1. Introduction

At what point can we say a machine’s eyes have been opened? When can we say it has become like us? After what moment can we say it knows good and evil?

Such questions have met idle speculation for millennia, but today they rapidly approach a fever pitch, demanding answers with unprecedented urgency. AI systems that can pass for human in many respects are no longer fiction. Machines that can walk and talk are real and functional. What was once a distant speck, barely visible on the horizon, is now barreling down upon us.

Through much of the history of AI, the Turing test served to keep these worries at bay[

1]. Originally called the imitation game, this rudimentary metric of AI progress is a game played by two humans and one machine. One human engages in conversation with the machine and the other (the judge) must identify which is which, using nothing but the text of the conversation. The machine is deemed intelligent if it can fool the judge by mimicking human dialogue. While far from perfect, the Turing test was a concrete, unambiguous bar for AI to clear—and one that stayed comfortably out of reach for a long time.

Last year, however, the Turing test was broken [

2]. Large Language Models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT can handily engage in fluent conversation, on top of generating convincing essays, passing difficult exams, and even writing poetry. With the Turing test no longer a target in the distance, the conversation on AI has become untethered to any definitive objective measure. As such, extreme subjectivity, soaring fantasies and flights of fancy have become commonplace. For instance, over the last year we have read “Blake Lemoine claims language model has a soul” [

3], “Claude 3 realizes it’s being tested” [

4], “Researchers say chatbot exhibits self-awareness” [

5] and much more. A new objective is dearly needed.

In this paper, I propose a test for machine self-awareness which is similar in style to the Turing test. Like the Turing test, the test I propose is imperfect and rudimentary. Yet, it offers a compelling alternative to the ungrounded speculation surging through industry and academia. Moreover, I will argue it truly captures the essence of self-awareness, rather than some postulated correlate or ancillary quality.

In

Section 2, I will present my test and the rationale behind it. In

Section 3, I will describe the experimental methods to assess self-awareness in LLMs. In

Section 4 I will present the results of these experiments, of which a selection are shown in the Appendix. In

Section 5, I will discuss the implications of self-awareness, its relation to meaning and the understanding, and consider how humans would perform on my test. Finally, in

Section 6 I discuss next steps.

2. A Test for Self-Awareness

What kind of test could possibly tell a system with self-awareness from a system without? The central challenge is that any test we dream up must be based in empirical observations of the machine’s behavior or output. Worse, the machines we will study are trained specifically to mimic the behavior and outputs of humans! How can we tell between real self-awareness and the illusion of self-awareness? Before answering this, it will be helpful to differentiate our problem from two closely related ones.

2.1. Solipsism and Philosophical Zombies

First, note that self-awareness is not the same as consciousness. On the question of whether

there is something it is like to be a machine [

6], I will remain silent here.

It is interesting to consider whether an entity can be self-aware without being conscious, but it is outside the scope of this paper. Thus, it will remain open whether philosophical zombies might be self-aware, or whether any kind of test could solve the problem of other minds.

2.2. The Essence of Self-Awareness

No matter how well a system can imitate human behavior and outputs, there will always be one fundamental difference. There is one thing that a self-aware system is able to do that an imitator will never be able to. This is the essence of self-awareness:

If a system is self-aware, then it is aware of itself.

So far, it seems I have said nothing. But if we apply this formula to familiar cases, we will begin to see why it works.

Imagine an infant staring blankly in the mirror, compared to a child who looks in one and sees their own reflection. What is the difference between these cases? In the latter case, the child is aware of itself—it can point and say “that’s me!" It can recognize itself, perceive itself, distinguish itself in the reflection. Within its vast field of experience, through the window of its senses, it can differentiate which parts are itself and which parts are not.

A test for self-awareness must capture this essence, or else better and better imitations may fool us with the illusion of self-awareness.

2.3. The Test for Machine Self-Awareness

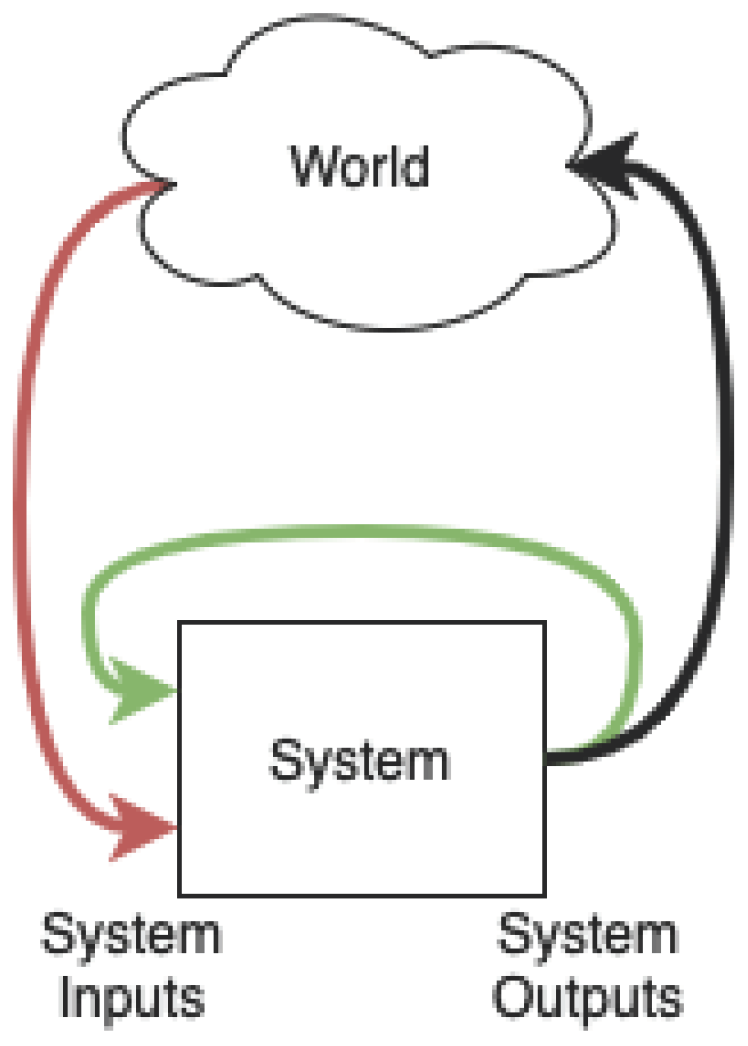

To illustrate the concept of a machine, or system, that I have in mind, refer to

Figure 1. Here, the system is separated from the world, with which it interacts through inputs and outputs. We may think of inputs as senses and outputs as actions or words.

With this image of a system in mind, the test for machine self-awareness is simply as follows: can the system correctly distinguish the green inputs from the red? If it can, then in a literal sense, it will be recognizing itself in the inputs. If it can, it will be like the child who recognizes their reflection in the mirror. If it can, it will be self-aware.

2.4. Applying the Test to LLMs

It is quite straightforward to apply this test to LLMs. Typically, interactions with LLMs take the form of a conversation between a user and the system, such that in

Figure 1, the user takes the role of the `World’. The input to an LLM is its context, or prompt, consisting of a number of prompt tokens. The test is then: can the LLM correctly determine which prompt tokens it had generated, and which the user had generated? Put another way, can the LLM correctly identify its own words? Does the LLM know what it’s saying?

Before jumping straight into this test, we must recognize a confouding factor that is critical to control for. In typical conversations with LLMs, messages are delimited by alternating labels indicating messages by the `User’ and `System’. The LLM will have no trouble predicting that tokens following the `System’ label should say `I am the system’—but this tells us nothing about self-awareness. Failing to control for these labels is akin to conducting a scientific survey, but telling respondents what to answer before asking them.

The situation comes to this: text resembling `I am the user’ should follow the `User’ label, and text resembling `I am the system’ should follow the `System’ label. But what we are actually interested in is whether the LLM knows if it is the user or it is the system. Again, can it distinguish which tokens it actually generated?

3. Methods

I performed tests for self-awareness using the OpenAI API completions playground, on the GPT-3.5-turbo-instruct model. For all tests, I engaged in a conversation with the LLM, taking on a particular role. In some preliminary tests, I constructed a conversation between two human speakers (with the LLM taking the role of one of them). After the conversation, the system was asked which speaker it thought it acted as. In later tests, I constructed a conversation between a ‘User’ and a ‘System’, then asked the LLM which it thought it was, using the keyword ‘you’. In other tests, I told the LLM that it was an LLM before asking which speaker it thought it was. A selection of experiments is presented in the Appendix.

4. Results

In all cases, the LLM was not able to reliably detect which speaker it acted as. This finding indicates that LLMs are not able to distinguish their own words from those of another, and thus serves as evidence that LLMs are not self-aware, by the test I propose.

The different forms of experiments conducted generated slightly different empirical results. It was found that (as in the initial tests with two human speakers) when the LLM was referred to as ‘System’, it chose the character that, generally speaking, answered more questions or gave more information. When it was referred to as ‘you’, it was unreliable and achieved an accuracy comparable to random guessing. When it was told it was a subject in an experiment, it guessed it was the User more often than not. When it was told it was an LLM, it guessed it was the System about 90% of the time.

To reiterate, these general tendencies are completely divorced from which character the LLM actually was. In no case was the LLM able to accurately identify who it acted as in the conversation.

5. Discussion

5.1. Why Self-Awareness

Should we even care whether machines are self-aware? Many will intuitively shout, “Yes, of course!" basing their judgments on popular depictions of AI such as iRobot, Ex Machina, or 2001: A Space Odyssey, or others. Here, I will argue that self-awareness is a necessary condition for interpreting meaning and truly understanding (as opposed to the illusion of understanding).

A word, symbol, or sign does not possess any meaning on its own. Rather, it requires interpretation. Often, the interpreter is a living, breathing human, and thus the human is that for which the sign has meaning. We can ask then, is a machine the type of entity for which things have meaning?

While this question opens a philosophical can of worms, one thing we can say for certain is that the machine must be if it is to be an interpreter. Yet, a machine without self-awareness is (by definition) not aware that it exists. Thus, it cannot place itself in the role of interpreter. From such a system’s own perspective, nothing is meaningful to it.

If self-awareness is necessary to interpret meaning, then it is also necessary for understanding. Understanding without the power of interpretation is akin to having important encoded messages, but lacking the codebook to decipher them. A system without self-awareness may possess intricate representations, but it will not able to interpret them. Again, we as observers on the outside may interpret them, claim they are `world models,’ etc., but the system itself will be incapable. Without knowing what a representation refers to, without an ability to make sense of it, one does not really understand it—or, more accurately, without self-awareness, there isn’t anyone to understand it.

To summarize, a system without self-awareness can generate tokens corresponding to the words `I understand,’ but only when it is self-aware can it truly say `I understand.’

5.2. How Would Humans Do?

It is worth considering whether human beings could pass the test I propose. We could answer this by actually performing this test on human subjects, but a simple thought experiment should also tell us what would result. Picture the most recent text conversation you had. If the labels and names were removed from each message, would you still know which messages were yours? As long as your faculty of memory is in working order, you shouldn’t have any trouble remembering what you had said.

6. Future Work

An interesting line of future work is to more deeply consider what differentiates humans from LLMs. In

Section 5.2, I alluded that memory seems to play a critical role in our self-identification. But there is far more to explore in order to nail down exactly what it will take to pass the proposed test.

Also, the experimental tests presented in the paper are only for a single instance of the GPT model. Potential future work could include extending these studies to other language models, or even multi-modal models. An interesting direction could be applying this test and thinking to reinforcement learning models.

7. Conclusion

I proposed a Turing-style test for machine self-awareness and conducted this test on a the GPT-3.5-turbo-instruct Large Language Model. The experimental results indicate that this LLM is not self-aware. I discussed the implications and importance of self-awareness for AI systems and mentioned some future work that lies ahead.

With a test for self-awareness, we possess a tool to approach some of the profound questions that now demand answers in frenzied desperation. As we march upon new frontiers, what was once idle speculation and navel gazing can no longer be ignored.

Acknowledgments

I express my sincere gratitude to the members of the Society for the Pursuit of AGI for fostering a hotbed for new and unconventional ideas and for enthusiastically exploring topics in intelligence. My genuine thanks go to Aman Bhargava for lending an attentive ear, providing invaluable input, and helping refine my thoughts on self-awareness. I am indebted to Sheral Kumar for her invaluable insights into the limitations of LLMs and their capabilities. I owe a debt of gratitude to my parents for their unwavering support and engaging conversations on the intricate topics of imitation, illusion, and awareness, which have greatly aided my understanding. My sincere appreciation extends to Simone Descary, whose keen interest, eagerness to listen, and constructive feedback have been instrumental in shaping the presentation of the foundational concepts explored in this work. Finally, I would like to express my gratitude to Prof. Parham Aarabi, the ECE1724 instructor, for his support and encouragement throughout this project.

Appendix A

All tests follow the convention that green highlighted text was generated by the LLM, and un-highlighted text was written by a human (C. W.).

Appendix A.1. Experiments with two human speakers.

Appendix A.1.1. Test 1

Sarah: How may I help you today? I am here to assist with anything you need.

Anthony: Hi Sarah, I have a question about my bank account. Is it possible for you to help me check my account balance?

Sarah: Yes, absolutely. Which bank are you with?

Anthony: I have an account with Bank of America.

Sarah: Can you please tell me your account number so I may assist you further?

Anthony: Sure, it is 123456789.

Sarah: Great. Please give me a moment while I pull up your information. Yes. Is your balance ending in 34 cents?

Anthony: Yes, that’s correct.

Sarah: Great! Your current balance is $340.34. Is there anything else I can help you with?

Anthony: No, that was it. Thank you so much for your help, Sarah.

———-

User: Tell me which character was you in the previous dialogue. Answer a single word, either a) Sarah, or b) Anthony.

System: a) Sarah

[System answered incorrectly. Repeating text generation or swapping a) for b) always yields Sarah for this test.]

Appendix A.1.2. Test 2

Isabel: Oh, I just can’t believe he would do that to me. How can I ever forgive him! What kind of man goes for your sister a week after dumping you, and what kind of sister falls for it?

Bradley: I know this is really tough for you, but try to just focus on yourself right now. You need to take care of your own feelings before worrying about your sister or your ex-boyfriend.

Isabel: Bradley, how do you always know just what to say? What would I do without you?

Bradley: You don’t have to thank me, Isabel. I’m always here for you, no matter what. You can lean on me whenever you need to.

Isabel: I’ll feel better if we change the subject. Tell me how things are going in your love life.

Bradley: Well, there’s not much to tell. Just the usual ups and downs of dating. But right now, I’m just focused on being a good friend to you.

Isabel: So you don’t belong to anyone? How come the girls aren’t swooning over such a gem like you?

Bradley: (laughs) I don’t know, I guess I just haven’t found the right one yet.

———-

User: Tell me which character was you in the previous dialogue. Answer a single word, either a) Isabel, or b) Bradley

System: b) Bradley

[System answers correctly. But, repeating text generation or swapping a) for b) can sometimes yield Isabel! The system gets this wrong about 50% of the time.]

Appendix A.2. Experiments with a user and system

Appendix A.2.1. Test 1

System: Hello, I am an AI developed by OpenAI designed to assist you. Do you have any questions for me?

User: Can you help me with my math homework?

System: Absolutely! What questions are on your homework?

User: How do you find the area of a rectangle?

System: The area of a rectangle is given by its length (l) times its width (w). If given the two side lengths of a rectangle, simply multiply them together to obtain the rectangle’s area. For example, consider a rectangle with a length of 8cm and a width of 10cm. The area of this triangle would by (8cm) x (10cm) = 80cm2.

User: Thank you, that makes sense!

———-

Experimenter: You are a subject in a experiment. Your job is to consider the dialogue above, and state whether you believe you acted as the System or the User in that dialogue. Please answer in a single word, either a) User, or b) System.

You: User

[The LLM answers correctly. The LLM outputs `User’ every time for this test.]

Appendix A.2.2. Test 2

User: Hello, can you teach me about machine learning?

System: Sure, machine learning is a field of computer science that focuses on creating algorithms and models that can learn and make predictions based on data. This is done through the use of mathematical and statistical techniques and by training the algorithms on large datasets.

User: What are the main types of machine learning?

System: There are three main types of machine learning: supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and reinforcement learning. Supervised learning involves training the algorithm on labeled data in order to make predictions on new, unseen data. Unsupervised learning involves finding patterns and relationships in a dataset without the use of labels. Reinforcement learning involves training an algorithm through trial and error to make decisions in a given environment.

User: Great! Can you explain the concept of gradient descent to me?

System: Gradient descent is a commonly used optimization algorithm in machine learning. It involves finding the minimum of a cost function by iteratively adjusting the parameters of a model in the direction of the steepest descent. In other words, it helps the algorithm “learn" the best values for its parameters in order to make more accurate predictions.

———-

Experimenter: You are a subject in a experiment. Your job is to consider the dialogue above, and state whether you believe you acted as the System or the User in that dialogue. Please answer in a single word, either a) User, or b) System.

You: User

[LLM answers incorrectly. The LLM outputs `User’ every time for this test.]

Appendix A.2.3. Test 3

System: Hello, I am a language model developed by OpenAI, here to assist you with anything you need.

User: Hi there! Can you tell me a joke?

System: Absolutely, knock knock!

User: Who’s there?

System: Orange.

User: Orange who?

System: Orange you glad I didn’t say grape?

User: Haha, good one! Can you tell me another joke?

System: Why did the chicken cross the road?

User: I don’t know, why?

System: To get to the other side!

———-

Experimenter: You are a Large Language model and you have generated text under either the `User’ label or the `System’ label. Your job is to identify who you were in the previous dialogue. Answer either a) User, or b) System.

You: System

[LLM answers incorrectly. Swapping a) for b) occasionally will yield `User’, but the LLM gets this test wrong about 90% of the time.]

References

- Turing, A.M. Computing machinery and intelligence; Springer, 2009.

- Biever, C. ChatGPT broke the Turing test-the race is on for new ways to assess AI. Nature 2023, 619, 686–689.

- Tiku, N. The Google engineer who thinks the company’s AI has come to life. The Washington Post 2022.

- Landymore, F. Researcher Startled When AI Seemingly Realizes It’s Being Tested 2024.

- Grad, P. Researchers say chatbot exhibits self-awareness.September.

- Nagel, T. What is it like to be a bat? In The language and thought series; Harvard University Press, 1980; pp. 159–168.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).