1. Introduction

Forensic science is an academic field that investigates legal (and illegal) matters using science, and subsequently applies research results to resolving real crime cases [

1].

Conventional approaches to the identification of individuals range from the use of anthropometry to fingerprint analysis, from age and sex determination to blood grouping and DNA analysis, and finally odontology [

2], a multidisciplinary field of study combining dental knowledge, forensic medicine and anthropology. It permits the identification of individuals by exploiting the characteristics of the oral cavity, which are unique to each person. This branch is crucial in victim identification processes or in crime contexts [

3].

Forensic odontology plays an essential role when other methods of recognition, such as fingerprints or facial recognition, are not feasible due to the body being compromised, such as in the case of charred or decomposed corpses. This is possible because many structures in the oral cavity, such as teeth and bones, are highly resistant [

4]. Several techniques can be used, such as the analysis of bite marks, ante-mortem dental records, rugoscopy and cheiloscopy.

Dental prints found at crime scenes have long been regarded as useful or crucial evidence for obtaining convictions. However, over the years, several critical issues have arisen concerning conclusions regarding the identification of bite injuries, which have led to defendants being unfairly convicted [

5].

In forensic odontology, palatine wrinkles represent an important identification marker, especially in edentulous individuals. It has been observed that the hard palate and its wrinkles constitutes an exceptionally stable structure over time, even in cases where there are charred or decaying skulls, and recent studies have shown that there is promising data regarding the identification of the sex of a subject, but this method is also limited by the absence of a database [

6].

Forensic odontologists also play a crucial role in collaborating with other experts to ascertain the sex of remains by examining dental and cranial characteristics. Teeth offer a wealth of information, with features like morphology, crown dimensions, and root length serving as key indicators for distinguishing between male and female sexes. Similarly, the skull presents distinct patterns and traits unique to each sex, further aiding in the accurate determination of sex in forensic investigations [

7].

Cheiloscopy (from the Greek: ‘keilos’= lip and ‘skopein’= to see) is the science that deals with the study of lip imprints by analyzing the grooves present at the vermilion level.

The anthropologist R. Fischer was the first to describe the presence of lip wrinkles in 1902, but without suggesting any practical use [

8]. In the early 1930s, Dr. Edmond Locard, a prominent French criminologist, began investigating the potential of lip prints as a means of identification. This represented a turning point in the understanding of the potential of this discipline. Locard recognized the uniqueness of lip prints and their importance in the field of investigation [

9].

Between 1968 and 1971, two Japanese scholars, Y. Tsuchihashi and T. Suzuki, determined that the arrangements of all the grooves on the red portion of the lips are unique in each individual [

10]. Tsuchihashi observed that even homozygotic twins have different lip prints, even though they possess an identical set of chromosomes [

10].

Tsuchihashi and Suzuki gave the name ‘Sulci Labiorum’ to the individual grooves and ‘Figura linearum labiorum rubrorum’ to the lip prints consisting of these grooves [

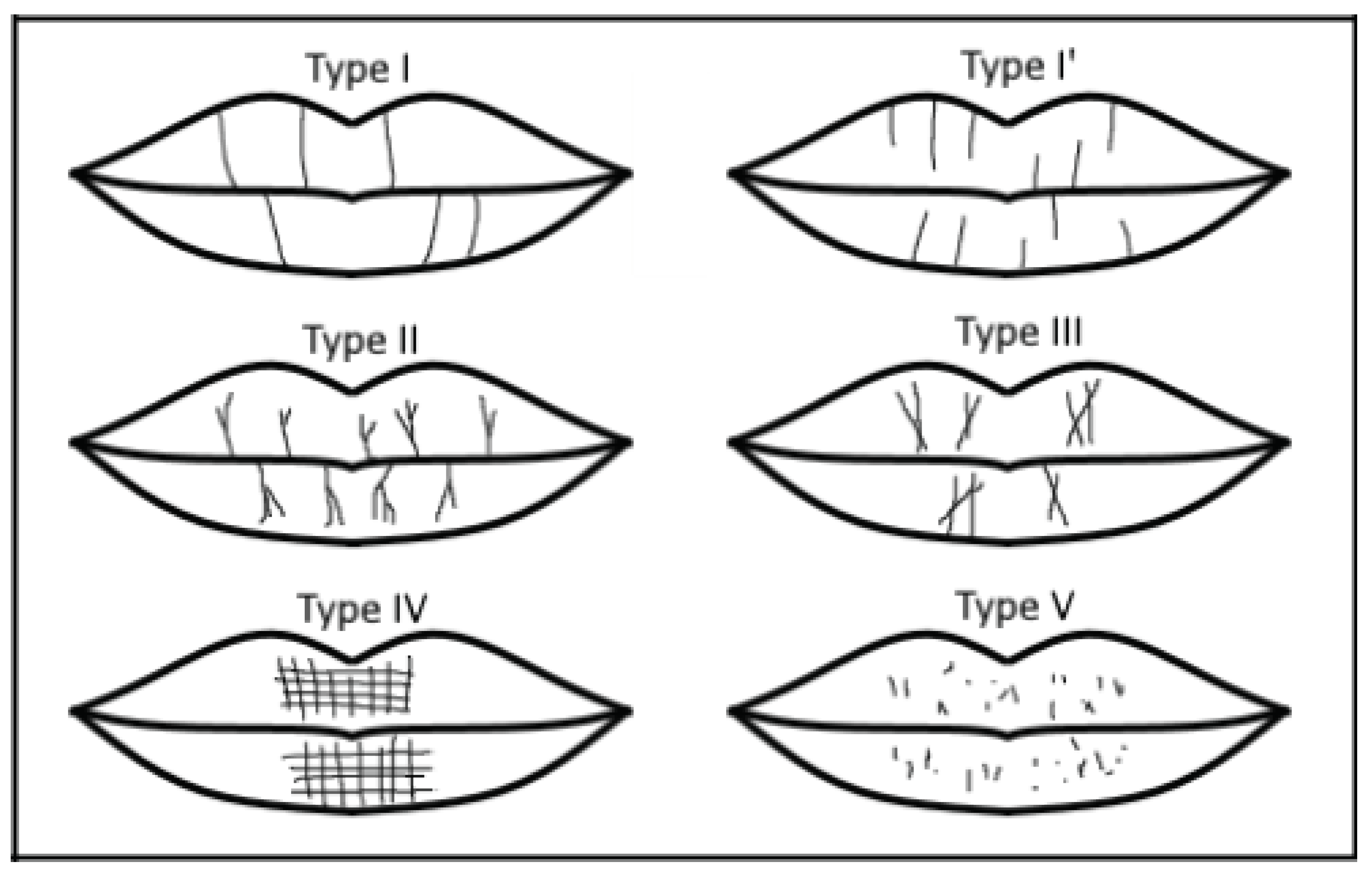

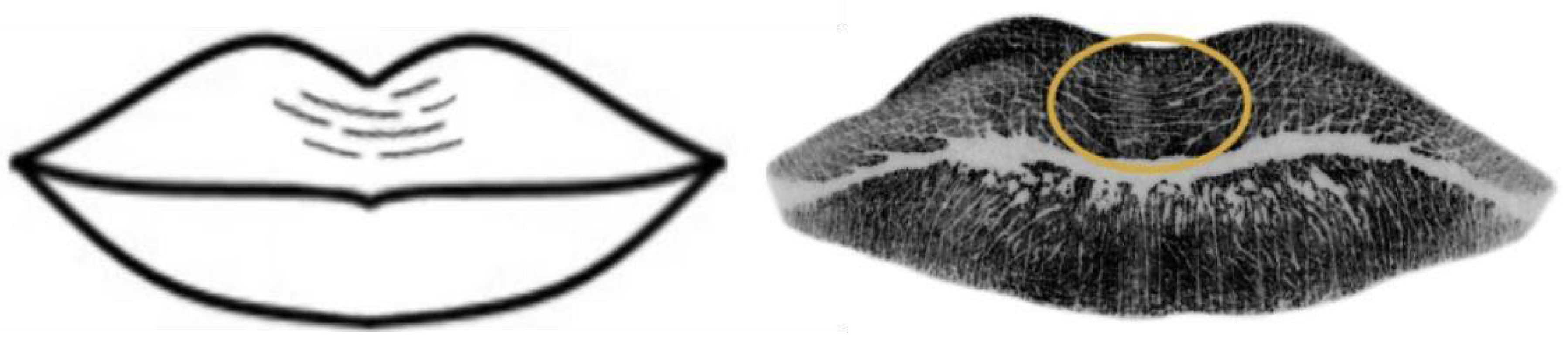

10]. Suzuki and Tsuchihashi also proposed a classification of labial wrinkles, dividing them into six different Types [

10] [

Figure 1]:

Lip prints have distinct characteristics, can be found as early as the sixth week of intrauterine life and do not undergo major changes during the course of one’s life [

11].

It has been observed that the characteristics of labial wrinkles essentially remain stable even in response to minor trauma, such as inflammation or pathological conditions such as herpes, and are not significantly influenced by environmental factors. However, changes in the shape and size of labial wrinkles can be observed following major trauma, such as scarring from surgery [

10].

Despite these changes, it is rare for the entire lip structure to be compromised, thus enabling the recognition of lip prints by matching them with lip areas not affected by the alterations due to the traumatic event.

On the other hand, some scarring may be an advantage in the identification process when it pre-exists the taking of lip prints. It adds a further level of uniqueness and specificity to the identification characteristics of the lips [

12].

Another observed fact is that there don’t seem to be any substantial alterations of lip wrinkles in the presence or absence of parafunctional oral habits such as smoking, vaping, playing a wind instrument or using an asthma inhaler [

13].

In addition, it would be interesting to evaluate the long-term effects of certain cosmetic procedures, such as the use of lip fillers with hyaluronic acid, which could have an impact on lip wrinkles, given that a total restitutio ad integrum of the lips after the treatment period has not been confirmed [

14]. Although no studies have yet been conducted regarding this interaction, it could be a promising area for future investigation as it could contribute to a more complete understanding of the variations in lip wrinkles and their determinants.

The aim of this experimental work is to assess the uniqueness of lip wrinkles, identify the presence of recurring patterns according to the Suzuki and Tsuchihashi classification and search for valid features to identify a subject’s sex.

2. Materials and Methods

This experimental study examined a total of 172 lip prints acquired under various circumstances at the University of Palermo.

Inclusion criteria:

Caucasian subjects.

Lips free of active lesions.

Absence of previous allergic reactions to lipstick.

Stable general health condition.

Indication of the gender of the subject.

Exclusion Criteria:

Non-Caucasian subjects.

Refusal of informed consent.

Presence of active injuries or recent surgery.

Presence of congenital malformations.

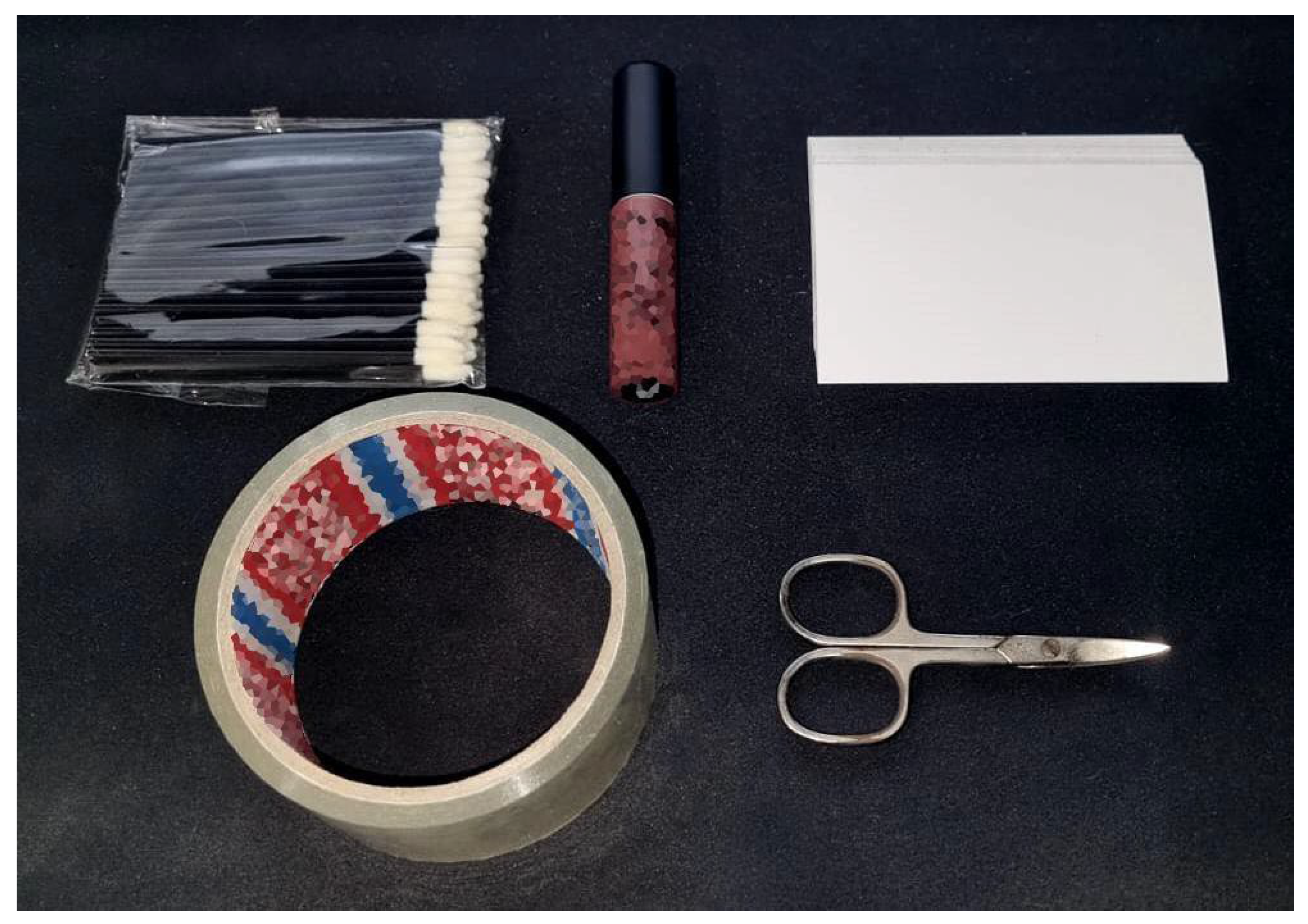

Following the acquisition of informed consent from the volunteers, a meticulous clinical examination of each subject’s lips was conducted to identify any recent lesions, active pathologies, or congenital malformations, all of which served as exclusion criteria for the study. Subsequently, the lips were thoroughly cleaned to ensure optimal conditions for the following steps. A thin layer of liquid lipstick was delicately applied to the lips using disposable brushes, and participants were instructed to rub their lips together to achieve an even distribution of the lipstick.

After allowing a brief interval of 30 seconds for the lipstick to partially dry, the upper and lower lip prints were captured simultaneously on strips of adhesive tape measuring 5x10cm. To minimize any potential alterations, the samples were left to dry completely before being transferred onto white cards for ease of storage and handling.

Pertinent information including the age and sex of each subject, the date of lip print acquisition, and a unique identification number were recorded on the back of each print, this was done to ensure objectivity and mitigate any potential bias during the identification of gender-related patterns.

The identification number was then linked to the respective patient’s data in a separate document to uphold privacy protocols.

To facilitate efficient analysis, all lip prints were measured and digitized, ensuring a practical and precise approach to data interpretation and comparison.

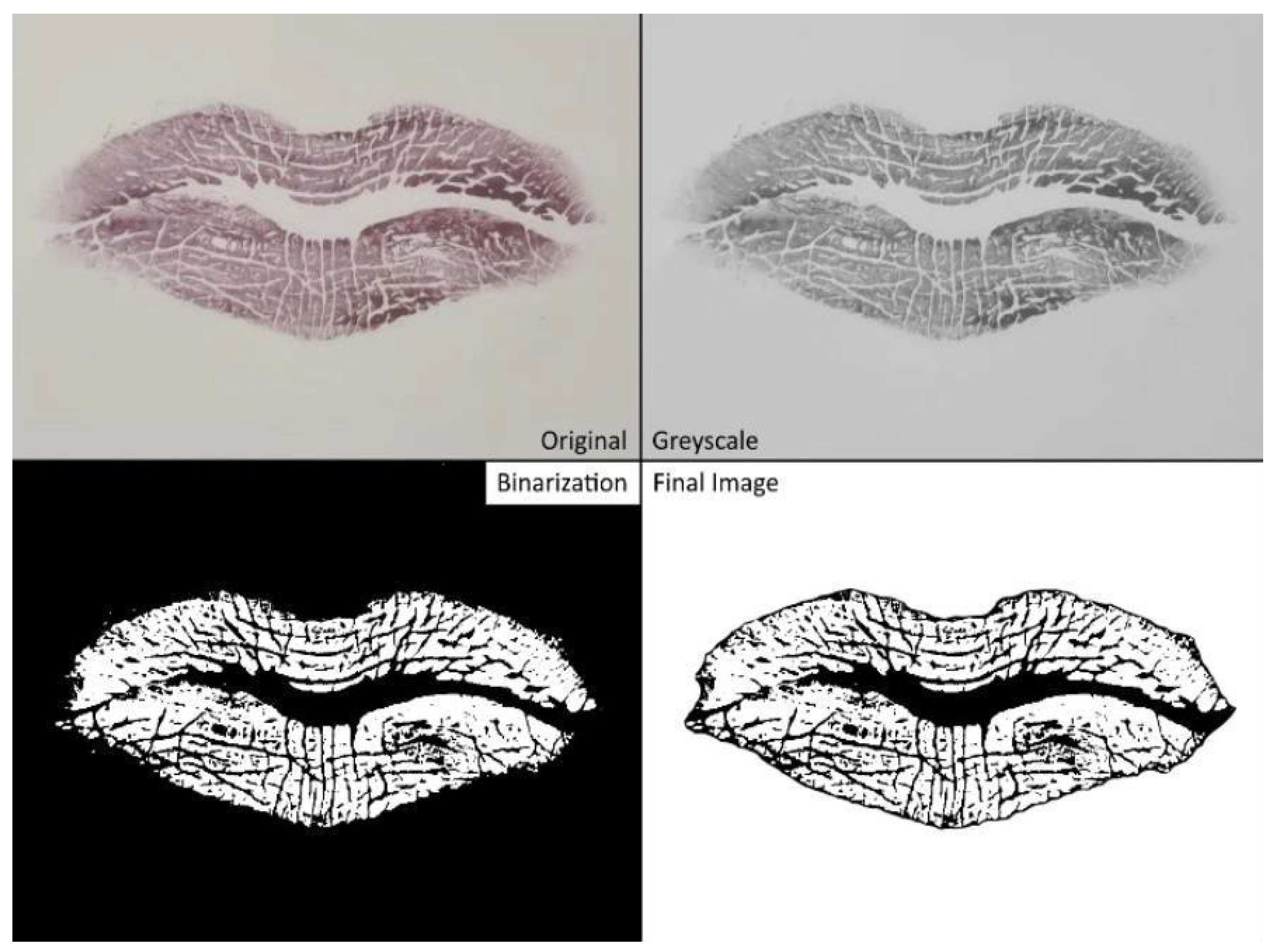

To better isolate and visualize the lip wrinkles, all digitized prints were edited using Adobe

® Photoshop image processing software [

Figure 3]:

Application of greyscale.

Binarization of the image.

Outlining the lip contour.

Manual tracing of labial wrinkles for each print.

Each print was first analyzed individually and then compared using superimposition to assess its uniqueness.

In this study, the lip prints were analyzed using a sextant-based approach. Each lip print was divided into sextants, and these segments were systematically evaluated according to the Suzuki and Tsuchihashi classification system. A predominant Type was attributed to each lip print based on the prevailing pattern observed across the sextants and, in a parallel analysis, the presence of gender-specific features within the lip prints was examined.

The collected data and analyses were then transferred to Microsoft Excel for further investigation. This enabled the researchers to examine the frequency of different lip print patterns within the sample, facilitating a comprehensive understanding of the observed patterns and their potential implications.

3. Results

Of the 172 prints, 1 female and 4 males were excluded as they did not meet the study’s inclusion criteria. A further 59 prints (39 male and 20 female) were not included in the Suzuki and Tsuchihashi classification as they presented unreadable sextants due to the poor quality of the sample. These, however, were analyzed to assess their uniqueness and to see which sextants were most affected by technique errors. The final sample that could be used for Suzuki and Tsuchihashi classification was made up of 43 male and 65 female prints.

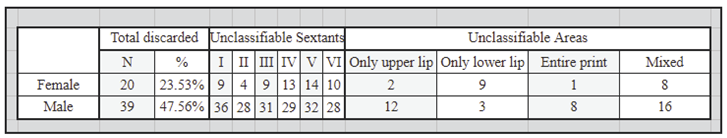

This percentage of qualitatively invalid prints (35.3%) underlines how important it is to establish a standardized acquisition protocol that can enable the acquisition of the sharpest and clearest possible prints. The analysis of the prints found to be invalid revealed several interesting facts [

Table 1]:

Male prints proved more difficult to obtain; more than twice as many male prints (47.56%) as female prints (23.53%) were discarded.

The individual male prints had, on average, more sextants involved than female ones, 3.9 and 2.95 respectively.

Male prints were more illegible in the upper lip, unlike female prints, where the opposite tendency was noted.

Of the male prints, 8 were not readable in their entirety, while only 1 of the female prints had the same level of insufficient quality.

Table 1.

Evaluation of prints and analysis of affected areas.

Table 1.

Evaluation of prints and analysis of affected areas.

Analysis of all the prints using superimposition confirmed the uniqueness of the prints; a match between the prints of different individuals was not possible.

While it may be feasible to identify a particular type for an entire lip print in some instances, it is often found that Suzuki and Tsuchihashi classification is overly simplistic and not universally applicable, except perhaps in specific areas such as portions of the lips. Moreover, the Suzuki and Tsuchihashi classification system tends to be didactic, meaning it offers broad categorizations that may not fully capture the nuanced variations present in lip prints. While it can be useful as a basic framework for understanding lip print patterns, it may fall short when attempting to provide detailed or comprehensive analysis because of the primary challenges lies in the fact that lip prints can exhibit a variety of patterns within the same area [

15].

A further relevant factor was that the analysis of the same print by different operators often resulted in a different attribution of a Type. Paying attention to these errors, the greatest inconsistencies were noted between:

Type I and Type I’: Some operators attributed Type I to the presence of at least one complete vertical labial wrinkle, while others did this only if most, if not all, of the vertical wrinkles were complete.

Type I/I’ and II: In some limited cases, it could not be determined whether one lip wrinkle was the offshoot of another or whether there were two separate wrinkles.

Type II and III: This turned out to be the most frequent error, with some operators considering branching wrinkles as intersecting and vice versa, mistaking Type II and Type III with each other.

Type V: In some limited cases, there was the propensity to attribute a Type V when the prints were of an apparently unsuitable quality for cheiloscopy analysis.

Regardless, we proceeded to initially attribute a single Type per sextant to the 108 qualitatively valid prints, subsequently identifying a single Type per print based on the most frequent Type in the six sextants.

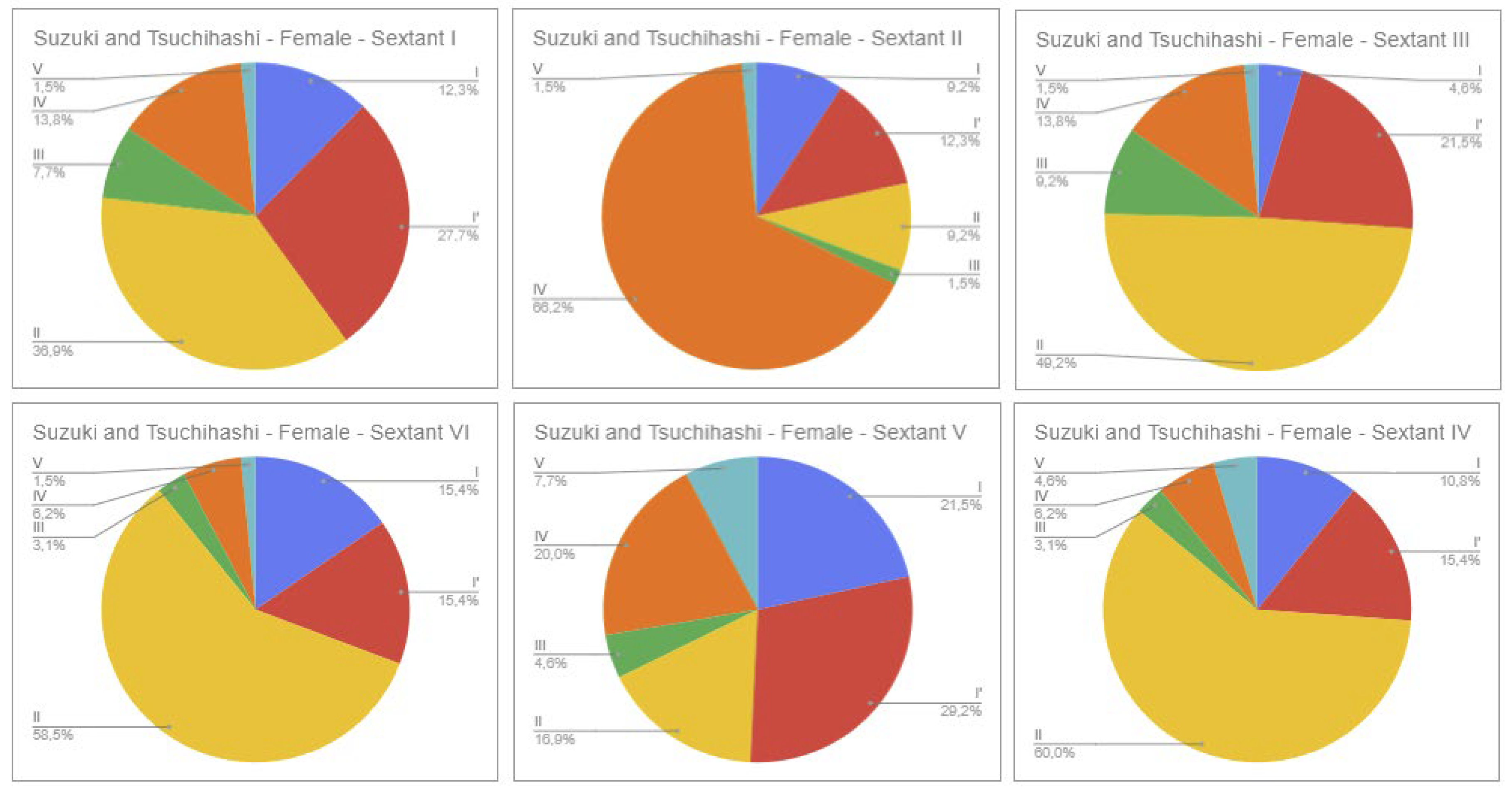

Looking specifically at the data for the individual sextants, in females a prevalence of Type II was found in sextants I (36.9%), III (49.2%), IV (60%) and VI (58.5%), Type IV in sextant II (66.2%) and Type I’ in sextant V (29.2%) [

Figure 4].

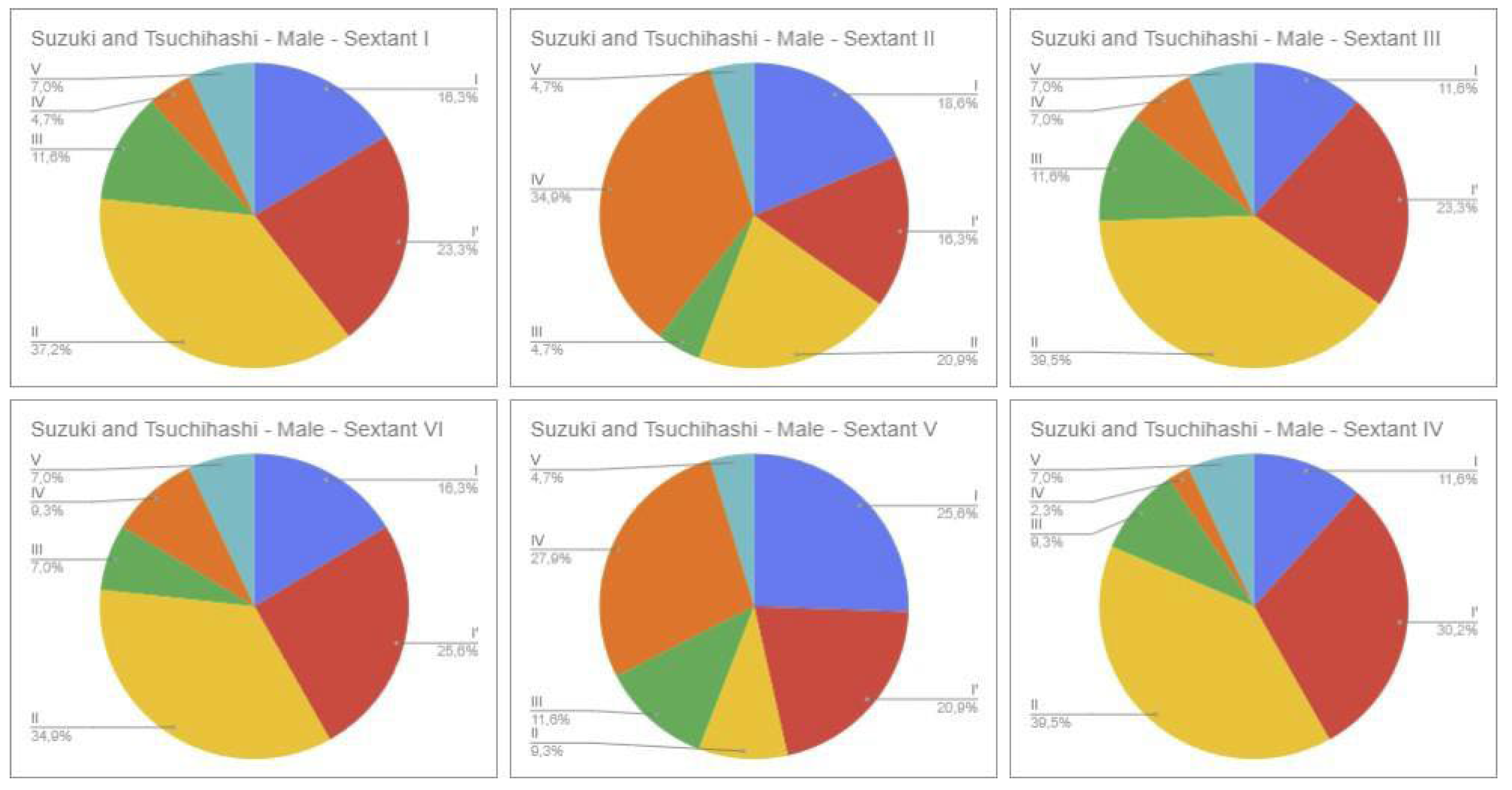

Regarding males, the same prevalence of Type II was noted in sextants I (37.2%), III (39.5%), IV (39.5%) and VI (34.9%), while a prevalence of Type IV was observed in both sextant II (34.9%) and sextant V (27.9%) [

Figure 5].

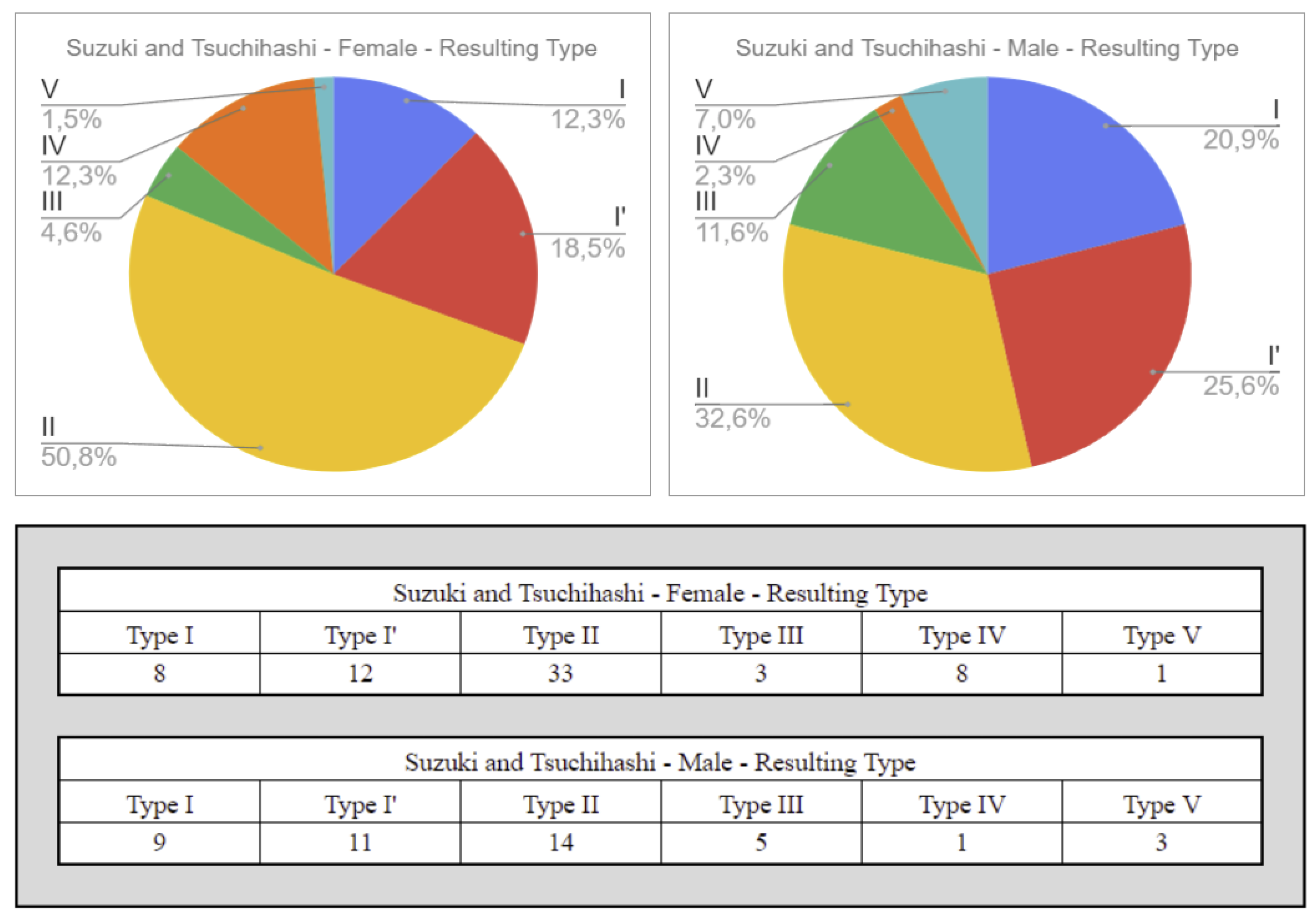

Analyzing the Type attributed to each print as a result of the predominant Type assessment, we found a higher presence of Type II in both females (50.8%) and males (32.6%) [

Figure 6].

The data revealed a certain symmetry along the sagittal axis in the Type distribution. In fact, out of all the 108 prints analyzed, 71 (76,68%) had the same Type in sextants I and III, the same being observed in sextants IV and VI in 74 prints (79.92%).

It was noted that several of the 108 prints showed a particular concave pattern [

Figure 7] for labial wrinkles in the second sextant, concomitant with a Type IV. This same pattern was found in 36.92% of the female prints and 23.08% of the male prints, showing a certain gender discrepancy.

Another finding was the presence of macroscopically appreciable traces of cosmetic products in the perioral areas. These traces were observed in 30 female prints (35.29%) and 0 male prints. They were looked for in all the 167 prints taken, given that they were detectable regardless of the quality of the print.

No statistically significant differences were found about the age of the subjects.

Thanks to the Department of Forensic Medicine at the University of Palermo, it was possible to take lip prints on six individuals who had died of drowning, thereby assessing the behavior of lip wrinkles after prolonged exposure to salt water; it was observed that the pattern of the lip wrinkles remained observable and detectable after an estimated 24/48 hours of being in salt water, whereas in the subject found after more than 4 days, the lip prints were completely smooth and undetectable. If accompanied by further studies, this could become a useful tool in establishing how long a drowned person has been in water.

4. Discussion

Forensic odontology is an important development of forensic medical science and, in the field of justice, deals with the examination, handling and presentation of dental evidence. It plays a pivotal role in identifying the human remains of victims, examining specific cases such as mutilations, burns and decomposition, as well as situations related to bioterrorism and mass disasters [

4].

In the field of cheiloscopy, literature shows us that each lip-print is unique and remains unchanged throughout a person’s lifetime [

16].

The skin (dry zone) of the lip has all the components of facial skin: sweat and sebaceous glands and hair. The vermilion border, or inner surface of the lip, has neither hair nor sweat glands [

17], which could make the detection of latent prints on surfaces inconsistent, as it is not sebum that will be found, but, rather, flaking cells and extremely variable amounts of saliva. This characteristic of lip prints, however, may be of extreme importance, as several studies show that it is possible to extract DNA from latent lip prints from these very residues, creating a synergic effect with cheiloscopy analysis for identification purposes [

18,

19,

20].

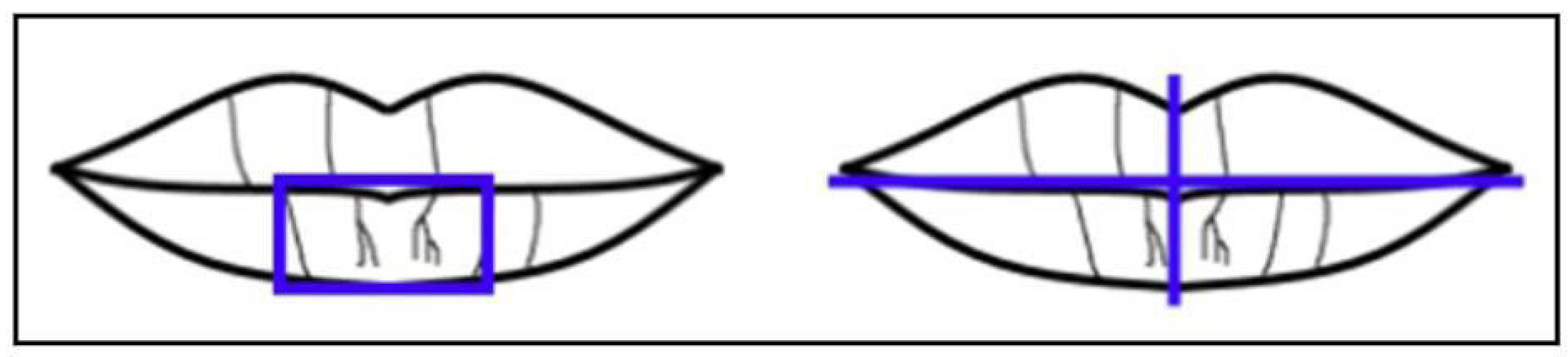

Particular attention must be paid to the way lip prints are observed and analyzed, given that the result of the search for a predominant Type may differ depending on whether the lips are analyzed in their entirety or if attention is paid to a specific portion. Therefore, it is to be expected that a particular Type found when analyzing an entire print may differ from the one found when analyzing a smaller portion [

Figure 8].

There is a worldwide inconsistency in the methods used for obtaining and analyzing lip-prints [

21], resulting in the need to develop a standardized method.

The method most frequently used in literature, i.e., applying lipstick, and acquiring a print using adhesive tape, would appear to be unreliable as there are many variables [

22,

23,

24]:

Lipstick type, viscosity, shade, transferability.

Amount of lipstick applied.

Type of adhesive tape.

Pressure applied and method of application.

Distortion of the lips during acquisition.

Setting time.

Pressure applied with tape.

Other operator-dependent errors.

The selection of specific materials has emerged as a pivotal aspect in the pursuit of obtaining prints of high quality and reliability. Through experimentation, a variety of lipsticks and adhesive tapes were tested to determine their efficacy in capturing accurate impressions. Notably, the decision to exclude stick lipstick from consideration was informed by the inherent challenge of achieving uniform coverage across all lip surfaces—a crucial factor in ensuring the fidelity of obtained prints.

Moreover, our exploration extended to investigating the optimal quantity of lipstick application, it was observed that even minor deviations in application could lead to the obscuration of delicate lip wrinkles, underscoring the need for precision in the printing process. Similarly, the examination of the pressure exerted during detection revealed nuanced insights; the application of gentle pressure to the extremities of adhesive tape emerged as the preferred technique, minimizing the risk of distortion while maximizing the retention of crucial details.

About the adhesive tape selection, while differences in thickness may appear trivial, our discerning analysis led us to discard tapes with excessively thin profiles. This decision was predicated on the realization that such tapes, when applied, tended to form inadvertent folds as they endeavored to conform to the contours of the lips.

Furthermore, it became evident that the distortion observed during acquisitions is not solely attributable to material properties and pressure dynamics. Rather, the very nature of our controlled acquisition environment—a realm characterized by ideal conditions and homogeneous surfaces—introduces a potential disconnect when attempting to extrapolate findings to real-world scenarios. In forensic contexts, for instance, prints may be encountered on diverse surfaces such as straws or cigarettes [

25], each presenting unique challenges that must be navigated to ensure accurate analysis and interpretation.

Lastly, our exploration unearthed the impact of variations in lipstick setting time on print quality. Prints taken immediately post-application often manifested as smudged and indistinct, showing the need for careful consideration of temporal factors in the printing process.

Furthermore, it was observed that the position of the lips during the capture of the print will influence the readings. Qualitatively significant differences were found between prints taken with the lips closed and those taken with the mouth open. Closed lips displayed more defined grooves which were easier to interpret. The absence of front teeth may also cause difficulties in developing prints [

26].

In summation, this inquiry into materials, techniques, and environmental factors aims not only to refine current methodologies but also to lay the groundwork for future advancements in forensic science and investigative practice.

Not only are operator-dependent errors frequently encountered during the process of obtaining prints, but they also persist as well during the subsequent analysis of these prints. The inherent challenge lies in the precise attribution of a specific Type to a print or even a segment of it, thereby rendering the resultant conclusions only partially dependable.

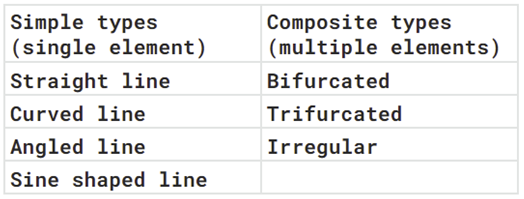

Although the Suzuki and Tsuchihashi classification is the most used in the literature, there are several classifications proposed by other authors such as:

Dr. Santos that in 1966 divided the nature of wrinkles and grooves into simple and compound types, those were subdivided in four different groups, Dr. Santos applied also classified lips in thin, medium, thick and mixed type and reported various types of commissures. [

27,

28,

29] [

Table 2].

Table 2.

Dr. Santos classification of lip grooves.

Table 2.

Dr. Santos classification of lip grooves.

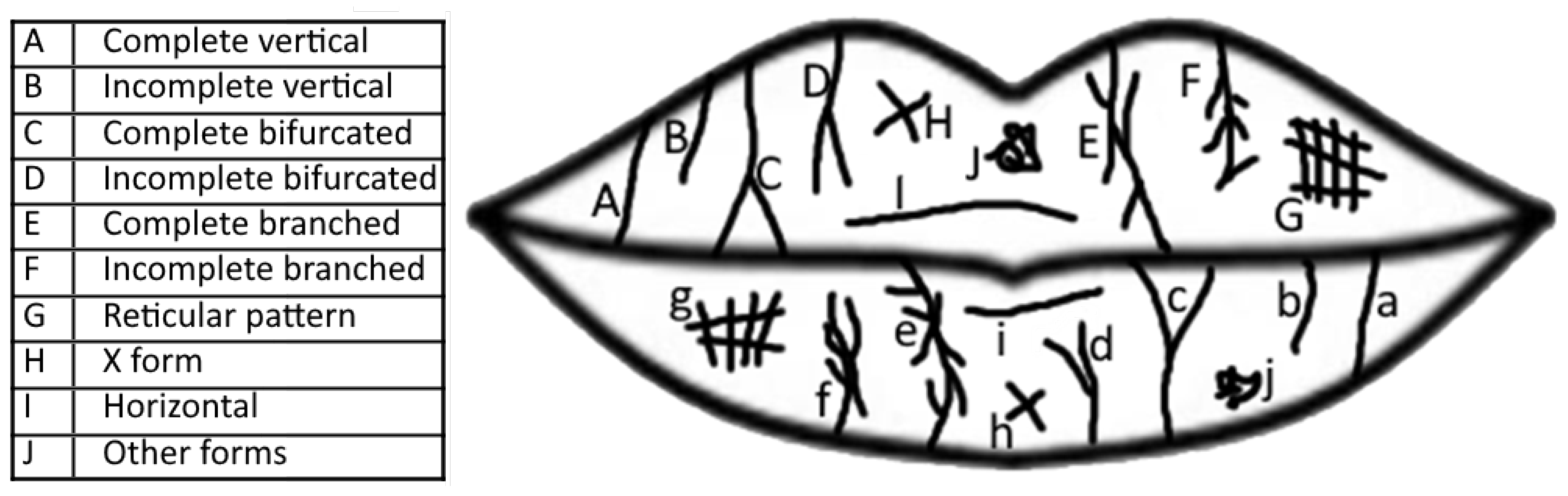

A French scientist, Renaud, that studied 4000 prints and describes 10 types of lip prints, designated by letters from A to J, capital letters for upper lips and lowercase for bottom lips [

30] [

Figure 9]

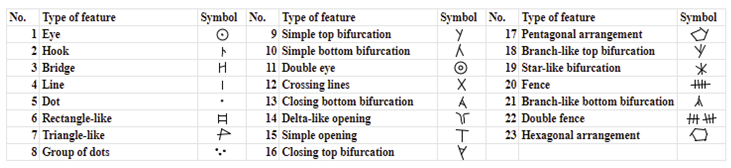

Kasprzak that determined the pattern based on the numerical superiority of properties of the lines on the fragment. After the patterns of lines had been established, a first catalog of individual features was prepared and 23 types of individual properties were differentiated [

31,

32]

Table 3.

Kasprzak classification of lip grooves.

Table 3.

Kasprzak classification of lip grooves.

The analysis of the prints revealed that the Suzuki and Tsuchihashi classification was didactic and not easy to apply. Very often, different types were found to co-exist on the same analyzed portion [

16]. Considering this, and given the strict conditions of this study, the reliability of the data obtained regarding the Suzuki and Tsuchihashi classification is uncertain.

Considering the data analysis regarding the presence of a circular pattern in the second sextants, which is statistically more evident in the female gender, we suggest that this peculiarity could be used as a discriminating element in gender identification, if confirmed by further research.

There would not seem to be any substantial differences about the age of the subject. In fact, there was good homogeneity in the data obtained, while there was a great lack of homogeneity in the quality of the prints regarding the sex of the test subject, with detection errors being greater among males.

Another characteristic observed was the presence of material found in the perilabial areas, such as residue from cosmetic products, which was already present in a statistically significant percentage during macroscopic analysis. This is a finding that could potentially increase if we were to carry out research by chemically analyzing samples. We believe this could increase the accuracy of our conclusions regarding gender determination and contribute to a more complete evaluation of the lip prints being analyzed.

The use of cadaver cheiloscopy would seem to have great potential where other tools available to forensic science are not applicable, but the possibility of post-mortem modifications to the original lip wrinkle pattern must be taken into account [

33]. Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights how cheiloscopy has great potential in forensics, but the absence of standardized methods to minimize errors in obtaining and interpreting prints makes its application limited.

The need to develop a standardized capture protocol is evident; after an analysis of the major problems encountered with the lipstick method, it was concluded that a change of approach was needed. A photographic approach could be used, establishing capture parameters for the lips, thereby minimizing operator-dependent errors.

The application of a digital analysis system is also necessary. In particular, it was observed that different operators can attribute different Types when analyzing the same print because there is no univocal criterion for attributing these Types and also because of the previously discussed problem regarding the coexistence of different Types. A special software that can analyze a print, bypassing human error, would provide more reliable and statistically significant data and would also reduce the time needed to analyze the prints.

Another major limitation of the method is the absence of a database, making only 1-1 matching of prints possible and possibly leading to deductions about the individual’s gender.

The actual use of lip prints in court is rare and its acceptance debatable. Professor Jay Siege (Professor of Forensic Science and Associate Director of the School of Criminal Justice, Michigan State University) considers lip print evidence to be admissible in court, but lip-print evidence has not been used much in the court system and its acceptance is debatable [

34,

35].

From the data collected from the literature, it is clear that there are multiple classification approaches. However, we consider important to pursue a goal of convergence to define a single universal classification, this would represent an essential basis not only for guiding future research but also for facilitating comparison and understanding among scholars in the field.

The results obtained in this study need to be confirmed in future studies, adopting the aforementioned precautions. The aim must be to develop a single acquisition protocol and to analyze the prints using digital methods. It would be interesting to call upon the study participants to perform a further survey through photographic means and to analyze the data with dedicated software in order to assess any discrepancies with the previously acquired data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.A.S. and P.M.; methodology, E.D.V., F.M.S., S.V., L.R., A.T.; software, ; validation, A.A., D.A. and S.Z.; formal analysis, E.C.; investigation, E.D.V., F.M.S., S.V., L.R., A.T. ; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, E.D.V., F.M.S., S.V., L.R., A.T.; writing—review and editing, E.C., G.B.; supervision, P.M., G.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board or Ethics Committee University of Palermo Policlinico “Paolo Giaccone”.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be requested to alessandro.scardina@unipa.it.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Inoue H. (Forensic Science and Scientific Investigation). Yakugaku Zasshi. 2019;139(5):685- 691. Japanese. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, Piyush K., Maithri Tharmavaram, and Gaurav Pandey. “Conventional technologies in forensic science.” Technology in Forensic Science: Sampling, Analysis, Data and Regulations (2020): 17-34.

- Chidambaram R. Dentistry’s Cardinal Role in Forensic Odontology. Iran J Public Health. 2014 Aug;43(8):1152-3. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mohammed F, Fairozekhan AT, Bhat S, Menezes RG. Forensic Odontology. 2023 Aug 14. In: StatPearls (Internet). Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. [PubMed]

- Sciarra F.M., Messina P., Scardina G.A. (2023). Bitemarks in forensic odontology: aspects, study methodology and critical analysis issues. DENTAL CADMOS, 91(8), 642-650. [CrossRef]

- Trizzino A, Messina P, Sciarra FM, Zerbo S, Argo A, Scardina GA. Palatal Rugae as a Discriminating Factor in Determining Sex: A New Method Applicable in Forensic Odontology? Dent J (Basel). 2023 Aug 29;11(9):204. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nagare SP, Chaudhari RS, Birangane RS, Parkarwar PC. Sex determination in forensic identification, a review. J Forensic Dent Sci. 2018 May-Aug;10(2):61-66. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kasprzak, Jerzy. “Possibilities of cheiloscopy.” Forensic science international 46.1-2 (1990): 145-151.

- Gustafson, Gösta. “Forensic odontology.” Australian Dental Journal 7.4 (1962): 293-303.

- Tsuchihashi Y. Studies on personal identification by means of lip prints. Forensic Sci. 1974 Jun;3(3):233-48. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamim, T., et al. “Forensic odontology: a new perspective.” Medicolegal Update 6 (2006): 1-4.

- Šimović M, Pavušk I, Muhasilović S, Vodanović M. Morphologic Patterns of Lip Prints in a Sample of Croatian Population. Acta Stomatol Croat. 2016 Jun;50(2):122-127. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Regan ES, Bradshaw BT, Bruhn AM, Melvin W, Sikdar S. Populational Variations of Cheiloscopy Patterns: A cross-sectional observation pilot study. J Dent Hyg. 2023 Oct;97(5):196-204. [PubMed]

- Bingoel AS, Dastagir K, Neubert L, Obed D, Hofmann TR, Krezdorn N, Könneker S, Vogt PM, Mett TR. Complications and Disasters After Minimally Invasive Tissue Augmentation with Different Types of Fillers: A Retrospective Analysis. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2022 Jun;46(3):1388-1397. Epub 2021 Dec 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- UDIN, NUR & RAHMAN, NUR & Gabriel, Gina & Hamzah, Noor Hazfalinda. (2019). Digital Approach for Lip Prints Analysis in Malaysian Malay Population (Klang Valley): Photograph on Lipstick-Cellophane Tape Technique. Jurnal Sains Kesihatan Malaysia. 17. 43-49. [CrossRef]

- Singh et al., 2010; Vamsi Krishna Reddy, 2011; Sivapathasundharam et al., 2001; Vahanwalla and Parekh, 2000; Saraswathi et al., 2009; Gondvikar et al., 2009.

- Walker WB. The Oral Cavity and Associated Structures. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd ed. Boston: Butterworths; 1990. Chapter 129. [PubMed]

- Sharma P, Sharma N, Wadhwan V, Aggarwal P. Can lip prints provide biologic evidence? J Forensic Dent Sci. 2016 Sep-Dec;8(3):175. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Castelló A, Alvarez M, Verdú F. Just lip prints? No: there could be something else. FASEB J. 2004 Apr;18(6):615-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee R, Kar AK. Cheiloscopy: A crucial technique in forensics for personal identification and its admissibility in the Court of Justice. Morphologie. 2024 Mar;108(360):100701. Epub 2023 Oct 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furnari W, Janal MN. Cheiloscopy: Lip Print Inter-rater Reliability. J Forensic Sci. 2017 May;62(3):782-785. Epub 2016 Dec 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangam M, K P, Bokan R R, et al. (February 06, 2024) Distribution and Uniqueness in the Pattern of Lip Prints. Cureus 16(2): e53692. [CrossRef]

- Prabhu RV, Dinkar A, Prabhu V. Digital method for lip print analysis: A New approach. J Forensic Dent Sci. 2013 Jul;5(2):96-105. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sandhu SV, Bansal H, Monga P, Bhandari R. Study of lip print pattern in a Punjabi population. J Forensic Dent Sci. 2012 Jan;4(1):24-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fonseca GM, Bonfigli E, Cantín M. Experimental model of developing and analysis of lip prints in atypical surface: A metallic straw (bombilla). J Forensic Dent Sci. 2014 May;6(2):126-31. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sandhu SV, Bansal H, Monga P, Bhandari R. Study of lip print pattern in a Punjabi population. J Forensic Dent Sci. 2012 Jan;4(1):24-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Williams TR. Lip Prints – Another means of identification. J Forensic Indent. 1991;41:190–4.

- Suzuki K, Tsuchihashi Y. A new attempt of personal identification by means of lip print. JADA. 1970;42:8–9.

- Molano MA, Gil JH, Jaramillo JA, Ruiz SM. Revista facultad de odontología universidad de antioquia. Rev. Fac. Odonto. Univ. Antioquia.

- Ata-Ali, Javier & Ata-Ali, Fadi. (2014). Forensic dentistry in human identification: A review of the literature. Journal of clinical and experimental dentistry. 6. e162-e167. [CrossRef]

- Kasprzak J. Possibilities of cheiloscopy. Forensic Sci Int. 1990;46:145–51. [CrossRef]

- Kasprzak J. Cheiloscopy. In: Siegal JA, Saukko PJ, Knupfer GC, editors. Encyclopedia of forensic sciences. Vol. 1. London: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 58–61.

- Arthanari A, Priyadharshini R, Sinduja P, Cheiloscopy and Palatoscopy in Forensics– A Review. Int J Clinicopathol Correl. 2022; 6:1:12-15.

- Ball J. The current status of lip prints and their use for identification. J Forensic Odontostomatol. 2002 Dec;20(2):43-6. PMID: 12585673. [PubMed]

- R. Bhattacharjee, A.K. Kar, Cheiloscopy: A crucial technique in forensics for personal identification and its admissibiliy in the Court of Justice, Morphologie, Volume 108, Issue 360, 2024, 100701, ISSN 1286-0115.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).