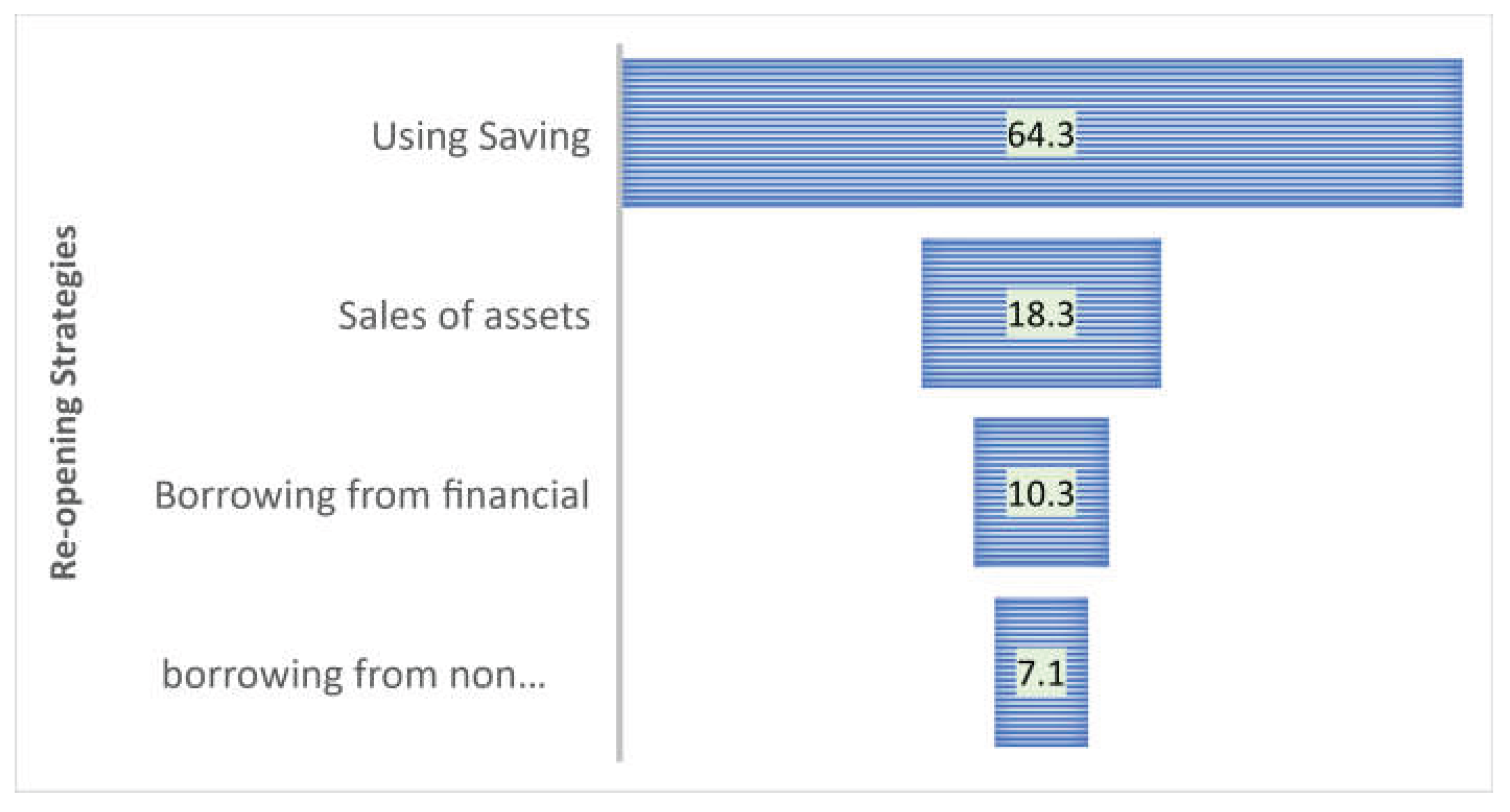

3.2.6. Reopening Strategy

Recalling that after more than six weeks of intense lockdown, the government has started to put in place gradual measures for re-opening, businesses were also to re-open. Building on the above findings, which indicated that the capital was depleted, and employment was severely affected, along with uncertain future of business, companies have adopted various measures to re-open, the data in

Figure 7 show that majority of SME operators had to opt for using their saving 64.3%, and sizable proportion of business operators has to undertake sales of their assets (18.3%) and borrowing from financial institutions account for 10.3%.

Open strategies among SMEs statistically differ when related to years of experience (operational time), with Pr = 0.008 against 0.05 significance levels as, among those with less than 2 years of experience, 50% used their saving, while those with 5 to 10 years 72.7% used the savings and those with 10 to 15 years of experience 50% used savings while 42.9% opted for borrowing in financing institutions. However, 1 in 5 SMEs has opted to sell the assets including homes to be able to re-open the businesses. With regard to the size, there is a statistical difference among the options used to re-open, however large proportion of large and medium-size enterprises have used for saving with 83.3% and 82.2% respectively while, among the small size businesses, 60.1% used saving, 20.8% have opted for selling some of the cumulated assets including homes (

Table 8)

Table 10.

SMEs Opening strategy by select variables.

Table 10.

SMEs Opening strategy by select variables.

| Indicator |

Detailed metrics |

Open strategy |

| Using Sav |

Borrowing IFIs |

Borrowing N-FIs |

Sales of assets including homes |

Total |

| Size of enterprises |

Small |

60.4 |

11.88 |

6.93 |

20.79 |

100 |

| Medium |

82.35 |

0 |

11.76 |

5.88 |

100 |

| Large |

83.33 |

16.67 |

0.000 |

0 |

100 |

| Years of business experience |

< 2 years |

50.0 |

0.0 |

30.0 |

20.0 |

100 |

| 2 and 5 Years |

67.4 |

10.2 |

6.1 |

16.3 |

100 |

| Between 5 and 10 year |

72.7 |

3.0 |

6.1 |

18.2 |

100 |

| 10 and 15 year |

50.0 |

42.9 |

0.0 |

7.1 |

100 |

| > 15 Years |

66.7 |

6.7 |

6.7 |

20.0 |

100 |

| Gender |

Male |

67.31 |

10.58 |

7.69 |

14.42 |

100 |

| Female |

50 |

9.09 |

4.55 |

36.36 |

100 |

4. Conclusion and Policy Recommendation

The analysis of the effect of COVID-19 on SMEs in Rwanda shows that the secondary effect from COVID-19 and associated measures have impacted wood operators in different dimensions. The effect was recorded, particularly on employment, because data show that SMEs had opted to downsize their employment levels, the level of sales, relative to those recorded in 2019 were severely affected, down to closer to zero value of sales in April of 2020 which is viewed as the peak period of lockdown effects and on taxes, there has been a slight decline in the amount taxes paid by different wood operators.

The findings from this study are consistent with other countries experience which went into lockdown, Oyewale, Adebayo & Kehinde, (n,a) in their study on estimating the Impact of COVID-19 on Small and Medium Scale Enterprise in Nigeria, found out that that majority of the entrepreneurs have been affected (both severely and slightly) by the COVID-19 pandemics through the partial and total lockdown and movement restrictions, and the effect was much higher among the non-agriculture sector, which is the case for Rwanda. a similar study conducted in Kenya (Siddiqui et Al., 2020), also showed that MSMEs have been facing unprecedented income losses and uncertainties about their future because of business disruptions due to the outbreak of COVID-19, and the effect has been more perverse because MSMEs lack financial reserves to meet needy expenses during emergencies like in lockdown.

The re-opening strategies were diversified when the Government of Rwanda started to lift some of the containment measures, the SMEs had a personalized approach to address each company’s unique needs to better re-open with most of the companies trying to rely on. However, the Government of Rwanda through its economic recovery which earlier discussed, there is financing instruments put in place to accompany the SMEs and large corporation to be ably embarking on rapid recovery.

Given the above, the following policy actions are recommended to ensure stronger SMEs resilience, foster employment creation thus accelerates SMEs’ return to the pre-COVID-19 situation.

To ensure sustainable access to business financing, SME operators should be given special consideration and prioritization to access to the government financing facilities to accelerate their operations and reach pre-COVID-19. Furthermore, the Private sector federations and Wood operators should establish additional financing support, to complement the governments financing, to avail adequate and affordable financing among SMEs

Saving has proven to be a primary source of support, as SMEs re-open, the Government in collaboration with wood associations, Private sector federation, banks will need to invest in promoting saving practices, to increase the SMEs readiness to face the future uncertainty. For Government, in particular, there is a need to develop complementary Ejo-Heza saving products tailored to SMEs’ needs, in addition to retirement models.

For the SME operators in the wood sub-sector, they should leverage conducive government policies, mainly those relating to Made in Rwanda promotion, and invest more in innovations and product diversification, to meet the market demand amid the constrained imports due to border closured and people’s movement restriction.

References

- African Union (April 2020) Impact of the Coronavirus Covid-19 on the African Economy, also available at. Available online: https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/38326-doc-covid-19_impact_on_african_economy.pdf.

- Bizoza A. & Sibomana. S, (28 Apr 2020), Indicative Socio-Economic Impacts of the Novel Coronavirus (Covid-19) Outbreak in Eastern Africa: Case of Rwanda, University of Rwanda, Kigali Rwanda. Also available at. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3586622.

- Fortune of Africa website at. Available online: https://fortuneofafrica.com/rwanda/micro-small-medium-enterprises-in-rwanda/.

- Gujarati, D. (2003). Basic Econometrics. 4th edition, McGraw- Hill, New York.

- International Labour Organization, (April 2020), ILO Enterprises, Brief Interventions to support enterprises during the COVID-19 pandemic and recovery Also available at. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---emp_ent/documents/publication/wcms_741870.pdf.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF), (June 2020), IMF Country Report No. 20/207, Washington, D.C. Also available at. Available online: http://www.imf.org.

- Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MINECOFIN), (2019), Economic Activity brief, Kigali- Rwanda.

- MINECOFIN, Macro Division, April 2020. Economic Activity brief, Kigali- Rwanda.

- MINICOM (2010). Rwanda Small and Medium Enterprises (SME) Development Policy, Kigali, Rwanda, June 2010 also available at. Available online: https://rwandatrade.rw/media/2010%20MINICOM%20SME%20Development%20Policy.pdf.

- National Bank of Rwanda, (August 2020), Monetary Policy And Financial Stability Statement, Kigali- Rwanda also available at. Available online: https://www.bnr.rw/news-publications/publications/monetary-policy-financial-stability-statement/.

- National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR), (2021), GDP National Accounts 2020, also available at. Available online: https://www.statistics.gov.rw/publication/gdp-national-accounts-2020.

- Oyewale, A. Adebayo, O, Kehinde, O. (n.a), Estimating the Impact of COVID-19 on Small and Medium Scale Enterprise: Evidence from Nigeria, Also available at. Available online: https://www.uneca.org/sites/default/files/AEC/2020/presentations/estimating_the_impact_of_covid-19_on_small_and_medium_scale_enterprise_-_evidence_from_nigeria_.pdf.

- Professional Accountants in Business Committee (2006). Business Planning Guide: Practical Applicationfor SMEs. International Federation of Accountants, Information Paper, May 2006 also available at. Available online: https://www.ifac.org/system/files/publications/files/business-planning-guide-pr.pdf.

- Siddiqui, D., Matibe, E., Obiero, O. & Singh, A. (2020), Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), Kenya report, July 2020. Also available at. Available online: https://www.microsave.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Impact-of-COVID-19-pandemic-on-MSMEs-Kenya.pdf.

- Tewari, P. S., Skilling, D., Kumar, P. & Wu, Z.(2013). Competitive Small and Medium Enterprises: A diagnostic to help design smart SME policy, The World Bank, Competitive Industries Global Practice, Washington DC, USA also available at. Available online: http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/534521468331785470/pdf/825160WP0P148100Box379861B00PUBLIC0.pdf.

- Tsanga, R., Ducenne, Q., Habimana, C., Brasseur, R. and Cerutti, O. P. (2019), Wood Supply Chain in Rwanda: A Market Analysis in Rwanda, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, Also available at. Available online: https://www.cifor.org/publications/pdf_files/Reports/GIZ-CIFOR_RwandaReport.pdf.

- United Nations, (2020) The Socio-Economic Impact Of Covid-19 In Rwanda, June 2020, Kigali Rwanda also available at. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/dam/rba/docs/COVID-19-CO-Response/UNDP-rba-COVID-assessment-Rwanda.pdf.

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) (2020). Economic Effects of the COVID-19 on Africa, Addis Ababa Ethiopia, (March 2020). Also Available at. Available online: https://www.icafrica.org/fr/news-events/infrastructure-news/article/economic-effects-of-the-covid-19-on-africa-by-uneca-672655/.

- World Health Organization (2020). Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemic.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).