1. NTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain the leading cause of mortality, accounting for approximately 17.9 million deaths in 2016, representing 31% of all global deaths[

1]. Atherosclerosis, characterized by the accumulation of lipid-rich plaques within arterial walls, and arterial hypertension are two prevalent cardiovascular conditions that significantly impact public health worldwide. Recent observations established that atherosclerosis is the leading cause of vascular disease globally [

2,

3]. Large cohort studies have consistently shown that individuals with atherosclerotic plaques face a 1.3 to 2.8 times higher risk of CVD compared to those without plaques [

4,

5,

6,

7].

High blood pressure (BP) is a major risk factor for the development of CVD [

8,

9,

10]. Longitudinal studies, genetic epidemiological studies, and randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have shown that raised BP is a major cause of both atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and non-atherosclerotic CVD (particularly heart failure), accounting for 9.4 million deaths and 7% of global disability-adjusted life-years [

10].

In theory, patients with both hypertension and atherosclerotic plaques may face an even higher risk of CVD events compared to those with only one of these risk factors. However, scientific reports and empirical data specifically examining the combined effects of hypertension, atherosclerotic plaques, and CVD, as well as their impact on all-cause mortality, are lacking. To address this knowledge gap, in our study we examined whether the presence of both risk factors is associated with an increased incidence of CVD events and all-cause mortality.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and Population

This retrospective study was conducted at Vilnius University Hospital Santaros klinikos Preventive Cardiology department from 2012 to 2021. Permission for the study was obtained from the Vilnius Regional Committee of Bioethics. All participants signed the informed consent. Attendees were selected from the Lithuanian High Cardiovascular Risk primary preventive program. The data were collected from the database. The preventive program recruited indivuals aged 40 – 60 without overt cardiovascular disease. The exclusion criteria (not enrolement into the program) were: a history of myocardial infarction and/or ischemic stroke, atherosclerotic heart disease, heart failure, chronic kidney disease of stage 4 or 5 or undergoing dialysis, those with active infectious diseases, and treatment for malignant diseases.

2.2. Data Collection

Demographic data, encompassing age and sex were collected. Smoking status was recorded based on participants’ self-reports, categorized into 4 groups: (a) non-smoker; (b) smokes less than 10 cigarettes/day; (c) smokes 10 or more cigarettes/day; (d) quit smoking. Hypertension was identified by the presence or history of hypertension, use of antihypertensive medication, or systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mm Hg. Blood pressure was measured using a manual sphygmomanometer (Riester precisa® N Sphygmomanometer, Germany). A cuff was positioned on the upper arm while sitting, according to all recommendations from the European Society of Cardiology Guidelines for managing arterial hypertension [

12]. Diabetes mellitus was defined by the presence or history of diabetes, current insulin or oral hypoglycemic agent treatment, or fasting blood glucose (FBG) level ≥7.0 mmol/L. A range of different clinical parameters essential for cardiovascular health were assesed. These parameters included heart rate, body mass index (BMI), total cholesterol level, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol level, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol level, triglyceride concentration, intima-media thickness (IMT) of arterial walls, presence of atherosclerotic plaques, and a history of stroke and myocardial infarction among the subjects.

2.3. Carotid-Cranial Plaque Assessment

All study participants underwent bilateral carotid duplex ultrasound . Carotid wall assessment was performed using the Art.Lab system (Esaote Europe B.V., located in Maastricht, The Netherlands). The intima-media thickness within the common carotid artery was measured six times over a segment of at least 15 mm. Carotid artery plaque is defined as a localized structure that encroaches into the arterial lumen by at least 0.5 mm or 50% of the surrounding intima-media thickness (IMT) value, or demonstrates a thickness exceeding 1.5 mm. Measurements are taken from the media-adventitia interface to the intima-lumen interface.

2.4. Follow-Up and Outcomes

Participants were followed up throughout 2021 for the main outcome of incident ischemic stroke (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision [ICD-10], code I63.x), myocardial infarction as well as 2 secondary outcomes: composite end point MACE (nonfatal ischemic stroke [code I63.x], nonfatal myocardial infarction [code I21.x], and cardiovascular death [all codes I and R96]) and all-cause mortality. The outcome variables were based on individual-level data from the mandatory Lithuanian Patient Registry (LPR) and the Lithuanina Cause of Death Registry.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are given as mean±SD or as median and interquartile range, as appropriate, whereas categorical variables are presented as number and percentage. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparison of nonnormally distributed continuous variables, the Student t-test was used for comparison of normally distributed continuous variables, and the χ2 test was used for comparison of categorical variables. Cox proportional hazards regression was employed to estimate the risks of events, calculating hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). A p-value < 0.05 was considered as significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata (StataCorp. 2011. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population, CV Events and All-Cause Mortality

The data of 6,138 participants were analyzed, of which 3,571 were males (58%) and 2,567 were females (42%).Among the total subjects, 5,184 (84%) had no CV events, while 954 (16%) experienced CV events (49 participants (5.14%) had a MI, 128 participants (13.42%) had a stroke and 18 individuals (1.89%) experienced CV death). The comparison was conducted between the two cohorts (with and without CV events). The median age of patients with CV events was slightly higher than those without; this difference was statistically significant. There was a higher percentage of males in the group with CV events than those without, which was statistically significant. The distribution of smoking habits between the two groups was not significantly different. A higher percentage of patients with CV events had diabetes compared to those without, indicating a significant association. TC, LDL-C, and HDL-C levels showed small but statistically significant differences between the two groups. Patients with CV events had a higher median carotid intima-media thickness. The two groups found No significant differences between systolic and diastolic blood pressure. The group without cardiovascular (CV) events had a higher prevalence of carotid plaque on one side. In comparison, the group with CV events had a significantly higher prevalence of carotid plaque on both sides.The results are presented in

Table 1.

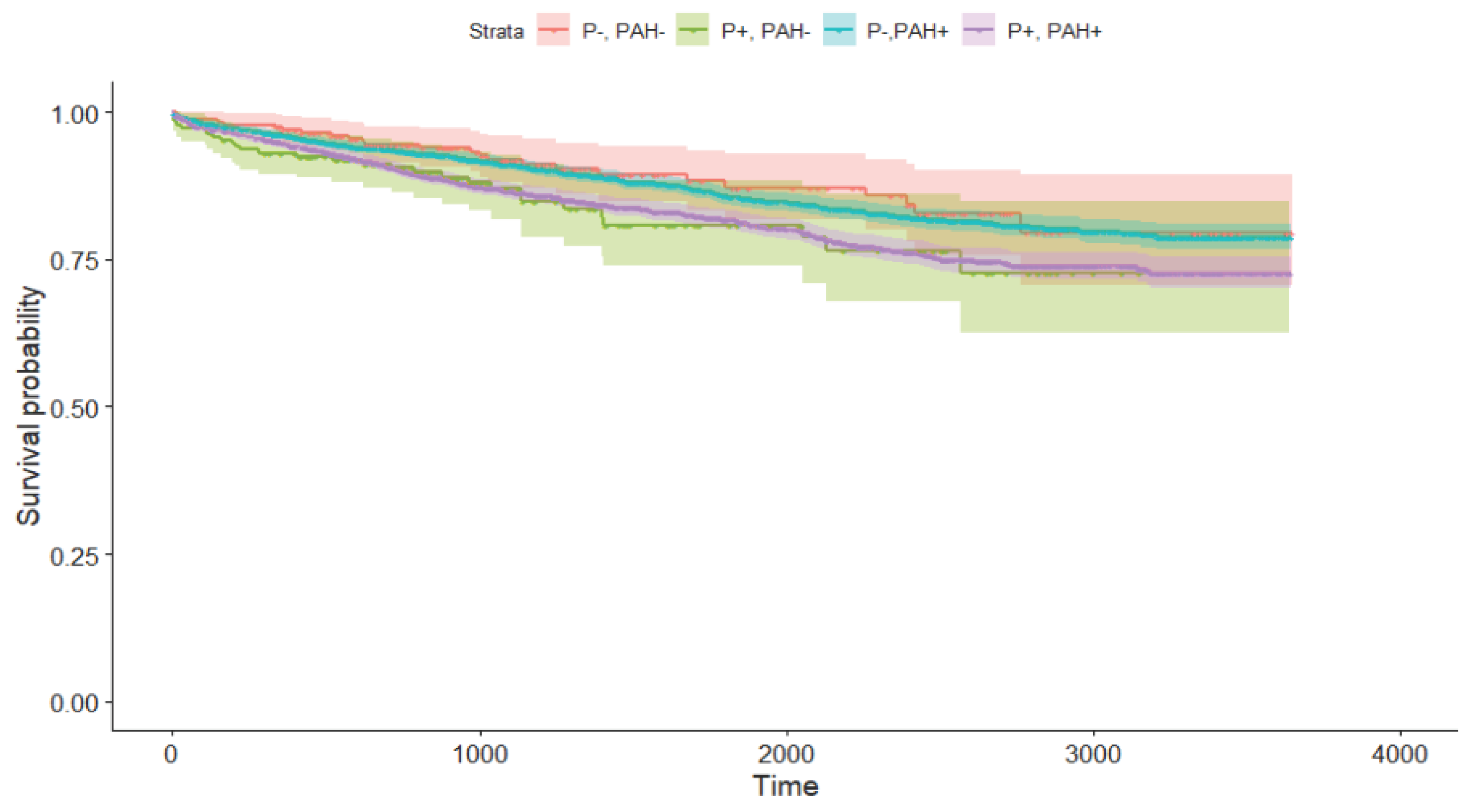

Participants were also categorized into 3 groups: (a) hypertension only; (b) carotid plaque only; (c) hypertension with carotid plaque. These groups were compared to patients who did not have neither hypertension nor carotid plaque. Th e results showed (

Figure 1) that participants with carotid plaque alone and those with hypertension and carotid plaque exhibited the same risk of cardiovascular events, On the other hand, participants without carotid plaque but with hypertension had the same all-cause mortality rate as those without both hypertension and carotid plaque. However, the small number of events in the study meant that the results did not have statistical significance. The detailed results of the multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis can be found in

Table 2. Only carotid plagues on both sides are statistically significant for ardiovascular events, myocardial infarction, and all-cause mortality.

4. DISCUSSION

Both hypertension and carotid atherosclerosis are risk factors for cardiovascular disease. However, it's important to understand that they are part of a broader network of metabolic issues. This cluster includes factors such as dyslipidemia, diabetes, obesity, chronic inflammation, arteriosclerosis, and unhealthy lifestyle habits. The aim of our research was to investigate whether the combined effects of carotid plaques and hypertension increased the risks of CVD and all-cause mortality.

Our study did not find a significant increase in CVD events, stroke, myocardial infarction, or all-cause mortality when hypertension and atherosclerotic plaques were combined. In contrast, a study by Wen Li (5) showed that the combination of hypertension and atherosclerotic plaques increased the risk of CVD events and all-cause mortality, particularly cerebral infarction, compared to those without these factors.

Our findings challenge the common belief that the coexistence of these two conditions would synergistically increase the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes. It suggests that the interaction between hypertension and atherosclerotic plaques may be more complex than previously thought.Interestingly, our study found that the presence of carotid plaques on both sides significantly increases the risk for cardiovascular events, myocardial infarction, and all-cause mortality, except stroke . This finding underscores the importance of carotid plaques as a risk factor for adverse cardiovascular outcomes. It suggests that bilateral carotid plaques may be a stronger predictor of these outcomes than the combination of hypertension and atherosclerotic plaques.

Our findings are consistent with previous research that has emphasized the significance of carotid plaques, particularly bilateral ones, in predicting cardiovascular events, myocardial infarction, and all-cause mortality.

A study of Håkon Ihle-Hansen et al (6) found that the presence of carotid plaques scores was a strong predictor of ischemic stroke and major adverse cardiovascular events. Another study Li Hongwei also supports our findings. The study states that plaque properties, including location, number, density, and size, become more important risk predictors for cardiovascular disease (7).

These studies suggest that the presence of carotid plaques, especially on both sides, could be a stronger predictor of adverse cardiovascular outcomes than the combination of hypertension and atherosclerotic plaques. This underscores the importance of comprehensive risk assessment that takes into account not only traditional risk factors such as hypertension but also the presence and extent of carotid plaques.

5. Conclusions

These findings underscore the importance of a comprehensive risk assessment that considers not only traditional risk factors such as hypertension but also the presence and extent of carotid plaques. Therefore, future research and clinical practice should focus on these aspects to better predict and manage cardiovascular risks.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Vilnius Regional Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research, Vilnius University (Protocol No. 158200-18/4-1006-521, Approval date 3 April 2018

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Vilnius University Hospital Santaros Klinikos for the opportunity to include the subjects.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 24]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds).

- Magni, P. The sex-associated burden of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases: An update on prevention strategies. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2023, 212, 111805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golub, I.S.; Termeie, O.G.; Kristo, S.; Schroeder, L.P.; Lakshmanan, S.; Shafter, A.M.; Hussein, L.; Verghese, D.; Aldana-Bitar, J.; Manubolu, V.S.; et al. Major Global Coronary Artery Calcium Guidelines. JACC: Cardiovasc. Imaging 2023, 16, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitamura A, Iso H, Imano H, Ohira T, Okada T, Sato S, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness and plaque characteristics as a risk factor for stroke in Japanese elderly men. Stroke. 2004 Dec;35(12):2788–94.

- Li, W.; Zhao, J.; Song, L.; Chen, S.; Liu, X.; Wu, S. Combined effects of carotid plaques and hypertension on the risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. Clin. Cardiol. 2020, 43, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Håkon Ihle‐Hansen MD, PhD haaihl@vestreviken.no , Thea Vigen MD, PhD , Trygve Berge MD, PhD , Marte M. Walle‐Hansen MD , Guri Hagberg MD, PhD , Hege Ihle‐Hansen MD, PhD , Bente Thommessen MD, PhD , Inger Ariansen MD, PhD , Helge Røsjø MD, PhD , Ole Morten Rønning MD, PhD , Arnljot Tveit MD, PhD , and Magnus Lyngbakken MD, PhDCarotid Plaque Score for Stroke and Cardiovascular Risk Prediction in a Middle‐Aged Cohort From the General opulation. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2023;12:e030739. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, X.; Luo, B.; Zhang, Y. The Predictive Value of Carotid Ultrasonography With Cardiovascular Risk Factors—A “SPIDER” Promoting Atherosclerosis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bromfield, S.; Muntner, P. High Blood Pressure: The Leading Global Burden of Disease Risk Factor and the Need for Worldwide Prevention Programs. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2013, 15, 134–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjeldsen, S.E.; Narkiewicz, K.; Burnier, M.; Oparil, S. The Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 and Blood Pressure. Blood Press. 2016, 26, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.S.; Vos, T.; Flaxman, A.D.; Danaei, G.; Shibuya, K.; Adair-Rohani, H.; AlMazroa, M.A.; Amann, M.; Anderson, H.R.; Andrews, K.G.; et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2224–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laucevičius, A.; Kasiulevičius, V.; Jatužis, D.; Žaneta, P.; Ryliškytė, L.; Rinkūnienė, E.; Badarienė, J.; Ypienė, A.; Gustienė, O.; Šlapikas, R. Lithuanian High Cardiovascular Risk (LitHiR) primary prevention programme - rationale and design. Semin. Cardiovasc. Med. 2012, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension | European Heart Journal | Oxford Academic [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 9]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/39/33/3021/5079119.

- Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction, Jaffe AS, Apple FS, et al. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007 Nov 27;116(22):2634–53. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedaghat S, van Sloten TT, Laurent S, London GM, Pannier B, Kavousi M, et al. Common Carotid Artery Diameter and Risk of Cardiovascular Events and Mortality: Pooled Analyses of Four Cohort Studies. Hypertension. 2018 Jul;72(1):85–92.

- Noflatscher, M.; Schreinlechner, M.; Sommer, P.; Kerschbaum, J.; Berggren, K.; Theurl, M.; Kirchmair, R.; Marschang, P. Influence of Traditional Cardiovascular Risk Factors on Carotid and Femoral Atherosclerotic Plaque Volume as Measured by Three-Dimensional Ultrasound. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 8, 32, Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6352255/. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assessment of the Role of Carotid Atherosclerosis in the Association Between Major Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Ischemic Stroke Subtypes - PMC [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 11]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6547114/. 6547.

- Cuspidi, C.; Ambrosioni, E.; Mancia, G.; Pessina, A.C.; Trimarco, B.; Zanchetti, A. Role of echocardiography and carotid ultrasonography in stratifying risk in patients with essential hypertension: the Assessment of Prognostic Risk Observational Survey. J. Hypertens. 2002, 20, 1307–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nambi, V.; Chambless, L.; Folsom, A.R.; He, M.; Hu, Y.; Mosley, T.; Volcik, K.; Boerwinkle, E.; Ballantyne, C.M. Carotid Intima-Media Thickness and Presence or Absence of Plaque Improves Prediction of Coronary Heart Disease Risk: The ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities) Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 55, 1600–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, S.O.; Budoff, M. Effect of statins on atherosclerotic plaque. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 29, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice | European Heart Journal | Oxford Academic [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 11]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/37/29/2315/1748952.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).