1. Introduction

The catabolic pathway of the neurotransmitter γ-amino butyric acid (GABA) leads to production of succinic semialdehyde (SSA) that is normally converted into succinate by a mitochondrial enzyme, succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH, reviewed in [

1,

2]). In the absence of SSADH activity, SSA and GABA accumulate in the cells and in extracellular fluids [

3,

4]. In addition, a large fraction of SSA is converted into a toxic metabolite, γ-hydroxy butyric acid (GHB).

Impairment of SSADH activity is caused by mutations in the

ALDH5A1 gene that encodes the SSADH enzyme, resulting in the rare genetic disease SSADH deficiency (SSADH-D) [

5]. The patients usually suffer from a varying degree of mental retardation, behavioral problems with autistic features, muscle hypotonia, and lack of speech. Some SSADH-D patients also have epileptic seizures that can be very severe and may result in a sudden unexpected death in epilepsy [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Accumulation of the GABA metabolites is observed in the tissues and body fluids of the patients and can be used as a diagnostic tool. In addition, sequencing of the

ALDH5A1 gene is usually done to verify the diagnosis.

SSADH-D is a recessively inherited disease, in which a large spectrum of pathogenic

ALDH5A1 gene variants have been described [

1,

10,

11,

12]. However, there is only a poor genotype-phenotype correlation even within a single family. No major mutations that would be present in a high fraction of patients are known, and most patients have their private or family-specific pathogenic gene variants. In addition to a growing list of various pathogenic mutations in the

ALDH5A1 gene, a number of presumably benign single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) are listed in genetic databases, such as ClinVar and GnomAD [

13,

14]. This poses a problem for the genetic diagnosis of SSADH-D, as it is not always clear how significant a certain gene variant is for the impairment of SSADH activity.

One such

ALDH5A1 variant is c.538T>C, p.His180Tyr (SNP rs2760118), which is very common in the general population, with an allelic frequency of 0.348 [

15]. The His180Tyr variant was described to be benign, with only mildly reduced or near-normal enzyme activity in overexpression systems [

10,

11,

16]. However, it can exacerbate the effect of other amino acid substitutions that are present in the same allele of the

ALDH5A1 gene, such as the Pro182Leu (c.545C>T) variant. Pro182Leu alone is also not very harmful, but together with His180Tyr, it shows a more severe effect on the SSADH enzyme activity [

10]. Therefore, it is important to properly characterize all variants, including the seemingly benign ones that are present in a specific SSADH-D patient, before conclusions about the pathogenicity of the variants can be made.

In the present study, we describe an SSADH-D family with four

ALDH5A1 gene variants, including the known His180Tyr and Cys93Phe variants [

10], and two previously uncharacterized variants. We provide a thorough molecular and structural analysis of these variants, showing that Val90Ala and His180Tyr are benign variants, whereas Cys93Phe and Asn255Ala are pathogenic and result in a profound loss of SSADH protein expression and impairment of activity. We also show that treatment of cells expressing these variants with substances that enhance protein folding does not result in an improvement of SSADH expression or activity in the case of the above-mentioned pathogenic variants. Our data show that it is important to understand the molecular consequences of the potentially pathogenic variants as well their combinations, so that personalized precision therapies targeting patient-specific variants can be developed [

17].

3. Discussion

In the present study, we have provided a thorough structural and functional characterization of the SSADH variants found in a family of a patient with SSADH-D. Upon original genetic diagnosis, two of these variants, Val90Ala and His180Tyr, were declared as SNPs without any clinical relevance, even though Val90Ala was a novel, uncharacterized variant (i.e. a VUS), and His180Tyr was known to exacerbate the effect of further amino acid substitutions [

10,

11,

16]. The younger sister of the index patient in this family was later found to be a heterozygous carrier of Cys93Phe (paternal) and Val90Ala (maternal) variants. Therefore, it was important to characterize the molecular effects of the variants found in the family. The Val90Ala variant showed a WT-like expression and activity, thus confirming its non-pathogenic nature.

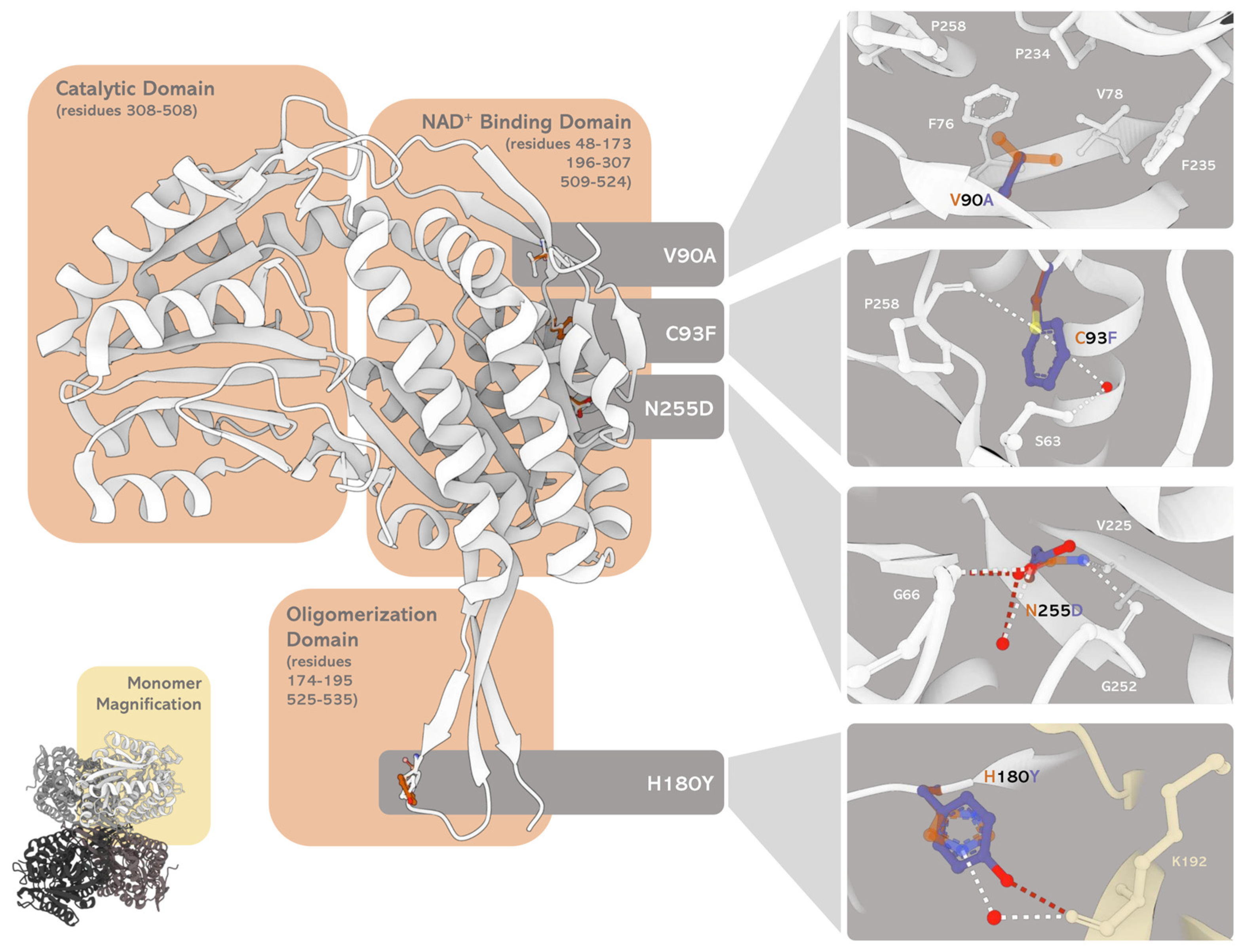

The Cys93Phe and Asn255Asp variants, located within the NAD

+ binding domain, exhibited not only a highly reduced SSADH enzyme activity, but also a very low level of protein expression in eukaryotic cells, including patient fibroblasts. Akaboshi et al. have experimentally shown that the Cys93Phe variant shows a very low (3% of WT) activity in a transient overexpression system, but the protein expression level was not assessed [

10]. Pop et al. have studied another substitution at this site, Cys93Arg, showing that this variant exhibited only a very low residual enzyme activity, but they did not study the protein expression level [

11]. Exchange of Cys93 to Phe (or Arg) perturbs several hydrogen bonds within the cofactor binding domain, resulting in structural destabilization of these SSADH variants, as also previously predicted [

12,

20]. In addition, the Cys93Phe exchange also causes a high degree of steric hindrance within the monomeric SSADH structure, contributing to the structural destabilization of this variant [

12]. Our studies show that the Cys93Phe substitution not only impairs the enzyme activity, but also profoundly perturbs the protein expression of this variant, consistent with the predicted structural aberrations and destabilization caused by this substitution.

Asn255 is a highly conserved residue within the NAD

+ binding domain, and the Asn255Asp substitution causes a rearrangement of hydrogen bonds that are required for the stabilization of a central β-sheet. Consistently, the enzyme activity and the protein level were very low, and the variant was insoluble in bacterial expression systems, pointing to a profound structural destabilization by the Asn255Asp substitution. In addition to a local effect within the NAD

+ binding domain, this substitution is also likely to cause further structural rearrangements within the polypeptide chain, which may even result in destabilization or loss of the tetrameric SSADH structure. Notably, several previously described, severe pathogenic variants also map in this region, including Gly252Cys, Gly252Val, Asn255Ser and Gly268Glu [

10,

12,

20]. However, the Asn255Ser variant was shown to exhibit 17% of the WT SSADH activity in a transient overexpression system [

10], but its protein expression level has not been studied. It is possible that the Ser substitution of Asn255 shows a milder structural perturbation than Asn255Asp, but its molecular consequences should be verified in a stable, low-level overexpression system, such as used in our study and by Popp et al. [

11].

In our SSADH-D patient, the Asn255Asp substitution was found in the same allele together with a His180Tyr amino acid exchange, resulting in an exchange of two amino acids within the SSADH polypeptide. The His180Tyr variant alone has only a very mild effect on SSADH activity and shows a normal protein level (present study), with similar findings from previous studies [

10,

16]. Thus, this variant, found with a high frequency within the population [

15], is

per se not pathogenic. However, as shown previously, it may exacerbate the effect of further missense variants found within the same polypeptide chain, as shown previously for the Pro182Leu variant alone (44% residual activity) and in combination with His180Tyr (36% activity) [

10]. In the case of our SSADH-D patient, the Asn255Asp substitution alone is already very severe, and His180Tyr does not further perturb the activity or expression of this variant. In eukaryotic expression systems, a very low activity and protein level are detected for the His180Tyr/Asn255Asp variant, similarly to the single Asn255Asp substitution. In fact, even though the Asn255Asp recombinant SSADH protein was insoluble in bacteria, the double-substituted His180Tyr/Asn255Asp species was stable and could be structurally assessed in our study. The His180Tyr/Asn255Asp variant exhibits a highly decreased affinity for NAD

+, which can be attributed to the Asn255Asp substitution. Therefore, the low activity of this variant as a recombinant protein is probably due to inefficient cofactor binding, whereas in eukaryotic cells, the protein expression is also disturbed.

We here show that the reason for the high, WT-like SSADH activity of the His180Tyr variant is due to the fact that it does not cause a major structural perturbation. His180 resides within a region that is involved in the tetramerization of SSADH monomers. The hydrogen bond formed by His180 through a bridging water molecule with Lys192’ residue in an adjacent monomer is retained in the His180Tyr variant, as the hydroxyl group of Tyr180 is at a hydrogen bonding distance from Lys192’ of the neighboring subunit. However, further amino acid exchanges in the same polypeptide chain, e.g. Pro182Leu, may result in additional structural defects, such as impaired tetramerization.

As a mitochondrial protein, SSADH is transported in an unfolded state into the mitochondria, and only folds after reaching the matrix. The folding of mitochondrial proteins is supported by molecular chaperones that belong to the Hsp family [

31]. We therefore attempted to increase the expression of Hsp proteins with two clinically relevant compounds, arimoclomol and celastrol [

32,

33,

34]. In addition, betaine, a chemical chaperone that supports protein folding, was used. The rationale behind the treatment was that these compounds would be able to support the folding of the pathogenic SSADH variants, and thus result in an increased SSADH activity. Unfortunately, none of these compounds showed a significant effect on the expression or activity of SSADH in patient fibroblasts and in the knock-in expression system. In patient fibroblasts, a very small but non-significant increase in the activity was observed after 48 h of treatment, but a clear increase in the protein amount was not visible. Considering that the Asn255Asp variant shows an impaired cofactor binding, it may not be possible to reactivate this variant. The Cys93Phe variant could theoretically be more amenable to folding aids, as Cys93 is buried deep within the SSADH structure, and its exchange is likely to cause a structural effect, instead of directly impairing NAD

+ binding. However, no significant improvement of activity was observed upon treatment with the three compounds. It is also possible that the compounds used were not able to reach mitochondria, thus being unable to stabilize SSADH folding. Therefore, further compounds should be identified that may be capable of supporting the expression and folding of specific pathogenic SSADH variants.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. SSADH Deficiency Patient

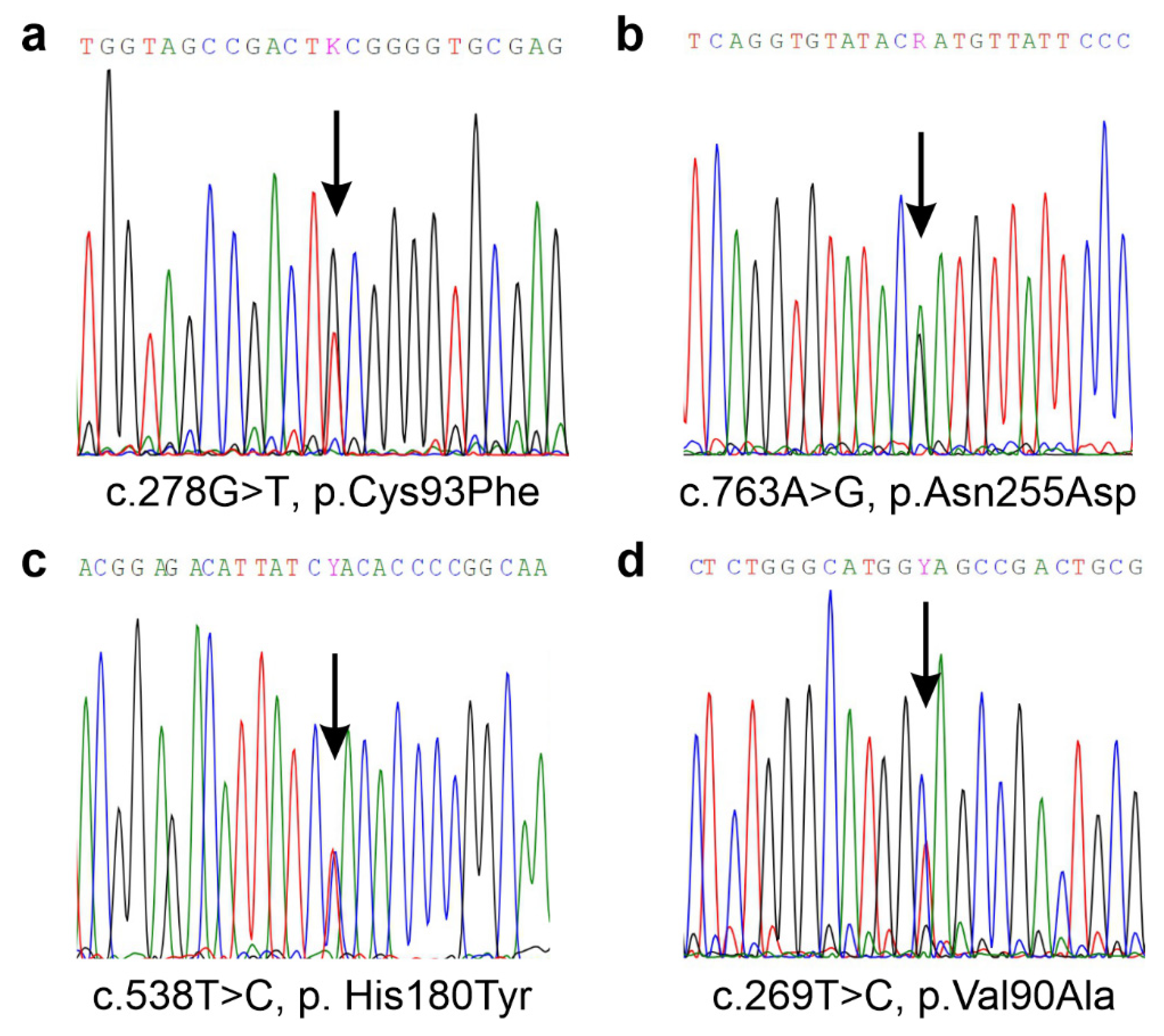

A 7-year-old, male German SSADH deficiency patient from a non-consanguineous marriage was diagnosed with SSADH-D, and the family was found to exhibit the following genetic variants in the ALDH5A1 gene: c.269T>C, p.Val90Ala (maternal); c.278G>T, p.Cys93Phe; c.538T>C (paternal), p.His180Tyr, and c.763A>G, p.Asn255Asp (both maternal). The parents provided a signed informed consent for the study.

4.2. Chemicals

Succinic semialdehyde (SSA), succinic acid (SA), oxidized (NAD+) and reduced (NADH) nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), poly-L-lysine, betaine and SigmaFast inhibitor cocktail were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Anti-SSADH and anti-His antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Heidelberg, Germany). ROTI®Mount FluorCare DAPI and 2-mercaptoethanol were from Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany). Hygromycin B was from Applichem GmbH (Darmstadt, Germany), and MACSfectinTM transfection reagent was from Miltenyi Biotech (Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Puromycin, zeocin, Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit antibody and Mitotracker Orange were from Invitrogen/Thermo Fischer Scientific GmbH (Darmstadt, Germany). Further chemicals were of the highest purity available.

4.3. Site Directed Mutagenesis of SSADH Expression Constructs

Human

ALDH5A1 open reading frame (ORF) and 36 bases of the 5’ untranslated region were cloned from pCDNA3 into pcDNA5/FRT vector (Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany). The constructs were used as templates for a PCR-based, site-directed mutagenesis using the Quick-Change II Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies, Frankfurt am Main, Germany) to generate the SSADH missense variants Val90Ala, Cys93Phe; His180Tyr; Asn255Asp; and His180Tyr/Asn255Asp. The oligonucleotides used for the mutagenesis are shown in

Table 1. All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing of the complete ORF.

The ORF of human SSADH, without the mitochondrial targeting sequence (amino acids 1-47), was cloned with NdeI and XhoI recognition sequences into pET15b (Novagen, Life Science/Merck; Darmstadt, Germany), immediately adjacent to the N-terminal His-tag and the thrombin cleavage sequence. The oligonucleotides used for the mutagenesis are shown in

Table 2. The constructs were verified by sequencing.

4.4. Eukaryotic Cell Culture

Human embryonic kidney (HEK-293T) and Flp-In

TM-293 cells (Invitrogen/Thermo Fischer Scientific) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (all from Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cell cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 8% CO

2. Patient-derived skin fibroblasts of the SSADH deficiency patient harboring the above-described variants were obtained from a punch biopsy. Immortalized healthy human skin fibroblasts were used as a control [

35]. All fibroblasts were cultured in DMEM (high glucose) medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% non-essential amino acids, and 1% sodium pyruvate (all from Thermo Fischer Scientific), and grown at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 8% CO

2.

4.5. Generation of an SSADH-Deficient ALDH5A1 Knockout Flp-InTM-293 Cell Line

ALDH5A1 knockout cells (single cell clones) were generated using the same strategy as described previously [

18]. Briefly, gRNAs for the exon 3 of the human

ALDH5A1 gene (NM_001080.3) were cloned in the PX459 vector (Addgene: Cat.Nr.: 48139, Watertown, MA, USA). The gRNAs with the sequences 5'-CACCGGATGACTGCAGCCACGCCTA-3' (fwd) and 5'-AAACTAGGCGTGGCTGCAGTCATCC-3' (rev) were designed using the E-Crisp design tool [

36]. The vector with the gRNA was used for the transfection of Flp-In

TM-293 cells cells. The cells were first seeded onto 6-well plates in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin and transfected with 1 μg SSADH-gRNA-PX459 and MACSfectin

TM reagent (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 24 h, the cells were supplemented with 2 μg/ml puromycin and cultured for additional 48 h. The surviving cells were then seeded as single cells onto 96-well plates and expanded for further analysis. The knockout was confirmed by Western blot and PCR-based sequencing of the genomic DNA.

4.6. Generation of Stable SSADH Knock-in Cell Lines

Flp-InTM-293 cell lines expressing WT SSADH or one of the SSADH variants (Cys93Phe, Asn255Asp, His180Tyr or Asn255Asp/His180Tyr) were generated according to the Flp-In system manual (Thermo Fischer Scientific). The Flp Recombination Target (FRT) site present in the genome of the Flp-InTM-293 cells and in the expression vector pcDNA5/FRT allows for a stable genomic integration of the gene of interest by means of a Flp recombinase-mediated DNA recombination. The FRT site in Flp-InTM-293 cells is inserted downstream of a lacZ-Zeocin fusion gene. After the recombination, the cells lose the zeocin resistance and gain a hygromycin resistance, which can be used for the selection of single-cell clones. The SSADH-deficient Flp-InTM-293 ALDH5A1 knockout cells were cotransfected with the pOG44 plasmid (expressing the Flp-recombinase) and the pcDNA5/FRT vectors with the SSADH variants (9:1 ratio). At 48 h post-transfection, the cells received 100 μg/ml hygromycin for additional 4 days. The hygromycin-resistant colonies were seeded onto 12-well plates, expanded, and analyzed further by western blot and PCR-based sequencing of the genomic DNA.

4.7. Transient Overexpression

Two hundred thousand HEK-293T and HEK-293T ALDH5A1-KO cells were seeded onto 6-well tissue culture plates in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin. Next day, the cells were transfected with 1 µg of pcDNA3 carrying either WT SSADH or Val90Ala, Cys93Phe, His180Tyr, Asn255Asp, or the double His180Tyr/Asn255Asp SSADH variant using MACSfectinTM reagent (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After 48 h, the cells were solubilized in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 2 mM ethylenediamine-tetraacetic acid (EDTA); 1% NP-40), and the protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

4.8. Treatment of the Cells with Betaine and Hsp-Inducing Agents

SSADH-deficient ALDH5A1 knockout Flp-InTM-293 cells stably expressing one of the SSADH variants and patient-derived fibroblasts were seeded onto 6-well culture plates and next day treated with 50 µM arimoclomol (Biosynth, Staad, Switzerland), 10 mM betaine (Sigma-Aldrich) or 250 nM celastrol (Selleckchem, Cologne, Germany). After 24 h or 48 h, the cell pelletss were frozen at -20°C.

4.9. Western Blotting

Prior to western blot, the cells were lysed in a lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 2 mM EDTA; 1% NP-40) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany). Protein lysates (1 µg) were separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, followed by transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking the membrane with 5% milk powder (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) in TBST, the membrane was probed with one of the following primary antibodies: anti-SSADH (1:10 000, ab 129017, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and anti-GAPDH (1:10 000, ab-8245, Abcam). Thereafter, the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies (Dako, Gostrup, Denmark). The final detection of proteins was performed using an Enhanced Chemiluminescence kit (SuperSignal™ West Femto/ Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The signals were detected with an Odyssey® XF Imaging System (LI-COR Biotechnology, Bad Homburg, Germany). The intensity of the SSADH signal was normalized to GAPDH.

4.10. SSADH Enzyme Activity

SSADH enzyme activity in the stable knock-in cell clones and their parental cells was analyzed by a fluorimetric assay as described previously [

18], with following modifications. Five hundred thousand cells were seeded onto a 6-well plate and solubilized in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 2 mM EDTA; 1% NP-40) one day later. The protein lysates (1 µg) were pipetted in duplicates into a flat-bottom 96-well plate and incubated overnight at 37°C with 90 µl of an enzyme reaction mix containing 90 mmol/l Tris, pH 8.4, 0.2 mmol/l SSA, and 3 mmol/l NAD

+. The SSADH-mediated reduction of NAD

+ to NADH was measured as an increase in absorbance at 340 nm. To deduce the activity of other NAD

+-reducing enzymes, the baseline values of samples incubated with a reaction mix without SSA were subtracted. Fluorescence was measured at an excitation wavelength of 355 nm and an emission wavelength of 470 nm with a TECAN Infinite 200 Microplate Reader (Tecan Group, Männedorf, Switzerland).

SSADH activity in the patient-derived fibroblasts was analyzed similarly, with modifications of the lysis procedure. Fibroblasts were first scraped into H2O, supplemented with 0.2 mM PMSF (Fluka Chemicals, Buchs, Switzerland) and 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol (Roth), and then sonicated (12 s at 90% amplitude) with Sonopuls Sonicator (Bendelin, Berlin, Germany). Ten µg of the protein lysate was used to measure SSADH activity.

4.11. Immunocytochemistry

For SSADH staining, fifty thousand fibroblasts were seeded on poly-L-lysine coated glass coverslips in a 12-well plate, and incubated on the following day for 30 min at 37°C with fresh medium containing 100 nM MitoTracker Orange (Invitrogen) to stain mitochondria. The cells were washed and fixed with ice-cold methanol for 10 min at -20°C, then blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 30 min at room temperature, followed by an 1 h incubation with a rabbit anti-SSADH antibody (1:100, ab129017, Abcam). After washing, the cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit antibodies (Invitrogen). The coverslips were subsequently mounted onto specimen slides with ROTI®Mount FluorCare DAPI (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany), and the samples were then imaged using an Aurox Clarity laser-free, spinning-disc confocal microscope (Aurox Ltd., Oxfordshire, UK) and the Visionary software (Aurox Ltd, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom). Image processing was performed using the ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

4.12. Bioinformatic Analyses

Conservation analyses were performed with the Consurf Server [

37] using the human SSADH amino acid sequence (isoform 2). A conservation score from 1 (variable residue) to 9 (conserved residue) was attributed to each residue. BindProfX [

21] was used to predict changes in the binding affinity upon the amino acid substitutions in the form of ΔΔG (change in free energy of binding) values. The algorithm combines the FoldX physics-based potential with the conservation scores from pairs of protein-protein interaction surface sequence profiles. Human SSADH crystal structure (PDB 2W8N) was superimposed with a structure obtained by

in silico mutagenesis of the selected residues by the software PyMOL (Schrödinger, Limited Liability Company; LLC).

4.13. Expression, Purification and Enzymatic Assays of the Recombinant SSADH Species

Prokaryotic SSADH expression constructs in the pET15b vector (see 4.3) were transformed in E. coli BL21 cells. Bacteria were grown at 37°C in a selective Luria-Bertani broth with 0.1 mg/ml of ampicillin. Protein expression was allowed to proceed over night at 30°C after induction with 0.1 mM IPTG. The bacterial pellet, collected by centrifugation, was resuspended in a buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, 20 mM imidazole, 500 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.5 mM PMSF, SIGMAFAST™ EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail, pH 7.40). Cell lysis was performed for 30 min at room temperature under constant agitation after adding lysozyme to a final concentration of 0.2 mg/ml. The suspension was then frozen in liquid nitrogen. After thawing, the suspension was treated with DNAse for 30 min under constant agitation, centrifuged, and the supernatant was loaded into a 5 ml HisTrap™ fast flow column (Cytiva, Global Life Sciences Solutions, Marlborough, MA, USA). A 50 min elution gradient was carried out for a single-step purification (flow 1 ml/min), with a second buffer containing 20 mM sodium phosphate, 500 mM imidazole, 500 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.40. The protein fractions were collected and dialyzed in 100 mM potassium phosphate, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 8.00. The activity was measured spectroscopically at 340 nm as the NADH formed in the reaction (εM= 6,220 M-1cm-1) following the addition of an enzymatic sample to a total of 0.35 ml of 10 µM SSA and 500 µM NAD+ in 100 mM potassium phosphate, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 8. The recombinant SSADH (amino acids 48-535) was then concentrated with Spin-X UF concentrators (Corning Inc., NY, USA) with cut-off 10 kDa, supplemented with 5% glycerol, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and finally stored at -80°C. SDS-PAGE was performed using 12% polyacrylamide gel to assess the purity of the recombinant SSADH. To assess the oligomerization state, size exclusion chromatography was carried out in 100 mM potassium phosphate and 150 mM NaCl, pH 8. Different concentrations (from 0.1 to 5 mg/ml) of recombinant WT and His180Tyr SSADH were loaded into a Superdex 200 (10/300) column (GE Healthcare, Boston, MA, USA) coupled to an ÄKTA Pure system (GE Healthcare), and the 280 nm signal was monitored.

4.14. Spectroscopic Analyses and Determination of the Equilibrium Dissociation Constant for NAD+

All spectroscopic measurements were carried out at 25°C in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 8, unless otherwise stated. Absorbance spectra were recorded with a Jasco V-550 spectrophotometer (Jasco Europe S.R.L., Milano, Italy), whereas intrinsic fluorescence emission analyses were carried out in a Jasco FP-750 spectrofluorimeter (Jasco Europe S.R.L) at 0.1 mg/ml SSADH, with 5 nm excitation and emission bandwidths upon excitation at 280 nm. Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were acquired in a Jasco J-710 spectropolarimeter (Jasco Europe S.R.L) at a scan speed of 50 nm/min with 2 nm bandwidth, using 0.1 mg/ml and 1 mg/ml protein concentrations for the far UV (190-250 nm) and near UV/visible (250-550 nm) range, respectively. Thermal denaturation was performed by monitoring the CD signal at 222 nm of 0.1 mg/ml SSADH species on a 25-90°C linear temperature gradient with a temperature slope of 1.5°C/min.

The equilibrium dissociation constant, K

D, for NAD

+ was calculated by plotting the change in the intrinsic fluorescence emission, following excitation of the enzyme at 280 nm, as a function of NAD

+ concentration and fitting it to the following equation:

where Y refers to the change of intrinsic fluorescence at each NAD

+ concentration, Y

max to the maximal change in the intrinsic fluorescence at the saturating NAD

+ concentration, and [E] refers to the monomeric SSADH concentration.

4.15. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the GraphPad Prism software (v. 5.02, La Jolla, CA, USA). The data are presented as mean values ± SD unless otherwise stated. Differences between two groups were tested using Student’s t-test. Comparison of multiple groups was performed by One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.T. and M.B.; methodology, M.D., S.C.; data validation, M.D., S.C.; Experimental investigation, M.D., S.C., S.F., N.T., I.B. and V.F.; data curation, M.D., S.C., M.B. and R.T.; writing—original draft preparation, R.T., M.B., M.D.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, M.D., S.C., M.B. and R.T.; supervision, M.B., and R.T.; project administration, M.B. and R.T.; funding acquisition, M.B. and R.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Sequencing results of the SSADH-D patient family revealed four different genetic variants that were all present in a compound heterozygous form. (a) Paternal variant c.278C>T, p.Cys93Phe and (b) maternal variant, c.763A>G, p.Asn255Asp that were found in the patient. (c) In the maternally inherited ALDH5A1 allele, an additional variant, c.538T>C, p.His180Tyr was detected. (d) A variant of unknown significance, c.269T>C, p.Val90Ala, was detected in the mother, but not in the patient.

Figure 1.

Sequencing results of the SSADH-D patient family revealed four different genetic variants that were all present in a compound heterozygous form. (a) Paternal variant c.278C>T, p.Cys93Phe and (b) maternal variant, c.763A>G, p.Asn255Asp that were found in the patient. (c) In the maternally inherited ALDH5A1 allele, an additional variant, c.538T>C, p.His180Tyr was detected. (d) A variant of unknown significance, c.269T>C, p.Val90Ala, was detected in the mother, but not in the patient.

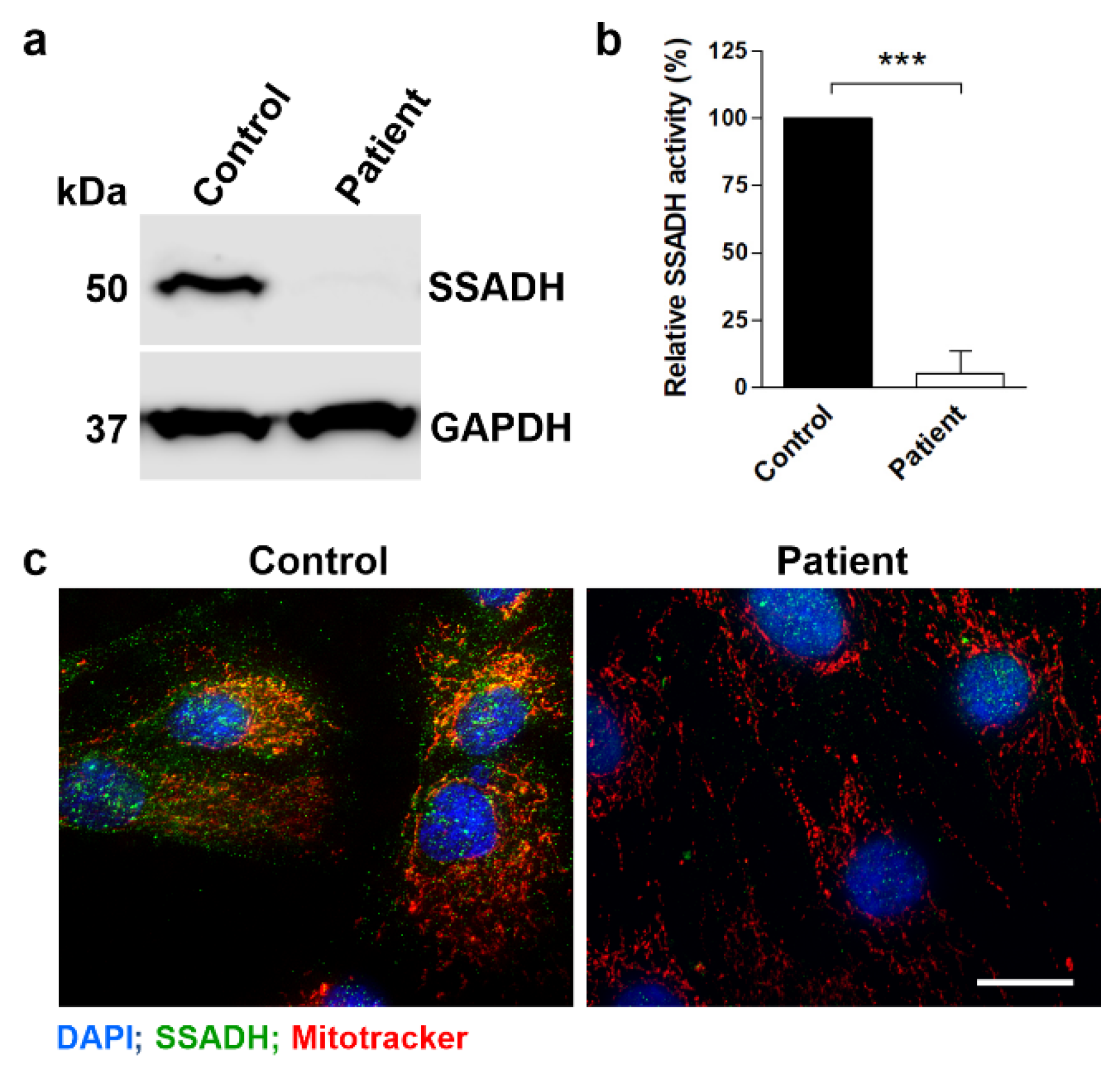

Figure 2.

SSADH protein expression, activity and localization in control and patient fibroblast cultures. (a) SSADH protein expression in control and patient fibroblasts. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Representative Western blots are shown (n = 3). (b) Relative SSADH enzyme activity was assessed by a fluorometric assay. Control fibroblast activity was set to 100%. Data are expressed as mean values ± SD (n = 3). *** p ≤ 0.001 (Student’s t-test). (c) Fluorescent images of control and patient fibroblasts stained with an anti-SSADH antibody (green) and MitoTracker (red) for visualization of mitochondria. Scale bar 20 μm.

Figure 2.

SSADH protein expression, activity and localization in control and patient fibroblast cultures. (a) SSADH protein expression in control and patient fibroblasts. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Representative Western blots are shown (n = 3). (b) Relative SSADH enzyme activity was assessed by a fluorometric assay. Control fibroblast activity was set to 100%. Data are expressed as mean values ± SD (n = 3). *** p ≤ 0.001 (Student’s t-test). (c) Fluorescent images of control and patient fibroblasts stained with an anti-SSADH antibody (green) and MitoTracker (red) for visualization of mitochondria. Scale bar 20 μm.

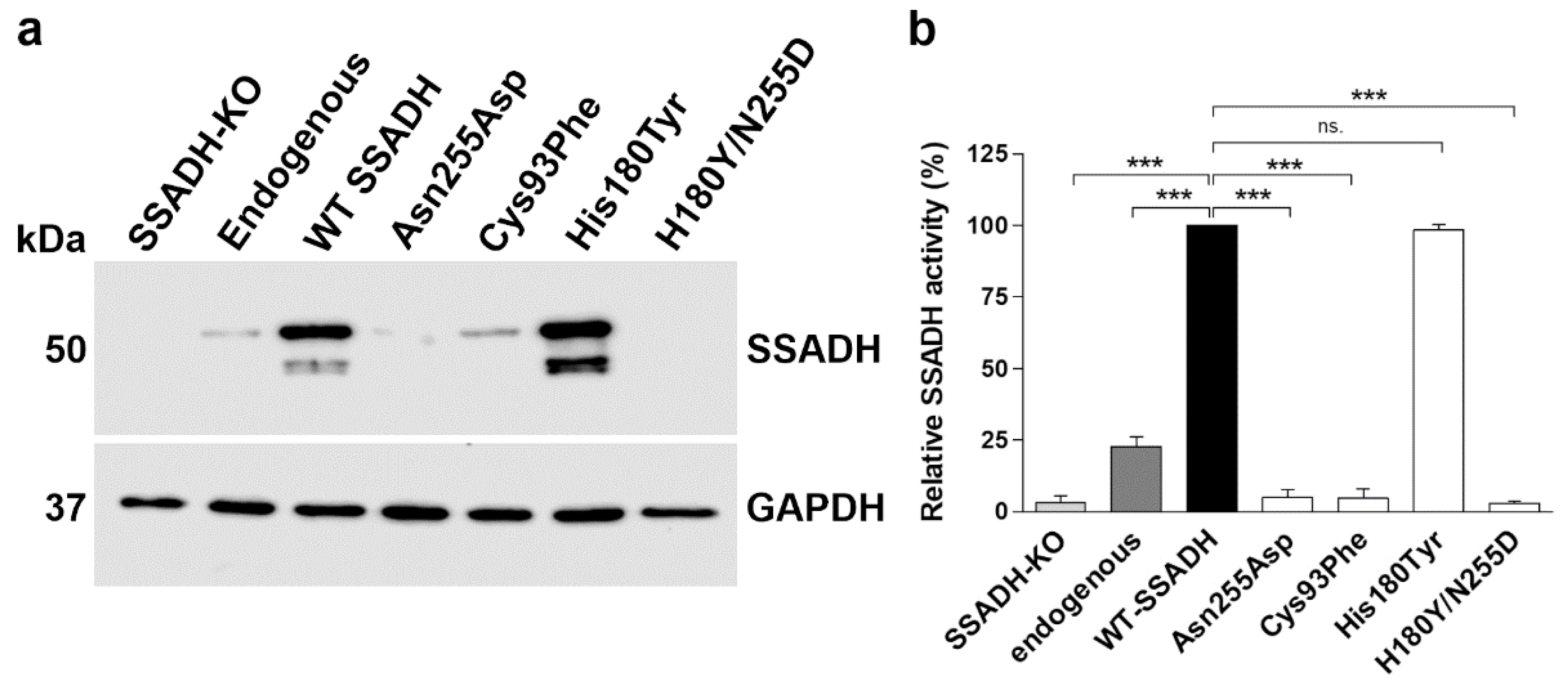

Figure 3.

In vitro characterization of SSADH deficiency patient variants in a transient overexpression system. HEK-293T ALDH5A1 knockout (SSADH-KO) cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA 3 vector carrying either WT or Val90Ala, Cys93Phe, His180Tyr, Asn255Asp or His180Tyr/Asn255Asp SSADH variant. After 48 h, cell lysates were prepared and (a) subjected to Western blotting. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Representative Western blots are shown (n = 3). (b) SSADH activity of SSADH-KO HEK-293T cells overexpressing WT SSADH was set to 100%, the variant activities are expressed as % WT. Data are expressed as mean values ± SD (n = 3). *** p ≤ 0.001, ns. = non-significant (One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test).

Figure 3.

In vitro characterization of SSADH deficiency patient variants in a transient overexpression system. HEK-293T ALDH5A1 knockout (SSADH-KO) cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA 3 vector carrying either WT or Val90Ala, Cys93Phe, His180Tyr, Asn255Asp or His180Tyr/Asn255Asp SSADH variant. After 48 h, cell lysates were prepared and (a) subjected to Western blotting. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Representative Western blots are shown (n = 3). (b) SSADH activity of SSADH-KO HEK-293T cells overexpressing WT SSADH was set to 100%, the variant activities are expressed as % WT. Data are expressed as mean values ± SD (n = 3). *** p ≤ 0.001, ns. = non-significant (One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test).

Figure 4.

In vitro characterization of the SSADH-D patient variants in a knock-in system. (a) SSADH protein expression and (b) relative SSADH enzyme activity in SSADH-deficient Flp-InTM-293 cells (SSADH-KO), Flp-InTM-293 (with endogenous SSADH) and in SSADH-KO Flp-InTM-293 cells with a genomic integration of either the WT SSADH or one of the SSADH variants (Asn255Asp, Cys93Phe, His180Tyr or Asn255Asp/His180Tyr). (a) Expression of SSADH variants. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Representative Western blots are shown (n = 3). (b) SSADH enzyme activity of SSADH-KO Flp-InTM-293 cells stably expressing WT SSADH was set to 100%, and the variant activities are expressed as % WT. Data are expressed as mean values ± SD (n = 3). *** p ≤ 0.001, ns. = non-significant (One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test).

Figure 4.

In vitro characterization of the SSADH-D patient variants in a knock-in system. (a) SSADH protein expression and (b) relative SSADH enzyme activity in SSADH-deficient Flp-InTM-293 cells (SSADH-KO), Flp-InTM-293 (with endogenous SSADH) and in SSADH-KO Flp-InTM-293 cells with a genomic integration of either the WT SSADH or one of the SSADH variants (Asn255Asp, Cys93Phe, His180Tyr or Asn255Asp/His180Tyr). (a) Expression of SSADH variants. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Representative Western blots are shown (n = 3). (b) SSADH enzyme activity of SSADH-KO Flp-InTM-293 cells stably expressing WT SSADH was set to 100%, and the variant activities are expressed as % WT. Data are expressed as mean values ± SD (n = 3). *** p ≤ 0.001, ns. = non-significant (One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test).

Figure 5.

Oligomeric and monomeric structures of human SSADH and the variants. Human SSADH crystal structure (PDB 2W8N) has been superimposed with a structure obtained by in silico mutagenesis of the selected residues by the software PyMOL (Schrödinger, LLC.). The four insets represent the microenvironment and interaction network changes induced by the substituted amino acids (i.e. V90A, C93F, N255D, and H180Y, from top to bottom) as compared to the WT. The variant residues (in blue) are superimposed to the corresponding WT residue (in dark orange). The dashed lines represent the new and lost contacts formed by the residues, respectively, in red (variant) and white (WT). Red dots represent water molecules.The image was built by MOL* [

22].

Figure 5.

Oligomeric and monomeric structures of human SSADH and the variants. Human SSADH crystal structure (PDB 2W8N) has been superimposed with a structure obtained by in silico mutagenesis of the selected residues by the software PyMOL (Schrödinger, LLC.). The four insets represent the microenvironment and interaction network changes induced by the substituted amino acids (i.e. V90A, C93F, N255D, and H180Y, from top to bottom) as compared to the WT. The variant residues (in blue) are superimposed to the corresponding WT residue (in dark orange). The dashed lines represent the new and lost contacts formed by the residues, respectively, in red (variant) and white (WT). Red dots represent water molecules.The image was built by MOL* [

22].

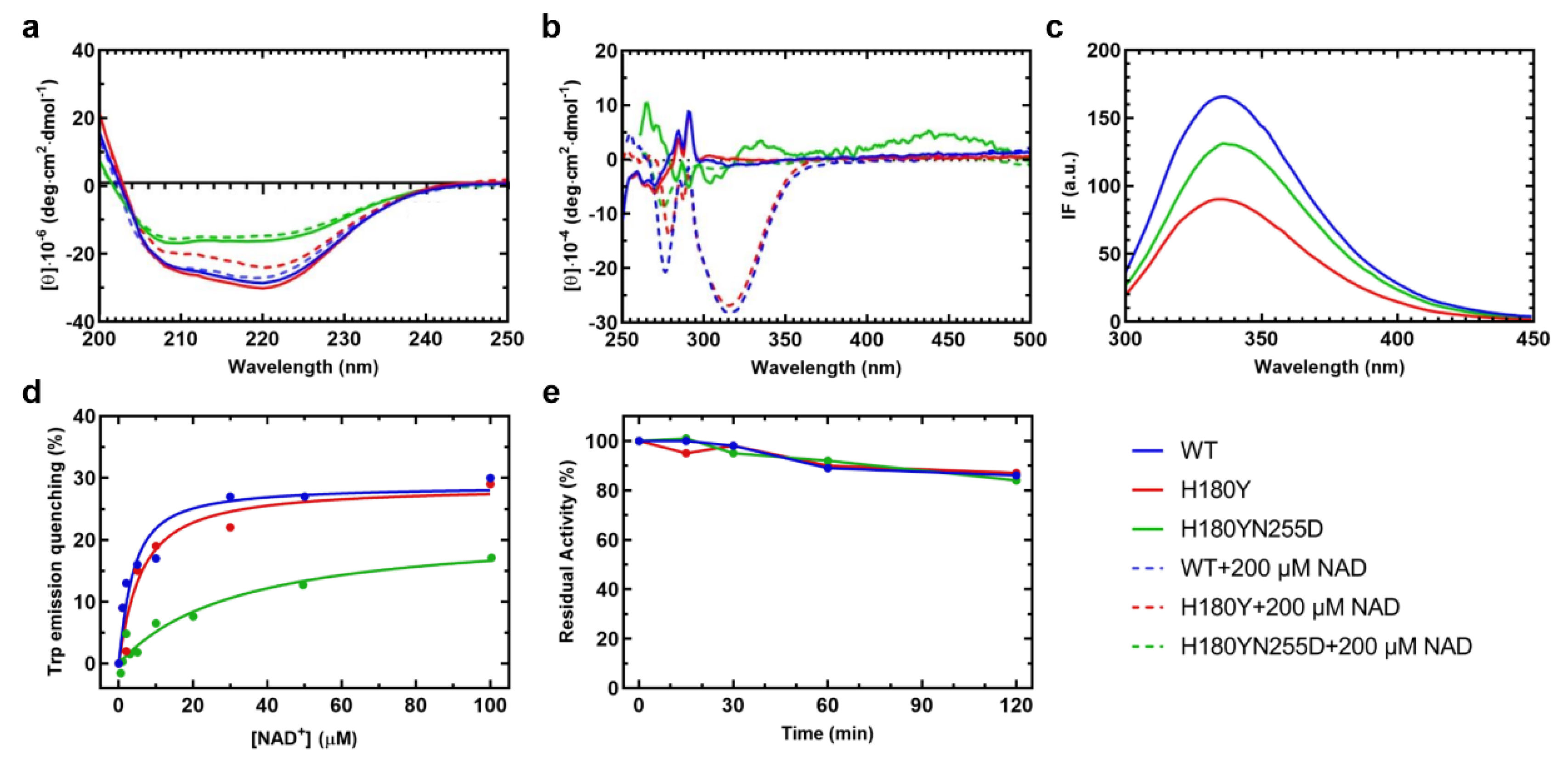

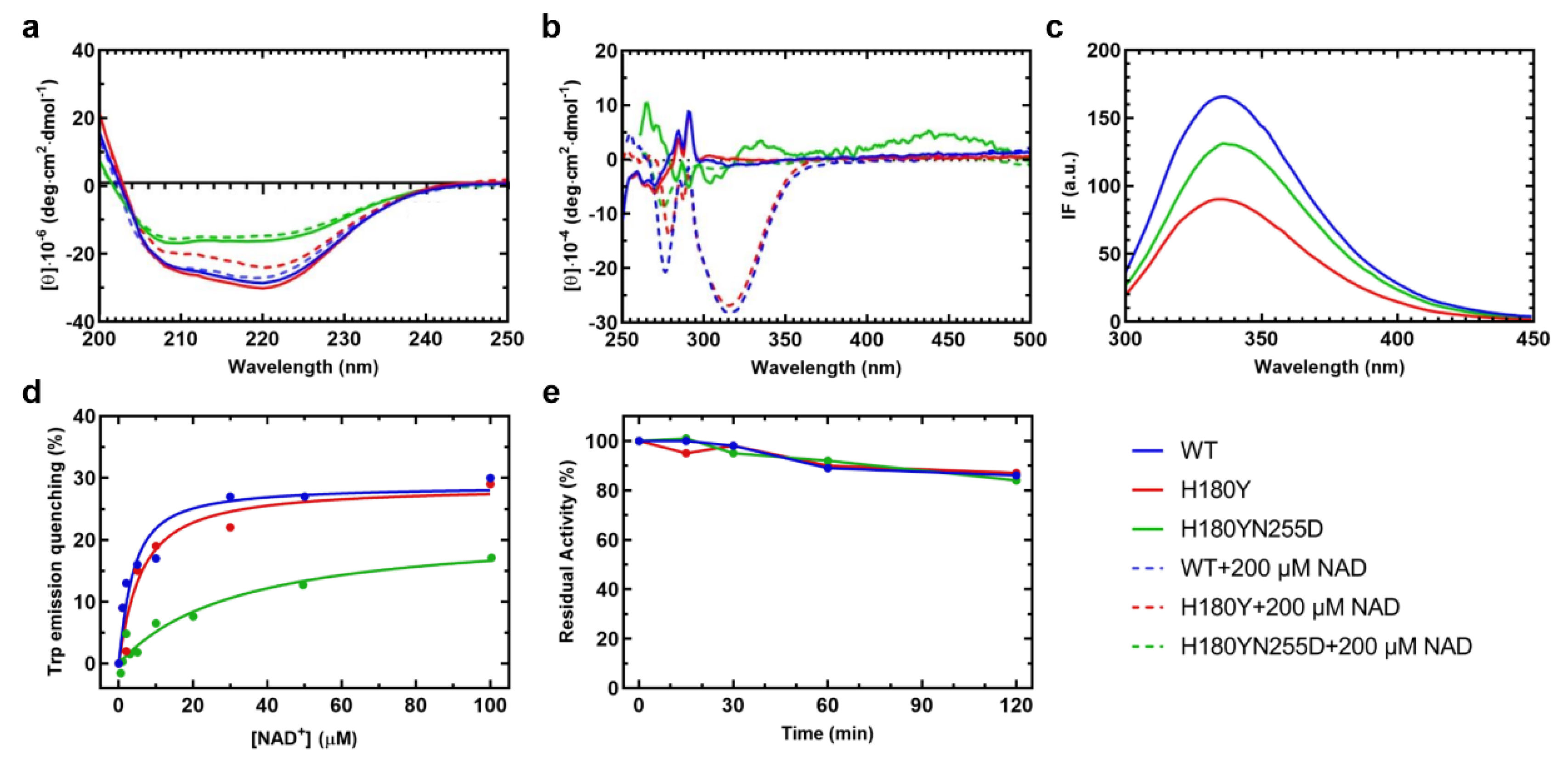

Figure 6.

Spectroscopic signals and apparent equilibrium dissociation constants for NAD+, and time course of reactions of WT (blue line), H180Y (red) and H180Y/N255D (green) SSADH variants. (a) Far-UV and (b) near-UV/visible circular dichroism (CD) spectra of the WT SSADH and the variants. Enzyme concentration was 0.1 mg/ml for far-UV and 1 mg/ml for near-UV/visible CD in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 8. Spectra of unliganded (straight line) and NAD+-bound (dashed line) enzyme species are reported (c) Emission fluorescence intensity of WT and the variant SSADH species at 0.1 mg/ml, following excitation at 280 nm in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 8. (d) Data for the calculation of the apparent equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) for NAD+, calculated as reported in chapter 4.15. (e) Loss of residual activity over time of the dehydrogenase reaction catalyzed by the WT and the variant SSADH species. The activity of each species at the beginning (timepoint 0) was set to 100% and the decline was monitored over time.

Figure 6.

Spectroscopic signals and apparent equilibrium dissociation constants for NAD+, and time course of reactions of WT (blue line), H180Y (red) and H180Y/N255D (green) SSADH variants. (a) Far-UV and (b) near-UV/visible circular dichroism (CD) spectra of the WT SSADH and the variants. Enzyme concentration was 0.1 mg/ml for far-UV and 1 mg/ml for near-UV/visible CD in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 8. Spectra of unliganded (straight line) and NAD+-bound (dashed line) enzyme species are reported (c) Emission fluorescence intensity of WT and the variant SSADH species at 0.1 mg/ml, following excitation at 280 nm in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 8. (d) Data for the calculation of the apparent equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) for NAD+, calculated as reported in chapter 4.15. (e) Loss of residual activity over time of the dehydrogenase reaction catalyzed by the WT and the variant SSADH species. The activity of each species at the beginning (timepoint 0) was set to 100% and the decline was monitored over time.

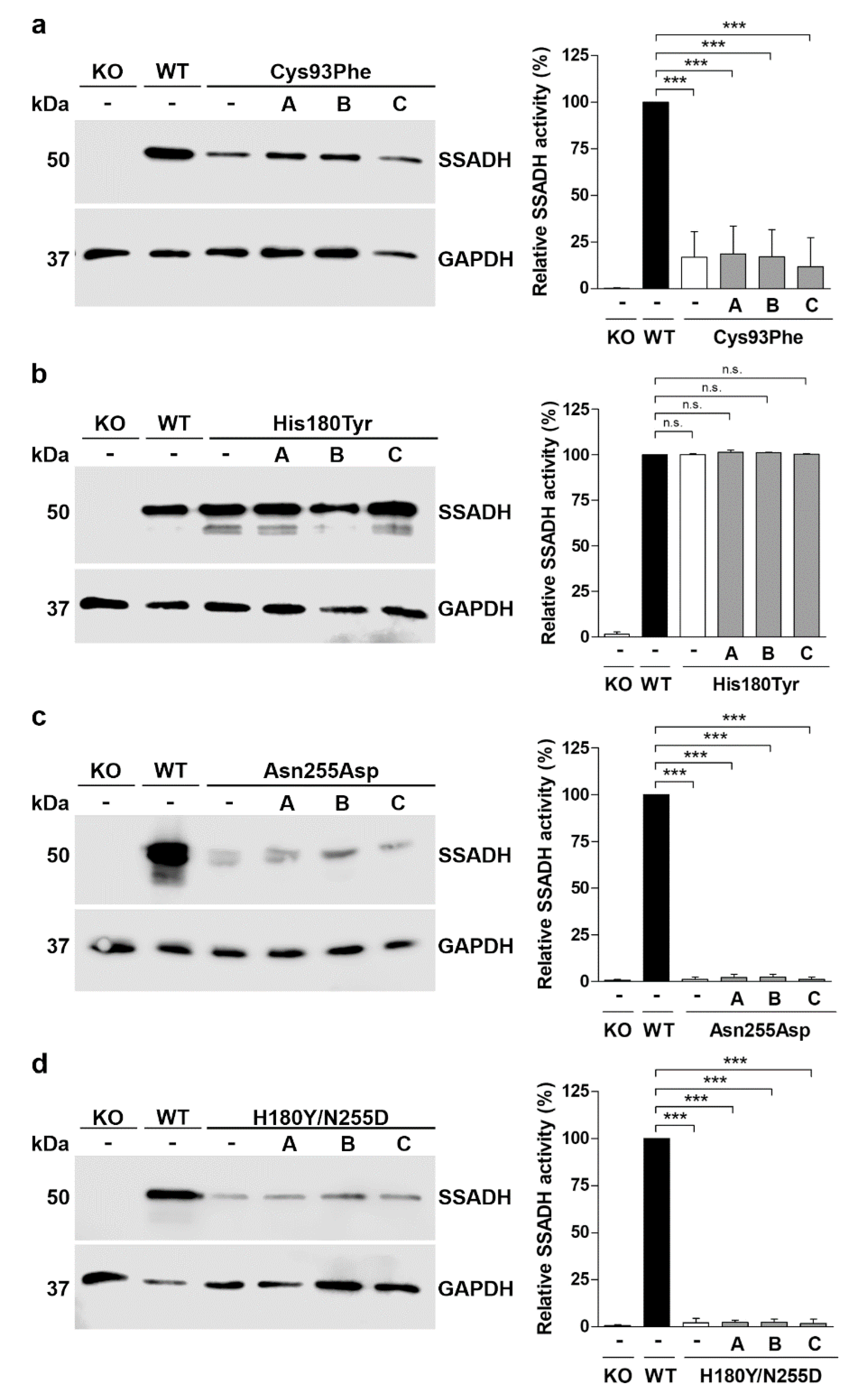

Figure 7.

Treatment of knock-in cells stably expressing the SSADH patient variants. (a-d) SSADH-deficient Flp-InTM-293 cells (KO) stably expressing one of the SSADH variants (Cys93Phe, His180Tyr, Asn255Asp or Asn255Asp/His180Tyr) were treated with 50 µM arimoclomol (A), 10 mM betaine (B), or 250 nM celastrol (C). After 24 h, cell lysates were prepared and subjected to Western blotting (left panels) and SSADH enzyme activity assay (right panels). GAPDH was used as a loading control for Western blots. Representative Western blots are shown (n = 3). SSADH activity of SSADH-KO Flp-InTM-293 cells stably expressing WT SSADH was set to 100%, and the variant activities are expressed as % WT. Data are expressed as mean values ± SD (n = 3). *** p ≤ 0.001 n.s. = non-significant (One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test).

Figure 7.

Treatment of knock-in cells stably expressing the SSADH patient variants. (a-d) SSADH-deficient Flp-InTM-293 cells (KO) stably expressing one of the SSADH variants (Cys93Phe, His180Tyr, Asn255Asp or Asn255Asp/His180Tyr) were treated with 50 µM arimoclomol (A), 10 mM betaine (B), or 250 nM celastrol (C). After 24 h, cell lysates were prepared and subjected to Western blotting (left panels) and SSADH enzyme activity assay (right panels). GAPDH was used as a loading control for Western blots. Representative Western blots are shown (n = 3). SSADH activity of SSADH-KO Flp-InTM-293 cells stably expressing WT SSADH was set to 100%, and the variant activities are expressed as % WT. Data are expressed as mean values ± SD (n = 3). *** p ≤ 0.001 n.s. = non-significant (One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test).

Figure 8.

Treatment of SSADH deficiency patient fibroblasts. Patient fibroblasts were treated either with 50 µM arimoclomol (A), 10 mM betaine (B), or 250 nM celastrol (C), and compared to untreated control fibroblasts (Co). After 24 h or 48 h, cell lysates were prepared and subjected to (a) Western blotting and (b) SSADH enzyme activity assay. GAPDH was used as a loading control in the Western blots. Representative Western blots are shown (n = 3). (b) SSADH activity of untreated control fibroblasts was set to 100%, and the relative SSADH activities in the patient cells were expressed as % WT. Data are expressed as mean values ± SD (n = 3). ** p ≤ 0.01; *** p ≤ 0.001 (One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test)..

Figure 8.

Treatment of SSADH deficiency patient fibroblasts. Patient fibroblasts were treated either with 50 µM arimoclomol (A), 10 mM betaine (B), or 250 nM celastrol (C), and compared to untreated control fibroblasts (Co). After 24 h or 48 h, cell lysates were prepared and subjected to (a) Western blotting and (b) SSADH enzyme activity assay. GAPDH was used as a loading control in the Western blots. Representative Western blots are shown (n = 3). (b) SSADH activity of untreated control fibroblasts was set to 100%, and the relative SSADH activities in the patient cells were expressed as % WT. Data are expressed as mean values ± SD (n = 3). ** p ≤ 0.01; *** p ≤ 0.001 (One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test)..

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide sequences used for PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis of eukaryotic expression vectors. All sequences are shown in 5´–3´ direction. F: forward, R: reverse.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide sequences used for PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis of eukaryotic expression vectors. All sequences are shown in 5´–3´ direction. F: forward, R: reverse.

| Substitution |

Sequence |

| Val90Ala |

F: CGCTCTGGGCATGGCAGCCGACTGCGGGG

R: CCCCGCAGTCGGCTGCCATGCCCAGAGCG |

| Cys93Phe |

F: GGGCATGGTAGCCGACTTCGGGGTGCG

R: CGCACCCCGAAGTCGGCTACCATGCCC |

| His180Tyr |

F: GTGTTTACGGAGACATTATCTACACCCCGGCAAAG

R: CTTTGCCGGGGTGTAGATAATGTCTCCGTAAACAC |

| Asn255Asp |

F: GATTCCTTCAGGTGTATACGATGTTATTCCCTGTTCTCG

R: CGAGAACAGGGAATAACATCGTATACACCTGAAGGAATC |

Table 2.

Oligonucleotide sequences used for PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis of prokaryotic expression vectors. All sequences are shown in 5´–3´ direction. F: forward, R: reverse.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotide sequences used for PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis of prokaryotic expression vectors. All sequences are shown in 5´–3´ direction. F: forward, R: reverse.

| Substitution |

Sequence |

| Val90Ala |

F: GCTGGGCATGGCTGCGGATTGCGGTG

R: CACCGCAATCCGCAGCCATGCCCAGC |

| Cys93Phe |

F: GCATGGTTGCGGATTTCGGTGTTCGTGAAGC

R: GCTTCACGAACACCGAAATCCGCAACCATGC |

| His180Tyr |

F: GTTTATGGTGACATCATTTACACCCCGGCGAAGG

R: CCTTCGCCGGGGTGTAAATGATGTCACCATAAAC |

| Asn255Asp |

F: GCGGCGTTTACGACGTGATTCCGTGCAG

R: CTGCACGGAATCACGTCGTAAACGCCGC |